2.1. Connotation and Teaching of Packaging Design

The American Packaging Association defined the term “packaging” as “the preparation work implemented for the transportation, circulation, storage, and sale of goods” [

4]. Packaging design begins from the type of packaging protection required and extends to the effective dissemination of brand image. This process involves usage function, visual design, and brand marketing problems [

6]. The original functions of packaging are to protect and contain merchandise. However, as time has passed, consumers’ consciences have become more critical, and the consumer social structure has developed. Apart from the initial function of merchandise protection, packaging is also expected to increase sales [

5]. From the commercial perspective, packaging design requires planning for addressing comprehensive packaging problems. The content of packaging design should at least include the choice of packaging methods and materials, the visual design thinking (which is the surface pattern design) [

15], and the transmission and added value of brand messages [

16]. Thus, packaging is not only a protector of products but also a silent salesperson. This is because merchandise packaging influences consumers’ evaluation of products and consumption desire [

17].

Merchandise packaging is present in everybody’s life. It not only plays the role of a silent salesperson but also adds value to the merchandise [

15]. Therefore, packaging influences life, and vice versa [

18]. Generally, packaging design can be divided into commercial packaging design (or consumer packaging design) and industrial packaging design (or structural packaging design) according to its purpose [

19]. Both types of packaging design must have the following five major functions: (1) merchandise protection and storage; (2) merchandise transportation and distribution; (3) merchandise safety and sanitation; (4) brand identification and merchandise information transmission; and (5) use of recyclable and reusable packaging materials [

20]. To accommodate the demand for packaging design talent in the 21st century, countries worldwide are reforming the design education system and exploring various potential methods for cultivating packaging designers. The model for cultivating packaging design talent involves the social economy (brand marketing), politics (environmental protection and carbon reduction), and culture (local characteristics) [

21]. Therefore, different eras require differing talent cultivation models, and the current era also entails its unique model for fostering design talent.

From the perspective of design education, packaging design is a compulsory subject in most design departments, demonstrating its importance. However, in packaging design courses in Taiwan, teachers mostly emphasize professional theories. This teaching approach inefficiently guides students using dynamic thinking and static teaching to transform design concepts into products. This is because under this approach, the teaching environment is closed-minded and limits teaching methods; teachers must also follow specific teaching norms and orders. Consequently, the entire teaching process suppresses design thinking and is passive and narrow-minded [

7]. To address this problem, Yang [

4] made several teaching recommendations: (1) A design course should be introduced using real products, and students should practice in groups; (2) students should gain an understanding of packaging concepts on the basis of their acquired knowledge; and (3) students should be guided to improve their design expressiveness and communication ability from the perspective of the industry. To conclude, packaging design courses are valued in Taiwan, but teachers focus overly on theory lectures. Thus, students cannot determine the relationship between merchandise packaging and consumers or identify the real needs of consumers. Consequently, the packaging design courses in Taiwan must be reformed to increase their innovativeness.

2.2. Application of Design Thinking

A learning trend for design thinking has recently spread throughout the industry and academia. T. Brown, the president of the IDEO design company, defined design thinking as a human-centered approach that considers people’s needs and behaviors as well as the feasibility of technology or commerce [

22]. The design thinking model well known today was originated from Stanford University in the 1980s. Since then, the Hasso-Plattner Institute of Design at Stanford (i.e., the d. school) has used design thinking methodology to train students to first consider the perspective of human needs. Thus, the real problems between products, services, and consumers can be solved. The innovative solutions that conform to users’ needs can be developed from all walks of life and be unpredictable [

23].

To respond to the trend of social complication and meet consumer needs, the methodology of design thinking has been deeply valued by scholars. Additionally, it has been widely applied by enterprises and organizations to solve commercial and social problems [

9]. In the past 10 years, increasing numbers of scholars have advocated design thinking because this methodology can provide innovative methods of problem solving in greatly complex society and environments [

23]. Design thinking is suitable for training interdisciplinary teams. Design teams start from the dimension of emotional analysis and emphasize the relationships between topics and users. Specifically, they start from understanding problems, and then proceed to the steps of problem inspiration, ideation, and implementation [

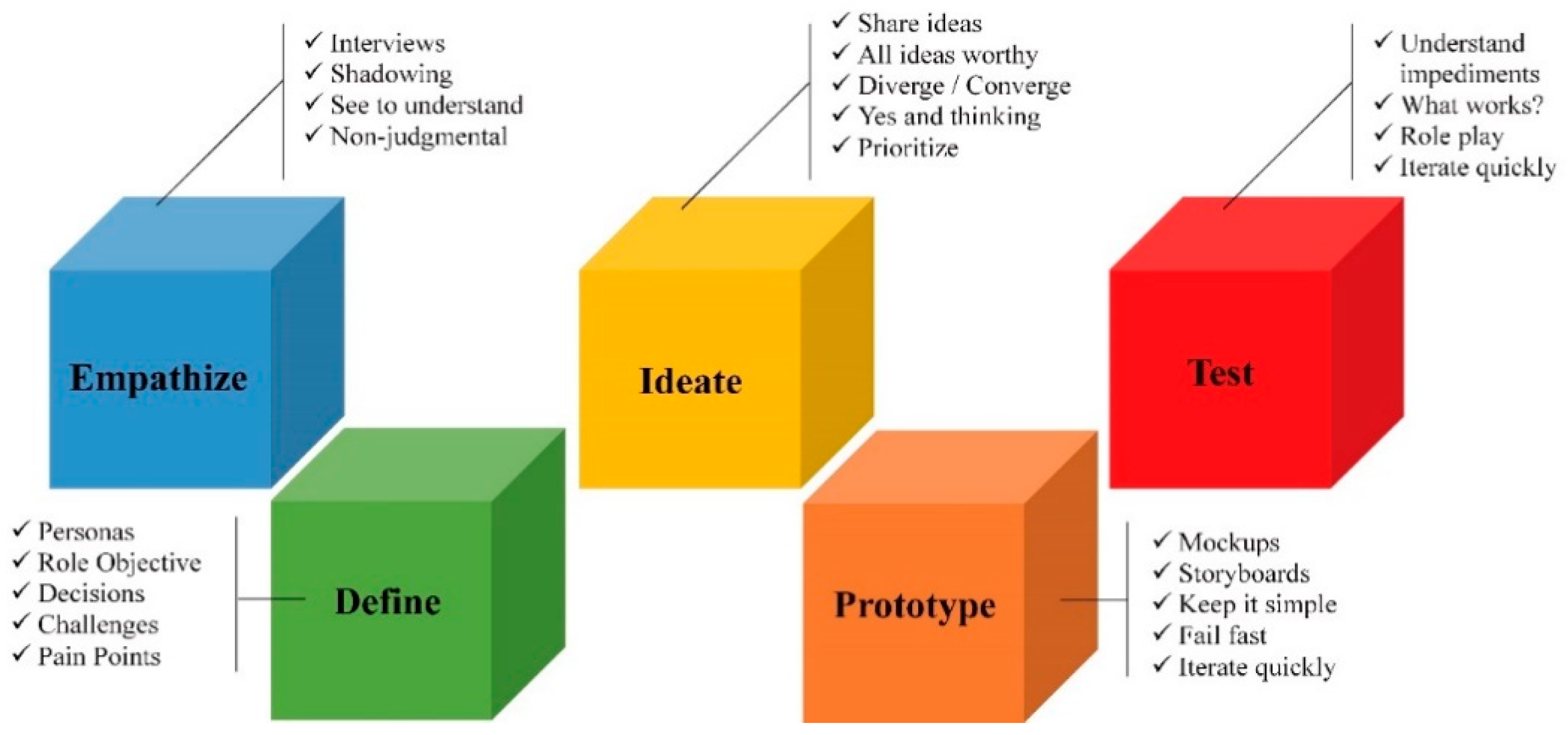

24]. Currently, most teachers simplify the conception process within design thinking into five major steps: empathy, definition, ideation, prototyping, and testing [

25] (

Figure 1).

In various fields, the production and accumulation of knowledge originate from activities. Design thinking is an activity in which strategies and methods are proposed through group brainstorming for solving problems [

11]. Johansson-Sköldberg et al. [

24] stated that the design thinking methodology accounts for both theories and practice. Teamwork is needed to solve complex problems and create innovative design outcomes. Therefore, teamwork is highly crucial to the design thinking training of students. Dunne and Martin [

9] mentioned that design thinking involves combining the ideas of every group member and finally proposing the optimal solution to the problem through teamwork. This method can be used to not only create products but also conduct organization management and address social issues. In training on design thinking, teaching students to discover human needs through observation is essential [

26]. Lindberg, Meinel, and Wagner [

27] indicated that the training focus of design thinking should be the construction of novel ideas and discovery of solutions for wicked problems. In the process of creative thinking, everyone can propose ideas and several ideas can be combined to form an innovative design proposal. Finally, Tschimmel [

28] reported that design thinking is a series of problem-solving processes from discovery, definition, and development to delivery. Group members collectively come to understand the problem, observe populations, brainstorm, and finally manufacture the product prototype. This process enables all members to focus on the same theme and propose an innovative idea that meets consumer needs.

2.3. Nature and Measurement of Creativity

The verb to create comes from “creatus” in Latin, which has the meaning of bringing something into being [

29]. American psychologist Guilford defined creativity as “the individual ability to create novel, unique, fluid, and refined products,” and this is the most widely accepted definition [

30]. In addition, the content of creativity involves four critical factors, which are called the four Ps of creativity: person, process, product, and press or environment [

31]. Although creativity is considered a basic cognitive ability [

32], numerous scholars consider creativity to be one of humanity’s most complex behaviors. Measuring creativity using a single index in real life is difficult [

33]. Theoretically, the measurement of creativity can be divided into the single approach and confluence approach. The single approach involves discussion of personality traits and the characteristics of thinking or products. The confluence approach involves discussing the expression of creativity and how creativity is generated [

34]. Most scholars state that creativity cannot be considered using the single approach, because measured results only have meaning when there exists a confluence of multiple factors [

35].

Williams [

36] reported that in teaching scenarios, observation of students’ cognitive and affective performance has a strong positive influence on their creativity. The cognitive behavior is the students’ acquisition of knowledge concepts, principle applications, and problem-solving ability, whereas the affective behavior is the students’ affirmative or negative psychological reactions to external stimulation [

37]. If teachers can adequately use tools to measure cognitive and affective behaviors, they must be able to understand the improvement of students’ creativity. Cropley [

38] further indicated that creative performance can be evaluated in four dimensions: knowledge, thinking skill, motive, and personality traits. Personality traits are particularly critical because a person’s traits and will are the key to determining whether he or she can become a creative person [

39]. In addition, in the investment theory for creativity proposed by Sternberg and Lubart [

35], personality traits are one of the six main resources required for creativity. In fact, creativity tendencies are the personality tendencies that individuals exhibit during creative activities [

40]. This personality tendency includes attitude, motive, interest, and emotion [

41].

Regarding the personality traits relevant to creativity, Qian, Plucker, and Shen [

42] have considered creativity tendency to have the strongest influence on creativity. Studies have also demonstrated that the creativity tendency has a positive influence on the creativity of students. The creativity tendency scale in the Creative Assessment Packet designed by Williams [

37] is the scale most used by scholars to evaluate the personality traits relevant to creativity tendency [

42]. In addition, Tierney and Farmer [

43] proposed the concept of creative self-efficacy to evaluate the application of self-efficacy in special fields. Linnenbrink and Pintrich [

44] reported that the concept of self-efficacy is applicable to specific fields and scenarios; hence, it is strongly predictive when evaluating specific learning activities. Various scholars have discovered that creative self-efficacy has a positive influence on creative performance [

45,

46,

47]. Mathisen and Bronnick [

48] further reported that when students have higher creative self-efficacy, they are more confident in their creative behaviors. They are also more willing to accept challenges and thus be even more creative. Finally, Csikszentmihalyi [

49] proposed flow experience to explain the relationship between situational motivation and creativity. He stated that in any creative activity, if the creator can fully focus to the level of neglecting everything else and losing track of time and space, an ultimate playful feeling is created, and creativity is expressed [

50]. Thus, the flow experience can be used to express a person’s feelings during a creative activity. The stronger the flow, the more fun the person is having, and the more creative the person is likely to be. In summary, the study hypothesizes that in the field of packaging design, team members brainstorm and share their creative ideas without criticism through the power of teamwork. This could help creators to more easily immerse themselves in the creative process, stimulate personal creative self-efficacy, and ultimately exhibit self-creativity.