2.1. Organizational Citizenship Behavior for the Environment

Climate change is a global problem, perhaps the most urgent and the greatest challenge facing humanity. Scientists believe that the main cause of climate change is human activities, and organizations are a major channel of such activities. In response, organizations have begun to adopt formal and informal environmental management systems; however, merely relying on these systems is not enough. Rather, the successful implementation of organizational environmental protection projects depends largely on employees’ voluntary participation and active cooperation [

2]. Environmentally engaged employees can act as a social innovator and take part in a wide range of activities, such as participating in intrapreneurial innovation to promote environmental sustainability and creating partnerships with other stakeholders [

12], hence the need to understand employees’ voluntary behaviors directed toward the environment.

OCBE is a voluntary environmental behavior that has recently gained interest in this light. Extending the concept of organization citizenship behavior (OCB), Daily et al. [

1] defined OCBE as “environmental efforts that are discretionary acts, within the organizational setting, not rewarded or required from the organization.” Later, Boiral and Paillé [

4] divided OCBE into the three categories of eco-initiatives, eco-civic engagement, and eco-helping. Eco-initiatives aim at improving environmental practice and performance. Eco-civic engagement refers to employees’ voluntary participation in the organization’s environmental projects and activities. Eco-helping refers to employees’ willingness to help colleagues in the workplace to foster their concern about environmental issues. Paillé et al. [

3] verified the feasibility of this classification through an empirical study.

There are alternative conceptualizations of employees’ pro-environmental behavior, including employee green behavior proposed by Ones and Dilchert [

13]. Their taxonomy of green behaviors includes (1) avoiding harm, such as prevention of pollution, (2) conserving, such as recycling, (3) working sustainably, such as changing how work is done, (4) influencing others, such as educating and training for sustainability and (5) taking initiative, such as initiating programs and policies. Although closely related to OCBE, employee green behaviors are different from OCBE in that they are not confined to extra-role behavior and may include behaviors in task performance. Although employee green behaviors are a meaningful construct to be studied in the context of environmental sustainability, they may differ by job and by industry considerably. For example, creating eco-friendly products may constitute regular task performance behavior in green industries. As such, employee green behaviors are not well suited to our setting covering corporations in diverse industries.

Several factors affect OCBE. First, organizational environmental policy can stimulate employees’ OCBE through their environmental commitment [

7]. Paillé et al. [

3] found that environmental management practices increase subordinates’ perceptions of organizational support and supervisor support and enhance organizational commitment, which then generates stronger OCBE through reciprocity norms. Empowerment and training can also improve enthusiasm about the environment, leading to OCBE [

14,

15]. In a manufacturing firm with high level of green activities, Hameed et al. [

16] found that employees’ perception of green HRM practice resulted in higher OCBE through green employee empowerment. Pham et al. [

17] also found that green training improves OCBE among employees in the hotel industry. Erdogan et al. [

15] also showed that organizations’ environmental enthusiasm promotes environmental protection attitudes and OCBE.

Second, leadership may affect subordinates’ OCBE as well. Higher levels of consciousness among managers entail greater employee participation in ecological initiatives and ecological help [

18,

19]. Graves et al. [

20] demonstrated that environmental transformational leadership can promote employees’ environmental behaviors. Han et al. [

19] also found that responsible leadership promoted OCBE through identification with the leader. Luu [

21] found that environmentally specific servant leadership strengthens the relationship between green HR practices and OCBE.

Finally, individual characteristics may also affect OCBE. Employees may differ in terms of environmental awareness [

22], environmental passion [

23], and value orientation toward environmental problems [

24], which could lead to different degrees of OCBE. Individual differences are often found to moderate the relationship between environment management practice and OCBE [

25] and the relationship between leadership and OCBE [

26].

2.2. Employee Perception of SRHRM

Since Bowen [

27] first proposed the concept of corporate social responsibility (CSR) in the 1950s, it has attracted much attention from academics and practitioners. Per Carroll’s [

28] definition, CSR means that an organization should not only achieve economic goals and fulfill legal responsibilities but also consider their ethical and discretionary responsibilities to employees and external stakeholders, including shareholders, suppliers, customers, communities, governments, and NGOs in the process. With the extensive conceptual development of CSR and numerous relevant studies, it has increasingly been regarded as a mechanism by which organizations can achieve success and sustainable development in the long term [

29,

30]. Externally, the fulfillment of CSR not only can improve organizations’ social reputation and corporate image but can also help them enter the international market and improve long-term profitability [

31,

32]. Internally, in the knowledge-based economy where human capital is considered the core driver of organizational competitive advantage, actively fulfilling CSR and establishing a good CSR image can help organizations attract and retain excellent talent [

33,

34,

35,

36]. Thus, the active fulfillment of CSR has far-reaching significance for organizations’ long-term survival and development.

Employees are not only the object of CSR initiatives but also the backbone of organizational attempts to fulfill CSR. Organizations can promote CSR initiatives by encouraging employees’ enthusiasm; concentrating their intelligence, attitude, and willpower; and building up the conducive work environment and procedures. Firms can achieve these goals by integrating the CSR concept into their human resource management practices. The concept of socially responsible human resource management (SRHRM) has gradually developed from these needs [

10,

37]. There are three major components in an SRHRM system: legal compliance HRM (LCHRM), employee-oriented HRM (EOHRM), and general CSR facilitation HRM (GFHRM) [

10]. LCHRM requires firms to comply with local labor laws and meet the standards set by the International Labor Organization, relating mainly to equal opportunity, working hours, health and safety, minimum wages, and the prohibitions against forced labor and child labor [

38]. EOHRM emphasizes satisfying the employees’ personal and family needs, going beyond the minimum legal requirements as much as possible, such as providing organizational support to employees, ensuring justice in the workplace, and satisfying employees’ need for personal development. GSHRM involves the application of HRM policy and practice that enables participation in general CSR initiatives, such as recruiting CSR-oriented employees, evaluating them, and rewarding them for their CSR contributions.

It should be noted that we focus on the employee perception of SRHRM in our empirical investigation. Ahmad et al. [

39] emphasized the importance of studying CSR as perceived at the individual employee level, which they dubbed as micro-level CSR (MCSR). Zhang et al. [

40] studied employees at 50 companies in China and demonstrated that the effect of SRHRM on employee wellbeing varied depending on employees’ attribution of corporate motives in the implementation of SRHRM. In a meta analysis, Wang et al. [

41] also showed that employee’s perceived CSR were related to various outcome, including organizational identification, organizational trust, and organizational commitment.

Why would employee perception of SRHRM affect OCBE? There are at least three theoretical perspectives that we can adopt to answer this question: social exchange theory, social identity theory, and conservation of resources theory. First, when firms support socially responsible practices that transcend organizational boundaries, they are more likely to be perceived as benevolent and caring, and have its actions reciprocated by employees [

42]. Social exchange theory proposes that reciprocity norms are a powerful motivator for employee behavior [

43]. For example, Rainerie and Paille [

7] found that pro-environment management policy increased OCBE.

Second, when employees recognize that their company benefits various stakeholders through CSR initiatives, they will be more likely to identify with the company and be motivated to perform environmentally friendly behaviors in line with the company’s goals, mission, and values [

44], which is in line with social identity theory [

45]. In a meta-analysis, Riketta [

46] found that organizational identification was closely related to extra-role behavior. In a study of a major Israeli airline carrier, Mozes et al. [

47] found that active participants of volunteering activities showed higher level of organizational identification than non-active participants. Tian and Robertson [

48] found that employees’ perceptions of CSR can affect their participation in voluntary environmental behaviors through organizational identification.

Third, SRHRM may encourage employees to engage in OCBE by providing necessary resources, such as knowledge and skills, that could enable socially responsible employee behavior. Conservation of resources theory proposes that resource acquisition could be a strong motivating factor for employee behavior, as individuals try to avoid stress that comes from resource loss [

49]. In a study of tour operators in Vietnam, Luu [

21] argued that green HRM may create an atmosphere of green learning among members, which could be utilized as organizational resources for green behavior. They indeed found that green HRM increased OCBE through collective green crafting. In a study of top management teams and frontline workers in China, Paille et al. [

6] found that strategic HRM increased OCBE more strongly when employees perceive that the organization grants them the decision-making latitude and necessary resources to engage in pro-environmental behavior.

Based on these considerations, we propose the following hypothesis:

Hypothesis 1. SRHRM will have a positive effect on OCBE.

2.3. Proactive Motivation Model for SRHRM

Scholars have always recognized that exploring the antecedents and psychological mechanisms of employee initiative is crucial for guiding the practice of organizational change [

11]. Parker et al. [

11] proposed proactive motivation theory and pointed out that generating individual proactive behavior is a process of cognition and motivation, and contextual variables in an organization can influence employees’ personal initiative through the mediation of three proximal motivational states: “can do,” “reason to,” and “energized to” motivation.

First, performing proactive behaviors, which usually means setting higher goals to change the status quo, requires individuals’ firm belief that they “can do” it. “Can do” motivation refers to an individuals’ belief in their ability to change or adapt to the environment, which stems mainly from their self-efficacy. Just as others are likely to doubt and resist employees when they take initiative to improve their work processes in response to changing demands, individuals’ proactive behaviors in the workplace often entail high psychological risks, while strong self-efficacy will enhance individuals’ will to overcome these obstacles [

50].

Second, a “can do” mentality may not lead to proactive behavior absent a compelling “reason to” act. In general, when there is strong regulatory guidance in the organizational context, individuals are likely to take initiative to achieve organizational goals. However, when the organizational context is fuzzy and lacks well-defined goals, individuals’ proactive behavior requires greater internal drive—namely, “reason to” motivation. According to temporal construal theory, the desirability of future goals (the “why” of an action) is a stronger determinant than feasibility (the “how” of an action) when goals concern the longer term rather than the near term [

51].

Lastly, to be “energized to” take initiative, individuals also must activate “hot” affective states in addition to the “cold” motivational states of “can do” and “reason to.” Previous studies have shown that positive affect can broaden individuals’ momentary action-thought repertoires and help them solve problems creatively, weigh the advantages and disadvantages flexibly, set more challenging proactive goals, and take the initiative to achieve these goals [

11,

52].

Despite the potential to explain complex problems regarding employee behavior in an organization, the role of human resource management practice in promoting employee proactivity has not been explored until recently [

53]. Hong et al. [

54] established an integrative multilevel model to explicate how contextual factors influence employees’ subsequent personal initiative by shaping their proactive motivational states. They found that initiative-enhancing human resource management systems interact with empowering leadership to create a climate of initiative, which stimulates employees’ motivational states of “can do” (role-breadth self-efficacy), “reason to” (intrinsic motivation), and “energized to” (activated positive affect), thereby driving personal initiative. Lee et al. [

53] also examined how HRM practices promote three motivational states, namely, role breadth self-efficacy, felt responsibility for change, and trust in management and increase employee innovative behavior as a result.

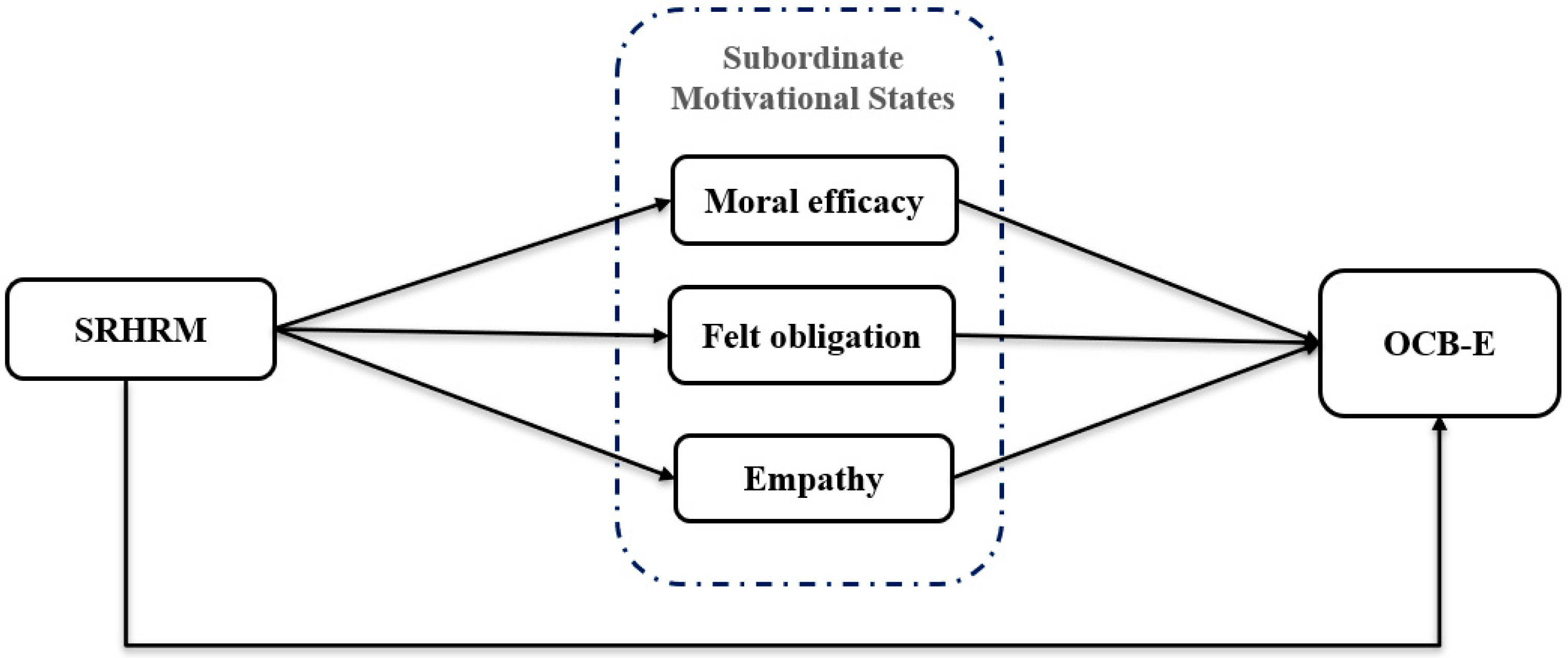

We propose that SRHRM practices provide an important social process that affects proactive motivational states of employees, antecedents to OCBE. We further propose that SRHRM practices will evoke proactive motivational states that are moral and other-centered in nature, as SRHRM encourages employees to go beyond the narrow pursuit of self-interest. Hence, we chose moral efficacy, rather than self-efficacy, as a “can do” motivation. In the same logic, we chose felt obligation, rather than intrinsic motivation, as a “reason to” motivation. Finally, we chose empathy, which is other-centered in nature, rather than positive affectivity, as a “energized to” motivation.

Moral Efficacy: Moral efficacy refers to “the belief of individuals that they can effectively sustain moral performance and behave in accordance with moral requirements when faced with moral dilemmas” [

55]. Hannah et al. [

55] posited that individuals may rely on their own moral judgment to find solutions to moral dilemmas, but that they may not necessarily put them into practice, which may be due to a lack of confidence, thus reducing their moral intentions. The concept of moral efficacy bridges the gap between moral judgment and moral behavior and provides a new perspective on the latter’s roots.

Moral efficacy can help individuals commence the series of actions needed to make correct moral decisions under specific conditions [

50]. Even in facing moral dilemmas, individuals with high moral efficacy believe that they can effectively address achieve high moral performance, behaving in accordance with moral requirements [

55]. Moreover, moral efficacy can give individuals the confidence to engage in prosocial behavior, facilitating belief in their ability to help others and thereby increasing their willingness to behave prosocially (e.g., OCB) [

56]. Hannah et al. [

55] found that moral efficacy has a positive impact on individuals’ moral cognition and propensity, encouraging them to behave ethically. Xu et al. [

56] found that employees’ moral efficacy positively predicts their voice behavior when faced with abusive supervision. Thus, it is likely that moral efficacy encourages ethical behaviors in organizational settings, including OCBE.

Research has also shown that moral efficacy mediates the relationship between ethical leadership and various prosocial employee behaviors. Schaubroeck et al. [

57] found that ethical leadership enhanced employees’ moral efficacy, which led to courageous displays of ethical behaviors. Moreover, Kim and Vandenberghe [

58] found that ethical leadership can have a positive impact on team ethical voice and OCB directed at the individual and the organization through team moral efficacy. In line with this, Owens et al. [

56] found that a leader’s moral humility can increase employees’ moral efficacy, thus increasing employees’ prosocial behaviors and reducing their unethical behaviors. These findings show that there is a broad consensus among scholars that moral efficacy can enhance individuals’ moral behaviors.

We suggest that SRHRM will have a positive impact on OCBE, as SRHRM improves employees’ moral efficacy. First, SRHRM practices link the recruitment, promotion, remuneration, and performance appraisal process with employees’ social contributions, providing generous rewards and work benefits to employees with strong social performance [

9]. By strengthening rewards, the organization encourages employees to behave ethically, which helps them gain more moral confidence and experience and thereby enhances their moral efficacy. Second, SRHRM provides employees with CSR-related systematic training programs, yielding opportunities to accumulate knowledge about and experience with fulfilling CSR roles [

9]. Such training, including business ethics education, can increase employees’ confidence in their ability to handle ethical problems in their work and can enhance their moral efficacy [

59]. Third, SRHRM conveys the message to employees that the organization attaches importance to external stakeholders, including the natural environment [

60]. Therefore, we expect that this practice will increase employees’ willingness to engage in OCBE, which is closely related to environmental protection and sustainable organizational development.

Felt Obligation: Felt obligation refers to “the prescriptive belief regarding whether one should care about the organization’s well-being and should help the organization reach its goals” [

61]. This definition includes two major components: The first is the belief that employees make business contributions and help to achieve organizational objectives, and the second is the belief that employees pay attention to and value the interests and welfare of the organization. Thus, felt obligation embodies the principle of reciprocity, which is a culturally universal social interaction principle [

62,

63].

Employees with strong felt obligation are more likely to believe that they owe the organization and to strive their best to help the organization achieve its goals [

63,

64]. When employees feel that the organization cares about them and demonstrates preferential treatment toward their interests, they may feel obligated to repay the organization and thus actively strive to improve their work [

61]. Stronger feelings of obligation entail more active work efforts by employees, as well as their taking initiative to advance organizational interests and strategic goals. Further, Yu and Frenkel [

65] found that perceived organizational support can enhance employees’ task performance and creativity through felt obligation. Based on job demands–resources (JD–R) theory, Albrecht and Su [

66] found that job resources can affect employees’ work engagement through felt obligation.

Felt obligation also encourages employees to go “above and beyond” job requirements, engaging in extra-role behaviors that are beneficial to the organization and overall public welfare [

61]. Felt obligation often influences employees to adopt constructive behaviors that will benefit others or other organizations and motivates employees to be “good citizens” who protect stakeholders [

67]. Eisenberger et al. [

61] found that perceived organizational support can enhance employees’ felt obligation, inducing them to care about organizational welfare and help their organizations achieve their goals; in turn, they found that this promotes employees’ affective commitment, spontaneity, and in-role performance.

SRHRM focuses on the interests of employees as important internal stakeholders and cares about their personal development needs and work-life balance [

10]. In accordance with social exchange theory and reciprocity norms, when an organization adopts HRM practices that benefit its employees, employees will feel obligated to give back to the organization and will continue to conduct reciprocal social exchange [

68]. Moreover, SRHRM clearly conveys to employees the significance of CSR for the organization and themselves, as well as the organization’s expectations that employees contribute to CSR initiatives [

9]. Such a clear responsibility-oriented value system will lead employees to believe that their work is not only for creating organizational benefits but also for benefiting society at large, thereby promoting employees’ felt obligation. Thus, we argue that SRHRM practice strengthens employees’ feelings of obligation to the organization.

Felt obligation may be an important psychological mechanism to explain the motivation behind employees’ OCBE initiatives. Han et al. [

19] empirically verified that felt obligation for constructive change, stimulated by responsible leadership, motivates employees to engage in OCBE. In fact, several scholars have explored the mediating role of perceived obligation in the relationship between leadership factors and employees’ work behavior. Tian and Li [

69] found that self-sacrificial leadership can promote employees’ proactive behavior indirectly through felt obligation. Additionally, Basit [

70] found that employees’ trust in their supervisors can enhance their feelings of obligation and further improve work engagement. Lorinkova and Perry [

71] found that group-focused transformational leadership is more likely to enhance working group members’ feelings of obligation, thereby motivating helping behaviors and enhancing group performance. Therefore, we reason that SRHRM practice will promote employees’ feelings of obligation to the organization and encourage them to engage in OCBE.

Empathy: Empathy refers to “the reaction of one individual to the observed experiences of another” [

72]. More specifically, empathy is conceptualized as “an individual difference that involves sharing other people’s feelings related to other people’s well-being” [

73], which comprises cognitive and emotional components [

74]. Cognitive empathy refers to “an individual’s ability to take the perspective of those in need,” while emotional empathy refers to “an other-oriented emotional response elicited by and congruent with the perceived welfare of someone in need” [

74]. Empathy is conceptually different from sympathy and compassion. Sympathy can be defined as “an emotional response stemming from the apprehension of another’s emotional state or condition, which is not the same as the other’s state or condition but consists of feelings of sorrow or concern for the other” [

61]. Hence managers may feel sympathetic toward outraged employees without feeling outraged themselves, while taking on these actual feelings is characteristic of empathy [

75]. Moreover, compassion is described as “a process involving both feeling and action” [

76], which we can distinguish from empathy by its action component.

As an other-oriented affective reaction, empathy can arouse an individual’s attention to others’ needs and generate motivation to act in ways that benefit others [

74]. Therefore, empathy has always been regarded as an important motivator of prosocial and altruistic behaviors [

77,

78]. Compared to employees with low empathy, who are insensitive to the needs of others, employees with high empathy are more likely to define OCB as an in-role behavior [

79]. They will make efforts to understand other people’s ideas and are more willing exhibit OCB. Supporting this assertion, Eisenberg et al. [

61] found that individuals with high empathy tend to engage in more prosocial behaviors. Batson et al. [

80] also found that empathy not only can construct a universal connection between oneself and others’ emotional experience and well-being but also can enhance helping and sharing behaviors. Shao et al. [

81] found that SRHRM can stimulate employees’ affective empathy. Moreover, Berenguer [

82] found that empathy can promote individuals’ pro-environment attitudes and behaviors.

Organizations’ SRHRM practices may trigger employees’ empathic reactions. Affective events theory posits that specific affective events in the workplace, such as praise, will trigger specific affective reactions in employees [

83]. First, SRHRM advocacy of social responsibility values may help employees pay attention to others’ needs and interests and consider the social impact of their work behaviors on external stakeholders, thus generating empathy [

81]. Additionally, as mentioned previously, SRHRM practice rewards employees for good social performance [

9]. In this way, CSR activities can meet several psychological needs and practical interests of employees such that employees will be motivated to respond positively to SRHRM practice and show more empathy [

81]. Based on this, we infer that employees will accept and support the caring values advocated by SRHRM practice, enabling them to empathize with those in need.

Considering that the social responsibility values transmitted to employees by SRHRM emphasize the environment as an important stakeholder, empathy can facilitate environmentally friendly attitudes and behaviors. We therefore infer that employees with empathy aroused by SRHRM practices will be more likely to fully consider the environmental impact of their behaviors and therefore will engage in OCBE, which is conducive to environmental protection. Based on this reasoning, we propose the following hypotheses:

Hypothesis 2. Moral efficacy will partially mediate the positive relationship between SRHRM and OCBE.

Hypothesis 3. Felt obligation will partially mediate the positive relationship between SRHRM and OCBE.

Hypothesis 4. Empathy will partially mediate the positive relationship between SRHRM and OCBE.

Figure 1 summarizes the hypotheses tested in this study.