1. Introduction

Our society’s environmental footprint is highly influenced by its citizens’ personal decisions. What we eat, how we live and what we buy all have a major impact on the extent to which resources are used, as well as the resulting pollution or climate change. Life Cycle Assessment (LCA) studies have revealed how lifestyles and individual consumption, mobility and housing decisions influence the environmental impact of our society [

1,

2,

3]. While updating and changing our political and economic system is needed to achieve the goals of the Agenda 2030 for Sustainable Development, individuals can also play an important role by adopting sustainable lifestyles and making sustainable choices. Sustainable Development Goal 12, “Sustainable consumption and production,” explicitly highlights the role of consumption and its impact on the over-extraction and degradation of environmental resources [

4]. Supporting and enabling sustainable lifestyles through education, information and awareness raising are among the key strategies for achieving sustainable consumption [

4].

In this context, Life Cycle Thinking (LCT) is an important concept that considers the environmental impact of the whole life cycle of a product or service. It therefore goes beyond a limited consideration of the direct environmental impact of production, but rather also includes the impact of consumption and disposal [

5]. LCT offers both tools for assessing and for communicating the environmental impact of consuming goods or services.

One well-known example is the WWF footprint calculator, based on LCA-Data, which gives consumers instant and individual feedback on their overall carbon footprint [

6]. Another example is the LCA-based Product Environmental Footprint (PEF), which is supported by the European Commission as an instrument for ‘Credible communication to consumers avoiding confusion and mistrust’ [

7].

Questions arise, however, as to how environmental impacts can be communicated, so that they are: (a) Easily understandable, and (b) will effectively influence consumer behavior [

5,

7]. Several barriers have been identified. Firstly, although communicating environmental impacts with LCT affords obvious advantages to consumers (e.g., inclusion of the full life cycle, comparability, transparency), it is also believed to create some challenges, such as by causing information overload or having a high degree of complexity. LCA researchers and practitioners often face the challenge that consumers do not easily understand the results from LCA modeling, and therefore fail in many cases to make well-informed decisions. Secondly, different gaps have been identified that hinder pro-environmental behavior, such as lacking environmental consciousness or intrinsic incentives, or old behavior patterns [

8], which can explain the knowledge-to-action gap [

9]. Csutora [

10] also described the behavior-impact gap (BIG) as a gap between pro-environmental behavior and the actual ecological footprint of the consumer. A study in Germany, for example, revealed that households with a high environmental awareness tend to have a higher energy consumption [

11]. Among explanations for this are rebound effects [

12], moral licensing [

13] and escape strategies [

10] from “green” consumers, who offset the environmental load with green purchases or habits. A common example is wealthy individuals buying organic food, but regularly flying when they take holidays.

Environmental education and sustainability communication have to address these barriers and gaps through effective measures. Arousing learners’ emotions, challenging their beliefs and enhancing their environmental concepts, have been identified as the main factors by which learning experiences can contribute towards the adoption of environmentally-sustainable behavior [

14]. As concluded by Goel and Sivam [

1], individuals can be motivated to make sustainable decisions by providing them with information, especially if it is communicated in a positive way.

New formats in sustainability communication and education are emerging which are less formal, much more entertaining, and targeted at a broader audience. Some of these new communication formats, such as serious games and edutainment, have already been shown to promote awareness about sustainability challenges among citizens, and to increase motivation and engagement [

15,

16,

17]. By using these entertaining formats, even people that are not primarily concerned or interested in sustainability can be reached [

18].

Presented in this paper, the Eco-Confessional is an interactive exhibit and serious game, which has been developed as an attempt to educate a wide audience on the environmental impact of their daily life decisions and to motivate them to adopt a more sustainable lifestyle. The project combines the approaches of scientainment, sustainability education and gamification to inform people about the environmental impact of their decisions. The goal of this paper is to explore the effectiveness of the Eco-Confessional as an approach to promoting sustainable behavior through LCT.

2. Materials and Methods

This section includes the relevance of the Eco-Confessional and its rationalization (2.1), the life cycle assessment to provide the database for the Eco-Confessional (2.2) and the evaluation survey for the overall project (2.3). The same structure is also used in

Section 3.

2.1. Relevance & Rationalization

The conceptual idea of the Eco-Confessional is to initiate behavioral change through an interactive experience that promotes curiosity, surprise and amusement. These emotions are used to increase both the ability and the desire to make sustainable decisions (

Figure 1).

The development of the Eco-Confessional was based on the well-known concept of confessions and indulgences in the Roman Catholic Church, which was modified to invite the confessions of the ecological “sins” of daily life in a playful manner. On the one hand, this helped visitors to easily grasp the concept (e.g., confessing, atonements for sins). On the other hand, the name “Eco-Confessional” was used to attract more attention and arouse curiosity. It was intended to specifically address non- environmentally-affected young people from the so-called “Generation Z”, the generation born after 1995, who are familiar with digital media and gamification elements [

19].

The key purpose of the Eco-Confessional was to inform visitors about the extent to which their daily choices impact the environment, as well as the kind of impact (e.g., water, soil, climate) and how these choices compare to each other in terms of their impact. This considered both eco-sins and good deeds, which compensated for the sins. Since the extent of the sin’s impact on the environment was directly compared with the ‘good deed,’ the magnitude of the participants’ everyday habits was made comprehensible. The concept was based on Life Cycle Thinking (LCT), so that the choices covered the full life cycle, and to make choices comparable.

2.2. Assessing the Environmental Impact of Eco-Sins and ‘Good Deeds’

The Eco-Confessional is based on a life cycle inventory (LCI) model, which quantifies both the consumption of resources and the generation of emissions resulting from 56 different eco-sins (e.g., eating meat, shopping for clothes, using the car or drinking coffee), and the potential reduction in emissions and in the consumption of resources due to 30 different ‘good deeds,’ while taking the full life cycle into consideration. The selection of eco-sins and good deeds used in the eco-confessional is mainly based on their environmental relevance. An additional criteria for selection was the relevance of such choices in a person’s daily life, however the actual needs of individuals in their different life-stages and conditions have not been considered.

By conducting a life cycle impact assessment for this LCI model, the environmental impact of the eco-sins and the potential environmental benefits of the ‘good deeds’ were calculated. This data provided the basis for developing the interactive program that links the eco-sins with ‘good deeds.’

Depending on the eco-“sin” that the user would like to confess and the ‘good deeds’ that he or she would like to carry out, the software calculates how often a particular action would need to be implemented in order to compensate for an equivalent environmental impact. In order to ease the selection of eco-sins during the game, habits were grouped into categories corresponding to the seven deadly sins (pride, greed, lust, envy, gluttony, wrath and sloth).

The life cycle assessment covers the consumption of resources and the emission of pollutants across all relevant life cycle stages of the involved products and services, from cradle to grave, as described by the ISO 14,040 standards [

20]. The total environmental impacts were quantified according to the Ecological Scarcity Impact Assessment Method, which covers 19 different environmental problems from water depletion to climate change [

21]. For the life cycle inventory model, foreground data specific to the described eco-sins and ‘good deeds’ was combined with background data from the ecoinvent database v3.1 with the system model ‘allocation cut-off by classification’ [

22]. The individual models for the specific eco-sins and ‘good deeds’ were described by Eymann et al. [

23]. All calculations were carried out with the SimaPro v8 software [

24].

2.3. Evaluating the Impact of the Eco-Confessional on the Audience

The development of the Eco-Confessional was accompanied by an evaluation. The first version was tested for the user experience, and was followed by guided interviews with members of the target group. The interviews focused on the suitability of the ‘sins’ and ‘good deeds’ for the target group, comprehension of the content and process, and the ‘fun-factor’. The improved version was again tested with members of the target group. These first pretests led to a simplification of the wording and the addition of more ‘gamification’ elements in the process of the confession.

In the final evaluation, various methods were combined to measure the impact of the new communication format. The main elements were a standardized survey for visitors, and data collected automatically in the Eco-Confessional during each visit. The survey asked for a personal assessment of the Eco-Confessional and behavioral intentions using ten multiple choice questions. In addition, the participants’ environmental awareness was determined using three statements on their environmental behavior and two statements on their environmental awareness that could be rated on a four-point Likert scale, with anchors of “agree” and “disagree”. The statements were chosen specifically considering the environmental behavior of young people. Over six days, a written survey was conducted at five different locations resulting in 87 completed surveys. Additionally, the same survey was provided online using ‘Online Umfragen’ (

https://www.onlineumfragen.com/), resulting in an additional 63 completed surveys. This resulted in a total of 150 completed surveys.

3. Results

3.1. Eco-Confessional

The project was realized by an interdisciplinary team, which involved a designer, illustrator, computer and LCA scientists, and communication specialists. The Eco-Confessional itself was designed as a walk-in instalment which was equipped with an interactive screen. The interaction on the screen, which was supported by audio guidance, was the main feature of the Eco-Confessional (an identical version is available at

http://www.oekobeichtstuhl.ch). The Eco-confession begins with the selection of an eco-sin (

Figure 2a). These can be selected from a range of predefined and illustrated actions or choices ranging from mobility, housing and eating to consumption (see

Appendix A for a full list). The sins are humorously categorized according to the seven deadly sins (see

Figure 3 for examples). On the next screen, the visitor receives a simple explanation of the environmental impact of his or her choice (b). After ‘confessing’ a sin, the Eco-Confessional suggests various good deeds as compensation (c). This again can be selected from a list of illustrated choices (see

Appendix B for a full list of good deeds). The actual calculation of the environmental impact is presented on the following screen (d).

Here the user learns the results of the life cycle assessment and finds out how often the good deed must be implemented in order to compensate for an equivalent environmental impact. The final result is presented on the last screen, representing the number of times the user will need to perform the good deed (e).

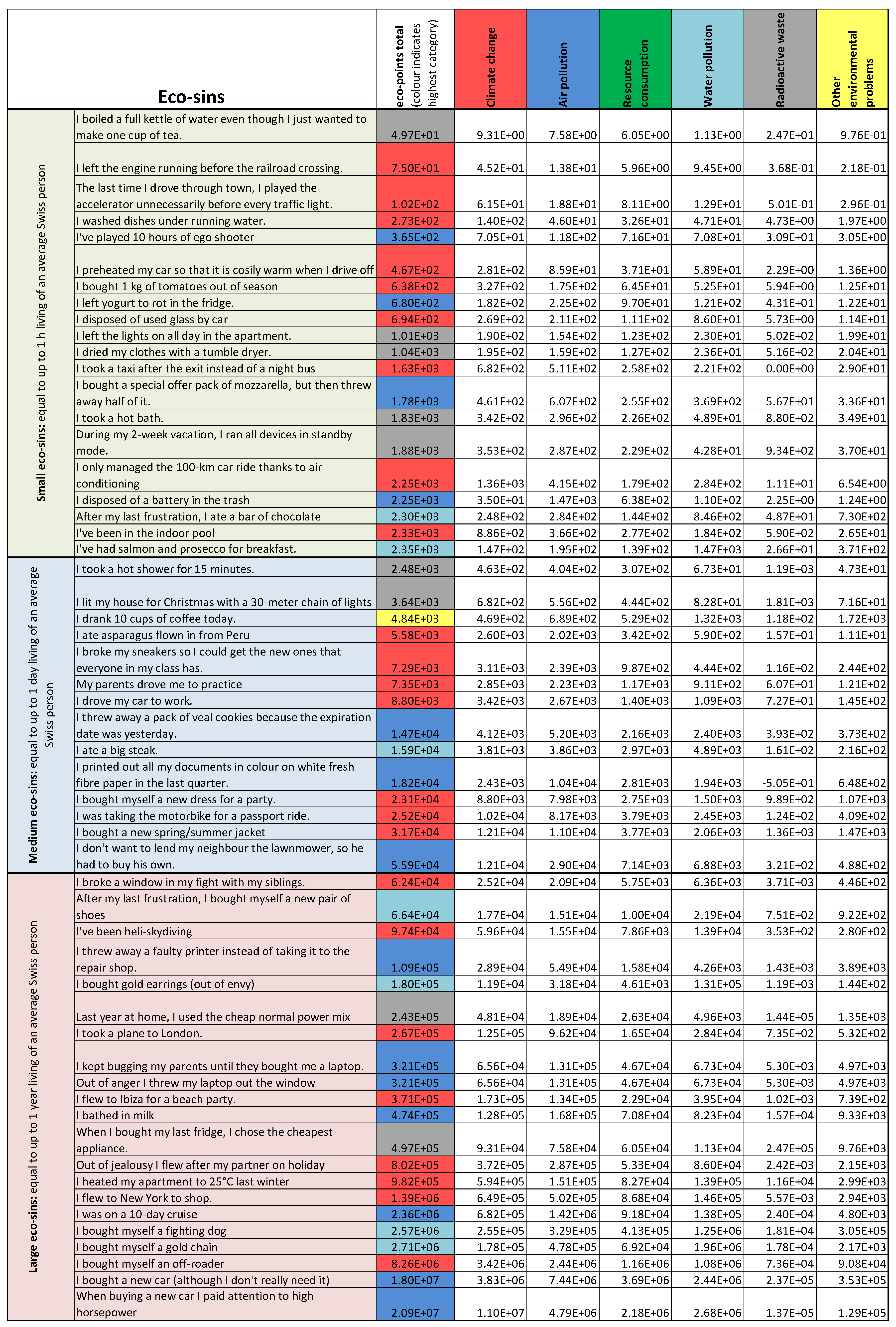

Figure 3 presents a selection of environmental impacts resulting from eco-sins (calculated in eco-points), and how they can be compensated through good deeds.

During this process, visitors could learn about the varied environmental impacts of different behaviors. The overall experience was designed to create a playful and entertaining experience for the user. The brightly colored, playful design and wording, and the animated voice of the Eco-Confessional were all specifically targeted at a younger audience.

The list of sins and good deeds also included unusual or funny examples (“Young, pretty and sexy—that’s how I want to be! That’s why I took a milk bath”) or gave unlikely explanations that played on human weaknesses, drawing on the seven deadly sins for material (“I was so jealous of my friend’s earrings that I bought the really expensive gold earrings.”). In addition to the main target group, the Eco-Confessional can also be used by people of other age groups who are interested in the playful approach to sustainability issues. To account for the different possibilities of various age groups, tasks were formulated to fit specific age groups (e.g., ‘I drove to sports class by car.’ vs. ‘I was driven to sports class by car.’).

Over six months, the tested version of the Eco-Confessional was made available free of charge to public and private organizations in Switzerland for various events. The project was accompanied by a PR campaign targeting exhibitions, potential visitors and the media.

3.2. Life Cycle Data

The environmental impacts of the selected eco-sins were subdivided into three categories according to their impact (small, medium, large) and assessed using the Ecological Scarcity Method for the six environmental issues presented in

Figure 4. All of the eco-sins contribute to climate change in one or another way, especially those which involve fuel consumption for heating or transportation. Eco-sins that lead to an increase in the consumption of grid electricity contribute to the generation of radioactive waste from nuclear power. Others that involve the purchase of metals (e.g., gold) or agricultural goods contribute to water pollutant emissions due to the supply chain.

The worst eco-sins in terms of their environmental impact are mainly luxury goods and activities, such as flying, buying new cars or jewelry, or going on a holiday cruise. These large eco-sins can equal the average environmental impact of a Swiss person in one year (K–O,

Figure 4).

Similar to the environmental impacts of the eco-sins in

Figure 4, the environmental benefits of the ‘good deeds’ assessed using the Ecological Scarcity Method are presented in

Figure 5. (I) Convincing others not to use aviation and (J) car sharing are the ‘goods deeds’ with the highest potential to compensate for an individual’s impact on the environment. With these ‘good deeds,’ large amounts of airborne emissions from fuel combustion and manufacturing can be avoided. On the other hand, abstaining from using televisions, elevators, public transport and plastic bags have only very little potential.

The results from the life cycle inventory model for the different eco-sins and ‘good deeds’ assessed using the Ecological Scarcity Method show massive differences in the environmental impacts. The eco-sin with the highest environmental impact ‘when buying a new car I paid attention to high horsepower (instead of energy efficiency)’ causes more than 40,000 times more of an environmental impact than the eco-sin with the lowest environmental impact (‘I boiled a whole kettle of water even though I just wanted to make myself a cup of tea’).

Due to the large differences in their environmental impact, some combinations of sins and good deeds deliver unachievable results. To compensate for a flight to New York, one would have to not use a plastic bag for grocery shopping 27,900 times or use the stairs instead of the elevator 89,000 times.

3.3. Results of Evaluation

The Eco-Confessional was exhibited at 16 different venues in the German speaking part of Switzerland during 2016, and this new format for communicating about sustainability was met with great interest among the organizers. Especially schools and various festivals in the environmental sector were very open to this approach. The locations were chosen in order to reach a variety of audiences—schools, museums, eco festivals, local markets, a zoo, etc.

Depending on the venue, the Eco-Confessional was present anywhere from one to 57 days and for a total of 264 days in 2016. During this time, 7214 people visited the Eco-Confessional, of which 2548 continued through to the informative contents. The other 65% terminated the program prematurely. 36.2% of the visitors finishing the game were 12–24 years of age, 29.5% were older than 24 years of age and 34.2% did not provide any information.

An important goal was to reach audiences which were not previously interested in science or environmental issues. To evaluate the success in reaching this audience, the environmental awareness of the visitors was also assessed. Even though all of these answers were self-declared, and it can therefore be assumed that the socially desirable options were chosen, most of the visitors to the Eco-Confessional appear to have been environmentally aware and concerned about their environmental impact (

Figure 6).

The principle aim of the Eco-Confessional was to present the topic of sustainability in a playful way to a non-environmentally-oriented audience. The visit to the Eco-Confessional was intended to be entertaining and fun. Visitors rated the Eco-Confessional positively, and a clear majority regarded the experience as educational, understandable, funny and exciting (

Figure 7). This positive impression was also confirmed by the fact that 75% of the visitors would recommend a visit to others.

A visit to the Eco-Confessional resulted in an increased interest in the topic. While 32% of respondents had already dealt with this topic on several occasions, 32% said they would like to focus on it even more in the future, and 30% may want to do so (

Figure 8). Besides raising awareness and interest, and providing new information, an important goal of the Eco-Confessional was to help visitors adopt a more environmentally friendly lifestyle. Of the visitors who participated in the survey, 62% planned to perform the chosen good deed, and 29% planned to do so at least partially (

Figure 8).

During confession, the visitors were able to choose from a random selection of a maximum of seven ‘eco-sins’. These were adapted to both the age of the visitor and the season. Due to this function, the different eco-sins were not displayed with the same frequency. Therefore, relative numbers (# of times sin selected/# of times sin displayed) were considered in the evaluation (see

Table 1). Similarly, after the choice of a sin, a random selection of possible good deeds was displayed. These were also adapted to the age and season. In addition, extra care was taken to provide meaningful combinations, as well as to ensure that a good deed had to be performed at least twice to compensate for a sin. This further necessitated the need to compare only relative numbers. In all age groups, realistic and common sins and good deeds were chosen, while humorous examples such as “I’ve been Heli-Skydiving” were rarely chosen (3% of the displayed cases). The choice of realistic sins and good deeds made it more likely that visitors would perform their good deeds (

Table 1).

4. Discussion

The Eco-Confessional was developed as an approach to promoting sustainable lifestyles through a playful and low-threshold access to LCT. A key aim of the Eco-Confessional was to give users a deeper understanding of the impact that their lifestyle choices have on the environment. This has been realized through a gamified tool for comparing the impacts on various common daily life decisions surrounding housing, mobility and consumption. The LCA calculations for the Eco-Confessional revealed that impacts differ in scale, with some decisions having impacts more than a factor ten thousand times higher than others do. As most people find it difficult to understand the results from LCA-Studies [

7], comparing results seems to be much easier to communicate the essential key messages. With this approach, moral licensing or rebound effects, as described by Kleinhückelkotten [

11], de Haan [

12] or Csutora [

10] can also be addressed. These studies show that people who consider themselves environmentally aware often do not act environmentally friendly in everyday life, as large living spaces and travel by airplane are more common in these groups. Through comparable data, the absurdity of such “strategies” would become obvious. For example, using the Eco-Confessional demonstrates that compensating for a flight to New York would require doing without a new plastic bag at the grocery store for the next 27,900 times. Through such comparisons, the discrepancies between consumer beliefs and the actual environmental impacts from lifestyle decisions can be revealed.

As with all single score life cycle impact assessment methods, the applied Ecological Scarcity Method includes a weighting step which can be criticized as subjective. However, in the case of the Ecological Scarcity Method, this weighting step is based upon the environmental targets of the national legislation in Switzerland, and therefore is sufficiently backed by the Swiss parliament. Furthermore, LCA experts that contributed to the 2015 SETAC Europe LCA session, “Midpoint, endpoint or single score for decision-making?” agreed that single-score assessments can contribute to sound and effective decision support if backed up by relevant and transparent information [

25]. If required, the Eco-Confessional can also be adapted for specific midpoint indicators, such as the carbon footprint, in order to address the specific environmental impacts of eco-sins and ‘good deeds’.

The LCA results are affected by various uncertainties in the life cycle inventory data and in the impact assessment, and due to qualified estimations by the authors that were required for the modeling. However, since the results for the various eco-sins and ‘good deeds’ differ substantially in scale, an approximate number is considered as a sufficient result, and detailed statistical analysis was not conducted. The quality of the data is considered as adequate for the purpose of the Eco-Confessional.

Choosing a gamified approach for the Eco-Confessional is based on various studies, demonstrating the positive effect on learning and the potential for reaching a larger audience, including those with little prior interest or awareness in environmental issues [

15,

16]. According to Ballantyne and Packer [

14], key factors for effective free-choice learning experiences are arousing emotions, challenging beliefs, and enhancing environmental conception. The strategies and success in adapting these factors into the Eco-Confessional are discussed as follows:

Arousing learners’ emotions: As described in the theoretical causal chain (see

Figure 1) the Eco-Confessional was designed to create an experience involving surprise, fun and curiosity. These emotions will help to stimulate exploratory behavior and a willingness to learn, and will also support the memorization of experiences [

14]. The overall design, the illustrations and also the title, supported these experiences. Many visitors attested that the game was funny and exciting, and that the result of the Eco-Confessional was surprising to them. The majority of the visitors planned to learn more about sustainability in future.

Challenging learners’ beliefs: The Eco-Confessional challenges the beliefs of its users in two ways. Firstly, it challenges the misconceptions of environmental impacts from various lifestyle decisions (as described above). In addition, it also challenges the users’ beliefs regarding how they can make an impact on environmental problems. This is achieved by providing information on implementable good-deeds and their potential for compensating for eco-sins.

Ballantyne and Packer [

14] highlight the importance of providing positive experiences for learners to realize that their choices do have an actual impact upon the environment. The evaluation of the Eco-Confessional showed that users had a desire to make more environmentally friendly decisions after the visit, and most visitors stated the intention to carry out the chosen good deed. This high number of visitors with positive intentions could partly be explained by the fact that many of the visitors can be considered environmentally aware (see

Figure 6), and/or are trying to meet social standards. Since people who already have an affinity for the environment often seem to have an inflated view of their own environmental behavior, but on the other hand are highly motivated to make their own everyday lives environmentally friendly, challenging these beliefs with information along with practical tips can have a strong impact. This effect might be lower, however, when targeting a broader audience.

Enhancing environmental understanding: Learning experiences are more effective if they confront learners with information that challenges existing misconceptions [

14]. As described above, this element is a key feature of the Eco-Confessional, as discrepancies between beliefs and facts about the impact of lifestyle decisions on the environment will be clearly revealed.

Increased understanding and the intention to make behavioral changes are the first steps towards forming new habits. Various behavioral change models show that planning is a crucial step to progressing from intention to action [

26]. Providing a selection of various very specific good deeds that can easily be implemented simplifies the crucial next step of planning. Also, a previously-defined situation, as stated in the good deeds, that arises in everyday life, may automatically trigger the new behavior. As visitors predominantly chose realistic, do-able good deeds, it can be assumed that opportunities for implementation are plausible. However, it is clear that a single intervention like the visit to the Eco-Confessional by itself is unlikely to result in new habits in most visitors, as many other factors need to be present as well (

e.g., the ability to perform the task, motivation, managing relapses…). Nonetheless, the goal of the project was to increase sustainable behavior by influencing both the desire and the ability to make sustainable decisions. Though the evaluation could not show the direct impact on actual behavior, it did show that the project has been successful in changing awareness and intention, as prerequisites for changes in behavior. By combining life cycle data with gamification elements, the Eco-Confessional succeeded in implementing a new scientainment approach to environmental education that promotes life cycle thinking among the public. In summary, the Eco-Confessional achieved its goals through a set of strategies and achievements:

Initiation of discussion through provocation and surprise

Informing and increasing awareness in a positive and fun way

Making scientific data on the environmental impact of daily life behavior available and understandable

Educating about the extent of the environmental impact of daily life habits

Providing competencies for responsible decisions

Reaching a broad audience (reaching both people with and without prior sustainability awareness)

A limitation of the Eco-Confessional is its dependence on the physical exhibit, which reduces the outreach potential of the project. Some preliminary ideas for reaching more people have been put forward within the project through the development of a web version (see

http://www.oekobeichtstuhl.ch) and a mobile application [

27]. Experiences gained from integrating the Eco-Confessional with school education has also shown to be promising, as the game can be used as a motivating entrance point for starting a discussion on sustainable lifestyles. Further research is proposed on how the Eco-Confessional or similar serious games can support sustainable lifestyle education in a learning environment, e.g., schools, in contrast to the free-choice learning experience.

The authors see further applications of the Eco-Confessional concept through adapting the functionality to address more specific issues in the context of sustainable lifestyles, e.g., impact of food consumption on climate change.

Focusing on certain environmental impacts (e.g., greenhouse gas emissions or water consumption) could improve the Eco-Confessional by making the results easier to understand and by avoiding weighting associated with the ecological scarcity methodology (see above). Using the eco-confessional in other cultural contexts, without familiarity with the religious concept of sins and indulgence, would also require an adaptation of the game logic and general wording.

Although the potential for reaching a wider audience through an exhibit and serious games like the Eco-Confessional will stay limited, the general approach of providing LCA-information through the direct comparison of different lifestyle choices is promising in the context of sustainability and environmental education, and should be further elaborated.