Abstract

It remains uncertain as to whether people who support waste classification end up transforming such environmental initiation into reality. Thus, to investigate the intention and actual behavior of Chinese residents on waste classification and the influencing factors, this study integrated the theory of planned behavior (TPB) and norm activation model (NAM), and extended them by adding external information factors, namely information publicity type and information quality. A questionnaire survey was conducted in mainland China, and the primary data from 349 individuals were analyzed by partial least squares structural equation modeling (PLS-SEM) to verify the model. The conclusions confirmed that personal norm was a major predictor of residents’ waste classification intention, and there exists a gap between Chinese residents’ waste classification intentions and actual behaviors. Furthermore, strategies such as moral education and information publicity are important in policy implementation. These findings are helpful for Chinese policymakers in promoting and planning waste classification, and also provide experiences to other countries for combating similar waste problems in their metropolises.

1. Introduction

Years of urbanization and industrialization have made China’s economy prosperous, ascending to be the world’s second-largest economy. While enjoying the benefits of growing population and per capita consumption, China also has to face the prominent problem of urban waste management [1]. At present, almost two-thirds of Chinese cities are facing the dilemma of being surrounded by waste. Due to the lack of efficient treatment of waste, the rapid accumulation of waste not only deteriorates the ecological environment, but also leads to a serious waste of resources. In fact, the waste is not endowed by nature to human beings, but is the by-products of humans’ long-term production and living practice. The 19th National Congress of the Communist Party of China (CPC) issued guidelines to give full play to the important role of the public in a multi-subject environmental governance system, which provides institutional support for the implementation of waste classification among residents. Pushing waste classification is important in solving the Chinese cities’ dilemma of being surrounded by waste, and it is necessary and urgent to engage everyone in waste management [2,3,4]. Therefore, understanding the public’s psychological experience and behavioral decisions on waste classification is instructive for the government to implement the corresponding intervention strategies.

In academic circles, scholars have shown great passion for the behavior decision pattern of micro-individuals in various contexts [5,6,7]. For example, some social psychologists believe that humankind is rational and goal-oriented. Thus, the concept of the theory of planned behavior (TPB) was proposed to explore how people change their behavior patterns [8]. This theory suggests that human behavior is the result of rational choice, and thus makes an in-depth analysis of the influence of behavioral intention. Other scholars argue that it is not enough to explore the behavior decision pattern only from the perspective of rational choice, considering that the role of irrational factors, such as moral obligation, may be overlooked [9,10]. For example, the norm activation model (NAM) is more reflective of altruism because it highlights the role of moral obligation in motivating individuals’ behaviors [11]. It is clear that waste classification is not a purely egoistic behavior, but also implies a sense of moral obligation for residents. Therefore, one of the purposes of this study is to investigate the intentions of Chinese residents for waste classification and the influencing factors through the lens of the TPB and NAM.

As the research on individual behavior at the micro-level has gradually deepened, it is untenable to study humans’ behavioral intentions in isolation. Some scholars believed that there existed a gap between humans’ declared intentions and their actual behaviors in diverse contexts [12]. Notably, the problem may also lie in waste classification practices in many countries, including China. According to [13], individual participation will be low even in case of high environmental awareness and a positive attitude towards waste recycling. This implies that there may be other factors that influence the transformation from humans’ intentions to actual behavior. Prior scholars found that information had been emphasized as an external factor to facilitate an individual’s behavior [14,15], and information publicity had been utilized as an environmental governance tool. Similarly, information publicity about waste classification may also be important in motivating residents to classify waste correctly. However, few studies have examined the role of information publicity in the relationship between residents’ waste classification intentions and behaviors. Therefore, this study further extended the NAM–TPB model by adding external information factors, namely information publicity type and information quality, to investigate their effects on residents’ waste classification behaviors.

The contribution of this study includes the following aspects. Firstly, this study constructed a comprehensive framework under the theory of the NAM and TPB to analyze Chinese residents’ waste classification intention. Such a framework considers the two aspects of egoistic and altruistic factors influencing human behavioral intention. It addresses the drawbacks of using a single theory to explain human behavioral intention, and is more suitable for analyzing such pro-environmental and pro-social behavior. Secondly, unlike other studies that focused solely on analyzing intention, this study also observed human actual behavior and discussed the intention–behavior gap in waste classification movements, which was a frontier of behavioral research. Thirdly, this study extended the NAM–TPB model by considering the role of information in facilitating one’s behavior.

Based on the previous research, a questionnaire on residents’ waste classification behavior was designed. The data compiled from the questionnaire covering 349 individuals were analyzed by structural equation modeling (SEM) to test the extended NAM–TPB model in this study. The results showed that in order to promote and plan waste classification policy, policymakers should bear in mind that the role of moral education and information publicity in regulating residents’ waste classification behavior should not be ignored. In addition, the finding has facilitated the other countries to learn from China’s experience in handling the waste problem.

In the following sections, the study begins by reviewing the literature to illustrate the theoretical motivation behind this study, in which the elements of the extended NAM–TPB model are elucidated. Next, the methodology of the research is explored, and the results are analyzed. Based on the results, this study proposes the implications for reality. Finally, the limitations and future work of this study are highlighted.

2. Theoretical Background and Research Review

2.1. Background of Chinese Waste Classification

The deteriorating waste problem is just like a time bomb that threatens sustainable development in contemporary China. According to the Information on the Volumes of Solid Waste in Large and Medium-Sized Cities Across the Country (hereinafter referred to as “report”), the total waste generation is increasing at a rate of 8–10% per year, which nearly exceeds the GDP growth. China produces more than 1 kg of waste per person per day, which is close to the level of developed countries. In addition, the report showed that in 2013, 161 million tons of household waste was generated in 261 cities [16], while in 2017, 200 million tons of household waste was generated in 202 cities [17]. It was found that, although the cities that published the waste data in 2013 were more than the cities that did in 2017, the published total amount of household waste generation increased from 2013 to 2017.

Hence, dealing with this great volume of waste more effectively has become a major concern of Chinese governments. Waste classification is the classification of different kinds of waste according to certain standards. On the one hand, waste classification can avoid waste with recycling value from being landfilled or incinerated, which reduces waste disposal costs and realizes waste resource utilization. On the other hand, it can avoid air pollution and heavy metal pollution caused by the mixed landfilling [18]. As early as the 1970s, waste classification has been put into effective use in some industrialized countries, such as Japan and Germany [19]. However, it was not until the beginning of the millennium that China began to pilot waste classification policies in Beijing, Shanghai and other metropolises. Scholars and practitioners have explored the patterns and policies of waste classification for more than a decade [3,20]. In 2019, the regulations on the management of domestic waste in Shanghai came into force, stipulating the waste classification standards and the reward and punishment measures, which officially marked that waste classification in China has entered the mandatory stage. However, it is still worth considering whether these patterns work. In most cases, residents are the major participants in waste classification, and this has resulted in low classification efficiency and low public participation problems. Therefore, it is also of great theoretical and practical significance to consider what encourages or hinders public intention on waste classification.

2.2. Reviews on the Theory of Planned Behavior

The TPB was developed by Ajzen, who suggests that human activities are governed by volitional control so that people can easily capture the characteristics of human behavior just by identifying the determinants of intentions [8,21]. There are three antecedent variables in the TPB, perceived behavioral control, attitude, and subjective norm. Perceived behavioral control is defined as the difficulty that an individual perceives when s/he performs a particular action. Attitude is used to express whether an individual’s evaluation of a particular action is negative or positive. Subjective norm refers to influences on an individual’s intention from the society, which may be considered as peer pressure or the restrictions from laws and regulations [22].

Recently, scholars have begun to conduct various research on pro-environmental behavior through the lens of the TPB [5,7]. For example, Borthakur and Govind conducted a study under the framework of the TPB [23]. They found that more than 80% of the residents hold positive intentions towards e-waste recycling, and that perceived behavioral control affected behavioral intention more significantly. Therefore, they advocated that the residents should obtain recycling information and recycling facilities. Similar research was conducted by Papaoikonomou et al who predicted residents’ intention on electronic waste recycling in Greece [7]. Their findings provided some insights into what incentives should be given to promote the citizens’ attention towards electronic waste. In addition, Zahedi et al. applied the TPB to explore what affected the public willingness to pay for pollution reduction [24]. Their survey covered 406 respondents in Catalonia, and found that the three main factors of the TPB explained most of the variation of public willingness to pay for pollution reduction. Using energy-saving and low-carbon vehicles also benefits pollution reduction. In particular, the demand for developing new energy is increasingly urgent now, but how consumers think of new energy products is still unclear. Therefore, in our previous work, Xu et al. investigated 382 residents in different parts of China’s Zhejiang province, aiming to identify residents’ views on new energy vehicles and the potential influencing factors [25]. They also extended the original TPB model by considering the external factors, including monetary incentive policy and non-monetary incentive policy. Their research reconfirmed that perceived behavioral control, attitude, and subjective norms were paramount for predicting customers’ purchasing intention. Moreover, the extended TPB model had a better explanation because of the external factors.

2.3. Reviews on the Norm Activation Model

Differing from the TPB, the norm activation model (NAM) highlights the role of moral obligation in motivating individuals’ behaviors [11,26]. The core antecedent variables in NAM are awareness of consequence, ascription of responsibility, and personal norm. Awareness of consequence refers to the fact that an individual has a sense of how her/his pro-environmental action affects others and the whole society. Ascription of responsibility refers to whether s/he will bear the corresponding responsibility. Personal norm refers to a belief of whether to accept a certain behavior morally, and, based on this, to make their own behavior choices [10]. The model illustrates some interrelationships among these variables, e.g., when individuals realize the negative impact of their improper behaviors on others, they spontaneously develop a sense of responsibility. Awareness of consequence and ascription of responsibility help individuals to build a personal norm.

For example, to understand the Germans’ intention for public vehicle usage, Bamberg et al. surveyed two German cities [27]. They validated that the personal norm was an important predictor of public vehicle usage. This result was in line with He and Zhan, who conducted a survey involving 396 Chinese to determine what fosters customers’ intention for electronic vehicle usage [28]. Moreover, they found that the relationship between personal norms and intention to use the electronic vehicle was moderated by external costs, which can be further categorized as perceived complexity and perceived price. Harland et al. found that the variables of the NAM predict people’s intention to close faucet wells [29]. However, not satisfied with such a case-to-case paradigm, researchers turned to explore general factors that influence a broad range of energy-saving behaviors. Werff and Steg identified three types of energy use behaviors based on people’s demand for transport, household, and diet [30]. They found that the NAM predicts different energy behaviors well, which was of great significance for encouraging energy-saving behaviors in a broad sense.

2.4. Combination of the NAM and TPB

The aforementioned research has shed light on the influential factors of people’s pro-environmental behavior, and also provided managerial implications for certain industries. However, some scholars questioned the sufficiency of a single model to understand human behaviors [27,31]. Under the framework of the TPB, the behavior of an individual was considered to be a rational choice made after comparing costs and benefits [10]. Such a theory may overlook the role of altruism in shaping an individual’s behaviors, and that is what the NAM focuses on [9,10]. Taking waste classification as an example, the ever-deteriorating waste problem not only pollutes the environment, but also poses a threat to human health. Therefore, the waste classification can be regarded as a behavior combining personal interests and social benefits. So, further analysis is necessary to be conducted under a comprehensive framework of the NAM and TPB. In addition, a theoretical framework can be extended with additional constructs, making it more appropriate in a particular topic and enhancing explanatory power [32]. For example, Esfandiar et al. integrated a structural model based on the NAM and TPB to explore what affects an individual’s waste binning behavior in the park [33]. They stressed the salient role of personal norms in shaping individuals’ behaviors, and advised that the focus of park services should fall on raising the awareness of visitors’ waste binning behavior and guiding subjective norms. Similarly, Wang et al. combined the NAM and TPB to explore how energy efficiency labels affect Chinese consumers’ purchase intention for energy-saving appliances [34]. They found that Chinese consumers care for energy efficiency labels when purchasing energy-saving appliances.

Some researchers considered the personal norm as the “supplementary predictor” of the three antecedent variables of the TPB. As a result, the so-called extended TPB model failed to explain the formation mechanism of the personal norm [33,35]. Therefore, this study integrated the NAM and TPB in a comprehensive theoretical framework by combining two perspectives of egoism and altruism to investigate residents’ intention for waste classification and their actual behaviors. The personal norm bridges the two theories, which also involve other variables, including perceived behavioral control, subjective norms, awareness of consequence, ascription of responsibility, intention, and behavior. Attitude is not included in the proposed model. Kaiser’s study has suggested the convergence between personal norms and attitudes, that is, for many people, their personal norms and attitudes were often consistent [36]. The notion was also in line with Zhang et al., who considered the similarity between personal norms and attitude [6]. For example, if an individual has developed a personal norm that s/he has the moral obligation to conduct a certain behavior, it also implies her/his attitude towards this behavior.

2.5. Intention–Behavior Gap and Information Publicity Factors

As the research on the micro-individual behavior gradually deepened, scholars also argued that it is not significant to study intention and behavior in isolation [37]. A recurrent problem in human behavior is the fact that good intention often gets lost in the complex circumstances of our daily lives, causing the nonnegligible intention–behavior gap [38,39].

For example, it was found that ethical consumers did not always keep their promises, and there was a clear gap between what they say and what they do when purchasing [40]. Chen et al. pointed out that in China, less than 2% of waste was classified and recycled properly, which was differing from the results of the environmental awareness survey of Chinese urban residents, which showed that more than 90% of citizens orally voted for waste classification [41]. The existing intention–behavior gap means that it is necessary to explore other factors that motivate residents to translate their intention into behavior.

According to the social marketing theory [14] and information–behavior theory [15], information serves as one of the effective factors of personal beliefs, attitudes, and behaviors. Subsequently, information publicity has also been applied to environmental governance practices in various countries and proves that public concern about environmental issues is influenced by access to information because, intuitively, the more information people have about behavior, the more interested they are in it [42]. Similarly, information publicity about waste classification is also important in motivating residents to classify waste correctly. Williams and Taylor argued that providing waste classification information and waste separation skills to residents can significantly motivate them to classify waste in their daily lives [43]. That is easy to understand because the available information, including the standards and systems of waste classification, will make it easy for residents to carry out waste classification [44]. However, Vicente and Reis came to the opposite conclusions [45]. Thus, it is necessary to explore whether the information publicity significantly impacts residents’ waste classification behavior and to discuss the mechanism behind it.

3. Research Model and Hypotheses

The theoretical background and research review involved in the proposed model are described in detail in the previous section. This section will develop hypotheses around the topics of waste classification and the existing literature basis.

Waste classification is a moral activity worth advocating, and refusing to do it will bring many negative effects, such as resource wastes, environmental pollution, and ecological destruction [46]. Once these negative consequences become apparent, they will trigger the sense of responsibility of residents, making them feel that they should be responsible for these problems [2]. Driven by the sense of obligation, it is more likely for residents to form personal norms [27]. On the contrary, if residents have not realized these negative consequences, they are less likely to form ascription of responsibility and personal norms [47]. Waste classification is a selfless action with strong publicity, and residents need to invest time or even material costs into it. Without intrinsic motivation from personal norms, it is difficult for residents to cultivate the intention of engaging in altruistic behavior. Based on the above theoretical analyses, this study proposes the following hypotheses:

Hypotheses 1 (H1).

Awareness of consequence positively affects ascription of responsibility.

Hypotheses 2 (H2).

Ascription of responsibility positively affects personal norms.

Hypotheses 3 (H3).

Awareness of consequence positively affects personal norms.

Hypotheses 4 (H4).

Personal norms positively affect residents’ intention for waste classification.

Subjective norms not only refer to social pressures that individuals perceive in their social lives, but also reflect the attitude that individuals hold towards the pressure [21,48]. Li et al. used family members, social groups, governments, and even religion and customs as references to explore the relationship between subjective norms and intention [46]. On the one hand, the surrounding people may be trustworthy or have leadership rights, so their opinions often affect individuals’ behavior choices [49]. On the other hand, the rules are necessary to maintain the order in social life, so that the behaviors conforming to the subjective norms will be encouraged by society. Therefore, if residents feel that they are facing social pressure and expectation for waste classification, they tend to meet the social expectation. Based on the above theoretical analyses, this study proposes the following hypothesis:

Hypotheses 5 (H5).

Subjective norms positively affect the intention.

Perceived behavioral control can be interpreted as an individual’s judgment of the difficulty in performing a certain action. Oom Do Valle et al. believed that the judgment comes from two aspects: One refers to the innate abilities of individuals, such as intelligence and executive power. The other refers to the resources that individuals have obtained, such as collaboration from others, money, or material support [50,51]. Empirical research has proved the direct influence of perceived behavioral control on intention [46]. Therefore, if an individual feels fewer constraints and difficulties when s/he performs a certain behavior, s/he has a stronger intention to perform it [52]. This can be extended into the research on waste classification. Based on the above theoretical analyses, this study proposes the following hypothesis:

Hypotheses 6 (H6).

Perceived behavioral control positively affects the intention.

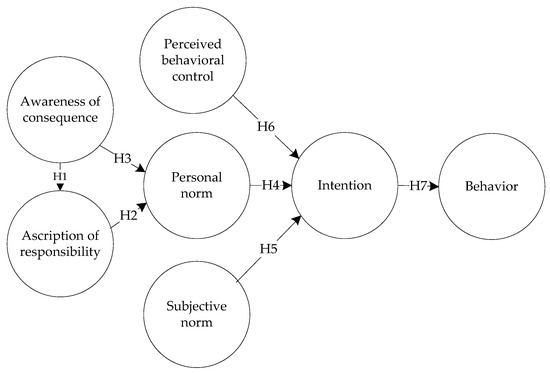

The complexity of waste classification lies in its duality. On the one hand, it has been regarded as an individual’s choice in the private sphere. Therefore, an individual’s intention can be interpreted through psychological factors at the micro-level. On the other hand, waste classification can be considered as a passive individual’s choice, which is restricted by the social environment, regulations, and the opinions of others. In addition, it may produce the “free-rider problem” due to the positive externalities of waste classification [53]. Some individuals are reluctant to perform waste classification, because they believe it will save more time, attention, and money to mix waste directly instead of classifying waste properly. Moreover, once they have realized that they can also enjoy the free-rider benefits brought by others’ participation in waste classification, such as not having to endure the pungent smell of waste accumulation and the improvement of the living environment, they may not act according to how they talk about waste classification. All of the above aspects may prevent residents from converting the intention of waste classification into real behavior. Therefore, this study integrated the NAM-TPB model to explore the residents’ waste classification intention and behavior. Figure 1 shows the NAM-TPB model. Based on the above theoretical analyses, this study proposes the following hypothesis:

Figure 1.

Norm activation model and theory of planned behavior (NAM–TPB) model.

Hypotheses 7 (H7).

Intention positively affects actual behavior, but there is a gap between residents’ intention and their actual behavior.

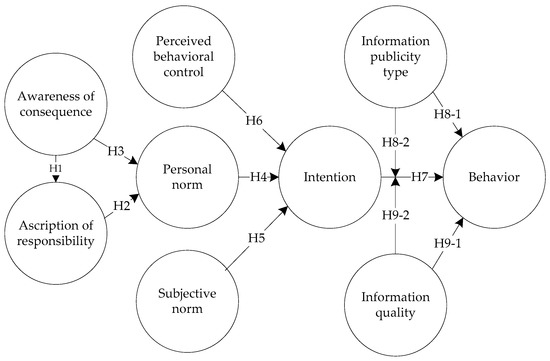

It is worth exploring whether information publicity promotes the transformation of intention into actual behavior. The information publicity includes: Promoting different forms of community campaigns to spread the dangers of waste; making full use of the place with dense flow of people to carry out waste classification propaganda; and carrying out different forms of media publicity through the internet. In a word, through various channels of information publicity, residents will be more likely to engage in waste classification [43]. However, in addition to the information publicity type, the information quality is also important because information may be distorted or contaminated during transmission. When individuals perceive that the provided information is useful, credible, and accurate, they will be more likely to use the information to conduct specific behaviors [54]. Regarding waste classification behavior, when residents perceive the information to be useful, accurate, and understandable, they will be more likely to classify waste proactively. Therefore, this study further extends the NAM–TPB model by exploring the influential mechanism of information publicity on resident’s waste classification behavior. Figure 2 shows the extended NAM–TPB model. Based on the above theoretical analyses, this study proposes the following hypotheses:

Figure 2.

Extended NAM–TPB model.

Hypotheses 8-1 (H8-1).

Information publicity type positively affects behavior.

Hypotheses 8-2 (H8-2).

Information publicity type strengthens the relationship between intention and behavior through its interaction with intention.

Hypotheses 9-1 (H9-1).

Information quality positively affects behavior.

Hypotheses 9-2 (H9-2).

Information quality strengthens the relationship between intention and behavior through its interaction with intention.

4. Research Methodology

4.1. Partial Least Squares Structural Equation Modeling

The proposed NAM–TPB model in this study contains some latent variables, which are difficult to observe directly. Thus, this study applied structural equation modeling (SEM) to assess the scores of latent variables and the correlations between variables [55]. The covariance-based (CB-SEM) and partial least squares structural equation modeling (PLS-SEM) are the two methods in SEM. Particularly, PLS-SEM has the following advantages: (1) PLS is more suitable to estimate survey data that do not meet the multivariate normal distribution requirement [56]; (2) PLS is more suitable to estimate on a small sample size. Therefore, this study preferred the PLS-SEM method and applied SmartPLS 2.0 to validate the proposed hypotheses. In addition, the latent variables can be measured with multiple measurement items according to Fornell and Larcker [57].

4.2. Measurement Development

Some measurement items were adapted to fit the topic of this study, which showed that this study was not isolated, and the scientific integrity and accuracy of the experiment were guaranteed. Following the works of Wang et al. and Xu et al., four TPB constructs, including perceived behavioral control, personal norm, subjective norm, and intention, were measured to illustrate the determinants of residents’ intention for waste classification [3,11]. Two NAM constructs, including awareness of consequence and ascription of responsibility, were measured using the items from Ajzen, Shin and Hancer, and Stoeva and Alriksson to highlight the role of personal norms [8,18,49]. Five items were adopted from Xu et al. to measure waste classification behavior by asking respondents how often they classified waste in their daily lives [3]. Three items were used to measure information quality, and they were developed based on the works of Mun et al. [54]. Information publicity type was measured with another three items based on the works of Mickael [58] and Wang et al. [44].

All of the items were scored on a seven-point Likert scale. Notably, before conducting a formal survey, a pretest was randomly conducted on 20 applicants. Several experts whose mother tongue was Chinese or English were invited to translate the questionnaire, which was then compared and improved. The process helps to avoid language misunderstandings due to cultural differences. The back-translation technique and pretest ensured the comprehensibility of the questionnaire and the data quality of the questionnaire. The final version of the questionnaire was shown in the Table A1 in the Appendix A.

4.3. Data Collection and Samples

The questionnaire survey in this study was conducted through the Internet. Such web-based surveys are prevailing in marketing research because they are superior to face-to-face surveys in several aspects during the actual operation [59]: (1) They break the geographical limitation of face-to-face questionnaire distribution, and make the questionnaire widespread in order to reach more groups or individuals; (2) they save the time and costs of research to a large extent [60,61]. Therefore, this study conducted a questionnaire survey through a professional survey platform (www.wjx.cn), which is the largest online survey portal with more than one million active users, and is also the most popular academic survey research tool in China [25]. The platform has the distinct advantage of being fast, easy to use, and low-cost, and has been widely used by a large number of enterprises and individuals. By means of this platform, some scholars have conducted various academic researches on topics including Mobile Government continence usage and residents’ green purchase intention [34,62]. Through a random sampling program, a sample of 500 persons was randomly drawn from the population who have registered on this platform, and they would receive an e-mail that contained the link to the survey website and a brief introduction of the survey.

The self-selection bias is a common problem in questionnaire surveys, which refers to the fact that the research subjects are inclined to give answers fitting the moral expectations of society rather than revealing their true feelings and thoughts [44,63]. Therefore, to minimize the potential bias, some measures were taken in this study according to the practice of Chen and Chang, and Wang et al. [34,64]. Firstly, the questionnaire survey was conducted anonymously and the respondents were told that they would not be identified. Secondly, respondents were told that researchers were only able to access the information they presented in the questionnaire, and their responses were confidential and only used for research purposes. Finally, the respondents were asked to fill in the questionnaire truthfully.

To ensure the quality of the answers collected, data cleaning is necessary. For incomplete answers, the answers that took less than one minute to fill in and the answers that were given polarized ratings towards synonymous questions were deleted. Finally, a total of 349 questionnaires were valid. According to the returned questionnaire, the obtained answers were encoded and summarized in the data needed for the experiment. The first part included the basic personal information of the respondents, such as gender, age, educational level, occupation, monthly household income, and residential location, as shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

Demographic characteristics of respondents.

5. Result Analysis

5.1. Descriptive Analysis

In terms of population distribution, the proportion of urban and rural population in this study was 54.44%/45.56%, which was not much different from that of China’s latest census (49.68%/50.32%). The male-to-female ratio of the respondents involved in this study was 50.51%/49.49%, which was roughly consistent with that of the census (51.2%/48.8%). More than 60% of the respondents are aged between 19 and 45. More than 50% of respondents had a bachelor degree or above in this study. There were 29.51% of respondents who earned a yearly income below the level of 120,000 RMB, while only 12.04% of the residents earned more than 240,000 RMB per year. In general, this survey comprised a wide variety of individuals in China, and the demographic characteristics of the sample were basically consistent with the Chinese resident demographic profile [65].

5.2. Common Method Bias

Common method bias (CMB) remains a major and widespread problem in studies of psychology and behavior. It refers to a systematic error caused by the same data source, measurement environment, and research background [66]. Thus, inspired by the practices in previous research, this study employed Harman’s single-factor test to assess the severity of the CMB [63]. If a single construct accounts for more than 50% of the variance, it implies that the CMB may affect experimental results. In this study, the combined nine constructs accounted for 73.599% of the total variance, while the variance of single constructs varied from 3.248% to 14.633%. Thus, the effect of the CMB could be excluded in this study.

5.3. Reliability and Validity

This study used SmartPLS 2.0 for confirmatory factor analysis (CFA). Cronbach’s α, composite reliability (CR), average variance extracted (AVE), and factor loading [67] were used for evaluating the reliability and validity of the measurement model. As shown in Table 2, Cronbach’s α and CR values were all above the threshold of 0.7, which confirmed the reliability of this questionnaire. AVE values > 0.5 indicated that the corresponding construct had good convergent validity. Because the minimum AVE value in this study was 0.541, the convergent validity was acceptable. Factor loading also reflected the convergent validity; in general, a factor loading > 0.7 indicated that the factor was significantly loaded on the related construct. As shown in Table 3, although the factor loadings of PBC5 and BEH5 were 0.650 and 0.675, respectively, which were lower than 0.7, they were also acceptable in this study according to Yang et al., who suggested that some factor loadings of items whose values were slightly lower than 0.7 could also be accepted, especially when the items are indispensable to be included in the model, though the more stringent criterion is 0.7 [62]. The discriminant validity was examined using two methods. First, the square root of the AVE of each construct was compared with the correlation coefficient between it and other constructs, showing that the former had a higher value than the latter, as shown in the top half of Table 2. Second, the internal factor loadings of each construct were all higher than the cross-loadings between them and other constructs, as shown in Table 3. These two methods both proved that the items in this questionnaire could be distinguished from each other.

Table 2.

Means and correlation coefficients for key indicators.

Table 3.

The results of confirmatory factor analysis.

5.4. Hypothesis Analysis

After the reliability and validity analyses of the measurement model were conducted, the proposed structural model was evaluated with SEM. The fitting indices and testing of hypotheses are shown in Table 4.

Table 4.

Fitting indices and hypothesis testing.

The R2 value is an indicator of overall predictive strength of the model, which is a common indicator and has been widely used in the empirical analysis of structural equation models [55,62,68]; therefore, this study evaluated the R2 values of constructs. Firstly, for the NAM–TPB model, all of the R2 values of endogenous latent variables were above 0.19, which suggested an acceptable goodness of fit for partial least square (PLS) estimation and showed that the NAM was soundly integrated with the TPB in this study. However, the results of PLS estimation showed that R2 for waste classification behavior was 0.141, which indicated that intention alone was inadequate to explain the variance in waste classification behavior. In addition, according to Table 2, the mean value of the residents’ waste classification intention was 5.603, while that of the actual behavior was only 4.159. A difference in the mean value showed the intention–behavior gap on Chinese residents’ waste classification even though the positive relationship passed the statistic test at the p < 0.001 level. Respondents with a high intention of waste classification did not necessarily translate their intention into actual behavior, which was also consistent with Echegaray and Hansstein [2]; thus, H7 was verified.

For the NAM–TPB model, Table 4 showed that personal norm was significantly positively related to residents’ waste classification intention (Path coefficient = 0.498, p < 0.001). Thus, H4 was supported in this study, and was also in line with the results of Rezaei et al. [10]. In addition, this study explained how personal norms were activated. Table 4 showed that both ascription of responsibility and awareness of consequence significantly affected personal norms (Path coefficient = 0.507, p < 0.001; Path coefficient = 0.233, p < 0.001); thus, H2 and H3 were both verified. The results were consistent with those of Schwartz [11] and Wang et al. [26] (pp. 221–279). Next, awareness of consequence was closely related to ascription of responsibility (Path coefficient = 0.631, p < 0.001); thus, H1 was supported, and was consistent with the results of prior research [1,46]. In addition, the findings of this study illustrated that perceived behavioral control exerted a significant effect on residents’ waste classification intention, thus supporting H6 (Path coefficient = 0.280, p < 0.001). The path from subjective norm to intention is also significant in this study (Path coefficient = 0.126, p < 0.001), even though the coefficient is relatively weak. Analogous results were also reported by Bratt [69].

Secondly, the factors of information publicity type and information quality were tested in the extended NAM–TPB model 1, wherein the external information factors were included. The experimental procedure was the same as above. As shown in Table 4, for the extended NAM–TPB model 1, the R2 value for behavior increased to 0.220, which meant an improvement of the model’s interpretation ability. Being similar to the results of the NAM–TPB model, H1–H7 were all supported in the extended NAM–TPB model 1. However, from the results of PLS estimation, the path coefficient of information publicity type towards behavior was not as significant as information quality; thus, H8-1 was rejected and H9-1 was supported. Furthermore, the extended NAM–TPB model 2 was evaluated, which involved external information factors and their interaction with intention [70]. Additionally, shown in Table 4, for the extended NAM–TPB model 2, the R2 value for behavior was not significantly increased after incorporating the interaction between external information factors and intention. Neither information publicity type nor information quality was a moderating variable that affects the direction or intensity of the relationship between an individual’s intention and actual behavior; thus, H8-2 and H9-2 were both rejected.

6. Discussion

This study integrated the NAM and TPB into a comprehensive theoretical framework. Similar combination work has seldom been conducted to explore individuals’ waste classification intentions and behaviors on the topic of pro-environmental behaviors. Through the empirical analysis of samples from China, this study not only contributed to the theoretical development of pro-environmental behaviors, but also helped Chinese policymakers in promoting and planning waste classification.

6.1. Theoretical Implications

From the empirical analysis, the TPB and NAM were well integrated to explain an individual’s waste classification intention because all of the constructs were found to be significant. More importantly, personal norm was considered to be a major factor in predicting the waste classification intention. In addition, this study revealed the intention–behavior gap on waste classification behavior, and found that delivering well-qualified information was more important than diversified information channels.

Personal norm, which was activated by awareness of consequence and ascription of responsibility, served as a major contributor to an individual’s waste classification intention in this study. When an individual realizes the consequences of the waste problem and the social responsibility of a citizen, a strong sense of moral obligation would be aroused, thus making him/her feel that waste classification is the “right thing to do”. The relationship between the intention and subjective norm, however, is considered attenuated even though there exists a statistically significant relationship [71]. Bratt also pointed out the weaker importance of the subjective norm because its internalization takes time to occur [69]. Perceived behavioral control was the second significant determinant of intention, and was measured by the perceived convenience of waste classification. If individuals feel that waste classification costs too much time and energy, their participation intention would be weakened. On the contrary, their participation intention would be enhanced if they feel that convenient facilities for waste classification were provided. The finding supported that perceived behavioral control was a salient factor in shaping residents’ pro-environmental behavior [68].

Although the respondents had undoubtedly indicated high intention for waste classification, a large number of them fail to perform it in reality. This inspired the current study to investigate the reason for the intention–behavior gap by introducing information publicity types and information quality. However, information quality proved to have a significant direct effect on unplanned waste classification behavior, while information publicity type did not. A similar conclusion was drawn by Bortoleto et al., who argued that people value the information quality more than how information is publicized [72]. If residents feel that the information about waste classification policy is vague and incomplete, they may question the necessity of the mandatory waste classification in their residential locations. Neither information publicity type nor information quality has a significant moderating effect on intention–behavior gap, indicating that both of them have a very limited effect on people who already have waste classification intentions.

6.2. Research Implications

The increasing amount of waste and inadequate waste management practices make it urgent for policymakers and academics to deal with waste problems. Therefore, it is crucial to identify what motivates/hinders residents’ involvement in waste classification, especially in developing countries such as China, where the ever-deteriorating waste problem has brought about great challenges for sustainable development. This study offers some implications to motivate residents to participate in waste classification in their daily lives.

Firstly, governments should understand that residents who have a moral obligation feel more responsible for joining in waste classification [33]. Therefore, governments need to impose moralistic education measures on residents. Environmental problems are closely related to everyone. The government should positively disclose the real environmental problems in the society, especially the waste pollution, which fiercely affects the operation of municipals. Proper disclosure can make people realize the serious consequences of not classifying waste, further internalizing the awareness of consequence into a sense of environmental responsibility. In addition, governments should encourage people to carry out waste classification in communities to achieve a refined management level. It is necessary to ensure the supply of dustbins in residential buildings and along the curbsides.

Secondly, governments should work with social organizations to promote and publicize the waste classification policies and enhance residents’ understanding of them. Delivering high-quality information could directly encourage residents’ behavior, especially aiming at those who have no sense of waste classification. It is worth noting that some residents participate in waste classification not because of their planning intentions, but because they are affected by this kind of external information. Hence, governments can design user manuals or community posters with specialized knowledge of waste classification to create an atmosphere for the public to participate in waste classification, and also to deepen residents’ understanding of waste classification regulations. In addition, with the rapid development of communication technology, the way people get information is no longer limited to radio and television. Information about national or city-based waste policy and the urgency of waste classification can be propagated to residents through diversified media and communication channels. Offline publicity and communication are also necessary; for example, waste classification information publicity can be conducted through public service advertisements, public welfare activities, and community lectures.

7. Conclusions

This study explored the factors influencing residents’ waste classification intentions and the relationship between intention and behavior using an extended NAM–TPB model. Evidence from an online survey in China confirmed the potential for an intention–behavior gap in residents’ waste classification. The empirical results considered personal norm as a major predictor of residents’ waste classification intention, and information quality significantly affected behavior. Neither information publicity type nor information quality strengthened the relationship between waste classification intention and waste classification behavior through their interactions with intention. As conclusions, this study suggested that the government enhance promotion and publicity of the waste classification policy, and emphasized the salient role of moralistic education measures in guiding residents’ pro-environmental behavior.

Although this study took the waste classification behavior of Chinese residents as the research object, the proposed theoretical framework can be used to analyze other pro-environmental behaviors because human behavior always embodies a combination of egoism and altruism. It is necessary to understand what motivates/hinders the public to conduct a certain behavior from the perspective of rational choice and moral obligation, so that the policies can be better designed by policymakers to regulate human behavior and maintain the public order. In addition, the study also provided some methodological guidance for policymakers to investigate public acceptance of a certain policy. Furthermore, waste management is a major issue that is confronted by worldwide governments, not only in China. The findings in the study are also important for worldwide policymakers to improve global waste management.

The inadequacy of this study should also be recognized. First, as a policy tool of environmental regulation, the role of economic incentives was ignored in this study, but was only introduced in the literature review. Second, a self-reported survey method was adopted in this study, which largely depends on the authenticity of the subjects’ reports, and also requires the subjects to be able and willing to provide relevant information. This made the information acquisition process difficult. In addition, it is noteworthy that a potential upwards bias of the self-reported method may lead to the heterogeneity of results regarding different research objectives [73]. Future studies should try to overcome these two shortcomings. Third, although this study covered both urban and rural populations in China, part of the rural population has actually lived in the city for a long time due to the cross-regional migration of the population. Future studies should consider residents’ locations to further analyze and distinguish the potential differences between urban and rural residents’ attitudes towards waste classification.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, L.Z. and Q.H.; Data Curation, Q.H.; Formal Analysis, L.Z. and Q.H.; Funding Acquisition, S.Z. and W.Z.; Investigation, Q.H.; Methodology, L.Z. and Q.H.; Project Administration, L.Z., S.Z. and W.Z.; Supervision, S.Z. and W.Z.; Writing-Original Draft, L.Z. and Q.H.; Writing-Review & Editing, S.Z. and W.Z. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by National Natural Science Foundation of China (No. 51975512, No.51875503) and the Zhejiang Natural Science Foundation of China (No. LZ20E050001).

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare that there is no conflict of interests regarding the publication of this article.

Ethical Standard

The authors state that this research complies with ethical standards. This research does not involve either human participants or animals.

Appendix A

Table A1.

Questionnaire.

Table A1.

Questionnaire.

| Awareness of Consequence (AC): | |

| AC1 | Incorrect waste classification encroaches on land. |

| AC2 | Incorrect waste classification causes severe ecological damage problems. |

| AC3 | Incorrect waste classification causes resource wasting. |

| Ascription of responsibility (AR): | |

| AR1 | I feel jointly responsible for the ecological damage due to incorrect waste classification. |

| AR2 | I feel jointly responsible for the resource wasting due to incorrect waste classification. |

| AR3 | I feel jointly responsible for the encroachments on land due to incorrect waste classification. |

| Personal norm (PN): | |

| PN1 | I have the obligation to participate in waste classification. |

| PN2 | Participating in waste classification is consistent with my moral principles. |

| PN3 | I would feel guilty if I do not participate in waste classification in daily life. |

| Subjective norm (SN): | |

| SN1 | If my family member encourages me to participate in waste classification, I would follow. |

| SN2 | If neighbors that I know participate in waste classification, I would follow. |

| SN3 | If the government encourage me to participate in waste classification, I would follow. |

| Perceived behavioral control (PBC): | |

| PBC1 | It will not take me too much time to figure out how to classify waste correctly. |

| PBC2 | If I am willing, I have the confidence to classify waste correctly in daily life. |

| PBC3 | I have sufficient knowledge to deal with the problem of waste classification. |

| PBC4 | Whether or not to do household waste classification is completely up to me. |

| PBC5 | It will not take long to find curbside facilities for waste classification in my location. |

| Intention (INT): | |

| INT1 | In the future, I will expend effort in waste classification. |

| INT2 | In the future, I will share my experience in dealing with wastes with surrounding people. |

| INT3 | If possible, I will teach my next generations to sort wastes. |

| INT4 | If possible, I will help my previous generations to sort wastes. |

| Behavior (BEH): | |

| BEH1 | How often do you sort plastic products at home or anywhere else? |

| BEH2 | How often do you sort metal wastes at home or anywhere else? |

| BEH3 | How often do you sort kitchen wastes at home or anywhere else? |

| BEH4 | How often do you use disposal items (like packing boxes for take-out food)? |

| BEH5 | How often do you sort hazardous wastes (like batteries) at home or anywhere else? |

| Information quality (IQ): | |

| IQ1 | The information I received about waste classification is complete and comprehensive. |

| IQ2 | The information I received about waste classification is reliable and accurate. |

| IQ3 | The information I received about waste classification is understandable and executable. |

| Information publicity type (IPT): | |

| IPT1 | Local satellite TV programs often report waste classification in my residential location. |

| IPT2 | There is a management system for waste classification in my residential location. |

| IPT3 | I can see public announcements for waste classification in my residential location. |

Notes: For items of the BEH construct, the answers were labeled with end-points of 1 = “never”, 4 = “sometimes”, and 7 = “always”; for others, the answers were labeled with end-points of 1 = “totally disagree”, 4 = “neutral”, and 7 = “totally agree”.

References

- Zhang, D.Q.; Tan, S.K.; Gersberg, R.M. Municipal solid wastes management in China: Status, problems and challenges. J. Environ. Manag. 2010, 91, 1623–1633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Echegaray, F.; Hansstein, F.V. Assessing the intention-behavior gap in electronic waste recycling: The case of Brazil. J. Clean. Prod. 2016, 142, 180–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, L.; Ling, M.L.; Lu, J.; Shen, M. External influences on forming residents’ waste separation behavior: Evidence from households in Hangzhou, China. Habitat Int. 2017, 63, 21–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, D.; Wang, L.; Wang, Z. What affects individual energy conservation behavior: Personal habits, external conditions or values? An empirical study based on a survey of college students. Energy Policy 2019, 128, 150–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, S.R.; Greaves, M.; Chen, J.; Grady, S.C. Green buildings need green occupants: A research framework through the lens of the theory of planned behaviour. Archit. Sci. Rev. 2017, 60, 5–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, B.; Lai, K.H.; Wang, Z.H. From intention to action: Do personal attitudes, facilities accessibility, and government stimulus matter for household waste sorting? J. Environ. Manag. 2019, 233, 447–458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Papaoikonomou, K.; Latinopoulos, D.; Emmanouil, C.; Kungolos, A. A Survey on factors influencing recycling behavior for waste of electrical and electronic equipment in the municipality of Volos, Greece. Environ. Process. 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ajzen, I. The theory of planned behavior. Organ. Behav. Hum. Decis. Process. 1991, 50, 179–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaiser, F.G.; Ranney, M.; Hartig, T.; Bowler, P.A. Ecological behaviour, environmental attitude, and feelings of responsibility for the environment. Eur. Psychol. 1999, 4, 59–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rezaei, R.; Safa, L.; Damalas, C.A.; Ganjkhanloo, M.M. Drivers of farmers’ intention to use integrated pest management: Integrating theory of planned behavior and norm activation model. J. Environ. Manag. 2019, 236, 328–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, B.; Wang, X.M.; Guo, D.X.; Zhang, B.; Wang, Z.H. Analysis of factors influencing residents’ habitual energy-saving behaviour based on NAM and TPB models: Egoism or altruism? Energy Policy 2018, 116, 68–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Unsworth, K.L.; Dmitrieva, A.; Adriasola, E. Changing behaviour: Increasing the effectiveness of workplace interventions in creating pro-environmental behaviour change. J. Organ. Behav. 2013, 34, 211–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hage, O.; Sandberg, K.; Söderholm, P.; Berglund, C. Household plastic waste collection in Swedish municipalities: A spatial-econometric approach. In Proceedings of the 2008 EAERE Annual Conference on Sustainable Households: Attitudes, Resources and Policy, Gothenburg, Sweden, 25–28 June 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Bates, D.; Kotler, P.; Roberto, E.L.; Fine, S.H. Social marketing: Strategies for changing public behavior. J. Mark. 1991, 55, 108–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mckechnie, L.E.F.; Pettigrew, K.E.; Joyce, S.L. The origins and contextual use of theory in human information behavior research. New Rev. Inf. Behav. Res. 2001, 2, 47–63. [Google Scholar]

- MEEC (Ministry of Ecology and Environment of China). Information on Solid Waste Released in Large and Medium-Sized Cities Across the Country. Available online: http://trhj.mee.gov.cn/gtfwhjgl/zhgl/201604/P020160424386477560289.pdf. (accessed on 1 January 2015).

- MEEC (Ministry of Ecology and Environment of China). Information on Solid Waste Released in Large and Medium-Sized Cities Across the Country. Available online: http://www.mee.gov.cn/hjzl/sthjzk/gtfwwrfz/201901/P020190102329655586300.pdf. (accessed on 31 December 2018).

- Stoeva, K.; Alriksson, S. Influence of recycling programmes on waste separation behaviour. Waste Manag. 2017, 68, 732–741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vehlow, J. Municipal solid waste management in Germany. Waste Manag. 1996, 16, 142–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MOHURD (Ministry of Housing and Urban-Rural Development of the People’s Republic of China). Notification about Municipal Solid Wastes Separated-Collection Pilot Cities. Available online: http://www.mohurd.gov.cn/ (accessed on 1 June 2000).

- Fishbein, M.; Ajzen, I. Belief, Attitude, Intention, and Behavior: An Introduction to Theory and Research; Addison-Wesley: Boston, MA, USA, 1975. [Google Scholar]

- Speris, D.; Tucker, P. A profile of recyclers making special trips to recycle. J. Environ. Manag. 2001, 62, 201–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borthakur, A.; Govind, M. Public understandings of e-waste and its disposal in urban India: From a review towards a conceptual framework. J. Clean. Prod. 2018, 172, 1053–1066. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zahedi, S.; Batista-Foguet, J.M.; van Wunnik, L. Exploring the public’s willingness to reduce air pollution and greenhouse gas emissions from private road transport in Catalonia. Sci. Total Environ. 2019, 646, 850–861. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Y.L.; Zhang, W.Y.; Bao, H.J.; Zhang, S.; Xiang, Y. A SEM-Neural Network approach to predict customers’ intention to purchase battery electric vehicles in China’s Zhejiang province. Sustainability 2019, 11, 3164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwartz, S.H. Normative influences on altruism. In Advances in Experimental Social Psychology; Berkowitz, L., Ed.; Academic Press: New York, NY, USA, 1977; pp. 221–279. [Google Scholar]

- Bamberg, S.; Hunecke, M.; Blöbaum, A. Social context, personal norms and the use of public transportation: Two field studies. J. Environ. Psychol. 2007, 27, 190–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, X.H.; Zhan, W.J. How to activate moral norm to adopt electric vehicles in China? An empirical study based on extended norm activation theory. J. Clean. Prod. 2017, 172, 3546–3556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harland, P.; Staats, H.; Wilke, H.A.M. Situational and personality factors as direct or personal norm mediated predictors of pro-environmental behavior: Questions derived from norm-activation theory. Basic Appl. Soc. Psychol. 2007, 29, 323–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Werff, E.V.D.; Steg, L. One model to predict them all: Predicting energy behaviours with the norm activation model. Energy Res. Soc. Sci. 2015, 6, 8–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steg, E.; Bolderdijk, J.; Keizer, K.; Perlaviciute, G. An integrated framework for encouraging pro-environmental behaviour. J. Environ. Psychol. 2014, 38, 104–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, H.; Hsu, L.; Sheu, C. Application of the theory of planned behavior to green hotel choice: Testing the effect of environmentally friendly activities. Tour. Manag. 2010, 31, 325–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Esfandiar, K.; Dowling, R.; Pearce, J.; Goh, E. Personal norms and the adoption of pro-environmental binning behaviour in national parks: An integrated structural model approach. J. Sustain. Tour. 2019, 28, 10–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.H.; Sun, Q.Y.; Wang, B.; Zhang, B. Purchasing intentions of Chinese consumers on energy-efficient appliances: Is the energy efficiency label effective? J. Clean. Prod. 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaiser, F.G.; Scheuthle, H. Two challenges to a moral extension of the theory of planned behavior: Moral norms and just world beliefs in conservationism. Personal. Individ. Differ. 2003, 35, 1033–1048. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaiser, F.G. A moral extension of the theory of planned behavior: Norms and anticipated feelings of regret in conservationism. Personal. Individ. Differ. 2006, 41, 71–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davies, J.; Foxall, G.R.; Pallister, J. Beyond the intention-behaviour mythology: An integrated model of recycling. Mark. Theory 2002, 2, 29–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rhodes, R.E.; Dickau, L. Moderators of the intention-behaviour relationship in the physical activity domain: A systematic review. Br. J. Sports Med. 2013, 47, 215–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- MacCann, C.; Todd, J.; Mullan, B.A.; Roberts, R.D. Can personality bridge the intention-behavior gap to predict who will exercise? Am. J. Health Behav. 2015, 39, 140–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carrigan, M.; Atalla, A. The myth of the ethical consumer: Do ethics matter in purchase behaviour? J. Consum. Mark. 2001, 18, 560–577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, S.J.; Li, R.C.; Ma, Y.B. Paradox between willingness and behavior: Classification mechanism of urban residents on household waste. Chin. Popul. Resour. Environ. 2015, 25, 168–176. [Google Scholar]

- Huang, R.B.; Chen, D.P. Does environmental information disclosure benefit waste discharge reduction? Evidence from China. J. Bus. Ethics 2015, 129, 535–552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, I.D.; Taylor, C. Maximizing household waste recycling at civic amenity sites in Lancashire, England. Waste Manag. 2004, 24, 861–874. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.H.; Guo, D.X.; Wang, X.M.; Zhang, B.; Wang, B. How does information publicity influence residents’ behaviour intentions around e-waste recycling? Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2018, 133, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vicente, P.; Reis, E. Factors influencing households’ participation in recycling. Waste Manag. Res. 2008, 26, 140–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Zuo, J.; Cai, H.; Zillante, G. Construction wastes reduction behavior of contractor employees: An extended theory of planned behavior model approach. J. Clean. Prod. 2018, 172, 1399–1408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saphores, J.D.M.; Ogunseitan, O.A.; Shapiro, A.A. Willingness to engage in a pro-environmental behavior: An analysis of e-waste recycling based on a national survey of US households. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2012, 60, 49–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pakpour, A.H.; Hidarnia, A.; Hajizadeh, E.; Plotnikoff, R.C. Action and coping planning with regard to dental brushing among Iranian adolescents. Psychol. Health Med. 2012, 17, 176–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shin, Y.H.; Hancer, M. The role of attitude, subjective norm, perceived behavioral control, and moral norm in the intention to purchase local food products. J. Foodserv. Bus. Res. 2016, 19, 338–351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oom Do Valle, P.; Rebelo, E.; Reis, E.; Menezes, J. Combining behavioural theories to predict recycling involvement. Environ. Behav. 2005, 37, 364–396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, M.F. Extending the theory of planned behavior model to explain people’s energy savings and carbon reduction behavioral intentions to mitigate climate change in Taiwan: Moral obligation matters. J. Clean. Prod. 2016, 112, 1746–1753. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, H.H.; Gao, Q.; Wu, Y.P.; Wang, Y.; Zhu, X.D. What affects green consumer behavior in China? A case study from Qingdao. J. Clean. Prod. 2014, 63, 143–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D’Amato, A.; Giaccherini, M.; Zoli, M. The role of information sources and providers in shaping green behaviors: Evidence from Europe. Ecol. Econ. 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mun, Y.Y.; Yoon, J.J.; Davis, J.M.; Lee, T. Untangling the antecedents of initial trust in Web-based health information: The roles of arguments quality, source expertise, and user perceptions of information quality and risk. Decis. Support. Syst. 2013, 55, 284–295. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, L.B.; Fan, Y.L.; Zhang, W.Y.; Zhang, S. Extending the theory of planned behavior to explain the effects of cognitive factors across different kinds of green products. Sustainability 2019, 11, 4222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, W.; Xiao, W.; Wang, X. Passenger satisfaction evaluation model for urban rail transit: A structural equation modeling based on partial least squares. Transp. Policy 2016, 46, 20–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fornell, C.; Larcker, D.F. Evaluating structural equation models with unobservable variables and measurement error. J. Mark. Res. 1981, 18, 39–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mickael, D. The comparative effectiveness of persuasion, commitment and leader block strategies in motivating sorting. Waste Manag. 2014, 34, 730–737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schlegelmilch, B.B.; Bohlen, G.M.; Diamantopoulos, A. The link between green purchasing decisions and measures of environmental consciousness. Eur. J. Mark. 1996, 30, 35–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grant, D.B.; Teller, C.; Teller, W. “Hidden” opportunities and benefits in using web-based business-to-business surveys. Int. J. Mark. Res. 2005, 47, 641–666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wright, B.; Schwager, P.H. Online survey research: Can response factors be improved? J. Internet Commer. 2008, 7, 253–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, S.Q.; Jiang, H.; Yao, J.R.; Chen, Y.G.; Wei, J. Perceived values on mobile GMS continuance: A perspective from perceived integration and interactivity. Comput. Human Behav. 2018, 89, 16–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, Y.W.; Hsu, P.Y.; Lan, Y.C. Cooperation and competition between online travel agencies and hotels. Tour. Manag. 2018, 71, 187–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.S.; Chang, C.H. The determinants of green product development performance: Green dynamic capabilities, green transformational leadership, and green creativity. J. Bus. Ethics 2013, 116, 107–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- NBSC (National Bureau of Statistics of China). Urban Statistical Yearbook of China 2016; China Statistics Press: Beijing, China, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Podsakoff, P.M.; Mackenzire, S.B.; Lee, J.Y.; Podsakoff, N.P. Common method biases in behavioral research: A critical review of the literature and recommended remedies. J. Appl. Psychol. 2003, 88, 879–903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, J.F.; Anderson, R.E.; Tatham, R.L.; Black, W.C. Multivariate Data Analysis, 5th ed.; Prentice-Hall: Upper Saddle River, NJ, USA, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Vermeir, I.; Verbeke, W. Sustainable food consumption among young adults in Belgium: Theory of planned behaviour and the role of confidence and values. Ecol. Econ. 2008, 64, 542–553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bratt, C. The impact of norms and assumed consequences on recycling behavior. Environ. Behav. 1999, 31, 630–656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chin, W.W.; Marcolin, B.L.; Newsted, P.R. A partial least squares latent variable modeling approach for measuring interaction effects: Results from a Monte Carlo simulation study and an electronic-mail emotion/adoption study. Inf. Syst. Res. 2003, 14, 189–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Botetzagias, I.; Dima, A.F.; Malesios, C. Extending the theory of planned behavior in the context of recycling: The role of moral norms and of demographic predictors. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2015, 95, 58–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bortoleto, A.P.; Kurisu, K.H.; Hanaki, K. Model development for household waste prevention behaviour. Waste Manag. 2012, 32, 2195–2207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chan, L.; Bishop, B. A moral basis for recycling: Extending the theory of planned behavior. J. Environ. Psychol. 2013, 36, 96–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).