Abstract

All sports have their roots and connection in some way to the Olympic spirit, and therefore fall within the vision and mission of the Olympic Committee, which has a central aim of “building a better world”. This is a fundamental value of the Olympics and sustainability is a “working principle” of this. This research analyses the performance of professional European football teams that are publicly listed on stock markets, analysing their income statements and factoring in how the value-added perspective is impacting professional sport. The methodology we use considers the sustainable contribution of the distribution of added value. The Value-Added Statement is considered as a part of broader Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR), which can be traced back as a concept to the late 1970s. It is still in widespread use and is regarded as being both a credible and a tested measure. In this paper, the authors apply a slightly modified and simplified version of this value-added approach to all publicly listed European football clubs and use these as a proxy for wider professional sport. This research demonstrates that, although most professional sports clubs are profit-oriented, the distribution of wealth generated by the added value is unbalanced. In most cases, at least in financial terms, the data shows shareholders are the most disadvantaged, whereas athletes are the most rewarded.

1. Introduction

The Olympic spirit [1,2,3,4] has always captured the collective imagination, both in ancient Greece and now more globally with the modern Olympic Games, following the revival by Baron Pierre de Coubertin in 1896 [3,4]. This “spirit” can be described as the principle of seeking to achieve harmony through the breaking down of barriers and opening of borders through sport. Sport is inclusive because all humans can partake in it and competition between individuals and teams builds respect and mutual understanding. The Ancient Greeks had a “sacred truce” where peace was ensured within the host city to allow competition to flourish and stop violence. This shows that even in ancient times, the desire to compete in sports could promote peace [5].

Within this research, the authors highlight the incredible contribution that sports provide towards local, national, and global communities [6,7]. The values in the sport used by the Olympic Movement [5,6,7,8,9,10,11,12,13,14,15,16,17,18,19,20,21,22,23,24,25,26,27] and Paralympic Movement [28] should permeate all aspects of the sporting sector and therefore cover both athletic and financial performance and strategy [29]. Individuals and organizations have different objectives and targets, but, guided by the Olympic principles, they should be guided by these same principles.

Many studies, [30,31,32,33] have focused on the ability of sport to contribute to the common good, through health, ethics, and fair play. Some scholars [34,35] have looked at the contribution of sport to the common good and considered how it unites people from all backgrounds and helps the world to avoid conflicts. Sport has the power to stop conflict and build barriers. For example, a famous football match was played during world war one between British and German troops who called a temporary truce to play each other. Conflict can be played out on a football pitch rather than a battleground.

The term “common good” [36,37] is often presented as a rhetorical concept characterized by very general and metaphysical statements. It is now mainly studied within social science, political science, sociology, law, philosophy, and economics [38,39,40]. Sport has been considered by some to be an important part of the common good within democratic societies since it is considered as an essential part of that enjoyment of citizens.

Achieving a common good on a truly global scale has always been considered challenging because different communities have different value systems. It is therefore even more difficult to create a framework where all individuals are satisfied without reducing someone’s well-being, as there are many conflicting interests where compromise is seemingly not possible [41,42,43]. According to Arrow, no collective decision rule is able to simultaneously satisfy all the requirements stated in the “Impossibility Theorem” (non-dictatorship, universality, independence of irrelevant alternatives, monotonicity, citizen sovereignty, and unanimity) [44,45,46]. To overcome this impossibility, either the conditions must be weakened or societies must become more integrated and individual preferences more homogenous. Thus, if societal preferences are “at a single peak” [47], then the majority does not lead to intransitivity. Therefore, given this restriction, a valid social decision rule might exist, and it could lead to the alternative preferred by the median voter (median voter theorem).

A different solution, suggested by Sen [48], consists of using a wider set of information than just the preferences, and therefore the well-being, of individuals. After all, nowadays, sport is not considered only as evidence of the level of development reached by a particular society, but also as the parameter of the rights achieved and enjoyed by its citizens. Sport is itself the bearer of intrinsic goods. Sport becomes part of the common good when its values—which are linked to the system of human, social, and educational rights as well as the resources that a club makes available to the entire population—are disseminated and enjoyed without discrimination, guaranteeing full access to all the citizens. The analysis performed in this research demonstrates sport is a fore for the common good. The sustainability of a sports clubs in general (of football clubs in particular) can therefore be analysed according to different perspectives such as (a) improvement of sports performance; (b) maintaining competitiveness in local, national, and international competitions; (c) sustainability of financial management (in terms of cash flow and profitability); (d) development of communities that support the club; (e) sports and moral education of athletes [49,50,51].

Among all the alternatives, although all relevant, in this research, the term “value” has been considered according to its contractual meaning, without any further qualitative consideration (i.e., in terms of priority/ranking): (a) employment contract/salary payment; (b) loan agreement/payment of interest; (c) residence in a country/income taxes owed; (d) acquisition of tangible and intangible production factors/depreciation/amortization; and (e) ownership of a company/dividends/capital loss. This perspective, therefore, makes it possible to obtain a rather objective measurement. The specific measurement of value, which takes place in monetary terms, is made according to an exclusively quantitative, not qualitative, perspective. Although this approach may seem limiting, it therefore avoids having to consider the preferences among stakeholder groups, thus ensuring an analysis that completely disregards weightings that could instead imply subjective and impartial assessments. In this way, sustainability has been analysed exclusively according to its contractual aspects that bind the various stakeholders to the clubs’ operations, alternatively: (a) work; (b) purchase; (c) debt; (d) residence; and (e) ownership. Any contract can be thus considered fair as long as it is freely accepted by the parties under fair current market conditions. The satisfaction of both parties (clubs and their stakeholders) cannot be therefore further questioned [52,53]. This research deliberately does not intend to prioritize preferences among all stakeholders, who are all deemed equally worthy of consideration.

In particular, this research considers the value-generating aspects of football clubs and uses an approach borrowed from the analysis of financial sustainability. Here the authors analyse the distribution of the added value determined by strictly sporting activity amongst all stakeholders. Sport, by its nature, whether practised professionally or at an amateur level, has been shown to bring various benefits to communities in terms of tourism, the promotion of positive social values, health, and urban development.

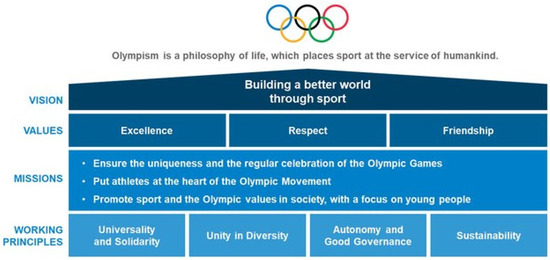

The Olympic principles [8] (see Figure 1) inspire sporting practice at all levels and in all disciplines.

Figure 1.

Olympism Vision, Values, Missions, and Working Principles. Source: www.olympic.org.

The inspiration from the Olympic spirit that has its roots in the culture of ancient Greece, highlights how physical exercise through sport also evokes the meaning of gymnasium (in Greek, “γυμνασιoν”), extending its value to an educational scope [54,55]. The gymnasium was in fact originally the place where young people practised athletic games, and later, it was also a centre for spiritual education and a meeting place, where banquets, parties, theatrical performances, lessons, and conferences were held. In the modern age, gymnasium also identifies classical study courses, based on ethics and philosophy, regulated in western countries [56]. Hence, given its educational, cultural, and ethical value, a great educational and exemplary responsibility is entrusted to sports. This is why the recent corruption scandals that have hit the world of sports (football in particular) have caused outrage and a public outcry throughout the international community. Sport is seen as a level playing field where any and all can flourish, and when it is corrupted, this evokes a sense of outrage. Some people have little in their life other than their sense of belonging to a community, such as a football team, so their emotions are hypersensitive to any injustice that might impugn the team they support or cast any negative light on the sport they invest their time, money, and/or emotions in.

Beyond the assessments regarding the creation of value (which will be discussed below), it should always be considered that even in the sports field (which should be considered fair and ethical by definition), corporate governance controls are necessary to ensure proper management, preventing fraud such as corruption, competition manipulation, or doping—which represents the most widespread scourge in the sector, generating a negative impact on reputation which then affects sponsorship [57,58,59,60]. Corruption in sports can be on the field of play or behind the scenes. Examples of management corruption include extortion and election manipulation [61,62]. In the most serious cases, management corruption is also a criminal offence. The World Anti-Doping Code [63] is mandatory for the Olympic movement and has also been adopted by many non-Olympic sports.

Many sports organizations nationally and internationally are responsible for organizing anti-doping initiatives, including education and control programs. The IOC (International Olympic Committee) has implemented its own strategy for the prevention of competition manipulation, which is based on three pillars: (a) regulations and legislation; (b) awareness-raising and capacity-building; (c) intelligence and investigations. The threat of competition manipulation has also been recognized by governments and international institutions [64,65]. In the UK, the Sports Betting Group brings together representatives from all sports and serves as a guide to tackle the risk of corruption in sports betting, where there is a Code of Conduct for use by management bodies [66].

A recent Council of Europe Convention on the Manipulation of Sports Competitions (2014) includes detailed measures to be implemented by member states both within Europe and potentially beyond its borders. Sports governance first came under serious scrutiny in the 1990s, thanks to the work of academics, investigative journalists, and sponsoring organizations. Among the rules on governance included in the IOC 2020 Agenda, there is the need on the part of the organizations belonging to the Olympic Movement to accept and respect the universal basic principles of good governance of the Olympic Sports Movement [67]. Some sports organizations have also embarked on governance reform processes, usually following the onset of a crisis. However, the speed of progress in the sports sector as a whole is slow. In addition to the good governance codes that have been published, governments and regulatory bodies in many countries have begun to disclose governance standards that sports clubs will have to strive to achieve in order to receive public funding.

This research demonstrates, through the application of a simple but effective methodology, that, although professional European football clubs are considered to be profit-oriented, the distribution of wealth generated by the added value is unbalanced. In most cases, at least in financial terms, owners and shareholders are the most disadvantaged and athletes are the most rewarded.

It is important to highlight a different approach adopted by European sports systems when compared with American ones. The American systems, particularly the NFL (National Football League), prioritize profit maximization and the leagues are structured and operate accordingly. In the European system, despite some clubs being listed on stock exchanges, football clubs’ financial statements show they are burdened with high debt and are operating at a loss, with very few exceptions [68,69,70,71,72]. This shows that those investing in sports where there is an operating loss must be doing so for non-capitalist reasons, as many wealthy people make highly speculative risks when they buy loss-generating football clubs, which generally never produce positive financial outcomes.

European football clubs also differ from other capitalist enterprises, both in terms of organizational structure and a specific sport “product”, since football can be considered a joint product (it arises from the collaboration/clash of two teams). The greater the uncertainty of the result the greater the public interest, therefore reducing the interest of the wealthiest clubs to become monopolies in their championships (leading to the so-called Louis–Schmeling paradox) [73]. A competitive market (championship) is therefore essential to ensure the uncertainty of results, consequently increasing both public interest and financial returns. Uncertainty of results is clearly a necessary condition for maximizing the profit of the individual clubs and the league as a whole [68,69,70,71,72]. Spectators enjoy an underdog story, which is why the story of David and Goliath is still told to this day, and also why a movie was made when Leicester City won the English Premier League in 2016. People enjoy outcomes that are not predetermined and like being surprised; the most competitive sporting events garner the most attention as the outcome is not clear

The American sports system is set up to attempt to prevent dominant positions from being attained by clubs in leagues. This is achieved both by limiting the competition between the teams through a redistribution of players and levelling the playing field by providing subsidies to the weaker teams. European Universities and schools do not contribute as a source of athletes for professional sports in the same way they do in America. In American sport, scholarships are a large part of their education system and it encourages students to dedicate themselves to being the best to attain the best scholarships. In Europe, education is more weighted towards academic performance with sports as an aside. This is very interesting as it is far more competitive to become a professional sportsperson in America but when you have achieved that position, the system itself is designed to encourage competition and stop monopolies, and so it is a heavily regulated marketplace. Sloane [74,75,76] found that the true purpose of a professional team is to maximize utility, which overlaps with that of the managers, players, fans, and shareholders. This shared interest is a specific and unique characteristic of the sports enterprise. The achievement of a profit, therefore, becomes not the ultimate goal, but only the means by which a football club can increase visibility; indeed, it can be said that the main objective is to maximize sports performance and success by financially setting a long-term, break-even target. Although football clubs’ entrepreneurs are often fanatical supporters, it cannot be completely justified as the only reason why they accept non-remuneration and, more often, loss of invested capital. Moreover, it has been identified that indirect returns related to the “media exposure” of football clubs, such as prestige, notoriety, sponsorship opportunities, and extra-football businesses are important motivators [77,78].

Other differences between the North American and European sports systems can be summarized in the following two main features: (1) Leagues; in the American model there are no promotions or relegations and new teams are rarely admitted. The European leagues model is based on promotion and relegation mechanisms. (The structure of the North American leagues is closed, and the European structure is open inwards and outwards). (2) Broadcasting rights revenue distribution; in North America, national and international sports broadcasting is bargained by the leagues, who collectively negotiate the rights of teams, dividing their revenues equally (only local TV networks can negotiate directly with the clubs), while in Europe, sports broadcasting rights are generally determined on the basis of performance and, only to a lesser extent, at a fixed rate [68,69,70,71,72].

Given the above relevant differences between the sports systems, it is essential to point out that this research, focused on European football clubs, cannot be extended to other contexts such as that of North America.

2. Materials, Methods, and Literature

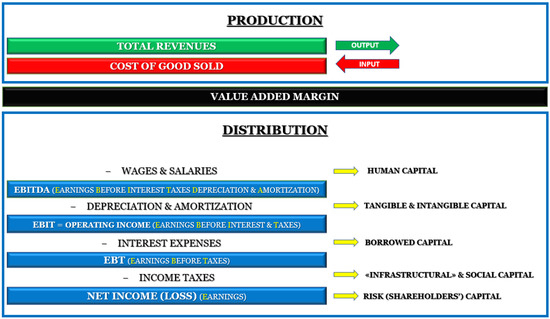

The literature on sustainability concerns the environmental, social, and financial facets of the organization. Sustainability reporting is therefore a transversal topic of absolute importance because it allows the results of the Corporate Social Responsibility’s (CSR) actions to be highlighted. CSR is a central aspect of the outreach work that many sporting institutions undertake within their local communities. Within the Sustainability Report, value-added is understood as the difference between the revenues and costs of production limited to costs of purchasing goods (Cost of Goods Sold/Cost of Sales) and services useful for the production process [9]. Value-added in this context is therefore the difference between revenues and costs incurred for the purchase of production factors from other companies, and thus represents the value that the internal production factors of the company, risk capital and labour, have “added” to the inputs attained from outside.

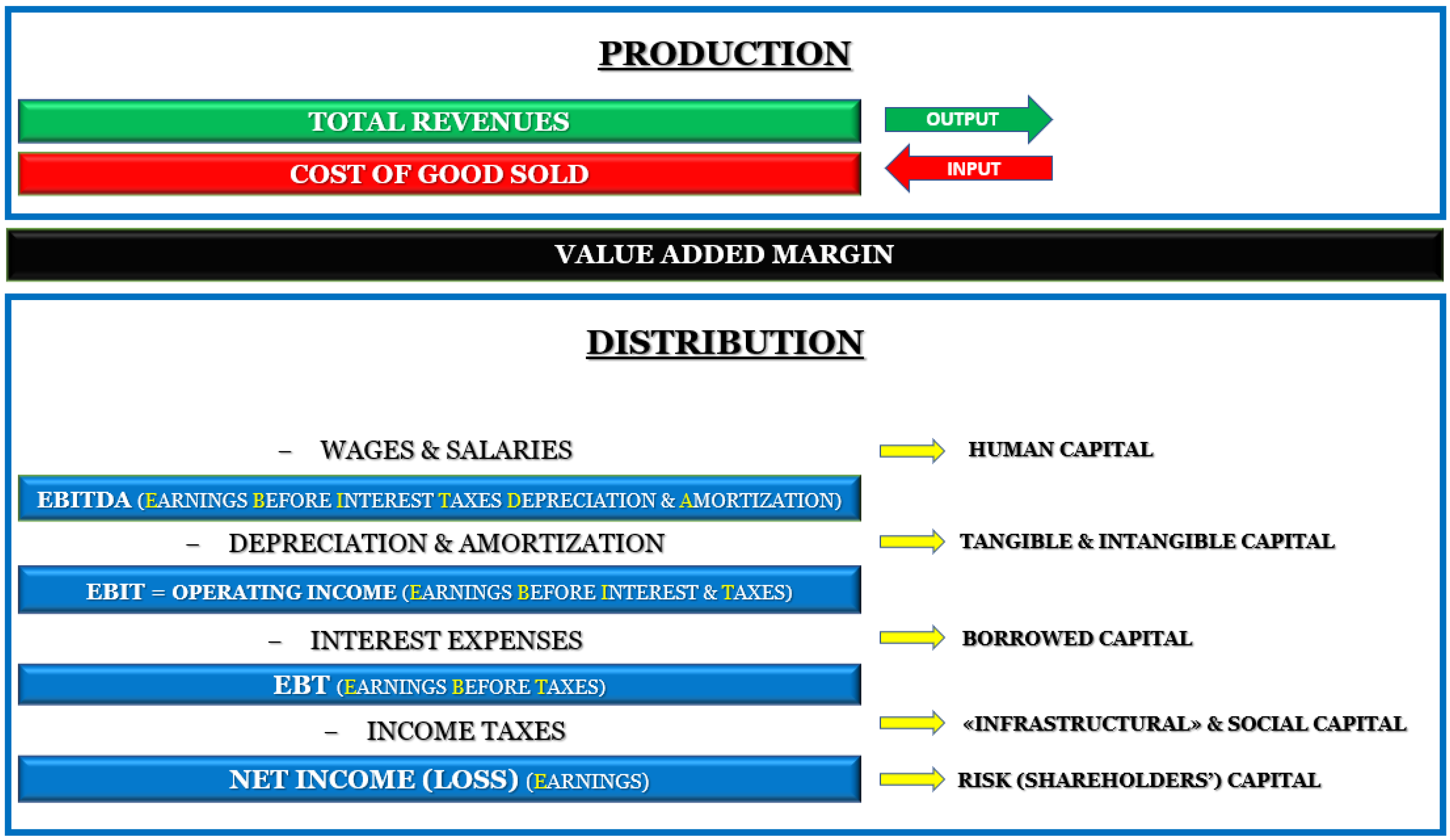

The concept of added value here differs from the accounting definition because it adopts the methodology proposed in 2001 by the Study Group for the Social Report—GBS—“Gruppo di Studio per il Bilancio Sociale” [10]—in Italy. With respect to the methodology proposed by the GBS, and in particular, deepened by two main scholars, Mei [11,12,13] and Manni [9,14,15,16,17,18,19,20,21], some appropriate approximations and normalizations were considered due to the limited availability of financial data of the sample companies. This is applicable here because the sample is limited to European Football clubs listed on their national stock markets. According to this approach, the global gross added value distributed is almost attributable to the gross added value produced by the core business. Value-added is considered for two main reasons. First of all, it allows us to quantify how much wealth has been produced by the companies, how it was produced and how it is distributed. It is therefore useful to understand the economic impact a club produces. Secondly, it links closely to the Sustainability Report with the Financial Statements through the analysis presented in this research. Football clubs listed on stock exchanges are required by law to publish accounts and are therefore an appropriate sample with clear and comparable data. Accordingly, the production and distribution of added value is a tool for reconsidering the company’s financial statements from the stakeholders’ points of view (see Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Value-Added “revised” income statement. A sustainable approach.

Given that the value-added is mainly generated from broadcasting rights, shirts and merchandise, sponsorship, and matchday revenue, the bulk of customers are expected to be the expenditures of the clubs’ supporters on the club [22], the net of running costs. In Figure 2, the distribution of the various restated items of the income statement is clearly linked with the capital contributed by the stakeholders, in the priority order of distribution (classified according to the source of capital to be rewarded by the distribution of the value-added). According to the generally recognized priorities, (a) wages and salaries are distributed to the athletes (human capital); (b) depreciation and amortization are related to the incurred expenses due to the use of tangible and intangible assets; (c) interest expenses provide the return of the investment made by the borrowers; (d) income taxes are related to the expected contribution of any entity to the so-called “infrastructural and social capital”, and thus links to statutory government provisions of social benefits such as health, education, welfare, and the rule of law; finally, (e) the return for the shareholders—the net income (or net loss). It is pertinent here that shareholders are listed last.

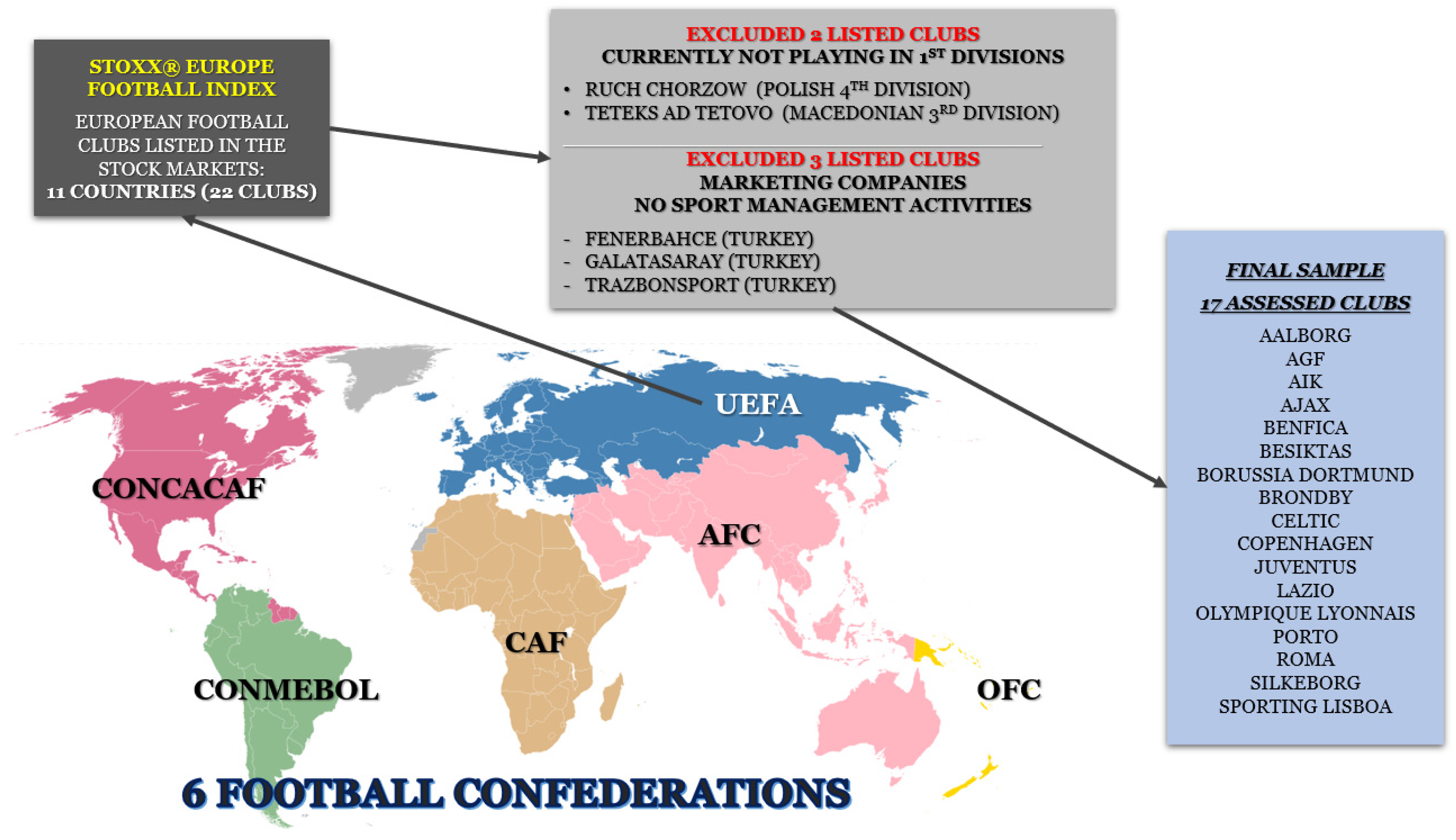

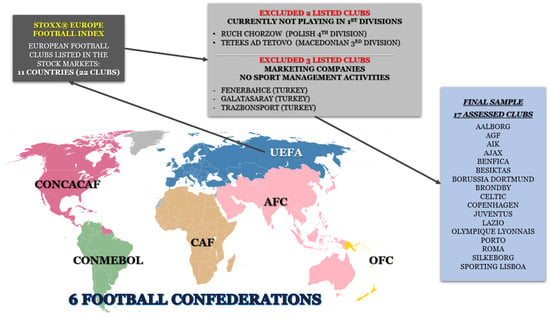

In order to identify a relevant sample, the authors followed a number of steps: (a) among the six football confederations, UEFA (Union of European Football Associations) was identified, as this focuses the analysis on the European market; (b) STOXX Europe Football index to identify the European football clubs listed in the stock markets; (c) among the clubs included in the STOXX index, some of them were excluded (the Polish RUCH CHORZOW–4th division and the Macedonian TETEKS AD TETOVO–3rd division: Fenerbahce Futbol AS, Galatasaray Sportif Sinai ve Ticari Yatirimlar AS, Trabzonspor Sportif Yatirim ve Futbol Isletmeciligi TAS, since they are classified as “marketing companies” instead of football clubs by Bloomberg Business Intelligence) [23] (see Figure 3). This provided a clear cohort of European based football clubs that adhere to similar financial regulations, inside and outside of the sport. The following clubs therefore constitute the final sample: Borussia Dortmund, Brondby, Celtic, Futebol Clube do Porto, Juventus, Olympique Lyonnais, FC Copenhagen, Sporting Lisboa e Benfica, Sporting Lisboa, Aalborg, AIK, Ajax, AGF, Besiktas, Lazio, Roma, and Silkeborg. The sample considered is thus not only statistically relevant but is also reliable, as it is based on relevant data, as obtained from official primary sources that are available, as a legal requirement, in the public domain.

Figure 3.

Methodology. Process of sample identification.

The dataset used to perform the analyses considered the last 10 years of financial statements (2010–2019) of the selected listed football clubs, was downloaded from the Bloomberg database, and double-checked with the available annual reports directly disclosed by the companies, when available. The financial data have been also normalized and made consistent in terms of currency (Euro). Listed football clubs were selected since only listed companies need to publicly disclose their financial statements by law. The time-frame is also consistent since, starting from 2010, it is not affected by any distortion that could have affected the results during the financial crisis in 2008–2009.

3. Results

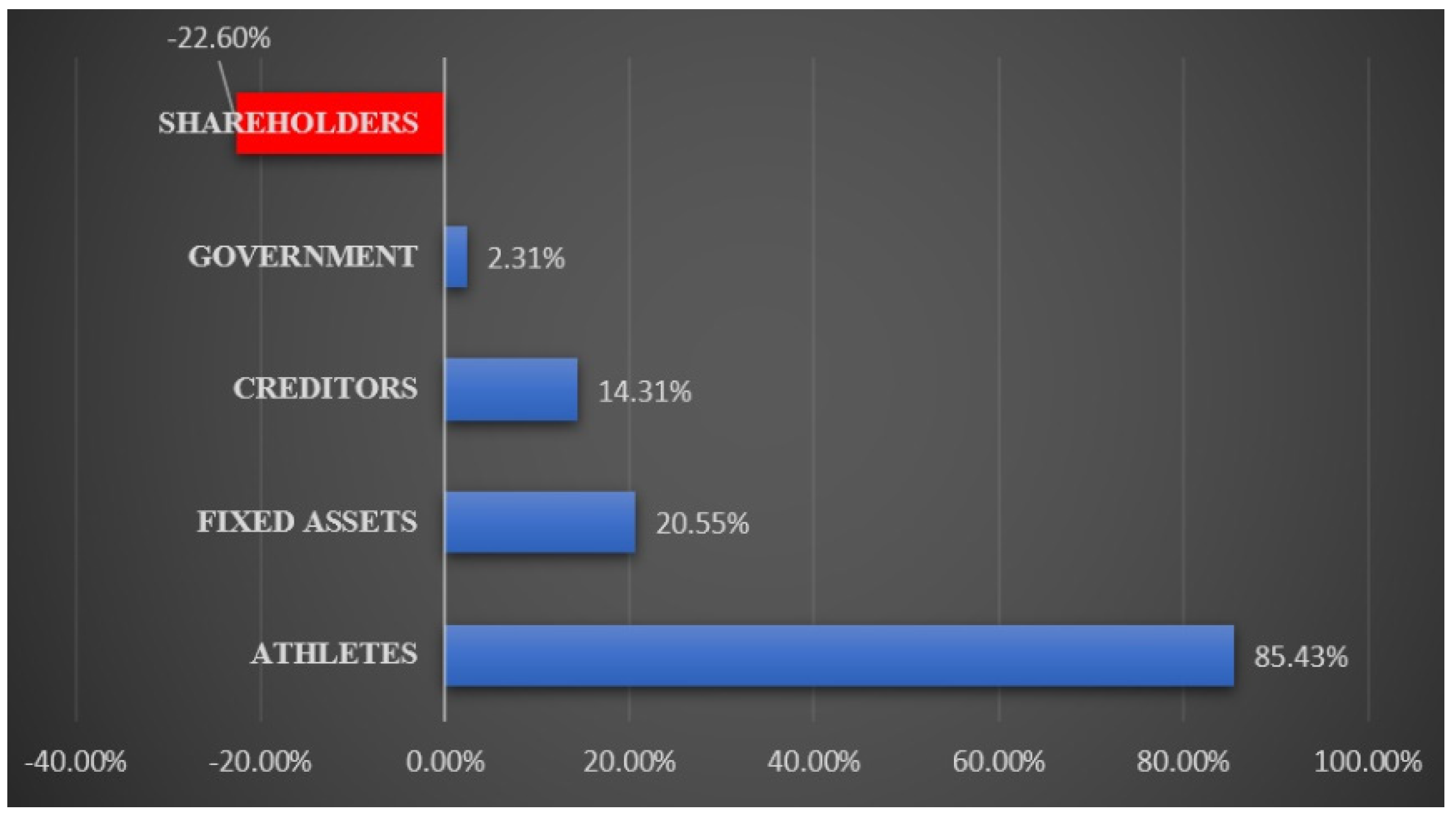

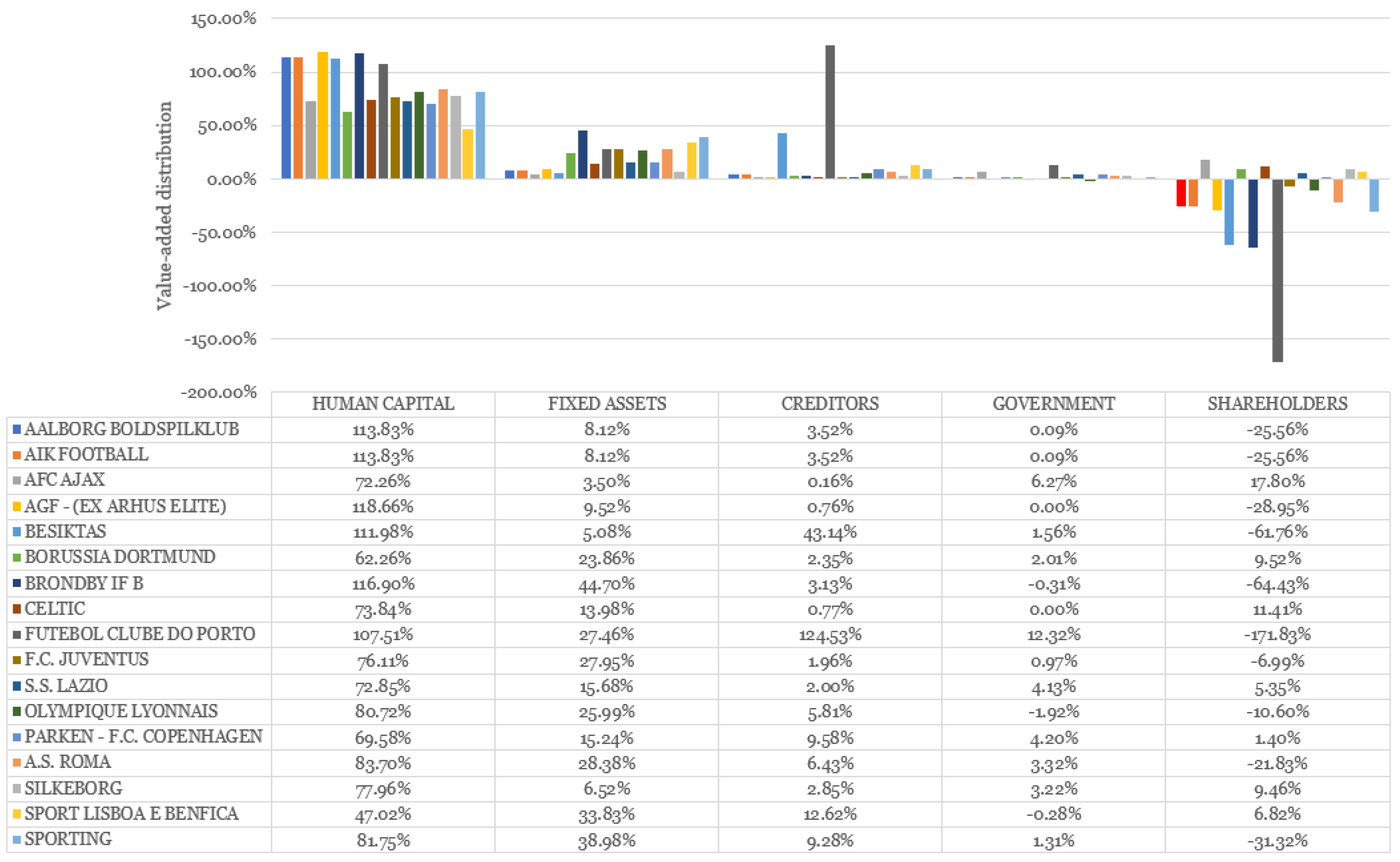

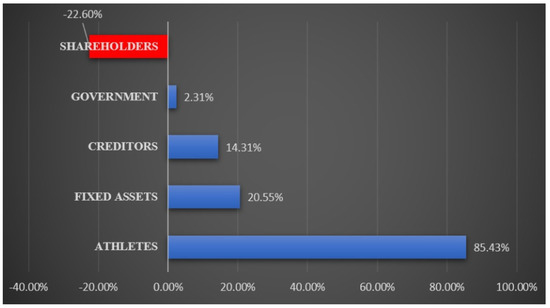

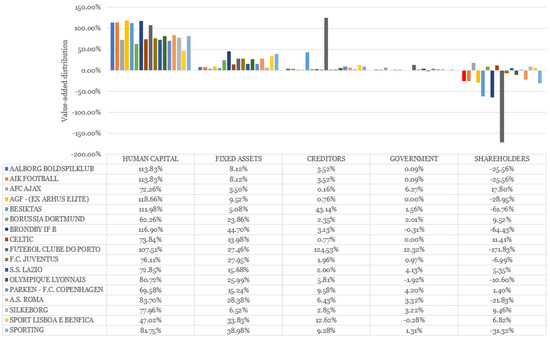

The research was conducted using the outlined methodology (see Figure 4 and Figure 5) and data were collected and analysed from Bloomberg financial data and the annual reports disclosed in the official club websites (investors’ relation sections). From this, it was possible to appraise that the average composition of the distribution of wealth, understood as added value determined by the restated income statements, reports a great imbalance in favour of the athletes. The results determine that on average, among the 17 clubs analysed, 85.43% of the value-added was absorbed by athlete salaries, 20.55% by the amortization of fixed assets, 14.31% by the payment of interest charges to creditors, and 2.31% distributed to the government in the form of income taxes. Finally, the shareholders reported an average net loss of 22.6%. This must therefore be considered as a contribution of wealth (subtracted from shareholders) rather than as a distribution. This loss was necessary to compensate the other stakeholders (such as athletes and debt owners) and due to pre-existing contractual obligations. Effectively, we see a wealth transfer from investors to other stakeholders, primarily the athletes themselves.

Figure 4.

Average Value-Added distribution. Listed European Football Clubs.

Figure 5.

Value-Added distribution. Listed European Football Clubs.

Given that the salaries of elite professional footballers are notoriously very high, it is not surprising that much of the distribution of the added value generated by sporting activity goes to them. It should be noted that this is not the case for all professional sportspeople or even all professional footballers. In financial terms, however, it should be considered that the added value generated by sporting activity in this sample is not sufficient to reward all the stakeholders involved in it. On average, the shareholders are forced to take on this responsibility, with losses suffered from the capital they invested, of the part not covered by the added value of the sporting activity, in order to guarantee the remuneration of the other productive factors brought by the other stakeholders (athletes, fixed assets and creditors, and the government).

The importance of the investment of the shareholders cannot be understated in keeping their club competitive by personally transferring their own wealth to subsidize their clubs’ losses and ensuring financial obligations are met. In a marketplace where personal wealth can be transferred without any checks or balances to support a sporting venture, whoever transfers the most wealth can attain the most success. The reasons someone might choose to own a loss-making sports team are often totally outside the potential financial benefits and include status and profile [24], sporting fandom, and other spill-overs in terms of related investments. With regards to this last aspect, particular reference is made to the construction/improvement of stadia and sports facilities for training, and also to retail.

From the perspective of the contribution in terms of social cohesion and social capital, it is therefore evident that various tax concessions (subsidized tax regimes are expressly provided for sports activities) and high management costs negatively affect the attribution, in monetary terms, of the value-added to the government. The value-added through tax contributions is on average less than 3%. It must also be factored in that football players are, generally, taxed on their salaries at high levels by national governments. Zlatan Ibrahimovic, upon moving to Paris Saint-Germain in France, became subject to the country’s 75% rate of income tax on high earners and famously claimed to be doing “more for France than President of the Republic, François Hollande”.

This direct contribution in terms of taxes is balanced, however, by multiple indirect outcomes of the sporting activity of the clubs, in terms of tourism (infrastructural development in the areas adjacent to the stadia, and the management of supporters’ trips), the use of activities related to football (marketing, merchandising, broadcasting, journalism, and many others). It is therefore not surprising that almost all European football clubs are mainly owned by private investors [23], rather than institutional investors, as private individual investors are more likely to be interested in the visibility granted by the ownership status of clubs, and only secondarily in the financial performance of the clubs, as they can indirectly have other types of gain. Minority investors, on the other hand, can be identified mainly in the types of speculators, as the fluctuations in the share prices of listed football clubs are notoriously very high and often linked to on-field success [25].

The distribution of the value-added to creditors (in terms of interest expense) and the recognition of amortization/depreciation for the incurred expenses of multi-annual production factors have a significant impact. Among the latter, the amortization of intangibles (brands, copyrights, goodwill) is particularly relevant since only some of the clubs analysed can amortize the costs relating to stadia in their income statements (Brondby, Celtic, Porto, Borussia Dortmund, Olympique Lyonnais, Benfica, and Juventus), as in the case of the other clubs, the stadia are owned by the municipalities, or directly/indirectly by the State, which then collects rent from the clubs for the use of the facilities. This indicates a wider net positive value-added by the clubs and one which cements them as part of the economic ecosystem in their local and national areas.

4. Discussion

This research frames the idea of value-added in a broad context that is suitable for football clubs and the level at which they work across the economies and societies in which they are located. Football is big business and is, in financial terms, a clear net contributor to society. In many ways, this contribution is a wealth transfer from private investors in these listed clubs, as these investors often take on the main burden of financial risk for the smallest return (or often a financial loss). This is knowledge that investors or speculators will have access to prior to making investments in publicly listed football clubs, and so opens a debate as to the motivation behind their investments. As purely financial investments, football clubs are a fairly poor (in terms of lack of dividend distribution) and a highly speculative option. The link between on-field success and financial return for investors also suggests that heavy initial investment in playing staff represents a gamble of sorts for investors.

This research therefore reinforces the findings of previous literature [77,78,79,80] that the main focus of investors in these clubs is likely to be in encouraging sporting success, rather than financial gain. That the bulk of value-added is spent on the athletes themselves is indicative of investors looking to build on-pitch success rather than shorter-term financial returns. Here, too, is an interesting discussion point around the financial reward that the athletes receive. Elite footballers are often portrayed as overpaid, but they are, in essence, the means of production in the footballing economy and, in this context, the footballing economy is unusual in capitalist societies in that the means of production receive the bulk of financial reward, as opposed to the rentier class of investors behind the scenes [25].

Finally, it must also be taken into account that the sample of this study, though robust, is only drawn from the upper end of European football clubs [26,27,28,29,30,31]. Were data made available for lower league football clubs or those from developing economies, it would be of interest to replicate this study to understand how generalizable these findings are. This is a suggested area of future study.

Author Contributions

A.F. contributed to write all the paragraphs of the entire paper. L.J.M.-D.-S., H.M.H. and D.R. contributed to the paragraph related to the materials methodology, to the definition of the results, providing also the relevant literature review and contributed to the identification of the results. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Wels, S. The Olympic Spirit: 100 Years of the Game; Collins Publishers: San Francisco, CA, USA, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Chatziefstathiou, D.; Henry, I. Hellenism and Olympism: Pierre de Coubertin and the Greek challenge to the early Olympic movement. Sport Hist. 2007, 27, 24–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jun, P.E.I. YOG: Expain for the New Idea of Olympic Spirit. J. Nanjing Inst. Phys. Educ. (Soc. Sci.) 2010, 2. Available online: http://en.cnki.com.cn/Article_en/CJFDTotal-LJTB201002006.htm (accessed on 17 November 2020).

- MacAloon, J.J. This Great Symbol: Pierre de Coubertin and the Origins of the Modern Olympic Games; Routledge: Abingdon, UK, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Bollansee, J. Aristotle and Hermippos of Smyrna on the Foundation of the Olympic Games and the Institution of the Sacred Truce. Mnemosyne 1999, 52, 562–567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, J.M.; Ingham, A.G. On the waterfront: Retrospectives on the relationship between sport and communities. Sociol. Sport J. 2003, 20, 252–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hedlund, D.P. Creating value through membership and participation in sport fan consumption communities. Eur. Sport Manag. Q. 2014, 14, 50–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corral, C.D.; Pérez-Turpin, J.A.; Vidal, A.M.; Padorno, C.M.; Patiño, M.J.; Molina, A.G. Principles of the olympic movement. J. Hum. Sport Exerc. 2010, 5, 3–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manni, F.; Faccia, A. The Business Going Concern: Financial Return and Social Expectations. In Sustainable Development and Social Responsibility; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2020; Volume 1, pp. 201–213. [Google Scholar]

- Gruppo Bilancio Sociale. 2020. Available online: http://www.gruppobilanciosociale.org/ (accessed on 5 November 2020).

- Mei, O.G. Metodologie Quantitative di Determinazione del Valore Aggiunto Aziendale; Libreria goliardica: Trieste, Italy, 1986. [Google Scholar]

- Gabrovec Mei, O.; Vitezi, N. Social and environmental responsibility–accountability and reporting in the EU. In Proceedings of the IIA International Conference Economic System of the European Union and Adjustment of the Republic of Croatia, Lovran, Croatia, 8 April 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Peroni, F.; Di Guardo, A.; Gabrovec Mei, O. Bilancio Sociale 2008 dell’Università Degli Studi di Trieste; Introduzione e Premessa Metodologica; EUT Edizioni Università di Trieste: Trieste, Italy, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Manni, F. Il bilancio sociale nello sport professionistico. Econ. Aziend. Online 2012, 12, 59–68. [Google Scholar]

- Manni, F. Riflessioni sul bilancio sociale nel contesto non profit. Econ. Aziend. Online 2010, 1, 59–65. [Google Scholar]

- Manni, F. Responsabilità Sociale e Informazione Esterna D’impresa: Problemi, Esperienze e Prospettive del Bilancio Sociale; G. Giappichelli: Turin, Italy, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Buscarini, C.; Manni, F.; Marano, M. La Responsabilità Sociale e il Bilancio Sociale Delle Organizzazioni Dello Sport; FrancoAngeli: Milan, Italy, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Manni, F. Considerazioni sul Bilancio Sociale in Ambito Pubblico; Aracne: Rome, Italy, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Manni, F. Economicità e Partecipazione: Il Contributo del Bilancio Sociale al Governo Dell’azienda Composta Pubblica; Aracne: Rome, Italy, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Manni, F. Il Bilancio Sociale: Strumento di Analisi dei Profili di Economicità per un Giudizio di Responsabilità Sociale; Aracne: Rome, Italy, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Faccia, A.; Manni, F. Financial Accounting: Text and Cases; Aracne: Rome, Italy, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Sung, S.H.; Hong, D.S.; Sul, S.Y. How We Can Enhance Spectator Attendance for the Sustainable Development of Sport in the Era of Uncertainty: A Re-Examination of Competitive Balance. Sustainability 2020, 12, 7086. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faccia, A.; Petratos, P.; Moşteanu, N.R.; Mataruna-Dos-Santos, L.J. Stadium Ownership and performance: Evidence from European Football Clubs. Eur. Sport Manag. Q. 2020. under review. [Google Scholar]

- Rohde, M.; Breuer, C. The market for football club investors: A review of theory and empirical evidence from professional European football. Eur. Sport Manag. Q. 2017, 17, 265–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lago, U.; Simmons, R.; Szymanski, S. The Financial Crisis in European Football: An Introduction. In Football Economics and Policy; Palgrave Macmillan: London, UK, 2010; pp. 151–161. [Google Scholar]

- Dong, H.; Yim, B.; Zhang, J.J. Organizational Structure, Public-Private Relationships, and Operational Performance of Large-Scale Stadiums: Evidence from Local Governments in China. Sustainability 2020, 12, 8002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mataruna-Dos-Santos, L.J.; Zardini-Filho, C.E.; Milla, A.C. Youth Olympic games: Using marketing tools to analyse the reality of GCC countries beyond Agenda 2020. J. Hum. Sport Exerc. 2019, 14, S391–S411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mataruna-Dos-Santos, L.J.; Khan, M.S.; Ahmed, M.A.; Al Shibini, A. Contemporary scenario of Muslim women and sport in the United Arab Emirates: Pathways to the vision 2021. Olimp. J. Olymp. Stud. 2018, 2, 449–474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mataruna-Dos-Santos, L.J.; Guimarães-Mataruna, A.F.; Range, D. Paralympians competing in the Olympic games and the potential implications for the Paralympic games. Braz. J. Educ. Technol. Soc. 2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parry, J. Sport and Olympism: Universals and multiculturalism. J. Philos. Sport 2006, 33, 188–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simon, R.L. Fair Play: The Ethics of Sport; Routledge: Abingdon, UK, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Lumpkin, A.; Stoll, S.K.; Beller, J.M. Sport Ethics: Applications for Fair Play, 2nd ed.; WCB/McGraw-Hill: London, UK, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Brock, S.J.; Hastie, P.A. Students’ conceptions of fair play in sport education. Achper Aust. Healthy Lifestyles J. 2007, 54, 11–15. [Google Scholar]

- Heinilä, K. Sport and International Understanding—A Contradiction in Terms? Sociol. Sport J. 1985, 2, 240–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anand, P.B.; Gasper, D.; Deneulin, S.; Townsend, N. Public goods, global public goods and the common good. Int. J. Soc. Econ. 2007, 34, 19–36. [Google Scholar]

- Etzioni, A. Common good. In The Encyclopedia of Political Thought; Wiley-Blackwel: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2014; pp. 603–610. [Google Scholar]

- Argandoña, A. The stakeholder theory and the common good. J. Bus. Ethics 1998, 17, 1093–1102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daly, H.E.; Cobb, J.B., Jr.; Cobb, J.B. For the Common Good: Redirecting the Economy toward Community, the Environment, and a Sustainable Future (No. 73); Beacon Press: Boston, MA, USA, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Lutz, M.A. Economics for the Common Good: Two Centuries of Economic Thought in the Humanist Tradition; Routledge: Abingdon, UK, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Almond, G.A. Political theory and political science. Am. Political Sci. Rev. 1966, 60, 869–879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watson, G.G.; Collis, R. Adolescent values in sport: A case of conflicting interests. Int. Rev. Sport Sociol. 1982, 17, 73–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pescosolido, A.T.; Saavedra, R. Cohesion and sports teams: A review. Small Group Res. 2012, 43, 744–758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- King, N. Sport Policy and Governance; Routledge: Abingdon, UK, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Maskin, E.; Sen, A. The Arrow Impossibility Theorem; Columbia University Press: New York, NY, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Haigh, J. Uses and limitations of mathematics in sport. Ima J. Manag. Math. 2009, 20, 97–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sandroni, A.; Sandroni, A. A Comment on Arrow’s Impossibility Theorem. Be J. Theor. Econ. 2020. ahead-of-print. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tanaka, Y. On the equivalence of the Arrow impossibility theorem and the Brouwer fixed point theorem. Appl. Math. Comput. 2006, 172, 1303–1314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sen, A.; Maskin, E. Arrow and the impossibility theorem. Arrow Impos. 2014, 8, 29–42. [Google Scholar]

- Trendafilova, S.; Babiak, K.; Heinze, K. Corporate social responsibility and environmental sustainability: Why professional sport is greening the playing field. Sport Manag. Rev. 2013, 16, 298–313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schulenkorf, N. Sustainable community development through sport and events: A conceptual framework for sport-for-development projects. Sport Manag. Rev. 2012, 15, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loland, S. Olympic sport and the ideal of sustainable development. J. Philos. Sport 2006, 33, 144–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bernstein, E.A. Law & (and) Economics and the Structure of Value Adding Contracts: A Contract Lawyer’s View of the Law & (and) Economics Literature. Or. L. Rev. 1995, 74, 189. [Google Scholar]

- Mukhopadhyay, S.K.; Zhu, X.; Yue, X. Optimal contract design for mixed channels under information asymmetry. Prod. Oper. Manag. 2008, 17, 641–650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kennell, N.M. The Gymnasium of Virtue: Education & Culture in Ancient Sparta; Univ. of North Carolina Press: Chapel Hill, NC, USA, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Cilin, L. Prospects for Sport Buildings of 2008 Olympic from the Structure of Olymplic Gymnasium in the Last Half-Century. Build. Struct. 2003, 1. Available online: http://en.cnki.com.cn/Article_en/CJFDTotal-JCJG200301015.htm (accessed on 17 November 2020).

- Lempa, H. Beyond the Gymnasium: Educating the Middle-Class Bodies in Classical Germany; Lexington Books: Lanham, MD, USA, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Richau, L.; Emrich, E.; Follert, F. Quid Pro Quo! Organization Theoretical Remarks about FIFA’s Legitimization under Blatter and Infantino. Econ. Voice 2019, 16, 1–9. Available online: https://www.degruyter.com/view/journals/ev/16/1/article-20190014.xml?language=en) (accessed on 17 November 2020).

- Follert, F.; Richau, L.; Emrich, E.; Pierdzioch, C. Collective Decision-Making: FIFA from the Perspective of Public Choice. Econ. Voice 2020. Available online: https://www.degruyter.com/view/journals/ev/ahead-of-print/article-10.1515-ev-2019-0031/article-10.1515-ev-2019-0031.xml1 (accessed on 17 November 2020). [CrossRef]

- Kulczycki, W.; Koenigstorfer, J. Why Sponsors should Worry about Corruption as a Mega Sport Event Syndrome. Eur. Sport Manag. Q. 2016, 16, 545–574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bayle, E.; Rayner, H. Sociology of a Scandal: The Emergence of ‘FIFAgate’. Soccer Soc. 2018, 19, 593–611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brooks, G.; Aleem, A.; Button, M. Fraud, Corruption and Sport; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Maennig, W. Corruption in international sports and sport management: Forms, tendencies, extent and countermeasures. Eur. Sport Manag. Quartely 2005, 5, 187–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- David, P. A Guide to the World Anti-Doping Code; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Chappelet, J.L.; Clausen, J.; Bayle, E. Governance of international sports federations. In Routledge Handbook of Sport Governance; Taylor & Francis: Oxfordshire, UK, 2019; p. 114. [Google Scholar]

- Moriconi, M. Deconstructing match-fixing: A holistic framework for sport integrity policies. Crime Law Soc. Chang. 2020, 3, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moriconi, M.; de Cima, C. Betting practices among players in Portuguese championships: From cultural to illegal behaviours. J. Gambl. Stud. 2020, 36, 161–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krieger, J.; Wassong, S. Origins and key turning points in the governance of the Olympic movement. In Routledge Handbook of the Olympic and Paralympic Games; Routledge: Abingdon, UK, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Besnier, N.; Guinness, D.; Lowe, E.D.; Schnegg, M. 9 Global Sport Industries, Comparison, and Economies of Scales. In Comparing Cultures Innovations in Comparative Ethnography; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2020; p. 201. [Google Scholar]

- Alaminos, D.; Fernández, M.Á. Why do football clubs fail financially? A financial distress prediction model for European professional football industry. PLoS ONE 2019, 14, e0225989. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hagen, J.; Cunha, M.N. The History of Investing in Football and Factors Affecting Stock Price of Listed Football Clubs. Int. J. Financ. Manag. 2019, 9, 31–41. [Google Scholar]

- Huth, C. Who invests in financial instruments of sport clubs? An empirical analysis of actual and potential individual investors of professional European football clubs. Eur. Sport Manag. Q. 2020, 20, 500–519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caselli, G.P. L’economia Dello Sport Nella Società Moderna; Treccani Editore: Rome, Italy, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Wagner, F.; Preuss, H.; Könecke, T. Measuring competitive intensity in sports leagues. Sport Bus. Manag. Int. J. 2020, 10, 599–620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sloane, P.J. The European model of sport. In Handbook on the Economics of Sport; Edward Elgar: Cheltenham, UK, 2006; p. 299. [Google Scholar]

- Rodríguez, P.L. The Economics of Sport. Stud. Appl. Econ. 2020, 30, 387–418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoon, K.P.; Sedaghat, M. Rank power analysis for comparative strength of professional sports franchises. J. Appl. Bus. Res. 2020, 36, 181–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rohde, M.; Breuer, C. Competing by investments or efficiency? Exploring financial and sporting efficiency of club ownership structures in European football. Sport Manag. Rev. 2018, 21, 563–581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Millward, P. New football directors in the twenty-first century: Profit and revenue in the English Premier League’s transnational age. Leis. Stud. 2013, 32, 399–414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mosteanu, N.R.; Faccia, A.; Ansari, A.; Shamout, M.D.; Capitanio, F. sustainability integration in supply chain management through systematic literature review. Calitatea 2020, 21, 117–123. [Google Scholar]

- Darville, J.; Faccia, A. An Analysis of Corporate Social Responsibility and Role of Intermediaries for Value-Added Services. In Sustainable Development and Social Responsibility; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2020; Volume 1, pp. 23–34. [Google Scholar]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).