The Relationship between Psychological Contract Breach and Job Insecurity or Stress in Employees Engaged in the Restaurant Business

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design and Setting

2.2. Study Hypothesis

2.3. Questionnaire Survey

2.4. Data Collection

2.5. Statistical Analysis of Data

3. Results

3.1. Baseline Characteristics of the Respondents

3.2. Factors Affecting Job Insecurity or Stress

3.3. Reliability and Validity of Outcome Measures

3.4. Hypothesis Testing

4. Discussion

- (1)

- As shown in the current results, job insecurity had a significant positive effect on psychological contract breach. According to a review of previous published studies in this series, the seriousness of threat due to a loss of job and a feeling of helplessness as a response to such threat had a significant effect on psychological contract breach [11,19,33]. To put this another way, significant correlations between the two variables confirmed that the job insecurity of employees who are intimidated by the loss of a job had a significant effect on the degree of compensation that they implicitly expect;

- (2)

- Job insecurity had a significant positive effect on job stress. It was therefore demonstrated that job insecurity had a significant effect on stress responses [3,7,26,30]. In more detail, job insecurity is a definite variable that determines job stress. It can therefore be inferred that a higher degree of job insecurity is closely associated with that of job stress [21,28];

- (3)

- Psychological contract breach had a significant positive effect on job stress. According to a review of the literature, stress responses had a significant effect on psychological contract breach [16,17,27]. Moreover, there was a significant correlation between the two variables. To put this another way, psychological contract breach is a variable that affects job stress [23,34]. It may also be described as a factor affecting the sustainability of human resources;

- (4)

- Psychological contract breach mediated the interaction between job insecurity and stress. It has been reported that psychological contract breach is involved in the relationship between job insecurity and organizational citizenship behavior. Moreover, there have also been attempts to demonstrate the effects of psychological contract breach as a moderating variable, thus exploring whether there was a significant correlation between role stress and organizational commitment [11,28,31,35,36]. This is in agreement with our results showing that psychological contract breach was a causative factor affecting job insecurity.

- (1)

- The job environment of employees engaged in the restaurant business should be appropriately managed and its stability should be assured, for which the corresponding organization should be managed for the stabilization of their working environment;

- (2)

- Considerable efforts should be made to stabilize the job environment of employees engaged in the restaurant business; an instability of their working environment serves as a factor causing physiological and psychological stress to them;

- (3)

- Rational criteria for rewarding the business performance of employees engaged in the restaurant business. It would therefore be mandatory to establish rational criteria for compensating any loss that employees engaged in the restaurant business sustained when they were exposed to psychological contract breach;

- (4)

- Employees engaged in the restaurant business consider the stability of the organization as a primary concern; they have a tendency not to be stabilized rather than to be threatened in the organization, while avoiding physiological and psychological stress as a response to psychological contract breach.

- (1)

- We failed to clarify the effects of job insecurity of those who are engaged in restaurant business, arising from changes in the external environment, on other variables;

- (2)

- We performed a self-administered questionnaire for those who are located in Seoul, Korea only. It would therefore be mandatory to conduct further nationwide studies;

- (3)

- We clarified effects arising from a causalrelationship as well as the relevant mediating ones, but we failed to consider moderating variables. This remains regrettable. It would therefore be mandatory to consider moderating variables in assessing the effects of psychological contract breach of those who are engaged in the restaurant business on their job insecurity and stress;

- (4)

- In the current study, psychological contract breach and job stress served as outcome measures that are dependent on job insecurity. However, this is associated with the simplification of the outcomes of job insecurity. Further studies are therefore warranted to consider dependent variables that are associated with job insecurity;

- (5)

- We failed to identify the components of job insecurity affecting psychological contract breach and job stress to the greatest extent. This also remains regrettable. Further studies are therefore warranted to explore detailed components of job insecurity;

- (6)

- We failed to analyze the possible effects of age or turnover on job insecurity or stress. This deserves further study.

5. Conclusions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- César, C. Strategic attitudes and information technologies in the hospitality business: An empirical analysis. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2000, 19, 125–143. [Google Scholar]

- Egon, S. The impact of globalization on small and medium enterprises: New challenges for tourism policies in European countries. Tour. Manag. 1998, 19, 371–380. [Google Scholar]

- Benoît, D.; Xavier, L. Business Model Evolution: In Search of Dynamic Consistency. Long Range Plan. 2010, 43, 227–246. [Google Scholar]

- Laurent, B.; Walter, B.; Gérard, C. Plural forms versus franchise and company-owned systems: A DEA approach of hotel chain performance. Omega 2009, 37, 566–578. [Google Scholar]

- Ian, P.H.; Will, B.S. Shared services as a new organisational form: Some implications for management accounting. Br. Account. Rev. 2012, 44, 83–97. [Google Scholar]

- Terry, M.; Roberta, S. Rural development and the regional state: Denying multifunctional agriculture in the UK. J. Rural Stud. 2008, 24, 422–431. [Google Scholar]

- Allen, W.H.; George, M.R. Status of engineering geology in North America and Europe. Eng. Geol. 1997, 47, 191–215. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, C.J.; Huang, J.W. Strategic human resource practices and innovation performance—The mediating role of knowledge management capacity. J. Bus. Res. 2009, 62, 104–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sohel, A.; Roger, G.S. The impact of human resource management practices on operational performance: Recognizing country and industry differences. J. Oper. Manag. 2003, 21, 19–43. [Google Scholar]

- Ian, N.L. Internal market orientation: Construct and consequences. J. Bus. Res. 2004, 57, 405–413. [Google Scholar]

- Hale, K. The relationship between total quality management practices and their effects on firm performance. J. Oper. Manag. 2003, 21, 405–435. [Google Scholar]

- Rousseau, D. Psychological and implied contracts in organizations. Empl. Responsib. Rights J. 1989, 2, 121–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bal, P.M.; De Lange, A.H.; Jansen, P.G.W. Psychological contract breach and job attitudes: A meta-analysis of age as a moderator. J. Vocat. Behav. 2008, 72, 143–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neil, C.; David, G.; Linda, T. Testing the differential effects of changes in psychological contract breach and fulfillment. J. Vocat. Behav. 2011, 79, 267–276. [Google Scholar]

- Vincent, C.; Rob, B.B. The relationship between psychological contract breach and organizational commitment: Exchange imbalance as a moderator of the mediating role of violation. J. Vocat. Behav. 2011, 78, 283–289. [Google Scholar]

- Chiu, S.F.; Peng, J.C. The relationship between psychological contract breach and employee deviance: The moderating role of hostile attributional style. J. Vocat. Behav. 2008, 73, 426–433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiang, C.F.; Hsieh, T.S. The impacts of perceived organizational support and psychological empowerment on job performance: The mediating effects of organizational citizenship behavior. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2012, 31, 180–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paul, F.B.; Glenn, M.M. Strategy, human resource management and performance: Sharpening line of sight. Hum. Resour. Manag. Rev. 2012, 22, 43–56. [Google Scholar]

- Lau, C.M.; Ngo, H.Y. The HR system, organizational culture, and product innovation. Int. Bus. Rev. 2004, 13, 685–703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Melih, A.; Secil, B.K.; Renin, V. A qualitative study of coping strategies in the context of job insecurity. Procedia Soc. Behav. Sci. 2011, 24, 421–434. [Google Scholar]

- Jennifer, J.K.; James, R.D.; Linda, K.T.; Amy, C.E. Silenced by fear: The nature, sources, and consequences of fear at work. Res. Organ. Behav. 2009, 29, 163–193. [Google Scholar]

- Lauren, A.K.; Peter, A.H. The potential role of mindsets in unleashing employee engagement. Hum. Resour. Manag. Rev. 2015, 25, 329–341. [Google Scholar]

- Ouyang, Z.; Sang, J.; Li, P. Organizational justice and job insecurity as mediators of the effect of emotional intelligence on job satisfaction: A study from China. Personal. Individ. Differ. 2015, 76, 147–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murat, Y.; Ali, Ö.K.; Muhtesem, B. An Empirical Research on the Relationship between Job Insecurity, Job Related Stress and Job Satisfaction in Logistics Industry. Procedia Soc. Behav. Sci. 2013, 99, 332–338. [Google Scholar]

- Ka, H.M. Marketizing higher education in post-Mao China. Int. J. Educ. Dev. 2008, 20, 109–126. [Google Scholar]

- Greg, S.; Larry, Y.; Alex, K.A. Crisis management and recovery how Washington, D.C., hotels responded to terrorism. Cornell Hosp. Q. 2002, 43, 27–40. [Google Scholar]

- Robert, N.M. Increasing productivity in global firms: The CEO challenge. J. Int. Manag. 2009, 15, 262–272. [Google Scholar]

- Dong, J.K.; Woo, G.K.; Jin, S.H. A perceptual mapping of online travel agencies and preference attributes. Tour. Manag. 2007, 28, 591–603. [Google Scholar]

- Yee, R.W.; Yeung, A.C.; Cheng, T.E. The impact of employee satisfaction on quality and profitability in high-contact service industries. J. Oper. Manag. 2008, 26, 651–668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Christopher, W.B.; Linda, J.S. Corporate social responsibility as a source of employee satisfaction. Res. Organ. Behav. 2012, 32, 63–86. [Google Scholar]

- Vishal, M. Impact of consumer empowerment on online trust: An examination across genders. Decis. Support Syst. 2012, 54, 198–205. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, M.; Park, J. The effects of the employees’ psychological contract violation based on employment instability of hotel enterprise on mindfulness and job stress. J. Tour. Hosp. Stud. 2018, 7, 41–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sajid, B.; Misbah, N. Breach of psychological contract, organizational cynicism and union commitment: A study of hospitality industry in Pakistan. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2013, 34, 61–65. [Google Scholar]

- Simon, L.D.R.; Prashant, B.; Sarbari, B. Investigating the role of psychological contract breach on career success: Convergent evidence from two longitudinal studies. J. Vocat. Behav. 2011, 79, 428–437. [Google Scholar]

- Émilie, L.; Christian, V.; Jean-Sébastien, B. Psychological contract breach, affective commitment to organization and supervisor, and newcomer adjustment: A three-wave moderated mediation model. J. Vocat. Behav. 2013, 83, 528–538. [Google Scholar]

- Pascal, P.; Mejía-Morelos, J.H. Antecedents of pro-environmental behaviours at work: The moderating influence of psychological contract breach. J. Environ. Psychol. 2014, 38, 124–131. [Google Scholar]

| Variables | Values | |

|---|---|---|

| Age (years old) | 20–29 | 163 (42.4%) |

| 30–39 | 137 (35.7%) | |

| 40–49 | 63 (16.4%) | |

| 50–59 | 21 (5.5%) | |

| Sex | Men | 183 (47.7%) |

| Women | 201 (52.3%) | |

| Years of education | High school | 114 (29.7%) |

| College | 129 (33.6%) | |

| University | 88 (22.9%) | |

| Graduate school | 53 (13.8%) | |

| Position | Ordinary employee | 168 (43.8%) |

| Assistant manager | 75 (19.5%) | |

| Manager | 86 (22.4%) | |

| Deputy general manager | 33 (8.6%) | |

| General manager | 19 (4.9%) | |

| Director | 3 (0.8%) | |

| Years of working (years) | <5 | 244 (63.5%) |

| 5–10 | 125 (32.6%) | |

| 11–20 | 14 (3.6%) | |

| >20 | 1 (0.3%) | |

| The frequency of turnover | <5 | 279 (72.7%) |

| 1–5 | 63 (16.4%) | |

| 6–10 | 33 (8.6%) | |

| 11–20 | 7 (1.8%) | |

| >21 | 2 (0.5%) | |

| Outcome Measures | The Initial Number of Questions | The Final Number of Questions | Cronbach’s α |

|---|---|---|---|

| Job Insecurity | 7 | 5 | 0.937 |

| Job Stress | 3 | 2 | 0.859 |

| Psychological Contract Breach | 2 | 2 | 0.862 |

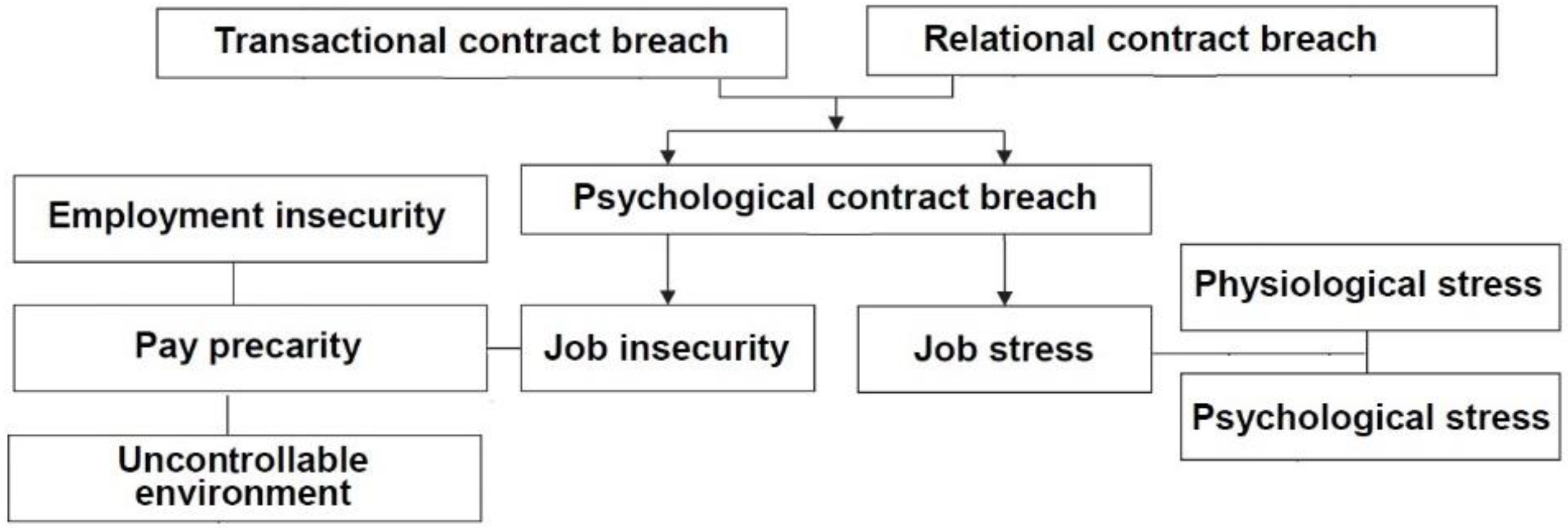

| Outcome Measures | Measurement Variables | URC | FL | CR (t) | SMC | AVE | CR |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Job Insecurity | Employment insecurity | 0.929 | 0.833 | 25.526 | 0.759 | 0.532 | 0.947 |

| Pay precarity | 0.986 | 0.929 | 25.368 | 0.824 | |||

| Uncontrollable environment | 0.921 | 0.847 | 24.948 | 0.748 | |||

| Job Stress | Physiological stress | 0.844 | 0.733 | 13.621 | 0.548 | 0.518 | 0.925 |

| Psychological stress | 0.908 | 0.785 | 14.159 | 0.619 | |||

| Psychological Contract Breach | Transactional contract breach | 0.914 | 0.710 | 15.168 | 0.519 | 0.576 | 0.918 |

| Relational contract breach | 0.937 | 0.816 | 20.507 | 0.644 |

| Outcome Measures | Job Insecurity | Job Stress | Psychological Contract Breach | Mean | Standard Deviation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Job Insecurity | 1.000 | 3.495 | 0.518 | ||

| Job Stress | 0.687 *** | 1.000 | 3.554 | 0.623 | |

| Psychological Contract Breach | 0.672 *** | 0.648 *** | 1.000 | 3.589 | 0.678 |

| Hypothesis | Path | PC | CR (t) | SMC | Results |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Job insecurity → Psychological contract breach | 0.314 | 4.476 *** | 0.459 | Accept |

| 2 | Job insecurity → Job stress | 0.409 | 7.198 *** | 0.447 | Accept |

| 3 | Psychological contract breach → Job stress | 0.187 | 2.417 ** | 0.453 | Accept |

| 4 | Job insecurity → Job stress viapsychological contract breach | 0.179 | 2.198 * | 0.536 | Accept |

© 2019 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Shin, H.C. The Relationship between Psychological Contract Breach and Job Insecurity or Stress in Employees Engaged in the Restaurant Business. Sustainability 2019, 11, 5709. https://doi.org/10.3390/su11205709

Shin HC. The Relationship between Psychological Contract Breach and Job Insecurity or Stress in Employees Engaged in the Restaurant Business. Sustainability. 2019; 11(20):5709. https://doi.org/10.3390/su11205709

Chicago/Turabian StyleShin, Hyoung Chul. 2019. "The Relationship between Psychological Contract Breach and Job Insecurity or Stress in Employees Engaged in the Restaurant Business" Sustainability 11, no. 20: 5709. https://doi.org/10.3390/su11205709

APA StyleShin, H. C. (2019). The Relationship between Psychological Contract Breach and Job Insecurity or Stress in Employees Engaged in the Restaurant Business. Sustainability, 11(20), 5709. https://doi.org/10.3390/su11205709