Abstract

Dust pollution is a key issue that contractors ought to address in the sphere of sustainable construction. Governments on behalf of the public assume part of the responsibilities for minimizing dust emissions on construction sites. However, the measures that are useful for governments to fulfill such a responsibility have not been explored explicitly in previous studies. The aim of this research is to map out China’s practices in this area with the intention of filling the knowledge gap. Using a combination of research methods, five categories of governmental measures are proposed: technological, economic, supervisory, organizational, and assessment-based. Data from 37 major cities in China are collected for analysis. While the proposed categories of measures are demonstrated in China, the data analysis results show that governments prefer technological and organizational measures, and institutional guarantees and technological innovation are a prerequisite for dust-free construction. This research provides a comprehensive examination of construction dust control from the perspective of governments, and it can assist governments in improving the performance of dust management in the construction context.

1. Introduction

The construction industry is often criticized for being one of the heavy polluters that generate dust to the atmosphere from construction works. Construction dust emission (CDE) originates from many types of onsite activities such as excavation, drilling, bulk material transportation, loading and unloading, open-air material storage, concrete and mortar making, cutting and filling, and the movement of equipment [1,2]. These activities release the calcium element of PM2.5, which is a component of construction dust and an environmental pollutant [3,4]. In effect, construction dust forms a nuisance to site workers [5,6] and has adverse off-site impacts on local communities [7,8]. The existence of construction dust in the human lung can result in diseases such as silicosis, bronchitis, the obstruction of trachea, and occupational asthma [9]. In China, for instance, the human health damages caused by construction dust pollution account for 27% of the total impacts of construction projects on the natural environment [10]. Similar situations are appreciated in other countries such as the European Union, Great Britain, and the United States [11,12,13]. It is thus reasonable to predict that construction dust pollution will be an acute environmental crisis in the future if it is not under control [14].

Construction dust is released in various locations, to varying extents, and with different durations and frequencies [15]. Finding an effective way to control CDE is subject to obstacles. One of the major obstacles is an increase in construction cost, which contractors have to handle ultimately [7]. Indeed, both the clients and contractors may not accept those construction projects that have the problem of cost overrun [16]. In addition, voluntary control over the construction dust emission of contractors often reaches an environmental cartel agreement among themselves, which is unfavorable to the sustainability of the construction industry [17,18]. Cho [19] pointed out that the rationale for governments to intervene in market operation is to compensate for market failures. It should be another type of market failure if contractors have little enthusiasm for construction dust control in their own right.

There are enormous demands for policymakers to reduce the emission of dust on construction sites [5,10,20]. To echo this, previous studies have investigated a few approaches for governments to participate in the exercise of construction dust control. Wu et al. [14] identified the sources of construction dust emissions. They recommended that governments account for two categories of dust control regulations: environmental protection-related and construction-related. To underpin the formulation of governmental measures, sources of CDE, measures to inhibit CDE, and the utilization of CDE technologies have often been discussed in previous studies [14,21]. While the existing measures complement each other, few of them portray a whole picture of measures that governments can implement in a direct way. Instead, the measures adopted by a government are unsustainable or are not effective enough to inspire contractors to implement dust-free construction. As described in the following section, China’s governments across various levels have accumulated rich experiences in handling this matter, which sheds some lights on the practices in other countries. Therefore, the aim of this study is to map out what governments can do in response to contractors’ dust emissions in the Architecture, Engineering and Construction (AEC) industry by taking China as a case. Specifically, the research objectives are twofold:

- (1)

- To identify the measures that China’s governments have adopted, and

- (2)

- To analyze the tendencies that China’s governments face in the choice of the dust control measures.

This study contributes to the body of knowledge by (1) mapping out China’s experiences; and (2) providing a cornerstone for future studies to examine the effectiveness of the measures. This work can aid those governments that currently have the pressure of mitigating CDE in improving their understanding of construction dust control, formulating dust control-related policies, and popularizing sustainable construction industrywide.

The paper is organized as follows. First, China’s practices are presented to set the scene for the study. Second, the framework of governmental measures is proposed by conducting a hybrid of research methods. Third, a collection of samples is targeted to test the proposed framework. Data about the sample are extracted using the approaches of content analysis and correspondence analysis. The results of statistical analysis are elaborated to test the proposed framework. The last section concludes the research findings.

2. Background

In China, an ambitious program for urbanization was launched by the Central Government in the 1980s [22]. Recent years have witnessed the rapid change of urbanization in China. Nevertheless, the progress of urbanization nationwide has been associated with the outspread distribution of dust pollution [23,24,25,26]. Many regions have encountered an increase in environmental deterioration due to an unsustainable paradigm of construction works [27]. According to the Report on the State of the Environment (2009–2012), although particulate pollution in China has reduced to a lower level (see Table 1), over 85% of 74 major cities still have a PM10 concentration higher than the baseline specified in the Ambient Air Quality Standard. For instance, in Beijing, the average monthly contribution of construction dust to the overall PM10 pollution was around 10% [28]. Dust emissions in some places of Shanghai accounted for 12.4% of air particles [29]. In Guiyang, which is supposed to be an ecological city in Southwest China, the proportion is surprisingly 24.89% as measured by fugitive dust [27].

Table 1.

PM10 concentration in China.

Many attempts have been made by China’s governments to control CDE in the industry. The Guideline of Green Construction issued by the central government specifies areas that are suitable to apply technologies to mitigate dust pollution. The advent of modern technology facilities enables contractors to sustain flexibility in selecting advanced measures to mitigate construction dust pollution. Typically, construction site enclosure, road pavement, materials covering, water cleaning, tight transportation, and tree planting are extensively adopted on construction sites [14]. These measures vary significantly in nature, but they are widely valued in protecting the natural environment and enabling the efficient use of production factors (e.g., materials, water, energy, and land). By far, over 80% of construction sites utilize technological means to control CDE in Suizhou city of Hubei province [30]. The extensive usage of technologies allows 95% of construction vehicles to have minor impacts on Linyi city of Shandong province [31].

Interestingly, notwithstanding the improvement of CDE control, the majority of Chinese contractors has a weak willingness to input more resources for this practice [21]. As discussed above, governments at this time ought to undertake the obligation of formulating preventative measures. The Law on Prevention and Control of Atmospheric Pollution [32] promulgated by the central government outlines a dust-free commitment in paragraph 2 of article 43. According to this law, the construction sector should be under strict supervision, and the role of local governments in this matter is to formulate standards and specifications. In Beijing, the local government enforced the Regulation on Prevention of Construction Dust Emission on Construction Sites [33], which requires property developers to engage contractors to mitigate dust emissions, especially in demolition and removal projects [34]. In addition, participants in the construction process are advocated to take collective actions in the attainment of zero-dust construction, and residents will be rewarded with some bonuses if their reporting of construction dust pollution is confirmed [35]. To summarize, cities in China have accumulated considerable experiences in coping with construction dust pollution. The rich experiences might be useful for other developing countries to consider to improve their practice.

3. Literature Review

3.1. Rationale for Governments’ Involvement

Whilst governments are highly expected to get involved in the control of construction dust emission, little has been informed about why governments shall take part in, and how government can do better. According to the Agenda 21 for Sustainable Construction in Developing Countries [36], governments act as an agent for public interests in the attainment of sustainable development. One of the most effective ways for them is by virtue of institutional arrangements, which could be either social or environmental. In the area of construction dust, institutional arrangements refer to the supervising behaviors of individuals and organizations, providing institutional guarantees, and stimulating technological innovation [37,38]. The key to these institutional arrangements is embracing a holistic approach to restoring and maintaining harmony between the natural and built environment [39]. However, this is far beyond the capability of a construction firm, and the institutional arrangements will be ineffective if contractors are not highly motivated. Hence, it is crucial that governmental measures are able to enhance contractors’ recognition, awareness, attitudes, and performance in the implementation of construction dust control.

Different governments have different stances on the choices of policies to decrease CDE [40]. Quite often, they formulate and promote policies that are in line with their ideological preferences [41,42,43]. The stringency of formulating environmental standards varies across geographical regions, and with the severity of environmental issues and the environmental awareness of stakeholders [44]. Therefore, local governments in developed regions may enforce environmental regulations more actively, while less developed regions may prioritize economic development and have weaker enthusiasm for implementing environmental policies [45]. In addition, population growth urges governments to devise and implement stricter environmental regulations [46]. Furthermore, institutional inefficiency would prevent governments from implementing environmental policy measures as well [47]. As pointed out by Vowles [48], those institutions with strong power and authority have a better position from which to develop and enact policies to reduce environmental pollution.

Institutional guarantees for social undertakings are concerned with some widely accepted rules and regulations [49,50]. The United Kingdom (UK) implemented a regulation called Raising the Bar 18: Control of Dust, in which contractors are required to satisfy minimum requirements to remove health threats and environmental nuisance from activities that produce dust [51]. Employers in developed countries are recommended to follow a protocol that includes plans, organization, control, monitoring, review, respiratory personal equipment, and a fit test. Similarly, governments in developing countries might use legislation systems to inhibit contractors from dust emissions in construction projects. It seems to be that measures for local governments to mitigate CDE can be taxation, subsidization, regulations, education, training, and guidance.

3.2. Existing Measures

Construction dust emissions are all-pervading environmental pollutants that have drawn closer attention from many cities around the world. Yakima, a United States (US) city, lists all of the possible dust emission challenges in its Construction Dust Control Policy of the Yakima Regional Clean Air Agency [52], and requires agencies and non-profit social organizations to address any of the challenges that lie ahead. Occupational Safety and Health Administration in the US includes some permissible exposure limits to dust that contains crystalline silica [53]. The Control of Substances Hazardous to Health Regulations [54] requires employers in the construction sector to immunize their employees and the surrounding area from hazardous substances.

The effectiveness of dust control measures is partly determined by using a well-developed technological system in which governments are the supporters of technical innovation and application [55]. In appraising 11 emission processes (e.g., open-air storage and transportation) and 11 businesses that produce fugitive dust (e.g., the manufacturing and processing industries of cement, lime, plaster, and cement-related products, and the construction industry), the Seoul Metropolitan Government established installation standards for facilities and measures to control fugitive dust [8]. The Aylesbury Vale District Council [56] requires contractors to build an intelligent storage yard sprinkling system to track dust concentration in the atmosphere, as well as its velocity, wind direction, temperature, and humidity. The monitor sends signals to the control system to determine when to sprinkle and at what speed. In addition, technical approaches to reducing dust exposure include an exhaust ventilation system, wet dust suppression, and personal protective toolkits (e.g., reusable respirators) [57]. Technologies of these kinds are largely created by contractors. However, the creation is characterized by uncertainty and much financial burdening, which can in turn hinder contractors from applying technologies. In reverse, contractors would be more willing to replace the dry sweeping system with a central vacuum if they receive either the technical or financial support of governments [58].

As shown in Table 2, previous studies have offered a range of measures for governments to tackle the pollution of construction dust [37]. The identified measures span from giving requirements to developing indicators for assessment. Whilst the extant literature on dust pollution control has elaborated contractors’ behaviors and governmental policies [24,59], the scope and attributes of the measures that governments select are deficient. It seems that institutional arrangements have not adequately absorbed the full range of governmental measures.

Table 2.

Existing measures in the literature.

4. Research Methods

The whole research process is separated into two phases. One is proposing a framework of governmental measures by using a number of research methods. The other is testing the proposed framework by analyzing a number of samples. First, raw materials such as government documents, media reports, and academic literature are collected to propose a tentative list of governmental measures in China. Second, the list is complemented by virtue of interviews and field study. Third, with reference to the work system in macroergonomics, all of the measures are categorized into groups. Fourth, 37 cities of China are compiled to develop a dataset of potential measures and calculate their utilization frequency. Last, the methods of content analysis and corresponding analysis are conducted to map out data to test the proposed framework.

4.1. Proposing a Framework of Measures

In considering that different governments might adopt different measures, a hybrid of research methods was carried out to outline potential measures. First, official documents publicized by provincial governments or above were collected and scanned carefully. Media reports on the measures that governmental authorities are currently using were retrieved. Since the measures identified in previous steps might be out-of-date, three experts (see Table 3) were interviewed with the purpose of adding necessary amendments to the tentative list. The respondents were considered appropriate because they are typical and offer professional insights from three perspectives, namely: governmental authority, academia, and practitioners. All of the interviewees had good knowledge and experience in construction dust management. The interview revolved around two questions: Does the list provide a whole picture of measures for governments to control construction dust emissions? If not, what are your suggestions? Notes were taken immediately and treated as quantization and evaluation of the tentative list of governmental measures.

Table 3.

Profiles of the interviewees.

Field study was also executed to look at whether those items to which interviewees have opposed opinions should be included. It was considered that any opposed items observable on construction sites deserved inclusion. As listed in Table 4, three construction projects were visited. These projects were visited because they are managed by construction enterprises that have good reputations and good performance on construction dust control in the construction industry. Governmental measures on dust pollution in these projects were thoroughly recorded. Project managers and site professionals were invited to make a necessary revision to the results derived in previous steps.

Table 4.

Profiles of surveyed projects.

As a result, nine items were added and coded from M23 to M32, as shown in Table 5.

Table 5.

Measures added from the Chinese construction industry.

These measures are concerned with the technique and management aspects of construction dust control. To capture the inherent complexity and understand key aspects of the measures, a framework is proposed by referring to the work system in macroergonomics. Macroergonomics integrates principles and perspectives from industrial, work, and organizational psychology, and helps understand the key factors within the work system [67]. The basic work system of macroergonomics includes the technical subsystem, organizational and managerial structure, internal environment, personnel subsystem, and the external environment [68]. As given in Table 6, the framework in the present study is more restricted and specific than macroergonomics, yet it provides a map of China’s practical experiences in construction dust control. The framework is composed of five groups, namely technology (15 items), economy (four items), supervision (four items), organization (three items), and assessment (six items).

Table 6.

Categories of the potential measures.

4.2. Samples

Samples are determined carefully for data mapping in order to test the measures proposed in Table 6. To increase the representativeness of samples, regional centers of China are included. In addition, those cities where the construction industry has been experiencing rapid development (e.g., Qingdao, Xiamen, Shenzhen, Weinan, Ningbo, and Shaoxing) are also considered. Consequently, the sample collected is composed of 37 major cities, as shown in Table 7.

Table 7.

Information about the sampled cities.

As many regulations published on governmental portal sites, news from local authoritative media, and research papers about the sampled cities as possible were collected. It is noted that all of the 37 cities have enforced provisions on the control of dust pollution, and 24 cities have their own initiatives.

In China, governmental portals are an important channel to inform citizens of public services. Based on Chinese government public information online, together with an official platform of the Urban and Rural Construction Committee and Environmental Protection Agency, a total of 345 documents are compiled. The derived documents are listed under the following headings in governmental portals: (1) Regulations on air pollution prevention and control; (2) Procedures for implementing the administration of city appearance and environmental sanitation; (3) Provisions on the prevention and control of dust pollution; (4) Regulations on construction field management; and (5) Scheme of dust pollution prevention and control on construction sites. In addition, a number of regulatory documents elaborating some minority measures (e.g., sediment transportation, ready-mixed concrete, sewage charges) that local governments adopt are also targeted.

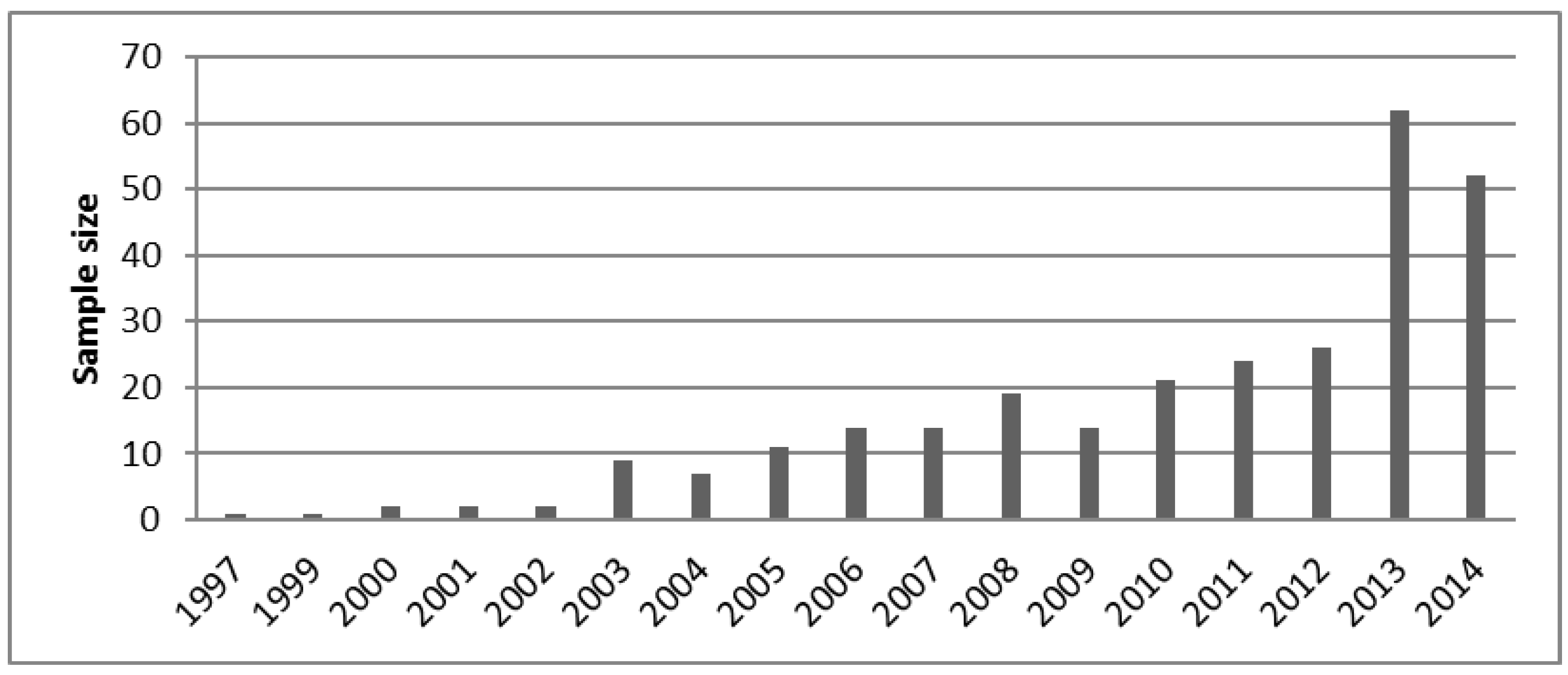

Out of 345 documents, 281 belong to headings (3) and (5), while the remainder is given under the headings (1), (2), and (4). In appreciating their connection to the subject of this study, those documents under the headings of (3) and (5) are given detailed examination. This part of documents spans over the period of 1997–2014 (see Figure 1), which mirrors governmental sharpened efforts in the past years. The project types described in the documents encompass buildings, infrastructures, and demolition works. Moreover, there are 56 acts of local governments and 225 regulations circulated by municipal construction committees or environmental protection agencies.

Figure 1.

Sample distribution.

4.3. Data Analysis

4.3.1. Content Analysis

Content analysis is an analytical technique that makes inferences by identifying specified characteristics of messages objectively and systematically [69]. In the present study, the method of content analysis was conducted, namely (1) identifying “construction dust” per regulatory document; (2) identifying dust control measures per regulatory document; (3) counting the frequency of measures in a sample city; and (4) totalizing the number of cities that use a defined measure. To avoid subjectivity as well as information omission, these steps were cross-checked by different team members using Nvivo (version 8.0). Nvivo is a useful research tool that helps classify, organize, analyze, and summarize qualitative data; it offers a way of working with and facilitating the search for particular features within the data [70,71]. All of the materials were examined in detail to ensure that no information was left out. By following these steps, the reliability and validity of content analysis results can be confirmed.

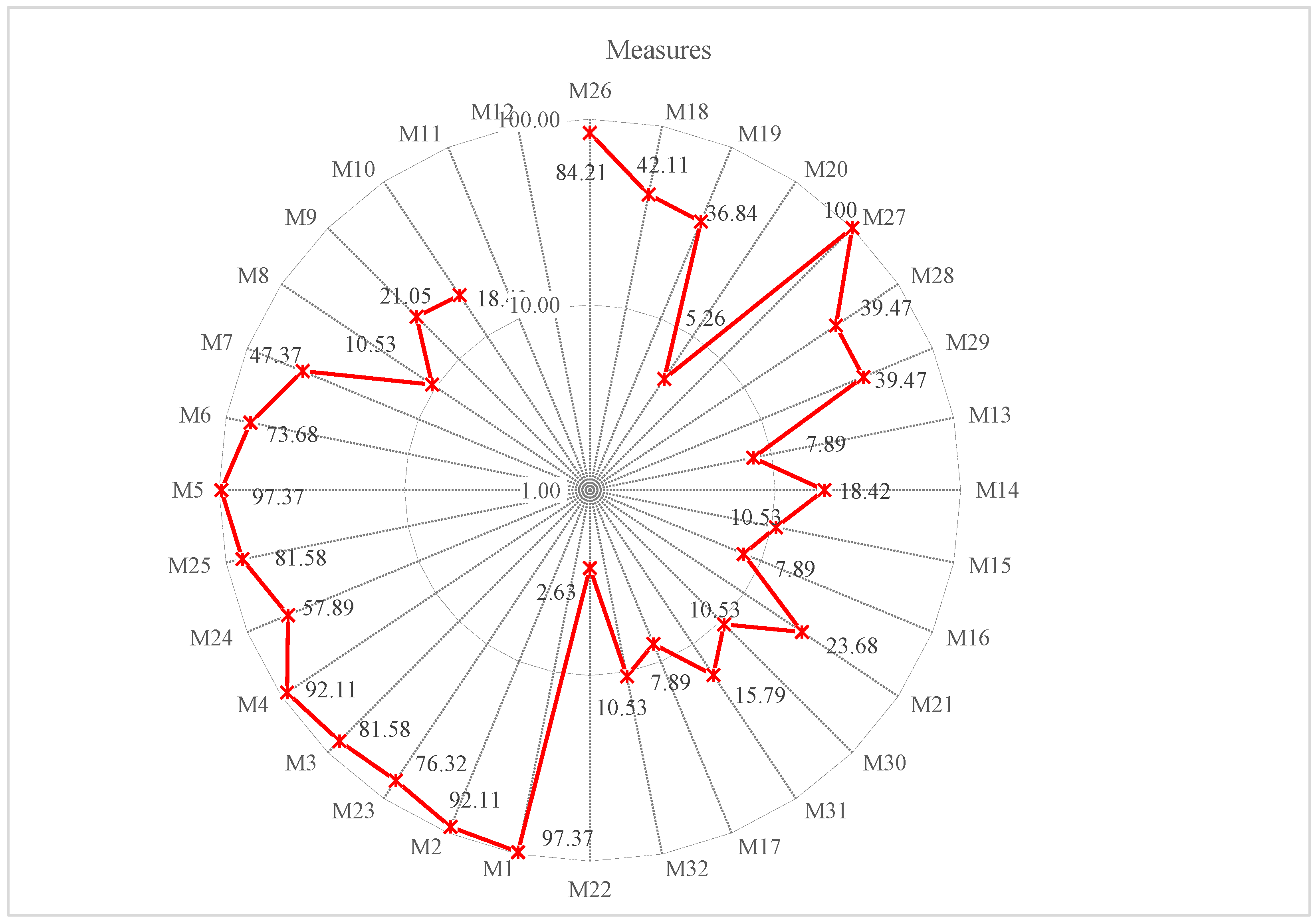

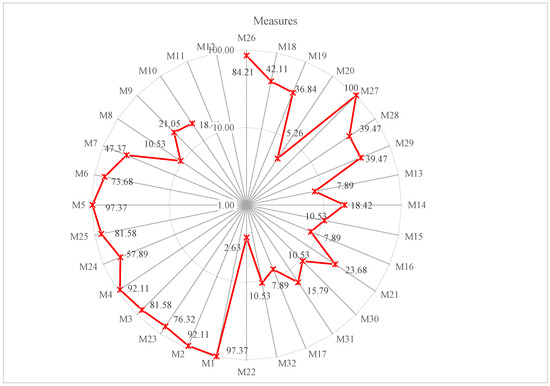

The frequencies of all of the measures are calculated and shown in Figure 2. It was found that 30 measures have been practiced in China. In particular, M27 (mass media supervision) has the highest frequency, and the most popular category is technological measures. Meanwhile, there are two measures that do not enter into the decisions of China’s governments.

Figure 2.

Frequency of the measures.

4.3.2. Correspondence Analysis

Correspondence analysis (CA) is an interdependence technique for dimensional reduction and perceptual mapping [72,73]. Hill [74] used CA to identify those species that are preferential to certain types of habitat. Hoffman and Franke [75] applied CA to develop preferred solutions for an energy crisis. In this study, therefore, CA was employed to identify governmental tendencies in the determination of construction dust control measures. In effect, this approach is useful to extract a continuous axe of variations from abundant data [76]. The total inertia explained by the axes retained reflects the accuracy of the lower dimensional space representation. The first two principal axes account for major variations in the original data, which can give rise to dimension reduction [77]. A graphical representation is obtained by plotting the first two columns of F (representing row points) and G (representing column points). The resulting plot facilitates simultaneous analysis of associations among rows, among columns, and between rows and columns. Thereby, the potential relationships among variations can be derived [78].

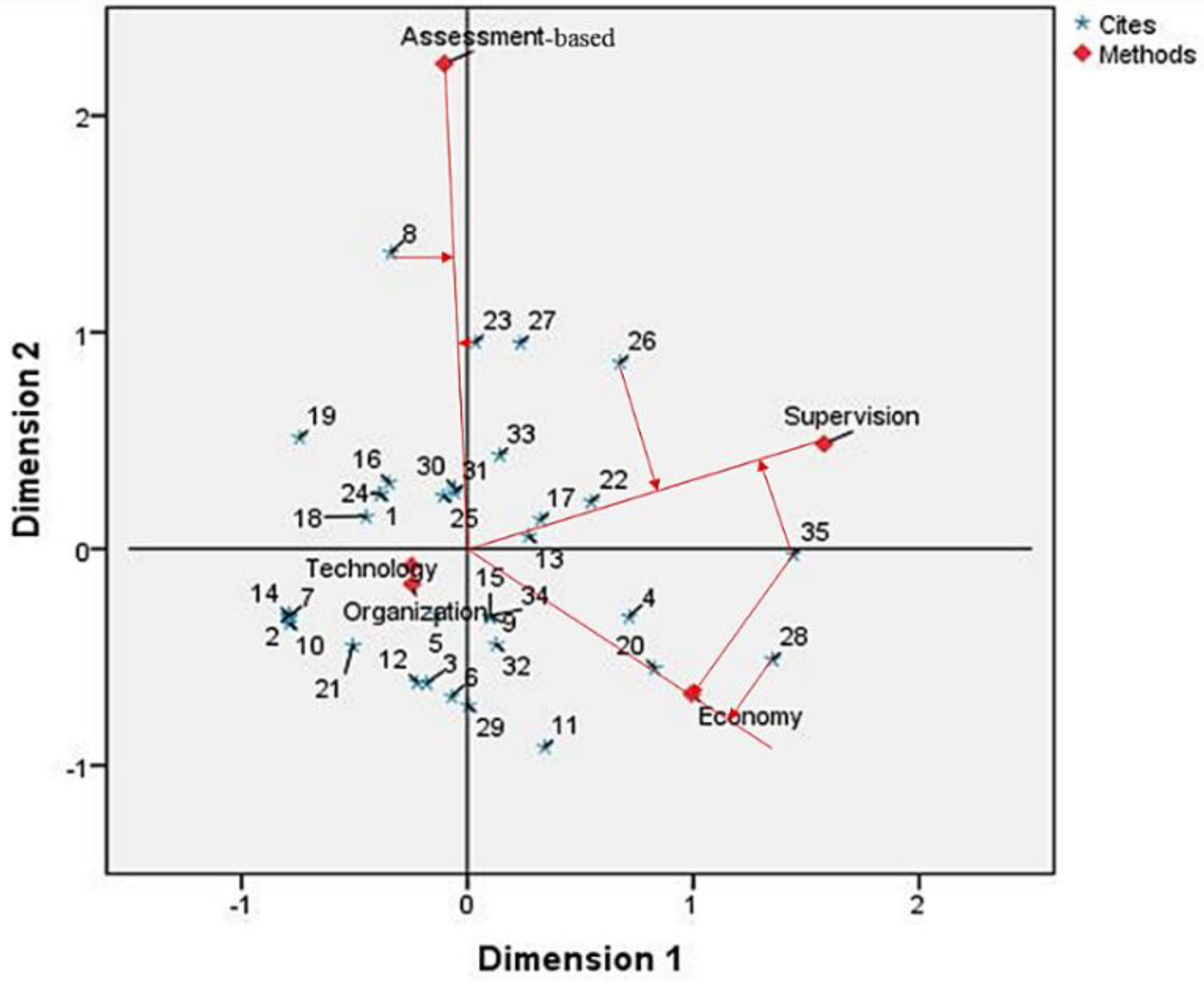

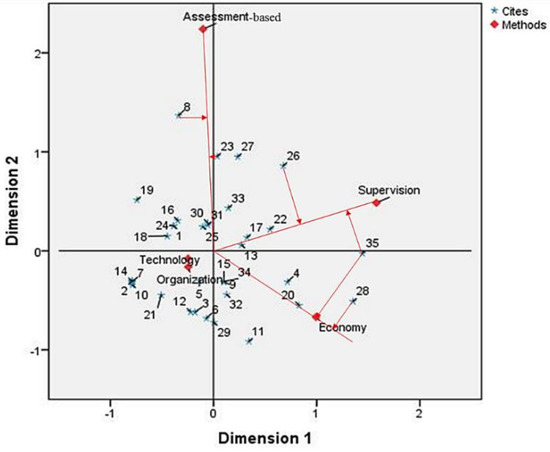

First, the data extracted are typed into Microsoft Excel spreadsheets with all of the samples coding from 1 to 37 with an ascending order based on gross domestic product (GDP) per capita. Specifically, 1 represents the least developed city, and 37 stands for the most developed city. Second, the Excel spreadsheet is imported into SPSS. Finally, CA is conducted to reduce the data into lower dimensions, and four dimensions are obtained, as shown in Table 8. The first and second dimension account for 77% of the variance in the total, suggesting that these two dimensions are sufficient to interpret major variations in the data.

Table 8.

Summary of correspondence analysis results.

In Figure 3, each point represents a city and it is labeled by a code to indicate city development status. If two cities are located further on the map, it means that they have greater variance in the choice of measures.

Figure 3.

Results of correspondence analysis.

5. Findings and Discussion

5.1. Framework of the Measures

The frequencies illustrated in Figure 2 show that all of the five categories have been adopted in China, suggesting that the proposed framework composed of technology, economy (four items), supervision (four items), organization (three items), and assessment (six items) are acceptable for governments to manage CDE in the construction sector.In effect, Table 6 indicates that previous studies on construction dust control place much emphasis on the choices of technology. One of the main reasons can be that technology measures are able to guide contractors to reduce dust emissions in a straightforward way, and their effects are thus easier to observe and testify. Relatively, economic, supervisory, organizational, and assessment-based measures are less applied in the construction industry. In China, governments bear the responsibility of overseeing contractors to improve environmental performance in construction projects. Shepherd and Woskie [67] revealed that drilling, sawing, chipping, and grinding concrete in the construction industry generate inhalable crystalline silica, which is a serious hazard for on-site workers. Governments’ response to this issue is to prohibit field concrete and mortar (M5).

Media can be used to publicize contractors who violate the rules. In effect, it plays an important role in supervising and inspecting contractors to comply with regulations. Both interview and field study indicate that M5 is frequently used and becomes part of ordinary work processes. It was found that contractors are requested to apply local exhaust ventilation (M11) to decrease construction dust emissions. Nonetheless, M11 has some limited applications on construction sites, and it has attracted less attention from television, radio, newspapers, and magazines. The interviews also reveal that this measure has not widely been applied due to cost and labor-intensive attributes. A similar situation exists for M12 (requiring respiratory protection). Respiratory protection is an effective way to reduce exposure, and it has been widely used in developed countries (e.g., the United States, Australia). Some provincial governments in China require respiratory protection on construction sites, and the media is expected to advertise the importance and benefits of respiratory protection. However, its application is not so extensive in the construction sector. According to the interviewees, this is because that the protection tool disturbs workers’ job on sites.

5.2. Categories of the Measures

5.2.1. Technological Measures

Table 6 tabulates 15 technological measures. The results suggest that nine of them are broadly applied, namely M1 (requiring enclosure construction), M5 (the prohibition of field concrete and mortar), M2 (requiring vehicle washing), and M4 (requiring rational material stacking or storage). These nine measures are very popular in reality. For instance, the inclusion of M1 is attributable to its effectiveness in inhibiting the spread of fugitive dust, minimizing construction noise, and improving the semblance of construction sites [79]. M5 mirrors the long-time endeavors of governments to embed technological measures in construction dust practices. In 2003, the Commerce Ministry of China issued a regulation about the prohibition of field concrete in 124 cities with the joint efforts of other ministries including Communications, Construction, and Public Security. Four years later, 10 major cities (e.g., Beijing) banned the adoption of field concrete and mortar. As of today, the use of ready-mix concrete and mortar has become mandatory nationwide.

Figure 3 offers a relatively high frequency of technological measures in application, which concurs with the literature shown in Table 2. However, the differences in these kinds of measures between China and western countries can be appreciated. The measures of M8–M12 are of little concern in China (see Figure 2), while M9 (applying windbreaks hedge) is growing in popularity in Japan, Germany, and America [80,81]. Likewise, the use of M11 (applying local exhaust ventilation, LEV) may remove the contaminant as generated at the source. As pointed out by Hallin [82], LEV is an ordinary approach to reduce silica and repairable dust exposure in developed countries.

5.2.2. Economic Measures

Economic measures refer to economic instruments that motivate contractors to mitigate the emission of construction dust. As given in Table 6, this kind of measure encompasses administrative sanction, special funds, budget management, and sewage charges. In particular, governments will possibly conduct administrative sanctions (M26) if contractors’ behaviors are under an administrative violation. By comparison, less application of either M19 or M20 might be because they are newly established and more time is needed to embrace them in practice.

A few cities (i.e., Nanjing and Xuzhou) have charged fees for disposing dust pollutants on construction sites since 2009. In fact, recent years have witnessed an expansion of governmental interests in this measure worldwide. For instance, the National Green Tribunal of India requires contractors to pay a fee to compensate for environmental pollution in accordance with their building plot sizes, according to the Hindustan Times [83]. The Hawaii government announced that stakeholders should pay dust control costs using a lump-sum price, as defined in contracts [84].

5.2.3. Supervisory Measures

Supervision is another useful means for governments to use in the control of construction dust emissions. The likeliness of contractors performing dust control would be higher if governmental supervision was exerted effectively. In the UK, for instance, an authorized responsible person is assigned by the Portsmouth City Council to check construction control work and supervise workers’ jobs to ensure that dust control measures are effectively implemented [85].

Table 6 indicates three supervisory measures, namely the media, the public, and the third party that governments can consider. However, by comparison, it is found that mass media supervision (M27) is more attentive in China, while video monitoring (M28) and measuring complaints from the mass (M29) have not received much attention. This could be true, as numerous events about contractors’ unethical or irresponsible behaviors are often reported by the news media. Furthermore, only a minority of Chinese governments require construction contractors to accept third-party supervision (M13) such as construction-supervising engineers, the client, and a special oversight panel.

5.2.4. Organizational Measures

Organizational measures refer to those arrangements devised by governments in order to involve contractors in controlling dust emissions. The scope of organizational measures contains assigning responsibilities among governmental authorities, establishing a joint conference system, and conducting education or training exercises. As shown in Table 6, three measures are extracted under this category with a slight variation of application from one city to another. It seems that establishing the dust proof bureau/steering group (M14) and a joint conference system (M15) have been used more frequently in China (see Figure 3). Basically, M14 spells out the responsibilities of primary stakeholders (e.g., main contractors, sub-contractors, the client, and consultants); M15 assumes the shared responsibilities of different governmental offices such as environmental protection, transportation, construction management, and public security in monitoring contractors’ dust emissions.

Contractors would dislike changing if their actions were impeded by predetermined procedures [86]. Hence, governments may treat offering education and training (M16) to construction project management teams as a necessary instrument. This not only helps deliver relevant technologies to employers, it also shows them both dust risks and ways to protect themselves from pollution [85]. To summarize, organizational measures are instrumental in driving contractors to implement a zero-dust scheme.

5.2.5. Assessment-Based Measures

Assessment-based measures serve to provide feedback to governments on contractors’ activities by assessing their dust control performance on sites. As listed in Table 6, six measures are grouped. Embracing dust emission as a key performance indicator of local government (M30) opens a window to oversee overall dust emission in the AEC sector while “combining dust emissions into green construction initiatives” (M21), “embedding dust control into a national credit system for construction business” (M31) and “prioritizing dust control in assessment-based environmental impact” (M17) elaborate a couple of ways of measuring the performance of construction firms in mitigating dust pollution. As indicated by these measures, construction firms’ grades should be disqualified if their track records in dust emission practices were unsatisfactory in the past.

Furthermore, the measure “being a performance indicator of the client” (M22) highlights the participation of the client in dust control in the construction process. Assessment measures emerge in less 25% of the samples, suggesting a relatively low frequency of application. This might be the case because the literature shown in Table 6 does not place much emphasis on them.

5.3. Tendency of Governmental Measures

As shown in Figure 3 most of the cities scatter distribute around the points of “technology” and “organization”. This implies that China’s governments have a common inclination to the approaches of construction dust control. Governmental measures may fall into two technological categories. One is extant measures that may be adopted prior to dust generation. An initiative of green construction using those materials that have in nature the ability to emit less dust presents a good example of this. In addition, a prototype concept based on computer-aided engineering simulation proposed by Wallace and Cheung [87] might be a useful technological means for governments to consider. The other refers to exposure measures that are applicable after dust generation, such as fencing, suppression by water infusion or wet cutting, dilution by the ventilation system, and mitigation by water sprays and scrubbers [88].

Technological measures are of limitations in application. Fencing has the weak strength of reliving the harm of dust to frontline workers. Wet dust suppression is a convenient approach, but it necessitates more labor input and increases construction cost [7]. Apart from those measures, equipment such as filter cartridge supported by cyclone technology to retrieve dust is often used in practice. However, it has poor efficiency, and still has some problems with energy consumption [89]. In addition, Figure 3 illustrates that only two samples (i.e., cities 28 and 35) are preferred to economic measures, and City 8 relies more on assessment-based measures. Furthermore, the untidy distribution of city numbers indicates that governmental preference on the choices of measures varies little with the development of economies. Instead, some other factors such as the awareness, attitudes, and experience of governments might dominate the selection, but this is open for further examination in the future.

5.4. Enlightenment of Governmental Measures’ Scope and Tendency

Understanding the scope and tendency of construction dust control measures favors governments to reap expected benefits. As discussed above, the technological measures encompass both preventive and end-of-pipe solutions. The other four types of measures have some relationships with the effectiveness of technological measures. They are used to guarantee the successful application of technologies as well as the awareness of contractors in promoting technological innovation. For instance, Zhou et al. [90] pinpointed that the introduction of regulations without the promotion of technological innovation will slow down economic growth. Thus, organizational measures function as institutional guarantees for technological innovation and help define governmental responsibilities properly.

In addition to technological measures, governments are apt for organizational approaches in order to enhance the efficiency of dust control. Nowadays, both developed and developing countries are frequently challenged by a diversity of environmental pollutants, which calls for an effective application of governmental measures. However, this is subject to obstacles in some countries (e.g., Japan and China) such as a high transaction cost and lack of applicable methodologies [91]. Feng and Liao [92] conducted a comprehensive review of the legislation, plans, and policies for air pollution prevention, and found that the current legislation has deficiencies such as a lack of stipulation, unclear governmental responsibilities, and a low penalization of violators. As pinpointed in previous studies, governments are better engaged with developers, contractors, and the public in forming a temporary organization to monitor construction dust pollution [14].

6. Conclusions

Severe environmental pollution resulting from construction dust emissions has attracted a majority of governments to consider what they do better in the attainment of sustainability. Dust control is one of the largest challenges in the area of sustainable construction that governments often urge contractors to address. It is crucial that a combination of measures be adopted to handle this public matter instead of merely employing an individual approach. With reference to China’s practices, the measures are found to be technological, economic, organizational, supervisory, and assessment-based. These five categories of measures form a conceptual framework for other countries to consider using or as a basis for reconsidering their own processes. In addition, China’s governments are inclined to use the measures of technologies and organization to encourage contractors to reduce construction dust emissions. To this end, considerable efforts should be made to stimulate technological innovation and provide institutional guarantees toward dust-free construction.

This paper contributes to the body of knowledge by mapping out China’s experiences in the past decades and presenting the tendencies of governments regarding relevant practices. The research findings lay a solid foundation for future studies to explore the effectiveness of all of the identified measures. The research can assist governments in enhancing their understanding of construction dust control and promoting dust-free construction in the construction industry. Although research works are situated in China, the findings provide useful references for those countries that have similar problems with construction dust pollution to implement. Future research is recommended to explore the rationale behind governmental decision-making on the choices of the measures.

Data Availability Statements

Data generated or analyzed during the study are available from the corresponding author by request.

Author Contributions

K.Y. designed the research and provided guidance in the research process; J.X. conducted a literature review, collected data and wrote the original draft; W.J. and J.Z. conducted to analyze data and interpret results. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by Fundamental Research Funds for the Central Universities, grant number 2018CDJSK03 PT16; and Graduate Research and Innovation Foundation of Chongqing, grant number CYS18054.

Acknowledgments

The authors are grateful to Jian Wang and Bo Yang for their participation in data collection.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Shen, L.Y.; Tam, V.W.Y.; Tam, L.; Ji, Y.B. Project feasibility study: The key to successful implementation of sustainable and socially responsible construction management practice. J. Clean. Prod. 2010, 18, 254–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, T.; Lim, H.; Kim, C.W.; Lee, D.; Cho, H.; Kang, K.I. The Accelerated Window Work Method Using Vertical Formwork for Tall Residential Building Construction. Sustainability 2018, 10, 456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, F.; Ye, B.; He, K.; Ma, Y.; Cadle, S.H.; Chan, T.; Mulawa, P.A. Characterization of atmospheric mineral components of PM2.5 in Beijing and Shanghai, China. Sci. Total Environ. 2005, 343, 221–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Song, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Xie, S.; Zeng, L.; Zheng, M.; Salmon, L.G.; Shao, M.; Slanina, S. Source apportionment of PM2.5 in Beijing by positive matrix factorization. Atmos. Environ. 2006, 40, 1526–1537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steenland, K.; Mannetje, A.; Boffetta, P.; Stayner, L.; Attfield, M.; Chen, J.; Dosemeci, M.; Deklerk, N.; Hnizdo, E.; Koskela, R. Pooled exposure-response analyses and risk assessment for lung cancer in 10 cohorts of silica-exposed workers: An IARC multicentre study. Cancer Causes Control 2001, 12, 773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Partanen, T.; Jaakkola, J.; Tossavainen, A. Silica, silicosis and cancer in Finland. Scand. J. Work Environ. Health 1995, 21 (Suppl. 2), 84. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Gambatese, J.A.; James, D.E. Dust Suppression Using Truck-Mounted Water Spray System. J. Constr. Eng. Manag. 2001, 127, 53–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noh, H.J.; Lee, S.K.; Yu, J.H. Identifying Effective Fugitive Dust Control Measures for Construction Projects in Korea. Sustainability 2018, 10, 1206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chisholm, J. Respirable Dust and Respirable Silica Concentrations from Construction Activities. Indoor Built Environ. 1999, 8, 94–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Zhu, Y.; Zhang, Z. An LCA-based environmental impact assessment model for construction processes. Build. Environ. 2010, 45, 766–775. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Construction Dust an Industry Survey. The Heart of Safey and Health, 2014. Available online: www.iosh.co.uk (accessed on 16 July 2016).

- Maciejewska, A. Occupational exposure assessment for crystalline silica dust: Approach in Poland and worldwide. Int. J. Occup. Med. Environ. Health 2008, 21, 1–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yassin, A.; Yebesi, F.; Tingle, R. Occupational Exposure to Crystalline Silica Dust in the United States, 1988–2003. Environ. Health Perspect. 2005, 113, 255–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, Z.; Zhang, X.; Wu, M. Mitigating construction dust pollution: State of the art and the way forward. J. Clean. Prod. 2016, 112, 1658–1666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lumens, M.E.; Spee, T. Determinants of exposure to respirable quartz dust in the construction industry. Ann. Occup. Hyg. 2001, 45, 585–595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shehu, Z.; Endut, I.R.; Akintoye, A.; Holt, G.D. Cost overrun in the Malaysian construction industry projects: A deeper insight. Int. J. Proj. Manag. 2014, 32, 1471–1480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wolfstetter, E. Topics in Microeconomics: Industrial Organization, Auctions, and Incentives; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 1999; pp. 328–329. [Google Scholar]

- Yandle, B. Emerging Property Rights, Command-and-Control Regulation, and the Disinterest in Environmental Taxation; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2002; pp. 225–241. [Google Scholar]

- Cho, H.D.; Lee, J.K.; Ro, K.K. Environment and technology strategy of firms in government R&D programmes in Korea. Technovation 1996, 16, 553–560. [Google Scholar]

- Russell, J.; Skibniewski, M. A Structured Approach to the Contractor Prequalification Process in the USA. CIB-SBI Fourth International Symposium on Building Economics. Available online: https://catalogue.nla.gov.au/Record/433985/Copyright? (accessed on 8 August 2018).

- Zuo, J.; Rameezdeen, R.; Hagger, M.; Zhou, Z.; Ding, Z. Dust pollution control on construction sites: Awareness and self-responsibility of managers. J. Clean. Prod. 2017, 166, 312–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Z.; Li, H.; Wong, C.T.C. Environmental Management of Urban Construction Projects in China. J. Constr. Eng. Manag. 2015, 126, 320–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wallis, R.K. 24–Modern rammed earth construction in China. Modern Earth Build. 2012, 3, 688–711. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, N. The role of the construction industry in China’s sustainable urban development. Habitat Int. 2014, 44, 442–450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, R.; Ma, K.; Zhang, Y.; Mao, Q. The spatial characteristics and pollution levels of metals in urban street dust of Beijing, China. Appl. Geochem. 2013, 35, 88–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, K.; Shen, L.; Zuo, J. Utilizing the linkage between domestic demand and the ability to export;to achieve sustainable growth of construction industry in developing;countries. Habitat Int. 2013, 38, 135–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, W.; Wang, X.; Liu, Z.; Zhang, Y.; Min, S.; Cheng, Q.; Degang, W.U. Construction Fugitive PM_(10) Emission and Its Influences on Air Quality in Guiyang. Acta Sci. Nat. Univ. Pekin. 2009, 46, 258–264. [Google Scholar]

- Zhao, X.Y. Construction Fugitive Dust Pollution and Control in Beijing. J. Beijing Univ. Technol. 2007, 33, 1086–1090. [Google Scholar]

- Shi, Q.; Xu, Y.; Chen, S. Green Construction Alternatives Evaluation Using GA-BP Hybrid Algorithm. In Proceedings of the 2009 International Conference on Management and Service Science, Wuhan, China, 20–22 September 2009; pp. 1–5. [Google Scholar]

- The Effectiveness of Construction Dust Control in Suizhou. Suizhou Building and Construction Committee, 2015. Available online: http://www.szzjw.gov.cn/html/xinwenzhongxin/jianshexinxi/20150826/1919.html (accessed on 14 May 2016).

- 90% of Construction Site Do Well in Dust Control. Linyi Building and Construction Committee, 2015. Available online: http://linyi.house.qq.com/a/20160920/013973.htm (accessed on 14 May 2016).

- Central Government of China. Law on Prevention and Control of Atmospheric Pollution; Central Government of China: Beijing, China, 2015.

- Beijing Construction Committe. Regulation on Prevention of Construction Dust Emission on Construction Sites; Beijing Construction Committe: Beijing, China, 1999.

- Construction Dust Control is a Must for Green Construction. Beijing Construction Committee, 2015. Available online: http://news.cq.fang.com/2015-03-27/15304520.htm (accessed on 14 May 2016).

- Take Photo for Construction Dust. Zhengzhou Building and Construction Committee, 2015. Available online: http://news.sina.com.cn/o/2015-10-21/doc-ifxizetf7729830.shtml (accessed on 14 May 2016).

- Reffat, R.M. Sustainable construction in developing countries. In Proceedings of the First Architectural International Conference, Cairo, Egypt, 24–27 December 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Fraser, E.D.G. Coping with food crises: Lessons from the American Dust Bowl on balancing local food, agro technology, social welfare, and government regulation agendas in food and farming systems. Glob. Environ. Chang. 2013, 23, 1662–1672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharratt, B.; Auvermann, B. Dust Pollution from Agriculture. In Encyclopedia of Agriculture & Food Systems; Elsevier: New York, NY, USA, 2014; pp. 487–504. [Google Scholar]

- Du Plessis, C. A strategic framework for sustainable construction in developing countries. Constr. Manag. Econ. 2007, 25, 67–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamieniecki, S. Political Parties and Environmental Policy; Duke University Press: Durham, NC, USA, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Alesina, A. Macroeconomic policy in a two-party system as a repeated game. Q. J. Econ. 1987, 102, 651–678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hibbs, D.A. Political parties and macroeconomic policies and outcomes in the United States. Am. Econ. Rev. 1986, 76, 66–70. [Google Scholar]

- Hibbs, D.A. Political Parties and Macroeconomic Policy. Am. Political Sci. Rev. 2006, 100, 670–671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Fu, X. FDI and environmental regulations in China. J. Asia Pac. Econ. 2008, 13, 332–353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Wheeler, D. Financial incentives and endogenous enforcement in China’s pollution levy system. J. Environ. Econ. Manag. 2005, 49, 174–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lantz, V.; Feng, Q. Assessing income, population, and technology impacts on CO2 emissions in Canada: Where’s the EKC? Ecol. Econ. 2006, 57, 229–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, C.P.; Berdiev, A.N. The political economy of energy regulation in OECD countries. Energy Econ. 2011, 33, 816–825. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vowles, J. Does globalization affect public perceptions of ‘Who in power can make a difference’? Evidence from 40 countries, 1996–2006. Elect. Stud. 2008, 27, 63–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rizaldi, A. Control Environment Analysis at Government Internal Control System: Indonesia Case. Procedia Soc. Behav. Sci. 2015, 211, 844–850. [Google Scholar]

- Engel, K.H. Whither Subnational Climate Change Initiatives in the Wake of Federal Climate Legislation? Publius 2009, 39, 432–454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UK Government. The Delivery Hub Health, Safety and Environment Raising the Bar 18; High Way Agency, Ed.; UK Government: London, UK, 2013.

- Construction Dust Control Policy of the YAKIMA Regional; Clean Air Agency: Yakima, WA, USA, 2013.

- OSHA Is Developing New Proposed Rules Regulating Silica Dust. Available online: https://www.yakimacleanair.org/img/pdf/112.pdf (accessed on 12 October 2017).

- McLean, A. Control of Substances Hazardous to Health Regulations; Department of Health: London, UK, 1991.

- Zhang, H.; Wang, S.; Hao, J.; Wang, X.; Wang, S.; Chai, F.; Li, M. Air pollution and control action in Beijing. J. Clean. Prod. 2016, 112, 1519–1527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aylesbury Vale District Council. Available online: https://www.aylesburyvaledc.gov.uk/ (accessed on 10 May 2017).

- Tjoe, N.E.; Hilhorst, S.; Spee, T.; Spierings, J.; Steffens, F.; Lumens, M.; Heederik, D. Dust control measures in the construction industry. Ann. Occup. Hyg. 2003, 47, 211–218. [Google Scholar]

- Lehtinen, J.; Koski, H.; Enbom, S. The Central Vacuum System on the Renovation Site; Strong-Finland Oy: Vantaa, Finland, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Xue, W.; Wang, J.; Niu, H.; Yang, J.; Han, B.; Lei, Y.; Chen, H.; Jiang, C. Assessment of air quality improvement effect under the National Total Emission Control Program during the Twelfth National Five-Year Plan in China. Atmos. Environ. 2013, 68, 74–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farhang, A.-K.; Sheryl, A.M.; Cynthia, D.W.; Michael, S.B.; April, L.A.; Sadik, K.; Pam, S.; Mahboubeh, A.-K. Effectiveness of Dust Control Methods for Crystalline Silica and Respirable Suspended Particulate Matter Exposure During Manual Concrete Surface Grinding. J. Occup. Environ. Hyg. 2010, 7, 700–711. [Google Scholar]

- Shepherd, S.; Woskie, S.R.; Holcroft, C.; Ellenbecker, M. Reducing silica and dust exposures in construction during use of powered concrete-cutting hand tools: Efficacy of local exhaust ventilation on hammer drills. J. Occup. Environ. Hyg. 2009, 6, 42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thorpe, A.; Ritchie, A.S.; Gibson, M.J.; Brown, R.C. Measurements of the effectiveness of dust control on cut-off saws used in the construction industry. Ann. Occup. Hyg. 1999, 43, 443–456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, L.; Pei, Z. Preparation and Optimization of a Novel Dust Suppressant for Construction Sites. J. Mater. Civ. Eng. 2017, 29, 04017051. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weidman, J.; Dickerson, D.E.; Koebel, C.T. Intervention to Improve Purchasing Decision-Maker Perceptions of Ventilated Tools. J. Constr. Eng. Manag. 2015, 141, 04015007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van, D.E.; Pronk, A.; Spaan, S.; Goede, H.; Tielemans, E.; Heederik, D.; Meijster, T. Quartz and respirable dust in the Dutch construction industry: A baseline exposure assessment as part of a multidimensional intervention approach. Ann. Occup. Hyg. 2014, 58, 724–738. [Google Scholar]

- Serpell, A.; Kort, J.; Vera, S. Awareness, actions, drivers and barriers of sustainable construction in Chile. Technol. Econ. Dev. Econ. 2013, 19, 272–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shepherd, S.; Woskie, S.R. A Case Study to Identify Barriers and Incentives to Implementing an Engineering Control for Concrete Grinding Dust. J. Constr. Eng. Manag. 2010, 136, 1238–1248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, D.; McCoy, A.P.; Kleiner, B.M.; Smith-Jackson, T.L.; Liu, G. Sociotechnical Systems of Fatal Electrical Injuries in the Construction Industry. J. Constr. Eng. Manag. 2016, 142, 268–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holsti, O.R. Content Analysis for the Social Sciences and Humanities; Addison-Wesley Pub. Co.: London, UK, 1969; pp. 137–141. [Google Scholar]

- Tom, R. An intellectual history of NUD*IST and NVivo. Int. J. Soc. Res. Methodol. 2002, 5, 199–214. [Google Scholar]

- Wong, F.W.H.; Chan, E.H.W.; Yu, A.T.W. Property Developers’ Major Cost Concerns Arising from Planning Regulations under a High Land-Price Policy. J. Urban Plan. Dev. 2011, 137, 112–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carroll, J.D.; Green, P.E.; Schaffer, C.M. Interpoint Distance Comparisons in Correspondence Analysis. J. Mark. Res. 1986, 23, 271–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Charnes, A.; Miller, M.H. A Model for the Optimal Programming of Railway Freight Train Movements. Manag. Sci. 1956, 3, 74–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hill, M.O. Correspondence Analysis: A Neglected Multivariate Method. J. R. Stat. Soc. 1974, 23, 340–354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoffman, D.L.; Franke, G.R. Correspondence Analysis: Graphical Representation of Categorical Data in Marketing Research. J. Mark. Res. 1986, 23, 213–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braak, C.J.F.T. Canonical Correspondence Analysis: A New Eigenvector Technique for Multivariate Direct Gradient Analysis. Ecology 1986, 67, 1167–1179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, Q.; Brusgaard, K.; Kruse, T.A.; Oakeley, E.; Hemmings, B.; Becknielsen, H.; Hansen, L.; Gaster, M. Correspondence analysis of microarray time-course data in case-control design. J. Biomed. Inform. 2004, 37, 358–365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kudlats, J.; Money, A.; Hair, J.F., Jr. Correspondence analysis: A promising technique to interpret qualitative data in family business research. J. Fam. Bus. Strategy 2014, 5, 30–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, P.; Feng, Y.; Zhu, T.; Wu, J. Characterizations of resuspended dust in six cities of North China. Atmos. Environ. 2006, 40, 5807–5814. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takahashi, S.; Du, M.; Wu, P.; Maki, T.; Kawashima, S. Three dimensional numerical simulation of the flow over complex terrain with windbreak hedge. Environ. Model. Softw. 1998, 13, 257–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilson, J.D. Numerical studies of flow through a windbreak. J. Wind Eng. Ind. Aerodyn. 1985, 21, 119–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hallin, N. Occurrence of Quartz in the construction Sector; an Investigation of the Occurrence of Quartz Dust in Connection with Various Operations in the Construction Sector; Elsevier Science Ltd.: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 1983. [Google Scholar]

- Odusote, O.O.; Fellows, R.F. Buildings over 20,000 sq m to Pay R5 Lakh for Dust Pollution. Available online: https://www.hindustantimes.com/delhi-news/buildings-over-20-000-sq-m-to-pay-r5-lakh-for-dust-pollution/story-IiXnMSZbVAo2YT6FEHiF5K.html (accessed on 10 April 2017).

- Dust Control; Hawaii Department of Transportation, Hawii Government: Honolulu, HI, USA, 2013.

- Construction Dust; Health and Safety Executive, Ed.; UK Government: London, UK, 2015.

- Acquaye, A.A.; Duffy, A.P. Input–output analysis of Irish construction sector greenhouse gas emissions. Build. Environ. 2010, 45, 784–791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wallace, K.A.; Cheung, W.M. Development of a compact excavator mounted dust suppression system. J. Clean. Prod. 2013, 54, 344–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Executive, S. CIS 54 (Rev1) Dust Control on Cut-Off Saws Used for Stone or Concrete Cutting; Health and Safety Executive: Bootle, UK, 2010.

- Ahn, Y.C.; Jeong, H.K.; Shin, H.S.; Yu, J.H.; Kim, G.T.; Cheong, S.I.; Lee, J.K.; Kim, C. Design and performance evaluation of vacuum cleaners using cyclone technology. Korean J. Chem. Eng. 2006, 23, 925–930. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Q.; Yabar, H.; Mizunoya, T.; Higano, Y. Exploring the potential of introducing technology innovation andregulations in the energy sector in China: A regional dynamic evaluation model. J. Clean. Prod. 2016, 112, 1537–1548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, B.; Mauerhofer, V.; Geng, Y. Analysis of existing building energy saving policies in Japan and China. J. Clean. Prod. 2015, 112, 1510–1518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, L.; Liao, W. Legislation, plans, and policies for prevention and control of air pollution in China: Achievements, challenges, and improvements. J. Clean. Prod. 2017, 112, 1549–1558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

© 2018 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).