Turning Farmers into Business Partners through Value Co-Creation Projects. Insights from the Coffee Supply Chain

Abstract

:1. Introduction

- RQ1:

- How can the effectiveness of empowerment actions to moderate the effects of vulnerability factors within the coffee supply chain be qualitatively evaluated?

- RQ2:

- Do current empowerment actions within specific value co-creation projects enable coffee farmers to turn from being vulnerable to becoming business partners? If yes, how?

2. Literature Background

2.1. Resilience and Value Co-Creation

2.2. Empowerment of Low-Power, Vulnerable Stakeholders

2.3. Overcoming Vulnerability through Empowerment

3. The Research Context: Coffee Supply Chain and Low-Power Stakeholders

- poor education,

- complex and instable political and economic conditions within a given country,

- market and pricing instability,

- reduced trading capabilities and negotiation power,

- asymmetry of information,

- climate change, and

- lack of business continuation.

- RQ2:

- “Do current empowerment actions within specific value co-creation projects enable coffee farmers to turn from being vulnerable to becoming business partners? If yes, how?”

4. Methods

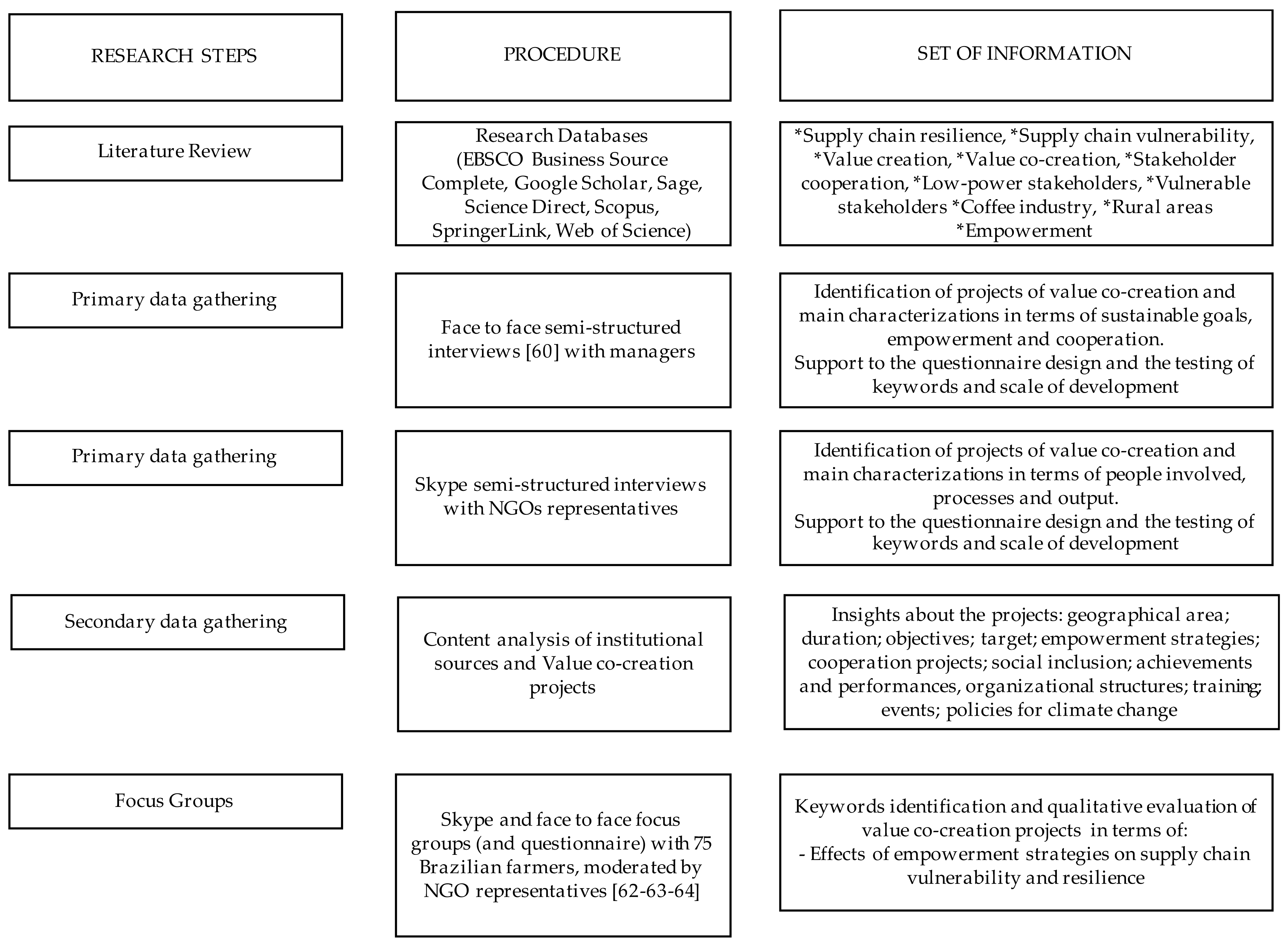

4.1. Data Collection

4.2. Data Analysis

- the literature on empowerment and the coffee industry;

- the opinions of managers and NGO representatives;

- ATLAS.ti (scientific Software Development GmbH, Berlin, Germany)—a type of software employed for qualitative analysis, data management, and coding, which was used for further testing of the emergent keywords. We followed the principle of thematic analysis and found that ATLAS.ti supported the investigation in keeping track of emergent levels (low, medium, and high) and in identifying the frequency of keywords within each level and each dimension.

5. Results

5.1. Keywords that Identified the Empowerment Dimensions’ Development

5.2. Qualitative Evaluation of Empowerment Development

6. Discussion

7. Conclusions, Theoretical Contributions, and Managerial Implications

Author Contributions

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

References

- Li, R.; Dong, Q.; Jin, C.; Kang, R. A New Resilience Measure for Supply Chain Networks. Sustainability 2017, 9, 144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pettit, T.J.; Fiksel, J.; Croxton, K.L. Ensuring supply chain resilience: Development of a conceptual framework. J. Bus. Logist. 2010, 31, 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pettit, T.J.; Croxton, K.L.; Fiksel, J. Ensuring supply chain resilience: Development and implementation of an assessment tool. J. Bus. Logist. 2013, 34, 46–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Christopher, M.; Peck, H. Building the resilient supply chain. Int. J. Logist. Manag. 2004, 15, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Cranfield University. Supply Chain Vulnerability: Executive Report, School of Business, Cranfield, UK; Cranfield University: Bedford, UK, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Li, Z.; Xu, Y.; Deng, F.; Liang, X. Impacts of Power Structure on Sustainable Supply Chain Management. Sustainability 2017, 10, 55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dawkins, C.E. The principle of good faith: Toward substantive stakeholder engagement. J. Bus. Ethics 2014, 121, 283–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dawkins, C. Agonistic pluralism and stakeholder engagement. Bus. Ethics Q. 2015, 25, 1–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freeman, R.E.; Wicks, A.; Harrison, J.; Parmar, B.; de Colle, S. Stakeholder Theory: The State of the Art; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Greenwood, M.; Van Buren, H.J., III. Trust and stakeholder theory: Trustworthiness in the organisation–stakeholder relationship. J. Bus. Ethics 2010, 95, 425–438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pickett, C. Prepare for supply chain disruptions before they hit. Logist. Today 2006, 47, 22–25. [Google Scholar]

- Folke, C. Resilience: The emergence of a perspective for social–ecological systems analyses. Glob. Environ. Chang. 2006, 16, 253–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Svensson, G. Dyadic vulnerability in companies’ inbound and outbound logistics flows. Int. J. Logist. 2002, 5, 13–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Casali, G.L.; Perano, M.; Moretta Tartaglione, A.; Zolin, R. How Business Idea Fit Affects Sustainability and Creates Opportunities for Value Co-Creation in Nascent Firms. Sustainability 2018, 10, 189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alves, F.S.; Segatto, A.P.; De-Carli, E. Theoretical framework about relational capability on inter-organizational cooperation. J. Ind. Integr. Manag. 2016. [CrossRef]

- Strand, R.; Freeman, R.E. Scandinavian cooperative advantage: The theory and practice of stakeholder engagement in Scandinavia. J. Bus. Ethics 2015, 127, 65–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saarijärvi, H.; Kannan, P.K.; Kuusela, H. Value co-creation: Theoretical approaches and practical implications. Eur. Bus. Rev. 2013, 25, 6–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pfeffer, J.; Salancik, G.R. The External Control of Organizations: A Resource Dependence Perspective; Stanford University Press: Palo Alto, CA, USA, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Ahen, F. Responsibilization and MNC–Stakeholder Engagement: Who Engages Whom in the Pharmaceutical Industry? In Stakeholder Engagement: Clinical Research Cases; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2017; pp. 87–112. [Google Scholar]

- Derry, R. Reclaiming marginalized stakeholders. J. Bus. Ethics 2012, 111, 253–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loconto, A.; Simbua, E. Making Roofs for Small Holders Cooperatives in Tanzanian Tea Production: Can Fair Trade Do that? J. Bus. Ethics 2012, 108, 451–465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hwarng, H.B.; Chong, C.S.P.; Xie, N.; Burgess, T.F. Modelling a complex supply chain: Understanding the effect of simplified assumptions. Int. J. Prod. Res. 2005, 43, 2829–2872. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Potts, J. Building a Sustainable Coffee Sector Using Market Based Approaches: The Role of Multi Stakeholder Cooperation, 2003. United Nations Conference on Trade and Development, iisd. Available online: http://www.ico.org/documents/sustain1.pdf (accessed on 28 March 2018).

- Rappaport, J. Studies in empowerment: Introduction to the issue. In Studies in Empowerment: Steps toward Understanding and Action; Routledge: London, UK, 1984; pp. 1–7. [Google Scholar]

- Zimmerman, M.A. Taking aim on empowerment research: On the distinction between individual and psychological conceptions. Am. J. Community Psychol. 1990, 18, 169–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perkins, D.D.; Zimmerman, M.A. Empowerment theory, research, and application. Am. J. Community Psychol. 1995, 23, 569–579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jones, T.M.; Felps, W. Stakeholder happiness enhancement: A neo-utilitarian objective for the modern corporation. Bus. Ethics Q. 2013, 23, 349–379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lankoski, L.; Smith, N.C.; Van Wassenhove, L. Stakeholder judgments of value. Bus. Ethics Q. 2016, 26, 227–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, S.Y.; Yen, C.Y.; Tsai, K.N.; Lo, W.S. A Conceptual Framework for Agri-Food Tourism as an Eco-Innovation Strategy in Small Farms. Sustainability 2017, 9, 1683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Devin, B.L.; Lane, A.B. Communicating engagement in corporate social responsibility: A meta-level construal of engagement. J. Public Relat. Res. 2014, 26, 436–454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burchell, J.; Cook, J. It’s good to talk? Examining attitudes towards corporate social responsibility dialogue and engagement processes. Bus. Ethics Eur. Rev. 2006, 15, 154–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burchell, J.; Cook, J. Stakeholder dialogue and organizational learning: Changing relationships between companies and NGOs. Bus. Ethics Eur. Rev. 2008, 17, 35–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harrison, J.S.; Wicks, A.C. Stakeholder theory, value, and firm performance. Bus. Ethics Q. 2013, 23, 97–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Austin, J.E.; Seitanidi, M.M. Collaborative value creation: A review of partnering between nonprofits and businesses: Part I. Value creation spectrum and collaboration stages. Nonprofit Volunt. Sect. Q. 2012, 41, 726–758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- London, T.; Hart, S.L. Creating a Fortune with the Base of the Pyramid. In Next Generation Business Strategies for the Base of the Pyramid; FT Press: Upper Saddle River, NJ, USA, 2011; pp. 1–18. [Google Scholar]

- Ählström, J.; Sjöström, E. CSOs and business partnerships: Strategies for interaction. Bus. Strategy Environ. 2005, 14, 230–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Papineau, D.; Kiely, M.C. Participatory evaluation in a community organization: Fostering stakeholder empowerment and utilization. Eval. Program Plan. 1996, 19, 79–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mena, S.; de Leede, M.; Baumann, D.; Black, N.; Lindeman, S.; McShane, L. Advancing the business and human rights agenda: Dialogue, empowerment, and constructive engagement. J. Bus. Ethics 2010, 93, 161–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rowe, W.E.; Jacobs, N.F.; Heath, G. Facilitating development of organizational productive capacity: A role for empowerment evaluation. Can. J. Program Eval. 1999, 14, 69–92. [Google Scholar]

- Bartunek, J.M.; Foster-Fishman, P.G.; Keys, C.B. Using collaborative advocacy to foster intergroup cooperation: A joint insider-outsider investigation. Hum. Relat. 1996, 49, 701–733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Ran, B. Sustainable Collaborative Governance in Supply Chain. Sustainability 2018, 10, 171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ansell, C.; Gash, A. Collaborative governance in theory and practice. J. Public Adm. Res. Theory 2008, 18, 543–571. [Google Scholar]

- Prato, B.; Longo, R. Empowerment of Poor Rural People through Initiatives in Agriculture and Natural Resource Management; OECD: Paris, France, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Peck, H. Drivers of supply chain vulnerability: An integrated framework. Int. J. Phys. Distrib. Logist. Manag. 2005, 35, 210–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fiksel, J. Sustainability and resilience: Toward a systems approach. Sustain. Sci. Pract. Policy 2006. [CrossRef]

- Capra, F. The Web of Life: A New Scientific Understanding of Living Systems; Anchor: Buffalo, NY, USA, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Wheatley, M.J. Leadership and the New Science; Barrett-Koefler: Oakland, CA, USA, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Prahalad, C.K. Bottom of the Pyramid as a Source of Breakthrough Innovations. J. Prod. Innov. Manag. 2012, 29, 6–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salvia, R.; Quaranta, G. Place-Based Rural Development and Resilience: A Lesson from a Small Community. Sustainability 2017, 9, 889. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fawcett, S.B.; Paine-Andrews, A.; Francisco, V.T.; Schultz, J.A.; Richter, K.P.; Lewis, R.K.; Lopez, C.M. Using empowerment theory in collaborative partnerships for community health and development. Am. J. Community Psychol. 1995, 23, 677–697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kumar, V.; Pansari, A. Competitive advantage through engagement. J. Mark. Res. 2016, 53, 497–514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blowfield, M.; Dolan, C. Fairtrade Facts and Fancies; What Kenyan Fairtrade tea tell us about Business Role as development agent. J. Bus. Ethics 2010, 93, 143–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valkila, J.; Haaparane, P.; Niemi, N. Empowering Coffee traders? The coffee value chain from Nicaragua Fair Trade Farmers to Finnish Consumers. J. Bus. Ethics 2010, 97, 257–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watson, K.; Achinelli, M.L. Context and contingency: The coffee crisis for conventional small-scale coffee farmers in Brazil. Geogr. J. 2008, 174, 223–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Graeub, B.E.; Chappell, M.J.; Wittman, H.; Ledermann, S.; Kerr, R.B.; Gemmill-Herren, B. The state of family farms in the world. World Dev. 2015, 87, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Upendranadh, C.; Subbaiah, C.A. Small Growers and Coffee Marketing-Issues and Perspective from the Field; Centre for Development Studies: Kerala, India, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Bjorvatn, K.; Milford, A.B.; Sørgard, L. Farmers, Middlemen and Exporters: A Model of Market Power, Pricing and Welfare in a Vertical Supply Chain. Rev. Dev. Econ. 2015, 19, 31–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bush, S.B. Derivatives and Development: A Political Economy of Global Finance, Farming, and Poverty; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Guasch, J.L.; Polastri, R. Trade and Competitiveness in Peru. In An Opportunity for a Different; Giugale, M., Fretes-Cibil, V., Newman, J., Eds.; The World Bank: Washington, DC, USA, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Bernard, H.R. Research Methods in Cultural Anthropology; Sage: Newbury Park, CA, USA, 1988. [Google Scholar]

- Goldman, A.E. The Group Depth Interview. J. Mark. 1962, 26, 61–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gibbs, A. Focus Groups; Social Research Update: Guildford, UK, 1997; p. 19. [Google Scholar]

- Carey, M. The Group Effect in Focus Group: Planning, Implementing, and Interpreting Focus Group Research. In Critical Issues in Qualitative Research Methods; Morse, J., Ed.; SAGE Publications: London, UK, 1994; pp. 225–241. [Google Scholar]

- Morgan, D.L.; Kreuger, R.A. When to use focus groups and why. In Successful Focus Groups; Morgan, D.L., Ed.; SAGE: London, UK, 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Reed, M.S.; Graves, A.; Dandy, N.; Posthumus, H.; Hubacek, K.; Morris, J.; Prell, C.; Quinn, C.H.; Stringer, L.C. Who’s in and why? A typology of stakeholder analysis methods for natural resource management. J. Environ. Manag. 2009, 90, 1933–1949. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yin, R.K. Applications of Case Study Research. Applied Social Research Methods Series; SAGE Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Hsieh, H.F.; Shannon, S.E. Three approaches to qualitative content analysis. Qual. Health Res. 2005, 15, 1277–1288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rosengren, K.E. Advances in Content Analysis; SAGE Publications Incorporated: London, UK, 1981; Volume 9. [Google Scholar]

| Empowerment Dimensions (Capabilities, Skills, Knowledge) | Scale of Empowerment Dimensions Development | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Low | Medium | High | |

| Business Mindset [37,38,39,48] | |||

| Cooperation [40] | |||

| Adaptability [44,45,46,47] | |||

| Interactions and Awareness [23,31,51] | |||

| Question Number | Content | Keywords Identification |

|---|---|---|

| Q.1 | Which kind of contact do you have with the roaster? | 1. 2. 3. |

| Q.2 | What do you want to achieve or to be in 5 years? | 1. 2. 3. |

| Q.3 | What do you need for achieving your goals? | 1. 2. 3. |

| Q.4 | Which resources you need for achieving your goals? | 1. 2. 3. |

| Q.5 | Where do you find the people needed? | 1. 2. 3. |

| Q.6 | Where do you find the resources needed? | 1. 2. 3. |

| Q.7 | Where do you mainly spend your money on? | 1. 2. 3. |

| Q.8 | Rank the relevance of these following topics for your business (from 1-poor to 5-very relevant) | Climate Change; Roasters’ engagement to the project; NGO engagement to the project; training programs on quality and productivity; financial advisory; nature and fairness of payments; social inclusion; youth inclusion; women inclusion; human rights; access to education |

| Empowerment Dimensions (Capabilities, Skills, Knowledge) | Scale of Empowerment Dimensions Development | Questions | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Low | Medium | High | ||

| Business Mindset [37,38,39,48] | Q.2; Q.3; Q.7 | |||

| Cooperation [40] | Q.3; Q.6 | |||

| Adaptability [44,45,46,47] | Q.4; Q7; Q.8 | |||

| Interactions and Awareness [51,31,23] | Q.1; Q.5 | |||

| Empowerment Dimensions (Capabilities, Skills, Knowledge) | Scale Of Empowerment Dimensions Development | Questions | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Low | Medium | High | ||

| Business Mindset [37,38,39,48] | family; house; quantity; cash; entertainment | productivity; production; financing; better pricing; nature and fairness of payments; cash flow; expenses | quality; knowledge; competences; sustainable production; certification; financial advisory; investments; farm; youth inclusion | Q.2; Q.3; Q.7 |

| Cooperation [40] | institutions; myself; family | banks; financial resources; NGOs support in suppliers identification | representatives; organizations; associations; cooperatives; shared technology; advisory | Q.3; Q.6 |

| Adaptability [44,45,46,47] | supervision; family | free technical assistance | climate change; shared practices; training; understanding; experience | Q.4; Q7; Q.8 |

| Interactions and Awareness [23,31,51] | intermediaries; first level traders; absence of contact | second level traders; low contact; municipalities | direct bargaining; roaster; importers; transparency in cooperation; high contact; society; women inclusion | Q.1; Q.5 |

| Dimensions | Keywords | Frequency of Answers (%)—Extent of Development | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Low | Medium | High | ||

| Business Mindset | Better pricing | 95 | ||

| Farm | 92 | |||

| Financing | 92 | |||

| Productivity | 90 | |||

| Financial advisory | 88 | |||

| Quality | 85 | |||

| Production | 82 | |||

| Nature and fairness of payments | 77 | |||

| Investments | 70 | |||

| Knowledge | 70 | |||

| Sustainable production | 64 | |||

| Cash flow | 45 | |||

| Competences | 44 | |||

| House | 42 | |||

| Family | 35 | |||

| Expenses | 35 | |||

| Certification | 35 | |||

| Youth inclusion | 27 | |||

| Cash | 22 | |||

| Entertainment | 22 | |||

| Quantity | 10 | |||

| Cooperation | Financial resources | 90 | ||

| NGOs support in suppliers’ identification | 92 | |||

| Banks | 85 | |||

| Organizations | 77 | |||

| Cooperatives | 77 | |||

| Associations | 65 | |||

| Advisory | 45 | |||

| Representative | 43 | |||

| Family | 42 | |||

| Shared technology | 32 | |||

| Institution | 32 | |||

| Myself | 20 | |||

| Adaptability | Free technical assistance | 85 | ||

| Training | 85 | |||

| Climate change | 75 | |||

| Shared practices | 60 | |||

| Experience | 56 | |||

| Understanding | 45 | |||

| Supervision | 45 | |||

| Family | 32 | |||

| Interactions and Awareness | Municipalities | 72 | ||

| Low contact | 67 | |||

| First level traders | 67 | |||

| Second level traders | 56 | |||

| Intermediaries | 35 | |||

| Society | 30 | |||

| Roaster | 22 | |||

| Women inclusion | 12 | |||

| Importers | 10 | |||

| Absence of contact | 10 | |||

| Transparency in cooperation | 7 | |||

| Direct bargaining | 5 | |||

| High contact | 4 | |||

© 2018 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Candelo, E.; Casalegno, C.; Civera, C.; Mosca, F. Turning Farmers into Business Partners through Value Co-Creation Projects. Insights from the Coffee Supply Chain. Sustainability 2018, 10, 1018. https://doi.org/10.3390/su10041018

Candelo E, Casalegno C, Civera C, Mosca F. Turning Farmers into Business Partners through Value Co-Creation Projects. Insights from the Coffee Supply Chain. Sustainability. 2018; 10(4):1018. https://doi.org/10.3390/su10041018

Chicago/Turabian StyleCandelo, Elena, Cecilia Casalegno, Chiara Civera, and Fabrizio Mosca. 2018. "Turning Farmers into Business Partners through Value Co-Creation Projects. Insights from the Coffee Supply Chain" Sustainability 10, no. 4: 1018. https://doi.org/10.3390/su10041018

APA StyleCandelo, E., Casalegno, C., Civera, C., & Mosca, F. (2018). Turning Farmers into Business Partners through Value Co-Creation Projects. Insights from the Coffee Supply Chain. Sustainability, 10(4), 1018. https://doi.org/10.3390/su10041018