Architecture and Recreation as a Political Tool—Seaside Architectural Heritage of the Worker Holiday Fund (WHF) in the Era of the Polish People’s Republic (1949–1989)

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

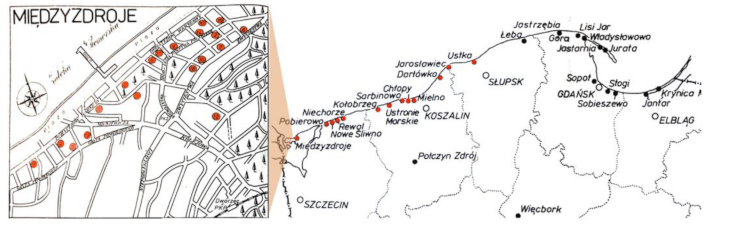

- identification of the indicated facilities, i.e., searching by the original address and location, reported to WHF as a holiday house, which consisted of many buildings scattered around the town. The identification was difficult because the given WHF holiday center’s facilities inventoried under one name (e.g., Błyskawica I) as a result of subsequent commercialization and privatization of the WHF property were usually rebuilt many times with their name changed. Finally, 58 holiday houses were identified (facilities are listed in Appendix A and Appendix B), including 38 in the Międzyzdroje district and 20 in the Koszalin district. Archival photos were found for most of them;

- spotting WHF holiday center’s facilities in the spatial structure of a town;

- comparing the past and present architecture of the facilities on the basis of the collected iconographic documentation (historical photos and postcards) with the materials obtained during field studies;

- analyzing, describing and interpreting, resulting in a typology of WHF holiday center’s facilities. The typology was based on the genesis of the object, architectural features and the influence of politics.

3. Development and Organization of Worker Holidays in the Polish People’s Republic

4. Characterization and Typification of WHF Seaside Tourist Architecture in Western Pomerania

5. Discussion

6. Conclusions

- adapted facilities: former villas and guesthouses

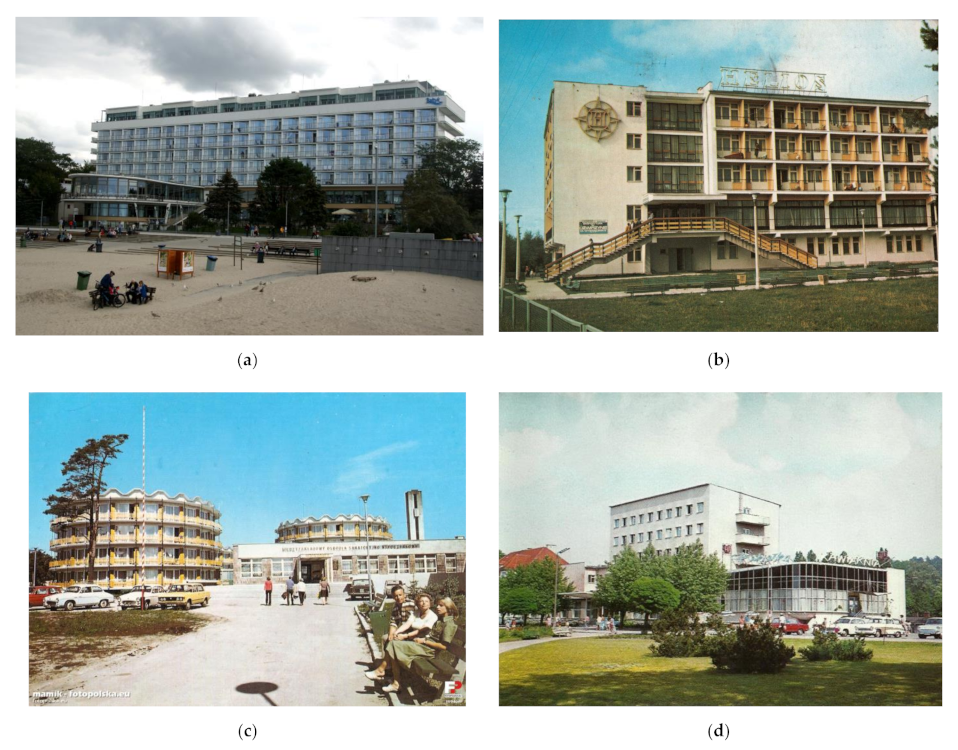

- new facilities: sanatoriums

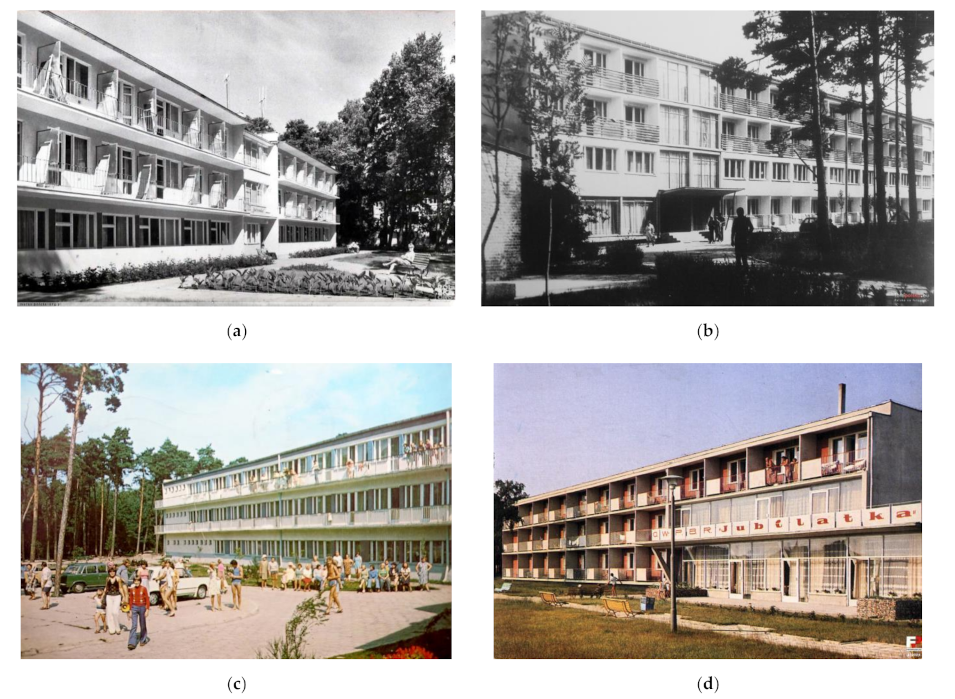

- new facilities: pavilions

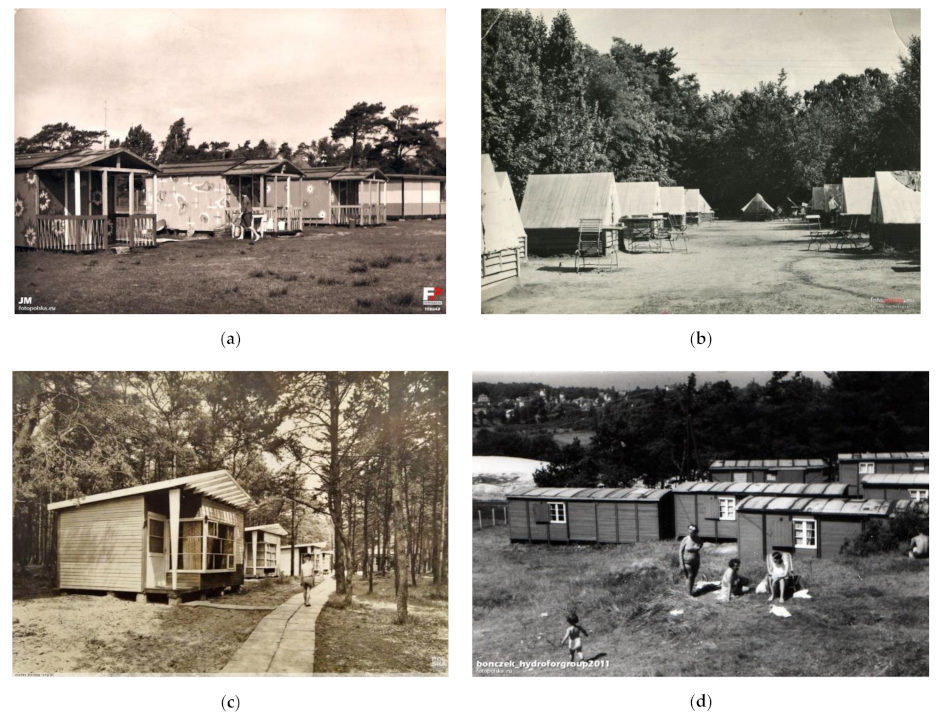

- new facilities: light, temporary (summer and camping houses).

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| Międzyzdroje District | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Locality | Number | Holiday House | Archive Photo/Address |

| Międzyzdroje (76 buildings, 36 camping houses) | 1 | “Błyskawica” holiday house made up of 7 buildings:

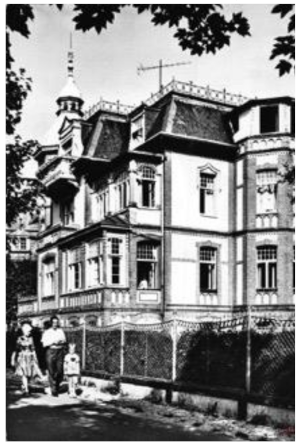

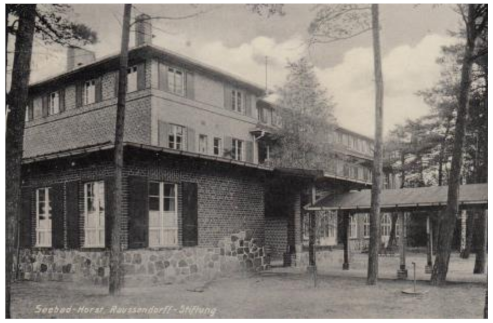

|  “Błyskawica” WHF’s holiday house. Pre-war photo. https://fotopolska.eu/ (accessed on 7 June 2021) Address: Książąt Pomorskich Street, no.17 |

| 2 | “Delfin” holiday house made up of 5 buildings:

|  The view from the church tower in Międzyzdroje. In the foreground, “Delfin” holiday house, between 1960 and 1965. https://fotopolska.eu/ (accessed on 7 June 2021) Address: Zwycięzców Street, no. 13 | |

| 3 | “Energia” holiday house made up of 5 buildings:

|  “Energia III” WHF’s holiday house, 1965. https://fotopolska.eu/(accessed on 7 June 2021) Address: M. Fornalskiej Street, no. 3 (present: Plażowa Street) | |

| 4 | “Fala” holiday house made up of 4 buildings:

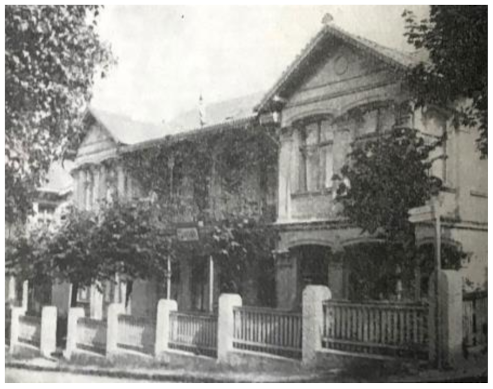

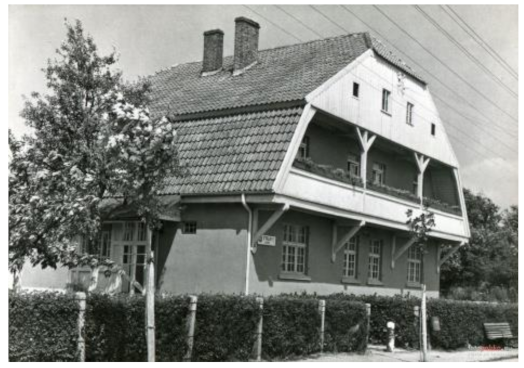

|  “Fala” WHF’s holiday house. Pre-war photo. https://fotopolska.eu/ (accessed on 19 March 2021) Address: Bohaterów Warszawy Street, no. 8 | |

| 5 | “Kasia” holiday house made up of 11 buildings:

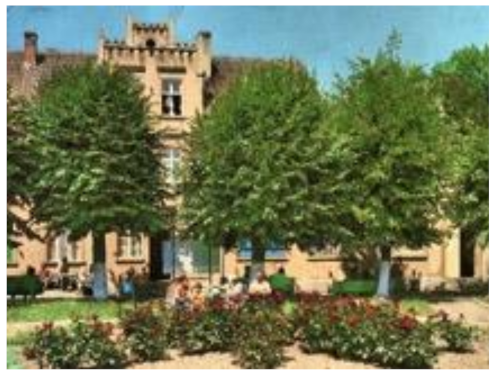

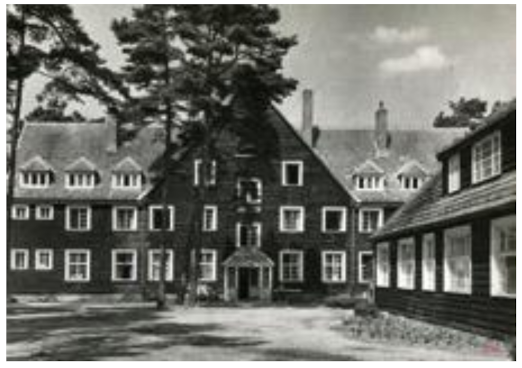

|  “Kasia” Holiday House. Wczasy Pracownicze FWP. Informator FWP. 1978. Warszawa: Instytut Wydawniczy CRZZ, p. 175. Address: Ludowa Street, no. 1 | |

| 6 | “Korsarz” holiday house made up of 4 buildings:

|  “Korsarz” WHF’s holiday house. https://fotopolska.eu/ (accessed on 19 March 2021) Address: Zwycięstwa Street, no. 33 | |

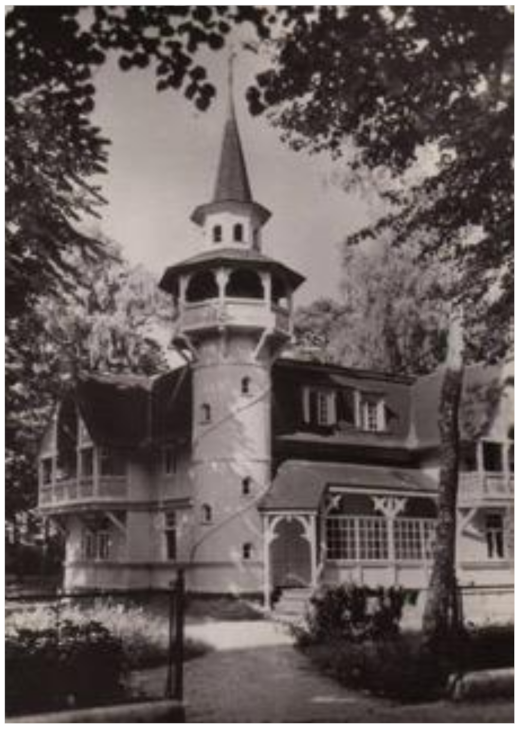

| 7 | “Latarnia Morska” holiday house made up of 5 buildings:

|  “Latarnia Morska” WHF’s holiday house. Pre-war photo. https://fotopolska.eu/ (accessed on 19 March 2021) Address: Bohaterów Warszawy Street, no. 18 | |

| 8 | “Leśnik” holiday house made up of 36 camping houses:

| No archival photos available Address: Leśna Street, no. 15 | |

| 9 | “Mars” holiday house made up of 3 buildings:

|  “Mars” WHF’s holiday house. Pre-war photo. https://fotopolska.eu/ (accessed on 19 March 2021) Address: 1000-lecia Państwa Polskiego, no. 3 | |

| 10 | “Mewa” holiday house made up of 4 buildings:

| No archival photos available Address: Pomorska Street, no. 9 | |

| 11 | “Minerwa” holiday house made up of 5 buildings:

|  “Minerwa” WHF’s holiday house. Pre-war photo. https://fotopolska.eu/ (accessed on 7 July 2021) Address: Zdrojowa Street, no. 10 | |

| 12 | “Morskie Oko” holiday house made up of 4 buildings:

| No archival photos available Address: Lipowa Street, no. 3 | |

| 13 | “Patria” holiday house made up of 5 buildings:

| No archival photos available Address: Rybacka Street, no. 1 | |

| 14 | “Polonia” holiday house made up of 1 building:

|  Międzyzdroje. “Polonia” WHF’s Holiday House, between 1965 and 1968. Photo J. Korpal. Postcard by RUCH. https://fotopolska.eu/ (accessed on 5 July 2021) Address: Bohaterów Warszawy Street, no. 30 | |

| 15 | “Posejdon” holiday house made up of 1 building:

|  “Posejdon” holiday house, between 1970 and 1972. https://fotopolska.eu/ (accessed on 19 March 2021) Address: Bohaterów Warszawy Street, no. 23 | |

| 16 | “Rybitwa” holiday house made up of 4 buildings:

|  “Rybitwa” holiday house, between 1934 and 1939. https://fotopolska.eu/ (accessed on 7 July 2021) Address: Bohaterów Warszawy Street, no. 4 | |

| 17 | “Sorrento” holiday house made up of 5 buildings:

|  “Sorrento” holiday house. https://fotopolska.eu/ (accessed on 7 July 2021) Address: Traugutta Street, no. 1 | |

| 18 | “Warszawianka” holiday house made up of 4 buildings:

| No archival photos available Address: Ludowa Street, no. 9 | |

| Niechorze (49 buildings) | 1 | “Błękitna” holiday house made up of 7 buildings:

| No archival photos available Address: East Street, no. 4 |

| 2 | “Liwia” holiday house made up of 2 buildings /administered by WHF/

| No archival photos available Address: Marchlewskiego Street, no. 16 (present: Amber Avenue) | |

| 3 | “Niechorzanka” holiday house made up of 2 buildings:

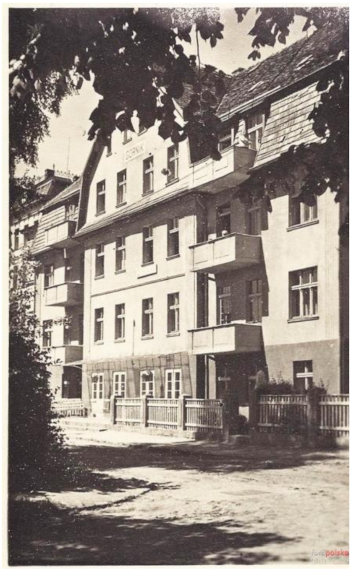

|  “Niechorzanka” holiday house, currently the Museum of Maritime Fishery in Niechorze, between 1960 and 1970. https://fotopolska.eu/ (accessed on 3 May 2021) Address: Wolska Street, no. 8 | |

| 4 | “Rybak” holiday house made up of 6 buildings:

| No archival photos available Address: Morska Street, no. 8 | |

| 5 | “Syrena” holiday house made up of 11 buildings:

| No archival photos available Address: Szczecińska Street, no. 4 | |

| 6 | “Zacisze” holiday house made up of 10 buildings:

|  The dining room of the “Zacisze” WHF’s Holiday House, between 1967 and 1977. Postcard by KAW. https://fotopolska.eu/ (accessed on 12 July 2021) Address: Marchlewskiego Street, no. 20 (present: Amber Avenue) | |

| 7 | “Zielona” holiday house made up of 12 buildings:

|  “Zielona” holiday house—Mewa, 1939. https://fotopolska.eu/ (accessed on 8 July 2021) Address: Krakowska Street, no. 3 | |

| Nowe Śliwno (8 buildings) | 1 | “Oaza” holiday house made up of 8 buildings:

| No archival photos available Address: Nowe Śliwno |

| Pobierowo (337 summer houses,71 camping houses,2 pavilions) | 1 | “Bałtyk” holiday house made up of 34 houses:

|  “Bałtyk” WHF’s Holiday House, between 1976 and 1977. Photo J. Tymiński. Postcard by KAW. https://fotopolska.eu/ (accessed on 3 May 2021) Address: Grunwaldzka Street, no. 25 |

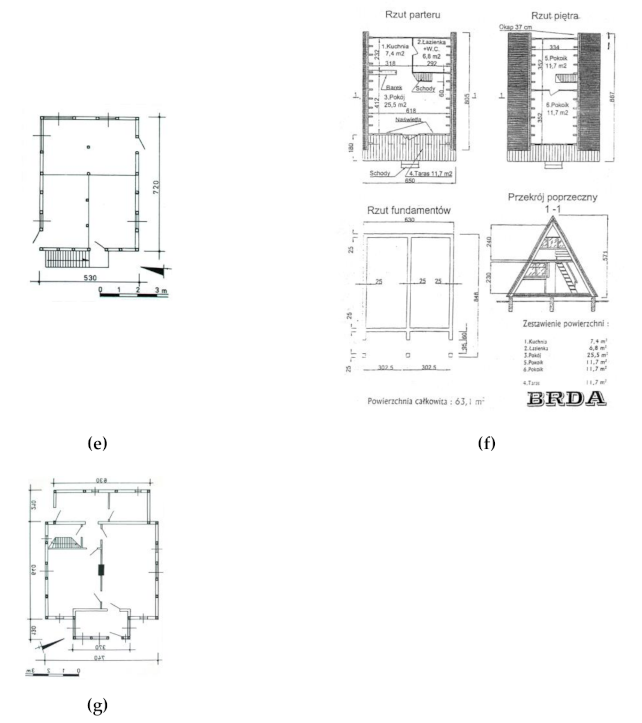

| 2 | “Barbórka” holiday house made up of 57 houses:

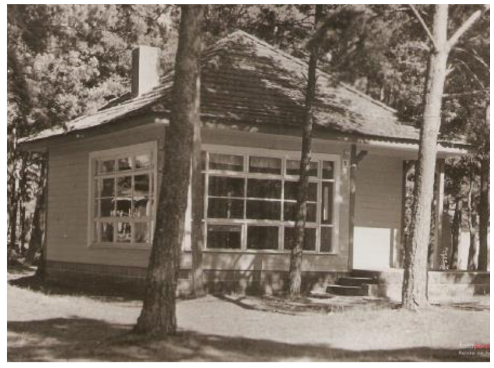

|  Pobierowo. One of the summer houses. https://fotopolska.eu/ (accessed on 8 July 2021) Address: Grunwaldzka Street, no. 7 | |

| 3 | “Bursztyn” holiday house made up of 56 houses:

| No archival photos available Address: Gdańska Street, no. 5 | |

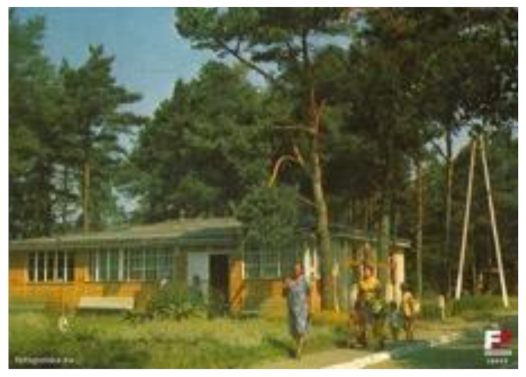

| 4 | “Meduza” holiday house made up of 59 buildings:

|  FWP Meduza. RSW Ruch, 1969. Photo W. Wojtkiewicz. https://fotopolska.eu/ (accessed on 3 May 2021) Address: Grunwaldzka Street, no. 51 | |

| 5 | “Muszla” holiday house made up of 60 buildings:

|  Camping houses, between 1975–1980. https://fotopolska.eu/ (accessed on 8 July 2021) Address: Piastowska Street, no. 29 | |

| 6 | “Słoneczna” holiday house made up of 47 houses:

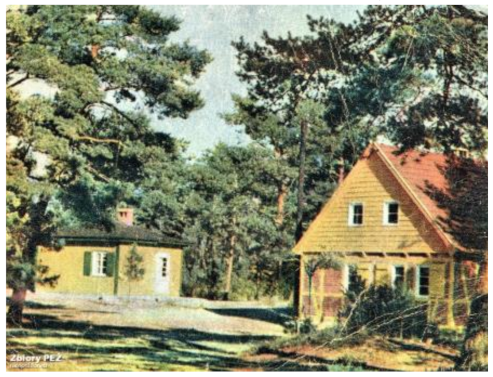

|  Summer houses, between 1959–1960. Photo E. Czapliński i A. Stelmach. Postcard by RUCH. https://fotopolska.eu/ (accessed on 8 July 2021) Address: Pomorska Street, no. 1 | |

| 7 | “Wisła” holiday house made up of 24 houses:

| Address: Grunwaldzka Street, no. 4 | |

| Rewal (31 buildings, 10 pavilions) | 1 | “Gwiazda” holiday house made up of 5 buildings:

|  “Zdrój” holiday house in Rewal.Photo J. Tymiński. Postcard by KAW, 1970–1975. https://fotopolska.eu/ (accessed on 7 June 2021) Address: Saperska Street, no. 6 |

| 2 | “Idylla” holiday house made up of 5 buildings:

|  “Idylla” Holiday House in Rewal, 1960–1970. https://fotopolska.eu/ (accessed on 7 June 2021) Address: Saperska Street, no. 13 | |

| 3 | “Maryla” holiday house made up of 6 buildings:

|  “Maryla” holiday house in Rewal, 1960–1965. https://fotopolska.eu/ (accessed on 3 May 2021) Address: Mickiewicza Street, no. 1 | |

| 4 | “Radość” holiday house made up of 10 buildings:

|  “Radość” Holiday House, 1959–1961. Postcard by Publ. House of Trade-unions CRZZ. Photo M. Holzman. https://fotopolska.eu/ (accessed on 3 May 2021) Address: Westerplatte Defenders Street, no. 12 | |

| 5 | “Strażnica” holiday house made up of 4 buildings:

| No archival photos available Address: Mickiewicza Street | |

Appendix B

| Koszalin District | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Locality | Number | Holiday House | Archive Photo/Address |

| Chłopy (4 buildings) | 1 | “Odra” holiday house made up of 4 buildings:

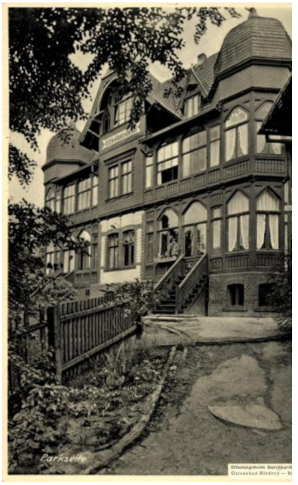

|  The former “Strandschloss” hotel, later “Odra” holiday house. Postcard by Ruch Publishing Office. Between 1960 and 1965, https://fotopolska.eu/ (accessed on 3 May 2021) Address: Sarbinowo, no. 96 |

| Darłówek (7 buildings) | 1 | “Antena” holiday house made up of 7 buildings:

|  “Antena” holiday house. https://fotopolska.eu/ (accessed on 11 June 2021) Address: Kąpielowa Street, no. 11 |

| Jarosławiec (213 summer houses) | 1 | The “Baltic” holiday house made up of summer houses.

|  WHF’s “Bałtyk” centre in Jarosławiec. Between 1970 and 1980. https://fotopolska.eu/(accessed on 3 May 2021) Address: n/a |

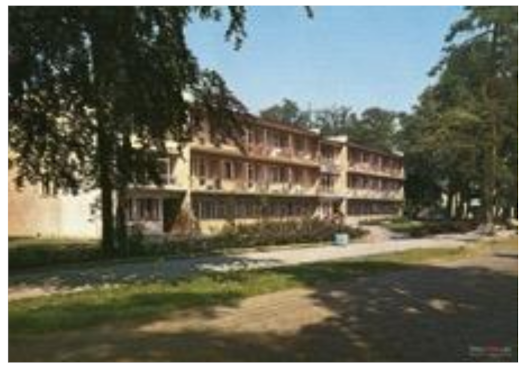

| Kołobrzeg (2 buildings) | 1 | “Bałtyk” Sanatorium and Recreation Centre for Trade Unions, made up of 2 buildings:

|  “Bałtyk” Sanatorium and Recreation Centre, 1976. Photo T. Zagoździński. Postcard by KAW. https://fotopolska.eu/ (accessed on 3 May 2021) Address: Rodziewiczówny Street, no. 1 |

| Mielno (29 buildings) | 1 | “Bandera” holiday house made up of 9 buildings:

|  “Bandera 7” WHF’s Holiday House, Between 1962 and 1964. Postcard by RUCH. https://fotopolska.eu/ (accessed on 5 June 2021) Address: Pionierów Street, no. 16 (building doesn’t exist) |

| 2 | “Dar Pomorza” holiday house made up of 6 buildings:

|  “Dar Pomorza” holiday house in Mielno, between 1950 and 1960, https://fotopolska.eu/ (accessed on 5 June 2021) Address: 1 Maja Street, no. 10 (building doesn’t exist) | |

| 3 | “Jantar” holiday house made up of 3 buildings:

|  “Jantar I” WHF’s Holiday House, between 1958 and 1960. Postcard by RUCH. https://fotopolska.eu/ (accessed on 5 June 2021) Address: B. Chrobrego Street, no. 4 (building does not exist) | |

| 4 | “Perła” holiday house made up of 8 buildings:

| No archival photos available Address: B. Chrobrego Street, no. 43 | |

| 5 | “Jutrzenka” holiday house made up of 3 buildings:

|  “Jutrzenka” WHF’s Holiday House, between 1974 and 1976. Postcard by KAW. https://fotopolska.eu/ (accessed on 5 June 2021) “Jutrzenka” WHF’s Holiday House, between 1974 and 1976. Postcard by KAW. https://fotopolska.eu/ (accessed on 5 June 2021)Address: Nadbrzeżna Street, no. 2 | |

| Sarbinowo (13 buildings) | 1 | “Mewa” holiday house made up of 6 buildings:

|  “Mewa II” WHF’s Holiday House, between 1962 and 1964, Postcard by RUCH. https://fotopolska.eu/ (accessed on 3 May 2021) Address: n/a |

| 2 | “Ślązaczka” holiday house made up of 7 buildings:

| No archival photos available Address: n/a | |

| Ustka (9 buildings, 24 pavilions, 61 summer houses) | 2 | “Czarodziejka” holiday house made up of 5 buildings:

|  “Czarodziejka” holiday house. https://fotopolska.eu/ (accessed on 11 June 2021) Address: Chopina Street, no. 6 |

| 3 | “Celwiskoza” holiday house made up of camping houses

| No archival photos available Address: Wczasowa Street | |

| 4 | “Przystań” holiday house made up of 4 buildings:

|  “Przystań” WHF in Ustka, between 1960 and 1970. https://fotopolska.eu/ (accessed on 3 May 2021) Address: Limanowskiego Street, no. 4 | |

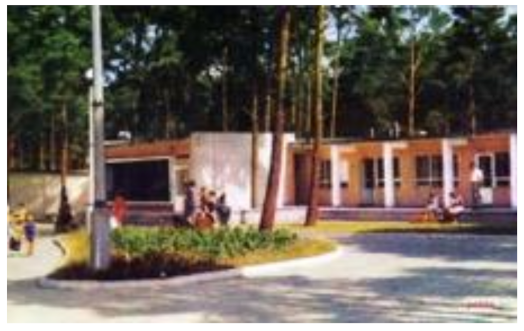

| 5 | “Włókniarz” holiday house made up of 24 pavilions:

|  “Włókniarz” Holiday centre, 1968. Postcard by RUCH. https://fotopolska.eu/ (accessed on 3 May 2021) Address: Wczasowa Street | |

| Ustronie Morskie (26 buildings, 5 pavilions, 22 camping houses) | 1 | “Bałtyk” holiday house made up of 5 buildings:

|  “Bałtyk” holiday house in Ustronie Morskie. https://fotopolska.eu/ (accessed on 3 May 2021) Address: Kościuszki Street, no. 6 |

| 2 | “Fala” holiday house made up of 7 buildings:

|  “Fala” holiday house in Ustronie Morskie, 1964-1966. Postcard RUCH. https://fotopolska.eu/ (accessed on 11 June 2021) Address: Bolesława Chrobrego Street, no. 76 | |

| 3 | “Lublinianka” holiday house made up of 4 buildings:

|  WHF’s Holiday House “Lublinianka 2”, between 1965 and 1967. Postcard by RUCH. https://fotopolska.eu/ (accessed on 12 June 2021) Address: Spokojna Street, no. 1 | |

| 4 | “Marysin” holiday house made up of 5 buildings:

|  WHF’s “Marysin” House in Ustronie Morskie, between 1955 and 1962. Photo E. Czapliński and A. Stelmach. https://fotopolska.eu/ (accessed on 3 May 2021) Address: Bolesława Chrobrego Street, no. 84 | |

| 5 | “Pomorzanka” holiday house made up of 5 buildings:

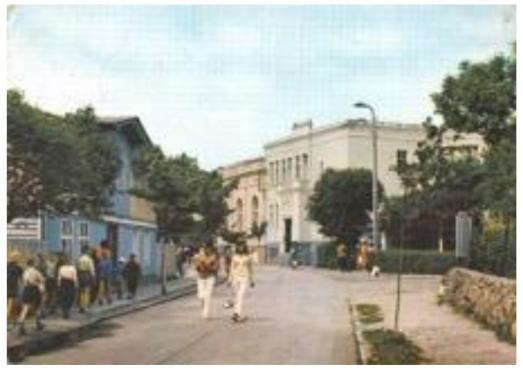

|  Part of a housing estate, the Pomorzanka WHF’s holiday house is in the background, between 1967 and 1968. Photo A. Stelmach. Postcard by RUCH. https://fotopolska.eu/ (accessed on 3 May 2021) Address: Bolesława Chrobrego Street, no. 26 | |

Appendix C

References

- Aman, A. Architecture and Ideology in Eastern Europe during the Stalin Era. An Aspect of Cold War History; The MIT Press: New York, NY, USA, 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Ashworth, G.; Turnbridge, G.J. Dissonant Heritage: The Management of the Past as a Resource in Conflict; John Wiley and Sons: Chichester, UK, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Eckhardt, P. Przestrzeń i architektura jako obraz doktryny politycznej. Przykład państw socjalistycznych (Space and architecture as an expression of political philosophy. The case of socialist countries). Miscell. Historico-Iuridica 2016, 15, 11–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Górawski, B.; Wendt, J.A. Polityczne uwarunkowania kształtowania krajobrazu miasta (Political conditions of shaping the cityscape). J. Innovat. Natural Sci. 2019, 1, 29–35. [Google Scholar]

- Jałowiecki, B. Architektura jako ideologia (Architecture as ideology). Studia Region. Lokalne 2009, 3, 46–59. [Google Scholar]

- Yaneva, A. Five Ways to Make Architecture Political. An Introduction to the Politics of Design Practice; Bloomsbury Academic: London, UK, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Minorski, J. O Polską Architekturę Socjalistyczną. Materiały z Krajowej Partyjnej Narady Architektów, Odbytej w Dniach 20–21.04.1949 roku w Warszawie (For Polish Socialist Architecture. Materials from the National Party Meeting of Architects Held on 20–21.04.1949 in Warsaw); Państwowe Wydawnictwa Techniczne: Warsaw, Poland, 1950. [Google Scholar]

- Kapa-Cichocka, M. MDM—KMA Warszawa—Warschau: Das Architektonische Erbe des Realsozialismus in Warschau. Architektoniczna Spuścizna Socrealizmu w Warszawie; Dom Spotkań z Historią: Warsaw, Poland, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Gliński, A.; Kusztra, Z.; Müller, S. Architektura polska 1944–1984, Lata 1949–1956. Realizm socjalistyczny. Architektura 1984, 2, 65–80. [Google Scholar]

- Gliński, A.; Kusztra, Z.; Müller, S. Architektura polska 1944–1984, Lata 1956–1965. Poszukiwania. Architektura 1984, 3, 65–80. [Google Scholar]

- Jarosz, D. Masy Pracujące Przede Wszystkim. Organizacja Wypoczynku w Polsce 1945–1956 (Working Masses First. Organisation of Leisure in Poland 1945–1956); Akademia Świętokrzyska: Kielce, Poland, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Pisarska, B. Rola wypoczynku socjalnego w Polsce podczas dekady 1970–1980 w świetle literatury [The role of social leisure in Poland during the 1970-1980 decade in the light of literature]. In Dekada Gierka, Wnioski dla Obecnego Okresu Modernizacji Polski; Rybiński, K., Ed.; Uczelnia Vistula: Warsaw, Poland, 2011; pp. 177–192. [Google Scholar]

- Pisarska, B. Zmiany statusu, zarządzania, infrastruktury i ruchu wczasowiczów FWP. In Od Autentyczności do Komercji—O Doświadczaniu w Turystyce, Warsztaty z Geografii Turyzmu; Tanaś, S., Mokras-Grabowska, J., Eds.; Wydawnictwo Uniwersytetu Łódzkiego: Łódź, Poland, 2014; Volume 4, pp. 107–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jarosz, D. Państwowe organizowanie wypoczynku. Fundusz Wczasów Pracowniczych w latach 1945–1956. Polska 1944/45–1989. Studia Materiały 2001, 5, 49–108. Available online: https://rcin.org.pl/Content/59610/WA303_79134_B155-Polska-T-5-2001_Jarosz.pdf. (accessed on 20 February 2021).

- Niezabitowska, E. Metody i Techniki Badawcze w Architekturze (Research Methods and Techniques in Architecture); Wydawnictwo Politechniki Śląskiej: Gliwice, Poland, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Groat, L.; Wang, D. Architectural Research Methods; John Willey & Sons, Inc.: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Worker holidays of WHF. In Informator FWP (Guidebook); Instytut Wydawniczy CRZZ: Warsaw, Poland, 1986.

- Constitution of the People’s Republic of Poland Enacted on July 22, 1952, Dz.U. 1952 nr 33 poz 232. Available online: http://libr.sejm.gov.pl/tek01/txt/kpol/1952a.html (accessed on 20 February 2021).

- Law of March 20, 1950, Amending the Law on Leave for Employees in Industry and Commerce. Dz.U. 1950 nr 13 poz. 123. Available online: http://isap.sejm.gov.pl/isap.nsf/download.xsp/WDU19500130123/O/D19500123.pdf (accessed on 20 February 2021).

- Law of April 29, 1969, on Workers’ Leave of Absence. Dz.U. 1969 nr 12 Poz. 85. Available online: http://isap.sejm.gov.pl/isap.nsf/download.xsp/WDU19690120085/O/D19690085.pdf (accessed on 20 February 2021).

- Bal, W.; Czałczyńska-Podolska, M. The stages of the cultural landscape transformation of seaside resorts in Poland against the background of the evolving nature of tourism. Land 2020, 9, 55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bal, W. Pluralistic trends in development of seaside landscape of Western Pomerania. Urban. Arch. Files 2018, 46, 483–495. Available online: http://yadda.icm.edu.pl/yadda/element/bwmeta1.element.baztech-beca1cc6-0422-4686-9d9d-a10ad350ebef/c/bal_pluralistyczne_30_2018.pdf (accessed on 20 February 2021).

- Worker holidays of WHF. In Informator FWP (Guidebook); Instytut Wydawniczy CRZZ: Warsaw, Poland, 1978.

- Kulczycki, Z. Zarys Historii Turystyki w Polsce (An Outline of the History of Tourism in Poland); Sport i Turystyka: Warsaw, Poland, 1970. [Google Scholar]

- Proniewicz, Z.; Soszyński, W. Dziesięć lat FWP: 1949–1958 w Liczbach i Wykresach (Ten Years of WHF: 1949–1958 in Numbers and Charts); FWP CRZZ: Warszawa, Poland, 1959. [Google Scholar]

- Statute of WHF of the Central Council of Trade Unions, M.P. 1950 Nr 3 Poz. 27. Available online: http://isap.sejm.gov.pl/isap.nsf/download.xsp/WMP19500030027/O/M19500027.pdf (accessed on 10 March 2021).

- Jakubowski, J. Akcja wczasόw na tle wspόłczesnej rzeczywistości polskiej (Vacation action against the background of contemporary Polish reality). Biuletyn Wczasόw 1947, 2. [Google Scholar]

- Central Council of Trade Unions (CRZZ) Department of the Presidency, 406. Resolution of the CRZZ Secretariat of January 13, 1950 on the tasks in the field of workers’ holidays. Archives of the Labour Movement.

- Ciarkowski, B. Recreational architecture at the service of politics—Dissonant heritage of holiday resorts from the era of the People’s Republic of Poland. J. Herit. Conserv. 2017, 49, 19–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sierpiński, J. Wczasy Pracownicze w Polsce Ludowej (Workers’ Holidays in People’s Poland); CRZZ: Warsaw, Poland, 1968. [Google Scholar]

- Law of 4 February 1949 on the Employee Holiday Fund of the Central Commission of Trade Unions in Poland, Dz.U. 1949 nr 9 poz. 48. Available online: http://isap.sejm.gov.pl/isap.nsf/download.xsp/WDU19490090048/O/D19490048.pdf (accessed on 10 March 2021).

- Rogalewska, B. Tendencje Lokalizacyjne Zakładowych Ośrodków Wczasowych w Polsce do 1971 r. (Tendencies in the Location of Recreation Centres Controlled by the Establishments in Poland, until 1971); Instytut Geografii i Przestrzennego Zagospodarowania PAN: Warsaw, Poland, 1978. [Google Scholar]

- Sowiński, P. Wakacje w Polsce Ludowej. Polityka Władz i Ruch Turystyczny 1945–1989 (Vacations in People’s Poland. Government Policy and Tourism 1945–1989); Instytut Studiów Politycznych PAN Wydawnictwo TRIO: Warsaw, Poland, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Cymer, A. Architektura w Polsce 1945–1989 (Architecture in Poland 1945–1989); Narodowy Instytut Architektury i Urbanistyki: Warszawa, Poland, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Resolution No. 402 of the Council of Ministers of December 10, 1963, on Non-Operational Activities of a Social and Welfare Nature of State Enterprises M.P. 1963 Nr 95 Poz. 444. Available online: http://isap.sejm.gov.pl/isap.nsf/download.xsp/WMP19630950444/O/M19630444.pdf (accessed on 10 March 2021).

- Szczerski, A. Cztery Nowoczesności. Teksty o Sztuce i Architekturze Polskiej XX Wieku; Studio wydawnicze DodoEditor: Krakόw, Poland, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Act of 21 April 1988 on the Workers’ Holiday Fund. Dz.U. 1988 nr 11 poz. 84. Available online: http://isap.sejm.gov.pl/isap.nsf/download.xsp/WDU19880110084/O/D19880084.pdf (accessed on 20 March 2021).

- Bal, W.; Dawidowski, R.; Raczyński, M.; Sietnicki, M.; Szymski, A. Architektura Polska lat 1961–1975 na Obszarze Pomorza Zachodniego (Polish Architecture of the Years 1961–1975 in the Area of Western Pomerania); Wyd. Walkowska: Szczecin, Poland, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Thompson, J.B. Ideology and Modern Culture; Political Press: Cambridge, UK, 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Giddens, A. Sociology; Polity Press: Cambridge, UK, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- MacKenzie, I. The idea of ideology. In Political Ideologies: An Introduction; Eccleshal, R., Ed.; Routledge: London, UK, 2003; pp. 1–18. [Google Scholar]

- Hausladen, G. Planning the Development of the Socialist City: The Case of Dubna New Town. Geoforum 1987, 18, 103–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McKenzie, B. Marketing of the dark: “Memento Park” in Budapest. Emerald Emerg. Markets Case Stud. 2011, 1, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tandarić, N.; Watkins, C.; Ives, C.D. Urban planning in socialist Croatia. Croat. Geogr. Bull. 2020, 81, 5–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gawroński, S.; Tworzydło, D.; Bajorek, K.; Łukasz, B. A Relic of Communism, an Architectural Nightmare or a Determinant of the City’s Brand? Media, Political and Architectural Dispute over the Monument to the Revolutionary Act in Rzeszów (Poland). Arts 2021, 10, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ismail, A.S. Architecture as an Expression of Political Ideology; Faculty of Built Environment Universiti Teknologi Malaysia: Johor, Malaysia, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Ismail, A.S.; Zhaharin, E.N. Built Form Properties as Sign and Symbols of Patron Political Ideology. Jurnal Kejuruteraan 2017, 29, 87–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jencks, C. The architectural sign. In Signs, Symbol and Architecture; Broadbent, G., Ed.; John Wiley and Sons: New York, NY, USA, 1980; pp. 71–118. [Google Scholar]

- Edelman, M. Space and The Social Order. Politics Design Symbol. 1978, 32, 2–7. [Google Scholar]

- Lefebvre, H. The Production of Space; Basil Blackwell Ltd.: Oxford, UK, 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Weber, R. On The Aesthetic of Architecture: A Psychological Approach to the Structure and Order of Perceived Architectural Space; Avebury: Aldershot, UK, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Vale, J.L. Architecture, Power and National Identity; Yale University Press: London, UK, 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Thrift, N. Performing cultures in the new economy. In Cultural Economy: Cultural Analysis and Commercial Life; du Gay, P., Pryke, M., Eds.; SAGE Publications Ltd.: London, UK, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Lefebvre, H. Prawo do miasta (The Right to the City). Praktyka Teoretyczna 2012, 5, 183–197. Available online: http://www.praktykateoretyczna.pl/PT_nr5_2012_Logika_sensu/14.Lefebvre.pdf (accessed on 1 November 2021). [CrossRef]

- Jałowiecki, B. Społeczne Wytwarzanie Przestrzeni (Revised Edition) (The Social Production of Space (Revised Edition)); Wydawnictwo Naukowe Scholar: Warsaw, Poland, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Majmurek, J. Architektura PRL: Nie Tylko Polityka. 2018. Available online: https://krytykapolityczna.pl/kultura/czytaj-dalej/architektura-prl-rozmowa-z-anna-cymer-majmurek/ (accessed on 10 May 2021).

- Springer, F. Źle Urodzone (Wrongly Born); Karakter: Warsaw, Poland, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Libicki, B. Turystyka socjalna w Polsce [social tourism in Poland]. In 30 Lat Działalności Funduszu Wczasów Pracowniczych 1949–1979. Osiągnięcia i Perspektywy; Materiały z sympozjum naukowego, Spała 22–24 II 1979; Instytut Wydawniczy CRZZ: Warsaw, Poland, 1980. [Google Scholar]

- Węcławowicz-Bilska, E. Kształt przestrzeni zdrojowiska [The shape of the spa space]. In Architektura Kurortowa; Materiały z ogólnopolskiej konferencji „Architektura kurortowa”, Połczyn Zdrój, 24-25 kwietnia 2009; Szczecin EXPO: Szczecin, Poland, 2009; pp. 29–40. [Google Scholar]

- Węcławowicz-Bilska, E. Polskie uzdrowiska u progu XXI wieku (Polish spas at the turn of the 21st century). In Projektowanie Architektury na Terenach o Szczególnych Walorach Krajobrazowych i Uzdrowiskowych; Bocheński, S., Ed.; Oficyna Wydawnicza Politechniki Wrocławskiej: Wrocław, Poland, 2012; pp. 29–42. [Google Scholar]

- Bal, W.; Czałczyńska-Podolska, M. Assessing Architecture-and-Landscape Integration as a Basis for Evaluating the Impact of Construction Projects on the Cultural Landscape of Tourist Seaside Resorts. Land 2021, 10, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yari, F.; Mansouri, S.; Žurić, J. Political architecture and relation between architecture and power. Int. J. Latest Res. Human. Soc. Sci. 2012, 1, 84–90. [Google Scholar]

| Administrations of Seaside WHF Districts | Number of Holiday Towns | Number of WHF Holiday Houses | The Portion in % of Total Beds in WHF |

|---|---|---|---|

| Międzyzdroje | 5 | 43 | 16.2% |

| Koszalin | 8 | 21 | 10.2% |

| Danzig | 14 | 20 | 5.6% |

| Total | 27 | 84 | 32.0% |

| Types of Facilities | Years of Construction | Architectural Features | Political Importance |

|---|---|---|---|

| Adapted facilities: former villas and guesthouses | the end of the 19th century/early 20th century | representative buildings, inspiration by Renaissance and Classicism, | the manifestation of Polishness in the lands recovered by taking over the post-German property, manifestation of the new political system through extensive access to tourism for working masses |

| villas with bay windows and finesse towers, | |||

| “Swiss style”—synonymous with wooden summer architecture (late 19th century) | |||

| New holiday facilities: sanatoriums | the 1960s and 1970s | Modem form, buildings with distinctive height and compact shape, facilities and rooms of common use (canteen, recreation room) numerous balconies and terraces along each storey | indoctrination by providing a new quality of rest in modern facilities tailored for the new citizen, indoctrination by using the space arrangement (e.g., common canteen) and form (moving away from traditional buildings representing the old order), Propaganda of equality |

| New holiday facilities: pavilion-type development | the 1960s to the 1970s | modern form, horizontal shape, cubic forms, the strip-wise layout of balconies and terraces, common facilities and rooms (canteen, recreation room), functionalism, unified grade, repetition and typification, duplication of solutions | indoctrination by using the space arrangement (e.g., common canteen) and form (moving away from traditional buildings representing the old order), Propaganda of equality |

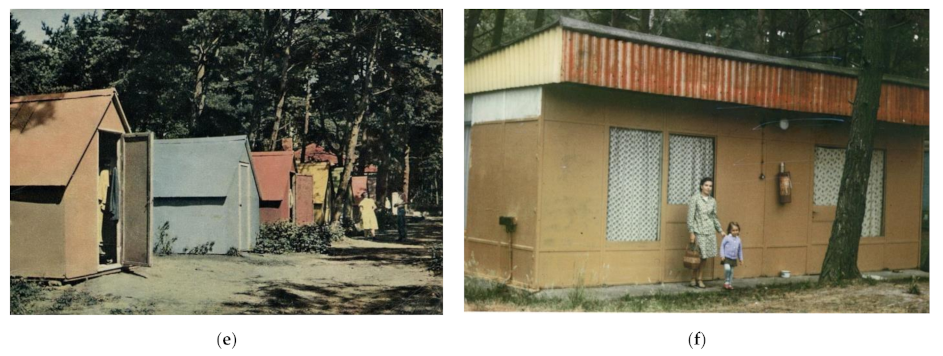

| New holiday facilities: light temporary buildings—summer and camping homes | From the 1950s to the 1980s | complexes of small seasonal cabins, holiday homes and camping sites or terraced housing | propaganda stating that rest was easily accessible to every citizen |

| wooden, cuboid or pyramid-shaped cottages topped with a lean-to or gabled roof |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Bal, W.; Czałczyńska-Podolska, M. Architecture and Recreation as a Political Tool—Seaside Architectural Heritage of the Worker Holiday Fund (WHF) in the Era of the Polish People’s Republic (1949–1989). Sustainability 2022, 14, 171. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14010171

Bal W, Czałczyńska-Podolska M. Architecture and Recreation as a Political Tool—Seaside Architectural Heritage of the Worker Holiday Fund (WHF) in the Era of the Polish People’s Republic (1949–1989). Sustainability. 2022; 14(1):171. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14010171

Chicago/Turabian StyleBal, Wojciech, and Magdalena Czałczyńska-Podolska. 2022. "Architecture and Recreation as a Political Tool—Seaside Architectural Heritage of the Worker Holiday Fund (WHF) in the Era of the Polish People’s Republic (1949–1989)" Sustainability 14, no. 1: 171. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14010171

APA StyleBal, W., & Czałczyńska-Podolska, M. (2022). Architecture and Recreation as a Political Tool—Seaside Architectural Heritage of the Worker Holiday Fund (WHF) in the Era of the Polish People’s Republic (1949–1989). Sustainability, 14(1), 171. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14010171