A pH-Responsive Polycaprolactone–Copper Peroxide Composite Coating Fabricated via Suspension Flame Spraying for Antimicrobial Applications

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Materials and Reagents

2.2. Sample Preparation

2.3. Sample Characterization

2.4. Colorimetric Determination of Peroxo Groups

2.5. pH-Responsive Release of Copper Ions

2.6. In Vitro Antibacterial Effect of PCL-CuO2 Coatings

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Morphological Characterization of PCL and CuO2 Powders

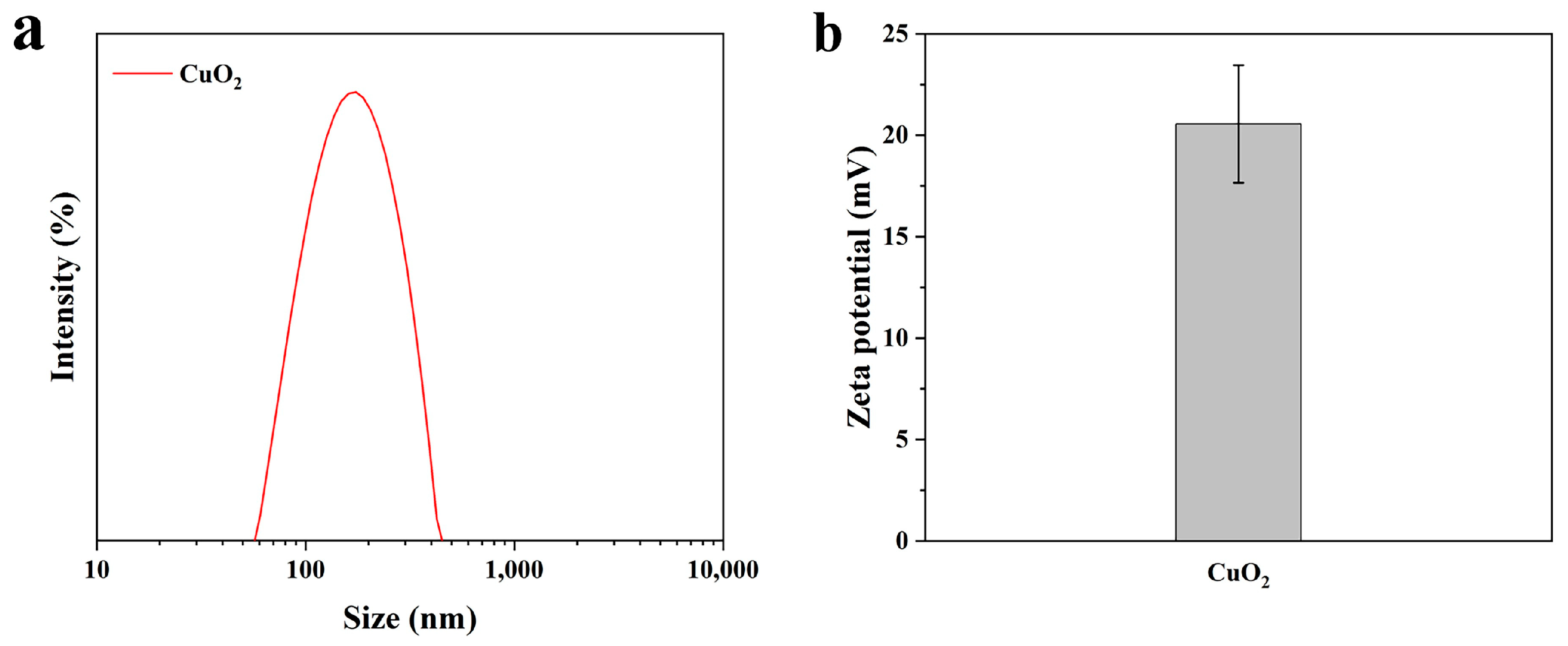

3.2. The Particle size and Zeta Potential of CuO2

3.3. XPS Analysis of CuO2 Powders

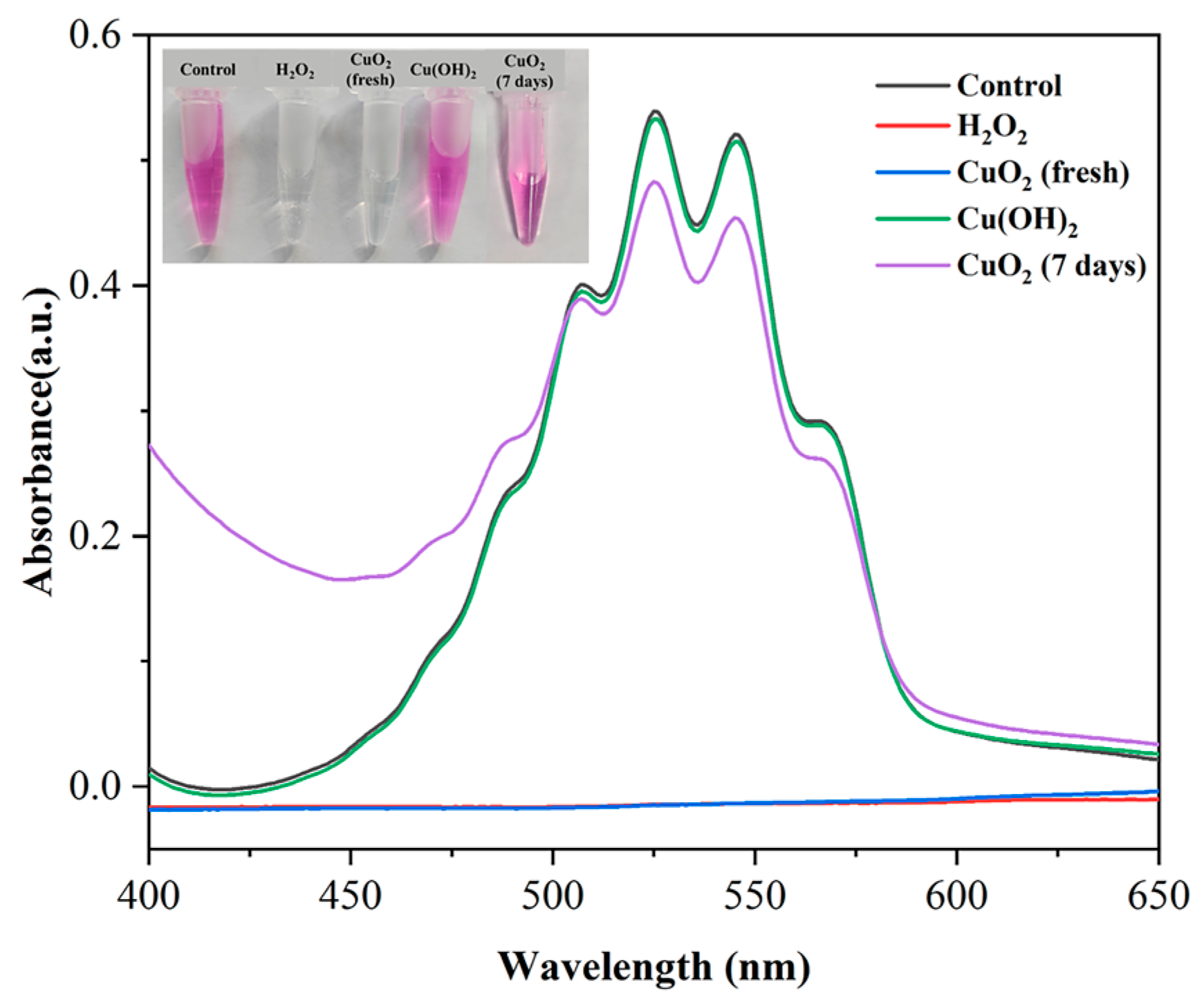

3.4. Potassium Permanganate Colorimetric Analysis of Synthesized CuO2

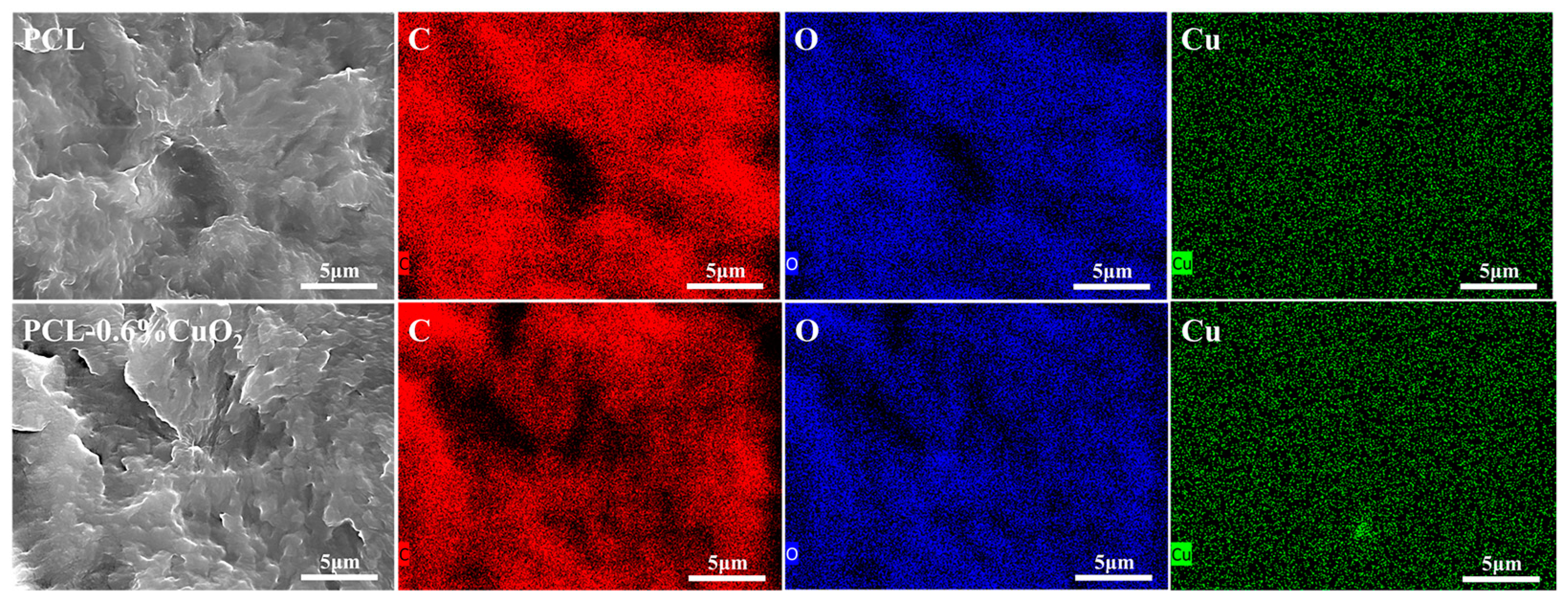

3.5. SEM and EDX Analysis of the PCL and PCL-CuO2 Coatings

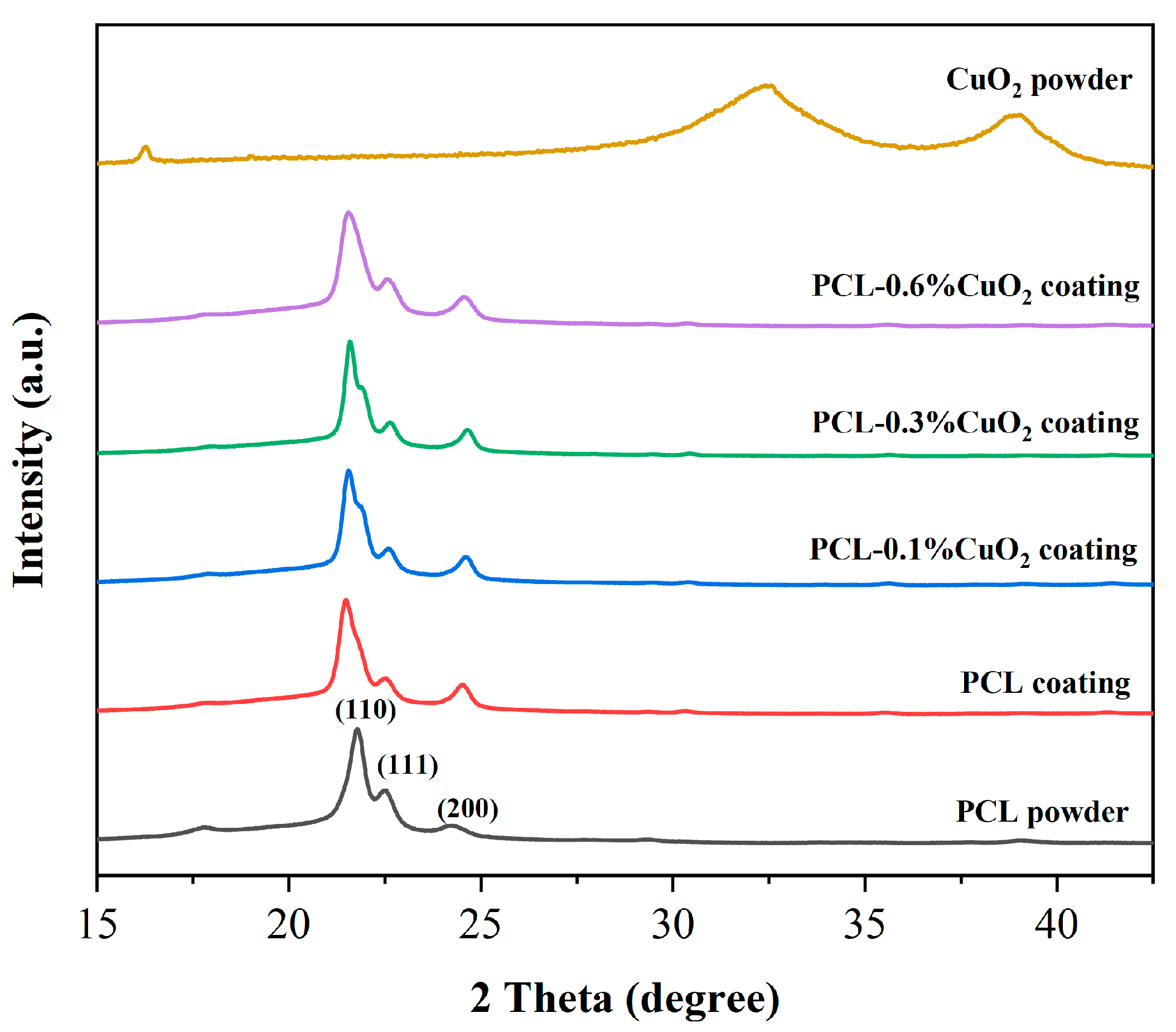

3.6. XRD Analysis of the Powders and Coatings

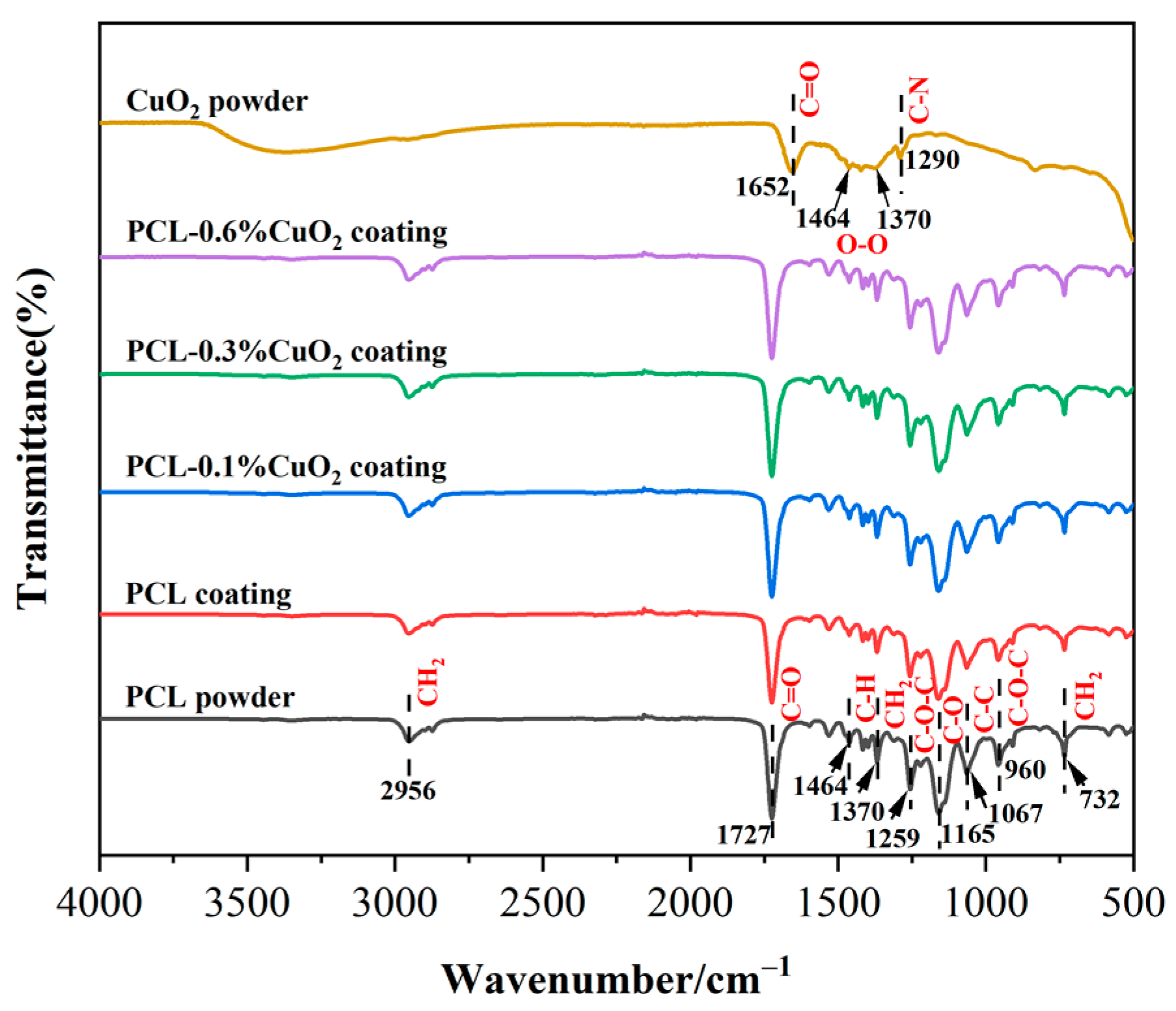

3.7. FT-IR Analysis of the Powders and Coatings

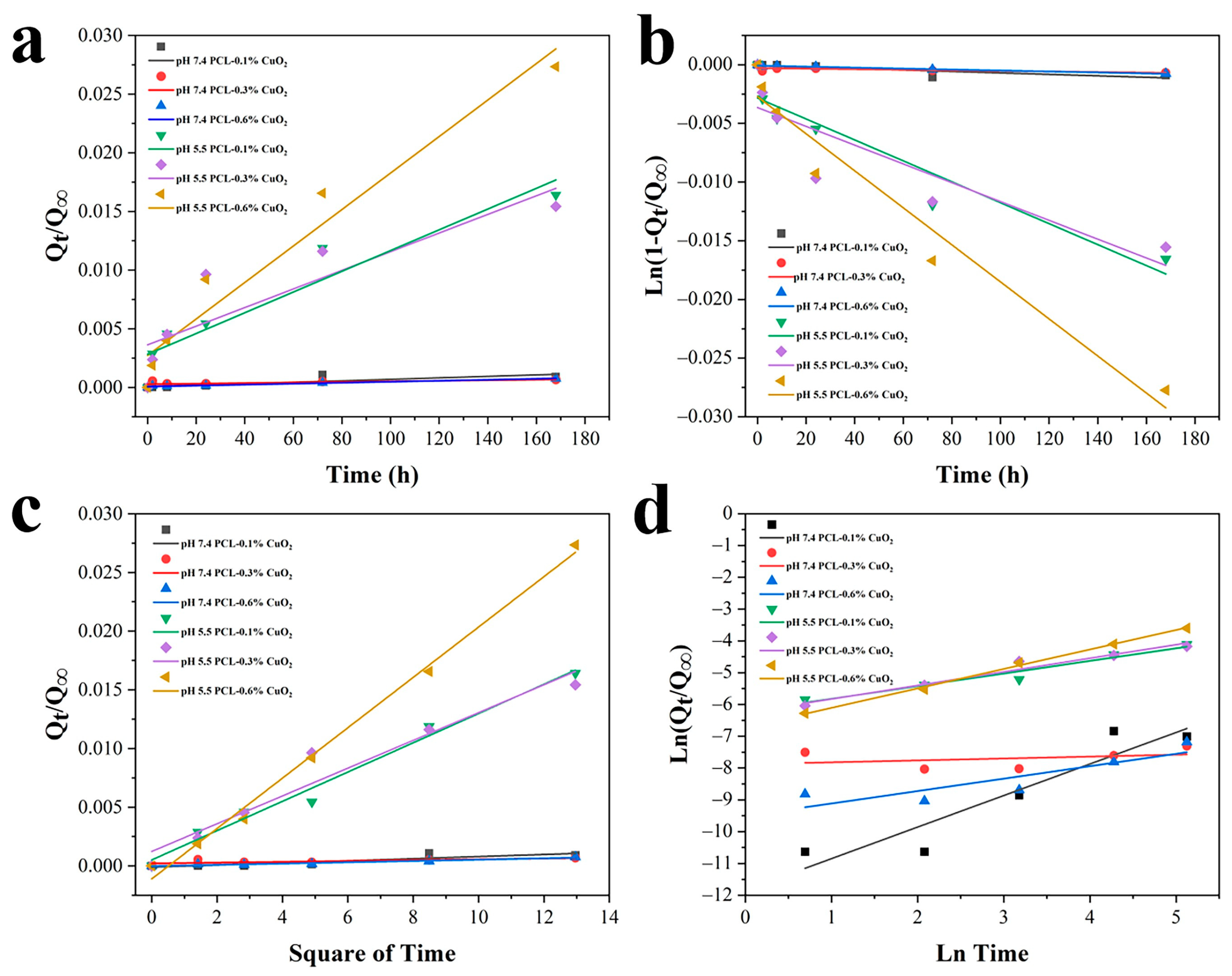

3.8. pH-Responsive Release of PCL-CuO2 Coatings

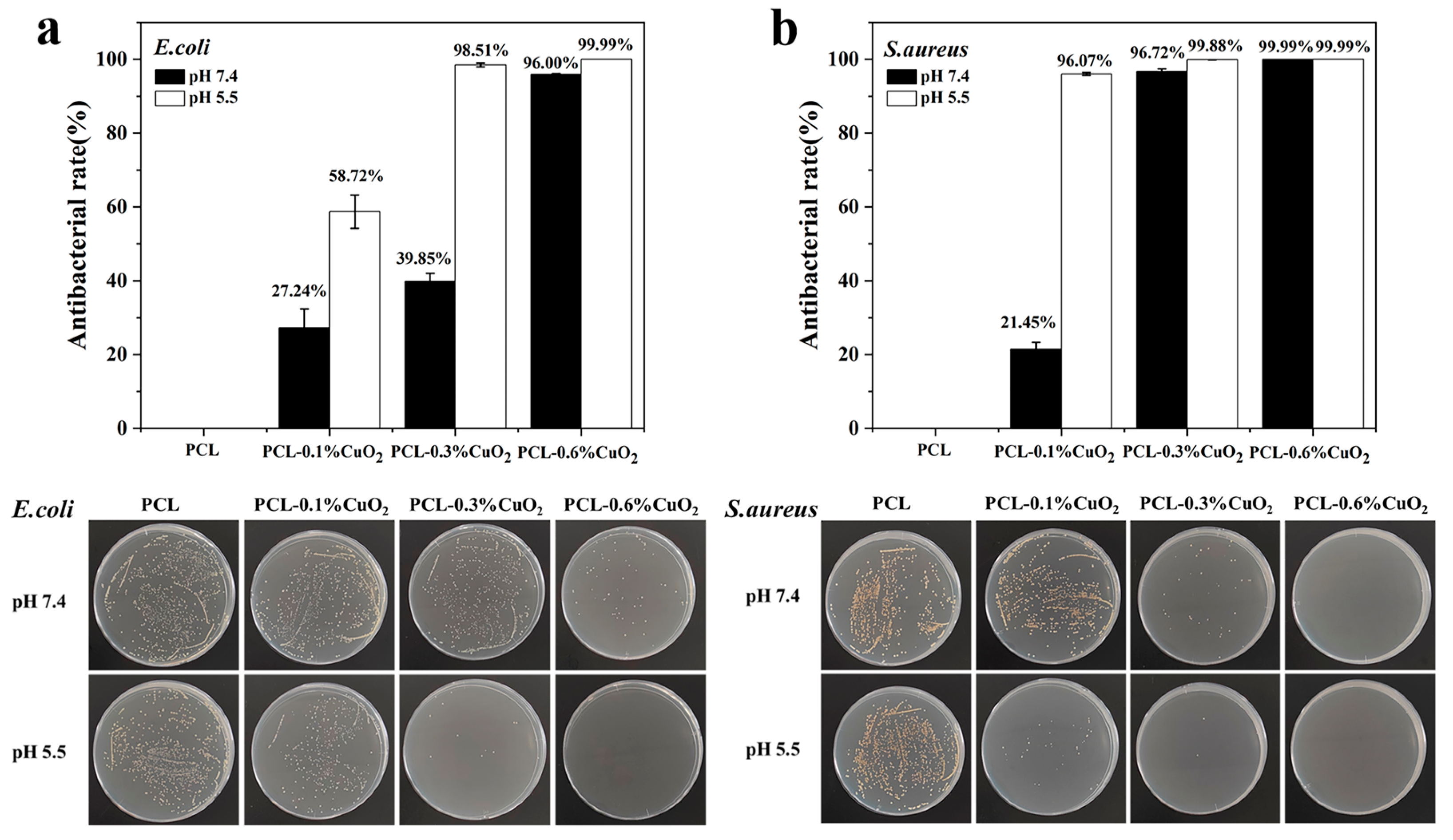

3.9. In Vitro Antibacterial Properties of PCL-CuO2 Coatings

4. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Khameneh, B.; Diab, R.; Ghazvini, K.; Fazly Bazzaz, B.S. Breakthroughs in bacterial resistance mechanisms and the potential ways to combat them. Microb. Pathog. 2016, 95, 32–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bakkeren, E.; Diard, M.; Hardt, W.D. Evolutionary causes and consequences of bacterial antibiotic persistence. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2020, 18, 479–490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rodrigues, M.; Kosaric, N.; Bonham, C.A.; Gurtner, G.C. Wound Healing: A Cellular Perspective. Physiol. Rev. 2019, 99, 665–706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Olsson, M.; Järbrink, K.; Divakar, U.; Bajpai, R.; Upton, Z.; Schmidtchen, A.; Car, J. The humanistic and economic burden of chronic wounds: A systematic review. Wound Repair Regen. 2019, 27, 114–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, H.; Wang, W.-S.; Tan, Y.; Zhang, D.-J.; Wu, J.-J.; Lei, X. Investigation and analysis of the characteristics and drug sensitivity of bacteria in skin ulcer infections. Chin. J. Traumatol. 2017, 20, 194–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nudelman, R.; Gavriely, S.; Bychenko, D.; Barzilay, M.; Gulakhmedova, T.; Gazit, E.; Richter, S. Bio-assisted synthesis of bimetallic nanoparticles featuring antibacterial and photothermal properties for the removal of biofilms. J. Nanobiotechnol. 2021, 19, 452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Balcucho, J.; Narvaez, D.M.; Castro-Mayorga, J.L. Antimicrobial and Biocompatible Polycaprolactone and Copper Oxide Nanoparticle Wound Dressings against Methicillin-Resistant Staphylococcus aureus. Nanomaterials 2020, 10, 1692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xie, X.; Wang, R.; Zhang, X.; Ren, Y.; Du, T.; Ni, Y.; Yan, H.; Zhang, L.; Sun, J.; Zhang, W.; et al. A photothermal and self-induced Fenton dual-modal antibacterial platform for synergistic enhanced bacterial elimination. Appl. Catal. B 2021, 295, 120315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, S.C.; Kim, N.H.; Yang, W.; Nah, J.W.; Jang, M.K.; Lee, D. Polymeric micellar nanoplatforms for Fenton reaction as a new class of antibacterial agents. J. Control. Release 2016, 221, 37–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, F.; Huang, K.; Chang, H.; Liang, Y.; Zhao, J.; Yang, S.; Liu, F. A polydopamine coated nanoscale FeS theranostic platform for the elimination of drug-resistant bacteria via photothermal-enhanced Fenton reaction. Acta Biomater. 2022, 150, 380–390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Guo, Z.; Li, F.; Xiao, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Bu, T.; Jia, P.; Zhe, T.; Wang, L. Multifunctional Magnetic Copper Ferrite Nanoparticles as Fenton-like Reaction and Near-Infrared Photothermal Agents for Synergetic Antibacterial Therapy. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2019, 11, 31649–31660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bergs, C.; Brück, L.; Rosencrantz, R.R.; Conrads, G.; Elling, L.; Pich, A. Biofunctionalized zinc peroxide (ZnO2) nanoparticles as active oxygen sources and antibacterial agents. RSC Adv. 2017, 7, 38998–39010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thi, P.L.; Lee, Y.; Tran, D.L.; Hoang Thi, T.T.; Park, K.M.; Park, K.D. Calcium peroxide-mediated in situ formation of multifunctional hydrogels with enhanced mesenchymal stem cell behaviors and antibacterial properties. J. Mater. Chem. B 2020, 8, 11033–11043. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lin, L.S.; Huang, T.; Song, J.; Ou, X.Y.; Wang, Z.; Deng, H.; Tian, R.; Liu, Y.; Wang, J.F.; Liu, Y.; et al. Synthesis of Copper Peroxide Nanodots for H2O2 Self-Supplying Chemodynamic Therapy. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2019, 141, 9937–9945. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gutsev, G.L.; Rao, B.K.; Jena, P. Systematic Study of Oxo, Peroxo, and Superoxo Isomers of 3d-Metal Dioxides and Their Anions. J. Phys. Chem. A 2000, 104, 11961–11971. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, R.; Jiang, G.; Gao, Q.; Wang, X.; Wang, Y.; Xu, X.; Yan, W.; Shen, H. Sprayed copper peroxide nanodots for accelerating wound healing in a multidrug-resistant bacteria infected diabetic ulcer. Nanoscale 2021, 13, 15937–15951. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, M.; Lan, X.; Han, X.; Shi, S.; Sun, H.; Kang, Y.; Dan, J.; Sun, J.; Zhang, W.; Wang, J. Acid-Induced Self-Catalyzing Platform Based on Dextran-Coated Copper Peroxide Nanoaggregates for Biofilm Treatment. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2021, 13, 29269–29280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, H.; Liu, M.; Yu, W.; Cao, Y.; Zhou, H.; Yin, J.; Liu, H.; Que, S.; Wang, J.; Huang, C.; et al. Copper Peroxide-Loaded Gelatin Sponges for Wound Dressings with Antimicrobial and Accelerating Healing Properties. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2021, 13, 26800–26807. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jones, E.M.; Cochrane, C.A.; Percival, S.L. The Effect of pH on the Extracellular Matrix and Biofilms. Adv. Wound Care 2015, 4, 431–439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zu, Y.; Wang, Y.; Yao, H.; Yan, L.; Yin, W.; Gu, Z. A Copper Peroxide Fenton Nanoagent-Hydrogel as an In Situ pH-Responsive Wound Dressing for Effectively Trapping and Eliminating Bacteria. ACS Appl. Bio Mater. 2022, 5, 1779–1793. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, S.B.; Rabbani, M.M.; Ji, B.C.; Han, D.W.; Lee, J.S.; Kim, J.W.; Yeum, J.H. Optimum Conditions for the Fabrication of Zein/Ag Composite Nanoparticles from Ethanol/H2O Co-Solvents Using Electrospinning. Nanomaterials 2016, 6, 230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, H.; Chen, X.; Lu, W.; Wang, J.; Xu, Y.; Guo, Y. Application of Electrospinning in Antibacterial Field. Nanomaterials 2021, 11, 1822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Varaprasad, K.; Mohan, Y.M.; Vimala, K.; Raju, K.M. Synthesis and Characterization of Hydrogel-Silver Nanoparticle-Curcumin Composites for Wound Dressing and Antibacterial Application. J. Appl. Polym. Sci. 2011, 121, 784–796. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ulubayram, K.; Cakar, A.N.; Korkusuz, P.; Ertan, C.; Hasirci, N. EGF containing gelatin-based wound dressings. Biomaterials 2001, 22, 1345–1356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bates, M.G.; Risselada, M.; Peña-Hernandez, D.C.; Hendrix, K.; Moore, G.E. Antibacterial activity of silver nanoparticles against Escherichia coli and methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus pseudintermedius is affected by incorporation into carriers for sustained release. Am. J. Vet. Res. 2024, 85, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koivuluoto, H. A Review of Thermally Sprayed Polymer Coatings. J. Therm. Spray Technol. 2022, 31, 1750–1764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, Y.; Zhou, D.; Cui, T.; Zhang, Y.; Ye, L.; Tian, Y.; Zhou, P.; Liu, Y.; Saitoh, H.; Zhang, B.; et al. A facile strategy for fine-tuning the drug release efficacy of poly-L-lactic acid-polycaprolactone coatings by liquid flame spray. Prog. Org. Coat. 2023, 183, 107807. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, J.; Yang, Y.; Detsch, R.; Boccaccini, A.R.; Virtanen, S. Iron surface functionalization system—Iron oxide nanostructured arrays with polycaprolactone coatings: Biodegradation, cytocompatibility, and drug release behavior. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2019, 492, 669–682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhuo, X.; Lei, T.; Miao, L.; Chu, W.; Li, X.; Luo, L.; Gou, J.; Zhang, Y.; Yin, T.; He, H.; et al. Disulfiram-loaded mixed nanoparticles with high drug-loading and plasma stability by reducing the core crystallinity for intravenous delivery. J. Colloid Interface Sci. 2018, 529, 34–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, Y.; Ye, L.; Zhou, P.; Feng, X.; Liu, Y.; Zhang, B.; Li, H. Facile suspension flame spray fabrication of polylactic acid-povidone-iodine coatings for antimicrobial applications. Mater. Lett. 2023, 341, 134293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ISO 22196:2011; Measurement of Antibacterial Activity on Plastics and Other Non-Porous Surfaces. ISO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2011.

- Pochapski, D.J.; Carvalho dos Santos, C.; Leite, G.W.; Pulcinelli, S.H.; Santilli, C.V. Zeta Potential and Colloidal Stability Predictions for Inorganic Nanoparticle Dispersions: Effects of Experimental Conditions and Electrokinetic Models on the Interpretation of Results. Langmuir 2021, 37, 13379–13389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, D.; Huo, J.; Zhang, Z.; An, Z.; Dong, H.; Wang, Y.; Duan, W.; Chen, L.; He, M.; Gao, S.; et al. Citric acid modified ultrasmall copper peroxide nanozyme for in situ remediation of environmental sulfonylurea herbicide contamination. J. Hazard. Mater. 2023, 443 Pt B, 130265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atif, M.; Chen, C.; Irfan, M.; Mumtaz, F.; He, K.; Zhang, M.; Chen, L.; Wang, Y. Poly(2-methyl-2-oxazoline) and poly(4-vinyl pyridine) based mixed brushes with switchable ability toward protein adsorption. Eur. Polym. J. 2019, 120, 109199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qi, Z.; Yu, H.; Chen, Y.; Zhu, M. Highly porous fibers prepared by electrospinning a ternary system of nonsolvent/solvent/poly(l-lactic acid). Mater. Lett. 2009, 63, 415–418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ebrahimifar, M.; Taherimehr, M. Evaluation of in-vitro drug release of polyvinylcyclohexane carbonate as a CO2-derived degradable polymer blended with PLA and PCL as drug carriers. J. Drug Delivery Sci. Technol. 2021, 63, 102491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yakub, G.; Ignatova, M.; Manolova, N.; Rashkov, I.; Toshkova, R.; Georgieva, A.; Markova, N. Chitosan/ferulic acid-coated poly(epsilon-caprolactone) electrospun materials with antioxidant, antibacterial and antitumor properties. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2018, 107 Pt A, 689–702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, P.; Luo, Z.; Che, Y.; Liu, Y.; Ke, F.; Cheng, G. Preparation and Study of Copper Peroxide and Copper Oxide for Electrochemical Reduction of CO2: Recommending a Comprehensive Research Inorganic Chemistry Experiment. Univ. Chem. 2022, 37, 2207146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pekdemir, M.E.; Öner, E.; Kök, M.; Qader, I.N. Thermal behavior and shape memory properties of PCL blends film with PVC and PMMA polymers. Iran. Polym. J. 2021, 30, 633–641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, D.; Xiong, D.; Zhu, N.; Wang, Y.; Hu, X.; Zhao, B.; Zhou, J.; Yin, D.; Zhang, Z. Copper Peroxide Nanodots Encapsulated in a Metal-Organic Framework for Self-Supplying Hydrogen Peroxide and Signal Amplification of the Dual-Mode Immunoassay. Anal. Chem. 2022, 94, 12981–12989. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jannesari, M.; Akhavan, O.; Madaah Hosseini, H.R.; Bakhshi, B. Graphene/CuO2 Nanoshuttles with Controllable Release of Oxygen Nanobubbles Promoting Interruption of Bacterial Respiration. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2020, 12, 35813–35825. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fowler, L.; Engqvist, H.; Ohman-Magi, C. Effect of Copper Ion Concentration on Bacteria and Cells. Materials 2019, 12, 3798. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tiwari, M.; Narayanan, K.; Thakar, M.B.; Jagani, H.V.; Venkata Rao, J. Biosynthesis and wound healing activity of copper nanoparticles. IET Nanobiotechnol. 2014, 8, 230–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Sample | 7.4 0.1% | 7.4 0.3% | 7.4 0.6% | 5.5 0.1% | 5.5 0.3% | 5.5 0.6% | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Zero-order model | K0 (×10−5) | 0.62 | 0.24 | 0.42 | 8.84 | 7.94 | 15.55 |

| R2 | 0.691 | 0.449 | 0.971 | 0.902 | 0.774 | 0.953 | |

| First-order model | K1 (×10−5) | −0.62 | −0.24 | −0.42 | −8.92 | −8.01 | −15.78 |

| R2 | 0.691 | 0.449 | 0.971 | 0.904 | 0.776 | 0.955 | |

| Higuchi model | KHI (×10−5) | 0.90 | 0.35 | 0.55 | 12.5 | 11.8 | 21.5 |

| R2 | 0.786 | 0.521 | 0.944 | 0.984 | 0.943 | 0.995 | |

| Korsmeyer–Peppas model | KKP (×10−5) | 0.08 | 3.71 | 0.75 | 20.29 | 18.36 | 12.31 |

| R2 | 0.879 | 0.108 | 0.764 | 0.957 | 0.964 | 0.997 | |

| n | 0.99 | 0.06 | 0.39 | 0.40 | 0.43 | 0.61 | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Cui, T.; Zhou, D.; Zhang, Y.; Kong, D.; Wang, Z.; Han, Z.; Song, M.; Aimaier, X.; Dan, Y.; Zhang, B.; et al. A pH-Responsive Polycaprolactone–Copper Peroxide Composite Coating Fabricated via Suspension Flame Spraying for Antimicrobial Applications. Materials 2024, 17, 2666. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma17112666

Cui T, Zhou D, Zhang Y, Kong D, Wang Z, Han Z, Song M, Aimaier X, Dan Y, Zhang B, et al. A pH-Responsive Polycaprolactone–Copper Peroxide Composite Coating Fabricated via Suspension Flame Spraying for Antimicrobial Applications. Materials. 2024; 17(11):2666. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma17112666

Chicago/Turabian StyleCui, Tingting, Daofeng Zhou, Yu Zhang, Decong Kong, Zhijuan Wang, Zhuoyue Han, Meiqi Song, Xierzhati Aimaier, Yanxin Dan, Botao Zhang, and et al. 2024. "A pH-Responsive Polycaprolactone–Copper Peroxide Composite Coating Fabricated via Suspension Flame Spraying for Antimicrobial Applications" Materials 17, no. 11: 2666. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma17112666

APA StyleCui, T., Zhou, D., Zhang, Y., Kong, D., Wang, Z., Han, Z., Song, M., Aimaier, X., Dan, Y., Zhang, B., & Li, H. (2024). A pH-Responsive Polycaprolactone–Copper Peroxide Composite Coating Fabricated via Suspension Flame Spraying for Antimicrobial Applications. Materials, 17(11), 2666. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma17112666