Hydrothermal Hot Isostatic Pressing (HHIP)—Experimental Proof of Concept

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Experimental

2.1. Materials

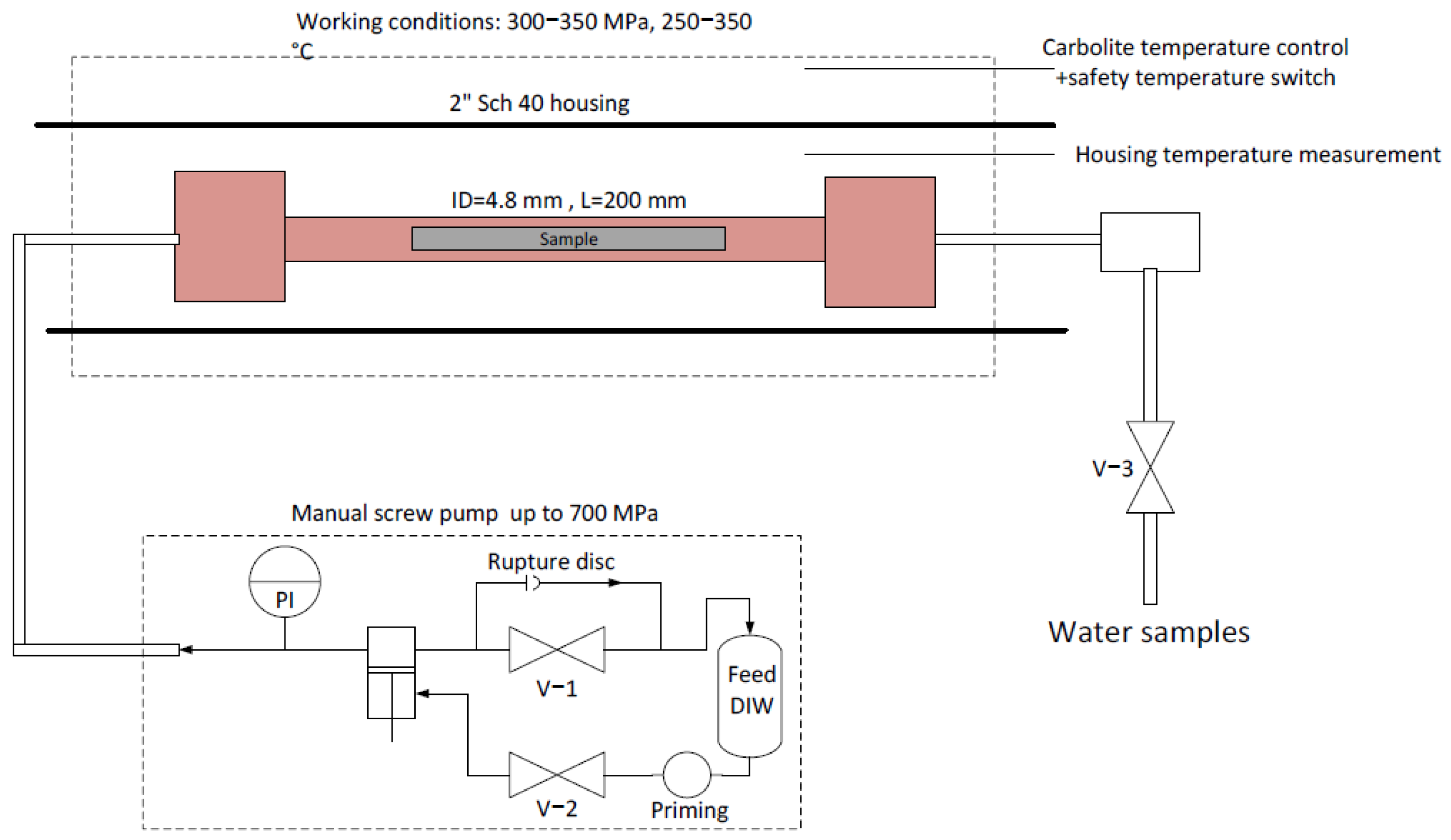

2.2. Experimental System

2.3. Hydrothermal Experiments

2.4. Analyses

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Corrosion

3.1.1. Experimental Conditions and the Resulting Species in the Water Samples

3.1.2. Inspection of the Surface Corrosion of the Al 6061/2024 Samples

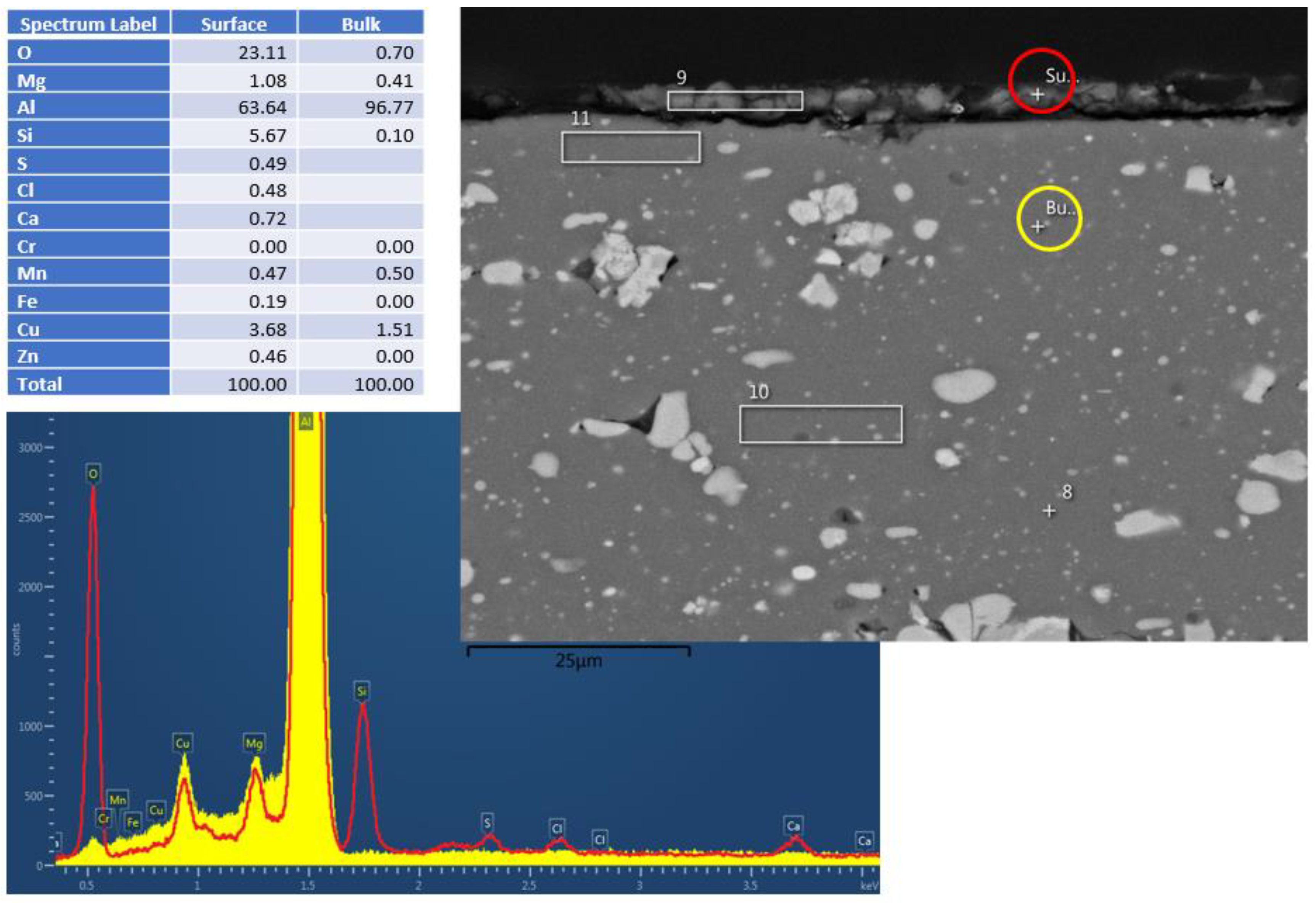

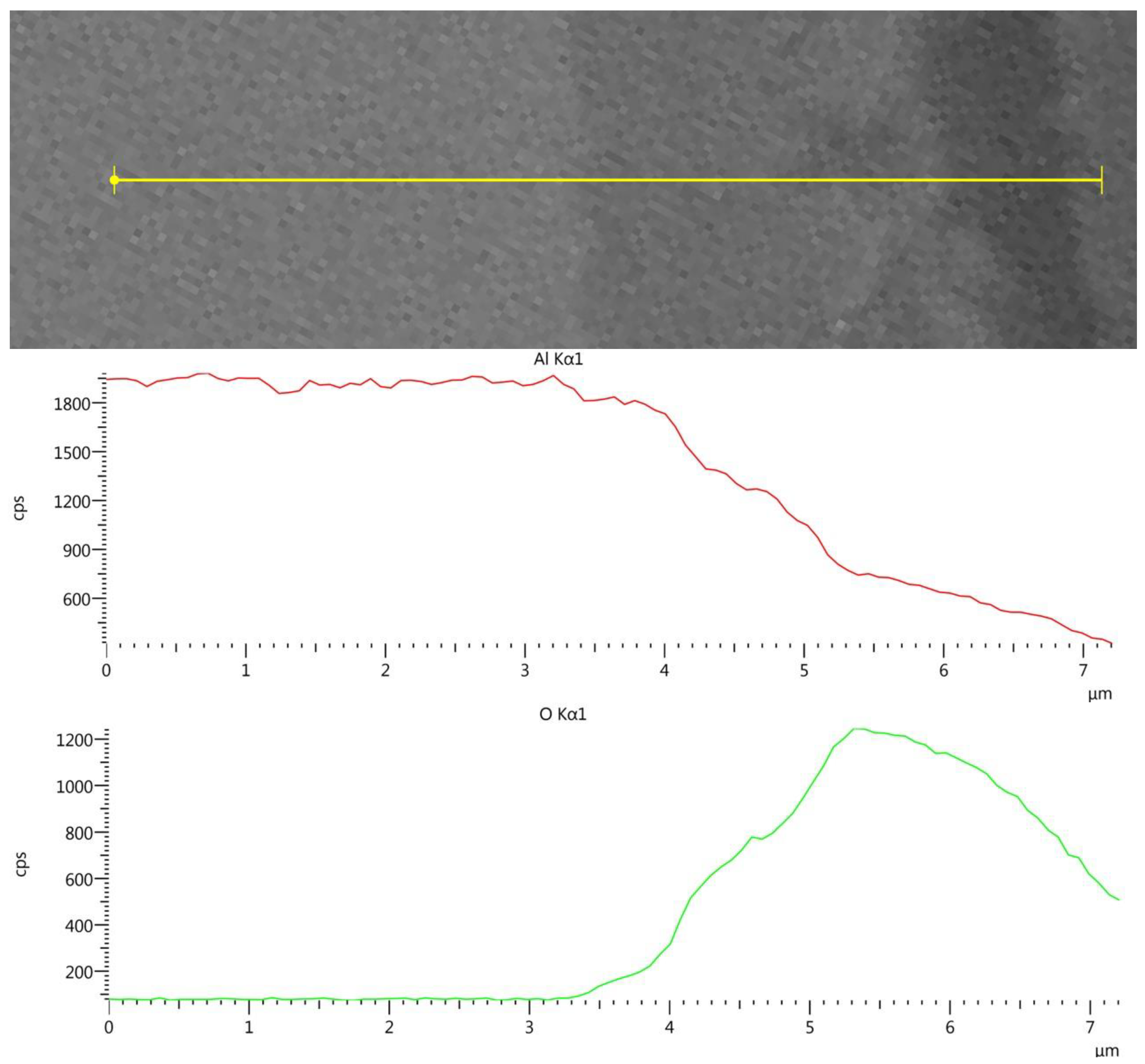

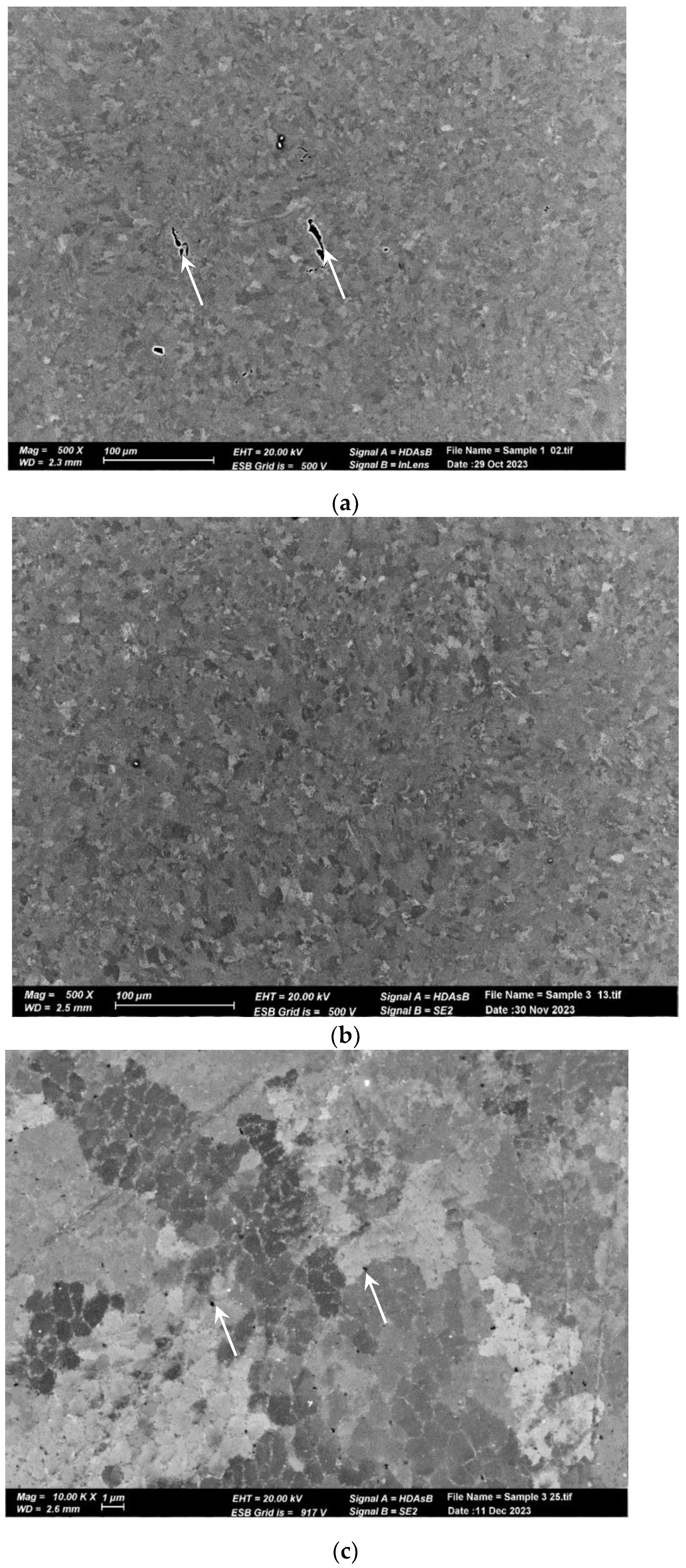

3.1.3. Inspection of the Surface Corrosion of AM AlSi10Mg Samples

3.2. Tomography Tests (MicroCT)

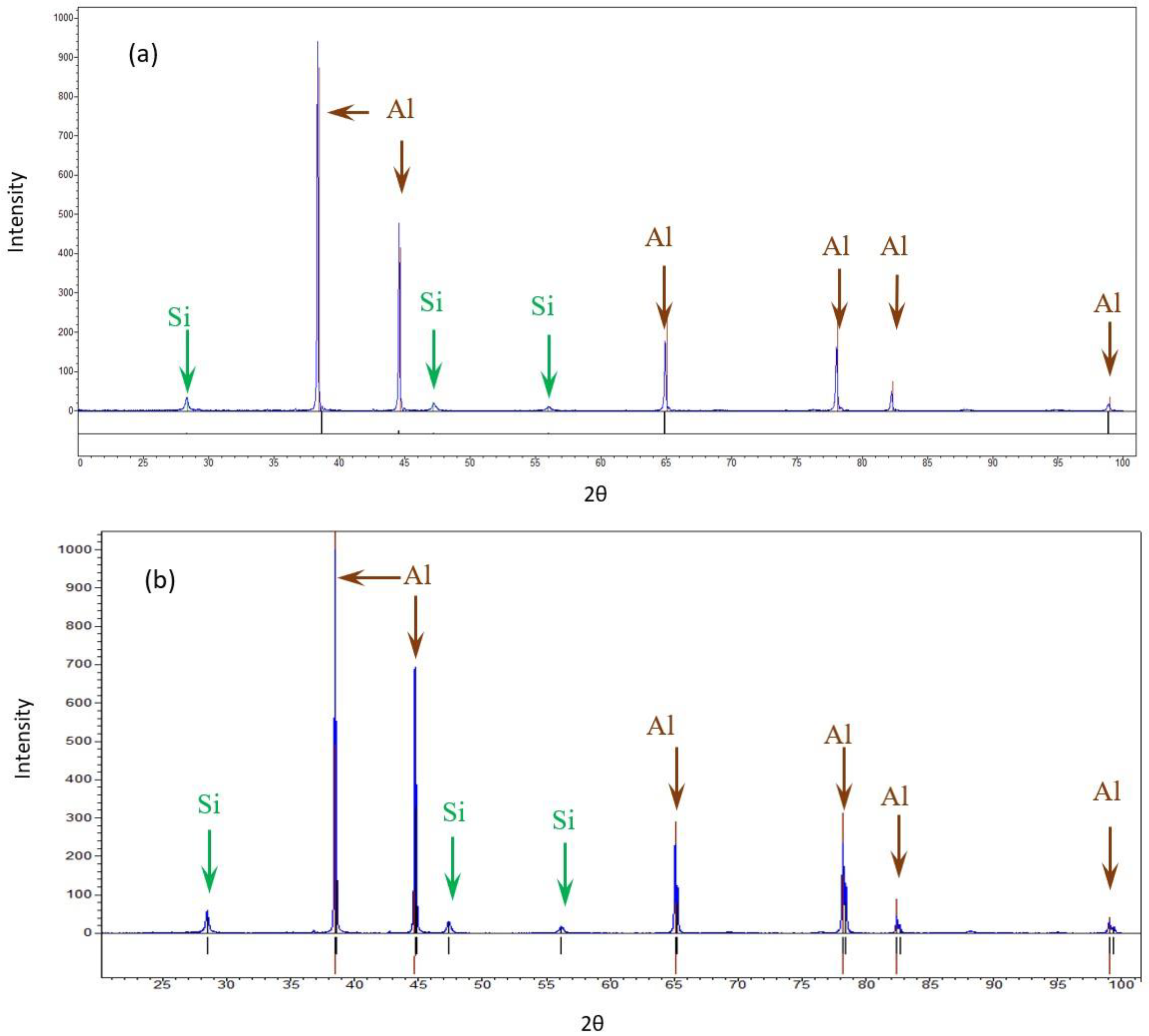

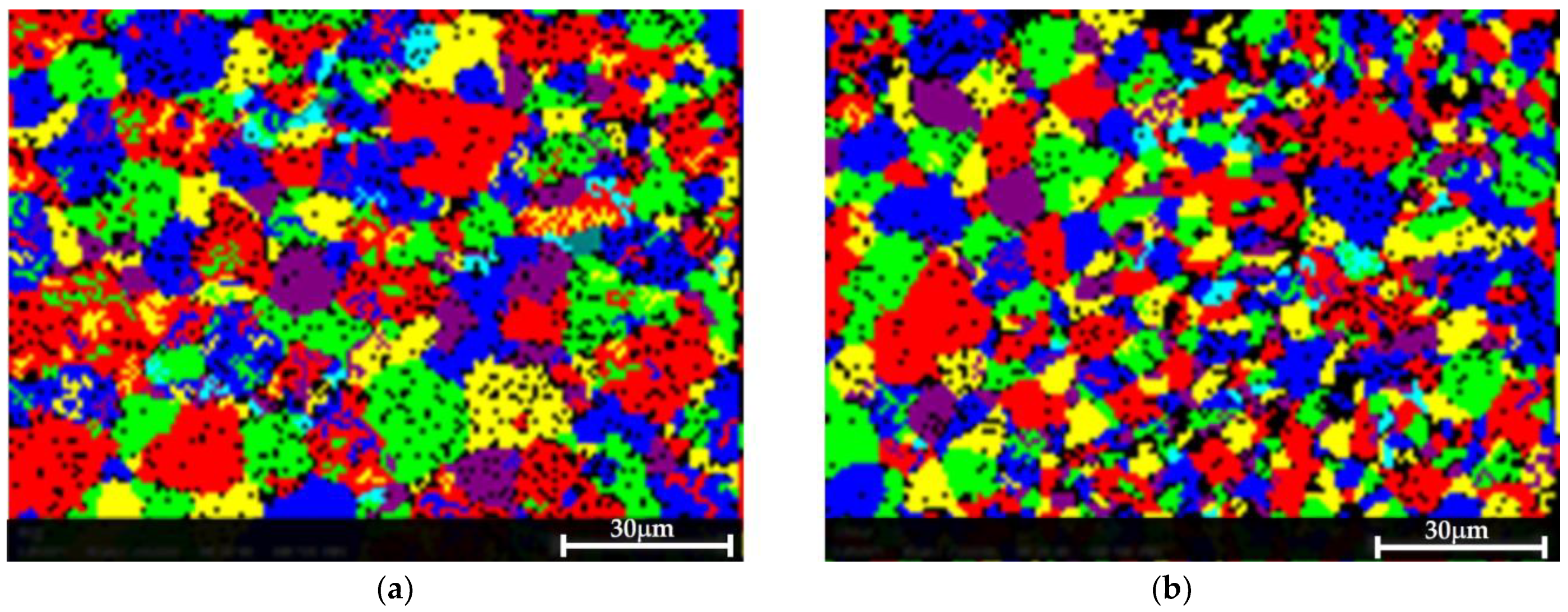

3.3. Grain Size and the Microstructure of the AM AlSi10Mg Samples

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Zakay, A.; Aghion, E. Effect of Post-heat Treatment on the Corrosion Behavior of AlSi10Mg Alloy Produced by Additive Manufacturing. JOM 2019, 71, 1150–1157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- du Plessis, A.; Macdonald, E. Hot isostatic pressing in metal additive manufacturing: X-ray tomography reveals details of pore closure. Addit. Manuf. 2020, 34, 101191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herzog, D.; Bartsch, K.; Bossen, B. Productivity optimization of laser powder bed fusion by hot isostatic pressing. Addit. Manuf. 2020, 36, 101494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Macías, J.G.S.; Zhao, L.; Tingaud, D.; Bacroix, B.; Pyka, G.; van der Rest, C.; Ryelandt, L.; Simar, A. Hot isostatic pressing of laser powder bed fusion AlSi10Mg: Parameter identification and mechanical properties. J. Mater. Sci. 2022, 57, 9726–9740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ertuğrul, O.; Öter, Z.Ç.; Yılmaz, M.S.; Şahin, E.; Coşkun, M.; Tarakçı, G.; Koç, E. Effect of HIP process and subsequent heat treatment on microstructure and mechanical properties of direct metal laser sintered AlSi10Mg alloy. Rapid Prototyp. J. 2020, 26, 1421–1434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atkinson, H.V.; Davies, S. Fundamental Aspects of Hot Isostatic Pressing: An Overview. Metall. Mater. Trans. A 2000, 31A, 2981–3000. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ASTM B998-17; Standard Guide for Hot Isostatic Pressing (HIP) of Aluminum Alloy Castings 1. ASTM International: West Conshohocken, PA, USA, 2017; pp. 1–4. [CrossRef]

- ASTM F3318-18; Standard for Additive Manufacturing-Finished Part Properties-Specification for AlSi10Mg with Powder Bed Fusion-Laser Beam 1. ASTM International: West Conshohocken, PA, USA, 2018; pp. 1–8. [CrossRef]

- Hirata, T.; Kimura, T.; Nakamoto, T. Effects of hot isostatic pressing and internal porosity on the performance of selective laser melted AlSi10Mg alloys. Mater. Sci. Eng. A 2020, 772, 138713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gheysen, J.; Tingaud, D.; Villanova, J.; Hocini, A.; Simar, A. Exceptional fatigue life and ductility of new liquid healing hot isostatic pressing especially tailored for additive manufactured aluminum alloys. Scr. Mater. 2023, 233, 115512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gussev, M.N.; Sridharan, N.; Thompson, Z.; Terrani, K.A.; Babu, S.S. Influence of hot isostatic pressing on the performance of aluminum alloy fabricated by ultrasonic additive manufacturing. Scr. Mater. 2018, 145, 33–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schneller, W.; Leitner, M.; Springer, S.; Grün, F.; Taschauer, M. Effect of hip treatment on microstructure and fatigue strength of selectively laser melted AlSi10Mg. J. Manuf. Mater. Process. 2019, 3, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uzan, N.E.; Shneck, R.; Yeheskel, O.; Frage, N. Fatigue of AlSi10Mg specimens fabricated by additive manufacturing selective laser melting (AM-SLM). Mater. Sci. Eng. A 2017, 704, 229–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahlfors, M. Cost Effective Hot Isostatic Pressing—A Cost Calculation Study for AM Parts. 2018. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/327561578 (accessed on 18 March 2024).

- Neikov, O.D.; Naboychenko, S.S.; Murashova, I.B.; Yefimov, N.A. Chapter 23—Production of Refractory Metal Powders. In Handbook of Non-Ferrous Metal Powders, 2nd ed.; Neikov, O.D., Naboychenko, S.S., Yefimov, N.A., Eds.; Elsevier: Oxford, UK, 2019; pp. 685–755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cuesta, I.I.; Martínez-Pañeda, E.; Díaz, A.; Alegre, J.M. Cold isostatic pressing to improve the mechanical performance of additively manufactured metallic components. Materials 2019, 12, 2495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hattori, T.; Yahata, A.; Mohri, J.; Yoshimura, I.; Somiya, S. Fabrication of phosphate-bonded mica ceramics by hot isostatic processing. J. Mater. Sci. Lett. 1984, 3, 57–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hattori, T.; Shigemori, A.; Mohri, J.I.; Yoshimura, M.; Somiya, S. Fabrication of Nonadditive Mica Ceramics by Hot Isostatic Processing. Commun. Am. Ceram. Soc. 1982, 65, C142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trowell, K.; Goroshin, S.; Frost, D.; Bergthorson, J. Hydrogen production rates of aluminum reacting with varying densities of supercritical water. RSC Adv. 2022, 12, 12335–12343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Trowell, K.; Blanchet, J.; Goroshin, S.; Frost, D.; Bergthorson, J. Hydrogen production via reaction of metals with supercritical water. Sustain. Energy Fuels 2022, 6, 3394–3401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trowell, K.A.; Goroshin, S.; Frost, D.L.; Bergthorson, J.M. The use of supercritical water for the catalyst-free oxidation of coarse aluminum for hydrogen production. Sustain. Energy Fuels 2020, 4, 5628–5635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cook, W.G.; Olive, R.P. Pourbaix diagrams for chromium, aluminum and titanium extended to high-subcritical and low-supercritical conditions. Corros. Sci. 2012, 58, 291–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parkhurst, D.L.; Appelo, C.A.J. Description of input and examples for PHREEQC version 3: A computer program for speciation, batch-reaction, one-dimensional transport, and inverse geochemical calculations. US Geol. Surv. Tech. Methods 2013, 6, 497. Available online: https://pubs.usgs.gov/tm/06/a43/ (accessed on 14 February 2024).

- United Aluminum. Aluminum Alloy 6061 Data Sheet. 2023. Available online: https://unitedaluminum.com/6061-aluminum-alloy/ (accessed on 13 May 2023).

- United Aluminum. Aluminum Alloy 2024 Data Sheet. 2023. Available online: https://unitedaluminum.com/2024-aluminum-alloy/ (accessed on 13 May 2023).

- EOS Metal Solutions. EOS Aluminum AlSi10Mg Material Data Sheet. 2022. Available online: https://www.eos.info/03_system-related-assets/material-related-contents/metal-materials-and-examples/metal-material-datasheet/aluminium/material_datasheet_eos_aluminium-alsi10mg_en_web.pdf (accessed on 13 May 2023).

- Uzan, N.E.; Shneck, R.; Yeheskel, O.; Frage, N. High-temperature mechanical properties of AlSi10Mg specimens fabricated by additive manufacturing using selective laser melting technologies (AM-SLM). Addit. Manuf. 2018, 24, 257–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fiocchi, J.; Tuissi, A.; Biffi, C.A. Heat treatment of aluminum alloys produced by laser powder bed fusion: A review. Mater. Des. 2021, 204, 109651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Al6061 [24] | Al2024 [25] | AlSi10Mg [26] | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Aluminum | Balance | Balance | Balance |

| Manganese | 0.15% | 0.30–0.90% | 0.45% |

| Silicon | 0.40–0.8% | 0.50% | 9.00–11.00% |

| Copper | 0.15–0.40% | 3.80–4.20% | 0.05% |

| Magnesium | 0.80–1.20% | 1.20–1.80% | 0.25–0.45% |

| Zirconium | 0.25% | 0.25% | |

| Zinc | 0.10% | ||

| Iron | 0.70% | 0.50% | 0.55% |

| Titanium | 0.15% | 0.15% | 0.15% |

| Chromium | 0.04–0.35% | ||

| Nickel | 0.05% | ||

| Lead | 0.05% | ||

| Tin | 0.05% | ||

| Others each | 0.05% | 0.05% | |

| Others total | 0.15% | 0.15% |

| Material | Temp | Pressure | Time | Initial Weight | Final Weight | Weight Change | Weight Loss | The Main Species in the Sample | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| # | [°C] | [MPa] | [h] | [g] | [g] | [%] | [mg/L] | ||

| 1 | Water blank | 300 | 300 | 8 | 0.013 µm (1) | [Fe] = 53.4, [Ti] = n.d. | |||

| 2 | Al6061 | 300 | 300 | 7 | 1.4428 | 1.4450 | +0.15 | (2) | [Al] < 0.1, [Fe] = 21.2, [Ti] = n.d. |

| 3 | Al6061 | 350 | 300 | 7 | 1.5138 | 1.5183 | +0.30 | 0.15% | [Al] = 0.242, [Fe] = 17.99, [Mg] = 5.1, [Ti] = n.d. |

| 4 | Al2024 | 300 | 300 | 7 | 0.3240 | 0.3249 | +0.28 | 0.62% | [Al] = 0.085, [Fe] = 12.5 [Mg] = 6.7, [Ti] = n.d. |

| 5 | Al2024 | 350 | 300 | 7 | 0.3952 | 0.3968 | +0.40 | 0.09% | [Al] < 0.1, [Fe] = 4.8 [Mg] = 1.2, [Ti] = n.d. |

| 6 | AlSi10Mg | 300 | 300 | 6 | 0.5517 | 0.5534 | +0.31 | 0.29% | [Al] = 0.200, [Fe] = 8.6, [Si] = 13.2, [Mg] = 1.4, [Ti] = n.d. |

| 7 | AlSi10Mg | 350 | 300 | 6 | 0.5863 | 0.5879 | +0.27 | 0.37% | [Al] = 0.289, [Fe] = 14.1, [Si] = 19.9, [Mg] = 1.9, [Ti] = n.d. |

| 8 | AlSi10Mg | 250 | 350 | 6 | 0.5310 | 0.5353 | +0.81 | 0.21% | [Al] = 0.278, [Fe] = 33.1, [Si] = 7.8, [Mg] = 1.0, [Ti] = n.d. |

| 9 | AlSi10Mg | 250 | 350 | 24 | 0.6771 | 0.6771 | none | 0.15% | [Al] = 0.129, [Fe] = 37.1, [Si] = 7.8, [Mg] = 0.9, [Ti] = n.d. |

| 10 | AlSi10Mg | 350 | 300 | 24 | 0.4887 | 0.4895 | +0.16 | 0.53% | [Al] = 0.045, [Fe] = 21.7, [Si] = 18.4, [Mg] = 2.3, [Ti] = n.d. |

| Sample | Reference Untreated | Experiment 8 | Experiment 9 | Experiment 10 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Experimental setup | none | 250 °C, 350 MPa, 6 h | 250 °C, 350 MPa, 24 h | 350 °C, 300 MPa, 24 h |

| Sample volume [mm3] | 88.7 | 66.82 | 77.12 | 68.99 |

| NT [Voxel/mm3] (1),(2) | 1807.0 | 1400.2 | 832 | 258.2 |

| Change in NT | −22.5% | −54% | −85.7% | |

| ST [mm2/mm3] × 10−3 | 37.9 | 23.9 | 12.2 | 3.5 |

| Change in ST (3) | −36.8% | −67.8% | −90.8% | |

| Max diameter [µm] | 170 | 107 | 112 | 97 |

| Experiment | Experiment Setup | HV0.1 Hardness |

|---|---|---|

| Reference Untreated | none | 134 ± 8 |

| Experiment 7 | 350 °C, 300 MPa, 6 h | 148 ± 25 |

| Experiment 8 | 250 °C, 350 MPa, 6 h | 148 ± 24 |

| Experiment 9 | 250 °C, 350 MPa, 24 h | 140 ± 26 |

| Experiment 10 | 350 °C, 300 MPa, 24 h | 152 ± 28 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Aviezer, Y.; Ariely, S.; Bamberger, M.; Zolotaryov, D.; Essel, S.; Lahav, O. Hydrothermal Hot Isostatic Pressing (HHIP)—Experimental Proof of Concept. Materials 2024, 17, 2716. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma17112716

Aviezer Y, Ariely S, Bamberger M, Zolotaryov D, Essel S, Lahav O. Hydrothermal Hot Isostatic Pressing (HHIP)—Experimental Proof of Concept. Materials. 2024; 17(11):2716. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma17112716

Chicago/Turabian StyleAviezer, Yaron, Shmuel Ariely, Menachem Bamberger, Denis Zolotaryov, Shai Essel, and Ori Lahav. 2024. "Hydrothermal Hot Isostatic Pressing (HHIP)—Experimental Proof of Concept" Materials 17, no. 11: 2716. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma17112716