Abstract

The paper examines factors that support or obstruct the development of urban community garden projects. It combines a systematic scholarly literature review with empirical research from case studies located in New Zealand and Germany. The findings are discussed against the backdrop of placemaking processes: urban community gardens are valuable platforms to observe space-to-place transformations. Following a social-constructionist approach, literature-informed enablers and barriers for the development of urban community gardens are analysed against perceived notions informed by local interviewees with regard to their biophysical and technical, socio-cultural and economic, and political and administrative dimensions. These dimensions are incorporated into a systematic and comprehensive category system. This approach helps observe how the essential biophysical-material base of the projects is overlaid with socio-cultural factors and shaped by governmental or administrative regulations. Perceptual differences become evident and are discussed through the lens of different actors.

1. Introduction

Urban community gardens (CGs) provide a broad range of social, economic, environmental, and cultural benefits [1] resulting in an increased interest of policymakers, community organizations, and scholars. CGs can also be regarded as a steadily evolving socio-cultural phenomenon related to grassroots activism, urban transformations, and placemaking strategies. We acknowledge the broad spectrum of CG research and the numerous contributions that analyse gardens from different perspectives. However, despite a growing body of research, factors that support or obstruct the development of urban CGs are often mentioned incidentally in publications without being systematically analysed across cases. The paper addresses this apparent research gap by raising a central research question: which factors support or obstruct the development of urban CGs? The aim is to transfer existing knowledge about barriers and enablers into a systematic and comprehensive category system and to expand it by means of new empirical case studies.

Following Guitart, Pickering and Byrne [1], CGs are broadly defined in this paper as green spaces for mainly horticultural uses (e.g., vegetables and flowers), which are run by local communities in urban areas including communally and individually managed or rented plots of land. Due to a lack of detailed and differentiated information about development processes in many publications, “development” is used as a broad and inclusive term. It may include different development stages such as emergence/infancy, growth, decline, long-term development, etc.

1.1. Theoretical Conceptualisation of Placemaking

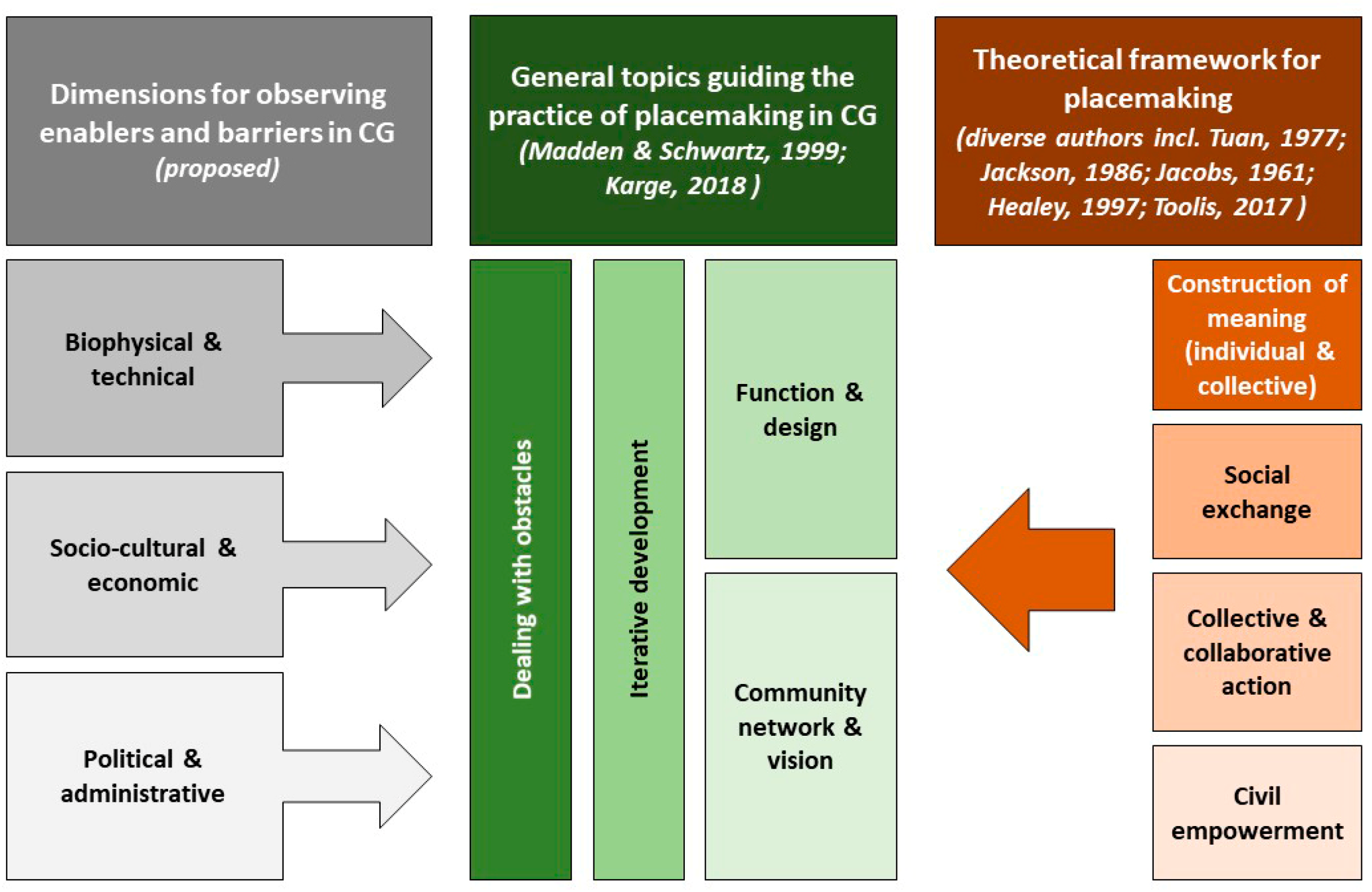

The academic and practice-informed literature on space and place(making) is vast, and while this study intends to enrich this discussion, it goes beyond its scope to test or expand existing placemaking theory. The following brief review of some key works of the space–place literature emphasizes four relevant aspects of placemaking theory: the construction of (individual and collective) meaning, social exchange, social (collective and collaborative) action, and (civil) empowerment (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Framework of discussion within the context of placemaking; Source: authors.

Following Tuan [2], notions of place are related to the subjective construction of reality as an embodiment of feelings and thoughts. This process of emotional attachment and assignment of meaning and value is crucial for the transformation of space to place: “What begins as undifferentiated space becomes place as we get to know it better and endow it with value” [2] (p. 6). The notion of “sense of place” is sometimes used to emphasize specific physical characteristics of geographical places [3]. It is also understood as a perception or feeling that makes a place special and unique, fostering human attachment that “develops gradually as we grow accustomed to it and feel that we belong there. It is something that we ourselves create” [4] (p. 6). This specific sense of belonging has been theorized in place attachment concepts emphasizing “the emotional bonds between people and a particular place or environment” [5] (p. 12).

Places are also locations for social exchange and activities that may result in collective constructions of meaning: “Conceptions of ‘place’ are social constructs, interweaving the social experience of being in a place, the symbolic meaning of qualities of a place and the physicalness of the forms and flows which go on in it” [6] (p. 269). Seminal publications in the planning and design field have sought to explain why some public spaces work and others fail to become places for community and social exchange [7,8,9]. While the works of such key thinkers focused mainly on the development or improvement of physical elements or structures according to people’s needs and behaviours, a new focus on democratic decision-making and active involvement of diverse stakeholders has evolved. For example, the extensive work of Patsy Healey emphasizes the value of collective effort to transform spaces into living places. She helped introduce the idea of “collaborative planning” [10] as a relevant concept of contemporary planning theory [11].

1.2. Placemaking Practice

Following this democratic ideal, placemaking has become a meaningful and widely absorbed concept. Placemaking and resulting interventions can be regarded as strategies for nurturing social and spatial diversity [12], promoting participatory design approaches, and improving “lived space” for a wide range of users [13]. Toolis [14] further explored the potentials of placemaking as a tool and strategy for civil empowerment and coined the term “critical placemaking”, referring to the act of reclaiming public space affected by privatisation. Critical placemaking derives from theoretical considerations but builds on and interacts with practical work—the practice of placemaking. The Project for Public Spaces (PPS) is a nonprofit organisation dedicated to helping people create and sustain public spaces that build strong communities. It acts as a central hub of the global placemaking movement and aims at connecting people to ideas, resources, expertise, and partners. It was founded in 1975 to expand the work of William Whyte about “The Social Life of Small Urban Spaces”. PPS has completed projects in more than 3500 communities in over 50 countries and acts as an umbrella organisation for placemaking practice. It bridges the gap between theoretical aspects of space and its transformation into meaningful place at individual project levels and by formulating principles and objectives for constructing public spaces [15].

Drawing on project experiences, Madden and Schwartz [16] formulated several principles for placemaking. In the context of CGs, Karge [17] summarised these in the form of four general topics: community network and vision (relation of different stakeholders in gaining knowledge and developing the place), function and design (functionality for the people versus design objectives), iterative development (precedence of a step-by-step process of testing and implementation), and dealing with obstacles (handling of constraints in relation to power and resources). To sum up, the recent discourse on placemaking theory focuses on an interplay of physical factors, socio-cultural perceptions, and collaborative planning and mind-sets. Next to the above-discussed relevant aspects of placemaking theory, these general topics of placemaking practice serve as a framework of discussion in this paper (Figure 1).

1.3. Community Gardens as Placemaking Platforms

CGs can serve as valuable platforms for observing phenomena of space-to-place transformation, as they reflect community and cultural values as well as public aspirations. In the context of our research question, we focus on observations of perceived barriers and enablers in CGs but discuss findings in the broader context of placemaking.

Karge [17] argues that CGs can be regarded as placemaking schemes—although rarely planned with placemaking instruments—as they are neighbourhood-orientated, multifunctional in use and a meeting point for diverse people. CGs mirror dialectic relationships between realms of the public and the private, and of the planned and the unplanned [18]. Local communities become attached to CGs and report positive experiences of sense of place and belonging [19,20]. While placemaking strategies usually focus on topics that guide the practice of placemaking [3,7] and build on theoretical considerations about construction of meaning, social exchange, collaborative action and civil empowerment [8,10,12,14,20], little is known about factors that hinder or impede placemaking in action. This paper aims at shedding light on enablers and barriers in CGs in their role as placemaking platforms (see Figure 1) and proposes general dimensions for systematisation and future research, which are adaptable to theoretical conceptualisations of placemaking (Section 1.1) and placemaking practice (Section 1.2).

Gaining a deeper understanding of supporting or obstructing factors in the development of urban CGs and related perceptions held by different stakeholders can be beneficial for placemaking discourses in urban planning and design. Even though professional planning is rarely actively involved in the establishment and development of CGs, designers and planners “have a role in place-making, in generating enduring meanings for places which can help to focus and coordinate the activities of different stakeholders and reduce levels of conflict” [6] (p. 217). Knowledge about group-specific perceptions of barriers and enablers in CGs are needed in a strategic and collaborative approach towards placemaking that aims at identifying individual conceptions of places to develop a common language of trust and understanding. This is a crucial part of reducing levels of conflict [6] and dealing with obstacles [17].

2. Research Method

The study combines an extensive literature review and empirical research in the form of qualitative key informant interviews. The broader geographical scope of the literature review establishes the contextual background and empirical framework of the study. The narrower geographical focus on New Zealand and German case studies as much as the thematic focus on barriers and enablers fills a gap in the scholarly literature. A recent literature review [1] revealed a geographical research gap with regard to the availability of internationally visible scholarly publications from both countries.

The paper defines supporting or obstructing factors as follows: enablers are factors that help improve or facilitate the development of a specific CG. These do not include benefits or positive outcomes of gardens or global aspects of urban agriculture, even though these might affect the motivation of participating stakeholders. Barriers are factors that impede or obstruct the development of specific CGs. These do not include general socio-critical considerations.

While the above definitions are useful to identify barriers and enablers in literature and cases, barriers and enablers are not considered “objective” in a positivist sense. They are based on the descriptions of different actors influenced by perceptions and possibly diverging values. Thus, the paper follows a post-positivist constructivist perspective that acknowledges perceptual differences in the identification and interpretation of barriers and enablers. Biophysical and technical enablers and barriers could be analysed (in a more positivistic sense) during the establishment or maintenance of CGs, e.g., when brownfields are transformed into garden projects and specific material limitations or benefits occur. However, CGs are also socio-cultural phenomena that go beyond people’s endeavours of communal food growing. Factors regarding the social-cultural realm of CGs can neither be observed nor analysed in a comparable way. Thus, this paper incorporates a social constructivist lens that focusses on the creation of reality and the way individuals view their world. Building on Berger and Luckmann [21], social constructivism describes reality as a socially constructed process which is related to the influence of individual meaning against the backdrop of life experiences, societal und cultural expectations, as well as rules and norms. In the context of landscape-orientated research, social constructivism has been used as a framework in order to explain culture or group specific preferences for landscapes and the use of symbols like words, rules, and roles in order to assign meaning to physical-material structures as well as to make sense of the world [22,23]. Against the backdrop of the presented framework for placemaking, the paper argues that focusing on the construction of (individual and collective) meaning, social exchange, social (collective and collaborative) action, and (civil) empowerment, CGs are essentially related to the “social formation and symbolic landscape” [24]. Thus, barriers and enablers are likely to be affected by individual or group specific perceptions and related garden experiences as well as societal und cultural expectations. For this reason, context sensitive interviews have been conducted to complement the literature review (Section 2.1). The interview data aim at providing more detailed group specific information for perceived or socially constructed enablers and barriers in the selected case studies (Section 2.2).

2.1. Literature Review

A systematic literature review was conducted to identify barriers and enablers to the development of urban CGs. A systematic literature review can be explained as “a research method and process for identifying and critically appraising relevant research, as well as for collecting and analysing data from said research” with the aim to “identify all empirical evidence that fits the pre-specified inclusion criteria to answer a particular research question” [25] (p. 334). The literature review responds to the (sub-)research question: Which barriers and enablers in CGs are addressed or identified in the scholarly literature?

Papers selected for the literature review were English language publications, original research, and papers published in peer-reviewed academic journals. The search was restricted to papers from the five leading countries with regard to community garden research: the United States, Australia, Canada, the United Kingdom, and South Africa [1] (p. 365). These countries belong to the so-called Anglosphere with a relatively consistent geographic scope in terms of language, cultural values, and the societal context of gardening. In addition, we included our two case study countries (Germany and New Zealand). Keyword searches adapted from a previous systematic literature review [1] were used, including “community garden(s)” as the main search term, plus a combination of related keywords (“space”, “green“, “gardening”, “school”, “urban”, “food production”, “land use”, “place”, “planning”, “agriculture” and “people”). Papers found in the keyword searches were checked manually against the selection criteria. Papers that did not meet all selection criteria were discarded (e.g., review papers, commentaries, or papers that focused on rural or backyard gardening). Search results were triangulated against the Guitart, Pickering and Byrne [1] review.

A total of 170 papers were found (published between 1985 and November 2016) using the Web of Science and Google Scholar databases. The content analysis focused on information regarding barriers and enablers. Information on barriers and enablers was included in 103 papers (Table 1; sorted by countries based on the location of case studies).

Table 1.

Papers that include information on barriers and enablers sorted by countries.

A total of 200 enablers and 199 barriers were identified (Table 6). Concepts with similar meaning or similar effects were grouped. Enablers and barriers were categorized through an inductive coding process. The resulting categorization system was not predetermined but iteratively constructed through the coding process, including several stages of reduction, modification, and verification through our empirical data. Each modification stage was discussed, monitored, and reviewed by the authors until a final categorization system was established (Tables 3–5). The main dimensions of the suggested category system (biophysical and technical, socio-cultural and economic, and political and administrative) were, one the one hand, formed inductively and iteratively. On the other hand, they reflect relevant aspects of the placemaking discourse.

2.2. Case Studies

The paper focuses on case studies from New Zealand and Germany. In our literature search no relevant papers from New Zealand and only a few German studies were found despite the tradition and popularity of CGs in both countries. The case study approach responds to two (sub-)research questions: which barriers and enablers—as identified by the literature—can be confirmed in CGs in Germany and New Zealand? How do perceptions of barriers and enablers differ between community gardeners and external experts?

The case studies are gardens in Christchurch, New Zealand, and in five German cities (Aachen, Düsseldorf, Essen, Hannover, and Kassel). The selected cities are growing centres of regional importance with populations between 100,000 and one million. The individual garden projects are diverse with regard to the local geography (central city and suburban), lifespans (temporary and permanent), and state of development (infancy and well established).

Since the 1990s, a new community gardening movement in Germany has expanded the traditional urban gardening landscape of allotment gardens (Kleingärten). While allotments are regulated by a national act (Bundeskleingartengesetz) concerning design and use and integrated in binding zoning plans, there is no legal framework for new CGs (Gemeinschaftsgärten) [129,130]. About 640 projects (January 2019) are established throughout Germany, most of them with an explicit social and ecological agenda [131]. The gardens are often considered as social projects for (intercultural) communication, integration, and community building at the neighbourhood level. Local councils and administrations support a growing number of gardening projects, recognizing them as having a positive societal and environmental impact [129,132]. In New Zealand, CGs are popular and numbers have increased since the 1970s [133]. Due to cultural and historical circumstances (colonial and post-colonial), New Zealand has been identified as “a unique breeding ground for community based gardening projects” [134] (p. 12). There are approximately 150 CGs in New Zealand’s three largest cities [135], including 29 CGs in the greater Christchurch area [136]. The establishment of CGs is partly regulated under the Reserves Act 1977 [137] and often supported by local governments through CG policies. Christchurch City Council developed CG guidelines to “clarify roles, responsibilities and processes for creating and running community gardens on Council land” [138] (p. 1.).

The design of the study carefully incorporates specific sets of selection criteria for the garden projects as well as for the interview partners. According to literature, cases can be selected for paradigmatic, extreme, or critical reasons [139]. The selected CGs can be regarded as critical cases. They correspond with the theoretical frame of the presented paper. Individual garden projects were selected on the basis of their potential for observing space-to-place transformations in terms of construction of meaning, social exchange, collective action and civic empowerment, and different types of governance approaches, including interactions between local stakeholders, political and administrative support or professional help [132]. Furthermore, the incorporated CGs are characterized by barriers and enablers, which are perceived differently by involved gardeners or external experts. The case study approach is neither designed for a specific comparison between CGs in Germany or New Zealand nor does it aim at generalising case specific knowledge. However, some obvious differences with regard to national planning cultures emerged during data analysis. They are discussed briefly in the discussion section.

The case study design is used, on the one hand, to support the literature analysis and to expand the knowledge base regarding garden projects in Germany and New Zealand. On the other hand, the cases shed light on perception gaps between gardeners and external experts that could not be extracted solely from the literature. Due to the incidental character of information on barriers and enablers in the scholarly literature, their detailed context cannot be reconstructed. The cases are a complementary tool to illustrate differences in reporting specific enablers and barriers between gardeners and external experts. The presented case studies represent already established garden projects. There might be other barriers at early stages of individual garden projects that were not addressed in this research. A systematic analysis of factors that may lead to the failure of CGs might be subject for future research.

Semi-structured qualitative interviews (n = 30) were conducted with key informants in New Zealand and Germany between October 2013 and August 2017. The interviewees were CG representatives with an intrinsic knowledge and expertise of their respective gardens (short: community gardeners; CG 1–14) and external gardening experts (short: external experts; EX 1–16) from municipalities, government, and NGOs (Table 2). The sampling strategy for selecting interview partners included a mix of different techniques. During the first steps, gatekeepers like garden coordinators and umbrella organizations like the Canterbury Community Gardens Association were contacted in order to find possible interview partners. Contacts were established by personal encounter as well as by mail request. The gatekeeper sampling was applied in order to purposefully address persons with expert knowledge and important positions in CG networks. These persons usually provided additional contacts, so that snowball sampling was applied in a second step to approach other gardeners and external experts.

Table 2.

Key informants—garden experts (CG) and external gardening experts (EX)—from New Zealand and Germany.

Questions were implemented in order to understand the participants´ backgrounds, including the history of the CG, the different roles of participants, and the relationship of initiatives and public authorities. For the scope of this paper interviewees were asked to identify factors that support or impede the development of CGs. Interviews were recorded and transcribed; relevant citations from German interviews were translated into English. The transcripts were analysed to identify information on barriers and enablers regarding implementation and management of CGs. The three proposed dimensions in this paper (see Figure 1) reflect a fine-grained analysis of individual statements. Usually, interview partners revealed very detailed information about perceived barriers and enablers. These individual statements were organized in spreadsheets and grouped according to similarities following the categorisation system established by the literature review. Whenever the existing categorisation system was not able to appropriately accommodate newly identified barriers and enablers, the system was modified and extended. During this process, it became obvious that specific themes were related to each other. This led to the identification of dimensions that combine biophysical and technical, socio-cultural and economic, as well as political and administrative aspects. This inductive approach can be regarded as a major outcome of the paper.

3. Results

In this section, findings from the literature review and case studies are presented together. The identified barriers and enablers are discussed with regard to three dimensions in a systematic and comprehensive category system: biophysical and technical, socio-cultural and economic, and political and administrative. These dimensions are inductively and iteratively formed through our research process.

3.1. Dimension 1: Biophysical and Technical Barriers and Enablers

Growing food or ornamental plants in urban CGs depends on the biophysical and technical qualities of the dedicated gardening areas and the surrounding environment. However, their influence on the success of the individual garden project cannot be easily determined. Other factors such as group dynamics and motivation of the gardeners often overcast underlying biophysical-material conditions. We encountered a total of seven enabling and obstructing factors, which we divided into two categories—(1) biophysical, ecological, and topographical factors; (2) technical infrastructure, facilities, and equipment—equally reflecting findings from both literature and cases (Table 3). All barriers and enablers identified in the literature were verified by our case study research. Two particular enablers (beneficial soil conditions; beneficial microclimate and weather conditions) were identified in our cases but not in the literature.

Table 3.

Biophysical and technical barriers and enablers.

3.1.1. Biophysical, Ecological, and Topographical

This category describes biophysical and ecological aspects, including soil or microclimate conditions. Furthermore, spatial aspects like location and orientation of the gardens, as well as the spatial distance between a garden and the gardening community have been considered.

Pests are a problem in urban gardens. They reduce productivity and yield of the crop plants as gardeners may lack knowledge of interrelationships between crops and animals [102] or because of insect pests [94]. In our case studies, pests were mentioned once as a barrier in a New Zealand garden (CG7). As a response, the garden coordinator changed management processes.

Many urban CGs are part of vacant land conversion strategies. Therefore, poor quality or contaminated soil was identified as a major barrier in both literature and case studies. Managing the risks of contaminated soils has become an important topic in garden planning and management and relies on toxicological testing and soil conditioning methods. Uncertainties and difficulties of growing plants in contaminated soil were mentioned frequently in the literature and regarded as a significant risk in urban gardening [46,55,62,80,81,94,106,115,120]. Similarly, in eight of our cases inadequate or contaminated soil was identified as a barrier: “[…] probably the most common constraint is contaminated land and that might be contaminated by a cemetery or by landfill or by a chemical” (EX7). Good soil, on the other hand, was regarded as an enabler by two gardeners (CG7; CG14).

Inadequate microclimate or weather conditions were each identified as a barrier [56,105], including the unpredictability of the local weather [74] and inadequate sunlight or wind conditions [81,82]. In one of our cases, the lack of sunlight was identified as a barrier: “[It] took a couple of years to realize that it is so badly shaded here, and this is the reason why there is not much growth here” (EX16). Two interviewees identified benefiting microclimate and sufficient sunlight as enablers and highlighted the right location and spatial orientation of the garden.

The spatial distance between a garden and its community is a crucial aspect for participation and group dynamics. The literature identified gardens as disadvantaged that were far away from existing gardening communities or unknown to potential new gardeners [34,44,48]. Generally, a desirable location close to the community was considered as an enabling factor [34,52,53,57,61,62,81,82] with walking distance between a garden and the gardening community as the ideal case [70]. In two of our cases (CG7 and CG14) spatial distance and a general lack of accessibility were confirmed as barriers. Nine gardeners and six external experts stressed the fact that a desirable location of garden close to the community was necessary for a successful and sustainable garden: “[…] for the sustainability of such a project is it important that a, if possible direct spatial link exists. This means that the participants are living nearby the area” (EX9).

3.1.2. Technical Infrastructure, Facilities, and Equipment

This category describes the materiality of resources. Availability and access to technical infrastructure, facilities, and equipment includes each of three enabling and obstructing factors derived from the literature. All of them were confirmed by our case study research.

The reliable supply of water and electricity is important to meet basic needs of garden projects; the lack of them was considered as a particular barrier [55,56,70,74,94,105,120]. In eleven of our cases (nine enablers; two barriers), gardeners and external experts emphasized that reliable water and electricity supplies including technical measures such as drilling wells, laying water lines, and installing water taps were essential: “Thanks to a very active member of the board we are lucky and the local water supplier sponsors our water supply, including a standpipe” (CG8). The lack of access to basic equipment and facilities for a proper (long-term) operation of gardens was considered as a barrier by the literature [56,70,74,94,105], including garden sheds, workshops, or toilets [34]. Access to equipment and material resources (e.g., storage facilities, tools, mulch, compost, fertilizer) that facilitate crop management and the maintenance of the garden [39,70] was mentioned as an enabler. In seven of our cases such enablers, and in four cases corresponding barriers were confirmed: “We need to have the area defined probably by some form of fencing and we probably need a building of some sort even if it’s a prefabricated one where we can store tools” (CG1).

As a drawback of public accessibility and openness of the CG to a wide range of people [71], the physical and material effects of theft and vandalism were identified as barriers [55,56,61,62,89,101,104,121]. In seven of our cases, theft and vandalism were regarded as barriers for community gardening: “Vandalism occurs quite often here, because the area is so open” (CG11).

3.2. Dimension 2: Socio-Cultural and Economic Barriers and Enablers

As expected, barriers and enablers related to socio-economic aspects dominated both in the literature and our cases. A total of 17 socio-cultural and economic enabling and obstructing factors were identified and categorized as (1) individual, (2) group- or gardening-community-related, (3) neighbourhood-related, (4) knowledge-, skills-, and information-based, and (5) economic and financial (Table 4). Most literature-based barriers and enablers were confirmed by our cases; however, often differently weighted and revealing characteristics that have not been subject to discussion so far.

Table 4.

Socio-cultural and economic barriers and enablers.

3.2.1. Individual

In the literature, individual factors do not play significant roles as barriers or enablers to community gardening. Only two sources identified passion and self-motivation as enablers [65,67]. In contrast, 19 of our interviewees regarded passion and motivation as enablers:

“Community gardens start off with great idealism, maybe there’s younger people here a bit transient actually even though they feel totally committed for one season or two seasons but somebody like Peggy who has been there for 20 years lives two doors away and just is totally committed to holding this space, that is rare”.(EX5)

Other individual factors such as the physical strength to carry out garden activities were identified as enablers in the literature [111] but in none of our cases. A lack of time to work in the garden may be an individual barrier [28,34,44,74,118], confirmed by four of our cases. Other identified individual barriers reported in the literature include a lack of health [44], experienced violence [106], and identity-related issues with regard to stakeholders [117].

3.2.2. Group or Gardening Community

The literature identified six enabling or obstructing factors in this category (Table 4). Our cases confirm the relevance of group-dynamic processes for the success or failure of CGs. The literature mentions conflicts regarding leadership and governance as barriers, including a lack of community leadership [43,86,118,119]; conflicts between gardeners and steering committees [71]; governance issues [35,37,53,99,104]; organisational, coordination, or management issues [32,67,74,105,128]; internal communication issues [50,105]; and a lack of control due to an powerful outside organisation [119]. In contrast, only three of our interviewees (CG1; CG7; CG10) reported such conflicts as barriers.

Ten publications highlighted supportive governance structures as enabling, including adequate forms of governance and administration [35,36,67,86]; dedicated leadership [77,95,126]; a steering committee or motivated core group [49,71]; and professionalization tendencies [50]. In 19 of our cases, enabling forms of governance were reported, such as leadership or a core group that has the organizational overview, the existence of rules, or the commitment of volunteers. In two German interviews only, the status of a formal association was considered relevant for the stability of the garden.

The perceived importance of a collectively shared vision as an enabler for a garden was reported by two authors [67,85] and in 14 of our cases:

“Amongst yourselves you need to have a shared vision and probably that’s really where it starts is the seed, the idea, what are we going to do, how is this going to work, how is this going to function, who is going to benefit, how is going to run it?”.(EX7)

On the other hand, different expectations or visions [71] were considered as barriers resulting from conflicting agendas between gardeners [65], diverging priorities or competitive action between different actors [90], new gardeners [48], and ownership or equipment [58]. With eight recorded accounts, diverging visons or conflicting agendas represent also the most frequently mentioned social barrier (together with conflicts with neighbours) of our cases. In three New Zealand cases, interviewees mentioned specific barriers arising from diverging expectations between generations and imbalances between invested working hours and claimed produce:

“From time to time we do have people who want to come and get something for nothing, they say ’can we have some vegetables?’ Well, we have a principle here that is sweat equity, that you work and then you get the vegetables, so you don’t just come and […] get it for free […]”.(CG3)

The literature shows that a sense of community was perceived as one of the most important enablers. Joint social activities [48,107]; community trust and cohesion [60,92,103,126]; common access to information [105]; low hurdles for participation [35,36]; and regular meetings [74,86] supported positive feelings in the gardens [66]. This was confirmed in 19 of our cases:

“For this reason, it is absolutely important to not just focus on gardening but to also do other tasks and activities together, like cooking. […] We always say that we also garden together but we do social things together as well”.(CG8)

In the context of community building, the importance of providing appropriate facilities for social exchange has been emphasised [65,98], such as providing spaces for social events [85] or safe and enjoyable outdoor spaces for children [53]. This issue was confirmed in eight of our cases:

“It’s a lovely spot and people around here bring their children, children like to play around the stream in the trees, you come here at 3pm and you will always see young girls and boys sitting at those tables, it just creates a community spot”.(CG1)

Other interviewees mentioned the need of providing space to live out one’s own creativity and suggested a good mix of public and private space. A lack of commitment, interest, continuity, and participation were identified as barriers in the literature, for example in the form of a lack of interest in steering committee work [71]; difficulties to maintain continuity and commitment, including management tasks [65,128]; or a lack of volunteer participation and help [50,74]. In five of our cases, this barrier was identified:

“I always wish that more people would come, that more people would join on a long-term basis and take over more responsibilities or at least feel more responsible”.(CG8)

On the other hand, having sufficient participants in the form of volunteers [105,126] or paid professionals, including professional gardeners [84,85,126], was identified as an enabling factor in 15 papers. Eight New Zealand and two German interviewees supported this view.

The literature considered the participation of diverse community members and stakeholders as an enabling factor [27,32,36,38,42,51,65,81]. Notions of diversity included a multicultural environment [26], the integration of new community members, including migrants [78], and a certain ratio of experienced and inexperienced gardeners [75] or ages [95]. The relevance of diversity was shared by twelve of our cases:

“The volunteers are so diverse, we have from 85-year-olds down to our youngest […] see that little bubby with his mum now? […] I’ve got people who come for all different reasons […]”.(CG4)

“I would regard it [garden] as successful if it provides opportunity for interaction that those people otherwise would not have because that random interaction with other people does a huge amount in terms of increasing trust in the community, of feeling of belonging, of sense of wellbeing, and all of that just because you’ve dug some carrots or whatever”.(EX8)

However, diversity was also considered as a possible barrier. Socio-cultural, political, racial, or ethnic conflicts between gardeners were found in the literature [39,44,52,71,113,117] and occurred in three of our cases.

“We have a very big variety of people, there’s Valentino from the Ukraine and there’s Belinda from China, we have Marsha from Slovenia—so sometimes political issues […]”.(CG5)

3.2.3. Neighbourhood or Local (Residential) Community

Involving local communities [43,48] and making a garden publicly accessible for neighbourhood residents [51,71,126] were identified as enabling factors in the literature. Eight of our interviewees supported this perspective:

“The group […] is very open to communication, even towards criticism. They always say that they will listen to it and offer [detractors] to join in, trying to explain their stance”.(EX9)

Negative relationships or conflicts with neighbours [36] were reported as barriers, including social, cultural, racial or class-related problems [71,89]; garden smells and noises [110,118]; different expectations or visions between gardeners and neighbours [71]; concerns about public health issues [120]; or lack of interest in or missing awareness of garden projects by the neighbouring residential community [49,74,105,128]. Potential conflicts with neighbours, especially in terms of perception gaps about aesthetic issues, were mentioned by eight of the German interviewees but in none of the New Zealand cases. Two informants reported a lack of interest in or awareness of garden projects by the neighbouring community. The German cases emphasized the importance of taking care for a good relationship with the neighbours:

“The garden neighbours […] that is a very good and important contact. It would not be possible when the neighbour causes a bad mood, especially in this plot-like situation”.(CG14)

Obstructing issues raised by seven interviewees and a few literature sources [33,43,86,90] are particular attitudes or garden policies that exclude local residents from participating in the garden. Interviewees especially from Germany discussed the contradiction between public space use and private appropriation:

“And that is often the contradiction in which we stand, because it should still be a public green space, on the other hand one can also understand the desire for a certain privacy”.(EX10)

Nine papers highlighted the importance of connections to local or social networks, including shared experience through (established) local collaborative partnerships [77,93,105,126,128] or umbrella organisations [98]. This was also addressed by twelve of our interviewees, including monthly meetings of gardeners belonging to various CGs (EX16), consultancy for weed control (EX4), or using existing networks for exchange and support (CG7).

In five New Zealand cases and two German cases interviewees assumed that CGs contributed to making the neighbourhood a better safer place.

“It has a civilising effect. In this area well over 60% of the population would be in rental accommodation so we have this terrific turn of people coming through all the time and this acts as a sort of anchor for the community”.(CG5)

This perspective was shared in five reviewed papers [53,58,71,85,115].

3.2.4. Knowledge, Skills, and Information

Disseminating and sharing of knowledge and skills through teaching, training, and tutoring was the most commonly mentioned enabler in the literature, mentioned in 24 papers, including teaching community members how to garden [26,40,51,53,56,72,80,81,120] including ecological processes and organic gardening [68,94]; building up technical, organisational, and managerial capacities [54,67,93,120,126]; sharing skills [36,58,109,126] including those coming from other cultures [31,64]; multi-lingual training [120]; education for schools and kindergartens [75,86] and cooking classes [68]. The relevance of disseminating skills and knowledge related to a garden was confirmed in our cases by eleven gardeners and four external experts: “[…] we started a course called ‘Grow Your Own Free Lunch’ which has made all the difference in our community garden” (CG2).

Eight scholars recognised that a lack of knowledge, gardening skills, or appropriate training was detrimental to a garden [41,50,67,68,70,91,94,122,128]. Two interviewees (CG10, EX11) confirmed this. In addition, language barriers were identified as a particular cultural barrier [26,39,45,58]. This barrier was confirmed in two German cases (CG12 and CG13).

While a few sources in the literature discussed the importance of good public relations and marketing and the role of social media for the gardens [49,71,74,75,95,126], this was regarded as an enabler in eleven interviews:

“What we have […] is communication in a WhatsApp group. This has the advantage that all participants are permanently informed”.(CG14)

The absence of public relations, information, or marketing strategies was considered as a barrier in three papers [44,105,120] and three of our cases.

3.2.5. Economic and Financial

Sixteen papers identified financial constraints, including a lack of secure permanent funding or a dependence on public funding [36,53,64,65,75,106,107,117,120,122] and limited financial public resources [43,86,106,128], as a barrier. On the other hand, having access to funding was the second most relevant enabling factor in the literature. Ongoing funding strategies [67]; diverse pathways to access funding, including donations [56,70,84,98,107]; financial support by umbrella organisations [54]; nonprofit status [93]; and even community-based participatory research [95] were considered as enablers. Funding or the lack of it was also considered as enabler or barrier in 19 of our cases—predominantly from New Zealand:

“They [city council] provide a little bit of funding which isn’t a lot really … we are partly funded by trusts and donations so we are funded by different people who give little bits of money to help keep it all going”.(CG 7)

Selling produce as a strategy for financing garden maintenance costs of paid stuff was subject in one garden from New Zealand (CG3) only, but not subject in the literature.

Fees, insurance, and maintenance costs were predominantly discussed as barriers [36,43,44,56,68,71,73,89,108]. This perspective was shared by two German cases. In one case, a specific issue was raised that had not been discussed in the literature before. It regards increased public maintenance resulting from the establishment of CGs:

“I have to listen to the complaints of [city council] colleagues … claiming that they have more work to do than before because they have to provide soil, lawns are dug up and vegetables are planted so everything gets weedy, the vegetable patches are run down and they have to restore the lawns”.(EX 9)

3.3. Dimension 3: Political and Administrative Barriers and Enablers

CGs are subject to political decision-making and administrative procedures. In the literature as well as in our cases such aspects play a crucial role. We encountered six enabling and obstructing factors within three categories: (1) land use and land tenure; (2) spatial politics, policies, and practices; and (3) local governments and administrations (Table 5). All literature-based factors were confirmed in our cases.

Table 5.

Political and administrative barriers and enablers.

3.3.1. Land-use and Land Tenure

The availability of and access to land [55,56], including land donations [74] and a relaxed real estate market [52], were considered as enabling factors in four papers. Sixteen literature sources regarded the lack of availability or access to land suitable as major barriers. Suitable gardening land in cities was considered as a scarce resource [41,64,67,68,107,128], including a high uncertainty about access to such land [74,94,105]. Considered reasons for this unsatisfying situation were competing demands for vacant land [120], particularly related to new housing development [49,79], and a lack of protection against booming real estate markets, commercial interests, or gentrification issues [71,75,76,86]. Accordingly, 14 of our cases confirm the availability of and access to land as an enabler or barrier respectively:

“The hard thing about entry barriers to getting a community garden started […] is the availability of land and whether it’s private land or whether it’s Council land”.(CG7)

While nine papers considered long-term tenure as an enabler [42,46,58,59,63,67,101,110,118], authors also discussed related barriers including the legal status of garden land, its use and tenure rights, and a lack of formal contracts [35,43,76,85,86,103,106,110]. The long-term perspective is of particular importance as many gardening projects are starting as interim-use with provisional and/or non-formal lease agreements and no security on the projects’ futures [30,41,49,51,56,83]. Twenty-one of our cases gave accounts of how (in)security over long-term land use affected community gardening projects:

“We don’t know if it’s long term because Anglican Living might say well you can’t have that land we’re going to build something else on here or we’ve sold this land to the people, […] so it’s only a temporary garden”.(CG2)

3.3.2. Spatial Politics, Policies, and Practices

Spatial politics, policies, and practices affect CG development in various ways and have been analysed with regard to two factors, starting with the foundations of a socio-political context and then focussing on planning systems, regulations and policies (Table 5). The socio-political context encompasses basic guiding principles (values, orientations, attitudes) of a society and political decisions corresponding with them [67,117]. Five papers reported on enabling contexts, particularly related to beneficial land-use policies and land management [29,30,36,83,100]. Twelve papers focused on barriers related to (the contestation of) neoliberal systems [43,49,53,90,116] and inequalities and injustices regarding economic [71], environmental [107], or general socio-political and power-related dimensions [49,90]. Other barriers included political problems in the government [106], institutional racism [91], and conflicts with public open space users [49,83]. In eleven of our case studies, barriers and enablers were found related to the general socio-political context. However, the context was often indirectly addressed through policies and actions rooted in a (non-)supportive milieu or a general distrust in political agendas.

On the meso-level of spatial planning and development, barriers and enablers address issues around planning systems, regulations, and policies. Enablers were identified in 12 of our cases and in 10 papers including supportive legislation and land-use planning [36,75], and urban regeneration or renewal strategies that lift the status of a garden [30,51,100,106]. Our case analysis confirms that political support and co-planning at an operational level between gardening initiatives and public administration may enable projects and clarify (legal, organisational) issues:

“Such projects have to be co-planned with the administration from the very beginning. And so there are always quite a few things that have to be taken into account with properties […] external people can’t even know”.(EX14)

The literature identified regulatory barriers and zoning restrictions that outline CGs as a form of land use unable to fit traditional green space typologies [37,67,117,120,122] and this could be confirmed in five of our cases. Other barriers, as identified in our cases, refer to the complexity and long duration of bureaucratic procedures and the financial framework of public administrations:

“I would say that the ’normal’ residents in the district have no idea how administration works. And when you then say: ’I would like to have a garden’, that it can sometimes take two years until you have checked everything, until you have carried out soil investigations, until you have permits […]”.(CG13)

3.3.3. Local Governments and Administrations

Factors in this section address the various ways political and administrative actors think and act. The term “Actors’ relations” refers to the support and good relationships of gardening projects to local governments, administrations, and authorities. It is one of the most often mentioned enabling factors in our cases as well as in literature. Actors’ relations include the encouragement [33] and actual political decision-making over land-use and land tenure in favour of CGs [75], as much as the provision of funding, staff, technical support, materials, training, or other resources [36,43,58,105,117]. Although the operative support is mostly provided through administration and public authorities, it depends on political support as well as politics to set the material and non-material framework: “The one thing is support by the administration, but political support is also important” (EX16).

A common form of support is the integration of CGs in public programs and initiatives for community engagement, education, and public health [27,67,76,86,88,106,112]. Moreover, the coordination between different services within the administration is important as well as support in bureaucratic issues [31,41,43,53,65].

Difficulties and conflicts between gardeners and local governments and administrations have been identified in seven papers, but only in two of our cases. CGs are often located on public land and need public support; therefore gardeners are dependent on local authorities [64]. Such relationships can be complex, bureaucratic, and conflictual [43,53,99]. Conflicts may arise from diverging interests or different expectations regarding actual forms of land use [71,75,83].

Planning cultures are included in the final factor: mindsets, attitudes, and interests. An open-mindedness towards CGs by political-administrative actors and good relations between gardeners and authorities have been considered as important enablers [35,36,70,105]. This is, for instance, the case when visions of gardens by civil society actors are in accordance with the city officials’ visions [67,71,93]. Thirteen of our interviewees stressed the importance of this factor.

On the other hand, a lack of interest [28,62], acknowledgement [50], and support [63,122] were common barriers in the literature; however less in our cases. Corresponding to that, insufficient socio-political resources such as access to and influence on policymakers and government agencies were identified as potential barriers [94]. Inappropriate eligibility or evaluation criteria [44] were identified in one of our cases:

“Management [of the government organisation] here wouldn’t support it at all and made us pull it out because they didn’t like the look of it going to seed”.(EX4)

3.4. Barriers and Enablers Across Dimensions

The quantitative cross-dimensional analysis (Table 6) reveals that nearly as many barriers as enablers were identified in the literature while our cases report more enablers than barriers. Socio-cultural and economic factors were most frequently mentioned, while biophysical and technical as well as political and administrative factors were discussed to a lesser degree. While a large number of enabling or impeding factors could be extracted from the literature, the information is rarely specific with regard to their perceptive context: the identification of barriers and enablers is based on interpretative reading and it is often unclear from which perspective (gardeners, officials, researchers or others) they were perceived.

Table 6.

Barriers and enablers across dimensions.

In our cases, a general difference was found with regard to the numbers of barriers and enablers experienced by either gardeners or external experts. Gardeners reported significantly more enablers than external experts, who were apparently less enthusiastic about recognising enabling factors. This perception gap between gardeners and external experts is particularly obvious within the socio-cultural and economic dimension. While both groups reported the same number of barriers, external experts identified only around half of the numbers of enablers than gardeners.

4. Discussion

In this section, findings are discussed within the theoretical and practical framework of placemaking. Our observations regarding the barriers and enablers to CG development corresponded frequently with the main dimensions of placemaking theory and practice (Figure 1). No explicit connections were made between the (placemaking practice) category “iterative development” and our findings. This could be due to the fact that, in contrast to other placemaking projects, most CGs are already the results of step-by-step implementation and for this reason iterative in nature. However, analysing iterative development processes in CGs could be a subject for future research.

Section 4.1 provides some general observations and interpretations. Section 4.2 discusses the dominance of social-cultural factors that relate to considerations of CGs as placemaking practice (Section 1.2) and theoretical conceptualizations of placemaking (Section 1.1). This section draws explicit connections between our inductively derived categories and the applied theoretical framework for placemaking (Table 7), namely the construction of (individual and collective) meaning, social exchange, social (collective and collaborative) action, and (civil) empowerment (Figure 1). In Section 4.3 we discuss the group-specific perceptions of barriers and enablers. Although a comparative geographical (country) or culture-specific analysis is not the focus of the paper, we discuss a few differences with regard to national planning cultures which became apparent in our case studies in Section 4.4.

Table 7.

Contextualisation of socio-cultural and economic factors and placemaking framework.

4.1. General Observations and Interpretations

In general, the findings indicate that barriers and enablers can have different faces or sides. On the one hand, there are factors that we called “two-sided”, e.g., funding, as it can be enabling if given or obstructing if missing (sufficient funding vs. lack of funding). On the other hand, there is a category that we called “complex two-sided”. These factors have been considered either as barriers or enablers based on context-dependent interpretations. For example, the participation of (socially, ethnically, culturally) diverse gardeners was interpreted as enriching and enabling in one case or conflictual and disabling in another. The juxtaposition of the factors followed an inductive approach, in which we derived the codes for enablers and barriers from the literature and interviews. Some of them could not be standardized in a strict two-sided factor-system and we could only find results for one side—either enabling or obstructing. For example, language issues were only described as barriers; no source or interviewee described language skills as an enabling factor.

Both literature and cases did not focus much on biophysical and technical barriers and enablers. In contrast to the literature, biophysical and technical aspects were predominantly regarded as enablers in our cases. The comparatively low importance of technical factors may be traced to the fact that they are often surmountable barriers or essential conditions that needed to be checked before a garden was put in place. It also seems that commonly reported constraining factors like contaminated soil or lack of water access could be overcome by alternative horticultural engineering techniques. The installation of raised beds or collecting rainwater are some examples. The desirable location of a garden was identified as a key enabler pointing at the relevance of spatial closeness between a garden and its community.

4.2. Dominance of Socio-Cultural Factors

The socio-cultural and economic dimension was the most discussed dimension in both literature and cases. A broad variety of factors was allocated to this dimension. The most frequently mentioned factor in the literature was dissemination and sharing of knowledge and skills, followed by funding and funding strategies. The importance of these factors was confirmed in our interviews. In the context of placemaking, the dissemination of knowledge and skills might be a critical pathway for CGs to cope with biophysical limitations and to transform a collective vision into the physical reality of an urban space. Based on our findings, we argue that educational aspects need to be integrated more strongly in the placemaking literature. The creation and dissemination of knowledge and skills has been the most enabling factor in our study. It corresponds well with the four dimensions of the theoretical framework for placemaking. It is a binding element that connects dimensions (Table 7).

Three of the most frequently mentioned enabling factors in both literature and cases were leadership and governance; sense of community, community trust, and commitment; continuity and participation (Table 4). These factors are also at the core of the theoretical discussion of placemaking, particularly around the social exchange and collective and collaborative action categories (Table 7). Compared to biophysical and technical barriers, limitations in the socio-cultural sphere cannot be fixed easily. Our findings underline the relative importance of these categories for future research in the context of placemaking and the development of urban CGs.

The most significant difference between the literature and our cases was found with the enabling factor passion and self-motivation, and collectively shared vision. Such a shared vision emerges over time, based on communication and mental rapprochement. As an orientation, a shared vision provides common ground for various individual visions and orientations. It supports the construction of shared or collective meaning. Based on our findings, we argue that a common vision is vital for developing small local interventions as much as implementation strategies that intend to create wider social benefits. The practice-oriented placemaking literature recognised the importance of a common vision [16], reflected as a shift in power from planning experts to the public according to the slogans: “The Community is the expert” and “Look for partners—you cannot do it alone”. Likewise, a common vision was identified as a basic pillar (community network and vision) of CG development [17].

Leadership and governance were of importance; however, we found significant differences between the literature and our cases. For example, conflicts regarding leadership, an important barrier according to the literature, were rarely reported in the interviews. Group-related factors were the most differentiated category highlighting the character of CGs as social places.

4.3. Group-Specific Perceptions of Barriers and Enablers

The findings reveal that conceptions of CGs as meaningful places are group-specific. Accordingly, perceptions of barriers and enablers represent community interests, aspirations, or values. Knowledge about group-specific perception gaps is currently underrepresented in CG research, but central in the observation and understanding of the socio-cultural component. During our study, it became obvious that barriers and enablers identified in the literature may be experienced differently by garden activists, representatives of municipalities, or members of umbrella organisations.

Our cases reveal that gardeners showed a great awareness for enabling factors. However, the placemaking literature with regard to CGs has focused more frequently on dealing with obstacles [17]. This is not to say that there are not plenty of barriers. However, gardeners paid more attention to proactive approaches and identified enablers as opportunities for positive development rather than pondering reactively on how to deal with obstacles. This is a crucial finding of our study. It identifies not only relevant group-specific differences in the perception of barriers and enablers but also gaps between the placemaking literature and our empirical data. Revealing and discussing such differences are, as argued in the introduction, an important step towards better collaborative placemaking approaches.

We encountered a lesser degree of difficulties and conflicts between gardeners and local governments, administration, and authorities in our cases than in the literature. This may be explained by a shift in planning practices towards a more institutionalised integration of CGs into urban development policies and planning, as well as by emerging cultures of cooperation [132,140,141].

While the external experts were rather reluctant about socio-cultural enabling factors, they confirmed the importance of political and administrative factors due to their roles in public administrations or NGOs. They may perceive an increasing relevance of bottom-up initiatives and support them accordingly.

4.4. Differences with Regard to National (Planning) Cultures

Neighbourhood-related barriers were found in our cases; particularly, conflicts with neighbours occurred more often in the German cases. This may be due to different cultures in both countries; Germany has a long tradition of regulated allotments against which CGs may appear unregulated and untidy. It also needs to be acknowledged that the selected German cities have higher population densities than low-density suburban Christchurch. However, it goes beyond the scope of the paper to discuss possible correlations between population densities—or regulations for CGs—and conflicts between neighbours.

Some other significant differences between New Zealand and German cases occurred: while most German gardeners stressed funding as an enabling factor, only two New Zealand respondents did so. This might be related to a traditionally stronger welfare-state orientation of German public actors, who comparatively often provide public funding to gardening projects, which then is perceived as an enabler by the gardeners. There might be simply different (lower) expectations in New Zealand where projects receive generally less public funding and rely more often on financial support from private donors or NGOs. However, looking at the barrier-side of funding, most external experts from New Zealand—but none from Germany—recognised financial uncertainties and a lack of funding as obstructions, revealing a perception gap between the different informant groups and national contexts.

Similarly, the political and administrative dimension of our study encompasses considerably fewer barriers—especially in New Zealand—than in the literature. Might this be a sign of changing political and planning cultures? The cases reveal supportive socio-political contexts and the importance of good relationships between gardening groups and political-administrative actors, and hence a shift from conflicting to cooperative relations.

A comparison of results from both countries reveals that political-administrative factors are of major relevance in the German context. In contrast to New Zealand, gardeners and external experts from Germany emphasize supportive planning systems, regulations, and policies as enabling factors. This perception probably reflects the history of German allotment gardens that are well-regulated by law and acknowledged in the planning system. In addition, the open-mindedness of city officials and their attitudes, as well as visions of the garden in accordance with city officials’ visions were addressed by gardeners and external experts from Germany only. This may be explained by different planning cultures in both countries, including different planning traditions and institutional settings.

5. Conclusions

The paper reveals a large variety of perceived factors that support or obstruct the development of urban CGs in a new category system. We analysed commonalities and differences of enabling and impeding factors identified by our key informants. Given the number of cases and their individual embeddedness in local contexts, we acknowledge the limitations of our observations for generalisation. As the CG movement is a continuously evolving worldwide phenomenon that can be traced back at least to the 1970s, barriers and enablers might have changed over time or are subject to temporal trends. The presented research cannot provide in-depth information about similarities or differences of enablers and barriers in different chronological contexts.

However, the study reveals that it is useful for planning and design practitioners to analyse CGs through the lens of different actors in order to draw conclusions on how to support CGs in their role as relevant urban places. There are at least three main findings that deserve to be highlighted.

First, the many reported barriers and enablers that refer to socio-cultural factors suggest that CGs are predominantly socio-cultural phenomena, created by and for (local) communities. Passion and self-motivation, good governance, a sense of community, commitment, and the sharing of knowledge are the most relevant enablers. Gardening communities need to nurture, promote, and develop related attributes, skills, and visions. The findings emphasize the highly relevant social meaning of urban CGs related to their making and associated group dynamics. These findings relate to the theoretical and normative framework of placemaking. CGs are not only about physical and material dimensions or the amount of produced vegetables. Community gardeners reclaim and transform open space into meaningful social places. Institutional support for these gardens is therefore more than a technocratic planning act—it is placemaking in action.

Second, while our study identified a general tendency to more positive and cooperative relations between community gardeners, local governments, and administrations, significant differences between actors exist. A detailed analysis of causes for such perception gaps has not been a subject of this study. However, it would be worthwhile to focus on these in subsequent studies and to develop mitigation strategies that bridge perceptual differences in order to overcome related barriers.

Third, our study reveals differences with regard to national planning cultures which may have an important influence on how CGs are perceived, acknowledged, supported, or hindered. CGs in Germany are situated within a public urban development practice following the logics of the political-administrative system and its representatives. New Zealand gardens seem more independent from those structures and actors. Further research regarding different (national) planning cultures and their respective effects on the development of urban CGs is therefore recommended.

Author Contributions

All authors contributed to conceptualization; methodology; validation; formal analysis; investigation; data curation; writing—original draft preparation; writing—review and editing; visualization; supervision; project administration; funding acquisition. A.W. was the leading researcher and coordinator for research activities in New Zealand. R.F.-K. was the leading researcher and coordinator for research activities in Germany. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

The authors would like to acknowledge COST Association for the funding of COST Action TU1201 (Urban Allotment Gardens in European Cities) that enabled networking activities to conduct this research and the funding of a Short-Term Scientific Mission (STSM) of Daniel Münderlein to Christchurch. Andreas Wesener acknowledges seed funding from the Faculty of Environment, Society and Design at Lincoln University and funding from The Royal Society of New Zealand to attend COST Action TU1201 5th Plenary session, Working Groups’ meeting and 6th Management Committee meeting in Nicosia/Cyprus in 2015. In addition, the authors are grateful for the coverage of the article processing charge (APC) by the University of Kassel (Germany).

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the (student) assistants Venus Nazerian, Maurice Riesche, Evita Giebeler (Academy for Spatial Research and Planning (ARL), Germany), and Miriam Kuhlmann and Nadja Kasselmann (University of Kassel, Germany) for their support in evaluating the literature. In addition, the authors would like to thank the PhD student Asif Hussain (Lincoln University, New Zealand) for his support in comparing, verifying, and correcting qualitative research data and data analysis. Finally, the authors would like to thank all garden experts (CG) and external gardening experts (EX) for taking part in our interviews and for sharing their valuable knowledge.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Guitart, D.; Pickering, C.; Byrne, J. Past results and future directions in urban community gardens research. Urban For. Urban Green. 2012, 11, 364–373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tuan, Y.-F. Space and Place: The Perspective of Experience; University of Minnesota Press: Minneapolis, MN, USA, 1977; Volume Seventh printing 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Steele, F. The Sense of Place; CBI Publishing: Boston, MA, USA, 1981. [Google Scholar]

- Jackson, J.B. A Sense of Place, A Sense of Time. Oz 1986, 8, 6–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Seamon, D. Place attachment and Phenomenology: The Synergistic Dynamism of Place. In Place Attachment: Advances in Theory, Methods and Applications; Manzo, L.C., Devine-Wright, P., Eds.; Routledge: London, UK, 2014; pp. 11–22. [Google Scholar]

- Healey, P. Towards a more place-focused planning system in Britain. In The Governance of Place: Space and Planning Processes; Madanipour, A., Hull, A., Healey, P., Eds.; Ashgate: Aldershot, UK, 2001; pp. 265–286. [Google Scholar]

- Gehl, J. Cities for People; Island Press: Washington, DC, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Jacobs, J. The Death and Life of Great American Cities; Vintage Books: New York, NY, USA, 1961. [Google Scholar]

- Whyte, W.H. The Social Life of Small Urban Spaces; Project for Public Spaces: New York, NY, USA, 1980. [Google Scholar]

- Healey, P. Collaborative Planning: Shaping Places in Gragmented Societies; Macmillan: London, UK, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Allmendinger, P. Planning Theory, 2nd ed.; Palgrave Macmillan: Basingstoke, UK, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Rios, M.; Watkins, J. Beyond “Place”. J. Plan. Educ. Res. 2015, 35, 209–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strydom, W.; Puren, K.; Drewes, E. Exploring theoretical trends in placemaking: Towards new perspectives in spatial planning. J. Place Manag. Dev. 2018, 11, 165–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toolis, E.E. Theorizing Critical Placemaking as a Tool for Reclaiming Public Space. Am. J. Commun. Psychol. 2017, 59, 184–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Project for Public Spaces. Available online: https://www.pps.org/ (accessed on 15 January 2020).

- Madden, K.; Schwartz, A. How to Turn a Place Around: A Handbook for Creating Successful Public Spaces; Project for Public Spaces: Washington, DC, USA, 1999; p. 121. [Google Scholar]

- Karge, T. Placemaking and urban gardening: Himmelbeet case study in Berlin. J. Place Manag. Dev. 2018, 11, 208–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fox-Kämper, R. Concluding remarks. In Urban Allotment Gardens in Europe; Bell, S., Fox-Kämper, R., Keshavarz, N., Benson, M., Caputo, S., Noori, S., Voigt, A., Eds.; Routledge: Abingdon, UK, 2016; pp. 364–369. [Google Scholar]

- Kingsley, J.; Townsend, M. ‘Dig In’ to Social Capital: Community Gardens as Mechanisms for Growing Urban Social Connectedness. Urban Policy Res. 2006, 24, 525–537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kingsley, J.; Foenander, E.; Bailey, A. “You feel like you’re part of something bigger”: Exploring motivations for community garden participation in Melbourne, Australia. BMC Public Health 2019, 19, 745. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berger, P.L.; Luckmann, T. The Social Construction of Reality: A Treatise in the Sociology of Knowledge; Anchor Books: New York, NY, USA, 1967. [Google Scholar]

- Cosgrove, D.; Daniels, S. The Iconography of Landscape: Essays on the Symbolic Representation, Design and Use of Past Environments; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 1988. [Google Scholar]

- Cosgrove, D. Prospect, Perspective and the Evolution of the Landscape Idea. Trans. Inst. B. Geogr. 1985, 10, 45–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cosgrove, D. Social Formation and Symbolic Landscape; The University of Wisconsin Press: Madison, WI, USA, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Snyder, H. Literature review as a research methodology: An overview and guidelines. J. Bus. Res. 2019, 104, 333–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agustina, I.; Beilin, R. Community Gardens: Space for Interactions and Adaptations. Procedia Soc. Behav. Sci. 2012, 36, 439–448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corkery, L. Community Gardens as a Platform for Education for Sustainability. Aust. J. Environ. Educ. 2004, 20, 69–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Evers, A.; Hodgson, N.L. Food choices and local food access among Perth’s community gardeners. Local Environ. 2011, 16, 585–602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guitart, D.A.; Pickering, C.M.; Byrne, J.A. Color me healthy: Food diversity in school community gardens in two rapidly urbanising Australian cities. Health Place 2014, 26, 110–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guitart, D.A.; Byrne, J.A.; Pickering, C.M. Greener growing: Assessing the influence of gardening practices on the ecological viability of community gardens in South East Queensland, Australia. J. Environ. Plan. Manag. 2015, 58, 189–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hardy, I.; Grootenboer, P. Schools, teachers and community: Cultivating the conditions for engaged student learning. J. Curric. Stud. 2013, 45, 697–719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henryks, J. Changing the menu: Rediscovering ingredients for a successful volunteer experience in school kitchen gardens. Local Environ. 2011, 16, 569–583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Holstein, E. Transplanting, plotting, fencing: Relational property practices in community gardens. Environ. Plan. A Econ. Space 2016, 48, 2239–2255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kingsley, J.; Townsend, M.; Henderson-Wilson, C. Cultivating health and wellbeing: Members’ perceptions of the health benefits of a Port Melbourne community garden. Leis. Stud. 2009, 28, 207–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Middle, I.; Dzidic, P.; Buckley, A.; Bennett, D.; Tye, M.; Jones, R. Integrating community gardens into public parks: An innovative approach for providing ecosystem services in urban areas. Urban For. Urban Green. 2014, 13, 638–645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mintz, G.; McManus, P. Seeds for Change? Attaining the benefits of community gardens through council policies in Sydney, Australia. Aust. Geogr. 2014, 45, 541–558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nolan, E.; March, A. Remembering participation in planning: The case of the Princes Hill Community Garden. Aust. Plan. 2016, 53, 187–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stocker, L.; Barnett, K. The significance and praxis of community-based sustainability projects: Community gardens in western Australia. Local Environ. 1998, 3, 179–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baker, L.E. Tending cultural landscapes and food citizenship in Toronto’s community gardens. Geogr. Rev. 2004, 94, 305–325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- CoDyre, M.; Fraser, E.D.G.; Landman, K. How does your garden grow? An empirical evaluation of the costs and potential of urban gardening. Urban For. Urban Green. 2015, 14, 72–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crane, A.; Viswanathan, L.; Whitelaw, G. Sustainability through intervention: A case study of guerrilla gardening in Kingston, Ontario. Local Environ. Int. J. Justice Sustain. 2013, 18, 71–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Irvine, S.; Johnson, L.; Peters, K. Community gardens and sustainable land use planning: A case-study of the Alex Wilson community garden. Local Environ. 1999, 4, 33–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jermé, E.S.; Wakefield, S. Growing a just garden: Environmental justice and the development of a community garden policy for Hamilton, Ontario. Plan. Theory Pract. 2013, 14, 295–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]