Abstract

The aim of this study was (a) to investigate the relationship between destination personality (DP), destination image (DI), self-congruity (SC), and behavioral intention (BI) in the context of golf tourism and (b) to examine the mediating roles of DI and SC in the relationship between DP and BI. We collected valid data about 519 golf tourists who visited Hainan, China in 2021. The results show that DP positively affected DI, DP positively affected BI, DP positively affected SC, SC positively affected BI, and DI positively affected BI. In addition, DI positively mediated the relationship between DP and BI, and SC positively mediated the relationship between DP and BI. The findings enrich the tourism literature, contribute to the exploration of golf tourism theory, and provide recommendations for golf tourism researchers and marketers.

1. Introduction

The COVID-19 outbreak might be the biggest market shock the sports world has ever faced. Although golf is an outdoor sport, it did not escape the lockdown, which affected golf clubs and regular golf tourists the most [1]. Golf courses are among the most expensive facilities for mass sports participation, with fixed costs of maintenance often exceeding 50% of total expenses [2]. According to preliminary estimates, the lockdown would lead to economic losses of around $1200 per day [3]. Given the tight economic conditions for many golf clubs, it is critical to identify factors that can contribute to the sustainability of golf tourism destinations in the context of COVID-19.

The tourism trend in a crisis situation of an infectious disease such as COVID-19 is changing in a direction to satisfy the desire for tourism while reducing the risk of infectious diseases through small-scale experiential tourism such as golf in a clean natural environment. Sustainable golf tourism refers to community-centered development so that the effects of golf tourism can be continuously realized through the conservation of resources in the Hainan region and the harmony of local culture and tourism industry. In order to successfully implement this, it is necessary to understand and agree on the conservation and development of tourism resources by both stakeholders and tourists. The sustainability of a tourist destination is a lasting virtuous cycle that can maintain a good tourism ecology, economic environment and sustainability of the social structure under the premise of the active participation of stakeholders such as residents, tourists, operators, governments, etc. Visitors are key stakeholders in keeping a destination sustainable. Whether a destination can attract tourists and make tourists have travel behavior intentions directly determines the success or failure of a tourist destination. Therefore, the behavioral intention of tourists is the fundamental factor affecting the sustainable development of tourist destinations. BI is an assessment of a tourist’s desire to return to the same destination or to recommend that destination to others [4]. Attention to the measurement and assessment of BI is one way to keep a destination sustainable [5].

Hainan Province in southern China is an important golf tourism destination due to its favorable geographical location and weather conditions [6]. According to The People’s Government of Hainan Province (2016), Hainan Province attracts more than 1 million golfers annually, with more than 2 million rounds sold and $25 billion in exchanges [6]. Golf tourism has become one of the most important pillars to promote the development of Hainan Province. Golf tourism has become one of the most important pillars to promote the development of Hainan Province. The 2020 Amateur Golf Premier League qualifiers held in Hainan included 19 league clubs across the country, 285 teams, and 8000 participants. This improvement over previous years [7] suggests that the COVID-19 outbreak did not lower the enthusiasm of the participants, providing an ideal subject for this study. Golf tourists refer to Hainan Island as the “Hawaii of Asia”. This phrase has produced a good brand effect, making the golf destination in Hainan stand out, enhancing its market competitiveness, and attracting tourists. Whether this brand effect is sustainable during the COVID-19 pandemic is unclear.

Pasquinelli et al. [8] pointed out that creating a destination with a brand personality in the COVID-19 environment is the key to maintaining the sustainable development of tourism destinations, and emphasized that the brand innovation forced by the epidemic environment may be an opportunity for tourism destinations that maintain the old marketing concept. In general tourism, destination personality (DP), as an important part of destination brand, has attracted the attention of many scholars. Ekinci and Hosany [9] suggested that DP is a viable metaphor for building destination brand image, understanding visitors’ perceptions of destinations, and crafting a unique identity for tourism locations. Through this symbolic attribute, the destination gains a distinguishing label that is conducive to attracting tourists and stimulating the emotions and beliefs of tourists. Some scholars replace destination image (DI) with DP and use self-congruity (SC) theory to explain the decision making and behavioral intention (BI) of tourists e.g., [10,11]. In the field of golf tourism, many scholars have examined BI of golf tourists, aiming to develop targeted marketing strategies by understanding the factors that influence BI e.g., [6,12,13]. However, previous findings tend to focus on the motivations and attitudes of tourists and the functional attributes of destinations e.g., refs. [12,14,15], while a few address the symbolic attributes of destinations.

DP, as a tool for differentiating a destination from its competitors, is an important factor in BI [9]. Boksberger et al. [16] emphasize the uniqueness of the destination as an added value as well as a differentiator so that the character of the destination can guarantee its sustainability and be the direction of innovation going forward. DP consists of characteristics that encourage (or discourage) tourists to continue visiting the destination [5]. Building a unique and attractive DP is an effective marketing tool for developing and keeping tourism destinations sustainable.

Kim et al. [17] pointed out that DP is distinct from DI. DP is the branding of the destination using human characteristics, whereas DI is a person’s view of that destination. Ekinci [18] proposed that as a part of destination brand research, DP is an important component of DI, which is very important to the development of a destination brand. In addition, tourists choose destinations based on the image of the destination, and the overall image of the destination has the most significant influence on choice of destination [19]. Destination marketers have started using a combination of DP and DI to differentiate themselves from competing brands [20]. Research shows that unique and emotionally attractive DP can affect perceived DI and BI [9].

In addition, SC theory is an essential foundation in brand image building [21]. The basic concept of SC theory is that consumers tend to choose brands and services whose personalities and images are consistent with their own personalities and images [22,23]. According to this theory, Sirgy and Su [24] defined SC as the agreement between brand image and individual self-concept, while Usakli and Baloglu [20] defined SC as the match between tourists’ self-concept and DP. Self-concept is the sum of thoughts and feelings that an individual has about himself [25]. That is to say, the image and personality of the destination activate the self-schema related to the self-concept, leading tourists to have preferences and tendencies toward the destination. DP and DI can establish a matching relationship with self-concept to form SC, further affecting BI e.g., refs. [11,22].

Kim at al. [17] pointed out that in order to understand the perception of tourists fully, scholars need to take DI into account in the relationship among DP, SC, and BI. In view of DP, the influencing mechanism between DI and SC might form a more complex decision-making process. This possibility provides important implications for more in-depth study of tourists’ BI. Perhaps DP can indirectly influence BI through both DI and SC. However, previous findings do not substantiate the synergistic mediating role of DI and SC between DP and BI.

Therefore, the purpose of this study was to integrate DP of Hainan Province, combine DI and SC to examine BI among golf tourists, and explore the mediating role of DI and SC. The findings should expand the literature framework in the field of tourism and deepen understanding of golf tourism theory. Within this framework, the primary factors in sustainable development of a destination become clearer, offering guidance to researchers and destination marketers alike.

2. Literature Review

2.1. Sustainable Golf Tourism

Environmental destruction and natural ecosystem damage caused by reckless tourism development are acting as a threat to tourism opportunities for future generations. Sustainable tourism aims to maintain the unique image of the natural environment of the tourist destination and the differentiated personality and attractiveness of the tourism resource itself, rather than the economic effect of tourism development. In this respect, golf tourism belongs to sustainable eco-tourism that emphasizes preserving tourism resources as they are minimizing environmental damage. In order to vitalize sustainable golf tourism, it is necessary to identify the factors affecting the behavioral intentions of tourists and implement marketing strategies to bring economic sustainability. Most strategies for reinforcing the behavioral intentions of golf tourists are to bring about economic sustainability in the region. Economic sustainability, which is one of the sustainable tourism standards proposed by the UNWTO, is possible when golf tourism benefits the local economy and local residents can acquire a circular structure that supports golf tourism. In addition, environmental sustainability is also a major factor that cannot be overlooked, and it can be realized when the negative impact on tourism resources is minimized. Sustainability is regarded as a key factor in terms of tourism competitiveness. In particular, the importance of environmental sustainability as a major variable for improving the competitiveness of tourist destinations and the quality of life of local residents has been highlighted in the long term [26]. Recently, tourism marketing is responding to the market’s demand for environmental conservation by designing tourism products that induce the participation and action of tourists on sustainability and developing persuasive communication. This was made possible by emphasizing the motivations, mechanisms and limitations of tourism enterprises and inducing changes in consumer behavior [27].

2.2. Destination Personality (DP)

Brand personality (BP) is the set of human characteristics associated with a brand [28]. For consumers, a brand with a personality can present a stronger sense of texture, depth, and complex human characteristics [29]. Consumers are more inclined to buy products that seem personalized [27]. Pasquinelli et al. [8] advocated to eliminate the threat posed by COVID-19 by creating a brand personality of destination sustainability to ensure the sustainable development of over-tourism cities. This is a new attempt to look to the future. In recent years, some scholars have combined the concept of brand personality to study the applicability and effectiveness of tourism destinations in the framework of BP e.g., refs. [9,10,20,30]. Ekinci and Hosany [9] combined the concept of BP in the destination environment. They defined DP as the set of human characteristics associated with a destination.

Initially, Aaker [28] constructed the basic theoretical framework of BP and was the first to develop an empirical BP scale. This scale includes five different dimensions: sincerity, excitement, competence, sophistication, and ruggedness. Ekinci and Hosany [9] were the first to examine the applicability and validity of Aaker’s [28] BP framework in the context of tourism destinations [20]. They found that DP includes three significant dimensions: sincerity, excitement, and conviviality. Since then, several scholars have investigated the role of DP in evaluating scale development [17]. Usakli and Baloglu [20] discovered five dimensions: vibrancy, sophistication, competence, contemporary, and sincerity. Kim and Lehto [31] found seven dimensions: excitement, competence, sincerity, sophistication, ruggedness, uniqueness, and family orientation.

2.3. Destination Personality (DP) and Destination Image (DI)

A well-established BP helps distinguish a brand from its competitors [32] and establishes a strong emotional connection between consumers and the brand, thereby generating greater trust and loyalty [33]. Similarly, the unique personality of a destination can effectively use perceived image of the destination, thereby affecting the decision making of tourists [9]. Ha [34] reported that effective marketing and management of DP can help consumers develop a favorable image of that location. DP and DI distinct. DI is the perception of a destination [17]. As a symbolic attribute of a destination [9], DP is an important part of DI [18]. Destinations exhibit excellent quality under the influence of DP, helping form an attractive DI through traits such as sincerity, excitement, and conviviality, thereby attracting tourists [9]. Kovačić et al. [35] found that DP directly affected DI. Therefore, we proposed the following hypothesis:

Hypothesis 1.

DP will influence DI.

2.4. Destination Personality (DP) and Behavioral Intention (BI)

Gomez Aguilar et al. [36] argued that to improve the perceptions that tourists have and contribute to the development of a unique identity, destinations can enhance their brand through careful management of DP. DP is essential to enhance the competitiveness of destinations [17]. According to Ekinci and Hosany [9], DP is an important factor in BI. Scholars have examined the relationship between DP and tourist BI. For example, Usakli and Baloglu [20] and Yang et al. [37] found that DP had a positive impact on revisit intention and recommendation intention. Suryaningsih et al. [5] found that DP had a positive impact on BI and pointed out that DP was an important factor in BI. Therefore, we proposed the following hypothesis:

Hypothesis 2.

DP will influence BI.

2.5. Destination Personality (DP) and Self-Congruity (SC)

As generally defined, self-concept is the totality of an individual’s thoughts and feelings about himself or herself as an object [25]. Usakli and Baloglu [20] defined SC as the match between tourists’ self-concept and DP. A phenomenon derived from the concept of self and an important research topic for psychology and social psychology [38], SC is favorable perception that results from a match between a product idea or image and consumer self-perception. Consumers consider the products or brands they purchase as an expression of themselves, and they tend to prefer products and brands with images similar to their self-concepts [39]. Marketing scholars have demonstrated that greater perceived self-concept in BP is more likely to make perceptions of the brand consistent with consumer self-perception [40]. BP and SC are related but empirically distinct elements of the symbolic benefit of a brand [41], and BP is a precursor to SC [42,43]. Similarly, in the field of tourism, DP and SC are important cognitive constructs in tourism marketing [44]. In the context of tourism, several scholars have tested models of DP and SC. Findings from several studies show that DP strongly affected SC in the context of travel destinations [11,44]. Therefore, we proposed the following hypothesis:

Hypothesis 3.

DP will influence SC.

2.6. Self-Congruity (SC)

Moons et al. [45] examined tourists’ actual self-congruity, ideal self-congruity and social self-congruity’s consistent perception of ecotourism, and the study showed that actual, ideal and social self-ecotourism congruity increase the willingness to pay more for ecotourism. Good ecology is an important synonym for sustainable development, and this result shows that tourists’ pursuit and desire for ecotourism, and are willing to pay actions and money for it. This reflects the current preference for sustainable tourism destinations, and self-congruity is an important factor in promoting the sustainable development of tourism destinations. In the field of tourism, scholars have defined SC as a multidimensional construct that includes actual SC and ideal SC [46], which, as Usakli and Baloglu [20] noted, have received the most theoretical consideration and empirical support. That is, tourists might satisfy the need for SC by visiting destinations consistent with their self-concept, consolidating their thoughts about who they are [39], or they might travel to destinations that satisfy their need for self-esteem [47]. Usakli and Baloglu [20] pointed out that the higher the similarity between DP and self-concept, the greater the chance that tourists will have favorable attitude toward the destination. This attitude might affect willingness to revisit or recommend destinations. Usakli [11] examined the relationship between Las Vegas tourists’ SC and BI and found that SC directly affected BI. Ren et al. [48] demonstrated the causal relationship between self-congruity and behavioral intentions by reporting that self-congruity has a mitigating effect between environmental concerns and intention to visit green destinations.

Larson and Steinman [49] defined BI as a willingness to perform a specific behavior in the future. In most previous studies, behavioral intentions were measured by recommendation and revisit intentions. The recommendation intention was defined as to share the experience through WOM communication, and the revisit intention was defined as to return to the destination [50,51]. These intentions are likely to be influenced by the SC.

Based on previous findings, we proposed the following hypothesis:

Hypothesis 4.

SC will influence BI.

2.7. Destination Image (DI)

DI, an important element of destination brand, is an attitudinal construct consisting of an individual’s mental representation of knowledge (beliefs) about, feelings about, and global impression of an object or destination [52]. Alaeddinoglu and Can [53] noted that DI also refers to perceptions, thoughts, beliefs, and attitudes related to particular characteristics of a destination. Marine-Roig [54] analyzed the usefulness of destination imagery through online travel reviews (OTRs), the results show trends, preferences, assessments, and opinions from the demand side, which can be useful for destination managers in optimizing the distribution of available resources and promoting sustainability. Numerous scholars have used this model to explain the travel behaviour [55]. For example, Song et al. [6] measured Hainan golf tourists’ perception of DI through two constructs: cognitive image and affective image. Micera and Crispino [56] argued that DI plays an important role in tourists’ decision making and subsequent travel behavior. Previous findings showed that DI predicts BI e.g., refs. [57,58,59,60] and that destinations with a positive image lead to higher behavioral intentions among tourists [61]. According to Humphreys [62], location amenities and golf-related features determine the popularity of golf destinations. Thus, we proposed the following hypothesis:

Hypothesis 5.

DI will influence BI.

2.8. The Mediating Role of Destination Image (DI) and Self-Congruity (SC)

DP is an important component of DI [18], and DI is an important factor in BI [19]. Previous findings verify the mediating effect of DI on DP and BI. For example, Ekinci and Hosany [9] found that DI played a positive mediating role between DP and recommendation intention. Apostolopoulou and Papadimitriou [63] also found that DI played a positive mediating role between DP and BI.

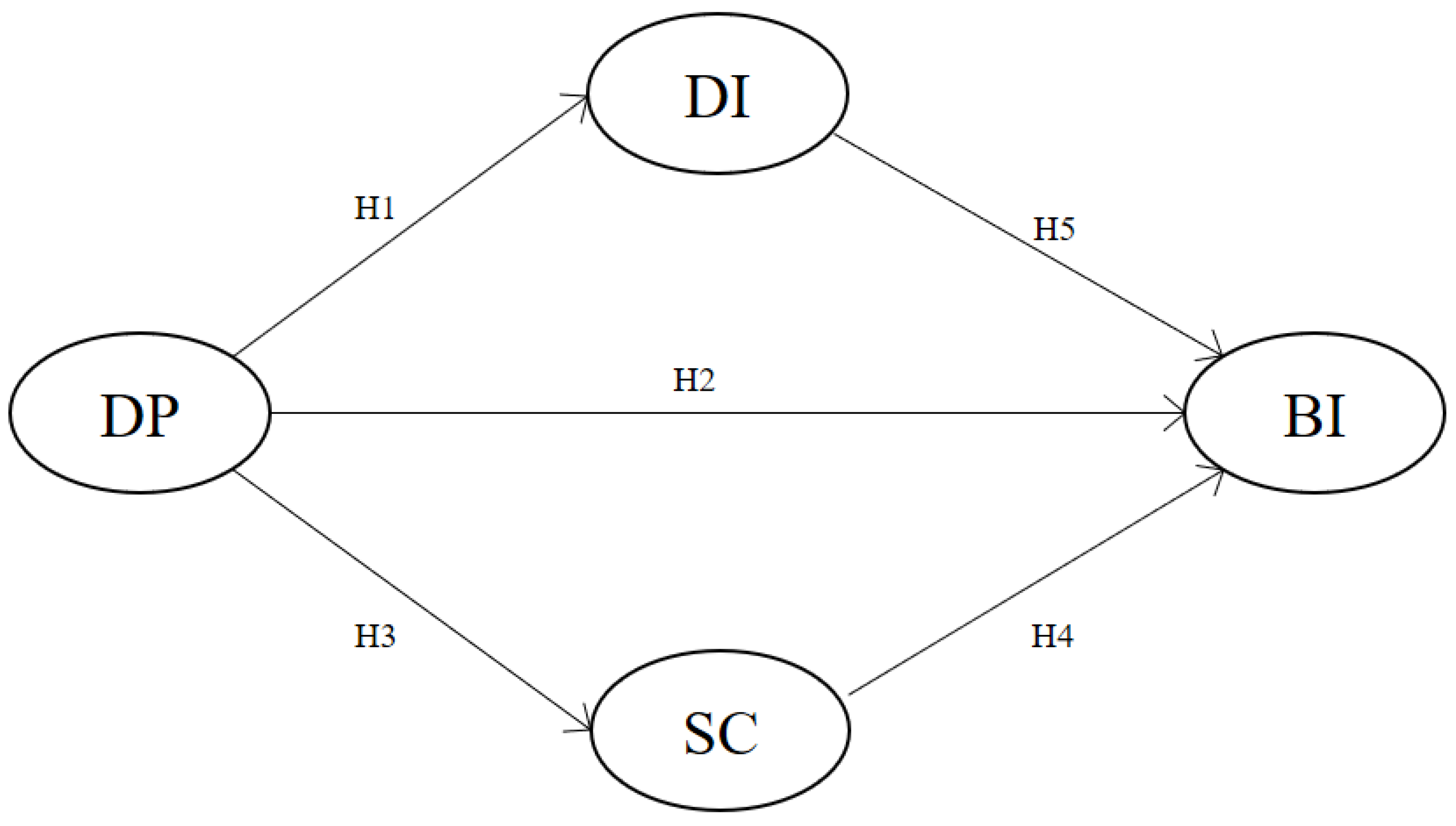

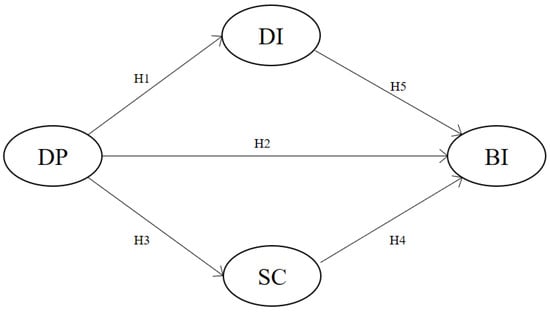

In addition, some scholars have examined the mediating role of SC between DP and BI based on SC theory. For example, Usakli and Baloglu [20] found that SC played a partial mediating role in the relationship between DP and tourist BI. Yang et al. [21] a lso reported that SC played a potential mediating role between DP and revisit intention and recommendation intention. Therefore, we proposed the following hypotheses (see Figure 1):

Figure 1.

Research Model. H6: Mediation effect DP → DI → BI. H7: Mediation effect DP → SC→ BI. Note. DP = Destination Personality, DI = Destination Image, SC = Self-congruity, BI = Behavioral Intention.

Hypothesis 6.

DIwill have an intermediary effect onDP andBI.

Hypothesis 7.

SCwill have an intermediary effect onDP andBI.

3. Methods

3.1. Subject

Hainan Province is one of the most famous tourism provinces in China, in part due to strong policy support from the state. At present, the golf tourism industry in Hainan Province has reached full maturity. Due to its special geographical location, beautiful environment, and unique tropical climate, in 2020, Hainan Province received a total of 64.55 million domestic and foreign tourists, achieving one of the best tourism recoveries from COVID-19 in the country [64]. Hainan, a beautiful resort area, is a golf tourist attraction with the best environment to enjoy golf in the best weather all year round as well as winter. Hainan Province (Hainan Island) is located at the southernmost tip of mainland China and is the largest province in China by land area (land area plus ocean area). Hainan Province has a total land area of 35,000 square kilometers and a sea area of about 2 million square kilometers, of which Hainan Island covers an area of 33,900 square kilometers. Hainan Island is located on the northern edge of the tropics and has a tropical monsoon climate. It has always been known as a “natural greenhouse”, with an annual average temperature of 22–27 °C. Hainan Island is the native place of tropical rain forests and tropical monsoon rain forests, with a wide variety of animals and plants. Among them, there are more than 4000 vascular plants, of which more than 600 are endemic to Hainan, and there are more than 1000 wild animals.

The research subject of the current study was golf tourists who had traveled to Hainan in the previous twelve months of COVID-19 pandemic (1 July 2020–1 July 2021). The questionnaire survey period was 1 July 2021 to 30 August 2021. We created an online questionnaire (https://www.wjx.cn, accessed on 30 June 2021) and received assistance with data collection from the Hainan China Youth Travel Service. The company selected 10 outstanding tour guides as investigators for this survey. After receiving intensive training, each investigator randomly selected, from members of tour groups they had led, 60 golf tourists who had traveled to Hainan during the designated period (investigators contacted the golf tourists through WeChat). The golf tourists were over 18 years old and had stayed at least one night in Hainan. The investigators then asked golf tourists to take the online survey after explaining its purpose and precautions. Investigators sent participants a link to the online survey via WeChat after obtaining their consent. Finally, the online survey yielded 519 valid data. All participants were Chinese tourists from cities outside Hainan Province.

3.2. Measurement

The measurement items used in this study were modified items from existing studies. To ensure the consistency of the measurement tools, we used reverse translation to proofread the content of the questionnaire in English and Chinese. All items featured a 5-point Likert scale ranging from 1 = strongly disagree to 5 = strongly agree.

3.2.1. Destination Personality

We adapted DP items from Ekinci and Hosany [9] and Ekinci et al. [65]. Ekinci and Hosany [9] were the first to conceptualize and measure tourism DP, which they interpreted as having three dimensions: conviviality, sincerity, and excitement. On this basis, Ekinci et al. [65] measured the DP of an entire region. We measured DP using the same three dimensions; conviviality included three items, sincerity included six items, and excitement included four items (see Table 1).

Table 1.

CFA results for measurement model.

3.2.2. Destination Image

We used several measurement items to assess the sub-dimensions of DI. We developed the questionnaires based on a thorough literature review and measured DI using two subscales: cognitive image (5 items) and affective image (3 items) [6] (see Table 1).

3.2.3. Self-Congruity

Usakli and Baloglu [20] viewed SC as having two measurement dimensions (i.e., actual congruity and ideal congruity), and their scale has high reliability. Mason et al. [66] measured the SC of exercise tourists based on this concept. Their results show that this measurement method and high validity is also suitable for golf tourists. We measured SC using two subscales [20,66]: actual congruity (4 items) and ideal congruity (4 items) (see Table 1).

3.2.4. Behavioral Intention

We adapted BI from Apostolopoulou and Papadimitriou [63], Kim et al. [17], Sharma and Nayak [67], and Song et al. [6]. We measured BI using two dimensions: revisit intention (4 items) and recommendation intention (3 items) (see Table 1).

3.3. Data Analysis

According to the recommendations of Anderson and Gerbing [68], we divided data analysis into two stages. In the first stage, we used confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) to test the reliability and validity of the scale. In the second stage, we used structural equation modeling (SEM) to test the proposed hypotheses.

4. Results

4.1. Characteristics of Participants

As shown in Table 2, respondents included 325 males (62.6%) and 194 females (37.4%). Most were 30–49 years old (63%); the rest were 18–29 years old (18.1%) and over 50 years old (18.9%). A large majority (61.2%) had a college degree or higher. The respondents came from various occupations, among which were engineer (14.6%), junior manager (14.6%), civil servant (10.4%), senior manager (10.4%), and staffer (10.2%). Most of the respondents (60.9%) had a high monthly income of more than 10,000 yuan. Most of the respondents play golf in Hainan Province either 1–2 times a year (41.8%) or 3–4 times a year (39.3%).

Table 2.

Demographic characteristics of the respondents.

4.2. Measurement Model

The measurement model used maximum likelihood (ML) estimation to test the correlations among the 36 items across 4 latent variables: 13 items for DP, 8 items for DI, 8 items for SC, 7 items for BI (see Table 1).

CFA permits assessment of model fit through the following indices: chi-square/df < 5.0 [69], root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA) < 0.08 [70], goodness of fit index (GFI) > 0.90, Tucker-Lewis index (TLI) > 0.90 [71], and comparative fit index (CFI) > 0.90 [72]. In this study, χ2 = 915.456, df = 579, p < 0.05, χ2/df = 1.581, RMSEA = 0.033, TLI = 0.965, GFI = 0.912, CFI = 0.967, indicating acceptable model fit (see Table 3).

Table 3.

Model fit for the measurement model.

We used Cronbach’s alpha (α > 0.70) and composite reliability (CR > 0.70) to test the reliability of the factors. We tested construct validity using convergent validity and discriminant validity. The factor loadings (λ) of all measurement variables were higher than the critical standard of 0.50 and significant and average variance extracted (AVE) was higher than 0.50, indicating that the scale had convergent validity [73]. Discriminant validity derives from the fact that the square root of AVE is greater than the correlation between structures [74]. Table 1 shows that all Cronbach’s alpha values exceeded the minimum reliability standard of 0.7 recommended by Nunnally and Bernstein [75]. The CR value ranged from 0.757 to 0.903, which exceeded the threshold of 0.70 [76]. The factor loading (λ) of each measurement variables was higher than the critical standard of 0.50, and the range was 0.651~0.903. AVE values ranged from 0.538 to 0.647, exceeding the threshold of 0.50 [77]. The model had sufficient reliability and convergence validity.

Table 4 shows that the correlation coefficient (0.469~0.603) of each variable is less than the square root of the AVE of each variable (0.780~0.799), supporting discriminative validity. In general, the measurement model had sufficient discriminant validity.

Table 4.

Discriminant validity of the model.

4.3. Structural Model

After validating the measurement model, we used SEM to verify the nomological relationships [78] among the four latent variables: (a) direct relationships between BI and both DI and SC, (b) direct relationships between DP and both DI and SC, (c) direct relationship between DI and SC, (d) and mediating effect of DI and SC in the relationship between DP and BI.

Testing the structural model involved significance measures for estimated coefficients, providing evidence to support or reject the proposed relationships among the construct variables [79]. The indices used to evaluate the measurement model were indicators of structural model fit: χ2/df, RMSEA, GFI, TLI, and CFI. The model fit indices revealed that the measurement model and the structural model were acceptable: Degree of fit was very good: χ2/df = 1.595, RMSEA = 0.034, GFI = 0.912, TLI = 0.964, and CFI = 0.967. The four latent variables in the measurement model had strong reliability and validity. In addition, the structural model had excellent fit indices (see Table 5).

Table 5.

Model fit for the structural model.

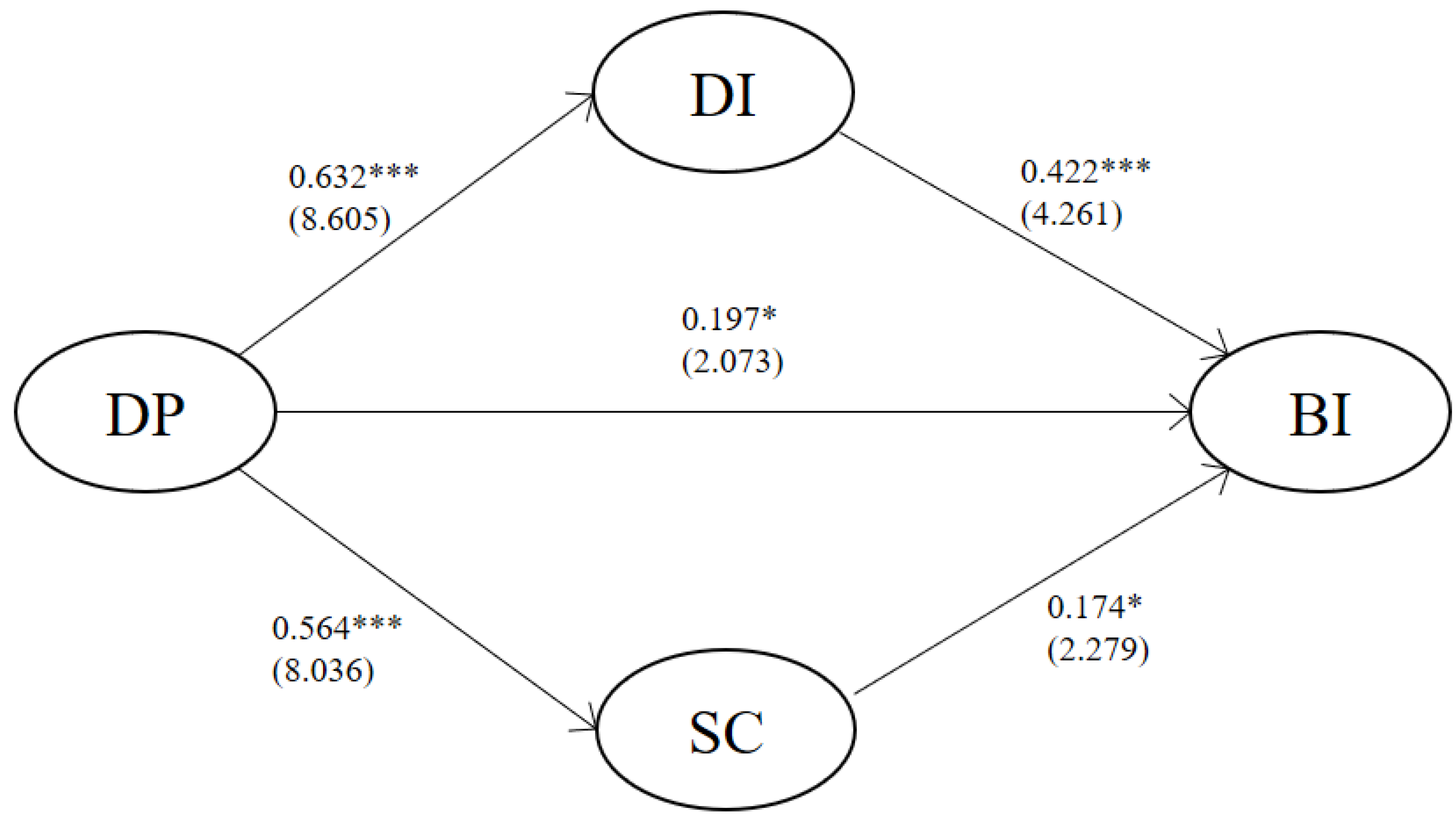

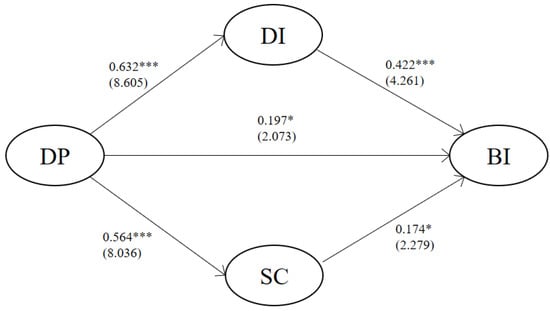

We analyzed the structural model to test the seven hypotheses, all of which were supported. The standardized effects of DP positively influenced DI (β = 0.632, t = 8.605), BI (β = 0.197, t = 2.073), and SC (β = 0.564, t = 8.036). The findings show that when DP moved by one deviation, DI moved by 0.632 standard deviations, BI moved by 0.197 standard deviations, and SC moved by a standard deviation of 0.564, supporting H1, H2, and H3. SC positively influenced BI (β = 0.174, t = 2.279), supporting H4. DI positively related to BI (β = 0.422, t = 4.261), supporting H5 (see Table 6).

Table 6.

SEM results for structural model.

Although scholars have separately explored the mediating effect of DI and SC on DP and BI, research on the synergistic mediating effect of DI and SC on DP and BI remains limited. To fill this gap, we used bootstrapping to test the mediating effects of SC and DI. We calculated the bias-corrected 95% confidence interval based on 5000 samples. Bootstrapping provides a confidence interval for indirect effects, indicating mediating effects when the interval between the lower and upper bounds of the 95% confidence interval does not contain zero [80].

The mediating effects of SC and DI were significant because the bias-corrected (95%) interval did not contain 0 in any of the paths. These results indicate that SC and DI mediated the relationship between DP and RI, supporting H6 and H7 (see Table 7 and Figure 2).

Table 7.

Bootstrapping test for mediating effects.

Figure 2.

Structural Model. Note. * p < 0.05; *** p < 0.001.

5. Discussion

The purpose of this study was to explore the causes of BI among golf tourists based on previous findings and investigation of the interrelationships among DP, DI, SC, and BI. The findings enhance the theoretical understanding of golf tourism. Scholars in the general tourism field have conducted extensive research on the interrelationships among DP, DI, SC, and BI e.g., refs. [9,17,20]. However, none have applied SC theory to golf tourism to examine the co-mediating role of DI and SC in the relationship between DP and BI.

The findings show that DP had the most significant impact on DI, supporting the claim that many tourist destinations have specific personality traits [81,82] and that these personality traits reinforce perceived image and influence choice behavior among tourists [9]. Obviously, Hainan’s human-like personality characteristics generate intuitive emotional cognition in golf tourists. This metaphorical image strengthens the emotional connection between golf tourists and tourist destinations, making emotional cognition of the destination more profound and concrete, thus further promoting the formation of DI. Therefore, our finding supports the view of Ekinci [18] that DP is an important element in DI.

DP and BI positively correlated. The more prominent the personality of Hainan, the stronger the revisit and recommendation intention of golf tourists. This finding shows that a series of personality traits distinguish Hainan from other destinations, attracting attention and influencing preference. Destination personalities such as conviviality, sincerity, and excitement influence the positive emotions of tourists, reinforcing BI. The establishment of this emotional connection motivates BI. As Suryaningsih et al. [5] showed, DP can provide various characteristics that motivate visitors to revisit. As our findings confirm, DP is an important factor in BI [5,9,20].

Consistent with previous findings [21,44], DP had a positive and significant effect on SC. This finding supports the argument that tourists associate their personalities with tourist destinations when pursuing a satisfactory tourism experience and tend to choose an area that matches their personalities [83]. The match between perceived DP and self-concept further strengthen favorable positive perceptions of SC (i.e, actual SC and ideal SC). In other words, after golf tourists visited Hainan, their perceived DP solidified their idea of who they are (i.e., actual SC) [39] and fulfilled their self-esteem needs (i.e., ideal SC) [47]. Previous findings suggest that tourist destinations should have a story that matches the personality of tourists.

The findings also indicate a positive relationship between SC and BI. According to SC theory, consumers tend to choose brands and services whose personality and image are consistent with their own [22,23]. Previous findings [20,21] show that the higher the perceived SC, the more tourists favor a destination, resulting in willingness to revisit and recommend. These previous findings align with the significant relationship between SC and BI we found. The charm and characteristics displayed by Hainan were consistent with the ideal standard of golf tourists themselves. In other words, Hainan was exactly what the tourists were looking for to suit their tastes. The favorable attitude formed by good emotional cognition stimulated BI.

DI has a positive effect on BI [84]. Ryu et al. [85] pointed out that brand image is a determinant of subjective perception and consequent behavior. Previous findings show that DI predicts BI e.g., refs. [57,58] and that destinations with a positive image lead to higher behavioral intentions among tourists [61]. The image of Hainan (e.g., tropical island style, beautiful seascape, cultural diversity, economic prosperity, civilized hospitality) predicted high revisit intention and high recommendation intention of the golf tourists.

Echtner and Ritchie [86] stated that the image of a tourist destination is a significant factor in the behavioral decision making of actual or potential tourists. Confirming the argument of Assaker et al. [87], Hainan shows that building DI is necessary to promote revisit intention.

Based on the results, we found that DP played a crucial role in the formation of BI. Three pathways from DP to BI emerged: direct, mediated by DI, mediated by SC. These results suggest that DP plays a decisive role in shaping how golf tourists select destinations, as found by previous scholars [5,17,20].

In addition, we found that DI and SC jointly played a mediating role between DP and BI. This fills a gap in previous studies, confirming the synergistic mediating role of DI and SC between DP and BI and further enriching the theoretical framework of tourism research.

6. Conclusions and Implications

6.1. Conclusions

Based on the SC theory, we constructed a reasonable structural model including DP as the dominant factor and DI, SC, and BI. The results supported all hypotheses. The relationships between these variables are clear, and the mediating role of DI and SC between DP and BI was significant. This resulting model explains the entire decision-making process of golf tourists and identified the main factors influencing the sustainable development of golf tourism destination in the COVID-19 environment.

6.2. Implications

6.2.1. Theoretical Implications

This study mainly examined the influencing factors of behavioral intentions of golf tourists, key stakeholders of golf tourism destinations, in the context of COVID-19. Tourists’ behavioral intentions include revisit intentions and recommendation intentions. Higher revisit intentions and recommendation intentions indicate the guarantee of sustainable development of tourist destinations. According to the results, the main factor affecting tourist BI was DP, followed by DI and SC. The results of the study show that DP, DI, SC and BI are the main influencing factors for the sustainable development of a small tourism market such as Hainan golf under the COVID-19 environment.

In addition, the findings show that DI influenced DP, SC, and BI, expanding the tourism literature and responding to the call made by Kim et al. [17]. The results for DP show the applicability of the personality dimensions of conviviality, sincerity, and excitement to golf tourism. The complex mediating role of SC and DI between DP and BI helps explain why tourists choose a destination. Accordingly, managers and marketers can better understand the specific reasons behind the decision making of tourists.

Third, the findings contribute to golf tourism theory and broaden the field of sports tourism. Even in the context of COVID-19, DP, DI, and SC drove the BI of golf tourists. The positive relationships among these variables explains the decision-making process of golf tourists from a new perspective, opening a new research pathway for sports tourism.

6.2.2. Practical Implications

The research results provide enlightenment for the formulation of marketing strategies and sustainable development strategies for Hainan golf small tourism under the new crown pneumonia environment.

First, in today’s competitive environment, creating and managing a favorable DP has become the key to effective positioning and differentiation. Destination marketers should focus on developing effective communication methods to launch a unique and attractive personality for their place [9]. Especially in the new competitive environment after the baptism of the COVID-19 epidemic, it is even more necessary to highlight the personality of the destination and establish a distinctive tourism destination brand. This helps to improve the destination image, enhance the emotional connection between tourists and the destination, and further attract tourists, thereby ensuring the vitality and sustainability of the tourism destination market. Hainan’s destination marketers should position and differentiate this golf tourism destination according to conviviality, sincerity, and excitement. These positive personality perceptions in the epidemic environment must benefit from the good epidemic prevention effect of the COVID-19 epidemic. According to the statistics of Hainan City in May 2022, facts have also proved that the total number of infected people in Hainan Province has not exceeded 300 since the beginning of the COVID-19 outbreak [88]. Establishing good epidemic prevention and public health safety measures will become the premise of highlighting the brand personality of tourist destinations and the sustainable development of tourist destinations. Although Pasquinelli et al. [8] emphasized that with the adjustment of foreign passenger flow and the rebound of the tourism economy, the new characteristics of sustainable city brands may disappear. However, due to the profound impact of the catastrophe of COVID-19, it is believed that people pursue green Health and safety awareness of travel will become a normalization.

Second, Hainan marketers can cultivate strong DP traits through advertising and destination management strategies, thereby enhancing the positive impact of DI on BI. For example: to create a tourism culture system with the theme of local residents, showing local ethnic customs, traditional culture and hospitality. Zouganeli et al. [89] pointed out that the concept of sustainability is based on the premise that the inhabitants of a destination should participate in the way in which that destination is managed and promoted. Under the new situation, it is necessary to abandon the bad habit of ignoring the important stakeholders in the sustainable development of tourism destinations—local residents. Catering to tourists’ demands by establishing a good destination image is a necessary means to promote the sustainable development of tourism destinations.

Third, Hainan marketers should focus on establishing the connection between DP and SC and carry out marketing campaigns that emphasize this match. For example: to create a characteristic tourism route with the theme of ecology, green and environmental protection. Moons et al. [45] also proved the preference of mass tourists for ecotourism through research. Especially when the COVID-19 epidemic is serious, we should pay more attention to natural ecological protection while developing the economy, and abandon the previous bad habits of egoistic marketing that put economic interests first. Doing so will help cater to the current psychological trends of tourists and create their ideal travel environment and destination. Most importantly, a natural and ecological destination helps to present a harmonious and stable social structure, so that the overall value and meaning of the tourists themselves can be reflected. A good ecology and harmonious society will bring about an economically prosperous and sustainable tourism destination.

7. Limitation Future Research

Although this study is of great significance, there are still certain research limitations. First, this study only examined Chinese tourists. In future research, it is necessary to conduct research on tourists from the countries that visit Hainan the most. In a follow-up study, if we study what is the personality of Hainan that foreign tourists think, and whether there is a match between Hainan and their own image, it will be possible to establish a more efficient and detailed marketing strategy. This will ensure the sustainability of the local economy through the revitalization of sustainable tourism in the Hainan region in time of a pandemic. Second, this study was targeted at Chinese tourists visiting Hainan, and it is necessary to expand the subject to other famous tourist destinations in future research. This will be a meaningful study that will confirm not only the individuality of each region, but also the individuality of China that foreigners and Chinese think of.

Author Contributions

S.Z. contributed conceptualization, literature review, methodology, and analysis, and original draft preparation. K.K. contributed the introduction, result interpretation, methodology revision, and manuscript editing. B.H.Y. contributed the discussion and manuscript editing and oversaw the research design and execution and contributed to the manuscript composition. B.H. and W.C. contributed the literature review and interview data collection. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted according to the guide-lines of the Jilin Normal University, and the Ethical review and approval were waived for this study as it was evaluated to be a Level 1 study (covers research with participants that is ‘non-problematic’).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Huth, C.; Billion, F. Insights on the impact of COVID-19 and the lockdown on amateur golfers. Qual. Sport 2021, 7, 7–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huth, C.; Kurscheidt, M. Membership versus green fee pricing for golf courses: The impact of market and golf club determinants. Eur. Sport Manag. Q. 2019, 19, 331–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Billion, F. Corona Undder Deutsche Golfmarkt, Präsentation Für Den Regionalkreises Südwest Des; GMVD: Cayman Islands, UK, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Papadimitriou, D.; Apostolopoulou, A.; Kaplanidou, K. Destination personality, affective image, and behavioral intentions in domestic urban tourism. J. Travel Res. 2015, 54, 302–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suryaningsih, I.B.; Nugraha, K.S.W.; Anggita, R.M. Is Cultural Background Moderating the Destination Personality and Self Image Congruity Relationship of Behavioral Intention? J. Appl. Manag. 2020, 18, 353–362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, H.M.; Kim, K.S.; Yim, B.H. The mediating effect of place attachment on the relationship between golf tourism destination image and revisit intention. Asia Pac. J. Tour. Res. 2017, 22, 1182–1193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amateur Golf Premier League Finals Kick Off with 51 Teams Participating. Available online: https://sports.sina.com.cn/golf/chinareport/2020-11-22/doc-iiznezxs3115702.shtml (accessed on 22 November 2020).

- Pasquinelli, C.; Trunfio, M.; Bellini, N.; Rossi, S. Sustainability in overtouristified cities? A social media insight into Italian branding responses to COVID-19 crisis. Sustainability 2021, 13, 1848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ekinci, Y.; Hosany, S. Destination personality: An application of brand personality to tourism destinations. J. Travel Res. 2006, 45, 127–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Klabi, F. The predictive power of destination-personality-congruity on tourist preference: A global approach to destination image branding. Leis./Loisir 2012, 36, 309–331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Usakli, A. The Relationship between Destination Personality, Self-Congruity, and Behavioral Intentions. Master’s Thesis, University of Nevada, Las Vegas, NV, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- López-Bonilla, J.M.; Reyes-Rodríguez, M.D.C.; López-Bonilla, L.M. The environmental attitudes and behaviours of European golf tourists. Sustainability 2018, 10, 2214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Sun, K.; Fang, C.C. Research on the relationships among participation motivation, participation attitude and revisit intention in Thai golf tourism: A study based on mediation model. Humanit. Arts Soc. Sci. Stud. 2021, 21, 491–504. [Google Scholar]

- Song, H.M.; Chen, J.M.; Zeng, T.T. Modeling Golfers’ revisit intention: An application of the theory of reasoned action. J. Hosp. Tour. Res. 2021, 20, 114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, H.; Chen, J.M.; Chen, Y. Mediating and moderating effects in golf tourism: Evidence from Hainan Island. Tour. Econ. 2021, 27, 510–526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boksberger, P.; Dolnicar, S.; Laesser, C.; Randle, M. Self-congruity theory: To what extent does it hold in tourism? J. Travel Res. 2011, 50, 454–464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Kim, W.; Malek, K.; Kim, N.; Kim, S. Destination personality, destination image, and intent to recommend: The role of gender, age, cultural background, and prior experiences. Sustainability 2018, 10, 87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Ekinci, Y. From destination image to destination branding: An emerging area of research. E-Rev. Tour. Res. 2003, 1, 21–24. [Google Scholar]

- Maghsoodi Tilaki, M.J.; Hedayati Marzbali, M.; Abdullah, A.; Bahauddin, A. Examining the influence of international tourists’ destination image and satisfaction on their behavioral intention in Penang, Malaysia. J. Qual. Assur. Hosp. Tour. 2016, 17, 425–452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Usakli, A.; Baloglu, S. Brand personality of tourist destinations: An application of self-congruity theory. Tour. Manag. 2011, 32, 114–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, S.; Isa, S.M.; Wu, H.; Ramayah, T.; Jermsittiparsert, K. Examining the role of destination image, self-congruity and trip purpose in predicting post-travel intention: The case of Chinese tourists in New Zealand. Rev. Argent. De Clin. Psicol. 2020, 29, 1504–1517. [Google Scholar]

- Aaker, J.L. Brand Personality: Conceptualization, Measurement and Underlying Psychological Mechanisms. Ph.D. Thesis, Rajamangala University, Khlong Hok, Tailand, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Belanche, D.; Casaló, L.V.; Flavián, M.; Ibáñez-Sánchez, S. Understanding influencer marketing: The role of congruence between influencers, products and consumers. J. Bus. Res. 2021, 132, 186–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sirgy, M.J.; Su, C. Destination image, self-congruity, and travel behavior: Toward an integrative model. J. Travel Res. 2000, 38, 340–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosenberg, M. Society and the Adolescent Self-Image: Conceiving the Self; Princeton University Press: Princeton, NJ, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Huybers, T.; Bennet, J. Environmental management and the competitiveness of nature-based tourism destinations. Environ. Resour. Econ. 2003, 24, 213–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Font, X.; McCabe, S. Sustainability and marketing in tourism: Its contexts, paradoxes, approaches, challenges and potential. J. Sustain. Tour. 2017, 25, 869–883. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Aaker, J.L. Dimensions of brand personality. J. Mark. Res. 1997, 34, 347–356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, K.L.; Lee, J.S. Toward the perspective of cognitive destination image and destination personality: The case of Beijing. J. Travel Tour. Mark. 2013, 30, 538–556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hultman, M.; Strandberg, C.; Oghazi, P.; Mostaghel, R. The role of destination personality fit in destination branding: Antecedents and outcomes. Psychol. Mark. 2017, 34, 1073–1083. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, S.; Lehto, X.Y. Projected and perceived destination brand personalities: The case of South Korea. J. Travel Res. 2013, 52, 117–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aaker, D.A. Building Strong Brands; Simon and Schuster: New York, NY, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Fournier, S. Consumers and their brands: Developing relationship theory in consumer research. J. Consum. Res. 1998, 24, 343–373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ha, H.Y. The evolution of brand personality: An application of online travel agencies. J. Serv. Mark. 2016, 30, 529–540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kovačić, S.; Jovanović, T.; Vujičić, M.D.; Morrison, A.M.; Kennell, J. What shapes activity preferences? The role of tourist personality, destination personality and destination image: Evidence from Serbia. Sustainability 2022, 14, 1803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gomez Aguilar, A.; Yaguee Guillen, M.J.; Villasenor Roman, N. Destination brand personality: An application to Spanish tourism. Int. J. Tour. Res. 2016, 18, 210–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, S.; Isa, S.M.; Ramayah, T.; Blanes, R.; Kiumarsi, S. The effects of destination brand personality on Chinese tourists’ revisit intention to Glasgow: An examination across gender. J. Int. Consum. Mark. 2020, 32, 435–452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sop, S.A.; Kozak, N. Effects of brand personality, self-congruity and functional congruity on hotel brand loyalty. J. Hosp. Mark. Manag. 2019, 28, 926–956. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sirgy, M.J. Self-congruity theory in consumer behavior: A little history. J. Glob. Sch. Mark. Sci. 2018, 28, 197–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klipfel, J.A.; Barclay, A.C.; Bockorny, K.M. Self-Congruity: A Determinant of Brand Personality. J. Mark. Dev. Compet. 2014, 8, 130–143. [Google Scholar]

- Helgeson, J.G.; Supphellen, M. A conceptual and measurement comparison of self-congruity and brand personality: The impact of socially desirable responding. Int. J. Mark. Res. 2004, 46, 205–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matzler, K.; Strobl, A.; Stokburger-Sauer, N.; Bobovnicky, A.; Bauer, F. Brand personality and culture: The role of cultural differences on the impact of brand personality perceptions on tourists’ visit intentions. Tour. Manag. 2016, 52, 507–520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, L.; Zhang, M.; Gursoy, D.; Lu, L. Development and validation of a destination personality scale for mainland Chinese travelers. Tour. Manag. 2017, 59, 338–348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, V. Examining the role of destination personality and self-congruity in predicting tourist behavior. Tour. Manag. Perspect. 2016, 20, 217–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moons, I.; De Pelsmacker, P.; Barbarossa, C. Do personality-and self-congruity matter for the willingness to pay more for ecotourism? An empirical study in Flanders, Belgium. J. Clean. Prod. 2020, 272, 122866. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chua, B.L.; Kim, H.C.; Lee, S.; Han, H. The role of brand personality, self-congruity, and sensory experience in elucidating sky lounge users’ behavior. J. Travel Tour. Mark. 2019, 36, 29–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beerli, A.; Meneses, G.D.; Gil, S.M. Self-congruity and destination choice. Ann. Tour. Res. 2007, 34, 571–587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, J.Z.; Long, T.L.; Liang, R.Q. The Impact of Tourists’ Green Social Identity on Their Visiting Intentions to Green Destinations: The Moderating Role of Self-Congruity. In Proceedings of the 8th Annual China Marketing International Conference (CMIC), Beijing, China, 27 June 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Larson, B.V.; Steinman, R.B. Driving NFL fan satisfaction and return intentions with concession service quality. Serv. Mark. Q. 2009, 30, 418–428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeong, Y.; Yu, A.; Kim, S.K. The antecedents of tourists’ behavioral intentions at sporting events: The case of South Korea. Sustainability 2019, 12, 333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Jeong, Y.; Kim, S.K.; Yu, J.G. Determinants of behavioral intentions in the context of sport tourism with the aim of sustaining sporting destinations. Sustainability 2019, 11, 3073. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Baloglu, S.; McCleary, K.W. A model of destination image formation. Ann. Tour. Res. 1999, 26, 868–897. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alaeddinoglu, F.; Can, A.S. Destination image from the perspective of travel intermediaries. Anatolia 2010, 21, 339–350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marine-Roig, E. Destination image analytics through traveller-generated content. Sustainability 2019, 11, 3392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Chen, C.C.; Lai, Y.H.R.; Petrick, J.F.; Lin, Y.H. Tourism between divided nations: An examination of stereotyping on destination image. Tour. Manag. 2016, 55, 25–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Micera, R.; Crispino, R. Destination web reputation as smart tool for image building: The case analysis of Naples city-destination. Int. J. Tour. Cities 2017, 3, 2056–5607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mercadé Melé, P.; Molina Gómez, J.; Sousa, M.J. Influence of sustainability practices and green image on the re-visit intention of small and medium-size towns. Sustainability 2020, 12, 930. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Nazir, M.U.; Yasin, I.; Tat, H.H. Destination image’s mediating role between perceived risks, perceived constraints, and behavioral intention. Heliyon 2021, 7, e07613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nam, S.; Oh, Y.; Hong, S.; Lee, S.; Kim, W.H. The Moderating Roles of Destination Regeneration and Place Attachment in How Destination Image Affects Revisit Intention: A Case Study of Incheon Metropolitan City. Sustainability 2022, 14, 3839. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kanwel, S.; Lingqiang, Z.; Asif, M.; Hwang, J.; Hussain, A.; Jameel, A. The influence of destination image on tourist loyalty and intention to visit: Testing a multiple mediation approach. Sustainability 2019, 11, 6401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Tavitiyaman, P.; Qu, H.; Tsang, W.S.L.; Lam, C.W.R. The influence of smart tourism applications on perceived destination image and behavioral intention: The moderating role of information search behavior. J. Hosp. Tour. Manag. 2021, 46, 476–487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Humphreys, C. Understanding how sporting characteristics and behaviours influence destination selection: A grounded theory study of golf tourism. J. Sport Tour. 2014, 19, 29–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Apostolopoulou, A.; Papadimitriou, D. The role of destination personality in predicting tourist behaviour: Implications for branding mid-sized urban destinations. Curr. Issues Tour. 2015, 18, 1132–1151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- In 2020, Hainan Will Receive 64.5509 Million Tourists and Achieve a Total Tourism Income of 87.286 Billion Yuan. Available online: https://www.askci.com/news/chanye/20210304/1003531373751.shtml (accessed on 4 March 2021).

- Ekinci, Y.; Sirakaya-Turk, E.; Baloglu, S. Host image and destination personality. Tour. Anal. 2007, 12, 433–446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mason, M.C.; Moretti, A.; Raggiotto, F.; Paggiaro, A. Conceptualizing triathlon sport event travelers’ behavior. Tourismos 2019, 14, 164–188. [Google Scholar]

- Sharma, P.; Nayak, J.K. RETRACTED: Testing the role of tourists’ emotional experiences in predicting destination image, satisfaction, and behavioral intentions: A case of wellness tourism. Tour. Manag. Perspect. 2018, 28, 41–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, J.C.; Gerbing, D.W. Structural equation modeling in practice: A review and recommended two-step approach. Psychol. Bull. 1988, 103, 411–423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kline, R.B. Principles and Practice of Structural Equation Modeling (3. Baskı); Guilford: New York, NY, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Coughlan, D. Shadows. Ghost Writing in Contemporary American Fiction; Palgrave Macmillan: London, UK, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Hooper, D.; Coughlan, J.; Mullen, M. Structural equation modeling: Guidelines for determining model fit. Electron. J. Bus. Res. Methods 2008, 6, 53–60. [Google Scholar]

- Hair, J.F.; Ringle, C.M.; Sarstedt, M. PLS-SEM: Indeed a silver bullet. J. Mark. Theory Pract. 2011, 19, 139–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, J.F.; Black, W.C.; Babin, B.J.; Anderson, R.E. Multivariate Data Analysis: Pearson New International Edition; Pearson Education Limited: Essex, UK, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Fornell, C.; Larcker, D.F. Evaluating structural equation models with unobservable variables and measurement error. J. Mark. Res. 1981, 18, 39–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nunnally, J.C.; Bernstein, I.H. Psychometric Theory; Mcgraw-Hill: New York, NY, USA, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Hair, J.F.; Black, W.C.; Babin, B.J.; Anderson, R.E.; Tatham, R. Multivariate Data Analysis; Pearson Prentice Hall: Upper saddle River, NJ, USA, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Lin, L.; Huang, Z.; Othman, B.; Luo, Y. Let’s make it better: An updated model interpreting international student satisfaction in China based on PLS-SEM approach. PLoS ONE 2020, 15, e0233546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alexandris, K.; Funk, D.C.; Pritchard, M. The impact of constraints on motivation, activity attachment, and skier intentions to continue. J. Leis. Res. 2011, 43, 56–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramseook-Munhurrun, P.; Seebaluck, V.N.; Naidoo, P. Examining the structural relationships of destination image, perceived value, tourist satisfaction and loyalty: Case of Mauritius. Procedia-Soc. Behav. Sci. 2015, 175, 252–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Byrne, B.M. Structural Equation Modeling with AMOS: Basic Concepts, Applications, and Programming; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Morgan, A.; Prictchard, A. Conceptualizing destination branding. In Destination Branding: Creating the Unique Destination Proposition; Morgan, N., Pritchard, A., Pride, R., Eds.; Butterworth-Heinemann: Oxford, UK, 2002; pp. 11–41. [Google Scholar]

- Santos, C.A. Framing portugal representational dynamics. Ann. Tour. Res. 2004, 3, 122–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murphy, L.; Moscardo, G.; Benckendorff, P. Using brand personality to differentiate regional tourism destinations. J. Travel Res. 2007, 45, 5–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moon, K.S.; Ko, Y.J.; Connaughton, D.P.; Lee, J.H. A mediating role of destination image in the relationship between event quality, perceived value, and behavioral intention. J. Sport Tour. 2013, 18, 49–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryu, K.; Han, H.; Kim, T.H. The relationships among overall quick-casual restaurant image, perceived value, customer satisfaction, and behavioral intentions. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2008, 27, 459–469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Echtner, C.M.; Ritchie, J.R.B. Themeaning and measurement of destinationimage. J. Tour. Stud. 2003, 14, 37–48. [Google Scholar]

- Assaker, G.; Vinzi, V.E.; O’Connor, P. Examining the effect of novelty seeking, satisfaction, and destination image on tourist’sreturn pattern: A two factor, non-linear latentgrowth model. Tour. Manag. 2011, 32, 890–901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Real-Time Statistics on the Distribution of the Epidemic Situation in Hainan. Available online: http://wst.hainan.gov.cn/yqfk/ (accessed on 24 May 2020).

- Zouganeli, S.; Trihas, N.; Antonaki, M.; Kladou, S. Aspects of sustainability in the destination branding process: A bottom-up approach. J. Hosp. Mark. Manag. 2012, 21, 739–757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).