1. Introduction

The complexity of monetary policy transmission mechanisms (MPTMs) has drawn a lot of attention from economists and policymakers over the past two decades for better understanding of how monetary policy affects the real economy. Due to persistent monetary and financial developments, the identification of different channels by which the money supply diffuses its impact on the real economy, including GDP and inflation, remains elusive [

1]. Furthermore, central banks’ interest rate decisions are often based on some implicit and explicit interpretation of MPTMs [

2]. Even though MPTMs vary by region, previous studies have identified six channels: credit channel (CC), asset price channel (APC), exchange rate channel (ERC), interest rate channel (IRC), bank lending channel (BLC), and balance sheet channel (BSC) [

3]. According to [

3,

4,

5,

6] BLC and BSC are collectively given the name of credit channel (CC).

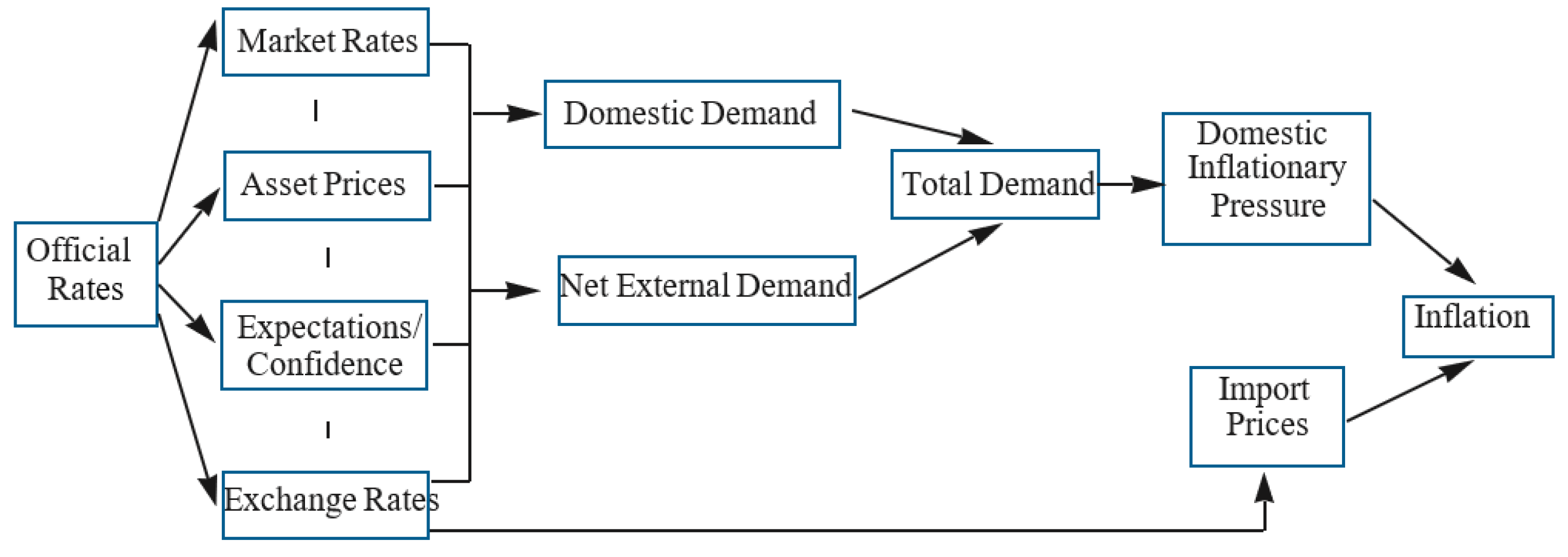

Figure 1 shows a general framework for MPTM given by the European monetary bank (EMB).

Although the majority of these channels exist in advanced countries, there are only a few that operate in developing countries. The competitive benefits of these channels differ from country to country and are based on the level of capital markets and economic growth.

With the signing of a charter in 1985 [

7], the South Asian Association for Regional Cooperation (SAARC) was established. It is made up of eight countries. The SAARC’s primary goal is to boost the region’s economic growth and social well-being. It also intends to stimulate active collaboration in the disciplines of economics, social science, and technology. To attain these goals, some researchers have urged more monetary and exchange-rate policy cooperation than in the past. For instance, Banik and Biswas [

8] suggested developing a customs union that comprised South Asian countries by 2015 with subsequent unification of the economies of the South Asian nations by 2020. Similarly, reference [

9] placed more emphasis on the financial and economic integration of SAARC member states. Moreover, the optimal currency area theory explains that geographical regions should maximize their economic efficiency by creating economic unions and sharing a single currency. We argue that the creation of SAARC Finance in 1998 to form an economic union was a positive move forward. This platform contributes to a closer integration of economic and financial systems, which is a prerequisite for the creation of an economic union [

9]. Despite the importance of economic integration, studies on the role of monetary and exchange-rate policy in transforming the SAARC into a monetary and economic union are scarce. Therefore, the lack of knowledge about the ways that monetary and exchange rate policy influences the real sector in SAARC economies motivates us to explore the related financial and macroeconomic variables.

Previous studies have reported that macroeconomic factors such as national income, fiscal policy instruments, domestic demand consumption, foreign direct investment, inflow of remittances, and energy consumption are related to environmental pollution [

10]. However, studies in the past overlooked the need to examine the relationships between monetary policy transmission mechanism and sustainable development of the SAARC countries [

11]. We argue that in addition to regulating inflation and preserving long-term interest rates, central banks are responsible for the development of monetary policy to govern and manage money supply in a country. Improved monetary policy and exchange rate regimes could provide more efficient economies better able to address environmental issues and population control [

10,

11]. For instance, in case of higher interest rate for innovative technologies, individuals may use traditional methods of production. Increased use of less environmentally friendly technologies might result in high levels of carbon emissions. SAARC countries are relying on monetary policy to promote innovation, foreign direct investment, and financial development. Therefore, it is imperative to investigate the impact of MPTM on the sustainable development of SAARC countries.

The objective of this study is to add to the extant knowledge base by identifying the common monetary channels prevailing among SAARC countries that may serve as a base for the possibility of creating a monetary and economic union. More specifically, this study contributes to the existing body of knowledge by using optimal currency area theory, this study explores the types of MPTMs in the SAARC countries. It also looks at the commonalities of different MPTMs in order to build monetary and economic unity, and helps us better comprehend the relationships between these factors.

2. Literature Review

Previous studies that evaluate the role of MPTMs in the formation of the economic union have documented the importance of monetary channels [

12]. For instance, monetarists claim that monetary policy is specifically related to price levels through the wealth channel, while Keynesians believe that monetary policy transmission is achieved indirectly through the interest rate channel [

12]. Moreover, through MPTMs, monetary policy affects economic output in general and inflation in particular in a two-stage process [

13]. A change in the policy rate influences the credit rate, the interest rate, the exchange rate, and the asset prices in the first step. In the second stage, these shifts affect the public’s spending and saving activities, resulting in a shift in demand and, eventually, inflation. According to [

14], an explanation of the mechanisms of monetary policy is important because of the influence that policy changes have on the economy.

The studies in the past have also confirmed the transmission of the policy rate changes by the central bank to the deposit rates and the loan rates [

15]. For example, in Croatia, the interest rate channel is a critical component of the transmission mechanism of monetary policy [

16], while the interest rate and the exchange rate channels are also present in the East African countries [

17]. Furthermore, some previous studies found that fluctuations in Kenya’s monetary policy affected real output across the interest rate channel [

18], while others observed that interest rates flowed from the money market to commercial banks in EU countries [

19].

Since the seminal work on the credit channel of MPTMs, researchers [

20] have suggested that the conventional channel of the interest rate is insufficient to account for the monetary policy’s effects on the real economy. As such, the monetary policy transmission to the non-monetary sector of the economy depends largely on how banks adapt their lending activities in response to the policy changes in terms of credit and exchange rates by the central bank [

21]. Moreover, the importance of this channel varies by country, depending on the existence of borrowers and financial markets [

22]. A comprehensive review of literature manifested the effectiveness of the credit channel and the exchange rate channel in the eurozone and the USA [

23], European Union [

21], and Finland [

24].

According to [

14] the exchange rate channel transmits the monetary policy to the real economy through its influence on the domestic currency value. An increase in policy rates makes savings and deposits in the domestic currency more lucrative, and it spurs more inflow of money into the domestic currency, which leads to its appreciation [

14]. Consequently, the aggregate output and net exports decrease. The sensitivity of the channel of the exchange rate depends on the openness of an economy and the floating exchange rates which affect the economic value of the goods and services of countries. During the period of establishment of the European Monetary Union, the exchange rate channel became more important [

25]. For instance, some studies have documented that the channel of the exchange rate is effective and operational [

26]. Others found that the exchange rate channel has long-lasting consequences, and the interest rate channel has short-term effects on inflation [

27]. Similarly, [

28] found that the changes in the interest rate have less significant effects on output, and substantial effects on inflation and the nominal exchange rate. Furthermore, [

17] observed that the exchange rate channel is more prominent in countries with imperfect financial markets.

Some studies in the past have also investigated and examined the transmission mechanism of Indian and Pakistani monetary policy. For example, reference [

29] argues that as monetary policy tightens, the credit rate rises at first, and banks play a key role in transferring monetary policy shocks to the real economy. Similarly, reference [

7] examined the causal relationship between Pakistani exports to the SAARC and the GDP, which included economic growth, and found a significant link between Pakistani exports to the SAARC and Pakistan’s GDP. These findings confirm the export-led growth hypothesis and the theory of customs unions at the regional level. These results also indicate that regulators in developing countries should place more emphasis on improving economic growth to obtain the real and the long-term benefits of regional trade agreements (RTAs), stabilize their prices, and reduce unemployment in their regions.

Based on previous studies it may be concluded that countries having similar monetary policy transmission channels may have the potential to create an economic union. However, there is a lack of understanding as to how MPTMs may lead to economic union. Therefore, the prevalent and significant research gaps require us to conduct this study on SAARC countries in order to know the common monetary channels that may serve as a base for moving towards an economic union among member countries.

3. The Model and Data Description

The current study used annual data of the macroeconomic variables, such as reserves, deposits, private sector credit, exchange rates, inflation, and the GDP for the SAARC countries for 40 years (1978–2017), which were obtained from International Financial Statistics (IFS) through the state bank of Pakistan (SBP). There are eight SAARC member countries which include Afghanistan, Bangladesh, Bhutan, India, Nepal, Pakistan, Sri Lanka, and The Maldives. Afghanistan’s data is not available, which is why seven member countries are included in this study. The reason for selecting this time horizon of the study is the availability of a common maximum data set for all member countries. This study measured inflation by the CPI, but this study employed a GDP deflator as a proxy for inflation for Bangladesh because of the unavailability of CPI data for Bangladesh. The use of the different proxies for Bangladesh did not affect our results [

30]. The variables included in this study are shown in

Table 1.

This study employed vector auto regressions (VARs) to analyze the relative significance of the channels of the monetary policy for the SAARC countries. For this purpose, we followed [

31,

32] to study monetary policy transmission. The basic model calculates the overall monetary policy impact on both the GDP (output) and the CPI (price). The general model of the VECM for the GDP of this study is as follows.

Equation (1).

where Δ

G = change in GDP,

ECT = Error correction term, Δ

R = change in reserves, Δ

D = change in deposits, Δ

C = change in credits, Δ

E = change in exchange rate, Δ

I = change in inflation and

is the error term.

The results from the VAR reveal the interrelationships between the key financial variables, which include the credits and the deposits, the monetary variables, which include the exchange rates and the reserves, and the macroeconomic variables, which include the GDP and inflation. Each country’s VAR generates six models with a 1-year lag. To analyze the short-term dynamics of the variables, this study employed the generalized variance decomposition function. The ordering of the variables is a matter of concern when dealing with the VARs. For this study, the ordering of the VARs is as follows: reserves, deposits, credits, exchange rates, inflation, and the GDP. This study employs the impulse response function and the variance decomposition to interpret the results of the VARs.

4. Results and Discussion

This study examines the role of MPTMs in the sustainable development of the SAARC economic community by employing optimal currency area theory. We tested the stationarity of the data by using the augmented Dickey–Fuller (ADF) test. The analysis revealed that the data of all the variables became integrated at first level difference or order 1 with a constant and a linear trend at the 1% level of significance. In the presence of non-stationary time series data, this study applies the Johansen co-integration test to check for the long-term association of the variables. The trace statistic in

Table 2 and the max-Eigen statistic in

Table 3 indicate the presence of a long-term relationship with the linear deterministic trend assumption in all the countries. The number of co-integrating equations varied from country to country.

After determining the existence of the long-term relationship by Johansen co-integration, all the variables are entered in the VAR in lagged levels, which simultaneously make it a restricted vector error correction mechanism (VECM) for each country [

32]. It is argued by [

33,

34] that restricted VAR (VECM) performs better in the long term as compared to the short-term time horizon. Therefore, we use restricted VAR to study this long-run behavior of variables. For this reason, we tested all the assumptions for applying restricted VAR (VECM). For the individual countries, the VECM produces six equations for each dependent variable. The basic model estimates the overall effect of the MPTMs on inflation and the GDP.

The findings are useful for policymakers involved in the design and implementation of monetary policy, especially for SAARC Finance. SAARC should start the process for the adoption of a single currency and a single monetary system. First, they will have to remove all restrictions on the movement of capital between member states as a first step of becoming an economic and monetary union. Then as a second step, there will be a need for coordinated efforts to create a unified monetary policy and a unified bank. To undertake this phase SAARC Finance can be utilized at its best, as this department has been developed in each member state’s central bank. Then for the final step, there will be a requirement for the setting of the conversion rates at which member states’ currencies would join the single currency named SAT (South Asian Tiger, a hypothetical name based just on the pattern of the euro).

5. Variance Decomposition Analysis

The GDP variance decomposition and inflation are shown in

Table 4 and

Table 5. For simplicity, this study presents the results for only five time horizons. Moreover, 1 year ahead is the short-term, 4 to 6 years ahead is the medium-term, and 10 years ahead is the long-term.

The results in

Table 4 show that the exchange rate and the credit channel play a comparatively major role and cause variability in the output of each country. In the long run, monetary pulses are primarily transmitted through the economy, primarily through exchange rate channels. Generally, our study obtained a stream of mixed findings. Our results indicate that the exchange rate is a stronger channel in the SAARC region, except for three countries: Nepal, Sri Lanka, and Bangladesh, where the credit channel is relatively more significant. This finding implies that the policy shocks transmit through the BLC and influence the real sector in these three countries. A possible explanation may be found in the region’s financial reforms and growth. Furthermore, bank loans are a pervasive mode of external financing due to the underdeveloped capital market.

In Pakistan and Bangladesh, the monetary pulses transfer in the short term via the exchange rate channel. These findings are consistent with the argument of [

4] that the exchange rate fluctuations cause serious problems in these two countries. However, the situation is different in Sri Lanka, Nepal, and Bhutan, where there is only one channel. In Sri Lanka and Nepal, the credit channel transfers monetary pulses from short to medium and medium to long-term horizons, while in Bhutan, the money channel transfers monetary pulses from medium to long time horizons. We discovered that in the long run, the money and credit channels in Sri Lanka shift with equal strengths and just small fluctuations. These findings are in line with the previous studies on the monetary policy transmission mechanism in Sri Lanka. The credit channel of Sri Lanka shows a good financial system. Nepal, which is the preeminent country of the SAARC from the exchange rate point of view, has a credit channel. The inconsistency of the GDP in Nepal and Sri Lanka could be due to the credit channel without the presence of the other channels.

Our findings indicate that the exchange rate channel is more dominant in the short to medium term, but the money channel is responsible for the long-run time profile in Bangladesh. Similarly, in India, shocks in the exchange rates are more important in the long term but the credit shocks are more important in the short term to the medium term These findings are consistent with previous studies of [

10,

31]. We found that the Maldives exhibits a credit channel in the short run while it exhibits an exchange rate channel in the long run. We explain that tourism is the island’s major source of income and the influx of foreign currency greatly affects the real economy. Money shocks explain the output variability in Pakistan when the forecast horizon ends in the long run, but the exchange rate channel is also responsible in the short run, which depicts that Pakistan is very much dependent on imports and mostly faces trade deficit problems. Our elucidation is in line with the previous findings of [

5].

We observed that the money channel prevails through all time horizons in Bhutan. We explain this by the fact that Bhutan is a small monarchy with less economic development, so the results strongly portray how the money channel transmits monetary impulses to the real sector without any competition.

Table 5 manifests the price variance decomposition. We found that credit and exchange rate shocks are comparatively more significant than money shocks to explain price variability in each country. According to results, both the credit rate and the exchange shocks are becoming more significant with time, but the former appears to be comparatively more imperative in the short run and the long run in Bangladesh.

Our results show that both the credit channel and the money channel are responsible for the variations in price with the money channel being relatively more effective in Bhutan. In Bhutan and India, the results manifest that the money channel is responsible for the inflation variability, but there are also credit and exchange rates. The findings of our study indicate that the exchange rate channel is widespread in Pakistan, which leads to inflationary changes.

Similarly, our results indicate that in Nepal, the credit channel and the exchange rate channel are the main channels, in the short-run exchange rate channel while in the medium and long term the credit channel is responsible for price variation. Sri Lanka has a credit channel and an exchange rate channel in the medium and long-term horizons.

We explain that the countries with an exchange rate channel indicate the reality that they are more susceptible to shocks with the exchange rate due to their reliance on imports and less reliance on exports, which are always valued in US dollars. The significance of the exchange rate channel to explain price variability is not surprising in general. Another plausible explanation could be that these economies are small in size, and they are deeply reliant on their capability to make foreign exchanges. Moreover, there is a strong marginal tendency to import both medium goods and the final goods in these countries. Despite the lack of price data for the Maldives in

Table 5, it is apparent from

Table 4 that the money channel plays a minor role in contrast to the credit and exchange rate channels.

6. Impulse Response Function

Our study employed the generalized impulse response function to examine the responses of the real variables such as GDP and inflation, to the impulses/shocks in the financial and policy variables.

Figure 2,

Figure 3,

Figure 4,

Figure 5,

Figure 6,

Figure 7 and

Figure 8 depict the GDP response to a one-standard deviation in reserves, deposits, credit, and the exchange rate.

Figure 2 and

Figure 3 show that, in both long- and short-time horizons, the GDP response to money and exchange rate shocks is higher in Bangladesh and Bhutan than the response to credit and deposit shocks. The results also indicate that the Indian economy due to innovations responds with the exchange rate and credit shocks more as compared to money and deposit shocks (

Figure 4). Similarly, for the Maldives (

Figure 5), findings suggest that the dependence on the tourism output shows more responses due to the exchange rate pulses as compared to other shocks. Our analysis also revealed that Nepal’s economy (

Figure 6) is more responsive to credit as well as exchange rate shocks as compared to money and deposit shocks. We observed that in Pakistan (

Figure 7), exchange rate shocks are more significant in response to the output following the money shocks in the long term as compared to credit and deposit shocks. Similarly, the results indicate that in Sri Lanka (

Figure 8), the credit channel is more central in transferring the impact of the monetary pulses on the real sector followed by the exchange rate shocks. The results of the impulse response show evidence of an exchange rate and a credit channel common among all SAARC member countries.

Figure 9,

Figure 10,

Figure 11,

Figure 12,

Figure 13 and

Figure 14 present the responses of inflation to the Cholesky one standard deviation innovations in the reserves, deposits, credits, and the exchange rate. The figures indicate that in all countries, inflation response is due to the exchange rate fluctuations. We found that inflation responds more due to credit and the exchange rate channels in Bangladesh. Similarly, the money and credit pulses make the inflation response greater as compared to the exchange rate and interest rate channels in Bhutan. The figures indicate that the Indian economy responds more through inflation due to shocks in the exchange rate and the reserves, also followed by interest rate and credit shocks. In Nepal, the credit shocks and the exchange rate shocks are the main sources of the inflation response which is followed by interest rate shocks. According to findings, in Pakistan, inflation response is more due to the exchange rate shocks as well as money shocks compared to credit and deposit shocks. Inflation in Sri Lanka is more vulnerable to the credit shocks and the money shocks which are followed by deposit and exchange rate shocks. There are no inflation data available for the Maldives, but the highest response for the GDP can be seen due to innovations in the exchange rate.

7. Conclusions

There is a lack of investigation on the relationship between MPTMs and the development of the SAARC economic community. This study fills the existing gap in the existing literature and contributes to optimal currency area theory by providing empirical evidence of the relationship between economic and exchange-rate policy and sustainable development of the SAARC economic community. Our study also investigates the possibility of the economic union from the SAARC perspective and thus contributes to optimal currency theory at the regional level. The findings of this study show that the exchange rate and the credit channel are dominant in all the SAARC countries. Only Bhutan’s economy shows a dissimilar result by having a money channel through the short-term period to the long-term period. The monetary pulses are diffused through the exchange rate and the credit channels from the financial sector to the real sector. The pervasiveness of the exchange rate channel is understood well as all the SAARC economies have more imports than exports. Moreover, the USA is a major import-export partner of all these economies, and all the countries have pegged their currencies fully against the US dollar. This is why any change in monetary policy in the short-term immediately affects the GDP and more prominently the prices through an increase or a decrease in the exchange rates. Moreover, any change in the monetary policy stance will immediately influence the exchange rate. These findings have direct implications for practitioners. Therefore, we suggest to policymakers that in order to lessen the fluctuations of the exchange rate for the economic and the monetary union and to eventually introduce a SAARC single currency, an exchange rate mechanism should be introduced. By integrating their currencies, the member countries can try to prevent large fluctuations relative to one another.

Moreover, the variance decomposition of the GDP and the prices reveals that the credit channel is also a reason for the variability in growth and prices. All the SAARC nations depend on external financing to invest in projects, and the credit channel is prominent mainly through the bank lending channel. As the monetary policy changes, the cost of capital also changes, which consequently affects the overall banking operations in a particular economy by increasing or decreasing the total credit of the economy. Sri Lanka has had the strongest credit channel due to the robust industrialization process for the last few years. The results of the impulse response function also endorse these findings. The findings conclude that the SAARC countries have a financial integration pattern because they have credit as well as exchange rate channels in common in all member countries. The findings of the same monetary channels in the SAARC countries strengthen this view that it can become a monetary union. The absence of a money channel (except for Bhutan) clearly shows the absence of organized securities and a derivatives market structure in this SAARC block. This result endorses prior assumptions that the SAARC region, which is where the money market is comparatively undeveloped, will not be the principal conduit for shocks to the monetary policy. The fewer choices of risk mitigating techniques make this block collectively more vulnerable to changes in international economic shocks, in which the exchange rate shock is the main one. To be less vulnerable to exchange rate shocks, a better exchange rate system should be implemented through reforms and collective efforts by developing trade integration within the SAARC countries. All SAARC member countries have the potential to form a monetary union from an economic block because of the common existence of credit and exchange rate monetary channels that may serve as a base for supporting the idea of one economic union among member countries as references [

25] and [

26] stated that the exchange rate channel is important for the effective operation of the European Monetary Union. However, they have to synchronize their monetary channels. The results support the idea that the SAARC countries have sufficient prospects for a monetary union involving a single currency unit. However, a lot of work is required on the monetary, economic, and most importantly on the political levels.

In Pakistan, India, and Bangladesh, there is evidence of a money channel over the long-run time horizon. These findings suggest that they are the main member economies of the SAARC countries with India having the most economic significance. Our results offer important implications for policymakers who are interested in monetary policy design and implementation especially for SAARC Finance, which has been created as a separate department in each country’s central bank.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, M.Z., F.K., M.R., M.Z.U.H. and J.S.; Methodology, M.Z.U.H.; Investigation, F.K.; Data curation, F.K.; Supervision, W.L. and J.H.; Writing—original draft, M.Z., M.R. and J.S.; Writing—review and editing, W.L. and J.H. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by the Ministry of Education of the Republic of Korea and the National Research Foundation of Korea (NRF-2019S1A3A2098438).

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Bernanke, B.S.; Gertler, M. Inside the Black Box: The Credit Channel of Monetary Policy Transmission. J. Econ. Perspect. 1995, 9, 27–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohanty, R.K.; Bhanumurthy, N.R. Asymmetric Monetary Policy Transmission in India: Does Financial Friction Matter? (No. 03/2020); BASE University: Bengaluru, India, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Dabla-Norris, M.E.; Floerkemeier, H. Transmission mechanisms of monetary policy in Armenia: Evidence from VAR analysis (No. 6-248); International Monetary Fund: Washington, DC, USA, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Agha, A.I.; Ahmed, N.; Mubarik, Y.A.; Shah, H. Transmission mechanism of monetary policy in Pakistan. SBP-Res. Bull. 2005, 1, 1–23. [Google Scholar]

- Mukhtar, T.; Younas, M.Z. Monetary Policy Transmission Mechanism of Pakistan: Evidence from Bank Lending and Asset Price Channels. Asian J. Econ. Model. 2019, 7, 121–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skibińska, M. Transmission of monetary policy and exchange rate shocks under foreign currency lending. Post-Communist Econ. 2018, 30, 506–525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mehmood, S.; Carter, D. Dynamics of Exports and Economic Growth at Regional Level: A Study on Pakistan’s Exports to SAARC. J. Contemp. Issues Bus. Res. 2012, 1, 11–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Mabati, J.R.; Onserio, R.F. The Effect of Central Bank Rate on Financial Performance of Commercial Banks in Kenya. J. Financ. Account. 2020, 4, 25–40. [Google Scholar]

- Mundell, R. The case for a world currency. J. Policy Model. 2012, 34, 568–578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qingquan, J.; Khattak, S.I.; Ahmad, M.; Ping, L. A new approach to environmental sustainability: Assessing the impact of monetary policy on CO2 emissions in Asian economies. Sustain. Dev. 2020, 28, 1331–1346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuelan, P.; Akbar, M.W.; Hafeez, M.; Ahmad, M.; Zia, Z.; Ullah, S. The nexus of fiscal policy instruments and environmental degradation in China. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2019, 26, 28919–28932. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nyumuah, F.S. An Empirical Analysis of the Monetary Transmission Mechanism of Developing Economies: Evidence from Ghana. Int. J. Econ. Financ. 2018, 10, 72–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Angeloni, I.; Kashyap, A.; Mojon, B. Monetary Policy Transmission in the Euro Area: A Decade after the Introduction of the Euro; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Mishkin, F. Symposium on the monetary policy transmission mechanism. J. Econ. Perspect. 1995, 9, 3–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leshoro, T.L. Monetary policy or fiscal policy, which one better explains inflation dynamics in South Africa? Afr. J. Bus. Econ. Res. 2020, 15, 146–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vizek, M. Ekonometrijska analiza kanala monetarnog prijenosa u Hrvatskoj. Privred. kretanja i Ekon. Polit. 2006, 16, 29–61. [Google Scholar]

- Morales, R.A.; Raei, F. The Evolving Role of Interest Rate and Exchange Rate Channels in Monetary Policy Transmission in EAC Countries; International Monetary Fund Working Paper; No WP/13/X; IMF: Washington, DC, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Heryan, T.; Tzeremes, P.G. The bank lending channel of monetary policy in EU countries during the global financial crisis. Econ. Model. 2017, 67, 10–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mojon, B. Financial Structure and the Interest Rate Channel of ECB Monetary Policy, s.l.; European Central Bank: Frankfurt am Main, Germany, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Bernanke, B.S.; Blinder, A.S. Credit, Money, and Aggregate Demand (No. w2534); National Bureau of Economic Research: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Horvath, R.; Kotlebova, J.; Siranova, M. Interest rate pass-through in the euro area: Financial fragmentation, balance sheet policies and negative rates. J. Financ. Stab. 2018, 36, 12–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ozsahin, S. The Bank Lending Channel of Monetary Policy and Its Implications on Bank Regulations: Findings with Euro Area Bank Lending Surveys; Research paper; Graduate Institute of International Studies: Geneva, Switzerland, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Ciccarelli, M.; Maddaloni, A.; Peydró, J.-L. Trusting the bankers: A new look at the credit channel of monetary policy. Rev. Econ. Dyn. 2015, 18, 979–1002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Topi, J.; Vilmunen, J. Transmission of monetary policy shocks in Finland: Evidence from bank-level data on loans. SSRN 2003, 372–380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khozeimeh, A.M.; Aminifard, A.; Zare, H.; Ebrahimi, M. The Monetary Policy Transmission Mechanism in the Framework of the Term Structure of Interest Rate in Iran’s Economy. J. Econ. Modeling 2018, 9, 1–34. [Google Scholar]

- Egea, F.B.; Hierro, L.Á. Transmission of monetary policy in the US and EU in times of expansion and crisis. J. Policy Modeling 2019, 41, 763–783. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Durevall, D.; Ndung’U, N. A dynamic model of inflation of Kenya, 1974-96. J. Afr. Econ. 2001, 10, 92–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, M.K.C. A VAR analysis of Kenya’s monetary policy transmission mechanism: How does the central bank’s REPO rate affect the economy? (No. 6-300); International Monetary Fund: Washington, DC, USA, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Abdul Karim, Z.; Wan Ngah, W.A.S.; Abdul Karim, B. Bank Lending Channel of Monetary Policy: Dynamic Panel Data Evidence from Malaysia; The University Library LMU: Munich, Germany, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Grandi, P. Sovereign stress and heterogeneous monetary transmission to bank lending in the euro area. Eur. Econ. Rev. 2019, 119, 251–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aleem, A. Transmission mechanism of monetary policy in India. J. Asian Econ. 2010, 21, 186–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dale, S.; Haldane, A.G. Interest rates and the channels of monetary transmission: Some sectoral estimates. Eur. Econ. Rev. 1995, 39, 1611–1626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erdogdu, A. Functioning and Effectiveness of Monetary Transmission Mechanisms: Turkey Applications. J. Financ. Bank Manag. 2017, 5, 29–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Narayan, P.; Smyth, R.; Nandha, M. Interdependence and dynamic linkages between the emerging stock markets of South Asia. Account. Financ. 2004, 44, 419–439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Figure 1.

General monetary policy transmission mechanism (source; European monetary bank).

Figure 1.

General monetary policy transmission mechanism (source; European monetary bank).

Figure 2.

Bangladesh Responses of GDP to Cholesky One S.D. Innovations. (a) Response of GDP to Reserves; (b) Response of GDP to Deposits; (c) Response of GDP to Credits (d) Response of GDP to Exchange Rate.

Figure 2.

Bangladesh Responses of GDP to Cholesky One S.D. Innovations. (a) Response of GDP to Reserves; (b) Response of GDP to Deposits; (c) Response of GDP to Credits (d) Response of GDP to Exchange Rate.

Figure 3.

Bhutan Responses of GDP to Cholesky One S.D. Innovations. (a) Response of GDP to Reserves; (b) Response of GDP to Deposits; (c) Response of GDP to Credits (d) Response of GDP to Exchange Rate.

Figure 3.

Bhutan Responses of GDP to Cholesky One S.D. Innovations. (a) Response of GDP to Reserves; (b) Response of GDP to Deposits; (c) Response of GDP to Credits (d) Response of GDP to Exchange Rate.

Figure 4.

India Responses of GDP to Cholesky One S.D. Innovations. (a) Response of GDP to Reserves; (b) Response of GDP to Deposits; (c) Response of GDP to Credits (d) Response of GDP to Exchange Rate.

Figure 4.

India Responses of GDP to Cholesky One S.D. Innovations. (a) Response of GDP to Reserves; (b) Response of GDP to Deposits; (c) Response of GDP to Credits (d) Response of GDP to Exchange Rate.

Figure 5.

Maldives Responses of GDP to Cholesky One S.D. Innovations. (a) Response of GDP to Reserves; (b) Response of GDP to Deposits; (c) Response of GDP to Credits (d) Response of GDP to Exchange Rate.

Figure 5.

Maldives Responses of GDP to Cholesky One S.D. Innovations. (a) Response of GDP to Reserves; (b) Response of GDP to Deposits; (c) Response of GDP to Credits (d) Response of GDP to Exchange Rate.

Figure 6.

Nepal Responses of GDP to Cholesky One S.D. Innovations. (a) Response of GDP to Reserves; (b) Response of GDP to Deposits; (c) Response of GDP to Credits (d) Response of GDP to Exchange Rate.

Figure 6.

Nepal Responses of GDP to Cholesky One S.D. Innovations. (a) Response of GDP to Reserves; (b) Response of GDP to Deposits; (c) Response of GDP to Credits (d) Response of GDP to Exchange Rate.

Figure 7.

Pakistan Responses of GDP to Cholesky One S.D. Innovations. (a) Response of GDP to Reserves; (b) Response of GDP to Deposits; (c) Response of GDP to Credits (d) Response of GDP to Exchange Rate.

Figure 7.

Pakistan Responses of GDP to Cholesky One S.D. Innovations. (a) Response of GDP to Reserves; (b) Response of GDP to Deposits; (c) Response of GDP to Credits (d) Response of GDP to Exchange Rate.

Figure 8.

Sri Lanka Responses of GDP to Cholesky One S.D. Innovations. (a) Response of GDP to Reserves; (b) Response of GDP to Deposits; (c) Response of GDP to Credits (d) Response of GDP to Exchange Rate.

Figure 8.

Sri Lanka Responses of GDP to Cholesky One S.D. Innovations. (a) Response of GDP to Reserves; (b) Response of GDP to Deposits; (c) Response of GDP to Credits (d) Response of GDP to Exchange Rate.

Figure 9.

Bangladesh Responses of Inflation to Cholesky One S.D. Innovations. (a) Response of Inflation to Reserves; (b) Response of Inflation to Deposits; (c) Response of Inflation to Credits (d) Response of Inflation to Exchange Rate.

Figure 9.

Bangladesh Responses of Inflation to Cholesky One S.D. Innovations. (a) Response of Inflation to Reserves; (b) Response of Inflation to Deposits; (c) Response of Inflation to Credits (d) Response of Inflation to Exchange Rate.

Figure 10.

Bhutan Responses of Inflation to Cholesky One S.D. Innovations. (a) Response of Inflation to Reserves; (b) Response of Inflation to Deposits; (c) Response of Inflation to Credits (d) Response of Inflation to Exchange Rate.

Figure 10.

Bhutan Responses of Inflation to Cholesky One S.D. Innovations. (a) Response of Inflation to Reserves; (b) Response of Inflation to Deposits; (c) Response of Inflation to Credits (d) Response of Inflation to Exchange Rate.

Figure 11.

India Responses of Inflation to Cholesky One S.D. Innovations. (a) Response of Inflation to Reserves; (b) Response of Inflation to Deposits; (c) Response of Inflation to Credits (d) Response of Inflation to Exchange Rate.

Figure 11.

India Responses of Inflation to Cholesky One S.D. Innovations. (a) Response of Inflation to Reserves; (b) Response of Inflation to Deposits; (c) Response of Inflation to Credits (d) Response of Inflation to Exchange Rate.

Figure 12.

Nepal Responses of Inflation to Cholesky One S.D. Innovations. (a) Response of Inflation to Reserves; (b) Response of Inflation to Deposits; (c) Response of Inflation to Credits (d) Response of Inflation to Exchange Rate.

Figure 12.

Nepal Responses of Inflation to Cholesky One S.D. Innovations. (a) Response of Inflation to Reserves; (b) Response of Inflation to Deposits; (c) Response of Inflation to Credits (d) Response of Inflation to Exchange Rate.

Figure 13.

Pakistan Responses of Inflation to Cholesky One S.D. Innovations. (a) Response of Inflation to Reserves; (b) Response of Inflation to Deposits; (c) Response of Inflation to Credits (d) Response of Inflation to Exchange Rate.

Figure 13.

Pakistan Responses of Inflation to Cholesky One S.D. Innovations. (a) Response of Inflation to Reserves; (b) Response of Inflation to Deposits; (c) Response of Inflation to Credits (d) Response of Inflation to Exchange Rate.

Figure 14.

Sri Lanka Responses of Inflation to Cholesky One S.D. Innovations. (a) Response of Inflation to Reserves; (b) Response of Inflation to Deposits; (c) Response of Inflation to Credits (d) Response of Inflation to Exchange Rate.

Figure 14.

Sri Lanka Responses of Inflation to Cholesky One S.D. Innovations. (a) Response of Inflation to Reserves; (b) Response of Inflation to Deposits; (c) Response of Inflation to Credits (d) Response of Inflation to Exchange Rate.

Table 1.

Descriptive statistics.

Table 1.

Descriptive statistics.

| Country Name | Variable | Proxy | Mean | S.D | Minimum | Maximum |

|---|

| Bangladesh | Reserves | Includes gold, current US$ (in millions) | 2271.87 | 2774.02 | 148.26 | 11,174.82 |

| Deposits | Demand deposits + time saving foreign currency deposits (in million) | 590,890.35 | 778,274.64 | 11,119.40 | 2,886,910 |

| Credit | Domestic credit to private sector (% of GDP) | 20.34 | 12.78 | 1.92 | 48.82 |

| Exchange rate | Local currency unit (LCU) per US$, period average | 41.93 | 19.94 | 12.19 | 81.86 |

| Inflation | Gross domestic product (GDP) deflator (annual %) | 8.39 | 13.79 | −17.63 | 80.57 |

| GDP | Gross domestic product (GDP) growth (annual %) | 4.52 | 2.04 | −4.09 | 7.07 |

| Bhutan | Reserves | Includes gold, current US$ (in million) | 308.23 | 280.60 | 35.48 | 1002.13 |

| Deposits | Demand deposits + time saving foreign currency deposits (in million) | 6502 | 7144.71 | 302.50 | 23,747.29 |

| Credit | Domestic credit to private sector (% of GDP) | 12.86 | 12.21 | 2.51 | 50.04 |

| Exchange rate | LCU per US$, period average | 28.30 | 16.28 | 7.86 | 53.44 |

| Inflation | Consumer price Percent Change over Corresponding Period of Previous Year | 7.92 | 3.73 | 1.57 | 18.02 |

| GDP | GDP growth (annual %) | 7.88 | 5.31 | −0.41 | 28.70 |

| India | Reserves | Includes gold, current US$ (in million) | 66,518.48 | 96,315.56 | 2064.42 | 300,480 |

| Deposits | Demand deposits + time saving foreign currency deposits (in million) | 10,332,558.05 | 15,156,586 | 141,698 | 59,078,200 |

| Credit | Domestic credit to private sector (% of GDP) | 28.05 | 9.76 | 14.68 | 49.93 |

| Exchange rate | LCU per US$, period average | 28.30 | 16.28 | 7.86 | 53.44 |

| Inflation | Consumer price Percent Change over Corresponding Period of Previous Year | 7.46 | 4.04 | −7.63 | 13.87 |

| GDP | GDP growth (annual %) | 5.92 | 2.96 | −5.24 | 10.55 |

| Maldives | Reserves | Includes gold, current US$ (in million) | 93.85 | 110.14 | 0.01 | 364.31 |

| Deposits | Demand deposits + time saving foreign currency deposits (in million) | 1870.96 | 2734.52 | 24.21 | 10,744.52 |

| Credit | Domestic credit to private sector (% of GDP) | 25.88 | 18.87 | 5.14 | 69.33 |

| Exchange rate | LCU per US$, period average | 10.47 | 2.47 | 5.76 | 15.36 |

| Inflation | Consumer price Percent Change over Corresponding Period of Previous Year | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| GDP | GDP growth (annual %) | 7.47 | 6.85 | −8.68 | 19.59 |

| Nepal | Reserves | Includes gold, current US$ (in million) | 882.85 | 899.16 | 105.46 | 3,630.83 |

| Deposits | Demand deposits + time saving foreign currency deposits (in million) | 86,737.25 | 112,908.96 | 1179.20 | 432,897 |

| Credit | Domestic credit to private sector (% of GDP) | 21.01 | 15.05 | 3.63 | 59.18 |

| Exchange rate | LCU per US$, period average | 45.07 | 26.47 | 11.00 | 85.20 |

| Inflation | Consumer price Percent Change over Corresponding Period of Previous Year | 8.36 | 4.42 | −3.11 | 19.00 |

| GDP | GDP growth (annual %) | 4.17 | 2.52 | −2.98 | 9.68 |

| Pakistan | Reserves | Includes gold, current US$ (in million) | 4,695.67 | 5,338.44 | 562.99 | 17,697.92 |

| Deposits | Demand deposits + time saving foreign currency deposits (in million) | 708,565.75 | 873,774.36 | 25,283.40 | 3,344,350 |

| Credit | Domestic credit to private sector (% of GDP) | 24.68 | 2.80 | 18.37 | 29.84 |

| Exchange rate | LCU per US$, period average | 37.32 | 25.81 | 9.90 | 93.40 |

| Inflation | Consumer price Percent Change over Corresponding Period of Previous Year | 8.86 | 4.22 | 2.91 | 20.90 |

| GDP | GDP growth (annual %) | 5.04 | 2.11 | 1.01 | 10.22 |

| Sri Lanka | Reserves | GDP growth (annual %) | 1630.49 | 1735.59 | 57.43 | 7195.35 |

| Deposits | Includes gold, current US$ (in million) | 420,848.82 | 583,884.96 | 3090.40 | 2,248,870 |

| Credit | Demand deposits + time saving foreign currency deposits (in million) | 22.82 | 7.34 | 8.82 | 33.97 |

| Exchange rate | Domestic credit to private sector (% of GDP) | 57.54 | 37.55 | 7.01 | 127.62 |

| Inflation | Consumer price Percent Change over Corresponding Period of Previous Year | 10.62 | 5.69 | 1.22 | 26.15 |

| GDP | GDP growth (annual %) | 5.05 | 1.86 | −1.55 | 8.25 |

Table 2.

Johansen co-integration test (trace statistic).

Table 2.

Johansen co-integration test (trace statistic).

| Country | Eigenvalue | Trace Statistic | Critical Value | p-Value |

|---|

| Bangladesh | 0.99 | 210.85 | 41.66 | 0.0000 |

| Bhutan | 0.95 | 153.68 | 95.75 | 0.0000 |

| India | 0.89 | 202.71 | 95.75 | 0.0000 |

| Maldives | 0.75 | 70.78 | 69.81 | 0.0418 |

| Nepal | 0.84 | 123.471 | 95.75 | 0.0002 |

| Pakistan | 0.75 | 98.67 | 95.75 | 0.0310 |

| Sri Lanka | 0.68 | 123.90 | 95.75 | 0.0002 |

Table 3.

Johansen co-integration test (maximum eigenvalue).

Table 3.

Johansen co-integration test (maximum eigenvalue).

| Country | Eigenvalue | Max-Eigen Statistic | Critical Value | p-Value |

|---|

| Bangladesh | 0.99 | 113.48 | 40.07 | 0.0000 |

| Bhutan | 0.95 | 63.27 | 40.07 | 0.0000 |

| India | 0.89 | 66.74 | 40.077 | 0.0000 |

| Maldives | 0.75 | 33.88 | 33.87 | 0.0498 |

| Nepal | 0.84 | 44.82 | 44.70 | 0.0143 |

| Pakistan | 0.75 | 43.29 | 40.07 | 0.0210 |

| Sri Lanka | 0.37 | 15.20 | 14.26 | 0.0354 |

Table 4.

Variance decomposition of GDP.

Table 4.

Variance decomposition of GDP.

| Country | Years Ahead | Reserves | Deposits | Credits | Exchange Rate | Inflation | GDP |

|---|

| Bangladesh | 1 | 4.079 | 4.102 | 0.491 | 7.054 | 0.1572 | 84.114 |

| 2 | 3.513 | 2.619 | 1.390 | 12.168 | 0.3978 | 79.910 |

| 5 | 12.347 | 2.618 | 3.171 | 12.793 | 1.4676 | 67.600 |

| 6 | 12.593 | 2.981 | 3.332 | 12.672 | 1.512 | 66.907 |

| 9 | 15.412 | 3.287 | 4.143 | 12.092 | 1.546 | 63.517 |

| 10 | 16.131 | 3.398 | 4.344 | 11.935 | 1.527 | 62.662 |

| Bhutan | 1 | 39.237 | 3.298 | 0.721 | 18.566 | 8.961 | 29.214 |

| 2 | 33.207 | 3.485 | 8.294 | 22.196 | 8.676 | 24.139 |

| 5 | 32.352 | 9.765 | 10.912 | 15.164 | 10.521 | 21.282 |

| 6 | 30.774 | 9.549 | 11.612 | 14.917 | 9.998 | 23.147 |

| 9 | 29.070 | 11.410 | 12.851 | 14.292 | 10.366 | 22.008 |

| 10 | 28.601 | 11.990 | 13.463 | 14.054 | 10.228 | 21.661 |

| India | 1 | 0.005 | 24.270 | 2.4568 | 12.101 | 0.214 | 60.950 |

| 2 | 3.731 | 17.806 | 18.676 | 9.326 | 5.947 | 44.513 |

| 5 | 3.597 | 14.128 | 17.870 | 23.156 | 6.269 | 34.976 |

| 6 | 12.429 | 17.093 | 14.735 | 24.633 | 4.751 | 26.355 |

| 9 | 14.003 | 16.053 | 11.586 | 33.236 | 4.060 | 21.059 |

| 10 | 19.744 | 15.561 | 9.881 | 28.220 | 5.1983 | 21.393 |

| Maldives | 1 | 1.5829 | 5.501 | 18.889 | 16.200 | NA | 57.824 |

| 2 | 11.316 | 9.474 | 16.059 | 17.316 | NA | 45.833 |

| 5 | 14.531 | 7.001 | 13.561 | 24.179 | NA | 40.725 |

| 6 | 14.983 | 6.646 | 13.222 | 25.092 | NA | 40.054 |

| 6 | 15.648 | 5.936 | 12.615 | 26.790 | NA | 39.009 |

| 10 | 15.792 | 5.788 | 12.488 | 27.144 | NA | 38.785 |

| Nepal | 1 | 0.669 | 5.173 | 48.583 | 0.887 | 0.0847 | 44.600 |

| 2 | 1.614 | 4.306 | 46.470 | 1.027 | 8.554 | 38.026 |

| 5 | 3.262 | 2.956 | 52.934 | 6.064 | 6.587149 | 28.194 |

| 6 | 3.426 | 2.633 | 54.277 | 5.404 | 7.467510 | 26.790 |

| 9 | 4.012 | 1.952 | 57.083 | 4.215 | 6.778864 | 25.95 |

| 10 | 4.103 | 1.810 | 57.766 | 3.909 | 6.881223 | 25.528 |

| Pakistan | 1 | 0.112 | 33.210 | 0.3898 | 15.916 | 0.194 | 50.176 |

| 2 | 14.844 | 27.671 | 3.439 | 25.952 | 0.828 | 27.263 |

| 5 | 33.293 | 16.934 | 1.991 | 19.949 | 11.738 | 16.092 |

| 6 | 35.336 | 15.288 | 1.9291 | 21.404 | 11.178 | 14.863 |

| 9 | 40.918 | 11.989 | 1.466 | 21.481 | 12.485 | 11.659 |

| 10 | 41.955 | 11.259 | 1.384 | 21.794 | 12.519 | 11.086 |

| Sri Lanka | 1 | 0.460 | 7.855 | 14.553 | 0.354 | 1.665 | 75.111 |

| 2 | 9.109 | 15.372 | 10.641 | 5.148 | 2.327 | 57.400 |

| 5 | 8.311 | 26.077 | 8.824 | 4.665 | 3.933 | 48.187 |

| 6 | 8.643 | 25.505 | 10.555 | 4.474 | 4.325 | 46.495 |

| 9 | 8.728 | 22.153 | 17.683 | 4.005 | 4.994 | 42.434 |

| 10 | 8.547 | 21.418 | 19.355 | 3.997 | 4.939 | 41.741 |

Table 5.

Variance decomposition of inflation.

Table 5.

Variance decomposition of inflation.

| Country | Years Ahead | Reserves | Deposits | Credits | Exchange Rate | Inflation | GDP |

|---|

| Bangladesh | 1 | 0.956696 | 1.096703 | 46.26428 | 10.01982 | 41.66250 | 0.000000 |

| 2 | 3.731224 | 9.323809 | 48.29534 | 19.74191 | 18.90056 | 0.007162 |

| 5 | 2.160343 | 19.94079 | 39.72572 | 27.54608 | 10.33641 | 0.290653 |

| 6 | 1.850385 | 20.53434 | 39.46416 | 28.81937 | 8.981490 | 0.350263 |

| 9 | 1.334624 | 22.44601 | 38.67610 | 30.51728 | 6.689439 | 0.336544 |

| 10 | 1.224289 | 22.84178 | 38.47436 | 30.93246 | 6.180165 | 0.346936 |

| Bhutan | 1 | 23.33470 | 8.324913 | 6.432574 | 3.808374 | 58.09943 | 0.000000 |

| 2 | 31.25300 | 7.861245 | 5.776591 | 3.344549 | 50.74801 | 1.016605 |

| 5 | 30.79320 | 9.471838 | 10.47824 | 3.810558 | 44.04777 | 1.398401 |

| 6 | 29.99789 | 9.751945 | 12.76633 | 4.508415 | 41.70019 | 1.275231 |

| 9 | 26.07065 | 12.74983 | 20.98766 | 4.506489 | 34.57522 | 1.110155 |

| 10 | 25.25402 | 13.20256 | 22.90797 | 4.767962 | 32.75376 | 1.113721 |

| India | 1 | 22.00811 | 15.83404 | 7.848166 | 10.49762 | 43.81206 | 0.000000 |

| 2 | 20.08305 | 15.26999 | 11.33230 | 9.458584 | 43.05388 | 0.802197 |

| 5 | 21.53749 | 17.43836 | 7.246814 | 13.26183 | 30.18567 | 10.32984 |

| 6 | 19.96705 | 17.65204 | 6.539521 | 18.90809 | 27.26061 | 9.672699 |

| 9 | 19.16503 | 17.29571 | 8.060042 | 20.50875 | 25.23083 | 9.739636 |

| 10 | 21.23239 | 16.32044 | 7.701426 | 21.19263 | 24.42108 | 9.132039 |

| Maldives | 1 | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| 2 | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| 5 | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| 6 | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| 9 | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| 10 | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| Nepal | 1 | 0.138837 | 23.30758 | 22.35945 | 30.21253 | 23.98160 | 0.000000 |

| 2 | 0.375942 | 22.22197 | 21.58003 | 34.68473 | 20.82742 | 0.309899 |

| 5 | 0.753800 | 17.83638 | 27.21245 | 27.06629 | 18.95892 | 8.172160 |

| 6 | 0.762117 | 17.17560 | 28.57249 | 26.01080 | 18.43222 | 9.046777 |

| 9 | 0.825336 | 15.63048 | 30.60555 | 24.10449 | 16.42607 | 12.40807 |

| 10 | 0.810631 | 15.41151 | 31.02590 | 23.85777 | 15.66283 | 13.23136 |

| Pakistan | 1 | 1.356259 | 0.079264 | 0.590814 | 11.94868 | 86.02498 | 0.000000 |

| 2 | 0.712476 | 0.504440 | 0.321134 | 19.76820 | 78.68247 | 0.011274 |

| 5 | 1.546271 | 0.618388 | 0.217213 | 26.13090 | 70.88660 | 0.600628 |

| 6 | 1.888621 | 0.518865 | 0.208246 | 26.86204 | 69.79874 | 0.723492 |

| 9 | 2.556038 | 0.363418 | 0.217268 | 27.88259 | 68.06099 | 0.919697 |

| 10 | 2.670885 | 0.331522 | 0.217395 | 28.06491 | 67.75357 | 0.961719 |

| Sri Lanka | 1 | 9.415843 | 0.394985 | 0.051548 | 8.723268 | 81.41436 | 0.000000 |

| 2 | 8.385447 | 9.335298 | 0.195641 | 7.905981 | 73.06496 | 1.112671 |

| 5 | 9.726606 | 10.53960 | 1.043765 | 11.21571 | 60.96313 | 6.511182 |

| 6 | 9.765432 | 11.93481 | 1.517645 | 10.96182 | 59.46123 | 6.359066 |

| 9 | 10.18516 | 12.40230 | 1.635915 | 10.77979 | 58.03110 | 6.965729 |

| 10 | 10.12958 | 12.73218 | 1.629186 | 10.76560 | 57.64717 | 7.096293 |

| Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).