Making Use of Evaluations to Support a Transition towards a More Sustainable Energy System and Society—An Assessment of Current and Potential Use among Swedish State Agencies

Abstract

:1. Introduction

1.1. Case Description—Transformative Evaluation

2. Theoretical Framework

2.1. Use of Evaluations

2.2. Models of Use

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Focus Groups

3.2. Structured Interview Questionnaire

4. Results

4.1. Design, Conduct and Use of Evaluations and Facilitating Measures for Use

4.1.1. Design and Conduct

4.1.2. Models of Use

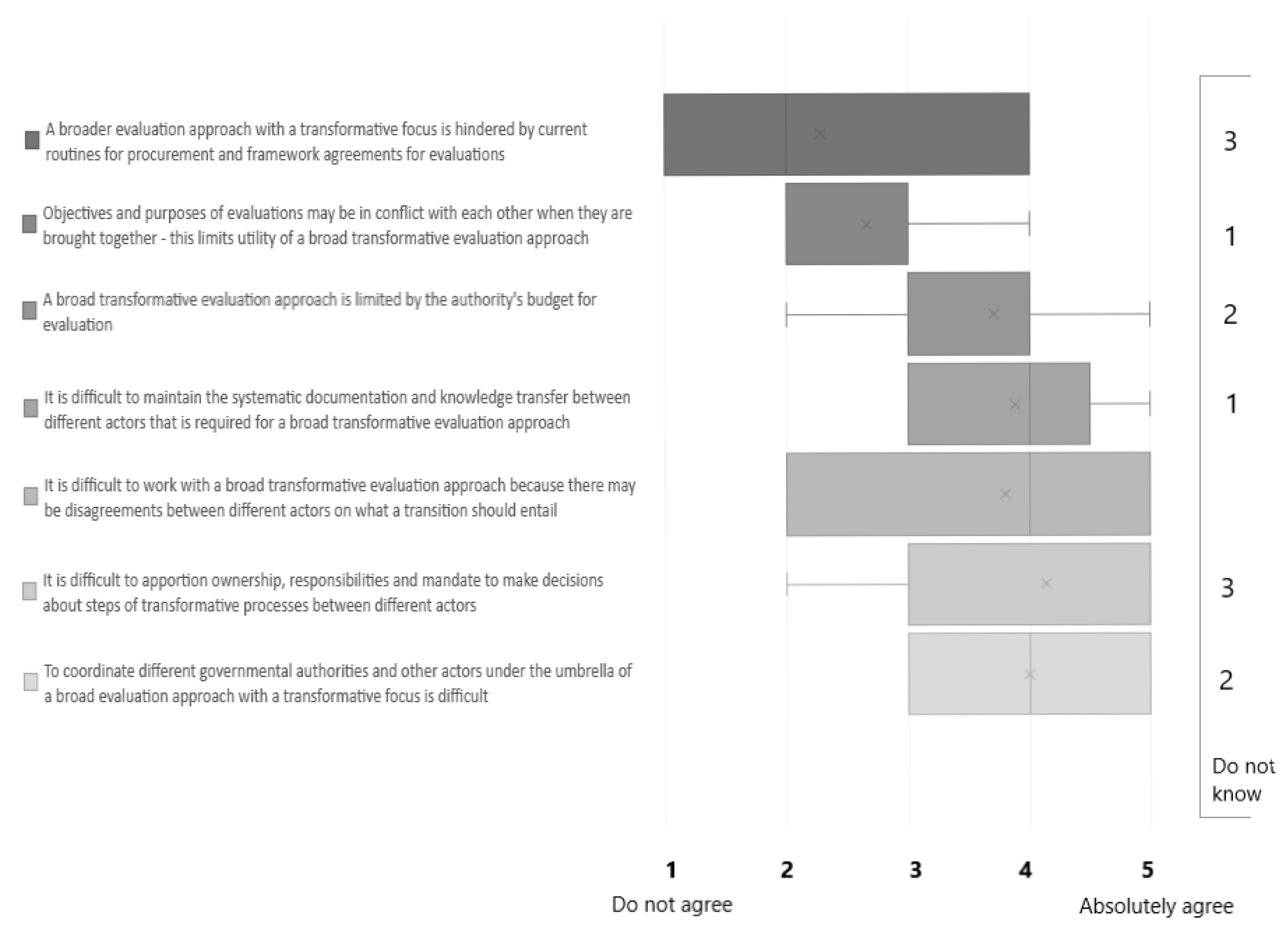

4.2. Benefits and Challenges of Transformative Evaluation

5. Discussion

5.1. Potential of Different Models of Use

5.2. Strengthening the Use of Evaluations

5.3. The Role of Framing Evaluations for a Transition

6. Conclusions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

- -

- The Swedish Energy Agency

- -

- The Swedish Environment Protection Agency

- -

- Growth Analysis

- -

- Vinnova

- -

- Formas

- -

- National Board of Housing, Building and Planning

- -

- The Swedish Agency for Economic and Regional Growth

- -

- Other (open answer)

- -

- I work strategically with issues related to evaluation

- -

- I commission evaluations

- -

- I conduct evaluations

- -

- Other (open answer)

- -

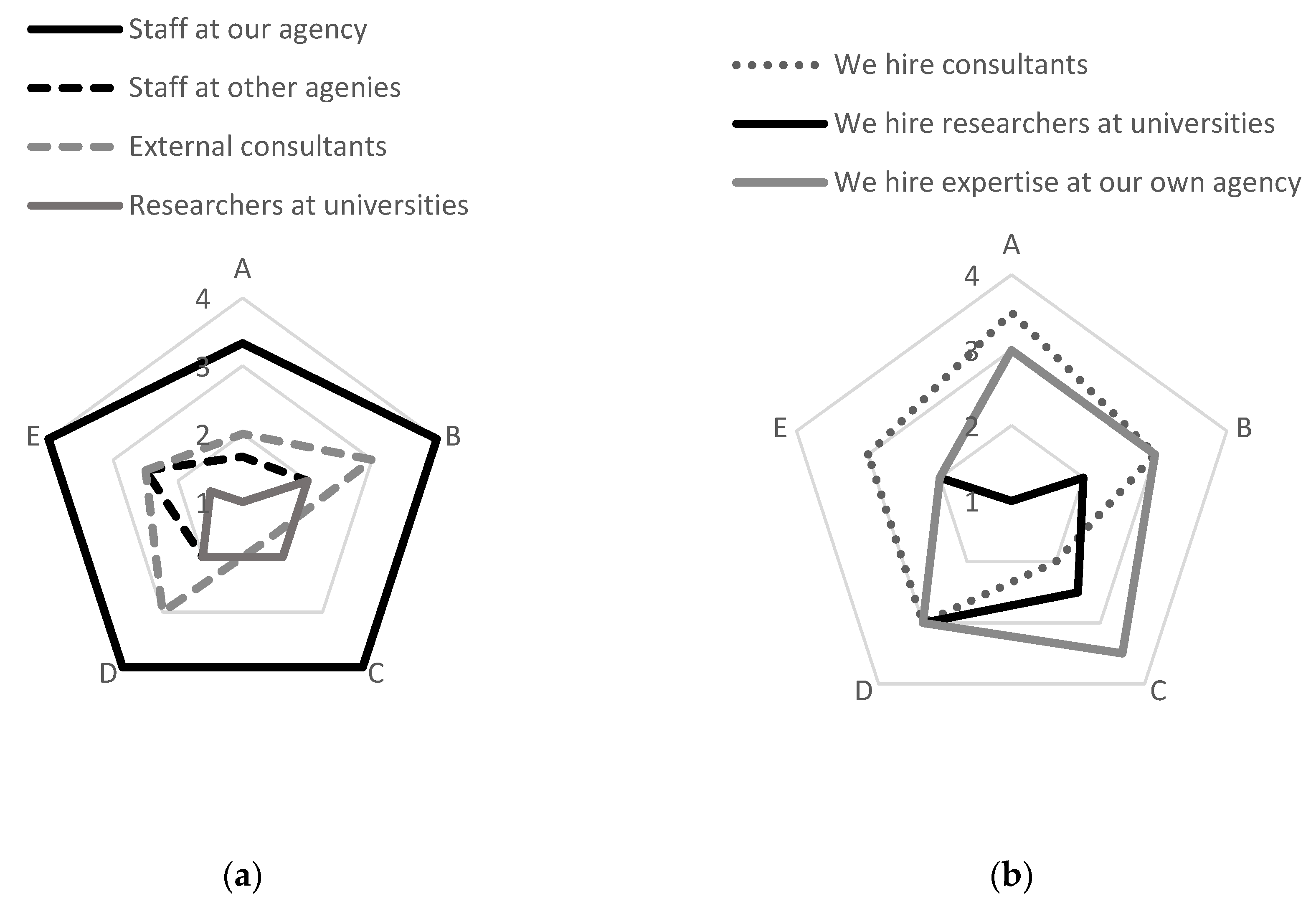

- Staff at our agency

- -

- Staff at other agencies

- -

- External consultants

- -

- Researchers at universities

- -

- Other (open answer)

- -

- We hire consultants

- -

- We hire researchers at universities

- -

- We hire expertise at our own agency

- -

- We hire others (open answer)

- -

- Evaluation expertise

- -

- Economics

- -

- Organizational theory

- -

- Behavioral expertise

- -

- Modeling expertise

- -

- We have the expertise needed within our own agency

- -

- Other (open answer)

- -

- The report is only distributed internally at our agency

- -

- The report is published on our agency’s webpage

- -

- The report is sent to other state agencies

- -

- The report is sent to municipal or regional agencies

- -

- The report is sent to those taking part in the evaluations; e.g., through interviews

- -

- We invite parties to an open seminar for discussing the evaluation

- -

- We broadcast the presentation of seminars online, where the evaluation is discussed

- -

- We arrange physical or digital meetings with those affected by the evaluation

- -

- Other (open answer)

Appendix B

| Model of Use | Characteristics |

|---|---|

| 1. Instrumental | Show how the evaluated program should be changed (Visa hur på det utvärderade programmet bör förändras) |

| Lead to immediate changes in the program that is being evaluated (Leda till direkta korrigeringar i det utvärderade programmet) | |

| Contribute to knowledge development that creates immediate measures for improvement in the evaluated program (Bidra till kunskapsuppbyggnad som skapar omedelbara förbättringsåtgärder i det utvärderade programmet) | |

| 2. Enlightenment/conceptual | Increase the understanding of how a program should be implemented, rather than lead to concrete measures in the program (Öka förståelsen för hur ett program bör genomföras snarare än att leda till konkreta handlingar) |

| Provide general knowledge about how a certain type of program works (Ge övergripande kunskap om hur en viss sorts program fungerar) | |

| Provide an overview of which aspects (e.g., administration, behaviour, economy, market) are affected by a program (Ge en överblick över vilka olika aspekter (t.ex. administration, beteende, ekonomi, marknad) som påverkas av ett program) | |

| 3. Legitimizing/Reinforcing use | Contribute to showing that we are doing things correctly (Bidra till att visa att vi gör saker rätt) |

| Give trust and support for decisions that concern a program (Ge förtroende och stöd för beslut som rör ett program) | |

| Confirm what we know about a research program or policy instrument (Bekräfta det vi vet om en forskningsinsats eller styrmedel) | |

| 4. Interactive | Be broad and robust enough to be the only basis for decisions regarding the evaluated program (reverse positive) (Vara bred och robust nog att utgöra det enda beslutsunderlaget för beslut om programmet.) |

| Only be one part of the knowledge basis in a decision process about a program (Endast vara en del av kunskapsunderlaget i en beslutsprocess om ett program) | |

| Be used in combination with other material in decision-making (Användas i kombination med annat material vid beslutsfattande) | |

| 5. Ritual/Symbolic use/Mechanical use | Be conducted to show that the program at hand has been followed-up on (Utföras för att visa att programmet i fråga har följts upp) |

| Be performed because it is expected that an evaluation is performed (Utföras för att det förväntas att en utvärdering utförs) | |

| Be conducted as per usual, so that actors affected by the evaluation will know what to expect (Utföras som vanligt, så att aktörer som berörs av utvärderingen vet vad som väntas) | |

| 6. Mobilizing use/Persuasive use | Be used to encourage actors to support a programme or a viewpoint (Användas för att uppmuntra aktörer att stödja ett program eller en ståndpunkt) |

| Be used to convince opponents (Användas för att övervinna meningsmotståndare) | |

| Be used to create support among others for the evaluated program (Användas för att skapa stöd hos andra för programmet) | |

| 7. Overuse | Focus on pre-determined criteria and indicators, regardless of whether the program or the situation has changed (Fokusera på förutbestämda kriterier och indikatorer, oavsett om programmet eller situationen har förändrats) |

| Be used for decisions about the program that are entirely based on what the evaluation shows (Användas för programbeslut som helt baseras på vad utvärderingen visar) | |

| Not put emphasis on describing why the results show what they show (Inte lägga stor vikt vid beskrivning av varför resultaten visar det som de visar) | |

| 8. Process use | Spur to change and improvement already during the evaluation process, through dialogues with different actors (Sporra till förändring och förbättring under utvärderingsprocessen genom dialoger med olika aktörer) |

| Primarily contribute with learning and knowledge during the evaluations process, through interactions between different actors (Främst bidra med lärande och kunskap under utvärderingsprocessens gång genom interaktionen mellan olika aktörer) | |

| Lead to important insights during the evaluation process (Leda till viktiga insikter i utvärderingsprocessen) | |

| 9. Constitutive/Anticipatory use | Realize effects as early as possible, before the evaluation itself is done (Få effekter så tidigt som möjligt, innan själva utvärderingen är klar. |

| Influence actors to consider what needs to be done to meet the expectations of the planned evaluation (Påverka aktörer att fundera över vad som behöver göras för att leva upp till förväntningarna av den planerade utvärderingen) | |

| Spur improvements in a program by communicating that an evaluation is to be done to those whom the evaluation concerns (Sporra till förbättring genom att den kommande utvärderingen kommuniceras till berörda aktörer) | |

| 10. Tactical use | Buy additional time in a decision-making process (Köpa ytterligare tid i en beslutsprocess) |

| Show that “something is being done” (Visa på att ’något görs’) | |

| Prevent hasty decisions, by allowing the evaluation process to take time (Förhindra förhastade beslut, genom att utvärderingsprocessen tillåts ta tid) | |

| 11. Unintended use | Spur further discussions about other programmes (Sporra vidare diskussioner om andra program) |

| Be used as a knowledge base to be used for issues that are outside of the evaluated program (Användas som kunskapsunderlag för frågor som står utanför det utvärderade programmet) | |

| Indicate areas outside of the evaluation boundaries that need further investigation (Påvisa områden utanför utvärderingens gränser som kräver ytterligare utredning) |

Appendix C

References

- European Environment Agency. Trends and Projections in Europe 2018: Tracking Progress Towards Europe’s Climate and Energy Targets; Publications Office of the European Union: Luxembourg, 2018; ISBN 978-92-480-007-7. [Google Scholar]

- International Energy Agency; Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development. World Energy Outlook 2018; OECD: Paris, France; IEA: Paris, France, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Masson-Delmotte, V.; Zhai, P.; Pörtner, H.-O.; Roberts, D.; Skea, J.; Shukla, P.R.; Pirani, A.; Moufouma-Okia, W.; Péan, C.; Pidcock, R.; et al. (Eds.) IPCC Global Warming of 1.5°C. In An IPCC Special Report on the Impacts of Global Warming of 1.5°C Above Pre-Industrial Levels and Related Global Greenhouse Gas Emission Pathways, in the Context of Strengthening the Global Response to the Threat of Climate Change, Sustainable Development, and Efforts to Eradicate Poverty; 2018; in press. [Google Scholar]

- Geels, F.W. Technological transitions as evolutionary reconfiguration processes: A multi-level perspective and a case-study. Res. Policy 2002, 31, 1257–1274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Farla, J.; Markard, J.; Raven, R.; Coenen, L. Sustainability transitions in the making: A closer look at actors, strategies and resources. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Chang. 2012, 79, 991–998. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Markard, J.; Raven, R.; Truffer, B. Sustainability transitions: An emerging field of research and its prospects. Res. Policy 2012, 41, 955–967. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weinstein, M.P.; Turner, R.E.; Ibáñez, C. The global sustainability transition: It is more than changing light bulbs. Sustain. Sci. Pract. Policy 2013, 9, 4–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Somanathan, E.; Sterner, T.; Sugiyama, T.; Chimanikire, D.; Dubash, N.K.; Essandoh-Yeddu, J.; Fifita, S.; Goulder, L.; Jaffe, A.; Labandeira, X.; et al. National and sub-national policies and institutions. In Climate Change 2014: Mitigation of Climate Change. Contribution of Working Group III to the Fifth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change; Edenhofer, O., Pichs-Madruga, R., Sokona, Y., Farahani, E., Kadner, S., Seyboth, K., Adler, A., Baum, I., Brunner, S., Eickemeier, P., et al., Eds.; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK; New York, NY, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- European Commission. Better Regulation Guidelines; [European Commission Staff Working Document]; European Commission, 2017; Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/info/sites/info/files/better-regulation-guidelines.pdf (accessed on 7 October 2020).

- Edler, J.; Berger, M.; Dinges, M.; Gok, A. The practice of evaluation in innovation policy in Europe. Res. Eval. 2012, 21, 167–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Edler, J.; Cunningham, P.; Gök, A.; Shapira, P. (Eds.) Handbook of Innovation Policy Impact; EU-SPRI Forum on Science, Technology and Innovation Policy; Edward Elgar: Cheltenham, UK; Northampton, MA, USA, 2016; ISBN 978-1-78471-184-9. [Google Scholar]

- Huitema, D.; Jordan, A.; Massey, E.; Rayner, T.; van Asselt, H.; Haug, C.; Hildingsson, R.; Monni, S.; Stripple, J. The evaluation of climate policy: Theory and emerging practice in Europe. Policy Sci. 2011, 44, 179–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Mela, H.; Hildén, M. Evaluation of Climate Policies and Measures in EU Member States: Examples and Experiences from Four Sectors; The Finnish Environment, 19th ed.; Finnish Environment Institute: Helsinki, Finland, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Schoenefeld, J.J.; Jordan, A.J. Environmental policy evaluation in the EU: Between learning, accountability, and political opportunities? Environ. Politics 2019, 28, 365–384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Højlund, S. Evaluation use in the organizational context–changing focus to improve theory. Evaluation 2014, 20, 26–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- King, J.A.; Alkin, M.C. The centrality of use: Theories of evaluation use and influence and thoughts on the first 50 years of use research. Am. J. Eval. 2019, 40, 431–458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Milzow, K.; Reinhardt, A.; Söderberg, S.; Zinöcker, K. Understanding the use and usability of research evaluation studies1,2. Res. Eval. 2019, 28, 94–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Patton, M.Q. Utilization-Focused Evaluation, 4th ed.; Sage Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2008; ISBN 978-1-4129-5861-5. [Google Scholar]

- Shulha, L.M.; Cousins, J.B. Evaluation use: Theory, research, and practice since 1986. Eval. Pract. 1997, 18, 195–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weiss, C.H. The many meanings of research utilization. Public Adm. Rev. 1979, 39, 426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weiss, C.H. Have we learned anything new about the use of evaluation. Am. J. Eval. 1998, 21–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chelimsky, E. A strategy for improving the use of evaluation findings in policy. In Evaluation Use and Decision-Making in Society: A Tribute to Marvin C. Alkin; Christie, C.A., Vo, A.T., Alkin, M.C., Eds.; Information Age Pub. Inc: Charlotte, NC, USA, 2015; pp. 73–90. [Google Scholar]

- Newcomer, K.E.; Hatry, H.P.; Wholey, J.S. Planning and designing useful evaluations. In Handbook of Practical Program Evaluation; Wholey, J.S., Hatry, H.P., Newcomer, K.E., Eds.; Jossey-Bass, Wiley: San Francisco, CA, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Shadish, W.R.; Cook, T.D.; Leviton, L.C. Foundations of Program Evaluation: Theories of Practice; Reprinted; Sage Publications: Newbury Park, CA, USA, 1991; ISBN 978-0-8039-3551-8. [Google Scholar]

- Alkin, M.C.; King, J.A. Definitions of evaluation use and misuse, evaluation influence and factors affecting use. Am. J. Eval. 2017, 38, 434–450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cousins, J.B. Commentary: Minimizing evaluation misuse as principled practice. Am. J. Eval. 2004, 7. [Google Scholar]

- Weiss, C.H. Evaluation: Methods for Studying Programs and Policies, 2nd ed.; Prentice Hall: Upper Saddle River, NJ, USA, 1998; ISBN 978-0-13-309725-2. [Google Scholar]

- Rossi, P.H.; Lipsey, M.W.; Freeman, H.E. Evaluation: A Systematic Approach, 7th ed.; Sage: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2006; ISBN 978-0-7619-0894-4. [Google Scholar]

- Vedung, E. Public Policy and Program Evaluation; Transaction Publishers: New Bruswick, NJ, USA, 1997; ISBN 978-0-7658-0687-1. [Google Scholar]

- Vedung, E. Six Uses of Evaluation; In Nachhaltige Evaluation?: Auftragsforschung Zwischen Praxis und Wissenschaft. Festschrift zum 60. Geburtstag von Reinhard Stockmann; Hennefeld, V., Meyer, W., Silvestrini, S., Stockmann, R., Eds.; Waxmann Verlag: Münster, Germany; New York, NY, USA, 2015; pp. 187–210. [Google Scholar]

- van Voorst, S.; Zwaan, P. The (non-)use of ex post legislative evaluations by the European Commission. J. Eur. Public Policy 2019, 26, 366–385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Fleischer, D.N.; Christie, C.A. Evaluation use: Results from a survey of U.S. American evaluation association members. Am. J. Eval. 2009, 30, 158–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ledermann, S. Exploring the necessary conditions for evaluation use in program change. Am. J. Eval. 2012, 33, 159–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cunningham, P.; Edler, J.; Flanagan, K.; Larédo, P. The innovation policy mix. In Handbook of Innovation Policy Impact; Edler, J., Cunningham, P., Gök, A., Shapira, P., Eds.; Edward Elgar: Cheltenham, UK; Northampton, MA, USA, 2016; pp. 505–542. [Google Scholar]

- Edler, J.; Fagerberg, J. Innovation policy: What, why, and how. Oxf. Rev. Econ. Policy 2017, 33, 2–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Martin, B.R. R&D policy instruments-a critical review of what we do and don’t know. Ind. Innov. 2016, 23, 157–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neij, L.; Sandin, S.; Benner, M.; Johansson, M.; Mickwitz, P. Bolstering a transition for a more sustainable energy system: A transformative approach to evaluations of energy efficiency in buildings. Energy Res. Soc. Sci. 2020, in press. [Google Scholar]

- Sandin, S.; Neij, L.; Mickwitz, P. Transition governance for energy efficiency-insights from a systematic review of Swedish policy evaluation practices. Energy Sustain. Soc. 2019, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Cook, T.D. Lessons learned in evaluation over the past 25 years. In Evaluation for the 21st Century: A Handbook; Chelimsky, E., Shadish, W.R., Eds.; Sage Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 1997; ISBN 978-1-4833-4889-6. [Google Scholar]

- Zraket, C.A.; Clark, W. Environmental changes and their measurement: What data should we collect and what collaborative systems do we need for linking knowledge to action? In Evaluation for the 21st Century: A Handbook; Chelimsky, E., Shadish, W.R., Eds.; Sage Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 1997; pp. 329–336. [Google Scholar]

- Alkin, M.C.; Taut, S.M. Unbundling evaluation use. Stud. Educ. Eval. 2002, 29, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Wholey, J.S. Use of evaluation in government-the politics of evaluation. In Handbook of Practical Program Evaluation; Wholey, J.S., Hatry, H.P., Newcomer, K.E., Eds.; Jossey-Bass: San Francisco, CA, USA, 2010; pp. 651–667. [Google Scholar]

- Leviton, L.C. Evaluation use: Advances, challenges and applications. Am. J. Eval. 2003, 24, 525–535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bryman, A. Social Research Methods, 4th ed.; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK; New York, NY, USA, 2012; ISBN 978-0-19-958805-3. [Google Scholar]

- Wilkinson, S. Focus group research. In Qualitative Research Methods-Theory. Method and Practice; Silverman, D., Ed.; Sage: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2004; pp. 177–199. [Google Scholar]

- Denzin, N.K. The Research Act: A Theoretical Introduction to Sociological Methods; AldineTransaction: New Brunswick, NJ, USA, 2009; ISBN 978-0-202-36248-9. [Google Scholar]

- Evans, J.R.; Mathur, A. The value of online surveys: A look back and a look ahead. Internet Res. 2018, 28, 854–887. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Weiss, C.H. The interface between evaluation and public policy. Evaluation 1999, 5, 468–486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Højlund, S. Evaluation use in evaluation systems–the case of the European Commission. Evaluation 2014, 20, 428–446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carnahan, D.; Hao, Q.; Yan, X. Framing methodology: A critical review. Oxf. Res. Encycl. Politics 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chong, D.; Druckman, J.N. Framing theory. Annu. Rev. Polit. Sci. 2007, 10, 103–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Entman, R.M. Framing: Toward clarification of a fractured paradigm. J. Commun. 1993, 43, 51–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Model of use | Characteristics |

|---|---|

| 1. Instrumental [27,28,29,30] | Evaluation findings are applied immediately for specific actions concerning the evaluand. |

| 2. Enlightenment/conceptual [27,28,29,30] | Evaluation findings are not used for the evaluand per se, but rather to provide insights about issues or implementations in general. |

| 3. Legitimizing/reinforcing use [27,29,30] | Evaluation findings are used to legitimize and justify decisions already made; e.g., to confirm current knowledge and beliefs, or support confidence in a standpoint. |

| 4. Interactive [20,29] | Evaluation findings form part of a larger decision-making process, where other sources of information and actors influence the decisions. |

| 5. Ritual/symbolic use/mechanical use [18,30] | Evaluations are conducted symbolically, because this is expected by current customs and practice, or evaluations are performed mechanically; evaluands seek only to fulfil requirements and get a good “score”. |

| 6. Mobilizing use/persuasive use [27,28] | Evaluation findings are used to create support for a particular standpoint, for mobilizing actors. |

| 7. Overuse [18] | Evaluation findings are put to use as definitive facts, without considering the contextual factors, or without exploring why certain outcomes have emerged. |

| 8. Process use [18,30] | The evaluation process in itself contributes with insights and learning and spurs action. |

| 9. Constitutive/anticipatory use [30] | An evaluation process spurs action and has impacts already in its initial phases by making evaluands and stakeholders aware of its coming into force. |

| 10. Tactical use [29,30] | Evaluations are conducted in order to postpone decisions, by showcasing that there is an ongoing evaluation. It is the process rather than the findings that are at the focal point of use. |

| 11. Unintended use [18] | Evaluation findings are used outside of an evaluated program; e.g., by spawning other investigations concerning issues separate from the program. |

| Benefits of Transformative Evaluation | Challenges of Transformative Evaluation |

|---|---|

| A new way of approaching evaluation | |

| Balances the requirements of smaller vs. more encompassing evaluations. Reduces stakes when evaluations become part of a bigger picture and gives room for experimentation. | Adoption requires change, which requires courage and acceptance from stakeholders. It does not harmonize with the current system for funding and the design of research and policy. Requires addressing current path dependencies. |

| Competency requirements | |

| The need for different evaluation competencies will be distributed more evenly. Less pressure on one stakeholder to host wide competencies. | A transformative approach requires the development of competencies by both commissioners and evaluators. |

| Evaluation planning and logistics | |

| The approach supports a pragmatic and deliberate planning of evaluation needs and calls for a connection between small-scale and large-scale evaluations. | The combining of evaluations of various scales into a more holistic picture means a continuous balancing of the need for details, the available data and the wider context. It is logistically challenging to involve many actors in an evaluation. |

| Knowledge transfer and documentation | |

| The evaluation approach supports a systematic documentation and logging of findings and insights, as well as a continuous knowledge transfer for learning between various evaluations and stakeholders. | The documentation and knowledge transfer required to execute the evaluation approach is challenging to realize. |

| Guiding | Ownership, agency and interests |

| A broader evaluation approach supports evaluation practices by being an inspiration, by maintaining ideas of what evaluation should (not) be and by assisting both evaluators and commissioners in providing a joint language for articulating expectations and designs. | A sustainability transition has stakeholders with vested interests, which calls for transparency and a continuous motivation for change. Issues to be resolved include the ownership of the evaluation approach and responsibilities and agency in managing such an approach. Responsibilities between levels such as units, agencies and state departments need to be determined. |

| Potential | Current procurement and commissioning routines |

| The approach highlights the transformational contributions of the evaluand and provides a possibility to identify drivers for change and how to support a sustainability transition. | There is a limited budget for evaluations, and commissions for evaluations are commonly limited to narrow requirements or are limited by what is allowed under a direct award. Master agreements may limit who can be commissioned to perform evaluations. There is a limited number of actors performing evaluations, which affects possibilities for variation. |

| Goals and purposes for evaluation | |

| A sustainability transition may have potentially conflicting goals on an aggregate level. Evaluations are static, but the purposes and goals (of a transition) may change. Previously set goals may become irrelevant. There may be a mismatch between what is stated in (old) policy documents and what should be evaluated according to a broader transformative approach. Currently, the purpose of evaluating is commonly to determine whether to legitimize a new program period. | |

| Current use | |

| The use of evaluations today is limited by various factors. | |

© 2020 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Sandin, S. Making Use of Evaluations to Support a Transition towards a More Sustainable Energy System and Society—An Assessment of Current and Potential Use among Swedish State Agencies. Sustainability 2020, 12, 8241. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12198241

Sandin S. Making Use of Evaluations to Support a Transition towards a More Sustainable Energy System and Society—An Assessment of Current and Potential Use among Swedish State Agencies. Sustainability. 2020; 12(19):8241. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12198241

Chicago/Turabian StyleSandin, Sofie. 2020. "Making Use of Evaluations to Support a Transition towards a More Sustainable Energy System and Society—An Assessment of Current and Potential Use among Swedish State Agencies" Sustainability 12, no. 19: 8241. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12198241