Oligoester Identification in the Inner Coatings of Metallic Cans by High-Pressure Liquid Chromatography–Mass Spectrometry with Cone Voltage-Induced Fragmentation

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

3. Results and Discussion

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Abdollahi, M.; Khalili, B. Development of a novel hyperbranched unsaturated polyester resin: Synthesis, characterization, and potential applications in car body putty. Curr. Chem. Lett. 2024, 13, 325–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palacios-Mateo, C.; Van der Meer, Y.; Seide, G. Analysis of the polyester clothing value chain to identify key intervention points for sustainability. Environ. Sci. Eur. 2021, 33, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, A.E.; Reinhart, K.A. Polyester fiber: From its invention to its present position: The structure and properties of this versatile synthetic fiber have led to remarkable growth in many end uses. Science 1971, 173, 287–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Seyednejad, H.; Ghassemi, A.H.; Van Nostrum, C.F.; Vermonden, T.; Hennink, W.E. Functional aliphatic polyesters for biomedical and pharmaceutical applications. J. Control. Release 2011, 152, 168–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pellis, A.; Herrero Acero, E.; Gardossi, L.; Ferrario, V.; Guebitz, G.M. Renewable building blocks for sustainable polyesters: New biotechnological routes for greener plastics. Polym. Int. 2016, 65, 861–871. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alberto Lopes, J.; Tsochatzis, E.D. Poly (ethylene terephthalate), poly (butylene terephthalate), and polystyrene oligomers: Occurrence and analysis in food contact materials and food. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2023, 71, 2244–2258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kudłak, B.; Jatkowska, N.; Kubica, P.; Yotova, G.; Tsakovski, S. Influence of storage time and temperature on the toxicity, endocrine potential, and migration of epoxy resin precursors in extracts of food packaging materials. Molecules 2019, 24, 4396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lestido-Cardama, A.; Sendón, R.; Bustos, J.; Nieto, M.T.; Paseiro-Losada, P.; Rodríguez-Bernaldo de Quirós, A. Food and beverage can coatings: A review on chemical analysis, migration, and risk assessment. Compr. Rev. Food Sci. Food Saf. 2022, 21, 3558–3611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paseiro-Cerrato, R.; Noonan, G.O.; Begley, T.H. Evaluation of long-term migration testing from can coatings into food simulants: Polyester coatings. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2016, 64, 2377–2385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lestido-Cardama, A.; Vázquez-Loureiro, P.; Sendón, R.; Bustos, J.; Santillana, M.I.; Paseiro Losada, P.; Rodríguez Bernaldo de Quirós, A. Characterization of polyester coatings intended for food contact by different analytical techniques and migration testing by LC-MSn. Polymers 2022, 14, 487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schaefer, A.; Maß, S.; Simat, T.J.; Steinhart, H. Migration from can coatings: Part 1. A size exclusion chromatographic method for the simultaneous determination of overall migration and migrating substances below 1000 Da. Food Addit. Contam. 2004, 21, 287–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schaefer, A.; Ohm, V.A.; Simat, T.J. Migration from can coatings: Part 2. Identification and quantification of migrating cyclic oligoesters below 1000 Da. Food Addit. Contam. 2004, 21, 377–389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, N.; Kenion, G.; Bankmann, D.; Mezouari, S.; Hartman, T.G. Migration studies and chemical characterization of low molecular weight cyclic polyester oligomers from food packaging lamination adhesives. Packag. Technol. Sci. 2018, 31, 197–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Omer, E.; Cariou, R.; Remaud, G.; Guitton, Y.; Germon, H.; Hill, P.; Dervilly-Pinel, G.; Le Bizec, B. Elucidation of non-intentionally added substances migrating from polyester-polyurethane lacquers using automated LC-HRMS data processing. Anal. Bioanal. Chem. 2018, 410, 5391–5403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Omer, E.; Bichon, E.; Hutinet, S.; Royer, A.L.; Monteau, F.; Germon, H.; Hill, P.; Remaud, G.; Dervilly-Pinel, G.; Cariou, R.; et al. Toward the characterisation of non-intentionally added substances migrating from polyester-polyurethane lacquers by comprehensive gas chromatography-mass spectrometry technologies. J. Chromatogr. A 2019, 1601, 327–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bradley, E.L.; Driffield, M.; Guthrie, J.; Harmer, N.; Kenneth, P.; Oldring, T.; Castle, L. Analytical approaches to identify potential migrants in polyester-polyurethane can coatings. Food Addit. Contam. Part A 2009, 26, 1602–1610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eckardt, M.; Hetzel, L.; Brenz, F.; Simat, T.J. Release and migration of cyclic polyester oligomers from bisphenol A non-intent polyester-phenol-coatings into food simulants and infant food-a comprehensive study. Food Addit. Contam. Part A 2020, 37, 681–703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pietropaolo, E.; Albenga, R.; Gosetti, F.; Toson, V.; Koster, S.; Marin-Kuan, M.; Veyrand, J.; Patin, A.; Schilter, B.; Pistone, A.; et al. Synthesis, identification and quantification of oligomers from polyester coatings for metal packaging. J. Chromatogr. A 2018, 1578, 15–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reeves, B.J. An ultraviolet spectrophotometric method as an alternative test for determining overall migration from aromatic polyester packaging materials into fatty food oils. Food Addit. Contam. 1997, 14, 591–599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ubeda, S.; Aznar, M.; Rosenmai, A.K.; Vinggaard, A.M.; Nerín, C. Migration studies and toxicity evaluation of cyclic polyesters oligomers from food packaging adhesives. Food Chem. 2020, 311, 125918. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Colombo, G.; Corredig, M.; Ünalan, I.U.; Tsochatzis, E. Untargeted screening of NIAS and cyclic oligomers migrating from virgin and recycled polyethylene terephthalate (PET) food trays. Food Packag. Shelf Life 2024, 41, 101227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diamantidou, D.; Mastrogianni, O.; Tsochatzis, E.; Theodoridis, G.; Raikos, N.; Gika, H.; Kalogiannis, S. Liquid chromatography-mass spectrometry method for the determination of polyethylene terephthalate and polybutylene terephthalate cyclic oligomers in blood samples. Anal. Bioanal. Chem. 2022, 414, 1503–1512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayrapetyan, R.; Cariou, R.; Platel, A.; Santos, J.; Huot, L.; Monneraye, V.; Chagnon, M.-C.; Séverin, I. Identification of non-volatile non-intentionally added substances from polyester food contact coatings and genotoxicity assessment of polyester coating’s migrates. Food Chem. Toxicol. 2024, 185, 114484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoskins, J.N.; Grayson, S.M. Cyclic polyesters: Synthetic approaches and potential applications. Polymer Chem. 2011, 2, 289–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brenz, F.; Linke, S.; Simat, T.J. Linear and cyclic oligomers in PET, glycol-modified PET and TritanTM used for food contact materials. Food Addit. Contam. Part A 2021, 38, 160–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vázquez-Loureiro, P.; Lestido-Cardama, A.; Sendón, R.; Bustos, J.; Cariou, R.; Paseiro-Losada, P.; de Quirós, A.R.B. Investigation of migrants from can coatings: Occurrence in canned foodstuffs and exposure assessment. Food Packag. Shelf Life 2023, 40, 101183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Driffield, M.; Garcia-Lopez, M.; Christy, J.; Lloyd, A.S.; Tarbin, J.A.; Hough, P.; Bradley, E.L.; Kenneth, P.; Oldring, T. The determination of monomers and oligomers from polyester-based can coatings into foodstuffs over extended storage periods. Food Addit. Contam. Part A 2018, 35, 1200–1213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Paseiro-Cerrato, R.; MacMahon, S.; Ridge, C.D.; Noonan, G.O.; Begley, T.H. Identification of unknown compounds from polyester cans coatings that may potentially migrate into food or food simulants. J. Chromatogr. A 2016, 1444, 106–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cariou, R.; Riviére, M.; Hutinet, S.; Tebbaa, A.; Dubreuil, D.; Mathé-Allainmat, M.; Lebreton, J.; Le Bizec, B.; Tessier, A.; Dervilly, G. Thorough investigation of non-volatile substances extractible from inner coatings of metallic cans and their occurrence in the canned vegetables. J. Hazard. Mater. 2022, 435, 129026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bure, C.; Lange, C. Comparison of dissociation of ions in an electrospray source, or a collision cell in tandem mass spectrometry. Curr. Org. Chem. 2003, 7, 1613–1624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parcher, J.F.; Wang, M.; Chittiboyina, A.G.; Khan, I.A. In-source collision-induced dissociation (IS-CID): Applications, issues and structure elucidation with single-stage mass analyzers. Drug Test. Anal. 2018, 10, 28–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- An, N.; Zhu, Q.F.; Wang, Y.Z.; Xiong, C.F.; Hu, Y.N.; Feng, Y.Q. Integration of chemical derivatization and in-source fragmentation mass spectrometry for high-coverage profiling of submetabolomes. Anal. Chem. 2021, 93, 11321–11328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharp, J.; Do, D.; Davidson, J.T. Assessment of the similarity between in-source collision-induced dissociation (IS-CID) fragment ion spectra and tandem mass spectrometry (MS/MS) product ion spectra for seized drug identifications. Forensic Chem. 2022, 30, 100441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frański, R.; Gierczyk, B.; Popenda, Ł.; Kasperkowiak, M.; Pędzinski, T. Identification of a biliverdin geometric isomer by means of HPLC/ESI-MS and NMR spectroscopy. Differentiation of the isomers by using fragmentation “in-source”. Monatsh. Chem. 2018, 149, 995–1002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davidson, J.T.; Sasiene, Z.J.; Jackson, G.P. Comparison of in-source collision-induced dissociation and beam-type collision-induced dissociation of emerging synthetic drugs using a high-resolution quadrupole time-of-flight mass spectrometer. J. Mass Spectrom. 2021, 56, e4679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Yang, X.; Hoang, V.; Liu, Y.H. Characterization of protein disulfide linkages by MS in-source dissociation comparing to CID and ETD tandem MS. J. Am. Soc. Mass Spectrom. 2018, 30, 519–528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frańska, M. Cytidine-Ag+-purine base complexes as studied by electrospray ionization mass spectrometry. Eur. J. Mass Spectrom. 2010, 16, 587–594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, L.J.; Smith, R.W.; Toutoungi, D.E.; Reynolds, J.C.; Bristow, A.W.; Ray, A.; Sage, A.; Wilson, I.D.; Weston, D.J.; Boyle, B.; et al. Enhanced analyte detection using in-source fragmentation of field asymmetric waveform ion mobility spectrometry-selected ions in combination with time-of-flight mass spectrometry. Anal. Chem. 2012, 84, 4095–4103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stężycka, O.; Frańska, M.; Beszterda-Buszczak, M. Exploring glycosylated soy isoflavones affinities toward G-tetrads as studied by survival yield method. ChemPhysChem 2023, 24, e202300056. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Indelicato, S.; Bongiorno, D.; Indelicato, S.; Drahos, L.; Liveri, V.T.; Turiák, L.; Vékey, K.; Ceraulo, L. Degrees of freedom effect on fragmentation in tandem mass spectrometry of singly charged supramolecular aggregates of sodium sulfonates. J. Mass Spectrom. 2013, 48, 379–383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grzyb, K.; Frański, R.; Pędzinski, T. Sensitized photoreduction of selected benzophenones. Mass spectrometry studies of radical cross-coupling reactions. J. Photochem. Photobiol. B Biol. 2022, 234, 112536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kowcun, K.; Frańska, M.; Frański, R. Binuclear copper complexes with non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs as studied by electrospray ionization mass spectrometry. Cent. Eur. J. Chem. 2012, 10, 320–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Frański, R.; Zalas, M.; Gierczyk, B. Influence of carboxylic group or methyl ester group on the interactions of copper cation with aromatic system of naproxen, naphthalene acetic acids and their methyl esters. Int. J. Mass Spectrom. 2016, 394, 29–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

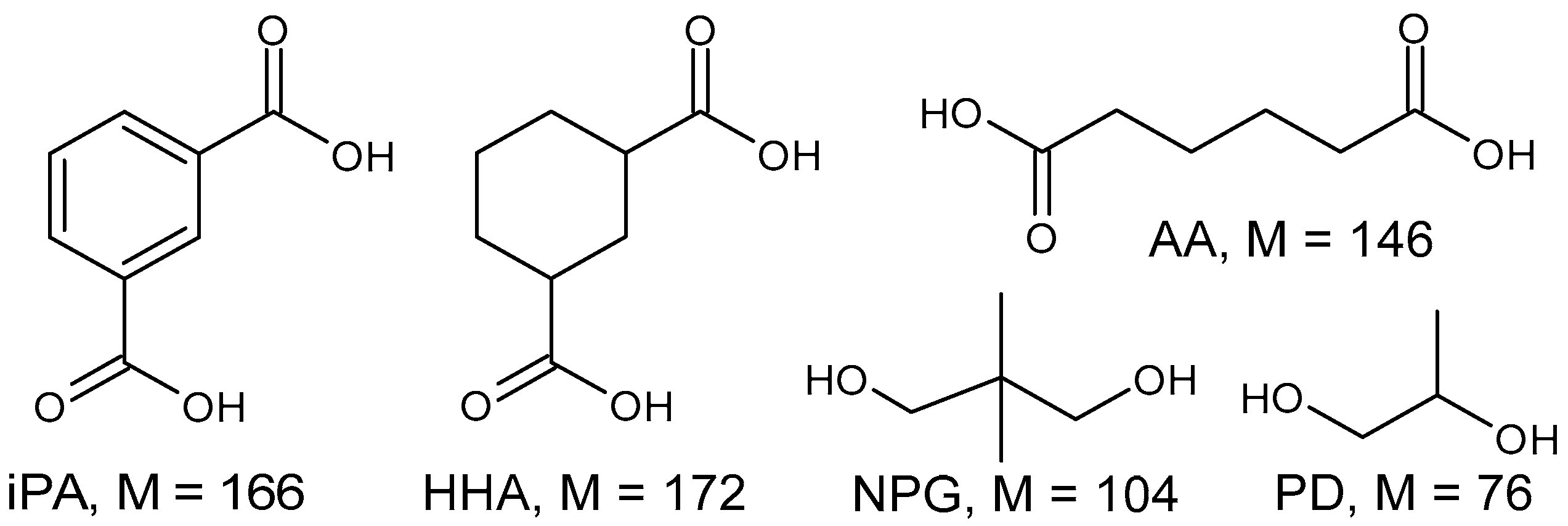

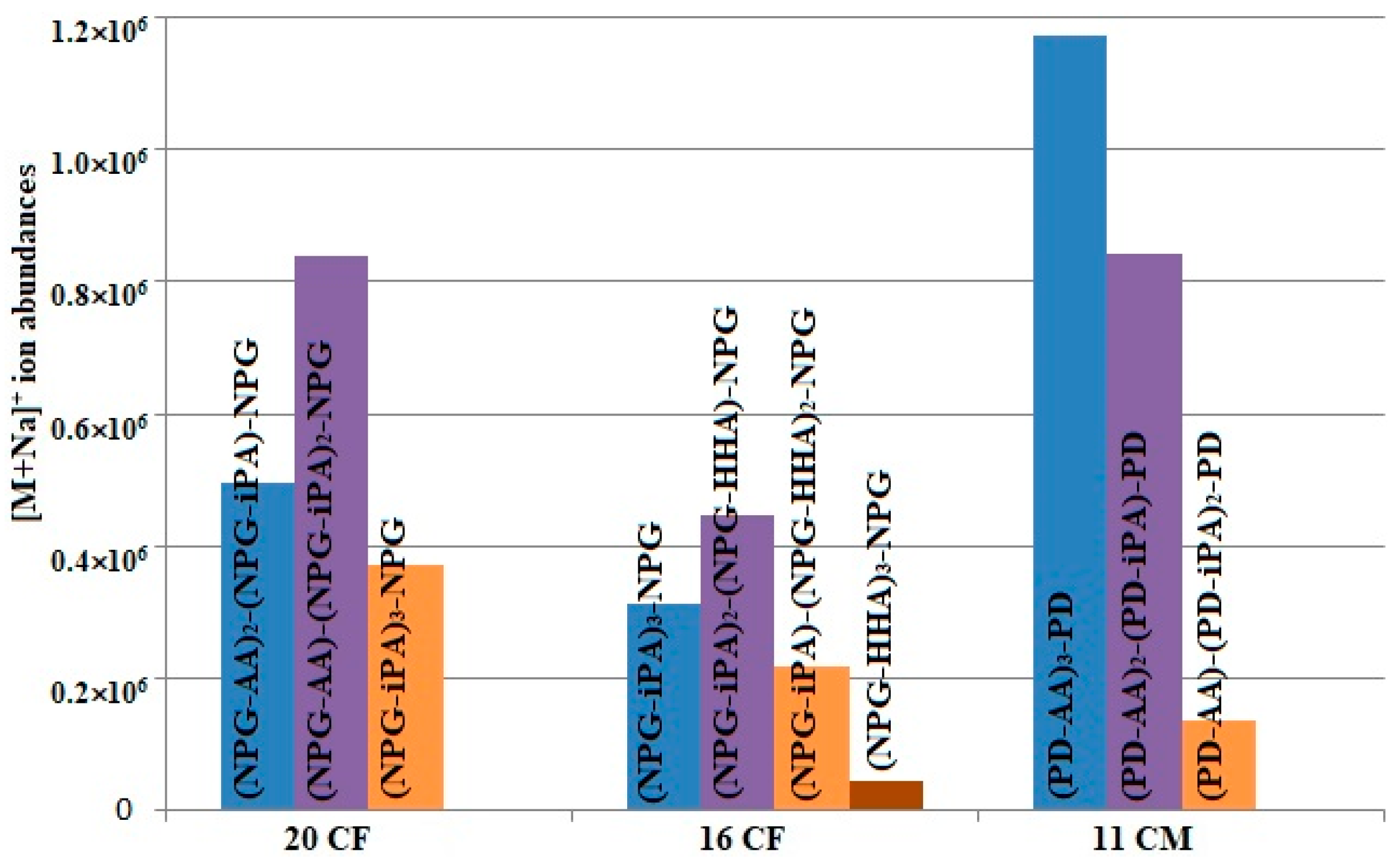

| Compound, M (Da); rt (min); Sample | Detected Ions |

|---|---|

| (NPG-iPA)2-NPG; 572; 20.8 16 CF, 17 CF; 18 CF, 19 CF; | [M+Na]+ m/z 595; [M+NH4]+ m/z 590; [M+H]+ m/z 573; [M+H-H2O]+ m/z 555; [M+H-104]+ m/z 469 |

| (NPG-iPA)-(NPG-HHA)-NPG; 578; 20.5 16 CF, 17 CF, 18 CF, 19 CF | [M+Na]+ m/z 601; [M+NH4]+ m/z 596; [M+H]+ m/z 579; [M+H-H2O]+ m/z 561; [M+H-104]+ m/z 475 |

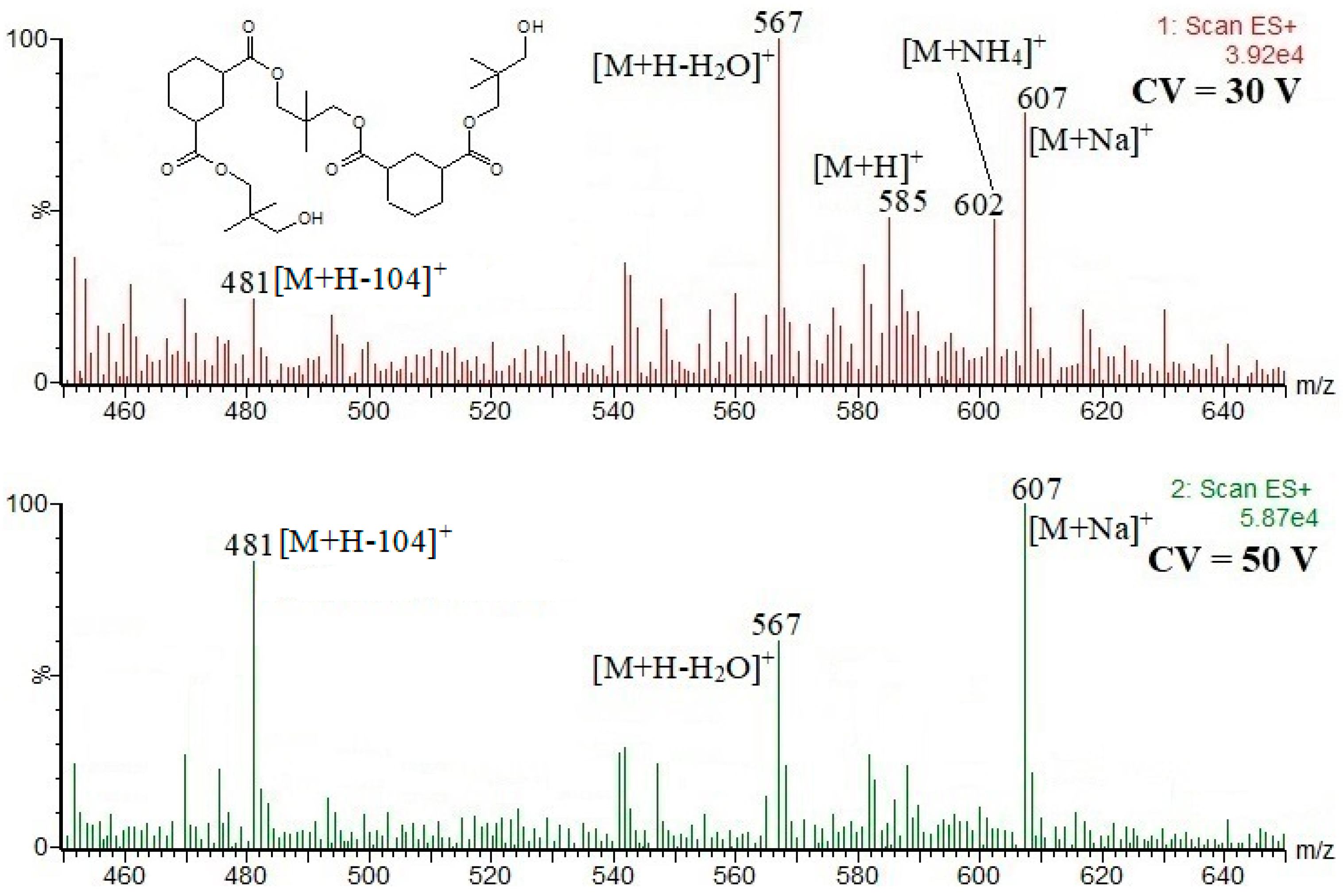

| (NPG-HHA)2-NPG; 584; 20.2 16 CF, 17 CF, 18 CF, 19 CF, | [M+Na]+ m/z 607; [M+NH4]+ m/z 602; [M+H]+ m/z 585; [M+H-H2O]+ m/z 567; [M+H-104]+ m/z 481 |

| (NPG-AA)2-(NPG-iPA)-NPG; 766; 22.6 20 CF | [M+Na]+ m/z 789; [M+NH4]+ m/z 784; [M+H]+ m/z 767; [M+H-H2O]+ m/z 749; [M+H-104]+ m/z 663 |

| (NPG-AA)-(NPG-iPA)2-NPG; 786; 23.6 20 CF | [M+Na]+ m/z 809; [M+NH4]+ m/z 804; [M+H]+ m/z 787; [M+H-H2O]+ m/z 769; [M+H-104]+ m/z 683 |

| (NPG-iPA)3-NPG; 806; 24.4 16 CF, 17 CF, 18 CF, 19 CF, 20 CF, | [M+Na]+ m/z 829; [M+NH4]+ m/z 824; [M+H]+ m/z 807; [M+H-H2O]+ m/z 789; [M+H-104]+ m/z 703 |

| (NPG-iPA)2-(NPG-HHA)-NPG; 812; 24.4, 16 CF, 17 CF, 18 CF, 19 CF, | [M+Na]+ m/z 835; [M+NH4]+ m/z 830; [M+H]+ m/z 813; [M+H-H2O]+ m/z 795; [M+H-104]+ m/z 709 |

| (NPG-iPA)-(NPG-HHA)2-NPG; 818; 24.2 16 CF, 17 CF, 18 CF, 19 CF, | [M+Na]+ m/z 841; [M+NH4]+ m/z 836; [M+H]+ m/z 819; [M+H-H2O]+ m/z 801; [M+H-104]+ m/z 715 |

| (NPG-HHA)3-NPG; 824; 24.0, 16 CF, 17 CF, 18 CF, 19 CF, | [M+Na]+ m/z 847; [M+NH4]+ m/z 842; [M+H]+ m/z 825; [M+H-H2O]+ m/z 807; [M+H-104]+ m/z 721 |

| (NPG-AA)3-(NPG-iPA)-NPG; 980; 24.83 20 CF | [M+Na]+ m/z 1003; [M+NH4]+ m/z 998; [M+H]+ m/z 981; [M+H-H2O]+ m/z 963; [M+H-104]+ m/z 877 |

| (NPG-AA)2-(NPG-iPA)2-NPG; 1000; 25.6 20 CF | [M+Na]+ m/z 1023; [M+NH4]+ m/z 1018; [M+H]+ m/z 1001; [M+H-H2O]+ m/z 983; [M+H-104]+ m/z 897 |

| (NPG-AA)-(NPG-iPA)3-NPG; 1020; 26.3; 20 CF | [M+Na]+ m/z 1043; [M+NH4]+ m/z 1038; [M+H]+ m/z 1021; [M+H-H2O]+ m/z 1003; [M+H-104]+ m/z 917 |

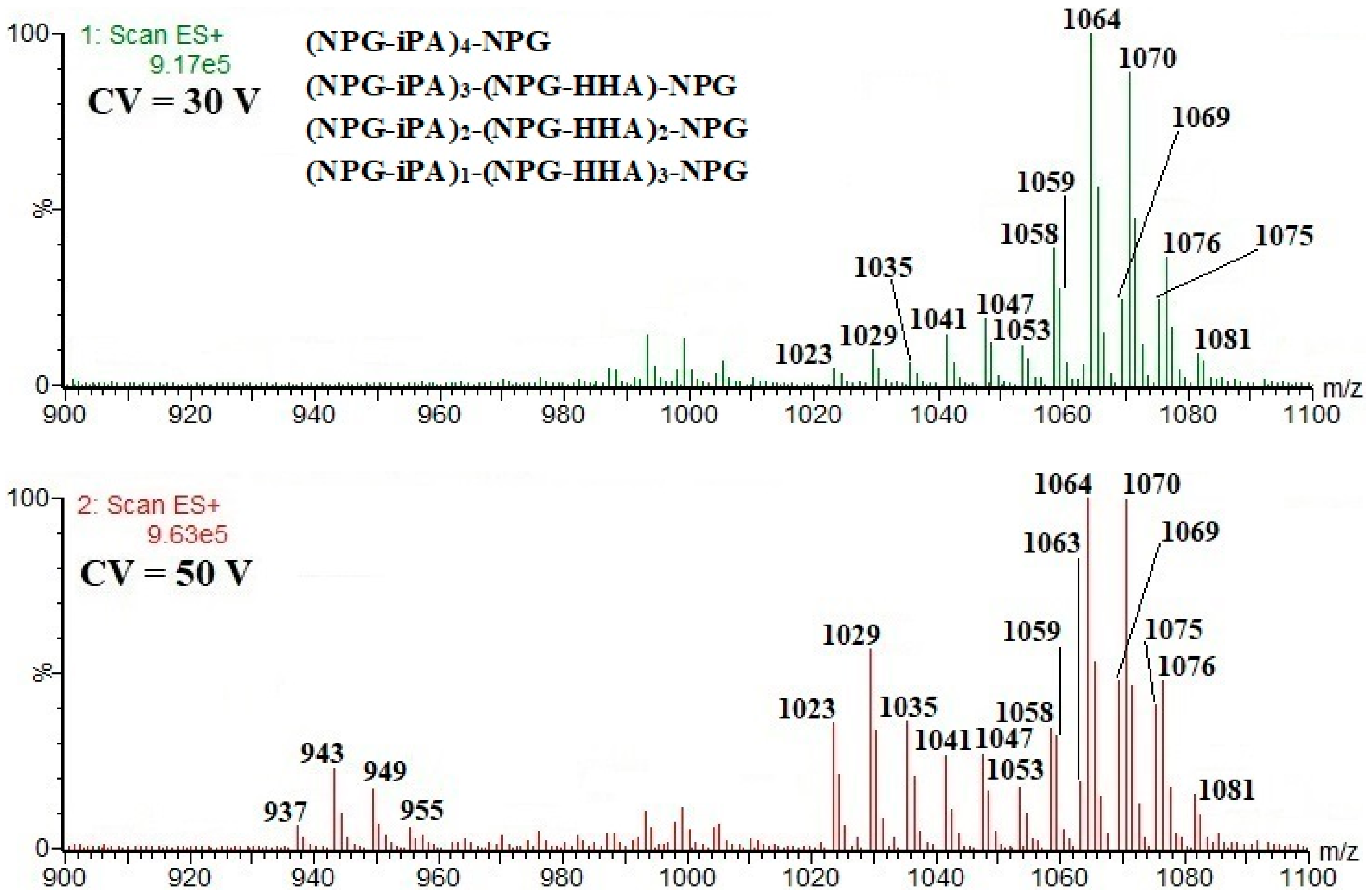

| (NPG-iPA)4-NPG; 1040; 26.9 17 CF, 19 CF, 20 CF, | [M+Na]+ m/z 1063; [M+NH4]+ m/z 1058; [M+H]+ m/z 1041; [M+H-H2O]+ m/z 1023; [M+H-104]+ m/z 937 |

| (NPG-iPA)3-(NPG-HHA)-NPG; 1046; 27.0; 17 CF, 19 CF | [M+Na]+ m/z 1069; [M+NH4]+ m/z 1064; [M+H]+ m/z 1047; [M+H-H2O]+ m/z 1029; [M+H-104]+ m/z 943 |

| (NPG-iPA)2-(NPG-HHA)2-NPG; 1052; 26.9 17 CF, 19 CF | [M+Na]+ m/z 1075; [M+NH4]+ m/z 1070; [M+H]+ m/z 1053; [M+H-H2O]+ m/z 1035; [M+H-104]+ m/z 949 |

| (NPG-iPA)-(NPG-HHA)3-NPG; 1058; 26.8 17 CF, 19 CF | [M+Na]+ m/z 1081; [M+NH4]+ m/z 1076; [M+H]+ m/z 1059; [M+H-H2O]+ m/z 1041; [M+H-104]+ m/z 955 |

| Compound, M (Da); rt (min) | Detected Ions |

|---|---|

| (PD-AA)3-PD; 634; 15.6 | [M+Na]+ m/z 657; [M+NH4]+ m/z 652; [M+H-H2O]+ m/z 617; [M+H-76]+ m/z 559 |

| (PD-AA)2-(PD-iPA)-PD; 654; 16.8 | [M+Na]+ m/z 677; [M+NH4]+ m/z 672; [M+H-H2O]+ m/z 637; [M+H-76]+ m/z 579 |

| (PD-AA)-(PD-iPA)2-PD; 674; 17.3 | [M+Na]+ m/z 697; [M+NH4]+ m/z 692; [M+H-H2O]+ m/z 657; [M+H-76]+ m/z 599 |

| (PD-AA)4-PD; 820; 18.2 | [M+Na]+ m/z 843; [M+NH4]+ m/z 838; [M+H-H2O]+ m/z 803; [M+H-76]+ m/z 745 |

| (PD-AA)3-(PD-iPA)-PD; 840; 18.6 | [M+Na]+ m/z 863; [M+NH4]+ m/z 858; [M+H-H2O]+ m/z 823; [M+H-76]+ m/z 765 |

| (PD-AA)2-(PD-iPA)2-PD; 860; 19.1 | [M+Na]+ m/z 883; [M+NH4]+ m/z 878; [M+H-H2O]+ m/z 843; [M+H-76]+ m/z 785 |

| (PD-AA)5-PD; 1006; 19.9 | [M+Na]+ m/z 1029; [M+NH4]+ m/z 1024; [M+H-H2O]+ m/z 989; [M+H-76]+ m/z 931 |

| (PD-AA)4-(PD-iPA)-PD; 1026; 20.1 | [M+Na]+ m/z 1049; [M+NH4]+ m/z 1044; [M+H-H2O]+ m/z 1009; [M+H-76]+ m/z 951 |

| (PD-AA)3-(PD-iPA)2-PD; 1046; 20.4 | [M+Na]+ m/z 1069; [M+NH4]+ m/z 1064; [M+H-H2O]+ m/z 1029; [M+H-76]+ m/z 971 |

| Compound, M (Da); rt (min); Sample | Detected Ions |

|---|---|

| (NPG-AA)3; 642; 23.6 20 CF | [M+Na]+ m/z 665; [M+NH4]+ m/z 660; [M+H]+ m/z 643; [M+H-86]+ m/z 557; [M+H-214]+ m/z 429 |

| (NPG-AA)2-(NPG-iPA); 662; 24.8 20 CF | [M+Na]+ m/z 685; [M+NH4]+ m/z 680; [M+H]+ m/z 663; [M+H-86]+ m/z 577; [M+H-214]+ m/z 449 |

| (NPG-AA)-(NPG-iPA)2; 682; 25.8 20 CF | [M+Na]+ m/z 705; [M+NH4]+ m/z 700; [M+H]+ m/z 683; [M+H-86]+ m/z 597; [M+H-214]+ m/z 469 |

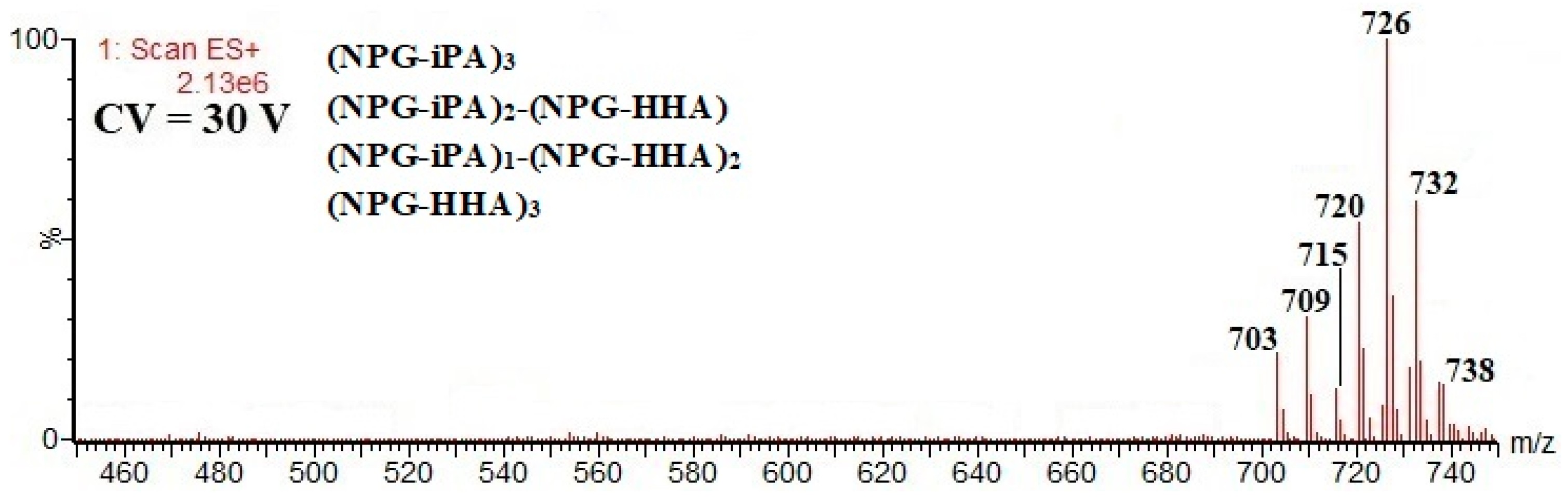

| (NPG-iPA)3; 702; 26.2 16 CF, 17 CF, 18 CF, 19 CF, 20 CF | [M+Na]+ m/z 725; [M+NH4]+ m/z 720; [M+H]+ m/z 703; [M+H-86]+ m/z 617; [M+H-234]+ m/z 469 |

| (NPG-iPA)2-(NPG-HHA); 708; 26.1 16 CF, 17 CF, 18 CF, 19 CF | [M+Na]+ m/z 731; [M+NH4]+ m/z 726; [M+H]+ m/z 709; [M+H-86]+ m/z 623; [M+H-234]+ m/z 475 |

| (NPG-iPA)-(NPG-HHA)2; 714; 26.2 16 CF, 17 CF, 18 CF, 19 CF | [M+Na]+ m/z 737; [M+NH4]+ m/z 732; [M+H]+ m/z 715; [M+H-234]+ m/z 481 |

| (NPG-HHA)3; 720; 26.1 16 CF, 17 CF, 18 CF, 19 CF | [M+Na]+ m/z 743; [M+NH4]+ m/z 738; [M+H]+ m/z 721 |

| (NPG-AA)3-(NPG-iPA); 876; 26.8 20 CF | [M+Na]+ m/z 899; [M+NH4]+ m/z 894; [M+H]+ m/z 877; [M+H-86]+ m/z 791; [M+H-214]+ m/z 663 |

| (NPG-AA)2-(NPG-iPA)2; 896; 27.4 20 CF | [M+Na]+ m/z 919; [M+NH4]+ m/z 914; [M+H]+ m/z 897; [M+H-86]+ m/z 811; [M+H-214]+ m/z 683 [M+H-234]+ m/z 663 |

| (NPG-AA)-(NPG-iPA)3; 916; 28.0 20 CF | [M+Na]+ m/z 939; [M+NH4]+ m/z 934; [M+H]+ m/z 917; [M+H-86]+ m/z 831; [M+H-234]+ m/z 683 |

| (NPG-iPA)4; 936; 28.5 16 CF, 17 CF, 18 CF, 19 CF, 20 CF | [M+Na]+ m/z 959; [M+NH4]+ m/z 954; [M+H]+ m/z 937; [M+H-86]+ m/z 851; [M+H-234]+ m/z 703 |

| (NPG-iPA)3-(NPG-HHA); 942; 28.6 16 CF, 17 CF, 18 CF, 19 CF | [M+Na]+ m/z 965; [M+NH4]+ m/z 960; [M+H]+ m/z 943; [M+H-86]+ m/z 857; [M+H-234]+ m/z 709 |

| (NPG-iPA)2-(NPG-HHA)2; 948; 28.7 16 CF, 17 CF, 18 CF, 19 CF | [M+Na]+ m/z 971; [M+NH4]+ m/z 966; [M+H]+ m/z 949; |

| (NPG-iPA)-(NPG-HHA)3; 954; 28.9 16 CF, 17 CF, 18 CF, 19 CF | [M+Na]+ m/z 977; [M+NH4]+ m/z 972; [M+H]+ m/z 955; |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Beszterda-Buszczak, M.; Frański, R. Oligoester Identification in the Inner Coatings of Metallic Cans by High-Pressure Liquid Chromatography–Mass Spectrometry with Cone Voltage-Induced Fragmentation. Materials 2024, 17, 2771. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma17112771

Beszterda-Buszczak M, Frański R. Oligoester Identification in the Inner Coatings of Metallic Cans by High-Pressure Liquid Chromatography–Mass Spectrometry with Cone Voltage-Induced Fragmentation. Materials. 2024; 17(11):2771. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma17112771

Chicago/Turabian StyleBeszterda-Buszczak, Monika, and Rafał Frański. 2024. "Oligoester Identification in the Inner Coatings of Metallic Cans by High-Pressure Liquid Chromatography–Mass Spectrometry with Cone Voltage-Induced Fragmentation" Materials 17, no. 11: 2771. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma17112771

APA StyleBeszterda-Buszczak, M., & Frański, R. (2024). Oligoester Identification in the Inner Coatings of Metallic Cans by High-Pressure Liquid Chromatography–Mass Spectrometry with Cone Voltage-Induced Fragmentation. Materials, 17(11), 2771. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma17112771