1. Introduction

Innovation is vital to the survival and sustainable development of firms and it is the “engine” of economic growth. Since 1985, China’s patent applications have shown an explosive growth, ranking 14th in the 2020 Global Innovation Index report. China has achieved tremendous development in science and technology and significantly improved its capacity for independent innovation over recent decades. However, original innovation ability in science and technology is seriously insufficient, and the core technology is highly dependent on foreign countries in China, such as the lack of significant original achievement and underlying basic technology. The situation that key technologies are controlled by other countries has not been fundamentally changed [

1]. In addition, not only micro-level strategic innovation behavior problems are prominent, but innovation efficiency also has a large gap when compared with developed economies (i.e., the United States and Japan), which all restrict China’s economic transformation, upgrading and high-quality development [

2,

3]. In consequence, some studies suggest that OFDI is used by emerging economy firms to achieve “overtaking at the corner” in technology, resulting from obtaining cutting-edge technologies [

4]. OFDI is not just the most efficient response for firms to cope with fierce industry competition and to supplement the lack of internal knowledge resources to quickly acquire innovation resources, but also the most rapid and effective growth strategy [

5,

6,

7,

8,

9]. The national strategy attaches great importance to improving the level of firm innovation through OFDI.

In 2000, the fifth plenary session of the 15th CPC Central Committee put forward the strategy of “go global” for the first time, which is also known as the international business strategy. It refers to Chinese firms making full use of “two markets and two resources home and abroad” and to actively participate in international competition and cooperation through foreign direct investment, foreign labor service cooperation, and other forms. The government encourages and supports qualified firms to conduct overseas mergers and acquisitions, deepening mutually beneficial cooperation in overseas resources and realizing the strategy of making China a great modern country with sustainable economic development. With the deepening of the “go global” strategy, OFDI has made significant breakthroughs in both the scale and the field of investment. By the end of 2019, the stock of OFDI by Chinese firms had reached USD 2.2 trillion, covering more than 80% of the world’s countries and regions, and over 27,500 domestic investors had set up 44,000 firms overseas. The scale and fields of OFDI have made significant breakthroughs. Some countries and regions in Europe and the United States are even concerned about the enhancement of the innovation ability of Chinese firms; thus, they have implemented stricter security reviews of the OFDI of Chinese firms. Meanwhile, the COVID-19 pandemic has worsened the political and economic tensions between China and the United States to a certain extent, which has a superimposed impact on the overseas investment of Chinese firms. Therefore, in the current situation that “innovation is the first driving force to guide development”, can fast-growing OFDI promote the innovation of domestic firms? Whether it is for firms or the economic development of a country is an important topic.

Does OFDI promote domestic firms’ innovation? This question has drawn much attention, but the research conclusions are inconsistent. There is extensive literature suggesting that OFDI plays a multichannel role in promoting firms’ innovation. For example, Stiebale argues that direct learning and obtaining complementary R&D resources from overseas target firms through OFDI is beneficial to breaking the path dependence of technological innovation, changing the original firms’ innovative thinking, and promoting firms’ innovation [

10]. Yan et al. argue that firms transfer R&D technologies to foreign countries through OFDI to improve the efficiency of the allocation of innovation resources, which enables enterprises in their home countries to use core resources for domestic innovation [

11]. Jia et al. suggest that OFDI can bring about the economies of scale effect, which can reduce production costs. Subsequently, it promotes domestic firms to increase human capital and R&D investment through the profit feedback effect, so as to improve productivity and realize independent innovation [

12]. However, other studies show that OFDI has a negative effect on firms’ innovation. The resource integration and adjustment costs brought by the disadvantage of outsiders and new entrants, cultural systems, and other differences when firms undertake OFDI lead to technology spillover and unsatisfactory performance [

13,

14,

15]. At the same time, large-scale OFDI tends to crowd out domestic investment, which is not conducive to the independent innovation of the home economies [

16]. Another perspective is that OFDI’s impact on firms’ domestic innovation is uncertain [

17,

18]. Therefore, conclusions on the impact of OFDI on firms’ innovation are inconsistent. Most studies argue that this is restricted by factors such as OFDI motivation, industrial heterogeneity of firms, regional differences, characteristics of host countries, and the coexistence of “positive gradients” and “negative gradients”, which leads to greater differences between different OFDI entry modes [

19,

20,

21]. Resource-based theory holds that the unique resources available to the firm determine their competitive advantage [

22]. Different entry modes of OFDI mean different resource acquisition channels, internal and external costs, and risk exposure of multinational firms, which directly affect the innovation of multinational firms.

Therefore, some authors emphasize that the meaning of greenfield investment and cross-border M&A should be distinguished when studying the entry modes of OFDI. Cross-border M&A refers to the merger and acquisition activities of the home firms in order to obtain the controlling right of the host country firms. Greenfield investment refers to the activities in which investors set up local firms in accordance with the laws of the host country in order to acquire the ownership of part or all of the assets. Current literature mainly studies OFDI entry modes from three aspects. Firstly, schools of thought may be classified into economic and business studies, such as industrial organization, financial economics, strategic management, and organizational behavior [

21,

23,

24]. Secondly, some literature studies OFDI entry modes from the perspective of industry and national factors, such as the industry’s technology and R&D density, the country’s market growth potential, culture, and institutions etc. [

23]. Thirdly, other literature is based on the perspective of heterogeneous enterprises. Instead of the single heterogeneity of productivity, they gradually expand to the scale of enterprises, capital structure, financing constraints on R&D investment, and the level of economic development, geographical distance, tax level, institutional environment, and other factors [

25,

26,

27,

28,

29,

30,

31]. The entry modes of OFDI have always been the focus of academic research, but it is generally limited to the analysis of the selection mechanism and influencing factors. Very few studies have considered the internal relationship between OFDI entry modes and firms’ innovation.

In recent years, the development trend of M&A and greenfield investment of Chinese multinational firms has begun to diverge. Under the background of a sharp decline in the total amount of global and Chinese OFDI, greenfield investment flows by Chinese firms, which are mainly characterized by the transfer of production capacity, have shown a trend of steady appreciation. In 2017, it rose to USD 31.6 billion, an increase of 53.7% over the previous year. In 2018, it fell slightly to USD 29.7 billion, a decrease of 6.0%, and then hit a record high in 2019, reaching USD 37.2 billion, an increase of 25.3%. By contrast, M&A transaction flows by firms with the main motivation of seeking technology and strategic resources fluctuated significantly, from USD 9.46 billion in 2017 to USD 12.02 billion, an increase of 27.1%. However, in 2019, it dropped sharply to USD 1.4 billion, a decrease of 88.4%, showing a cliff-like decline. The market will have a strong wait-and-see mood due to the COVID-19 pandemic, the sharp global economic recession, and the intensifying geopolitical competition among major countries. Therefore, rational evaluation of greenfield investment and cross-border M&A of firms can provide theoretical and empirical support for national policy stability and firms’ OFDI mode selection. It is urgent to conduct a comparative analysis of the impact of greenfield investment and cross-border M&A from the perspective of innovation.

Concurrently, we cannot ignore the role of the government in the ecosystem of open innovation [

32]. Against the background of an imperfect institutional environment, the government is still the major participant in Chinese economic activities. The government has an important influence on the innovation behavior of firms, which often improves the firms’ bargaining power and enhances the competitive platform through the direct allocation of resources in practice, so as to promote the innovation of firms [

33,

34]. Therefore, it is of great significance to study the influence of government resources on the innovation level of OFDI firms.

In recent years, papers on OFDI by emerging economies have grown rapidly; however, there are still the following shortcomings. Firstly, the existing research generally analyzes the impact of OFDI on firms’ innovation, but the research on different entry modes of Chinese multinational firms lacks a systematic and complete explanation and a unified analytical framework or platform to discuss different results. Secondly, previous studies are generally limited to the selection mechanism of OFDI entry modes and the analysis of influencing factors. Little literature focuses on the impact of OFDI entry modes on firms’ innovation performance, which ignores the impact on innovation quality and efficiency. Finally, in a period of economic transformation in China, the government is still the main participant in economic activities. Most of the literature studies the role of the government based on institutional theory, while neglecting the heterogeneous influence of the government on different OFDI entry modes. Based on the above analysis, we select China as the research object, which represents an emerging economy, to study whether OFDI can promote the innovation of domestic enterprises, and to further compare and analyze whether different entry modes of OFDI have the same impact on firms’ innovation. At the same time, we investigate the mediating role of government resources on the innovation effect of OFDI entry modes based on the signal theory.

Possible marginal contributions of this paper are as follows. 1. We constructed a mathematical model to study the impact of OFDI on firms’ innovation, which enriches the cross-study of OFDI and firms’ innovation. 2. Previous comparative studies on the impact of greenfield investment and cross-border M&A on firms’ innovation lack systematic and complete explanations. Moreover, these studies mainly use the data of European and American countries and regions, but rarely used the data of Chinese firms. We provide empirical data from developing countries in this field. 3. Different from previous studies, based on the signal theory, we have confirmed the signal mechanism of greenfield investment and cross-border M&A, and provided empirical basis and theoretical support for the signal function of greenfield investment and cross-border M&A to obtain government resources. The influencing mechanism of OFDI entry modes on innovation effect is extended. 4. Different from most literature focusing on the relationship between OFDI entry modes and firms’ performance, we emphasize the influence on firms’ innovation quantity, quality, and efficiency. We measure the innovation level of firms more comprehensively from multiple perspectives. Against the background of the rapid development of China’s OFDI, but with several doubts, the study of OFDI entry modes from the perspective of innovation can not only provide theoretical and practical support for innovation strategy and OFDI policy at the national level, but also provide a beneficial reference for firms’ innovation and OFDI decision making.

5. Conclusions

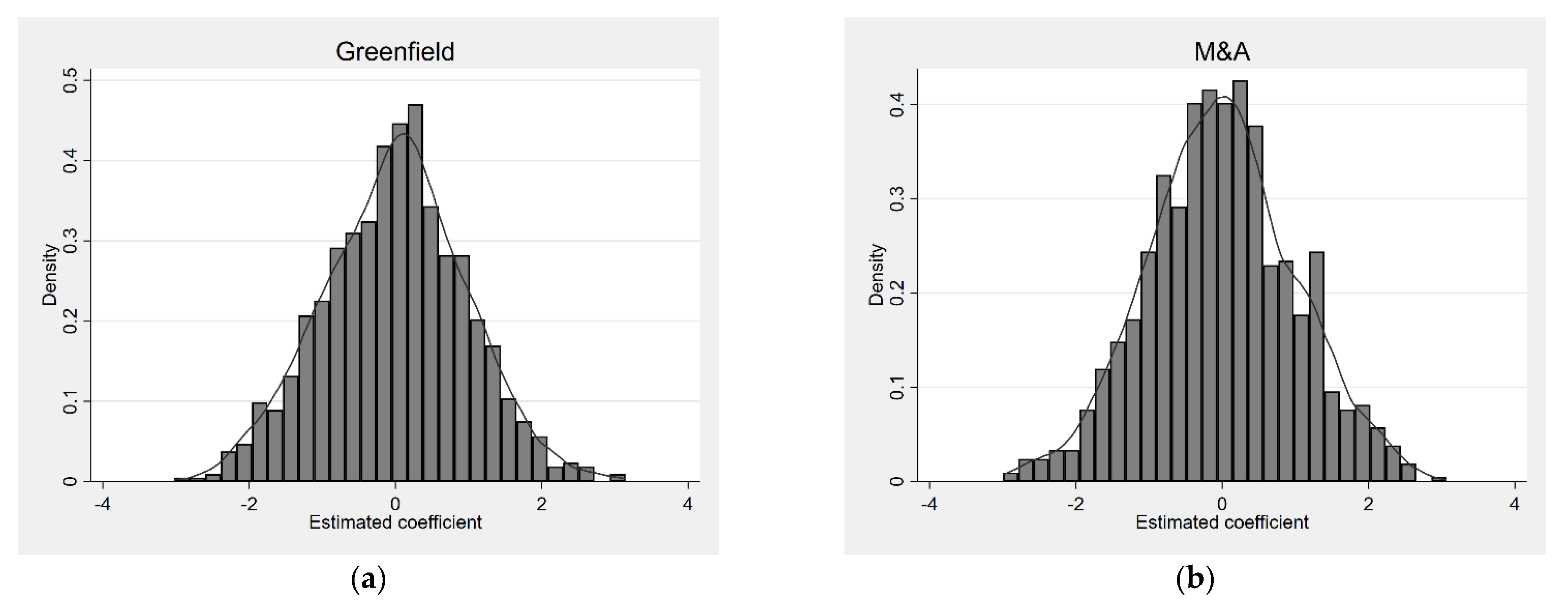

We built a model and used the data of Chinese A-share listed firms as a sample to study whether OFDI and different OFDI entry modes can promote the innovation of Chinese firms, in which we selected the innovation quantity, innovation quality, and innovation efficiency indicators to measure the level of innovation. The results show that OFDI has a significant promoting effect on the level of innovation. Further analysis shows that greenfield investment promotes the innovation quantity better than cross-border M&A, while cross-border M&A plays a stronger role in promoting the innovation quality. Both of the two open modes have a positive effect on the innovation efficiency, and neither of them produces strategic innovation behaviors. As time goes by, the gap between the two impacts on innovation quality is gradually narrowing, and both have sustainable innovation behaviors. From the perspective of mechanism, the signaling effect of the firms’ greenfield and cross-border M&A is conducive to their involvement in government resources, but by contrast, government subsidies have a stronger intermediary effect on cross-border M&A and the channel of effect is more obvious.

Influenced by the COVID-19 pandemic, the sharp global economic recession, and the intensifying geopolitical competition among major countries, the rational evaluation of greenfield investment and cross-border M&A of enterprises can provide reference for China and other emerging countries to implement OFDI. Therefore, this study has profound practical significance for government decision making and firms’ managers. From the perspective of the government, it is still a major participant in economic activities, whose role cannot be ignored in the ecosystem composed of open innovation. The government should unswervingly expand the opening up to the outside world and send a stronger signal of government support to the market, so as to promote firms to obtain resources and promote innovation to a greater extent. However, we cannot blindly encourage all firms to go out, but rather to cultivate and foster a number of high-quality firms with international competitive advantages which can choose the appropriate way to go out. The government should overcome the fetters of an unfavorable environment and create a fair competition environment for firms. Specifically, the government should do a good job in investment service and promotion, and strengthen policy communication and coordination with the host government, and at the same time, with relatively abundant capital, allocate and utilize global human and scientific and technological resources to promote the development of firms’ innovation levels. From the perspective of enterprise managers, firms should have an international vision and actively go out to integrate into the global innovation network. Before “go out”, firms should combine their own scale, performance, experience, and other resource advantages. In addition, they should fully study the market environment of the host country and choose the optimal entry mode, which directly affects internal and external resource commitments, costs, risk level, and the company’s ultimate level of innovation. After “go out”, firms should make full use of the perfect innovation infrastructure, innovation transformation platform, and the accumulation of innovation elements in the region to improve their independent R&D and innovation capabilities.

This study is not without limitations and future work may explore the following issues. Firstly, patent as an agency indicator of innovation. Enterprises may have different patent application preferences due to different technology protection strategies, and some enterprises improve the level of innovation by acquiring intangible proprietary technology, so patents could not fully represent enterprise innovation. Future research could build a more perfect enterprise innovation index measurement system. Secondly, in the selection of samples, non-listed companies were excluded due to the unavailability of key information. If a sample of non-listed companies is added for comparative analysis, the research results may be more convincing. Future research can overcome this deficiency based on multiple case studies. Finally, this paper is an exploratory attempt to study the impact of China’s listed companies’ OFDI entry modes on enterprise innovation. In the future, we may study the impact of formal institutional distance and informal institutional distance and the embeddedness of innovation networks on the innovation of enterprises in their home countries under different OFDI modes.