Abstract

Combination therapy emerges as a fundamental scheme in cancer. Many targeted therapeutic agents are developed to be used with chemotherapy or radiation therapy to enhance drug efficacy and reduce toxicity effects. ABT-263, known as navitoclax, mimics the BH3-only proteins of the BCL-2 family and has a high affinity towards pro-survival BCL-2 family proteins (i.e., BCL-XL, BCL-2, BCL-W) to induce cell apoptosis effectively. A single navitoclax action potently ameliorates several tumor progressions, including blood and bone marrow cancer, as well as small cell lung carcinoma. Not only that, but navitoclax alone also therapeutically affects fibrotic disease. Nevertheless, outcomes from the clinical trial of a single navitoclax agent in patients with advanced and relapsed small cell lung cancer demonstrated a limited anti-cancer activity. This brings accumulating evidence of navitoclax to be used concomitantly with other chemotherapeutic agents in several solid and non-solid tumors that are therapeutically benefiting from navitoclax treatment in preclinical studies. Initially, we justify the anti-cancer role of navitoclax in combination therapy. Then, we evaluate the current evidence of navitoclax in combination with the chemotherapeutic agents comprehensively to indicate the primary regulator of this combination strategy in order to produce a therapeutic effect.

1. Introduction

An early review has described six mechanistic strategies of cancer cells to dictate malignant growth [1,2]. Later, a recent study has re-evaluated and reported more updated cancer hallmarks consisting of seven factors; (i) selective proliferative advantage; (ii) altered stress response; (iii) vessel development; (iv) invasion and metastasis; (v) metabolic reconfiguration; (vi) immune regulation; and (vii) an abetting micro-environment [3]. The first hallmark was explained by the collaboration between oncogenes’ activation with tumor suppressor genes’ inactivation at the cellular level. Next, the second factor was modified from the Hanahan & Weinberg study, in which they quoted as evading programmed cell death and unlimited proliferative capability. However, cancer cells are going through cellular senescence and apoptotic events as well [4]. Such events would increase the selective pressure on cancer cells, and those cells that can adapt better to the situation would survive [5]. In addition, the apoptosis of (pre)-cancerous cells would allow repopulation by more aggressive tumor cells, potentially driving tumor evolution [6]. Emerging studies reported both angiogenesis and vascularization discretely modulate the initiation of microtumors [3,7]. Angiogenesis influences exponential tumor growth, whilst vascularization is vital for cell survival and spreading [8]. Malignant tumor metastasis involves the invasion of adjacent tissues, and this event is often responsible for more than 90% of cancer-related deaths [9]. The discovery of metabolic alterations in cancer cells provides novel insight into the causes and consequences of this factor towards the initiation and tumor progression. Several metabolic alterations are associated with cancer, including the elevation of nitrogen demand, deregulated uptake of nutrients such as glucose and amino acids, and changes in metabolite-driven gene regulation [10,11]. Besides, several pre-existing pathological conditions, such as chronic inflammatory, hyperglycemic, hypoxia, and glycoxidative stress, in conjunction with the activation of the receptor for advanced glycation end products (RAGE)-ligand would synergistically promote tumor development and progression, mostly in diabetic and obese patients [12]. Immune regulation in cancer is postulated to play a prominent role during the initiation and progression of tumorigenesis. Lastly, an abetting and dynamic microenvironment is produced through a continuous paracrine interaction between cancerous and stromal cells at all stages of carcinogenesis, resulting in tumor progression and survival of the cancer cells [3].

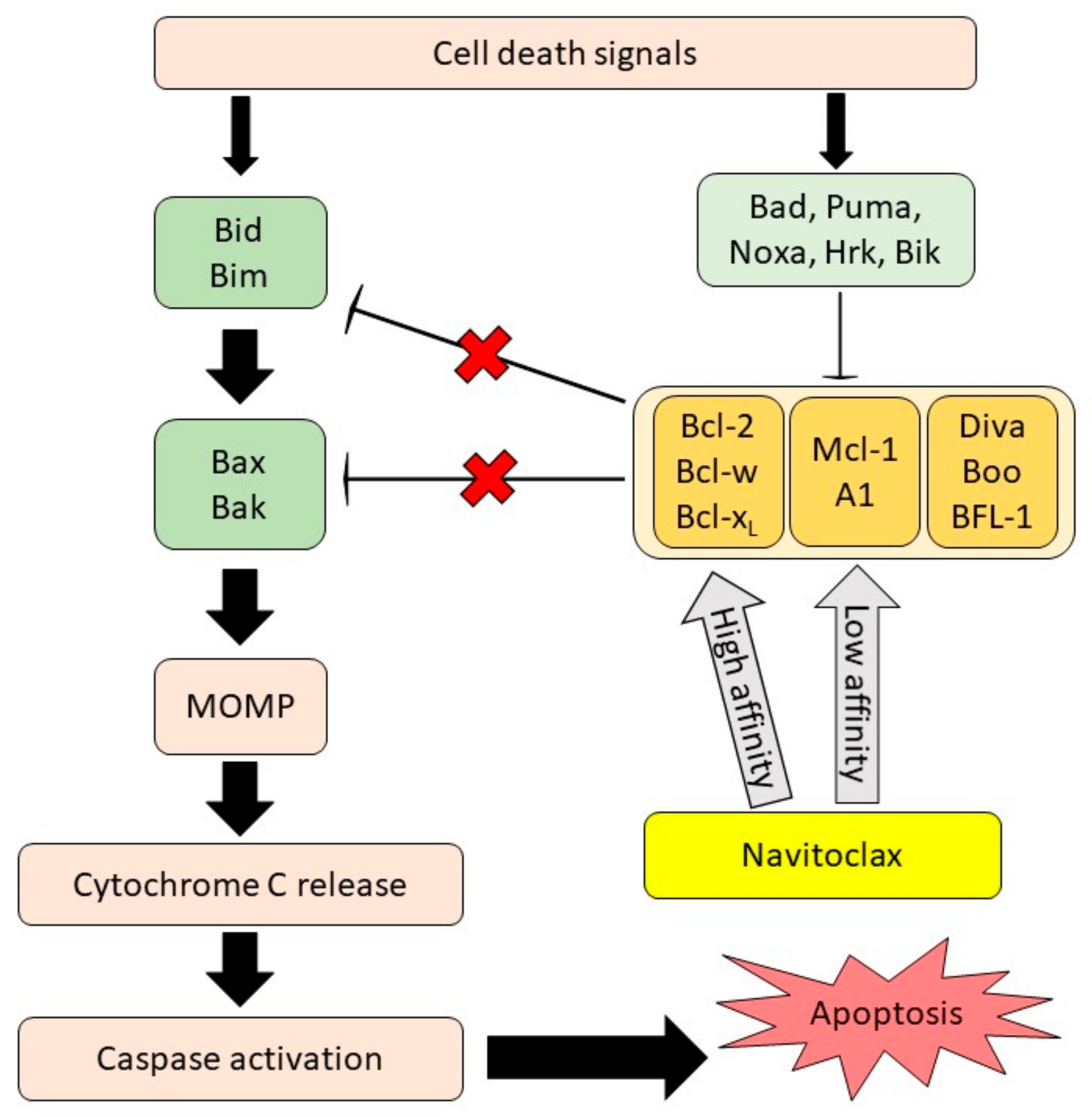

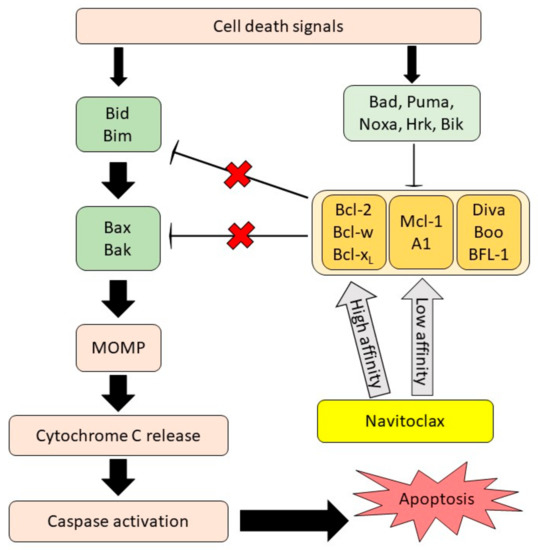

As mentioned above, resistance to cellular apoptosis is one of the cancer hallmark domains as it causes an excessive, uncontrolled proliferation of cancer cells and promotes tumor metastasis. Anti-apoptotic BCL-2 family proteins largely contribute to the survival of cancer cells, as many studies demonstrated the upregulation of these proteins involved in cancer progression and resistance to chemotherapy treatment [13,14,15]. This finding is comparable with the report from The Human Protein Atlas database, where different expression levels of the anti-apoptotic BCL-2 genes and proteins were detected in solid tumors and lymphoid malignancies [16,17]. The BCL-2 family protein is classified into three groups according to its functions and structures. The first group consists of multi-BH domain pro-apoptotic proteins (BAX and BAK), which act as apoptosis effectors; the second group includes the anti-apoptotic proteins (BCL-2, BCL-XL, BCL-W, MCL-1 and BFL-1), which prevent cell apoptosis; and the third group, which is comprised of BH3-only pro-apoptotic proteins (Noxa, Bad, Bim and Puma), can initiate cell apoptosis and counteract certain anti-apoptotic proteins [13,18]. The interaction among the BCL-2 family protein groups is complex. It is characterized by a direct and indirect signaling activation upon receiving a trigger due to cell death together with DNA damage signals. The signal from their interactions can stimulate and also sensitize BH3-only activator proteins. The activation of these proteins triggers the mitochondrial outer membrane permeabilization (MOMP) through the oligomerization of multidomain pro-apoptotic proteins. The stimulation of MOMP leads to cytochrome c release, caspase activation, and eventually apoptosis. However, this can be blocked by multidomain, anti-apoptotic BCL-2 family proteins. BH3-only sensitizer proteins can reverse this inhibition and indirectly induce apoptosis by binding to the multidomain, anti-apoptotic proteins, releasing the BH3-only activator proteins from the anti-apoptotic proteins [19].

The development of various BCL-2 inhibitors as the tumor cells’ apoptosis regulators is evolving as a single drug or administered with other therapeutic agents. Some of them have been implemented in human clinical trials [20] and have been approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) [21,22]. In 2008, a small molecule BH3-mimetic drug called navitoclax was developed as an analogue to ABT-737 and displayed better oral bioavailability than its predecessor [23]. Navitoclax has been widely used in clinical studies for cancer treatment due to its nature as a selective inhibitor of the BCL-2, BCL-XL and BCL-W proteins [23]. It can mimic the function of the BH3-only proteins and bind to the anti-apoptotic BCL-2 proteins, thus allowing the intrinsic apoptosis mechanism activation [24]. The anti-cancer effect of navitoclax mainly relies on the blocking of the BCL-2 family members, as shown in Figure 1. When navitoclax binds to BCL2, BCL-XL or BCL-W, the effectors of apoptosis, namely BAX and BAK, will be released from the BCL-2 proteins to carry out their functions. BAX and BAK will then oligomerize at the outer membrane of the mitochondria and activate caspase, thereby inducing apoptosis [25].

Figure 1.

Navitoclax mechanism of action. Navitoclax potentiates the intrinsic cell death mechanism through the inhibition of anti-apoptotic proteins signal. Navitoclax affinity on anti-apoptotic proteins is varied. MOMP, mitochondrial outer membrane permeabilization, reproduced from [26], Frontiers, 2020.

The mechanism of navitoclax in enhancing cancer cell death is mainly dependent on the mitochondrial intrinsic apoptosis pathway. Navitoclax exhibits significant single-agent efficacy against cancer cells with an overexpression of BCL-2 or BCL-XL proteins [27] and yields synergistic effects with other drugs in various diseases [28]. In a previous review, we presented and discussed the ability of navitoclax to mediate pro-apoptotic and anti-fibrotic action as a single agent in various cancer types [26]. However, the combination therapy of navitoclax is not highlighted and evaluated thoroughly, in light of the fact that the utilization of navitoclax with other chemotherapeutic agents has demonstrated promising, therapeutic outcomes in several solid and non-solid tumor clinical studies. Therefore, this manuscript aims to report the clinical evidence of navitoclax combination therapy meticulously, evaluate the clinical studies’ results and limitations, and provide a proposed future direction of this drug development.

4. Conclusions and Future Prospects

Overall, BCL-2 family members play an essential role in the regulation of cell apoptosis and survival. The dysregulation of BCL-2 proteins results in cell resistance to apoptosis. However, the induced overexpression of anti-apoptotic BCL-2 proteins in cancer cells can provide a new therapeutic strategy to inhibit cancer cell progression and metastasis. Identifying BCL-2 family protein expressions in different tumor types is fundamentally essential to assist in choosing the relevant BCL-2 inhibitors in a combination treatment. Based on the evidence discussed in this review, navitoclax combination therapy in solid and non-solid tumors has been investigated to treat advanced malignancies that are resistant to a single anti-cancer drug [58,61] or to treat cancer relapsed following treatment with a monotherapy agent [60,69]. Navitoclax is known to be a potent and selective inhibitor of BCL-2 and BCL-XL. The effect of navitoclax is not restricted by cell types as its efficacy is proven in a wide range of cancer cell types. Researchers have shown that the function of navitoclax as a BCL-2 family inhibitor can be ensured when the cells have an elevated expression of BCL-2 proteins. Navitoclax has been widely applied in the combination treatment of various cancer types, such as SCLC, endometrial carcinoma, acute myeloid leukemia, and others. However, the complete mechanism of action is still not fully understood. Besides, the timing of navitoclax administration in specific cancer types should be well studied in the future to optimize the effect of navitoclax in overcoming relapsed cancer. To be aware of any possible adverse side effects, a deeper investigation should be conducted to elucidate the interaction of navitoclax with cellular molecules and its downstream metabolic activities in combination with other chemotherapeutic agents.

Author Contributions

N.S.N.H. and S.L.L. searched the literature and drafted the manuscript. A.U., N.N.M.A. and N.F.R. edited and revised the manuscript. M.F.A. and M.F. reviewed and edited the manuscript. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This review was supported by a grant from Ministry of Education, Malaysia (FRGS/1/2019/SKK06/UKM/02/7) and Universiti Kebangsaan Malaysia (UKM).

Acknowledgments

We acknowledge the Ministry of Education, Malaysia (FRGS/1/2019/SKK06/UKM/02/7) and Universiti Kebangsaan Malaysia (UKM) for funding this study.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Hanahan, D.; Weinberg, R.A. The hallmarks of cancer. Cell 2000, 100, 57–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hanahan, D.; Weinberg, R.A. Hallmarks of cancer: The next generation. Cell 2011, 144, 646–674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fouad, Y.A.; Aanei, C. Revisiting the hallmarks of cancer. Am. J. Cancer Res. 2017, 7, 1016–1036. [Google Scholar]

- Llambi, F.; Green, D.R. Apoptosis and oncogenesis: Give and take in the BCL-2 family. Curr. Opin. Genet. Dev. 2011, 21, 12–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perez-mancera, P.A.; Young, A.R.J.; Narita, M. Inside and out: The activities of senescence in cancer. Nat. Rev. Cancer 2014, 14, 547–558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Labi, V.; Erlacher, M. How cell death shapes cancer. Cell Death Dis. 2015, 6, e1675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Razak, N.A.; Abu, N.; Ho, W.Y.; Zamberi, N.R.; Tan, S.W.; Alitheen, N.B.; Long, K.; Yeap, S.K. Cytotoxicity of eupatorin in MCF-7 and MDA-MB-231 human breast cancer cells via cell cycle arrest, anti-angiogenesis and induction of apoptosis. Sci. Rep. 2019, 9, 1514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, C.; Yang, H.; Shi, H.; Wang, X.; Chen, X.; Yuan, Y.; Lin, S.; Wei, Y. Distinct contributions of angiogenesis and vascular co-option during the initiation of primary microtumors and micrometastases. Carcinogenesis 2011, 32, 1143–1150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valastyan, S.; Weinberg, R.A. Tumor metastasis: Molecular insights and evolving paradigms. Cell 2011, 147, 275–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pavlova, N.N.; Thompson, C.B. The emerging hallmarks of cancer metabolism. Cell Metab. 2016, 23, 27–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DeBeradinis, R.J.; Chandel, N.S. Fundamentals of cancer metabolism. Sci. Adv. 2016, 2, e1600200. [Google Scholar]

- Palanissami, G.; Paul, S.F.D. RAGE and its ligands: Molecular interplay between glycation, inflammation, and halmarks of cancer—A Review. Horm. Cancer 2018, 9, 295–325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Czabotar, P.E.; Lessene, G.; Strasser, A.; Adams, J.M. Control of apoptosis by the BCL-2 protein family: Implications for physiology and therapy. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2014, 15, 49–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reed, J.C. Apoptosis-targeted therapies for cancer. Cancer Cell 2003, 3, 17–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amundson, S.A.; Myers, T.G.; Scudiero, D.; Kitada, S.; Reed, J.C.; Fornace, A.J. An informatics approach identifying markers of chemosensitivity in human cancer cell lines. Cancer Res. 2000, 60, 6101–6110. [Google Scholar]

- D’Aguanno, S.; Del Bufalo, D. Inhibition of anti-apoptotic Bcl-2 proteins in preclinical and clinical studies: Current overview in cancer. Cells 2020, 9, 1287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campbell, K.J.; Tait, S.W.G. Targeting BCL-2 regulated apoptosis in cancer. Open Biol. 2018, 8, 180002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, J.K.; Then, S.M.; Mazlan, M.; Raja Abdul Rahman, R.N.; Jamal, R.; Wan Ngah, W.Z. Gamma-tocotrienol acts as a BH3 mimetic to induce apoptosis in neuroblastoma SH-SY5Y cells. J. Nutr. Biochem. 2016, 31, 28–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ng, S.Y.; Davids, M.S. Selective Bcl-2 inhibition to treat chronic lymphocytic leukemia and non-hodgkin lymphoma. Clin. Adv. Hematol. Oncol. 2014, 12, 224–229. [Google Scholar]

- ClinicalTrials.gov. Available online: https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/results?cond=&term=bcl-2+inhibitor%2C+cancer&cntry=&state=&city=&dist=&Search=Search (accessed on 28 May 2021).

- Raedler, L.A. Venclexta (Venetoclax) first BCL-2 inhibitor approved for high-risk relapsed chronic lymphocytic leukemia. J. Hematol. Oncol. Pharm. 2017, 7, 53–55. [Google Scholar]

- Reed, J.C. Bcl-2 on the brink of breakthroughs in cancer treatment. Cell Death Differ. 2018, 25, 3–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tse, C.; Shoemaker, A.R.; Adickes, J.; Anderson, M.G.; Chen, J.; Jin, S.; Johnson, E.F.; Marsh, K.C.; Mitten, M.J.; Nimmer, P.; et al. ABT-263: A potent and orally bioavailable Bcl-2 family inhibitor. Cancer Res. 2008, 68, 3421–3428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Delbridge, A.R.D.; Strasser, A. The BCL-2 protein family, BH3-mimetics and cancer therapy. Cell Death Differ. 2015, 22, 1071–1080. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roberts, A.W.; Seymour, J.F.; Brown, J.R.; Wierda, W.G.; Kipps, T.J.; Khaw, S.L.; Carney, D.A.; He, S.Z.; Huang, D.C.S.; Xiong, H.; et al. Substantial susceptibility of chronic lymphocytic leukemia to BCL2 inhibition: Results of a phase I study of Navitoclax in patients with relapsed or refractory disease. J. Clin. Oncol. 2012, 30, 488–496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohamad Anuar, N.N.; Nor Hisam, N.S.; Liew, S.L.; Ugusman, A. Clinical review: Navitoclax as a pro-apoptotic and anti-fibrotic agent. Front. Pharmacol. 2020, 11, 1817. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tahir, S.K.; Wass, J.; Joseph, M.K.; Devanarayan, V.; Hessler, P.; Zhang, H.; Elmore, S.W.; Kroeger, P.E.; Tse, C.; Rosenberg, S.H.; et al. Identification of expression signatures predictive of sensitivity to the Bcl-2 family member inhibitor ABT-263 in small cell lung carcinoma and leukemia/lymphoma cell Lines. Mol. Cancer Ther. 2010, 9, 545–557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ackler, S.; Mitten, M.J.; Foster, K.; Oleksijew, A.; Refici, M.; Tahir, S.K.; Xiao, Y.; Tse, C.; Frost, D.J.; Fesik, S.W.; et al. The Bcl-2 Inhibitor ABT-263 enhances the response of multiple chemotherapeutic regimens in hematologic tumors In Vivo. Cancer Chemother. Pharmacol. 2010, 66, 869–880. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Falzone, L.; Salomone, S.; Libra, M. Evolution of cancer pharmacological treatments at the turn of the third millennium. Front. Pharmacol. 2018, 9, 1300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DeVita, V.T.; DeVita-Raeburn, E.; Moxley, J.H. Intensive combination chemotherapy and X-irradiation in Hodgkin’s disease. Cancer Res. 2016, 76, 1303–1304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moxley, J.H.; De Vita, V.T.; Brace, K.; Frei, E. Intensive combination chemotherapy and X-irradiation in Hodgkin’s disease. Cancer Res. 1967, 27, 1258–1263. [Google Scholar]

- Devita, V.T.; Serpick, A.A.; Carbone, P.P. Combination chemotherapy in the treatment of advanced Hodgkin’s disease. Ann. Intern. Med. 1970, 73, 881–895. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, P.J.; Cheng, H.; Ou, X.Q.; Zeng, L.J.; Wu, X.; Liu, Y.M.; Lin, Z.; Tang, Y.N.; Wang, S.Y.; Zhang, H.Y.; et al. Safety and efficacy of S-1 chemotherapy in recurrent and metastatic nasopharyngeal carcinoma patients after failure of platinum-based chemotherapy: Multi-institutional retrospective analysis. Drug Des. Dev. Ther. 2014, 8, 1083–1087. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Ershler, W.B. Capecitabine monotherapy: Safe and effective treatment for metastatic breast cancer. Oncologist 2006, 11, 325–335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vogel, C.L.; Nabholtz, J. Monotherapy of metastatic breast cancer: A review of newer agents. Oncologist 1999, 4, 17–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suvarna, V.; Singh, V.; Murahari, M. Current Overview on the Clinical Update of Bcl-2 anti-apoptotic inhibitors for cancer therapy. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 2019, 862, 172655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stevens, M.; Frobisher, C.; Hawkins, M.; Jenney, M.; Lancashire, E.; Reulen, R.; Taylor, A.; Winter, D. The British childhood cancer survivor study: Objectives, methods, population structure, response rates and initial descriptive information. Pediatr. Blood Cancer 2008, 50, 1018–1025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, K.B.; Cabanillas, M.E.; Lazar, A.J.; Williams, M.D.; Sanders, D.L.; Ilagan, J.L.; Nolop, K.; Lee, R.J.; Sherman, S.I. Clinical responses to Vemurafenib in patients with metastatic papillary thyroid cancer harboring BRAFV600E mutation. Thyroid 2013, 23, 1277–1283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Johnson, D.B.; Estrada, M.V.; Salgado, R.; Sanchez, V.; Doxie, D.B.; Opalenik, S.R.; Vilgelm, A.E.; Feld, E.; Johnson, A.S.; Greenplate, A.R.; et al. Melanoma-specific MHC-II expression represents a tumour-autonomous phenotype and predicts response to anti-PD-1/PD-L1 therapy. Nat. Commun. 2016, 7, 10582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shen, Q.; Li, J.; Mai, J.; Zhang, Z.; Fisher, A.; Wu, X.; Li, Z.; Ramirez, M.R.; Chen, S.; Shen, H. Sensitizing non-small cell lung cancer to BCL-XL-targeted apoptosis. Cell Death Dis. 2018, 9, 986. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- William, W.N., Jr.; Glisson, B.S. Novel strategies for the treatment of small-cell lung carcinoma. Nat. Rev. Clin. Oncol. 2011, 8, 611–619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yap, T.A.; Omlin, A.; De Bono, J.S. Development of therapeutic combinations targeting major cancer signaling pathways. J. Clin. Oncol. 2013, 31, 1592–1605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bayat Mokhtari, R.; Homayouni, T.S.; Baluch, N.; Morgatskaya, E.; Kumar, S.; Das, B.; Yeger, H. Combination therapy in combating cancer. Oncotarget 2017, 8, 38022–38043. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schirrmacher, V. From chemotherapy to biological therapy: A review of novel concepts to reduce the side effects of systemic cancer treatment (review). Int. J. Oncol. 2019, 54, 407–419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baudino, T.A. Targeted cancer therapy: The next generation of cancer treatment. Curr. Drug Discov. Technol. 2015, 12, 3–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakajima, W.; Sharma, K.; Hicks, M.A.; Le, N.; Brown, R.; Krystal, G.W.; Harada, H. Combination with Vorinostat overcomes ABT-263 (Navitoclax) resistance of small cell lung cancer. Cancer Biol. Ther. 2016, 17, 27–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anighoro, A.; Bajorath, J.; Rastelli, G. Polypharmacology: Challenges and opportunities in drug discovery department of life science informatics, B-IT, LIMES program unit chemical biology and medicinal. J. Med. Chem. 2014, 57, 7874–7887. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Q.; Wang, H.G. Anti-cancer drug discovery and development Bcl-2 family small molecule inhibitors. Commun. Integr. Biol. 2012, 5, 557–565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ibrahim, N.; Nazimi, A.J.; Ajura, A.J.; Nordin, R.; Latiff, Z.A.; Ramli, R. The clinical features and expression of bcl-2, Cyclin D1, p53, and proliferating cell nuclear antigen in syndromic and nonsyndromic keratocystic odontogenic tumor. J. Craniofac. Surg. 2016, 27, 1361–1366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wolter, K.G.; Wang, S.J.; Henson, B.S.; Wang, S.; Griffith, K.A.; Kumar, B.; Chen, J.; Carey, T.E.; Bradford, C.R.; D’Silva, N.J. (-)-Gossypol inhibits growth and promotes apoptosis of human head and neck squamous cell carcinoma In Vivo. Neoplasia 2006, 8, 163–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwab, E.; Chen, J.; Huynh, J.; Ji, J.; Arora, M.; Cho, M.; Kim, E. Rational strategies for combining Bcl-2 inhibition with targeted drugs for anti-tumor synergy. J. Cancer Treat. Diagn. 2019, 3, 7–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shoemaker, A.R.; Mitten, M.J.; Adickes, J.; Ackler, S.; Refici, M.; Ferguson, D.; Oleksijew, A.; O’Connor, J.M.; Wang, B.; Frost, D.J.; et al. Activity of the Bcl-2 family inhibitor ABT-263 in a panel of small cell lung cancer xenograft models. Clin. Cancer Res. 2008, 14, 3268–3277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, J.; Zhou, Y.; Huang, H.-C.; Mitchison, T.J. Navitoclax (ABT-263) accelerates apoptosis during drug-induced mitotic arrest by antagonizing Bcl-XL. Cancer Res. 2011, 71, 4518–4526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, E.Y.; Gong, E.Y.; Shin, J.S.; Moon, J.H.; Shim, H.J.; Kim, S.M.; Lee, S.; Jeong, J.; Gong, J.H.; Kim, M.J.; et al. Human breast cancer cells display different sensitivities to ABT-263 based on the level of survivin. Toxicol. Vitr. 2018, 46, 229–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, I.H.; Jung, J.Y.; Kim, S.H.; Yoo, E.S.; Cho, N.P.; Lee, H.; Lee, J.Y.; Hong, S.D.; Shin, J.A.; Cho, S.D. ABT-263 exhibits apoptosis-inducing potential in oral cancer cells by targeting C/EBP-homologous protein. Cell. Oncol. 2019, 42, 357–368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gandhi, L.; Camidge, D.R.; De Oliveira, M.R.; Bonomi, P.; Gandara, D.; Khaira, D.; Hann, C.L.; McKeegan, E.M.; Litvinovich, E.; Hemken, P.M.; et al. Phase I study of Navitoclax (ABT-263), a novel Bcl-2 family inhibitor, in patients with small-cell lung cancer and other solid tumors. J. Clin. Oncol. 2011, 29, 909–916. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rudin, C.M.; Hann, C.L.; Garon, E.B.; Ribeiro De Oliveira, M.; Bonomi, P.D.; Camidge, D.R.; Chu, Q.; Giaccone, G.; Khaira, D.; Ramalingam, S.S.; et al. Phase II study of single-agent Navitoclax (ABT-263) and biomarker correlates in patients with relapsed small cell lung cancer. Clin. Cancer Res. 2012, 18, 3163–3169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mukherjee, N.; Skees, J.; Todd, K.J.; West, D.A.; Lambert, K.A.; Robinson, W.A.; Amato, C.M.; Couts, K.L.; Van Gulick, R.; Macbeth, M.; et al. MCL1 inhibitors S63845/MIK665 plus Navitoclax synergistically kill difficult-to-treat melanoma cells. Cell Death Dis. 2020, 11, 443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Missiaglia, E.; Williamson, D.; Chisholm, J.; Wirapati, P.; Pierron, G.; Petel, F.; Concordet, J.-P.; Thway, K.; Oberlin, O.; Pritchard-Jones, K.; et al. PAX3/FOXO1 fusion gene status is the key prognostic molecular marker in Rhabdomyosarcoma and significantly improves current risk stratification. J. Clin. Oncol. 2012, 30, 1670–1677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ommer, J.; Selfe, J.L.; Wachtel, M.; O’Brien, E.M.; Laubscher, D.; Roemmele, M.; Kasper, S.; Delattre, O.; Surdez, D.; Petts, G.; et al. Aurora A kinase inhibition destabilizes PAX3-FOXO1 and MYCN and synergizes with Navitoclax to induce Rhabdomyosarcoma cell death. Cancer Res. 2020, 80, 832–842. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gibson, W.J.; Hoivik, E.A.; Halle, M.K.; Taylor-Weiner, A.; Cherniack, A.D.; Berg, A.; Holst, F.; Zack, T.I.; Werner, H.M.J.; Staby, K.M.; et al. The genomic landscape and evolution of endometrial carcinoma progression and abdominopelvic metastasis. Nat. Genet. 2016, 48, 848–855. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palisoul, M.; Mutch, D.G. The clinical management of inoperable endometrial carcinoma. Expert Rev. Anticancer Ther. 2016, 16, 515–521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jurado, R.; Lopez-flores, A.; Alvarez, A.; García-López, P. Cisplatin cytotoxicity is increased by Mifepristone in cervical carcinoma: An In Vitro and In Vivo study. Oncol. Rep. 2009, 22, 1237–1245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, J.; Zhang, X.; Chen, C.; Huang, Y.; Yu, X.; Li, X. Ultra PH-sensitive polymeric nanovesicles co-deliver Doxorubicin and Navitoclax for synergetic therapy of endometrial carcinoma. Biomater. Sci. 2020, 8, 2264–2273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, G.; Deng, Y.; Pan, L.; Ouyang, W.; Feng, H.; Wu, J.; Chen, P.; Wang, J.; Chen, Y.; Luo, J. Clinical significance of the BRAF V600E mutation in PTC and its effect on radioiodine therapy. Endocr. Connect. 2018, 8, 754–763. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McArthur, G.A.; Chapman, P.B.; Robert, C.; Larkin, J.; Haanen, J.B. Safety and efficacy of Vemurafenib in BRAFV600E and BRAFV600K mutation-positive melanoma (BRIM-3): Extended follow-up of a phase 3, randomised, open-label study. Lancet Oncol. 2014, 15, 323–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brose, M.S.; Cabanillas, M.E.; Cohen, E.E.W.; Wirth, L.J.; Riehl, T.; Yue, H.; Sherman, P.S.I.; Sherman, E.J. Vemurafenib in patients with BRAFV600E-positive metastatic or unresectable papillary thyroid cancer refractory to radioactive iodine: A non-randomized, multicentre, open-label, phase 2 trial. Lancet Oncol. 2017, 17, 1272–1282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dadu, R.; Shah, K.; Busaidy, N.L.; Waguespack, S.G.; Habra, M.A.; Ying, A.K.; Hu, M.I.; Bassett, R.; Jimenez, C.; Sherman, S.I.; et al. Efficacy and tolerability of Vemurafenib in patients with BRAFV600E-positive papillary thyroid cancer: M.D. Anderson cancer center off label experience. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2014, 100, E77–E81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeong, J.H.; Oh, J.M.; Jeong, S.Y.; Lee, S.W.; Lee, J.; Ahn, B.C. Combination treatment with the BRAF V600E inhibitor Vemurafenib and the BH3 mimetic Navitoclax for BRAF-mutant thyroid carcinoma. Thyroid 2019, 29, 540–548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siegel, R.L.; Miller, K.D.; Jemal, A. Cancer statistics, 2016. CA Cancer J. Clin. 2016, 66, 7–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abulwerdi, F.; Liao, C.; Liu, M.; Azmi, A.S.; Aboukameel, A.; Mady, A.S.; Gulappa, T.; Cierpicki, T.; Owens, S.; Zhang, T.; et al. A novel small-molecule inhibitor of Mcl-1 blocks pancreatic cancer growth In Vitro and In Vivo. Mol. Cancer Ther. 2015, 13, 565–575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takahashi, H.; Chen, M.C.; Pham, H.; Matsuo, Y.; Ishiguro, H.; Reber, H.A.; Takeyama, H.; Hines, O.J.; Eibl, G. Simultaneous knock-down of Bcl-XL and Mcl-1 induces apoptosis through Bax activation in pancreatic cancer cells. Biochim. Biophys. Acta BBA 2013, 1833, 2980–2987. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mazumder, S.; Choudhary, G.S.; Al-harbi, S.; Almasan, A. Mcl-1 Phosphorylation defines ABT-737 resistance that can be overcome by increased NOXA expression in leukemic B-cells. Cancer Res. 2012, 72, 3069–3079. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abid, M.; Sonawane, Y.A.; Contreras, J.I.; Rana, S.; Natarajan, A. Recent advances in cancer drug development: Targeting induced myeloid cell leukemia-1 (Mcl-1) differentiation protein. Curr. Med. Chem. 2017, 24, 4488–4514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lowman, X.H.; Mcdonnell, M.A.; Kosloske, A.; Odumade, O.A.; Jenness, C.; Karim, C.B.; Jemmerson, R.; Kelekar, A. The pro-apoptotic function of Noxa in human leukemia cells is regulated by the kinase Cdk5 and by glucose. Mol. Cell 2010, 40, 823–833. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kour, S.; Rana, S.; Contreras, J.I.; King, H.M.; Robb, C.M.; Sonawane, Y.A.; Bendjennat, M.; Crawford, A.J.; Barger, C.J.; Kizhake, S.; et al. CDK5 inhibitor downregulates Mcl-1 and sensitizes pancreatic cancer cell lines to Navitoclax. Mol. Pharmacol. 2019, 96, 419–429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Surien, O.; Ghazali, A.R.; Masre, S.F. Lung cancers and the roles of natural compounds as potential chemotherapeutic and chemopreventive agents. Biomed. Pharmacol. J. 2019, 12, 85–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Inoue, S.; Riley, J.; Gant, T.W.; Dyer, M.J.S.; Cohen, G.M. Apoptosis induced by histone deacetylase inhibitors in leukemic cells is mediated by Bim and Noxa. Leukemia 2007, 21, 1773–1782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hollink, I.H.I.M.; Van Den Heuvel-Eibrink, M.M.; Arentsen-Peters, S.T.C.J.M.; Pratcorona, M.; Abbas, S.; Kuipers, J.E.; Van Galen, J.F.; Beverloo, H.B.; Sonneveld, E.; Kaspers, G.J.J.L.; et al. NUP98/NSD1 characterizes a novel poor prognostic group in acute myeloid leukemia with a distinct HOX gene expression pattern. Blood J. Am. Soc. Hematol. 2011, 118, 3645–3656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thanasopoulou, A.; Tzankov, A.; Schwaller, J. Potent co-operation between the NUP98-NSD1 fusion and the FLT3-ITD mutation in acute myeloid leukemia induction. Haematologica 2014, 99, 1465–1471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Akiki, S.; Dyer, S.A.; Grimwade, D.; Ivey, A.; Abou-zeid, N.; Borrow, J.; Jeffries, S.; Caddick, J.; Newell, H.; Begum, S.; et al. NUP98-NSD1 fusion in association with FLT3-ITD mutation identifies a prognostically relevant subgroup of pediatric acute myeloid leukemia patients suitable for monitoring by real time quantitative PCR. Genes Chromosomes Cancer 2013, 52, 1053–1064. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ostronoff, F.; Othus, M.; Gerbing, R.B.; Loken, M.R.; Raimondi, S.C.; Hirsch, B.A.; Lange, B.J.; Petersdorf, S.; Radich, J.; Appelbaum, F.R.; et al. NUP98/NSD1 and FLT3/ITD coexpression is more prevalent in younger aml patients and leads to induction failure: A COG and SWOG report. Blood J. Am. Soc. Hematol. 2014, 124, 2400–2408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kivioja, J.L.; Thanasopoulou, A.; Kumar, A.; Kontro, M.; Yadav, B.; Majumder, M.M.; Javarappa, K.K.; Eldfors, S.; Schwaller, J.; Porkka, K.; et al. Dasatinib and Navitoclax act synergistically to target NUP98-NSD1+/FLT3-ITD+ acute myeloid leukemia. Leukemia 2019, 33, 1360–1372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Koss, B.; Morrison, J.; Perciavalle, R.M.; Singh, H.; Rehg, J.E.; Williams, R.T.; Opferman, J.T. Requirement for antiapoptotic MCL-1 in the survival of BCR-ABL B-lineage acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Blood J. Am. Soc. Hematol. 2013, 122, 1587–1598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Budhraja, A.; Turnis, M.E.; Churchman, M.L.; Kothari, A.; Yang, X.; Xu, H.; Kaminska, E.; Panetta, J.C.; Finkelstein, D.; Mullighan, C.G.; et al. Modulation of Navitoclax sensitivity by Dihydroartemisinin-mediated MCL-1 repression in BCR-ABL+ B-lineage acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Clin. Cancer Res. 2017, 23, 7558–7568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).