Great Minds Think Alike, Fools Seldom Differ: An Empirical Analysis of Opportunity Assessment in Technology Entrepreneurs

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

2.1. Opportunity Cost

2.2. Market Assessment

2.3. Financial Analysis

2.4. Connection to the Current Study

3. Methodology

3.1. Sample

3.2. Data Collection Instrument

3.3. Protocols

4. Results

4.1. Opportunity Cost

4.2. Market Assessment

4.2.1. Overall Target Market

4.2.2. Potential Customers

4.2.3. Potential Competitors

4.3. Financial Analysis

5. Discussion

6. Conclusions, Limitations and Further Research

6.1. Limitations

6.2. Future Research

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| Section 1: Demographics | |

|---|---|

| This section aims to capture some general information about you, your entrepreneurial history and your new business. | |

| Variable | Measure |

| Which of the following best describes your gender? | Male |

| Female | |

| Other | |

| How old are you? | <25 |

| 25–54 | |

| ≥54 | |

| How many other businesses have you helped to start as an owner or part-owner? | Open |

| How many other businesses do you currently own or part-own? | Open |

| How many business ideas did you consider before working on your current business idea? | Open |

| What is the current state of the product or service that this new business will sell? | Ready for sale or delivery |

| Prototype or procedure tested with customers | |

| Prototype or procedure being developed | |

| Idea for a business being evaluated | |

| Multiple ideas for a business being evaluated | |

| How many years have you been devoting time to this new business/business idea? | Below 1 |

| 1–2 | |

| 3–5 | |

| 5+ | |

| What industry is your new business in, e.g., finance, medical device, software engineering etc.? | Open |

| Section 2: Opportunity costs | |

| In this context, opportunity cost is the cost of pursuing a new business to alternatives such as alternative choices of employment or other businesses. This section aims to capture information relating to the opportunity cost of this new business to you. | |

| Variable | Measure |

| Why did you become involved in this business? | Take advantage of business opportunity |

| No better choices for work/unemployed | |

| Other | |

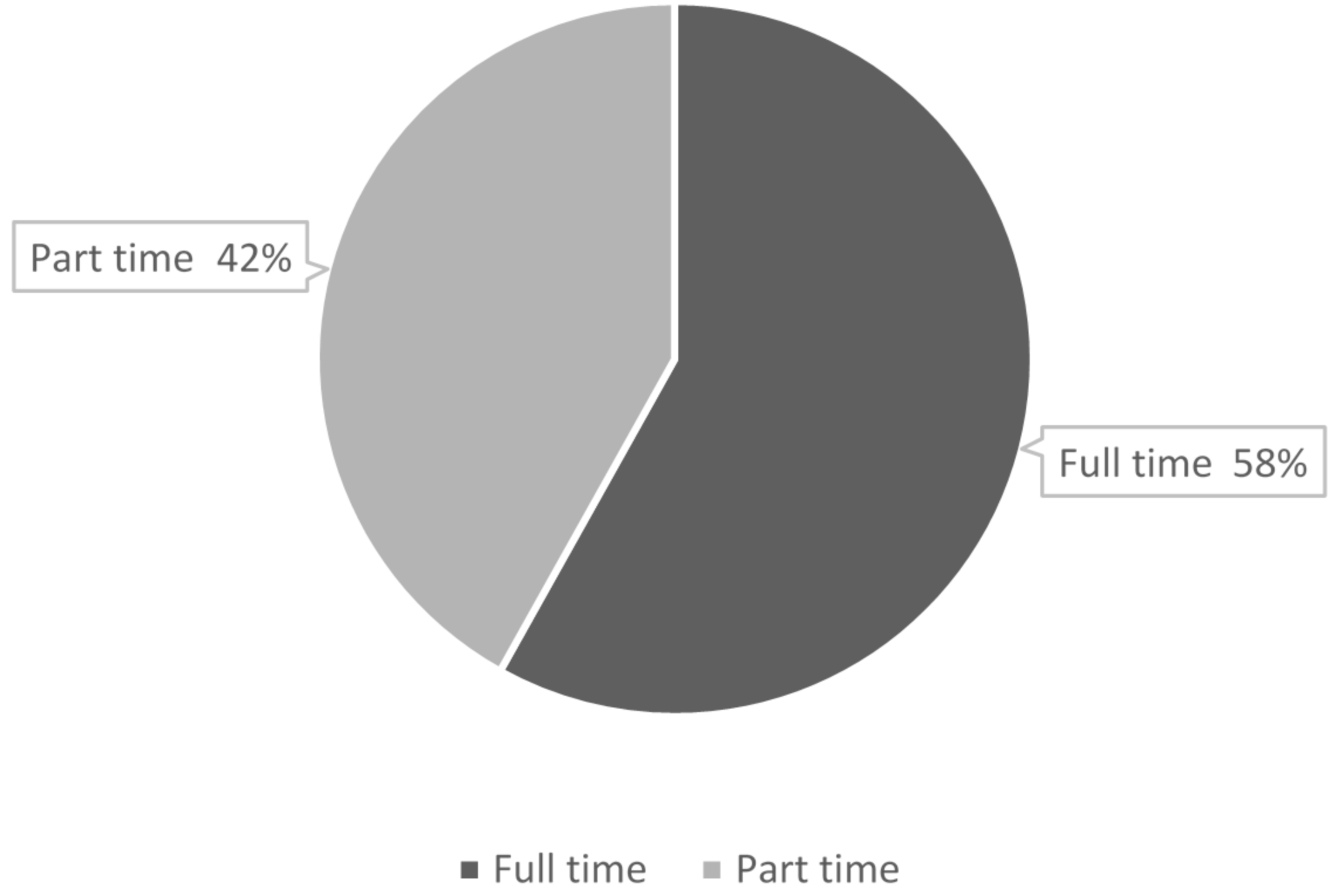

| Are you working on this new business full-time? | Yes |

| No | |

| How would you describe your most recent full time position? | Worker |

| Manager, supervisor or executive | |

| Support staff | |

| Combination of managerial and other staff functions | |

| Owned other business | |

| Other | |

| How many years (have you had/did you have) this position? | Open |

| What is the highest level of education you have completed? | Primary education |

| Junior Certificate | |

| Leaving Certificate | |

| Post Leaving Certificate | |

| Diploma | |

| Degree | |

| Masters/PHD | |

| Have you personally provided financial assistance to the new business, like equity, loans, or loan guarantees to help with this new business? | Yes |

| No | |

| How has this new business affected your current income? | Increased |

| Reduced | |

| No impact | |

| Which one of the following, do you feel is the most important motive for pursuing this business? | Greater independence |

| Increase personal income | |

| Just to maintain income | |

| Other | |

| Section 3: Market evaluation | |

| This section aims to ascertain if market information has influenced the direction of your business/business idea and if so at what stage it began. | |

| Variable | Measure |

| Has a target market been identified for this new business? | Yes |

| No, not yet, will in future | |

| No, not relevant | |

| If yes, what was the state of the product or service when you began identifying the target market? | Ready for sale or delivery |

| Prototype or procedure tested with customers | |

| Prototype or procedure being developed | |

| Idea for a business being evaluated | |

| Multiple ideas for a business being evaluated | |

| Information about the target market has influenced the direction of my business. | Strongly Agree |

| Agree | |

| Somewhat Agree | |

| Strongly Disagree | |

| Disagree | |

| Somewhat Disagree | |

| Has an effort been made to collect information about the competitors of this new business? | Yes |

| No, not yet, will in future | |

| No, not relevant | |

| If yes, what was the state of the product or service when the effort began? | Ready for sale or delivery |

| Prototype or procedure tested with customers | |

| Prototype or procedure being developed | |

| Idea for a business being evaluated | |

| Multiple ideas for a business being evaluated | |

| Information about competitors has influenced the direction of my business. | Strongly Agree |

| Agree | |

| Somewhat Agree | |

| Strongly Disagree | |

| Disagree | |

| Somewhat Disagree | |

| Has an effort been made to talk with potential customers about the product or service of this new business? | Yes |

| No, not yet, will in future | |

| No, not relevant | |

| If yes, what was the state of the product or service when the effort began? | Ready for sale or delivery |

| Prototype or procedure tested with customers | |

| Prototype or procedure being developed | |

| Idea for a business being evaluated | |

| Multiple ideas for a business being evaluated | |

| Information from customers has influenced the direction of my business. | Strongly Agree |

| Agree | |

| Somewhat Agree | |

| Strongly Disagree | |

| Disagree | |

| Somewhat Disagree | |

| I believe I understand the needs of my target customer. | Strongly Agree |

| Agree | |

| Somewhat Agree | |

| Strongly Disagree | |

| Disagree | |

| Somewhat Disagree | |

| I believe my new product or service will be value for money. | Strongly Agree |

| Agree | |

| Somewhat Agree | |

| Strongly Disagree | |

| Disagree | |

| Somewhat Disagree | |

| I believe customers will pay for my new product or service. | Strongly Agree |

| Agree | |

| Somewhat Agree | |

| Strongly Disagree | |

| Disagree | |

| Somewhat Disagree | |

| Section 4 Financial analysis | |

| This section aims to ascertain how financial information has influenced the direction of your business and if so at what stage it began. | |

| Variable | Measure |

| Have financial projections, such as projected income or cash flow statements or break-even analyses, been developed? | Yes |

| No, not yet, will in future | |

| No, not relevant | |

| If yes, what was the state of the product or service when the effort began? | Ready for sale or delivery |

| Prototype or procedure tested with customers | |

| Prototype or procedure being developed | |

| Idea for a business being evaluated | |

| Multiple ideas for a business being evaluated | |

| Information from financial projections has influenced the direction of my business. | Strongly Agree |

| Agree | |

| Somewhat Agree | |

| Strongly Disagree | |

| Disagree | |

| Somewhat Disagree | |

| Have financial statements such as monthly or end of year accounts been prepared for this business? | Yes |

| No, not yet, will in future | |

| No, not relevant | |

| If yes, what was the state of the product or service when the effort began? | Ready for sale or delivery |

| Prototype or procedure tested with customers | |

| Prototype or procedure being developed | |

| Idea for a business being evaluated | |

| Multiple ideas for a business being evaluated | |

| Information from financial statements have influenced the direction of my business. | Strongly Agree |

| Agree | |

| Somewhat Agree | |

| Strongly Disagree | |

| Disagree | |

| Somewhat Disagree | |

| I know how much money/capital my business needs to survive for the next 12 months. | Strongly Agree |

| Agree | |

| Somewhat Agree | |

| Strongly Disagree | |

| Disagree | |

| Somewhat Disagree | |

| How do you intend to ensure your new business will have enough money/capital to survive for the next 12 months? | The business already has enough money/capital for the next 12 months. |

| Generate positive cash flow (income greater than expenditure) | |

| Seek investment | |

| Don’t know | |

| Other | |

References

- Muller, P.; Julius, J.; Herr, D.; Koch, L.; Peycheva, V.; McKiernan, S.; Hope, K. Annual report on European SMEs 2016/2017: Focus on self-employment. Luxemb. Publ. Off. 2017, 1–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- OECD. Strengthening SMEs and Entrepreneurship for Productivity and Inclusive Growth. Available online: https://www.oecd.org/cfe/smes/ministerial/documents/2018-SME-Ministerial-Conference-Key-Issues.pdf (accessed on 15 November 2021).

- Cassar, G. Financial Statement and Projection Preparation in Start-Up Ventures. Account. Rev. 2009, 84, 27–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arora, P.; Haynie, J.M.; Laurence, G.A. Counterfactual Thinking and Entrepreneurial Self–Efficacy: The Moderating Role of Self–Esteem and Dispositional Affect. Entrep. Theory Pr. 2013, 37, 359–385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Astebro, T. Key Success Factors for Technological Entrepreneurs’ R&D Projects. IEEE Trans. Eng. Manag. 2004, 51, 314–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bird, B.; Schjoedt, L.; Baum, J.R. Editor’s Introduction. Entrepreneurs’ Behavior: Elucidation and Measurement. Entrep. Theory Pr. 2012, 36, 889–913. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, Y.R.; Shepherd, D.A. Entrepreneurs’ Decisions to Exploit Opportunities. J. Manag. 2004, 30, 377–395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corbett, A.C.; Hmieleski, K.M. The Conflicting Cognitions of Corporate Entrepreneurs. Entrep. Theory Pract. 2007, 31, 103–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dew, N.; Read, S.; Sarasvathy, S.D.; Wiltbank, R. Effectual versus predictive logics in entrepreneurial decision-making: Differences between experts and novices. J. Bus. Ventur. 2009, 24, 287–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Mueller, S.; Volery, T.; von Siemens, B. What Do Entrepreneurs Actually Do? An Observational Study of Entrepreneurs’ Everyday Behavior in the Start–Up and Growth Stages. Entrep. Theory Pract. 2012, 36, 995–1017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cassar, G. Industry and startup experience on entrepreneur forecast performance in new firms. J. Bus. Ventur. 2014, 29, 137–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, Y.R.; Lévesque, M.; Shepherd, D.A. When should entrepreneurs expedite or delay opportunity exploitation? J. Bus. Ventur. 2008, 23, 333–355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moroz, P.W.; Hindle, K. Entrepreneurship as a Process: Toward Harmonizing Multiple Perspectives. Entrep. Theory Pract. 2012, 36, 781–818. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shane, S.; Venkataraman, S. The Promise of Enterpreneurship as a Field of Research. Acad. Manag. Rev. 2000, 25, 217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Canakoglu, E.; Erzurumlu, S.S.; Erzurumlu, Y.O. How Data-Driven Entrepreneur Analyzes Imperfect Information for Business Opportunity Evaluation. IEEE Trans. Eng. Manag. 2018, 65, 604–617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dimov, D. Nascent Entrepreneurs and Venture Emergence: Opportunity Confidence, Human Capital, and Early Planning: Nascent Entrepreneurs and Venture Emergence. J. Manag. Stud. 2010, 47, 1123–1153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hill, S.A.; Birkinshaw, J.M. Idea Sets: Conceptualizing and Measuring a New Unit of Analysis in Entrepreneurship Research. Organ. Res. Methods 2010, 13, 85–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keh, H.T.; Der Foo, M.; Lim, B.C. Opportunity Evaluation under Risky Conditions: The Cognitive Processes of Entrepreneurs. Entrep. Theory Pract. 2002, 27, 125–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ward, T.B. Cognition, creativity, and entrepreneurship. J. Bus. Ventur. 2004, 19, 173–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Welpe, I.M.; Spörrle, M.; Grichnik, D.; Michl, T.; Audretsch, D.B. Emotions and Opportunities: The Interplay of Opportunity Evaluation, Fear, Joy, and Anger as Antecedent of Entrepreneurial Exploitation. Entrep. Theory Pract. 2012, 36, 69–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yasir, N.; Mahmood, N.; Mehmood, H.S.; Rashid, O.; Liren, A. The Integrated Role of Personal Values and Theory of Planned Behavior to Form a Sustainable Entrepreneurial Intention. Sustainability 2021, 13, 9249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dorcas, K.D.; Celestin, B.N.; Yunfei, S. Entrepreneurs Traits/Characteristics and Innovation Performance of Waste Recycling Start-Ups in Ghana: An Application of the Upper Echelons Theory among SEED Award Winners. Sustainability 2021, 13, 5794. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khazami, N.; Lakner, Z. Influence of Social Capital, Social Motivation and Functional Competencies of Entrepreneurs on Agritourism Business: Rural Lodges. Sustainability 2021, 13, 8641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palich, L.E.; Ray Bagby, D. Using cognitive theory to explain entrepreneurial risk-taking: Challenging conventional wisdom. J. Bus. Ventur. 1995, 10, 425–438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baron, R.A. Counterfactual thinking and venture formation. J. Bus. Ventur. 2000, 15, 79–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dane, E.; Pratt, M.G. Exploring Intuition and its Role in Managerial Decision Making. Acad. Manag. Rev. 2007, 32, 33–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Corbett, A.C. Experiential Learning within the Process of Opportunity Identification and Exploitation. Entrep. Theory Pract. 2005, 29, 473–491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schoonmaker, M.; Carayannis, E.; Rau, P. The role of marketing activities in the fuzzy front end of innovation: A study of the biotech industry. J. Technol. Transf. 2013, 38, 850–872. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, P.; Keister, L. If I Were Rich? The Impact of Financial and Human Capital on Becoming a Nascent Entrepreneur. 2003. Available online: https://www.semanticscholar.org/paper/If-I-Were-Rich-The-Impact-of-Financial-and-Human-on-Kim-Keister/cd0e1c48ddddf0efbd459c12aa23a757c9992d8b (accessed on 15 November 2021).

- Cassar, G.; Craig, J. An investigation of hindsight bias in nascent venture activity. J. Bus. Ventur. 2009, 24, 149–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Gartner, W.; Starr, J.; Bhat, S. Predicting new venture survival. J. Bus. Ventur. 1999, 14, 215–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ardichvili, A.; Cardozo, R.; Ray, S. A theory of entrepreneurial opportunity identification and development. J. Bus. Ventur. 2003, 18, 105–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cassar, G. Entrepreneur opportunity costs and intended venture growth. J. Bus. Ventur. 2006, 21, 610–632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dyer, W.G. Toward a Theory of Entrepreneurial Careers. Entrep. Theory Pract. 1995, 19, 7–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Folta, T.B.; O’Brien, J.P. Entry in the presence of dueling options. Strateg. Manag. J. 2004, 25, 121–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Ravina-Ripoll, R.; Foncubierta-Rodríguez, M.-J.; Ahumada-Tello, E.; Tobar-Pesantez, L.B. Does Entrepreneurship Make You Happier? A Comparative Analysis between Entrepreneurs and Wage Earners. Sustainability 2021, 13, 9997. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haynie, J.M.; Shepherd, D.A.; McMullen, J.S. An Opportunity for Me? The Role of Resources in Opportunity Evaluation Decisions. J. Manag. Stud. 2009, 46, 337–361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mazzarol, T.; Volery, T.; Doss, N.; Thein, V. Factors influencing small business start-ups: A comparison with previous research. Int. J. Entrep. Behav. Res. 1999, 5, 48–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amit, R.; MacCrimmon, K.R.; Zietsma, C.; Oesch, J.M. Does money matter? J. Bus. Ventur. 2001, 16, 119–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amit, R.; Muller, E.; Cockburn, I. Opportunity costs and entrepreneurial activity. J. Bus. Ventur. 1995, 10, 95–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arora, A.; Nandkumar, A. Cash-Out or Flame-Out! Opportunity Cost and Entrepreneurial Strategy: Theory, and Evidence from the Information Security Industry; National Bureau of Economic Research: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2009; p. w15532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hormiga, E.; Hancock, C.; Valls-Pasola, J. The relationship between employee propensity to innovate and their decision to create a company. Manag. Decis. 2013, 51, 938–953. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Cohen, W.M. Fifty years of empirical studies of innovative activity and performance. In Handbook of the Economics of Innovation; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2010; Volume 1, pp. 129–213. ISBN 978-0-444-51995-5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cressy, R. Credit rationing or entrepreneurial risk aversion? An alternative explanation for the Evans and Jovanovic finding. Econ. Lett. 2000, 66, 235–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Colombo, M.G.; Grilli, L. Founders’ human capital and the growth of new technology-based firms: A competence-based view. Res. Policy 2005, 34, 795–816. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gill, A.; Gurău, C.; Dana, L.P.; Sánchez, C.R. Human capital, financial strategy and small firm performance: A study of Canadian entrepreneurs. Int. J. Entrep. Small Bus. 2017, 31, 492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- BarNir, A. Pre-venture managerial experience and new venture innovation: An opportunity costs perspective. Manag. Decis. 2014, 52, 1981–2001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caliendo, M.; Fossen, F.; Kritikos, A.S. Personality characteristics and the decisions to become and stay self-employed. Small Bus. Econ. 2014, 42, 787–814. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davidsson, P.; Honig, B. The role of social and human capital among nascent entrepreneurs. J. Bus. Ventur. 2003, 18, 301–331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Hellmann, T. The Role of Patents for Bridging the Science to Market. Gap; National Bureau of Economic Research: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2005; p. w11460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kickul, J.; Gundry, L. Prospecting for Strategic Advantage: The Proactive Entrepreneurial Personality and Small Firm Innovation. J. Small Bus. Manag. 2002, 40, 85–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodenbach, M.; Brettel, M. CEO experience as micro-level origin of dynamic capabilities. Manag. Decis. 2012, 50, 611–634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baron, R.A.; Ensley, M.D. Opportunity Recognition as the Detection of Meaningful Patterns: Evidence from Comparisons of Novice and Experienced Entrepreneurs. Manag. Sci. 2006, 52, 1331–1344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- McGrath, R.G.; MacMillan, I.C. The Entrepreneurial Mindset: Strategies for Continuously Creating Opportunity in an Age of Uncertainty; Harvard Business School Press: Boston, MA, USA, 2000; ISBN 978-0-87584-834-1. [Google Scholar]

- Parker, S.C. Learning about the unknown: How fast do entrepreneurs adjust their beliefs? J. Bus. Ventur. 2006, 21, 1–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ronstadt, R. The Corridor Principle. J. Bus. Ventur. 1988, 3, 31–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wiklund, J.; Shepherd, D. Aspiring for, and Achieving Growth: The Moderating Role of Resources and Opportunities*. J. Manag. Stud. 2003, 40, 1919–1941. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clement, M.B. Analyst forecast accuracy: Do ability, resources, and portfolio complexity matter? J. Account. Econ. 1999, 27, 285–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mikhail, M.B.; Walther, B.R.; Willis, R.H. Do Security Analysts Improve Their Performance with Experience? J. Account. Res. 1997, 35, 131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Del Campo Villares, M.O.; Miguéns-Refojo, V.; Ferreiro-Seoane, F.J. Business Survival and the Influence of Innovation on Entrepreneurs in Business Incubators. Sustainability 2020, 12, 6197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonner, S.E.; Lewis, B.L. Determinants of Auditor Expertise. J. Account. Res. 1990, 28, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clement, M.B.; Koonce, L.; Lopez, T.J. The roles of task-specific forecasting experience and innate ability in understanding analyst forecasting performance. J. Account. Econ. 2007, 44, 378–398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jacob, J.; Lys, T.Z.; Neale, M.A. Expertise in forecasting performance of security analysts. J. Account. Econ. 1999, 28, 51–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Camerer, C.; Lovallo, D. Overconfidence and Excess Entry: An Experimental Approach. Am. Econ. Rev. 1999, 89, 306–318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Wright, W.F. Task Experience as a Predictor of Superior Loan Loss Judgments. Audit. J. Pract. Theory 2001, 20, 147–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hogarth, R.M. Judgement and Choice: The Psychology of Decision, 2nd ed.; Wiley: Chichester, UK, 1994; ISBN 978-0-471-91479-2. [Google Scholar]

- Kahneman, D.; Lovallo, D. Timid Choices and Bold Forecasts: A Cognitive Perspective on Risk Taking. Manag. Sci. 1993, 39, 17–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sexton, D.L.; Upton, N.B.; Wacholtz, L.E.; McDougall, P.P. Learning needs of growth-oriented entrepreneurs. J. Bus. Ventur. 1997, 12, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raffiee, J.; Feng, J. Should I Quit My Day Job?: A Hybrid Path to Entrepreneurship. Acad. Manag. J. 2014, 57, 936–963. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Sahut, J.-M.; Peris-Ortiz, M. Small business, innovation, and entrepreneurship. Small Bus. Econ. 2014, 42, 663–668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gartner, W.B.; Frid, C.J.; Alexander, J.C. Financing the emerging firm. Small Bus. Econ. 2012, 39, 745–761. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmidt, J.B.; Sarangee, K.R.; Montoya, M.M. Exploring New Product Development Project Review Practices. J. Prod. Innov. Manag. 2009, 26, 520–535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rice, M.P. Co-production of business assistance in business incubators: An exploratory study. J. Bus. Ventur. 2002, 17, 163–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boeker, W. Strategic Change: The Effects of Founding And History. Acad. Manag. J. 1989, 32, 489–515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agarwal, S.; Ramaswami, S.N. Choice of Foreign Market Entry Mode: Impact of Ownership, Location and Internalization Factors. J. Int. Bus. Stud. 1992, 23, 1–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Javalgi, R.G.; Griffith, D.A.; Steven White, D. An empirical examination of factors influencing the internationalization of service firms. J. Serv. Mark. 2003, 17, 185–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhide, A. The hidden costs of stock market liquidity. J. Financ. Econ. 1993, 34, 31–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ortega, M.J.R. Competitive strategies and firm performance: Technological capabilities’ moderating roles. J. Bus. Res. 2010, 63, 1273–1281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schoonhoven, C.B.; Eisenhardt, K.M.; Lyman, K. Speeding Products to Market: Waiting Time to First Product Introduction in New Firms. Adm. Sci. Q. 1990, 35, 177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Westhead, P.; Ucbasaran, D.; Wright, M. Experience and Cognition: Do Novice, Serial and Portfolio Entrepreneurs Differ? Int. Small Bus. J. Res. Entrep. 2005, 23, 72–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Shane, S. Prior Knowledge and the Discovery of Entrepreneurial Opportunities. Organ. Sci. 2000, 11, 448–469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Groves, K.; Vance, C.; Choi, D. Examining Entrepreneurial Cognition: An Occupational Analysis of Balanced Linear and Nonlinear Thinking and Entrepreneurship Success. J. Small Bus. Manag. 2011, 49, 438–466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dimov, D. Grappling with the Unbearable Elusiveness of Entrepreneurial Opportunities. Entrep. Theory Pract. 2011, 35, 57–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cowley, L. Telecoms: Still Suffering from Sector Blues. Eur. Ventur. Cap. J. 2002, 96, 27. [Google Scholar]

- Nasution, H.N.; Mavondo, F.T.; Matanda, M.J.; Ndubisi, N.O. Entrepreneurship: Its relationship with market orientation and learning orientation and as antecedents to innovation and customer value. Ind. Mark. Manag. 2011, 40, 336–345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Slater, S.F.; Narver, J.C. Market Orientation and the Learning Organization. J. Mark. 1995, 59, 63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shane, S. Technological Opportunities and New Firm Creation. Manag. Sci. 2001, 47, 205–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Schiff, A.; Hammer, S.; Das, M. A financial feasibility test for aspiring entrepreneurs. Entrep. Exec. 2010, 15, 33–38. [Google Scholar]

- Zimmerman, M.A.; Zeitz, G.J. Beyond Survival: Achieving New Venture Growth by Building Legitimacy. Acad. Manag. Rev. 2002, 27, 414–431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Armor, D.A.; Sackett, A.M. Accuracy, error, and bias in predictions for real versus hypothetical events. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 2006, 91, 583–600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Ou, C.; Haynes, G.W. Acquisition of Additional Equity Capital by Small Firms—Findings from the National Survey of Small Business Finances. Small Bus. Econ. 2006, 27, 157–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verheul, I.; Thurik, R. Start-Up Capital: “Does Gender Matter? ” Small Bus. Econ. 2001, 16, 329–346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nielsen, K. Human capital and new venture performance: The industry choice and performance of academic entrepreneurs. J. Technol. Transf. 2015, 40, 453–474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pinsonneault, A.; Kraemer, K. Survey Research Methodology in Management Information Systems: An Assessment. J. Manag. Inf. Syst. 1993, 10, 75–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Creswell, J.W. Research Design: Qualitative, Quantitative, and Mixed Methods Approaches, 4th ed.; SAGE Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2014; ISBN 978-1-4522-2609-5. [Google Scholar]

- Venkatesh, A.; Vitalari, N. Longitudinal Surveys in Information Systems Research: An Examination of Issues, Methods, and Applications. Inf. Syst. Chall. Surv. Res. Methods 1991, 1, 115–144. [Google Scholar]

- Fukugawa, N. Human capital management at incubators successful in new firm creation: Evidence from Japan. Int. J. Entrep. Small Bus. 2018, 35, 538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teclaw, R.; Price, M.C.; Osatuke, K. Demographic Question Placement: Effect on Item Response Rates and Means of a Veterans Health Administration Survey. J. Bus. Psychol. 2012, 27, 281–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, J.F. Multivariate Data Analysis, 7th ed.; Pearson: Harlow, UK, 2014; ISBN 978-1-292-02190-4. [Google Scholar]

- Pallant, J. SPSS Survival Manual: A Step by Step Guide to Data Analysis Using SPSS, 4th ed.; Open University Press: Maidenhead, UK, 2010; ISBN 978-0-335-24239-9. [Google Scholar]

- Cheraghi, M. Young entrepreneurs pushed by necessity and pulled by opportunity: Institutional embeddedness in economy and culture. Int. J. Entrep. Small Bus. 2017, 30, 395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robichaud, Y.; Zinger, J.T.; LeBrasseur, R. Gender differences within early stage and established small enterprises: An exploratory study. Int. Entrep. Manag. J. 2007, 3, 323–343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noorderhaven, N.; Thurik, R.; Wennekers, S.; van Stel, A. The Role of Dissatisfaction and per Capita Income in Explaining Self–Employment across 15 European Countries. Entrep. Theory Pract. 2004, 28, 447–466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Congregado, E.; Golpe, A.A.; Parker, S.C. The dynamics of entrepreneurship: Hysteresis, business cycles and government policy. Empir. Econ. 2012, 43, 1239–1261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Folta, T.B.; Delmar, F.; Wennberg, K. Hybrid Entrepreneurship. Manag. Sci. 2010, 56, 253–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Wennekers, S.; van Wennekers, A.; Thurik, R.; Reynolds, P. Nascent Entrepreneurship and the Level of Economic Development. Small Bus. Econ. 2005, 24, 293–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

| Dimension | Consideration | Reference |

|---|---|---|

| Extent to which an entrepreneur has choices | The cost incurred versus alternative choices, specific to the individual, where the lower the cost, the more likely to pursue entrepreneurship | [14,20,33] |

| Full-time versus part-time | Part-time or hybrid entrepreneurship can reduce financial uncertainty | [34,35,69] |

| Level of human capital | Individuals with greater human capital incur a greater opportunity cost | [16,29,33] |

| Employment and education history | Work experience and high education levels may promote successful entrepreneurship | [11,29,35,70] |

| Liquidity and economic risk | Entrepreneurs incur financial costs in terms of income foregone in financing the business and risk in guaranteeing debts and loans | [33,38,44,71] |

| Dimension | Consideration | Reference |

|---|---|---|

| Evaluation of an opportunity | Begins with an informal market investigation, becoming more formal as the likelihood of exploitation increases | [12,15,32,83,84] |

| The more defensible a market position, the more attractive the opportunity | ||

| Evaluation of market opportunities | Identifying more potential markets to provide a choice of the market to pursue | [9,15] |

| Evaluation of customer value | Must be market-orientated to create superior customer value | [7,84,85,86] |

| Evaluation of competition | At a threshold, need to cease evaluation and action the exploitation in order to gain a first-mover advantage before the competition learns to compete | [12,27,83] |

| Evaluation of exploitation decision | Exploitation is more likely when the entrepreneur perceives more knowledge of customer demand for the opportunity | [7,12,14] |

| Dimension | Consideration | Reference |

|---|---|---|

| Evaluation of current financial position and performance | Financial statements are a communication tool for investors where the frequency of preparation reflects minimum evaluation interval | [3,7,16,28,29] |

| Evaluation of an opportunity | Focus is on opportunities with the ability to generate positive cash flow | [14,16,53] |

| Evaluation of market opportunities | Entrepreneurs only invest what they can afford to lose | [7,9,37] |

| New business evaluation/financial projections | Industry experience is associated with more accurate forecasts | [11,38] |

| Importance of finance | Financial resources are critical to early new venture development | [3,28,29] |

| Importance of previous experience | Higher levels of education and net worth associated with a greater likelihood of external funding | [71,93] |

| Dimension | Category | Number (n = 88) | Percent (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | Male | 70 | 79.5% |

| Female | 18 | 20.5% | |

| Age | <25 | 6 | 6.8% |

| 25–54 | 78 | 88.6% | |

| ≥54 | 4 | 4.6% | |

| # Previous businesses | 0 | 26 | 29.5% |

| 1 | 34 | 38.6% | |

| ≥2 | 26 | 29.5% | |

| # Current businesses | 0 | 31 | 35.2% |

| 1 | 48 | 54.5% | |

| ≥2 | 9 | 10.2% | |

| Status of current business | Evaluation | 63 | 71.6% |

| Exploitation | 25 | 28.4% | |

| Years working in the current business | <2 years | 69 | 78.4% |

| ≥2 years | 19 | 21.6% |

| Dimension | Level | Number (n = 88) | Percent (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Recent role | Managerial|supervisory | 22 | 51% |

| Business owner | 13 | 30% | |

| Worker|support | 7 | 17% | |

| Student | 1 | 2% | |

| Education level | PhD|MSc | 16 | 37% |

| Degree [B.A., B.Sc., B.Eng.] | 13 | 30% | |

| Other 3rd level [e.g., Diploma] | 11 | 26% | |

| 2nd level [e.g., Baccalaureate] | 3 | 7% |

| Part-Time | Full-Time | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Timing of target market identification | Ideas stage | 27 | 75% | 20 | 40% |

| Prototype stage | 5 | 14% | 22 | 44% | |

| Market ready stage | 4 | 11% | 8 | 16% | |

| Ideas stage | 27 | 75% | 20 | 40% | |

| Timing of gathering competitor information | Irrelevant | 3 | 8% | - | - |

| Ideas stage | 21 | 58% | 26 | 52% | |

| Prototype stage | 5 | 14% | 18 | 36% | |

| Market ready stage | 7 | 20% | 6 | 12% | |

| Confidence in understanding customer needs | No | 1 | 3% | 2 | 4% |

| Yes | 35 | 97% | 48 | 96% | |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Barry, P.; Cormican, K.; Browne, S. Great Minds Think Alike, Fools Seldom Differ: An Empirical Analysis of Opportunity Assessment in Technology Entrepreneurs. Sustainability 2022, 14, 49. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14010049

Barry P, Cormican K, Browne S. Great Minds Think Alike, Fools Seldom Differ: An Empirical Analysis of Opportunity Assessment in Technology Entrepreneurs. Sustainability. 2022; 14(1):49. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14010049

Chicago/Turabian StyleBarry, Patrick, Kathryn Cormican, and Sean Browne. 2022. "Great Minds Think Alike, Fools Seldom Differ: An Empirical Analysis of Opportunity Assessment in Technology Entrepreneurs" Sustainability 14, no. 1: 49. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14010049