Land to the Tiller: The Sustainability of Family Farms

Abstract

:1. Introduction: The Agrarian Question

“Introducing the UN Decade of Family Farming: The UN Decade of Family Farming 2019–2028 aims to shed new light on what it means to be a family farmer in a rapidly changing world and highlights more than ever before the important role they play in eradicating hunger and shaping our future of food. Family farming offers a unique opportunity to ensure food security, improve livelihoods, better manage natural resources, protect the environment and achieve sustainable development, particularly in rural areas. Thanks to their wisdom and care for the earth, family farmers are the agents of change we need to achieve Zero Hunger, a more balanced and resilient planet, and the Sustainable Development Goals.” (http://www.fao.org/family-farming-decade/home/en/ (accessed on 12 October 2021))

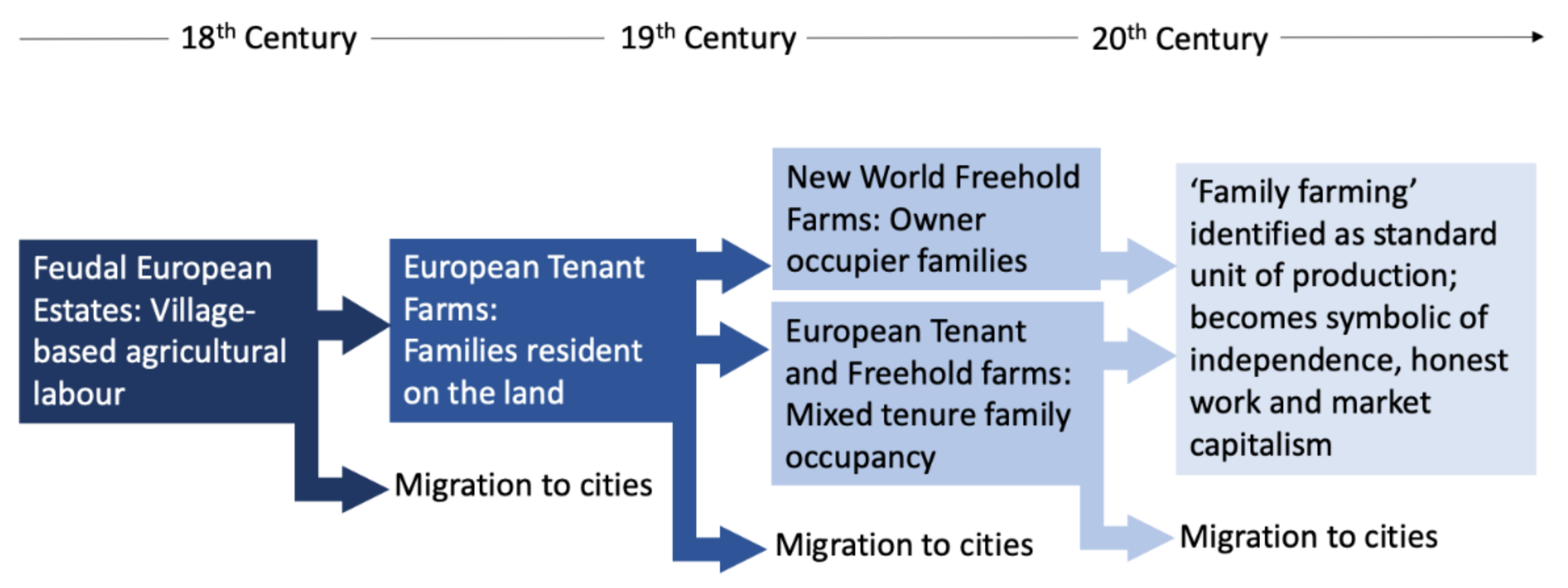

2. The Standard Western Version of Family Farming

“Cutting and clearing forest land, the logging connected with this land improvement, making pails or tubs for the house, repairing tools or making new ones, dressing the flax for spinning, making linen for bags as well as for the house, making boots, mittens and harnesses from the hides that they had tanned on shares, splitting and making shingles for the roof, making cane furniture, melting pewter and making spoons, with moulds, shoeing horses, leaching ashes and boiling lye to make potash for sale, labouring on public roads as required by statute, slaughtering meat for the household, transporting products to market and hauling in all building supplies, splitting rails for fences, and digging the well”.[7]

3. Theorizing the Family Farm

4. Contemporary Issues

5. Introducing the Case Studies

5.1. Family Farming in Scotland

“a small agricultural unit, most of which are situated in the crofting counties in the north of Scotland being the former counties of Argyll, Caithness, Inverness, Ross & Cromarty, Sutherland, Orkney and Shetland, and held subject to the provisions of the Crofting Acts”.[81]

5.2. Family Farming in Brazil

- land area of up to four fiscal modules (which measure in hectares varies from region to region);

- predominant use of family labour;

- a minimum percentage of family income originating from on-farm activities;

- management of the establishment by the family.

5.3. Family Farming in China

6. Discussion

7. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

Key Terms

References

- FAO; IFAD. United Nations Decade of Family Farming 2019–2028. Global Action Plan; Licence: CC BY-NC-SA 3.0 IGO; FAO: Rome, Italy, 2019; p. 8. [Google Scholar]

- Gasson, R.; Errington, A.J. The Farm Family Business; Cab International: Wallingford, UK, 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Buttel, F.H.; LaRamee, P. The “disappearing Middle”: A sociological perspective (No. 2074-2018-1722). In Proceedings of the Annual Meeting of the Rural Sociological Society, Madison, WI, USA, 12–15 August 1987. [Google Scholar]

- Newby, H. The Countryside in Question; Hutchinson Education: Hutchinson, KS, USA, 1988. [Google Scholar]

- Van der Ploeg, J.D. From de-to repeasantization: The modernization of agriculture revisited. J. Rural. Stud. 2018, 61, 236–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Milone, P.; Ventura, F.; Ye, J. (Eds.) Constructing a New Framework for Rural Development; Emerald Group Publishing: Bingley, UK, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Wietfeldt, R. Attitudes of Farmers’ Unions to Part-Time Farming. In Part Time Farming: Problem or Resource in Rural Development; Fuller, A.M., Mage, J., Eds.; Geo Abstracts: Norwich, UK, 1976; pp. 207–212. [Google Scholar]

- Friedmann, H. World market, state, and family farm: Social bases of household production in the era of wage labor. Comp. Stud. Soc. Hist. 1978, 20, 545–586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nory, H. The Role of Agribusiness and Extension. In Farming and the Rural Community in Ontario, an Introduction; Fuller, T., Ed.; University of Toronto: Toronto, ON, Canada, 1984; pp. 77–99. [Google Scholar]

- Rogers, E.M. Diffusion of Innovations; Simon and Schuster: New York, NY, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Reid, I. (Ed.) The Future of the Family Farm in Europe; Centre for European Agricultural Studies, Wye College: Kent, UK, 1974. [Google Scholar]

- Mariola, M.J. Losing ground: Farmland preservation, economic utilitarianism, and the erosion of the agrarian ideal. Agric. Hum. Values 2005, 22, 209–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flinn, W.L.; Johnson, D.E. Agrarianism among Wisconsin farmers. Rural. Sociol. 1974, 39, 187. [Google Scholar]

- Zioganas, C.M. Defining and determining a ‘fair’ standard of living for the farm family. Eur. Rev. Agric. Econ. 1988, 15, 55–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pahl, R.E. Divisions of Labour; Blackwell: Oxford, UK, 1984. [Google Scholar]

- Keating, N.C.; Munro, B. Transferring the family farm: Process and implications. Fam. Relat. 1989, 38, 215–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tracy, M.A. Fifty years of agricultural policy. J. Agric. Econ. 1976, 27, 331–350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hobsbawm, E.J. Primitive Rebels: Studies in Archaic Forms of Social Movement in the 19th and 20th Centuries; Manchester University Press: Manchester, UK, 1959. [Google Scholar]

- Thompson, F.M.L. English Landed Society in the Nineteenth Century; Routledge: Oxfordshire, UK, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- King, R. Land Reform: The Italian Experience; Butterworths: London, UK, 1973; pp. 5–9. [Google Scholar]

- Helmore, K.; Singh, N. Sustainable Livelihoods: Building the Wealth of the Poor; Kumarian: Boulder, CO, USA, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Scoones, I. Sustainable Rural Livelihoods: A Framework for Analysis; IDS Working Paper #72; Institute for Development Studies: Brighton, UK, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Ellis, F. Household strategies and rural livelihood diversification. J. Dev. Stud. 1998, 35, 1–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benvenuti, B. Farming in Cultural Change; Van Gorcum Enlo: Assen, The Netherlands, 1962. [Google Scholar]

- Chayanov, A. The Theory of Peasant Co-Operatives; The Ohio State University Press: Columbus, OH, USA, 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Goode, P. Karl Kautsky: Selected Political Writings; Macmillan: London, UK, 1983. [Google Scholar]

- Littlejohn, G. Peasant economy and society. In Sociological Theories of the Economy; Hindess, B., Ed.; Palgrave Macmillan: London, UK, 1977; pp. 118–156. [Google Scholar]

- Friedmann, H.; McMichael, P. Agriculture and the state system: The rise and decline of national agricultures, 1870 to the present. Sociol. Rural. 1989, 29, 93–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mann, S.A.; Dickinson, J.M. Obstacles to the development of a capitalist agriculture. J. Peasant Stud. 1978, 5, 466–481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ehrensaft, P.; LaRamee, P.; Bollman, R.D.; Buttel, F.H. The microdynamics of farm structural change in North America: The Canadian experience and Canada-USA comparisons. Am. J. Agric. Econ. 1984, 66, 823–828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vogler, I. The Myth of the Family Farm; Westview Press: Boulder, CO, USA, 1981. [Google Scholar]

- Comstock, G. (Ed.) Is There a Moral Obligation to Save the Family Farm? Iowa University Press: Iowa City, IA, USA, 1987. [Google Scholar]

- Strange, M. Family Farming: A New Economic Vision; University of Nebraska Press: Lincoln, NE, USA, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Carlisle, L. Critical agrarianism. Renew. Agric. Food Syst. 2014, 29, 135–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Halfacree, K. Radical spaces of rural gentrification. Plan. Theory Pract. 2011, 12, 618–625. [Google Scholar]

- Beus, C.E.; Dunlap, R.E. Endorsement of Agrarian Ideology and Adherence to Agricultural Paradigms 1. Rural Sociol. 1994, 59, 462–484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baker, J.R.; Lobley, M.; Whitehead, I. (Eds.) Keeping It in the Family: International Perspectives on Succession and Retirement on Family Farms; Routledge: Oxfordshire, UK, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Gorton, M.; Douarin, E.; Davidova, S.; Latruffe, L. Attitudes to agricultural policy and farming futures in the context of the 2003 CAP reform: A comparison of farmers in selected established and new Member States. J. Rural Stud. 2008, 24, 322–336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alston, M. Who is down on the farm? Social aspects of Australian agriculture in the 21st century. Agric. Hum. Values 2004, 21, 37–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burton, R.J. Seeing through the ‘good farmer’s’ eyes: Towards developing an understanding of the social symbolic value of ‘productivist’behaviour. Sociol. Rural. 2004, 44, 195–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sutherland, L.A. Can organic farmers be ‘good farmers’? Adding the ‘taste of necessity’to the conventionalization debate. Agric. Hum. Values 2013, 30, 429–441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riley, M. Still being the ‘good farmer’:(non-) retirement and the preservation of farming identities in older age. Sociol. Rural. 2016, 56, 96–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sorice, M.G.; Kreuter, U.P.; Wilcox, B.P.; Fox, W.E., III. Classifying land-ownership motivations in central, Texas, USA: A first step in understanding drivers of large-scale land cover change. J. Arid Environ. 2012, 80, 56–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sutherland, L.A.; Barlagne, C.; Barnes, A.P. Beyond ‘Hobby Farming’: Towards a typology of non-commercial farming. Agric. Hum. Values 2019, 36, 475–493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Peeren, E.; Souch, I. Romance in the cowshed: Challenging and reaffirming the rural idyll in the Dutch reality TV show Farmer Wants a Wife. J. Rural Stud. 2019, 67, 37–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sutherland, L.A. The ‘desk-chair countryside’: Affect, authenticity and the rural idyll in a farming computer game. J. Rural Stud. 2020, 78, 350–363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sutherland, L.A. Virtualizing the ‘good life’: Reworking narratives of agrarianism and the rural idyll in a computer game. Agric. Hum. Values 2020, 37, 1155–1173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bowler, I.; Clark, G.; Crockett, A.; Ilbery, B.; Shaw, A. The development of alternative farm enterprises: A study of family labour farms in the Northern Pennines of England. J. Rural Stud. 1996, 12, 285–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garforth, C.; Rehman, T. Research to Understand and Model the Behaviour and Motivations of Farmers in Responding to Policy Changes (England); Department for Environment, Food and Rural Affairs (DEFRA): London, UK, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Marsden, T.; Munton, R.; Ward, N. Incorporating social trajectories into uneven agrarian development: Farm businesses in upland and lowland Britain. Sociol. Rural. 1992, 32, 408–430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shucksmith, M.; Herrmann, V. Future changes in British agriculture: Projecting divergent farm household behaviour. J. Agric. Econ. 2002, 53, 37–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buttel, F.H. Some reflections on late twentieth century agrarian political economy. Sociol. Rural. 2001, 41, 165–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marsden, T.K.; Murdoch, J.; Lowe, P.; Ward, N. The Differentiated Countryside; Routledge: Oxfordshire, UK, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Lowe, P.; Murdoch, J.; Marsden, T.; Munton, R.; Flynn, A. Regulating the new rural spaces: The uneven development of land. J. Rural Stud. 1993, 9, 205–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hallberg, M.; Findeis, J.; Lass, D. Multiple Job Holding Among Farm Families; Iowa Stae University Press: Ames, IA, USA, 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Fuller, A.M. From part-time farming to pluriactivity: A decade of change in rural Europe. J. Rural Stud. 1990, 6, 361–373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bryden, J.; Fuller, T. Pluriactivity: A Rural Development Option; Arkleton Trust: Streatley, UK, 1988. [Google Scholar]

- Brun, A.; Fuller, A.M. Farm Family Pluriactivity in Western Europe; Arkleton Trust (Research) Ltd.: Streatley, UK, 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Evans, N.; Morris, C.; Winter, M. Conceptualizing agriculture: A critique of post-productivism as the new orthodoxy. Prog. Hum. Geogr. 2002, 26, 313–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Wilson, G.A. From productivism to post-productivism… and back again? Exploring the (un) changed natural and mental landscapes of European agriculture. Trans. Inst. Br. Geogr. 2001, 26, 77–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walford, N. Productivism is allegedly dead, long live productivism. Evidence of continued productivist attitudes and decision-making in South-East England. J. Rural Stud. 2003, 19, 491–502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burton, R.J.; Wilson, G.A. Injecting social psychology theory into conceptualisations of agricultural agency: Towards a post-productivist farmer self-identity? J. Rural Stud. 2006, 22, 95–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marsden, T.; Sonnino, R. Rural development and the regional state: Denying multifunctional agriculture in the UK. J. Rural Stud. 2008, 24, 422–431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fuller, A.M. From Part-Time Farming to Multifunctionality: Reflections of a Social Geographer. In The Methodology of Political Economy: Studying the Global Rural-Urban Matrix; Bakker, J.I., Ed.; Lexington Books/Rowman and Littlefield Publishing Group Inc.: Lanham, MD, USA, 2015; pp. 113–128. [Google Scholar]

- Symes, D.G. Bridging the generations: Succession and inheritance in a changing world. Sociol. Rural. 1990, 30, 280–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zagata, L.; Hrabak, J.; Lošťak, M.; Bavorová, M.; Ratinger, T.; Sutherland, L.A.; McKee, A. Research for AGRI Committee–Young Farmers–Policy Implementation after the 2013 CAP Reform; European Parliament, Policy Department for Structural and Cohesion Policies: Brussels, Belgium, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Calo, A.; De Master, K.T. After the incubator: Factors impeding land access along the path from farmworker to proprietor. J. Agric. Food Syst. Community Dev. 2016, 6, 111–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rico, N.M.; Fuller, A.M. Newcomers to farming: Towards a new rurality in Europe. Documents D’anàlisi Geogràfica 2016, 62, 531–551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Bell, S.E.; Hullinger, A.; Brislen, L. Manipulated Masculinities: Agribusiness, Deskilling, and the Rise of the Businessman-Farmer in the United States. Rural Sociol. 2015, 80, 285–313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woods, M. Family farming in the global countryside. Anthropol. Noteb. 2014, 20, 31–48. [Google Scholar]

- Johnsen, S. The redefinition of family farming: Agricultural restructuring and farm adjustment in Waihemo, New Zealand. J. Rural Stud. 2004, 20, 419–432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moran, W.; Blunden, G.; Greenwood, J. The role of family farming in agrarian change. Prog. Hum. Geogr. 1993, 17, 22–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Misachi, J. The Scottish Agricultural Revolution and The Lowland and Highlands Clearances. The World Atlas. Available online: https://www.worldatlas.com/articles/the-scottish-agricultural-revolution-and-the-lowland-and-highlands-clearances.html (accessed on 12 October 2021).

- Stewart, T. The Highland Clearances. Historic UK. Un-Dated. Available online: https://www.historic-uk.com/HistoryUK/HistoryofScotland/The-Highland-Clearances/ (accessed on 12 October 2021).

- James of Glencar. The Highland Clearances. How a Whole People Were Dispossessed and Scattered Clan James Un-Dated. Available online: http://clanjames.com/clearances.htm (accessed on 12 October 2021).

- Newby, H. Green and Pleasant Land? Social Change in Rural England; Penguin Books Ltd.: London, UK, 1979. [Google Scholar]

- Clemenson, H.A. English Country Houses and Landed Estates; Croom Helm: London, UK, 1982. [Google Scholar]

- Phillips, M. Differential productions of rural gentrification: Illustrations from North and South Norfolk. Geoforum 2005, 36, 477–494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crofting Commission. Crofting Commission Plan—Now It’s Down to You. Available online: www.crofting.scotland.gov.uk/news.asp (accessed on 5 September 2012).

- Scottish Crofting Federation. About Crofting. Available online: https://www.crofting.org/about-scf/about-crofting/ (accessed on 12 October 2021).

- Shucksmith, M.; Rønningen, L. The Uplands after neoliberalism? The role of the small farm in rural sustainability. J. Rural Stud. 2011, 27, 275–287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Black, C.; Martin, C.; Warren, R.; Mori, I. Survey of the Economic Conditions of Crofting 2015–2018; Scottish Government: Edinburgh, UK, 2018.

- We Love Stornoway. Croft Union Praises Words of Minister. Croft Union Praises Words of Minister. 7 October 2021. Available online: welovestornoway.com (accessed on 12 October 2021).

- Zagata, L.; Sutherland, L.A. Deconstructing the ‘young farmer problem in Europe’: Towards a research agenda. J. Rural Stud. 2015, 38, 39–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davidova, S.; Bailey, A.; Dwyer, J.; Erjavec, E.; Gorton, M.; Thomson, K. Semi-Subsistence Farming-Value and Directions of Development; European Parliament, Directorate-General for Internal Policies Policy Department B Structural and Cohesion Policies: Brussels, Belgium, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Sutherland, L.-A.; Calo, A. Assemblage and the ‘good farmer’: New entrants to crofting in Scotland. J. Rural Stud. 2020, 80, 532–542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martins, J.S. Os Camponeses e a Política No Brasil. As Lutas Sociais No Campo e Seu Lugar No Processo Político; Vozes: Petrópolis, Brazil, 1981. [Google Scholar]

- Wanderley, M.N.B. O Mundo Rural Como um Espaço de Vida. Reflexões Sobre a Propriedade da Terra, Agricultura Familiar e Ruralidade; UFRGS: Porto Alegre, Brazil, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Schneider, S. Situando o desenvolvimento rural no Brasil: O contexto e as questões em debate. Rev. De Econ. Política 2010, 30, 511–531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Picolotto, E.L. Os atores da construção da categoria agricultura familiar no Brasil. Rev. De Econ. E Sociol. Rural 2014, 52, 63–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Veiga, J.E. Desenvolvimento Agrícola: Uma Visão Histórica; Hucitec: São Paulo, Brazil, 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Abramovay, R. Paradigmas do Capitalismo Agrário em Questão; Hucitec: São Paulo, Brazil, 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Lamarche, H. A Agricultura Familiar I: Uma Realidade Multiforme; Unicamp: Campinas, Brazil, 1993. [Google Scholar]

- FAO/INCRA; Instituto Nacional de Colonização e Reforma Agrária do Brasil. Diretrizes de Política Agrária e Desenvolvimento Sustentável. Resumo do Relatório Final do Projeto UTF/BRA/036, 2. Versão; FAO/INCRA: Brasília, Brazil, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- IBGE (Instituto Brasileiro de Geografia e Estatística). Censo Agropecuário. Available online: https://www.ibge.gov.br/estatisticas/economicas/agricultura-e-pecuaria/21814-2017-censo-agropecuario.html?=&t=o-que-e (accessed on 28 September 2021).

- Del Grossi, M.; Florido, A.C.S.; Rodrigues, L.F.P.; Oliveira, M.S. Comunicação de pesquisa: Identificando a agricultura familiar nos Censos Agropecuários brasileiros. Rev. NECAT 2019, 8, 40–45. [Google Scholar]

- Escher, F. Class dynamics of rural transformation in Brazil: A critical assessment of the current agrarian debate. Agrar. South 2020, 9, 144–170. [Google Scholar]

- Niederle, P.; Grisa, C.; Picolotto, E.L.; Soldera, D. Narrative disputes over family-farming public policies in Brazil: Conservative attacks and restricted countermovements. Lat. Am. Res. Rev. 2019, 54, 707–720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Gramsci, A. Selections from the Prison Notebooks; International Publishers: New York, NY, USA, 1971. [Google Scholar]

- Mao, Z. Report from Xunwu (Xunwu Diaocha). 1930. Available online: http://www.dangjian.cn/specials/xwdc/mzdzxw/201507/t20150709_2720620.shtml (accessed on 28 September 2021).

- Wang, J. Village Collective Economy: Historical Transitions and Temporary Developments; China Social Sciences Press: Beijing, China, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Jin, B. Chinese Agriculture and the Long-Term Sustainable Development of Chinese Peasants. 2007. Available online: https://critiqueandtransformation.wordpress.com/2007/02/02/%E4%B8%AD%E5%9C%8B%E8%BE%B2%E6%A5%AD%E8%88%87%E4%B8%AD%E5%9C%8B%E8%BE%B2%E6%B0%91%E2%94%80%E2%94%80%E9%95%B7%E6%9C%9F%E5%8F%AF%E6%8C%81%E7%BA%8C%E7%99%BC%E5%B1%95%E4%B9%8B%E7%A0%94%E7%A9%B6%EF%BC%88/ (accessed on 12 October 2021).

- Yan, H.; Ku, H.; Xu, S. Rural revitalization, scholars, and the dynamics of the collective future in China. J. Peasant Stud. 2021, 48, 853–874. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, S. Strong village leadership vs. Government investment: Reflections on a community reconstruction case in southwest China. China Perspect. 2021, 2, 39–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, S.; Fuller, T. Land transfer and the political sociology of community: The case of a Chinese village. J. Rural Community Dev. 2018, 13, 38–56. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Q.F.; Donaldson, J.A. The rise of agrarian capitalism with Chinese characteristics: Agricultural modernization, agribusiness and collective land rights. China J. 2008, 60, 25–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, H.; Chen, Y. Agrarian Capitalization without Capitalism? Capitalist Dynamics from Above and Below in China. J. Agrar. Chang. 2015, 15, 366–391. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Q.F. Class Differentiation in Rural China: Dynamics of Accumulation, Commodification and State Intervention. J. Agrar. Chang. 2015, 15, 338–365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Y. Can Capitalist Farms Defeat Family Farms? The Dynamics of Capitalist Accumulation in Shrimp Aquaculture in South China. J. Agrar. Chang. 2015, 15, 392–412. [Google Scholar]

- News China. 600,000 Family Farms Were Catalogued in China (Zhongguo Jinru Minglu De Jiating Nongchang Da Liushi Wan Jia). 2019. Available online: http://news.china.com.cn/live/2019-09/18/content_547513.htm (accessed on 28 September 2021).

- MARA. Notice on the Release of “2020–2022 Plan for the High-Quality Development of New Agricultural Operation and Service Subjects” from Ministry of Agriculture and Rural Affairs (Nongye Nongcun Bu Guanyu Yinfa Xinxing Nongye Jingying Zhuti He Fuwu Zhuti Gaozhiliang Fazhan Guihua, 2020–2022). 2020. Available online: http://www.moa.gov.cn/nybgb/2020/202003/202004/t20200423_6342187.htm (accessed on 28 September 2021).

- MARA. Instructions of Ministry of Agriculture on the Development of Family Farms (Nongye Bu Guanyu Cujin Jiating Nongchang Fazhan De Zhidao Yijian). 2014. Available online: http://www.moa.gov.cn/gk/zcfg/nybgz/201403/t20140311_3809883.htm (accessed on 28 September 2021).

- Franklin, S.H. The European Peasantry: The Final Phase; Methuen: London, UK, 1969. [Google Scholar]

- Bunce, M. Reproducing Rural Idylls. In Country Visions; Cloke, P., Ed.; Pearson Education Ltd.: Harlow, UK, 2003; pp. 14–30. [Google Scholar]

- Horton, J. Producing Postman Pat: The popular cultural construction of idyllic rurality. J. Rural Studies. 2008, 24, 389–398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Friedmann, H. Household production and the national economy: Concepts for the analysis of agrarian formations. J. Peasant. Stud. 1980, 7, 158–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Scotland | Brazil | China | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Historical development of ‘family farming’ | Crofting legally protected in 1886; new owner operator farms post-1918. ‘Family farming’ on tenanted and owner-occupied land informally recognised as the common form of agricultural land management. | Diverse social groups with colonial origins, new European immigrants at the end of the 19th century, social and institutional recognition at the end of the 20th century. | Since the foundation of the PRC, there are individual household farming, collective farming and then gradual agricultural capitalization that emerged as family farming. |

| Major types of agricultural holdings in 2021 | All agricultural holdings are considered ‘farms’. Land on estates, farms, crofts and small holdings may be owner or tenant occupied. | Employer agriculture (capitalist enterprises and unproductive latifundia) and family farms (entrepreneurial, commercial and peasant). | Small household farms, family farms, farmers’ cooperatives, large-scale capitalist farms. |

| Recent role of the state | Legal protections on crofting increased in 1976 (Crofting Reform Act), 2003 (Land Reform Scotland Act), 2007 (Crofting Reform Act), 2010 (Crofting Reform Act) and 2013 (Amendment to the 2010 Crofting Reform Act). Subsidies to agricultural holdings were provided through Europe’s Common Agricultural Policy (1973–2020) and have continued in Scotland post-Brexit with limited change. | National Program for Strengthening Family Farming (1996), Ministry of Agrarian Development (created in 1999, extinct in 2016), National Policy on Family Farming and Rural Family Enterprises (law created in 2006, modified in 2017), ongoing process of policy dismantling. | The term family farming was imported and officially defined by the state of China in 2013 in support for agricultural industrialization and capitalization. The state provides family farms with subsidies and infrastructure projects. |

| Imaginary of family farming | Family farming is recognised as the basic unit of agricultural production and important for rural economic development. Crofts in particular are recognised as important for ‘keeping the lights on’ in rural areas. | Recognition and promotion of family farming as a central social and normative category for rural development in Brazil. Fierce narrative disputes, marked by systematic conservative attacks over the meaning of family farming and the public policies targeted at the segment. | Family farms are an upgraded version of household farms. In fact, they are commercial farms emerging from agricultural capitalism that can potentially differentiate into capitalist farms. |

| Sustainability | Recent EU subsidies have emphasised increasing the environmental sustainability of farming. Upland farms and crofts are considered to be more environmentally and socially sustainable because the land is not suited to intensive production. Most farms and crofts in Scotland would not be profitable without subsidies. | It is assumed that family farming is inherently sustainable and more respectful of nature than the agribusiness model. However, only a minority practice ‘agro-ecology’ and a substantial portion continues to pursue intensification (the ‘green revolution’ model). Significant economic relevance. | The officially defined family farm in China largely conforms to agribusiness. They contribute to rural–urban migration of agricultural labourers, environmental and ecological costs and require community re-construction. |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Fuller, A.M.; Xu, S.; Sutherland, L.-A.; Escher, F. Land to the Tiller: The Sustainability of Family Farms. Sustainability 2021, 13, 11452. https://doi.org/10.3390/su132011452

Fuller AM, Xu S, Sutherland L-A, Escher F. Land to the Tiller: The Sustainability of Family Farms. Sustainability. 2021; 13(20):11452. https://doi.org/10.3390/su132011452

Chicago/Turabian StyleFuller, Anthony M., Siyuan Xu, Lee-Ann Sutherland, and Fabiano Escher. 2021. "Land to the Tiller: The Sustainability of Family Farms" Sustainability 13, no. 20: 11452. https://doi.org/10.3390/su132011452

APA StyleFuller, A. M., Xu, S., Sutherland, L.-A., & Escher, F. (2021). Land to the Tiller: The Sustainability of Family Farms. Sustainability, 13(20), 11452. https://doi.org/10.3390/su132011452