Results and Lessons Learned from Assessing 50 Industrial Parks in Eight Countries against the International Framework for Eco-Industrial Parks

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Theoretical Framework

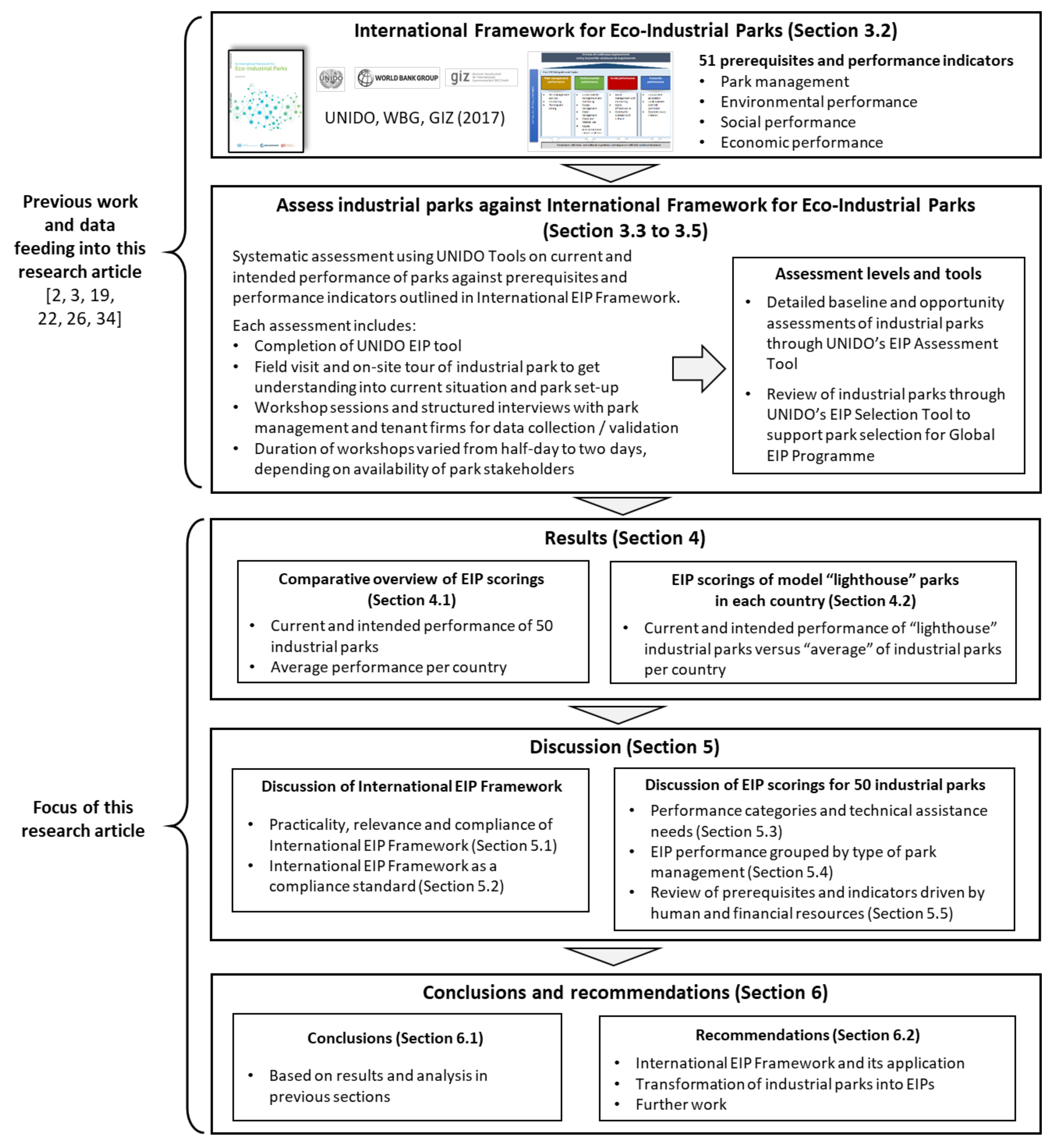

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Methodology to Assess EIP Performance of Industrial Parks and to Evaluate Results

3.2. International Framework for Eco-Industrial Parks

3.3. UNIDO’s EIP Assessment Tool

- A review of available national databases and consultation with national stakeholders is undertaken to arrive at consolidating list of existing industrial parks in the country. The long-list of industrial parks identified is screened in order to obtain a short-list of industrial parks. Screening criteria are unique for each country and national context, but generally include: the park is operational and an existing “brownfield” development; contact information is available; the park is in an accessible location;

- The pre-selection of industrial parks is based on minimum selection criteria (e.g., a distinct park management entity exists, the park area is larger than 100 hectares, a sufficient number of firms are operating in park, and there are clear signs that industries and park management want to work with the project team to improve their environmental, social, and economic performance);

- The prioritization of pre-selected industrial parks is based on a set of qualitative criteria formulated as statements. Each statement needs to be answered for the pre-selected parks, by giving scores from 1 (totally incorrect) to 6 (totally true). The weight of each prioritization statement can be changed to reflect specific country priorities. Prioritization statements cover park management, environment/social/economic aspects, replication, and visibility.

- Colombia (5 industrial parks): Parque Industrial Malambo (PIMSA), Zona Franca de Occidente, Zona Franca La Candelaria, Zona Franca del Cauca, and Zona Franca del Pacífico;

- Egypt (3 industrial parks): El Robbiki Industrial Park (IP), Polaris International and Al Zamil IP, and SIDC Industrial Park (in the Suez Canal Special Economic Zone (SEZ));

- Indonesia (11 industrial parks): Batamindo IP, Bintan Inti, BSBcity, Gresik, Kabil IP, KIIC, Maspion, MM2100, Modern Cikande, Safe n Lock, and Suryacipta;

- Nigeria (2 industrial parks): Calabar Free Trade Zone and Lekki Free Zone;

- Peru (6 industrial parks): Adepia IP, Ancón Private IP, Indupark, La Chutana IP, Lurin IZ, and Sector 62 IP;

- South Africa (11 industrial parks): Atlantis SEZ, Babelegi IP, Bodirelo IP, Botshabelo IP, Dube TradePort SEZ, East London IDZ, Ekandustria IP, Puthaditjaba IP, Rosslyn Automotive Supplier Park, Seshego IP, and Vulindlela IP;

- Ukraine (4 industrial parks): IP Agromash (Zaporizhzhia), IP BTsVAK, IP Chemical metallurgical plant, and IP Patriot;

- Viet Nam (8 industrial parks): Amata, Deep C1&C2, Hiep Phuoc, Hoa Khanh, Khanh Phu, Long Thanh, Pho Noi A, and Tra Noc 1&2.

3.4. EIP Scoring Method

- Park management (6 prerequisites, 3 performance indicators): Park management services, monitoring, and planning and zoning;

- Environmental performance (6 prerequisites, 14 performance indicators): Environmental management and monitoring, energy management, water management, waste and material use, and natural environment and climate resilience;

- Social performance (2 prerequisites, 11 performance indicators): Social management and monitoring, social infrastructure, and community outreach and dialogue;

- Economic performance (4 prerequisites, 5 performance indicators): Employment creation, local business and SME promotion, and economic value creation.

- “Yes”: Industrial park fully meets the prerequisite/performance indicator;

- “No”: Industrial park does not fully meet the prerequisite/performance indicator;

- “Partly”: Industrial park meet large parts of the prerequisite and has made efforts to work on this, but the requisite is not yet fully met. The “Partly” rating is only possible for prerequisites, as performance indicators include percentage levels which are either met or not;

- “To be confirmed”: Further data is required to decide on whether or not park meets the prerequisite/performance indicator;

- “Not applicable”: Prerequisite/performance indicator is not applicable to the industrial park under analysis (e.g., park does not have firms employing more than 250 people).

3.5. Analysis of Practicality, Relevance, and Compliance Levels

4. Results

4.1. Comparative Overview of EIP Scorings of 50 Industrial Parks in Eight Countries

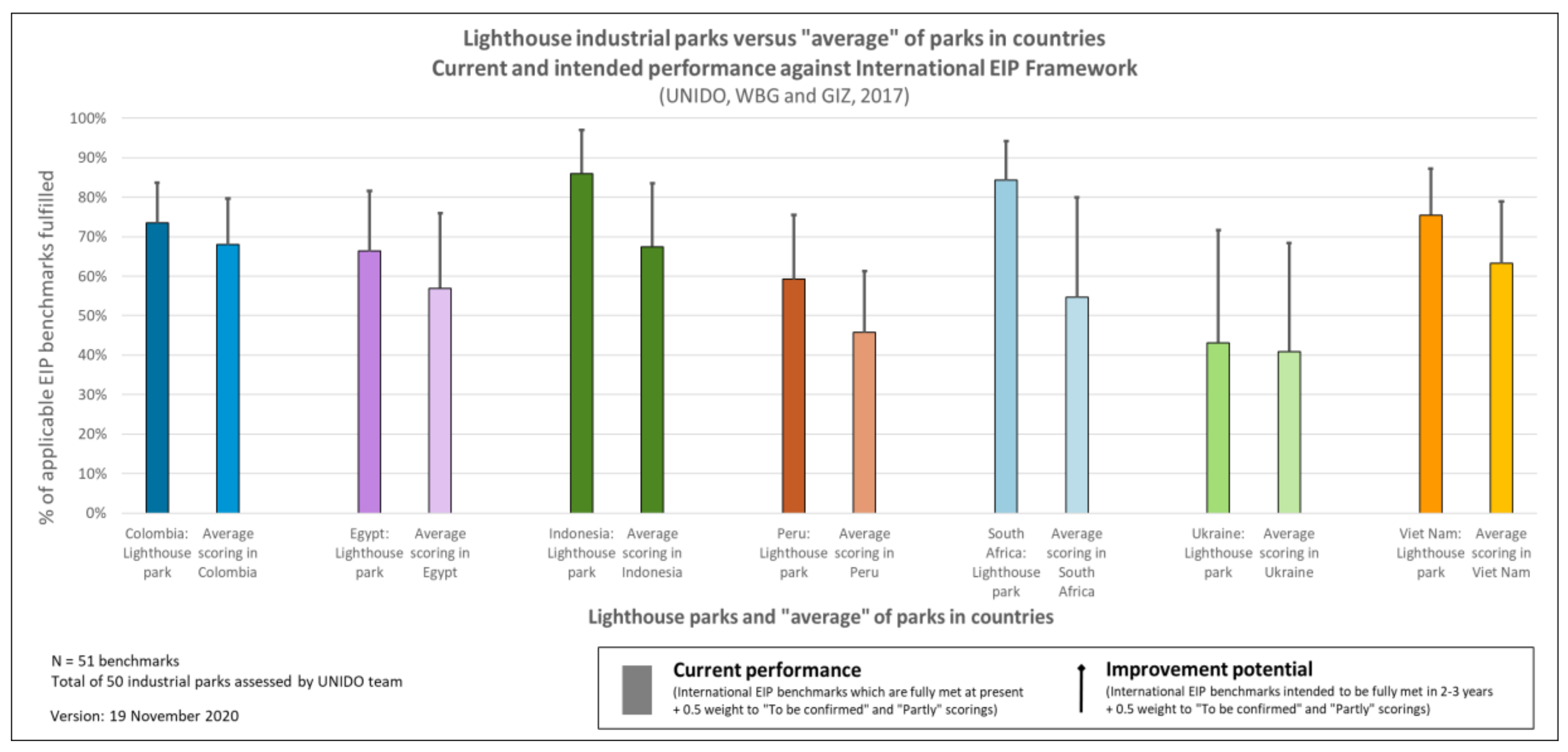

4.2. EIP Scorings of Model “Lighthouse” Parks in Each Country

- A high interest and commitment of park management towards their transformation into an eco-industrial park;

- Sufficient resources (e.g., human, financial) of the park management/developer to work towards an eco-industrial park;

- The total number and the diversity of industries located in the park is sufficient to develop industrial synergies and to undertake cleaner production opportunity assessments with individual firms;

- The industrial activities present in the park are representative of the national economic landscape;

- The industrial park is sufficiently large and productive to be visible at a national scale;

- The industrial park is aligned with existing policies and priorities of local, regional, and national government.

5. Discussion

5.1. Practicality, Relevance, and Compliance of Prerequisites and Indicators of International EIP Framework

5.1.1. Practicality of EIP Prerequisites and Performance Indicators

- At least 75% of all firms in industrial park with more than 250 employees have a harassment prevention and response system in place (55% practicality);

- At least 80% of the surveyed employees report satisfaction with social infrastructure (37% practicality);

- At least 20% of the female workforce benefit from available supporting infrastructure/programs for skills development (56% practicality);

- At least 80% of surveyed community members are satisfied with the community dialogue (47% practicality);

- At least 25% of resident firms use local suppliers or service providers for at least 80% of their total procurement value (46% practicality).

5.1.2. Relevance of EIP Prerequisites and Performance Indicators

5.1.3. Compliance Levels of EIP Prerequisites and Performance Indicators

5.2. The International EIP Framework as a Compliance Standard

5.3. Performance Categories and Technical Assistance Needs

- Energy (28%);

- Local community outreach (28%);

- Environmental management and monitoring (30%);

- Park monitoring and risk management (31%);

- Waste and material use (32%);

- Climate change and the natural environment (38%).

- Employment generation (87%);

- Economic value creation (78%);

- Basic park management services (75%).

- The technical assistance for the EIP transformation generally covers training and capacity building, technical advisory services, facilitation of investment opportunities, and policy support. Specific prerequisites and performance indicators under park management, economic, environmental, and social performance that the industrial park does not fulfill indicate topics for technical assistance. Therefore, the analysis of the compliance scorings by category and topic at global and country levels will be used by GEIPP as an input to determine the type and level of required assistance for specific countries;

- The main entry point for the technical assistance to the parks on most topics of the International EIP Framework is the park management entity (“bottom-up approach”). However, for a number of topics there is potential key role for government agencies to support the EIP transformation through policy support (“top-down approach”). Key examples include the strengthening of policy support on the planning and zoning of industrial parks in a country, expanding the requirements and incentives to industrial parks/firms to address and adapt to climate change, and streamlining regulations to facilitate the safe reuse and recycling of industrial by-products and effluent streams between tenant firms. These are often regulatory challenges faced by industrial park management and tenant firms [16,17,19,26,34,40,41];

- For the EIP transformation and technical assistance to the parks it is key to focus on the implementation of both short-term (up to 2 years) as well as medium-/long-term initiatives (up to 5 years). The short-term initiatives should focus on low-cost and “quick-win” measures to deliver concrete benefits, thereby secure ongoing commitment and interest amongst park stakeholders of the EIP concept. The medium-term initiatives should focus more on investment opportunities which deliver strategic and substantial benefits to the park and its stakeholders. In this regard, Appendix B provides an indication on which prerequisites and performance indicators of the International EIP Framework are largely driven by either human efforts or financial investments;

- At some industrial parks, a low current performance as well as a low improvement potential for a specific topic is identified. In such cases, awareness raising to park management on EIP benefits of these topics is needed for a commitment to a higher intended performance level.

5.4. Performance Measured against the International EIP Framework, Grouped by Type of Park Management

5.5. Review of Prerequisites and Performance Indicators Driven by Human and Financial Resources

6. Conclusions and Recommendations

6.1. Conclusions

6.2. Recommendations

- A key recommendation is for UNIDO, the WBG, and the GIZ to consider and follow-up on the prerequisites and performance indicators recommended for modification in the next revision of the International EIP Framework.

- The analysis of the number of “To be confirmed” ratings of the 51 prerequisites and performance indicators outlined in the International EIP Framework highlights the need for park management and tenant firms to extend their data collection systems, in particular in the “social performance” category. The improvement of existing data collection systems and subsequent use for decision making is a recommendation, also with regards to the type of technical assistance which is provided as part of the GEIPP.

- The EIP assessments undertaken to date provide insights into the current and intended performance of industrial parks and their specific technical assistance needs. It is therefore recommended that the EIP assessment results are analyzed in the context of each country to formulate customized approaches for technical assistance to the parks and to guide the planning and implementation of country-level GEIPP activities. For the EIP transformation across all eight countries, it is recommended that the topics of the International EIP Framework which have the lowest current compliance levels are prioritized, as highlighted in this article.

- Business-oriented approaches should be promoted and embedded with parks managed solely by the public sector. Examples include the streamlining of decision-making processes within park management without unnecessary government bureaucracies, park management services which meet the needs of resident firms, and addressing key common challenges facing tenant firms (e.g., secure water and energy supply, shared utilities, and infrastructures).

- Although the main entry point for the technical assistance to the parks is the park management entity, it is recommended that technical assistance providers (such as UNIDO) and industrial parks work closely with government agencies in the countries on the EIP transformation through conducive policies (“top-down approaches”) on specific topics. Examples of these topics include the planning and zoning of industrial parks, incentives for companies to improve their energy efficiency, climate change mitigation and adaptation, and streamlining regulations to facilitate the safe reuse and recycling of industrial by-products and effluent streams.

- This research article reports on the work with industrial parks in transition and developing countries. It is recommended that further EIP assessments are undertaken with industrial parks in countries in Europe, North America, and Oceania. Expanding the pool of assessed parks to more countries would provide further comparative insights in applying the International EIP Framework in multiple national/economic contexts and to assess similarities/differences in their EIP performance levels.

- Further research and analysis into the root-causes of the differences and similarities of the EIP scorings at industrial park and country levels is desired (e.g., sampling, policy and regulations, access-to-finance, human and technical capabilities, local and national conditions).

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

Appendix A.1. Pre-Selecting Industrial Parks for Their Participation in the EIP Assessments

| Pre-Selection Criteria | Description |

|---|---|

| Park management | A distinct park management entity or alternative agency, where applicable, exists to handle park planning, operations and management, and monitoring. |

| Size | The park area is larger than 100 hectares |

| Industrial activities | A sufficient number of industries (>15) with distinct productive activities (e.g., not warehouses) are located in the industrial park. |

| Industrial park supports SMEs, either directly in industrial park or indirectly outside the park or through large corporations in the park. | |

| Law and regulation | No signs of criminal activities or illegal businesses in the industrial park (difficulties to comply with environmental or social norms can be addressed by the EIP project). |

| Secrecy and confidentiality | No very sensitive and confidential industrial activities in the park. |

| Risk | The industrial park is not located in a very sensitive or high-risk area (e.g., flood-prone). |

| Location | The industrial park can be easily accessed by practitioners who will work on the EIP project (e.g., national and international consultants). |

| Commitment | There are clear signs that industries and park management want to work with project team to improve the environmental, social, and economic performances of the industrial park. |

Appendix A.2. Prioritization of Industrial Parks for Their Participation in the EIP Assessments

| Prioritization Criteria | Description |

|---|---|

| Park management | The park management/developer has sufficient resources (e.g., human, financial) to work towards an EIP. |

| The industrial park is designed according to available master planning documents (e.g., zoning of infrastructure and utilities). | |

| The park management demonstrates a clear commitment and willingness to work on the EIP project (rapid answer to mail, enthusiastic people, and commitment from senior park management staff, etc.). | |

| Environmental aspects | The total number (and the diversity) of industries located in the park is sufficient to envisage developing industrial synergies. |

| It is technically possible to improve the environmental aspects of the industrial park (e.g., free space for construction of wastewater treatment plant, potential for renewable electricity generation). | |

| The park management and the industries demonstrate a clear willingness to develop resource efficiency and cleaner production. | |

| Social aspects | The reputation of the park is sufficiently good to allow for the development of long-term and advanced community and/or government collaborations. |

| The industries and the park management take care of labor condition (e.g., working conditions comply with national and sectoral norms). | |

| Park management and tenant companies show commitment to improve gender equality. | |

| Economic aspects | Park management and industries have capacity to invest (or attract investment) in the development of new infrastructures or the modification existing infrastructures and utilities. |

| The industrial park stimulates local economy (i.e., attract industries, contribute to local business development and job creation, etc.). | |

| Replicability | The industrial activities present in the park are representative of the national economic landscape. |

| The size of companies (in terms of number of workers) and of the industrial park (in terms of land area) is representative of their national averages. | |

| The features (e.g., tax regime, geographic location) of the industrial park are representative of other industrial parks in the country. | |

| Developer/management company operates more than one industrial park in the country or internationally. | |

| Visibility | The industrial park is sufficiently large and productive to be visible at a national scale. |

| The industrial park has significant potential for collaborations with other sustainable development projects in the country. | |

| The industrial park is aligned with existing policies and priorities of local, regional, and national government | |

| Stakeholders implied in the EIP development would be interested in sharing their experience (e.g., participation in conferences, workshop, interviews). |

Appendix B

| Category | Topic | Description/Requirement | Review of Potential Cost Implications of Prerequisites and Performance Indicators | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Largely Driven by Human Efforts | Largely Driven by Financial Investments | |||

| Park management | Prerequisites | |||

| Park management services | A distinct park management entity (or alternative agency, where applicable) exists to handle park planning, operations and management, and monitoring. | X | ||

Park management entity to manage and maintain the industrial park property, common infrastructure, and services as prescribed in the tenant contract and the park’s Master Plan. This should include, but is not limited to the following:

| X | |||

| Monitoring and risk management | Park management entity maintains a monitoring system in place, tracking:

| X | ||

| Where required, park management has a plan in place to react to possible negative impacts due to climate change risks (heat waves and droughts, storms and floodwater events). All adaption needs for infrastructure and services are identified and in place for the industrial estate to protect against climate change risks and potential damages. | X | |||

| Park management entity has a functioning system in place to comply with local/national regulations and international standards applicable to the industrial park. Park management informs compliance by resident firms including compliance information that firms share with the park management entity. | X | |||

| Planning and zoning | A Master Plan (or equivalent planning document) for any new and existing industrial park has been developed and is reviewed periodically (and updated if required), including the following core elements:

| X | ||

| Performance indicators | ||||

| Park management services | 100% of firms in the industrial park have signed a residency contract/ park charter/code of conduct (depending on what is legally binding on park firms according to the existing legislation in the country); and additional legally binding arrangements that empower the park management entity to perform its responsibilities and tasks and charge fees (sometimes absorbed in rental fees) for common services. This may include transparent fees for services pertaining to the achievement of EIP performance targets. | X | ||

| At least 75% of resident firms indicate satisfaction with regards to the provision of services and common infrastructure by the park management’s entity (or alternative agency, where applicable). | X | |||

| Monitoring and risk management | At least every six months, the park management entity monitors and prepares consolidated reports regarding the achievement of target values (as documented in this framework) to encompass the following:

| X | ||

| Environmental performance | Prerequisites | |||

| Management and monitoring | Park management entity operates an environmental/energy management system in line with internationally certified standards, monitoring park performance and supporting resident firms in the maintenance of their own firm-level management systems. | X | ||

| Energy | Supporting programs and documents are in place to improve the energy efficiency of resident firms, especially for the top 50% of major energy-consuming businesses in the park. | X | ||

| An industrial heat-recovery strategy is in place to investigate opportunities for heat and energy recovery for the major energy-consuming firms in the park. (Typically, these are firms that individually consume at least 10–20% of the total firm-level energy consumption). | X | |||

| Water | Park management entity has demonstrable plans and (preferably) prior documented evidence to increase water reuse in the short and medium term. This would be achieved by either reuse of industrial effluents, or by rainwater/storm water collection. | X | ||

| Climate change and the natural environment | A program is established to monitor, mitigate, and/or minimize greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions, such as carbon dioxide (CO2), methane (CH4), nitrogen oxide (NOx), and so on. There is clear evidence of steps taken to introduce mitigation activities. | X | ||

| The park management entity has a plan in place to assess operational environmental impacts and aims to limit the impact on prioritized local ecosystem services. | X | |||

| Performance indicators | ||||

| Management and monitoring | At least 40% of resident firms with more than 250 employees have an environmental/energy management system in place that is in line with internationally certified standards. | X | ||

| Energy | At least 90% of combined park facilities and firm-level energy consumptions have metering and monitoring systems in place. | X | ||

| Total renewable energy use in the industrial park is equal to or greater than the annual national average energy mix. | X | |||

| Park management entity sets and works toward ambitious (beyond industry norms) maximum carbon intensity targets (maximum kilograms of carbon dioxide equivalent (kg CO2-eq)/kilowatt hour (kWh) for the park and its residents. Targets should be established for the short, medium, and long term, in line with local norms and industry sector benchmarks. | X | |||

| Park management entity sets and works toward ambitious maximum energy intensity targets per production unit (kWh/$ turnover) for the park and its residents. Targets should be established for the short, medium, and long term, in line with local norms and industry sector benchmarks. | X | |||

| Water | 100% of the total water demand from firms in the industrial park does not have significant negative impacts on local water sources or local communities. | X | ||

| At least 95% of industrial wastewater generated by the industrial park and resident firms is treated to appropriate environmental standards. | X | |||

| At least 50% of total industrial wastewater from firms in the park is reused responsibly within or outside the industrial park. | X | |||

| Waste and material use | At least 20% of solid waste generated by firms is reused by other firms, neighboring communities, or municipalities. | X | ||

| 100% of firms in the park appropriately handle, store, transport, and dispose of toxic and hazardous materials. | X | |||

| Less than 50% of wastes generated by firms in the industrial park goes to landfills. | X | |||

| Climate change and the natural environment | At least 5% of open space in the park is used for native flora and fauna. | X | ||

| At least 50% of firms in park have pollution prevention and emission reduction strategies to reduce the intensity and mass flow of pollution/emission release beyond national regulations. | X | |||

| At least 30% of the largest polluters in industrial park have a risk management framework in place that: (a) identifies the aspects which have an impact on the environment; and (b) assign a level of significance to each environmental aspect. | X | |||

| Social performance | Prerequisites | |||

| Social management systems | Dedicated personnel exist (as part of the park management entity) to plan and manage social quality standards. | X | ||

| Social infrastructure | Essential primary social infrastructure has been adequately provided in the site master plan and is fully operational in the park. | X | ||

| Performance indicators | ||||

| Social management systems | At least 75% of all firms in the industrial park with more than 250 employees have a well-functioning OH&S management system in place. | X | ||

| 100% of grievances received by the park management entity are addressed within 90 days. | X | |||

| At least 60% of grievances received by the park management entity are brought to conclusion. | X | |||

| At least 75% of all firms in the industrial park with more than 250 employees have a code of conduct system in place to deal with grievances. | X | |||

| At least 75% of all firms in the industrial park with more than 250 employees have a harassment prevention and response system in place. | X | |||

| Social infrastructure | At least 80% of the surveyed employees report satisfaction with social infrastructure. | X | ||

| 100% of reported security and safety issues are adequately addressed within 30 days. | X | |||

| 75% of all firms in the industrial park with more than 250 employees have a program for skills/vocational training and development. | X | |||

| At least 20% of the female workforce benefit from available supporting infrastructure/programs for skills development. | X | |||

| Local community outreach | At least 80% of surveyed community members are satisfied with the community dialogue. | X | ||

| At least two outreach activities that are implemented by the park management entity annually are regarded as positive by over 80% of the surveyed community members. | X | |||

| Economic performance | Prerequisites | |||

| Employment generation | The park management entity has plans to generate specific numbers and types of jobs (including diversity and inclusiveness) in line with government targets. | X | ||

| Local business & SME promotion | The park management entity allows and promotes the establishment of SMEs that provide services and add value to park residents. | X | ||

| Economic value creation | A market demand and feasibility study, supported by a business plan, for specific “green” infrastructure and service offerings has been undertaken to justify planning and implementation in the industrial park. | X | ||

| Tracked by the park management entity, the industrial park fulfils relevant government targets, including domestic, foreign direct investment, and tax revenues. | X | |||

| Performance indicators | ||||

| Employment generation | At least 60% of total workers employed in industrial park live within daily commuting distance. | X | ||

| At least 25% of total firm workers in industrial park are employed through direct employment (that is, not employed on a fee-for-output basis or provided through a labor supply firm) and permanent contracts. | X | |||

| Local business and SME promotion | At least 25% of resident firms use local suppliers or service providers for at least 80% of their total procurement value. | X | ||

| At least 90% of total procurement value of the park management entity is supplied by local firms or service providers. | X | |||

| Economic value creation | On average, the occupancy rate of space available for resident firms was >50% over the last 5 years. | X | ||

Appendix C

| International EIP Framework Category | EIP Prerequisites and Performance Indicators | Root-Causes of Low Compliance with Prerequisites/Performance Indicators | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| At Least 7 out of 8 Countries Have Compliance ≤ 50%: | At Least 2 out of 8 Countries Have Compliance ≥ 50%: | Comments on Root-Causes for Low Compliance | ||

| Consider Modification of Prerequisite/Indicator | Compliance Seems Mainly with Industrial Park/Country Specific Conditions | |||

| Park management | Where required, park management has a plan in place to react to possible negative impacts due to climate change risks (heat waves and droughts, storms and floodwater events). | X | This is a binary prerequisite which should not be edited to increase compliance levels. it is important for EIPs to address this issue. | |

| At least every six months, park management entity monitors and prepares consolidated reports regarding the achievement of target values (as documented in this framework) to encompass the following: environmental performance; social performance; economic performance; and critical risk management at the level of the park. | X | Many parks assessed do not report periodically on their sustainability performance. It could be argued that the reporting frequency of six months should be changed to annually. | ||

| Environmental performance | Park management entity operates an environmental/energy management system in line with internationally certified standards, monitoring park performance and supporting resident firms in the maintenance of their own firm-level management systems. | X | This is a binary prerequisite which should not be edited to increase compliance levels. It is important for EIPs to address this issue. However, there the prerequisite could be rephrased to increase clarity (e.g., environmental and/or energy management system?) | |

| Supporting programs and documents are in place to improve the energy efficiency of resident firms, especially for the top 50% of major energy-consuming businesses in the park. | X | This is a binary prerequisite which should not be edited to increase compliance levels. It is important for EIPs to address this issue. | ||

| An industrial heat-recovery strategy is in place to investigate opportunities for heat and energy recovery for the major energy-consuming firms in the park. | X | Prerequisite is mostly relevant to very advanced industrial parks which have energy intensive heat streams. Heat recovery is mainly done at firm level, rather than at park level. | ||

| Park management entity has demonstrable plans and (preferably) prior documented evidence to increase water reuse in the short and medium term. This would be achieved by either reuse of industrial effluents, or by rainwater/storm water collection. | X | This is a binary prerequisite which should not be edited to increase compliance levels. It is important for EIPs to address this issue. | ||

| A program is established to monitor, mitigate, and/or minimize GHG emissions, such as carbon dioxide (CO2), methane (CH4), nitrogen oxide (NOx), and so on. | X | This is a binary prerequisite which should not be edited to increase compliance levels. It is important for EIPs to address this issue. | ||

| The park management entity has a plan in place to assess operational environmental impacts and aims to limit the impact on prioritized local ecosystem services. | X | This is a binary prerequisite which should not be edited to increase compliance levels. It is important for EIPs to address this issue. | ||

| Park management entity sets and works toward ambitious (beyond industry norms) maximum carbon intensity targets (maximum kilograms of carbon dioxide equivalent (kg CO2-eq)/kilowatt hour (kWh) for the park and its residents. | X | These two performance indicators are too ambitious for many industrial parks and require data that is most often not available. It is very difficult to obtain a meaningful data series over a time period to measure progress on this indicator. The number and types of firms in industrial park is not a constant factor. It will be very challenging to collect data to calculate indicators consistently and reliably. | ||

| Park management entity sets and works toward ambitious maximum energy intensity targets per production unit (kWh/$ turnover) for the park and its residents. | X | |||

| At least 50% of total industrial wastewater from firms in the park is reused responsibly within or outside the industrial park. | X | This performance level of this indicator seems too stringent for most industrial parks. | ||

| At least 20% of solid waste generated by firms is reused by other firms, neighboring communities, or municipalities. | X | Although this performance indicator could be clearer defined (e.g., distinguish between water reuse and recycling), it is important for EIPs to address this issue. | ||

| Less than 50% of wastes generated by firms in the industrial park goes to landfills. | X | Although this performance indicator could be clearer defined (e.g., indicator to cover both landfilling and waste burning without proper incineration infrastructure), it is important for EIPs to address this issue. | ||

| At least 50% of firms in the park have pollution prevention and emission reduction strategies to reduce the intensity and mass flow of pollution/emission release beyond national regulations. | X | Although the formulation of this performance indicator is relatively complex, it is important for EIPs to address this issue, although the ‘beyond national regulations’ reduces drastically its applicability. | ||

| Social performance | At least 75% of all firms in the industrial park with more than 250 employees have a harassment prevention and response system in place. | X | Low compliance levels across these social indicators may indicate that a large proportion of the assessed parks do not yet have the implementation mechanisms, data collection systems on OH&S and human resources, confidence, and/or capabilities to undertake the community outreach and dialogues. | |

| At least 80% of the surveyed employees report satisfaction with social infrastructure | X | |||

| At least 20% of the female workforce benefit from available supporting infrastructure/programs for skills development. | X | |||

| At least 80% of surveyed community members are satisfied with the community dialogue. | X | |||

| At least two outreach activities that are implemented by the park management entity annually are regarded as positive by over 80% of the surveyed community members. | X | |||

| Economic performance | A market demand and feasibility study, supported by a business plan, for specific “green” infrastructure and service offerings has been undertaken to justify planning and implementation in the industrial park. | X | Although the formulation of this performance indicator is relatively complex, it is important for EIPs to address this issue. | |

| At least 25% of resident firms use local suppliers or service providers for at least 80% of their total procurement value. | X | This indicator is naturally linked to the sectors/products of the specific park under analysis. Further, a main issue with this indicator seems to be with the data compilation by tenant firms and park management. | ||

References

- United Nations. Transforming our World: The 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development; General Assembly of United Nations: New York, NY, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- United Nations Industrial Development Organization. Eco-Industrial Parks: Achievements and Key Insights from the Global RECP Programme 2012–2018; United Nations Industrial Development Organization: Vienna, Austria, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- United Nations Industrial Development Organization; World Bank Group; Deutsche Gesellschaft für Internationale Zusammenarbeit. An International Framework for Eco-Industrial Parks, © World Bank. License: CC BY 3.0 IGO; World Bank: Washington, DC, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Côté, R.; Cohen-Rosenthal, E. Designing eco-industrial parks: A synthesis of some experience. J. Clean. Prod. 1998, 6, 181–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Chertow, M.R. The eco-industrial park model reconsidered. J. Ind. Ecol. 2008, 2, 8–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lowe, E.A.; Moran, S.R.; Holmes, D.B. Eco-Industrial Parks: A Handbook for Local Development Teams; Indigo Development: Oakland, CA, USA, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Jacobsen, N.B. Industrial symbiosis in Kalundborg, Denmark: A quantitative assessment of economic and environmental Aspects. J. Ind. Ecol. 2006, 10, 239–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valero, A.; Usón, S.; Costa, J. Exergy analysis of the industrial symbiosis model in Kalundborg. Proc. ECOS 2012, 25, 218/1–218/11. [Google Scholar]

- Valentine, S.V. Kalundborg symbiosis: Fostering progressive innovation in environmental networks. J. Clean. Prod. 2016, 118, 65–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ayres, R. Industrial metabolism: Theory and policy. In The Greening of Industrial Ecosystems; Richards, D., Allenby, B., Frosch, R., Eds.; National Academy of Science: Washington, DC, USA, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Baas, L. Cleaner production and industrial ecosystems, a Dutch experience. J. Clean. Prod. 1998, 6, 189–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taddeo, R.; Simboli, A.; Morgante, A. Implementing eco-industrial parks in existing clusters. Findings from a historical Italian chemical site. J. Clean. Prod. 2012, 33, 22–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ribeiro, P.; Fonseca, F.; Neiva, C.; Bardi, T.; Lourenço, J.M. An integrated approach towards transforming an industrial park into an eco-industrial park: The case of Salaise-Sablons. J. Environ. Plan. Manag. 2018, 61, 195–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, C.; de Jong, M.; Dijkema, G.P.J. Process analysis of eco-industrial park development. The case of Tianjin, China. J. Clean. Prod. 2014, 64, 464–477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, H.M.; Zhang, Y.; Yang, N.J. Evaluation of an eco-índustrial park based on a social network analysis. Procedia Environ. Sci. 2012, 13, 1624–1629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Chertow, M.R. Industrial symbiosis: Literature and taxonomy. Annu. Rev. Energy Environ. 2000, 25, 313–337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Geng, Y.; Zhang, P.; Côté, R.P.; Fujita, T. Assessment of the national eco-industrial park standard for promoting industrial symbiosis in China. J. Ind. Ecol. 2009, 13, 15–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fujii, M.; Fujita, T.; Dong, L.; Lu, C.; Geng, Y.; Behera, S.K.; Park, H.-S.; Chiu, A.S.F. Possibility of developing low-carbon industries through urban symbiosis in Asian cities. Post Foss. Carbon Soc. Regen. Prev. Eco-Ind. Dev. 2016, 114, 376–386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Beers, D.; Corder, G.; Bossilkov, A.; van Berkel, R. Industrial symbiosis in the Australian minerals industry–The cases of Kwinana and Gladstone. J. Ind. Ecol. 2007, 11, 55–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Van Berkel, R.; Fujita, T.; Hashimoto, S.; Fujii, M. Quantitative assessment of urban and industrial symbiosis in Kawasaki, Japan. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2009, 43, 1271–1281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- World Bank Group. Low-Carbon Zones–A Practitioner’s Handbook; World Bank Group, Investment Climate Department: Washington, DC, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Lowe, E.A. Eco-Industrial Park Handbook for Asian Developing Countries; Asian Development Bank: Manila, Philippines, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Deutsche Gesellschaft für Internationale Zusammenarbeit. Guidelines for Sustainable Industrial Areas-Version 1.0 (October); Deutsche Gesellschaft für Internationale Zusammenarbeit (GIZ) GmbH: Eschborn, Germany, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- United Nations Industrial Development Organization. Global Assessment of Eco-Industrial Parks in Developing and Emerging Countries: Achievements, Good Practices and Lessons Learned from Thirty-Three Industrial Parks in Twelve Selected Emerging and Developing Countries; United Nations Industrial Development Organization: Vienna, Austria, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- World Bank Group. Mainstreaming Eco-Industrial Parks; World Bank Group: Washington, DC, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Van Berkel, R. Regional Resource Synergies for Sustainable Development in Heavy Industrial Areas: An Overview of Opportunities and Experiences; Curtin University of Technology: Perth, Australia, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Batten, D. Converting waste into wealth: The scope for eco-industrial complexes in Australian regions. In Proceedings of the World Congress of the International Solid Waste Association (ISWA), Melbourne, Australia, 9–14 November 2003. [Google Scholar]

- United Nations Industrial Development Organization. Implementation Handbook for Eco-Industrial Parks; United Nations Industrial Development Organization: Vienna, Austria, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Fonseca, L.M.; Domingues, J.P.; Dima, A.M. Mapping the Sustainable Development Goals relationships. Sustainability 2020, 12, 3359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development. Green Growth Indicators Framework; Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development: Paris, France, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Indian Green Building Council. Green Special Economic Zone (SEZ) Rating System; Indian Green Building Council: Hyderabad, India, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Von Hauff, M.; Fischer, K. Industrial and commercial zone planning according to the requirements of sustainable development. In Sustainable Development Policy: A European Perspective; Routledge: Abingdon, UK; New York, NY, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Van Beers, D.; Flammini, A.; Meylan, F.D.; Stucki, J. Lessons Learned from the Application of the UNIDO Eco-Industrial Park Toolbox in Viet Nam and Other Countries. Sustainability 2019, 11, 4687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Deutsche Gesellschaft für Internationale Zusammenarbeit. Sustainable Industrial Area Toolbox. Available online: https://www.sia-toolbox.net/ (accessed on 22 August 2020).

- CII–Godrej GBC. Resource Efficient and Cleaner Production (RECP) Pilot Project to Foster Eco-Industrial Development in Eco-Industrial Parks in India; Confederation of Indian Industry Green Business Centre: Hyderabad, India, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- World Bank Group. Public-Private Dialogue (PPD) Stakeholder Mapping Toolkit: A Practical Guide for Stakeholder Analysis in PPD Using the Net-Map Method; World Bank Group: Washington, DC, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- United Nations Industrial Development Organization; UN Environment Programme. Enterprise-Level Indicators for Resource Productivity and Pollution Intensity: A Primer for Small and Medium-Sized Enterprises; United Nations Industrial Development Organization and United Nations Environment Programme: Vienna, Austria; Paris, France, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- United Nations Industrial Development Organization; World Bank Group; Deutsche Gesellschaft für Internationale Zusammenarbeit; Ministry of Trade, industry and Energy. Practitioner’s Handbook for Eco-Industrial Parks; World Bank: Washington, DC, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- United Nations Industrial Development Organization. Eco-Industrial Parks (EIP) Toolbox; United Nations Industrial Development Organization: Vienna, Austria, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- International Finance Corporation; MPI. National Technical Guidelines for Eco-Industrial Parks in Viet Nam; International Finance Corporation and and Ministry of Planning and Investment of Viet Nam: Hanoi, Vietnam, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Van Beers, D.; Bossilkov, A.; Lund, C. Development of large scale reuses of inorganic by-products in Australia: The case study of Kwinana, Western Australia. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2009, 53, 365–378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Industrial Parks Assessed | Basic Characteristics | EIP Scorings | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ownership | Total Area | % Land Occupied | Current Performance | Intended Performance | Improvement Potential | |

| Average 50 parks | 536 | 63% | 58% | 77% | 19% | |

| Colombia–Average | 117 ha | 65% | 58% | 77% | 19% | |

| Park 1 | Private sector | 116 ha | 65% | 62% | 76% | 13% |

| Park 2 | Private sector | 200 ha | 45% | 73% | 83% | 9% |

| Park 3 | Private sector | 64 ha | 75% | 70% | 79% | 9% |

| Park 4 | Private sector | 134 ha | 80% | 68% | 84% | 15% |

| Park 5 | Private sector | 70 ha | 60% | 65% | 76% | 11% |

| Egypt– Average | 314 | 68% | 57% | 76% | 19% | |

| Park 6 | Public sector | 332 ha | 50% | 45% | 73% | 28% |

| Park 7 | Private sector | 310 ha | 90% | 66% | 82% | 15% |

| Park 8 | Public–private partnership | 300 ha | 65% | 60% | 74% | 14% |

| Indonesia– Average | 843 | 74% | 67% | 83% | 16% | |

| Park 9 | Private sector | 1400 ha | 60% | 71% | 89% | 18% |

| Park 10 | Private sector | 1400 ha | 80% | 69% | 90% | 21% |

| Park 11 | Private sector | 3500 ha | 75% | 61% | 87% | 26% |

| Park 12 | Private sector | 350 ha | 90% | 68% | 82% | 15% |

| Park 13 | Private sector | 540 ha | 75% | 70% | 90% | 21% |

| Park 14 | Private sector | 270 ha | 60% | 76% | 91% | 15% |

| Park 15 | Public sector | 140 ha | 100% | 53% | 58% | 5% |

| Park 16 | Private sector | 442 ha | 90% | 74% | 84% | 11% |

| Park 17 | Private sector | 307 ha | 40% | 56% | 71% | 15% |

| Park 18 | Private sector | 115 ha | 50% | 59% | 78% | 18% |

| Park 19 | Private sector | 805 ha | Up to 100% | 86% | 97% | 11% |

| Nigeria– Average | 1576 | 50% | 54% | 76% | 22% | |

| Park 20 | Public sector | 152 ha | 80% | 42% | 69% | 26% |

| Park 21 | Public sector | 3000 ha | <20% | 66% | 83% | 18% |

| Peru– Average | 216 | 45% | 46% | 61% | 16% | |

| Park 22 | Private sector | 137 ha | 60% | 33% | 56% | 23% |

| Park 23 | Private sector | 526 ha | <10% | 56% | 68% | 12% |

| Park 24 | Private sector | 207 ha | <10% | 47% | 64% | 17% |

| Park 25 | Private sector | 208 ha | <10% | 59% | 76% | 16% |

| Park 26 | Private sector | 150 ha | 80% | 41% | 58% | 18% |

| Park 27 | Private sector | 66 ha | 100% | 39% | 45% | 6% |

| South Africa– Average | 538 | 52% | 55% | 80% | 25% | |

| Park 28 | Public–private partnership | 236 ha | 50% | 84% | 94% | 10% |

| Park 29 | Public sector | 250 ha | 75% | 45% | 78% | 33% |

| Park 30 | Public–private partnership | 130 ha | 30% | 72% | 84% | 12% |

| Park 31 | Public sector | 455 ha | 40% | 52% | 83% | 31% |

| Park 32 | Public sector | 222 ha | >80% | 29% | 66% | 36% |

| Park 33 | Public sector | 124 ha | 80% | 56% | 82% | 26% |

| Park 34 | Public sector | 154 ha | 50% | 39% | 73% | 34% |

| Park 35 | Public sector | 125 ha | >80% | 49% | 75% | 26% |

| Park 36 | Public sector | 300 ha | 50% | 39% | 68% | 28% |

| Park 37 | Public–private partnership | 119 ha | 21% | 66% | 94% | 28% |

| Park 38 | Public–private partnership | 3800 ha | 15% | 70% | 83% | 14% |

| Ukraine– Average | 135 | 63% | 41% | 68% | 27% | |

| Park 39 | Private sector | 270 ha | 70% | 36% | 65% | 28% |

| Park 40 | Private sector | 8.5 ha | 75% | 43% | 69% | 25% |

| Park 41 | Public–private partnership | 10 ha | 70% | 41% | 69% | 27% |

| Park 42 | Public sector | 250 ha | 35% | 43% | 72% | 28% |

| Viet Nam- Average | 638 | 78% | 63% | 79% | 16% | |

| Park 43 | Private sector | 948 ha | 50% | 70% | 81% | 12% |

| Park 44 | Private sector | 596 ha | 81% | 55% | 81% | 26% |

| Park 45 | Public sector | 351 ha | 70% | 59% | 74% | 15% |

| Park 46 | Public sector | 394 ha | 100% | 64% | 78% | 15% |

| Park 47 | Public sector | 300 ha | 95% | 54% | 77% | 24% |

| Park 48 | Private sector | 1686 ha | 45% | 67% | 76% | 10% |

| Park 49 | Public–private partnership | 488 ha | 90% | 63% | 75% | 13% |

| Park 50 | Private sector | 344 ha | 94% | 75% | 87% | 12% |

| Industrial Parks | Current Performance of Industrial Parks | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| All 51 Prerequisites and Indicators (total EIP Scoring) | Prerequisites and Indicators Largely Driven by Human Efforts and Low Investments | Prerequisites and Indicators Largely Driven by Financial Investments | |

| All 50 assessed parks | 58% | 60% | 50% |

| Performance Category Averages | |||

| Parks with higher EIP performance (EIP scoring > 70%) | 74% | 77% | 63% |

| Parks with medium EIP performance (EIP scoring between 50% and 70%) | 61% | 63% | 53% |

| Parks with lower EIP performance (EIP scoring < 50%) | 41% | 42% | 34% |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

van Beers, D.; Tyrkko, K.; Flammini, A.; Barahona, C.; Susan, C. Results and Lessons Learned from Assessing 50 Industrial Parks in Eight Countries against the International Framework for Eco-Industrial Parks. Sustainability 2020, 12, 10611. https://doi.org/10.3390/su122410611

van Beers D, Tyrkko K, Flammini A, Barahona C, Susan C. Results and Lessons Learned from Assessing 50 Industrial Parks in Eight Countries against the International Framework for Eco-Industrial Parks. Sustainability. 2020; 12(24):10611. https://doi.org/10.3390/su122410611

Chicago/Turabian Stylevan Beers, Dick, Klaus Tyrkko, Alessandro Flammini, César Barahona, and Christian Susan. 2020. "Results and Lessons Learned from Assessing 50 Industrial Parks in Eight Countries against the International Framework for Eco-Industrial Parks" Sustainability 12, no. 24: 10611. https://doi.org/10.3390/su122410611

APA Stylevan Beers, D., Tyrkko, K., Flammini, A., Barahona, C., & Susan, C. (2020). Results and Lessons Learned from Assessing 50 Industrial Parks in Eight Countries against the International Framework for Eco-Industrial Parks. Sustainability, 12(24), 10611. https://doi.org/10.3390/su122410611