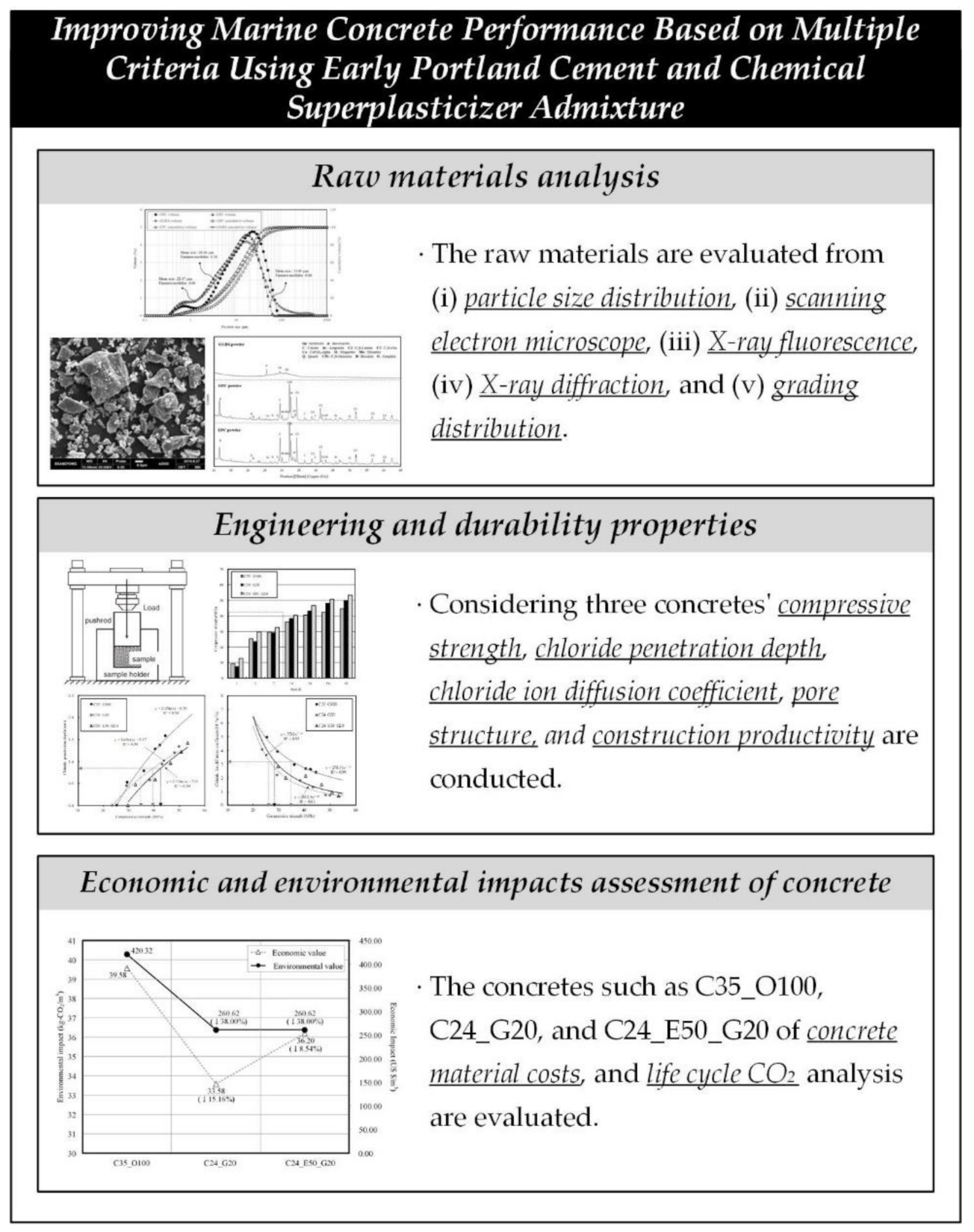

Improving Marine Concrete Performance Based on Multiple Criteria Using Early Portland Cement and Chemical Superplasticizer Admixture

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Experiment Procedure

2.1. Materials

2.2. Experiment Plan and Mix Proportions

2.3. Experiment Method

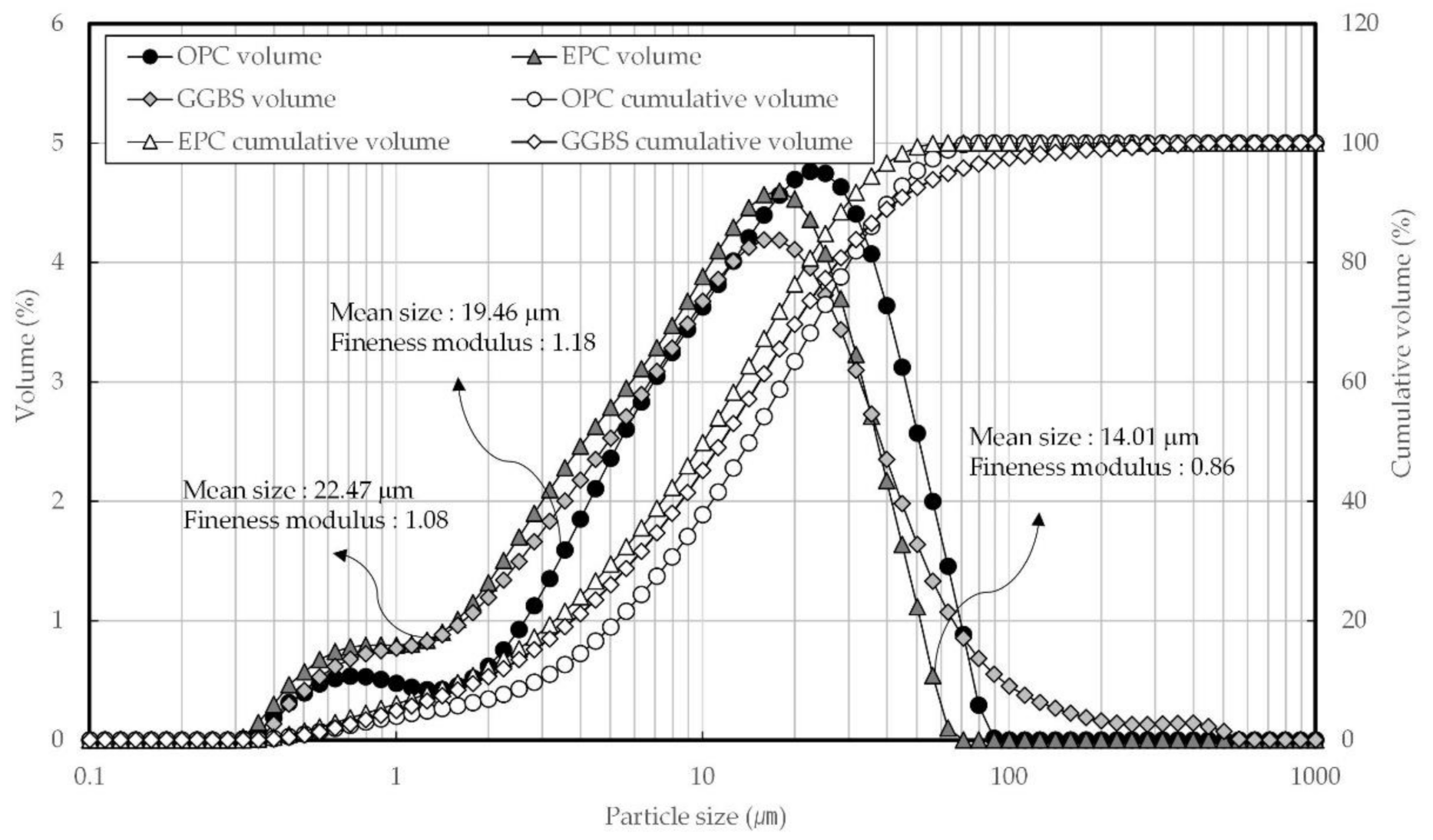

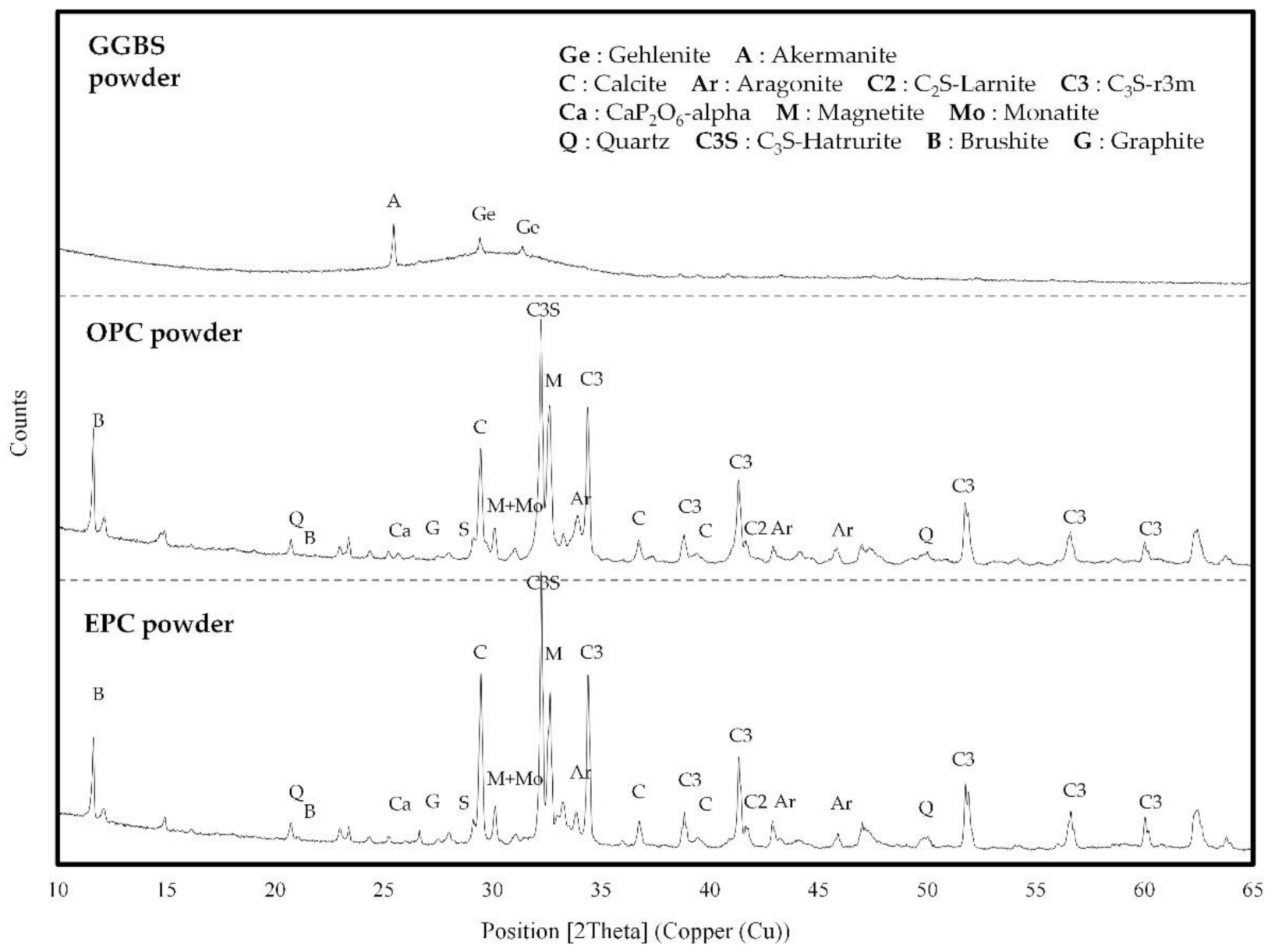

2.3.1. Binder Raw Material Analysis

2.3.2. Fresh and Hardened Properties of Concrete

2.3.3. Durability Properties of Concrete

2.3.4. Assessment of the Construction Productivity on Concrete

2.3.5. Assessment of Economic and Environmental Impacts on Concrete

- Analysis approach: In terms of the economic impact, the data of the material unit cost (USD/kg) were obtained from a concrete product manufacturing company in South Korea. In terms of the environmental impact, the data of the material unit CO2 emissions (CO2-kg) were obtained from the life cycle inventory data in South Korea. The material unit cost (USD/kg) and unit CO2 emissions (CO2-kg) are presented in Table 7 [55,56,57,58,59,60].

- Significant cost of ownership: In terms of the economic impact, to present the economic impacts, the cost of the concrete materials is displayed. The cost of concrete materials is calculated by multiplying material unit weight (refer to Table 4) with material unit cost (refer to Table 7) using Equation (4).where CC is the cost of the concrete material (USD/m3).

3. Experiment Results

3.1. Results of the Binder Raw Material Analysis

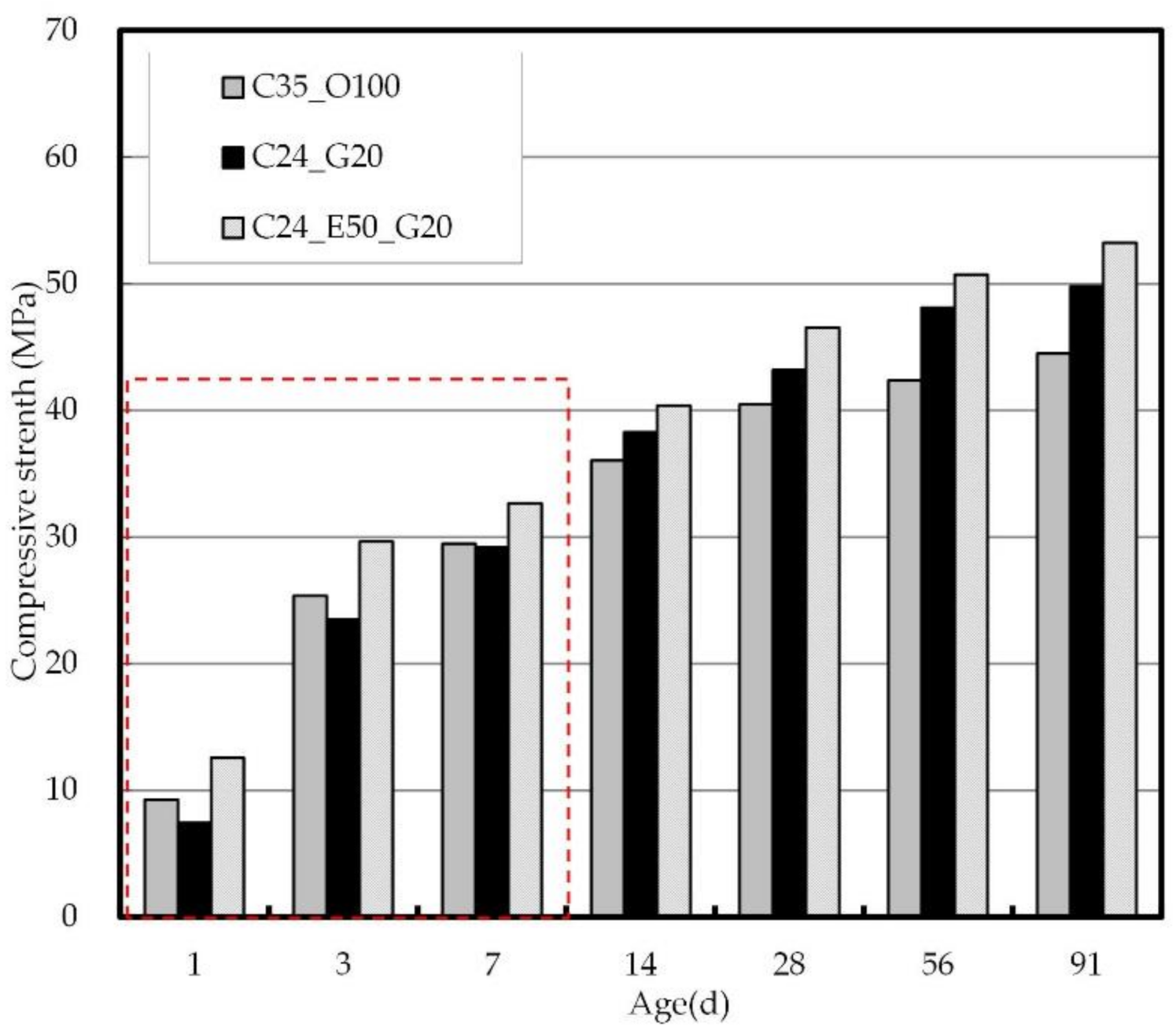

3.2. Fresh and Hardened Properties on Concrete

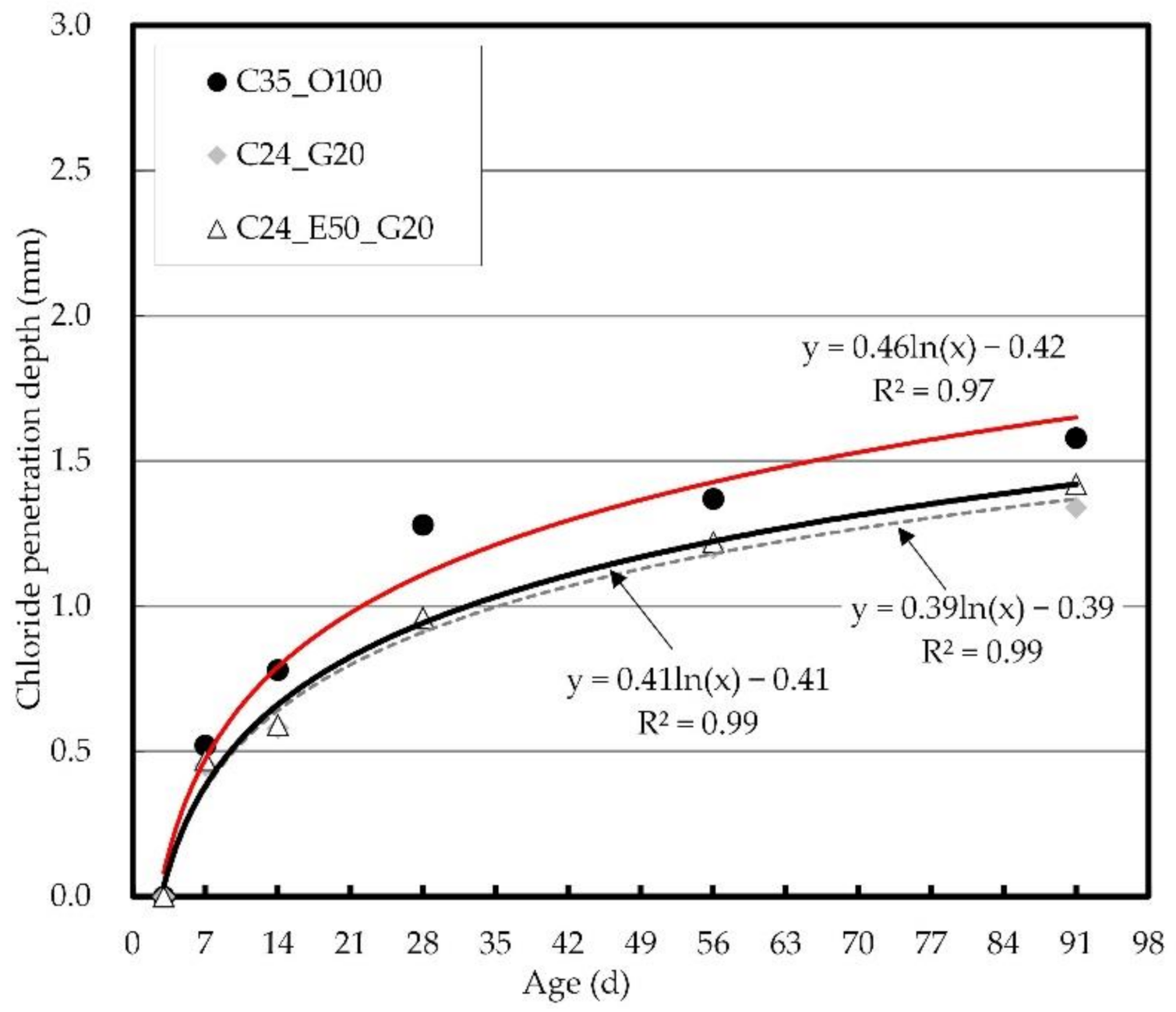

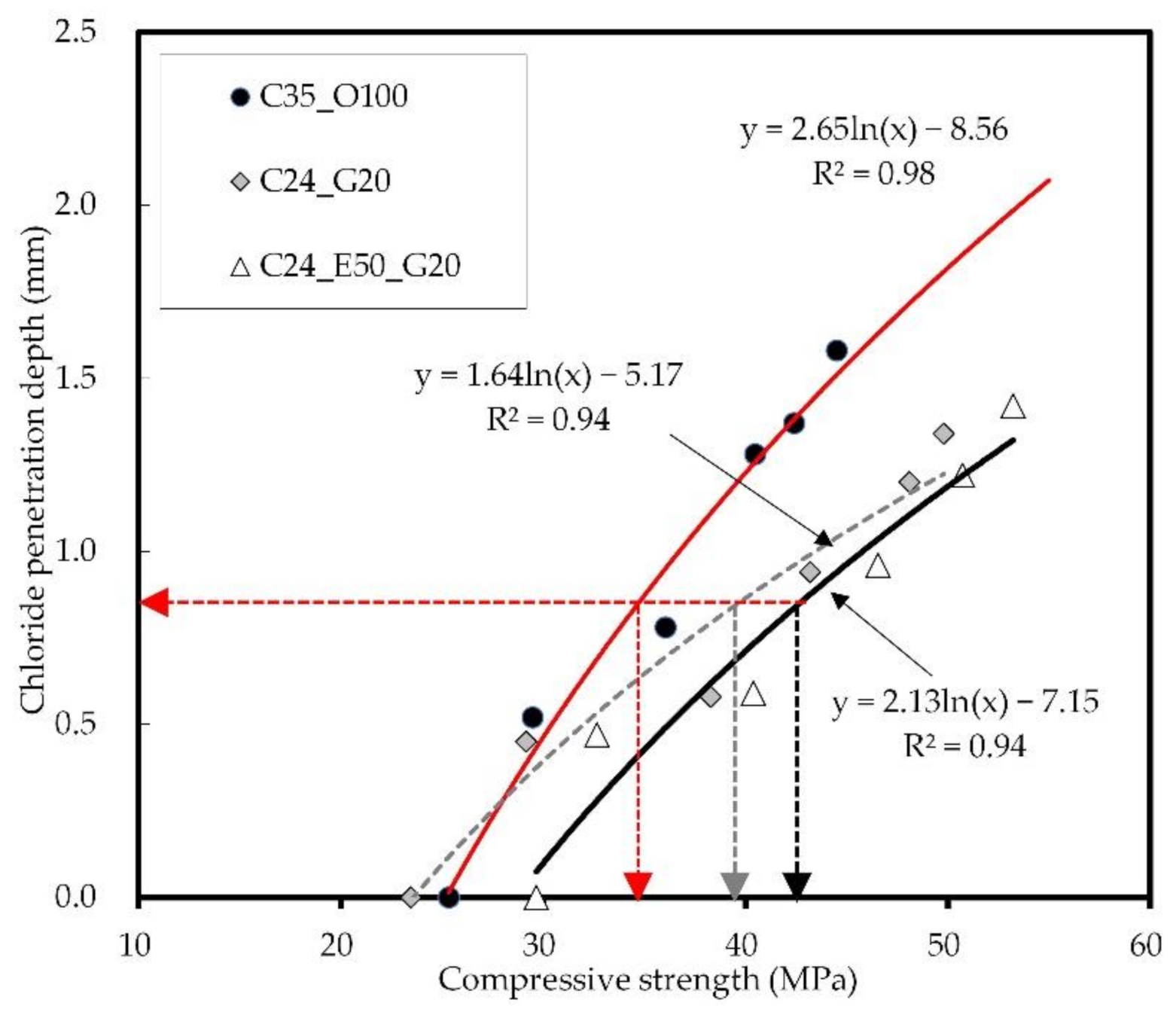

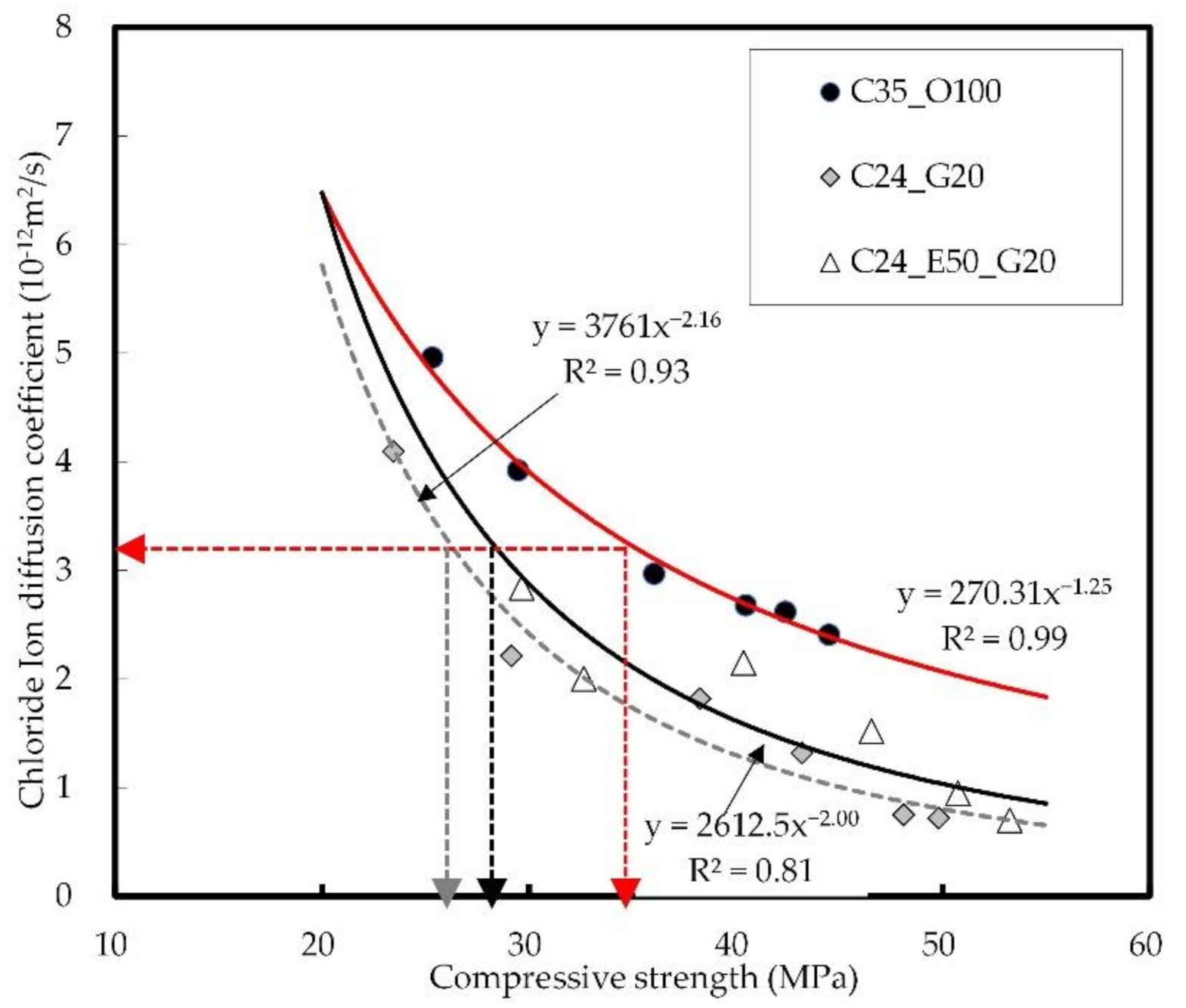

3.2.1. Chloride Penetration Depth and Chloride Ion Diffusion

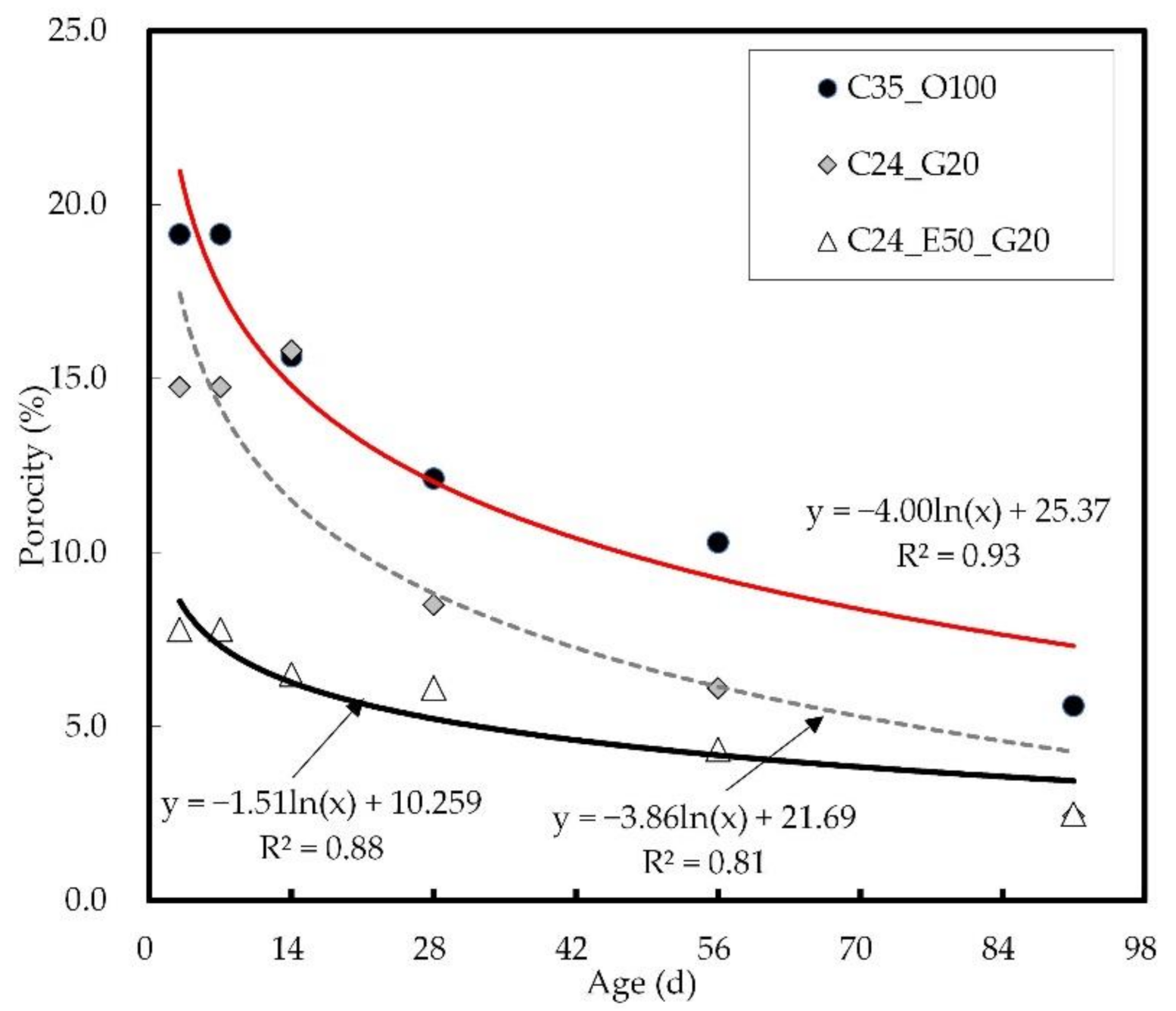

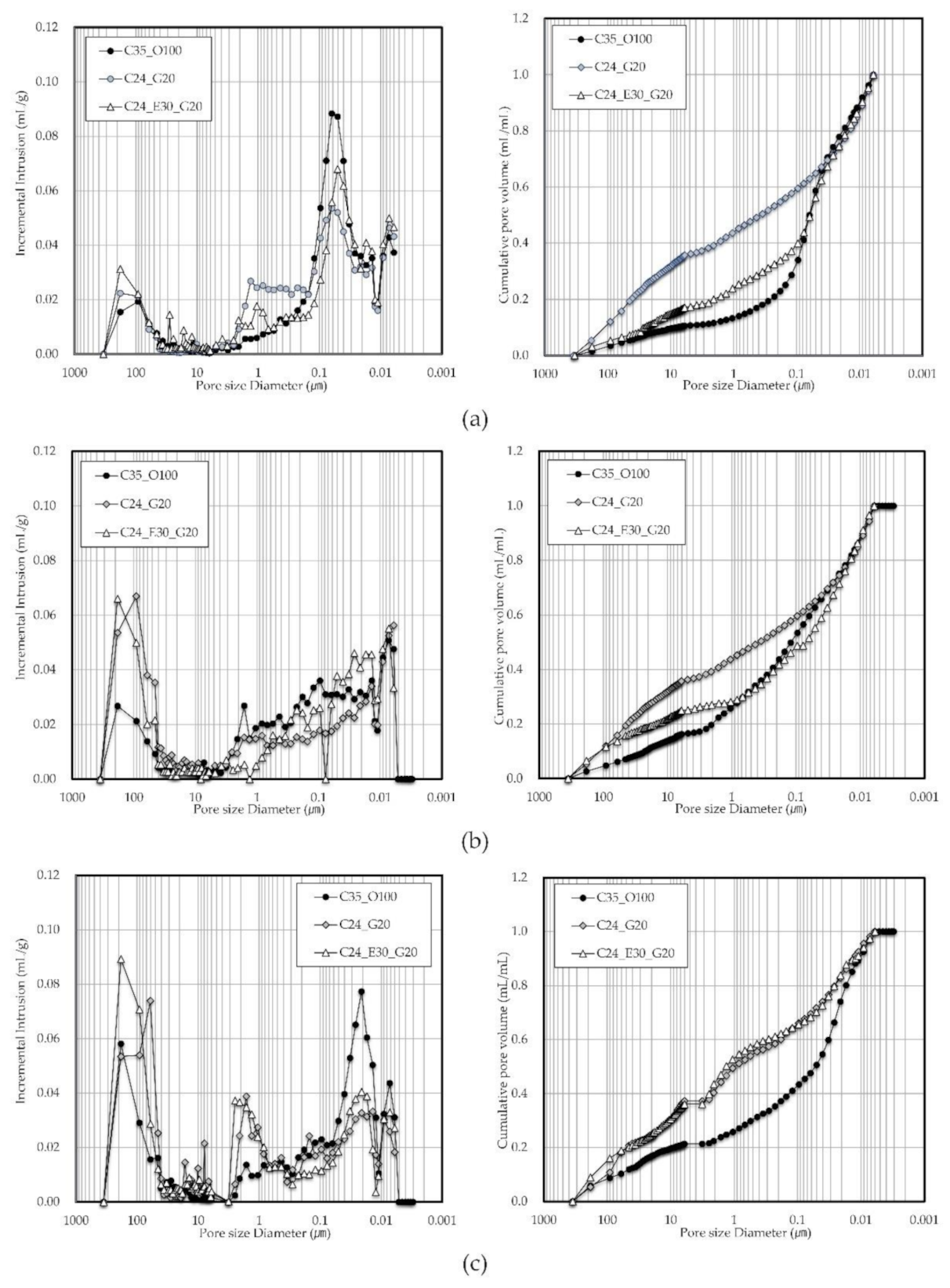

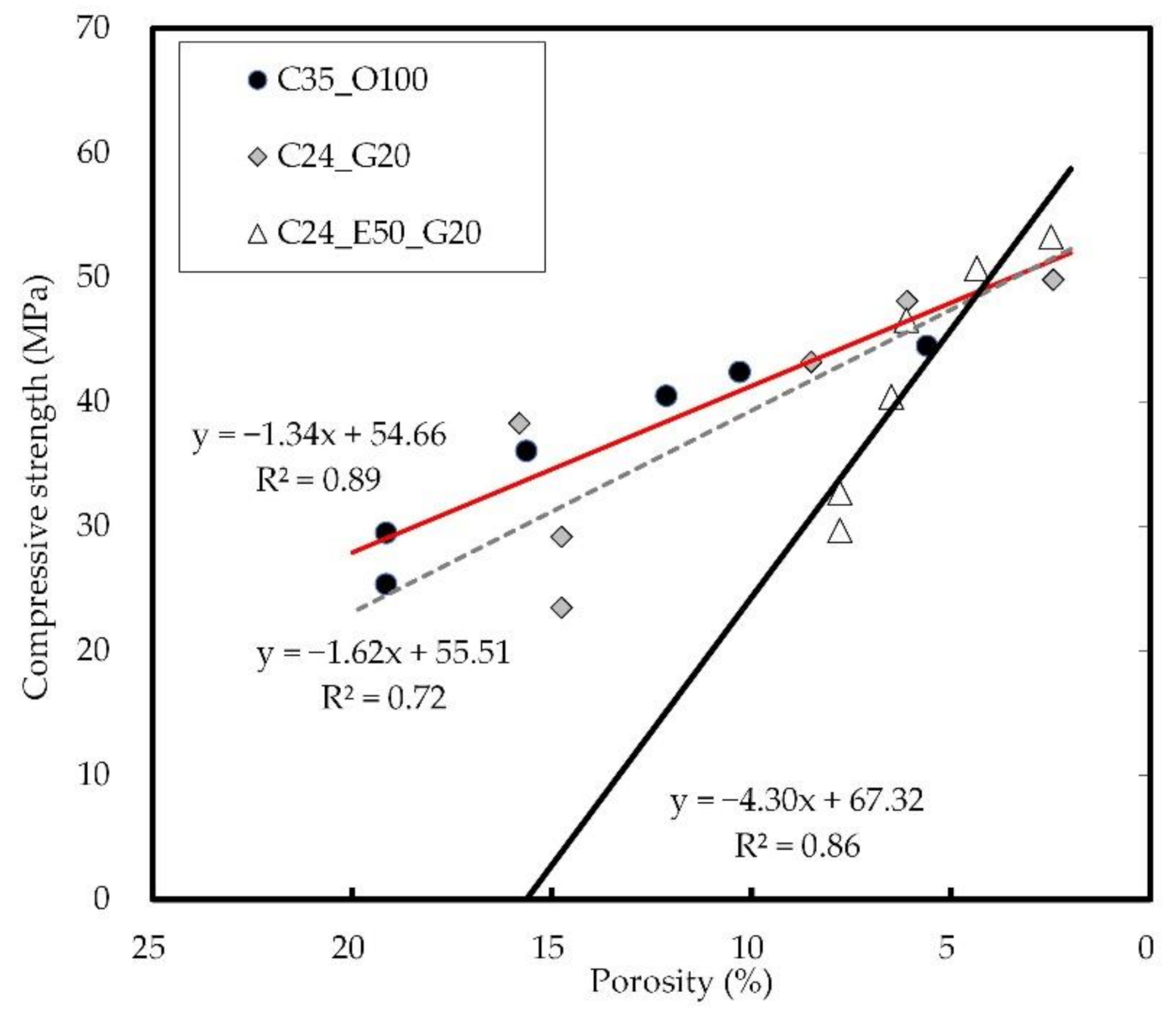

3.2.2. Porosity of Concrete

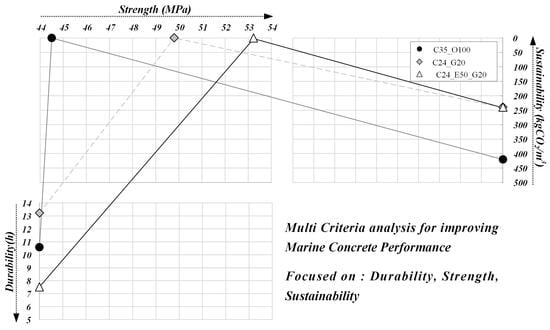

4. Discussion

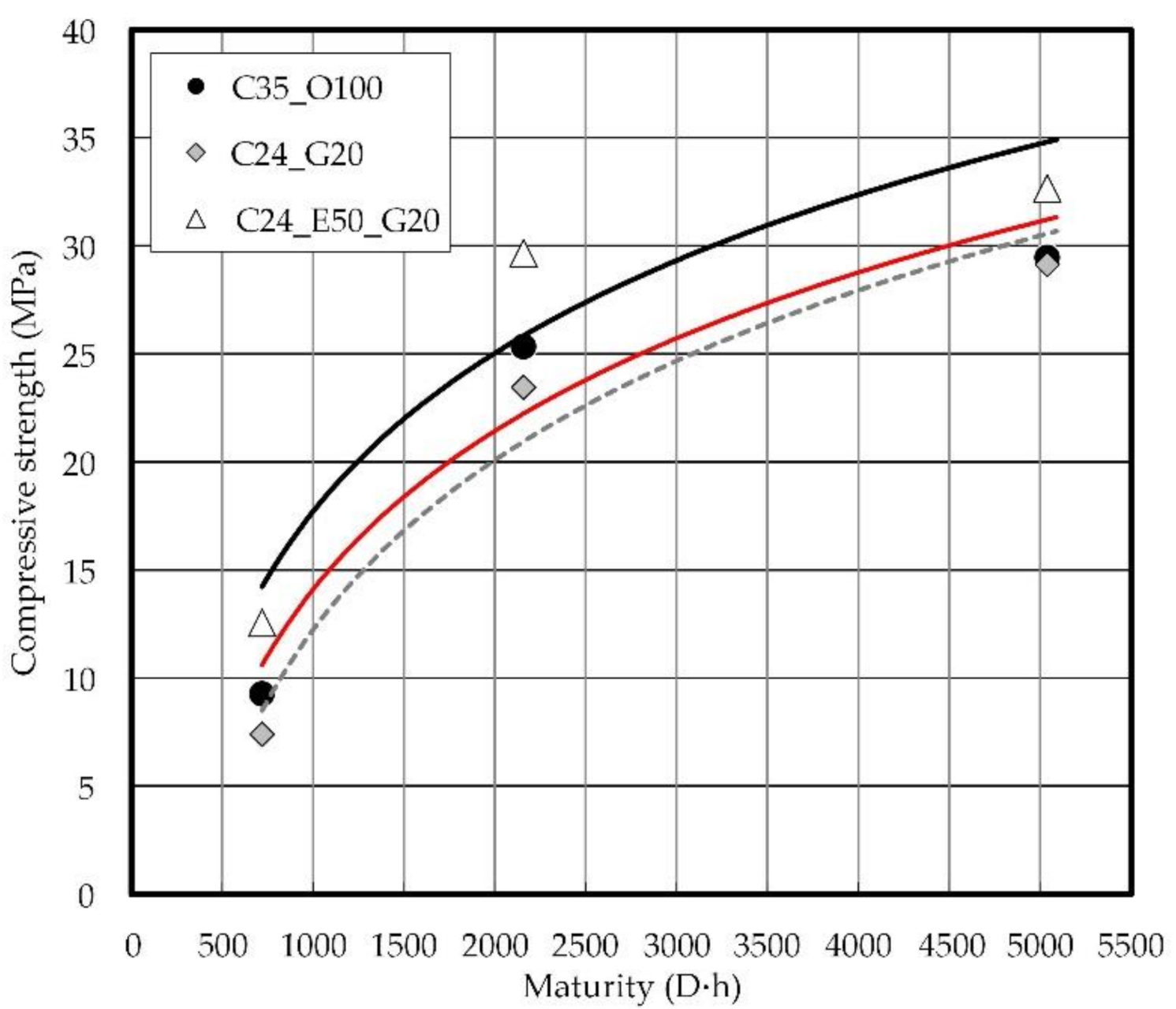

4.1. Effect of EPC and GGBS on the Compressive Strength and Chloride Resistance of Concrete

4.2. Relation between the Porosity and Compressive Strength of Concrete and Chloride Resistance

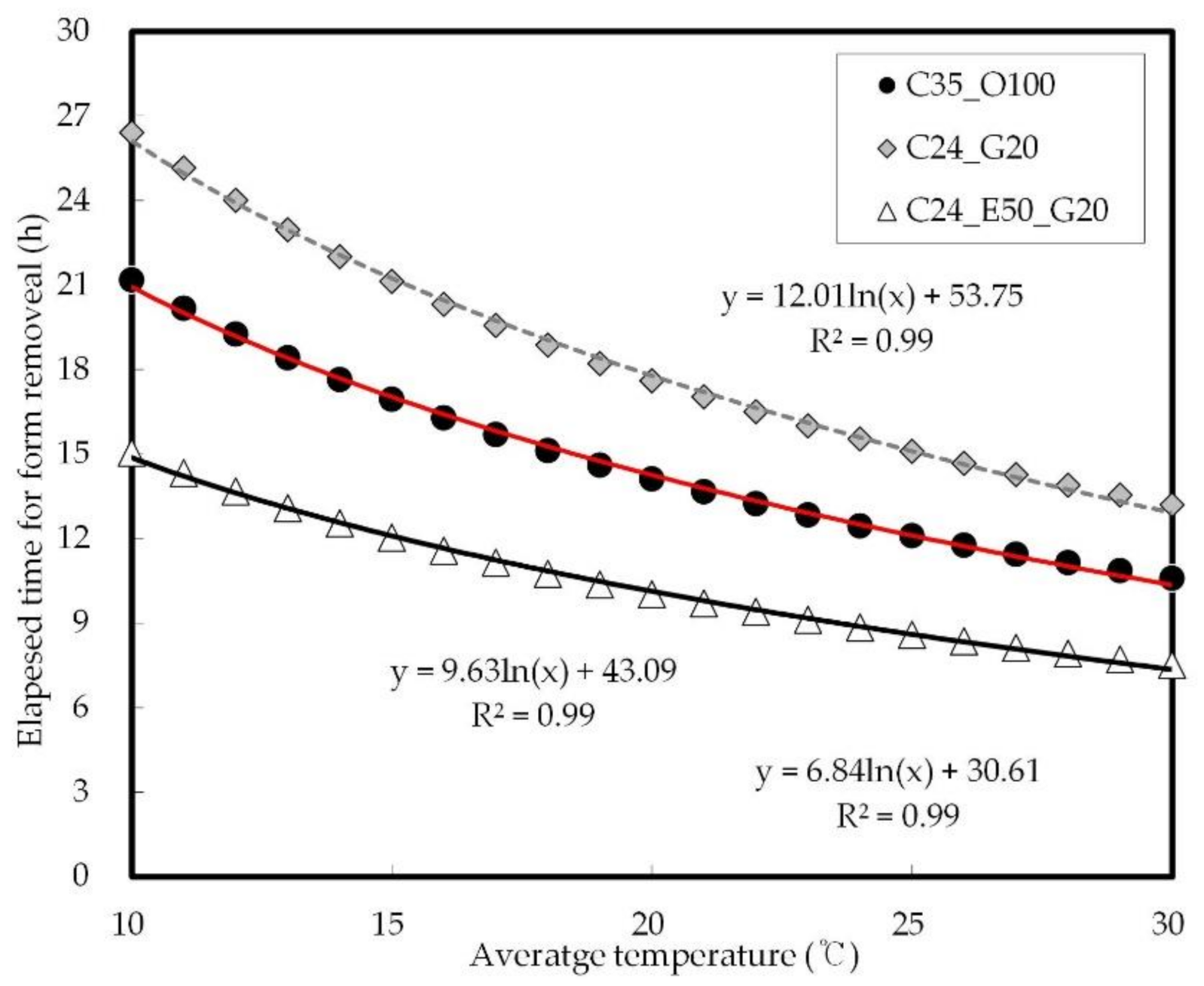

4.3. Analysis of the Removal of Forms

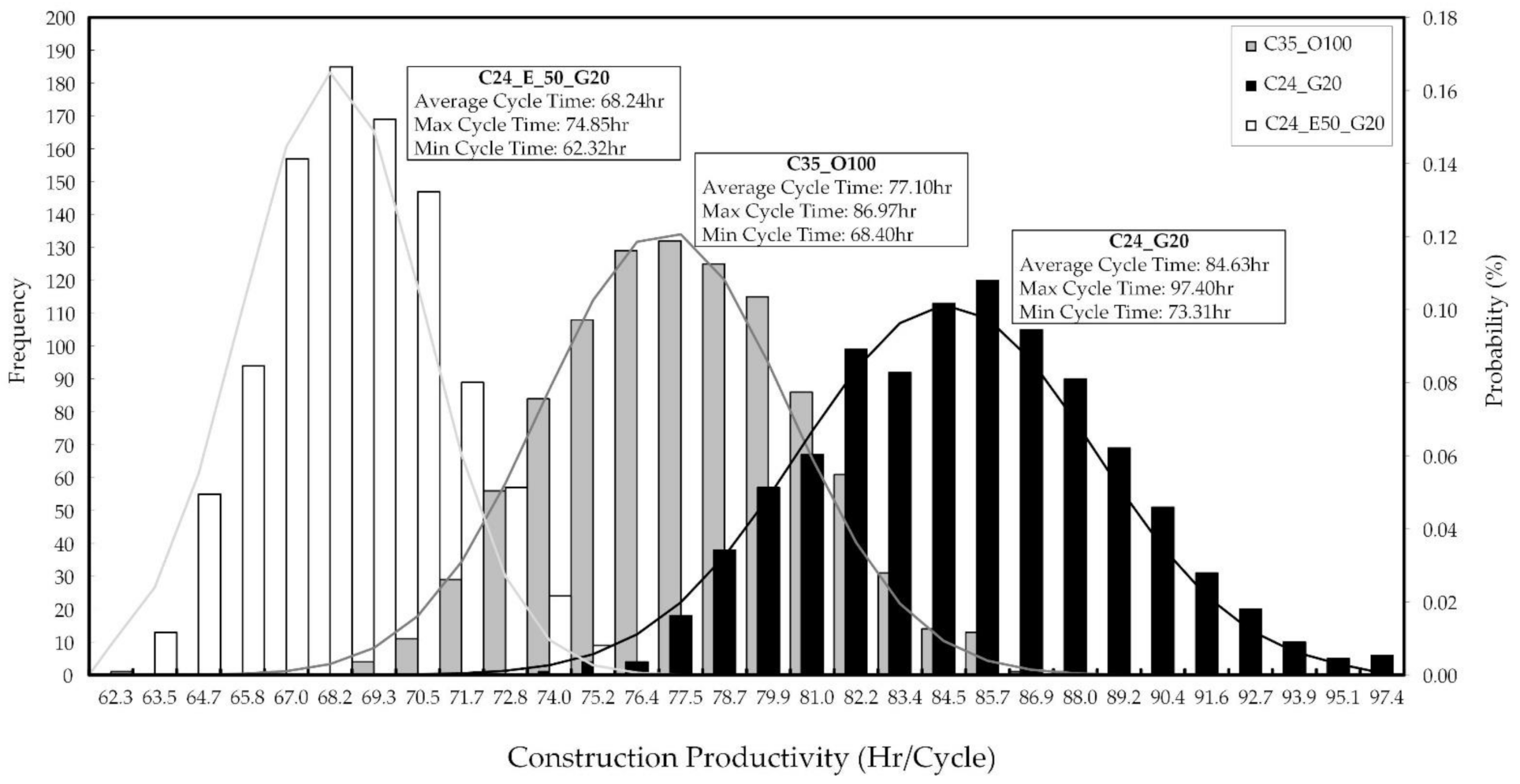

4.4. Analysis of Construction Productivity on Concrete

4.5. Analysis of Economic and Environmental Impacts of Concrete

5. Conclusions

- (1)

- The analysis of raw materials revealed that EPC can help improve the early-strength development of concrete. In addition, it was confirmed that the use of EPC and ground granulated blast-furnace slag (GGBS) as concrete binders in combination with a PC-based superplasticizer can improve the early and long-term strengths of concrete while significantly reducing the total binder.

- (2)

- The results of the chloride ion diffusion coefficient and chloride penetration depth showed that when EPC and GGBS are used, chloride resistance is improved by the watertightness of the surface and by the chloride ion binding phenomenon as the rapid strength development progresses at early ages. In particular, its chloride diffusion coefficient was decreased significantly by about 30% compared with C35_O100.

- (3)

- The evaluation of the internal porosity of concrete confirmed that the mix proportions using EPC and GGBS could reduce the total pore volume and increase the watertightness of concrete, thereby improving its chloride resistance. It was also confirmed that C24_E50_G20 and C24_G20 have different degrees of porosity at early ages but exhibit almost similar degrees of porosity at long-term ages.

- (4)

- The analysis of the effects of EPC and GGBS on the compressive strength and chloride resistance of concrete revealed that the application of a chemical superplasticizer to concrete makes it possible to reduce the cement quantity and the unit water content of the existing C35 concrete mix. Based on the study results, it is possible to secure high chloride resistance at a low strength compared to C35_100, and to reduce the time for the removal of forms by 5–9 h in terms of the early strength.

- (5)

- The construction productivity was analyzed based on the elapsed time on concretes. The results were as follows. C24_E50_G20 was 68.24 h/cycle, which was superior to other concretes in terms of construction productivity. If C24_E50_G20 was applied to the structure works in a construction project, the construction period would be decreased compared to other concretes. Moreover, it was found that when C35_O100 was replaced with C24_G20 or C24_E50_G20, the economic and environmental impacts could be reduced by up to 15.16% and 38.00%, respectively.

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- American Concrete Institute. ACI 201. 2R-16: Guide to Durable Concrete; American Concrete Institute: Farmington Hills, MI, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- American Concrete Institute. ACI 22.3R-11: Guide to Design and Construction Practices to Mitigate Corrosion of Reinforcement in Concrete Structures; American Concrete Institute: Farmington Hills, MI, USA, 2011; pp. 1–28. [Google Scholar]

- American Concrete Institute. ACI 222R-01: Protection of Metals in Concrete Against Corrosion; American Concrete Institute: Farmington Hills, MI, USA, 2002; pp. 1–41. [Google Scholar]

- Mehta, P.K.; Monteiro, P.J. Concrete Microstructure, Properties and Materials, 3rd ed.; McGraw-Hill: New York, NY, USA, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- De Medeiros-Junior, R.A.; De Lima, M.G.; De Brito, P.C.; De Medeiros, M.H.F. Chloride penetration into concrete in an offshore platform-analysis of exposure conditions. Ocean Eng. 2015, 103, 78–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glass, G.K.; Buenfeld, N.R. The influence of chloride binding on the chloride induced corrosion risk in reinforced concrete. Corros. Sci. 2000, 42, 329–344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ismail, M.; Ohtsu, M. Corrosion rate of ordinary and high-performance concrete subjected to chloride attack by AC impedance spectroscopy. Constr. Build. Mater. 2006, 20, 458–469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mingyu, H.; Fumei, L.; Mingshu, T. The thaumasite form of sulfate attack in concrete of Yongan Dam. Cem. Concr. Res. 2006, 36, 2006–2008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomas, M.; Bremner, T. Performance of lightweight aggregate concrete containing slag after 25 years in a harsh marine environment. Cem. Concr. Res. 2012, 42, 358–364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, P.; Ma, Z.; Li, X.; Lu, X.; Hou, P.; Du, P. Effect of Gypsum on Hydration and Hardening Properties of Alite Modified Calcium Sulfoaluminate Cement. Materials 2019, 12, 3131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Li, L.Y.; Page, C.L. Modelling of electrochemical chloride extraction from concrete: Influence of ionic activity coefficients. Comput. Mater. Sci. 1998, 9, 303–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- American Concrete Institute. Aci 318-99: Building Code Requirements for Structural Concrete; American Concrete Institute: Farmington Hills, MI, USA, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Architectural Institute of Japan (AIJ). Japanese Architectural Standard Specification for Reinforced Concrete Work: JASS 5; Architectural Institute of Japan: Tokyo, Japan, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Architectural Institute of Korea (AIK). Korea Architectural Standard Specification Reinforced Concrete Work: KASS 5; Architectural Institute of Korea: Seoul, Korea, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Jensen, O.M.; Hansen, P.F.; Coats, A.M.; Glasser, F.P. Chloride ingress in cement paste and mortar. Cem. Concr. Res. 1999, 29, 1497–1504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, B.; Gao, X.; Byars, E.A.; Zhou, Q. Thaumasite formation in a tunnel of Bapanxia Dam in Western China. Cem. Concr. Res. 2006, 36, 716–722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meira, G.R.; Andrade, C.; Padaratz, I.J.; Alonso, C.; Borba, J.C., Jr. Chloride penetration into concrete structures in the marine atmosphere zone—Relationship between deposition of chlorides on the wet candle and chlorides accumulated into concrete. Cem. Concr. Compos. 2007, 29, 667–676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, H.W.; Lee, C.H.; Ann, K.Y. Factors influencing chloride transport in concrete structures exposed to marine environments. Cem. Concr. Compos. 2008, 30, 113–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- British Standards Institution (BSI). Eurocode 2: Design of Concrete Structures: Part 1-1: General Rules and Rules for Buildings; British Standards Institution: London, UK, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Euro, C. CEB-FIP Model Code 1990: Design Code; Tomas Telford Ltd. 102: London, UK, 1993. [Google Scholar]

- European Committee for Standardization. EN 13670: 2009 Execution of Concrete Structures; European Standard; European Committee for Standardization: London, UK, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, J.; Lee, T.; Jeong, J.; Jeong, J. Sustainability and performance assessment of binary blended low-carbon concrete using supplementary cementitious materials. J. Clean. Prod. 2021, 280, 124373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rashad, A.M.; Sadek, D.M. An investigation on Portland cement replaced by high-volume GGBS pastes modified with micro-sized metakaolin subjected to elevated temperatures. Int. J. Sustain. Built Environ. 2017, 6, 91–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Sojobi, A.O. Evaluation of the performance of eco-friendly lightweight interlocking concrete paving units incorporating sawdust wastes and laterite. Cogent Eng. 2016, 3, 1255168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Çakır, Ö.; Aköz, F. Effect of curing conditions on the mortars with and without GGBFS. Constr. Build. Mater. 2008, 22, 308–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohan, A.; Mini, K.M. Strength and durability studies of SCC incorporating silica fume and ultra fine GGBS. Constr. Build. Mater. 2018, 171, 919–928. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uysal, M.; Sumer, M. Performance of self-compacting concrete containing different mineral admixtures. Constr. Build. Mater. 2011, 25, 4112–4120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Juradin, S.; Vlajić, D. Influence of Cement Type and Mineral Additions, Silica Fume and Metakaolin, on the Properties of Fresh and Hardened Self-compacting Concrete. Adv. Struct. Mater. 2015, 251–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kavitha, S.; Kala, T.F. Evaluation of Strength Behavior of Self-Compacting Concrete using Alccofine and GGBS as Partial Replacement of Cement. Indian J. Sci. Technol. 2016, 9, 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, C.H.; Wu, C.H.; Lin, S.K.; Yen, T. Effect of Slag Particle Size on Fracture Toughness of Concrete. Appl. Sci. 2019, 9, 805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Ganesh, P.; Murthy, A.R. Tensile behaviour and durability aspects of sustainable ultra-high performance concrete incorporated with GGBS as cementitious material. Constr. Build. Mater. 2019, 197, 667–680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suda, V.R.; Rao, P.S. Experimental investigation on optimum usage of Micro silica and GGBS for the strength characteristics of concrete. Mater. Today Proc. 2020, 27, 805–811. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Homayoonmehr, R.; Ramezanianpour, A.A.; Mirdarsoltany, M. Influence of metakaolin on fresh properties, mechanical properties and corrosion resistance of concrete and its sustainability issues: A review. J. Build. Eng. 2021, 44, 103011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hrabová, K.; Lehner, P.; Ghosh, P.; Konečný, P.; Teplý, B. Sustainability Levels in Comparison with Mechanical Properties and Durability of Pumice High-Performance Concrete. Appl. Sci. 2021, 11, 4964. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Irico, S.; Qvaeschning, D.; Mutke, S.; Deuse, T.; Gastaldi, D.; Canonico, F. Durability of high performance self-compacting concrete with granulometrically optimized slag cement. Constr. Build. Mater. 2021, 298, 123836. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- American Society of Testing and Materials. ASTM C204. Standard test methods for fineness of hydraulic cement by air-permeability apparatus. In ASTM C204, Annual Book of ASTM Standards; American Society of Testing and Materials: West Conshohocken, PA, USA, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- American Society of Testing and Materials. Standard guide for examination of hardened concrete using scanning electron microscopy. In ASTM C1723-16, Annual Book of ASTM Standards; American Society of Testing and Materials: West Conshohocken, PA, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- American Society of Testing and Materials. Standard Test Methods for Chemical Analysis of Hydraulic Cement. In ASTM C114-18, Annual Book of ASTM Standards; American Society of Testing and Materials: West Conshohocken, PA, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- American Society of Testing and Materials. Standard Test Method for Determination of the Proportion of Phases in Portland Cement and Portland-Cement Clinker Using X-Ray Powder Diffraction Analysis. In ASTM C1365-18, Annual Book of ASTM Standards; American Society of Testing and Materials: West Conshohocken, PA, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- American Society of Testing and Materials. Standard Test Method for Slump of Hydraulic-Cement Concrete, ASTM C143/C143M. In Annual Book of ASTM Standards; American Society of Testing and Materials: West Conshohocken, PA, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- American Society of Testing and Materials. Standard Test Method for Air Content of Freshly Mixed Concrete by the Pressure Method, ASTM C231/C231M. In Annual Book of ASTM Standards; American Society of Testing and Materials: West Conshohocken, PA, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- American Society of Testing and Materials. Standard Test Method for Compressive Strength of Concrete Cylinders Cast in Place in Cylindrical Molds, ASTM C873/C873M. In Annual Book of ASTM Standards; American Society of Testing and Materials: West Conshohocken, PA, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- American Society of Testing and Materials. Standard Test Method for Compressive Strength of Cylindrical Concrete Specimens, ASTM C39/C39M. In Annual Book of ASTM Standards; American Society of Testing and Materials: West Conshohocken, PA, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- NT BUILD 492. Concrete, Mortar and Cement-Based Repair Materials: Chloride Migration Coefficient from Non-Steady-State Migration Experiments; Nordtest Method: Espoo, Finland, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Nordtest, N.T. Concrete, Hardened: Accelerated Chloride Penetration; Nordtest NT Build: Espoo, Finland, 1995; p. 443. [Google Scholar]

- American Society of Testing and Materials. Standard Test Method for Determination of Pore Volume and Pore Volume Distribution of Soil and Rock by Mercury Intrusion Porosimetry, ASTM D4404. In Annual Book of ASTM Standards; American Society of Testing and Materials: West Conshohocken, PA, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Jeong, J.; Hong, T.; Ji, C.; Kim, J.; Lee, M.; Jeong, K.; Lee, S. An integrated evaluation of productivity, cost and CO2 emission between prefabricated and conventional columns. J. Clean. Prod. 2017, 142, 2393–2406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arashpour, M.; Arashpour, M. Analysis of Workflow Variability and Its Impacts on Productivity and Performance in Construction of Multistory Buildings. J. Manage. Eng. 2015, 31, 04015006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- An, S.; Ji, S.; Hyun, C.; Han, S. A model-based productivity improvement of reinforced concrete work in a multi-housing project. KSCE J. Civ. Eng. 2015, 19, 1183–1192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Korean Statistical Information Service (KOSIS). Available online: https://kosis.kr (accessed on 1 May 2021).

- Martinez, J.C. STROBOSCOPE: State and Resource Based Simulation of Construction Processes. Ph.D. Thesis, University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, MI, USA, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Jeong, J.; Hong, T.; Kim, J.; Chae, M.; Ji, C. Multi-criteria analysis of a self-consumption strategy for building sectors focused on ground source heat pump systems. J. Clean. Prod. 2018, 186, 68–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weng, Y.; Li, M.; Ruan, S.; Wong, T.N.; Tan, M.J.; Yeong, K.L.O.; Qian, S. Comparative economic, environmental and productivity assessment of a concrete bathroom unit fabricated through 3D printing and a precast approach. J. Clean. Prod. 2020, 261, 121245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poulikidou, S.; Jerpdal, L.; Björklund, A.; Åkermo, M. Environmental performance of self-reinforced composites in automotive applications—Case study on a heavy truck component. Mater. Des. 2016, 103, 321–329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poulikidou, S.; Schneider, C.; Björklund, A.; Kazemahvazi, S.; Wennhage, P.; Zenkert, D. A material selection approach to evaluate material substitution for minimizing the life cycle environmental impact of vehicles. Mater. Des. 2015, 83, 704–712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Kim, J.; Hong, T.; Jeong, J.; Koo, C.; Jeong, K.; Lee, M. Multi-criteria decision support system of the photovoltaic and solar thermal energy systems using the multi-objective optimization algorithm. Sci. Total Environ. 2019, 659, 1100–1114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, T.H.; Tae, S.H.; Park, J.H.; Lee, K.J. A study on Reduction of Concrete CO2 Emissions by Substitution of Blast furnace slag. In Proceedings of the Korea Concrete Institute Conference, Gyeongju, South Korea, 3 May 2012; pp. 191–192. [Google Scholar]

- Demertzi, M.; Garrido, A.; Dias, A.C.; Arroja, L. Environmental performance of a cork floating floor. Mater. Des. 2015, 82, 317–325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hassan, O.A.; Öberg, F.; Gezelius, E. Cross-laminated timber flooring and concrete slab flooring: A comparative study of structural design, economic and environmental consequences. J. Build. Eng. 2019, 26, 100881. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Korea Environmental Industry and Technology Institute (KEITI). Available online: http://www.epd.or.kr (accessed on 15 December 2020).

- Lee, J.; Lee, T. Effects of High CaO Fly Ash and Sulfate Activator as a Finer Binder for Cementless Grouting Material. Materials 2019, 12, 3664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Lee, J.; Lee, T. Influences of Chemical Composition and Fineness on the Development of Concrete Strength by Curing Conditions. Materials 2019, 12, 4061. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Li, D.; Li, L.Y.; Wang, X. Chloride diffusion model for concrete in marine environment with considering binding effect. Mar. Struct. 2019, 66, 44–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Wang, Y.; Yu, J.; Wang, J.; Guan, X. Effects of Aluminum Sulfate and Quicklime/Fluorgypsum Ratio on the Properties of Calcium Sulfoaluminate (CSA) Cement-Based Double Liquid Grouting Materials. Materials 2019, 12, 1222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Bost, P.; Regnier, M.; Horgnies, M. Comparison of the accelerating effect of various additions on the early hydration of Portland cement. Constr. Build. Mater. 2016, 113, 290–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, M.P.; Mini, K.; Rangarajan, M. Ultrafine GGBS and calcium nitrate as concrete admixtures for improved mechanical properties and corrosion resistance. Constr. Build. Mater. 2018, 182, 249–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, R.; Cai, Y.; Wang, C.; Huang, X. Study of chloride binding and diffusion in GGBS concrete. Cem. Concr. Res. 2003, 33, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, X.; Shi, C.; Yuan, Q.; Zhang, J.; De Schutter, G. Changes of pore structure and chloride content in cement pastes after pore solution expression. Cem. Concr. Compos. 2020, 106, 103465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sakai, Y. Relationship between pore structure and chloride diffusion in cementitious materials. Constr. Build. Mater. 2019, 229, 116868. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- American Society of Testing and Materials. Standard Practice for Estimating Concrete Strength by the Maturity Method, ASTM C1074. In Annual Book of ASTM Standards; American Society of Testing and Materials: West Conshohocken, PA, USA, 2019; pp. 1–10. [Google Scholar]

- Berg, A.C.; Bank, L.C.; Oliva, M.G.; Russell, J.S. Construction and cost analysis of an FRP reinforced concrete bridge deck. Constr. Build. Mater. 2006, 20, 515–526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Material | Property | |

|---|---|---|

| OPC | ASTM type I ordinary Portland cement Fineness: 330 m2/kg, density: 3150 kg/m3 | |

| EPC | ASTM type III early Portland cement Fineness: 488 m2/kg, density: 3160 kg/m3 | |

| GGBS | Ground granulated blast-furnace slag Fineness: 430 m2/kg density: 2860 kg/m3 | |

| Fine aggregate | S1 | Sea sand, size: 5 mm Fineness modulus: 2.01, density: 2600 kg/m3, absorption: 0.79% |

| S2 | Crushed sand, size: 5 mm Fineness modulus: 3.29, density: 2570 kg/m3, absorption: 0.87% | |

| Coarse aggregate | Crushed granitic aggregate Size: 25 mm, density: 2600 kg/m3, absorption: 0.76% | |

| Chemical admixture | NP | Naphthalene superplasticizer, density: 1220 kg/m3 |

| PC | Polycarboxylic superplasticizer, density: 1260 kg/m3 | |

| Materials | Chemical Compositions (%) | L.O.I. (4) | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CaO | Al2O3 | SiO2 | MgO | K2O | Fe2O3 | SO3 | Etc. | ||

| OPC (1) | 60.34 | 4.85 | 19.82 | 3.83 | 1.08 | 3.3 | 2.9 | 0.86 | 3.02 |

| EPC (2) | 61.44 | 4.72 | 20.33 | 2.95 | 0.95 | 3.42 | 3.73 | 0.79 | 1.67 |

| GGBS (3) | 44.9 | 13 | 35.4 | 5.01 | 0.37 | 0.47 | 1.31 | - | 0.69 |

| Type | Mix No. | W/B | Unit Weight of Binder (kg/m3) | Replacement of Binder (%) | Chemical Admixture | Evaluation Item | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| OPC | EPC | GGBS | ||||||

| I. Raw material | - | - | - | - | - | - | - |

|

| II. Concrete | C35_O100 (1) C24_G20 C24_E50_G20 | 0.42 0.48 0.48 | C35/444 (2) C24/340 C24/340 | 100 80 30 | 50 | 20 20 | NP PC PC |

|

| Mix ID. | W/B (1) | S/a (2) (%) | Unit Weight (kg/m3) | NP (B × wt.%) | PC (B × wt.%) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| W (3) | C (4) | EPC | GGBS | S (5) | G (6) | |||||

| C35_O100 | 0.42 | 48.5 | 185 | 444 | - | - | 788 | 842 | 0.7 | - |

| C24_G20 | 0.48 | 48.5 | 163 | 272 | - | 68 | 854 | 913 | - | 0.7 |

| C24_E50_G20 | 0.48 | 48.5 | 163 | 102 | 170 | 68 | 854 | 913 | - | 0.7 |

| Items | Materials | Evaluation Items | Test Methods |

|---|---|---|---|

| Raw material analysis | OPC EPC GGBS | Particle size distribution (%) | ASTM C204 |

| Scanning electron microscope | ASTM C1723 | ||

| X-ray fluorescence | ASTM C114 | ||

| X-ray diffraction | ASTM C457 |

| Series | Evaluation Item | Test Method |

|---|---|---|

| Durability properties analysis | Chloride ion diffusion coefficient (10−12 m2/s) | NT Build 492 |

| Chloride penetration depth (mm) | NT Build 443 | |

| Porosity (%) | ASTM D4404 | |

| Maturity (D∙h) | ASTM C1074 |

| Class | Materials | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| W (1) | C (2) | EPC (3) | S (4) | G (5) | |

| Material unit cost (US $/kg) | 8.11 × 10−4 | 5.76 × 10−2 | 7.30 × 10−2 | 8.91 × 10−3 | 8.11 × 10−3 |

| CO2 emission (CO2-kg) | 1.02 × 10−4 | 9.44 × 10−1 | 3.77 × 10−2 | 5.03 × 10−4 | 9.18 × 10−4 |

| Mix ID. | Slump (mm) | Air Contents (%) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Initial Time | After 60 min | Initial Time | After 60 min | |

| C35_O100 | 185 | 150 | 4.6 | 4.2 |

| C24_G20 | 180 | 165 | 4.7 | 4.3 |

| C24_E50_G20 | 180 | 165 | 4.6 | 4.5 |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Lee, T.; Lee, J.; Jeong, J.; Jeong, J. Improving Marine Concrete Performance Based on Multiple Criteria Using Early Portland Cement and Chemical Superplasticizer Admixture. Materials 2021, 14, 4903. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma14174903

Lee T, Lee J, Jeong J, Jeong J. Improving Marine Concrete Performance Based on Multiple Criteria Using Early Portland Cement and Chemical Superplasticizer Admixture. Materials. 2021; 14(17):4903. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma14174903

Chicago/Turabian StyleLee, Taegyu, Jaehyun Lee, Jaewook Jeong, and Jaemin Jeong. 2021. "Improving Marine Concrete Performance Based on Multiple Criteria Using Early Portland Cement and Chemical Superplasticizer Admixture" Materials 14, no. 17: 4903. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma14174903

APA StyleLee, T., Lee, J., Jeong, J., & Jeong, J. (2021). Improving Marine Concrete Performance Based on Multiple Criteria Using Early Portland Cement and Chemical Superplasticizer Admixture. Materials, 14(17), 4903. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma14174903