Abstract

Social media platforms such as Facebook, Instagram, and Twitter are an inevitable part of our daily lives. These social media platforms are effective tools for disseminating news, photos, and other types of information. In addition to the positives of the convenience of these platforms, they are often used for propagating malicious data or information. This misinformation may misguide users and even have dangerous impact on society’s culture, economics, and healthcare. The propagation of this enormous amount of misinformation is difficult to counter. Hence, the spread of misinformation related to the COVID-19 pandemic, and its treatment and vaccination may lead to severe challenges for each country’s frontline workers. Therefore, it is essential to build an effective machine-learning (ML) misinformation-detection model for identifying the misinformation regarding COVID-19. In this paper, we propose three effective misinformation detection models. The proposed models are long short-term memory (LSTM) networks, which is a special type of RNN; a multichannel convolutional neural network (MC-CNN); and k-nearest neighbors (KNN). Simulations were conducted to evaluate the performance of the proposed models in terms of various evaluation metrics. The proposed models obtained superior results to those from the literature.

1. Introduction

The rapid growth of the Internet and related technologies dramatically changed society in all aspects. The popularity of Internet-related technologies is increasing on a daily basis. The Internet has opened up a new effective and powerful global communication medium without any barriers regarding location and time. Social media is an interactive and computer-based tool that facilitates sharing knowledge, thoughts, views, opinions, experiences, documents, audio, and video by forming virtual communities and networks.

The growth of the Internet and the ubiquitous usage of the Web and technology tools have created a vast amount of data. According to the latest report of the International Telecommunication Union (ITU), 93% of the global population has access to a network, and 70% of the world’s youth are using the Internet [1]. This enabled users to interact using different social media platforms and express their opinions on different issues. The amount of data generated from social media platforms has attracted both researchers and practitioners to extract underlying valuable information. Since the early 1990s, researchers used generated text as data in the area of natural language processing (NLP). Sentiment analysis (SA), as a subfield of NLP, has gained popularity to understand the attitude of the writer. SA can classify text written into predefined subjective categories (i.e., positive, negative, or neutral) or measure the strength of a sentiment [2]. Machine learning (ML) adopts algorithms and uses data to build models with minimal human intervention. ML models are also deployed in SA areas for various objectives [3,4,5].

SA is used in different areas such as tourism [6], dialects on social media [7], hotel reviews [8,9], customer reviews [10], politics and campaigns [11,12], mental health [13], stock returns [14], investment [15], climate change [16], real estate [5], movie reviews [17], and product reviews [18]. The importance of SA lies in its powerful ability to gain better insights, achieve a competitive advantage, and reach optimal decisions. For instance, Philander et al. [2] used SA to understand public opinions towards hospitality firms. Moreover, the authors in [19] discussed the influence of SA on physical and online marketing, implication on product sales, and influence of pricing strategy. Shuyuan Deng et al. [14] discussed the causality between sentiments and stock returns at an hourly level. In the area of climate change, Jost et al. [16] applied SA to find the level of agreement between climate researchers and policymakers, and suggested collaboration between them. Another practical implication of SA is assessing customers in making purchasing decisions [20]. While the importance and implications of SA are endless, misleading information is a serious threat in the area.

Misleading information has many definitions, for example, “news articles that are intentionally and verifiably false, and could mislead readers” [21]. It has been a concern long before using social media, which can alter people’s beliefs. For example, in response to a letter back in 1968, an editor writes, “while high-minded individuals debate the potential future misuse of computer-based information systems, major computer users and manufacturers presently continue, thoughtlessly and routinely, to gather personal and misleading data from all applicants for employment” [22]. In another earlier study, the author [23] performed a series of experiments to explore what happens when a person receives misinformation at different points of times. Misleading information can have significant effects on many aspects such as consumer decision making [24], elections [25], education [26], and medicine [27].

Undertaking online misinformation is a global concern across official agencies. For example, the European Commission (EC), a branch of the European Union (EU), is dealing with both online disinformation and misinformation to ensure the protection of European values and democratic systems. The EC has developed several initiatives to protect the public from intentional deception and from fake news that is believed to be true. Those initiatives include action plans, codes of practices, and fact checkers [28]. In August 2020, UNESCO published a handbook on fake news and disinformation in media. The handbook was useful, especially during the COVID-19 pandemic, to minimize the negative impact on the public’s consciousness and attitudes [29].

While past research investigated misleading information for various objectives, the performance of the models using health misinformation data was not satisfactory. To bridge this research gap, this work specifically focuses on building better models to detect COVID-19 misinformation on Twitter. This exploratory work uses a general framework as an attempt to propose models that outperform implemented algorithms in the literature.

As such, this work attempts to answer the two following research questions (RQ): RQ1: which machine-learning models exist to detect healthcare misinformation on SNS? RQ2: can we propose machine-learning models that effectively outperform existing ones in RQ1?

To address the two research questions above, an extensive literature review was conducted, followed by building ML models to bridge the research gap in detecting COVID-19 misinformation on Twitter.

2. Related Work

This section presents related work in the area of health misinformation, detecting misinformation on social networking services, the use of machine-learning models to detect misinformation, misinformation on Twitter, and different misinformation datasets.

2.1. Health Misinformation

Health misinformation is defined as “incorrect information that contradicts current established medical understanding, or biased information that covers or promotes only a subset of facts” [30]. It is mainly due to a lack of scientific evidence [31] and spreads more easily than scientific knowledge does [32]. Many challenges are associated with misinformation, such as conspiracy theories, persuasion, and moral decision making [33]. Researchers investigated the area of health misinformation in previous diseases [34,35,36]. For example, Venkatesan et al. [34] discussed factors that influence the extent of misinformation about Parkinson’s on online social networks. Moreover, the authors in [35] discussed the antivaccine campaign during the Ebola outbreak in 2014. It has caused people to be more reluctant towards vaccination, affecting their health statuses [36].

The World Health Organization (WHO) [37] declared a global pandemic caused by COVID-19, an infectious disease that first appeared in December 2019, caused by a newly discovered coronavirus. As of the time of writing this paper, there have been 119 million reported cases of COVID-19, 67.2 million recovered cases, and 2.63 million deaths. The pandemic caused global lockdowns and travel restrictions, which had consequences on economies, public health, education, and social disruption. It is essential in such a pandemic to rely on trusted news sources and avoid misinformation that can have serious effects. As stated by the general director of WHO, “fake news spreads faster and more easily than this virus, and is just as dangerous” [38].

The threats and dangers of health misinformation have great negative effects on public health. A patient may share specific dosing information that is not generally applicable [34]. It could also affect the trust between individuals and health authorities [39]. Moreover, it could cause beliefs of incorrect linkages between vaccines and diseases, and limit treatment options or preventive behaviors [40,41]. Another danger is that it could affect the quality of life and risk of mortality [42]. Amira Ghenai [43] reported the danger of changing correct decisions about how to treat an illness because of misinformation.

2.2. Detecting Misinformation on Social Networking Services (SNS)

The increased popularity of social media caused the swift spread of misinformation on a wide range [44,45]. Information spread through social media impacts a wide range within less time. If it misinformation, it has great global impact, and its effects may extend from one’s life to threatening the entirety of society socially, economically, and in terms of health. Misinformation is now propagated through social media, which has an adverse effect on imprecise data related to vaccinations and medicines. The groups who do not support vaccination alleged that it might cause serious health issues such as autism in children. They succeeded to an extent in making individuals hesitate to accept or refuse vaccinations among children, which greatly increased the number of avertible diseases [46]. Such fears and fake news followed the COVID-19 pandemic. The main challenge faced by researchers in classifying data into true information and fake news is the exponentially large count of data available on social media, and misinformation detection is a popular research domain. Many researchers investigated the classification of misinformation and proposed various methods for detecting it.

COVID-19 health misinformation is widespread in various social media platforms, and spreads even more rapidly than news from reliable channels [47]. This phenomenon could worsen the impact of COVID-19, which is highly dependent on individuals’ actions related to health precautions such as social distancing, vaccination, and mask use. The authors in [48] emphasized that COVID-19 misinformation can hinder behaviors to reduce the spread of the virus. They found that sharing WHO graphics to address misinformation can reduce misconceptions.

Zhou et al. [49] viewed fake news as a serious threat to freedom of expression. The authors explained eight different concepts related to fake news: deceptive news, false news, satire news, disinformation, misinformation, cherry picking, clickbait, and rumors. The intention of the concepts could be to mislead, entertain, or be undefined. In order to analyze fake news, the authors explained expert-based and crowd-sourced manual fact checking, which might not scale with the volume of generated information. Therefore, automatic fact-checking techniques relying on NLP and other tools were necessary and conducted in two stages: fact extraction and fact checking. Our paper focuses on misinformation concerning the most recent infectious disease, the new coronavirus.

Obiala et al. [50] analyzed the accuracy of news articles related to COVID-19 shared through different social media platforms. They found that the majority of news shares were through Facebook, and misinformation was about hand washing. Apuke et al. [51] studied factors that predict misinformation on social media in Nigeria, and the attributes of spreading such news such as ignorance, awareness, peer pressure, and attention seeking. Similarly, the authors in [52] built a model to examine factors affecting social media use (Twitter, Facebook, Snapchat, WhatsApp) and their impact on managing crises in Sub-Saharan Africa. In Bangladesh, Najmul Islam et al. [53] also developed a model for misinformation sharing on social media (Facebook, Twitter, LinkedIn, Instagram) during COVID-19, and found that those suffering from deficient self-regulation are more likely to share unverified information.

The authors in [54] conducted a qualitative design related to COVID-19 misinformation on Telegram and WhatsApp, and reported the consequences to be psychological, economic, and health-related. Chakraborty et al. [55] examined misinformation on Twitter by analyzing positive and negative tweets related to COVID-19. In a study of 853 participants who used Facebook or Twitter, the authors [56] found that participants were willing to share fake news that they would have been able to identify as untrue. Mejova et al. [57] used the Facebook Ad Library to examine possible misinformation during the pandemic. The authors found that the most visible ads did not provide basic information about COVID-19, and 5% contained possible misinformation. Dimitrov et al. [58] introduced TweetsCOV19, a publicly available database of more than 8 million tweets, where retweeting behavior could be studied for different objectives such as emergency warnings, health-related campaigns, and misinformation. This paper proposes machine-learning models to detect misinformation on Twitter.

2.3. Machine-Learning Models to Detect Misinformation

Some basic machine-learning models used for classifying data on the basis of their concepts are recurrent neural networks, support vector machine, k-nearest neighbors, logistic regression, random forest, convolutional neural networks, bidirectional gated recurrent unit, capture, score, and integrate (CSI), sentiment-aware multimodal embedding, hierarchical attention network, and dEFEND. The following briefly explains each ML model.

A recurrent neural network (RNN) is a more powerful artificial neural network (ANN)-based computing model that simulates a biological neural-network system and is well-suited for many significant applications. Unlike traditional feed-forward neural-network models, the recurrent layer of RNN has feedback loops. RNN also has a short-term internal memory that allows for it to persist in its state to influence the current output and next sequence of inputs. RNN assumes that the impact of previous and future elements determines the following outputs in the sequence, in contrast with other neural network models. Long short-term memory (LSTM) networks are a particular class of RNN that are capable of understanding long-term dependencies. Special units are also implemented, along with the regular units of recurrent neural networks. LSTM units employ a memory cell that helps information to persist for longer. The data stored in the memory are controlled by a set of gates: input, output, and forget gates. Forget gates decide whether information should be kept or thrown away, and what type of information to be kept. An input gate is responsible for modifying the cell state, and the output gate identifies the next hidden state. The working of LSTM is quite similar to that of RNN, except that it is performed within the LSTM units or cells.

Support vector machine (SVV) is a well-known supervised-learning-based classification and regression model used to classify data into a number of different categories [59]. The SVM model tries to identify an N-dimensional hyperplane that categorizes the given data into separate classes. The main objective of an SVM-based classifier is to find the right hyperplane that holds the maximal margin among various hyperplanes that exist for classifying the given data points. SVM is mainly split into two types, linear and nonlinear SVM. A linear SVM classifies linearly separable data points, whereas the latter efficiently mapped nonlinearly separable data values to their corresponding classes. The general form of the classifying hyperplane is given by Equation (1).

where W is the weight vector, x is the input feature vector, and b is the bias. The new data are classified into class 1 if , and class 2 if , or vice versa. SVM can also be used for multiclass classification. The authors in [59,60,61] used SVM for misinformation or fake-news detection.

The k-nearest neighbor (K-NN) algorithm is used to either classify a data point on the basis of a categorical outcome or to predict a numerical outcome [62]. K-NN is an automated data-driven algorithm that is based on identifying k data points in the training dataset that are similar to a new data point for classification purposes. The neighbors are then used to classify the new data point. The distance between data points is measured using the predictor values to calculate the used measurement distance. Euclidean distance is the most popular for distance measurement among others, such as Manhattan distance, Mahalanobis distance, maximum coordinate distance, and granularity-enhanced Hamming (GEH) distance [63]. If the difference between two points x and y was denoted as , a metric conforms to four criteria [64]:

- 1.

- non-negativity

- 2.

- only identity

- 3.

- symmetry

- 4.

- triangle inequality

Ali et al. [65] proposed a semantic K-NN (SK-NN) algorithm to overcome the poor accuracy of the traditional K-NN for large volumes of multicategorical training datasets, which scans the entire dataset and categories to classify a single data point. Thus, the SK-NN improves ML performance by using a semantic itemization and bigram model to filter a training dataset.

It is a probability-based machine-learning algorithm for classifying data into two or more discrete classes. As the name suggests, it generates a regression model for estimating the probability value of the data point, represented by an n-dimensional vector to be classified into class 1. It considers dependent and independent variables in a data point as a linear function given by Equation (2).

where X = is the n-dimensional feature vector, are regression coefficients, and y is the dependent target value. Logistic regression is a special case of linear regression that works on the basis of logistic function, also known as a sigmoid function. The sigmoid function is an S-shaped curve that lies between 0 and 1. Equation (3) represents the sigmoid function.

In a binary classification scenario, let p(y) be the probability that, with a given data point, X is mapped to class 1; then, p(y) − 1 represents the probability that X belongs to class 2. Logistic regression models can be divided into three different types on the basis of the number of distinct classes. They are binomial (binary classification), multinomial (multiclass classification), and ordinal (ordered multiclass classification). There are a variety of works in fake-news detection using linear regression [66,67,68,69].

Random forest is also a supervised learning classifier based on decision tree (DT) [61]. It is a simple, flexible, and widely used machine-learning algorithm for classifying documents or other data. As the name suggests, it forms diverse decision trees and trains this model in bagging techniques. Each decision tree is trained and tested by using its own sample data values. Lastly, results are combined, and the best solution is identified by using a voting method. The random forest randomly selects samples of the dataset, builds a decision tree for each sample, and makes predictions on each decision tree. The voting algorithm on these results performs a significant role in selecting feasible solutions from these predictions, which is considered to be the final classification result.

A convolutional neural network [70] is a deep-learning-based neural network used to classify texts, images, speech, and so on. It is mainly used for image classification. The convolutional operation is performed in these neural networks. It is a feed-forward neural network, and its behavior is inspired by the visual cortex of animals. Hidden layers are known as convolution layers. The multichannel convolutional neural network (MC-CNN) is mainly used to capture temporal correlations by forming three convolutional layers with kernels along the time axis [71]. It strengthens the connection between features, which improves robustness against errors [72]. However, the MC-CNN ignores spatial correlations and considers single-sensor temporal correlation, which might limit performance as more features are present in the dataset.

A bidirectional gated recurrent unit (BiGRU) is a model for processing a sequence, and it consists of two GRUs. One is used for accepting input in the forward direction, and the other is to accept input from the backward direction. BiGRU is considered to be a bidirectional RNN with only forget and input gates [73].

Ruchansky et al. [74] proposed a new hybrid model based on deep learning for fake-news detection, commonly known as capture, score, and integrate (CSI). This model considers the characteristics of users, articles, and group characteristics of users who transmit misinformation or fake news. This model has two main modules: one for drawing out the temporal characteristics of the news (response), and the other for modeling and scoring the characteristics of the user (source). CSI is used for extracting the temporal pattern of the activities of the user.

Sentiment-aware multimodal embedding [75] is another model for detecting fake news on social media platforms that identifies fake news on the basis of the sentiments of the user, content, and images of the news.

Hierarchical attention network (HAN) is one of the most recent and best-performing deep-learning-based classification models. Yang et al. [76] presented this model for classifying documents in 2016. The main two features of the HAN that differentiate it from already available methods are the hierarchical nature and attention mechanism. The hierarchical behavior of the text content is exploited by the HAN for classifying the text documents, and it classifies the documents with the help of an attention mechanism. Both word and sentence hierarchy are used here, and the attention mechanism identifies the most important word. HAN has both word and sentence encoders. Word-level information is handled by a word encoder, the result is given to the next encoder, this sentence encoder summarizes the information on the sentence level, and the final layer predicts the output probabilities. HAN also has separate attention layers for both words and sentences. The attention layer aligns and weighs words in terms of their significance in the essence of the sentence at the word level. Each sentence is aligned on the basis of its importance in document classification. On the basis of the semantic structure, HAN classifies the documents.

dEFEND is a fake-news detection algorithm based on explainable deep neural networks that generate both estimated output and corresponding explanations. It applies HAN to the contents of the article, and a pairwise attention model between user comment and corresponding article content for identifying misinformation. The dEFEND model performs detailed analysis on propagation details of fake and real news, top and trending news, and claims and their interconnected news. The system extracts propagation details for identifying the sharing dynamics of both fake and real news. The propagation of fake news is much faster than that of real news [77,78].

Research in fake-news detection is a priority, especially during pandemics. One of the objectives in using a systematic literature review method [3] is to find the most valuable machine-learning algorithms for detecting fake news on social media. Of manual fact-checking sites, the two most popular are snopes.com and factcheck.org. The authors found that many papers used sentiment analysis as features for classifiers such as hidden Markov models, artificial neural network, naive Bayes, k-nearest neighbors, decision tree, and support vector machines. Similarly, they reviewed recent work and machine-learning text-classification approaches in health informatics to predict and monitor disease outbreaks. They used the bibliometric analysis of publication in scientific databases from 2010 to 2018. The results indicated that Twitter is the most popular data source to perform such analyses. The support vector machine is the most widely used machine-learning algorithm to classify texts. Jamison et al. [79] extended a topology of vaccine misinformation to classify major topics on Twitter. The dataset included 1.8 million tweets from 2014 to 2017, and used manual content analysis followed by latent Dirichlet allocation to extract topics. Lastly, manual content analysis was conducted for each generated topic. The results indicated that safety concerns were the most common theme among antivaccine Twitter data, followed by conspiracies, morality claims, and alternative medicines. The results also suggested that Twitter is a useful platform to “easily share recommendations, remind patients to get vaccinated, and provide links to events” (p. S337). Aphiwongsophon et al. [59] used three machine-learning methods in a proposed system that could identify misinformation from Twitter data, naive Bayes (accuracy, 95.55%), neural network (accuracy, 97.09%), and support vector machine (accuracy, 98.15%). The system consisted of three major parts: data collection, data preprocessing, and machine-learning methods. The data extracted from Twitter API spanned two months in 2017 for the selected topics, including natural events, general issues, and the Thai monarchy. Tweets were collected using hashtags for each topic, and manually labeled as valid or fake. The authors selected the 22 most relevant attributes used in previous studies of the available attributes in a Twitter message. Among those attributes are ID, location, time zone, follower count, retweet count, and creation date. Weka was used to run the three machine-learning methods, and results suggested that fake news has a shorter lifetime than that of valid news. The accuracy of the approach highly depends on correctly labeled training data. The method did not depend on any semantic analyses on Twitter data.

The authors in [80], instead of focusing on machine-learning algorithms to detect Twitter misinformation, presented approaches to assist users in validating news on social media. Existing approaches such as TweetCred, B.S. Detector, Fake News Detector, Fake News AO, and Fake News Check label news as fake or valid. Therefore, the authors presented a browser plugin for Twitter, TrustyTweet, using the design science approach to create new and innovative artifacts. The main objective is to improve media literacy by providing neutral and intuitive hints. It is dependent on indicators of fake news from previous studies such as consecutive capitalization, excessive usage of punctuation, wrong punctuation at the end of sentences, excessive usage and attention grabbing of emoticons, a default account image, and the absence of an official account verification seal (p. 1848). The plugin was developed for the Firefox browser, which shows indicators related to a specific tweet. The results of the study showed that the approach is promising in supporting users on social media by encouraging a learning effect to determine where Twitter data are fake.

Shahan et al. [81] presented a methodology to characterize the two online communities on Twitter of COVID-19 misinformation: misinformed and informed users. Misinformed users are those who are actively posting misinformation, as opposed to informed users who spread true information. The methodology is unique and different from previous studies in that it investigates the sociolinguistic patterns of the two communities. Instead of focusing on Twitter data misinformation, the research focuses on the communities using their content, behaviors, and interactions. The Twitter dataset was collected using the Twitter search API with a set of hashtags and keywords. It was manually categorized by using previously identified 17 categories (e.g., irrelevant, conspiracy, true treatment, true prevention, sarcasm, fake cure, fake treatment). The authors collected 4573 annotated tweets from 3629 authors. The new dataset is called CMU-MisCOV19. A +1 was assigned to true data, and −1 was assigned to misinformation according to the defined categories to differentiate between the two groups of users (informed and misinformed). Network analysis was performed by using the network density of a given tweet. They also used Bot-Hunter to perform bot analyses within the two groups, and found that the percentage of bots within misinformed users was higher. Lastly, linguistic analysis was performed using the Linguistic Inquiry and Word Count program. The results indicated that misinformed users tend to be more informal and use fewer swear words. One of the limitations of the study is the limited timeline of the collected data, which was annotated by only one annotator.

2.4. Misinformation on Twitter

In an exploratory study to counter Twitter misinformation, Gautham Kishore Shahi et al. [82] collected 1500 tweets from between January and mid-July 2020. The study used tweets from fact-checking websites that had been classified as false (or partially false) in addition to a random sample of tweets from publicly available corpus TweetsCOV19. To crawl the websites, BeautifulSoup was used to collect URLs and tweet IDs, which were then used to fetch the tweet using a Python library to access Twitter API, Tweepy. The content of the tweets was analyzed in terms of the used hashtags and emojis, distinctive terms, and emotional and psychological processes using the Linguistic Inquiry and Word Count program. Results suggested that the speed of propagation for Twitter misinformation is the highest among other tweets, and that misinformation tweets are more concerned with discrediting other news.

Lisa Singh et al. [83] presented a study on the propagation of misinformation via Twitter. They first studied conversations and discussions related to COVID-19. They presented this work as a starting point to social media discussions regarding myths, real news, and fake news related to the new pandemic; the world is now severely affected. Twitter shared both reliable and unreliable information on COVID-19, which helps to detect and estimate propagation, and causes misunderstandings among people. Accurate information from reliable sources and misinformation were retweeted several times, and the misinformation retweets were more than those of information from the CDC and WHO. They also revealed myths spreading through Twitter related to COVID-19.

Aswini Thota et al. [4] proposed a dense neural-network-based approach for detecting fake news using FNC-1 data. The study began with data preprocessing (removing stop words and punctuation, stemming) to implement the deep machine-learning algorithms. Their proposed model also indicated the problem of identifying the relationship with actual news, whether related or unrelated, when evaluating the correctness of the reported news with the actual news, which most of the models ignored. They represented text features using the TF-IDF vector model. On the basis of their simulation, they concluded that their proposed model outperformed all the other available models by 2.5%. They obtained entire system accuracy of 94.21%, and the considered stances between news articles with the headline articles were agree, unrelated, disagree, and discuss. The model achieved better results for all these stances except disagree, for which they obtained only 44%. They also implemented this model with BoW and Word2Vec embedding methods. However, accuracy with the pretrained Word2Vec model was very low as compared with that of the BoW and TF-IDF feature-extraction models.

Detecting misinformation on Twitter is also a concern for Arabic tweets. Alquarashi et al. [84] created a dataset of Arabic tweets related to COVID-19 misinformation and annotation, categorizing them into fake or not. Different machine-learning algorithms are applied to detect misinformation: convolutional neural networks, recurrent neural networks, convolutional recurrent neural networks, support vector machine, multinomial naive Bayes, extreme gradient boosting, random forest, and stochastic gradient descent. Misinformation was collected from two websites—the Ministry of Health in Saudi Arabia websites and the WHO—and it was used to manually label misinformation tweets. Although Arabic is considered to be a challenging language in the area of natural language processing due to the existence of different dialects and many grammatical rules, results were promising. Feature selection was effective as a technique to improve the performance of a classifier.

Likewise, Girgis et al. [85] used a deep-learning algorithm to detect misinformation in the LIAR dataset, which includes short online statements labeled for fakeness. Data preprocessing at the sentence level included removing stop words and stemming. After representing each word as a vector (word embedding), results were used as input to different machine-learning algorithms. The results suggested that the best model was the convolutional neural network because of the speed and performance measures.

Tamanna Hossain et al. [86] presented a data corpus named COVIDLIES for evaluating the effectiveness of the fake-news detection models related to COVID-19. They considered misinformation identification as two separate classes: one is detecting misconceptions related to the tweets that are being fact checked, and the second is the identification of its stance, checking whether it disagrees, has no stance, or agrees with the misconceptions. This corpus has 6761 tweets that were annotated by experts, and 86 were considered various misconceptions.

Liming Cui and Dongwon Lee [78] provided a publicly available dataset at GitHub with diverse COVID-19 healthcare misinformation. The dataset, CoAID, includes more than 4200 news items, 290,000 user engagements, and 920 social media platform posts. This benchmark dataset also includes confirmed fake and valid news articles from reliable websites and social media platforms. The main objective is to ease the development of accurate detection of misinformation. Compared to other available datasets (e.g., LIAR, FakeNewsNet, Fake Health), CoAID is different in that it includes fake and valid news in addition to data posted on different social media platforms such as Facebook, Twitter, Instagram, YouTube, and TikTok. Misinformation detection methods rely on machine-learning algorithms such as support vector machine, logistic regressions, random forest, BiGRU, CSI, SAME, Han, and dEFEND. They evaluated the performance of these models on the basis of various evaluation measures such as precision, F score, area under the precision–recall curve (PR-AUC), and recall. The study suggested that complex machine-learning algorithms (such as CNN) outperform simple algorithms.

Given the above-stated related work in detecting misinformation, this paper proposes a more effective misinformation detection model using RNN-based models, specifically the LSTM model, KNN, and MC-CNN. In this study, misinformation models are separately implemented from other models, and the performance of each model is evaluated using various evaluation metrics such as precision, recall, accuracy, F measure, and PR-AUC.

2.5. Misinformation Corpus

Several COVID-19 misinformation corpora were created by various researchers. A few are multilingual, while others are monolingual. This is discussed in provided next.

Gautam Kishore Shahi and Durgesh Nandini [87] presented a multilingual data corpus for fake-news detection named FakeCovid. It is a cross-domain dataset consisting of 7623 COVID-19 related fact-checked news from 92 various websites for fact checking. The news articles were collected between 4 January and 5 May 2020. The collected news articles were manually annotated into 11 different classes on the basis of their content. The presented corpus was collected from 105 countries, consisting of 40 different languages.

COVID-Lies dataset is an annotated corpus for identifying misconceptions on Twitter, and was presented by Hossain et al. [86]. They developed this corpus to accelerate research in the automatic detection of COVID-19 misinformation, specifically on Twitter. They mainly concentrated on 62 different misconceptions, which are most common about the new pandemic, and it contains 6591 tweets related to those misconceptions. Researchers working at the UCI School of Medicine analyzed and annotated these tweets. The annotators first checked whether each tweet conveyed any misconception. If so, researchers also identified whether it propagated this misconception, was not a misconception, or it did not carry any misconception and informative content. These categories are labeled by the categories of agree (pos), disagree (neg), and nostance (na), respectively. It is a well-annotated corpus.

Xinyi Zhou et al. [88] proposed a multimodel misinformation corpus for facilitating research works related to the detection of conspiracies and fake news regarding COVID-19 on social media. They investigated the credibility of news from around 2000 news publishers from January to May 2020 and collected tweets for discussing the spread of this news through Twitter. The annotated collected tweets as reliable or unreliable with distant supervision, and made this misinformation corpus available for noncommercial purposes.

COVID19-Misinformation-Dataset is a large Arabic annotated dataset for misinformation detection constructed by Sarah Alqurashi et al. [84]. They constructed this corpus as a part of their actual work of detecting real-time Arabic misinformation on Twitter by implementing machine-learning models. This repository supplies tweet IDs that were spread between March 2020 and April 2020 with their corresponding annotation. They covered all misinformation in Arabic spread through Arab Twitter in the initial stages of COVID-19, which was significant, misguiding, and had imprecise content. The annotated tweets were classified into 1311 misinformation and 7475 not misinformation instances. The collected tweets were labeled as 1 or 0 on the basis of their credibility, whether misinformation or not. Annotation was performed by two native Arabic speakers, and they reviewed the reported misinformation, which had been collected from the websites of WHO and the Saudi Arabian Health Ministry.

3. Methods

This section briefly covers the dataset used for research, performance metrics of machine-learning models, and the proposed models used in this research.

3.1. CoAID Dataset

Liming Cui and Dongwon Lee [78] proposed a diverse misinformation dataset related to healthcare spread through social media and online platforms, hence the name Covid19 heAlthcare mIsinformation Dataset (CoAID). They collected various healthcare misinformation instances of COVID-19, labeled them, and made them available to the public. CoAID contains fake or misleading news from various websites and other social media platforms. It also includes various user engagements related to such fake news, which were also labeled. CoAID supplies annotated news, claims, and their related tweet replies. Compared to other available datasets, which are all discussed here, CoAID is different. It includes fake and valid news, and claims in addition to user engagements on social media platforms. It consists of a sufficiently large dataset related to user engagements on Twitter, which is properly classified. Hence, CoAID was selected in this work.

3.2. Performance Metrics

Performance or evaluation metrics play a vital role in identifying an optimal model for classification. They evaluate the performance of a model while training the classifier. It is important to select a suitable metric for evaluating classifiers. There are various available evaluation metrics for determining the performance of a model. It is important to carefully select the most adaptable metric when classifying imbalanced data [89]. The majority of the data in an imbalanced dataset belong to a particular class, and the minority to another class in the case of a two-way classification scenario. There is a possibility of bias towards the majority category. So, we need to more carefully evaluate the classifier. Therefore, accuracy, precision, recall, F measure, and PR-AUC are used for evaluating classifier performance.

A confusion matrix is a way to visualize classifier performance. Most evaluation metrics are based on the number of correctly classified evaluated documents. Each row represents the predicted category in a confusion matrix, whereas each column represents the actual category. The matrix compares the actual values with the predicted ones and obtained four matrices: TN, TP, FN, and FP.

- TP or true positive: classifier correctly predicted the observation as positive.

- TN or true negative: classifier correctly predicted the observation as negative.

- FP or false positive: classifier wrongly classified the observation as positive, but it is actually negative.

- FN or false negative: classifier wrongly classified the observation as negative, but it is actually positive.

The confusion matrix is effective in measuring other evaluation metrics such as precision, recall, and accuracy. Various evaluation metrics are displayed in Table 1.

Table 1.

Performance evaluation metrics.

Area under precision–recall curve (PR-AUC): The precision–recall curve is similar to the ROC curve, which is also a performance evaluation metric, especially when the supplied data are heavily imbalanced. PR-AUC is generally used to summarize the precision–recall curve into a single value. If the value of PR-AUC is small, it indicates a bad classifier; a higher value such as 1 indicates an excellent classifier.

3.3. Framework of Proposed Models

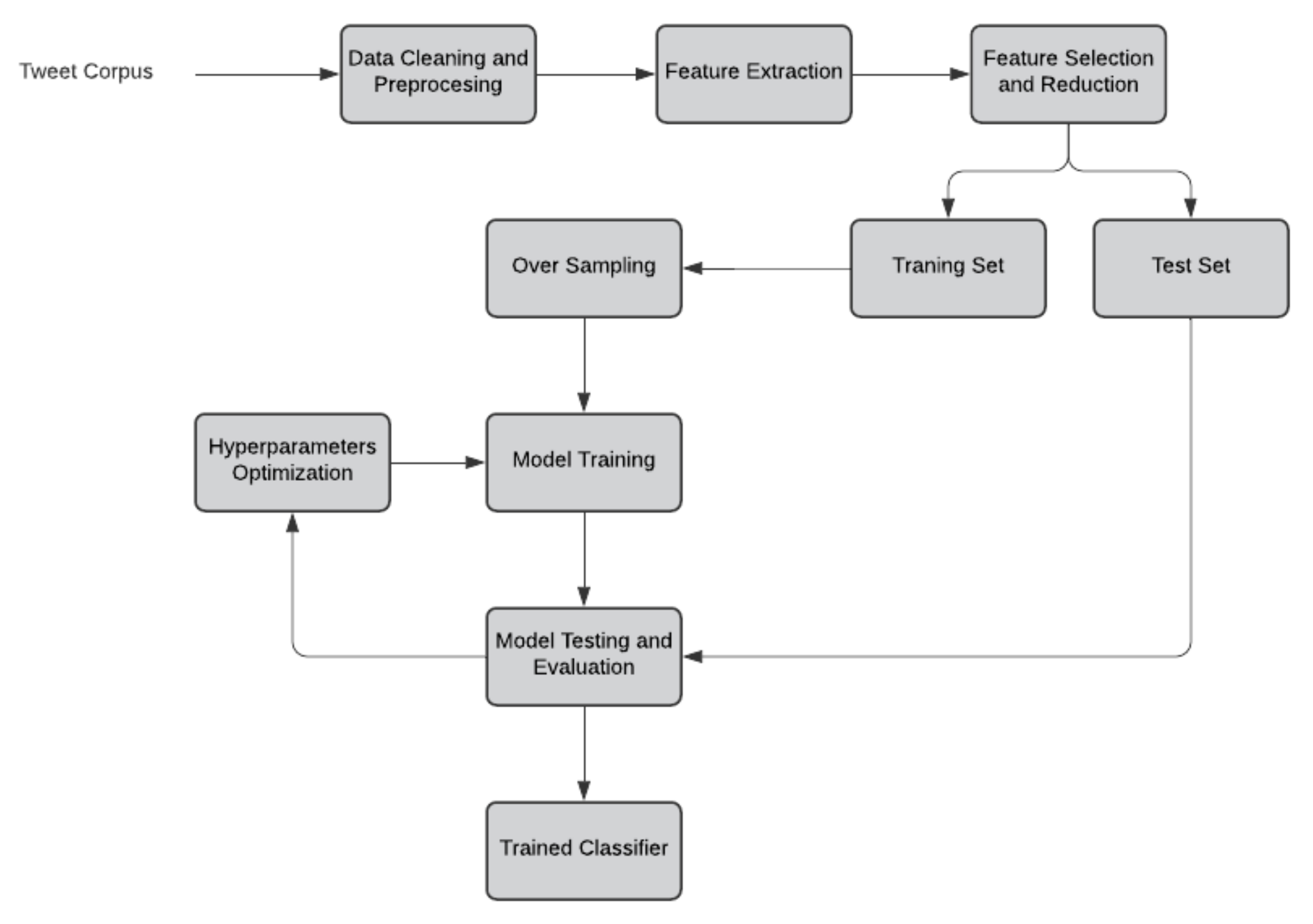

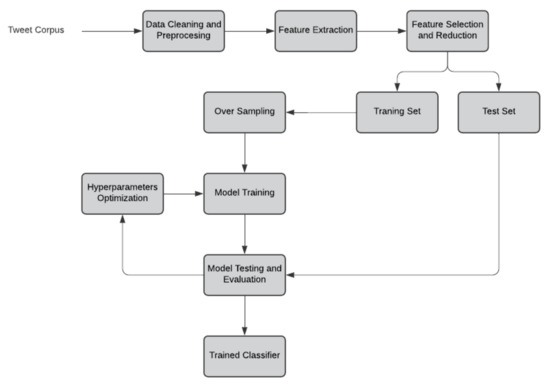

It is very challenging to find the most feasible solution for detecting misinformation on social media platforms such as Twitter. Here, we identify misinformation or fake news transmitted through Twitter as tweets. We propose efficient misinformation-detection models for detecting misinformation or fake news on Twitter. In this section, the proposed models are explained. Figure 1 [90] shows the general architecture that was applied on the proposed models.

Figure 1.

General framework of proposed models.

- 1.

- Data cleaning and preprocessing: they are conducted to eliminate unwanted or irrelevant data or noise in the supplied dataset in order to produce the corpus in a clean and understandable format to improve data accuracy. This step involves the removal of unwanted symbols such as punctuation, special characters, URLs, hashtags, www, HTTPS, and digits. After the data are cleaned, they are preprocessed, including stop-word removal, stemming, and lemmatization. Here, we only removed the stop words.

- 2.

- Feature extraction: After performing data cleaning and preprocessing, it is important to extract the features from the text documents. There are many features, but the most important and commonly used are words. In this step, extracted features are converted into vector representation. For this model, TF-IDF was selected for converting text features into corresponding word-vector representation. The generated vector may be high0dimensional.

- 3.

- Feature selection and dimensionality reduction: dimensionality reduction is important in text classification applications to improve the performance of the proposed models. It reduces the number of features to represent documents by selecting the most essential features to project the documents. Feature selection is most important in dimensionality reduction since it selects the most essential feature, capturing the essence of a document. There are various feature-selection and dimensionality-reduction models, from which singular value decomposition was implemented here, which is one of the most effective models. After dimensionality reduction, the entire corpus is divided into training and test sets.

- 4.

- Sampling the training set: Sampling is mainly performed on an imbalanced corpus to rebalance class distributions. There are mainly two types of sampling: over- and undersampling. Oversampling duplicates or generates new data in the minority class to balance the corpus, whereas undersampling delete or merges the data in the majority class. Oversampling is more effective, since undersampling may delete relevant examples from the majority class. Here, oversampling was performed to rebalance the training corpus.

- 5.

- Training: the proposed model is trained using the training corpus.

- 6.

- Performance evaluation: the performance of each model is evaluated using different evaluation metrics such as accuracy, precision, recall, F measure, and PR-AUC.

- 7.

- Hyperparameter optimization: Hyperparameters are very significant since they directly impact the characteristics of the proposed model, and can even control the performance of the model to be trained. So, for improving the effectiveness of the proposed model, hyperparameters are tuned.

4. Results and Discussion

The proposed models were simulated in the Python programming language using the CoAID misinformation dataset. The Keras framework was utilized for simulating the proposed models. The CoAID dataset contains fake and real claims and news, their corresponding tweets, and their replies. All these data were properly classified into fake and real categories. So, we selected this dataset for simulating our proposed models. The collected tweets from the CoAID dataset were then preprocessed and classified into training and test corpora. The training corpus contained 80% of all extracted tweets. Misinformation-detection models were implemented in Google Colab and trained using the training corpus. Then, the models’ performance was tested and evaluated using various metrics. Table 2 shows the results of the performance evaluation of the proposed models in terms of various performance evaluation metrics.

Table 2.

Performance evaluation metrics of proposed methods.

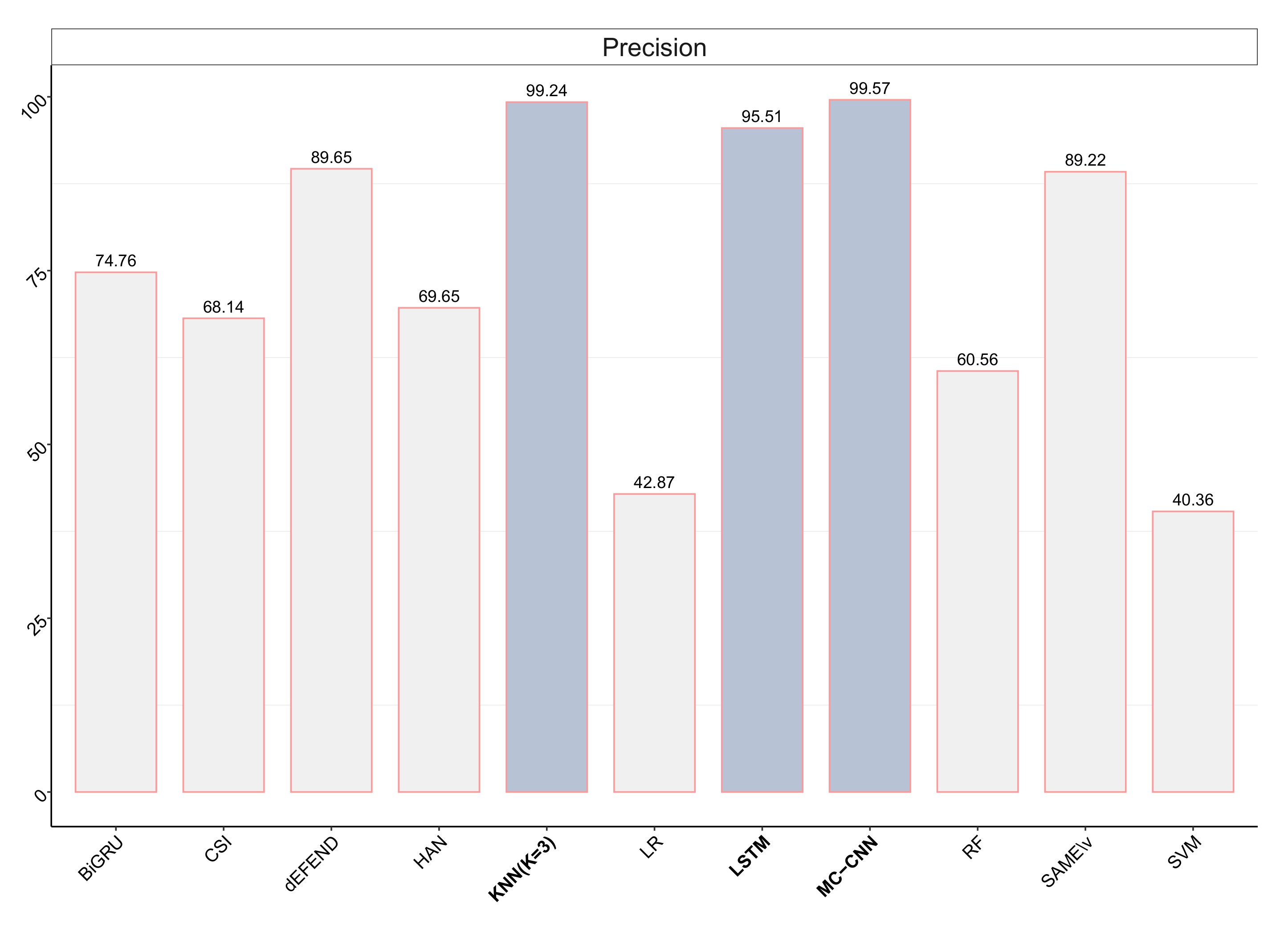

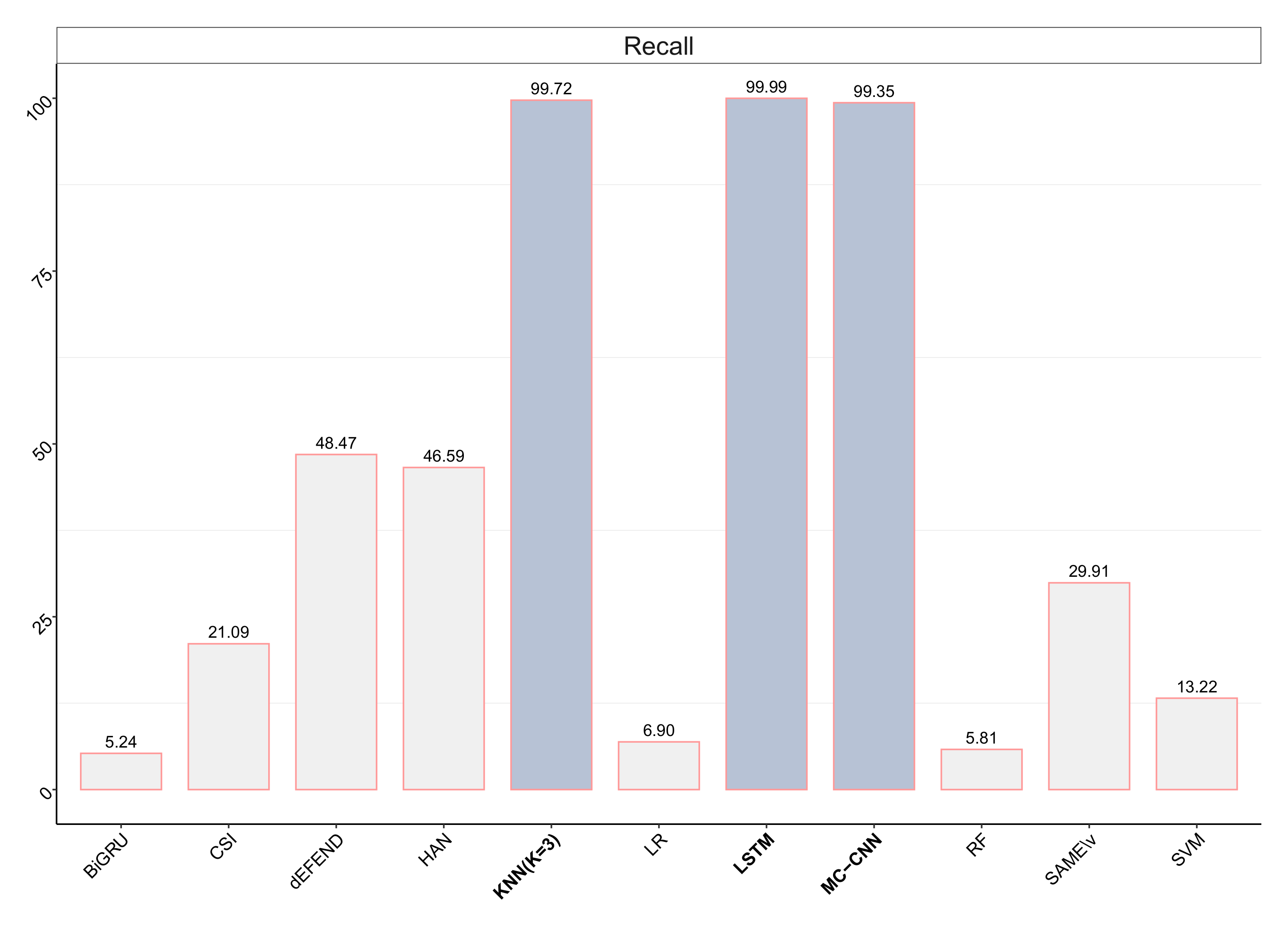

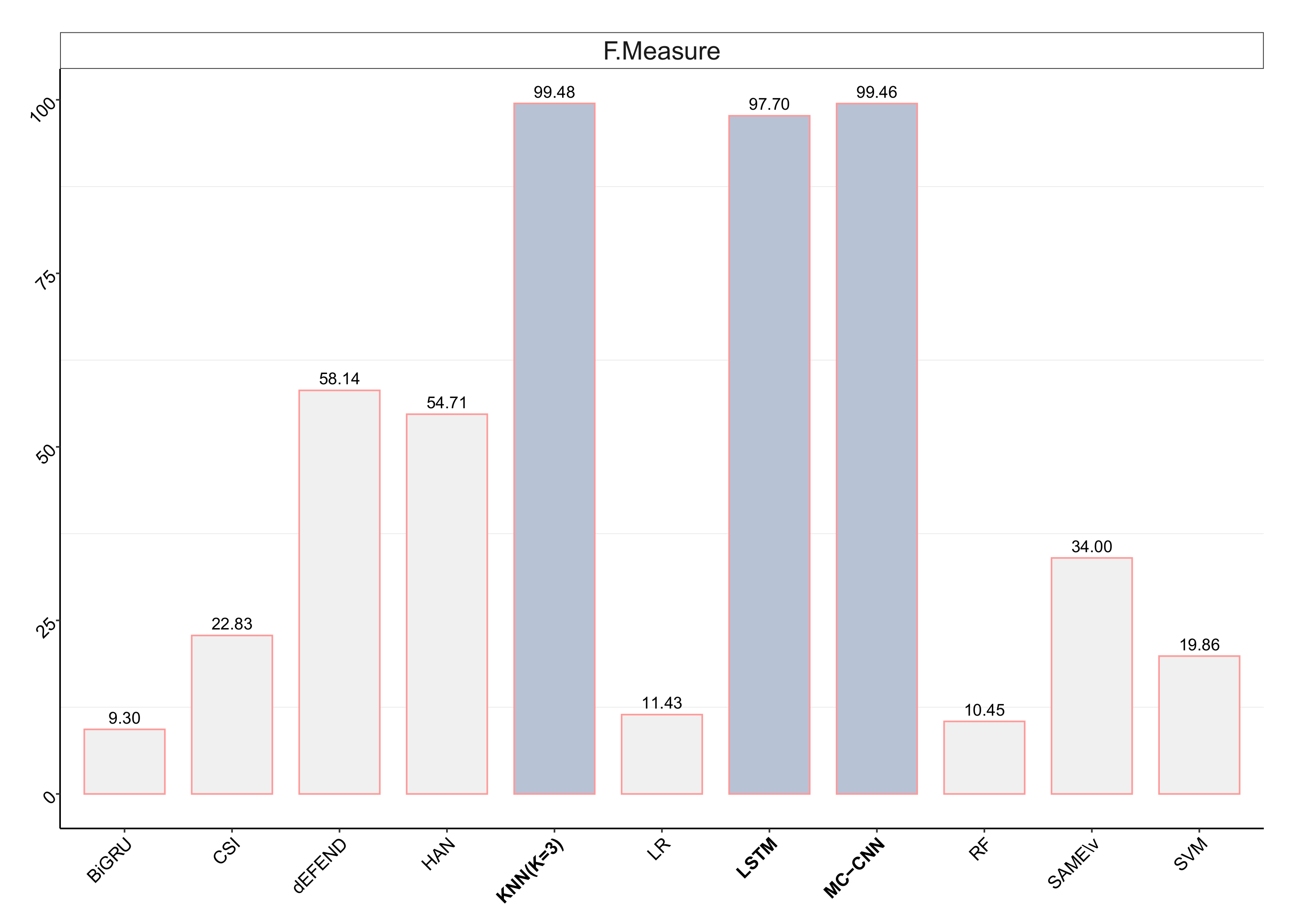

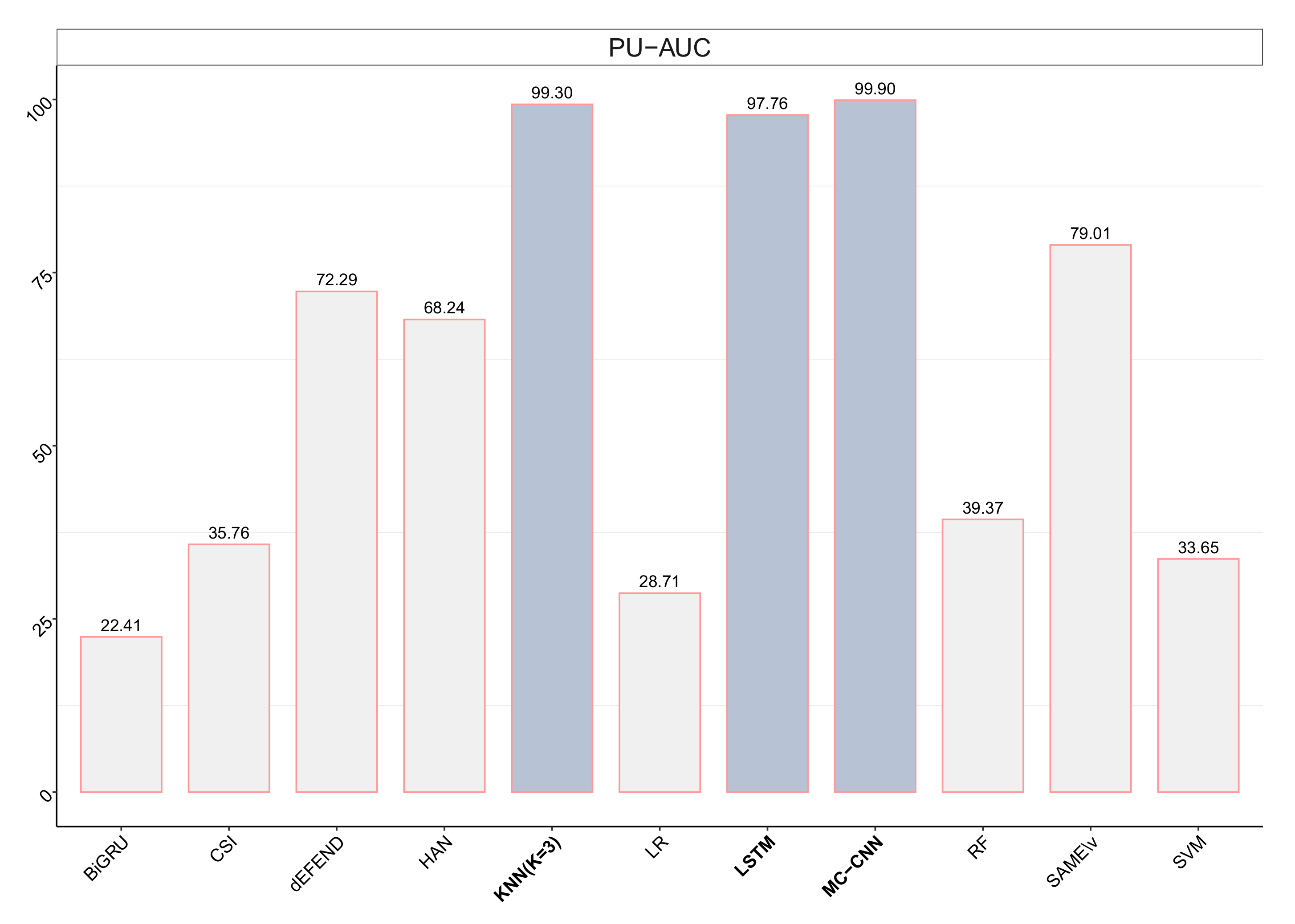

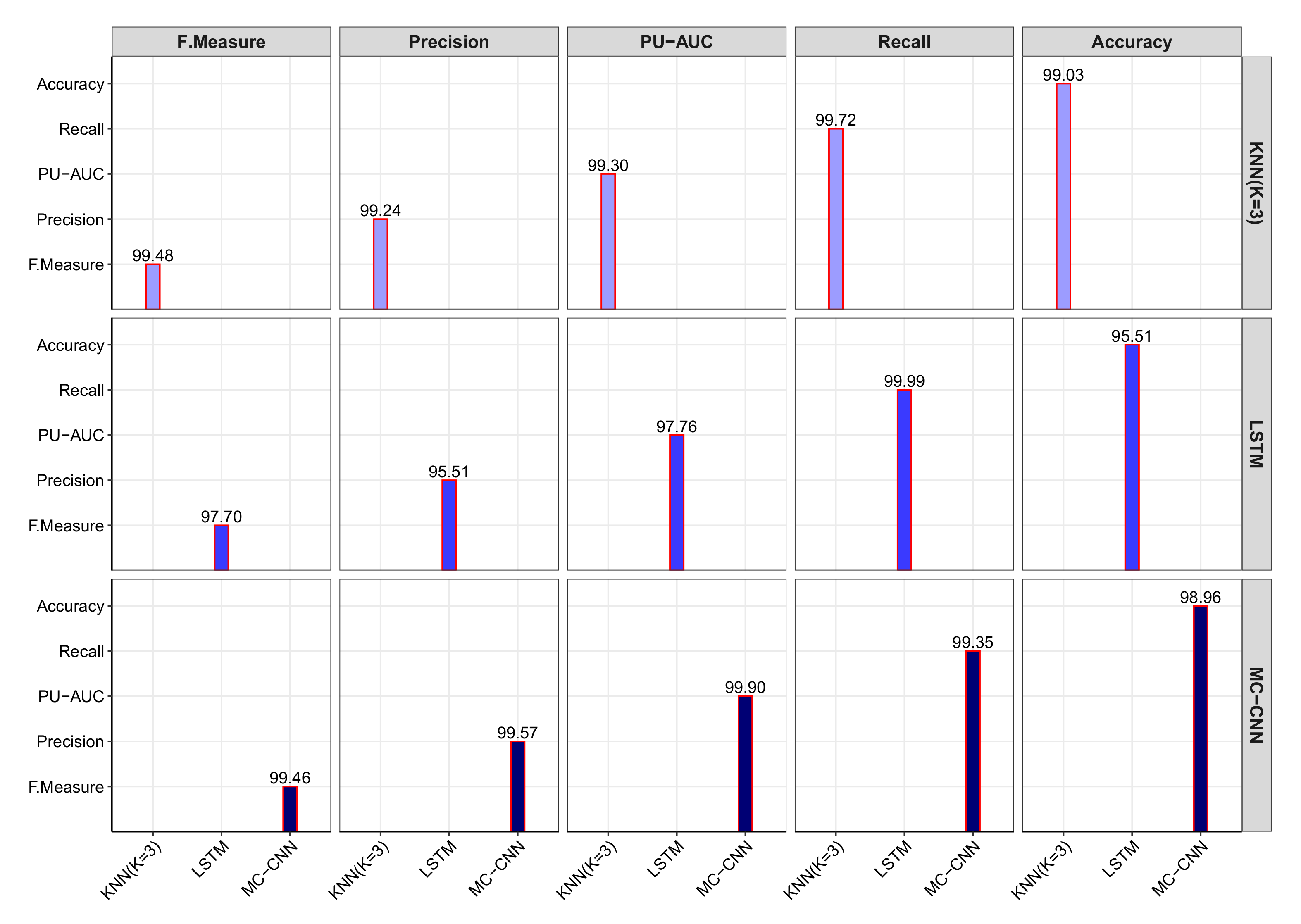

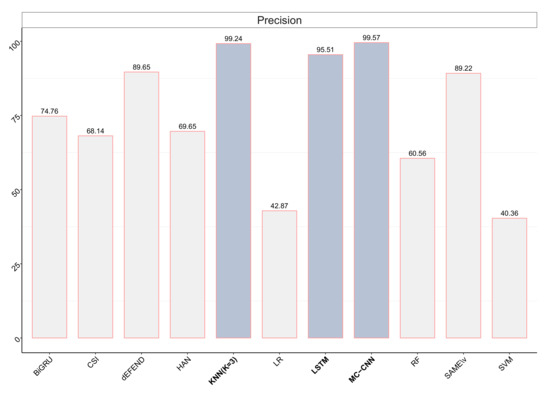

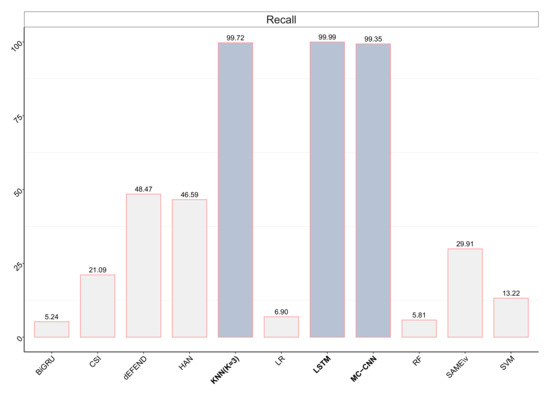

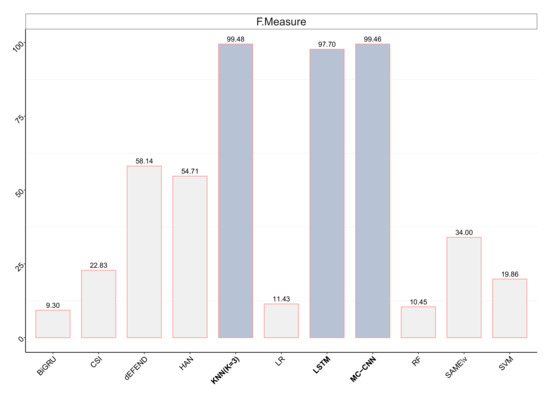

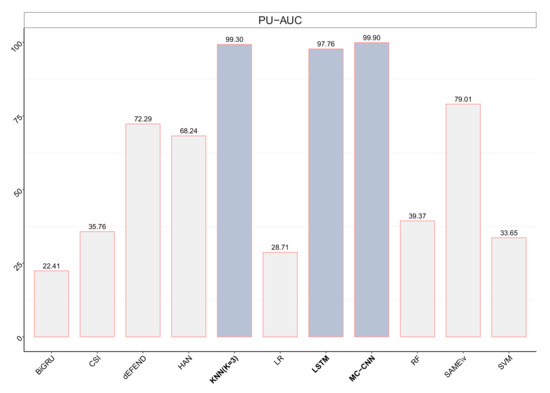

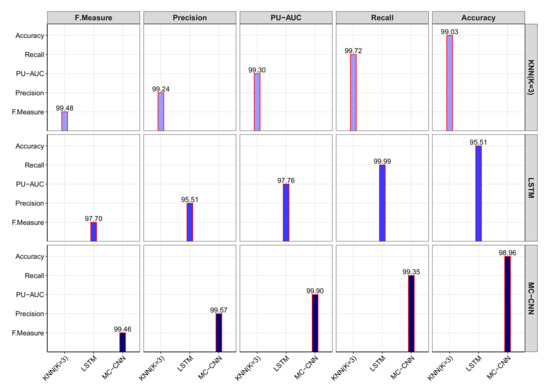

Most of the available fake-news detection corpus is imbalanced. In order to eliminate the biasing effects of an imbalanced corpus, a sampling method is used. In this simulation, the random-oversampling method was employed to effectively handle the challenges of imbalanced data. Models were simulated with and without sampling. Most data in the corpus were classified into majority classes when we did not employ the sampling method. The simulation results of the proposed models (LSTM, MC-CNN, KNN)) were compared with already implemented models in the literature [78]; the comparison was separately plotted for precision, recall, F measure, and PR AUC, shown in Figure 2, Figure 3, Figure 4 and Figure 5, respectively. The results showed that the proposed misinformation-detection models in this study were far more effective than all the other models in the literature. Figure 6 summarizes a comparison between all three proposed models with respect to performance metrics. The results showed that the performance of the three proposed models was within a close range. However, KNN (K = 3) showed relatively better performance than that of LSTM and MC-CNN.

Figure 2.

Precision comparison: proposed models vs. models in the literature [78].

Figure 3.

Recall comparison: proposed models vs. models in the literature [78].

Figure 4.

F measure comparison: proposed models vs. models in the literature [78].

Figure 5.

PU_AUC comparison: proposed models vs. models in the literature [78].

Figure 6.

Comparison between proposed models with respect to all performance evaluation metrics.

5. Conclusions

In an attempt to answer the first research question, a literature review was conducted to investigate existing ML models to detect healthcare misinformation on SNS. As demonstrated in previous sections, there exists a research gap in this area. The performance of previous ML models was unsatisfactory. To bridge the gap, this study proposed a framework for detecting COVID-19 misinformation spread through social media platforms, especially on Twitter. In an attempt to answer the second research question of whether the proposed ML models outperform existing ones, three ML models were implemented. The performance of the proposed models presented in this paper was evaluated using various metrics, namely, precision, recall, F measure, and PR-AUC. The models were simulated using the CoAID misinformation dataset, a healthcare misinformation corpus. In order to avoid a biasing effect, the sampling method was also employed in this work. Our proposed misinformation-detection models more accurately and effectively classified COVID-19-related misinformation available on Twitter. The proposed models are well-suited for misinformation detection in both balanced and imbalanced corpora.

This research has important practical implications. Misinformation is a significant problem on social media, especially when it is health-related. Trusted sources of health information could be a matter of life and death, as in the case for COVID-19. Therefore, this works intends to introduce misinformation-detection models with increased accuracy compared to that of others proposed in the literature [78]. Social media platforms could consider our approach to improve shared online content.

Several limitations exist in the current research. First, the provided evidence is restricted to one dataset and needs to be tested on other datasets related to different areas. Next, it is important to test the generalizability of our results by using misinformation from other social media platforms. Lastly, our model was purely algorithmic, with no evidence of external validity. Future research should consider addressing the limitations of this study. This work is a starting point to further improve misinformation-detection algorithms on social media networks.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, M.N.A.; methodology, M.N.A.; software, M.N.A.; validation, M.N.A. and Z.M.A.; formal analysis, M.N.A. and Z.M.A.; investigation, M.N.A. and Z.M.A.; resources, M.N.A. and Z.M.A.; data curation, M.N.A.; writing—original draft preparation, M.N.A. and Z.M.A.; writing—review and editing, Z.M.A. and M.N.A.; visualization, M.N.A.; supervision, M.N.A. and Z.M.A.; project administration, M.N.A. and Z.M.A. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- ITU—Facts and Figures 2020—Interactive Report. Available online: https://www.itu.int/en/ITU-D/Statistics/Pages/ff2020interactive.aspx (accessed on 20 March 2021).

- Philander, K.; Zhong, Y. Twitter sentiment analysis: Capturing sentiment from integrated resort tweets. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2016, 55, 16–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Durier, F.; Vieira, R.; Garcia, A.C. Can Machines Learn to Detect Fake News? A Survey Focused on Social Media. In Proceedings of the 52nd Hawaii International Conference on System Sciences, HICSS, Grand Wailea, Maui, HI, USA, 8–11 January 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Thota, A.; Tilak, P.; Ahluwalia, S.; Lohia, N. Fake News Detection: A Deep Learning Approach. SMU Data Sci. Rev. 2018, 1, 10. [Google Scholar]

- Sun, D.; Du, Y.; Xu, W.; Zuo, M.Y.; Zhang, C.; Zhou, J. Combining Online News Articles and Web Search to Predict the Fluctuation of Real Estate Market in Big Data Context. Pac. Asia J. Assoc. Inf. Syst. 2015, 6, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alaei, A.R.; Becken, S.; Stantic, B. Sentiment Analysis in Tourism: Capitalizing on Big Data. J. Travel Res. 2019, 58, 175–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alnawas, A.; Arici, N. Sentiment Analysis of Iraqi Arabic Dialect on Facebook Based on Distributed Representations of Documents. ACM Trans. Asian Low-Resour. Lang. Inf. Process. 2019, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Smadi, M.; Qawasmeh, O.; Al-Ayyoub, M.; Jararweh, Y.; Gupta, B. Deep Recurrent neural network vs. support vector machine for aspect-based sentiment analysis of Arabic hotels’ reviews. J. Comput. Sci. 2018, 27, 386–393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hwang, S.Y.; Lai, C.; Jiang, J.J.; Chang, S. The Identification of Noteworthy Hotel Reviews for Hotel Management. Pac. Asia J. Assoc. Inf. Syst. 2014, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Binder, M.; Heinrich, B.; Klier, M.; Obermeier, A.; Schiller, A. Explaining the Stars: Aspect-based Sentiment Analysis of Online Customer Reviews. In Proceedings of the 27th European Conference on Information Systems—Information Systems for a Sharing Society, ECIS, Stockholm and Uppsala, Sweden, 8–14 June 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Ceron, A.; Curini, L.; Iacus, S.M. Using Sentiment Analysis to Monitor Electoral Campaigns: Method Matters—Evidence From the United States and Italy. Soc. Sci. Comput. Rev. 2015, 33, 3–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sandoval-Almazan, R.; Valle-Cruz, D. Sentiment Analysis of Facebook Users Reacting to Political Campaign Posts. Digit. Gov. Res. Pract. 2020, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davcheva, E. Text Mining Mental Health Forums-Learning From User Experiences. In Proceedings of the ECIS 2018, Portsmouth, UK, 23–28 June 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Deng, S.; Huang, Z.J.; Sinha, A.P.; Zhao, H. The Interaction between Microblog Sentiment and Stock Returns: An Empirical Examination. MIS Q. 2018, 42, 895–918. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, S.; Kwak, D.H.; Wu, J.; Sinha, A.; Zhao, H. Classifying Investor Sentiment in Microblogs: A Transfer Learning Approach. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Information Systems (ICIS 2018), San Francisco, CA, USA, 13–16 December 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Jost, F.; Dale, A.; Schwebel, S. How positive is “change” in climate change? A sentiment analysis. Environ. Sci. Policy 2019, 96, 27–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wollmer, M.; Weninger, F.; Knaup, T.; Schuller, B.; Sun, C.; Sagae, K.; Morency, L. YouTube Movie Reviews: Sentiment Analysis in an Audio-Visual Context. IEEE Intell. Syst. 2013, 28, 46–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, Z.; Xing, M.; Zhang, D.; Ma, B.; Wang, T. A Context-Dependent Sentiment Analysis of Online Product Reviews based on Dependency Relationships. In Proceedings of the 35th International Conference on Information Systems: Building a Better World Through Information Systems, ICIS, Auckland, New Zealand, 14–17 December 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Srivastava, D.P.; Anand, O.; Rakshit, A. Assessment, Implication, and Analysis of Online Consumer Reviews: A Literature Review. Pac. Asia J. Assoc. Inf. Syst. 2017, 9, 43–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lak, P.; Turetken, O. The Impact of Sentiment Analysis Output on Decision Outcomes: An Empirical Evaluation. AIS Trans. Hum. Comput. Interact. 2017, 9, 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Moravec, P.L.; Kim, A.; Dennis, A.R. Flagging fake news: System 1 vs. System 2. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Information Systems (ICIS 2018), San Francisco, CA, USA, 13–16 December 2018; pp. 1–17. [Google Scholar]

- Abbott, R.J. Letters to the Editor: Gathering of Misleading Data with Little Regard for Privacy. Commun. ACM 1968, 11, 377–378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loftus, E. Reacting to blatantly contradictory information. Mem. Cogn. 1979, 7, 368–374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Wessel, M.; Thies, F.; Benlian, A. A Lie Never Lives to be Old: The Effects of Fake Social Information on Consumer Decision-Making in Crowdfunding. In Proceedings of the European Conference on Information Systems, Münster, Germany, 26–29 May 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Allcott, H.; Gentzkow, M. Social Media and Fake News in the 2016 Election. J. Econ. Perspect. 2017, 31, 211–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Rosenberg, S.A.; Elbaum, B.; Rosenberg, C.R.; Kellar-Guenther, Y.; McManus, B.M. From Flawed Design to Misleading Information: The U.S. Department of Education’s Early Intervention Child Outcomes Evaluation. Am. J. Eval. 2018, 39, 350–363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bianchini, C.; Truccolo, I.; Bidoli, E.; Mazzocut, M. Avoiding misleading information: A study of complementary medicine online information for cancer patients. Libr. Inf. Sci. Res. 2019, 41, 67–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Commision, E. Tackling Online Disinformation. Available online: https://digital-strategy.ec.europa.eu/en/policies/online-disinformation (accessed on 9 May 2021).

- UNESCO. Fake News: Disinformation in Media. Available online: https://en.unesco.org/news/unesco-published-handbook-fake-news-and-disinformation-media (accessed on 9 May 2021).

- Hou, R.; Pérez-Rosas, V.; Loeb, S.; Mihalcea, R. Towards Automatic Detection of Misinformation in Online Medical Videos. In Proceedings of the 2019 International Conference on Multimodal Interaction, Suzhou, China, 14–18 October 2019; pp. 235–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Bautista, J.R.; Zhang, Y.; Gwizdka, J. Healthcare professionals’ acts of correcting health misinformation on social media. Int. J. Med. Inform. 2021, 148, 104375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suarez-Lledo, V.; Alvarez-Galvez, J. Prevalence of Health Misinformation on Social Media: Systematic Review. J. Med. Internet Res. 2021, 23, e17187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Van Bavel, J.; Boggio, P.; Capraro, V.; Cichocka, A.; Cikara, M.; Crockett, M.; Crum, A.; Douglas, K.; Druckman, J.; Drury, J.; et al. Using social and behavioural science to support COVID-19 pandemic response. Nat. Hum. Behav. 2020, 460–471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Venkatesan, S.; Han, W.; Kisekka, V.; Sharman, R.; Kudumula, V.; Jaswal, H.S. Misinformation in Online Health Communities. In Proceedings of the Eighth Pre-ICIS Workshop on Information Security and Privacy, Milano, Italy, 14 December 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Chou, W.S.; Sciences, P.; Cancer, N.; Oh, A.; Sciences, P.; Cancer, N.; Klein, W.M.P.; Sciences, P.; Cancer, N. The Persistence and Peril of Misinformation. Am. Sci. 2017, 372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.J.; Cheung, C.M.; Shen, X.L.; Lee, M.K. Health Misinformation on Social Media: A Literature Review. In Proceedings of the 23rd Pacific Asia Conference on Information Systems: Secure ICT Platform for the 4th Industrial Revolution, PACIS, Xi’an, China, 8–12 July 2019; Volume 194. [Google Scholar]

- Coronavirus DISEASE (COVID-19) Pandemic. Available online: https://www.who.int/emergencies/diseases/novel-coronavirus-2019 (accessed on 20 March 2021).

- Munich Security Conference. Available online: https://www.who.int/director-general/speeches/detail/munich-security-conference (accessed on 20 February 2021).

- Fell, L. Trust and COVID-19: Implications for Interpersonal, Workplace, Institutional, and Information-Based Trust. Digit. Gov. Res. Pract. 2020, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bode, L.; Vraga, E. See Something, Say Something: Correction of Global Health Misinformation on Social Media. Health Commun. 2017, 33, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gu, R.; Li, M.X. Investigating the Psychological Mechanism of Individuals’ Health Misinformation Dissemination on Social Media. Available online: https://scholars.hkbu.edu.hk/en/publications/investigating-the-psychological-mechanism-of-individuals-health-m (accessed on 19 August 2021).

- Swire-Thompson, B.; Lazer, D. Public Health and Online Misinformation: Challenges and Recommendations. Annu. Rev. Public Health 2020, 41, 433–451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Ghenai, A. Health Misinformation in Search and Social Media. In Proceedings of the 40th International ACM SIGIR Conference on Research and Development in Information Retrieval (SIGIR’17), Tokyo, Japan, 7–11 August 2017; Association for Computing Machinery: New York, NY, USA, 2017; p. 1371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Khan, T.; Michalas, A.; Akhunzada, A. Fake news outbreak 2021: Can we stop the viral spread? J. Netw. Comput. Appl. 2021, 190, 103112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Apuke, O.D.; Omar, B. Social media affordances and information abundance: Enabling fake news sharing during the COVID-19 health crisis. Health Inform. J. 2021, 27, 14604582211021470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Southwell, B.; Niederdeppe, J.; Cappella, J.; Gaysynsky, A.; Kelley, D.; Oh, A.; Peterson, E.; Chou, W.Y. Misinformation as a Misunderstood Challenge to Public Health. Am. J. Prev. Med. 2019, 57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tasnim, S.; Hossain, M.M.; Mazumder, H. Impact of Rumors and Misinformation on COVID-19 in Social Media. J. Prev. Med. Public Health 2020, 53, 171–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Vraga, E.; Bode, L. Addressing COVID-19 Misinformation on Social Media Preemptively and Responsively. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 2021, 27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, X.; Zafarani, R. A Survey of Fake News: Fundamental Theories, Detection Methods, and Opportunities. ACM Comput. Surv. 2020, 53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Obiala, J.; Obiala, K.; Mańczak, M.; Owoc, J.; Olszewski, R. COVID-19 misinformation: Accuracy of articles about coronavirus prevention mostly shared on social media. Health Policy Technol. 2021, 10, 182–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Apuke, O.D.; Omar, B. Fake news and COVID-19: Modelling the predictors of fake news sharing among social media users. Telemat. Inform. 2021, 56, 101475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jonathan, G.M.; Jonathan, G.M. Exploring Social Media Use during a Public Health Emergency in Africa: The COVID-19 Pandemic. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/345877480_Exploring_Social_Media_Use_During_a_Public_Health_Emergency_in_Africa_The_COVID-19_Pandemic (accessed on 19 August 2021).

- Islam, A.N.; Laato, S.; Talukder, S.; Sutinen, E. Misinformation sharing and social media fatigue during COVID-19: An affordance and cognitive load perspective. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Chang. 2020, 159, 120201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bastani, P.; Bahrami, M. COVID-19 Related Misinformation on Social Media: A Qualitative Study from Iran (Preprint). J. Med. Internet Res. 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chakraborty, K.; Bhatia, S.; Bhattacharyya, S.; Platos, J.; Bag, R.; Hassanien, A.E. Sentiment Analysis of COVID-19 tweets by Deep Learning Classifiers—A study to show how popularity is affecting accuracy in social media. Appl. Soft Comput. 2020, 97, 106754. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pennycook, G.; McPhetres, J.; Zhang, Y.; Lu, J.G.; Rand, D.G. Fighting COVID-19 Misinformation on Social Media: Experimental Evidence for a Scalable Accuracy-Nudge Intervention. Psychol. Sci. 2020, 31, 770–780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mejova, Y.; Kalimeri, K. COVID-19 on Facebook Ads: Competing Agendas around a Public Health Crisis. In Proceedings of the 3rd ACM SIGCAS Conference on Computing and Sustainable Societies, Guayaquil, Ecuador, 15–17 June 2020; pp. 22–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dimitrov, D.; Baran, E.; Fafalios, P.; Yu, R.; Zhu, X.; Zloch, M.; Dietze, S. TweetsCOV19—A Knowledge Base of Semantically Annotated Tweets about the COVID-19 Pandemic. In Proceedings of the 29th ACM International Conference on Information & Knowledge Management (CIKM’20), Online, 19–23 October 2020; Association for Computing Machinery: New York, NY, USA, 2020; pp. 2991–2998. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aphiwongsophon, S.; Chongstitvatana, P. Identifying misinformation on Twitter with a support vector machine. Eng. Appl. Sci. Res. 2020, 47, 306–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deokate, S.B. Fake News Detection using Support Vector Machine learning Algorithm. Int. J. Res. Appl. Sci. Eng. Technol. (IJRASET) 2019. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/336465014_Fake_News_Detection_using_Support_Vector_Machine_learning_Algorithm (accessed on 19 August 2021).

- Ciprian-Gabriel, C.; Coca, G.; Iftene, A. Identifying Fake News on Twitter Using Naïve Bayes, Svm And Random Forest Distributed Algorithms. In Proceedings of the 13th Edition of the International Conference on Linguistic Resources and Tools for Processing Romanian Language (ConsILR-2018), Bucharest, Romania, 22–23 November 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Shmueli, G.; Bruce, P.C.; Gedeck, P.; Patel, N.R. Data Mining for Business Analytics: Concepts, Techniques and Applications in Python; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Kolbe, D.; Zhu, Q.; Pramanik, S. Efficient k-nearest neighbor searching in nonordered discrete data spaces. ACM Trans. Inf. Syst. (TOIS) 2010, 28, 1–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cunningham, P.; Delany, S.J. k-Nearest Neighbour Classifiers-A Tutorial. ACM Comput. Surv. (CSUR) 2021, 54, 1–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, M.; Jung, L.T.; Abdel-Aty, A.H.; Abubakar, M.Y.; Elhoseny, M.; Ali, I. Semantic-k-NN algorithm: An enhanced version of traditional k-NN algorithm. Expert Syst. Appl. 2020, 151, 113374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mokhtar, M.S.; Jusoh, Y.Y.; Admodisastro, N.; Pa, N.C.; Amruddin, A.Y. Fakebuster: Fake News Detection System Using Logistic Regression Technique In Machine Learning. Int. J. Eng. Adv. Technol. (IJEAT) 2019, 9, 2407–2410. [Google Scholar]

- Ogdol, J.M.G.; Samar, B.L.T.; Catarroja, C. Binary Logistic Regression based Classifier for Fake News. J. High. Educ. Res. Discip. 2018. Available online: http://www.nmsc.edu.ph/ojs/index.php/jherd/article/view/98 (accessed on 19 August 2021).

- Nada, F.; Khan, B.F.; Maryam, A.; Nooruz-Zuha; Ahmed, Z. Fake News Detection using Binary Logistic Regression. Int. Res. J. Eng. Technol. (IRJET) 2019, 8, 1705–1711. [Google Scholar]

- Bharti, P.; Bakshi, M.; Uthra, R. Fake News Detection Using Logistic Regression, Sentiment Analysis and Web Scraping. Int. J. Adv. Sci. Technol. 2020, 29, 1157–1167. [Google Scholar]

- Ghosh, A.; Sufian, A.; Sultana, F.; Chakrabarti, A.; De, D. Fundamental concepts of convolutional neural network. In Recent Trends and Advances in Artificial Intelligence and Internet of Things; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2020; pp. 519–567. [Google Scholar]

- Bai, L.; Yao, L.; Wang, X.; Kanhere, S.S.; Guo, B.; Yu, Z. Adversarial multi-view networks for activity recognition. Proc. ACM Interact. Mob. Wearable Ubiquitous Technol. 2020, 4, 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.; Yang, Y.t.; Hu, K.k.; Zheng, H.b.; Wang, Z. DAD-MCNN: DDoS attack detection via multi-channel CNN. In Proceedings of the 2019 11th International Conference on Machine Learning and Computing, Zhuhai, China, 22–24 February 2019; pp. 484–488. [Google Scholar]

- Bahdanau, D.; Cho, K.; Bengio, Y. Neural Machine Translation by Jointly Learning to Align and Translate. arXiv 2015, arXiv:abs/1409.0473. [Google Scholar]

- Ruchansky, N.; Seo, S.; Liu, Y. CSI: A Hybrid Deep Model for Fake News Detection. In Proceedings of the 2017 ACM on Conference on Information and Knowledge Management (CIKM’17), Singapore, 6–10 November 2017; Association for Computing Machinery: New York, NY, USA, 2017; pp. 797–806. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Cui, L.; Wang, S.; Lee, D. SAME: Sentiment-Aware Multi-Modal Embedding for Detecting Fake News. In Proceedings of the 2019 IEEE/ACM International Conference on Advances in Social Networks Analysis and Mining (ASONAM ’19), Vancouver, BC, Canada, 27–30 August 2019; Association for Computing Machinery: New York, NY, USA, 2019; pp. 41–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Z.; Yang, D.; Dyer, C.; He, X.; Smola, A.; Hovy, E. Hierarchical Attention Networks for Document Classification. In Proceedings of the 2016 Conference of the North American Chapter of the Association for Computational Linguistics: Human Language Technologies, San Diego, CA, USA, 12–17 June 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Cui, L.; Shu, K.; Wang, S.; Lee, D.; Liu, H. DEFEND: A System for Explainable Fake News Detection. In Proceedings of the 28th ACM International Conference on Information and Knowledge Management (CIKM ’19), Beijing, China, 3–7 November 2019; Association for Computing Machinery: New York, NY, USA, 2019; pp. 2961–2964. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, L.; Lee, D. CoAID: COVID-19 Healthcare Misinformation Dataset. arXiv 2020, arXiv:2006.00885. [Google Scholar]

- Jamison, A.; Broniatowski, D.A.; Smith, M.C.; Parikh, K.S.; Malik, A.; Dredze, M.; Quinn, S.C. Adapting and extending a typology to identify vaccine misinformation on twitter. Am. J. Public Health 2020, 110, S331–S339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hartwig, K.; Reuter, C. TrustyTweet: An Indicator-based Browser-Plugin to Assist Users in Dealing with Fake News on Twitter. In Proceedings of the WI 2019, the 14th International Conference on Business Informatics, AIS eLibrary, Siegen, Germany, 23–27 February 2019; pp. 1844–1855. Available online: https://aisel.aisnet.org/wi2019/specialtrack01/papers/5/ (accessed on 10 April 2021).

- Memon, S.A.; Carley, K.M. Characterizing COVID-19 Misinformation Communities Using a Novel Twitter Dataset. arXiv 2020, arXiv:2008.00791. [Google Scholar]

- Shahi, G.; Dirkson, A.; Majchrzak, T.A. An Exploratory Study of COVID-19 Misinformation on Twitter. Online Soc. Netw. Media 2020, 22, 100104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Singh, L.; Bansal, S.; Bode, L.; Budak, C.; Chi, G.; Kawintiranon, K.; Padden, C.; Vanarsdall, R.; Vraga, E.; Wang, Y. A first look at COVID-19 information and misinformation sharing on Twitter. arXiv 2020, arXiv:2003.13907. [Google Scholar]

- Alqurashi, S.; Hamawi, B.; Alashaikh, A.; Alhindi, A.; Alanazi, E. Eating Garlic Prevents COVID-19 Infection: Detecting Misinformation on the Arabic Content of Twitter. arXiv 2021, arXiv:2101.05626. [Google Scholar]

- Girgis, S.; Amer, E.; Gadallah, M. Deep Learning Algorithms for Detecting Fake News in Online Text. In Proceedings of the 2018 13th International Conference on Computer Engineering and Systems (ICCES), Cairo, Egypt, 18–19 December 2018; pp. 93–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hossain, T.; Logan IV, R.L.; Ugarte, A.; Matsubara, Y.; Young, S.; Singh, S. COVIDLies: Detecting COVID-19 Misinformation on Social Media. Available online: https://openreview.net/pdf?id=FCna-s-ZaIE (accessed on 19 August 2021).

- Shahi, G.K.; Nandini, D. FakeCovid—A Multilingual Cross-domain Fact Check News Dataset for COVID-19. In Proceedings of the 14th International AAAI Conference on Web and Social Media, Atlanta, GA, USA, 8–11 June 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, X.; Mulay, A.; Ferrara, E.; Zafarani, R. ReCOVery: A Multimodal Repository for COVID-19 News Credibility Research. In Proceedings of the 29th ACM International Conference on Information & Knowledge Management (CIKM 20), Turin, Italy, 22–26 October 2018; Association for Computing Machinery: New York, NY, USA, 2020; pp. 3205–3212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hossin, M.; Sulaiman, M.N. A Review on Evaluation Metrics for Data Classification Evaluations. Int. J. Data Min. Knowl. Manag. Process 2015, 5, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmad, I.; Yousaf, M.; Yousaf, S.; Ahmad, M.O. Fake News Detection Using Machine Learning Ensemble Methods. Complexity 2020, 2020, 8885861. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).