Abstract

Agricultural mechanization in developing countries has taken at least two contested innovation pathways—the “incumbent trajectory” that promotes industrial agriculture, and an “alternative pathway” that supports small-scale mechanization for sustainable development of hillside farming systems. Although both pathways can potentially reduce human and animal drudgery, the body of literature that assesses the sustainability impacts of these mechanization pathways in the local ecological, socio-economic, cultural, and historical contexts of hillside farms is either nonexistent or under-theorized. This paper addresses this missing literature by examining the case of Nepal’s first Agricultural Mechanization Promotion Policy 2014 (AMPP) using a conceptual framework of what will be defined as “responsible innovation”. The historical context of this assessment involves the incumbent trajectory of mechanization in the country since the late 1960s that neglected smallholder farms located in the hills and mountains and biased mechanization policy for flat areas only. Findings from this study suggest that the AMPP addressed issues for smallholder production, including gender inequality, exclusion of smallholder farmers, and biophysical challenges associated with hillside farming systems, but it remains unclear whether and how the policy promotes small-scale agricultural mechanization for sustainable development of agriculture in the hills and mountains of Nepal.

1. Introduction

When the rest of the world is talking about farming based on automated and precision-type technologies, hillside farming in many low-income countries is characterized by immense human and animal drudgery [1,2]. Since the pre-industrial age when hand tools or basic machines were used for manufacturing, the Industrial Revolution of the eighteenth century marked the introduction of power-operated, special-purpose machinery, factories, and mass production. Farm mechanization in many industrialized countries, such as the UK, USA, and Canada, witnessed the rapid development and use of power-operated machines [3]. Colonial empires of the nineteenth century brought some of these technologies to the less developed areas of the world, with mixed results and significant social and environmental impacts. The Green Revolution of the twentieth century typically emphasized monocultures of improved crop varieties requiring the use of heavy equipment, such as tractors, trucks, water pumps, reapers, threshers, and combine harvesters [4]. By design, these machines were biased towards larger parcels of flatlands that had higher potential crop yield [5]. As a result, smallholder hillside farms in many developing countries still suffer today from a lack of socially and environmentally responsible mechanization, a recognized limitation of the “transfer of technology” paradigm of agricultural development [6]. Rose and Chilvers [7] further argued that most nations such as UK, Australia, India, and Japan are investing on smart farming approaches and developing smart technologies such as drones, robots, and artificial intelligence. It is expected that agri-tech revolutions will occur worldwide which will bring a rapid transformation in agriculture; thus Rose and Chilvers [7] described it as the era of the fourth agriculture revolution or Agriculture 4.0 [8]. Smart technologies are also being promoted as an integral part of Sustainable Intensification (SI) of agriculture even though SI aims to increase the agricultural productivity with less environmental damage and more social benefits [9]. The SI approach is widely promoted in south Asia and Sub-Saharan Africa with the aim to support smallholder family farms [10,11], however it also encourages the use of advanced technologies and in larger areas. Before such new technologies are considered, however, policymakers in countries, such as Nepal where hillside agriculture is widely practiced, should address the flatland bias of past and current technology transfer regimes and seek non-incumbent strategies for responsible innovation involving agricultural mechanization that supports the sustainable development of hillside farming systems.

In general, at least two pathways of farm mechanization related innovation have been observed in developing countries—the incumbent mechanization, represented by the use of large machines suitable for flatlands, and alternative mechanization, represented by smaller machines, locally or household-owned animal traction, and hand tools suitable for reducing drudgery on hillside farms [12]. Although there has been a recent surge in the body of literature on agricultural innovation systems in response to limitations of the transfer of technology paradigm of agricultural innovation, very few of them assess agricultural mechanization-related innovation [13,14]. Eastwood et al. [15] summarized that most applications of responsible innovation studies were done in the Europe and North America and still very limited study is available in agriculture innovation, particularly in developing area contexts. Recognizing this gap, this article aims to critically discuss the incumbent technological trajectory and alternative pathways of agricultural mechanization innovation in Nepal, a nation with abundant hillside farms, using the conceptual framework of “responsible innovation” [16]. Stilgoe et al. [16] (p. 1570) defines responsible innovation as “…taking care of the future through collective stewardship of science and innovation in the present”. This paper assesses the Agricultural Mechanization Promotion Policy (AMPP) in Nepal, established and implemented since 2014, along two dimensions: first, anticipation and inclusion in policy processes; and second, reflexivity and responsiveness of AMPP to the needs of hillside farms and farmers. The main research question of this paper attempts to answer is whether Nepal’s farm mechanization policy is suitable from social (gender and age) and environmental (soil conservation, slope/terrace cultivation, and agricultural biodiversity) perspectives.

The part of the above question is addressed in Section 2 of this paper through the reviews of the available literature which contributes to the development of a conceptual framework of responsible innovation that will be tested using the empirical findings from Nepal’s farm mechanization policy and practice. Section 3 outlines the research methods employed in this study and also discuss some methodological limitations. Then, Section 4 presents a case study of Nepal’s Agricultural Mechanization Promotion Policy 2014 within the historical and agrarian contexts of agricultural innovation. Section 5 discusses the case study findings using the responsible innovation framework. The final section summarizes key findings of the paper and provides a set of policy recommendations for “responsible mechanization innovation” of Nepalese hillside farms which may also be relevant for sustainable development of hillside farming systems in other parts of Asia and the developing world.

2. Literature Review and Conceptual Framework

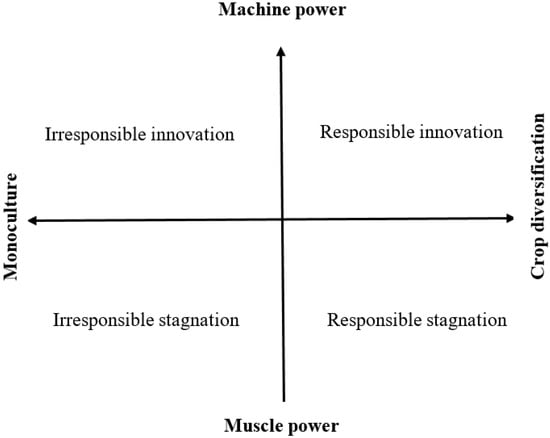

Transfer of new and emerging technologies from developed nations or regions to developing areas of the world may not always be a responsible endeavor when mechanization disadvantages certain types of farms or agricultural zones such as Nepal’s hilly regions [17]. Hence, as suggested by Guston [18], there are two axes of responsible innovation: the first axis moves from stagnation to innovation; and the second axis shifts from irresponsibility to responsibility. This two by two matrix generates four possible scenarios: irresponsible stagnation, irresponsible innovation, responsible stagnation, and responsible innovation. While irresponsible stagnation is not acceptable for a progressive society, responsible stagnation would be preferred over irresponsible innovation that would place society at risk. Societal risk can be reduced through different framing of innovation policy—innovation for economic growth, innovation as a system of stakeholder relations and functions, such as national innovation systems, regional innovation systems or sectoral innovation systems, and innovation as a transformational change of unjust social structures and processes [19]. Hence, responsible innovation should be about innovating responsibly, or not innovating at all, to avoid an irresponsible innovation trajectory, such as an attempt to introduce larger machines in hillside farming [20]. Schot and Steinmueller [19] argue that if innovation policy can recognize and address the four major failures of “directionality, policy coordination, demand-articulation and reflexivity” (p. 1562), then innovation can bring transformative changes in society. As it applies to farm mechanization innovation, a responsible stagnation would be preferred over irresponsible innovation that not only excludes smallholder hillside farmers especially women and the older generation but also leads to soil degradation, damage in terrace/slope, disruption of the biogeochemical cycle, and agricultural biodiversity loss in intensively cultivated areas, which did occur with the transfer of technology during the Green Revolution [21].

Even though there are several conceptualizations of responsible innovation [15], four dimensions of responsible innovation—anticipation, inclusion, reflexivity, and responsiveness—also known as the AIRR framework, is more common to guide technology development [15,22,23]. For the analysis of farm mechanization innovation, Stilgoe et al.’s [16] four dimensions of responsible innovation can be discussed along two lines of reasoning: anticipation and inclusion in policy processes, and reflexivity and responsiveness on policy impacts (see Table 1 for a list of engagement methods; although, a comprehensive discussion of them is beyond the scope of this paper). The first line of reasoning, anticipation and inclusion, concerns public engagement in science and technology. Anticipation methods, such as foresight and visioning, involve building scenarios and imagining the future [15,24]. Public engagement in responsible innovation and science policy requires the participation of a broader range of stakeholders, including engineers, natural scientists, social scientists, policymakers, development practitioners, entrepreneurs, and end-users [19,25].

Table 1.

Dimensions of responsible innovation.

The second line of reasoning, reflexivity and responsiveness, is about interactive learning and innovation across space, place, scale, and time. Reflexivity involves negotiating moral boundaries and the roles of various stakeholders, seeking self-critique of our own beliefs, values, and established mindset [26]. The existing body of literature on farm mechanization innovation identifies at least four areas of reflexivity on the dominant worldview of agricultural mechanization: forgotten inquiry associated with farm mechanization as a result of a preoccupation with seed technology rather than seed systems; a flatland bias of large-scale mechanization, that has led to an irresponsible stagnation of hillside mechanization; and social and environmental impacts of various mechanization pathways [27,28]. For example, based on their research in eastern and southern Africa, Baudron et al. [13] argued that farm power and machinery are often forgotten or taken for granted in the culture of innovation that focuses on land, water, crop variety, and fertilizer use to enhance agricultural productivity. This implicated the second area of reflexivity that identifies the suboptimal trajectory of farm mechanization innovations that focus on big machines, such as four-wheeled tractors (4WTs) and combine harvesters [28]. This is the incumbent trajectory that ignores or assumes that hills and mountains are not suitable for mechanized farming and geographically disadvantaged farmers, let alone women, poor, and minorities; neither have they deserved mechanization to reduce their own drudgery nor the drudgery of farm animals [29]. Third, mechanization is also often portrayed as drivers of land consolidation, business mergers, more intensive cropping, and labor displacement that may have high social and environmental costs [12]. There is often little promotion of smaller machines, such as two-wheel tractors (2WTs) and power tools suitable for areas that experienced severe labor shortages can have positive social impacts [27]. Neglecting mechanization of hillside farms on these grounds could result in irresponsible stagnation.

Fourth, the mainstream worldview of farm mechanization is often critiqued as damaging to the environment, such as soil degradation and biodiversity loss through intensive monoculture [8]. Depending on local biophysical, ecological, social, economic, and cultural contexts, various alternative pathways of farm mechanization innovation could serve as a deliberate response to these areas of reflexivity [30]. For example, in Bangladesh, over 80% of cultivation involves the promotion of smaller machines compared to 40% and 20% in India and Nepal, respectively. The Bangladeshi experience demonstrates a successful alternative agricultural mechanization pathway through the participatory farmer adoption of new scale-appropriate machinery, such as tillers, planters, and crop reapers that can be operated using two-wheel tractors (2WTs) [14,28]. To determine responsible innovation pathways, reflexive interactive assessment methods should be developed in tune with the core values and principles of participatory action research [31]. In this process, stakeholders who believe in inclusive, small-scale mechanization innovations should be responsive for reflecting on past assumptions and unfolding scenarios that may or may not have been anticipated previously in foresight and visioning exercises [19].

3. Research Methods

This research represents an examination of over 80 years of agricultural mechanization trends in Nepal and evaluates the most recent policy initiatives. As employed by Hekkert et al. [32] and Eastwood et al. [15], this paper involves a timeline analysis of technological change, but a critical point of departure is to focus on an assessment of responsible mechanization innovation for Nepal’s hillside farming systems. The rationale behind the focus on hillside mechanized farming in this study lies in the fact that this study was conducted in the context of the project, “Innovations for Terrace Farmers in Nepal and Testing of Private Sector Scaling Up Using Sustainable Agriculture Kits (SAKs)” and “Stall-Based Franchises (SAK Nepal project in short)”, funded by the Canadian International Development Research Centre (IDRC) and Global Affairs Canada (GAC). This SAK Nepal project has introduced, tested, and scaled up to commercial outlets the availability of sustainable, low-cost agricultural technologies in Nepal, including simple and low-cost tools and machines, that are available elsewhere around the world [33].

The empirical content presented in this paper is based on three phases of data collection. In the first phase, a timeline review of the history and current status of farm mechanization has been conducted through the assessment of major agricultural policy documents such as the Agricultural Development Strategy (ADS), Nepal Agricultural Research Centre (NARC) Vision, and the AMPP of Nepal. The 2014 AMPP document was available in local (Nepalese) language during this study. Authors translated the key points in English which are presented below in the results section of this paper for its detailed analysis. Other policy documents were in English and available online. Some of the authors of this paper directly worked as policy experts and researchers in Nepal for several years, which provides easy access to the key policy makers and planners from the Ministry of Agricultural Development (MoAD) (currently renamed as the Ministry of Agriculture and Livestock Development, MoALD). Key informant interviews with three national-level policy makers were done to discuss the essence of the major agricultural policies and their implementation. The time involved for each interview was about 1 to 1.5 h.

In the second stage, data were collected from hillside farmers who adopted farm machines and hand tools promoted by the project along with local policy makers and extension workers. We conducted four focus group discussions (FGDs) with farmers, two in Majhthana Village of Kaski District and two in Jogimara Village of Dhading District. These are the above-mentioned SAK Nepal project’s working sites. Altogether 55 farmers, 31 women and 24 men, participated in a discussion on why and how small machines and hand tools enable women and elderly farmers to reduce their workload and drudgery in daily farming activities while increasing the productivity of agriculture in long run. For each group discussion, 2 to 2.5 h were taken. The authors ran the discussions and hired an enumerator to take notes. Local project staffs assisted in the recruitment of the respondents for the FGDs.

In the third stage, key informant interviews were done at the local level in order to understand the ongoing mechanization program and its associated challenges. We chose Kaski District (one of the SAK Nepal project sites) as a case study for this process. Altogether, we conducted seven key informant interviews, one interview with the owner of a customs hiring center, which is the only service provider in the Kaski District, two with local government officers, two interviews with policy-makers at the regional level, and two interviews with officers of the Prime Minister’s Agricultural Modernization Project (PM-AMP) that oversees the implementation of the 2014 AMPP and coordinates the major publicly-funded agricultural mechanization initiatives in Nepal. Prime Minister’s Agriculture Modernization Project (PM-AMP) was launched in 2016, with the objective of specialized production. The four categories of programs were initiated based on the specific products area. The pocket and blocks consisted of 10 and 100 ha of area, respectively, and zone and super-zone were declared for areas of 500 and 1000 ha, respectively. Twenty-seven points of commitment by the Minister at that time, laid the foundation for development of the PM-AMP project [34]. The authors led all the interviews and focus group discussions.

A methodological limitation, however, is that the current analysis of agricultural mechanization policy is based on an ex-post assessment of the farm mechanization policy as many authors of this paper remained as external observers to how this policy unfolded. Nepal has also faced volatility in the agricultural sector in response to lack of labor due to the outmigration of rural youth and men leading to labor shortages and what is referred to as the “feminization” of the division of labor in agriculture [35]. Ideally, social science researchers could be involved in participatory action research during the policy process (agenda setting, policy formulation, decision making, policy implementation, and policy review) [36], but that was not the case in this study of farm mechanization innovation. Although this may appear like a lost opportunity for participatory action researchers, it forced the authors to be as objective as possible in the ex-post assessment of the mechanization policy. When it comes to implementation of this policy, many authors were engaged in testing of farm machines in selected areas of hillside farming systems, specifically in the SAK Nepal project villages.

4. Case Study: Agricultural Mechanization Promotion Policy Review in the Context of Rural Mechanization in Nepal

4.1. History of Agricultural Innovation and Science Policy

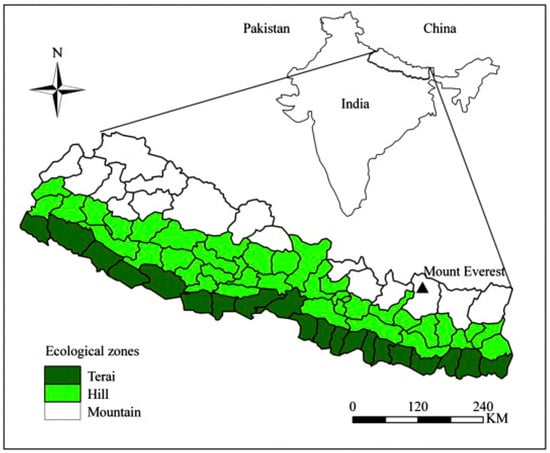

Topographically, Nepal is often divided into three major regions (Figure 1): the high Himalayas/mountains (24% of the country’s total area); the hills (56%); and the plains called the Terai (20%) [37]. Nepal’s modern agriculture started in 1937 with the establishment of the Agricultural Development Board with the aim of promoting growth from agriculture. An Agricultural Council was established to improve existing farming techniques, promote irrigation, and execute plans essential for the expansion of agricultural development in a country with a growing population [38]. In 1952, a new Agricultural Plan was developed to deliver information on new and important agricultural inputs, such as chemical fertilizers, improved seeds, and farm tools. A systematic five-year planning cycle for national agriculture development started in 1956 [5]. Prior to the 1950s, the Terai flatlands were prone to malaria. Perhaps, as a result, most settlements were in high-altitude regions, and farmers cultivated the lowlands for only a few months of the year during the summer months [39]. The Government of Nepal initiated the Malaria Eradication Program in 1956 (the first five-year plan, 1956–1961) and its eradication created an enabling environment for internal migration to the Terai, which led to an expansion of agricultural land and reduction in forest area [40]. Between 1973 and 1974, the Government of Nepal introduced a price subsidy for chemical fertilizers to encourage their use in spite of the rise in fertilizer prices in the international market. Until today, Nepal did not have its own fertilizer production and hence depended on imports. As a result, chemical fertilizer inputs increased on an ongoing basis, particularly in the Terai and flood plains [38].

Figure 1.

Country map showing three ecological zones of Nepal. Source: Local Initiatives for Biodiversity, Research, and Development (LI-BIRD).

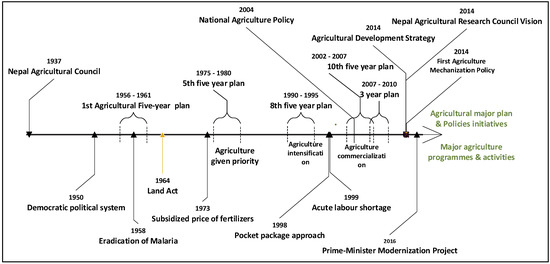

Agricultural intensification was given a priority in the eighth Five Year Plan (1992–1997) of the National Planning Commission of Nepal, with the aim of increasing per capita food production from 277 to 426 kg by 2017. On the whole, there was an increase in the production of all major cereal grains (rice, maize, and wheat) during the period from 1969 to 1993. However, it was revealed that this increase occurred solely as a result of the expansion of cultivated areas, and not because of technology improvement and crop intensification [41]. The amount of rural household labor in the late 1990s decreased significantly due to a higher rate of seasonal out-migration of males for employment in urban areas and abroad, and partly due to the decade-long Maoist insurgency (1996 to 2006) in the country which led to insecurity across the rural areas [42]. Table 2 and Figure 2 summarize the major episodes of agricultural development policy in Nepal.

Table 2.

History of agricultural development policy in Nepal.

Figure 2.

Timeline of major agricultural research and developments initiatives in Nepal, drawn by using Visio Pro 16.

The Ministry of Agricultural Development designed a “pocket package approach” in 1998 to implement the Prioritized Productivity Package (PPP) of the Agriculture Perspective Plan (APP, 1995–2015) [43]. For the hills and mountains, the APP strategically focuses on high-value, low-volume commodities which use less land, require minimum land preparation, and are easier to transport to the market. In contrast, in the Terai region, the strategy has been the promotion of modern technology for crop intensification (e.g., improved seed, fertilizer, pesticides, and machines) and the development of groundwater for irrigation [38]. However, mechanization for on-site processing of high-value crops was not prioritized in the PPP-APP. Typically Nepal’s agricultural and rural policies are neutral with respect to agricultural mechanization [29] as the public sector was preoccupied with modern industrial agriculture in the Terai plains [12]. In other words, Nepal’s past public policies on agricultural and rural development ignored mechanization in hillside farming systems because of a fear of labor displacement by the use of machines that could lead to large rural unemployment [47]. In hindsight, this was a clear failure to anticipate growing farm labor shortages, drudgery, and growing rural employment in the service sector, as well as opportunities for agri-food processing, marketing, and the influence of the growing remittance of the economy and labor [38,44,48,49].

Analysis of the major agricultural plans, including the (APP), indicates little detailed policy statements on agricultural mechanization. Gauchan and Shrestha [38] argue that past policies, such as the Land Act (1964) and National Civil Code (1962), have led to land fragmentation with the provision of land inheritance and a land ceiling, resulting in disincentives for large-scale agricultural mechanization. Despite this fact, mechanization was often misunderstood in the past as the use of large 4WTs rather than encompassing whole sets of manually operated semi-automated or animal-traction equipment and smaller machines (e.g., 2WTs, pump sets, etc.) [12].

After 2005, there have been some new developments with respect to the agricultural policy as prioritizing agricultural intensification and commercialization ultimately created a demand for machinery [45]. With the termination of the APP (1995–2015), the strategic plan known as the Agriculture Development Strategy (ADS 2015–2035) was developed in 2014 [46]. At the same time, National Agricultural Research Council (NARC) also formulated a strategic vision for national agricultural research in Nepal (NARC vision 2011–2035), which clearly highlighted the need to promote farm machinery in the country [5]. The AMPP was also developed in 2014 to address growing rural labor scarcity and increase agricultural productivity. From 2016 onwards, the Nepal government initiated a decade-long Prime Minister’s Agricultural Modernization Project (PM-AMP 2016–2025) with a stronger focus on agricultural mechanization [46].

4.2. History of Agricultural Mechanization Innovation in Nepal

Despite a long history of agricultural mechanization in Nepal, its pace has been slow [44]. Only approximately 15% to 20% of tillage is now mechanized in the country [38]. In the 1960s, 4WTs were introduced under donor supported projects [50] and since the 1970s onwards, 4WTs have been promoted as modern, commercial and efficient farm machinery [12]. In the mid-1970s and early 1980s, two Japanese aid programs donated Japanese and Korean power tillers to Nepal in large numbers [51]. Due to the high initial capital cost of buying the equipment and procuring expensive spare parts, subsidized Japanese and Korean power tillers did not achieve success. In Nepal, the power tillers that were intended for agricultural work were actually used for haulage and transportation, where they earned higher returns. Less expensive Chinese models became common in Nepal [12] once the government subsidies for tractors and machines were discouraged by the Asian Development Bank (ADB) Nepal during 1980–1985 [1].

Although small Chinese engines were cheaper and easy to use, Indian 4WTs ultimately achieved dominance in Nepal’s southern plains. Low-level tariffs were also in place for imports of Chinese machines, but this result may be due to closer ties and open borders between Nepal and India [51]. In 2012, around 42,000 tractors were found in the country, including 30,000 4WTS (71%) and 12,000 (29%) 2WTs [47]. Since the late 1990s, there have been some donor-funded small projects promoting 2WTs on a non-subsidized basis. This has led to an increase in the number of 2WTs. At the same time, 4WT sales were slowing due to direct competition from 2WTs [29]. Donor-supported programs for subsidized pump-sets and shallow tube wells were also introduced in the late 1970s and continued through the 1990s until the 2000s [12,44]. In recent years, the number of small-scale electrically powered engines for pump-sets has been few but increasing [16].

Due to the slow pace of agricultural mechanization in Nepal, animals (41%) and humans (36%) are still the major sources of farm power. About 92% of the total available mechanical power in the county is concentrated in the Terai flat region [38]. In the hills and mountains, around 8% of the farms are using mechanized tillage, whereas the rate in Terai flatlands is 46% [44]. Locally designed wooden and iron tools, such as local hoes, wooden ploughs, and sickles are more common in the hills and mountains [52]. Limited infrastructure like road networks and electricity are other key limitations that have slowed the growth of responsible mechanization innovation in hilly areas [5,28].

Although some small-scale threshers and pump sets were seen in a few hilly areas, mechanization in hillside farming systems was visible only after 2010, when small 5–9 horsepower hand tractors (2WTs, also called mini tillers) were introduced from China [17]. The United States Agency for International Development (USADI)-funded project, entitled Cereal Systems Initiative for South Asia (CSISA) [53] reported that there are more than 10,000 mini tillers used in the mid-hills of Nepal. The increase in mini tillers was due to subsidies in mini tillers under the AMPP 2014 and support for mini tillers from the immediate response to the death of over 17,000 animals, primarily draft animals, in the 2015 Nepal earthquake [38,44].

4.3. Agricultural Mechanization Promotion Policy of 2014 (AMPP 2014)

In this section, for analytical purposes, we decode the policy process into cyclical stages—from agenda-setting to policy formulation, policy decision, policy implementation, and policy evaluation/feedback—although in practice a smooth cyclical process is atypical and progress towards policy goals and objectives is usually more complex [36]. Cairney [54] further argues that the linear policy cycle or stage-based policy-making is an old concept and policymakers prefer modern theories which suggest more complicated graphs and processes in order to describe the complexity of policymaking; but it has difficult to understand and even difficult to deliver the messages. Thus, the simple linear policy making model is still popular and even more so among non-specialists as it is simple, easy to understand, and gives a distinct message on how to implement the policy process [36,54].

4.3.1. Agenda Setting

Two-thirds of the Nepalese population practice agriculture, which is mostly subsistence in nature, and it contributes about one-third of the country’s national gross domestic product [55]. Agriculture is the prime source of income and employment for people and provides partial and full-time employment opportunities to 74% of its population, most of whom live in smaller towns, villages, and rural areas [56]. The average landholding per family across Nepal is found to be less than 0.8 ha with 47% of landholdings being less than 0.5 ha in size [57]. Agricultural growth for the past two decades has hovered around a meager average of 3% to 3.2% [58]. Moreover, the declining trend in family size and the tightening of the labor market caused real wages in agriculture to increase by 22% in the last seven years compared to only a 6% increase in the non-agriculture sector [5]. Due to the practice of subsistence agriculture and limited off-farm employment opportunities in the hillside region, Nepalese farmers, especially the youth, are out-migrating to Nepal’s capital city, Kathmandum, and further onwards to the middle eastern and southeast Asian countries, which further creates labor shortages especially in the hills of the country [5,59]. In 2016, Nepal was the second (29.7%) country after Kyrgyzstan (35.4%) in the world in terms of receiving remittance [60]. One of the highest rates of out-migration in Nepal are from the hillside region and farmers are highly dependent on remittances received to support subsistence household expenditures [48].

Nepalese youth are leaving the country in search of employment abroad [59], and the majority of them (95.7%) are men [61]. In this situation, Nepal’s agriculture is feminized; meaning that farming is becoming the de facto role and responsibility of women, who are often left behind with elderly and very young household members [48,62]. Although some would argue that this could potentially lead to female empowerment [60,63], many analysts believe that the feminization of agriculture often increases women’s workload and drudgery [62,64,65]. The following quotes from two young women demonstrate this paradox of empowerment and drudgery.

“My husband is in Qatar for three years for a wage labor job. (…) We have two-acres of land and cannot use a tractor to plough due to its steepness. So, we use to plough by ox/bull when my husband was at home. My father-in-law is too old, he doesn’t have the energy to plough at the age of 86 years old. By religion, we are Hindu, and females are forbidden to plough land by using ox/bull. (…) Due to the out-migration of youth from the village, the wage rate for ploughing land is very expensive. Even though we are ready to pay, we have to wait for a turn to get it done as there is high demand from every household, and we get our turn at the end, where we already missed some weeks of seed planting. If there were small, affordable and easy to use farm tools or machinery, we wouldn’t have to wait for a man to plough our land. (25-year-old woman farmer from Jogimara, Dhading, translated from Nepali)”

“I am a mother of three children, living with my children and my 77-year-old father-in-law in Jogimara, Dhading. My husband is working in Qatar for the past seven years. (…) We only grow the main season crop even though we have three seasons. As wage labor is very expensive, our agricultural harvest is not enough to pay back the cost of producing crops. We have two bullocks at home but being a woman, my religion doesn’t allow me to plough by a bullock. So, my 77 years old father-in-law and 9 years old son plough the land and I do the rest of the agricultural work on our farm. If there are some small farm tools which a female can use to plough land in hilly areas this will be a great help for me. (32-year-old women farmer, Jogimara, Dhading, translated from Nepali)”

Nepalese hillside farming has seen an increase in female-headed households in the past 15 years, partly due to the death of migrant workers in workplace accidents, the social stigma of a widow’s marriage, and long-term family separation resulting in breakups and divorces. Female-headed households in Nepal doubled from 13% in 1995 to 26% in 2010 [66]. These circumstances have created an unprecedented workload and therefore, the need for reducing drudgery through agricultural mechanization in rural areas [67].

In Nepal, male out-migration has created acute labor shortages during the peak farm seasons of planting and harvesting [1,62,65], which favor a high wage rate [67]. Major real wages in Nepalese agriculture increased by 22% in the last seven years compared to only 6% in the non-agricultural sector [66]. The high wage rate significantly contributed to an increase in the cost of production in the agricultural sector [28,44]. These changes have put pressure on hillside farmers, who are increasingly women and the elderly as well as children. Gender and generational divides are a common narrative in farming. In Nepal, agriculture fails to attract youth or younger professionals despite growing wage rates in rural areas. An increasingly high wage rate and labor shortages resulted in the cultivation of only one crop per year by some farmers although it would be possible to grow three crops in irrigated lands. The following quote illustrates an emerging trend in the hillsides of Nepal.

“I am living with my 73-year-old wife in a hillside village near Majhthana, Kaski (…) As we are old and alone at home and don’t have enough money to pay for expensive ox/bullock for ploughing our land, we only grow main season crops and our land remains fallow the rest of the year. If there is something like a small tractor that we can use in hilly areas will be helpful to keep growing our crops. (81-year-old male farmer, translated from Nepali)”

4.3.2. Policy Formulation

Responding to labor shortages and increasing fallow lands in the countryside, MoAD launched the AMPP by realizing the importance of increasing productivity, minimizing the cost of production, reducing human and animal drudgery, and transforming subsistence agriculture [52]. This policy document is the first dedicated agricultural mechanization policy in Nepal. It was launched with the hope of contributing to the goals of the National Agriculture Policy (2004) and the Agribusiness Promotion Policy (2006) [5]. The vision of the AMPP is that agricultural mechanization would lead to increased commercialization and modernization of the existing agricultural system, ultimately contributing to the overall development of the county [52]. The specific objectives are as follows:

- (1)

- to increase agricultural productivity through the development and use of economic and geographically relevant agricultural tools and machinery for sustainable, competitive, and commercialized agriculture;

- (2)

- to increase access by farmers and entrepreneurs to agricultural tools and machinery and associated services through joint public–private partnership;

- (3)

- to identify and promote environment-friendly and female appropriate agricultural tools and machinery; and

- (4)

- to develop institutions that promote agricultural tools and machinery, quality control, monitoring evaluation, and effective dissemination.

As explained further below, it is unclear if formulation of these objectives within current policy includes a balance among the objectives to ensure that emphasis on agricultural productivity and commercialized smallholder farming does not neglect environmental and social sustainability.

4.3.3. Policy Decision

The AMPP has also made it mandatory for machine entrepreneurs (producers, manufacturers, importers or distributors) to provide information in the Nepali language on quality, safety, operation, repair, and maintenance of farm tools and machines because maintenance and availability of spare parts at the local level has been found to be a major challenge in the past. The policy stipulates that to increase access to marginalized farmers, a minimum interest rate loan or subsidy will be provided to individuals or groups of farmers, without collateral, for the purchase of machinery or tools. The policy also aims to develop programs to provide farm tools or machinery for rent to assist those who cannot afford to purchase these items [52]. An insurance provision is also highlighted in the policy for machine operators at a discount. The policy states that as an encouragement, awards will be provided to farmers, businesspersons, researchers or distributors who promote an innovative and useful machine, tool or equipment for the agriculture and livestock sector. This is a clear attempt to promote responsible farm mechanization innovation by identifying stewards of the technologies, but the substantive goals are focused more on agricultural productivity and competitiveness than equitable and environmentally sustainable farming. Nevertheless, the policy also has a subsidy or low-interest loan provision to enable the purchase of farm tools or machinery for commercial production, group farming on a land consolidation basis, and/or for intensive livestock rearing. The policy stipulates that commercialized farms operated by women and youth will receive up 50% capital subsidies for equipment purchases. These policy statements imply that large-scale industrial producers could potentially obtain subsidies for on-farm tools and machines.

The AMPP provides a provision to grant patent rights on the production of modern machines to encourage the private sector in the identification, research, production, and dissemination of farm tools and machinery. It also prioritizes the involvement and collaboration of local institutions for testing and dissemination of technologies. The policy has encouraged cooperatives and private sector organizations to establish small-scale trades or large machine factories in order to enable import substitutions and create local employment. The policy aims to support local or traditional machinery manufacturers, such as blacksmiths, to scale up and achieve commercial production. With respect to tax incentives, the AMPP recommends reductions in the customs and value-added tax (VAT) pertaining to the import of raw materials required to produce tools or machinery in the country. Under the policy, domestic production will not be charged a VAT or other tariffs, while private sector manufacturers will receive reduced taxation for a limited period. Furthermore, private sector entrepreneurs, farmers, groups or cooperatives will receive a discount on VAT and customs tariffs.

By considering the diverse topography of Nepal, the AMPP recommends the establishment of at least one farm machinery research center in the high mountains, one in the mid-hills, and one in the mid-western region. In the eastern part of the country, the policy proposes to develop the capacity of an existing research center, the Agricultural Implement Research Unit in Birgunj, which was established in 1960. Finally, the policy has recognized the hardship of hill farmers, most of whom are women and the elderly, and the need for developing geographically and socially appropriate machinery and farm tools.

4.3.4. Policy Implementation

One of the most significant initiatives to implement the AMPP is the launch of the Prime Minister’s Agricultural Modernization Project in line with ADS in 2016 [46]. As we can see from the following narrative, returning migrant youths have benefited from this project regarding the use of modern machinery in commercial agricultural production in peri-urban areas of the country.

“I started commercial vegetable farming after returning from 7 years in Qatar. I mostly grow seasonal vegetables. (…) I get 85% subsidy from PM-AMP to establish my sophisticated greenhouse farm. I also receive regular technical support from agricultural technicians/experts in vegetable growing, drip irrigation and insect pest management. (…). I also rented land labelers and tractors from a custom hiring center at a subsidized rate. I am happy that the government is helping returning migrants like me to come back to agriculture. (…) I have a contract with PM-AMP for 10 years to continue this farming. (35-year-old returned male migrant from Chauthe, Kaski, translated from Nepali).”

The MoALD promotes a custom hiring system by acknowledging the fact that smallholder farmers in hilly areas cannot afford farm tools and machinery at the individual household level. The MoALD learned from the previously discussed case of providing farmers with the use of tractors in custom hiring system in Bangladesh, as well as experience from southern India and the Terai flatlands of Nepal, and it started to promote such custom hiring systems under the PM-AMP. For example, Kaski is defined as a vegetable zone in APP and supports have been directed towards it. There is, however, only one custom hiring shop in Pokhara in Kaski District, which provides services in and around the city. Although, since the cities and villages where farmers grow crops are so scattered and difficult to reach, the custom hiring service is not as effective as targeted. This was indicated in an interview with a custom hiring service provider, as follows.

“I get a subsidy to purchase all the farm tools and machinery such as a tractor, tree cutter, thresher, and harvester. But the problem is that we are not able to create awareness among farmers about our service. Even though we want to serve them on a rental basis, the travel cost is so high to reach to the village and come back and farmers will be in a loss to pay for us. So, there should be some mechanism to provide service to a maximum number of farmers on an efficient way, but I don’t know what it would look like. (custom hiring service provider from Kaski, translated from Nepali).”

4.3.5. Policy Review

This research identified three areas for policy review. One area is the question of scale-appropriate and gender-sensitive agricultural mechanization that favors alternative agricultural mechanization innovation pathways [27,28]. From the perspective on social inclusion, the AMPP is gender-sensitive and tries to use smallholder and small-scale mechanization to address the issues of labor scarcity and the workload of women. This policy prioritizes machines that will help reduce women’s drudgery. However, as large-scale mechanization is becoming possible in some areas with increasing road connectivity on the hillside regions, this pathway of innovation, in addition to not being suitable for hillside farms, can reinforce traditional gender roles and cultural taboos against women operating equipment as Kansanga et al. [10] discussed in their recent study. This can increase women’s dependency on the few men in the countryside who are available to operate modern machinery [38]. This paradox of women’s increasingly important role in agriculture without concurrent social and technological change is also evident from discussions held in a focus group in Majhthana Village of Kaski District. This community discussion among women and men farmers indicated that they received a mini tiller with the help of the SAK Nepal project of Local Initiatives for Biodiversity, Research, and Development (LI-BIRD), a national Non-governmental Organization (NGO) and the District Agricultural Development Office (DADO), a local government body working in Kaski in 2017. The data was collected before the recent restructuring of the agricultural extension system in Nepal. Hence, the name of some government departments may not match with what are currently in place. The project provided a 25% subsidy and DADO provided the rest of the money to buy the mini tiller. As per the demand of women farmers, they bought a lightweight mini tiller (small 2WT), but the problem was that in steep land with lots of stones in the soil, the mini tiller seized up and failed to dig out properly. Then, the farmers had to return it and a heavy mini tiller (large 2WT) was brought in for proper ploughing of the land. This example illustrates how implementation of policy can often end up with problematic results due to unforeseen circumstances and solutions that redirect interventions away from what women can do and control within their agricultural roles and responsibilities.

Another area of the policy review concerns the generational narrative of hillside farming. Youths are unwilling to take over farms and elderly parents are often left without a choice to continue farming with what is possible, often modifying cropping patterns or using machines and tools. This finding is consistent with what other researchers have observed in the hillsides of Nepal. While on a visit to the Makwanpur District, Biggs and Justice [12] noted that one of the first users of the mini tillers was an older couple (a husband aged 68 and wife aged 58) whose children were working in Kathmandu. They were both operating the mini tiller to plow their 0.66 ha. For them, this small equipment was effectively addressing the problems of their lack of labor and more generally, an aging farm population.

The final area of policy review is about mechanized management of fallow land and invasive species control in the hills of Nepal where rural people are migrating to urban areas at an ever greater extent [49,68]. Consistent with the findings of this study, Khanal [68] also reported that 40% of farmers from the Kaski region did not cultivate at least one of their farmlands for more than two successive years. Jaquet et al. [48] also highlighted that out-migration, education, and moving from rural to urban regions changed the land-use dynamics in the hills of Nepal. The acute scarcity of labor and decreasing trend of rearing bullocks/ox for ploughing of the land resulted in the increased wage rate. Research participants in this study stated that farmers in the hills are rearing large numbers of goats as these animals are less labor intensive than crop production and obtain a higher market price in a shorter period of time. As most of the terraced lands are fallow, they are used for grazing instead of cropping, and in some places, lands become covered by unwanted wild invasive plant and animal species, which often grow into bushes [48,49]. The following statement is from one of the hillside farmers in a focus group discussion.

I am 72-year-old man living with my 75-year-old wife in a ward of Majhthana, one of the mid-hills of Kaski. Due to the 2015 earthquake, many people were scared and moved with their sons nearer to the city in flat lands. they left their old, earthquake affected houses and left the land fallow in the village. We are poor and cannot afford to move to the urban areas. We are trying to grow our crops, but most of the crops and vegetables were destroyed by monkeys which are increasing in high numbers due to dense growing forest on the fallow land. (…) As most of the houses in the villages are empty, rodents get enough space to live and increase their population and they come to our home and land to destroy our crops. Further, weeds such as Banmara (Ageratina adenophora) and Gandhe (Ageratum conyzoides) are increasing in the empty land of our neighbors which also affect our crops. (Male farmer from Majhthana, Kaski, translated from Nepali).

Altogether, from agenda-setting to policy formulation, decision, implementation, and review, the data collected at the local level suggest that agricultural mechanization policy in Nepal would benefit from analysis through the lens of responsible innovation. This is now the focus of the following section of the paper.

5. Responsible Innovation: An Analysis of Nepal’s AMPP 2014

5.1. Anticipation and Inclusion

It is apparent that the AMPP was developed through broader-based stakeholder consultation and learned lessons from earlier agricultural policies which were silent on mechanization for hillside farms. Public engagement in the development of this policy was by no means a shortcoming but this process could more clearly differentiate between the incumbent and alternative agricultural mechanization pathways that evolved over 80 years of farm mechanization in Nepal. Rather than this policy being an anticipatory and inclusive process, it was a reaction to increasing youth out-migration from rural Nepal and the feminization of agriculture. The findings of this study are consistent with the literature that suggests that agriculture still remains one of the least attractive area of waged employment for youth [49,68]. Hence, implementation and subsequent amendments of the mechanization policy should engage youth and women and seek ways in which the broader range of stakeholders also engage with younger generations and women farmers in order to ensure visioning and foresight of agricultural mechanization innovation has appropriate strategies for the next 20 to 30 years [19]. Evidence from this research indicates that scenario-building exercises should also engage with returning migrants, who are often male, and who may also influence youth and women’s roles in agriculture [69].

When it comes to inclusion in foresight exercises that anticipate innovation, a diversity of factors should be considered [19]. Youth, generational differences, and gender will definitely be important. Other relevant considerations should be farm holding size, ecology, social and economic class, access to capital (including remittances), and education [7,15]. For example, as recognized by Gurung-Goodrich et al. [70], participatory development and testing of farm machines can help determine mechanization innovation suitable for hillside farmers who cultivate a diversity of crops on narrow terraces. Another example is the introduction of the pedal thresher in the hills of Nepal. This experiment was done by a project “Revalorizing Small Millets in Rain-fed Regions of South Asia” (RESMISA)”, which was a joint initiative of Canadian Universities, Nepal’s Research Institution (NARC), and LI-BIRD and local farmers groups with the funding from Canada’s International Development Research Centre (IDRC) and the Department of Foreign Affairs, Trade and Development (DFATD) (now renamed as the Global Affairs Canada [GAC]) under the Canadian International Food Security Research Fund (CIFSRF) [71]. Under this project, LI-BIRD introduced paddle operated millet threshers developed by the Agricultural Engineering Division of the Nepal Agricultural Research Council (AED/NARC) in three farmer groups in Kaski and Dhading, in the mid-hill districts of Nepal. The pedal thresher needs two persons to operate: one to run the pedal and another for feeding in the panicles and collecting grains. This resulted in the participation of men in the threshing process which also helped women to share their workload. However, both men and women farmers complained about leg pains while operating the pedal thresher and demanded the thresher to be fitted with an electric motor. Then, the adapted power thresher was introduced in different project sites. The test at these sites revealed that the power operated threshers were more suitable for farmers’ needs, reducing human drudgery and addressing shortages of labor as a result of out-migration of more energetic youth. The electric machines reduced physical drudgery, cut the time consumed in performing the tasks, and reduced the discomfort or adverse health effects encountered by the farmers operating the pedal thresher. In an impact study of this initiative, 83% of respondents (94.7% of them women) found threshers to be an important alternative to manual threshing of finger millets [64]. Hence, these examples illustrate the importance of regional research centers involved in the mechanization policy embracing participatory research and collaborative farmer testing of machines in order to innovate and make technologies more suitable for local conditions [72].

Research and innovation activities should not only engage end-users in technology development, but also involve farmers networking with a range of other stakeholders, including mechanical engineers, educators from agricultural and generic engineering schools, agricultural researchers, development practitioners, agricultural extension workers, machine importers, local entrepreneurs, and artisanal developers of farm tools and machines [15]. Ajilore and Fatunbi [73] also highlighted that there is an urgent need for the participation of diverse actors/agricultural futurists in foresight exercises so that they can predict the future of agriculture and build the forthcoming development discourses and agricultural policies and guide their effective implementation. Further, research findings also revealed that potential technological failure and its implication on small-holder terrace farmers are not discussed much in the AMPP, which is a critical indicator of responsible innovation [7,15]. Bronson [25] emphasized that innovation is not only targeted to solve the problem, but it also reorders the way society works, and changes the power relation and authority among different stakeholders along with farmers involved in the innovation system. Thus, visioning and foresight exercises should involve broad conversations at the beginning of the innovation process in order to envision the societies we want after application of the innovation [16,19]. Eastwood et al. [15], in the study of smart dairy in New Zealand, summarized that anticipation process can be complicated to some extent due to the market driven nature of the innovations, as successful use of innovation largely depends on market demands and the political economic infrastructure [25]. However, it is the state’s responsibility to track the innovations as per the benefit of society and the environment which is evident from the Bronson’s [25] (p. 10) statement on smart farming as “technological equity and broad social progress has to be secured through careful and ethical decisions taken by key players in the innovation ecosystem”.

To bring transformative change through innovation, innovation policy should consider the major four aspects of failures in the policy process—“directionality, policy coordination, demand-articulation and reflexivity” [19] (p. 1562).

5.2. Reflexivity and Responsiveness

As discussed earlier, Nepal’s agricultural mechanization policy is also a reactive response to the current shortage of farmworkers. It could have been more demand-driven and reflexive of the private sector-led trajectory of large-scale mechanization that promoted big engines which are not suitable for hillside farms or irresponsible innovation for the hills of Nepal. Moreover, the national agricultural research system has focused more on crop variety development than small-scale mechanization [5]. Nepal is not an exception to the dominant trajectory of large-scale mechanization seen globally that often obscures alternative agricultural mechanization innovation pathways that are “under the radar”. For example, as Biggs and Justice [12] found, the Indian government promoted big engines (4WTs) and left behind many smallholder farmers with respect to agricultural mechanization. The big engine “lock-in” trajectory of mechanization was effective to increase yield only in areas of high production potential where the Green Revolution associated technologies were deemed suitable [74]. As our empirical results demonstrate, we need to make a choice between irresponsible mechanization innovation and responsible mechanization innovation of hillside farming systems in developing countries like Nepal (Figure 3). The former is what has happened in the past while the latter is well recognized in the AMPP. If responsible mechanization innovation of hillside farming is not possible (e.g., 2WTs, power tools), responsible stagnation would be better for the well-being of vulnerable communities and the overall health of the agroecosystems than irresponsible innovation through the promotion of the mainstream trajectory of mechanization innovation through the adoption of large machines (e.g., 4WTs).

Figure 3.

A matrix of innovation and stagnation for hillside farming. Note: This typology is developed based on the local context of hillside farming and will have to be used with caution in other contexts. For example, the use of large-scale machines may not be irresponsible innovation in many contexts.

Although these countries differ in topography, Nepal can learn from the alternative mechanization pathways of Bangladesh, noted earlier, in which they promoted small engines (2WTs) with more than 80% of lands being under mechanized tillage [12]. This evidence shows that small engines have greater potential for promoting sustainable hillside farming in a country like Nepal where the majority of farmers are smallholder terrace cultivators [1,28,68]. Furthermore, in the past, farm machines with multiple uses survived longer in the market, because they provided more benefits to the buyer than big machines that are used for specific tasks. For example, in Bangladesh and Nepal, small machines are owned by people who may own some land, but generally, their services are hired out to others for multiple purposes, including transportation and haulage [12,44]. Hence, Nepal’s mechanization policy clearly responded to the demand for machine rentals through subsidies for custom hiring service providers, but the policy does not necessarily address the need for promoting multipurpose small machines accessible to all interested hillside farmers, clearly not recognizing the undercurrent of alternative pathways of agricultural mechanization innovation (Table 3).

Table 3.

Responsible agricultural mechanization innovation pathways in Nepal.

Research results and the available literature show that yet another area of reflexivity that may be of benefit to a successful implementation of agricultural mechanization innovation in Nepal concerns the economic, social, and environmental impacts of mechanization [70,75]. As Baudron et al. [13] noted and as revealed by this study, alternative pathways of agricultural mechanization could reduce the negative social and environmental impacts of industrial agriculture. First, it may be possible to mechanize without land consolidation, intensification, and labor displacement. For this to happen, mechanization should address niche-specific needs suitable for small-scale terraced farming, such as in the hills and mountains of Nepal. Rather than consolidating land to make it suitable to operate larger machines, which results in capital accumulation by a few well-off landholders, the policy should encourage the consolidation of production, through collective marketing and input cooperatives. Such cooperatives can generate extra income for their members through machine and tool rentals for small-scale harvesting, processing, and hauling [27]. There has been a recent establishment of some collective marketing and storage facilities focusing on farmers in some cities like Pokhara, but it is still debatable whether it serves smallholder farmers’ needs (direct observation by the research team). Second, industrial agriculture that uses heavy equipment for chemical-intensive monoculture has led to soil degradation, biodiversity loss, marginalization of family farms, and replacement of local family labor [76]. However, alternative small-scale mechanization, for example, the small machines that are used in conservation agriculture, such as no-till drills, could be undertaken without soil degradation, labor replacement, and gender exclusion, while maintaining a diversity of crops, trees, and pollinators [11,77]. Small machines could pass through a canopy of agroforestry trees and between intercropped rows without replacing much of the employment opportunities of family labor. In addition, small-scale mechanization can address the chronic labor shortages in hills and mountains, reduce drudgery to women, reduce the cost of agricultural production, and facilitate on-site processing of high-value crops [1,14,38,67].

Farm mechanization could be implemented with two purposes in mind—increasing farm power and decreasing power demand through increased efficiency, including the use of solar-powered machines, biogas plants, household communication gadgets, and handheld tools. The lack of availability and high price of energy (hydroelectricity and fossil fuels) may have been the central underlying causes for the lack of promotion of agricultural mechanization in the country. For example, 25% of the horsepower in agriculture in India comes from electric engines whereas it is only 11% in Nepal [12]. Most 2WTs have been powered by diesel. Smaller-scale shallow tube wells have spread more rapidly where diesel/petrol pump sets for pumping from deep tube wells were available and promoted. Nepal’s underdeveloped hydroelectricity potential has also directly affected the choice of technique in relation to electric or diesel engines for pump sets and other farm machines [1,67]. Although there is a recent increase in hydroelectricity production, it is too early to predict its effect on promoting farm machinery use in the hills of Nepal because hydropower can run only stationary machines unless battery-operated machines are adopted for hillside farming [78].

6. Conclusion and Recommendations

This study indicates that initially, during the second half of the twentieth century, despite the silence of major agricultural policies on the topic of farm mechanization, the government of Nepal was tacitly not in favor of agricultural industrialization out of a fear that machines would displace farm labor. In the absence of a national policy dialogue and decisions, the private sector indiscriminately marketed farm machines, small or large, as long as they were profitable for them, particularly with the introduction of machines from neighboring countries like India and China. This irresponsible mechanization innovation unintentionally created flatland biases in Nepal’s farm mechanization.

Recently, due to the increasing out-migration of youth and the feminization of agriculture in the Nepali hillside, there has been a serious labor scarcity and a higher wage rate that adversely affects smallholder agricultural production and productivity. This study reports that many hillside farms are either increasingly left fallow or cultivated for only one season although they could grow two or three crops in a year. In response to this, the government introduced its first Agriculture Mechanization Promotion Policy in 2014. Although this policy is a step forward and provides attractive incentives to promote private sector involvement in farm mechanization, the policy does not address whether the government wishes to reinforce the suboptimal incumbent trajectory of large-scale mechanization. This reflexive effort is necessary for the review of irresponsible innovation for the local biophysical context of hillside farms, a reorientation to responsible agricultural mechanization innovation pathways. Although gender inclusion has been discussed in the policy, it is likely that large-scale mechanization for productivity and competitiveness would further reinforce patriarchal gender relations because machines are within the comfort zone of male roles and responsibilities. The policy could have introduced provisions that would examine and potentially transform gender relations in agriculture without necessarily reducing the issue to one of only male and youth out-migration and rural farm labor shortages. As a result, human and animal drudgery will continue, and farming will fail to achieve its potential as a respected profession for aspiring youths and sustainable agricultural resource management by smallholders. Overall, the Government of Nepal is following a productive value in promoting agricultural innovation aiming to transform the longtime subsistence-oriented farming into commercial agriculture. The recent priority of MoALD favors larger farmers, notably commercial farmers in peri urban to urban areas. There are few ongoing programs on small, scale-appropriate, machinery development suitable for small farmers, but not prioritized enough in the mechanization policy.

Governance of agricultural mechanization innovation is a paradox in terms of whether it promotes state regulation or the free market. Neither of these two developments is negative per se but depends instead on the local context. The free market in the past favored larger 4WTs whereas the promotion of smaller 2WTs required non-market institutional interventions from the state and/or civil society. Hence, the state should develop specific guideline(s) for the effective implementation of a new mechanization policy in order to not only review the incumbent mechanization trajectory but also alternative pathways of agricultural mechanization innovation suitable for hillside farming systems. Similarly, other related policies and legislation (concerning land reform, transportation, energy, irrigation, agricultural extension, relevant industries, roads, transportation, the labor sector, etc.) also need to be reviewed and streamlined in order to move towards alternative pathways of responsible agricultural mechanization innovation. For example, reducing drudgery through mechanization can make agriculture attractive to youth especially young males, who are generally attracted by machines and technology. This paper recommends the following three strategies to promote responsible agricultural mechanization innovation pathways in the Nepal’s hillside.

First, stakeholders should anticipate that there can be further land fragmentation of hillside farms, and as such, intensive monocultures can never be imagined without severely adverse social and environmental consequences. Hence, alternative pathways of agricultural mechanization innovation should be responsive to the needs of farmers cultivating small land parcels on narrow hillside terraces, conserving the existing diversity of crops and agroforestry species on-farm. The custom hiring service is already common in Terai especially for the use of tractors and threshers, but it has just been initiated in the hills. However, the scattered nature of households in rural villages, and the improper road connectivity in the hills, challenge the effective implementation of this system. Nevertheless, in Bangladesh, India, and Sub-Saharan African countries as well, custom hiring services seem to be effective to meet the need of small farmers [27,28,44]. Participation of farming community is to offer custom hiring services in an effective way.

Second, the guideline(s) for effective implementation of an improved mechanization policy should be reflexive concerning the incumbent practices because, in the past, policies failed to promote hillside farm mechanization. This practice of reflexivity can introduce tensions among winners and losers as a result of state and/or civil society interventions in smaller-scale farm mechanization. Although the incumbent trajectory and alternative mechanization pathways should not necessarily be dichotomous, agricultural mechanization innovation champions should be identified to facilitate cooperative and competitive relationships between these two contested pathways of mechanization [79]. In the past, importers of 2WTs served as champions of mechanization in Nepal to substitute the import of Indian 4WTs.

Third and finally, the policy implementation guidelines should make it clear that domestically produced machines are more likely to be adaptable to local biophysical, ecological, social, economic, and cultural situations. In this process, it would be crucial to develop the capacity of local entrepreneurs (e.g., blacksmiths) and in-country agro-related metalworking industries. For this to happen successfully, new policy guidelines should be developed to promote institutional innovation, communication, and learning to enable farm mechanization at the national, provincial, and local levels. What is important in this process is to give greater emphasis on the inclusion of engineers, innovators, entrepreneurs, artisans, and end-users in participatory technology development and testing, so that small machines and tools can be produced domestically and locally. Further, import tax on raw materials to develop the machinery should be lowered or subsidized so that local entrepreneurs can develop a technology within the country that is affordable to smallholder hillside farmers. Otherwise, mass production and the import of technologies from neighboring countries such as India and China always dominate the local products. Strengthening the capacity of national and regional manufacturing establishments would be important, but policy guidelines should clearly differentiate the incumbent large-scale technological trajectory from alternative, scale-appropriate and more socially and environmentally responsible agricultural mechanization innovation. Our conclusions are consistent with the literature that using inclusive mechanization innovation processes is needed in Nepal before society and agriculture transforms into just and sustainable systems [8,25].

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, R.D., H.N.G., L.P.P. and K.P.; methodology, R.D., L.P.P. and H.N.G.; software, R.D.; validation, M.N.R., D.G., H.H.-O. and B.T.; formal analysis, R.D. and L.P.P.; investigation, R.D.; resources, B.T. and M.N.R.; data curation, R.D.; writing—original draft preparation, R.D. and L.P.P.; writing—review and editing, H.H.-O., M.N.R., D.G., L.P.P., K.P., B.T., and H.N.G.; visualization, R.D. and L.P.P.; supervision, K.P. and H.H.O.; project administration, R.D. and B.T.; funding acquisition, R.D. and M.N.R. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

Rachana Devkota was supported by an IDRC’s David and Ruth Hopper and Ramesh and Pilar Bhatia Canada Research Fellowship and a grant to Manish N. Raizada from the Canadian International Food Security Research Fund (CIFSRF), jointly funded by the International Development Research Centre (IDRC, Ottawa) and Global Affairs Canada (GAC).

Acknowledgments

We are thankful towards John Fitzsimons (University of Guelph, Canada) for his significant contribution in reviewing and English editing the paper. Thanks to Pashupati Chaudhary (Local Initiatives for Biodiversity, Research, and Development, (LI-BIRD) Nepal) for providing relevant articles and sharing his experiences during the preparation of this article.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Takeshima, H.; Shrestha, R.B.; Kaphle, B.D.; Karkee, M.; Pokhrel, S.; Kumar, A. Effects of Agricultural Mechanization on Smallholders and Their Self-Selection into Farming: An Insight from the Nepal Terai; International Food Policy Research Institute: Washington, DC, USA, 2016; Volume 1583, pp. 1–36. [Google Scholar]

- Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nation (FAO). Nepal and FAO Building Food and Nutrition Security through Sustainable Agricultural Development; FAO: Kathmandu, Nepal, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- McNulty, P.; Grace, P.M. Agricultural Mechanization and Automation; Encyclopedia of Life Support Systems (EOLSS): Paris, France, 2009; Volume 1, Available online: http://www.eolss.net/sample-chapters/c10/E5-11-00-00.pdf (accessed on 15 August 2019). [CrossRef]

- Parayil, G. The green revolution in India: A case study of technological change. Technol. Cult. 1992, 33, 737–756. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ministry of Agricultural Development (MoAD). Agriculture Development Strategy (ADS) 2014; Ministry of Agricultural Development: Singhdurbar, Nepal, 2014.

- Climent, J.B. From linearity to holism in technology-transfer models. J. Technol. Transf. 1993, 18, 75–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rose, D.C.; Chilvers, J. Agriculture 4.0: Broadening responsible innovation in an era of smart farming. Front. Sustain. Food Syst. 2018, 2, 87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klerkx, L.; Jakku, E.; Labarthe, P. A review of social science on digital agriculture, smart farming and agriculture 4.0: New contributions and a future research agenda. NJAS Wagening. J. Life Sci. 2019, 90–91, 100315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gunton, R.M.; Firbank, L.G.; Inman, A.; Winter, D.M. How scalable is sustainable intensification? Nat. Plants 2016, 2, 16065. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Kansanga, M.M.; Antabe, R.; Sano, Y.; Mason-Renton, S.; Luginaah, I. A feminist political ecology of agricultural mechanization and evolving gendered on-farm labor dynamics in northern Ghana. Gend. Technol. Dev. 2019, 23, 1–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sims, B.; Kienzle, J. Mechanization of conservation agriculture for smallholders: Issues and options for sustainable intensification. Environments 2015, 2, 139–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biggs, S.; Justice, S. Rural and Agricultural Mechanization: A History of the Spread of Small Engines in Selected Asian Countries; International Food Policy Research Institute: Washington, DC, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Baudron, F.; Sims, B.; Justice, S.; Kahan, D.G.; Rose, R.; Mkomwa, S.; Kaumbutho, P.; Sariah, J.; Nazare, R.; Moges, G.; et al. Re-examining appropriate mechanization in Eastern and Southern Africa: Two-wheel tractors, conservation agriculture, and private sector involvement. Food Secur. 2015, 7, 889–904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mottaleb, K.A.; Krupnik, T.J.; Erenstein, O. Factors associated with small-scale agricultural machinery adoption in Bangladesh: Census findings. J. Rural Stud. 2016, 46, 155–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eastwood, C.; Klerkx, L.; Ayre, M.; Rue, B.D. Managing socio-ethical challenges in the development of smart farming: From a fragmented to a comprehensive approach for responsible research and innovation. J. Agric. Environ. Ethics 2019, 32, 741–768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stilgoe, J.; Owen, R.; Macnaghten, P. Developing a framework for responsible innovation. Res. Policy 2013, 42, 1568–1580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biggs, S.; Justice, S.; Lewis, D. Patterns of rural mechanisation, energy and employment in South Asia: Reopening the debate. Econ. Political Wkly. 2011, 46, 78–82. [Google Scholar]

- Guston, D.H. Limits to responsible innovation: Who could be against that? J. Responsible Innov. 2015, 2, 1–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schot, J.; Steinmueller, W.E. Three frames for innovation policy: R&D, systems of innovation and transformative change. Res. Policy 2018, 47, 1554–1567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Hoop, E.; Pols, A.; Romijn, H. Limits to responsible innovation. J. Responsible Innov. 2016, 3, 110–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holt-Giménez, E. One billion hungry: Can we feed the world? By Gordon Conway. Book review. Agroecol. Sustain. Food Syst. 2013, 37, 968–971. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burget, M.; Bardone, E.; Pedaste, M. Definitions and conceptual dimensions of responsible research and innovation: A literature review. Sci. Eng. Ethics 2017, 23, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Owen, R.; Stilgoe, J.; Macnaghten, P.; Gorman, M.; Fisher, E.; Guston, D. A framework for responsible innovation. In Responsible Innovation; Owen, R., Bessant, J., Heintz, M., Eds.; John Wiley & Sons, Ltd.: Chichester, UK, 2013; pp. 27–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nordmann, A. Responsible innovation, the art and craft of anticipation. J. Responsible Innov. 2014, 1, 87–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bronson, K. Smart farming: Including rights holders for responsible agricultural innovation. Technol. Innov. Manag. Rev. 2018, 8, 7–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bos, B.; Grin, J. “Doing” reflexive modernization in pig husbandry: The hard work of changing the course of a river. Sci. Technol. Hum. Values 2008, 33, 480–507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aryal, J.P.; Rahut, D.B.; Maharjan, S.; Erenstein, O. Understanding factors associated with agricultural mechanization: A Bangladesh case. World Dev. Perspect. 2019, 13, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paudel, G.P.; KC, D.B.; Rahut, D.B.; Justice, S.E.; McDonald, A.J. Scale-appropriate mechanization impacts on productivity among smallholders: Evidence from rice systems in the mid-hills of Nepal. Land Use Policy 2019, 85, 104–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Justice, S.; Biggs, S. Socially equitable mechanisation in Nepal. Appropr. Technol. 2004, 31, 7–9. [Google Scholar]

- Nielsen, M.V. The concept of responsiveness in the governance of research and innovation. Sci. Public Policy 2016, 43, 831–839. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pant, L.P.; Hambly Odame, H. Broadband for a sustainable digital future of rural communities: A reflexive interactive assessment. J. Rural Stud. 2017, 54, 435–450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]