Rethinking 21st-Century Businesses: An Approach to Fourth Sector SMEs in Their Transition to a Sustainable Model Committed to SDGs

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. From “Limits to Growth” to a “Sustainable Wellbeing Economy”: The Role of SMEs in the Transition toward 2030

3. Materials and Methods

- Phase 1: Profile definition and interviewees selection: Given the lack of literature on 4S SMEs, this phase was relevant for qualifying interviewees. The first step was to define interviewees’ profiles in order to comply with the research objectives. For this objective, four multi-criteria variables were defined: gender equality, age range, areas of knowledge and expertise, and macro-region representation (Figure 4), maintaining the balance in number within the first two criteria:

- Phase 2: Data collection. The in-depth interview was the instrument of choice for the research. The interview consisted of twelve open-ended questions, structured into three blocks of questions: introductory, central, and concluding.

- Phase 3: Data Analysis: The analysis of the data was carried out through thematic analysis. This type of analysis was the most appropriate for achieving our research objectives since it allowed the research team to identify, classify, and define thematic patterns in order to produce the final report. A thematic analysis leads to a better understanding and interpretation of the data. The analysis was carried out in six phases: data knowing; data coding; themes searching; reviewing; defining and naming; and report producing [60]. Although at the beginning, a qualitative analysis computer tool was used, most of the process was finally done manually given the complexity of the results obtained and the need to familiarize oneself with them in order to analyze them in-depth. This process led to the identification of the relevant variables in each of the dimensions.

- Phase 4: Results. Results were classified into three blocks in accordance with the themes: (1) a reflection on the three main concepts and definitions that will form part of the first block of questions; (2) identification of the main challenges toward 2030; and (3) potential solutions that 4S SMEs may provide to the Sustainable Development Goals, finalizing with success stories carried out in different territories.

4. Results

4.1. Results on Concepts and Definitions: GDP, Prosperity, and Wellbeing. Validity, Relevance, and Perception from SMEs

4.2. Results on Current Situation and Issues to Be Addressed for SMEs to Move toward UN2030A

4.3. Results on Potential Solutions Given by 4S SMEs to Advance in the Implementation of the SDGs

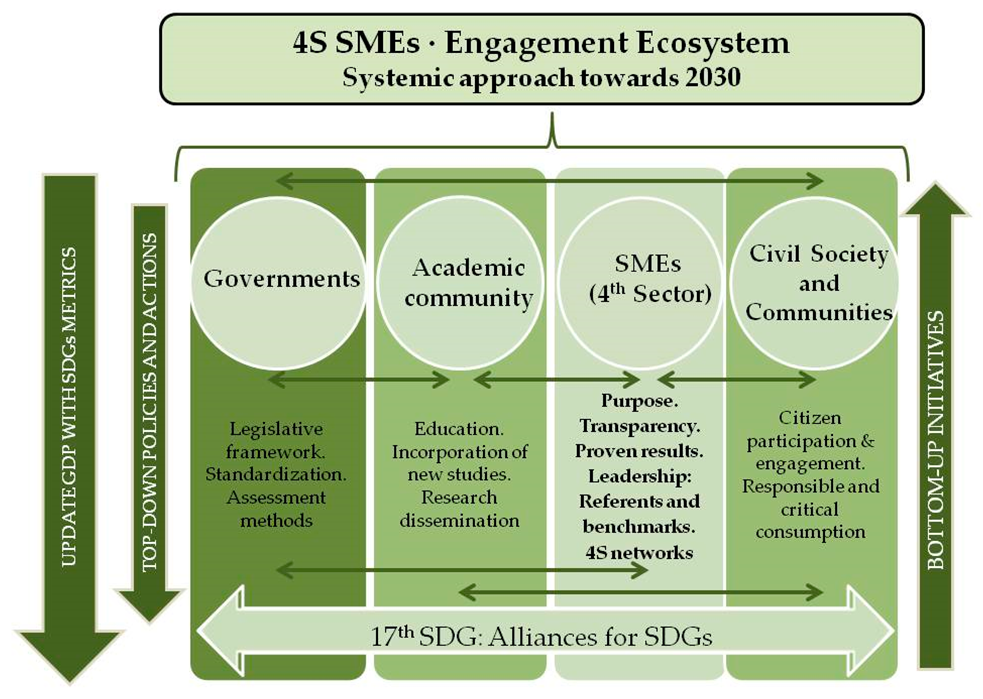

5. Discussion

6. Conclusions

7. Limitations and Future Lines of Research

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Fourth Sector Network. The Emerging Fourth Sector About Fourth Sector Network; Fourth Sector Network: Washington, DC, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Sabeti, H. The For-Benefit Enterprise. Harv. Bus. Rev. 2011, 89, 98–104. [Google Scholar]

- United Nations Development Programme. The Fourth Sector: Can Business Unusual Deliver on the SDGs? UNDP. Available online: https://www.undp.org/content/undp/en/home/blog/2018/the-fourth-sector--can-business-unusual-deliver-on-the-sdgs.html (accessed on 24 May 2019).

- Jímenez Escobar, J.; Morales Gutiérrez, A.C. Social economy and the fourth sector, base and protagonist of social innovation. CIRIEC-España Rev. Econ. Pública Soc. Coop. 2011, 73, 33–60. [Google Scholar]

- What Are For-Benefit Organizations? Available online: https://www.fourthsector.org/for-benefit-enterprise (accessed on 30 September 2019).

- Max-Neef, M. The good is the bad that we don’t do. Economic crimes against humanity: A proposal. Ecol. Econ. 2014, 104, 152–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- OECD; Council, O.; Level, M. OECD Enhancing the contributions of SMEs in a global and digitalised economy. In Proceedings of the Meeting of the OECD Councilat Ministerial Level, Paris, France, 7–8 June 2017; pp. 7–8. [Google Scholar]

- Pomare, C. A multiple framework approach to sustainable development goals (SDGs) and entrepreneurship. Contemp. Issues Entrep. Res. 2018, 8, 11–31. [Google Scholar]

- Coscieme, L.; Sutton, P.; Mortensen, L.F.; Kubiszewski, I.; Costanza, R.; Trebeck, K.; Pulselli, F.M.; Giannetti, B.F.; Fioramonti, L. Overcoming the Myths of Mainstream Economics to Enable a New Wellbeing Economy. Sustainability 2019, 11, 4374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meadows, D.H.; Meadows, D.L.; Randers, J.; Behrens, W.W., III. The limits to growth. A report for The Club of Rome’s Projecton the predicament of Mankind; Universe Books: New York, NY, USA, 1972; ISBN 0-87663-165-0. [Google Scholar]

- Büchs, M.; Koch, M. Challenges for the degrowth transition: The debate about wellbeing. Futures 2019, 105, 155–165. [Google Scholar]

- Tukker, A. Prosperity Without Growth: The Transition to a Sustainable Economy by Tim Jackson. J. Ind. Ecol. 2010, 14, 178–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Costanza, R.; Caiglia, E.; Fioramonti, L.; Kubiszewski, I.; Lewis, H.; Lovins, H.; McGlade, J.; Mortensen Lars, F.; Philipsen, D.; Pickett, K.; et al. Toward a Sustainable Wellbeing Economy Club of Rome. Solutions 2018, 9, 2. [Google Scholar]

- Stockhammer, E.; Hochreiter, H.; Obermayr, B.; Steiner, K. The Index of Sustainable Economic Welfare (ISEW) as an alternative to GDP in measuring economic welfare. The results of the Austrian ISEW calculation. Ecol. Econ. 1996, 21, 19–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lawn, P.A. A theoretical foundation to support the Index of Sustainable Economic Welfare (ISEW), Genuine Progress Indicator (GPI), and other related indexes. Ecol. Econ. 2003, 44, 105–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Max-Neef, M. The world on a collision course and the need for a new economy. Ambio 2010, 39, 200–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Costanza, R.; Daly, L.; Fioramonti, L.; Giovannini, E.; Kubiszewski, I.; Mortensen, L.F.; Pickett, K.E.; Ragnarsdottir, K.V.; De Vogli, R.; Wilkinson, R. Modelling and measuring sustainable wellbeing in connection with the UN Sustainable Development Goals. Ecol. Econ. 2016, 130, 350–355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lawn, P.; Clarke, M. The end of economic growth? A contracting threshold hypothesis. Ecol. Econ. 2010, 69, 2213–2223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Howarth, R.B.; Kennedy, K. Economic growth, inequality, and well-being. Ecol. Econ. 2016, 121, 231–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kubiszewski, I.; Costanza, R.; Franco, C.; Lawn, P.; Talberth, J.; Jackson, T.; Aylmer, C. Beyond GDP: Measuring and achieving global genuine progress. Ecol. Econ. 2013, 93, 57–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berik, G.; International Labour Organization. Toward More Inclusive Measures of Economic Well-Being: Debates and Practices; International Labour Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Porter, M.E.; Stern, S. SOCIAL PROGRESS INDEX 2014—Executive Summary. Available online: socialprogressimperative.org (accessed on 12 August 2019).

- Fehder, B.Y.D.; Stern, S. The Social Progress Imperative. Soc. Prog. Index 2013 2013, 2, 11–38. [Google Scholar]

- 2019 Social Progress Index. Available online: https://www.socialprogress.org/ (accessed on 30 September 2019).

- New Economics Foundation Happy Planet Index. Available online: http://happyplanetindex.org/ (accessed on 24 June 2019).

- New Economics Foundation The Happy Planet Index|New Economics Foundation. Available online: https://neweconomics.org/2006/07/happy-planet-index (accessed on 24 July 2019).

- New Zealand Government. The Treasury Measuring Wellbeing: The LSF Dashboard. Available online: https://treasury.govt.nz/information-and-services/nz-economy/living-standards/our-living-standards-framework/measuring-wellbeing-lsf-dashboard (accessed on 10 August 2019).

- Graham-McLay, C. New Zealand’s Next Liberal Milestone: A Budget Guided by ‘Well-Being’—The New York Times. Available online: https://www.nytimes.com/2019/05/22/world/asia/new-zealand-wellbeing-budget.html (accessed on 2 August 2019).

- European Commission Beyond GDP: Measuring Progress, True Wealth, and Well-Being. Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/environment/beyond_gdp/index_en.html (accessed on 1 August 2019).

- Smithsonian.com What Is the Anthropocene and Are We in It?|Science|Smithsonian. Available online: https://www.smithsonianmag.com/science-nature/what-is-the-anthropocene-and-are-we-in-it-164801414/ (accessed on 23 August 2019).

- Summary for Policymakers. Available online: https://www.ipcc.ch/site/assets/uploads/sites/2/2019/05/SR15_SPM_version_report_LR.pdf (accessed on 8 September 2019).

- Wealth Inequality Keeps Widening. But It’s Nothing New|World Economic Forum. Available online: https://www.weforum.org/agenda/2017/12/wealth-inequality-has-been-widening-for-millennia/ (accessed on 10 June 2019).

- Giannetti, B.F.; Agostinho, F.; Almeida, C.M.V.B.; Huisingh, D. A review of limitations of GDP and alternative indices to monitor human wellbeing and to manage eco-system functionality. J. Clean. Prod. 2015, 87, 11–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wellbeing Economy Governments WEGo—Background. Available online: http://wellbeingeconomygovs.org/background/ (accessed on 10 August 2019).

- Wellbeing Economy Governments WEGo—Wellbeing Economy Governments. Available online: http://wellbeingeconomygovs.org/ (accessed on 10 August 2019).

- SustainAbility Trends 2019. Available online: https://trends.sustainability.com/citizen-power/ (accessed on 19 July 2019).

- Trebeck, K. WEAll Citizens|A New Economy for All—Katherine Trebeck Writes for UN Association. Available online: https://wellbeing-economy-alliance-trust.hivebrite.com/news/202657 (accessed on 26 July 2019).

- CUSP Centre for the Understanding of Sustainable Prosperity. Available online: https://www.cusp.ac.uk/ (accessed on 26 August 2019).

- Rethinking Economics. Available online: http://www.rethinkeconomics.org/ (accessed on 26 July 2019).

- New Economics Foundation Together We Can Change the Rules to Make the Eeconomy Work for Everyone|New Economics Foundation. Available online: https://neweconomics.org/ (accessed on 26 June 2019).

- IISD|International Institute for Sustainable Development. Available online: https://www.iisd.org/ (accessed on 10 June 2019).

- Capital Institute-Co-creating the Regenerative Economy. Understand. Inspire. Available online: https://capitalinstitute.org/ (accessed on 6 June 2019).

- Smart Economics for the Environment and Human Development (SEED). Available online: http://www.smart-development.org/about (accessed on 8 August 2019).

- Prosperity in Africa. Available online: https://www.ascleiden.nl/content/webdossiers/prosperity-africa (accessed on 16 August 2019).

- Stockholm Resilience Centre—Stockholm University. Available online: https://www.stockholmresilience.org/research/our-research-focus.html (accessed on 26 July 2019).

- UCI University for International Cooperation, UCI. Available online: https://www.uci.ac.cr/certificate-regenerative-entrepreneurship/ (accessed on 15 August 2019).

- Center for Applied Cultural Evolution Center for Applied Cultural Evolution. Available online: https://culturalevolutioncenter.org/ (accessed on 1 August 2019).

- Post Crash Economy—Pompeu Fabra University. Available online: https://postcrashbarcelona.wordpress.com/ (accessed on 26 August 2019).

- Rethinking Economics—Post-Crash UPF. Available online: http://www.rethinkeconomics.org/re-group/post-crash-upf/ (accessed on 15 July 2019).

- UCL Institute for Global Prosperity-UCL-London’s Global University. Available online: https://www.ucl.ac.uk/bartlett/igp/ (accessed on 18 June 2019).

- New Economy Network Australia. Available online: https://www.neweconomy.org.au/ (accessed on 28 July 2019).

- NESI Forum—New Economy and Social Innovation. Available online: https://nesi.es/ (accessed on 20 August 2019).

- WEAll Wellbeing Economy Alliance—Building a Movement for Economic System Change. Available online: https://wellbeingeconomy.org/page/10 (accessed on 1 October 2019).

- UN General Assembly. Transforming Our World: The 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development; UN General Assembly: New York, NY, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Reynolds, J. Rewiring the Economy: Ten Tasks, Ten Years; Cambridge Institute for Sustainability Leadership: Cambridge, UK, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- University of Cambridge Cambridge Institute for Sustainability Leadership. Available online: https://www.cisl.cam.ac.uk/ (accessed on 1 August 2019).

- Secretaría General Iberoamericana (SEGIB). Business with Purpose and the Rise of the Fourth Sector in Ibero-America; Secretaría General Iberoamericana (SEGIB): Madrid, Spain, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- SEGIB|Secretaría General Iberoamericana. Available online: https://www.segib.org/en/ (accessed on 26 May 2019).

- The Fourth Sector in Ibero-America—Fostering Social & Sustainable Economy. Available online: https://www.elcuartosector.net/en/ (accessed on 26 June 2019).

- Braun, V.; Clarke, V.; Hayfield, N.; Terry, G. Thematic Analysis. J. Transform. Educ. 2018, 16, 175. [Google Scholar]

- Kubiszewski, I.; Costanza, R.; Gorko, N.E.; Weisdorf, M.A.; Carnes, A.W.; Collins, C.E.; Franco, C.; Gehres, L.R.; Knobloch, J.M.; Matson, G.E.; et al. Estimates of the Genuine Progress Indicator (GPI) for Oregon from 1960–2010 and recommendations for a comprehensive shareholder’s report. Ecol. Econ. 2015, 119, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fox, M.J.V.; Erickson, J.D. Genuine Economic Progress in the United States: A Fifty State Study and Comparative Assessment. Ecol. Econ. 2018, 147, 29–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fuller, M.; Dwivedi, P. Assessing Changes in Inequality for Millennium Development Goals among Countries: Lessons for the Sustainable Development Goals. Soc. Sci. 2019, 8, 207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goal 3: Sustainable Development Knowledge Platform. Available online: https://sustainabledevelopment.un.org/sdg3 (accessed on 23 August 2019).

- Max-Neef, M. Economic growth and quality of life: A threshold hypothesis. Ecol. Econ. 1995, 15, 115–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cruz, I.; Stahel, A.; Max-Neef, M. Towards a systemic development approach: Building on the Human-Scale Development paradigm. Ecol. Econ. 2009, 68, 2021–2030. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Max-Neef, M.; Elizalde, A.; Hopenhayn, M.; Herrera, F.; Zemelman, H.; Jatoba, J.; Weinstein, L. Desarrollo a Escala Humana una opcion para el futuro (versión de Cepaur Fundación Dag Hammarskjold). Dev. Dialogue Numer. Espec. 1986, 62. [Google Scholar]

- Elkington, J. Enter the Triple Bottom Line (Chapter 1). In The Triple Bottom LIne. Does it All Add up? Assessing the Sustainability of Business and CSR; Henriques, A., Richardson, J., Eds.; Taylor & Francis: New York, NY, USA, 2004; pp. 24–51. ISBN 9781844070152. [Google Scholar]

- Raworth, K.; Doughnut. Kate Raworth. Available online: https://www.kateraworth.com/doughnut/ (accessed on 14 August 2019).

- Ostrom, E. Institutions and the environment. Econ. Affairs 2008, 28, 24–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McKean, M.; Ostrom, E. Common property regimes in the forest: Just a relic from the past? Unasylva 1995, 180, 3–15. [Google Scholar]

- FridaysForFuture. Available online: https://www.fridaysforfuture.org/ (accessed on 10 August 2019).

- UNESCO. Declaration on the Responsibilities of the Present Generations Towards Future Generations. In Proceedings of the Records of the 29th Session of the General Conference, Paris, France, 18–28 August 1997; United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization: Paris, France, 1998; Volume 1, pp. 69–71. [Google Scholar]

- WEAll Scotland—Wellbeing Economy Alliance. Available online: https://wellbeingeconomy.org/scotland (accessed on 21 August 2019).

- Farley, J.; Costanza, R. Payments for ecosystem services: From local to global. Ecol. Econ. 2010, 69, 2060–2068. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Certificación Para la Sostenibilidad Turística—CST Costa Rica. Available online: https://www.turismo-sostenible.co.cr/ (accessed on 9 August 2019).

- Frey, M.; Sabbatino, A. The Role of the Private Sector in Global Sustainable Development: The UN 2030 Agenda. In Corporate Responsibility and Digital Communities; Springer: Berlin, Germany, 2018; pp. 187–204. [Google Scholar]

- The Guardian the Troubling Evolution of Corporate Greenwashing. Guardian Sustainable Business. Available online: https://www.theguardian.com/sustainable-business/2016/aug/20/greenwashing-environmentalism-lies-companies (accessed on 19 August 2019).

- Stiglitz, J.E.; Sen, A. The Measurement of Economic Performance and Social Progress Revisited Reflections and Overview. Doc. Trav. OFCE 2009, 33, 79. [Google Scholar]

- Has GDP Become an Impediment to a Better Society? Financial Times. Available online: https://www.ft.com/content/a9c7b6d8-08cc-11e7-ac5a-903b21361b43 (accessed on 4 August 2019).

- Helliwell, J.F.; Layard, R.; Sachs, J.D. World Happiness Report; The United Nations Sustainable Development Solutions Network: New York, NY, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- WEAll Ideas: Little Summaries of Big Issues ‘7 Ideas for the G7’. Available online: https://wellbeingeconomy.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/08/Seven-Ideas-for-the-G7-2019.pdf (accessed on 4 September 2019).

- Open Democracy; Janoo, A. Our Economy: Seven Ideas for the G7. Available online: https://www.opendemocracy.net/en/oureconomy/seven-ideas-g7/ (accessed on 23 August 2019).

- Morioka, S.N.; Bolis, I.; de Carvalho, M.M. From an ideal dream towards reality analysis: Proposing Sustainable Value Exchange Matrix (SVEM) from systematic literature review on sustainable business models and face validation. J. Clean. Prod. 2018, 178, 76–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morioka, S.N.; Bolis, I.; Evans, S.; Carvalho, M.M. Transforming sustainability challenges into competitive advantage: Multiple case studies kaleidoscope converging into sustainable business models. J. Clean. Prod. 2018, 167, 723–738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- The Fourth Sector. Available online: https://www.fourthsector.org/supportive-ecosystem (accessed on 23 August 2019).

- Neumeyer, X.; Santos, S.C. Sustainable business models, venture typologies, and entrepreneurial ecosystems: A social network perspective. J. Clean. Prod. 2018, 172, 4565–4579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- WEAll Wellbeing Economy Alliance—Hub Guide. Available online: https://wellbeingeconomy.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/05/WEAll-Hub-Guide.pdf (accessed on 23 August 2019).

| # | Gender | Age Range | Areas of Knowledge and Expertise | Macro-Region |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | M | <50 | Politic sciences, Sociology, and 4S entrepreneur | Europe |

| 2 | F | >50 | Social innovation expert, consultant, and 4S entrepreneur | Europe |

| 3 | F | <50 | Mathematics & Exact Sciences, and 4S entrepreneur | Europe |

| 4 | F | <50 | Social Anthropology, business leader, and 4S entrepreneur | Europe |

| 5 | M | <50 | Sustainable tourism expert, University Professor, and researcher | LatAm |

| 6 | F | <50 | New Economics network expert, and business leader | Europe |

| 7 | M | >50 | Tourism expert, 4S SMEs investor, and business leader | Europe |

| 8 | M | >50 | Chemical engineering, Univ. Prof., and researcher | LatAm |

| 9 | M | <50 | Community-based tourism expert, Univ. Prof., 4S entrepreneur | LatAm |

| 10 | M | >50 | Sustainable Tourism expert, consultant, and 4S entrepreneur | Europe |

| 11 | F | >50 | Degree in Law, and business leader | Europe |

| 12 | F | >50 | Psychology, and 4S entrepreneur | LatAm |

| Theme 1: Reflections on Concepts and Definitions: Validity, Relevance, and Perception from SMEs | Theme 2: Reflections on the Current Situation, and Issues to Be Addressed for SMEs to Move towards UN2030A | Theme 3: Reflections on Potential Solutions Given by 4S SMEs to Advance in the Implementation of the SDGs |

|---|---|---|

| GDP: Do you think GDP is the valid macroeconomic magnitude to advance towards 2030 challenges? | Public policies: Which are the main barriers and restrictions SMEs are facing to move forward to 2030? | From an SME perspective, do you consider SDGs as the solid theoretical framework for a wellbeing-centered economy? |

| Which should be the main pillars of the new economic model valid for 2030? | ||

| Prosperity: Reflections on the concept. In your opinion, is it equivalent to the “standard of living” concept? | Difficulties SMEs are facing: Which are the negative impacts on SMEs, and which the main issues the need to overcome to move towards 2030? Main topics and trends in your country or region | Which solutions may bring a new economy, sustainable and wellbeing-centered in your country or region? |

| Reflections on the role of the Fourth Sector SMEs towards 2030 | ||

| Well-being: Reflections on the concept. In your opinion, is it equivalent to “quality of life”? | How to raise awareness in society to involve most people in the SDGs challenges? | |

| Success stories that may be extrapolated to other territories |

| Themes | Questions | Summary |

|---|---|---|

| Theme 1: Concepts and definitions | GDP |

|

| Prosperity |

| |

| Well-being |

| |

| Theme 2: Difficulties and main issues | Public policies: Barriers and restrictions |

|

| Difficulties, negative impacts, and main issues SMEs are facing |

| |

| Theme 3: Potential solutions | SDGs as a framework for a wellbeing-centered economy |

|

| Main pillars of the new sustainable, economic model |

| |

| Solutions from a new sustainable, well-being economy |

| |

| Role of sustainable, 4S SMEs |

| |

| Raise awareness in society |

| |

| Success stories |

|

© 2019 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Rubio-Mozos, E.; García-Muiña, F.E.; Fuentes-Moraleda, L. Rethinking 21st-Century Businesses: An Approach to Fourth Sector SMEs in Their Transition to a Sustainable Model Committed to SDGs. Sustainability 2019, 11, 5569. https://doi.org/10.3390/su11205569

Rubio-Mozos E, García-Muiña FE, Fuentes-Moraleda L. Rethinking 21st-Century Businesses: An Approach to Fourth Sector SMEs in Their Transition to a Sustainable Model Committed to SDGs. Sustainability. 2019; 11(20):5569. https://doi.org/10.3390/su11205569

Chicago/Turabian StyleRubio-Mozos, Ernestina, Fernando Enrique García-Muiña, and Laura Fuentes-Moraleda. 2019. "Rethinking 21st-Century Businesses: An Approach to Fourth Sector SMEs in Their Transition to a Sustainable Model Committed to SDGs" Sustainability 11, no. 20: 5569. https://doi.org/10.3390/su11205569

APA StyleRubio-Mozos, E., García-Muiña, F. E., & Fuentes-Moraleda, L. (2019). Rethinking 21st-Century Businesses: An Approach to Fourth Sector SMEs in Their Transition to a Sustainable Model Committed to SDGs. Sustainability, 11(20), 5569. https://doi.org/10.3390/su11205569