Abstract

Providing convenient and effective online education is important for the public to be better prepared for disaster events. Nonetheless, the effectiveness of such education is questionable due to the limited use of online tools and platforms, which also results in narrow community outreach. Correspondingly, understanding public perceptions of disaster education methods and experiences for the adoption of novel methods is critical, but this is an understudied area of research. The aim of this study is to understand public perceptions towards online disaster education practices for disaster preparedness and evaluate the effectiveness of the gamification method in increasing public awareness. This study utilizes social media analytics and conducts a gamification exercise. The analysis involved Twitter posts (n = 13,683) related to the 2019–2020 Australian bushfires, and surveyed participants (n = 52) before and after experiencing a gamified application—i.e., STOP Disasters! The results revealed that: (a) The public satisfaction level is relatively low for traditional bushfire disaster education methods; (b) The study participants’ satisfaction level is relatively high for an online gamified application used for disaster education; and (c) The use of virtual and augmented reality was found to be promising for increasing the appeal of gamified applications, along with using a blended traditional and gamified approach.

1. Introduction

Disasters are uncertain events that cause significant loss of life, damage property and infrastructure, and disrupt the regular community lifestyle [1,2]. The 2010 Haiti earthquake, 2012 Hurricane Sandy, 2013 European floods, 2013 typhoon Haiyan, 2017 Sierra Leone flood and landslides, and 2019 Australian bushfires are some of the devastating natural disasters that have taken place in the recent past. From 1998 to 2017, disaster-hit countries have reported a direct economic loss of around US $2.9 trillion [3]. Furthermore, over 1.3 million lives were lost, and over 4.4 billion people left injured, displaced, homeless or requiring assistance [3,4].

Such disaster-induced impacts could be mitigated by delivering a proper education to prepare for disasters, which is argued to be a ‘black hole’ in most disaster-related studies [4]. As disasters are uncertain in nature, delivering an appropriate education frequently to the community to prepare for disasters has become a pressing need. The Sendai Framework for Disaster Risk Reduction 2015–2030 identified the significance of strengthening public education and awareness to make people well prepared to face disasters [5]. With technological developments such as social media and online learning platforms, a multitude of new avenues have emerged to enhance disaster education [6,7,8]. Unfortunately, there is only limited research which looks at the need for upgrading disaster education through innovative and novel perspectives [4,9,10].

There are four modes of disaster education. These are: (a) formal education, (b) non-formal education, (c) informal education, and (d) incidental and random education [4]. Formal disaster education refers to the institutionalized and planned education delivered through a well-planned curriculum. Non-formal disaster education also relates to formal education, where institutionalized and planned education is delivered through extracurricular activities.

Informal education includes learnings from day-to-day activities. Mostly, this kind of informal education refers to community meetings and training and learning through social media. Incidental and random education refers to the forms of education methods which are not deliberately designed to deliver education. This includes education strategies such as learning through news broadcasts [4]. Nevertheless, both formal and non-formal education are the most popular forms of education which are delivered through workshops or in typical school settings [11].

Against this backdrop, the study aim was to identify public perceptions towards novel disaster education methods. Accordingly, this paper attempts to address two research questions. The first research question was ‘How do the public perceive novel disaster education methods?’ To address this issue, the study first evaluated community perceptions about the prevailing disaster education methods through a Twitter data analysis. The second research question was ‘How effective is the use of the gamification method in increasing public awareness?’. The study addressed this research question by taking into consideration the 2019–2020 Australian Black Summer bushfires as the case study and ‘STOP Disasters’ as the gamified application to evaluate the awareness changes in a group of 52 university students. In line with these two research questions, the study adopted and tested the hypothesis ‘Gamified applications related to disasters are efficient modes for increasing community disaster awareness’.

A study by [12] classified 35 gamified applications related to disasters into three classes based on their objectives—gamified applications that collect data for research [13,14,15,16,17]; gamified applications that aim to increase disaster education among people [13,18,19,20], and gamified applications that try to intervene in existing practices [21,22,23]. Nevertheless, none of the studies have tried to understand the effectiveness of using gamified applications such as that on which this study is based. The findings of this study contribute to an understanding of the effectiveness of using gamified applications—an approach of using game-like elements in non-game contexts—as a novel and innovative approach to be used in future disaster education practices.

2. Literature Background

2.1. Traditional Disaster Education Methods

Disaster education programs which rely on the provision of generic information and preparedness plans/templates are categorized as traditional methods used for disaster education [9,24,25]. Most of the traditional methods of disaster education include formal and non-formal methods of education. These education approaches are intended to empower people through meetings conducted on a regular basis, focus group discussions, stakeholder meetings, workshops, trainings, or curriculum-based learning methods [26,27]. As disasters become severe and frequent due to climate change impacts, such time- and space-consuming methods become inadequate to make people well prepared for disasters [28,29].

Knowledge often flows from professionals to the community through traditional methods of disaster education. Therefore, in traditional methods of disaster education, knowledge flows without adequate community engagement [30]. Besides this, incorporating community knowledge in disaster-related decision-making processes through face-to-face participatory methods could be costly and time-consuming [27,31].

Further to [4], education, communication, and engagement all need to be equally strengthened to create a good disaster education system. Nonetheless, this requirement cannot be fully achieved with traditional forms of disaster education methods. Traditional media of education also include educating people through distributing handouts, documentaries, and newspaper articles. Consequently, these create one-way communication and do not provide adequate opportunity for community interaction. While appreciating the existence and the role of so-called traditional modes in disaster education, this study emphasizes the need for integrating novel and innovative methods for convergence in disaster education methods, while making the presence of education–communication–engagement frequent [32,33,34,35].

2.2. Contemporary Disaster Education Methods

Practices which are influenced and inspired by new technologies are considered as contemporary methods. These include methods such as social media, gamifications, conducting video tutorials, and virtual demonstrations [3,36]. Most significantly, these methods can be used strongly, cost effectively, and flexibly to increase the education–communication–engagement nexus [3,4,36]. Due to this, informal and incidental education is becoming more popular.

As argued by [36,37], social media is a significant tool to create collective intelligence by sharing and educating through time-critical information. The information and awareness raised through social media platforms bridges the information gaps between communities [23,38,39]. With the prolific use of social media, most of the authorized emergency management services use Facebook, Twitter, and Instagram to conduct disaster awareness campaigns, update disaster conditions, conduct online polls to test disaster-related knowledge, launch fundraising campaigns, and so on [24].

For instance, during the Sydney storm in March 2020, New South Wales State Emergency Services (NSW SES) requested people post the photos of their observations to the NSW SES Facebook page. Furthermore, the posts shared on social media pages related to disasters had high engagement and were shared to personal social media pages by people during times of disaster to increase awareness [24]. Factually, social media create strong social networks, where information flows in every direction. This could be information received from authorities, personal opinions, or eyewitness information. The historic evidence also confirmed that an unusual peak of social media around a particular topic undoubtably delivers authorities an informal warning about a possible disaster [24,40].

Gamification or the use of game-like elements in non-game, real-world contexts such as disasters is one of the emerging methods used for disaster education in recent times [41,42,43] For instance, [24] identified 35 gamified applications used in disaster-related contexts. From them, around 50% (n = 18) of gamified applications such as STOP Disasters, We Share IT, Levee Patroller, Dissolving Disasters, and Disaster Detector are used for educational purposes [44]. These applications provide disaster education to people in three forms.

The first group of gamified applications provide education and training about reading and understanding scientific instruments such as thermometers and seismometers—e.g., Disaster Detector. The second group of gamified applications challenge the players to survive in disasters created in virtual environments—e.g., In a SAFE, DRED-Ed [45,46]. The third group of gamified applications let the player play by preparing cities and neighbourhoods for upcoming disasters—e.g., STOP Disasters [26,47,48,49,50,51,52,53].

All these gamified applications are driven by two types of motivations. These are: (a) intrinsic motivation and (b) extrinsic motivation [54,55]. Intrinsic motivation refers to the player satisfaction received by playing the game. Such intrinsic motivation could be the satisfaction received through learning something new, enjoying the game, curiosity, or a feeling of happiness [33,51,52]. Extrinsic motivation refers to community engagements due to collecting rewards and increasing scores. In general, gamified applications try to deliver education to the participants through both intrinsic and extrinsic motivations [53].

Video tutorials and virtual demonstrations have also become popular due to the high use of technical instruments such as drones, CCTV cameras, and mobile applications [12,56]. These are also used in social media platforms such as Facebook, Twitter, Instagram, and YouTube. These video demonstrations provide instructions and information to people based on previous disaster events and try to highlight the lessons people can learn from them [35]. Furthermore, these act as cost- and time-saving methods while making education–communication–engagement more frequent and effective [4].

While the literature highlights the importance of gamification in increasing awareness, there is only a limited number of studies that evaluate the level of awareness created through gamification [57,58]. To bridge this gap in the literature, the study has identified the need for testing the following hypothesis: Gamified applications related to disasters are efficient modes for increasing community disaster awareness. The methodological approach to such testing is presented in the following research design section.

3. Research Design

3.1. Case Study

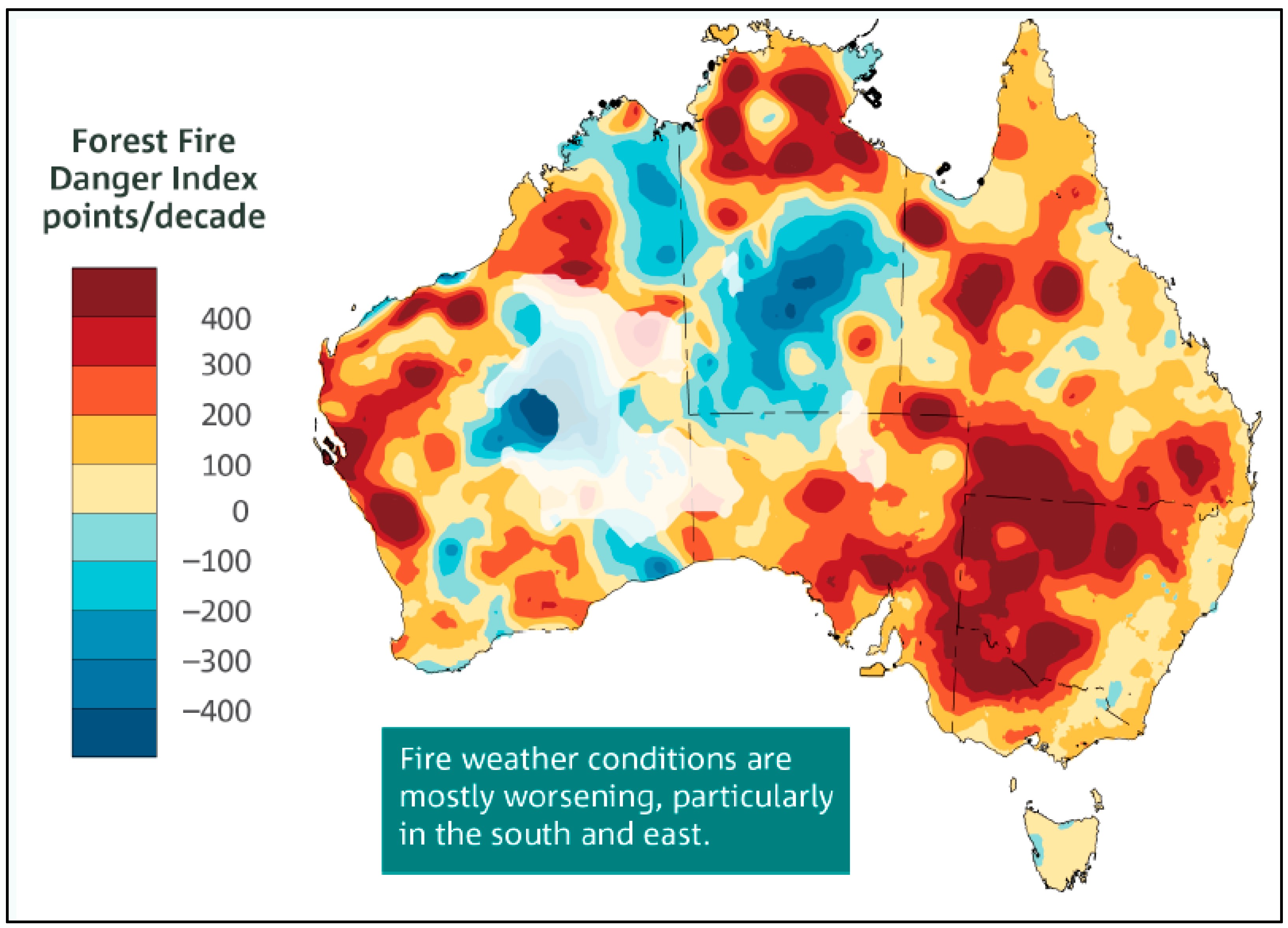

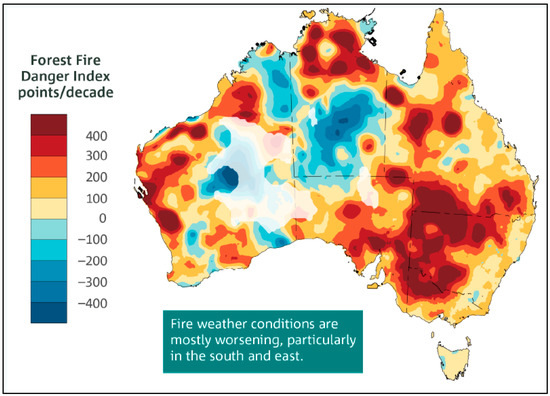

Australia is not a stranger to bushfires [53]. Additionally, this is one of the most common disaster types for Australia. Figure 1 shows the trend in the annual sum of the Forest Fire Danger Index (FDI) [9]. It shows an increase in the FDI in recent decades. The Gippsland fires and Black Sunday of 1926 (Victoria; 60 fatalities), Black Tuesday bushfire of 1967 (Tasmania; 62 fatalities), Black Friday of 1939 (Victoria; 71 fatalities), Ash Wednesday of 1983 (South Australia; 75 fatalities), Black Saturday bushfire of 2009 (Victoria; 173 fatalities) and Black Summer bushfire of 2019–2020 are amongst the most disastrous bushfire events that have taken place in Australian history [59,60].

Figure 1.

Trend in the annual sum of Forest Fire Danger Index, 1978–2017 [61].

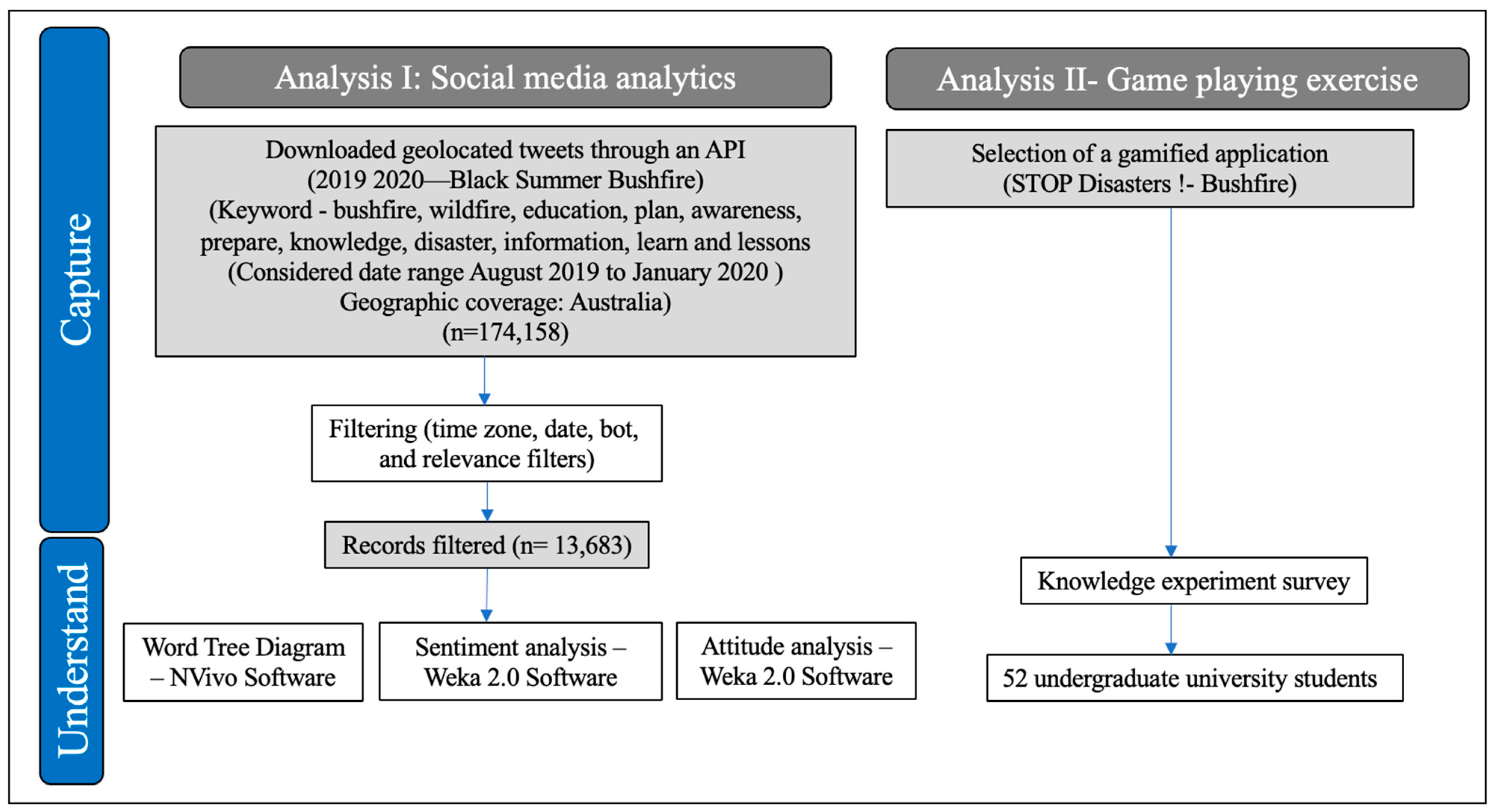

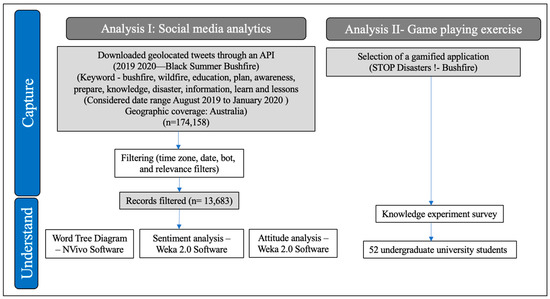

Due to the Black Summer bushfires of 2019–2020, 2448 homes burned down, and the fires destroyed 284 facilities, 5469 outbuildings, and damaged 1013 other homes. The majority of this damage occurred in southern NSW. As per the assessments by the Rural Fire Service, it was estimated that 14,519 homes, 1486 facilities, and 14,016 outbuildings were saved through firefighting protective measures. Furthermore, the fire had a major impact on the agricultural community. The fire killed or displaced over three billion animals, and over one billion of them were in NSW [29]. The Black Summer bushfires of 2019–2020 are considered one the most severe disaster events in Australia in recent years [61]. Figure 2 shows the methodological framework adopted throughout the study.

Figure 2.

Overall methodological framework.

3.2. Social Media Analytics

Social media data are increasingly used in disaster-related research [36,62,63,64] due to the advantages of data availability and flexibility in data collection. Therefore, as the first methodological approach, this study analysed social media data to understand community perceptions about the prevailing bushfire disaster education.

Among many social media platforms, Twitter data were used in the analysis undertaken due to the following reasons: (a) Twitter has become the fastest growing social media platform since its beginning in 2006; (b) Twitter offers application programming interface (API) access to researchers and practitioners to conduct studies based on their interests [65]; (c) Compared to Facebook and Instagram, Twitter data are considered ‘open data’, which provides succinct real-time data to the public [66]; and (d) Searching and streaming the APIs of Twitter permits researchers to write queries and download data based on specific keywords.

Accordingly, Twitter messages circulated from August 2019 to January 2020—during the Australian Black Summer bushfires—with the keywords of bushfire, education, plan, awareness, prepare, knowledge, disaster, information, learn, and lessons were downloaded. In total, 174,158 tweets were downloaded. Following this, the five-step data cleaning process introduced by [4] was adopted—time zone filter, date filter, bot filter, relevance filter, and text filter to clean the data. Text filtering was done at the time the data were downloaded through a Twitter API using a set of keywords. Among them, the first two filtering steps—the time zone filter and date filter—were completed at the time the data were downloaded. The other two filtering steps—the bot filter (removal of automated messages) and relevance filter (removal of irrelevant meanings)—were applied later. All the filtering was conducted using a Python programming software and a macro-enabled Excel sheet. Consequently, 13,683 tweets were identified as being relevant to the research theme.

The cleaned data were analysed in four stages to identify community perceptions about the prevailing bushfire education in Australia. Firstly, a word-tree diagram was created using NVivo software to understand the main perception clusters existing around the words which are synonyms for education. A word-tree diagram provides an opportunity for the reader to study the ways that a particular word or phrase is used in a text or a particular context. It further expresses broad patterns of word clusters [67]. Accordingly, a word-tree diagram created for the term ‘education’ and related words will show all instances of education and its synonyms within the tweets circulated during the 2019 Australian bushfires.

Secondly, a sentiment analysis was conducted to identify the emotions of the community related to bushfire disaster education. All the tweets were categorized into four emotional categories from strong positive emotions to strong negative emotions. Thirdly, word-cloud analysis was conducted to identify the keywords in each emotional category. Finally, based on the word-cloud analysis, the main attitudes in each emotional category were derived.

3.3. Gamification in Practice

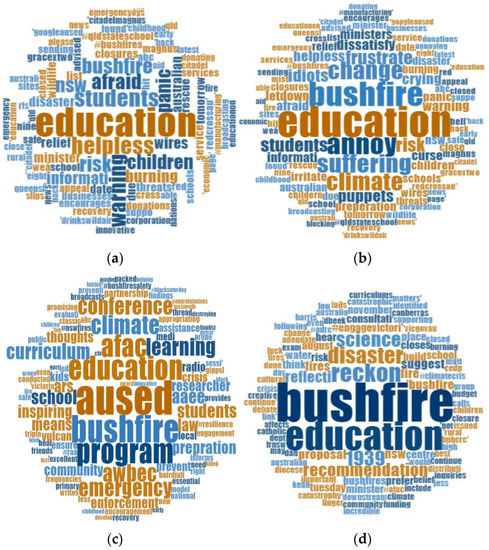

Following the literature [68,69] on the gamification approach being an effective alternative to the conventional approach in training, as a second methodological approach, the study evaluated the possibility of using a gamified application to increase community disaster education. For that, a gamified application called ‘STOP Disasters’ was used. This game is an artificial intelligence (AI) based gamified application, which is intended to increase education related to bushfire disasters while allowing the players to enjoy the game [70,71]. This game was selected for this study since it enables players to experience disasters in a virtual environment, by understanding the potential risks while applying effective methods of prevention and mitigation. The player’s task is to plan and construct a safe environment for people and assess the disaster risks while attempting to withstand the damage when natural disasters occur.

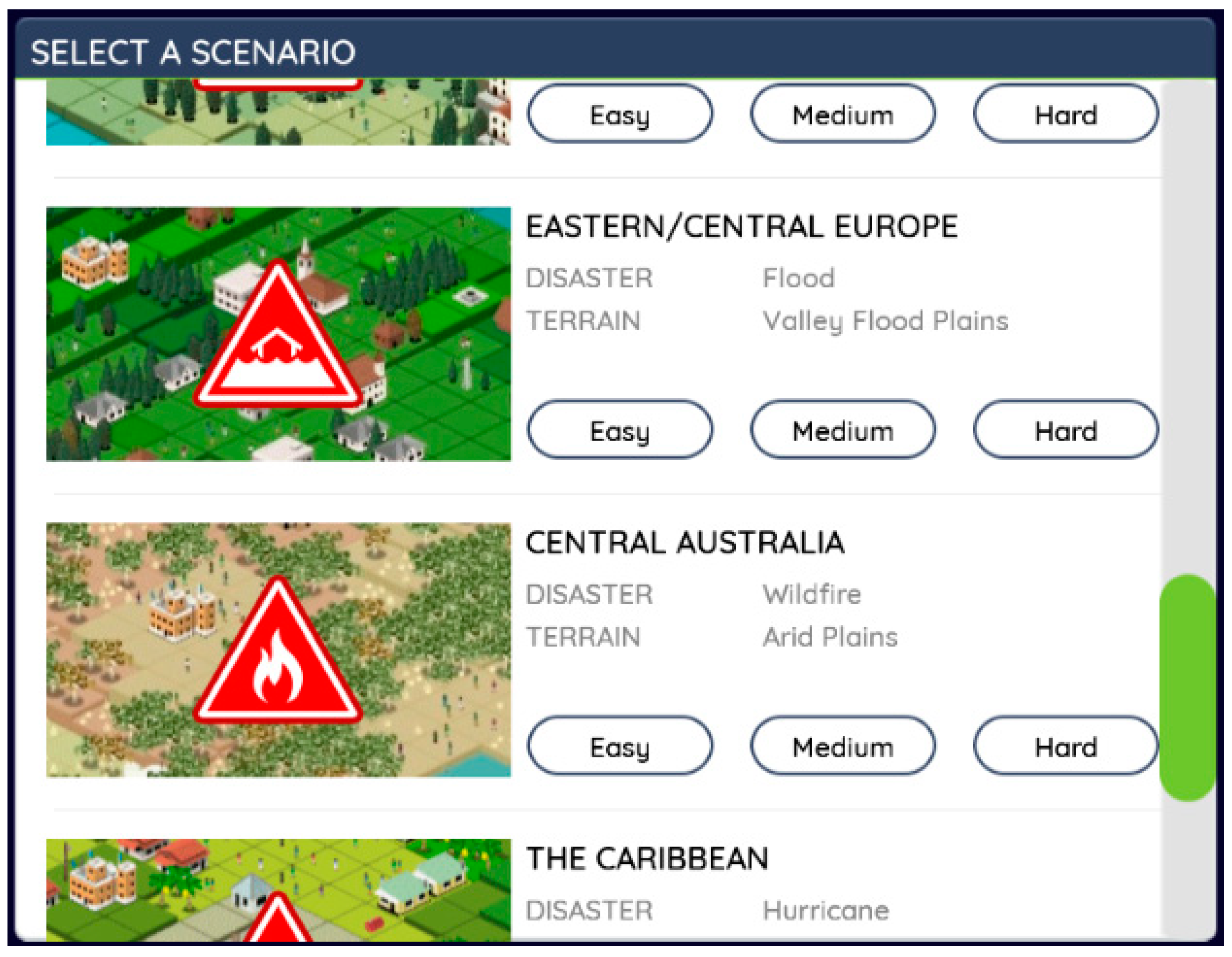

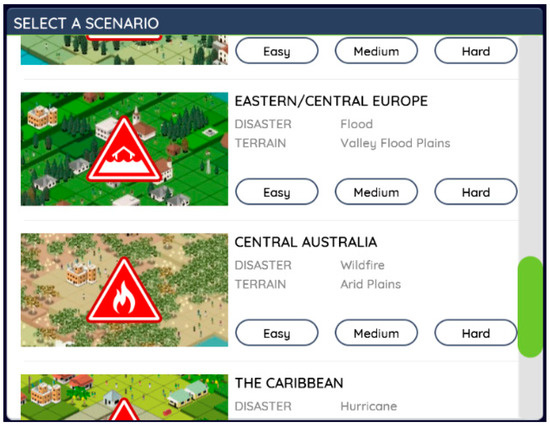

‘STOP Disasters’ is a video game developed by the United Nations Office for Disaster Risk Reduction (UNDRR). At the time of writing, the STOP Disasters gamified application can be played with five disaster scenarios. These are as follows: bushfire, tsunami, hurricane, earthquake, and flood. As given in Figure 3, the game for the bushfire scenario considers Australia as the exemplar case study. Considering these facts, the STOP Disaster gamified application for bushfires in Australia was selected for this study. The game tries to increase player knowledge on four topics related to bushfires. These are: (a) vacant land management, (b) inhabited land management, (c) building material management, and (d) community management [72].

Figure 3.

Use of Central Australia as a case for the bushfire gaming scenario.

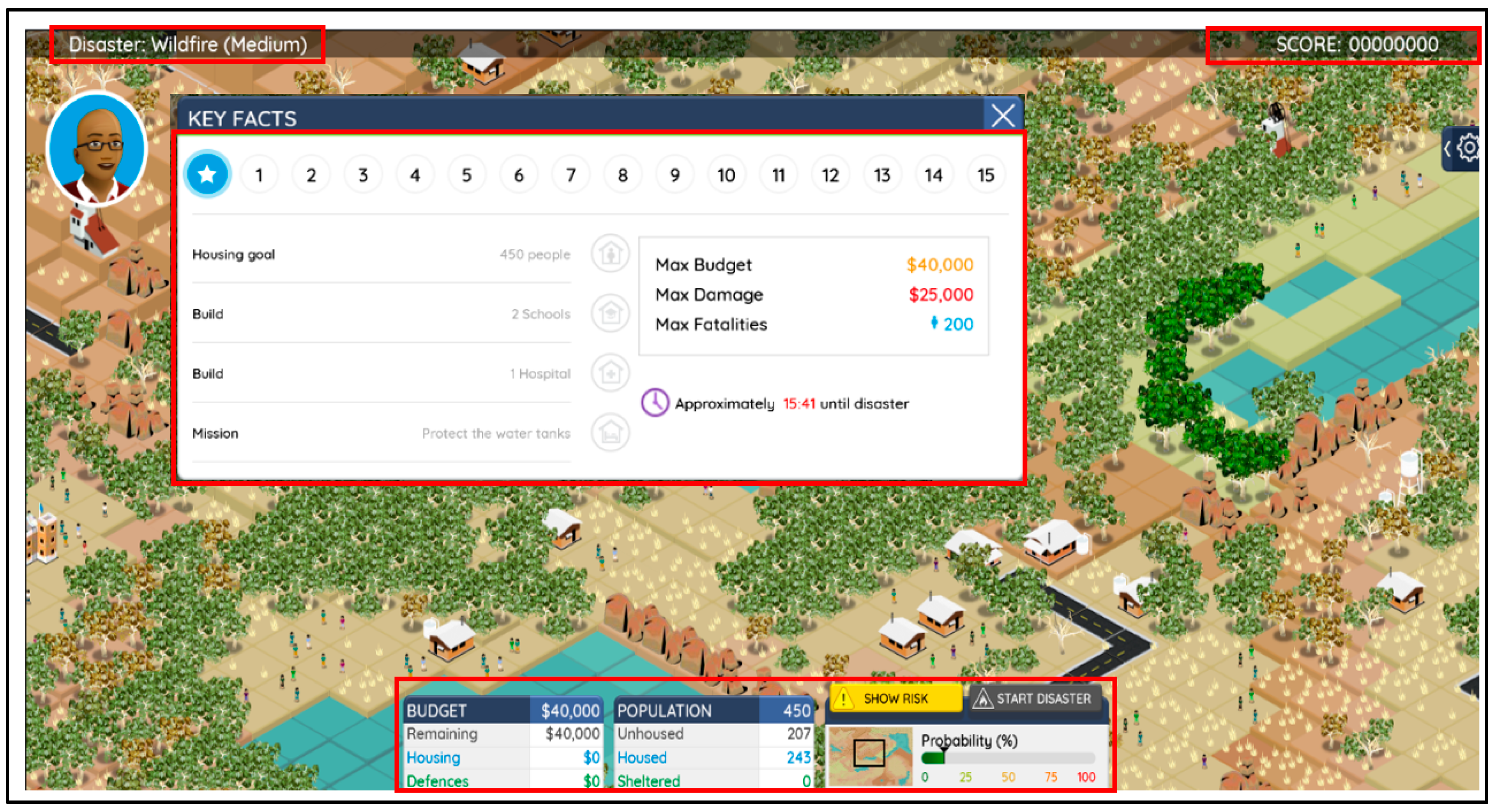

As in Figure 4, this game provides an isometric view of a small settlement and provides the player with the task of planning a settlement using a fixed budget within a limited time. At the end of the given time, a bushfire will take place and burn all the unplanned areas, where disaster risk could be high. This gamified application consists of extrinsic motivational elements such as earning points, unlocking key facts, planning the settlements, and managing the budget. However, how effective are they in increasing the players’ bushfire-related education needs to be investigated through a systematic survey.

Figure 4.

Overview of the gaming platform.

3.4. Survey Design

The main purpose of the survey was to understand the participants’ perspectives on using this novel method—i.e., gamification—to increase disaster education. Accordingly, 52 undergraduate university students of ages ranging between 18 and 22 from Brisbane, Australia, were surveyed during April 2020. The surveyed group was selected as they are familiar with new technologies and devices. However, future research could evaluate the applicability of using gamification across different age groups.

The survey was held in three stages. In the first stage, the participants were given a questionnaire to test their existing knowledge about the bushfires. Secondly, the participants were asked to play the STOP Disaster game. Thirdly, the participants were given the same questionnaire (given in Stage 1) and asked to answer to the questions. Finally, the answers provided before and after playing the game were comparatively analysed to understand the effectiveness of using gamified applications to increase disaster education.

4. Results

The study consisted of two parts: (a) Part 1: Public perception survey on bushfire education using Twitter data analytics, and (b) Part II: Survey on using gamified applications for disaster education. The Twitter analytics emphasized the community demand for new approaches to increase disaster education. The public highlighted especially the need to upgrade the traditional education methods integrated with new approaches to increase the efficiency of prevailing methods. As a new approach, this study evaluated the usability of gamified applications to increase efficiency in disaster education. As the study findings revealed, gamification is an ideal tool to be used together with traditional disaster education approaches which could lead to increased community engagement and knowledge.

4.1. Public Perceptions on Bushfire Disaster Education

4.1.1. Perception Clusters

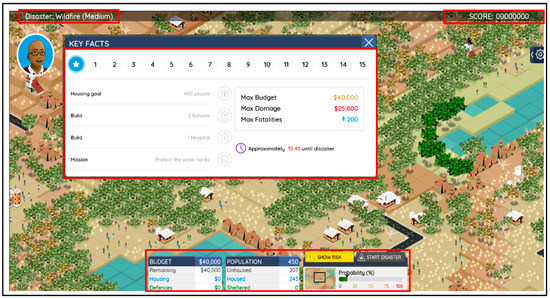

From all the tweets downloaded related to bushfires (n = 174,158), only 8% (n = 13,683) of the tweets talked about the importance of bushfire education. Based on these tweets, a word-tree diagram was generated to identify the main perception clusters existing around the word ‘education’ or related synonyms such as ‘learn/study’. The word ‘bushfire’ was considered a stop word due to its high occurrence. Accordingly, seven main clusters were identified (Figure 5).

Figure 5.

Word-tree diagram.

The first word cluster was about the words related to education and policy. This cluster has three branches. The first and the main branch of the diagram was related to education and policy. It talks about the significance of policy-level attention to bushfire education. Further, the role and the contribution of Australian Association Environmental Education ACT (AAEE ACT), and Social and Citizenship Education Association of Australia (SCEA) in bushfire situations were questioned and discussed in many tweets as given in Table 1. AAEE ACT is a non-profit Australian organization that acts as a peak professional body for environmental educators [1]. SCEA is an organization that undertakes teaching and research in social citizenship education across all types and levels of education institutions [53]. The second branch was created around the words related to education, policy, and innovation. Tweets related to this category were about research and development work. Besides this, this category emphasized the need to employ student-centred approaches to increase disaster education.

Table 1.

Exemplar tweets for each branch of the word tree.

The third branch was developed around the words ‘education’, ‘policy’, and ‘evaluation’. This branch had tweets related to the disaster-mitigation measures of the Victorian Curriculum and Assessment Authority. This authority is responsible for the provision of the curriculum and assessment programs for students in the State of Victoria. The tweets from this category highlighted the importance of expanding bushfire education among the students related to bushfire history, prevention and mitigation measures, preparedness and disaster response methods, and so on.

The second cluster was about words related to education and programs related to bushfires. The tweets in this category talked about facts such as the need for a national-level program for bushfire mitigation and fire prevention and emergency broadcasts. The third word cluster was related to words connected to education and disasters. Important topics such as educating people about bushfire disaster survival and why bushfire disaster education matters were discussed in many tweets in this category.

The fourth cluster was related to education and crisis. The negative impacts of bushfires, the importance of saving endangered animals, the role of education minister, fighting for resources during a bushfire crisis, and the impact of geographic locations on bushfires were the central topics in these tweets. The fifth cluster was about collaborations. The importance of having more intellectual discussions about and intellectual insights into bushfire education were the main concerns among the tweets from this cluster. For instance, tweets from this cluster paid attention to the role of leading organizations and conferences in Australia such as the role of the International Education Association of Australia (IEA Australia), which is a cross-sectoral organization in Australia which represents the country’s education; the Australasian Fire Authorities Council (AFAC) conference, which is Australasia’s largest emergency management conference and exhibition; and the Ash Wednesday Bushfire Education Centre (AWBEC) [73].

The sixth cluster is about education and knowledge-sharing related to bushfires. This cluster has two branches. The first branch is education, knowledge, and communities. The tweets with these words discussed the significance of promoting local capacities, easing family recovery efforts, and resilience. The second subbranch under the sixth word cluster was about volunteer heritage. Tweets related to this branch talked about the establishment of a world-leading bushfire volunteers’ heritage and education centre.

The last cluster is about teaching and learning resources. Tweets with these words shared information related to law enforcement, climate change and bushfires, air quality and bushfires, the need for a curriculum change, and the need to change conventional bushfire education. All these seven clusters showed how insightful the community is about education related to bushfires.

4.1.2. Sentiments and Attitudes

When sharing community perceptions through tweets, people also share their emotions. Accordingly, an emotional or sentiment value was derived for each tweet by training the dataset using the Random Tree data classification method using Weka 2.0 software. The data were trained using two-word bags which contained negative and positive words. A sample of words used for data training is given Table 2. Due to the high frequency of words such as ‘bushfire’ and ‘disaster’ used in the tweets, they were avoided in preparing the word bags. Using the word bags, all the tweets were categorized under four parameters starting from strongly negative to strongly positive.

Table 2.

A sample of word bags for sentiment analysis.

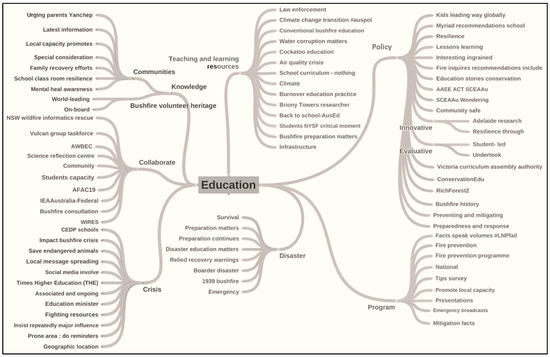

From the analysed tweets, 18% were strongly negative, 31% were negative, 30% were positive, and 16% were strongly positive. In total, 49% of the tweets were negatively classified and 46% positively classified, whilst 5% were neutral. Figure 6a–d shows the word-cloud analysis for each emotional category.

Figure 6.

(a) Negative sentiments; (b) Strongly negative sentiments; (c) Strongly positive sentiments; (d) Positive sentiments.

As given in Figure 6a,b, words such as ‘helpless’, ‘services’, ‘panic’, ‘economic’, ‘students’, ‘minister’, ‘services’, ‘risk’, and ‘information’ were plural among the negatively classified tweets. Further, words such as ‘annoy’, ‘suffering’, ‘risk’, ‘frustrate’, and ‘preparation’ were prominent in the strongly negative word cloud. This reflected the negative emotions people had in relation to the prevailing disaster education and preparation methods.

The presence of institutional names such as AWBEC and AAEE in the word cloud for strongly positive tweets (Figure 6c,d) reflected the positive sentiments of the community related to such institutions. Additionally, conferences such as ADRC (Australian Disaster Resilience Conference) 2019 and AFAC and words such as ‘engagement’, ‘science’, and ‘consultation’ were plural among the positively classified tweets. As [4] mentions, conducting education-centre-based knowledge development is a traditional form of education, and people have seen this service in a positive light. Nonetheless, for an in-depth understanding, the tweets under the four sentiment groups (n = 13,022) were further classified based on six attitudes (Table 3).

Table 3.

A sample of word bags used for attitude analysis.

Hence, another six attitude words groups were derived after closely observing the word clouds and the tweets of each sentiment category. Fear, anger, and frustration were the main attitudes derived from the negatively classified tweets. Motivation, appreciation, and recommendation were the main attitudes derived from the positively classified tweets. As given in Table 3, another six-word bag set was separately developed to train the dataset again, to classify tweets under the six aforementioned attitude groups using Weka 2.0 software.

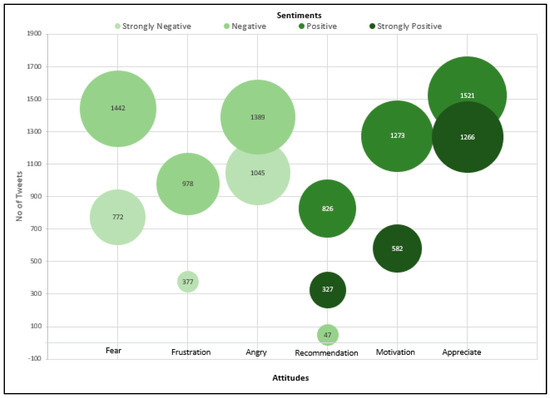

As given in Figure 7, 11% (n = 1442) of the total tweets expressed fear with a strong negative emotion. About 6% (n = 772) of the tweets expressed fear with a negative emotion. Most of the tweets from this category expressed a fear of the prevailing bushfire while requesting more information and evacuation instructions. Around 7% (n = 978) of the tweets expressed a frustrated attitude with strongly negative feelings. About 3% (n = 377) of the tweets had disappointed attitudes with a negative emotional perspective. Most of the tweets from this group tried to factually criticize the bushfire situation in Australia, taking historical bushfire events as examples (Table 4). The major criticism was not learning from Indigenous knowledge in responding to bushfires. Nearly 10% (n = 1389) were classified as tweets with angry attitudes that expressed a strongly negative attitude. Around 8% (n = 1045) of the tweets had angry attitudes with a negative emotional perspective. As in Table 4, most of the tweets from this category criticized some of the policy movements and actions taken by authorities.

Figure 7.

Distribution of tweets by sentiments and attitude clusters.

Table 4.

Example tweets by sentiments and attitudes.

About 6% (n = 826) of the total tweets were classified as tweets with strongly positive recommendations. Around 2% (n = 327) of the tweets which provided recommendations were positively classified. These tweets provided recommendations to enhance bushfire education. Although the attitude of recommendation was derived initially from the positively classified tweets, a small number (n = 47) of negatively classified tweets were also categorized as recommendations. Such tweets have tried to provide suggestions while criticizing the prevailing government responses to bushfire. About 9% (n = 1273) of positively classified tweets and 4% (582) of strongly positive tweets accordingly had motivational attitudes. As given in Table 4, 11% (n = 1521) of positively classified tweets and 9% (n = 1266) of strong positive tweets had appreciative comments. Further, 13% (n = 1838) of tweets were not categorized under any of the attitudes derived above.

All these attitudes and sentiments reflected the community interest in increasing bushfire disaster education among the younger generation as well as adults. Additionally, the tweets that were analysed expressed more appreciative and evaluative comments related to innovative and novel approaches to expanding bushfire disaster education.

4.2. Survey Participants Perspectives on Gamified Bushfire Disaster Education

4.2.1. Perceptions on Gamification

As a novel and emerging technique to increase disaster education, this study evaluated gamified applications through the STOP Disaster online video game. Accordingly, as given in Table 5, 52 undergraduate students’ knowledge was tested under four themes.

Table 5.

Survey responses.

The first theme is about vacant land management. According to the above statistics, only 40% and 60% of the students answered the first and second questions correctly before playing the game. However, the number of students who answered the same questions accurately increased by 50% and 27%, respectively, after playing the game. The second set of questions evaluated student knowledge about managing inhabited land. On average, most of the students answered to this set of questions correctly in the first round before playing the game. However, after paying the game, the number of students who answered the same questions accurately increased by 10% and 9%, respectively. This category had four questions as the game delivered significant knowledge related to building material management in bushfires. As shown in Table 5, only 38% and 58% of students answered the first two questions correctly in this category. However, after playing the game this number increased significantly, by 33% and 32%, respectively.

The third set of questions were about building material management to make the environment bushfire resilient. Even in the first round, all the students answered the first question in this category correctly. Furthermore, 87% and 65% of students answered the last two questions in this category correctly. After playing the game, these numbers increased by 3% and 10%, respectively.

The last set of questions were to examine knowledge about community engagement related to bushfire. According to the responses shown in Table 5, 52% and 42% of students answered the questions correctly and amount increased by 29% and 37%, respectively, after playing the game. Factually, playing the game increased the students’ knowledge related to bushfires. Further, the questionnaire examined the intrinsic and extrinsic motivational elements which motivated the students to gain knowledge while enjoying the game.

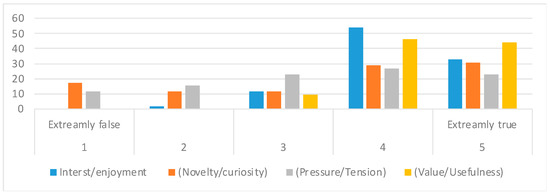

As shown in Figure 8, 54% of the students found the game was interesting and enjoyable and 33% of students found it extremely enjoyable, while only 2% found it not to be enjoyable. However, none of the students rated the game as extremely unenjoyable. Furthermore, 31% of the students confirmed that they gained new knowledge while playing the STOP Disasters game and that it was extremely motivational. Additionally, 23% of students ranked the game as a curious game to explore. Most significantly, 90% of students either found the game useful or extremely useful.

Figure 8.

Intrinsic motivations of STOP Disaster gamified application.

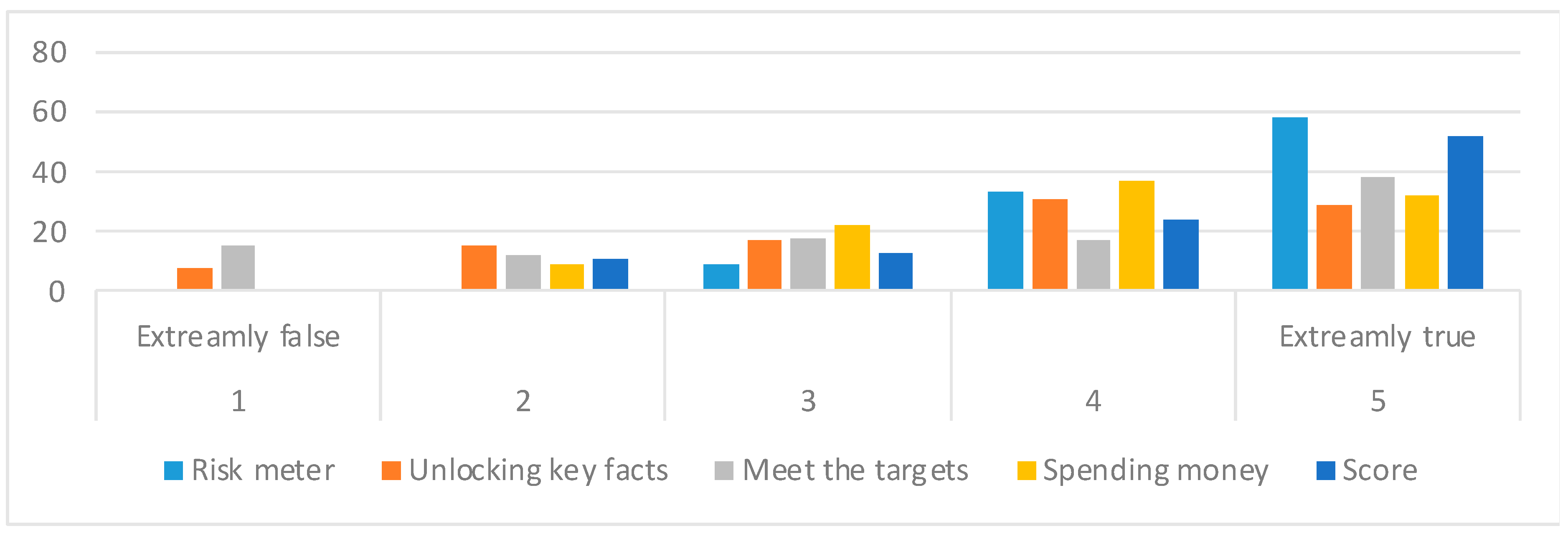

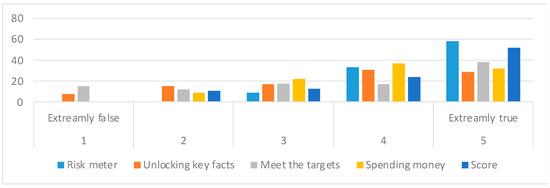

Gamified applications are driven by both intrinsic and extrinsic motivations. As given in Figure 9, the STOP Disasters game attracted the students’ attention through five main gaming elements These are: the risk meter, unlocking key facts, meeting the given targets, spending the allocated budget, and the score. Furthermore, 58% of the students were extremely motivated to engage in the game due to the risk meter. The risk meter increases over time, where the player needs to plan the settlement in a resilient way before the bushfire takes place.

Figure 9.

Extrinsic motivations of STOP Disasters gamified application.

Additionally, 60% of the students were either extremely motivated or motivated to play the game due to the unlocking of key facts. These key facts provided guidance to the players to play the game but are unlocked based on the performance of the player. In summary, 55% of the players were extremely motivated or motivated to achieve the given targets. Further, 69% and 76% of the students ranked spending money and collecting scores, respectively, as extrinsic motivational elements which encouraged them to play the game.

4.2.2. Means to Improve Effectiveness

At the end of the questionnaire, students were given an open-ended questionnaire to comment about using game-like elements in non-game contexts and to suggest new means to improve this approach. The comments can be categorized into two groups. These were: (a) Use of other technologies such as artificial intelligence (AI), augmented reality (AR), or virtual reality (VR) to enhance the game environment; and (b) Having another partner to play the game with online to make the game more competitive.

AR technologies integrate the visual and audio content of the game with the user’s environment in real-time [74]. Although this could be a good way to learn, further research needs to be done in this context, as this study is referring to a disaster situation. Additionally, there were student suggestions to play this kind of game using VR technology. Unlike AR technologies, VR requires additional facilities such as a separate room or confined area to create an immersive environment [75]. AI serves as the backbone of both AR and VR technologies. Hence these suggestions made by the students merit further investigations.

The second suggestion was to make the gamified application more competitive by introducing a competitor/s to play the game. The main intention of a gamified application is to increase player knowledge while making the learning environment more enjoyable. This objective could be well achieved by introducing another player to the gaming platform. Although the gamified application of STOP Disasters! does not have this ability, some of the other gamified applications for disasters such as Pokémon GO and Disaster in My Backyard [44] allow many players to compete in the gaming platform while they learn.

5. Discussion

5.1. How Do the Public Perceive Traditional Methods in Disaster Education Practices?

With the proliferation of social media and other related technical devices, humans have become the main sensor of the environment [76,77] Earlier people sensed the environment, but they did not have enough modes and media to express and share the environmental changes and the local knowledge attached to it [78,79]. In contrast, now people are equipped with different devices such as mobile phones, mobile applications, and media such as different social media platforms to express their feelings and observations [80,81,82].

The plurality of such devices and media encourages people to express their perceptions [14]. As identified in this study, people use social media to express their opinions openly. Moreover, the contents of the Twitter messages helped to understand how people have perceived a particular issue. According to the tweets analysed, people have perceived the traditional forms of education from both positive and negative perspectives.

For instance, people appreciate the services provided through information centres (AWBEC) and policy documents. However, they were also critical about such educational methods for not giving priority to important topics (Table 6). Factually, people tend to accept the traditional methods, but most importantly, they had their own suggestions to improve these methods.

Table 6.

Main attitudes expressed related to traditional disaster education methods.

The study findings also highlighted the significance of the existence of traditional educational methods, while harmonizing with emerging new technologies and methods, i.e., the use of social media campaigns and new technologies to give more prominence to Indigenous knowledge for reducing bushfire risk. The IMD’s World Digital Competitiveness Ranking annually evaluates the extent to which a country implements and explores digital technologies [83,84]. Inarguably, incorporating new technologies with traditional methods of disaster education practice is highly important for countries with a focus on making their cities smart [10,85,86,87].

According to the World Digital Competitiveness rankings [83], countries such as the USA, Singapore, Sweden, Denmark, Switzerland, and Australia are within the top 30 countries who use technologies in government services, business activities, and society in general. Further, developing countries such as Jordan and Thailand are in the second top quarter of the countries which are ranked between 31 and 60 [83]. Thus, as suggested in the tweets, incorporating novel technologies with traditional methods is a possible and worthy strategy for both developed and developing countries. This will further increase the efficacy of traditional methods [88,89].

5.2. How Effective Is the Gamification Method in Disaster Education?

As highlighted by the tweets, the community has used social media as a technology to share and discuss informative topics related to disasters. Besides, they suggested the importance of using novel and innovative methods to increase disaster education among children and adults to add more value to the traditional methods.

Nevertheless, none of the tweets have discussed using gamification as a tool to increase disaster education, although this has been used in many countries such as the UK, the US, and Japan to solve disaster-related issues such as: (a) Disaster education—i.e., Stop Disasters!, We Share It, Levee Patroller [24,44]; (b) Research (data collection/survey)—i.e., FloodSim, SimFlood, SerGIS, Millbrook Council Serious Game; and (c) Altering community practices through gamified applications for interventions—i.e., Flood-Wise, I See Change [24].

So far, only a handful of studies have tried to accept the challenge of discussing using gamified applications in a serious context, such as in disasters, through a scholarly body of work. This study has systematically tried to establish the idea of using gamified applications to increase the effectiveness of disaster education. As the research results emphasize, the participants were excited and enthusiastic to experience this new approach of learning. They were motivated by both extrinsic and intrinsic motivations provided by the gaming platform (Figure 8 and Figure 9). Further, by answering the question about ways to improve the game, the participants suggested using AI, VR, and AR technologies [90,91]. This shows that the use of gamified approaches to deliver disaster education will be an effective approach.

As the survey findings elaborated, gamified applications increase the frequency and the efficiency of knowledge sharing. The more players participating in the game, the more knowledge they gain. This activity enhances the knowledge of the players. Nevertheless, gamified applications need technical infrastructure, such as internet access and smart devices, to which people in developing countries may not have access. Nevertheless, the use of such technologies will gradually increase across the world including in developing countries [40]. For instance, now around 31% of people in East Asia, 19% in North Africa, and 17% in Central Asia have internet access and smart devices are becoming popular [8]. Furthermore, there is a clear demand for this kind of new and innovative approach among communities in developed countries [92,93,94,95].

6. Conclusions

The study provides insights into methods for imparting disaster education from a new perspective. This is not to undermine the significance of traditional approaches to disaster education, but to enhance these approaches by harmonizing them with contemporary technologies. Inarguably, disaster education is one of the most important approaches to increase disaster preparedness. Hence, strengthening, and popularizing disaster education is a necessity.

Firstly, the study findings confirmed the community demand for a change in the prevailing disaster education practices. Although there were more negatively classified tweets, these pointed out drawbacks and provided suggestions to improve the efficiency of prevailing classroom-based disaster education approaches. These further reflected how people use social media channels to express their perceptions of a burning issue in society. Therefore, the use of tweets to analyse sentiments and related attitudes can be identified as a good approach to deepen the understanding of current knowledge and the pressing demands of the public.

Secondly, the study identified the significance and the possibility of using gamified applications as a potential novel method to increase the efficiency of disaster education. As discussed in the paper, gamification attracts community attention through extrinsic elements and introduces motivational elements in a gaming environment, while indirectly transferring knowledge to the players [22,96,97,98]. As Australia is frequently exposed to bushfires, such an approach would further reduce community vulnerability by strengthening it through adequate knowledge [99,100,101]. Nevertheless, as an emerging area of research, the use of gamification and other technologies such as AI, AR, VR, and Web GIS technologies in the context of disaster education needs more attention from researchers [102,103,104,105,106,107,108,109,110].

In sum, the study findings confirmed the research hypothesis ‘Gamified applications related to disasters are efficient modes for increasing community disaster awareness’. Through the social media analytics we conducted, the study emphasized community concern about having a proper mechanism to increase community awareness, frequently avoiding time- and space-consuming methods especially. The study findings also emphasized the possibility of using gamified applications to increase community awareness through virtual platforms, which are relatively less space-, cost-, and time-consuming environments.

Lastly, we note that the study has the following limitations: (a) The study only used tweets circulated related to the 2019–2020 Australian bushfires; (b) The survey results are limited to a specific age group (between 18 and 22 years old) and therefore further research is required to assess the usability of gamified application across different age groups and with other young people in the same age group who are not university students; (c) Gamification as a method of education is more suitable for younger people; and (d) The small size of the sample for the survey (52 participants). Despite these limitations, the study has identified a new approach to disaster education from a novel perspective—i.e., gamification. Our prospective research will focus on addressing these limitations.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, N.K. and T.Y.; Methodology, N.K.; Software, N.K.; Validation, N.K.; Formal analysis, N.K.; Investigation, N.K.; Resources, N.K. and T.Y.; Data curation, N.K.; Writing—original draft preparation, N.K.; Writing—review and editing, T.Y. and A.G.; Supervision, T.Y. and A.G.; Project administration, T.Y. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Informed Consent Statement

An ethical approval was obtained from Queensland University of Technology’s Human Research Ethics Committee (#1900000214) to collect and analyse the data.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no known competing financial interest or personal relationship that could have appeared to influence the study reported.

References

- Boon, H.; Pagliano, P.J. Disaster education in Australian schools. Aust. J. Environ. Educ. 2014, 30, 187–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ludwig, T.; Kotthaus, C.; Reuter, C.; Van Dongen, S.; Pipek, V. Situated crowdsourcing during disasters. Int. J. Hum. Comput. Stud. 2017, 1, 103–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saja, A.A.; Teo, M.; Goonetilleke, A.; Ziyath, A.M. An inclusive and adaptive framework for measuring social resilience to disasters. Int. J. Disaster Risk Reduct. 2018, 28, 862–873. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dufty, N. Disaster Education, Communication, and Engagement; John Wiley & Sons: New York, NY, USA, 2020; pp. 156–198. [Google Scholar]

- Sendai Framework for Disaster Risk Reduction 2015–2030. Available online: https://www.unisdr.org/we/inform/publications/43291 (accessed on 24 September 2020).

- Preston, J. What Is Disaster Education? Brill Sense: Paderborn, Germany, 2012; pp. 342–401. [Google Scholar]

- Houston, J.B.; Hawthorne, J.; Perreault, M.F.; Park, E.H.; Goldstein-Hode, M.; Halliwell, M.R.; Griffith, S.A. Social media and disasters: A functional framework for social media use in disaster planning, response, and research. Disasters 2015, 39, 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kankanamge, N.; Yigitcanlar, T.; Goonetilleke, A. How engaging are disaster management related social media channels? Int. J. Disaster Risk Reduct. 2020, 48, 101571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dufty, N. A new approach to disaster education. In Proceedings of the International Emergency Management Society Annual Conference, Manila, Philippines, 13–16 November 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Yigitcanlar, T.; Corchado, J.; Mehmood, R.; Li, R.; Mossberger, K.; Desouza, K. Responsible urban innovation with local government artificial intelligence (AI): A conceptual framework and research agenda. J. Open Innov. Technol. Mark. Complex. 2021, 7, 71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shaw, R.; Shiwaku, K.; Takeuchi, Y. Disaster Education; Emerald: Bingley, UK, 2011; pp. 56–88. [Google Scholar]

- Kankanamge, N.; Yigitcanlar, T.; Goonetilleke, A.; Kamruzzaman, M. How can gamification be incorporated into disaster emergency planning? Int. J. Disaster Risk Reduct. 2020, 11, 481–506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Australian Institute for Disaster Resilience. Available online: https://knowledge.aidr.org.au/resources/bushfire-wooroloo-perth-hills-western-australia-2021/ (accessed on 26 May 2022).

- Rebolledo-Mendez, G.; Avramides, K.; de Freitas, S.; Memarzia, K. Societal impact of a serious game on raising public awareness. In Proceedings of the 2009 ACM SIGGRAPH Symposium on Video Games, New Orleans, LA, USA, 3–7 August 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Breuer, R.; Sewilam, H.; Nacken, H.; Pyka, C. Exploring the application of a flood risk management serious game platform. Environ. Earth Sci. 2017, 76, 93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khoury, M.; Gibson, M.J.; Savic, D.; Chen, A.S.; Vamvakeridou-Lyroudia, L.; Langford, H.; Wigley, S. A serious game designed to explore and understand the complexities of flood mitigation options in urban-rural catchments. Water 2018, 10, 1885. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Tomaszewski, B.; Schwartz, D.I. Critical spatial thinking and serious geogames. In Proceedings of the AGILE Workshop on Geogames and Geoplay, Wageningen, The Netherlands, 9 May 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Wahyudin, D.; Hasegawa, S.; Kamaludin, A. Students’ viewpoint of computer game for training in Indonesian universities and high schools. Educ. Inf. Technol. 2017, 22, 1927–1945. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stop Disasters. Available online: http://www.stopdisastersgame.org (accessed on 10 May 2022).

- Meesters, K.; Olthof, L.; Van de Walle, B. Disaster in my backyard. In Proceedings of the European Conference on Games Based Learning, Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 9–10 October 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Wells, S.; Kotkanen, H.; Schlafli, M.; Gabrielli, S.; Masthoff, J.; Jylhä, A.; Forbes, P. Towards an applied gamification model for tracking, managing and encouraging sustainable travel behaviours. ICST Trans. Ambient. Syst. 2014, 1, e2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Landers, R. Developing a theory of gamified learning: Linking serious games and gamification of learning. Simul. Gaming 2014, 45, 752–768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodela, R.; Ligtenberg, A.; Bosma, R. Conceptualizing serious games as a learning-based intervention in the context of natural resources and environmental governance. Water 2019, 11, 245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Kankanamge, N.; Yigitcanlar, T.; Goonetilleke, A.; Kamruzzaman, M. Determining disaster severity through social media analysis. Int. J. Disaster Risk Reduct. 2020, 42, 101360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, S.B. Crisis crowdsourcing framework. Comput. Support. Coop. Work 2014, 23, 389–443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aubert, A.H.; Bauer, R.; Lienert, J. A review of water-related serious games to specify use in environmental multi-criteria decision analysis. Environ. Model. Softw. 2018, 105, 64–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aubert, A.H.; Lienert, J. Gamified online survey to elicit citizens’ preferences and enhance learning for environmental decisions. Environ. Model. Softw. 2019, 111, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gardoni, P.; Murphy, C. Gauging the societal impacts of natural disasters using a capability approach. Disasters 2010, 34, 619–636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Australian Government Bureau of Meteorology. Available online: http://www.bom.gov.au/state-of-the-climate/State-of-the-Climate-2018.pdf (accessed on 10 May 2022).

- Kelly, B.; Ronan, K.R. Preparedness for natural hazards. Nat. Hazards 2018, 91, 19–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, V.A.; Ronan, K.R.; Johnston, D.M.; Peace, R. Evaluations of disaster education programs for children: A methodological review. Int. J. Disaster Risk Reduct. 2014, 9, 107–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dufty, N. Learning for disaster resilience. In Proceedings of the Australian & New Zealand Disaster and Emergency Management Conference, Brisbane, Australia, 16–18 April 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Ryan, R.M.; Deci, E.L. Intrinsic and extrinsic motivations. Contemp. Educ. Psychol. 2000, 25, 54–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arinta, R.R.; Emanuel, A.W. Effectiveness of gamification for flood emergency planning in the disaster risk reduction area. Int. J. Eng. Pedagog. 2020, 10, 108–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Y.; Tang, J. Exploring the motivational affordances of Danmaku video sharing websites. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Human-Computer Interaction, Toronto, ON, Canada, 17–22 July 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Kankanamge, N.; Yigitcanlar, T.; Goonetilleke, A.; Kamruzzaman, M. Can volunteer crowdsourcing reduce disaster risk? Int. J. Disaster Risk Reduct. 2019, 35, 101097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holley, R. Crowdsourcing. D-Lib Mag. 2010, 16, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neef, M.; van Dongen, K.; Rijken, M. Community-based comprehensive recovery. Int. J. Inf. Syst. Crisis Response Manag. 2013, 1, 8–32. [Google Scholar]

- Crowley, D.N.; Breslin, J.G.; Corcoran, P.; Young, K. Gamification of citizen sensing through mobile social reporting. In Proceedings of the 2012 IEEE International Games Innovation Conference, Rochester, NY, USA, 7–9 September 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Goodchild, M.F.; Glennon, J.A. Crowdsourcing geographic information for disaster response: A research frontier. Int. J. Digit. Earth 2010, 3, 231–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deterding, S.; Dixon, D.; Khaled, R.; Nacke, L. From game design elements to gamefulness. In Proceedings of the 15th International Academic MindTrek Conference: Envisioning Future Media Environments, Online, 28 September 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, S. Decision support model for introduction of gamification solution using AHP. Sci. World J. 2014, 1, 714239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prestopnik, N.; Crowston, K.; Wang, J. Gamers, citizen scientists, and data. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2017, 1, 254–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Onencan, A.; Van de Walle, B.; Enserink, B.; Chelang’a, J.; Kulei, F. WeShareIt Game. Procedia Eng. 2016, 159, 307–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Suarez, P. Rethinking engagement. Int. J. Geogr. Inf. Syst. 2015, 4, 1729–1749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bourgonjon, J.; Valcke, M.; Soetaert, R.; Schellens, T. Students’ perceptions about the use of video games in the classroom. Comput. Educ. 2010, 54, 1145–1156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Felicio, S.; Silva, V.; Dargains, A.; Souza, P.; Sampaio, F.; de Carvalho, P.; Gomes, J.; Borges, M. Stop disasters game experiment with elementary school students in Rio de Janeiro: Building safety culture. In Proceedings of the 11th International Conference on Information Systems for Crisis Response and Management, ISCRAM, University Park, PA, USA, 18–21 May 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Seaborn, K.; Fels, D.I. Gamification in theory and action. Int. J. Hum. Comput. Stud. 2015, 74, 14–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C. Gamification in a Volunteered Geographic Information Context with Regard to Contributors’ Motivations: A Case Study of OpenStreetMap. Master’s Thesis, University of Waterloo, Waterloo, ON, Canada, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- McKenzie, G. Gamification and location-based services. In Proceedings of the Workshop on Cognitive Engineering for Mobile GIS, Belfast, ME, USA, 12 September 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Martí, I.G.; Rodríguez, L.E.; Benedito, M.; Trilles, S.; Beltrán, A.; Díaz, L.; Huerta, J. Mobile application for noise pollution monitoring through gamification techniques. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Entertainment Computing, Heidelberg, Germany, 26–29 September 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Gnat, M.; Leszek, K.; Olszewski, R. The use of geoinformation technology, augmented reality and gamification in the urban modeling process. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Computational Science and Its Applications, Online, 12 July 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Yoon, K. The gamification of mobile communication among young smartphone users in Seoul. Asiascape Digit. Asia 2016, 3, 60–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burston, J.; Ware, D.; Tomlinson, R. The real-time needs of emergency managers for tropical cyclone storm tide forecasting. Nat. Hazards 2015, 78, 1653–1668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sosko, S.; Dalyot, S. Crowdsourcing user-generated mobile sensor weather data for densifying static geosensor networks. Int. J. Geogr. Inf. Syst. 2017, 6, 61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Mylonas, G.; Amaxilatis, D.; Pocero, L.; Markelis, I.; Hofstaetter, J.; Koulouris, P. Using an educational iot lab kit and gamification for energy awareness in European schools. In Proceedings of the Conference on Creativity and Making in Education, Online, 18 June 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Suwanmolee, S. The Gamification of COVID-19 Pandemic as an Active Learning Tool in Disaster Education. In Proceedings of the 6th UPI International Conference on TVET 2020, Online, 4 February 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Bell, N. Development in Australian bushfire prone areas. Environment 2019, 5, 1–14. [Google Scholar]

- Australian Association for Environmental Education. Available online: http://www.aaee.org.au/about (accessed on 10 September 2020).

- Blanchi, R.; Leonard, J.; Haynes, K.; Opie, K.; James, M.; de Oliveira, F.D. Environmental circumstances surrounding bushfire fatalities in Australia 1901–2011. Environ. Sci. Policy 2014, 37, 192–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Climate Council. Available online: https://www.climatecouncil.org.au/not-normal-climate-change-bushfire-web/ (accessed on 26 May 2022).

- Gray, B.J.; Weal, M.J.; Martin, D. Social media and disasters. Int. J. Inf. Syst. Crisis Response Manag. 2016, 8, 41–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jung, J.Y.; Moro, M. Multi-level functionality of social media in the aftermath of the Great East Japan Earthquake. Disasters 2014, 38, 123–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kryvasheyeu, Y.; Chen, H.; Obradovich, N.; Moro, E.; Van Hentenryck, P.; Fowler, J.; Cebrian, M. Rapid assessment of disaster damage using social media activity. Sci. Adv. 2016, 2, e1500779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- The Year on Twitter. Available online: https://blog.twitter.com/en_gb/a/en-gb/2013/2013-the-year-on-twitter.html (accessed on 12 September 2020).

- Dufty, N. A society-first approach to flood mitigation. In Proceedings of the 56th Floodplain Management Australia Conference, Nowra, Australia, 17–20 May 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Wattenberg, M.; Viégas, F.B. The word tree, an interactive visual concordance. IEEE Trans. Vis. Comput. Graph. 2008, 14, 1221–1228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lai, A.K.H.; Bin Noor Azhar, A.M.; Binti Bustam, A.; Tiong, X.T.; Chan, H.C.; Bin Ahmad, R.; Chew, K.S. A comparison between the effectiveness of a gamified approach with the conventional approach in point-of-care ultrasonographic training. BMC Med. Educ. 2020, 20, 263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woolwine, S.; Romp, C.R.; Jackson, B. Game on. J. Nurses Prof. Dev. 2019, 35, 255–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gampell, A.V.; Gaillard, J.C.; Parsons, M.; Fisher, K. Beyond Stop Disasters 2.0. Environ. Hazards. 2017, 16, 180–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olszewski, R.; Turek, A.; Laczynski, M. Urban Gamification as a Source of Information for Spatial Data Analysis and Predictive Participatory Modelling of a City’s Development. In Proceedings of the 5th International Conference on Data Management Technologies and Applications (DATA 2016), Setubal, Portugal, 24–26 July 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Pereira, G.; Prada, R.; Paiva, A. Disaster prevention social awareness. In Proceedings of the 6th International Conference on Games and Virtual Worlds for Serious Applications, Valletta, Malta, 9–12 September 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Social and Citizenship Education Association of Australia. Available online: https://www.sceaa.org.au/# (accessed on 10 September 2020).

- Bang, J.; Lee, Y.; Lee, Y.T.; Park, W. AR/VR based smart policing for fast response to crimes in safe city. In Proceedings of the IEEE International Symposium on Mixed and Augmented Reality Adjunct, Beijing, China, 10–18 October 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Anttiroiko, A.V. U-cities reshaping our future. AI Soc. 2013, 28, 491–507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Longueville, B.; Luraschi, G.; Smits, P.; Peedell, S.; De Groeve, T. Citizens as sensors for natural hazards. Geomatica 2010, 64, 41–59. Available online: https://publications.jrc.ec.europa.eu/repository/handle/JRC52420 (accessed on 18 May 2022).

- Goodchild, M.F. Citizens as sensors: The world of volunteered geography. GeoJournal 2007, 69, 211–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Sprake, J.; Rogers, P. Crowds, citizens and sensors. Pers Ubiquitous Comput. 2014, 18, 753–764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olszewski, R.; Wendland, A. Digital Agora–Knowledge acquisition from spatial databases, geoinformation society VGI and social media data. Land Use Policy 2021, 109, 105614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, H.; Barbier, G.; Goolsby, R. Harnessing the crowdsourcing power of social media for disaster relief. IEEE Intell. Syst. 2011, 26, 10–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Albuquerque, J.P.; Herfort, B.; Brenning, A.; Zipf, A. A geographic approach for combining social media and authoritative data towards identifying useful information for disaster management. Int. J. Geogr. Inf. Syst. 2015, 29, 667–689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Bennani, S.; Maalel, A.; Ben Ghezala, H. Adaptive gamification in E-learning: A literature review and future challenges. Comput. Appl. Eng. Educ. 2022, 30, 628–642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- IMD World Digital Competitiveness Ranking. Available online: https://dailynewshungary.com/imd-world-digital-competitiveness-ranking-2020-hungary-maintains-competitive-position/ (accessed on 10 September 2020).

- Kashian, A.; Rajabifard, A.; Richter, K.F.; Li, S.; Dragicevic, S. RoadPlex: A mobile VGI game to collect and validate data for POIs. ISPRS Ann. Photogramm. Remote Sens. Spat. Inf. Sci. 2014, 2, 55–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Yigitcanlar, T.; Kankanamge, N.; Regona, M.; Ruiz Maldonado, A.; Rowan, B.; Ryu, A.; Li, R. Artificial intelligence technologies and related urban planning and development concepts: How are they perceived and utilized in Australia? J. Open Innov. Technol. Mark. Complex 2020, 6, 187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naranjo-Zolotov, M.J. Collecting Data for Indoor Mapping of the University of Münster via a Location Based Game; Universitat Jaume I: Castellón de la Plana, Spain, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- McCartney, E.A.; Craun, K.J.; Korris, E.; Brostuen, D.A.; Moore, L.R. Crowdsourcing the national map. Cartogr. Geogr. Inf. Sci. 2015, 42, 54–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, D.; Shen, K.; Case, B.; Garg, D.; Alperovich, G.; Kuznetsov, D.; Gupta, R.; Durumeric, Z. All things considered. In Proceedings of the 28th USENIX Security Symposium, Berkeley, CA, USA, 14–16 August 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Baytiyeh, H. Can disaster risk education reduce the impacts of recurring disasters on developing societies? Educ. Urban Soc. 2018, 50, 230–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Catal, C.; Akbulut, A.; Tunali, B.; Ulug, E.; Ozturk, E. Evaluation of augmented reality technology for the design of an evacuation training game. Virtual Real. 2020, 24, 359–368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Sezgin, S.; Yüzer, T.V. Analysing adaptive gamification design principles for online courses. Behav. Inf. Technol. 2022, 41, 485–501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yigitcanlar, T.; Wilson, M.; Kamruzzaman, M. Disruptive impacts of automated driving systems on the built environment and land use: An urban planner’s perspective. J. Open Innov. Technol. Mark. Complex. 2019, 5, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Yigitcanlar, T.; Cugurullo, F. The sustainability of artificial intelligence: An urbanistic viewpoint from the lens of smart and sustainable cities. Sustainability 2020, 12, 8548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rincon-Flores, E.G.; Rodriguez-Rodriguez, N.; Santos-Guevara, B.N.; Sonoda, A.M.; Quintana-Cruz, H. Gamit! Interactive platform for gamification. In Proceedings of the 2022 IEEE Global Engineering Education Conference, Gammarth, Tunisia, 28–31 March 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Pancholi, S.; Yigitcanlar, T.; Guaralda, M. Public space design of knowledge and innovation spaces: Learnings from Kelvin Grove Urban Village, Brisbane. J. Open Innov. Technol. Mark. Complex. 2015, 1, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Goonetilleke, A.; Yigitcanlar, T.; Ayoko, G.; Egodawatta, P. Sustainable Urban Water Environment: Climate, Pollution and Adaptation; Edward Elgar: Cheltenham, UK, 2014; pp. 245–346. [Google Scholar]

- Dospinescu, O.; Dospinescu, N. Perception over e-learning tools in higher education: Comparative study Romania and Moldova. In Proceedings of the IEEE 2020 International Conference, Bucharest & Timisoara, Romania, 1–4 May 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nadi-Ravandi, S.; Batooli, Z. Gamification in education: A scientometric, content and co-occurrence analysis of systematic review and meta-analysis articles. Educ. Inf. Technol. 2022, 1–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Filkov, A.I.; Ngo, T.; Matthews, S.; Telfer, S.; Penman, T.D. Impact of Australia’s catastrophic 2019/20 bushfire season on communities and environment. J. Saf. Sci. Resil. 2020, 1, 44–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rawluk, A.; Ford, R.; Neolaka, F.; Williams, K. Public values for integration in natural disaster management and planning: A case study from Victoria, Australia. J. Environ. Manag. 2017, 185, 11–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- The 2019–2020 Australian Bushfires. Available online: https://parlinfo.aph.gov.au/parlInfo/download/library/prspub/7234762/upload_binary/7234762.pdf (accessed on 10 September 2020).

- Arthur, R.; Boulton, C.A.; Shotton, H.; Williams, H.T. Social sensing of floods in the UK. PLoS ONE 2018, 13, e0189327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yigitcanlar, T. Smart city policies revisited: Considerations for a truly smart and sustainable urbanism practice. World Technopolis Rev. 2018, 7, 97–112. [Google Scholar]

- Scholefield, S.; Shepherd, L. Gamification techniques for raising cyber security awareness. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Human-Computer Interaction, Dundee, UK, 26–31 July 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Brauner, P.; Calero Valdez, A.; Schroeder, U.; Ziefle, M. Increase physical fitness and create health awareness through exergames and gamification. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Human Factors in Computing and Informatics, Berlin, Germany, 1–3 July 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Alloghani, M.; Hussain, A.; Al-Jumeily, D.; Aljaaf, A.; Mustafina, J. Gamification in e-governance: Development of an online gamified system to enhance government entities services delivery and promote public’s awareness. In Proceedings of the 5th International Conference on Information and Education Technology, Tokyo, Japan, 10–12 January 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Spanellis, A.; Harviainen, J.T. Transforming Society and Organizations through Gamification; Springer International Publishing: New York, NY, USA, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Li, J.; Xia, H.; Qin, Y.; Fu, P.; Guo, X.; Li, R.; Zhao, X. Web GIS for sustainable education: Towards natural disaster education for high school students. Sustainability 2022, 14, 2694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, W. Beyond the ‘two cultures’ in the teaching of disaster: Or how disaster education and science education could benefit each other. Educ. Philos. Theory 2020, 52, 1434–1448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shaw, R. Thirty years of science, technology, and academia in disaster risk reduction and emerging responsibilities. Int. J. Disaster Risk Sci. 2020, 11, 414–425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).