This research is based on the premise of heroism as a myth that can foster the creative talent of women leaders, which contributes positively to sustainable training in leadership. It draws on the perspective of analytical psychology developed by C. G. Jung. This approach to leadership—in our opinion, as revealing as it is scarcely documented—can complement and broaden the scope of the main trends in the study of leaders and followers, as well as the studies on creativity in women and sustainable education. As described in the following sections, most approaches to leadership have laid the emphasis—unilaterally—on the individual or situational variables of this process. Only recently have proposals emerged that integrate and transcend both types of variables—and in this respect, they opt for a style of leadership that also points to sustainable practices in human resource management.

In this paper, we argue in favor of the innovative character that Jungian analytical psychology contributes to the analysis of leadership. Specifically, elements of the collective unconscious (heroism), the individual unconscious (psychological typology), and consciousness (self-descriptions, values) are considered in conjunction. We draw on this line of thought to show how our approach can help in a sustainable way to enhance the talent of emerging women leaders with regard to their creativity.

Based on these ideas, the arguments that underpin this research are presented below. First, the main characteristics of the evolution of leadership studies are discussed: From a leader-centered vision to the conception of leadership as a process in which both leaders and followers are the main actors. This is followed by a description of the conception of heroism as a perspective that articulates and deepens the personal, interpersonal, and collective aspects of leadership. This introduction then ends with a line of reasoning that defends the role played by heroism in the sustainable promotion of creativity in women as emerging leaders.

1.1. Leadership, from Charisma to Prototypicality

Before presenting the differential contribution of analytical psychology in the study of the promotion of creativity in emerging women leaders, it is necessary to delimit the concept of leadership, briefly pointing out the scope and limits of the main approaches in the psychosocial study of leadership, and attending to their possibilities regarding sustainable organizational practices.

Leadership is a basic psychosocial process that, expressed simply, enables others to do something. For Hogg [

1] (p. 1166): “Leaders are agents of influence. When people are influenced it is often because of effective leadership. Influence and leadership are thus tightly intertwined”. Thus, research on leadership implies, among other things, uncovering the evidence about what mobilizes individuals. In this respect, three trends in leadership research can be distinguished [

2]: Great men and the cult of personality; the context and contingency/transaction/transformation; and social identity/social categorization. By and large, the two first perspectives have gradually calibrated the explanatory potential of the individual and the social in leadership, i.e., with the goal of identifying the most decisive factor in the leadership process. With the perspective related to the social identity/social categorization, both factors are integrated, which has opened new ways for equally integrative explanations—as well as alternatives—to these three perspectives in leadership research.

Great men and the cult of personality. The main attribute of this perspective is charisma, with Weber [

3] (p. 245) being considered the classic reference: “The natural leaders in distress have been holders of specific gifts of the body and spirit; and these gifts have been believed to be supernatural, not accessible to everybody”. Therefore, this conception of leadership assumes that it is those special attributes of leaders (generally men) that result in them being followed by the masses. Over time, this perspective, with its focus on charisma, has included research that in one way or another recurs to personality as a fundamental explanation of the whys and wherefores of leadership [

4,

5,

6,

7]. Specifically, the personality of leaders has been described as characterized predominantly by extraversion, conscientiousness, and openness to experience [

5].

This assumption that leadership is a phenomenon that mainly depends on the leader’s personality has been the subject of criticism, the most common argument being the scant or zero importance given to social and/or historical contexts. By way of an example, it is enough to imagine what would happen if any leader from other time was now at the head of a community. This criticism does not ignore the impact on a group made by the personal characteristics of the person who leads it, as in the case, for example, of the harm done by seductive narcissistic leaders to their followers [

8]. In their most negative version, seductive narcissists present themselves as saviors who can make up for the deficiencies of the others, who throw in their support out of apathy and inactivity.

The context: Contingency, transaction, transformation. In the pioneering studies on leadership styles led by K. Lewin [

9,

10], it was demonstrated empirically that the same group of children behaved differently under autocratic, democratic, and laissez-faire leaders. This malleability in the face of changing circumstances laid the foundations of an approach to leadership studies that prioritizes the importance of the environment in explaining this process. Within this line of research, the work done by Fiedler [

11] deserves particular attention, where he conceived leadership as the product of the possible contingencies existing between the context variables related to leader–member relations, task structure, and position power. For Fiedler [

11] (p. 184), “the training of leaders [would consist] in diagnosing their group-task situation and in adopting strategies which capitalize on their particular leadership style”—in other words, in observing the combination of variables and acting accordingly (for a recent review of this model, see [

12]). Another major contribution to this perspective but laying the stress on the leader–follower relationship, is made by the concept of transformational leadership [

13]. This integrates previous contributions while distinguishing three styles: Charismatic (characterized by a rare combination of exceptional individuals and circumstances); transactional (which prioritizes the mere exchange of rewards between leader and followers); and transformational in the strict sense of the term, where leaders “point to mutual interests with followers. They engage followers closely without using power, using moral leadership. They transform individuals, groups, organizations, and societies” [

13] (p. 873). A recent review of the contributions made by this model in [

14].

An important transition can be observed in this approach to leadership research. From prioritizing the mere circumstances surrounding leaders and followers, it moved on to highlight what happens between the influencing individual and those who are influenced—a link that has been described as invisible [

15]. Nonetheless, this approach, with its emphasis on the interactive fact of leadership—either with the context or with people—encounters its main challenges in the why and how of the influence of leaders; respectively, the component of interaction that explains why leaders and followers exist, and the principle that underlies the interinfluence between leader and followers. This leadership, based on interinfluences, not only takes into account the context and the people in specific situations, but also integrates interinfluence and the value of sustainability [

16,

17], i.e., in a practice that, over time, is sensitive to the demands of the moment, without incurring standards or provisions that do not meet the needs of leaders and followers.

The social identity/social categorization approach. The combination of the theories of social identity (proposed by H. Tajfel) and self-categorization (with J.C. Turner as the main advocate) has engendered another approach to the issue of leadership. To be precise, its proponents have drawn on the two theories to conceive leadership as a process in which it is fundamental to belong to a group (the “we” or in-group) and feel that such belonging is key to our self-perception. In this regard, effective leadership follows these four principles [

2]: (1) Being one of us (leaders as the best representatives of the corresponding in-group prototypes); (2) doing it for us (leaders as in-group champions, i.e., being the main persons responsible for promoting the interests of the group); (3) crafting a sense of us (leaders as entrepreneurs of identity, i.e., actively working on the definition—and redefinition—of their own prototypicality); and (4) making us matter (leaders as embedders of identity, doing so through specific actions that distinguish the group from other ones—in the present and in the future). This conception of leadership, which counts on the respective empirical support [

18,

19], assumes that the prototypicality of any leader does not respond to immanent, rigid categories, but to the process that the said leader and his/her followers experience.

With the introduction of the prototype as a definition of leadership within an in-group, this approach to the analysis of leadership has integrated the individual and the situational in terms of the interinfluences between leaders and followers—without overlooking their transience: Who is a leader today may not be tomorrow. To this integration should be added an analysis of what, in the key of the individual and the collective unconscious, may stimulate the interinfluences of the leadership process at a given moment.

1.2. Heroism in Leadership: From the Collective Myth to the Psychological Typology of the Leader

In the three perspectives followed by leadership studies, there appears to be a tendency towards the integration of the individual and the social, as occurs in the case of prototypicality and in-group. However, this integration demands deeper analysis—and Jungian analytical psychology provides a promising perspective in this respect. This experience of integration is also related to the impact that is sought after with the promotion of sustainable leadership, which has one of its main goals in holistic personal growth and development [

20].

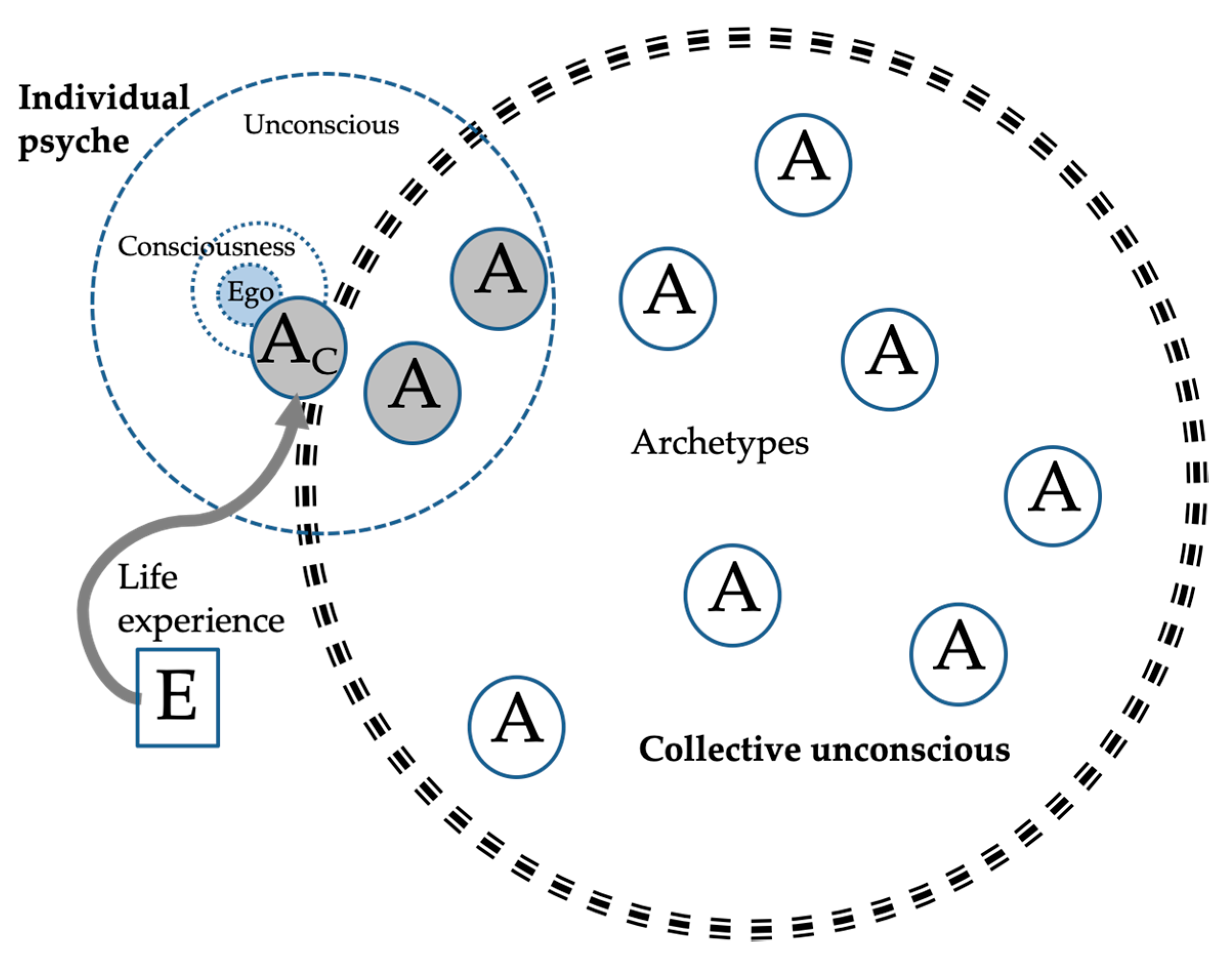

With the goal of introducing this perspective into the study of leadership, this section describes the main concepts of Jungian analytical psychology: First, the collective unconscious—highlighting the myth of heroism; then, the personal unconscious and consciousness (

Figure 1); and finally, the psychological types as constructs that allow the observation of the transit between the unconscious and consciousness. This description is intended to highlight the importance of integrating the leader’s unconscious (collective, personal) and conscious content, given that integration is crucial to fostering creativity in leadership—in women in the case in question.

The collective unconscious. This includes the main content “universal and of regular occurrence” [

21] (§270) transmitted by myths across human history; myths that constitute an opportunity to give voice to figures (known as archetypes), conflicts, and the concerns of individuals. By way of an example of this extant ancient content, let us imagine that a woman has been listening to her partner explaining problems in his/her job. She repeatedly warns him/her to be careful because something bad could happen to him/her. Later, her partner explains with surprise that a conflict has emerged at work. The woman says, “I warned you.” Her partner replies, “About what?” (Much to her bewilderment—or considerable annoyance, as the case may be). This everyday situation exemplifies a modern version of the myth of Cassandra, an archetypal figure (A

C, Figure 1) fated to be clairvoyant without anyone paying her any attention or believing her—in fact, her premonitions about the Trojan War were ignored. Also, it is possible that the woman’s experience (E, idem

Figure 1) in our example makes her aware of the relevance of the content of the collective unconscious for her individual psyche.

A common component of all myths is heroism, i.e., the presence of an archetypal figure—hero or heroine—whose extraordinary powers and adventures reveal important content for groups and individuals. For Jung [

23] (§68) the figure of the hero/heroine is the “symbolical exponent of the movement of libido”. In other words, just as each individual has a physical structure—which favors putting some abilities or others into practice—there is also a certain amount of psychic energy or libido waiting to be discovered and fostered. For Jung [

24] (§612), moreover, “The hero myth is an unconscious drama seen only in projection.” In other words, it is the content that individuals show of themselves and address to others. Therefore, the foundations for the transformation of the leader will be laid so far as the leader becomes aware of the heroic imaginary: “Further transformations run true to the hero myth” [

21] (§303). What is the consequence of this assertion? That on knowing the archetypal figures that most move a leader, the keys to what mobilizes the followers can be visualized. The description of the good-enough leader [

25] (p. 40) expresses this idea: A person who, aware of his/her limitations, can recognize himself/herself in figures such as the erotic leader (who “brings out and reflects back the healthy self-love and self-admiration that exists in everyone”), the trickster-as-leader (fostering an attraction to his/her visionary ideas), and the sibling leader (establishing alliances through decentralization and shared work in networks).

A woman leader might feel akin, for example, to the Wonder Woman heroine [

26,

27]. Fighting with aggressors to protect the weak, thanks to values such as strength and truthfulness, as well as having the power to deflect attacks by her enemies (such as the bracelets on her clothes, which deflect bullets). As a figure in popular culture, this update of the myth of the archetypal figure of the Amazon has gradually incorporated details from the imaginary of the different times that have elapsed since its appearance [

28,

29].

On the other hand, apart from the archetypal figures and myths known to the general population, it is necessary to identify the myths appearing in the individual psyche—with its own unconscious and conscious content.

The individual unconscious/consciousness and psychological types. This part of the individual psyche includes all the forgotten content (and which is repressed in some cases) derived from each individual’s experiences [

23]. In contrast with the unconscious, the consciousness—with the ego at the center—is made up of everything we remember and that our psyche makes use of in everyday life [

30]. The differences between the unconscious and the consciousness do not imply a division between the two. On the contrary: On the one hand, unconscious content can pass into consciousness—through dreams (while we are asleep) and fantasies (while awake); and on the other hand, what happens in the conscious mind can impact the unconscious—for example, a gesture from someone that has attracted our attention can be amplified in dreams, clarifying our idea of the other person’s intentions towards us.

Finally, apart from the fantasy content, another way to access the exchange of psychic energy between the unconsciousness and consciousness is through the psychological types [

31]. The main feature of this classification is the differentiation between introversion and extraversion. Each of these orientations of psychic energy can be present in the world of consciousness (being observed by those around us) or remain in the unconscious (i.e., expressing themselves indirectly).

With respect to the extraverted conscious attitude, the “orientation by the object predominates in such a way that decisions and actions are determined not by subjective views but by objective conditions” [

31], §563. Thus, an extravert leader will make financial decisions based on recent data offered by the market or the sales of competitors. By contrast, the extraverted unconscious attitude includes subjective impulses that go unrecognized—and are accepted with difficulty in the conscious mind (for example, not admitting unpleasant behavior when negotiating with someone who, deep down, we view as someone dishonest).

In the case of conscious introversion, the individual “is naturally aware of external conditions, [but] selects the subjective determinants as the decisive ones… Whereas the extravert continually appeals to what comes to him from the object, the introvert relies principally on what the sense impression constellates in the subject” [

31] (§621). In this sense, an example would be the introverted leader who makes decisions based on his/her subjective impressions of reality—and which those around may not share. With regards to the introverted unconscious attitude, this is characterized by an intensification of the object: This would be the case of the leader who, with far greater conviction and resolve than the rest, insists on carrying out a certain strategy—which she assumes to be something totally objective (which ultimately it is not).

Jung [

31] drew on this extraversion–introversion theory to propose the existence of four psychological functions, two rational ones (thinking, feeling) and two irrational ones (sensation, intuition):

Thinking (T), which “following its own laws, brings the contents of ideation into conceptual connection with one another” [

31] (§830). This would be the case of someone who, when deciding what furniture to buy for the office, is guided by rational arguments (objective or objectifiable: Quality, ergonomics, and price).

Feeling (F) includes two processes: On the one hand, attributing to an object “a definite value in the sense of acceptance or rejection (‘like’ or ‘dislike’)”; on the other hand, experiencing a mood that also implies “a valuation; not of one definite, individual conscious content, but of the whole conscious situation at the moment, and, once again, with special reference to the question of acceptance or rejection” [

31] (§724). An example of the predominance of this function would be the leader who chooses the furniture according to what she feels is right and wrong in its design (traditional or avant-garde, unobtrusive or conspicuous, etc.).

Sensation (perception, S), without being held to the laws of reason, “mediates the perception of a physical stimulus… [and] is related not only to external stimuli but to inner ones, i.e., to changes in the internal organic processes” [

31] (§792). Here, an example would be a reaction to the furniture where the purely aesthetic side prevails, linked to aspects such as color or form (experienced as ideal or horrible, for example—whatever the case, expressed in terms that could be described as exaggerated).

Finally, intuition (I), which “mediates perceptions in an unconscious way. Everything, whether outer or inner objects or their relationships, can be the focus of this perception… In intuition a content presents itself whole and complete, without our being able to explain or discover how this content came into existence” [

31] (§770) (original italics). In this case, our leader would introduce the subject by saying, for example, that in the morning—while having breakfast—the complete picture of how to transform the space and the way it would look had sprung to mind.

This typology has been measured with the Myers–Briggs Type Indicator [

32]. This scale offers data on polarities related to introversion–extraversion, thinking–feeling, and sensation–intuition. Depending on the person’s degree of consciousness of each of these functions, they are considered primary, auxiliary, tertiary, and inferior functions. Moreover, the MBTI incorporates judging (J) and perceiving (P) as attitudes for facing the outside world. The combinations of these aspects result in a total of 16 profiles that can vary throughout life, with their comprehension leading to better self-understanding [

33,

34]. In this study—and in line with the proposals in [

35]—we also considered the concept of value in relation to the levels of consciousness of the four psychological functions, thereby complementing the information provided by the MBTI. As representations that respond to needs transformed into goals [

36], values guide human actions [

37], being sensitive to historical and cultural aspects. The importance of values has been shown in the case of leadership [

38,

39,

40,

41,

42]—and specifically with regards to their relationship with leaders’ psychological typology and conception of heroism [

43].

To sum up, this description of the concepts involved in analytical psychology informs us of the possibility of taking into account aspects of the unconscious (collective, personal) and consciousness of leaders, through their vision of heroism and the corresponding psychological typology in conjunction with its value orientation. Thus, this approach goes beyond considerations about leadership based on Freudian-type psychoanalysis of the personalities of leaders and followers [

44]. The analytical psychology perspective makes it possible to complement any conception of the interinfluence between leader and members, which in sustainable leadership, is crucial to its “processes of connecting people, things and places; rather than being about a person or organizational position” [

45] (p. 1072). In the case at hand and as far as leaders are concerned, this is achieved by assuming that the personal characteristics they reveal integrate the personal and the collective—without having to choose between the variables of the individual or the situation when studying leadership.

Furthermore, this integrated approach has the potential to reveal the keys to what mobilizes a group under the influence of its leader. Consequently, we assume that there is much deeper content underlying the prototypicality that unites an in-group, which on becoming conscious, may offer a new source of energy that is conducive to creative leadership. Finally, it should be noted that the proposed integration of content is akin to the conception of sustainable leadership where the leader must have a long-term transdisciplinary vision [

46].

1.3. The Role of Heroism in Fomenting Creativity in Women Leaders from a Sustainable Perspective

In heroism, leadership research has a myth that provides the basis for a deeper exploration of the characteristics of unconscious (collective, personal) and consciousness of leaders—characteristics that can mobilize their followers. This paper goes on to show that heroism can provide a foundation that foments the creativity of women leaders, a conception that is also based on an applied vision of sustainability, i.e., going beyond ecological practices or activism in favor of environmental conservation [

47]. The development of this idea draws on previous evidence about heroism and the main obstacles observed in enhancing creativity and leadership in women—also connecting with the aspiration of an approach and leadership training that sustainably enhances the talent of women [

48].

As an explanation of leaders’ behavior, the study of the role of heroism reveals that the individual basis for what is considered heroic encompasses a series of specific features (categories, prototypes, self-representations) [

49,

50,

51]. Heroes have also been known to fulfill a series of functions that can be a powerful social influence for other individuals [

52,

53,

54]—and, specifically, in the relationships between leader and followers [

55,

56]. Moreover, the function of heroism in leadership is consistent with contributions linked to the idea of heroism as a tool for providing guidelines that influence the way individuals may lead their own lives [

57,

58,

59,

60].

However, the question remains: Once a leader becomes aware of the heroic figure that he/she is mobilized by, how can this experience be translated into creativity? According to the precepts of analytical psychology [

61], the answer lies in activating those archetypal images that, even though they come from antiquity, personify present-day conflicts, and suggest possible solutions not previously contemplated. Therefore, transcendent creativity would ensue as a consequence of this experience, according to which the most important thing for the individual is “to give voice, to announce something beyond himself, something transcendent” [

62] (p. 14). Thus, the connection with the content of the collective unconscious, which anyone can draw on at any given moment, constitutes an important step towards contact with creative material [

63]—in the way of artists (with regards to the importance of interdisciplinarity in fostering creativity, see [

64]). The phenomena of collective creativity may be observed in addition to this transcendent creativity—which consists of being able to predict a formula for success in a group of individuals. On the other hand, the type of creativity that facilitates self-expression and self-development in individuals—without much involvement of other people—remains on a more personal level [

62,

65,

66]. This conception of analytical psychology is linked to and expands the definition of creativity [

67]: “The ability to perceive new relationships, and to derive new ideas and solve problems by pursuing non-traditional patterns of thinking”.

Research on creativity has to take into account both the so-called intraindividual components and the external components (those provided by the social context [

68]). Here, a paradox has been observed [

69]. On the one hand, the benefits of creativity in individuals have been demonstrated, but on the other hand, since creativity implies innovation, it may meet with resistance from conventional positions. This dual circumstance is particularly evident in studies on creativity and women. In this sense, research on the characteristics of creative women has highlighted, among other aspects, the capacity of the imagination and an originality that is not exempt from a certain rebellion against conventions [

70,

71,

72,

73,

74]. All told, the exercise of creativity in women has encountered a lack of support in their surroundings [

75,

76].

As far as women’s leadership is concerned, the research carried out highlights the coexistence of two realities. On the one hand, there is a greater presence of women as leaders in various sectors of society [

77,

78,

79]. On the other hand, the obstacles that society itself puts in the way—more or less implicitly—of women’s leadership make it difficult to consolidate and place on an equal footing with men’s leadership [

80]. As a strategy to cope with this situation, the importance of authenticity has been highlighted [

81], which suggests a preparation that favors the empowerment of leadership in women [

82,

83], with special emphasis on their creativity: “In order for the force of women’s leadership to continually build momentum in dominant organizational cultures, women leaders must be able to fully, rather than just strategically, engage in their unique, feminine, creative, and innate approaches to leadership” [

80] (p. 21).

According to the above, the new ideas and non-traditional patterns of relationships could be transferred to women’s leadership, on women becoming aware of the characteristics derived from the collective unconscious that make up their own heroism [

84]. Through this consciousness, women emerging as leaders would have a basis to develop new ways of articulating their individuality in relation to the group. In addition, this articulation would offer an alternative to the previous corpus of scientific knowledge, which has reported the difficulties involved in advancing women’s creativity and leadership.

Lastly, it must be highlighted that the approach adopted here appeals to the unique, innovative qualities that women as leaders are able to contribute in favor of sustainability [

85]; i.e., it is optimal management that caters to the individual and the group both in the present and with a view to the future [

86]. Specifically, the comprehensive self-knowledge proposed by this research shares three principles of sustainable education [

87]. To be precise, being able to articulate one’s own imaginary of heroism in practice favors integrative thinking and practice; attending to the implications that one’s own heroism has in the present and the future works in favor of envisioning change; and the foundations for achieving transformation are laid by making conscious the guidelines for personal and collective change. In short, the fact that women as emerging leaders experience personal and collective content (conscious and unconscious) entails experiencing dimensions of sustainable learning such as awareness of their own professional skills [

88], as well as the empowerment for life of the already available modes of reasoning and expression [

89].