Abstract

Background: To evaluate marginal bone loss (MBL) in immediate implant procedures (IIP) placed in conjunction with platelet concentrates (PCs) compared to IIP without PCs. Methods: A search was performed in four databases. Clinical trials evaluating MBL of IIP placed with and without PCs were included. The random effects model was conducted for meta-analysis. Results: Eight clinical trials that evaluated MBL in millimeters were included. A total of 148 patients and 232 immediate implants were evaluated. The meta-analysis showed a statistically significant reduction on MBL of IIP placed with PCs when compared to the non-PCs group at 6 months (p < 0.00001) and 12 months (p < 0.00001) follow-ups. No statistically significant differences were observed on MBL of IIP when compared PCs + bone graft group vs. only bone grafting at 6 months (p = 0.51), and a significant higher MBL of IIP placed with PCs + bone graft when compared to only bone grafting at 12 months was found (p = 0.03). Conclusions: MBL of IIP at 6 and 12 months follow-ups is lower when PCs are applied in comparison to not placing PCs, which may lead to more predictable implant treatments in the medium term. However, MBL seems not to diminish when PCs + bone graft are applied when compared to only bone grafting.

1. Introduction

Nowadays, the placement of dental implants immediately after tooth extraction has become a hot topic [1]. Immediate implant procedures (IIP) not only decrease the total treatment time but also improve aesthetics and maintain soft tissues shape [2,3]. However, the dimension of the alveolar bone is also reduced even with IIP [4]. This bone resorption depends on several factors such as the thickness of the buccal wall and the gap size between bone and implant [5]. For these reasons, different substances such as bone grafts or platelet concentrates (PCs) have been proposed as alternatives to prevent this bone resorption [6,7].

PCs are autogenous substances derived from blood that consist essentially of supraphysiologic concentrations of platelets and growth factors [8]. Two types can be distinguished among PCs: platelet-rich fibrin (PRF) and platelet-rich plasma (PRP), which in turn can be rich in leucocytes (L-PRF and L-PRP) or pure (P-PRF and P-PRP) [9]. PCs can be prepared with or without red blood cells, and can be prepared from anticoagulated blood (PRP, P-PRF) or non-anticoagulated blood (L-PRF). Its preparation is carried out with centrifugation techniques that will depend on the size of the rotor, angulation and design of tubes, revolutions per minute or centrifugation time [10].

The high concentrations of growth factors and cytokines present in PCs are of great importance for tissue healing [8]. The efficacy of PCs in promoting wound healing and tissue regeneration is at the center of a recent academic debate [11]. PCs have demonstrated the capacity to improve soft tissue healing after surgical procedures [12,13,14]. There is also literature that confirms the local hemostatic efficacy of PCs after dental extractions in patients treated with antiplatelet drugs [15]. Nonetheless, there is still controversy about whether PCs have positive outcomes on hard tissue healing [16]. Indeed, several systematic reviews have shown moderate evidence supporting the clinical benefit of PRF on ridge preservation [17], or a favorable effect of L-PRF on bone regeneration and osseointegration [18]. Another study has shown insufficient evidence to establish the effectiveness of PCs in the prevention and treatment of medication-related osteonecrosis of the jaw [19].

Maintenance of peri-implant tissues play a main role in the functional sustainability of implant rehabilitation. Specifically, marginal bone loss (MBL) could compromise the long-term prognosis of implant procedures increasing the risk of peri-implantitis [20]. Although numerous surgical techniques have been developed to increase implant stability values [21,22], a recent study showed as primary implant stability is of main importance in the changes of marginal bone level during the early healing period [23]. Regarding peri-implant marginal bone, some authors have observed alveolar bone preservation related to IIP when PCs were applied [24,25], while Taschieri et al. [26] in a retrospective study did not find statistically significant differences in MBL of IIP placed with or without P-PRP with a follow-up of up to 5 years.

As there is controversy regarding the effect of PCs in hard tissue healing, and specifically in MBL after IIP [27], and no systematic review evaluating their effect have been performed up to now, we have conducted the first systematic review concerning the effectiveness of PCs on IIP for the maintenance of marginal bone. Therefore, the aim of this systematic review was to evaluate the evidence on MBL of IIP in combination with PCs when compared to IIP without using PCs.

2. Materials and Methods

This systematic review was structured according to the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses Protocols (PRISMA) statement [28], and it was recorded in PROSPERO (Registration number: CRD42021247128).

2.1. Focused Question

The aim of the study was to answer the following PICO (population, intervention, comparison, and outcome) question based on the PRISMA guidelines: In patients with at least one implant immediately placed after tooth extraction (population), what is the effectiveness of using PCs around the implant (intervention) when compared to not placing PCs (comparison) to diminish MBL (outcome)?

2.2. Eligibility Criteria

2.2.1. Inclusion Criteria

The studies had to be (a) randomized controlled clinical trials (RCTs) or controlled clinical trials (CCTs), (b) published in English, and (c) performed only in humans. The population (P) had to be patients who had received dental implants immediately after tooth extraction placed with PCs (intervention group (I)) and without PCs (control group (C)) in a split mouth or a non-split mouth design. We also included studies in which bone substitutes were used, both in the group where PCs were applied, as well as in the control group. The following types of PCs were included: PRF, PRP, L-PRF, L-PRP, P-PRF, P-PRP and PRGF. The implants could have been placed in any location of the mandible and/or the maxilla and could have any length or width. With respect to the outcomes (O), the studies had to (a) radiographically assess the marginal bone resorption of the implants: MBL or crestal bone height, and (b) report the results in millimeters (mm) without restriction for follow-up time, in both the PCs and non-PCs groups.

2.2.2. Exclusion Criteria

Studies excluded were: (a) studies that did not use PCs for IIP, (b) studies that evaluated PCs for conventional dental implant procedures (not placed immediately after tooth extraction), (c) studies that performed flapless procedures, and (d) non-randomized studies, review articles, experimental studies, retrospective studies, case reports, commentaries or letters to the Editor and unpublished articles.

2.3. Information Sources and Search Strategy

A comprehensive search of the literature was conducted without date restriction until 19 April 2021 in the following databases: PubMed/MEDLINE, The Cochrane Library, Web of Science and Scopus. The search was performed by two independent researchers (J.G-S., C.V.). The search strategy used was a combination of following keywords adapted to each database (Table 1).

Table 1.

Search strategy employed in the present systematic review.

2.4. Study Records

Two researchers (J.G-S. and C.V.) independently compared search results to ensure completeness and removed duplicates. Then, full title and abstract of the remaining papers were screened individually. Finally, full text articles to be included in this systematic review were selected according to the criteria described above. Disagreements over which eligible studies were to be included were discussed with a third reviewer (R.M.L-P.), and a consensus was reached. The reference lists of the included studies were also reviewed for possible inclusion. Agreement between reviewers was measured with the Kappa coefficient. The results were also expressed as the concordance between both reviewers (%).

2.5. Data Collection

Two independent reviewers (J.G-S. and C.V.) extracted the data. Data extraction included the following information: (a) the general characteristics of the selected studies: first author, year and country in which the study was conducted, type of study, number of patients and implants analyzed, sample age and sex, inclusion and exclusion criteria, the periodontal treatment received and the clinician who placed the implants (Table 2); (b) the surgical and implants characteristics of the included studies: types of PCs used, PCs preparation protocol, PCs application form, premedication, local anesthetic, surgical procedure, implant position, socket and gap characteristics, implant dimensions, regions of implants insertion, postsurgical medication, prosthetic procedure, marginal bone evaluation and complications (Table 3); and (c) MBL (mean ± standard deviation (SD)), implant survival rates (%) and follow-up period (months) of IIP placed with PCs and without PCs, respectively (Table 4).

Table 2.

General characteristics of the selected studies.

Table 3.

Surgical and implants characteristics of the included studies.

Table 4.

Marginal bone loss (MBL) during the postoperative period (mean ± SD) and implants survival rates (%).

2.6. Risk of Bias in Individual Studies

Two independent reviewers (J.G-S. and C.V.) evaluated the methodological quality of eligible studies following the Cochrane Collaboration’s tool for assessing risk of bias, which incorporates 7 domains [29]. The studies were classified as low risk of bias (low risk of bias for all key domains), unclear risk of bias (unclear risk of bias for one or more key domains), and high risk of bias (high risk of bias for one or more key domains) [29].

2.7. Assessment of Evidence Levels

We evaluated the quality of evidence using the Grading of Recommendations Assessment, Development and Evaluation (GRADE) framework, which characterizes the quality of a body of evidence based on the study limitations, imprecision, heterogeneity and inconsistency, indirectness, and publication bias. The GRADE approach enabled us to assign one of four confidence levels (high, moderate, low, or very low) [30].

2.8. Synthesis of Results

Review Manager (RevMan) (Computer program), version 5.3 (The Nordic Cochrane Centre, The Cochrane Collaboration, Copenhagen, Denmark, 2014) was used to perform the meta-analysis. The Cochrane Q-test was used to assess heterogeneity between studies. I2 index was calculated to perform quantitative analysis of heterogeneity, which assesses the percentage of variation in the global estimate attributable to heterogeneity (I2 = 25%: low; I2 = 50%: moderate; I2 = 75%: high heterogeneity). The random effect model was used to group the study-specific estimates. Publication bias was planned to be conducted in analysis with 10 studies or more [31]. Statistical significance was defined as a p value < 0.05.

2.9. Sensitivity Analysis

For sensitivity analysis, each meta-analysis was performed using all possible combinations, including fixed-effect methods and standardized mean difference (SMD).

3. Results

3.1. Study Selection

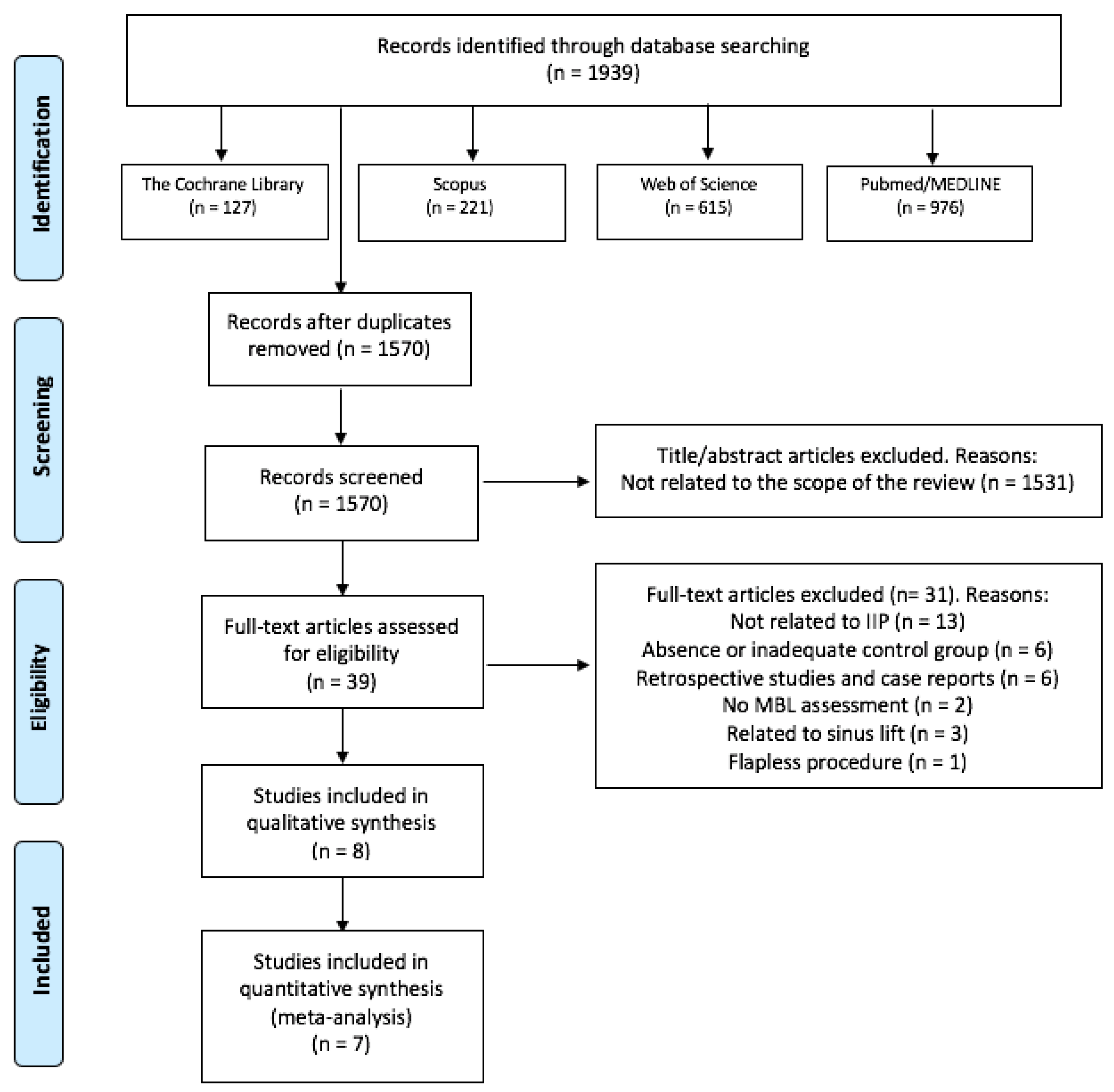

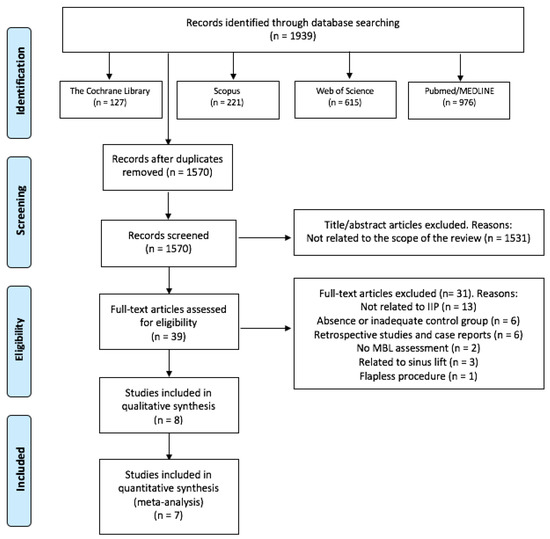

The search strategy resulted in 1939 results, of which 1570 remained after removing the duplicates. Then, two independent researchers (J.G-S. and C.V.) reviewed all the titles and abstracts and excluded 1531 papers that were outside of the scope of this review. Thus, we obtained 39 potential references. After reading the full text of those 39 papers, 13 were discarded for not analyzing IIP, 6 for an absence or inadequate control group, 6 for being retrospective observational studies or case reports, 3 studies related to sinus lift, two for not assessing MBL and one for performing flapless procedures. Finally, 8 studies were included in our systematic review [32,33,34,35,36,37,38,39] (Figure 1). Only two of the three groups of Alam et al. [38] study were considered in this review (PCs + bone graft group vs. only bone graft group). There was a 99.18% concordance between the two authors with a Kappa coefficient of 0.85 (SE 0.04, 95%CI [0.77, 0.93]) for titles and abstracts, and a 97.43% concordance with a Kappa coefficient of 0.93 (SE 0.08, 95%CI [0.74, 1]) for full-text articles, respectively.

Figure 1.

Flow diagram of the literature search, according to the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA).

3.2. Study Characteristics

The selected articles were published between 2015 and 2020 [32,33,34,35,36,37,38,39]. One study was a CCT [32] and seven studies were RCTS [33,34,35,36,37,38,39]. Three of the selected studies had a split-mouth design [32,33,37]. Four of them were performed in India [35,36,38,39], one in Syria [32], one in Saudi Arabia [33], one in Turkey [37] and one in Egypt [39] (Table 2).

3.2.1. Patients’ Characteristics

Combining the samples from each study, a total of 148 patients were studied. Only three studies reported the age and sex of the included patients [32,36,39]. The age ranged from 18 to 55 years, there being 32 males and 23 females. Systemically healthy patients were included in every study [32,33,34,35,36,37,38,39]. Regarding the inclusion of smokers, six studies excluded smokers [32,33,35,37,38,39], one included smokers of less than 10 cigarettes per day [36] and one included smokers [34]. Concerning the periodontal status, Al Nashar et al. [32] included patients with chronic periodontitis in the mandibular anterior region, Khan et al. [35] excluded patients with severe periodontal bone loss, and six studies [33,34,36,37,38,39] included patients with good oral hygiene. The patients of four of the selected studies underwent periodontal therapy prior to IIP [33,35,37,39], one study included patients for professional periodontal maintenance during the study [37], another study evaluated oral hygiene during the study [38], while the other two studies did not mention it [32,34] (Table 2).

3.2.2. Implants and Bone Characteristics

All the included studies used IIP in both the study and the control groups [32,33,34,35,36,37,38,39]. A total of 232 IIP (117 implants with PCs and 115 implants without PCs) were studied. Four of the included studies used PCs (study group) vs. no PCs (control group) [32,34,35,36,37], and four of them used PCs in combination with bone substitutes (study group) vs. only bone substitutes (control group), of which 3 used xenografts [33,37,39] and one used a synthetic bone graft [38] for IIP. The implants were placed in the mandibular lateral incisors [32], in the maxillary anterior teeth [33,37,38] and premolars [39], and different sites of maxilla and mandible [34,35,36]. Two studies placed the implants at crestal bone level [32,33], one study slightly below the bone crest [35], two studies below the alveolar bone: 2 mm [36] and 1 mm [39], one study 2 mm below the cementoenamel junction of the adjacent teeth [38], while Gangwar et al. [34] did not report it. With respect to the sockets included in the selected studies, two studies reported four bone walls [32,35], two studies buccal bone loss [33,37] and four studies adequate bone [34,36,38,39]. Only three studies mentioned the bone–implant gap: Khan et al. [35] included gaps <2 mm, Öncü et al. [36] included gaps of about 1 mm and Alam et al. [38] included gaps between 2 and 5 mm (Table 3).

3.2.3. Radiographic Evaluation

Al Nashar et al. [32] used orthopantomography to determine MBL, while the other seven studies [33,34,35,36,37,38,39] used periapical radiographs. Six of them [34,35,36,37,38,39] used positioners, so that the radiographs were reproducible in the different follow-ups, while ArRejaie et al. [33] did not specify it.

Seven of the included studies used the real length of the implants to calculate the radiographic MBL [32,34,35,36,37,38,39] from the shoulder of the implant [32,34,35,36,37,38] and the implant–abutment connection [39] to the first bone–implant contact site. ArRejaie et al. [33] measured MBL but did not specify how. All the studies expressed the results in millimeters [32,33,34,35,36,37,38,39]. Six of them expressed the values in the mesial and distal aspects [33,34,35,37,38,39], while two of them [32,36] expressed the mean values between mesial and distal aspects (Table 3).

3.2.4. Platelet Concentrates (PCs) Protocols

Three of the included studies used PRP [32,33,34], while the other five used PRF [33,34,35,36,37,38,39]. Two studies applied PCs as liquid [32,34], one as gel form [33], one as both liquid and solid [35], and four studies as solid membranes [36,37,38,39]. The different protocols of the studies included are shown in Table 3.

3.3. Main Findings

The results of MBL, implant survival rates and follow-up periods of the included studies are shown in Table 4.

3.3.1. Marginal Bone Loss (MBL)

- PCs vs. non-PCs

Al Nashar et al. [32] reported significantly lower MBL of IIP placed with PCs in comparison to control group at 3 months (p < 0.0001), 6 months (p < 0.0001) and 12 months (p < 0.0001) follow-ups. Gangwar et al. [34] reported statistically lower MBL at 6 months follow-up of PCs group in comparison to control group (mesial: p = 0.003, distal p = 0.001). Khan et al. [35] achieved no statistically significant differences in MBL between two groups at any of the visits during the 13–14 months follow-up period. Öncü et al. [36] found statistically lower MBL in the PCs group in comparison to the control group at 12 months follow-up (p ≤ 0.05).

- PCs + bone graft vs. only bone graft

ArRejaie et al. [33] showed no statistically significant differences between the two groups in MBL at 3 months follow-up (p = 0.067), but statistically significant reductions at 6 months (p < 0.01), 9 months (p < 0.0001), and 12 months (p < 0.0001) follow-ups in PCs in comparison to control group. Soni et al. [37] showed no statistically differences in MBL at 4 months in the PCs group when compared to control group (mesial: p = 0.85; distal: p = 0.94). Alam et al. [38] did not find statistically significant differences in MBL between groups at 12 months in either mesial or distal aspects (p > 0.05). Abdel-Rahman et al. [39] reported no statistical differences in MBL at 6 months (p = 0.11), 12 months (0.078) and 18 months (0.052) after IIP between the two groups.

3.3.2. Implant Survival Rates

Six studies achieved 100% survival rates in each group [32,35,36,37,38,39]. ArRejaie et al. [33] and Gangwar et al. [34] did not specify the survival rates in each group. Gangwar et al. [34] reported a 90% survival rate for the two groups together.

3.4. Risk of Bias within Studies

According to the 7 domains for assessing risk of bias, we established that all the included studies had a high risk of bias (high risk of bias for one or more domains) (Table 5). One study [32] had a high risk of selection bias because it did not mention if randomization was made and because no allocation concealment was made. Four studies had an unclear risk of selection bias because they did not report how the allocation concealment was performed [34,36,37,38,39]. All the clinical trials included [32,33,34,35,36,37,38,39] had high risk of performance bias because the surgeon had to know what technique was performing. Five studies [33,34,36,37,39] had an unclear risk of detection bias because they did not specify who collected the data. Three studies had an unclear risk of attrition bias as no sex and age data were reported [33,34] and three patients in each group were lost to 12-months follow-up [38], respectively. Two of them [33,34] had unclear risk of reporting bias as no implant survival rates were reported in each group, and one study [37] had a high risk of reporting bias because it showed negative results for MBL.

Table 5.

Risk-of-bias assessment of the controlled clinical trials included.

3.5. Evaluation of Evidence Levels

According to the GRADE framework, the quality of the evidence related to the overall ranking of efficacy was low because of the low number of studies included in the meta-analysis, the high risk of bias in all the included studies or the lack of publication bias. There was low-quality evidence in the comparisons between PCs and non-PCs, and the comparisons among PCs + bone graft and bone grafting alone, respectively.

3.6. Synthesis of Results: Meta-Analysis

We used mean ± SD of the implants MBL in mm as the main effect measure. In those studies that showed the mean and standard error of mean (SEM), the SD was calculated by multiplying the standard error of a mean by the square root of the sample size [33,35]. Also, the formulae for combining groups was used in those studies that only showed the results of the mesial and distal aspects of the implants [33,34,35,37,38,39]. Finally, seven articles were included for meta-analysis [32,33,34,35,36,38,39]. Al Nashar et al. [32], Gangwar et al. [34] and Khan et al. [35] studies were included for the MBL after 6 months follow-up, and Al Nashar et al. [32], Khan et al. [35] and Öncü et al. [36] studies were included for the MBL after 12 months follow-up in PCs group vs. non-PCs group, respectively. ArRejaie et al. [33], Alam et al. [38] and Abdel-Rahman et al. [39] studies were included for the MBL after 6- and 12-month follow-ups in PCs + bone graft group vs. only bone graft group.

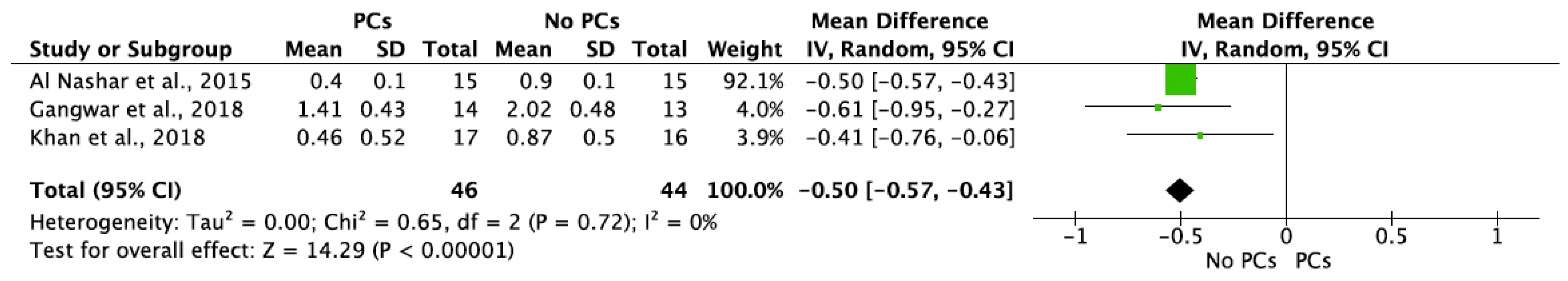

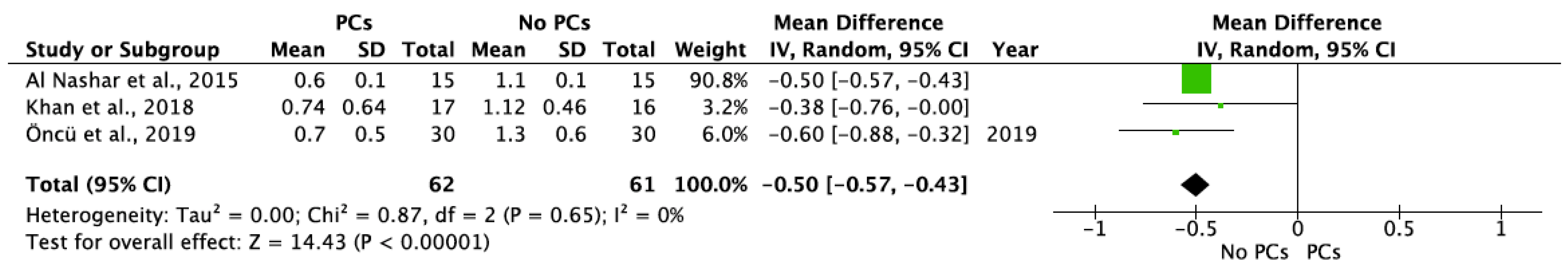

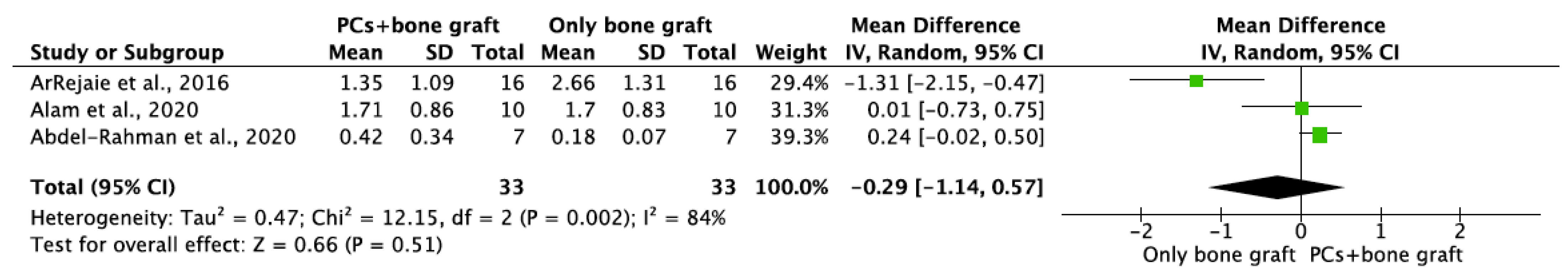

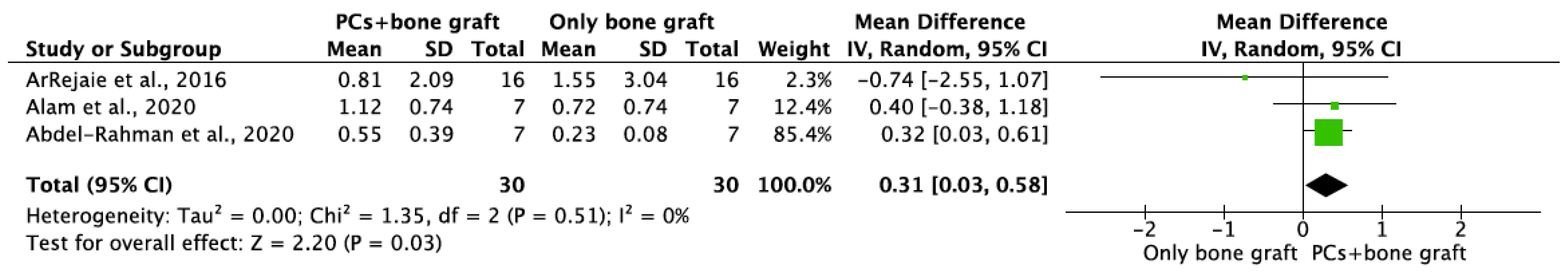

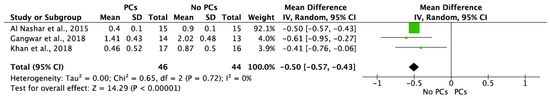

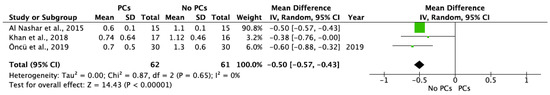

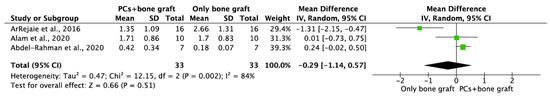

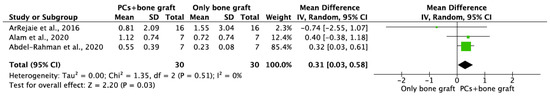

MBL in both aspects after 6 and 12 months of IIP with PCs vs. non-PCs and PCs + bone graft vs. only bone graft were evaluated by mean differences and 95% confidence intervals, respectively. The results of the meta-analysis showed that MBL at 6 months follow-up was significantly lower in IIP placed with PCs in comparison to procedures without PCs (MD −0.50, 95%CI [−0.57, −0.43]; p < 0.00001) (Figure 2). The random-effect model suggested a low heterogeneity across the controlled trials (I2 = 0%) (Figure 2). It also showed that MBL at 12 months follow-up was significantly lower in IIP placed with PCs when compared to non-PCs group (MD −0.50, 95%CI [−0.57, −0.43]; p < 0.00001) (Figure 3). The random-effect model also suggested a low heterogeneity across the controlled trials (I2 = 0%) (Figure 3). At 6 months, the meta-analysis showed that MBL was not statistically significant when compared to the PCs + bone graft group vs. only bone graft (MD −0.29, 95%CI [−1.14, −0.57]; p = 0.51) (Figure 4). The random-effect model showed a high heterogeneity across the controlled trials (I2 = 84%) (Figure 4). However, MBL at 12 months was statistically higher in the PCs + bone graft group when compared to only the bone graft group (MD 0.31, 95%CI [0.03, 0.58]; p = 0.03) (Figure 5). The random-effect model showed a low heterogeneity across the controlled trials (I2 = 0%) (Figure 5).

Figure 2.

Random-effect meta-analysis evaluating marginal bone loss (MBL) in both aspects at 6 months in immediate implants procedures with PCs vs. no PCs.

Figure 3.

Random-effect meta-analysis evaluating MBL in both aspects at 12 months in immediate implants procedures with PCs vs. no PCs.

Figure 4.

Random-effect meta-analysis evaluating MBL in both aspects at 6 months in immediate implants procedures with PCs + bone graft vs. only bone graft.

Figure 5.

Random-effect meta-analysis evaluating MBL in both aspects at 12 months in immediate implants procedures with PCs + bone graft vs. only bone graft.

3.7. Sensitivity Analysis

The results of the different meta-analyses are contained in the Supplementary Material (Figures S1–S12). MBL at 12 months in PCs + bone graft vs. only bone graft showed statistically significant differences when MD was used, and no statistically significant differences when SMD was applied. In the other meta-analyses, the statically significant results did not change and only I2 values were different depending on which method was used.

4. Discussion

4.1. Summary of Evidence

This systematic review included eight clinical trials [32,33,34,35,36,37,38,39] evaluating MBL of IIP placed with and without PCs, and 7 of them [32,33,34,35,36,38,39] were evaluated by meta-analysis. Although there are not many clinical trials on this subject and, therefore, these results should be taken with caution, the meta-analysis determined that MBL of IIP is statistically lower when PCs are applied in comparison to not placing PCs at 6-month and 12-month follow-ups. However, MBL was not statistically significant in the PCs + bone graft group when compared to only bone grafting at 6 months, and statistically higher MBL was found at 12 months in the PCs + bone graft group when compared to only bone grafting. Nonetheless, the results of this last meta-analysis should be interpreted with caution due to the results obtained in the sensitivity analysis and, therefore, more studies are needed to try to clarify this fact.

PCs seem to prevent MBL in IIP, which may lead to more predictable implant treatments in the medium term. This may be explained by the fact that PCs present antimicrobial properties and may help soft tissues to heal faster [40], thus preventing the initial MBL. Another reason that explains this result is that bone–implant contact has been histologically seen to be increased twofold in implants when PRF is used [41], or to have an 84.7% of bone–implant contact with the application of PRGF [42]. Moreover, a clinical study showed faster osseointegration in non-immediate implants placed with PRF in comparison to control group [43]. However, Taschieri et al. [26] in a retrospective study found no statistically significant differences between the use of P-PRP vs. non-use in IIP with a follow-up of up to 5 years. This fact may indicate that the application of PCs in IIP may not have a long-term benefit on MBL. On the other hand, when PCs are used in combination with a bone graft, this seems to have no benefit on MBL when compared to bone grafting alone. Nonetheless, this should be taken with caution because this meta-analysis showed high heterogeneity between the studies [33,38,39] and one of them used synthetic bone graft [38], while the others used xenografts [33,39]. Further studies focusing on this fact are needed to evaluate whether PCs in combination with bone graft have benefits in reducing MBL when compared to only bone grafting.

Regarding survival rates of IIP, this systematic review showed the same survival results when PCs were applied (100%) in comparison to the non-PCs group (100%) with at least 12 months follow-up [32,35,36,38,39]. The survival rates observed in this systematic review in both groups are high and comparable to a retrospective study that evaluated 1139 immediately loaded implants placed with PRGF, that achieved more than 96.8% survival rates with a mean follow-up of 28 months [44]. Nonetheless, further randomized controlled trials with larger sample sizes are needed to corroborate these findings.

4.2. Strength and Limitations

This systematic review has some limitations. Only RCTs and CCTs were included. Although these studies have the highest methodological quality, some information may have been lost from other studies conducted with a different design. Although most of the best journals only publish studies in English, not including manuscripts in other languages may imply language bias. The included trials presented limited samples and high risk of bias. Also, all the meta-analyses included a maximum of 3 articles, and in three of them there was one study that clearly presented the highest weight [32,39]. Another limitation is the different nomenclatures and protocols to obtain PCs that are available in the literature. In the present systematic review, both the studies that used PRP [32,33,34], as well as those studies using PRF [35,36,37,38,39], used different preparation procedures with respect to revolutions per minute and centrifugation time. Moreover, future studies should specify the size of the rotor, the angulation and design of tubes [10]. However, a previous systematic review concluded that there are not significant differences regardless of the PCs to be used [45].

Regarding the radiograph technique used to measure MBL, Al Nashar et al. [32] used orthopantomography, which is not the best way to assess interproximal bone levels. However, we decided to include this study because they considered the magnification factor in the measurements, and it has also been used to analyze the fractal dimension of the trabecular peri-implant bone [46]. The rest of studies used periapical radiographs, which are more suitable to measure MBL. It should be noted that these radiographs should be as reproducible as possible so as not to bias the results, which requires the use of positioners. Nonetheless, these radiographic techniques are limited to mesial and distal aspects, and it is, therefore, not possible to assess the buccal bone, where the resorption is always greater after a tooth extraction [47,48]. Future studies may also use three-dimensional analysis to measure this bone loss around implants [33,49]. Despite these limitations, the meta-analysis showed statistically lower MBL when PCs are applied compared to non-placing PCs for IIP with a low heterogeneity between the studies.

5. Conclusions

In conclusion, with a low certainty of evidence, PCs show a moderate effect in reducing MBL of IIPs when compared to not placing PCs. With a low certainty of evidence, PCs + bone graft show a small unimportant effect or no effect on MBL of IIPs when compared to bone grafting alone. Further randomized clinical studies are needed to confirm these results.

Supplementary Materials

The following are available online at https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/ma14164582/s1, Figure S1: Fixed-effect meta-analysis evaluating MBL in both aspects at 6 months in immediate implants procedures with PCs vs. no PCs. (MD −0.50, 95% CI [−0.57, −0.43]; p < 0.00001). (I2 = 0%), Figure S2: Fixed-effect meta-analysis evaluating MBL in both aspects at 6 months in immediate implants procedures with PCs vs. no PCs. (SMD −1.45, 95% CI [−1.96, −0.94]; p < 0.00001). (I2 = 91%), Figure S3: Random-effect meta-analysis evaluating MBL in both aspects at 6 months in immediate implants procedures with PCs vs. no PCs. (SMD −2.19, 95% CI [−4.07, −0.31]; p = 0.02). (I2 = 91%), Figure S4: Fixed-effect meta-analysis evaluating MBL in both aspects at 12 months in immediate implants procedures with PCs vs. no PCs. (SMD −1.22, 95% CI [−1.63, −0.80]; p < 0.00001). (I2 = 92%), Figure S5: Fixed-effect meta-analysis evaluating MBL in both aspects at 12 months in immediate implants procedures with PCs vs. no PCs. (MD −0.5, 95% CI [−0.57, −0.43]; p < 0.00001). (I2 = 0%), Figure S6: Random-effect meta-analysis evaluating MBL in both aspects at 12 months in immediate implants procedures with PCs vs. no PCs. (SMD −2.02, 95% CI [−3.86, −0.35]; p = 0.02). (I2 = 92%), Figure S7: Fixed-effect meta-analysis evaluating MBL in both aspects at 12 months in immediate implants procedures with PCs + bone graft group vs. only bone graft. (MD 0.10, 95% CI [−0.14, 0.33]; p = 0.42). (I2 = 84%), Figure S8: Fixed-effect meta-analysis evaluating MBL in both aspects at 12 months in immediate implants procedures with PCs + bone graft group vs. only bone graft. (SMD −0.30, 95% CI [−0.80, 0.21]; p = 0.25). (I2 = 78%), Figure S9: Random-effect meta-analysis evaluating MBL in both aspects at 12 months in immediate implants procedures with PCs + bone graft group vs. only bone graft. (SMD −0.1, 95% CI [−1.21, 1.00]; p = 0.85). (I2 = 78%), Figure S10: Fixed-effect meta-analysis evaluating MBL in both aspects at 12 months in immediate implants procedures with PCs + bone graft group vs. only bone graft. (MD 0.31, 95% CI [0.03, 0.58]; p = 0.03). (I2 = 0%), Figure S11: Random-effect meta-analysis evaluating MBL in both aspects at 12 months in immediate implants procedures with PCs + bone graft group vs. only bone graft. (SMD 0.33, 95% CI [−0.48, 1.14]; p = 0.43). (I2 = 53%), Figure S12: Fixed-effect meta-analysis evaluating MBL in both aspects at 12 months in immediate implants procedures with PCs + bone graft group vs. only bone graft. (SMD 0.18, 95% CI [−0.34, 0.70]; p = 0.49). (I2 = 53%).

Author Contributions

J.G.-S. and C.V., conceptualization, investigation, methodology, data curation, writing and review; J.G.-S., software, validation, and formal analysis. C.G.-S., A.S.-M. and J.T., writing, visualization, and review; G.H., review and supervision; R.M.L.-P., methodology, writing, visualization, review, supervision. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable for studies not involving humans or animals.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable for studies not involving humans.

Data Availability Statement

Data sharing not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Abbreviations

| IIP | immediate implant procedures |

| PCs | platelet concentrates |

| MBL | marginal bone loss |

| PRF | platelet-rich fibrin |

| PRP | platelet-rich plasma |

| L-PRF | leucocyte platelet-rich fibrin |

| L-PRP | leucocyte platelet-rich plasma |

| P-PRF | pure platelet-rich fibrin |

| P-PRP | pure platelet-rich plasma |

| PRGF | plasma rich in growth factors |

| PICO | population, intervention, comparison, outcome |

| RCT | randomized controlled trial |

| CCT | clinical controlled trial |

| SD | standard deviation |

| SE | standard error |

References

- Mello, C.C.; Lemos, C.A.A.; Verri, F.R.; Dos Santos, D.M.; Goiato, M.C.; Pellizzer, E.P. Immediate implant placement into fresh extraction sockets versus delayed implants into healed sockets: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Int. J. Oral Maxillofac. Surg. 2017, 46, 1162–1177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Kan, J.Y.; Rungcharassaeng, K.; Lozada, J. Immediate placement and provisionalization of maxillary anterior single implants: 1-year prospective study. Int. J. Oral Maxillofac. Implants 2003, 18, 31–39. [Google Scholar]

- Schropp, L.; Wenzel, A.; Kostopoulos, L.; Karring, T. Bone healing and soft tissue contour changes following single-tooth extraction: A clinical and radiographic 12-month prospective study. Int. J. Periodontics Restor. Dent. 2003, 23, 313–323. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, S.T.; Buser, D. Clinical and esthetic outcomes of implants placed in postextraction sites. Int. J. Oral Maxillofac. Implants 2009, 24, 186–217. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Ferrus, J.; Cecchinato, D.; Pjetursson, E.B.; Lang, N.P.; Sanz, M.; Lindhe, J. Factors influencing ridge alterations following immediate implant placement into extraction sockets. Clin. Oral Implants Res. 2010, 21, 22–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Del Fabbro, M.; Boggian, C.; Taschieri, S. Immediate implant placement into fresh extraction sites with chronic periapical pathologic features combined with plasma rich in growth factors: Preliminary results of single-cohort study. J. Oral Maxillofac. Surg. 2009, 67, 2476–2484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maia, L.P.; Reino, D.M.; Muglia, V.A.; Almeida, A.L.; Nanci, A.; Wazen, R.M.; de Oliveira, P.T.; Palioto, D.B.; Novaes, A.B., Jr. Influence of periodontal tissue thickness on buccal plate remodelling on immediate implants with xenograft. J. Clin. Periodontol. 2015, 42, 590–598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Hamed, F.S.; Mahri, M.; Al-Waeli, H.; Torres, J.; Badran, Z.; Tamimi, F. Regenerative Effect of Platelet Concentrates in Oral and Craniofacial Regeneration. Front. Cardiovasc. Med. 2019, 6, 126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Dohan, D.M.; Bielecki, T.; Mishra, A.; Borzini, P.; Inchingolo, F.; Sammartino, G.; Rasmusson, L.; Evert, P.A. In search of a consensus terminology in the field of platelet concentrates for surgical use: Platelet-rich plasma (PRP), plateletrich fibrin (PRF), fibrin gel polymerization and leukocytes. Curr. Pharm. Biotechnol. 2012, 13, 1131–1137. [Google Scholar]

- Miron, R.J.; Pinto, N.R.; Quirynen, M.; Ghanaati, S. Standardization of relative centrifugal forces in studies related to platelet-rich fibrin. J. Periodontol. 2019, 90, 817–820. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bennardo, F.; Liborio, F.; Barone, S.; Antonelli, A.; Buffone, C.; Fortunato, L.; Giudice, A. Efficacy of platelet-rich fibrin compared with triamcinolone acetonide as injective therapy in the treatment of symptomatic oral lichen planus: A pilot study. Clin. Oral Investig. 2021, 25, 3747–3755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anitua, E.; Murias-Freijo, A.; Alkhraisat, M.H.; Orive, G. Clinical, radiographical, and histological outcomes of plasma rich in growth factors in extraction socket: A randomized controlled clinical trial. Clin. Oral Investig. 2015, 19, 589–600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kobayashi, E.; Fujioka-Kobayashi, M.; Sculean, A.; Chappuis, V.; Buser, D.; Schaller, B.; Dőri, F.; Miron, R.J. Effects of platelet rich plasma (PRP) on human gingival fibroblast, osteoblast and periodontal ligament cell behaviour. BMC Oral Health 2017, 17, 91. [Google Scholar]

- Giudice, A.; Antonelli, A.; Muraca, D.; Fortunato, L. Usefulness of advanced-platelet rich fibrin (A-PRF) and injectable-platelet rich fibrin (i-PRF) in the management of a massive medication-related osteonecrosis of the jaw (MRONJ): A 5-years follow-up case report. Indian J. Dent. Res. 2020, 31, 813–818. [Google Scholar]

- Brancaccio, Y.; Antonelli, A.; Barone, S.; Bennardo, F.; Fortunato, L.; Giudice, A. Evaluation of local hemostatic efficacy after dental extractions in patients taking antiplatelet drugs: A randomized clinical trial. Clin. Oral Investig. 2021, 25, 1159–1167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Annunziata, M.; Guida, L.; Nastri, L.; Piccirillo, A.; Sommese, L.; Napoli, C. The role of autologous platelet concentrates in alveolar socket preservation: A systematic review. Transfus. Med. Hemother. 2018, 45, 195–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Strauss, F.J.; Stähli, A.; Gruber, R. The use of platelet-rich fibrin to enhance the outcomes of implant therapy: A systematic review. Clin. Oral Implants Res. 2018, 29, 6–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kotsovilis, S.; Markou, N.; Pepelassi, E.; Nikolidakis, D. The adjunctive use of platelet-rich plasma in the therapy of periodontal intraosseous defects: A systematic review. J. Periodontal Res. 2010, 45, 428–443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fortunato, L.; Bennardo, F.; Buffone, C.; Giudice, A. Is the application of platelet concentrates effective in the prevention and treatment of medication-related osteonecrosis of the jaw? A systematic review. J. Craniomaxillofac. Surg. 2020, 48, 268–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galindo-Moreno, P.; León-Cano, A.; Ortega-Oller, I.; Monje, A.; O Valle, F.; Catena, A. Marginal bone loss as success criterion in implant dentistry: Beyond 2 mm. Clin. Oral Implants Res. 2015, 26, e28–e34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Attanasio, F.; Antonelli, A.; Brancaccio, Y.; Averta, F.; Figliuzzi, M.M.; Fortunato, L.; Giudice, A. Primary Stability of Three Different Osteotomy Techniques in Medullary Bone: An in Vitro Study. Dent. J. 2020, 8, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Díaz-Sánchez, R.M.; Delgado-Muñoz, J.M.; Hita-Iglesias, P.; Pullen, K.T.; Serrera-Figallo, M.Á.; Torres-Lagares, D. Improvement in the Initial Implant Stability Quotient Through Use of a Modified Surgical Technique. J. Oral Implantol. 2017, 43, 186–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Su, Y.H.; Peng, B.Y.; Wang, P.D.; Feng, S.W. Evaluation of the implant stability and the marginal bone level changes during the first three months of dental implant healing process: A prospective clinical study. J. Mech. Behav. Biomed. Mater. 2020, 110, 103899. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kutkut, A.; Andreana, S.; Monaco, E., Jr. Clinical and radiographic evaluation of single-tooth dental implants placed in grafted extraction sites: A one-year report. J. Int. Acad. Periodontol. 2013, 15, 113–124. [Google Scholar]

- Rosano, G.; Taschieri, S.; Del Fabbro, M. Immediate postextraction implant placement using plasma rich in growth factors technology in maxillary premolar region: A new strategy for soft tissue management. J. Oral Implantol. 2013, 39, 98–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taschieri, S.; Lolato, A.; Ofer, M.; Testori, T.; Francetti, L.; Del Fabbro, M. Immediate post-extraction implants with or without pure platelet-rich plasma: A 5-year follow-up study. Oral Maxillofac. Surg. 2017, 21, 147–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Badran, Z.; Abdallah, M.N.; Torres, J.; Tamimi, F. Platelet concentrates for bone regeneration: Current evidence and future challenges. Platelets 2018, 29, 105–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moher, D.; Liberati, A.; Tetzlaff, J.; Altman, D.G.; Altman, D.; PRISMA Group. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: The PRISMA statement. PLoS Med. 2009, 6, e1000097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Higgins, J.P.T.; Green, S. Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions Version 5.1.0; The Cochrane Collaboration: London, UK, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Higgins, J.P.T.; Thomas, J.; Chandler, J.; Cumpston, M.; Li, T.; Page, M.J.; Welch, V.A. Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions Version 6.2; The Cochrane Collaboration: London, UK, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Higgins, J.P.T.; Thomas, J.; Chandler, J.; Cumpston, M.; Li, T.; Page, M.J.; Welch, V.A. Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions Version 6.0; The Cochrane Collaboration: London, UK, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Al Nashar, A.; Yakoob, H. Evaluation of the use of plasma rich in growth factors with immediate implant placement in periodontally compromised extraction sites: A controlled prospective study. Int. J. Oral Maxillofac. Surg. 2015, 44, 507–512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ArRejaie, A.; Al-Harbi, F.; Alagl, A.S.; Hassan, K.S. Platelet-rich plasma gel combined with bovine-derived xenograft for the treatment of dehiscence around immediately placed conventionally loaded dental implants in humans: Cone beam computed tomography and three-dimensional image evaluation. Int. J. Oral Maxillofac. Implants 2016, 31, 431–438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Gangwar, S.; Pal, U.S.; Singh, S.; Singh, R.K.; Kumar, L. Immediately placed dental implants in smokers with plasma rich in growth factor versus without plasma rich in growth factor: A comparison. Natl. J. Maxillofac. Surg. 2018, 9, 39–47. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Khan, Z.A.; Jhingran, R.; Bains, V.K.; Madan, R.; Srivastava, R.; Rizvi, I. Evaluation of peri-implant tissues around nanopore surface implants with or without platelet rich fibrin: A clinico-radiographic study. Biomed. Mater. 2018, 13, 25002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Öncü, E.; Erbeyoğlu, A.A. Enhancement of immediate implant stability and recovery using platelet-rich fibrin. Int. J. Periodontics Restor. Dent. 2019, 39, 58–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Soni, R.; Priya, A.; Agrawal, R.; Bhatnagar, A.; Kumar, L. Evaluation of efficacy of platelet-rich fibrin membrane and bone graft in coverage of immediate dental implant in esthetic zone: An in vivo study. Natl. J. Maxillofac. Surg. 2020, 11, 67–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alam, S.; Dhiman, M.; Jain, A.V.; Buthia, O.; Pruthi, G. Vertical bone implant contact around anterior immediate implants and their stability after using either alloplast or L-PRF or both in peri-Implant gap: A prospective randomized trial. J. Maxillofac. Oral Surg. 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdel-Rahman, F.H.; Salem, A.S.; El-Shinnawi, U.M.; Hammouda, N.I.; El-Kenawy, M.H. Efficacy of autogenous platelet-rich fibrin versus slowly resorbable collagen membrane with immediate implants in the esthetic zone. J. Oral Implantol. 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fabbro, M.D.; Bortolin, M.; Taschieri, S.; Ceci, C.; Weinstein, R.L. Antimicrobial properties of platelet-rich preparations. A systematic review of the current preclinical evidence. Platelets 2016, 27, 276–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Becker, W.; Lynch, S.E.; Lekholm, U.; Becker, B.E.; Caffesse, R.; Donath, K.; Sanchez, R. A comparison of PTFE membranes alone or in combination with platelet-derived growth factors and insulin-like growth factor-I or demineralized freeze-dried bone in promoting bone formation around immediate extraction socket implants. J. Periodontol. 1992, 63, 929–940. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Anitua, E.; Orive, G.; Pla, R.; Roman, P.; Serrano, V.; Andía, I. The effects of PRGF on bone regeneration and on titanium implant osseointegration in goats: A histologic and histomorphometric study. J. Biomed. Mater. Res. A 2009, 91, 158–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Öncü, E.; Alaaddinoğlu, E.E. The effect of platelet-rich fibrin on implant stability. Int. J. Oral Maxillofac. Implants 2015, 30, 578–582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Anitua, E.; Orive, G.; Aguirre, J.J.; Andía, I. Clinical outcome of immediately loaded dental implants bioactivated with plasma rich in growth factors: A 5-year retrospective study. J. Periodontol. 2008, 79, 1168–1176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moraschini, V.; Barboza, E.S. Effect of autologous platelet concentrates for alveolar socket preservation: A systematic review. Int. J. Oral Maxillofac. Surg. 2015, 44, 632–641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zeytinoğlu, M.; İlhan, B.; Dündar, N.; Boyacioğlu, H. Fractal analysis for the assessment of trabecular peri-implant alveolar bone using panoramic radiographs. Clin. Oral Investig. 2015, 19, 519–524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cardaropoli, D.; Tamagnone, L.; Roffredo, A.; Gaveglio, L. Relationship between the buccal bone plate thickness and the healing of postextraction sockets with/without ridge preservation. Int. J. Periodontics Restor. Dent. 2014, 34, 211–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Araújo, M.G.; da Silva, J.C.C.; de Mendonça, A.F.; Lindhe, J. Ridge alterations following grafting of fresh extraction sockets in man. A randomized clinical trial. Clin. Oral Implants Res. 2015, 26, 407–412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grassi, F.R.; Grassi, R.; Rapone, B.; Alemanno, G.; Balena, A.; Kalemaj, Z. Dimensional changes of buccal bone plate in immediate implants inserted through open flap, open flap and bone grafting and flapless techniques: A cone-beam computed tomography randomized controlled clinical trial. Clin. Oral Implants Res. 2019, 30, 1155–1164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).