Reviving an Unpopular Tourism Destination through the Placemaking Approach: Case Study of Ngawen Temple, Indonesia

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

3. Research Methodology

3.1. Case Study

3.2. Method

4. Results

4.1. Visitor Survey Results

4.1.1. Visitor’s Age

4.1.2. Origin of Tourists in Ngawen Temple

4.1.3. The Frequency of Tourist Visits

4.1.4. Traveler Information Resources

4.1.5. Visit Duration

4.1.6. Visitors’ Spending

4.1.7. Visitor Pull Factors

4.1.8. Tourist Repulsive Factors

4.1.9. Tourist Needs

4.1.10. Information Needs in the Area

4.2. Visitor Flows Results

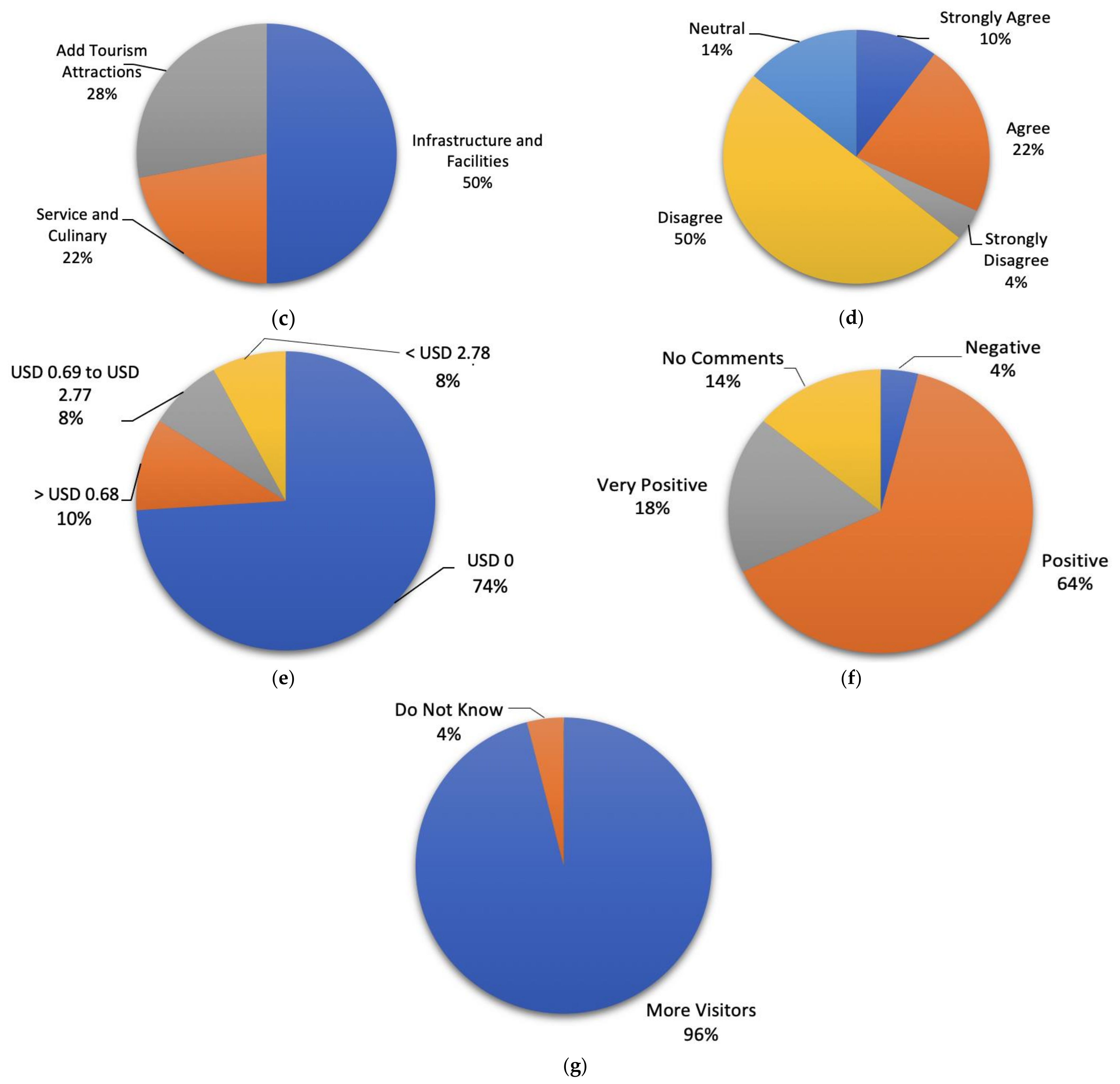

4.3. Community Survey Results

4.3.1. Perceptions of Ngawen Village Community (“Why Do Tourists Visit the Temple?”)

4.3.2. Perceptions of the Ngawen Village Community about Things That Are Not/Less Interesting about the Attractiveness of Ngawen Temple

4.3.3. The Suggestion to Increase Visits to Ngawen Temple

4.3.4. Overcrowd

4.3.5. Economic Impact on Local Community

4.3.6. Impact of Tourism Activities in Ngawen

4.3.7. Visitor Growth Preferences in Ngawen

5. Discussion

6. Conclusions

7. Implications of the Study

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Woodside, A.G. Solving the core theoretical issues In consumer behavior In tourism. In Advances in Culture, Tourism and Hospitality Research; Emerald Publishing Limited: Bingley, UK, 2017; Volume 13, pp. 141–168. ISBN 1-871317-32-0. [Google Scholar]

- Aranburu, I.; Plaza, B.; Esteban, M. Sustainable Cultural Tourism in Urban Destinations: Does Space Matter? Sustainability 2016, 8, 699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Han, J.H.; Lee, M.J.; Hwang, Y.S. Tourists’ Environmentally Responsible Behavior in Response to Climate Change and Tourist Experiences in Nature-Based Tourism. Sustainability 2016, 8, 644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- UNWTO. Growth in International Tourist Arrivals Continues to Outpace the Economy; World Tourism Baromoter: Madrid, Spain, 2020; Volume 18, pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Magelang Regency. BPS-Statistics of Magelang Regency (Magelang Regency in Figures; BPS Kab. Magelang: Mungkid, Indonesia, 2020; ISBN 2338-8048. Available online: https://bit.ly/3pWQ6kx (accessed on 8 December 2020).

- Magelang Regency Youth and Sports Tourism Office. Tourist Visit Data in Magelang Regency 2014–2018; Data Provided by the Official Staff during Interview; Magelang Regency Youth and Sports Tourism Office: Magelang, Indonesia, 2 December 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Bujdosó, Z.; Dávid, L.; Tőzsér, A.; Kovács, G.; Major-Kathi, V.; Uakhitova, G.; Katona, P.; Vasvári, M. Basis of Heritagization and Cultural Tourism Development. Procedia Soc. Behav. Sci. 2015, 188, 307–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- World Tourism Organization. UNWTO Annual Report 2016; UNWTO: Madrid, Spain, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Yi-fong, C. The Indigenous Ecotourism and Social Development in Taroko National Park Area and San-Chan Tribe, Taiwan. GeoJournal 2012, 77, 805–815. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fatimah, T. The Impacts of Rural Tourism Initiatives on Cultural Landscape Sustainability in Borobudur Area. Procedia Environ. Sci. 2015, 28, 567–577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Margaryan, L. A Review of: Heritage, Conservation and Communities. Engagement, Participation and Capacity Building, Edited by Gill Chitty. Tour. Geogr. 2018, 20, 573–575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Mathis, E.F.; Kim, H.L.; Uysal, M.; Sirgy, J.M.; Prebensen, N.K. The Effect of Co-Creation Experience on Outcome Variable. Ann. Tour. Res. 2016, 57, 62–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Figueroa, E.B.; Rotarou, E.S. Sustainable Development or Eco-Collapse: Lessons for Tourism and Development from Easter Island. Sustainability 2016, 8, 93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Saarinen, J.; Rogerson, C.M.; Hall, C.M. Geographies of Tourism Development and Planning. Tour. Geogr. 2017, 19, 307–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wouters, M. Socio-Economic Effects of Concession-Based Tourism in New Zealand’s National Parks; New Zealand Department of Conservation: Wellington, New Zealand, 2011; ISBN 978-0-478-14888-6. [Google Scholar]

- Gossling, S. Market Integration and Ecosystem Degradation: Is Sustainable Tourism Development in Rural Communities a Contradiction in Terms? Environ. Dev. Sustain. 2003, 5, 383–400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Boccia, F.; Di Gennaro, R.; Sarnacchiaro, P.; Sarno, V. Tourism Satisfaction and Perspectives: An Exploratory Study in Italy. Qual. Quant. 2019, 54, 1565–1576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wood, M.E. Ecotourism: Principles, Practices & Policies for Sustainibility, 1st ed.; UNEP: Burlington, VT, USA, 2002; ISBN 92-807-2064-3. [Google Scholar]

- Dolnicar, S. Market segmentation in tourism. In Tourism Management: Analysis, Behaviour and Strategy; Cambridge: Canbridge, UK, 2008; pp. 129–150. ISBN 978-1-84593-323-4. [Google Scholar]

- Noor, F.; Nair, V.; Mura, P. Towards the Conceptualization of a Slow Tourism Theory for a Rural Destination. Hosp. Tour. 2015, 2015, 175–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calzati, V.; de Salvo, P. Slow Tourism: A Theoretical Framework; Clancy, M., Ed.; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2017; ISBN 978-1-315-68671-4. [Google Scholar]

- Guiver, J.; McGrath, P. Slow Tourism: Exploring the Discourses. Dos. Algarves A Multidiscip. E-J. 2016, 27, 11–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hotimah, O.; Wirutomo, P.; Alikodra, H.S. Conservation of World Heritage Botanical Garden in an Environmentally Friendly City. Procedia Environ. Sci. 2015, 28, 453–463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Harlov-Csortán, M. Adaptation History of an Earth-Built World Heritage. In Proceedings of the Conservation et Gestion du patrimoine; CRAterre: Villefontaine, France, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, R.; Smith, L. Bonding and Dissonance: Rethinking the Interrelations Among Stakeholders in Heritage Tourism. Tour. Manag. 2019, 74, 212–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santa, E.D.; Tiatco, S.A. Tourism, Heritage and Cultural Performance: Developing a Modality of Heritage Tourism. Tour. Manag. Perspect. 2019, 31, 301–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Milne, S.; Deuchar, C.; Histen, S.; Palumbo, V.; Rakei, C.; Fischer, R.; Bell, D. Tourism & Urban Development: Building Local Economies & Sense of Place-Kingsland; Auckland University of Technology-Alber Eden Local Board-NZTRI: Auckland, New Zealand, 2012; p. 72. [Google Scholar]

- Asadpourian, Z.; Rahimian, M.; Gholamrezai, S. SWOT-AHP-TOWS Analysis for Sustainable Ecotourism Development in the Best Area in Lorestan Province, Iran. Soc. Indic. Res. 2020, 152, 289–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thapa, S.; Wang, L.; Koirala, A.; Shrestha, S.; Bhattarai, S.; Aye, W.N. Valuation of Ecosystem Services from an Important Wetland of Nepal: A Study from Begnas Watershed System. Wetlands 2020, 40, 1071–1083. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piber, M.; Demartini, P.; Biondi, L. The Management of Participatory Cultural Initiatives: Learning from the Discourse on Intellectual Capital. J. Manag. Gov. 2019, 23, 435–458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Priatmoko, S.; Purwoko, Y. Does the Context of MSPDM Analysis Relevant in Rural Tourism? Case Study of Pentingsari, Nglanggeran, and Penglipuran. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Creative Economics, Tourism and Information Management (ICCETIM) 2019, Yogyakarta, Indonesia, 17–18 July 2019; pp. 15–21. [Google Scholar]

- Purbadi, D. Development of Sustainable Community Empowerment Program Case Study: New Beach Tourism Area. In Proceedings of the Seminar Nasional Hasil Pengabdian Masyarakat (SENDIMAS), Yogyakarta, Indonesia, 20 October 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Corral, S.; Hernandez, J.; Ibanez, M.N.; Ceballos, J.L.R. Transforming Mature Tourism Resorts into Sustainable Tourism Destinations through Participatory Integrated Approaches: The Case of Puerto de La Cruz. Sustainability 2016, 8, 680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Garrod, B.; Fyall, A. Managing Heritage Tourism. Ann. Oftourism Res. 2000, 27, 682–708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toolis, E.E. Theorizing Critical Placemaking as a Tool for Reclaiming Public Space. Am. J. Community Psychol. 2017, 59, 184–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wesener, A.; Fox-Kämper, R.; Sondermann, M.; Münderlein, D. Placemaking in Action: Factors That Support or Obstruct the Development of Urban Community Gardens. Sustainability 2020, 12, 657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Sepe, M. Placemaking, Livability and Public Spaces. Achieving Sustainability through Happy Places. J. Public Space 2017, 2, 63–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Johnson, P.-A. The Theory of Architecture: Concepts, Themes and Practices, 1st ed.; Van Nostrand Reinhold: New York, NY, USA, 1994; ISBN 0-442-01344-2. [Google Scholar]

- Gato, M.A.; Costa, P.; Cruz, A.R.; Perestrelo, M. Creative Tourism as Boosting Tool for Placemaking Strategies in Peripheral Areas: Insights From Portugal. J. Hosp. Tour. Res. 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Razali, M.K.; Ismail, H.N. Tourism Place-Making at Tourism Destination from a Concept of Governance. IGCESH 2014, 6, 19–21. [Google Scholar]

- Mansilla, J.A.; Milano, C. Becoming Centre: Tourism Placemaking and Space Production in Two Neighborhoods in Barcelona. Tour. Geogr. 2019, 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delconte, J.; Kline, C.S.; Scavo, C. The Impacts of Local Arts Agencies on Community Placemaking and Heritage Tourism. J. Herit. Tour. 2016, 11, 324–335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schiavone, R.; Reijnders, S. Fusing Fact and Fiction: Placemaking through Film Tours in Edinburgh. Eur. J. Cult. Stud. 2020, 136754942095156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Priatmoko, S.; Kabil, M.; Purwoko, Y.; Dávid, L.D. Rethinking Sustainable Community-Based Tourism: A Villager’s Point of View and Case Study in Pampang Village, Indonesia. Sustainability 2021, 13, 3245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nagy, K. Heritage Tourism, Thematic Routes and Possibilities for Innovation. J. Econ. Lit. JEL 2012, 8, 46–53. [Google Scholar]

- Sedyawati, E.; Santiko, H.; Djafar, H. Candi Indonesia Seri Jawa, 1st ed.; Ramelan, W.D.S., Ed.; Direktorat Pelestarian Cagar Budaya dan Permuseuman, Dirjen Kebudayaan, Kementrian Pendidikan dan Kebudayaan: Jakarta, Indonesia, 2013; ISBN 978-602-17669-3-4. [Google Scholar]

- PT Taman Wisata Candi Borobudur Borobudur. Available online: https://borobudurpark.com/temple/borobudur/ (accessed on 2 December 2020).

- Chang, A.Y.P.; Hung, K.P. Development and Validation of a Tourist Experience Scale for Cultural and Creative Industries Parks. J. Destin. Mark. Manag. 2021, 20, 100560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adeyinka-Ojo, S.F.; Khoo-Lattimore, C.; Nair, V. A Framework for Rural Tourism Destination Management and Marketing Organisations. Procedia Soc. Behav. Sci. 2014, 144, 151–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- SurveyMonkey Sample Size Calculator. Available online: https://www.surveymonkey.com/mp/sample-size-calculator/ (accessed on 7 December 2020).

- Maxim, C.; Emilia, C. Cultural Landscape Changes in the Built Environment at World Heritage Sites: Lessons from Bukovina, Romania. J. Destin. Mark. Manag. 2021, 20, 100583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sokil, O.; Zhuk, V.; National Scientific Center «Institute of Agrarian Economics»; Vasa, L. Széchenyi István University Integral Assessment of the Sustainable Development of Agriculture in Ukraine. EA-XXI 2018, 170, 15–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Taheri, B.; Jafari, A. Museums as Playful Venues in the Leisure Society. In The Contemporary Tourist Experience: Concepts and Consequences; Sharpley, R., Stone, P., Eds.; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2012; pp. 201–215. [Google Scholar]

- Tan, E.; Teoh, S. A Nostalgic Peranakan Journey in Melaka: Duo-Ethnographic Conversations between a Nyonya and Baba. Tour. Manag. Perspect. 2019, 32, 100570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| No. | Destination | Year | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2016 | 2017 | 2018 | 2019 | ||

| 1 | Borobudur Temple | 3,795,300 | 3,775,799 | 3,855,285 | 3,989,839 |

| 2 | Ngawen Temple | 26,656 | 28,693 | 19,451 | 33,028 |

| Desired Confidence Level | z-Score |

|---|---|

| 80% | 1.28 |

| 85% | 1.44 |

| 90% | 1.65 |

| 95% | 1.96 |

| 99% | 2.58 |

| Visitors Interview Summary (Main Findings) |

|---|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Community Interview Summary (Main Findings) |

|---|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Priatmoko, S.; Kabil, M.; Vasa, L.; Pallás, E.I.; Dávid, L.D. Reviving an Unpopular Tourism Destination through the Placemaking Approach: Case Study of Ngawen Temple, Indonesia. Sustainability 2021, 13, 6704. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13126704

Priatmoko S, Kabil M, Vasa L, Pallás EI, Dávid LD. Reviving an Unpopular Tourism Destination through the Placemaking Approach: Case Study of Ngawen Temple, Indonesia. Sustainability. 2021; 13(12):6704. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13126704

Chicago/Turabian StylePriatmoko, Setiawan, Moaaz Kabil, László Vasa, Edit Ilona Pallás, and Lóránt Dénes Dávid. 2021. "Reviving an Unpopular Tourism Destination through the Placemaking Approach: Case Study of Ngawen Temple, Indonesia" Sustainability 13, no. 12: 6704. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13126704

APA StylePriatmoko, S., Kabil, M., Vasa, L., Pallás, E. I., & Dávid, L. D. (2021). Reviving an Unpopular Tourism Destination through the Placemaking Approach: Case Study of Ngawen Temple, Indonesia. Sustainability, 13(12), 6704. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13126704