Abstract

A growing number of studies suggest that flow experience is associated with life satisfaction, eudaimonic well-being, and the perceived strength of one’s social and place identity. However, little research has placed emphasis on flow and its relations with negative experiences such as anxiety. The current study investigated the relations between flow and anxiety by considering the roles of self-esteem and academic self-efficacy. The study sample included 590 Chinese university students, who were asked to complete a self-report questionnaire on flow, anxiety, self-esteem, and academic self-efficacy. Data were analyzed using structural equation modeling (SEM) with AMOS software, in which both factorial analysis and path analysis were performed. Results revealed that the experience of flow negatively predicted anxiety, and both self-esteem and academic self-efficacy fully mediated the path between flow and anxiety. Specifically, self-esteem played a crucial and complete mediating role in this relationship, while academic self-efficacy mediated the path between self-esteem and anxiety. Our findings enrich the literature on flow experience and help with identifying practical considerations for buffering anxiety and more broadly with fostering strategies for promoting psychological sustainability and resilience.

1. Introduction

What constitutes a good life? Is this signaled by adequate material wealth? Nowadays, an increasing number of people, especially the young, find themselves trapped in an anxious state even though their wallets grow plumper. A survey conducted by the Anxiety and Depression Association of America reported that seven out of ten American adults claim to experience stress or anxiety at least at a moderate level on a daily basis [1]. As a prevalent emotional disorder that interferes with psychosocial functioning [2], anxiety has also become a serious public health problem in China and among university students, having an impact on their daily life [3]. The gap between economic growth in China and anxiety reminds us to seek clues from other areas besides economics to answer questions in relation to what constitutes a good life.

Addressing this question, Csikszentmihalyi [4] conducted extensive investigations of rock climbers, chess players, athletes, artists, and those well-known in their fields about why they often perform time-consuming, difficult, and even dangerous daily activities, even though these challenges do not repay any discernable and extrinsic reward. The answer points towards the concept of flow. In general, flow describes a state in which an individual is fully involved in the activity or task at hand without a sense of time, fatigue, or awareness of other irrelevant matters. One focuses on nothing else but merely the activity itself, feeling an intense sense of inner bliss likened to a stream flowing through one’s heart: giving rise to the name flow. There are three typical characteristic features of flow that are frequently reported by people experiencing it: the merging of action and awareness, a sense of control, and an altered sense of time [4,5,6].

A good life, according to Seligman [7], is considered to be a pleasant, meaningful, and engaged life that seeks to have more flow experience. Living without anxiety disorder is one of aspects of living a good life. It is beyond dispute that more support should be given to help anxiety disorder sufferers gain a sense of control of their inner mind. At the same time, flow which is characterized by self-consciousness and concentration can demonstrate a kind of self-control. Although flow has been investigated in association with many psychological constructs such as eudaimonic well-being [8,9] and subjective well-being [10], little research has explored its relationship to anxiety and the associated underlying mechanisms. So, can flow alleviate anxiety?

Anxiety, according to Craske and Stein, has become one of the most prevalent psychiatric disorders of modern times: it refers to a set of disorders characterized by excessive fear, anxiety, or avoidance of an array of external and internal stimuli [11]. Anxiety has been experienced by a growing proportion of university students in recent years. Beiter and colleagues investigated what types of college students tend to experience the most serious anxiety symptoms and found that transfers, upperclassmen, and those living off-campus are the most anxious groups, experiencing anxiety in confronting three major concerns: academic performance, pressure to succeed, and post-graduation plans [1]. While academic study can be perceived as a positive challenge for university students, potentially increasing learning capacity and competency, such stress can be detrimental to student mental health if viewed negatively [12,13].

We therefore proposed the present study as a novel trial with a unique perspective, hypothesizing flow (optimal experience) as a potentially important way to reduce anxiety and therefore promote happiness. Moreover, we sought to provide preliminary empirical support for flow–anxiety relations by exploring the underlying mechanisms taking into consideration some possible influencing factors such as academic self-efficacy and self-esteem.

2. Theoretical Background and Hypotheses

2.1. Flow and Anxiety

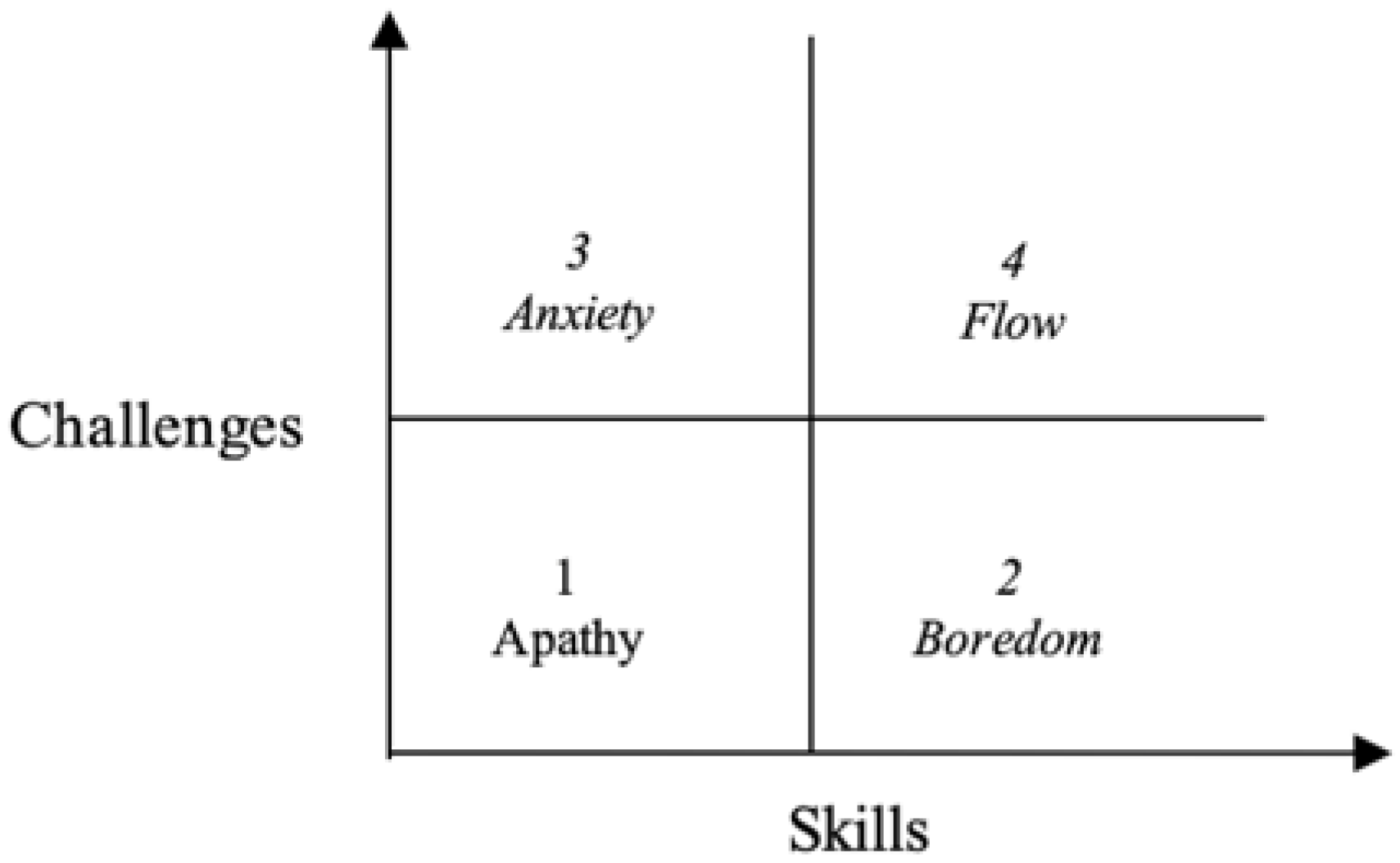

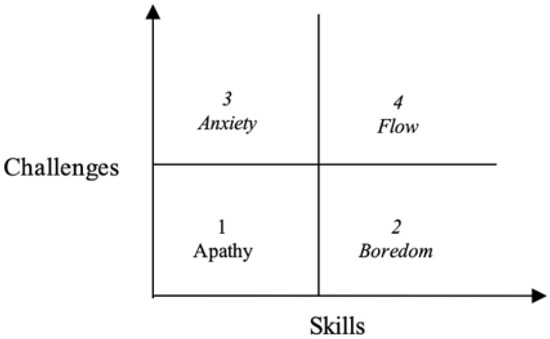

Flow theory proposes that the main mechanism for experiencing flow is that the perceived challenges of the task at hand and the skills one possesses to cope with these challenges are both relatively high and in balance [6]. Characteristics of flow include the following nine aspects: (a) clear goals; (b) immediate and unambiguous feedback; (c) a balance of skills versus challenges; (d) sense of control over the task at hand; (e) high but subjectively effortless attention; (f) distorted sense of time perception, with time moving faster or slower than usual; (g) a merging of awareness and action; (h) a loss of self-awareness; and (i) an ‘autotelic’ experience namely that engaging in the task itself is perceived as rewarding. Since the combinations of high-challenge and high-skill situations are mostly found in work and structured leisure activities in daily life, flow is more frequently and intensely perceived in these situations [14,15,16]. On the contrary, any other combination may result in other psychological states (Figure 1): for instance, (a) apathy, combinations of low challenges and low skills; (b) relaxation, resulting from high skills but low challenges; (c) anxiety, combined high challenges with low skills. In particular, the frequency and intensity of flow in everyday life pinpoint the extent to which a person achieves sustained happiness through deliberate striving and ultimately fulfills his or her growth potential [16,17].

Figure 1.

The flow quadrant model.

Flow theory postulates that an individual who has intense and frequent flow will experience more elements of autotelic personality, which is driven by teleonomy of the self: for instance, if one’s skills are perceived to be incapable of the challenges in a given task, s/he would experience anxiety, and then s/he will try to acquire new skills to retain balance in order to cope with the task [18,19]. Such an autotelic personality enables an individual to have a pattern of flow experience which is an essential driving force for the successful unfolding of personal potential, as well as for healthy human development [16,20].

People engaging in flow often report several typical features, such as the merging of action and awareness, a sense of control, and an altered sense of time [4]. However, people engaging in anxiety often feel a loss of control; Collins and colleagues found that higher flow was positively associated with higher arousal of positive affect (i.e., feeling fired-up, enthusiastic) and life satisfaction, while negatively associated with lower arousal of negative affect (i.e., feeling sad and disappointed) [21]. As many studies on flow were focused on its positive effect in young people [14,22], studies on the relation of flow to negative experiences such as anxiety are scarce in the existing literature. As such, we propose the following main hypothesis:

H1.

Flow is negatively associated with anxiety. The more the flow experience, the less the anxiety experience, with flow negatively predicting anxiety.

2.2. Flow and Self-Esteem

Self-esteem refers to one’s positive or negative attitude toward oneself and is an individual’s self-assessment of his or her own worth [23]. Self-esteem is consistently related to, and important for, one’s psychological well-being, as high self-esteem is associated with greater well-being than low self-esteem [24]. Research has found that people with higher self-esteem reported more positive mood (and less negative mood) than those with lower self-esteem [25]. Moreover, researchers also found that self-esteem is important for objective physical health [26].

In examining the relationship between a person’s self-esteem and flow experience, some previous work has shown that self-esteem has worked as an antecedent for flow experience. For instance, when playing a digital game, greater self-esteem was able to enhance the level of flow experiences [27]. It has also been shown that lower self-esteem would enable higher flow experience in relation to the use of the Internet, video games, and mobile phones [28], with it being argued that individuals who exhibit lower self-esteem, in comparison to those with higher self-esteem, are more likely to engage in excessive media-related antisocial activities in order to avoid negative feedback from others or uncomfortable situations. Conversely, a body of research has also demonstrated that self-esteem could be a consequence of flow. As an antecedent, flow has significant potential for fostering the development of important aspects of personality [29,30]. For instance, in a study with Japanese college students, those who experienced flow more frequently in their daily life were reported to be more likely to have higher self-esteem [31]. Due to these contradictory findings on flow and self-esteem relations, in the present research we propose that the higher the level of flow, the stronger the level of self-esteem in university students will be:

H2.

Flow is positively associated with self-esteem, with flow predicting stronger self-esteem.

2.3. Flow and Academic Self-Efficacy

As flow will be experienced during an activity when a person’s skill capability meets the external social environmental challenges [32], the behaviors performed in the activity are regulated and motivated by an integration of both external social environmental and internal self-influential factors based on social cognitive theory [33]. Self-efficacy, as one of the most essential self-influential factors, refers to how a person accesses and regards his or her capability to organize courses of action for completing the required and/or targeted activities [34]. On this basis, academic self-efficacy is defined as one’s judgement about his or her abilities to successfully achieve the given academic goals [35]. Academic self-efficacy has long been viewed as an important determinant of academic performance and personal development within the context of higher education [36,37]. A variety of studies have also suggested that academic self-efficacy is positively associated with flow [38,39]. For instance, flow was more likely to occur when students were in control of their academic situation and were fully immersed in the activities at hand; it occurred more extensively when there was stronger perceptions of a distorted sense of time [40].

From a theoretical perspective, the higher the level of one’s flow (optimal experience), the more likely one is to establish a series of clear goals, to gain solid control of the task at hand, and to feel an intense sense of immersion and euphoria [4]. As an important component of flow, autonomy, or an individual’s freedom in scheduling their activities, has repeatedly been found to increase positive affect [41] and motivation [42], which will then promote self-efficacy. While academic self-efficacy is reflected in every aspect of the daily activities of university students, an individual who has flow experience may feel increased confidence and a loss of self-awareness regarding academic study [5]. In this sense, we predict that:

H3.

Individuals who have experienced more flow will have stronger academic self-efficacy, with flow positively predicting academic self-efficacy.

2.4. Self-Esteem with Academic Self-Efficacy and Anxiety

From reviewing the theoretical background, self-esteem was recognized as a more general and broader concept than self-efficacy, which has been put forth as the notion of having a global and stable sense of one’s worth, that is, an attitude or feeling about oneself [43]. Self-esteem is a type of belief that involves judgments of self-worth. It differs from self-efficacy because it is an affective reaction indicating how a person feels about him- or herself, whereas self-efficacy involves cognitive judgments of personal capacity [44].

Individuals who have a low level of self-efficacy are more likely to hold negative and pessimistic opinions about their inner self and external environment. Conversely, a strong sense of self-efficacy is a breeding ground for cultivating positive feelings, thus helping individuals to better cope with the challenges they face and to seize vital opportunities for turning points of life [45]. In this sense, we hold the opinion that self-efficacy can predict people’s self-esteem.

Research has also shown that people with high self-esteem experience less anxiety. Iancu, Bodner, and Ben-Zion considered self-esteem, self-criticism, dependency, and self-efficacy as potential features of social anxiety and examined their relations. Results revealed that social anxiety disorders were negatively associated with self-esteem and self-efficacy and positively associated with self-criticism and dependency [46]. People with higher self-esteem were much more able to recover from illness and reported greater physical health than those with lower self-esteem [26], as they were more likely to engage in activities that promote physical health and, furthermore, to form habits that tend to underpin good health. They were more resilient to anxiety, capable of dealing with stress, and more likely to have a better quality of interpersonal relationships that foster more optimal physical functioning [23].

Furthermore, a large number of studies have focused on the mediating role of self-esteem. These have investigated causalities between constructs by regarding self-esteem as a mediating variable. Constructs have included body satisfaction and disordered eating behavior [47], dispositional gratitude and well-being [48], maltreatment with emotional problems and psychological maltreatment with behavioral problems [49], mindfulness and depression [50], and so forth. Here, we propose self-esteem as the mediator between academic self-efficacy and anxiety, forming the following hypothesis:

H4.

Self-esteem will mediate the path between academic self-efficacy and anxiety.

2.5. The Role of Self-Esteem and Academic Self-Efficacy in Flow–Anxiety Relations

Based on the flow state quadrant model, anxiety develops if challenges surpass an individual’s skills [14]. In contrast to anxiety, when performing an activity that involves both challenges and requisite skills, and when both challenges and skills are high and in balance, an individual is not only enjoying the moment, but is also stretching his/her capabilities with the likelihood of learning new skills and increasing self-esteem and personal complexity. Through this process, flow will be generated by elevated capability and self-esteem, and anxiety will be eliminated.

In addition, according to broaden-and-build theory [51], a subset of positive emotions (i.e., joy, interest, contentment, and love) have different functions. For instance, joy sparks the urge to play and interest sparks the urge to explore, which in turn build the individual's personal resources; these may range from physical and intellectual resources to social and psychological resources. Importantly, these resources function as reserves that can be drawn upon later to assist in coping with negative situations and emotions [51]. From this point of view, the impact of flow on anxiety may function through this broaden-and-build process. Individual self-efficacy, which is rebuilt in this process and then improves self-esteem, may act as a personal resource to alleviate anxiety. Thus, the following hypotheses were proposed:

H5.

Flow will elevate self-esteem through promoting academic self-efficacy.

H6.

Flow will alleviate anxiety through promoting academic self-efficacy and then self-esteem.

2.6. Research Design and Proposed Model

The present study is a novel trial with a unique perspective which aims to confirm optimal experiences as a potentially valid approach to reduce anxiety and to test if a restoration of self-esteem can return a more accurate perception of the balance between challenges and skills, therefore decreasing the level of anxiety. This study also aims to provide preliminary empirical support for future studies on clinical practice [52]. In this research, we will set gender and debt condition as moderating variables in order to test whether a statistically significant difference exists among the different models for different gender or debt group conditions.

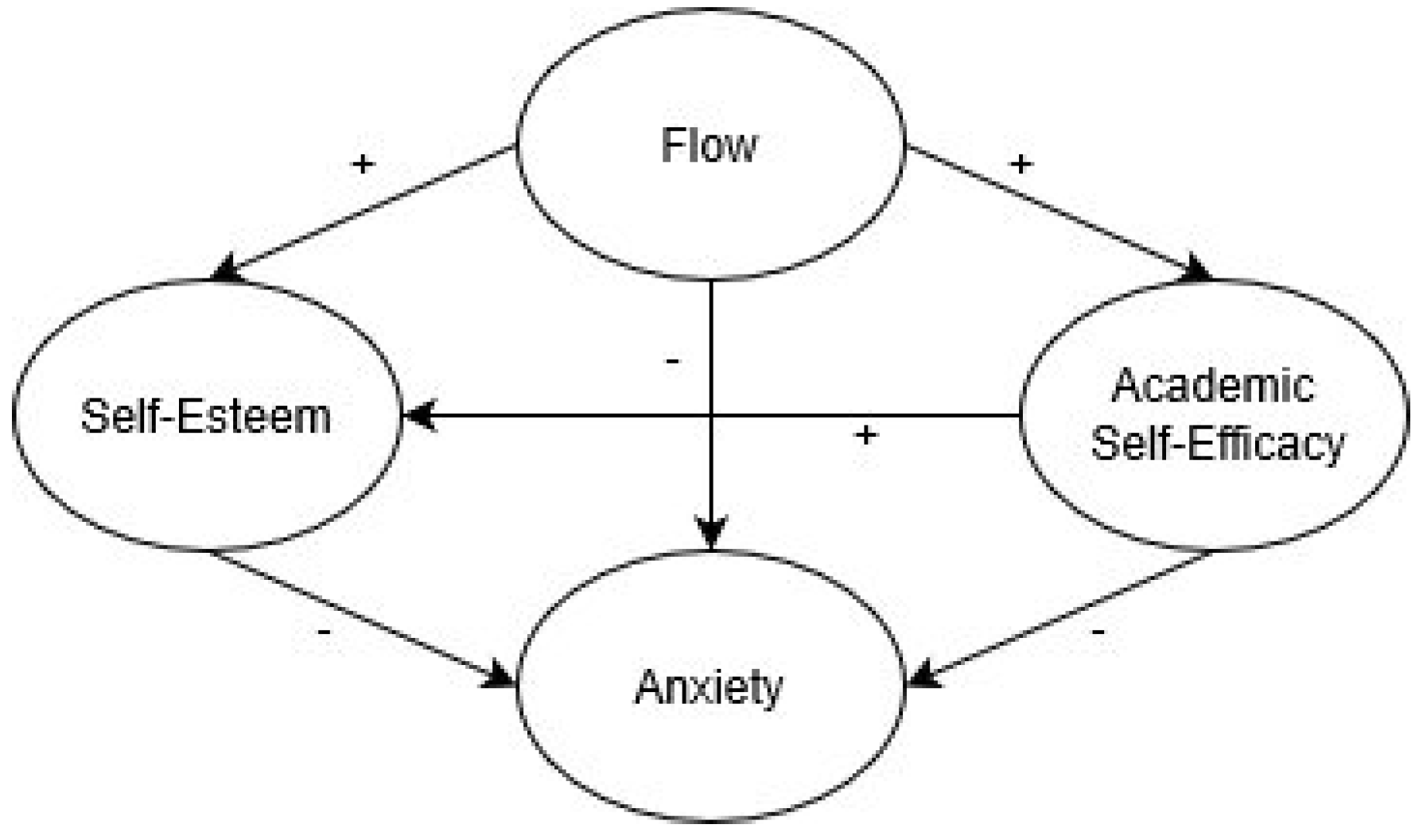

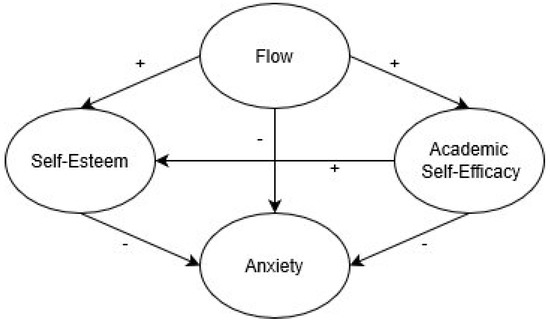

To verify the hypotheses above (Figure 2), we conducted a set of data analyses. First, factorial analysis and path analysis were performed in AMOS (21.0 version, IBM, USA) to test factorial validity and causal types of relationships. Second, structural equation modeling (SEM) was conducted to empirically confirm predicting and mediating effects among flow, self-esteem, academic self-efficacy, and anxiety. Thus, four constructs, as latent variables, were combined in the model, and each of them was indicated by several of the observed variables, which accordingly corresponded to certain items in the administered questionnaires. Based on the confirmed statistical model, the causal intensity of different dimensions of flow on anxiety was calculated to provide detailed support for psychological interventions. Thus, we were able to suggest differential allocation of attention to practice that is aimed at strengthening individuals’ optimal experiences in light of these intensity values.

Figure 2.

Proposed structural model.

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Participants and Procedures

A total of 630 participants who were registered at Southwest Jiaotong University were contacted, of which 627 responded. Excluding those individuals who finished the questionnaire in an unreasonably short time and for whom there were missing data on crucial study variables, a final sample of 590 participants remained. Of the participants, 46.78% were women and 53.22% were men, and they were aged between 18 and 25 years (M = 20, SD = 1.6). Of those in the sample, 23.05% were freshmen, 25.08% were sophomores, 28.64% were juniors, 13.90% were seniors, and 9.32% were postgraduates. For the majority of respondents (77.3%), their monthly disposable incomes were within the range between 1000 and 2000 RMB (about 130 and 260 Euro). Over one-third (36.95%) of respondents reported being in an indebted condition.

Prior to data collection, the required application forms to seek ethical approval for the research were prepared and submitted, and the project was approved at Southwest Jiaotong University by routine exemption, due to proper survey design, anonymity, and lack of harm to participants. The study followed by ethical principles based on guidelines from international scientific communities in psychology. Informed consent for participation was obtained after participants were presented with documents that outlined any risks, their choice to participate, and their ability to leave. Participants then proceeded to complete the survey. A total of 630 paper and pencil-based questionnaires were printed and then administered in the library and classrooms inside the university campus. Respondents received a small gift for completing the questionnaire survey. The data-gathering phase ran from 28 to 29 April in the year 2019.

3.2. Measures

Standard and specific instruments were used to measure flow, anxiety, self-esteem, and academic self-efficacy, based on the past month of an individual’s psychological state. The instruments were delivered by means of a self-report questionnaire consisting of three sections. The first section included 42 multiple-choice questionnaire items. The majority of the items were positively worded, while the five negatively worded items were reversely coded. Responses to all of the multiple-choice questions were registered on a 7-point Likert-type scale with answers ranging from 1 (“not at all characteristic of me”) to 7 (“completely characteristic of me”). The second section regarded participants’ financial status. The third section was on sociodemographic background.

3.2.1. Flow

By adapting a similar administration technique to that of Waterman [53] and our previous work [32], a question was developed to define the activities within which the subject subsequently had to provide responses regarding flow experience: “Think about one of your past month’s activities that was challenging but that you regularly engaged in with utmost of enjoyment (i.e., reading, sports, listening to music, etc.), please indicate your feelings based on the following eight statements____”. Then, the selected eight-item flow scale, corresponding to flow characteristics identified by Csikszentmihalyi was administered [5,6]. These items were phrased as completions of a common stem anchored by not at all characteristic of me and completely characteristic of me, with moderately in the middle. The common stem was: “When I engage in this activity ____”, and the item completions were the following: (1) I feel I have clear goals; (2) I feel self-conscious (reverse scored), (3) I feel in control; (4) I lose track of time; (5) I feel I know how well I am doing; (6) I have a high level of concentration; (7) I forget personal problems; and (8) I feel fully involved. This scale has been widely used [54,55,56,57], and its structure was tested with a reported alpha coefficient ranging from 0.80 to 0.83 in a multinational sample testing the associations between flow and personal identity [32]. Cronbach’s α for flow in the present sample was 0.798.

3.2.2. Anxiety

Participants were asked to rate their overall psychophysiological state based on the past month using the anxiety part of the DASS 21 (Depression, Anxiety, and Stress Scale 21) [58]. The scale contains nine items to access physical symptoms and mental state in relation to anxiety disorders. Mental state measurements are constituted of apprehension, panic, and worry about academic performance (i.e., “I felt apprehensive during this month”), while physical indicators included trembling, a shaky condition, dryness of the mouth, breathing difficulties, heart pounding, and palm sweatiness (i.e., “I felt sweatiness of the palms during this month”). The item which is described as “I am aware of dryness of the mouth” was eliminated after the pilot test, as it partially overlaps the item assessing sweatiness of the palms. Cronbach’s α for this scale for the present sample was 0.807.

3.2.3. Self-Esteem

Self-esteem was measured based on the renowned Rosenberg Self-Esteem Scale (RSES) [43]. With feedback from the pilot test, moderate elimination of items was performed to optimize our proposed model. The item described as “I take a positive attitude toward myself” was removed, as it overlapped another item (“on the whole, I am satisfied with myself”) in pilot test. Another item, “I certainly feel useless at times”, was also excluded, due to its similarity to “I wish I could have more respect for myself” in our pilot test. Furthermore, we discarded the item “I wish I could have more respect for myself”, because it is difficult to reverse modify this while retaining understanding in a specific Chinese context. The remaining original items, which were reverse rated, were adjusted to adapt to our model. Cronbach α for this scale in the current study was 0.899.

3.2.4. Academic Self-Efficacy

The Academic Self-Efficacy Scale from Stagg [59] was utilized to measure university students’ self-reported capability of academic performance. The scale includes eight items with three principal facets: learning efficiency, examination, and learning processes. Learning efficiency was assessed by finishing work on time to a good standard and effective management of one’s time. The examination facet was composed of passing an exam after revising hard and achieving expected grades. Other items including comprehending academic literature, effectively seeking background materials, taking notes in lectures, and answering questions in class, all of which can be regarded as specific aspects of learning processes. Cronbach’s α for academic self-efficacy in the present sample was 0.837.

3.3. Data Analysis

Data were analyzed using structural equation modeling (SEM) with AMOS 21.0 software, in which both factorial analysis and path analysis were performed. At first, assessment of normality was conducted following the estimation methods of maximum likelihood (ML), generalized least squares (GLS), and asymptotic distribution-free (ADF), which could lead us to a picture that is closer to reality [60]. Following this, the general goodness-of-fit and internal quality of the model were examined. On the basis of a model with excellent indices of goodness-of-fit, tests of mediating effects and the magnitude of indirect effects were conducted by bootstrapping procedures [61], and multigroup analyses were performed.

4. Results

4.1. Assessment of Normality

Results for the assessment of normality are given first, since the ML and GLS estimation methods are grounded on this. The maximum of absolute value of skewness was 1.131, while that of kurtosis was 1.430. So, we deemed that distribution of samples was within an acceptable range, and ML and GLS could be used to conduct the following analysis.

4.2. Convergent Validity

Due to the fact that validity is composed of convergent validity and discriminant validity, we chose composite reliability (CR) and average variance extracted (AVE) to examine convergent validity, and we performed six multimodel analyses to check discriminant validity. Test results for convergent validity are shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

Test of convergent validity.

The model was deemed to have good convergent validity when observed variables of one construct were highly correlated and when they effectively indicated the corresponding latent variable. Composite reliability (CR) assessed the consistency of indicators of each latent construct, and average variance extracted (AVE) assessed the level of error variance which latent constructs could account for. As shown in Table 1, values of CR were all above 0.6, and those of AVE were greater than 0.5, which suggested that the adjusted model of the current dataset had excellent convergent validity.

4.3. Discriminant Validity

Discriminant validity refers to when there are significant differences between the measurements of the constructs. We carried out six multimodel analyses to confirm the discriminant validity of the adjusted model. Results of multimodel analyses are shown in Table 2. It appeared that all values of chi-squared given by the three estimation methods were statistically significant, which suggested that there were substantial differences between the latent constructs, i.e., that the constructs in the adjusted model had acceptable discriminant validity.

Table 2.

Test of discriminant validity.

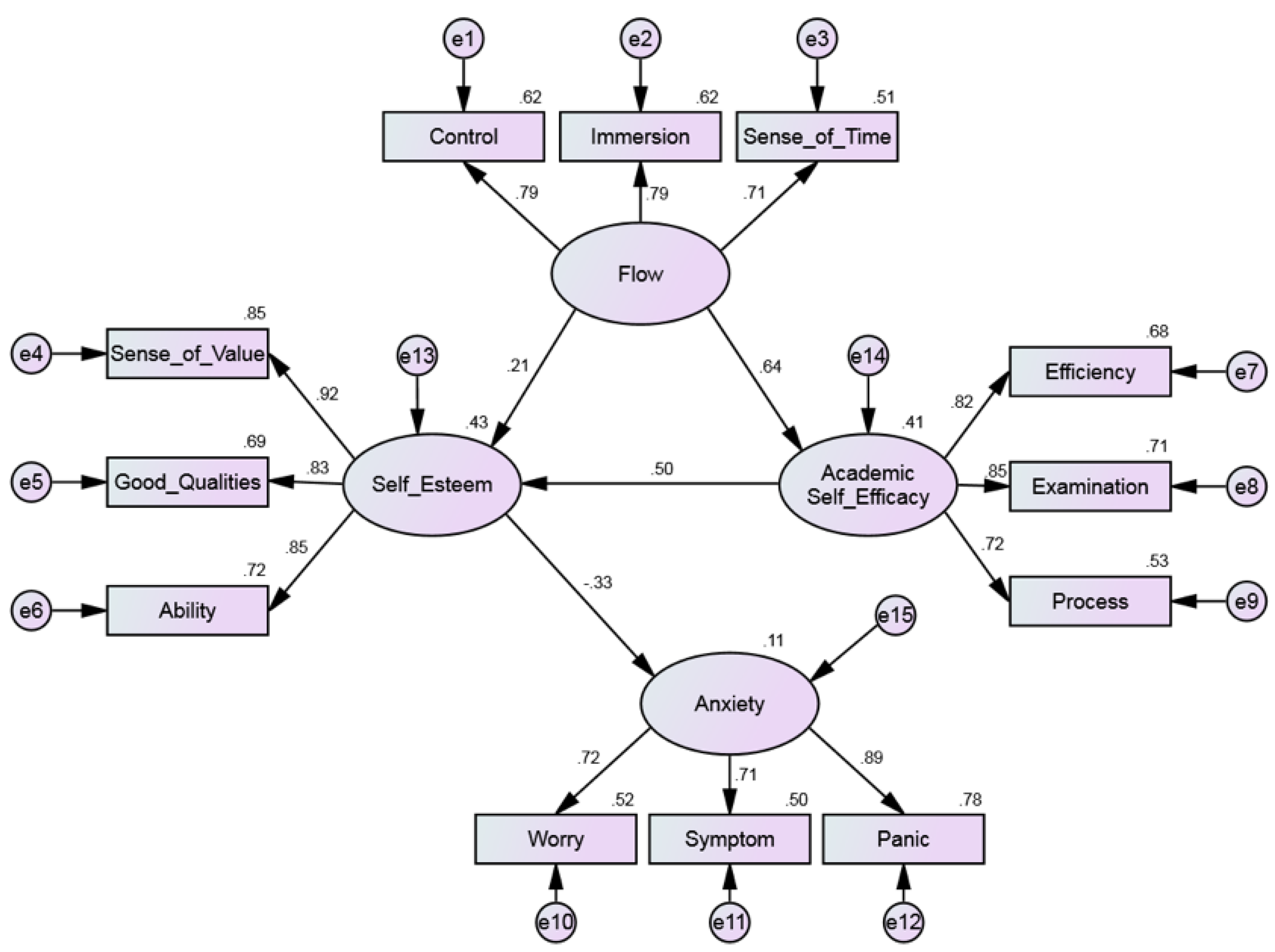

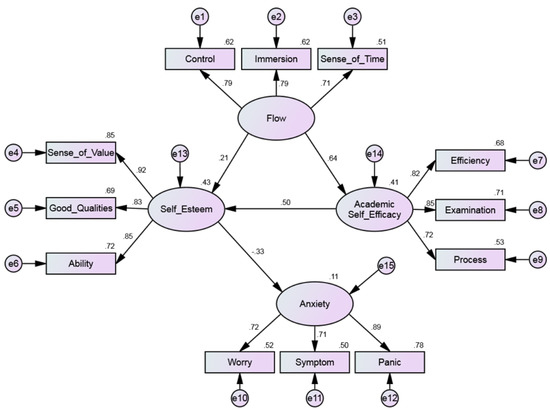

4.4. Estimated Structural Equation Model

The complete structural equation model estimated by ML is shown in Figure 3. The causal path of flow on anxiety and that of academic self-efficacy on anxiety were eliminated, for they were shown to have no statistical significance (α = 0.01). As will be discussed subsequently, the general goodness-of-fit and other internal quality indices of the current model were confirmed to be acceptable. Therefore, we continued to perform tests of mediation and multigroup analyses based on the diagram presented in Figure 3.

Figure 3.

Adjusted structural equation model estimated by maximum likelihood estimation method. Ellipses and rectangles represent constructs and observed variables, respectively. Small circles adjacent to ellipses and rectangles denote residuals and error. The values alongside the arrows represent regression weights, and those above rectangles represent reliability coefficients. The values beside ellipses represent squared multiple correlations, which are similar to r-squared values in multivariate linear regression.

Table 3 displays standardized estimates, with results of three estimation methods presented. The first part shows regression weights of the structural model, which indicates regression weights between latent variables. The latter three sections show regression weights of the measurement model, which refers to the factor loadings of each construct upon their observed variables.

Table 3.

Standardized regression weights.

From this table, we can identify that, except for certain items such as the path between flow and self-esteem, all of the other estimates by ML, GLS, and ADF appeared to be close to each other. This indicates that the samples for the current study are representative and that parameter estimates have robustness, to some degree. All the estimates had excellent statistical significance. Flow positively predicted self-esteem and academic self-efficacy. Academic self-efficacy exerted a positive influence on self-esteem, while self-esteem negatively influenced anxiety. These results confirmed our previously stated hypotheses.

Table 4 shows values for overall fit indices as estimated by ML, GLS, and ADF. Results reveal that the model had favorable overall fit.

Table 4.

Test of the overall goodness-of-fit.

4.5. Mediating Effects and Total Effects

Despite the fact that all causal paths of the model in Figure 2 were confirmed to be statistically significant, further tests of mediating effects and total effects were essential in order to identify the effects that flow and other psychological constructs exerted on anxiety. Bootstrapping SEM in AMOS 21.0 was utilized to calculate the relevant p values.

Results based on standardized estimates of indirect effects and total effects by ML, GLS, and ADF are shown in Table 5. It is clear that all indirect and total effects are significant, with p values less than 0.01. Table 5 reports three mediating-effect tests and three total-effect tests. In one respect, self-esteem played a mediating role on the path between flow and anxiety, while academic self-efficacy mediated the path between flow and self-esteem. Self-esteem mediated the path between self-efficacy and anxiety. It can be concluded that self-esteem played a fully mediating role in two related causalities, while academic self-efficacy played a partial mediating role on the path between flow and self-esteem. These results confirmed our hypotheses H2, H5, and H6. From this table we also note that of all the effects for anxiety, self-esteem had the strongest total effect, followed by flow (optimal experience), while academic self-efficacy was the weakest predictor for anxiety.

Table 5.

Tests of mediating effects and total effects (bootstrapping).

4.6. Multigroup Analysis

To confirm cross-validation of adjusted model, multigroup analyses were performed, with gender and debt condition set as moderating variables. Each of them has two possible values. Multigroup analysis in AMOS was to compare whether statistically significant difference exists between the models of different groups. Put another way, cross-validation was confirmed if the models of different gender or debt groups classified by moderating variable fit each other well.

Results of multigroup analyses are exhibited in Table 6. Due to a relatively small sample size, the index chi-squared/df can be regarded as credible and reliable to some extent. Values of RMSEA and GFI were extraordinarily prominent, which indicated remarkable fit. Hence, it was apparent that the models of different groups moderated by gender had no significant difference. The same result was also seen for models moderated by debt condition.

Table 6.

Results of multigroup analyses.

4.7. Summary of Results

As previously outlined in the introduction section, our main aim was to identify the role of optimal experience in reducing anxiety of university students. Results revealed by the present dataset may suggest interventions through enhancing flow as a potentially effective way to relieve anxiety. Firstly, the predicting effects of flow on anxiety, as well as the mediation effect of self-esteem and academic self-efficacy on the path of flow to anxiety, were tested and confirmed. Secondly, the significance of the mediating effects and total effects were obtained by bootstrapping methods based on the confirmed statistical model. Thirdly, factor loadings of observed variables on flow, self-esteem, and academic self-efficacy were shown to weight the predicting effects of different dimensions on anxiety. Overall, the results for the tested hypotheses are indicated in Table 7.

Table 7.

Test results of hypotheses.

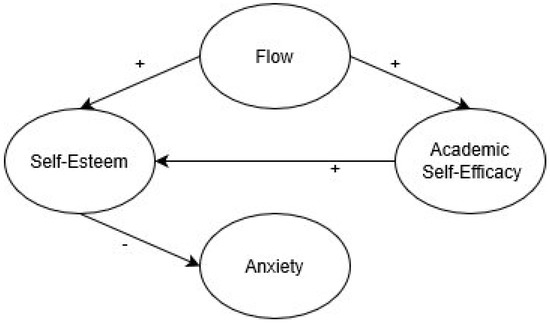

It was found that flow affected anxiety by the fully mediating function of self-esteem and academic self-efficacy. Of all the direct effects on anxiety, only self-esteem on anxiety was shown to be statistically significant, which indicated that self-esteem may play a crucial mediating role on the path of flow to anxiety.

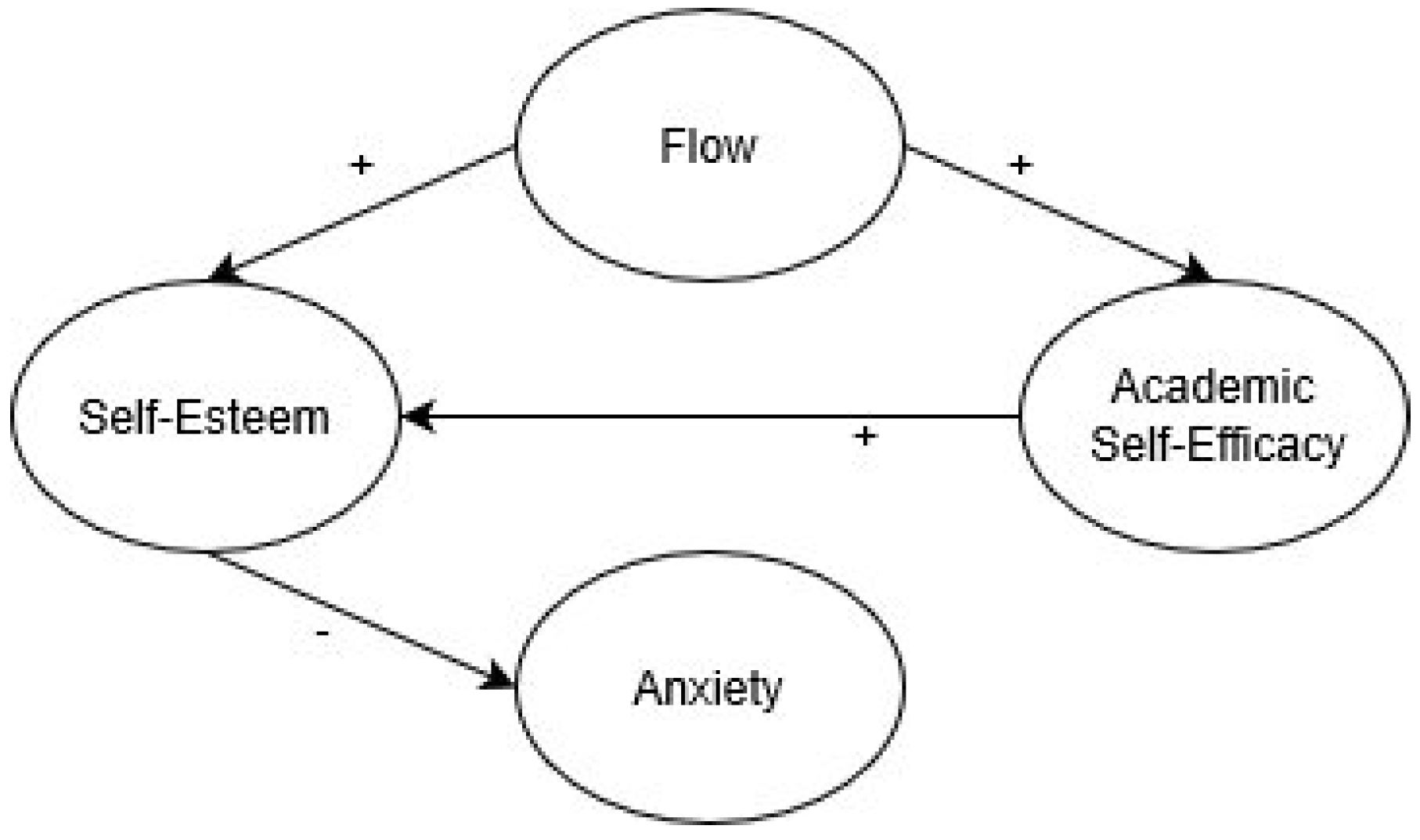

Accordingly, the proposed structural model in Figure 2 was slightly modified. The diagram of the adjusted structural model is displayed in Figure 3 and Figure 4, where the direct effects of flow and academic self-efficacy on anxiety have been eliminated.

Figure 4.

Adjusted structural model.

5. Discussion and Conclusions

The current study set out to examine the relationship between flow and anxiety and the roles of self-esteem and academic self-efficacy in the path between flow and anxiety. By using absolute instruments we found that the experience of flow negatively predicted anxiety among university students, which confirmed the previous results on negative flow–anxiety correlations [62] while providing concrete support for the notion of flow serving as a protective factor for those who experience anxiety; such a finding is also consistent with previous work on antithetical flow–anxiety relations in Midwest American University students [40]. The three loaded factors from the present investigation’s sample confirm Csikszentmihalyi’s [63] theory that flow is experienced based on typical characteristics such as control, concentration, and time distortion. Such a finding is also consistent with our prior work on flow [15,32]. Multiple studies have implied that flow experience is positively associated with positive affect and negatively linked to negative affect, and our results yielded from the present dataset also confirmed this finding. As anxiety may be considered to be a case of negative affect [40], the present work, as a novel trial, provides concrete evidence and practical suggestions for facilitating university students’ flow experience in order to alleviate their academic anxiety. However, these results may be generalizable for a broad range of professionals who are always faced with high expectations and have high potential for achievement: e.g., performing artists, professional sportsmen and dancers, commanding officers, leaders and managers.

Our research also provides strong evidence on the relationship between flow and two important self-concepts: self-efficacy and self-esteem. Our research supports previous findings and extends them with a university student sample. It should also be remembered that some previous research contributions have already shown correlations among carrying out self-defining activities, the experience of flow, and the strengthening of one’s own identity by considering personal [15], social [32], and place [19] identity. Thus, the present study reports results which coherently fit within the existing literature showing flow’s importance for the psychological self.

Secondly, the mediation effects among these latent variables were verified, and the probable mechanism for how flow experience eliminates anxiety was revealed based on the present dataset. (1) The mediating role of self-esteem on academic self-efficacy and anxiety was confirmed. As we suggested, self-esteem featured as a mediator in different functioning processes [64,65]. As with previous studies, the current study verified this mediation effect. However, in contrast to our proposition, results revealed that a full mediation effect exists between these three variables. In other words, higher academic self-efficacy will help students eliminate anxiety, entirely by promoting their self-esteem. (2) The most important finding of this study is that flow can alleviate anxiety through promoting academic self-efficacy and then self-esteem, and self-esteem has a direct influence on anxiety. This interesting finding highlights the importance of self-esteem in the relationship between flow, academic self-efficacy, and anxiety. The effect of academic self-efficacy on anxiety was fully mediated by self-esteem: this means that when university students are engaged in a flow state, their increased academic confidence and beliefs can reduce anxiety through the subsequently promoted self-evaluation of their inner worth.

The study also offers implications for educational practice. As we know, flow experience and anxiety affect occur with different levels of challenges and skills: instructors should help students in balancing academic challenges with their skills. Specifically, the important role of flow in anxiety provides strong support for the use of flow-promoting technology such as polling devices [66] to eliminate anxiety and enhance learning experiences. Secondly, as we have shown that academic self-efficacy and self-esteem play essential roles in the process of how flow influences anxiety, instructors should enable students to perceive their self-efficacy, especially enhancing their self-esteem using a variety of approaches. In this way, facilitating flow (i.e., via setting appropriate and clear learning goals, providing prompt feedback on learning process, assigning the challenging task that can be overcome with a stretch of capabilities) may foster the individual’s high performance, high achievement and competence [67], promote academic self-efficacy and self-esteem, and thus reduce anxiety.

In conclusion, the innovative contribution of this study is that we introduced flow theory to study anxiety, taking self-esteem and academic self-efficacy into consideration as mediating variables, and have proposed, tested, and confirmed a model that highlights the potential benefits of flow theory for effectively informing psychological therapies for anxiety relief in university students. This may support subsequent studies which aim to examine how and to what extent optimal experience may work to reduce anxiety amongst university students in clinical practice. However, the genuine predicting effect of flow on anxiety needs to be further verified in these efforts: the present contribution in fact provides correlation evidence, and experimental evidence is needed to prove cause–effect relations. The topics or areas of the flow-inducing activity need to be clarified: specifically, to see if any relation exists among the domain of the flow-generating activity, the domains of both self-efficacy and self-esteem, and finally the anxiety domain. Further studies need to clarify if these mediation effects happen across domains or if they are domain-constrained.

There are several limitations that warrant discussion. Firstly, the model is an approximation of the reality, and there are a number of other possible important variables which may play a role. The results remind us that there may be certain other crucial exogenous variables which need to be taken into account and which might improve the performance of the model. It seems that mere psychological constructs are not enough. This does not challenge our finding that optimal experience may be a potential way to reduce anxiety, but it does require us to reconsider this issue and the research framework with the extension of more factors. Our results implied that anxiety is an extremely sophisticated phenomenon. Despite psychological therapies which may be effective to some extent, factors from other disciplines such as economics and sociology should be integrated together in a proposed model to gain deeper insights into mechanisms for anxiety reduction. Finally, experimental evidence will be welcome in the future in order to ascertain the relations among flow, self-efficacy, and self-esteem, to finally target anxiety reduction.

A final note may stress how the elucidation of such psychological processes may help in designing strategies to build psychological sustainability, within or without clinical population and context. As anxiety is a common human experience, over and above its clinical relevance, more and more strategies and techniques are requested to manage it and to cope with it. Flow theory represents an option which can be implemented in terms of everyday ordinary activities, with very simple and clear ways of knowing how. Creating simple and available strategies for improving human psychological sustainability of commonly and optimally experienced activities and contexts (such as academic study) therefore represents a way to foster human resilience in the face of challenging, demanding, and stressing requests.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Y.M., M.B. and R.Y.; methodology, Y.M.,R.Y. and J.M.; software, R.Y.; validation, Y.M. and R.Y.; formal analysis, Y.M. and R.Y.; investigation, L.H.; resources, Y.M. and M.B.; data curation, Y.M.; writing—original draft preparation, R.Y. and Y.M.; writing—review and editing, Y.M., R.Y., J.M., M.B. and L.H.; visualization, J.M.; supervision, M.B. and L.H.; project administration, Y.M. and R.Y.; funding acquisition, Y.M. and R.Y. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by National Natural Science Foundation of China (NSFC, 71801180, 71871201) and Planning and Commissioned Project of Social Sciences of Sichuan Provincial Education Department (2019S310057).

Acknowledgments

Authors wish to acknowledge the collaboration of Wang Junxiang on data collection.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest. The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript, or in the decision to publish the results

References

- Beiter, R.; Nash, R.; McCrady, M.; Rhoades, D.; Linscomb, M.; Clarahan, M.; Sammut, S. The prevalence and correlates of depression, anxiety, and stress in a sample of college students. J. Affect. Disord. 2015, 173, 90–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Balestrieri, M.; Isola, M.; Quartaroli, M.; Roncolato, M.; Bellantuono, C. Assessing mixed anxiety-depressive disorder a national primary care survey. Psychiatr. Res. 2010, 176, 197–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pang, Z.; Tu, D.; Cai, Y. Psychometric Properties of the SAS, BAI, and S-AI in Chinese University Students. Front. Psychol. 2019, 10, 93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Csikszentmihalyi, M. Flow and the Foundations of Positive Psychology: The Collected Works of Mihaly Csikszentmihalyi; Springer: Berlin, Germany, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Csikszentmihalyi, M. The Flow Experience and its Significance for Human Psychology. In Optimal Experience: Psychological Studies of Flow in Consciousness; Csikszentmihalyi, M., Ed.; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 1988. [Google Scholar]

- Csikszentmihalyi, M. Flow: The Psychology of Optimal Experience; Harper & Row: New York, NY, USA, 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Seligman, M.E.P.; Parks, A.C.; Steen, T. A Balanced Psychology and a Full Life. Philos. Trans. Royal Soc. B Biol. Sci. 2004, 359, 1379–1381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bassi, M.; Steca, P.; Monzani, D.; Greco, A.; Delle Fave, A. Personality and Optimal Experience in Adolescence: Implications for Well-Being and Development. J. Happiness Stud. 2014, 15, 829–843. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, L.H.; Ye, Y.C.; Chen, M.Y.; Tung, I.W. Alegria! Flow in Leisure and Life Satisfaction: The Mediating Role of Event Satisfaction Using Data from an Acrobatics Show. Soc. Indic. Res. 2010, 99, 301–313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fullagar, C.J.; Kelloway, E.K. 'Flow' at work: An experience sampling approach. J. Occup. Organ. Psychol. 2009, 82, 595–615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Craske, M.G.; Stein, M.B. Anxiety. Lancet 2016, 388, 3048–3059. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumaraswamy, N. Academic stress, anxiety and depression among college students—A brief review. Int. Rev. Soc. Sci. Humanit. 2013, 5, 135–143. [Google Scholar]

- Murphy, M.C.; Archer, J. Stressors on the college campus: A comparison of 1985-1993. J. Coll. Stud. Dev. 1996, 37, 20–28. [Google Scholar]

- Csikszentmihalyi, M.; LeFevre, J. Optimal experience in work and leisure. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 1989, 56, 815–822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mao, Y.; Roberts, S.; Bonaiuto, M. Optimal Experience and Optimal Identity: A Multinational Examination at the Personal Identity Level. In Flow Experience: Empirical Research and Applications; Harmat, L., Andersen, F., Ullén, F., Wright, J., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moneta, G.B. On the Measurement and Conceptualization of Flow. In Advances in Flow Research; Engeser, S., Ed.; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2012; pp. 23–50. [Google Scholar]

- Delle Fave, A.; Massimini, F.; Bassi, M. Cross-Cultural Advancements in Positive Psychology. In Psychological Selection and Optimal Experience across Cultures: Social Empowerment through Personal Growth; Springer Science+Business Media: New York, NY, USA, 2011; p. 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Csikszentmihalyi, M.; Rathunde, K.; Whalen, S. Talented adolescents: The roots of success and failures. Br. J. Educ. Stud. 1994, 42, 299. [Google Scholar]

- Bonaiuto, M.; Mao, Y.; Roberts, S.; Psalti, A.; Ariccio, S.; Ganucci Cancellieri, U.; Csikszentmihalyi, M. Optimal Experience and Personal Growth: Flow and the Consolidation of Place Identity. Front. Psychol. 2016, 7, 1654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Larson, R.; Csikszentmihalyi, M.; Freeman, M. Alcohol and marijuana use in adolescents’ daily lives: A random sample of experiences. Int. J. Addic. 1984, 19, 367–381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Collins, A.L.; Sarkisian, N.; Winner, E. Flow and happiness in later life: An investigation into the role of daily and weekly flow experiences. J. Happiness Stud. 2009, 10, 703–719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Csikszentmihalyi, M.; Schneider, B. Becoming Adult: How Teenagers Prepare for the World of Work; Basic Books: New York, NY, USA, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Jordan, C.H.; Zeigler-Hill, V.; Cameron, J.J. Self-Esteem. In International Encyclopedia of the Social & Behavioral Sciences; Wright, J.D., Ed.; Elsevier: Oxford, UK, 2015; pp. 522–528. [Google Scholar]

- Martin-Albo, J.; Nunez, J.L.; Navarro, J.G.; Grijalvo, F. The rosenberg self-esteem scale: Translation and validation in university students. Span. J. Psychol. 2007, 10, 458–467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MacDonald, G.; Leary, M.R. Individual Differences in Self-Esteem. In Hand Book of Self-esteem and Identity, 2nd ed.; Leary, M.R., Tangney, J.P., Eds.; The Guilford Press: New York, NY, USA; London, UK, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Stinson, J.; Wilson, R.; Gill, N.; Yamada, J.; Holt, J. A systematic review of Internet-based self-management interventions for youth with health conditions. J. Pediatr. Psychol. 2009, 34, 495–510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, D.; Kim, J. Study on the Effect of the Cognitive Performance, Self-Efficacy and Self-Esteem on the Players’ Flow Experience during Playing Online Games. J. Korea Game Soc. 2013, 13, 5–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khang, H.; Kim, J.K.; Kim, Y. Self-traits and motivations as antecedents of digital media flow and addiction: The Internet, mobile phones, and video games. Comput. Human Behav. 2013, 29, 2416–2424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adlai-Gail, W. Exploring the Autotelic Personality. Unpublished. Ph.D. Thesis, University of Chicago, Chicago, IL, USA, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Wells, A.J. Self-Esteem and Optimal Experience. In Optimal Experience: Psychological Studies of Flow in Consciousness; Csikszentmihalyi, M., Csikszentmihalyi, I.S., Eds.; Cambridge University Press: New York, NY, USA, 1988; pp. 327–341. [Google Scholar]

- Asakawa, K. Flow experience, culture, and well-being: How do autotelic Japanese college students feel, behave, and think in their daily lives? J. Happiness Stud. 2010, 11, 205–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mao, Y.; Roberts, S.; Pagliaro, S.; Csikszentmihalyi, M.; Bonaiuto, M. Optimal experience and optimal identity: A multinational study of the associations between flow and social identity. Front. Psychol. 2016, 7, 67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bandura, A. Social Cognitive Theory. In Handbook of Theories of Social Psychology; van Lange, P.A.M., Kruglanski, A.W., Higgins, E.T., Eds.; Sage Publications Ltd.: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2012; Volume 1, pp. 349–373. [Google Scholar]

- Bandura, A. Self-Efficacy: The Exercise of Control; W. H. Freeman and Company: New York, NY, USA, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Elias, S.M.; MacDonald, S. Using past performance, proxy efficacy, and academic self-efficacy to predict college performance. J. Appl. Soc. Psychol. 2007, 37, 2518–2531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Honicke, T.; Broadbent, J. The influence of academic self-efficacy on academic performance: A systematic review. Educ. Res. Rev. 2016, 17, 63–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Talsma, K.; Schuz, B.; Schwarzer, R.; Norris, K. I believe, therefore I achieve: A meta-analytic cross-lagged panel analysis of self-efficacy and academic performance. Learn. Individ. Differ. 2018, 61, 136–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joo, Y.J.; Oh, E.; Kim, S.M. Motivation, instructional design, flow and academic achievement at Korean online University: A structural equation modeling study. J. Comput. High. Educ. 2015, 27, 28–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mesurado, B.; Richaud, M.C.; Mateo, N.J. Engagement, Flow, Self-Efficacy, and Eustress of University Students: A Cross-National Comparison Between the Philippines and Argentina. J. Psychol. 2016, 150, 281–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fullagar, C.J.; Knight, P.A.; Sovern, H.S. Challenge/Skill balance, flow, and performance anxiety. Appl. Psychol. Int. Rev. 2013, 62, 236–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saavedra, R.; Kwun, S.K. Affective states in job characteristics theory. J. Organ. Behav. 2000, 21, 131–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Fried, Y.; Ferris, G.R. The validity of the job characteristics model: A review and a meta-analysis. Pers. Psychol. 1987, 40, 287–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosenberg, M. Society and the Adolescent Self-Image; Princeton University Press: Princeton, NJ, USA, 1965. [Google Scholar]

- Cleary, T.J.; Zimmerman, B.J. Teachers’ perceived usefulness of strategy microanalytic assessment information. Psychol. Sch. 2006, 43, 149–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dinther, M.; Dochy, F.; Segers, M. Factors affecting students' self-efficacy in higher education. Educ. Res. Rev. 2011, 6, 95–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iancu, L.; Bodner, E.; Ben-Zion, I.Z. Self-esteem, dependency, self-efficacy and self-criticism in social anxiety disorder. Compr. Psychiatr. 2015, 58, 165–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brechan, I.; Kvalem, I.L. Relationship between body dissatisfaction and disordered eating: Mediating role of self-esteem and depression. Eat. Behav. 2015, 17, 49–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lin, C.C. Self-esteem mediates the relationship between dispositional gratitude and well-being. Pers. Individ. Differ. 2015, 85, 145–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arslan, G. Psychological maltreatment, emotional and behavioral problems in adolescents: The mediating role of resilience and self-esteem. Child Abuse Neglect. 2016, 52, 200–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bajaj, B.; Robins, R.W.; Pande, N. Mediating role of self-esteem on the relationship between mindfulness, anxiety, and depression. Pers. Individ. Differ. 2016, 96, 127–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fredrickson, B.L. The role of positive emotions in positive psychology: The broaden-and-build theory of positive emotions. Am. Psychol. 2001, 56, 218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riva, E.; Freire, T.; Bassi, M. The Flow Experience in Clinical Settings: Applications in Psychotherapy and Mental Health Rehabilitation. In Flow Experience: Empirical Research and Applications; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Waterman, A.S. Two conceptions of happiness: Contrasts of personal expressiveness (eudaimonia) and hedonic enjoyment. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 1993, 64, 678–691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwartz, S.J. Predicting identity consolidation from self-construction, eudaimonistic self-discovery, and agentic personality. J. Adolesc. 2006, 29, 777–793. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwartz, S.J.; Waterman, A.S. Changing interests: A longitudinal study of intrinsic motivation for personally salient activities. J. Res. Pers. 2006, 40, 1119–1136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waterman, A.S.; Schwartz, S.J.; Goldbacher, E.; Green, H.; Miller, C.; Philip, S. Predicting the subjective experience of intrinsic motivation: The roles of self-determination, the balance of challenges and skills, and self-realization values. Pers. Soc. Psychol. Bull. 2003, 29, 1447–1458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Waterman, A.S.; Schwartz, S.J.; Conti, R. The implications of two concept of happiness for the understanding of intrinsic motivation. J. Happiness Stud. 2008, 9, 41–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lovibond, S.H.; Lovibond, P.F. Manual for the Depression Anxiety Stress Scales, 2nd ed.; Psychology Foundation: Sydney, Australia, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Stagg, S.D.; Eaton, E.; Sjoblom, A.M. Self-efficacy in undergraduate students with dyslexia: A mixed methods investigation. Br. J. Spec. Educ. 2018, 45, 26–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braun Santos, D.; Mendes-Da-Silva, W.; Flores, E.; Norvilitis, J.M. Predictors of credit card use and perceived financial well-being in female college students: A Brazil-United States comparative study. Int. J. Consum. Stud. 2016, 40, 133–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MacKinnon, D.P.; Coxe, S.; Baraldi, A.N. Guidelines for the Investigation of Mediating Variables in Business Research. J. Bus. Psychol. 2012, 27, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kirchner, J.M.; Bloom, A.J.; Skutnick-Henley, P. The relationship between performance anxiety and flow. Med. Probl. Perform. Artist. 2008, 23, 59–65. [Google Scholar]

- Csikszentmihalyi, M. Creativity: Flow and the Psychology of Discovery and Invention; ProQuest: Ann Arbor, MI, USA, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Tian, Q. Intergeneration social support affects the subjective well-being of the elderly: Mediator roles of self-esteem and loneliness. J. Health Psychol. 2016, 21, 1137–1144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vass, V.; Morrison, A.P.; Law, H.; Dudley, J.; Taylor, P.; Bennett, K.M.; Bentall, R.P. How stigma impacts on people with psychosis: The mediating effect of self-esteem and hopelessness on subjective recovery and psychotic experiences. Psychiatr. Res. 2015, 230, 487–495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lebuda, I.; Csikszentmihalyi, M. Me, Myself, I, and Creativity: Self-Concepts of Eminent Creators; The Creative Self; Academic Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2017; Volume 12, pp. 137–152. [Google Scholar]

- Delle Fave, A.; Massimini, F. The investigation of Optimal Experience and Anxiety. Eur. Psychol. 2005, 10, 264–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).