Abstract

This paper explores university discourse as a conceptual-communicative macrostructure that verbally represents international organizations’ and universities’ policies and activities to support youth’s sustainable development to support youth’s sustainable development amidst COVID19. The materials include universities’ official site information and higher education-related data from international organizations regarding universities’ activities during the pandemic. The textual corpus from 172 universities from Africa, Asia, Europe, North and Latin America, Oceania, as well as 164 documents with essential international institutional affiliations, were explored. The methodology combined qualitative and quantitative tools, theoretical, and empirical analysis. Data processing rested on thematic content analysis. Manual and computer-based coding techniques were applied. The analysis made it possible to identify major concepts and their constituents which form a verbally expressed conceptual macrostructure of university knowledge and action in fostering youth’s sustainability during pandemics. The findings revealed some standard features within universities communication dimensions, on the one hand, and some specific to Russian universities on the other. Differences between universities and international organizations concerning communication focus were also identified. The research findings result in tentative recommendations to bridge Academia, University, and Society in efforts to foster youth’s status and sustainability in contemporary civilization.

Keywords:

education; sustainability; higher education; university; youth rights; communication; discourse; pandemics 1. Introduction

Youth is considered the human treasure and driving force for the development of civilization.

The UNO Agenda 2030 lays particular emphasis on the youth population in a number of its sustainable development goals (SDG), including health, education, and other issues.

As far as education is concerned, it is considered within SDG4, regarding the quality of education. Reference to higher education is found in several targets. Thus, target 4.3. declares the goal “by 2030 to ensure equal access for all women and men to affordable and quality technical, vocational and tertiary education, including university.” [1]. Target 4.4. proclaims “the elimination of gender disparities and vulnerable population access to all levels of education”. Among other targets of SDG4 the need for “productive learning environments, qualified teacher training, education for sustainable development and sustainable lifestyles, human rights, promotion of a culture of peace and non-violence” are mentioned [ibid]. As far as universities are concerned, they have been considered as a crucial tool for societal development across centuries [2]. Today higher education also plays an essential part of other goals related to poverty (SDG1); health and well-being (SDG3); gender equality (SDG5) governance; decent work and economic growth (SDG8); responsible consumption and production (SDG12); climate change (SDG13); and justice and strong institutions (SDG16) [ibid.].

However, currently, the sustainable development of global society is challenged by COVID 19 pandemic. It should be acknowledged that global health emergencies have shattered the world across centuries, including plagues, flus, AIDS, Zika, MERS, and COVID 19. Such diseases affect global society as a whole and lead to economic losses, political tensions, social constraints, which produces a negative impact on various sectors both at national and global levels [3]. Moreover, world-wide health emergencies result in the spread of disruptions which affect more specifically vulnerable populations, including youth [4].

Thus, it is logical that in line with past and present health emergencies researchers focused on the health communication crisis during SARS [5], on public governance issues during SARS [6], on students’ stress, anxiety and psychological adjustment during SARS in different countries [7,8,9], and on media effects on students during the SARS outbreak [10]. Earlier scholars have also considered sanitary actions and health care management during H1N1 outbreaks in different countries [11,12], exploring students’ perceptions of respective activities [13,14] and their mental status [15]. Researchers also investigated university staff and students’ attitudes towards H1N1 pandemics in general [16,17], and measures to ensure preventive health behavior in university settings during H1N1 [18,19]. Studies conducted in previous years concentrated on the tasks of universities providing consistent communication within the campus during emergencies [20], and also specified the need to engage youth in community emergency preparedness [21].

However, no explicit connection between the above disruptions and no focus on the concept of youth sustainability has been fostered so far.

This research follows the general vision of the concept of sustainability which scholars view “as a holistic concept …whose challenge is to live in harmony, attending to environmental, social and economic variables, and to build a responsible and plural future over time” [22].

As far as youth sustainability is concerned, the latest research developments consider it as a multidimensional phenomenon that comprises young people’s health, social inclusion and financial support, knowledge and education, international and national policies and governance, to foster tools for youth to obtain opportunities and benefits within the above-mentioned areas [23]. Therefore, it is logical that currently academia calls for studies that aim to identify stakeholders, their policies and actions that contribute to youth’s sustainability, supported and fostered by universities amid the current COVID 19 pandemic [24]. Meanwhile, scholars agree that the university discourse on sustainability includes communication on various topics, including education and research, university governance [25], campus operations [26], and institutional digitalization [27], including sustainable management of higher education digital transformation [28]. However, researchers agree that the study of the university’s role and potential in enhancing youth sustainability still lies ahead [29].

The present research hypothesis pursues a number of arguments:

- (1)

- university discourse can play a comprehensive role in fostering youth sustainability in society in times of pandemic

- (2)

- this comprehensive role is revealed through verbally expressed policies of universities and higher education-related organizations in relation to the topic under study

- (3)

- university discourse on youth sustainability can be introduced as a verbally expressed conceptual-communicative macrostructure of knowledge and action.

The research goal is to check the above hypotheses and explore trends in international institutional and university discourse in relation to youth sustainability in society amidst COVID19 from the angle of discourse trends in verbal representation.

In line with the above hypotheses, goals and academic vision regarding university discourse on sustainability, the respective research tasks are as follows:

- (1)

- exploring current trends in academic studies related to the research topic

- (2)

- analyzing international universities’ discourse across the world on youth issues amidst the current pandemic to identify verbally expressed concepts regarding policies and actions

- (3)

- investigating international organizations’ discourse on university tasks amidst the current pandemic to identify verbally expressed concepts regarding policies and actions.

The key findings highlight the common and specific features of worldwide university communication during COVID 19, reveal some particular trends across major Russian universities, provide background understanding of international organizations’ vision of such communication, and refer to preliminary recommendations on the verbally expressed conceptual macrostructure of university discourse to contribute to youth sustainability amidst the global pandemic.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Research Methodology Framework

The research rested on an integrated paradigm: combined qualitative and quantitative methodologies, theoretical and empirical analysis. The theoretical part followed the comparative approach to the investigation of academic papers that refer to the present research theme. The empirical part exploited a set of principles, approaches, theories, and techniques.

First, the principle of interdisciplinary studies of discourse [30] should be mentioned. It implies comprehensive analysis of linguistic data [31] with regard to cognitive-semantic macrostructures of communication that mirror some part of human reality [32], with a view of discourse as verbal representation of social semiotics [33] within a particular societal context [34].

Next, Minsky’s [35] frame-based approach for representing knowledge was implemented. This theory served as the background to identify constituent items of concept formation through discourse production regarding youth sustainability.

Moreover, the research also exploited the theory of text complexity, expressed through conceptual density [36,37]. This theory helps to explore the complexity of cognitive processes and knowledge construction practices.

The analysis also used a grounded-theory approach. Scholars recommend this approach when no previous comprehensive data is available in line with the research theme [38]. In our case a grounded-theory approach was applied to consider field-based evidence and laid the grounds for further inductive reasoning.

The study also rested on the dispositive approach. This concept is used in line with Foucault’s theory [39]. This approach allowed the author theoretical grounds for the study of the conceptual tree architecture of the discourse on youth sustainability.

The case study [40,41] and corpus-based [42,43] techniques were applied to structure the empirical data. Manual and computer-based thematic content analysis [44] were used for data processing.

2.2. Data Collection

The research focused on institutional communication within a digital environment which has become part and parcel of universities’ and organizations’ channels for internal and external communication [45].

The research data included two types of source.

The primary sources incorporated information from university official sites on university policies and activities related to COVID 19. The Quacquarelli Symonds (QS) ranking system site [46] was used for university selection (see Appendix A). Two universities with the top-ranking position from each country were subject to analysis. The order of countries appears in line with their ranking position in the data list. A total of 149 universities from all regions of the world (Africa, Asia, Europe, Latin America, North America, Oceania) were explored.

The list of universities that were subject to investigation, with links to their websites, is provided in Appendix A. Data related to COVID 19 issues with regard to students was relevant for the date of 31 May 2020. 23 Russian universities, including two of the oldest and most powerful national institutions and 21 members of the Russian nation-wide academic excellence project 5-100, were also considered. The list of Russian universities subject to investigation, with links to their websites, is provided in Appendix B.

Variables for the primary source data included the university’s national origin, position in the ranking system, private/public status, and comprehensive/narrow-specialized nature. The textual corpus for university data reached 1,056,000 words, each university’s textual data varying between eight–twelve items, with an average text size of 614 words.

Secondary sources included higher education related international institutional documents regarding universities’ activities at the time of the 2020 pandemic. The data incorporated 164 documents from international and regional organizations, including UNO-affiliated agencies, the Council of Europe (CoE), the World Economic Forum (WEF), the World Bank, analytical data from internationally ranking corporations (QS and The Times Higher Education THE rankings), professional associations in the field of higher education, etc. In line with the research tasks, the Russian authorities’ data on higher education during COVID 19 were also subject to analysis. The list of organizations and links to the websites/platforms from which sources were retrieved is introduced in Appendix C. Variables for the secondary sources data included organization status (international/regional), type of activities (comprehensive/specific field-focused), and genre of the textual data. The textual data for secondary sources corpus amounted to 239,112 words, each document’s average size reaching 1458 words.

2.3. Data Processing

The textual data concerning each institution was first arranged as a separate case and then integrated into the university or international institutional discourse sample corpus.

Data processing including manual and computer-based coding techniques was applied.

The manual coding procedure was implemented by the author and three independent coders, who are Peoples’ Friendship University of Russia (RUDN) university professors of English and deal with discourse and translation studies, with over 20 years’ experience in research and teaching.

The coding process included predetermined and emergent codes [47]. The manually identified codes were subject to comparative analysis to reach inter-coder reliability among the above mentioned team of coding experts.

The second stage used the QDA Miner Lite tool (https://qda-miner-lite.software.informer.com/1.2/).

The analysis further included a computer-based automated search to identify the list of the most frequent word combinations and their affiliation with manually identified codes in the whole corpus.

In line with guidelines concerning required percentage in statistical research on language [48], only codes that reached 90% coincidence within the coders’ data list and the computer-based list of most frequent word combinations were considered at the next stage of the study.

Further, the texts were organized into an electronic corpus for computer-based analysis through QDA Minor Lite. This tool was used to identify major concepts and their constituent slots within this structure and to consider their percentage use in the course of verbal discourse on youth sustainability.

3. Results and Discussion

This section provides data and its interpretation in line with the research hypothesis, goal and tasks. In line with the latter, this part includes three sections. Each one starts with the description of the obtained findings and moves to the discussion that considers them with respect to the tasks and hypothesis statements.

3.1. Current Trends in Academic Studies

This section introduces the empirical findings in line with research task one and discusses them with respect to research hypothesis statements one, two and three.

3.1.1. Findings

The results of literature analysis reveal that COVID 19 has triggered academic research on the issues related to the challenges that youth faces amid the pandemic.

Academia explores various dimensions of the phenomenon. Some papers explore the impact of the pandemic on national educational systems, including the experience of particular countries [49].

The research tends to outline multidimensional activities of universities during the pandemic. Thus, scholars report that during the pandemic outbreak in their country university alumni engaged in raising resources and arranging medical supplies, scientists focused on emergency research, teachers had to enhance and refresh ICT based teaching tools and tactics, and university specialists also took an active part in providing psychological support services for local communities affected by the pandemic [50].

The study of literature makes it possible to say that scholars pay consistent attention to particular examples of university governance planning during the current pandemic.

Thus, Regehr and Goel [51] consider the stages of university management at various stages of health emergency in regard to COVID 19, including key stakeholders, measures, and target audiences at pre-planning, approaching crisis, immediate crisis, prolonged uncertainty, and recovery stages. It seems important that researchers use concrete university examples of COVID-19 related policies and guidelines [52].

Scholars also explore diverse university community attitudes to knowledge dissemination and disease prevention policies and practices [53], and analyze these activities from the angle of their influence on youth confidence in the context of their national government policy as a whole [54]. In line with the above, researchers argue for the urgent need to systematize and target communication with youth during the pandemic [55], to foster the call for youth inclusion “in matters that affect their lives” [56], and to underline the importance of “youth leadership in rebuilding a sustainable world in the post-COVID 19 period” [57]. With respect to this issue scientists further highlight the relevance of providing culturally responsive and sustaining youth participatory activities during COVID-19 [58]. Studies from different countries confirm the rise in patriotic feelings among youth who engage in social volunteering and support for vulnerable populations during COVID 19 [59].

Scholars also consider economic consequences that might affect young lives due to the potential unemployment rise in the post-COVID 19 period [60]. Moreover, researchers predict changes in the philosophy and policy of education in various countries [61], prospects of higher education internationalization in the student community, and autoethnography being revisited [62]. Topics relating to the specific requirements and tools for unscheduled digital pedagogy also draw specialists’ consistent attention [63]. Within this area of academic studies current papers argue for particular instruments for unscheduled on-line teaching and explore perspectives thereof in different countries, including, for instance, China [64], Georgia [65], and Ghana [66].

Academia also focuses on students’ feedback concerning unscheduled online learning [67] and lays emphasis on the mental, psychological, and physical condition of the young generation. Scholars acknowledge that COVID 19 affects youth’s mental health [68,69] and changes the psychological conditions of students and staff [70,71,72]. Further, specialists warn about the negative consequences of physical inactivity and sedentary behaviour in youth due to quarantine measures [73], and even say that there might be a potential generation lost in terms of sports activities [74].

Some papers focus on specific youth audiences. Researchers reveal challenges that incarcerated youth face in solitary confinement during COVID 19 [75,76]. There are also increasing voices on violence and abuses of youth during the pandemic [77] and these explore school measures to prevent these challenges [78].

The latest publications also relate some of the above mentioned areas of higher education institutions’ activities during COVID 19 specifically to foster universities’ internal and external communications, in order to contribute to sustainability in society amid the pandemic [79].

The above brief description of findings from research papers about COVID 19′s impact on university policies, activities, and challenges that the student population faced leads to the following discussion.

3.1.2. Discussion

The results of the literature review reveal that academia strives to respond to the burning issues related to university and institutional support for youth within the pandemic landscape. However, the current analysis concerns particular countries. Researchers have not moved to an international dimension yet. To our mind, this is due to the initial stage of the research within a particular period of time. Country specific data needs to be accumulated first. Therefore, a cross-country study of university communication on youth issues during COVID 19 seems timely as it helps us to consider the situation through the lens of international practice to identify global trends. Additionally, such a world-based perspective would continue academia’s long-standing tradition of viewing the university’s capacity to contribute to sustainable social development across the centuries [80,81]

Moreover, the above-mentioned papers focus on specific issues (i.e., social, educational, and health) with no explicit reference to the idea of the comprehensive role which universities can play during pandemics with respect to youth’s sustainability. Meanwhile, there is an academic tradition of considering the role which university activities and communication can implement within the global agenda on sustainable development [82,83]. Thus, an explicit message on the need to explore and foster the comprehensive role of the university in supporting the community in general and youth in particular during COVID 19 seems timely and productive within the framework of the UNO Agenda 2030 on sustainable development.

The study of existing research findings shows that they distance themselves from themes related to verbal representation of policies that universities and higher education-related organizations conduct in relation to the topic under study. Current papers focus on students’ perceptions and university measures themselves and omit the consideration of their conceptual representation through the means of linguistic discourse. The review of the literature confirms that academia does not on the whole view university discourse on youth during pandemics from the angle of a linguistically “shaped” conceptual macrostructure of university knowledge and action to foster sustainability among this population in times of health emergencies. These themes have not been subject to research with reference to official communication from international higher education related organizations. Meanwhile, interdisciplinary discourse studies confirm that language bears a strong power within society [84], and influences human minds, policies and actions [85], underlining that particular structural categories can play a critical role in communication as a tool and guide for action [86]. Thus, there is a contradiction between the discourse studies tradition in general, on the one hand, and current research on university communication during pandemics, on the other.

The above deliberations contribute to the need to explore university discourse verbal units from the angle of their capacity to foster youth’s sustainability during health emergencies.

3.2. International Universities Discourse across the World on Youth Amidst the Current Pandemic

This part of the paper introduces findings with regard to research task two that requires the identification of verbally expressed concepts relating to the respective institutions’ policies and actions. The findings are represented in two sections. Section 3.2.1 integrates data on major conceptual and structural features of university communication related to COVID 19 across the international landscape, including some specifics relating to specific universities across the world. Section 3.2.2 provides particular comments with respect to leading Russian universities. The discussion of empirical results is introduced in Section 3.2.3 in line with the research hypothesis statements one, two, and three.

3.2.1. Common and Specific Features of University Discourse across the International Landscape

The general profile of the universities whose discourses’ conceptual-communicative structure was subject to study is introduced in Table 1. This lists institutions with regard to regions, countries and number of sources. The data shows that the analysis covered four universities from two African countries, 56 universities from 28 countries in Asia, 23 universities from 12 countries in Latin America, four universities from two countries in North America, and four universities from two countries in Oceania. The references and links to the websites of the particular universities are introduced in Appendix A (universities across the globe) and Appendix B (Russian universities).

Table 1.

General profile of primary source data with regard to regions, countries and number of universities.

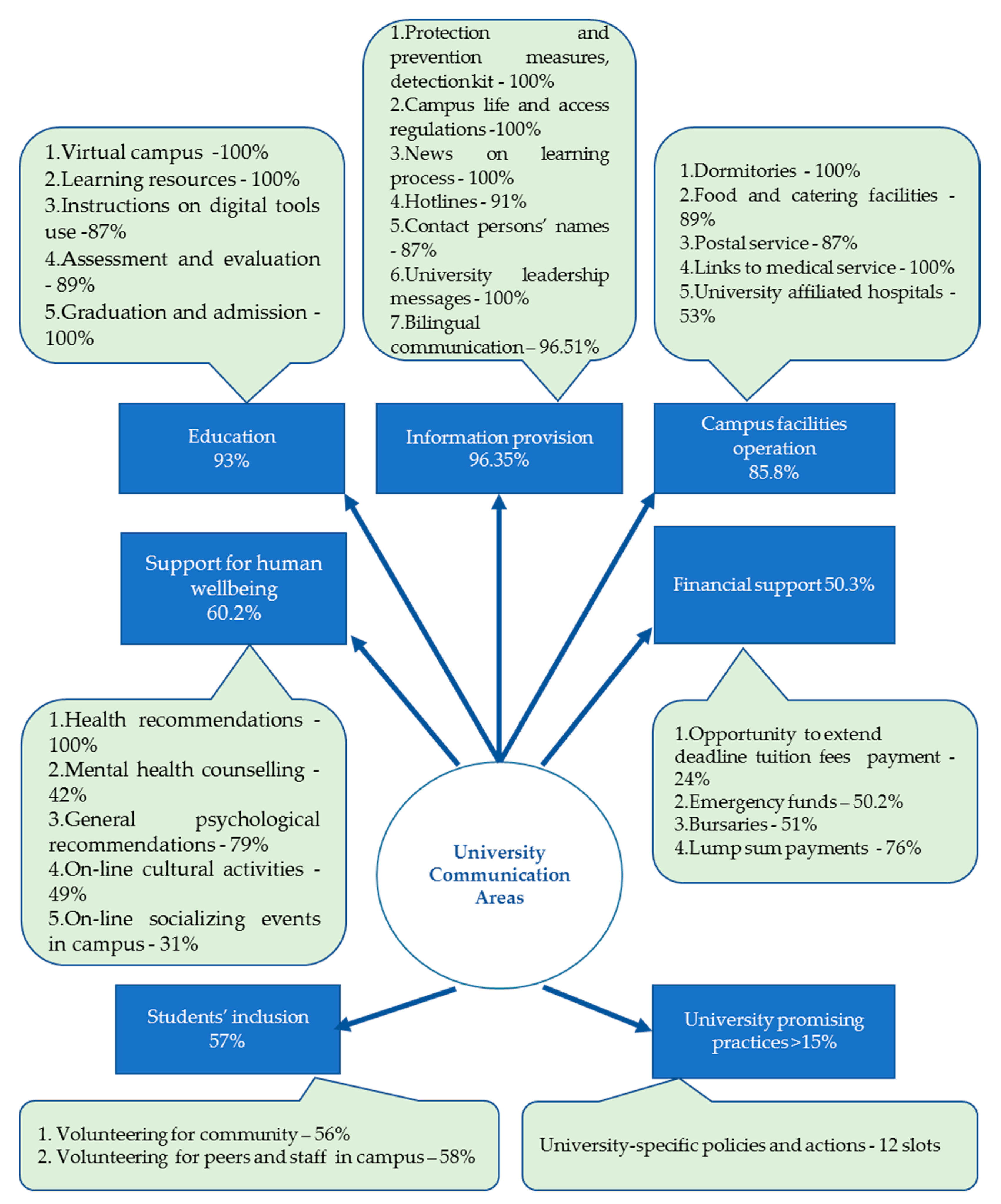

The analysis focused on university website content. Each university’s data were considered as a textual case. The content-based analysis revealed a set of thematic codes, which characterize specific university communication topics related to COVID 19 issues. Further, these universities’ overall textual data were subject to computer-based processing that identified the most frequent language units and their affiliation with the thematic codes. The results of manual and computer-based coding and thematic content analysis made it possible to identify major concepts and constituent slots that characterize university youth-centered discourse, its aims, and its respective tools. The data is visualized in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Concepts and their slots within the phenomenon of universities communication within the COVID-19 pandemic. (Author’s data).

Seven major concepts were specified within the phenomenon of international universities’ communication within the COVID 19 pandemic (dark blue boxes), whose presence on the university websites reaches at least 50%. The concepts consist of particular constituent slots (light green boxes). Currently, 31 slots are present in communication practices of either every or most (over 50% of data) universities from the list under study.

In addition, 12 specific items have been found with regard to particular universities. These items are united under the concept of ‘University promising practices’. They do not reach 50% presence in the textual data under study. However, it seems relevant to take them into account as examples of positive experience.

Analysis reveals that the list of these slots varies with respect to a particular university. The most consistent list of such slots refers to the concepts of Information provision, Education, and Campus facilities operations. Communication on the issues related to support for the human being, student inclusion in society activities to stop the virus spread, and financial support shows a lower percentage of concept constituent slot distribution frequency. However, the absolute figures of some slots within the mentioned concepts are higher, as the figure reveals.

The slot Bilingual Communication within the Information provision concept deserves particular comment. Most universities in countries whose state language is not English provide information in English. This seems to mitigate information provision tension in terms of foreign students’ access to information in case they have not mastered the local language.

The University promising practices concept also requires a specific consideration. We have distinguished this concept as a conventional one due to the fact that the analysis revealed specific topics of a particular university’s communication. The examples of such topics are as follows, and the respective slots were:

- (1)

- Self-quarantine is a civic duty (Kuwait University, Kuwait)

- (2)

- University as an institution which, in cooperation with industry, produces a systemic input into society’s fight against the pandemic, including plasma donation, ventilator supplies, patient treatments, data analysis, vaccine development (Universidade de São Paulo, Brazil)

- (3)

- Tuition exemption for students affected by COVID-19 epidemic (Kyoto University, Japan)

- (4)

- Measures and principles for preparing an individual continuity plan for remote learning (École polytechnique fédérale de Lausanne, Switzerland)

- (5)

- Device borrowing service (The University of Sydney, Australia)

- (6)

- Opportunities for on-line internship (Sapienza University, Italy)

- (7)

- Graduate support on the job market, on-line fairs for graduates’ job placement (McGill University, Canada; Tsinghua University, China; Tomsk State University, Russia)

- (8)

- Issues related to sexual assault, sexual health, and consent (The University of Sydney, Australia)

- (9)

- Cyber-security (Tecnológico de Monterrey, Mexico)

- (10)

- Multifaith chaplaincy (The University of Sydney, Australia)

- (11)

- Students’ stories from campus during COVID 19 (USA, UK, France, Spain, Latin America Universities, Russian universities)

- (12)

- Students’ polls (University of Cambridge, Russian Universities)

Details can be found on universities’ websites (see Appendix A and Appendix B).

The list reveals that the themes aim to balance learning issues in line with students’ societal inclusion (items 1 and 2), their individual situations, capacities, and needs (items 3–5). Other specifics specify the need to provide further career support (items 6–7), to ensure social wellbeing and security (items 8–9), to contribute to cultural identity support (item 10), and to focus specifically on students’ experiences and voices (items 11–12).

The data did not allow the study to identify significant variables related to the university affiliation to a particular region or country, to its position in the QS ranking system, and to an institution’s private/public status.

As far as the verbal means are concerned, Figure 1 shows that the major concepts are verbally expressed through nominative phrases organized from nouns and adjectives, and prepositions might appear as well. Syntactical density does not go beyond a three-member phrasal structure. At the level of the concept slots, a more specific structure also takes place. Along with verbal design, which is similar to that of the major concepts, some slots have a more dense syntactical structure (more items in the nominative line). Verbal nouns and adjectives reach 12.5% in the concepts and their slot structure.

3.2.2. Particular Comments with Respect to Discourse in Russian Universities

Compared with international communication practice, communication in Russian universities mirrors the same trends and percentage of activities related to education, information provision, campus facilities operation, and health service contacts. Students inclusion is limited to volunteering in the university and outside community, though this shows a comparable percentage of these activities mentioned in communication. Similar figures are revealed with regard to communication on human wellbeing, though the topics are limited to psychological recommendations and on-line cultural activities, and no comprehensive approach to mental health issues is found.

Nonetheless, it seems timely to underline that other configurations of selected universities, both foreign and Russian, might change the percentage landscape. Moreover, the comparative approach to the analysis has made it possible to highlight a number of features with respect to Russian universities’ discourse on their operation during COVID 19; these remarks are based on the official federal documents related to higher education institutions (HEIs) and Russian universities’ data on their websites. These features derive from the explicit nation-wide mandatory administrative-legislative regulation of university community activities by the Federal Ministry of Science and Higher Education. Further, we provide a number of particular comments to support the above statement with concrete examples.

Each university which was subject to study published on its web-site federal legislation and respective internal regulations (uploaded on each university site) that standardize the procedure and requirements for the education process, the faculty and student body’s activities, mid-term and final assessment, and admission procedure during the current pandemic. The COVID 19 sites of the universities’ platforms that were explored are linked to the Legislation section.

Second, it should be mentioned that the Russian Ministry of Science and Education took a consistent lead in guiding and monitoring the overall situation, as well as in making it public. The official YouTube channel of the Russian Federation Ministry of Science and Education streamlined and published video conferences during the lockdown period (from 16 March to 16 June) of the Russia-wide sessions under the Ministry’s umbrella. They were held with the mandatory engagement of all HEIs to monitor and coordinate activities and support students and staff [87]. The universities’ digital platforms provide a link to the ongoing information from the Ministry in their COVID 19 News section.

Further, under the Ministry’s recommendation each university (and even faculty, in case of a major federal university) has set forth a situation task force as a university/faculty-wide provisional division. This incorporated Vice-Rectors and heads of key departments. The unit had to foster and speed up inter-departmental communication and activities coordination, including education process administration, student and staff health condition monitoring and medical service provision in case of need, university infrastructure control, etc. [88]. The university platforms that were explored are linked to the page Situation task force division.

Under the Federal Ministry recommendations, the leading Russian universities supported other Russian universities across the country, sharing their digital educational resources with the overall Russian higher education institutions [89]. The COVID 19 sites of the university platforms that were explored are linked to the page Shared open access educational resources.

Similar to international universities’ practices, a particular emphasis was laid on students’ financial support during COVID 19. The Russian Federation Ministry of Education issued the order on student bursaries [90]. In line with this order, universities announced students’ right to lump-sum financial support through the universities’ contingency and labor unions funds. The information from Peter the Great Saint Petersburg Polytechnic University can be used as an example [91]. The COVID 19 sites of the university platforms contain a link to the page Ministry order on bursaries and information about university activities to implement it.

Further, the Ministry of Science and Education has initiated a program of support for students’ job placement [92]. The relevant recommendation was also made public on the university sites. Some universities provided concrete facts about the ways they used to put the idea into practice by recruiting students for university staff positions related to technical support for the digitalized education process, design of digital sources, etc. [93].

It also seems essential to mention that Russian university websites (73%) consistently publish students’ stories from the campus and even transmit these stories to the mass media and TV [94]. The respective data contributes to the downplaying of panic downplaying and the fostering of social confidence.

Another common trend in the Russian higher education landscape refers to students’ surveys. The Russia-wide service for public surveys conducted student surveys during the pandemic with regard to the quality of education during the lockdown period. 53% of students consider the quality of distance learning to be high, and 32% of respondents simply rate it as normal. Only 12% of university students complained about the low level of teaching during this period, sociologists say [95]. Universities themselves also launched student polls on their difficulties and the level of their satisfaction with the services provided. By 31 May 2020 19 out of 23 Russian universities under study had launched the respective surveys. The examples can be found on university websites [96,97]. Moreover, the analysis of Russian university websites reveals that the institutions tried to meet the language needs of international students. The data on health, education, campus services, social activities, and engagement in volunteering and research is provided in English, as well as Russian; moreover, some universities which lead in international student recruitment provide up-to-date communication in other foreign languages, for instance in Chinese, Spanish, and Portuguese, as can be revealed on the site of the Ural Federal State University [98].

On the other hand, the earlier mentioned sources [88] also confirm that the Russian government has acknowledged that the quarantine period became a stress-test for national digital educational platforms for higher education. The Russian Federal Minister of Science and Education specifically underlined insufficient technological capacity, acknowledged lack of open massive open online courses (MOOC) in university disciplines that are mandatory under federal state educational standards, and mentioned specific challenges to the learning process at technical, medical, and engineering faculties/institutions in terms of internships and lab-based research-led activities.

The above description of our findings from manual and digital content analysis of concepts that universities consistently verbalize in their communication on youth issues during COVID 19 leads to the following deliberations.

3.2.3. Discussion

The empirical data introduces university discourse on youth issues during COVID 19 as a system of verbally represented concepts and their constituent slots. This system thematically covers diverse areas of university activity related to youth support during COVID19. The concepts nominate the areas of university policies and activities and the slots name the tools for their implementation. Thus, it is possible to state that university discourse to support youth during COVID 19 operates as a cognitive communicative macrostructure. As this macrostructure integrates heterogeneous concepts and slots, it has a cognitive-communicative multidimensional nature which stems from different tasks (management, logistics, education, sanitation, social, communicational, etc.) that universities have to solve for the sake of youth sustainability support during COVID 19. Moreover, the slots that form the system of concepts verbally represent those tools that an institution uses to solve these tasks. Therefore, the conceptual communicative macrostructure of university discourse introduces university policies as a comprehensive system of tasks and tools to solve them. Consequently, the identification of the multidimensional macrostructure reveals the essence of the comprehensive role of university discourse in fostering youth sustainability in society in times of pandemic. Thus, the empirical data of Section 3.2 support research hypothesis statement 1 on the comprehensive nature of the university role in fostering youth sustainability during the current pandemic.

The next point in this discussion refers to research hypothesis statement 2. This underlines the role of verbal tools in the representation of the above-mentioned university comprehensive role. The empirical study has made it possible to compile a list of those verbal units that the university discourse uses to verbalize its policies in order to foster youth sustainability during COVID 19. The results show that the university discourse across the world uses a quite standard system of language units in terms of their meaning (described earlier in the section) and grammar forms (nominative phrases, limited number of items in the phrases).

Furthermore, the findings show that the macrostructure under study includes concepts of universal significance and concepts related to university’s specific values, verbally introduced through the respective language units. Thus, this research supports the idea of Zwaan [99] about generally accepted and context-dependent concepts with regard to the same subjects, and tailors the generalized idea of Van Dijk [32] on global structures in discourse, interaction and cognition to a new emerging area of communication, namely university discourse on youth issues during the current pandemic. The concepts identified in the course of the empirical analysis correlate with the conceptual background of the definition of youth sustainability, provided in the Introduction section. Therefore, the findings described in Section 3.2.1 and Section 3.2.2 support research hypothesis statement three that university discourse on youth sustainability can be introduced as a verbally expressed conceptual macrostructure of knowledge and action.

3.3. International Institutional Discourse on Universities’ Tasks amidst the Current Pandemic

This part of the paper provides findings with regard to research task three and aims to identify the verbally expressed concepts of international organizations’ policies and actions. The empirical study revealed some common features and topics of particular focus within discursive the conceptual-communicative macrostructure of various institutions. Therefore, these findings are introduced in Section 3.3.1 and Section 3.3.2. The results are further discussed in Section 3.3.3 in line with research hypothesis statements one, two, and three.

3.3.1. Common Features

The data on international organizations’ discourse on the university’s role during COVID 19 become a secondary source as international stakeholders provide recommendations and can even monitor their implementation. In line with variables mentioned in the description of Materials, the analysis of secondary source data took into account major genres. The sources, including their institutional affiliation, types of genre, and respective number of analyzed documents, are introduced in Table 2.

Table 2.

General profile of secondary source data with regard to the type of organization and documents issued. (Author’s data).

The thematic content analysis of the data highlights several trends. First, international organizations consistently engage in rapid response to COVID 19 through policy statements, analytical reports, surveys and interviews, applied tools, and solutions, to ensure the continuity and quality of education in general and that of university-based training in particular.

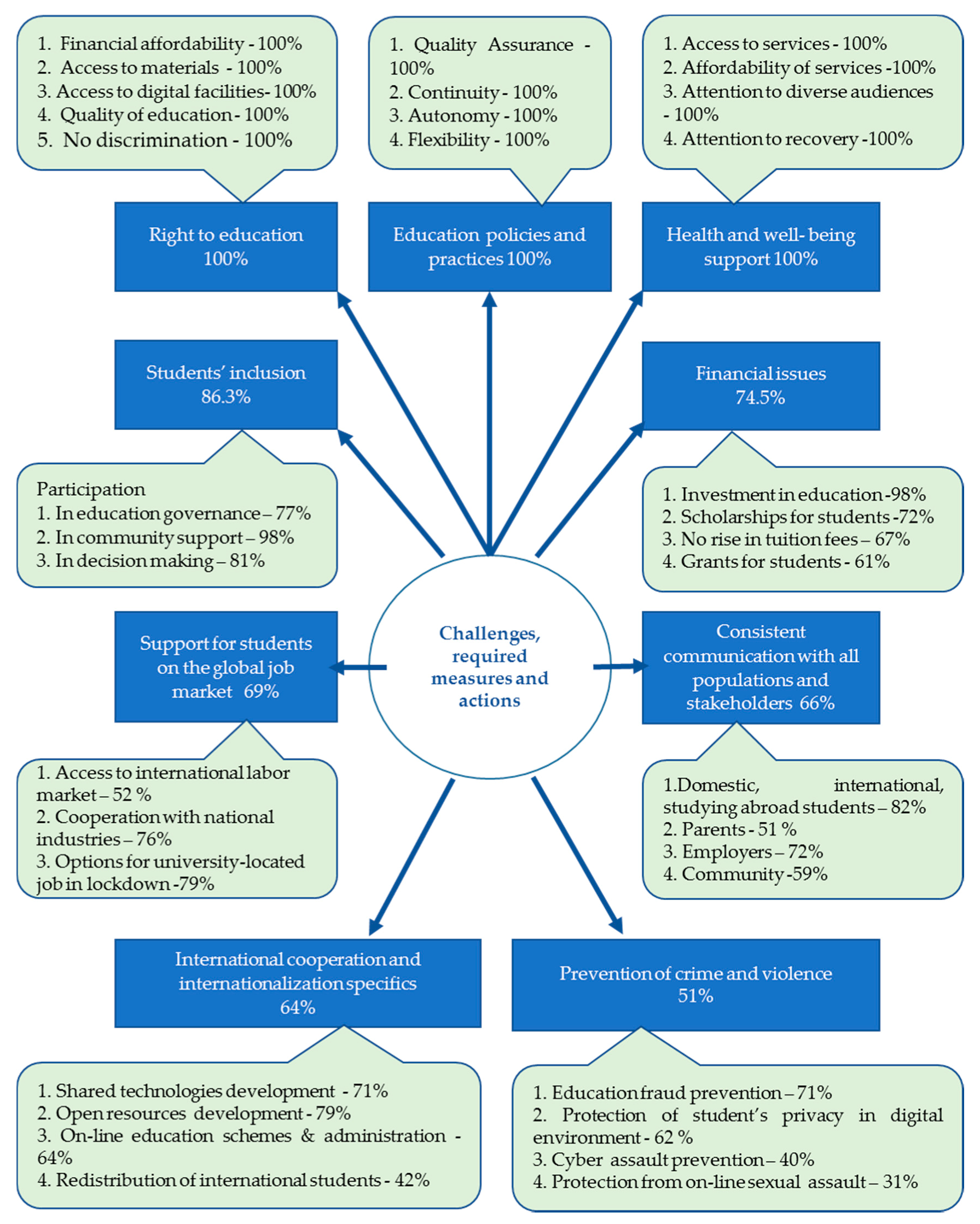

The study of the respective documents and tools makes it possible to specify major concepts and their constituent slots, introduced in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

Concepts and their slots within the phenomenon of international organizations’ discourse on higher education during COVID-19. (Author’s data).

The data reveals nine major concepts that appear in major international organizations’ discourse on universities policies’ and activities during COVID 19 (dark blue boxes). Only concepts whose proportion in the above data reaches at least 50% are mentioned.

The figure also marks the above concepts’ constituent slots (light green boxes).

Currently, 35 slots comprise the above concepts in international organizations’ communication practices. Due to organizations’ comprehensive/specific field of activities, all slots which were identified in the course of investigation are mentioned, even those whose presence in the textual data does not amount to 50%.

The analysis reveals that the list of these slots varies with respect to a specific organization. The most consistent list of such slots refers to the concepts of Right to education, Education policies and practices, and Health and well-being support. Communication in the other six areas reveals a lower percentage of distribution frequency of concepts’ constituent slots. However, as is the case with the investigation of university discourse, the absolute percentage figures of some slots within these concepts might be 15–20% higher than the average figures for the concept itself.

As far as verbal means are concerned, Figure 2 shows that the major concepts are verbally expressed through nominative phrases organized from nouns and adjectives; prepositions and conjunctions also appear. The syntactical density often goes beyond a three-member structured phrase. This density is even higher at the level of the concept constituent slots, 12% of which are formed of five to seven language units.

3.3.2. Topics of Particular Focus

In line with the research tasks, we consider it relevant to provide comments with regard to the above-visualized data and highlight some topics of particular focus that international organizations cover in their communications on university education within the current pandemic.

The UN Secretary-General has launched the UN Comprehensive Response to COVID-19 [100]. These statements and this position map the challenges, specify vulnerable and marginalized youth populations, call for actions, and list necessary measures. The issues of university education are mentioned regarding several dimensions, including the vision of the right to education as one of the fundamental values, the critical need for health support and service provision, acknowledgment of such challenges as the digital divide, disrupted learning and examinations, closure of extracurricular social activities, mental health issues, and financial burden [101]. UN-affiliated agencies specify the challenges and tasks regarding sustainable support for youth.

The SDG-Education 2030 Steering Committee has drafted recommendations that focus on the continuity of learning through all stakeholders’ inclusion and equity, and on exceptional support for teachers and students, underlining the critical role of government commitment to investments in education to tackle digital and economic divides. Specific attention is drawn to the issues of crisis sensitive education planning, alternative curricula, and distance learning plans to ensure remote learning quality. Particular emphasis is laid on counter-violence measures, and youth social and emotional wellbeing during the COVID 19 emergency [102].

The United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime has issued a number of documents, and the Statement on COVID-19 & Youth seems to be of particular relevance in terms of its multidimensional nature. This document focuses on the need to support fundamental youth rights amid the pandemic from the angle of youth protection from abuse and violence. These documents also underline the need to foster youth inclusion and participation in all aspects and phases of the response to COVID 19 [103].

The United Nations Population Fund explores the dimensions within which youth has been affected during the current pandemic and underlines the importance of working with and for young people during COVID 19 in such key areas as health protection, education opportunities, social and civil security, and engagement in community communication to mitigate risks [77].

UNESCO focuses explicitly on support for the learning process across the world amid global closure of educational institutions and the need for specific attention to disadvantaged students [104]. The organization launched a particular portal on education during COVID 19 to ensure the continuity of education through multidimensional efforts which target national ministers, teacher community, integrate national repositories of digital learning resources and learning management systems, integrate tools for psychological support for youth, and collect student voices from all over the world. Moreover, UNESCO issued a special call to ensure and foster learning and knowledge exchange and sharing through open educational resources (OER) to support teachers and students in tackling inequalities that disadvantaged populations face [105].

The Compact for Young People in Humanitarian Action (53 international organizations, with governmental and non-governmental members, to protect women’s and youth rights in emergencies) provides a comprehensive study of the situation for youth during COVID 19, exploring medical, social, educational and security challenges. This forum underlines the need for governments and communities to treat youth as systemic partners in all phases of the COVID-19 response, including work on community needs, information delivery and sharing, and protection from crime and violence [106].

The Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development [107] delivered a policy brief for education stakeholders based on a survey of youth organizations from 48 countries. The document considers COVID impact on youth, including mental health, education, and employment. The Organization further shapes recommendations for national governments to consider youth as a catalyst for resilient and inclusive societies, and to foster partnership between public governance agencies and youth associations to mitigate COVID 19 consequences and advance recovery measures.

The World Economic Forum considers stakeholders (educators, learners, policymakers and society at large) who engage in the search for solutions and decision-making process about the future of education, specifically the need for cooperation between developed and developing countries [49]. The institution draws particular attention to society’s need for academically justified ethical guidelines for health care professionals’ activities during the pandemic [108].

The World Bank education group provides a comprehensive response to immediate and long-term challenges, drafts recommendations in terms of university operation planning for short-term and medium-long term options, and explores specifics of the education process, including course refreshment and delivery, assessment, admissions, research, ICT quality, human factors (students, faculty, staff), administrative standards and regulations, funding, and international cooperation [109].

The international organizations that focus on particular areas of activity deliver theme-tailored messages. Thus, the World Health Organization highlights the need for non-pharmaceutical interventions to prevent and control the spread of infection in educational institutions, and the importance of attention to sexual and reproductive health [110]. The International Labor Organization outlines measures to prevent youth’s exclusion from the labor market [111]. The International Association of Universities takes a specific stance on monitoring and data accumulation. The association has launched a global survey on the impact of COVID-19 on HEIs. Its aim is to explore critical challenges that institutions confront, identifying possible solutions. Besides, this organization concentrates on international, regional, and national data accumulation concerning emerging responses, policies, recommendations, university initiatives, and promising practices [112].

The regional organizations advance their policies and actions along with global trends and tailor them to the regions and agencies specific to their area of activities.

The documents of the Council of Europe (CoE) focus on legal aspects and societal dimensions of HEIs’ performance during and after COVID 19. The Council underlines that universities have the duty of care to students, specifying the particular need for safeguarding students with special educational needs and for protecting vulnerable populations (i.e., refugees). The organization underlines legal responsibilities for the mental health of students, protection from cybercriminals, possible educational fraud, and outlines that on-line assessment should be secured in line with the right to privacy and without academic misconduct [113]. The CoE also considers issues of rights from such angles as academic freedom, HEI autonomy, and engagement of students, faculty, and staff. Moreover, CoE documents strongly emphasize that universities should be viewed as and perform their functions as “societal actors for the public good.” [114]. Finally, the CoE calls for attention to multilingual resources and students’ voices.

The European Students’ Union (ESU) that unites 46 National Unions of Students from EU universities provides data on students’ opinions revealed through surveys and consistently follows the issue of students’ rights provision [115].

The EDUCAUSE (international association for higher education technology, uniting the community of IT leaders, HEIs and individuals) focuses on educational services quality during remote work and on-line learning. The organization specifies the critical difference between scheduled and emergency on-line education, underlines the importance of effective campus response to education process planning within the latter situation, expresses its commitment to free and discounted resources dissemination, and provides recommendations to keep students engaged during remote learning [116].

The QS ranking agency focuses on university social engagement and provides examples of specific universities’ contribution to the community fight against the pandemic. The agency also provides varied data on graduates’ job placement and tactics employed to get hired during the current pandemic. Moreover, in line with the agency policies, it focuses on advice to students on university choice for on-line education during the 2020–2021 schooling year, provides analytics with regard to keeping students engaged during on-line learning, specifies differences between on-site and on-line learning, and considers the prospects of internationalization and changes in future education [117]. Furthermore, the agency conducts ongoing surveys to help and protect prospective domestic and international students, enrich academic policies and practices, and foster education continuity across the globe during COVID 19 [118].

The Times Higher Education World University Rankings mainly discusses the quality of distance learning, aims to forecast international cooperation formats, and voices the issue of student’s financial support [119].

The European Association for International Education (EAIE) emphasizes the need for consistent communication with different target audiences, including students on the campus, students studying abroad, student parents, information for the community on university societal initiatives, etc., and information for partner universities, industries and employers [120].

The above brief comments have been introduced to provide concrete examples of the themes which international organizations’ discourse covers concerning higher education during COVID 19.

In general, this section’s findings lead to the following discussion.

3.3.3. Discussion

The analysis of the above-mentioned international institutions’ communication lays the grounds for comments on the conceptual-communicative profile of international and regional organizations with reference to their variables, specified in the data collection description, namely themes and genres. As far as institutional documents’ variables are concerned the research has failed to draw a clear distinction among institutional communications depending on the agency’s international/regional status. The institution type (multidimensional/area focused) of activity influences the comprehensive/theme-tailored scope of the topics that are covered in the documents of both international and regional organizations. As far as the genre of the textual data is concerned, position/policy papers/statements, official briefs, guidelines and recommendations tend to provide a complex multidimensional vision of youth issues and tools for youth sustainability during the COVID 19. Meanwhile, analytical papers and interviews provide a narrower, topic-specific consideration. Finally, applied modules/resources/platforms cover links to specific training tools.

The findings reveal that international institutional organizations that focus on higher education policies and development consistently address the role of modern universities in ensuring youth sustainability during COVID 19. Their messages in the form of various documents are structured into the system of concepts and their constituent slots.

Similar to the discussion in Section 3.2, it is possible to state that international organizations’ discourse on the topic under study tends to cover diverse areas of policy, tools, and activities which are verbally represented through concepts and slots considered earlier in this part of the paper. The conceptual-communicative macrostructure and its verbal representation in secondary sources’ communication on the university’s role in supporting youth during the COVID 19 contributes to research hypothesis statements one and two on the comprehensive role that university discourse performs in fostering youth sustainability in society in times of pandemic, and the role of language in this role representation.

The findings show that this communication ensures complex representation of worldwide university efforts to provide youth sustainability in health emergencies within the global landscape. The data, which have been visualized in figures one and two with further discussion, provides verbally explicit structures of global university and international organizations’ discourse on university policies and practices during COVID 19, and shows that this discourse implements an integrated conceptual verbal phenomenon of knowledge and action. We also consider it relevant to mention that earlier research did not cover such a wide comparative scope in terms of the number of universities whose data were subject to study.

The data adds additional support for research hypothesis statement three on university discourse on youth sustainability as a verbally expressed conceptual macrostructure of knowledge and action. The findings of this part reveal that not only the discourse of primary sources (that of universities) but also the discourse of secondary sources (that of international higher education affiliated organizations) on youth issues during COVID 19 functions as a verbally expressed conceptual macrostructure of knowledge and action of the respective organization

What seems really interesting is some additional findings which were not thought about at the stage of research planning and emerged from the secondary sources data findings, which laid the ground for some comparisons and specific remarks.

The comments below are based on the comparative analysis of data in Figure 1 and Figure 2, in Section 3.2 and Section 3.3, respectively.

The present comparative study of communication topics made it possible to identify differences between universities and international organizations concerning their communication focus on youth issues during COVID 19, though we did not envisage such a task. First, the findings reveal that universities focus on current tactics to tackle current challenges, while organizations search for strategic solutions and tools to cope with COVID 19’s current and prospective challenges and negative consequences. As the visual and numerical data in Figure 1 and Figure 2 show, particular topics across university global communication flows refer to education, campus operations, students’ mental health, research role, and the university’s input into society’s fight against COVID 19. Meanwhile, international organizations’ communication on university activities during COVID 19 lays specific emphasis on the students’ right to education as a fundamental human value. This communication argues for a stronger focus on the need to tackle the digital divide and foster equity within remote learning, students’ engagement in all the phases of response to the pandemic, and post COVDI 19 recovery, with a consistent call for national governments to reinforce their commitment to the mentioned tasks.

4. Conclusions

The empirical findings and their discussion aimed to reach a research goal that consisted in specifying trends in international institutional and university discourse in relation to youth sustainability in society amidst COVID19, from the angle of the respective discourse conceptual communicative structure representation.

To this end, the study analysed current trends in academic studies related to the research topic, and explored international universities and organizations’ discourse across the world on youth issues amidst the current pandemic to identify verbally expressed concepts regarding policies and actions.

The study has provided a comprehensive analysis of academic research on the university’s role during the pandemics. The literature review shows that COVID 19 has led to increasing data on international education-related organizations and higher education institutions’ policies and activities during the pandemic. This state of affairs leads to the conclusion that academia should focus on a comprehensive analysis of higher education policies and performance concerning universities’ communication to foster youth sustainability in society during health emergencies and pandemics.

Further, the research findings confirm the hypothesis that university discourse can play a comprehensive role in fostering youth sustainability in society in times of pandemic. The empirical analysis and the discussion show that this role is explicitly introduced through the verbal communication of national universities and higher education organizations during COVID 19. This communication develops as a structured conceptual multidimensional discourse, which covers varied topics, and addresses them in an integrated way as interconnected and mutually dependent themes of the HEIs’ communication. We introduces different actors who engage in the provision of information and services, and take part in instrument development and implementation, with the view of addressing the need for support for youth sustainability from higher education institutions, national governing bodies, and international agencies in the relevant field.

The above-mentioned comprehensive role of university communication on youth sustainability operates as a conceptual communicative macrostructure through language means which verbalizes the macrostructure of knowledge and actions. The findings show that such a macrostructure unites concepts that are similar for both university and organizations’ discourse (education issues, information provision, campus operation, support for human beings, financial issues), on the one hand, and the concepts and their slots that differ. International agencies consider the university’s role in enhancing youth sustainability from the angle of students’ fundamental rights, focuses on societal dimensions of students’ status during and after COVID 19, and urges national governments to develop policies to ensure the above rights and status. Thus, communication on students’ inclusion incorporates different slots with respect to university discourse and organizational discourse, which considers this issue from a more comprehensive angle.

Moreover, the universities are still to follow international recommendations on consistent communication with different target audiences, including the domestic and international student populations, their parents, employers, and community.

Bearing in mind the above, it seems possible to shape preliminary recommendations on the expressed conceptual architecture of university communication to ensure youth sustainability through verbal discourse amidst the global pandemic.

The university should provide a comprehensive information response during health emergencies, ensuring consistent goals and result-focused communication among all the actors engaged both inside and outside the institutional space. It is critical to highlight university education policy as a complex system that in line with education quality maintenance ensures sustainable human well-being, rights, security, and students’ engagement and participation in university actions addressed to society. A clear message on university and national government readiness and capacity to implement concrete actions for students’ financial and career support are also critical.

Moreover, university communication to ensure youth sustainability during pandemics benefits from students’ polls and concrete stories related to learning, research, volunteering, and cooperation with industry representatives. Representation of students’ positive experiences during health emergency contexts contributes to downplaying misinformation, rumors, and panic in the community, and fosters an overall positive community vision and confidence in overcoming temporary challenges. The themes mentioned above, if consistently aggregated and explicitly verbalized in university communication during the pandemic outbreak, can contribute to youth sustainability at national and international levels.

The present study does not avoid some limitations related to source collection. Selection and integration of materials from other universities and international organizations, and enhancement of the respective pools of actors, might change the percentages of the verbal representations of concepts and their slots in the discourse under study. Therefore, further studies are expected to specify this data at both local national and international levels. Specific comparative analysis from the inside and cross-regional; perspectives bring new relevant data.

Funding

The publication has been prepared with the support of the RUDN University Program 5-100, research project number 090512-1-274.

Acknowledgments

The author expresses her deep gratitude to colleagues from the RUDN Law Institute department of Foreign Languages who kindly agreed to act as independent coders for the initial manual coding of the research data.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflict of interest.

Appendix A. Primary Sources Data. Universities across the World That Were Subject to Empirical Study

Table A1.

The data source: QS World University Rankings 2021 [46].

Table A1.

The data source: QS World University Rankings 2021 [46].

| No. | Region, No. of Countries/Country | University | Ranking | Site |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Africa, 2 | ||||

| 1. | South Africa | University of Cape Town | 220 | https://www.aucegypt.edu/ |

| 2. | South Africa | The University of the Witwatersrand | 403 | https://www.wits.ac.za/ |

| 3. | Egypt | American University of Cairo | 411 | https://www.aucegypt.edu/ |

| 4. | Egypt | Cairo University | 561–570 | https://cu.edu.eg/Home |

| Asia, 28 | ||||

| 5. | Singapore | National University of Singapore | 11 | http://www.nus.edu.sg/ |

| 6. | Singapore | Nanyang Technological University | 13 | https://www.ntu.edu.sg/Pages/home.aspx |

| 7. | China (Mainland) | Tsinghua University | 15 | https://www.tsinghua.edu.cn/kyzten/ |

| 8. | China | Wuhan University | 246 | https://en.whu.edu.cn/ |

| 9. | Hong Kong SAR | The University of Hong Kong | 22 | https://www.hku.hk/others/covid-19/overview.html |

| 10. | Hong Kong SAR | The Hong Kong University of Science and Technology | 27 | https://www.ust.hk/ |

| 11. | Japan | The University of Tokyo | 24 | https://www.u-tokyo.ac.jp/en/ |

| 12. | Japan | Kyoto University | 38 | https://www.kyoto-u.ac.jp/en/ |

| 13. | South Korea | Seoul National University | 37 | https://en.snu.ac.kr/ |

| 14. | South Korea | Korea University | 69 | http://www.korea.edu/ |

| 15. | Malaysia | University of Malaya | 59 | https://www.um.edu.my/ |

| 16. | Malaysia | Universiti Putra Malaysia (UPM) | 132 | https://upm.edu.my/ |

| 17. | Taiwan | National Taiwan University | 66 | https://www.ntu.edu.tw/english/ |

| 18. | Taiwan | National Tsing Hua University | 168 | https://nthu-en.web.nthu.edu.tw/bin/home.php |

| 19. | Saudi Arabia | King Abdulaziz University (KAU) | 143 | https://www.kau.edu.sa/home_english.aspx |

| 20. | Saudi Arabia | King Fahd University of Petroleum & Minerals (KFUPM) | 186 | http://kfupm.academia.edu/ |

| 21. | Kazakhstan | Al-Farabi Kazakh national University | 165 | https://www.kaznu.kz/en/ |

| 22. | Kazakhstan | L.N. Gumilyov Eurasian National University (ENU) | 357 | https://www.enu.kz/en/ |

| 23. | India | Indian Institute of Technology Bombay (IITB | 172 | http://www.iitb.ac.in/ |

| 24. | India | Indian Institute of Science | 185 | https://www.iisc.ac.in/ |

| 25. | Israel | The Hebrew University of Jerusalem | 177 | https://new.huji.ac.il/ |

| 26. | Israel | Tel Aviv University | 230 | https://english.tau.ac.il/ |

| 27. | United Arab Emirates | Khalifa University of Science and Technology | 211 | https://www.ku.ac.ae/ |

| 28. | United Arab Emirates | United Arab Emirates University | 284 | https://www.uaeu.ac.ae/en/ |

| 29. | Lebanon | American University of Beirut | 220 | https://www.aub.edu.lb/ |

| 30. | Lebanon | University of Balamand | 501–510 | http://www.balamand.edu.lb/home/Pages/default.aspx |

| 31. | Qatar | Qatar University | 245 | https://www.qu.edu.qa/ |

| 32. | Indonesia | Gadjah Mada University | 254 | https://ugm.ac.id/en |

| 33. | Indonesia | Universitas Indonesia | 305 | https://www.ui.ac.id/ |

| 34. | Brunei | Universiti Brunei Darussalam | 254 | https://ubd.edu.bn/ |

| 35. | Brunei | Universiti Teknologi Brunei | 350 | http://www.utb.edu.bn/ |

| 36. | Pakistan | National University of Sciences And Technology | 355 | https://www.nu.edu.om/default.aspx |

| 37. | Pakistan | Pakistan Institute of Engineering and Applied Sciences | 373 | http://www.pieas.edu.pk/ |

| 38. | Macao SAR | University of Macau | 367 | https://www.um.edu.mo/ |

| 39. | Macao SAR | Macau University of Science and Technology | 701–750 | https://www.must.edu.mo/en |

| 40. | Oman | Sultan Qaboos University | 375 | https://www.squ.edu.om/ |

| 41. | Philippines | University of the Philippines | 396 | https://www.up.edu.ph/ |

| 42. | Philippines | Ateneo de Manila University | 601–650 | https://www.ateneo.edu/ls |

| 43. | Turkey | Koç University | 465 | https://www.ku.edu.tr/en/ |

| 44. | Turkey | Sabanci University | 521–530 | https://www.sabanciuniv.edu/ |

| 45. | Iran | Sharif University of Technology | 409 | http://www.sharif.ir/web/en/ |

| 46. | Iran | Amirkabir University of Technology | 477 | https://aut.ac.ir/en |

| 47. | Jordan | University of Jordan | 601–650 | http://ju.edu.jo/home.aspx |

| 48. | Jordan | Jordan University of Science & Technology | 651–700 | http://www.just.edu.jo/Pages/Default.aspx |

| 49. | Bahrein | Applied Science University of Bahrain | 651–700 | https://www.asu.edu.bh/ |

| 50. | Bahrein | University of Bahrain | 801–1000 | http://www.uob.edu.bh/en/ |

| 51. | Kuwait | Kuwait University | 800–1000 | http://kuweb.ku.edu.kw/ku/index.htm |

| 52. | Kuwait | Kuwait University | 801–1000 | http://www.kuniv.edu/ |

| 53. | Iraq | University of Baghdad | 801–1000 | https://en.uobaghdad.edu.iq/ |

| 54. | Iraq | University of Kufa | 801–1000 | http://uokufa.edu.iq/?lang=en |

| 55. | Bangladesh | Bangladesh University of Engineering and Technology | 801–1000 | https://www.buet.ac.bd/web/ |

| 56. | Bangladesh | University of Dhaka | 801–1000 | https://www.du.ac.bd/ |

| 57. | Vietnam | Vietnam National University Ho Chi Minh City | 801–1000 | https://vnuhcm.edu.vn/ |

| 58. | Vietnam | Vietnam National University, Hanoi | 801–1000 | https://vnu.edu.vn/eng/ |

| 59. | Thailand | Chulalongkorn University | 208 | https://www.chula.ac.th/en/ |

| 60. | Thailand | Mahidol University | 252 | https://mahidol.ac.th/ |

| Europe, 29 | ||||

| 61. | United Kingdom | University of Oxford | 5 | http://www.ox.ac.uk/ |

| 62. | United Kingdom | University of Cambridge | 7 | https://www.cam.ac.uk/ |

| 63. | Switzerland | Swiss Federal Institute of Technology Zurich | 6 | https://ethz.ch/services/en/news-and-events/coronavirus.html |

| 64. | Switzerland | École polytechnique fédérale de Lausanne | 14 | https://www.epfl.ch/campus/security-safety/en/health/coronavirus-covid19/ |

| 65. | Germany | Technical University of Munich | 50 | https://www.tum.de/en/ |

| 66. | Germany | Ludwig-Maximilians-Universität München | 63 | https://www.en.uni-muenchen.de/index.html |

| 67. | Netherlands | Leiden University | 46 | https://www.universiteitleiden.nl/en |

| 68. | Netherlands | University of Amsterdam | 49 | https://www.uva.nl/en?cb |

| 69. | France | École Polytechnique | 61 | https://www.polytechnique.edu/en |

| 70. | France | Sorbonne University | 83 | http://www.sorbonne-universite.fr/ |

| 71. | Belgium | KU Leuven | 84 | https://www.kuleuven.be/english/ |

| 72. | Belgium | Ghent University | 135 | https://www.ugent.be/en |

| 73. | Sweden | Lund University | 97 | https://www.lunduniversity.lu.se/home |

| 74. | Sweden | KTH Royal Institute of Technology | 98 | https://www.kth.se/en |

| 75. | Ireland | Trinity College Dublin, The University of Dublin | 101 | https://www.tcd.ie/ |

| 76. | Ireland | University College Dublin | 177 | https://www.ucd.ie/ |

| 77. | Denmark | University of Copenhagen | 76 | https://www.ku.dk/english/ |

| 78. | Denmark | Technical University of Denmark | 103 | https://www.dtu.dk/english |

| 79. | Finland | University of Helsinki | 104 | https://www.helsinki.fi/en |

| 80. | Finland | Aalto University | 127 | https://www.aalto.fi/en/aaltosummer |

| 81. | Norway | University of Bergen | 194 | https://www.uib.no/en |

| 82. | Norway | University of Oslo | 113 | https://www.uio.no/english/ |

| 83. | Italy | Politecnico di Milano | https://www.polimi.it/en/ | |

| 84. | Italy | Sapienza University | 171 | https://www.uniroma1.it/en/ |

| 85. | Austria | University of Vienna | 150 | https://www.univie.ac.at/en/ |

| 86. | Austria | Vienna University of Technology | 191 | https://www.tuwien.at/en/ |

| 87. | Spain | Universitat de Barcelona | 183 | https://www.ub.edu/web/ub/ca/index.html |

| 88. | Spain | Universidad Autónoma de Madrid | 200 | https://www.uam.es/UAM/Home.htm?language=es# |

| 89. | Czech Republic | Charles University | 260 | https://cuni.cz/uken-1.html |

| 90. | Czech Republic | University of Chemistry and Technology, Prague | 342 | https://www.vscht.cz/?jazyk=en |

| 91. | Estonia | University of Tartu | 285 | https://www.ut.ee/en |

| 92. | Estonia | Tallinn University of Technology (TalTech) | 651–700 | https://old.taltech.ee/en |

| 93. | Belarus | Belarusian State University | 317 | https://bsu.by/en/ |

| 94. | Belarus | Belarusian National Technical University (BNTU) | 801–1000 | http://www.bntu.by/ |

| 95. | Portugal | University of Lisbon | 357 | https://www.ulisboa.pt/ |

| 96. | Portugal | University of Porto | 357 | www.up.pt |

| 97. | Lithuania | Vilnius University | 423 | https://www.vu.lt/ |

| 98. | Lithuania | Vilnius Gediminas Technical University | 651–700 | https://www.vgtu.lt/index.php?lang=2 |

| 99. | Greece | National Technical University of Athens | 477 | https://www.ntua.gr/en/ |

| 100. | Greece | Aristotle University of Thessaloniki | 571–580 | https://www.auth.gr/en |

| 101. | Hungary | University of Szeged | 501–510 | https://u-szeged.hu/english |

| 102. | Hungary | University of Debrecen | 521–530 | https://www.edu.unideb.hu/ |

| 103. | Poland | University of Warsaw | 321 | https://en.uw.edu.pl/ |

| 104. | Poland | Jagiellonian University | 326 | https://www.uj.edu.pl/en_GB/ |

| 105. | Bulgaria | The University of Sofia (St. Kliment Ohridski) | 601–650 | https://www.uni-sofia.bg/eng |

| 106. | Ukraine | V. N. Karazin Kharkiv National University | 477 | https://www.univer.kharkov.ua/en |

| 107. | Ukraine | Taras Shevchenko National University of Kyiv | 601–650 | http://www.univ.kiev.ua/en/ |

| 108. | Slovenia | University of Ljubljana | 601–650 | https://www.uni-lj.si/eng/ |

| 109. | Slovenia | University of Maribor | 801–1000 | https://www.um.si/en/Pages/default.aspx |

| 110. | Slovakia | Pavol Jozef Šafárik University in Košice | 651–700 | https://www.upjs.sk/ |

| 111. | Slovakia | Comenius University in Bratislava | 701–750 | https://medizinstudieren-slowakei.de/ |

| 112. | Latvia | Riga Technical University | 701–750 | https://www.rtu.lv/en |

| 113. | Latvia | Riga Stradins University | 801–1000 | https://www.rsu.lv/en |

| 114. | Romania | Babes-Bolyai University | 801–1000 | https://www.ubbcluj.ro/en/ |

| 115. | Romania | University of Bucharest | 801–1000 | https://unibuc.ro/?lang=en |

| 116. | Malta | University of Malta | 801–1000 | https://www.um.edu.mt/ |

| 117. | Croatia | University of Rijeka | 801–1000 | https://uniri.hr/en/home/ |

| 118. | Croatia | University of Zagreb | 801–1000 | http://www.unizg.hr/homepage/ |

| Latin America, 12 | ||||

| 119. | Argentine | Universidad de Buenos Aires | 66 | http://www.uba.ar/ |

| 120. | Argentine | Pontificia Universidad Católica Argentina | 326 | http://uca.edu.ar/es |

| 121. | Mexico | Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México | 100 | https://www.unam.mx/ |

| 122. | Mexico | Tecnológico de Monterrey | 155 | https://tec.mx/es |

| 123. | Brazil | Universidade de São Paulo | 115 | https://www5.usp.br/ |

| 124. | Brazil | Universidade Estadual de Campinas (Unicamp) | 233 | https://www.unicamp.br/unicamp/ |

| 125. | Chile | Universidad de Chile | 180 | https://www.uchile.cl/ |

| 126. | Chile | Pontificia-universidad-católica-de-Chile | 121 | https://www.uc.cl/ |

| 127. | Colombia | Universidad de los Andes | 227 | https://uniandes.edu.co/ |

| 128. | Colombia | Universidad Nacional de Colombia | 259 | https://unal.edu.co/ |

| 129. | Peru | Pontificia Universidad Católica del Perú | 432 | https://www.pucp.edu.pe/ |

| 130. | Peru | Universidad Peruana Cayetano Heredia (UPCH) | 701–750 | https://www.cayetano.edu.pe/cayetano/es/ |

| 131. | Uruguay | Universidad ORT Uruguay | 462 | https://www.ort.edu.uy/ |

| 132. | Uruguay | Universidad de Montevideo (UM) | 492 | https://www.um.edu.uy/ |

| 133. | Cuba | Universidad de La Habana | 498 | http://www.uh.cu/ |

| 134. | Cuba | Universidad Central “Marta Abreu” de Las Villas | 531–540 | https://www.uclv.edu.cu/ |

| 135. | Costa Rica | Universidad de Costa Rica | 571–580 | https://www.ucr.ac.cr/ |

| 136. | Costa Rica | Tecnológico de Costa Rica—TEC | 801–1000 | https://www.tec.ac.cr/ |