1. Introduction

The term ‘sustainability’ has evolved from a 1990s buzzword into a core principle of policy-making in both advanced and emerging democracies. Not only non-governmental organizations (NGOs) active in the field have embraced it, but policy-makers and political parties have done so as well [

1]. While public and political attention regarding the question of sustainability declined in the 2000s, the adoption of the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) in 2015 once more placed the issue firmly on the political agenda of countries worldwide [

2]. The new global sustainability agenda is more ambitious in its targets, and seeks to reach beyond the achievements of the Millennium Development Goals (MDGs) [

3]. While the SDGs set out goals and targets in seventeen fields of action, SDG 2 concentrates on ending hunger, attaining food security, and improving nutrition. Importantly for the purposes of this article, it also calls for the promotion of sustainable agriculture. Considering the various stresses on agriculture today, the call to make this sector more sustainable is both reasonable and necessary.

Having a well-functioning agri-food system is vital for every society—even the most affluent ones—and in light of current conditions, appropriate policy measures are necessary to ensure that agriculture is also sustainable [

4,

5,

6]. Indeed, among the most pressing challenges in this sector is the need to produce food for a growing global population and address shortages in vital resources such as water; conflicts over land use (also a consequence of expanding biofuels production) [

7]; soil degradation [

8]; environmental contamination due to intensive agricultural practices (i.e., the use of agro-chemicals) [

9]; and biodiversity loss [

10,

11]. Furthermore, we must also deal with the various impacts of climate change [

12]. The hot, dry summer of 2018 has shown Europeans how vulnerable they are to shifting climatic conditions. This unusual weather not only devastated crops (especially in southern Europe), but also sparked discussions about whether surface water should be extracted at all for the purpose of irrigation [

13].

The interdependencies between agriculture policy and other policy domains such as climate, energy, environment, and health have helped to accommodate concerns originating from neighboring policy domains in agriculture policy [

14,

15]. This process—also known as the ‘integration’ or ‘nexus’ approach [

16,

17]—is ongoing, and varies in the manifestations appearing both between and within countries (e.g., at the subnational level or across individual policy domains). Despite this abstract commitment to integrating agriculture policy with environmental concerns, when examining actual policy decisions the degree of policy integration is often limited, or even absent entirely [

18].

The clash between the ultimate goal of sustainable agriculture and current agriculture policy is epitomized by the 2017 renewal of the authorization for glyphosate—an active ingredient of some broad-spectrum herbicides [

19]—by the member states of the European Union (EU). The decision to extend the authorization period of glyphosate for another five years was not reached easily, and for a long period the member states failed to deliver an opinion on this issue in the relevant decision-making body: namely, the Standing Committee on Plants, Animals, Food and Feed (PAFF). This in turn led the European Commission to alter both its position on the matter and to approach the member states, offering them a shorter authorization period than initially planned. A sufficiently clear stance was adopted by the member states in the end, which allowed for a renewal of the authorization for a period of five years.

In this study, we pursued two objectives related to the renewal of glyphosate authorization in the EU: First, we examined the decision-making process and how it was possible to avoid (the potential of) a ‘no opinion’ scenario. Second, we sought to understand how the member states—those opposing or supporting the authorization’s renewal—have endeavored to cope with the result, and what policy measures they have adopted (if any). To that end, we focused our analysis on France, Germany, and the Netherlands—three member states that voted differently on the Commission’s proposal to renew glyphosate authorization—employing the methodology of process tracing, which draws on the analysis of various types of documents, to reconstruct the relevant actors’ decisions. The dual analytical perspectives on the EU-level decision-making process and how policy-makers in the selected member states dealt with the voting outcome represents a novel contribution to the literature on policy-making under ambiguity in the EU’s multi-level political system.

EU decision-making on glyphosate contains features similar to that regarding genetically modified organisms (GMOs), with voting in the relevant standing committee and appeal body likewise having culminated in ‘no opinion’ outcomes. There is in fact a direct link between GMOs and glyphosate: the active ingredient in ‘Roundup’—the dominant herbicide used in agriculture, produced by the agro-chemical company Monsanto (recently bought out by Bayer)—is glyphosate [

20]. Most GM crops are resistant to Roundup (or herbicides produced by other agro-chemical companies), rendering glyphosate an integral component of their cultivation. Monsanto sells Roundup along with its GM seed crops and, in the market of glyphosate producers, remains the dominant company [

21], although many others offer a generic product containing the substance. When farmers utilize GM crops sold by Monsanto, they have no choice but to buy and use Roundup by contractual obligation. The market power of Monsanto was an issue in the European glyphosate debate, with the news media reporting that the company had influenced the risk assessment carried out by the competent authorities.

In the first part of this study, therefore, we offer a brief overview of GMO regulation in the EU in order to identify similarities and differences. Subsequently, we develop a theoretical argument to explain the features of decision-making at the EU level, as well as decision-making in the member states following the renewal of glyphosate authorization. The next section provides an overview of the EU decision-making process, which is followed by an analysis of how the French, German, and Dutch governments have reacted to the authorization’s renewal. Despite having voted differently on the proposal to renew authorization, each of the governments concerned is facing a situation in which there are influential political and societal groups both supporting and opposing glyphosate, hence complicating the domestic policy-making process. In the final section, we summarize our findings and provide concluding remarks.

2. Comparing the Politics of GMOs and Glyphosate

Before a decision was reached on renewing the authorization for glyphosate as an active substance in late November 2017, the European Commission was repeatedly confronted with ‘no opinion’ votes. In the case of such a result, neither the rejection nor the acceptance of a regulatory proposal is permitted. The Commission has frequently experienced such ‘no opinion’ votes on proposals related to the (re)authorization of GMOs [

22]. The parallel voting outcomes can be explained by the similarity of both comitology procedures [

23] and the differences in opinion on the part of member states regarding both issues.

The comitology procedure for the (renewal of) authorization of GMOs and active substances includes the following steps [

22,

24,

25,

26]: First, a company submits an application to an EU member state. That member state—termed the ‘rapporteur member state’—is then tasked with the initial scientific and technical evaluation of the GMO or active ingredient concerned, and prepares an assessment report that is in turn submitted to the European Food Safety Authority (EFSA). In consultation with other member states, EFSA carries out a peer review of the assessment report and sends its conclusions to the European Commission. Based on that review, the European Commission makes a proposal on whether or not to approve the GMO or active substance considered. A standing committee composed of representatives from all EU countries then votes on the Commission’s proposal. The competent standing committee is the PAFF for glyphosate, and the Standing Committee on the Food Chain and Animal Health (SCFCAH) for GMOs.

If the Committee accepts the proposal by a qualified majority, it takes effect; if the proposal is rejected, it fails. Should the Committee fail to reach a qualified majority on the dossier (i.e., a ‘no opinion’ vote), the Commission may submit the draft implementing act to the Appeal Committee for further deliberation. The Appeal Committee is a procedural tool that gives the member states an opportunity to review the matter at a higher level of representation. If the Appeal Committee accepts the decision by a qualified majority, it takes effect; if the Committee indicates by a qualified majority that it opposes the proposal, the Commission may re-examine the draft and resubmit an amended one. However, in the event that the Appeal Committee fails to reach a qualified majority, the Commission can adopt the proposal. Once adopted, authorization is granted for a fixed period of up to ten years.

The EU authorized a number of GM crops until the mid-1990s, but some governments then began to change their positions on GMOs [

22]. France (because of its voting power) was the most influential member state to transition from a pro-GMO to anti-GMO stance, a shift accompanying the entry into office of the left-wing government led by Prime Minister Lionel Jospin, which also included the anti-GMO Green Party [

27]. The accession of Austria in 1995 likewise helped to bolster the anti-GMO camp, further altering the ratio between the two groupings with regard to voting power [

22]. In 1998, skeptical governments reacted to the authorization of GM crops by signing a declaration asking the Commission to set out rules ensuring the labeling and traceability of GMOs. Otherwise, it was made clear, new authorizations of GMOs would be suspended [

28].

While this de facto moratorium ended in May 2004, the stalemate between GMO supporters and opponents continued. To break that deadlock, the Commission proposed a Regulation amending the legal basis (Directive 2001/18/EC) in 2010 [

22]. The corresponding Directive 2015/412 was eventually adopted in 2015, and now officially allows member states to opt-out from the authorization of GMOs [

26].

Compared to the GMO example, the first EU approval of glyphosate in 2002 went rather smoothly, with the chemical authorized on the basis of Commission Regulation (EEC) No 3600/92 (as amended) for a period of ten years. The renewal of the authorization for glyphosate is governed by Regulation (EC) No 1107/2009 of the European Parliament and Council concerning the placing of plant protection products on the market. On that legal foundation, the Commission first proposed to the member states that they renew the approval of glyphosate in 2016, but there was insufficient support for the proposal—either in favor or against. We will look into this decision-making process in detail in the subsequent sections.

As shown above, according to EU rules both GMOs and glyphosate are governed by a similar procedure when it comes to (the renewal of) authorization. Voting on each in the competent standing committees—the PAFF and SCFCAH, respectively—and Appeal Committee produced ‘no opinion’ outcomes. The reasons underlying these voting results are similar, with GMOs and glyphosate both associated with uncertainty with regard to their potential adverse effects on humans and the environment [

20,

29]. Some member states have therefore resorted to the precautionary principle in order to justify their opposition to the Commission’s (re)authorization proposals [

22,

30]. According to the European Commission [

31], this principle can be invoked when a product or process has a potentially dangerous effect, and if a scientific and objective evaluation is not able to determine that risk with sufficient certainty. In reality, however, the application of the precautionary principle is determined by the dynamics of the relevant political process. Sometimes its application is accepted by the European Commission, and in other instances it is challenged [

32].

Despite numerous similarities between the politics of glyphosate and GMOs, there is one important distinction: GMOs are cultivated in very few member states (most prominently in Spain), and they are not critical for agri-food production in the EU as a whole [

29]. The situation is markedly different for glyphosate, which is used widely in conventional farming throughout Europe, and not only with GM crops [

33,

34]. Moreover, it has been deployed extensively for non-agricultural purposes as well, from weed control on the part of municipalities in urban areas to gardening. Such extensive use has generated concern among European authorities regarding, for example, the contamination of groundwater and surface water [

9]. From that perspective, the controversy surrounding glyphosate directly relates to issues of human health, environmental protection, and weighing the economic benefits of pesticides against the health and environmental costs associated with their use. This topic is therefore likely to generate much more internal division within EU member states compared to GMOs.

This difference in relevance and actors involved in the policy-making process, we hypothesize, explains not only the controversy among the member states in the context of EU decision-making, but also the policy measures adopted within them following the renewal of the relevant authorization.

3. Theoretical Argument

In this study, we are interested in explaining the policy decisions taken following the renewal of the authorization for glyphosate. Of course, domestic decision-making is affected by how member states vote at the EU level, and in the context of glyphosate voting in the PAFF and Appeal Committee was preceded by negotiations among the political parties forming each individual government, with domestic politics kicking in once more after agreement was reached at the EU level. More precisely, we are interested in understanding why political actors disagree on how to address glyphosate, and how that disagreement in turn affects policy-making. To understand this, we must take into consideration the

expected benefits and costs of using—or banning—glyphosate;

uncertainty associated with assessing these two parameters (i.e., costs and benefits);

and the influence of organized interests [

35,

36].

Given the widespread use of glyphosate in conventional agriculture, a ban on the substance is likely to impose additional costs on farmers [

37]. As a result, the political discourse on this topic has unsurprisingly been affected by interest groups representing the farming sector. The United Kingdom Farming Unions [

38], for example, published an open letter in which the signatories stated that “European farmers need glyphosate to provide a safe, secure and affordable food supply while increasingly responding to consumer demand for greater environmental sensitivity.” This statement is notable, as it suggests that a rise in food prices (due to labor increases and added time) is likely to follow in the wake of a glyphosate ban. In other words, a policy-maker not only needs to take the additional costs imposed on farmers into account, but also those falling on consumers—a significantly larger group.

On the other hand, there have also been new revelations concerning glyphosate, and policy-makers must factor these in as well—either when assessing the expected costs of using the chemical or the expected benefits of banning it. As detailed by Myers et al. [

20], the principal scientific insights can be summarized as follows: glyphosate has been found to contaminate drinking water sources and soil, and the World Health Organization’s International Agency for Research on Cancer (IARC) has classified glyphosate as a probable human carcinogen. When taking this information into account, and the consequent uncertainty regarding glyphosate, the cost-benefit analysis becomes more complicated and brings interest groups representing environmental and health-related concerns to the fore.

Another element that must be accounted for when it comes to domestic policy-making is that the consequences of banning glyphosate are discussed (controversially) in terms of the availability of alternatives, their effectiveness, and their characteristics with regard to human and environmental risks and hazards. Do alternatives exist, and for what types of agriculture? Are their risks indeed lower than those attributed to glyphosate? These are questions that are now hotly debated among scientists [

39], and yet policy-makers must now decide—in a reliable manner—on a future regulatory regime. In this context, the latter can be expected to abstain from changing the rules of the game too often and without good reason.

Given these features, we anticipate that domestic policy-making processes in the member states will resemble each other—both in member states that opposed the renewal of glyphosate and in those that supported it. Even member states that sought to ban the substance must take all of the above considerations into account when designing a national regulatory regime. Meanwhile, the persisting uncertainty in accessing the benefits and costs of glyphosate use provide an opportunity structure for interest groups to further influence the stance of policy-makers.

A more accurate means to conceive of the uncertainty in this particular instance is ambiguity. According to Brugnach et al. [

40], ambiguity is a type of uncertainty resulting from the simultaneous existence of multiple approaches to framing a problem. In the case of glyphosate, the risks associated with the chemical are framed in very different ways by the various actors participating in the policy process. As described above, farmers’ associations and interest groups representing the agro-chemical industry will downplay risks and stress benefits, whereas environmental NGOs and groups working on the promotion of public health will place greater emphasis on risks while downplaying benefits. In decision-making, the existence of ambiguity is important as it can prevent the articulation of a solution to a policy problem. In such a situation, a problem cannot be characterized adequately. Rational choice theories of policy-making, in particular, stress the need for developing a sufficient understanding of a problem in order to be able to design policy solutions to it [

41].

The ambiguity of the phaseout options is likely to lead to an incremental policy-making scenario in which small-scale measures are proposed and implemented. Such incrementalism is associated with the classic work of Lindblom [

42,

43] on the “science of muddling through.” According to Lindblom, policy-makers often base policy solutions on partial knowledge and the prioritization of certain ‘values’ over others. The political process is conceived of as a game, whereby each interest group acts as a watchdog for its values and attempts to influence policy-makers accordingly. Each policy-maker, meanwhile, concentrates on one specific aspect of a policy problem. The participation of many decision-makers is therefore needed to guarantee that all interests are given adequate attention. Ultimately, the policy process is characterized by negotiation, bargaining, and compromise-seeking between policy-makers who represent specific values and interests [

44]. This can prevent major policy change.

4. The Renewal Process for Glyphosate

Glyphosate has been used in EU member states for many years. In Germany, for example, glyphosate has been authorized as a component of herbicides since 1974 [

45]. It was only in 2002, however, that glyphosate was first approved—for a period of ten years—according to EU rules on pesticides. Originally set to expire in 2012, this authorization was extended until the end of 2015 on the basis of Commission Directive 2010/77/EU. The period between 2012 and 2015 was used to carry out a scientific assessment of glyphosate by Germany (as the rapporteur member state) and EFSA (but in consultation with the other member states) as required by Commission Regulation (EU) No 1141/2010, and as amended by the Commission Implementing Regulation (EU) No 380/2013 [

46,

47]. The German Federal Institute for Risk Assessment provided its initial evaluation of the dossier, which was received by EFSA in December 2013. The peer review mechanism began in 2014, with the distribution of a report requesting consultation from the member states and the European Glyphosate Task Force, represented by Monsanto Europe S.A. [

47].

Towards the end of that period, the IARC had assessed glyphosate and concluded that it was “probably carcinogenic to humans.” This finding resulted in widespread concern over the substance and whether its authorization should be renewed, and induced the European Commission to provide EFSA with a mandate to consider the IARC findings with regard to the potential carcinogenicity of glyphosate in the ongoing peer review. In October 2015, EFSA [

47] concluded “that glyphosate is unlikely to pose a carcinogenic hazard to humans and the evidence does not support classification with regard to its carcinogenic potential according to Regulation (EC) No 1272/2008 on classification, labeling and packaging.” In its conclusion, however, EFSA identified a data gap to rule out the potential endocrine activity of glyphosate, which the agency had observed in one of the studies consulted [

48]. EFSA’s 2015 report was heavily criticized in 2017 as having been unduly influenced by Monsanto, with revelations that the assessment contained passages that had been directly lifted from Monsanto’s own documents [

49].

In light of EFSA’s conclusion, the Commission presented a proposal to the member states in early 2016 to renew the approval of glyphosate for 15 years, but this first attempt failed due to a ‘no opinion’ vote (European Commission 2017). In order to overcome the uncertainty regarding the chemical’s potential carcinogenicity, and the ensuing reservations on the part of some member states, the Commission gave a mandate to the European Chemicals Agency (ECHA) to assess the hazard properties of glyphosate before it continued the process of renewing approval for the substance. After asking ECHA for an additional scientific evaluation, the Commission went ahead and requested that the member states vote again on the renewal of glyphosate authorization in June 2016, resulting in yet another ‘no opinion’ vote. Left once more with this outcome, the Commission decided to extend the approval of glyphosate for six months after the receipt of the ECHA report (until 31 December 2017 at the latest). Around the same time, the member states supported the Commission’s proposal to amend the conditions for the existing approval of glyphosate, making them more restrictive to provide better protection for humans and the environment [

48].

As ECHA presented its opinion to the European Commission on 15 June 2017, it became clear that the approval of glyphosate would expire on 15 December 2017 unless authorization was renewed by the member states. In its report, ECHA’s [

50] Committee for Risk Assessment concluded that “current scientific evidence does not support the classification of glyphosate for carcinogenicity.”

Between May and October 2017, several discussions took place between the European Commission and the member states regarding the possible renewal of glyphosate. During this period, the findings of the EFSA [

51] study on the potential endocrine activity of glyphosate became available, which concluded that “the weight of evidence indicates that glyphosate does not have endocrine disrupting properties through oestrogen, androgen, thyroid or steroidogenesis mode of action based on a comprehensive database available in the toxicology area.” This conclusion by EFSA was factored into the updated version of the proposal presented by the Commission in October 2017. However, it was also during this period when revelations emerged in the news media that the 2015 EFSA opinion had been influenced by Monsanto [

49]. In this context, in October 2017 the Commission officially received the submission of a successful European Citizens’ Initiative calling for a ban on glyphosate, a change to the comitology procedure for approving active substances, and the setting of EU-wide mandatory reduction targets for pesticide use.

Figure 1 illustrates the support for the initiative among the individual member states [

52].

In its plenary session on 24 October, the European Parliament (which only plays a consultative role in the procedure to renew authorization—see

Section 2) adopted a resolution opposing the Commission’s proposal to renew the authorization of glyphosate. According to the European Parliament, the “Commission’s draft implementing regulation fails to ensure a high level of protection of both human and animal health and the environment, fails to apply the precautionary principle, and exceeds the implementing powers provided for in Regulation (EC) No 1107/2009” [

53]. It demanded a complete ban on glyphosate-based herbicides by 15 December 2022, with the adoption of earlier intermediate bans on use by households. In so doing, the European Parliament referenced the broad support for such a ban as evidenced by the European Citizens’ Initiative [

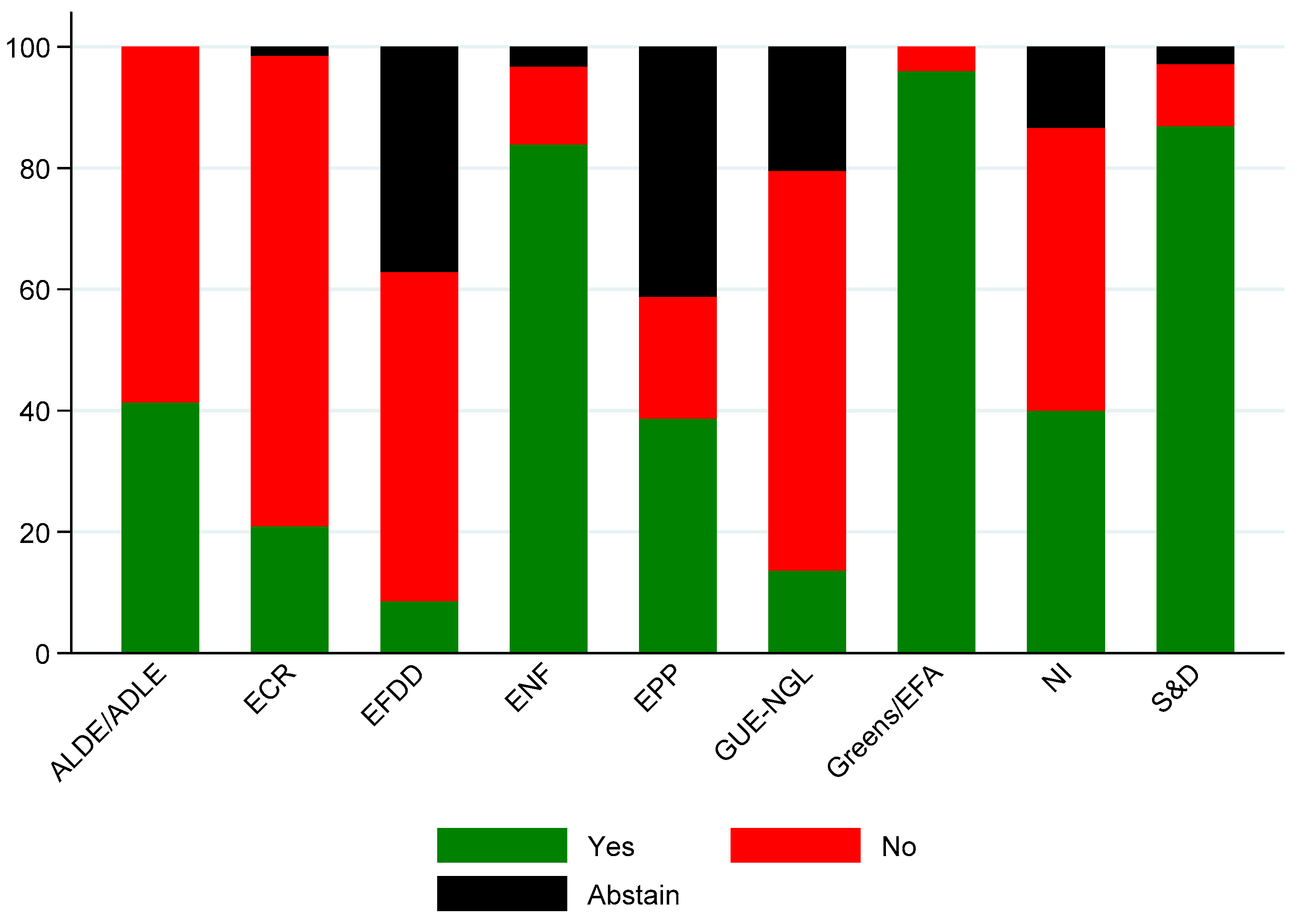

53]. The Members of the European Parliament adopted the text with 355 votes in favor of banning glyphosate, 204 against, and 111 abstentions.

Figure 2 provides an overview of these votes, broken down by the individual political groups of the European Parliament.

On 25 October 2017, the Commission held another round of discussions with the member states on the proposal to renew the authorization of glyphosate, and tested the waters for a shorter renewal period of ten, seven, and three years, respectively. No qualified majority seemed attainable for any of these options. Ten countries indicated that they would vote against a ten-year renewal, whereas sixteen delegates stated that they would vote in favor. The representatives of Germany, France, and Italy, meanwhile, maintained that they would support a three-year market authorization, with the French delegates arguing that “the short-term extension would allow time to find alternatives for the controversial [and] widely-used weed killer” [

54].

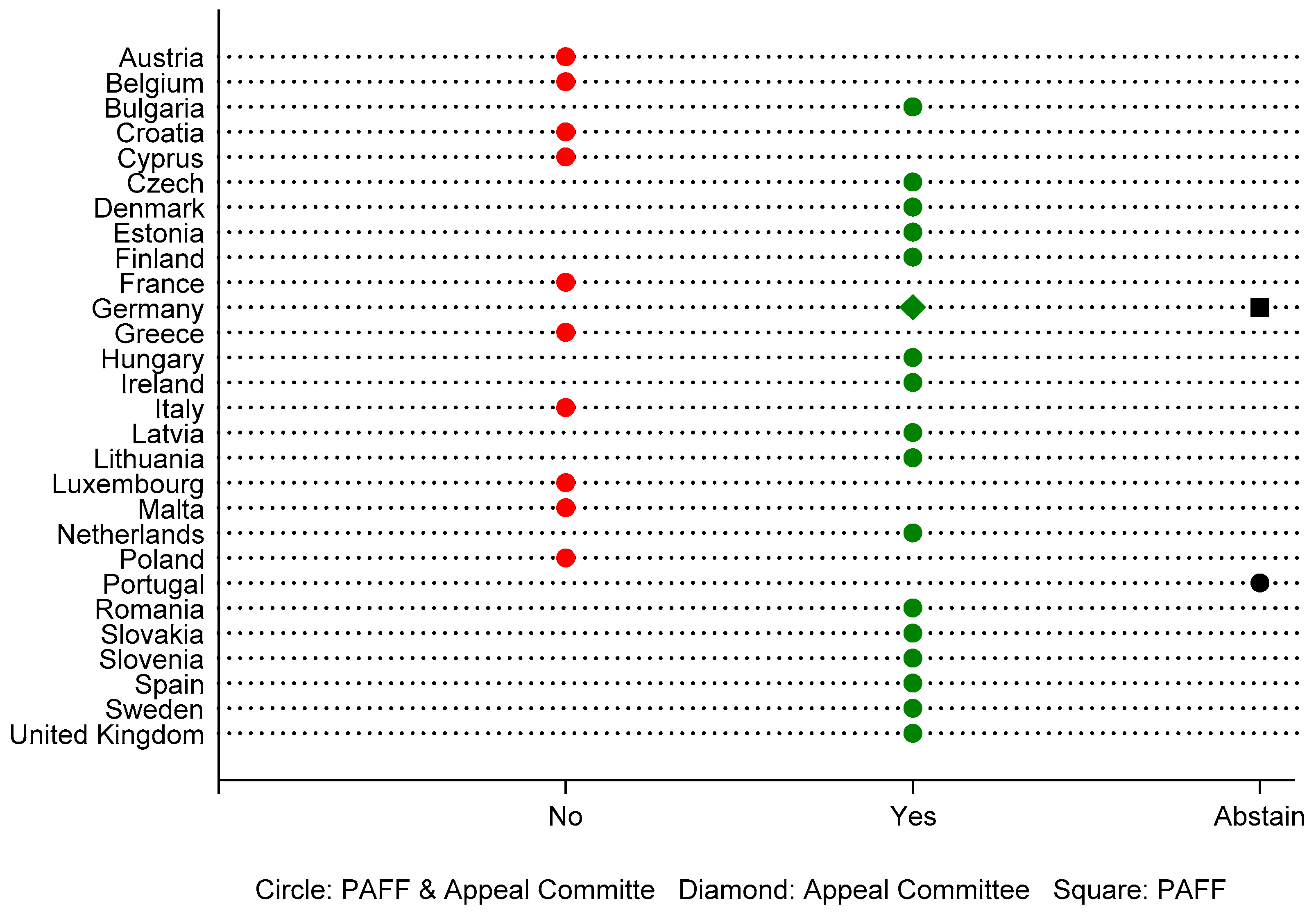

The views expressed during this round of discussions led the Commission to present another version of its proposal, this time for a five-year renewal period, with member state delegates casting their votes in the PAFF on 9 November 2017. As in previous rounds, the PAFF delivered a ‘no opinion’ outcome [

48]. Then, on 27 November 2017, the Appeal Committee returned a surprising result: a qualified majority in favor of the proposal. As shown by

Figure 3, this outcome was achieved because the German delegates changed their position and voted in favor of the proposal, rather than abstaining [

55]. On 12 December 2017, following years of discussion and controversy, and after four revisions, the Commission was finally able to adopt its proposal to renew the approval of glyphosate for five years. On the same day, it likewise adopted its response to the European Citizens’ Initiative [

24], which concludes that the Commission “has no basis to submit to the co-legislators a proposal to ban glyphosate.”

Nevertheless, the Communication reveals that the views of the European Parliament had been taken into account—along with the ongoing public and political controversy surrounding glyphosate in the various parts of the EU’s multi-level system—and that the period for the authorization’s renewal had been reduced as a consequence. Furthermore, on the same page of the Communication, the Commission states that it can review the approval of glyphosate should new scientific evidence emerge indicating that the chemical does not fully comply in light of the existing risk assessment. Lastly, the Commission points out that the member states may decide to introduce restrictions or bans on the use of the substance if they possess evidence related to the particular circumstances of their countries. We will explore the member states’ approaches to addressing the renewal of glyphosate authorization in the following section. Of greater importance for the present analytical step, however, is understanding why the German delegates changed their position on the Commission’s proposal.

Referring back to the example of GMO authorization, the German government has mostly abstained in these votes [

22]. This is due to the nature of the multi-party coalition governments that rule Germany, in which one party typically nominates the Minister of the Environment and another the Minister of Agriculture. There are exceptions to this rule. In 2009 and 2013, for example, the Minister of the Environment was a member of the Christian Democratic Union (CDU) and the Minister of Agriculture a member of the Christian Social Union (CSU)—the CDU’s Bavarian ‘sister party.’ Both ministers must agree on the vote they wish to cast in the competent standing committee and the Appeal Committee. If they cannot do so, they must abstain.

During the period of decision-making on the renewal of glyphosate authorization, German politicians were initially trying to form a coalition government between the CDU, CSU, Green Party, and Free Democratic Party (FDP) in the wake of the federal elections that had taken place on 24 September 2017. The attempts to form a coalition government between these four parties failed on 19 November 2017, and the Social Democratic Party (SPD) was at first hesitant to renew the prior coalition government with the CDU and CSU. The third cabinet of Chancellor Angela Merkel thus had to act as a caretaker government until 14 March 2018. The ‘hot phase’ of the glyphosate decision therefore coincided with the difficult period of government formation in Germany and the existence of a caretaker government there.

In the previous (regular) government, as well as in the caretaker government, Christian Schmidt (CSU) was Minister of Agriculture and Barbara Hendricks (SPD) Minister of the Environment. Already during the electoral campaign, Christian Schmidt had promised farmers that he would support the renewal of glyphosate authorization. In May 2017, the minister referred to the glyphosate controversy as a negative example of how political decisions can fail to take scientific evidence into account. He argued that the critics would not engage with the scientific findings on glyphosate, and that he would trust the assessment and scientific approach of the German Institute for Risk Assessment [

56]. According to news media information, the competent department in the Ministry of Agriculture recommended that the minister vote in favor of renewal as early as July 2017, even against the will of the Minister of the Environment [

57].

Nevertheless, it still came as a surprise when—during the vote in the Appeal Committee on 27 November 2017—Minister Schmidt asked the German delegates to vote in favor of the Commission’s revised proposal to renew authorization, despite the veto of Minister Hendriks. Germany was therefore pivotal in avoiding a ‘no opinion’ scenario [

54], and gave the Commission political legitimacy for the renewal of glyphosate authorization. The country’s ‘yes’ vote led to an outcry among SPD representatives, however, and even Chancellor Merkel (CDU) criticized Minister Schmidt for his behavior—further complicating the ongoing negotiations on the formation of a coalition government [

57]. While calls for Schmidt’s resignation from the caretaker government went unheeded, he was later replaced by Julia Klöckner (CDU) in the fourth Merkel cabinet, which entered into office on 14 March 2018.

On the website of the German Ministry of Agriculture, there is a section that explains why the country voted in favor of the European Commission’s proposal. According to this explanation, the Commission would have extended the authorization of glyphosate regardless of the voting outcome. By voting in favor of the proposal, it was argued, Christian Schmidt was able to enforce restrictions on glyphosate use that would not have been tenable had Germany abstained [

45]. It is difficult to say whether the Minister of Agriculture would have also voted in favor of the proposal under regular circumstances—that is, not during a period presided over by a caretaker government. However, the internal documents of the Ministry of Agriculture, to which news media such as

Süddeutsche Zeitung [

57] refer, indicate that the ‘yes’ vote in the Appeal Committee was prepared beforehand.

6. Conclusions

In the present study, we examined the renewal of glyphosate authorization in the EU and how the member states have reacted to this outcome. We have shown that the authorization’s renewal was possible because the German Minister of Agriculture decided to trust the risk assessment prepared by the competent German authority [

56], which also provided the basis for renewing the authorization at the EU level. Bearing in mind that Germany acted as the rapporteur member state on this particular issue, one can understand that the minister in question was under high pressure. Voting against, or abstaining on, the proposal would have indicated that the minister did not trust the German Federal Institute for Risk Assessment. As we have shown in the prior analysis, the minister was ultimately willing to follow scientific advice, despite criticism concerning the impartiality of the risk assessments delivered and against the will of the Minister of the Environment.

As a next step, we examined how the member states have reacted to the renewal of glyphosate authorization. While differing in their preferred outcomes (a ban vs. restrictions), the member states analyzed here have all attained incremental policy change at best. This outcome is related to different preferences on the part of policy-makers, which result from their relationships with the agriculture sector and agro-chemical industry, as well as their trust in the risk assessments presented by EFSA, ECHA, and domestic agencies. Given this decision-making context, it does not come as a surprise that ‘muddling through’ scenarios have been observed. Surprisingly, however, the member state with the most elaborate regulatory approach currently in place—namely, the Netherlands—voted in favor of the various proposals presented by the European Commission with regard to the renewal of glyphosate authorization. From our analysis of the Dutch case, it is clear that the adopted approach caters to different interests. This explains why the application of glyphosate outside of agriculture was banned, whereas its use by commercial farmers remains untouched. The French and German governments did not even get this far, despite their more ambitious regulatory preferences regarding glyphosate.

The question of how to address glyphosate will remain on the political agenda of both the European Commission and its member states. One reason for this is the extension of the authorization for only five years, which means that the issue will reemerge once the end of that period approaches. Indeed, when taking the negative public opinion of glyphosate into account [

24,

62], it may be even more difficult to convince a qualified majority of member states that the authorization should be extended again. This could become particularly challenging once the United Kingdom—a member state that voted in favor of renewing the authorization—leaves the EU, as this departure would alter the power constellation in the PAFF and Appeal Committee.

Secondly, environmental and other interest groups are continuing to draw attention to this issue, and at a certain point policy-makers will have to react. Whereas environmentalists demand a complete ban on glyphosate, farmers’ associations highlight the chemical’s value for their industry; while there is a divide between organic and conventional farmers [

77], the latter account for the largest share of agriculture in EU member states and continue to rely heavily on glyphosate. Thirdly, a potential ban on the substance would provide a business opportunity for the producers of alternative products, and they will consequently strive to keep the glyphosate debate on the political agenda. This perspective is particularly interesting, as it could well be business interests themselves that eventually push through a ban on the chemical. After all, it was French President Macron who repeatedly stated that the future of glyphosate depends on the availability of a “credible alternative,” as one could not leave farmers without a reliable solution [

63]. Lastly, litigation in the United States will also serve to shape the European political agenda in this area [

52].

Overall, the case of glyphosate demonstrates the need for a broader debate on what form agriculture should take in the future, and in what way it can be rendered more sustainable. We suggest that policy-makers reach out to the various stakeholder groups as well as the wider public and engage in an open dialogue about what is—and is not—possible and/or desirable. Concerning the future use of glyphosate, such a dialogue seems particularly needed now, as the clock is ticking when it comes to authorization and both farmers and consumers need to know what the future regulatory regime will look like. Given the EU member states’ relative homogeneity, their experience grappling with the questions surrounding the chemical suggests that this will not be an easy issue to resolve. It also indicates that the debate is likely to be even more controversial beyond Europe. In this context, there is a need today for more and enhanced analyses of glyphosate [

78]. We also invite future research to pay increased attention to SDG 2 and the political steps taken to promote more sustainable agriculture, and welcome further studies on the domestic national policy processes related to the regulation of glyphosate in the EU member states not covered by the present analysis. In the end, all member states will have to determine how best to address the substance in future, and what levels of uncertainty they are willing to accept concerning its potential hazards—both to humans and the environment.