Coordination Analysis of Sustainable Dual-Channel Tourism Supply Chain with the Consideration of the Effect of Service Quality

Abstract

:1. Introduction

- (1)

- How can pricing decisions be made, considering the effect of service quality factors in the operation of tourism enterprises?

- (2)

- How does service quality affect the profits of members of the tourism supply chain?

- (3)

- How can the distribution of benefits be optimised to provide high-quality and efficient tourism services through the coordination of the tourism service supply chain?

2. Literature Review

2.1. Tourism Supply Chain

2.2. Tourism Supply Chain Decision and Coordination

2.3. The Impact of Service Quality on the Tourism Supply Chain

3. Research Methods

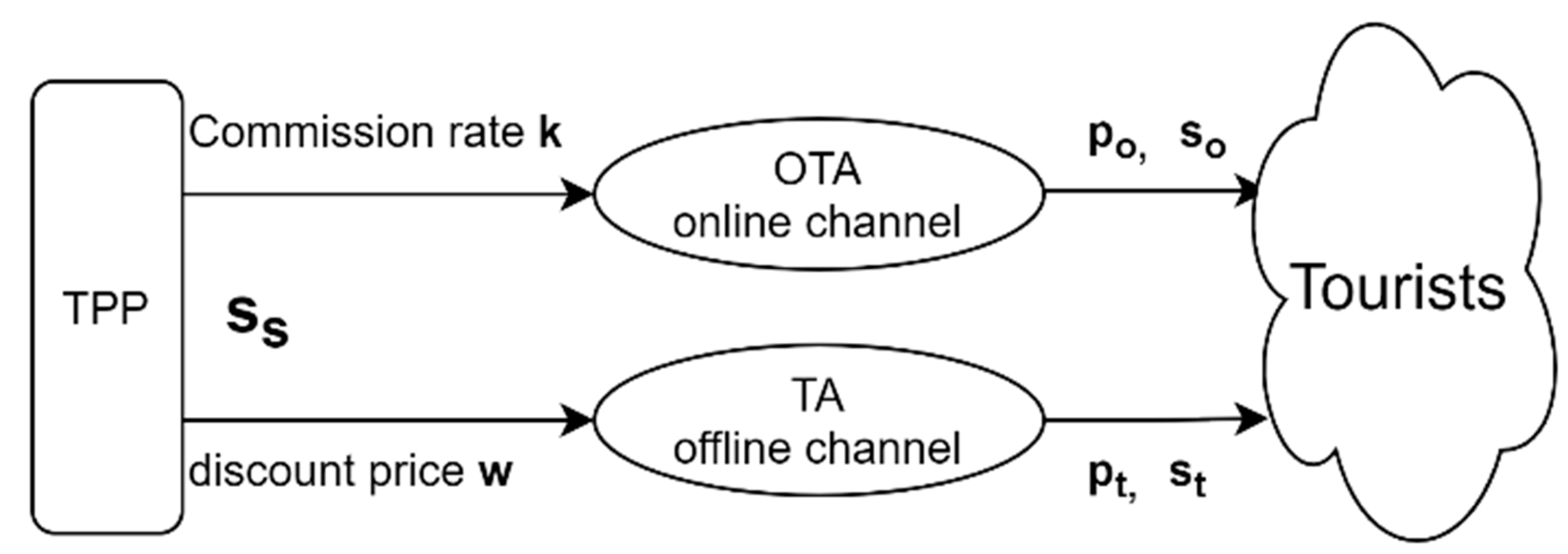

3.1. The Problem Description

3.2. Assumptions

- (1)

- Considering the dual-channel travel supply chain, the OTA and TA provide consumers with the same single tourism product, regardless of tourism product mix or bundled sales.

- (2)

- The tourism supply chain members have no risk preference, are all risk-neutral rational people, regardless of shortages, and both TPP and TA aim to maximise profits.

- (3)

- , tourism products are sold at a higher price than the discounted price, so as to ensure that the tourism business is profitable.

- (4)

- Since the TPP masters tourism resources, the TPP is the leader and the TA is the follower in a Stackelberg game, and it is assumed that consumers have different channel preferences.

4. Model Formulation and Analysis

4.1. Decentralized Decision

- (1)

- The service quality of the TPP is always positively correlated with the sales price of each channel , ;

- (2)

- The service quality of the TA is positively correlated with the price of the offline channels. The effect of the OTA service quality on the online channel prices is related to consumer sensitivity to price and service quality.

- (3)

- The sales prices of the online and offline channels and the service quality of cross-channel are also affected by consumer perceptions of price and service quality.where

- (1)

- (2)

- (3)

4.2. Centralized Decision

- (1)

- The service quality of the TPP has a positive effect on the price and demand of both channels, ;

- (2)

- The quality of channel service is positively related to its own channel price and demand, ;

- (3)

- The service quality of competitive channels is negatively related to the channel demand, and the effect on the price is related to the type of consumers, When, .

- (1)

- ;

- (2)

- ;

- (3)

- ,

- (1)

- The improvement of the TPP’s service quality will win more consumers. Consumers are willing to buy tourism products through any channel, the market demand of the channel will increase, and the price will also increase;

- (2)

- In order to deal with channel conflicts, the OTA and TA win more consumers and increase market share by improving service quality, but service quality improvement will also bring a cost increase, and the OTA and TA will balance the extra service cost by increasing the price of goods;

- (3)

- The improvement in the service quality of the competitive channel will lead to a decrease in the demand for their own channel. When the service level of their own channel is constant, the service sensitivity of the competitive channel is greater than that to the price of the competitive channel, the improvement of the service quality of the competitive channel will increase the sales volume of the competitive channel. The OTA or TA will attract consumers by reducing prices. When consumers are not sensitive to pricing, the improvement of the service quality of competing channels reduces the demand for their own channels. At this time, their own channels can only rely on raising prices to maintain profits.

4.3. Model Comparison Analysis

4.4. Supply Chain Coordination

5. Numerical Analysis

5.1. Analysis of the Effect of the TPP Service Quality

5.2. Analysis of the Effect of the OTA and TA Service Quality

- (1)

- The effect of the OTA and TA service quality on channel prices.

- (2)

- Effect of the OTA and TA service quality on the channel demand.

- (3)

- The effect of the OTA and TA service quality on profits.

5.3. Comparative Analysis under Contract Coordination

6. Conclusions and Managerial Implications

6.1. Conclusions

- (1)

- The effect of service quality on price and demand: whether under centralised decision-making or decentralised decision-making, TPP’s service quality and service quality have a positive effect on online and offline channel sales prices and channel demand. This shows that travel consumers are more willing to pay for high-quality travel experiences. For the OTA and TA, the quality of channel services will also affect the price and demand of channels in the process of selling tourism products. The demand for the online channel will increase with an improvement in OTA service quality. The demand for the lower channel will increase with an improvement in TA service quality. With the improvement of the OTA service quality, the sales price of the channel will also increase with an improvement in the service quality of the channel, but the price of the competitive channel will not necessarily decrease, and the price of the competitive channel will change, as it is affected by consumer sensitivity to price and service. Improving the service quality of the OTA and TA will increase the profit of the TPP. The profits of the OTA and TA always decrease with an improvement in the service quality of competing channels, and an improvement in the service quality of their own channels will make their own profits first rise and then decline.

- (2)

- The effect of service quality on profits: the improvement of TPP service quality can attract more consumers to buy travel products, and the profits of OTAs and TAs will increase. The service quality of TPP should not be too high, however. The excessive pursuit of service quality will increase the cost burden for TPP, but will reduce TPP’s profit. TPP service is therefore always beneficial to OTA and TA, but under certain conditions, it is beneficial to TPP. This conclusion is roughly the same as that of Peng et al. [54]. The overall profit of the supply chain will also increase with an improvement in TPP service quality.

- (3)

- By designing a wholesale price contract, TPP provides a lower wholesale price, so that the revenue of the tourism supply chain under the coordination mechanism can reach the revenue level of the tourism supply chain under centralised decision-making. Under the wholesale price contract, the profits obtained by all members of the supply chain are higher than the profits obtained by each member under pre-contract decentralised decision-making. The wholesale price contract can perfectly coordinate the dual-channel tourism supply chain, which contributes to the research on the sustainable development of the tourism supply chain.

6.2. Theoretical Contributions

6.3. Practical Implications

6.4. Limitations

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Amaro, S.; Duarte, P. Online travel purchasing: A literature review. J. Travel Tour. Mark. 2013, 30, 755–785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Simarmata, J.; Rs, M.; Keke, Y.; Panjaitan, F. The airline customer’s buying decision through online travel agent: A case study of the passengers of scheduled domestic airlines in Indonesia. Int. J. Econ. Commer. Manag. U. K. 2016, 3, 335–349. [Google Scholar]

- Chang, Y.W.; Hsu, P.Y.; Lan, Y.C. Cooperation and competition between online travel agencies and hotels. Tour. Manag. 2019, 71, 187–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, H. Tourism Supply Chain Management; Routledge: London, UK, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Giri, B.C.; Roy, B. Dual-channel competition: The impact of pricing strategies, sales effort and market share. Int. J. Manag. Sci. Eng. Manag. 2016, 11, 203–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szpilko, D. Tourism supply chain–overview of selected literature. Procedia Eng. 2017, 182, 687–693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, J.; Jeong, E. Service quality in tourism: A systematic literature review and keyword network analysis. Sustainability 2019, 11, 3665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Mai, A.; Thi, K.; Thi, T.; Le, T. Factors influencing on tourism sustainable development in Vietnam. Manag. Sci. Lett. 2020, 10, 1737–1742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhat, M.A. Tourism service quality: A dimension-specific assessment of SERVQUAL. Glob. Bus. Rev. 2012, 13, 327–337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nezdoyminov, S.; Bedradina, G.; Ivanov, A. Digital technology in the management of quality service in tourism business. Int. J. Eng. Adv. Technol. 2019, 9, 1865–1869. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jena, S.K.; Jog, D. Price competition in a tourism supply chain. Tour. Econ. 2017, 23, 1235–1254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, D. Innovation of tourism supply chain management. In Proceedings of the 2009 International Conference on Management of e-Commerce and e-Government, Nanchang, China, 6 October 2009; pp. 310–313. [Google Scholar]

- Tapper, R.; Font, X. Tourism Supply Chains: Report of A Desk Re-Search Project for the Travel Foundation; Leeds Metropolitan University, Environment Business & Development Group, England, 2004. Available online: http://www.lmu.ac.uk/lsif/the/tourism-supplychains.pdf (accessed on 6 September 2004).

- Li, W.L.; Yan, H.P.; Li, P. Several problems regarding the study of tourism supply chain. Tour. Trib. 2007, 9, 92–96. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, X.; Song, H.; Huang, G.Q. Tourism supply chain management: A new research agenda. Tour. Manag. 2009, 30, 345–358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Chen, P. Efficient tourism website design for supply chain management. In International Conference on Information and Business Intelligence; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2011; pp. 660–665. [Google Scholar]

- Xu, H.Q.; Qi, Q.; Wang, K.W. Research on construction of tourism Supply Chain based on network Environment. Commer. Res. 2013, 3, 205–211. [Google Scholar]

- Babu, D.E.; Kaur, A.; Rajendran, C. Sustainability practices in tourism supply chain: Importance performance analysis. Benchmarking Int. J. 2018, 25, 1148–1170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Slusarczyk, B.; Smolag, K.; Kot, S. The supply chain of a tourism product. Актуальні Прoблеми Екoнoміки 2016, 5, 197–207. [Google Scholar]

- Christodoulidou, N.; Connolly, D.J.; Brewer, P. An examination of the transactional relationship between online travel agencies, travel meta sites, and suppliers. Int. J. Contemp. Hosp. Manag. 2010, 22, 1048–1062. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, J.; Hong, L. Studies on building of tourism supply chain based on network supplier. In Proceedings of the 2011 IEEE 3rd International Conference on Communication Software and Networks, Xi’an, China, 27–29 May 2011; pp. 149–152. [Google Scholar]

- Huang, M.; Shu, B.Y. Research on the construction of a new tourism supply chain with online tourism service providers as the core. Hubei Soc. Sci. 2015, 4, 83–88. [Google Scholar]

- Guo, H.; Zhang, X. Coordination Model of Consumer Information Sharing in the Online Tourism Supply Chain. Proc. Bus. Econ. Stud. 2021, 4, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hua, M.; Tang, H.; Lai, I.K.W. Game theoretic analysis of pricing and cooperative advertising in a reverse supply chain for unwanted medications in households. Sustainability 2017, 9, 1902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Zhong, Y.; Guo, F.; Tang, H.; Chen, X. Research on coordination complexity of E-commerce logistics service supply chain. Complexity 2020, 2020, 7031543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, S.; Tang, H.; Lin, Z. Inventory and ordering decisions in dual-channel supply chains involving free riding and consumer switching behavior with supply chain financing. Complexity 2021, 2021, 5530124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Y. Price Competition in Tourism Supply Chain with Hotels and Travel Agency. In LTLGB 2012; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2013; pp. 489–495. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, L.; Ji, J.; Chen, K. Game models on optimal strategies in a tourism dual-channel supply chain. Discret. Dyn. Nat. Soc. 2016, 2016, 5760139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Zhao, L.; Chen, Z. Vertical cooperative advertising in a tourism supply chain considering consuming preference. J. Syst. Manag. 2018, 4, 753–760+768. [Google Scholar]

- Huang, X.; Zhu, S.; Wang, J. Optimal Emission Reduction and Pricing in the Tourism Supply Chain Considering Different Market Structures and Word-of-Mouth Effect. Sustainability 2021, 13, 3893. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lv, X.Y.; Xu, H.; Yin, M. A game analysis of the relationship of tourism supply chain enterprises based on the theory of channel power. Tour. Trib. 2010, 25, 23–27. [Google Scholar]

- Dong, J.; Shi, Y.; Liang, L.; Wu, H. Comparative analysis of underdeveloped tourism destinations’ choice of cooperation modes: A tourism supply-chain model. Tour. Econ. 2012, 18, 1377–1399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wan, X.; Jiang, B.; Qin, M.; Du, Y. Pricing decision and coordination contract in low-carbon tourism supply chains based on altruism preference. Environ. Eng. Manag. J. 2019, 18, 2501–2518. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, Y.; Xiao, T.; Fan, Z.P.; Zhao, X. Pricing, environmental governance efficiency, and channel coordination in a socially responsible tourism supply chain. Int. Trans. Oper. Res. 2019, 26, 1025–1051. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wan, X.; Jiang, B.; Li, Q.; Hou, X. Dual-channel environmental hotel supply chain network equilibrium decision under altruism preference and demand uncertainty. J. Clean. Prod. 2020, 271, 122595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, S.; He, Y.; Gu, R. Joint service, pricing and advertising strategies with tourists’ green tourism experience in a tourism supply chain. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2021, 61, 102563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parasuraman, A.; Zeithaml, V.A.; Berry, L.L. Servqual: A multiple-item scale for measuring consumer perceptions of service quality. J. Retail. 1988, 64, 12–40. [Google Scholar]

- Ghobadian, A.; Speller, S.; Jones, M. Service quality: Concepts and models. Int. J. Qual. Reliab. Manag. 1994, 11, 43–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Gummesson, E. Qualitative Methods in Management Research; Sage: Newcastle-upon-Tyne, UK, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Ismail, A.; Alli, N.; Abdullah, M.M.; Parasuraman, B. Perceive value as a moderator on the relationship between service quality features and customer satisfaction. Int. J. Bus. Manag. 2009, 4, 71–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- ISO. Improving Customer Satisfaction with Updated ISO Series of Standards. 2018. Available online: https://www.iso.org/news/ref2312.html (accessed on 5 May 2022).

- Ţîţu, M.A.; Răulea, A.S.; Ţîţu, Ş. Measuring service quality in tourism industry. Procedia Soc. Behav. Sci. 2016, 221, 294–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Akroush, M.N.; Jraisat, L.E.; Kurdieh, D.J.; AL-Faouri, R.N.; Qatu, L.T. Tourism service quality and destination loyalty–the mediating role of destination image from international tourists’ perspectives. Tour. Rev. 2016, 71, 18–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoon, Y.; Cha, K.C. A qualitative review of cruise service quality: Case studies from Asia. Sustainability 2020, 12, 8073. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, C.T.; Lee, C.; Chen, W.Y. An expert system approach to assess service performance of travel intermediary. Expert Syst. Appl. 2009, 36, 2987–2996. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amin, M.; Yahya, Z.; Ismayatim, W.F.A.; Nasharuddin, S.Z.; Kassim, E. Service quality dimension and customer satisfaction: An empirical study in the Malaysian hotel industry. Serv. Mark. Q. 2013, 34, 115–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Albayrak, T.; Caber, M.; Hutcheson, G.D.; Moutinho, L. The Main and Interaction Effects of Package Tour Dimensions on the Russian Tourists’ Satisfaction. J. Qual. Assur. Hosp. Tour. 2016, 17, 274–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian-Cole, S.; Cromption, J.L. A conceptualization of the relationships between service quality and visitor satisfaction, and their links to destination selection. Leis. Stud. 2003, 22, 65–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haghkhah, A.; Nosratpour, M.; Ebrahimpour, A.; Hamid, A.B.A. The impact of service quality on tourism industry. In Proceedings of the 2nd International Conference on Business and Economic Research, Langkawi, Malaysia, 14–15 March 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Kachwala, T.; Bhadra, A.; Bali, A.; Dasgupta, C. Measuring customer satisfaction and service quality in tourism industry. SMART J. Bus. Manag. Stud. 2018, 14, 42–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferri Sanz, M.; Durá Ferrandis, E.; Garcés Ferrer, J. Service quality scales and tourists with special needs: A systematic review. Sustainability 2019, 11, 3844. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Lai, I.K.W.; Hitchcock, M.; Yang, T.; Lu, T.W. Literature review on service quality in hospitality and tourism (1984–2014): Future directions and trends. Int. J. Contemp. Hosp. Manag. 2018, 30, 114–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, S.; Du, S.F.; Liang, L.; Dong, J.F. Optimal quality decision in tourism supply chain for package holidays. J. Manag. Sci. China 2009, 12, 37–43. [Google Scholar]

- Peng, H.; He, Y.; Xu, F. Pricing strategy and service innovation decision in the customized tourism supply chain. In Proceedings of the Symposium on The Service Innovation under the Background of Big Data & IEEE Workshop on Analytics and Risk (the 4th), Hainan, China, 4 November 2017; pp. 90–102. [Google Scholar]

- Jena, S.K.; Meena, P.L. Price and service competition in a tourism supply chain. Serv. Sci. 2019, 11, 279–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, L.; Zhang, M. Conformance quality of the dual-channel tourism supply chain under tourists’ quality preference. J. China Tour. Res. 2020, 18, 1–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsay, A.A.; Agrawal, N. Channel dynamics under price and service competition. Manuf. Serv. Oper. Manag. 2000, 2, 372–391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dan, B.; Zhang, S.; Zhou, M. Strategies for warranty service in a dual-channel supply chain with value-added service competition. Int. J. Prod. Res. 2018, 56, 5677–5699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, W.H.; Hu, J.S. Study of Dynamic Pricing and Service Decision in Supply Chain Integrating Online and Offline Channel. Oper. Res. Manag. Sci. 2021, 12, 84–91. [Google Scholar]

- Xiao, D.; Yuan, J.X.; Bao, X. Supply chain coordination strategy considering dual competition from price and quality. Chin. J. Manag. Sci. 2013, 21, 82–88. [Google Scholar]

- Giri, B.C.; Sarker, B.R. Coordinating a two-echelon supply chain under production disruption when retailers compete with price and service level. Oper. Res. 2016, 16, 71–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Enz, C.A.; James, E.C. Beyond channel mix management: Building within online travel agencies (OTA) metrics and strategies. J. Revenue. Pricing. Manag. 2017, 16, 109–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, E.J.; Bao, Y. Price competition with integrated and decentralized supply chains. Eur. J. Oper. Res. 2010, 200, 227–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Author | Supply Chain Structure | Whether Consider Service Factors | Game Process | Coordination |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dong, J., Shi, Y., Liang, L., and Wu, H. [32] | One tour operator and two tourism destinations | N\A | Stackelberg | Quantity discount contract |

| Yang, L., Ji, J., and Chen, K. [28] | Dual-Channel | N\A | Bertrand and Stackelberg | Wholesale |

| Jena, S. K., and Jog, D. [11] | Two-Echelon TSC | N\A | Local operator, tour operator, integrated Stackelberg | Cooperative advertising Two-part tariff contract |

| Peng, H., He, Y., and Xu, F. [54] | Two-echelon tourism supply chain | TAP and TA provide services | Stackelberg | N\A |

| Jena, S. K., and Meena, P. L. [55] | Two-Echelon TSC | Only tour operator provides services | Stackelberg | Sharing Surplus |

| Wan, X., Jiang, B., Qin, M., and Du, Y. [33] | Single-Channel | N\A | Stackelberg | Revenue-sharing contracts |

| Huang, L., and Zhang, M. [56] | Dual-Channel | Only tour retailer provides extra service | Stackelberg | Two-part tariff contract |

| Huang, X., Zhu, S., and Wang, J. [30] | Single-Channel | N\A | Stackelberg and Nash | N\A |

| This study | Dual-Channel Consider OTA participation on sale | Consider TP, OTA, TA provide services | Stackelberg | Wholesale Price, Income distribution contract |

| Decision Variables | Description |

| Offline sales price of tourism products | |

| Online sales price of tourism products | |

| Wholesale price from the TPP to the TA | |

| Symbol | Description |

| The TPP service quality | |

| The OTA online channel service quality level | |

| The TA offline channel service quality level | |

| Potential market demand | |

| Price Sensitivity of Demand | |

| Sensitivity of channel demand to service quality | |

| Online channel demand | |

| Offline channel demand | |

| Profit of the TPP | |

| Profit of the TA | |

| Profit of the OTA | |

| Total profit of the TSC |

| Centralized decision | 113.99 | 121.01 | N/A | 18.50 | 31.00 | N/A | N/A | N/A | 5348.6 |

| Decentralized decision | 119.63 | 136.25 | 116.08 | 24.74 | 20.17 | 4284.2 | 560.00 | 374.66 | 5218.8 |

| 0.801 | 98.22 | 4284.3 | 560 | 504.38 | 5348.6 |

| 0.804 | 98.73 | 4300.3 | 560 | 488.33 | 5348.6 |

| 0.807 | 99.25 | 4316.4 | 560 | 472.29 | 5348.6 |

| 0.81 | 99.77 | 4332.4 | 560 | 456.24 | 5348.6 |

| 0.813 | 100.29 | 4348.4 | 560 | 440.19 | 5348.6 |

| 0.816 | 100.81 | 4364.5 | 560 | 424.15 | 5348.6 |

| 0.819 | 101.32 | 4380.5 | 560 | 408.1 | 5348.6 |

| 0.822 | 101.84 | 4396.6 | 560 | 392.06 | 5348.6 |

| 0.825 | 102.36 | 4412.6 | 560 | 376.01 | 5348.6 |

| 0.8253 | 102.41 | 4413.94 | 560 | 374.66 | 5348.6 |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Wang, X.; Lai, I.K.W.; Tang, H.; Pang, C. Coordination Analysis of Sustainable Dual-Channel Tourism Supply Chain with the Consideration of the Effect of Service Quality. Sustainability 2022, 14, 6530. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14116530

Wang X, Lai IKW, Tang H, Pang C. Coordination Analysis of Sustainable Dual-Channel Tourism Supply Chain with the Consideration of the Effect of Service Quality. Sustainability. 2022; 14(11):6530. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14116530

Chicago/Turabian StyleWang, Xiangping, Ivan Kai Wai Lai, Huajun Tang, and Chuan Pang. 2022. "Coordination Analysis of Sustainable Dual-Channel Tourism Supply Chain with the Consideration of the Effect of Service Quality" Sustainability 14, no. 11: 6530. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14116530

APA StyleWang, X., Lai, I. K. W., Tang, H., & Pang, C. (2022). Coordination Analysis of Sustainable Dual-Channel Tourism Supply Chain with the Consideration of the Effect of Service Quality. Sustainability, 14(11), 6530. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14116530