Emerging Urban Forests: Opportunities for Promoting the Wild Side of the Urban Green Infrastructure

Abstract

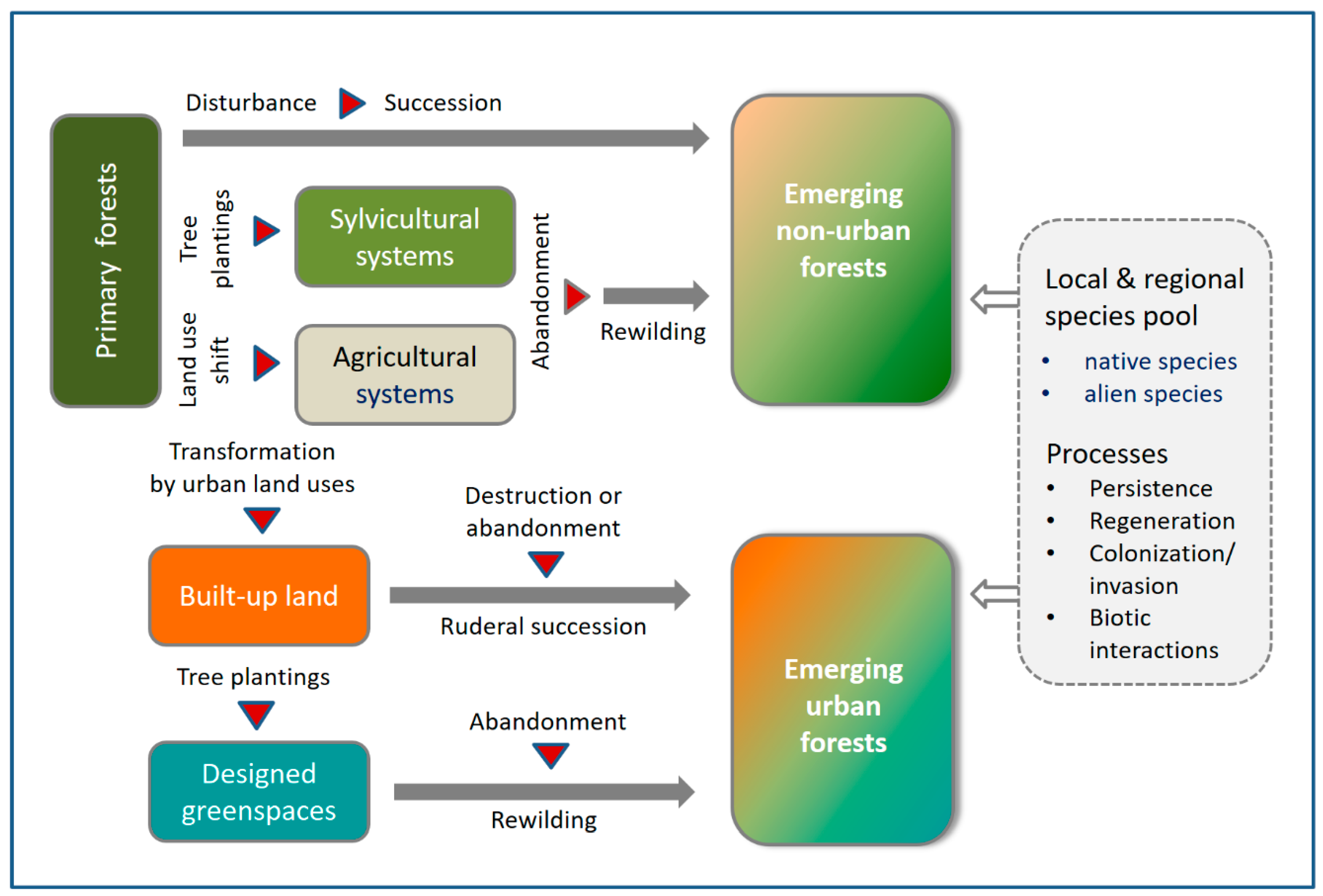

:1. Introduction

2. Methods

2.1. Study Region and Study System

2.2. Analyses at the Landscape Scale

2.3. Analyses at the Community Scale

2.4. Statistical Analyses

2.4.1. Landscape Scale

2.4.2. Community Scale

3. Results

3.1. Successional Forests at the Landscape Scale

3.2. Biodiversity Patterns at the Community Scale

3.2.1. Biodiversity Measures across Forest Types

3.2.2. Species Assemblages across Forest Types

3.2.3. Relation between Native and Alien Plant Richness

4. Discussion

4.1. Successional Forests at the Landscape Scale

4.2. Biodiversity Patterns at the Community Scale

4.2.1. Total, Native, and Alien Richness

4.2.2. Community Structure

4.2.3. Successional Trends

4.2.4. Endangered Species

5. Conclusions on the Role of Emerging Forests for Urban Green Infrastructure

- Preserve native biodiversity and populations of endangered species. All types of emerging urban forests harbored a considerable number of native plant and invertebrate species—despite a considerable share of alien species. Their role as habitat for endangered species was limited but may increase with time. Yet most likely, the emerging urban forests will not be able to approach natural forest remains in the near future. This strongly supports the well-established aim of placing the highest priority on protecting natural forest remnants in cities, e.g., [21], and indicates as well some opportunities for native species in novel urban settings.

- Create ecological networks with stepping stones or corridors for plants and animals. While ecological network functions were not studied here, emerging urban forests likely support ecological networks by providing forest patches dispersed over the urban fabric that may be used as stepping stones for birds and other animals [42,140]. Since the alien Robinia forests harbored similar numbers of (endangered) invertebrates as the other forest types, they also contribute to ecological networks, e.g., for pollinators [183] or at higher trophic levels [95,144].

- Facilitate and elucidate the adaptation of ecological systems to urbanization and other environmental pressures. Urbanization as a major driver of change in the Anthropocene period affects all components of urban ecosystems [184]. In consequence, novel urban ecosystems arise and support the understanding of how species assembly responds to a combination of novel environmental drivers in urban settings [141,185]. Allowing emerging forests to develop without intervening in the diversity patterns of alien and native species will provide insights into the adaptation of forest systems to changing urban environments, including interactions with climate change effects; and will allow conclusions to be drawn on the resilience of species and communities to urban pressures, and selection of suitable native or alien species for urban greenspaces.

- Re-connect people with nature and support experience of natural elements. The diversity of both species assemblages and structural features of emerging urban forests and their adjacency to urban residents create manifold opportunities to experience natural elements and their dynamics in the neighborhood. This is an important service in times of decreasing experience in nature [186], with anticipated positive feedbacks to people’s willingness to protect biodiversity [187], and a strong argument for conserving emerging forests close to places where people live [188].

- Enhance wilderness in cities. Since wilderness areas significantly decline at a global scale [2], the aim of promoting wilderness areas in urban environments—complementing the highly managed ecosystems in public and private greenspaces—is on the urban agenda [70]. Emerging urban forests represent a kind of “novel urban wilderness,” with species assemblages contrasting with the “ancient wilderness” of natural forest remnants but similarly shaped by natural processes [104]. While ancient wilderness areas are usually located at the urban fringe, emerging urban forests are often integrated into the urban fabric and thus can support access to wilderness in the daily life of urban residents.

- Provide ecosystem services for urban people. There is increasing evidence of positive feedback between biodiversity and the provision of ecosystem services in cities [189]. Emerging forests in particular, including abundant alien tree species, have been shown to provide a range of regulating ecosystem services on vacant land [44,46]. Moreover, they constitute informal greenspaces [190] supporting manifold social uses and cultural services [191,192,193]. Importantly, these ecosystem services are being delivered without the use of resources to produce plants and carry out landscaping and maintenance; thus they have a low CO2 footprint. Integrating emerging forests into the urban green infrastructure therefore also contributes to both climate change mitigation and adaptation.

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Hedblom, M.; Soderstrom, B. Woodlands across Swedish urban gradients: Status, structure and management implications. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2008, 84, 62–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ellis, E.C. Ecology in an anthropogenic biosphere. Ecol. Monogr. 2015, 85, 287–331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Y.Y.; Li, S.Y.; Yu, S.X. Monitoring urban expansion and its effects on land use and land cover changes in Guangzhou city, China. Environ. Monit. Assess. 2016, 188, 54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Croci, S.; Butet, A.; Georges, A.; Aguejdad, R.; Clergeau, P. Small urban woodlands as biodiversity conservation hot-spot: A multi-taxon approach. Landsc. Ecol. 2008, 23, 1171–1186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grigorescu, I.; Geacu, S. The dynamics and conservation of forest ecosystems in Bucharest Metropolitan Area. Urban For. Urban Green. 2017, 27, 90–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Konijnendijk, C.C. The Forest and the City. The Cultural Landscape of Urban Woodland, 2nd ed.; Springer: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Nesbitt, L.; Hotte, N.; Barron, S.; Cowan, J.; Sheppard, S.R.J. The social and economic value of cultural ecosystem services provided by urban forests in North America: A review and suggestions for future research. Urban For. Urban Green. 2017, 25, 103–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Endreny, T.A. Strategically growing the urban forest will improve our world. Nat. Commun. 2018, 9, 1160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fischer, L.K.; Honold, J.; Cvejic, R.; Delshammar, T.; Hilbert, S.; Lafortezza, R.; Nastran, M.; Nielsen, A.B.; Pintar, M.; van der Jagt, A.P.N.; et al. Beyond green: Broad support for biodiversity in multicultural European cities. Glob. Environ. Chang. 2018, 49, 35–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jim, C.Y. Conservation and Creation of Urban Woodlands. In Greening Cities; Tan, P., Jim, C., Eds.; Advances in 21st Century Human Settlements; Springer: Singapore, 2017; pp. 307–330. [Google Scholar]

- Yao, N.; Konijnendijk van den Bosch, C.C.; Yang, J.; Devisscher, T.; Wirtz, Z.; Jia, L.; Duan, J.; Ma, L. Beijing’s 50 million new urban trees: Strategic governance for large-scale urban afforestation. Urban For. Urban Green. 2019, 44, 126392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toni, S.A.; Duinker, P.N. A framework for urban-woodland naturalization in Canada. Environ. Rev. 2015, 23, 321–336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zipperer, W.C. Species composition and structure of regenerated and remnant forest patches within an urban landscape. Urban Ecosyst. 2002, 6, 271–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kowarik, I. Wild Urban Woodlands: Towards a Conceptual Framework. In Wild Urban Woodlands. New Perspectives for Urban Forestry; Kowarik, I., Körner, S., Eds.; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2005; pp. 1–32. [Google Scholar]

- Pougy, N.; Martins, E.; Verdi, M.; de Oliveira, J.A.; Maurenza, D.; Amaro, R.; Martinelli, G. Urban forests and the conservation of threatened plant species: The case of the Tijuca National Park, Brazil. Nat. Conserv. 2014, 12, 170–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clews, E.; Corlett, R.T.; Ho, J.K.I.; Kim, D.E.; Koh, C.Y.; Liong, S.-Y.; Meier, R.; Memory, A.; Ramchunder, S.; Sin, T.M.; et al. The biological, ecological and conservation significance of freshwater swamp forest in Singapore. Gard. Bull. Singap. 2018, 70, 9–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rudnicky, J.L.; McDonnell, M.J. 48 Years of Canopy Change in a Hardwood-Hemlock Forest in New-York-City. Bull. Torrey Bot. Club 1989, 116, 52–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Godefroid, S.; Koedam, N. How important are large vs. small forest remnants for the conservation of the woodland flora in an urban context? Glob. Ecol. Biogeogr. 2003, 12, 287–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mandryk, A.M.; Wein, R.W. Exotic vascular plant invasiveness and forest invasibility in urban boreal forest types. Biol. Invasions 2006, 8, 1651–1662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Korzhinevskaya, A.A.; Veselkin, D.V. The Richness and Cover of Alien Plants in the Undergrowth and Field Layer of Urbanized Southern Taiga Forests. KnE Life Sci. 2018, 95–103. [Google Scholar]

- Godefroid, S.; Koedam, N. Distribution pattern of the flora in a peri-urban forest: An effect of the city-forest ecotone. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2003, 65, 169–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dyderski, M.K.; Tyborski, J.; Jagodzinski, A.M. The utility of ancient forest indicator species in urban environments: A case study from Poznan, Poland. Urban For. Urban Green. 2017, 27, 76–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kowarik, I.; von der Lippe, M. Plant population success across urban ecosystems: A framework to inform biodiversity conservation in cities. J. Appl. Ecol. 2018, 55, 2354–2361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toft, R.J.; Ford, D.E.; Sullivan, J.J.; Stewart, G.H. Invertebrates of an urban old growth forest are different from forest restoration and garden communities. N. Z. J. Ecol. 2019, 43, 3350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salvati, L.; Ranalli, F.; Carlucci, M.; Ippolito, A.; Ferrara, A.; Corona, P. Forest and the city: A multivariate analysis of peri-urban forest land cover patterns in 283 European metropolitan areas. Ecol. Indic. 2017, 73, 369–377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oldfield, E.E.; Warren, R.J.; Felson, A.J.; Bradford, M.A. Challenges and future directions in urban afforestation. J. Appl. Ecol. 2013, 50, 1169–1177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, L.R.; Handel, S.N. Restoration treatments in urban park forests drive long-term changes in vegetation trajectories. Ecol. Appl. 2016, 26, 940–956. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McPhearson, P.T.; Feller, M.; Felson, A.; Karty, R.; Lu, J.W.T.; Palmer, M.I.; Wenskus, T. Assessing the Effects of the Urban Forest Restoration Effort of MillionTreesNYC on the Structure and Functioning of New York City Ecosystems. Cities Environ. 2010, 3, 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wallace, K.J.; Clarkson, B.D. Urban forest restoration ecology: A review from Hamilton, New Zealand. J. R. Soc. N. Z. 2019, 49, 347–369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hotta, K.; Ishii, H.; Sasaki, T.; Doi, N.; Azuma, W.; Oyake, Y.; Imanishi, J.; Yoshida, H. Twenty-one years of stand dynamics in a 33-year-old urban forest restoration site at Kobe Municipal Sports Park, Japan. Urban For. Urban Green. 2015, 14, 309–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simmons, B.L.; Hallett, R.A.; Sonti, N.F.; Auyeung, D.S.N.; Lu, J.W.T. Long-term outcomes of forest restoration in an urban park. Restor. Ecol. 2016, 24, 109–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, X.Y.; Li, W.L.; Da, L.J. Near-Natural Silviculture: Sustainable Approach for Urban Renaturalization? Assessment Based on 10 Years Recovering Dynamics and Eco-Benefits in Shanghai. J. Urban. Plan. Dev. 2015, 141, A5015001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, E.C.; Minor, E.S. Vacant lots: An underexplored resource for ecological and social benefits in cities. Urban For. Urban Green. 2017, 21, 146–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rink, D.; Arndt, T. Investigating perception of green structure configuration for afforestation in urban brownfield development by visual methods. A case study in Leipzig, Germany. Urban For. Urban Green. 2016, 15, 65–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sasaki, T.; Ishii, H.; Morimoto, Y. Evaluating restoration success of a 40-year-old urban forest in reference to mature natural forest. Urban For. Urban Green. 2018, 32, 123–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peterken, G.F. Woodland Conservation and Management; Chapman and Hall: London, UK; New York, NY, USA, 1981; 328p. [Google Scholar]

- Prach, K.; Pyšek, P.; Bastl, M. Spontaneous vegetation succession in human-disturbed habitats: A pattern across seres. Appl. Veg. Sci. 2001, 4, 83–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lugo, A.E.; Helmer, E. Emerging forests on abandoned land: Puerto Rico’s new forests. For. Ecol. Manag. 2004, 190, 145–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Thorn, S.; Bassler, C.; Brandl, R.; Burton, P.J.; Cahall, R.; Campbell, J.L.; Castro, J.; Choi, C.Y.; Cobb, T.; Donato, D.C.; et al. Impacts of salvage logging on biodiversity: A meta-analysis. J. Appl. Ecol. 2018, 55, 279–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kowarik, I. Vegetationsentwicklung auf innerstädtischen Brachflächen. Beispiele aus Berlin (West). Tuexenia 1986, 6, 75–98. [Google Scholar]

- Kunick, W. Spontaneous Woody Vegetation in Cities. In Urban Ecology: Plants and Plant Communities in Urban Environments; Sukopp, H., Hejny, S., Kowarik, I., Eds.; SPB Academic Publishing: The Hague, The Netherlands, 1990; pp. 167–174. [Google Scholar]

- Bonthoux, S.; Brun, M.; Di Pietro, F.; Greulich, S.; Bouche-Pillon, S. How can wastelands promote biodiversity in cities? A review. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2014, 132, 79–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prach, K.; Řehounková, K.; Lencová, K.; Jírová, A.; Konvalinková, P.; Mudrák, O.; Študent, V.; Vaněček, Z.; Tichý, L.; Petřík, P.; et al. Vegetation succession in restoration of disturbed sites in Central Europe: The direction of succession and species richness across 19 seres. Appl. Veg. Sci. 2014, 17, 193–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, G.; Miller, P.A.; Nowak, D.J. Assessing urban vacant land ecosystem services: Urban vacant land as green infrastructure in the City of Roanoke, Virginia. Urban For. Urban Green. 2015, 14, 519–526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sitzia, T.; Campagnaro, T.; Weir, R.G. Novel woodland patches in a small historical Mediterranean city: Padova, Northern Italy. Urban Ecosyst. 2016, 19, 475–487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riley, C.B.; Herms, D.A.; Gardiner, M.M. Exotic trees contribute to urban forest diversity and ecosystem services in inner-city Cleveland, OH. Urban For. Urban Green. 2018, 29, 367–376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, A.L.; Borowy, D.; Swan, C.M. Land use history and seed dispersal drive divergent plant community assembly patterns in urban vacant lots. J. Appl. Ecol. 2018, 55, 451–460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Westermann, J.R.; von der Lippe, M.; Kowarik, I. Seed traits, landscape and environmental parameters as predictors of species occurrence in fragmented urban railway habitats. Basic Appl. Ecol. 2011, 12, 29–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trentanovi, G.; von der Lippe, M.; Sitzia, T.; Ziechmann, U.; Kowarik, I.; Cierjacks, A. Biotic homogenization at the community scale: Disentangling the roles of urbanization and plant invasion. Divers. Distrib. 2013, 19, 738–748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Dettmar, J. Forest for shrinking cities. In Wild Urban Woodlands. New Perspectives for Urban Forestry; Kowarik, I., Körner, S., Eds.; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2005; pp. 263–277. [Google Scholar]

- Kowarik, I.; Körner, S. Wild Urban Woodlands. New Perspectives for Urban Forestry; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2005; 299p. [Google Scholar]

- Weiss, J.; Burghardt, W.; Gausmann, P.; Haag, R.; Haupler, H.; Hamann, M.; Leder, B.; Schulte, A.; Stempelmann, I. Nature Returns to Abandoned Industrial Land: Monitoring Succession in Urban-Industrial Woodlands in the German Ruhr. In Wild Urban Woodlands. New Perspectives for Urban Forestry; Kowarik, I., Körner, S., Eds.; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2005; pp. 143–162. [Google Scholar]

- Rebele, F.; Lehmann, C. Restoration of a landfill site in Berlin, Germany by spontaneous and directed succession. Restor. Ecol. 2002, 10, 340–347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rebele, F.; Lehmann, C. Twenty years of woodland establishment through natural succession on a sandy landfill site in Berlin, Germany. Urban For. Urban Green. 2016, 18, 182–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corlett, R.T. Restoration, Reintroduction, and Rewilding in a Changing World. Trends Ecol. Evol. 2016, 31, 453–462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zerbe, S. Restoration of natural broad-leaved woodland in Central Europe on sites with coniferous forest plantations. For. Ecol. Manag. 2002, 167, 27–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gonzalez, E.; Masip, A.; Tabacchi, E. Poplar plantations along regulated rivers may resemble riparian forests after abandonment: A comparison of passive restoration approaches. Restor. Ecol. 2016, 24, 538–547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vojta, J. Relative importance of historical and natural factors influencing vegetation of secondary forests in abandoned villages. Preslia 2007, 79, 223–244. [Google Scholar]

- Pandi, I.; Penksza, K.; Botta-Dukat, Z.; Kroel-Dulay, G. People move but cultivated plants stay: Abandoned farmsteads support the persistence and spread of alien plants. Biodivers. Conserv. 2014, 23, 1289–1302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gilbert, O.L. The Ecology of Urban Habitats; Chapman and Hall: London, UK; New York, NY, USA, 1989; 369p. [Google Scholar]

- Cloke, P.; Jones, O. Turning in the graveyard: Trees and the hybrid geographies of dwelling, monitoring and resistance in a Bristol cemetery. Cult. Geogr. 2004, 11, 313–341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kowarik, I.; Buchholz, S.; von der Lippe, M.; Seitz, B. Biodiversity functions of urban cemeteries: Evidence from one of the largest Jewish cemeteries in Europe. Urban For. Urban Green. 2016, 19, 68–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gandy, M. The fly that tried to save the world: Saproxylic geographies and other-than-human ecologies. T I Brit. Geogr. 2019, 44, 392–406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pregitzer, C.C.; Charlop-Powers, S.; Bibbo, S.; Forgione, H.M.; Gunther, B.; Hallett, R.A.; Bradford, M.A. A city-scale assessment reveals that native forest types and overstory species dominate New York City forests. Ecol. Appl. 2019, 29, e01819. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schadek, U.; Strauss, B.; Biedermann, R.; Kleyer, M. Plant species richness, vegetation structure and soil resources of urban brownfield sites linked to successional age. Urban Ecosyst. 2009, 12, 115–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prach, K. Spontaneous succession in Central-European man-made habitats: What information can be used in restoration practice? Appl. Veg. Sci. 2003, 6, 125–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walker, L.R.; Walker, J.; Hobbs, R.J. Linking Restoration and Ecological Succession; Springer: London, UK, 2007; 188p. [Google Scholar]

- Prach, K.; Hobbs, R.J. Spontaneous succession versus technical reclamation in the restoration of disturbed sites. Restor. Ecol. 2008, 16, 363–366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pettorelli, N.; Durant, S.M.; du Troit, J.T. Rewilding; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2019; 437p. [Google Scholar]

- McKinney, M.; Kowarik, I.; Kendal, D. Wild urban ecosystems: Challenges and opportunities for urban development. Urban For. Urban Green. 2018, 29, 334–403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hwang, Y.H.; Yue, Z.E.J.; Ling, S.K.; Tan, H.H.V. It’s ok to be wilder: Preference for natural growth in urban green spaces in a tropical city. Urban For. Urban Green. 2019, 38, 165–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borgmann, K.L.; Rodewald, A.D. Forest restoration in urbanizing landscapes: Interactions between land uses and exotic shrubs. Restor. Ecol. 2005, 13, 334–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sullivan, J.J.; Meurk, C.; Whaley, K.J.; Simcock, R. Restoring native ecosystems in urban Auckland: Urban soils, isolation, and weeds as impediments to forest establishment. N. Z. J. Ecol. 2009, 33, 60–71. [Google Scholar]

- Ishii, H.; Ichinose, G.; Ohsugi, Y.; Iwasaki, A. Vegetation recovery after removal of invasive Trachycarpus fortunei in a fragmented urban shrine forest. Urban For. Urban Green. 2016, 15, 53–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaertner, M.; Wilson, J.R.U.; Cadotte, M.W.; MacIvor, J.S.; Zenni, R.D.; Richardson, D.M. Non-native species in urban environments: Patterns, processes, impacts and challenges. Biol. Invasions 2017, 19, 3461–3469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Chocholoušková, Z.; Pyšek, P. Changes in composition and structure of urban flora over 120 years: A case study of the city of Plzeň. Flora 2003, 198, 366–376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Knapp, S.; Kühn, I.; Stolle, J.; Klotz, S. Changes in the functional composition of a Central European urban flora over three centuries. Perspect. Plant. Ecol. 2010, 12, 235–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dyderski, M.K.; Gdula, A.K.; Jagodzinski, A.M. “The rich get richer” concept in riparian woody species—A case study of the Warta River Valley (Poznan, Poland). Urban For. Urban Green. 2015, 14, 107–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kowarik, I.; von der Lippe, M.; Cierjacks, A. Prevalence of alien versus native species of woody plants in Berlin differs between habitats and at different scales. Preslia 2013, 85, 113–132. [Google Scholar]

- Duguay, S.; Eigenbrod, F.; Fahrig, L. Effects of surrounding urbanization on non-native flora in small forest patches. Landsc. Ecol. 2007, 22, 589–599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- LaPaix, R.; Harper, K.; Freedman, B. Patterns of exotic plants in relation to anthropogenic edges within urban forest remnants. Appl. Veg. Sci. 2012, 15, 525–535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sukopp, H.; Blume, H.P.; Elvers, H.; Horbert, M. Beiträge zur Stadtökologie von Berlin (West). Landsch. Umweltforsch. 1980, 3, 1–225. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, G. Assessing Urban Forest Structure, Ecosystem Services, and Economic Benefits on Vacant Land. Sustainability 2016, 8, 679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- MacDougall, A.S.; Turkington, R. Are invasive species the drivers or passengers of change in degraded ecosystems? Ecology 2005, 86, 42–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Dyderski, M.K.; Jagodzinski, A.M. Context-Dependence of Urban Forest Vegetation Invasion Level and Alien Species’ Ecological Success. Forests 2019, 10, 26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Stewart, G.H.; Meurk, C.D.; Ignatieva, M.E.; Buckley, H.L.; Magueur, A.; Case, B.S.; Hudson, M.; Parker, M. Urban Biotopes of Aotearoa New Zealand (URBANZ) II: Floristics, biodiversity and conservation values of urban residential and public woodlands, Christchurch. Urban For. Urban Green. 2009, 8, 149–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buchholz, S.; Tietze, H.; Kowarik, I.; Schirmel, J. Effects of a Major Tree Invader on Urban Woodland Arthropods. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0137723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stewart, G.H.; Ignatieva, M.E.; Meurk, C.D.; Earl, R.D. The re-emergence of indigenous forest in an urban environment, Christchurch, New Zealand. Urban For. Urban Green. 2004, 2, 149–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pergl, J.; Sádlo, J.; Petřík, P.; Danihelka, J.; Chrtek, J.; Hejda, M.; Moravcová, L.; Perglová, I.; Štajerová, K.; Pyšek, P. Dark side of the fence: Ornamental plants as a source of wild-growing flora in the Czech Republic. Preslia 2016, 88, 163–184. [Google Scholar]

- Mayer, K.; Haeuser, E.; Dawson, W.; Essl, F.; Kreft, H.; Pergl, J.; Pyšek, P.; Weigelt, P.; Winter, M.; Lenzner, B.; et al. Naturalization of ornamental plant species in public green spaces and private gardens. Biol. Invasions 2017, 19, 3613–3627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Nordh, H.; Swensen, G. Introduction to the special feature “The role of cemeteries as green urban spaces”. Urban For. Urban Green. 2018, 33, 56–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prach, K. Succession of Woody Species in Derelict Sites in Central-Europe. Ecol. Eng. 1994, 3, 49–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seitz, B.; Ristow, M.; Prasse, R.; Machatzki, B.; Klemm, G.; Böcker, R.; Sukopp, H. Der Berliner Florenatlas; Verhandlungen des Botanischen Vereins von Berlin und Brandenburg: Berlin, Germany, 2012; 533p. [Google Scholar]

- Cierjacks, A.; Kowarik, I.; Joshi, J.; Hempel, S.; Ristow, M.; von der Lippe, M.; Weber, E. Biological Flora of the British Isles: Robinia pseudoacacia. J. Ecol. 2013, 101, 1623–1640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vitková, M.; Muellerová, J.; Sádlo, J.; Pergl, J.; Pyšek, P. Black locust (Robinia pseudoacacia) beloved and despised: A story of an invasive tree in Central Europe. For. Ecol. Manag. 2017, 384, 287–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hilmers, T.; Friess, N.; Bassler, C.; Heurich, M.; Brandl, R.; Pretzsch, H.; Seidl, R.; Müller, J. Biodiversity along temperate forest succession. J. Appl. Ecol. 2018, 55, 2756–2766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Schirmel, J.; Bundschuh, M.; Entling, M.H.; Kowarik, I.; Buchholz, S. Impacts of invasive plants on resident animals across ecosystems, taxa, and feeding types: A global assessment. Glob. Chang. Biol. 2016, 22, 594–603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Seibold, S.; Cadotte, M.W.; MacIvor, J.S.; Thorn, S.; Müller, J. The Necessity of Multitrophic Approaches in Community Ecology. Trends Ecol. Evol. 2018, 33, 754–764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Senatsverwaltung für Stadtentwicklung und Wohnen. Umweltatlas Berlin. 05.08 Biotoptypen (Ausgabe 2014). Available online: https://www.stadtentwicklung.berlin.de/umwelt/umweltatlas/k508.htm (accessed on 13 August 2019).

- Kreyer, D.; Zerbe, S. Short-lived tree species and their role as indicators for plant diversity in the restoration of natural forests. Restor. Ecol. 2006, 14, 137–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sachse, U.; Starfinger, U.; Kowarik, I. Synanthropic woody species in the urban area of Berlin. In Urban Ecology: Plants and Plant Communities in Urban Environments; Sukopp, H., Hejny, S., Kowarik, I., Eds.; SPB Academic Publishing: The Hague, The Netherlands, 1990; pp. 233–243. [Google Scholar]

- Arbeitsgruppe Artenschutzprogramm Berlin, Grundlagen für das Artenschutzprogramm Berlin. Landsch. Umweltforsch. 1984, 23, 1–999.

- Lachmund, J. Greening Berlin: The Co-Production of Science, Politics, and Urban Nature; The MIT Press: Cambridge, MA, USA; London, UK, 2013; 320p. [Google Scholar]

- Kowarik, I. Urban wilderness: Supply, demand, and access. Urban For. Urban Green. 2018, 29, 336–347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kowarik, I. The “Green Belt Berlin”: Establishing a greenway where the Berlin Wall once stood by integrating ecological, social and cultural approaches. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2019, 184, 12–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bornkamm, R. Spontaneous development of urban woody vegetation on differing soils. Flora 2007, 202, 695–704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rebele, F. Differential succession towards woodland along a nutrient gradient. Appl. Veg. Sci. 2013, 16, 365–378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Platen, R.; Kowarik, I. Dynamik von Pflanzen-, Spinnen- und Laufkäfergemeinschaften bei der Sukzession von Trockenrasen zu Gehölzgesellschaften auf innerstädtischen Brachflächen in Berlin. Verh. d. Ges. f. Ökol. 1995, 24, 431–439. [Google Scholar]

- Buchholz, S.; Blick, T.; Hannig, K.; Kowarik, I.; Lemke, A.; Otte, V.; Scharon, J.; Schonhofer, A.; Teige, T.; von der Lippe, M.; et al. Biological richness of a large urban cemetery in Berlin. Results of a multi-taxon approach. Biodivers. Data J. 2016, 4, e7057. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Graf, A. Flora und Vegetation der Friedhöfe in Berlin (West). Verh. Berl. Bot. Ver. 1986, 5, 1–211. [Google Scholar]

- Sachse, U. Die anthropogene Ausbreitung von Berg- und Spitzahorn: (Acer pseudoplatanus L. und Acer platanoides L.): Ökologische Voraussetzungen am Beispiel Berlins. Landsch. Umweltforsch. 1989, 63, 1–132. [Google Scholar]

- Passarge, H. Ortsnahe Ahorn-Gehölze und Ahorn-Parkwaldgesellschaften. Tuexenia 1990, 10, 369–384. [Google Scholar]

- QGIS Development Team. QGIS Geographic Information System; Open Source Geospatial Foundation Project; QGIS Development Team: Zürich, Switzerland, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- McKinney, M. Effects of urbanization on species richness: A review of plants and animals. Urban Ecosyst. 2008, 11, 161–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niemela, J.; Kotze, D.J. Carabid beetle assemblages along urban to rural gradients: A review. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2009, 92, 65–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burkman, C.E.; Gardiner, M.M. Spider assemblages within greenspaces of a deindustrialized urban landscape. Urban Ecosyst. 2015, 18, 793–818. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buchholz, S.; Hannig, K.; Moller, M.; Schirmel, J. Reducing management intensity and isolation as promising tools to enhance ground-dwelling arthropod diversity in urban grasslands. Urban Ecosyst. 2018, 21, 1139–1149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vergnes, A.; Pellissier, V.; Lemperiere, G.; Rollard, C.; Clergeau, P. Urban densification causes the decline of ground-dwelling arthropods. Biodivers. Conserv. 2014, 23, 1859–1877. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hennekens, S.M.; Schaminee, J.H.J. TURBOVEG, a comprehensive data base management system for vegetation data. J. Veg. Sci. 2001, 12, 589–591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Müller-Motzfeld, G.; Freude, H.; Harde, K.W.; Lohse, G.A.; Klausnitzer, B. Die Käfer Mitteleuropas. Band 2 Adephaga 1: Carabidae (Laufkäfer); Spektrum Akademischer Verlag: München, Germany, 2004; 521p. [Google Scholar]

- Nentwig, W.; Blick, T.; Gloor, D.; Hänggi, A.; Kropf, C. Araneae. Spiders of Europe. Version 05.2015. Available online: https://www.araneae.nmbe.ch (accessed on 5 May 2015).

- Roberts, M.J. The Spiders of Great Britain and Ireland; Harley Books: Colchester, UK, 1987. [Google Scholar]

- Roberts, M.J. Spinnengids; Tirion: Baarn, The Netherlands, 1998; 397p. [Google Scholar]

- Kielhorn, K.H. Rote Liste und Gesamtartenliste der Laufkäfer (Coleoptera: Carabidae) von Berlin. In Rote Listen der gefährdeten Pflanzen und Tiere von Berlin; CD-ROM; Der Landesbeauftragte für Naturschutz und Landschaftspflege & Senatsverwaltung für Stadtentwicklung: Berlin, Germany, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Kielhorn, U. Rote Liste und Gesamtartenliste der Spinnen (Araneae) und Gesamtartenliste der Weberknechte (Opiliones) von Berlin. In Rote Listen der gefährdeten Pflanzen, Pilze und Tiere von Berlin; Der Landesbeauftragte für Naturschutz und Landschaftspflege & Senatsverwaltung für Umwelt, Verkehr und Klimaschutz: Berlin, Germany, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Seitz, B.; Ristow, M.; Meißner, J.; Machatzki, B.; Sukopp, H. Rote Liste und Gesamtartenliste der etablierten Farn- und Blütenpflanzen von Berlin. In Rote Listen der gefährdeten Pflanzen, Pilze und Tiere von Berlin; Der Landesbeauftrage für Naturschutz und Landschaftspflege & Senatsverwaltung für Umwelt, Verkehr und Klimaschutz: Berlin, Germany, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Londo, G. The decimal scale for releves of permanent quadrats. Vegetatio 1976, 33, 61–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braun-Blanquet, J. Pflanzensoziologie, Grundzüge der Vegetationskunde; Springer: Wien, Austria, 1964; 865p. [Google Scholar]

- R Core Team. R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing, version R-3.4.4; R Foundation for Statistical Computing: Vienna, Austria, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Hollander, M.; Wolfe, D.A. Nonparametric Statistical Methods; John Wiley & Sons: New York, NY, USA, 1973. [Google Scholar]

- Oksanen, J.; Blanchet, F.G.; Friendly, M.; Kindt, R.; Legendre, P.; McGlinn, D.; Minchin, P.R.; O’Hara, R.B.; Simpson, G.L.; Solymos, P.; et al. Vegan: Community Ecology Package. R Package Version 2.4-3. 2017. Available online: https://cran.r-project.org/src/contrib/Archive/vegan/ (accessed on 13 August 2019).

- Kattwinkel, M.; Biedermann, R.; Kleyer, M. Temporary conservation for urban biodiversity. Biol. Conserv. 2011, 144, 2335–2343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gardiner, M.M.; Burkman, C.E.; Prajzner, S.P. The Value of Urban Vacant Land to Support Arthropod Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services. Environ. Entomol. 2013, 42, 1123–1136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Křivánek, M.; Pyšek, P.; Jarošík, V. Planting history and propagule pressure as predictors of invasion by woody species in a temperate region. Conserv. Biol. 2006, 20, 1487–1498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Čeplová, N.; Lososová, Z.; Kalusová, V. Urban ornamental trees: A source of current invaders; a case study from a European City. Urban Ecosyst. 2017, 20, 1135–1140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kowarik, I. Zur Verbreitung, Vergesellschaftung und Einbürgerung des Götterbaumes (Ailanthus altissima [MiII.] Swingle) in Mitteleuropa. Tuexenia 1984, 4, 9–29. [Google Scholar]

- Kohler, A.; Sukopp, H. Über die Gehölzentwicklung auf Berliner Trümmerstandorten. Zugleich ein Beitrag zum Studium neophytischer Holzarten. Ber. Der Dtsch. Bot. Ges. 1964, 76, 389–407. [Google Scholar]

- Dyderski, M.K.; Jagodzinski, A.M. Functional traits of acquisitive invasive woody species differ from conservative invasive and native species. Neobiota 2019, 41, 91–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Honnay, O.; Endels, P.; Vereecken, H.; Hermy, M. The role of patch area and habitat diversity in explaining native plant species richness in disturbed suburban forest patches in northern Belgium. Divers. Distrib. 1999, 5, 129–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rastandeh, A.; Brown, D.K.; Pedersen Zari, M. Biodiversity conservation in urban environments: A review on the importance of spatial patterning of landscapes. In Proceedings of the Ecocity World Summit, Melbourne, Australia, 12–14 July 2017; pp. 12–14. [Google Scholar]

- Kowarik, I. Novel urban ecosystems, biodiversity, and conservation. Environ. Pollut. 2011, 159, 1974–1983. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schirmel, J.; Timler, L.; Buchholz, S. Impact of the invasive moss Campylopus introflexus on carabid beetles (Coleoptera: Carabidae) and spiders (Araneae) in acidic coastal dunes at the southern Baltic Sea. Biol. Invasions 2011, 13, 605–620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castro-Díez, P.; Gonzalez-Munoz, N.; Alonso, A.; Gallardo, A.; Poorter, L. Effects of exotic invasive trees on nitrogen cycling: A case study in Central Spain. Biol. Invasions 2009, 11, 1973–1986. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hejda, M.; Hanzelka, J.; Kadlec, T.; Štrobl, M.; Pyšek, P.; Reif, J. Impacts of an invasive tree across trophic levels: Species richness, community composition and resident species’ traits. Divers. Distrib. 2017, 23, 997–1007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reinhart, K.O.; Greene, E.; Callaway, R.M. Effects of Acer platanoides invasion on understory plant communities and tree regeneration in the northern Rocky Mountains. Ecography 2005, 28, 573–582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simberloff, D.; Von Holle, B. Positive interactions of nonindigenous species: Invasional meltdown? Biol. Invasions 1999, 1, 21–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Von Holle, B.; Joseph, K.A.; Largay, E.F.; Lohnes, R.G. Facilitations between the introduced nitrogen-fixing tree, Robinia pseudoacacia, and nonnative plant species in the glacial outwash upland ecosystem of cape cod, MA. Biodivers. Conserv. 2006, 15, 2197–2215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braga, R.R.; Gomez-Aparicio, L.; Heger, T.; Vitule, J.R.S.; Jeschke, J.M. Structuring evidence for invasional meltdown: Broad support but with biases and gaps. Biol. Invasions 2018, 20, 923–936. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Pyšek, P.; Jarošik, V.; Hulme, P.E.; Pergl, J.; Hejda, M.; Schaffner, U.; Vilà, M. A global assessment of invasive plant impacts on resident species, communities and ecosystems: The interaction of impact measures, invading species’ traits and environment. Glob. Chang. Biol. 2012, 18, 1725–1737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bartz, R.; Kowarik, I. Assessing the environmental impacts of invasive alien plants: A review of assessment approaches. Neobiota 2019, 43, 69–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Dyderski, M.K.; Jagodzinski, A.M. Drivers of invasive tree and shrub natural regeneration in temperate forests. Biol. Invasions 2018, 20, 2363–2379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Stohlgren, T.J.; Barnett, D.; Flather, C.; Fuller, P.; Peterjohn, B.; Kartesz, J.; Master, L.L. Species richness and patterns of invasion in plants, birds, and fishes in the United States. Biol. Invasions 2006, 8, 427–447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Stohlgren, T.J.; Barnett, D.T.; Kartesz, J. The rich get richer: Patterns of plant invasions in the United States. Front. Ecol. Environ. 2003, 1, 11–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fridley, J.D.; Stachowicz, J.J.; Naeem, S.; Sax, D.F.; Seabloom, E.W.; Smith, M.D.; Stohlgren, T.J.; Tilman, D.; Von Holle, B. The invasion paradox: Reconciling pattern and process in species invasions. Ecology 2007, 88, 3–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aronson, M.F.J.; La Sorte, F.A.; Nilon, C.H.; Katti, M.; Goddard, M.A.; Lepczyk, C.A.; Warren, P.S.; Williams, N.S.G.; Cilliers, S.; Clarkson, B.; et al. A global analysis of the impacts of urbanization on bird and plant diversity reveals key anthropogenic drivers. Proc. Biol. Sci. 2014, 281, 20133330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ramirez-Cruz, G.A.; Solano-Zavaleta, I.; Mendoza-Hernandez, P.E.; Mendez-Janovitz, M.; Suarez-Rodriguez, M.; Zuniga-Vega, J.J. This town ain’t big enough for both of us…or is it? Spatial co-occurrence between exotic and native species in an urban reserve. PLoS ONE 2019, 14, e0211050. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Matthews, E.R.; Schmit, J.P.; Campbell, J.P. Climbing vines and forest edges affect tree growth and mortality in temperate forests of the US Mid-Atlantic States. For. Ecol. Manag. 2016, 374, 166–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaertner, M.; Larson, B.M.H.; Irlich, U.M.; Holmes, P.M.; Stafford, L.; van Wilgen, B.W.; Richardson, D.M. Managing invasive species in cities: A framework from Cape Town, South Africa. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2016, 151, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Sádlo, J.; Vitková, M.; Pergl, J.; Pyšek, P. Towards site-specific management of invasive alien trees based on the assessment of their impacts: The case of Robinia pseudoacacia. Neobiota 2017, 35, 1–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Slabejová, D.; Bacigál, T.; Hegedüšová, K.; Májeková, J.; Medvecká, J.; Mikulová, K.; Šibíková, M.; Škodová, I.; Zaliberová, M.; Jarolímek, I. Comparison of the understory vegetation of native forests and adjacent Robinia pseudoacacia plantations in the Carpathian-Pannonian region. For. Ecol. Manag. 2019, 439, 28–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hanzelka, J.; Reif, J. Effects of vegetation structure on the diversity of breeding bird communities in forest stands of non-native black pine (Pinus nigra A.) and black locust (Robinia pseudoacacia L.) in the Czech Republic. For. Ecol. Manag. 2016, 379, 102–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morelli, F.; Benedetti, Y.; Su, T.P.; Zhou, B.; Moravec, D.; Šímová, P.; Liang, W. Taxonomic diversity, functional diversity and evolutionary uniqueness in bird communities of Beijing’s urban parks: Effects of land use and vegetation structure. Urban For. Urban Green. 2017, 23, 84–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Threlfall, C.G.; Mata, L.; Mackie, J.A.; Hahs, A.K.; Stork, N.E.; Williams, N.S.G.; Livesley, S.J. Increasing biodiversity in urban green spaces through simple vegetation interventions. J. Appl. Ecol. 2017, 54, 1874–1883. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Kowarik, I. Einführung und Ausbreitung nichteinheimischer Gehölzarten in Berlin und Brandenburg und ihre Folgen für Flora und Vegetation. Ein Modell für die Freisetzung gentechnisch veränderter Organismen; Verhandlungen des Botanischen Vereins von Berlin und Brandenburg: Berlin, Germany, 1992; 188p. [Google Scholar]

- Doroski, D.A.; Felson, A.J.; Bradford, M.A.; Ashton, M.P.; Oldfield, E.E.; Hallett, R.A.; Kuebbing, S.E. Factors driving natural regeneration beneath a planted urban forest. Urban For. Urban Green. 2018, 29, 238–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sukopp, H. Stadtökologie: Das Beispiel Berlin; D. Reimer: Berlin, Germany, 1990; 455p. [Google Scholar]

- Pickett, S.T.A.; Cadenasso, M.L.; Grove, J.M.; Nilon, C.H.; Pouyat, R.V.; Zipperer, W.C.; Costanza, R. Urban ecological systems: Linking terrestrial ecological, physical, and socioeconomic components of metropolitan areas. Annu. Rev. Ecol. Syst. 2001, 32, 127–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Boring, L.R.; Swank, W.T. The Role of Black Locust (Robinia pseudoacacia) in Forest Succession. J. Ecol. 1984, 72, 749–766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Kowarik, I. Functions of clonal growth of trees in the wasteland-succession with special attention of Robinia pseudoacacia. Verh. d. Ges. f. Ökol. 1996, 26, 173–181. [Google Scholar]

- Hobbs, R.J.; Higgs, E.S.; Hall, C. Novel Ecosystems: Intervening in the New Ecological World Order; Wiley-Blackwell: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2013; 380p. [Google Scholar]

- Lugo, A.E. Novel tropical forests: Nature’s response to global change. Trop. Conserv. Sci. 2013, 6, 325–337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shwartz, A.; Turbe, A.; Julliard, R.; Simon, L.; Prevot, A.C. Outstanding challenges for urban conservation research and action. Glob. Environ. Chang. 2014, 28, 39–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ives, C.D.; Lentini, P.E.; Threlfall, C.G.; Ikin, K.; Shanahan, D.F.; Garrard, G.E.; Bekessy, S.A.; Fuller, R.A.; Mumaw, L.; Rayner, L.; et al. Cities are hotspots for threatened species. Glob. Ecol. Biogeogr. 2016, 25, 117–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Planchuelo, G.; von der Lippe, M.; Kowarik, I. Untangling the role of urban ecosystems as habitats for endangered plant species. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2019, 189, 320–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jarošík, V.; Konvička, M.; Pyšek, P.; Kadlec, T.; Beneš, J. Conservation in a city: Do the same principles apply to different taxa? Biol. Conserv. 2011, 144, 490–499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jacquemyn, H.; Butaye, J.; Hermy, M. Forest plant species richness in small, fragmented mixed deciduous forest patches: The role of area, time and dispersal limitation. J. Biogeogr. 2001, 28, 801–812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verheyen, K.; Hermy, M. The relative importance of dispersal limitation of vascular plants in secondary forest succession in Muizen Forest, Belgium. J. Ecol. 2001, 89, 829–840. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Possingham, H.P.; Andelman, S.J.; Burgman, M.A.; Medellin, R.A.; Master, L.L.; Keith, D.A. Limits to the use of threatened species lists. Trends Ecol. Evol. 2002, 17, 503–507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Dearborn, D.C.; Kark, S. Motivations for Conserving Urban Biodiversity. Conserv. Biol. 2010, 24, 432–440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- James, P.; Tzoulas, K.; Adams, M.D.; Barber, A.; Box, J.; Breuste, J.; Elmqvist, T.; Frith, M.; Gordon, C.; Greening, K.L.; et al. Towards an integrated understanding of green space in the European built environment. Urban For. Urban Green. 2009, 8, 65–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lepczyk, C.A.; Aronson, M.F.J.; Evans, K.L.; Goddard, M.A.; Lerman, S.B.; Macivor, J.S. Biodiversity in the City: Fundamental Questions for Understanding the Ecology of Urban Green Spaces for Biodiversity Conservation. Bioscience 2017, 67, 799–807. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Pauleit, S.; Ambrose-Oji, B.; Andersson, E.; Anton, B.; Buijs, A.; Haase, D.; Elands, B.; Hansen, R.; Kowarik, I.; Kronenberg, J.; et al. Advancing urban green infrastructure in Europe: Outcomes and reflections from the GREEN SURGE project. Urban For. Urban Green. 2019, 40, 4–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buchholz, S.; Kowarik, I. Urbanisation modulates plant-pollinator interactions in invasive vs. native plant species. Sci. Rep. 2019, 9, 6375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grimm, N.B.; Faeth, S.H.; Golubiewski, N.E.; Redman, C.L.; Wu, J.G.; Bai, X.M.; Briggs, J.M. Global change and the ecology of cities. Science 2008, 319, 756–760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Heger, T.; Bernard-Verdier, M.; Gessler, A.; Greenwood, A.D.; Grossart, H.-P.; Hilker, M.; Keinath, S.; Kowarik, I.; Kueffer, C.; Marquard, E.; et al. Towards an Integrative, Eco-Evolutionary Understanding of Ecological Novelty: Studying and Communicating Interlinked Effects of Global Change. Bioscience 2019, 69, 888–899. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soga, M.; Gaston, K.J. Extinction of experience: The loss of human-nature interactions. Front. Ecol. Environ. 2016, 14, 94–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Soga, M.; Gaston, K.J.; Yamaura, Y.; Kurisu, K.; Hanaki, K. Both Direct and Vicarious Experiences of Nature Affect Children’s Willingness to Conserve Biodiversity. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2016, 13, 529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Miller, J.R.; Hobbs, R.J. Conservation where people live and work. Conserv. Biol. 2002, 16, 330–337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwarz, N.; Moretti, M.; Bugalho, M.N.; Davies, Z.G.; Haase, D.; Hack, J.; Hof, A.; Melero, Y.; Pett, T.J.; Knapp, S. Understanding biodiversity-ecosystem service relationships in urban areas: A comprehensive literature review. Ecosyst. Serv. 2017, 27, 161–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Rupprecht, C.D.D.; Byrne, J.A. Informal urban greenspace: A typology and trilingual systematic review of its role for urban residents and trends in the literature. Urban For. Urban Green. 2014, 13, 597–611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Rupprecht, C.D.D.; Byrne, J.A.; Ueda, H.; Lo, A.Y. ’It’s real, not fake like a park’: Residents’ perception and use of informal urban green-space in Brisbane, Australia and Sapporo, Japan. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2015, 143, 205–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Threlfall, C.G.; Kendal, D. The distinct ecological and social roles that wild spaces play in urban ecosystems. Urban For. Urban Green. 2018, 29, 348–356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riley, C.B.; Perry, K.I.; Ard, K.; Gardiner, M.M. Asset or Liability? Ecological and Sociological Tradeoffs of Urban Spontaneous Vegetation on Vacant Land in Shrinking Cities. Sustainability 2018, 10, 2139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Brun, M.; Di Pietro, F.; Bonthoux, S. Residents’ perceptions and valuations of urban wastelands are influenced by vegetation structure. Urban For. Urban Green. 2018, 29, 393–403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mathey, J.; Arndt, T.; Banse, J.; Rink, D. Public perception of spontaneous vegetation on brownfields in urban areas-Results from surveys in Dresden and Leipzig (Germany). Urban For. Urban Green. 2018, 29, 384–392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maruthaveeran, S.; Konijnendijk van den Bosch, C.C. A socio-ecological exploration of fear of crime in urban green spaces—A systematic review. Urban For. Urban Green. 2014, 13, 1–18. [Google Scholar]

- Nassauer, J.I. Messy Ecosystems, Orderly Frames. Landsc. J. 1995, 14, 161–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Kühn, N. Intentions for the Unintentional: Spontaneous Vegetation as the Basis for Innovative Planting Design in Urban Areas. J. Landsc. Arch. 2006, 1, 46–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Del Tredici, P. Spontaneous Urban Vegetation: Reflections of Change in a Globalized World. Nat. Cult. 2010, 5, 299–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hwang, Y.H.; Yue, Z.E.J. Intended wildness: Utilizing spontaneous growth for biodiverse green spaces in a tropical city. J. Landsc. Arch. 2019, 14, 54–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Del Tredici, P.; Rueb, T. Other order: Sound walk for an urban wild. Arnoldia 2017, 75, 14–25. [Google Scholar]

| Acer Forests | Betula and Robinia Forests | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Vascular Plants | |||

| Study area | Weißensee Jewish cemetery | 10 Christian cemeteries | Successional forests across Berlin |

| Data source | [62,109] | This study | [49] |

| Number of plots | 21 | 30 | Paired plots, 34 dominated by Betula pendula, 34 dominated by Robinia pseudacacia (68 in total) |

| Plot size | 10 m × 10 m | 10 m × 10 m | 10 m × 10 m |

| Plot selection | Random selection with Hawth’s Analysis Tools for ArcGis | Random selection with Hawth’s Analysis Tools for ArcGis and Random Points tool in QGIS | Random selection |

| Recording time | April–May 2013 | April–May 2013; May–June 2015 | May–July 2010 |

| Abundance estimation method | [127] transformation of values into percentages for statistical analyses | [127] transformation of values into percentages for statistical analyses | [128] transformation of values into percentages for statistical analyses |

| Invertebrates | |||

| Study area | Weißensee Jewish cemetery | Successional forests across Berlin | |

| Data source | [62,109] | [87] | |

| Number of plots | 21 | 20 | |

| Recording time | 24 April–25 June 2013 | 1 May–30 June 2012 | |

| Dominant Trees | Patch Number | Average Patch Size (ha) | Total Area (ha) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Native species | |||

| Betula pendula | 64 (12.4%) | 0.4536 | 29.0 (8.6%) |

| Populus tremula | 20 (3.9%) | 0.2778 | 5.6 (1.7%) |

| Total native | 84 (16.3%) | 0.4118 | 34.6 (10.3%) |

| Alien species | |||

| Robinia pseudoacacia | 173 (33.5%) | 0.5842 | 101.1 (29.9%) |

| Populus × canadensis | 30 (5.8%) | 0.3656 | 11.0 (3.3%) |

| Total alien | 203 (39.3%) | 0.5518 | 112.0 (33.2%) |

| Undefined | |||

| Acer spp. | 78 (15.1%) | 0.6229 | 48.6 (14.4%) |

| Other species | 151 (29.3%) | 0.9430 | 142.4 (42.2%) |

| Total undefined | 229 (44.4%) | 0.8340 | 191.0 (56.6%) |

| Total | 516 (100%) | 0.6543 | 337.6 (100%) |

© 2019 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Kowarik, I.; Hiller, A.; Planchuelo, G.; Seitz, B.; von der Lippe, M.; Buchholz, S. Emerging Urban Forests: Opportunities for Promoting the Wild Side of the Urban Green Infrastructure. Sustainability 2019, 11, 6318. https://doi.org/10.3390/su11226318

Kowarik I, Hiller A, Planchuelo G, Seitz B, von der Lippe M, Buchholz S. Emerging Urban Forests: Opportunities for Promoting the Wild Side of the Urban Green Infrastructure. Sustainability. 2019; 11(22):6318. https://doi.org/10.3390/su11226318

Chicago/Turabian StyleKowarik, Ingo, Anne Hiller, Greg Planchuelo, Birgit Seitz, Moritz von der Lippe, and Sascha Buchholz. 2019. "Emerging Urban Forests: Opportunities for Promoting the Wild Side of the Urban Green Infrastructure" Sustainability 11, no. 22: 6318. https://doi.org/10.3390/su11226318

APA StyleKowarik, I., Hiller, A., Planchuelo, G., Seitz, B., von der Lippe, M., & Buchholz, S. (2019). Emerging Urban Forests: Opportunities for Promoting the Wild Side of the Urban Green Infrastructure. Sustainability, 11(22), 6318. https://doi.org/10.3390/su11226318