Abstract

Successful climate change mitigation requires the commitment of rapidly developing low-income countries. Although most of them have strategies to tackle a fair share of the burden, implementation is low despite large amounts of international aid. We aimed to identify the dynamics underpinning their low implementation, using Nepal as a case study. Aid-dependent Nepal is vulnerable to climate change and committed to its mitigation while pursuing democracy and development. We applied an institutional analysis and development framework as well as an institutional grammar tool to analyze national climate policy. We found that the current national institutions did not enable effective climate change mitigation. Despite relevant political decisions being made, the arrangements were enacted slowly. Contrary to development issues, climate issues were not tackled across all of the relevant sectors, such as waste management, traffic, and agriculture, nor across governance levels, while there was little coherence between development and climate policies. Instead, community forestry was set in the main charge of climate actions, as explained by the history of development collaboration. Additionally, climate education was mainly addressed to local communities rather than to decision-makers. We conclude that building local institutions and funding addressed effectively, even to local actors, are key options to improve the implementation of the national climate strategies of Nepal and low-income countries.

1. Introduction

The climate crisis, as a major collective action problem, reveals the conflicting interests between parties [1] To extend and manage the global commons, such as the climate, understanding the barriers and enablers of national climate actions through the perspective of less-powerful nations and people is needed [2]. Low-income countries are committed to carrying a fair share of the mitigation burdens if they have access to sufficient resources, as stated in the nationally determined contributions (NDCs) [3].

While the NDCs framework of the Paris Agreement explicitly allows countries to simultaneously consider national policies and global climate objectives [4], often the attributes of communities where climate actions take place and the interactions between states are neglected, leading to an unclear picture of the decision-making process in climate change [5]. Furthermore, the success of international agreements has been evaluated on the basis of measurable environmental impacts [6], human health [7], technology transfers [8], and people’s experiences [9]. However, the dynamics and causes underlying the successes or failures remain unknown.

To address this gap, qualitative case study methods allow investigations into how institutional arrangements shape policy outcomes, and institutional analyses offer a systematic basis for characterizing key institutional features. The IAD framework enlightens the institutional, technical, and participatory aspects of collective action problems and their effects [10]. The institutional analysis and development (IAD) framework, which relies on formal political science theories (e.g., game theory and state theory), has been applied to evaluate activities aimed at tackling environmental challenges [11] in LDCs [12]. However, previous studies have not employed systematic institutional analytical frameworks, such as the IAD framework, to analyze national climate policies, despite the fact that, according to Cole [13], formal legal rules should play a more substantial role in these types of analyses than they have thus far.

Our aim was to determine to what degree an LDC implements their nationally determined contribution in their national climate change mitigation strategy, as well as the underlying causal dynamics, in a country committed to a fair share of climate change mitigation and receiving notable development funding. Since Nepal is one of the most vulnerable countries to climate change and is committed to mitigation, while also being among the largest receivers of development investments [14]. Nepal has an ambition to achieve net-zero emissions by 2045 with a fairly open, and functioning society, we used Nepal as a case study. Nepal is part of the Least Developed Countries (LDC) Coordination Group in the UN Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC). This group participates in negotiations on UNFCCC processes on behalf of 48 LDCs and advocates for poor as well as climate-vulnerable people. It was established specifically to help countries implement their nationally determined contributions by 2020.

According to the climate action tracker, the emissions are compatible with the Paris Agreement but are still growing. Additionally, the country has made significant progress in establishing institutional mechanisms with international support. We applied the IAD framework and the institutional grammar tool (IGT) [15] to enable a systematic analysis of the national governance of the climate as a global common.

2. Research Design

Institutions here determine the “formal rules and arrangements that govern behavior among and within organization” [16], establishing shared practices through which actors address their mutual interdependencies, playing a key role in climate change decisions, addressing risks, and mobilizing climate finances [17]. Climate governance is about forming these institutions and addressing natural resources with collectively acceptable principles [18].

2.1. Institutional Analysis and Development Framework

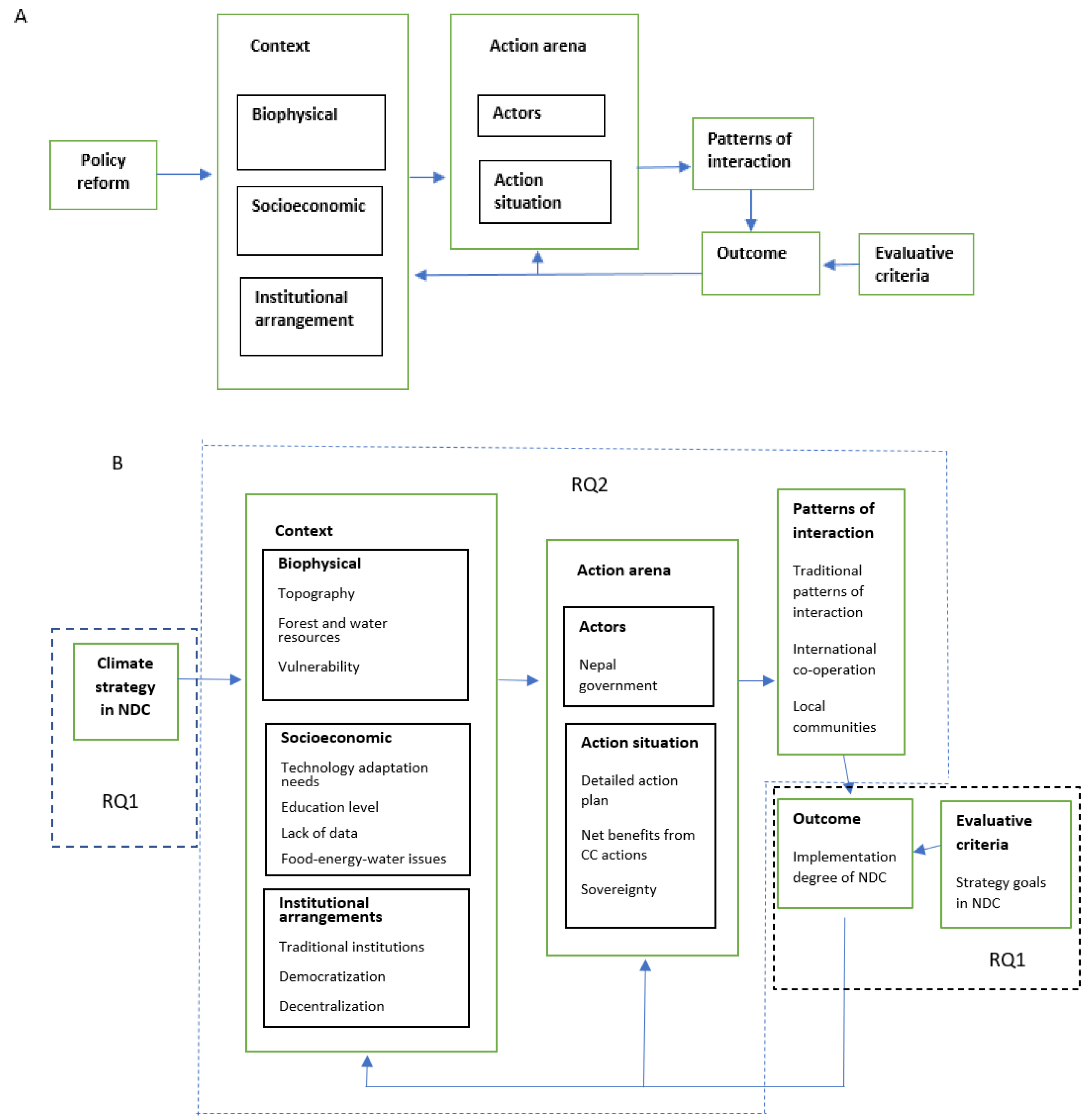

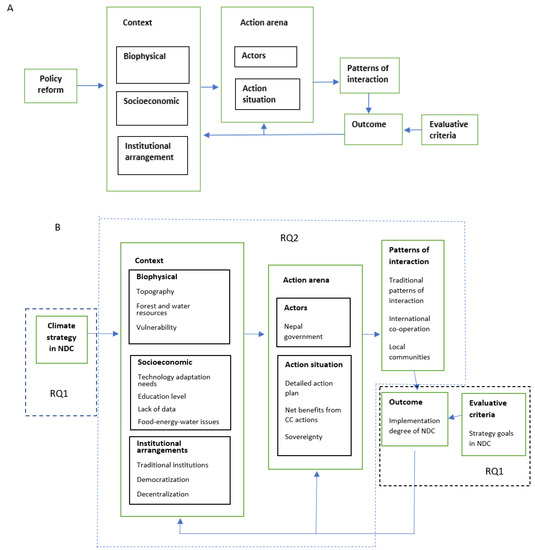

To build the IAD framework (Figure 1A), [15] used extensive empirical studies on governing natural resources to improve the tragedy of the commons, arguing that some communities can develop institutions to manage resource overuse, which would otherwise lead to climate change. Subsequently, Ostrom et al. [19] and Andersson [20] also utilized and further adapted this theoretical framework. The IAD framework has been applied to investigate the physical world, communities, and their rules, and to evaluate policy effectiveness, initiate policy reforms, and design new policy interventions.

Figure 1.

The IAD framework and its operationalization in the climate policies of Nepal (adapted from Andersson [20]). The bold headlines represent the IAD framework in its general form, and the box contents illustrate this study’s operationalization specific to climate change actions in Nepal. (A) is the general form of the framework and (B) is the operationalized form of the framework.

At the core of the analysis, the action arena consists of the implemented decisions and actions, as well as the most significant actors, such as rural communities, NGOs, and governments. The framework carefully follows the path from strategy formulation to implementation, in which the action arena is the unit of analysis. Patterns of interactions result from the identification of the action arena, finally leading to the evaluation of the outcomes of the policy reform.

Actors respond to policy reforms by creating appropriate rules for the institutional context, but as they are unable to request that official institutions change the rules, they may aim to create informal rules [2]. The policy reform then affects the action arena, where individuals make operational decisions on the physical world.

The very first step involves describing the action arena. Then, the interaction patterns within the action situation led to predictable outcomes, and an analysis of these patterns revealed different actors’ institutional incentives. Therefore, the IAD framework allows us to make assumptions on how and what participants value, as well as the processes they use to decide appropriate strategies.

To clarify the different policy components, we used the institutional grammar tool (IGT), initially formulated by Crawford and Ostrom [12] and Ostrom [21], revised by [22,23], and applied, for example, by Lien et al. [8]. Specifically, the IGT, an analytical approach for deconstructing institutions, is primarily a tool for collecting data and can be used in analyses based on multiple theories [24]. It can be applied to study policy phenomena, such as policy compliance [23], policy divergence [8], policy change [25], or institutional diversity [26]. The IGT provides a prescribed coding structure to identify and dissect institutional statements, such as those found in policies, from legislative directives to organizational bylaws. As the texts in the NDCs were not formulated as statements, we analyzed the sentences as regulatory statements. Additionally, IGT applications generate systematically collected data that may be used to identify (1) the main actors in a system and what they can, must, or cannot do; (2) the spectrum of actions required by a policy, and the associated conditions describing how, when, and where the actions take place; and (3) the objects that receive the action imposed by the actors in the system. The outcomes of the action situation are discovered for further analysis. In the context of this study, we analyzed the observed values in the climate policies.

2.2. Operationalization of the IAD Framework

We operationalized the IAD framework, focusing on policy outcomes to identify the gaps between the climate change mitigation strategies stated in the NDCs and their implementation (Figure 1B). We identified the context in which Nepal’s climate change decisions take place, assuming that actors’ choices and the ways in which climate change mitigation actions are implemented are both context specific. The framework’s operationalization (Figure 1B) emerged from our research questions, which were based on the available literature. Furthermore, operationalization includes identifying the action situations in Nepal and the specific features of Nepal’s government.

2.2.1. Context

In operationalization, we defined the major variables affecting the implementation of climate change mitigation strategies. Nepal is one of the most vulnerable countries to climate change, with millions of people relying on the water that flows from the glaciers, whether for drinking, agriculture, energy, or other purposes. A significant part of the biophysical conditions in Nepal is the forest resources.

In Nepal, the community forest management system has empowered the local community to cooperate with international partners. In fact, Nepal is regarded as a good example of community forest management, showing the way for forest management in other countries [27,28]. However, Nepal has struggled to maintain the desired level of forestation. Despite the ambitious targets, deforestation has increased due to dysfunctional institutions. Local-government-centric forestry has failed to address local needs in forest resource management [27]. Citizens have limited knowledge of government decisions, activities, procedures followed, and their outcomes. This leads to a challenge to the accountability of local governments. They are expected to handle decisions consistent with standards of fairness and equity [29,30].

Nepal’s socioeconomic context is shaped by very low energy security, with the need for modern energy technology. Just over half of households have access to electricity [31]. This poses a threat to natural resources, as people cut down the forest for firewood. A case study from Nepal showed that an increase in education and income, with access to means of mass communication, improves the management of natural resources [32]. Education increases environmental awareness and support for environmental actions [33].

The institutional arrangements have gone through diversification and decentralization. For example, an alternative energy promotion center under the government was established in 1996 to mainstream renewable energy in Nepal. In 2011, one of the objectives of the climate change policy was to establish a climate change center. Additionally, the forestry sector has also undergone a process of decentralization in forest governance, leaving the communities more empowered. Land-use policy 2012 supports this decentralization process by aiming for more equal and fair land ownership.

2.2.2. Action Arena

The Nepal action arena is shaped by a long history of sovereignty. The country has never been occupied by another country. On the other hand, Nepal is highly dependent on development aid. Receiving the best possible benefits from international collaboration, such as climate actions, is vital. In Nepal, protection and liberalization have shaped the natural resource policy [34].

2.2.3. Patterns of Interaction

Patterns of interaction are the results of interactions between actors in an action arena. Sovereignty [3], local communities [35], and the mobilization of finance [36] are among the issues affecting climate change decision-making. International cooperation is one of the most significant issues affecting political decision-making in LDCs [4]. Local communities in Nepal have historically been significant in protecting forest resources, which is vital in facilitating the process of climate change mitigation [37].

The most significant source of funding for Nepal is official development aid, but climate-related funding comes second. In total, over USD 600 million of international funding was provided for climate-change-related actions between 1997 and 2014. However, Nepal has not successfully utilized the funding allocated for climate change mitigation due to the absence of adequately working institutions [38].

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Case Study Approach

The qualitative case study method was a tool to study climate change mitigation as a complex phenomenon within the context of LDCs. The case study method contributes to understanding phenomena in a holistic and real-life context [39,40].

This method allows for the careful examination of the data within a specific context because the framework focuses on the context and situation that influence institutions, enabling insights into the underlying dynamics and comprising wider rules than merely formally binding decisions. For instance, data examination is most often conducted within the context of its use [39,40], such as the situation in which the activity takes place.

Here, we framed the case as the governmental actions implemented after the Paris Agreement, and this binding ensured that our study remained under a reasonable scope. We used qualitative observations from policies and interviews to describe Nepal’s climate change mitigation strategy and deconstructed the policy documents into a number of statements to reveal the structural logic of the policy in question. The first step was the application of the IGT to dissect a policy text into institutional statements. The second step involved institutional statement classification, and the third was configuring the statements according to the target action situation (the intended action situation identified within a policy text). This is of primordial importance because when identifying one or more targeted action situations, the analyst should prioritize determining the desired policy outcome, as certain objectives and principles shape climate actions. The following subsections summarize our detailed analytical steps [10].

3.2. Data

We focused on analyzing the government’s policies as reported in the formal documents that describe both the strategic and political decisions, as well as the implemented actions (Table 1). We examined written documents, such as public policies, laws, regulations, and strategies [41], and retrieved the selected policy documents describing the time frames, scope, actions, and coverage of the plans for GHG emissions from the Government of Nepal’s website. Data collection included using a literature review, one semi-structured key informant interview with a representative from the Alternative Energy Centre (AEPC), conducted in 2016, four recorded interviews and discussions from YouTube, and six strategy documents: the 2011 and 2019 Climate Change Policy documents, Long-term Strategy for Net-zero Emissions [42], the Second National Communication, Nepal’s Nationally Determined Contributions (NDCs), and the Subsidy Policy for Renewable Energy. The strategy documents were retrieved from the government website of Nepal. The recorded interviews were retrieved from YouTube, with the keywords Nepal, climate, and renewable energy.

Table 1.

Data and methods for determining the implementation degree (RQ1) and dynamics (RQ2) at various stages of the study.

The selected strategy documents served to answer both research questions, but the World Bank [43] and interview data were used to further detail our answers to RQ2 (Table 1). Governments create NDCs for the UNFCCC to communicate the ways in which they aim to act on climate change. These reports are part of national and international policy reforms, and Nepal’s NDCs were prepared in 2016 by the Ministry of Population and Environment. Additionally, non-Annex I Parties, such as Nepal, are required to submit their first National Communication within three years of entering the Convention, and every four years thereafter. Specifically, countries provide a description of their national and regional development priorities as well as their objectives and circumstances, on the basis of which they will address climate change and its adverse impacts. On that note, Nepal submitted their Second National Communication in 2014. Furthermore, the Subsidy Policy for Renewable Energy aims to improve energy security for the poor by providing subsidies for renewable energy. Every written policy has a policy design presenting the key elements, such as policy agents, targets, incentives, and sanctions. These elements are linked together, forming a process through which policy objectives are to be realized [41].

3.3. Analytical Method

We used a qualitative content analysis to characterize Nepal’s commitment to implement NDCs in its policies, as presented in the selected strategy documents and our operationalized IAD framework (Figure 1B), and the conditions and dynamics determining this commitment. The operationalized IAD framework (Figure 1B) provided the codes for the qualitative analysis of the selected strategy documents, and the IGT was used as a tool for the analysis. We analyzed the strategy documents based on codes derived from the literature, the commitments to implement NDCs, and the decision-making context, again as described in the literature. The strategies were understood as targets and activities aimed toward a set goal. We retrieved the literature from a university database by searching for appropriate keywords. Our focus was on the factors with which the literature presents expected ambition.

The entire process can be explained as follows (Table 2): We began by operationalizing the IAD framework based on the literature. Then, we coded the NDCs to identify the appropriate evaluation criteria for strategy implementation in political decisions and categorized the codes into themes. Thereafter, we evaluated the political decisions using the evaluation criteria to determine the degree of implementation. Finally, we applied the operationalized IAD framework to the policy documents and expert interviews to understand why there is a gap between the NDCs and policy outcomes. We systematically classified the statements in the selected strategy documents through coding with the help of the IGT and by identifying themes or patterns.

Table 2.

Strategic goals derived from the NDCs.

3.3.1. Step 1: Deriving the Evaluative Criteria (Goals) from the NDCs

Evaluative criteria (goals) were derived from the NDCs (Table 2).

3.3.2. Step 2: Coding Selected Policy Documents According to the Evaluative Criteria

We organized the strategy goals into categories and created subcodes to find the degree of implementation. The evaluative criteria represent the codes describing the most significant goals in the policy documents. These include emerging themes from the context, action arena, and interaction patterns. After coding the evaluative criteria from the selected policy documents, the strategy goals were formulated (Table 3).

Table 3.

Subcodes from the selected policy documents.

The IGT provided a general approach for decoding the components of Nepal’s climate change mitigation strategies, such as the topical subjects, operators, and sanctions, to analyze the prescribed set of written required, allowable, and forbidden actions within formal institutions, such as policies, laws, and regulations. An institutional statement comprises up to six components: (1) attribute, (2) object, (3) deontic, (4) aim, the action itself, (5) the conditions, circumstances under which the action is executed, or (6) the punitive sanction resulting from noncompliance with the institution and based on inspections of the prescribed set of written required, allowable, and forbidden actions [10] Our analysis scored the themes from the documents (Table 4).

Table 4.

Scoring explanations and examples bolded.

3.3.3. Step 3: Codes Supplemented with Retrieved and Conducted Key Informant Interviews

We derived the codes from the literature and used them for coding the selected policy documents (Figure 1B) (Table 3). Afterward, we used the themes that arose from the implementation degrees (RQ1) to determine the underlying dynamics (RQ2). In this step, we focused more on the significant themes that were not highlighted in the selected policy papers. In order to discover the underlying dynamics behind the implementation of the NDCs, we looked into themes (Table 3) in more detail.

Two semi-structured key informant interviews were conducted, analyzed, and synthesized to provide a broader view of the themes that arose from the selected policy documents. The semi-structured interviews were conducted to supplement the findings from the selected policy documents. Interviewees were selected based on their position in Nepal’s climate decision-making. The interviews were carried out in Nepal. The interviews were initiated with the same question: “What are the yet undocumented plans and targets for climate change mitigation?”.

4. Results

4.1. Degree of Implementation

The NDC was prepared as a declaration of shared values to commit to the Paris Agreement rather than a solution to the climate problem. The expectation was that Nepal would receive international aid for policy reform. The aim is to assure the international community that Nepal is on the right track to tackling the collective action problem of climate change. The government was on the path of reducing emissions, indicating that Nepal’s current climate action pathways are consistent with limiting the warming to 2 °C [44]. The implementation is mostly based on forestation, renewable energy, international cooperation, finance mobilization, and local communities (Table 5).

Table 5.

Degree of the implementation of the national climate change mitigation strategy.

Mitigation targets stated in the NDC [45] are related to contextual improvements in the country. Most of the targets are related to the energy sector (mitigation) while two of the targets focused on the forestry sector. In addition, there are targets on research and development and pollution reduction. The energy-related targets are expressed with quantitative measures and time frames. However, the targets related to policy, institutional, and financial arrangements for climate change mitigation have not been expressed in NDC. However, the scale and extent of these arrangements are not in line with other targets.

The NDC (2015) emphasizes the strengthening of the central and local government institutions, as well as the involvement of the private sector and NGOs. Similarly, the Climate Change Policy (2011) and Long-Term Strategy for Net Zero Emissions (2021) focus on broader stakeholder engagement, capacity building, and monitoring.

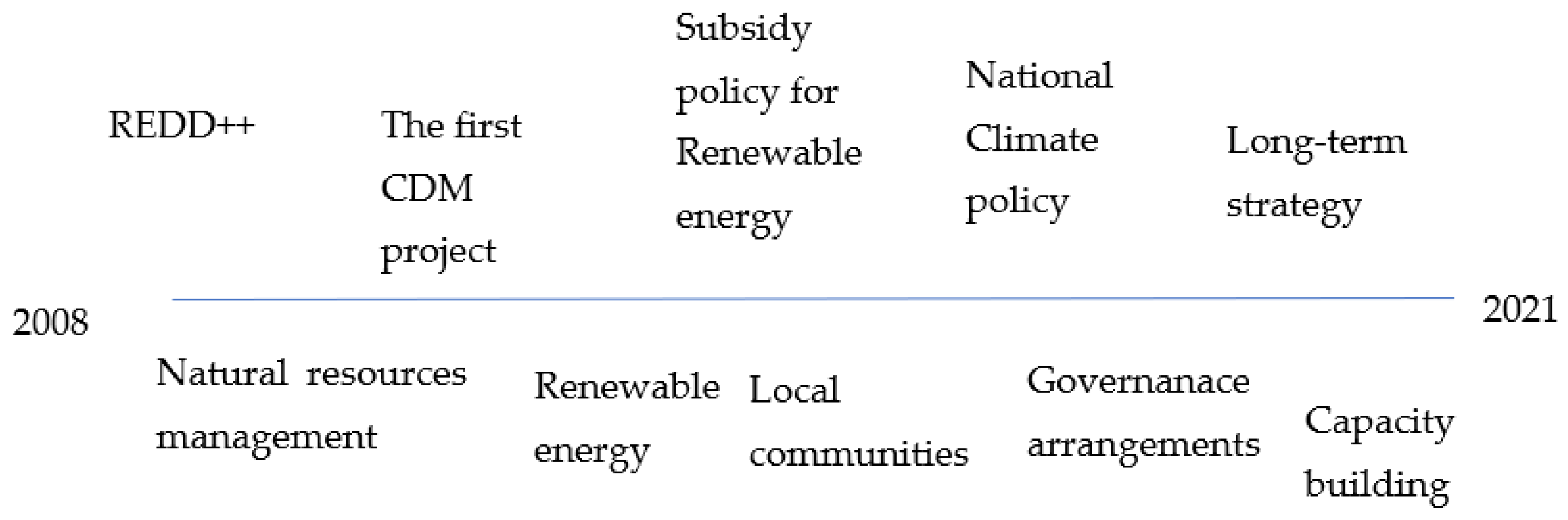

One of the most significant tools in Nepal’s climate change mitigation is forest resources. (Figure 2) The country recognized the need for a scientific approach to forest management in 2011, with the mention of detailed actions; described technology prioritization for the forest sector in 2014; and implemented several programs for forestation in 2019. However, according to World Bank data [43], the total level of natural rents, including forest rents, has remained steady over the last few decades, and the land area under forests was only 25%. Despite several implemented programs, the land area under forests has not reached the targeted 40% level. The NDCs continued this focus on forest resources as the main tool for climate change mitigation. At COP26, Nepal declared to increase forest cover to 45% by 2030.

Figure 2.

Development of Nepal climate strategy.

Another significant theme that emerged was clean and renewable energy (Figure 2). In 2011, the Government of Nepal had a plan to reduce “GHG emissions through additional development and utilization of clean, renewable and alternative energy technologies.” [46]. Renewable energy was mentioned and planned, but detailed action descriptions were missing. In 2014, the government communicated and described the plans to be implemented. Following this, the National Rural Renewable Energy Program (NRREP) was launched in 2015, and the Subsidy Policy for Renewable Energy was established in 2016. In 2019, the production and use of renewable energy were mentioned in the climate change policy, but the NRREP’s results were not communicated. In 2021, the long-term strategy document discussed the possibility to export clean hydropower to neighboring countries, but clear steps for that remained unreported. The largest share of renewable energy in Nepal is represented by biogas and water. Some solar power has also been installed. Nepal has made a commitment to achieving net-zero emissions by 2045 and increasing the share of clean energy in the country’s energy demand to 15% [15].

A theme that did not emerge from the selected policy documents was development goals. Originally, development and poverty reduction were seen as a part of climate change mitigation, but while significant progress in poverty reduction was achieved the development issues have gradually taken up less space in the climate change mitigation strategies. In fact, Nepal mentioned the “failure to mainstream the climate change issues into overall development process” in 2019 [46] as one of the challenges. In addition to describing their contexts, Nepal strongly highlighted the interaction patterns and especially the role of local communities. In 2011, the participation of local communities was described as “mitigation measures based on local knowledge, skills and technologies” and “implementing local climate change-related programs through local institutions by enhancing their capacity.” [47].

In addition to local communities, international cooperation emerged as a theme from the strategy documents, especially significant in terms of receiving climate financing. The plan to mobilize finances was described in 2011 and implemented in 2014. A dedicated climate change budget code was mentioned in 2015, but the challenges for mobilizing finances were brought up in 2016, for which a detailed plan was described in 2019. According to the World Bank data [43], budgetary and financial management quality has remained steady since 2013. The implementation of the NDCs is considered to happen via local communities, even if this brings out challenges such as uncoordinated fragmentation, competition that undermines global norms, and the neglect of important global targets. Local communities do not always play by the same rules as global institutions. In 2021 new themes of economic instruments, government funding, and governance arrangements were highlighted in the strategy.

As seen in Figure 2, the development of Nepal’s climate strategy has moved from natural resource management to wider economic sectors. Later on, an energy strategy with a focus on climate change mitigation, electrification, and energy efficiency across economic sectors was introduced. At first, environmental issues were part of sectoral policies but the Climate policy (2011) was the first dedicated policy for climate issues. However, this policy had a focus on adaptation and resilience actions over mitigation. At first, economic and market-based instruments such as tax rebates and subsidies for private sectors were introduced as tools to implement climate change mitigation actions, but later on, governance arrangements especially in the Long Term Strategy (2021) gained more attention. Paris Agreement and the NDC provided seem to have an influence on the sectoral policies. However, it’s only the climate change policy (2019) and the Long Term Strategy (2021) that provides a reference to these global initiatives. Due to the limited policy and institutional arrangement, Nepal could not achieve some of the NDC’s targets such as education.

4.2. Key Determinants and Dynamics (Drivers) of the National Climate Strategy Implementation

The measures driving climate change mitigation were seen as voluntary, knowledge-demanding, and dependent on good leadership, institutions, and resource allocation. Economy-wide long-term societal changes are lacking because of difficulties with integrating socioeconomic development and climate change, inadequate climate change knowledge, and a focus on lower education levels and awareness-raising, instead of science.

4.2.1. Context in Nepal

The efficient use of natural resources was recognized as a goal but has not been distinguished from economic growth. The targeted level of forestation has also not been reached with political support, and a low-carbon development plan was not highlighted in the strategy documents, despite the fact that climate change mitigation requires a low-carbon development plan. In those documents, the plans were mainly described, but not implemented. Additionally, one of the emerging issues was the regression in renewable energy, meaning lower levels of adopting modern renewable energy, and the lack of local government knowledge [48]. The policy has focussed the climate action across various stakeholders with coordinated efforts. For example, in a long-term strategy.

“Coordinated efforts across the ministries and line agencies, local governments, stakeholders, and rights holders, access to capacity building, technology transfer, and finance will be key to meet targets set.”

As local governments mainly in charge of implementing renewable energy do not necessarily have adequate access to up-to-date knowledge on the topic, their decisions might not be based on the best and most recently available information.

Furthermore, Nepal struggles to integrate climate change mitigation into socioeconomic development, highlighting its status as an LDC and viewing livelihood improvements as a main climate policy outcome. Additionally, the latter are often implicated with adaptation and disaster management. Education was also not highlighted in recent years, despite the fact that, in select policy documents, education is seen as a part of capacity building and a prerequisite for the proper implementation of mitigation measures. This is perhaps because education is infrequently considered a tool for authorities to make better decisions. Rather, it is perceived as a way to empower communities and is often implicated with risk management, health threats, and adaptation instead of mitigation. Improving education appears to be a means of introducing new topics into secondary school curricula and preparing materials for secondary levels. Education and science are understood as being helpful in assisting the improvement of poorer people’s abilities to adapt to climate change. However, the two have mostly been directed at the grassroots level, and thus far related improvements have not involved companies and authorities.

Although the need for profound changes is recognized, the lack of leadership is slowing down the process. During RECON [48], Irene Khan, from the International Development Law Organization, argued that LDCs, such as Nepal, are very much aware of the need to build their legal capacity.

Policies have been introduced to support the targets in NDC, but only the latest policy document, Long Term Strategy (2011) has described the implementation clearly:

“Implement the LTS through federal, provincial, and local governments, in collaboration with other relevant stakeholders including youth, women, indigenous people, private sector as well as international bodies as it covers multidisciplinary areas.”

A climate action budget did not exist in 2016, and although renewable energy subsidies are one of the most significant tools for tackling climate change, the strategy documents do not mention national economic instruments, apart from the Subsidy Policy for Renewable Energy. Finally, capacity building has gained less attention in recent years, but Nepal recognized the related challenges in 2015, declaring the need for international aid, and considered the dearth of institutional capacity as one of the challenges for climate change mitigation in 2019. Specifically, the country mentioned the lack of data on the impact of climate change as a challenge for implementing the NDCs.

The tasks for formal institutions dealing with forestry, energy, agriculture, and industry have not changed much, even if the names of sectoral ministries have changed. At the same time, environmental issues have been added for sectoral ministries. These sectoral ministries have strengthened their engagement with other government organizations at the local level, especially in terms of capacity building.

In addition to these sectoral ministries, high-level institutions such as Climate Change Council and a dedicated Climate Change Management Division in Nepal have been established to manage climate change mitigation.

At the same time tasks of the formal institutions have specialized in climate change mitigation the financial resources have been allocated to climate as well. Dedicated financial resources to implement climate change mitigation actions have been established by both central government and international organizations. The aim of these financial resources has been to empower local communities in climate action.

4.2.2. Action Arena

Nepal has communicated plans to mainstream good governance into climate policy, but according to the World Bank data [43], public administration and rule-based governance quality have not improved since 2013. During the interview, a key informant stated that “policy and institutional reforms are comparatively better than in other countries.” [49]. The government is seen as the most significant actor in policy reform. However, the role of the private sector and other non-state actors had been recognized:

“clarity in roles and responsibilities of all three spheres of Nepal’s governments, engagement of the private sector and other agencies, enhanced stakeholder collaboration [42].”

He also stated that governments should be involved in formulating and implementing effective laws and regulations, whereas financial and technical capacity is expected to come from international partners. Nepal perceives the government as an intermediate that channels funding to local communities who then implement climate change mitigation. Due to this process, one challenge involves the flow of information from the ministry level to different professionals and experts. Coordination of long-term climate strategy is implemented through the Environment Protection and Climate Change, Management National Council, Inter-Ministerial Climate Change Coordination Committee, (IMCCCC), Thematic and Cross-Cutting Working Groups, and Provincial Climate Change, Coordination Committees.

Even though the selected policy documents mention the presence of poor coordination among stakeholders as responsible for climate change risk management and environmental protection, one of our key informants argued that “Nepal has been comparatively better in bringing all the sectors together.” [49].

4.2.3. Interaction Patterns

The strategy documents highlight the need for international funding, but Nepal, nonetheless, struggles to mobilize national funding. According to one of our informants, receiving funding for adaptation is easier if it is integrated with development, but this government-led funding and regulation did not emerge in the strategy documents. [50]

Local agencies supported by the United Nations Development Program were mainly responsible for implementing the climate actions in 2016. In the strategy documents, weak governance is regarded as one of the factors hampering the implementation of mitigation actions. Accordingly, although Nepal has established an Environment-friendly Local Governance Framework, its governance is mainly implicated by adaptations at the local level. Additionally, The Long-Term Strategy was prepared without consultation with the local communities.

“LTS was created in collaboration with several governments, international and national organizations, and government line agencies. A series of consultations were held at the national and provincial levels.”

The uneven distribution of resources and differing interests complicate collaboration between global institutions and local communities. The question as to how global institutions can collaborate effectively and equitably with regional organizations when capacity and resources are not evenly distributed remains.

The international commitments have not been clearly recognized in sectoral policies but the Climate Change Policy (2011) and (2019) were created to answer the international commitment. Furthermore, the Long Term Strategy is strongly based on an international commitment

“Nepal is committed to accelerating climate action while adhering to the Paris Agreement’s common but differentiated responsibilities and respective capabilities.”

5. Discussion

According to our study, forest conservation and renewable energy implemented by local communities with inadequate access to knowledge and data were the main barriers to the implementation of the NDCs as well as the dependence on international support (Table 6). Additionally, a case by Shretsha et al. [32] confirmed a lack of awareness to be one of the barriers to climate actions. However, in the latest strategy document clear plan for acquiring data was presented. Education was planned to empower poor people, but not authorities. The climate change mitigation strategy was based on voluntary actions where knowledge, leadership, institutions, and resource allocation were key, whereas the government’s main role was found to be channeling international funding to local communities yet lacking institutional means to do so and with suboptimal success.

Table 6.

Barriers and enablers of climate policy reform in Nepal.

5.1. Implementation Degree

In Nepal, the implementation of the NDCs depends on international support and mostly occurs via local communities’ forest conservation and renewable energy efforts. Less attention has been granted to governmental regulation and funding, as well as synergy options between climate change mitigation and development. Furthermore, Nepal seems to dismiss the overall positive impacts of long-term measures, such as high-level education and science. Ranabhat et al. [51] conclude that merely setting targets and mobilizing financial resources are not sufficient to effectively address climate change. Policy-based legislation is required, together with adequate institutions and cooperation between governance levels. Our study suggests that these necessary actions are missing in mitigation as well. Policies are more consistent on the motivation level but are less coherent in terms of implementation [51].

5.2. Underlying Dynamics

Climate change mitigation was hardly an issue until the formulation of climate change policy in 2011 and the NDC in 2016. As Nepal moves a step further from a traditional perception of climate change measures. The horizon of the strategy has expanded social issues from the quantity of GHG emissions.

The pathways to gridlocks such as growing multipolarity, institutional inertia, and fragmentation also emerged in Nepal’s mitigation policies/strategies. Specifically, growing multipolarity can be seen in the emphasis on local governments, and these multiple actors in climate governance create a divergence of interests. Institutional inertia appeared in the formal lock-in of decision-making authorities, reflected as a lack of leadership. Difficult problems emerged within Nepal’s severe development issues and lack of decent education that ultimately slow down the process of implementing profound systematic changes to climate change.

5.2.1. Natural Resources and Low-Carbon Development

Nepal’s economy-wide long-term societal changes supporting climate change mitigation are slowed down by its dependence on the use of natural resources. States with natural resources, especially coal, oil, and gas, are trapped in the “resources curse”, slowing down their development [52]. However, forestation is a significant part of Nepal’s climate change policy because afforestation is relatively affordable compared to other policies, such as industry electrification, transport decarbonization, and the large-scale deployment of renewable energy sources. On the other hand, the expansion of forests’ use for carbon sequestration involves trade-offs with the availability of local resources since local people may often be dependent on local firewood as their sole energy source [53].

5.2.2. Socioeconomic Context

Both socioeconomic development and climate change require intervening with people’s free access to natural resources, which involves the risk of contributing to unequal development. Managing resources for climate change mitigation can function to increase conflict over their governance rather than rationalizing their use [12]. However, in Nepal, these aspects were not highlighted in the strategy.

One reason for this might be a failure to connect socioeconomic development and climate change mitigation in policies. The main challenges to implementing climate change education fell into two main categories: local context geographies and the lack of financial support. Financial institutions have a significant role in shaping climate risk management, which is an integral part of the solution for climate change [54]. Connecting global and local knowledge is vital to developing the context-specific understanding of inclusive education in Nepal [55]. Including education and science more profoundly could lead to more efficient climate actions. In the latest strategy document, the role of education and awareness-raising were neglected. From a socioeconomic perspective, Nepal highlighted the role of clean and renewable energy, but as Liu et al. [38] reported, from all socioeconomic factors, technology improvements in low-carbon energy supply sectors have the largest potential to reduce mitigation costs.

If responsibility is passed to the local level without adequate resources, there is a risk of priorities shifting towards simpler local environmental issues rather than more-complicated global climate change [26,56] According to a case study by Poudyal et al. [7] developing the capacity of local forestry officials and inactive community forest user groups and facilitating them to apply forest management interventions.

5.2.3. Governance

Ostrom has identified facilitating conditions and principles associated with long-lasting and sustainable common-pool resources governance [15]. For example, the governing institution should define clear group boundaries. The community should have the right to participate in rulemaking as well as modifying these rules if necessary. In Nepal, the local communities are given heavy responsibility to implement climate strategy but have limited authority on rules as well as access to resources. For example, interviewees from Nepal have stated that the data on GHG is insufficient. The sixth principle concerns graduated sanctions, meaning that the stakeholders who violate the rules are likely to receive graduated sanctions. However, rules regarding climate change mitigation seldom hold any graduated sanctions. This is the case for Nepal as well. The seventh principle concerns local rights to organize. In Nepal, the local communities have been organized to fairly successfully protect forests. Even if there is a higher level of management support and expectations that locals will act on climate change, there may need to be the development of a nested and inclusive system that enables this to occur.

According to Ostrom [21], bottom-up communal polycentric governance can be a solution to overcome complex environmental problems, such as climate change. However, Messori et al. [28] found that local governments face serious difficulties, especially in regard to a lack of personnel and funding. Behind these challenges is an underlying distrust of local communities, a tendency to retain power inequality, a lack of political commitment, and overall weak capacity. In Nepal, local governments also have several other responsibilities in addition to climate change mitigation, such as local market management, environmental protection, biodiversity, agriculture, agroproduct management, and animal health.

In the latest strategy document in 2021, Nepal announced to development of clear lines of communication between different levels of governance (local, provincial, national, and international) and across different sectors and stakeholders. However, the delegation of responsibilities remained unclear.

The Federation of Community Forestry Users, Nepal (FECOFUN) is a formal network of forest user groups (FUGs) that was created in 1995 to allow user groups to have a larger collective voice in national policy issues of concern to forest users [57]. According to Göpfert et al. [58], municipal organizations are becoming increasingly influential in guiding decision-making processes that address climate change mitigation. Their success depends on relevant actors’ cooperation, the creation and maintenance of committees that are able to support implementations, and the institutionalization of climate change mitigation. However, climate change mitigation can be incorporated into all types of committees [59]. Similarly, the bottom-up nature of the Paris Agreement requires strong and coordinated commitments from a variety of actors [60]. Our results do not reflect a strong and coordinated commitment at all levels. Rather, climate change mitigation was seen as voluntary and heavily dependent on international support.

The state’s approach to the management of natural resources has shifted from being state-centric and top-down to a community-based participatory approach to forest management [20]. Increasing the active participation of females, the institution of scientific forest management improved the ecological conditions of the forest and guaranteed a sufficient timber supply. However, because timber is mostly sold to market, the welfare of poor forest households has not been improved. Nepal needs to move from a techno-centric forestry management approach toward more indigenous/traditional approaches [61]. Studies have highlighted that financial and technical support by governments and NGOs play vital roles in directing communities towards resources and eventually improving forest governance [6].

Since the essence of community-based forestry is the participation and ownership of local people to manage their resources according to set management objectives, in recent decades forest management in Nepal has experienced major changes in forest tenure regimes [62,63].

The local communities are seen as a significant factor in climate action and intervention. However, this focus on ‘the local’ is defined through capacities; formal and informal roles as well as responsibilities. A lack of broader participation in strategy formulation seems like an institutional weakness.

The climate institutions have strengthened in Nepal, especially in terms of monitoring and coordination according to the climate strategies. The institutional capacity regarding climate mitigation in Nepal could support initial progress on climate mitigation mainstreaming, particularly in transport, agriculture, and industry sectors. Nepal considers the social issues, fairness, and development in their climate commitment. Therefore, it can be argued that addressing the development and social justice of climate mitigation actions via sectoral policies could benefit the implementation of a climate change mitigation strategy. The institutions should link climate change and development while endorsing authority and decision-making power to the local communities. Inclusive and participatory approaches to both policy design and implementation should be considered.

5.3. Funding

As an LDC, Nepal does not rely on national economic instruments, such as tax revenues, highlighting the need for international funding. Additionally, this funding is based on the assumption that politicians, officials, and citizens will automatically change their behaviors to tackle arising problems if scientists determine a problem’s causes and impacts. However, recent research has discovered that this is not the case. In fact, there are other factors affecting the availability of funding, which should be further explored [64]. For instance, Tenzing et al. [65] suggested the need for more specifically directed funding or fit-for-purpose funds to mainstream climate change issues into development. Under the UNFCCC, climate financing has succeeded in somewhat reducing GHG emissions, but not in improving access to modern renewable energy. Regional cooperation could be a solution to this issue, but it would probably require reorganizing governance [66]. The majority of UNFCCC funding goes through the Government of Nepal to local-level communities that do not always have the best renewable energy knowledge. Our results suggest that climate funding would be more effective if directed to government levels that actually have the authority to implement climate actions.

Efforts to implement ambitious climate change mitigation require fair burden-sharing and adequate funding for all relevant sectors. Value conflicts in global environmental governance are often starkest in these burden-sharing-related issues [67]. Even if Nepal considers development and livelihood as significant, in order to be effective, climate funding should serve science, education, and technology, and not merely forestation projects at the local level. Additionally, a goal-oriented use of instruments supporting international targets could help increase the fairness of mitigation actions [68]. In the case of Nepal, the strategy papers do not highlight the goal-oriented usage of a variety of instruments, but renewable energy subsidies have been introduced. Although international negotiations impose pressures on Nepal, they do not offer the appropriate tools for climate change mitigation, resulting in structural and financial uncertainty.

5.4. International Cooperation

In global climate governance, a vicious circle of “self-reinforcing gridlock” derived from nationalism and protectionism compounds the problems faced by the global community, adding to the conditions that have spurred the rise of nationalism and the anti-global backlash [4]. Tormos-Aponte [18] added that the main challenges include coordination between organizations operating in different contexts, acting with different strategies and around multiple issues, and lobbying multiple decision-making bodies at various levels of government. In Nepal, national policies have long allowed the unregulated exploitation of forest resources. The British influence in forest management in Nepal lead to unsustainable practices of exporting timber and increasing the cuts. Therefore, many communities established their own institutions for local forest management. Community forestry regulations were introduced in the late 1970s, handing over the forests to assure sustainable forest management [69].

Earthquakes, uncertainty, and polarization have shaped Nepal’s politics, ultimately impacting the country’s economy-wide long-term changes [27]. Under deep uncertainty, decision-making needs to account for the motivations and agencies of diverse decision-makers, as well as the interactions between them [16].

According to Roelich and Giesekam [16], mitigation requires a series of logical and ambitious decisions. As such, change will not occur from an isolated decision, but rather from a series of activities supported by adequate institutions in different sectors and over decades. In Nepal, this is happening in the case of forests and natural resources, but not in science and education.

Similar barriers and enablers have been recognized in other countries. Bangladesh [70], there is a need to systematically address the challenges of institutional coordination and cooperation. This includes identifying climate finance opportunities and capacity needs of local institutions to adequately support climate strategies.

In Bhutan [71] the lack of funding emerged as one of the key challenges for upholding carbon neutrality.

6. Conclusions

In developing countries, development, vulnerability, and adaptation issues, frequently reflected in funding and strategy, often marginalize climate change mitigation. Mitigation requires systematic institutional and societal changes led by science, as focusing solely on local forestation projects might impede long-term and cross-sectoral developments. Efforts to implement ambitious climate change mitigation require fair burden-sharing and adequate funding for all relevant sectors. Even if Nepal perceives its development and livelihood as significant, the allocated climate funding might not be effectively used if it does not serve science, education, and technology, and focuses merely on forestation projects at the local level.

As in Nepal, the scope of countries’ climate policies and strategies has expanded over the past few years. Achieving a consensus and agreeing on globally significant issues, such as human rights, has become a prominent concern when dealing with climate change, and this has prevented the establishment of efficient international laws [51]. We conclude that this is mainly due to the fact that climate change is related to larger contextual concepts. Coordinating various efforts in climate change mitigation is crucial; because of the cross-cutting nature of climate change impacts, however, Nepal has struggled in coordinating these efforts. Therefore, climate change mitigation requires more fair and engaging cooperation between governance levels and the sharing of responsibilities guided by the Paris Agreement.

The IAD framework is meant to be generally suitable for addressing complex collective action problems. In our study, the framework did account for the existing local institutions that appeared to be important determinants for the degree of implementation. In other words, the operationalized IAD framework appeared useful for analyzing the national implementation of global climate policies. It aided the process of identifying the gaps between strategy and implementation, enlightening the key factors that researchers or policy makers should consider when analyzing policies or trying to devise new ones. The complexities of different economic growth, development, and climate change mitigation targets present a special challenge, as addressing the action situation and interaction patterns are rather demanding. However, the framework was able to reveal the key challenges in Nepal’s institutional context, while maintaining the contradictions among different targets. Ultimately, the findings can be generalized to LDCs regarding costly global environmental problems.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, M.H., H.K. and M.M.; methodology, M.H., H.K. and M.M.; formal analysis, M.H.; investigation, M.H.; data curation, M.H.; writing—original draft preparation, M.H.; supervision, H.K. and M.M. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

The article was supported by the Finnish Foundation for Technology Promotion.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Aklin, M.; Mildenberger, M. Prisoners of the wrong dilemma: Why distributive conflict, not collective action, characterizes the politics of climate change. Glob. Environ. Politics 2020, 20, 4–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nigussie, Z.; Tsunekawa, A.; Haregeweyn, N.; Adgo, E.; Cochrane, L.; Floquet, A.; Abele, S. Applying Ostrom’s institutional analysis and development framework to soil and water conservation activities in north-western Ethiopia. Land Use Policy 2018, 71, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Winkler, H.; Höhne, N.; Cunliffe, G.; Kuramochi, T.; April, A.; de Villafranca Casas, M.J. Countries start to explain how their climate contributions are fair: More rigour needed. Int. Environ. Agreem. Politics Law Econ. 2018, 18, 99–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hale, T.; Held, D. Breaking the cycle of gridlock. Glob. Policy 2018, 9, 129–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Grubb, M.; Hourcade, J.C.; Neuhoff, K. Planetary Economics; Routledge: London, UK, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Koontz, T.M. We finished the plan, so now what? Impacts of collaborative stakeholder participation on land use policy. Policy Stud. J. 2005, 33, 459–481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poudyal, B.H.; Maraseni, T.; Cockfield, G. Impacts of forest management on tree species richness and composition: Assessment of forest management regimes in Tarai landscape Nepal. Appl. Geogr. 2019, 111, 102078. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lien, A.M.; Schlager, E.; Lona, A. Using institutional grammar to improve understanding of the form and function of payment for ecosystem services programs. Ecosystems 2018, 31 Pt A, 21–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Broto, V.C.; Bulkeley, H. A survey of urban climate change experiments in 100 cities. Glob. Environ. Change 2013, 23, 92–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Ostrom, E. A general framework for analyzing sustainability of social-ecological systems. Science 2009, 325, 419–422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pickering, J.; Persson, Å. Democratising planetary boundaries: Experts, social values and deliberative risk evaluation in Earth system governance. J. Environ. Policy Plan. 2020, 22, 59–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Nagoda, S. New discourses but same old development approaches? Climate change adaptation policies, chronic food insecurity and development interventions in northwestern Nepal. Glob. Environ. Change 2015, 35, 570–579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cole, D.H. Laws, norms, and the Institutional Analysis and Development framework. J. Inst. Econ. 2017, 13, 829–847. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- UNCTAD. The Least Developed Countries Report 2019: The Present and Future of External Development Finance—Old Dependence, New Challenges. 2019. Available online: https://unctad.org/system/files/official-document/ldcr2019_en.pdf (accessed on 8 April 2022).

- Ostrom, E. Governing the Commons: The Evolution of Institutions for Collective Action; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Roelich, K.; Giesekam, J. Decision making under uncertainty in climate change mitigation: Introducing multiple actor mo-tivations, agency and influence. Clim. Policy 2019, 19, 175–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Iacobuta, G.; Dubash, N.K.; Upadhyaya, P.; Deribe, M.; Höhne, N. National climate change mitigation legislation, strategy and targets: A global update. Clim. Policy 2018, 18, 1114–1132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Tormos-Aponte, F.; García-López, G.A. Polycentric struggles: The experience of the global climate justice movement. Environ. Policy Gov. 2018, 28, 284–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ostrom, E.; Gardner, R.; Walker, J.; Walker, J.M.; Walker, J. Rules, Games, and Common-Pool Resources; University of Michigan Press: Ann Arbor, MI, USA, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Andersson, K. Understanding decentralized forest governance: An application of the institutional analysis and development framework. Sustain. Sci. Pract. Policy 2006, 2, 25–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Ostrom, E. Doing institutional analysis digging deeper than markets and hierarchies. In Handbook of New Institutional Economics; Ménard, C., Shirley, M.M., Eds.; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2005; pp. 819–848. [Google Scholar]

- Basurto, X.; Kingsley, G.; McQueen, K.; Smith, M.; Weible, C.M. A systematic approach to institutional analysis: Applying Crawford and Ostrom’s grammar. Political Resour. Q. 2010, 63, 523–537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Siddiki, S.; Weible, C.M.; Basurto, X.; Calanni, J. Dissecting policy designs: An application of the institutional grammar tool. Policy Stud. J. 2011, 39, 79–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Dunlop, C.A.; Kamkhaji, J.C.; Radaelli, C.M. A sleeping giant awakes? The rise of the Institutional Grammar Tool (IGT) in policy research. J. Chin. Gov. 2019, 4, 163–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weible, C.M.; Carter, D.P. The composition of policy change: Comparing Colorado’s 1977 and 2006 smoking bans. Policy Sci. 2015, 48, 207–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feiock, R.C. Institutional collective action and local government collaboration. In Big Ideas in Collaborative Public Management; Blomgren Bingham, L., O’Leary, R., Eds.; Routledge: Abingdon-on-Thames, UK, 2014; pp. 205–220. [Google Scholar]

- Laudari, H.K.; Aryal, K.; Maraseni, T. A postmortem of forest policy dynamics of Nepal. Land Use Policy 2020, 91, 104338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Messori, G.; Brocchieri, F.; Morello, E.; Ozgen, S.; Caserini, S. A climate mitigation action index at the local scale: Methodology and case study. J. Environ. Manag. 2020, 260, 110024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dhungana, S.P.; Satyal, P.; Yadav, N.P.; Bhattarai, B. Collaborative forest management in Nepal: Tenure, governance and contestations. J. For. Livelihood 2017, 15, 27–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dhungana, H.; Maskey, G. Natural resources and social justice agenda in Nepal: From local experiences and struggles to policy reform. Public Policy 2019, 5, 7–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ogino, K.; Nakayama, M.; Sasaki, D. Domestic socioeconomic barriers to hydropower trading: Evidence from Bhutan and Nepal. Sustainability 2019, 11, 2062. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Shrestha, A.; Bishwokarma, R.; Chapagain, A.; Banjara, S.; Aryal, S.; Mali, B.; Korba, P. Peer-to-peer energy trading in micro/mini-grids for local energy communities: A review and case study of Nepal. IEEE Access 2019, 7, 131911–131928. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohai, P.; Twight, B.W. Age and environmentalism: An elaboration of the Buttel model using national survey evidence. Soc. Sci. Q. 1987, 68, 798. [Google Scholar]

- Khanal, K.; Bracarense, N. Institutional Change in Nepal: Liberalization, Maoist Movement, Rise of Political Consciousness and Constitutional Change. Rev. Political Econ. 2021, 33, 145–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sangha, K.K.; Russell-Smith, J.; Costanza, R. Mainstreaming indigenous and local communities’ connections with nature for policy decision-making. Glob. Ecol. Conserv. 2019, 19, e00668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sachs, J.D.; Woo, W.T.; Yoshino, N.; Taghizadeh-Hesary, F. Importance of green finance for achieving sustainable development goals and energy security. In Handbook of Green Finance; Springer: Singapore, 2019; pp. 3–12. [Google Scholar]

- Chhetri, B.B.K.; Johnsen, F.H.; Konoshima, M.; Yoshimoto, A. Community forestry in the hills of Nepal: Determinants of user participation in forest management. For. Policy Econ. 2013, 30, 6–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahat, T.J.; Bláha, L.; Uprety, B.; Bittner, M. Climate finance and green growth: Reconsidering climate-related institutions, investments, and priorities in Nepal. Environ. Sci. Eur. 2019, 31, 46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, R.K. The case study method as a tool for doing evaluation. Curr. Sociol. 1992, 40, 121–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, R.K. Case Study Research: Design and Methods, 3rd ed.; Sage: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Schneider, A.; Ingram, H. Systematically Pinching Ideas: A Comparative Approach to Policy Design. Annu. Rev. Policy Des. 2017, 5, 61–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Government of Nepal. Long-Term Strategy for Net-Zero Emissions. 2021. Available online: https://unfccc.int/documents/307963 (accessed on 1 June 2022).

- World Bank Data. 2021. Available online: https://data.worldbank.org/ (accessed on 8 April 2022).

- Climate Action Tracker. 2021. Available online: https://climateactiontracker.org/ (accessed on 8 April 2022).

- Ministry of Population and Environment. Intended Nationally Determined Contributions. 2016. Available online: https://www4.unfccc.int/sites/submissions/INDC/Published%20Documents/Nepal/1/Nepal_INDC_08Feb_2016.pdf (accessed on 8 April 2022).

- Ministry of Law, Justice and Parlamentary Affairs. National Climate Change Policy, 2076 (2019) of Nepal-English. 2020. Available online: https://mofe.gov.np/downloadfile/climatechange_policy_english_1580984322.pdf (accessed on 8 April 2022).

- Ministry of Environment. Climate Change Policy. 2011. Available online: https://www.lse.ac.uk/GranthamInstitute/wp-content/uploads/laws/1494.pdf (accessed on 8 April 2022).

- Guna Raj Dhakal. Renewable Energy Confederation of Nepal (RECON). Available online: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=YNOaq0M68GM (accessed on 8 April 2022).

- Kantipur TV HD. Dr. Maheshwor Dhakal|Good Morning Nepal|10 November 2019. Available online: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=FDpMIfiQtO8&list=PLwUmS78P9jN2zxQnOaeuaRHR4AsE0v7oG&index=46 (accessed on 8 April 2022).

- IIED. CBA9 Session Interview: Nanki Kaur. Available online: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=r7f5sYwLYi8 (accessed on 8 April 2022).

- Ranabhat, S.; Ghate, R.; Bhatta, L.D.; Agrawal, N.K.; Tankha, S. Policy coherence and interplay between climate change adaptation policies and the forestry sector in Nepal. Environ. Manag. 2018, 61, 968–980. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Badeeb, R.A.; Lean, H.H.; Clark, J. The evolution of the natural resource curse thesis: A critical literature survey. Resour. Policy 2017, 51, 123–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doelman, J.C.; Stehfest, E.; van Vuuren, D.P.; Tabeau, A.; Hof, A.F.; Braakhekke, M.C.; Gernaat, D.E.H.J.; van den Berg, M.; Zeist, W.-J.; Daioglou, V.; et al. Afforestation for climate change mitigation: Potentials, risks and trade-offs. Glob. Change Biol. 2020, 26, 1576–1591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monasterolo, I.; Roventini, A.; Foxon, T.J. Uncertainty of climate policies and implications for economics and finance: An evolutionary economics approach. Ecol. Econ. 2019, 163, 177–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beutel, D.; Tangen, D.; Carrington, S. Building bridges between global concepts and local contexts: Implications for inclusive education in Nepal, Sri Lanka, and Bangladesh. Int. J. Incl. Educ. 2019, 23, 109–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Solecki, W.; Rosenzweig, C.; Dhakal, S.; Roberts, D.; Barau, A.S.; Schultz, S.; Ürge-Vorsatz, D. City transformations in a 1.5 C warmer world. Nat. Clim. Change 2018, 8, 177–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilkie, D.; Painter, M. Factors of success in community forest conservation. Conserv. Sci. Pract. 2021, 3, e388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Göpfert, C.; Wamsler, C.; Lang, W. Institutionalizing climate change mitigation and adaptation through city advisory committees: Lessons learned and policy futures. City Environ. Interact. 2019, 1, 100004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hovi, J.; Ward, H.; Grundig, F. Hope or despair? Formal models of climate cooperation. Environ. Resour. Econ. 2015, 62, 665–688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shrestha, A.; Baral, S. Socioeconomic factors affecting awareness and adaption of climate change: A Case Study of Banke District Nepal. Azarian J. Agric. 2018, 5, 96–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kimengsi, J.N.; Bhusal, P. Community Forestry Governance: Lessons for Cameroon and Nepal. Soc. Nat. Resour. 2022, 35, 447–464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gautam, A.P.; Shivakoti, G.P. Conditions for successful local collective action in forestry: Some evidence from the hills of Nepal. Soc. Nat. Resour. 2005, 18, 153–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghimire, P.; Lamichhane, U. Community Based Forest Management in Nepal: Current Status, Successes and Challenges. Grassroots J. Nat. Resour. 2020, 3, 16–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Overland, I.; Sovacool, B.K. The misallocation of climate research funding. Energy Res. Soc. Sci. 2020, 62, 101349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tenzing, J.; Andrei, S.; Gaspar-Martins, G.; Jallow, B.P. Climate Finance for the Least Developed Countries: A Future for the LDCF? 2016. Available online: https://www.ldc-climate.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/12/ldc-perspectives-on-the-ldcf.pdf (accessed on 8 April 2022).

- Uddin, N.; Taplin, R. Regional cooperation in widening energy access and also mitigating climate change: Current programs and future potential. Glob. Environ. Change 2015, 35, 497–504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paavola, J. Institutions and environmental governance: A reconceptualization. Ecolocy Econ. 2007, 63, 93–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leimbach, M.; Giannousakis, A. Burden sharing of climate change mitigation: Global and regional challenges under shared socio-economic pathways. Clim. Change 2019, 155, 273–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ranjit, Y. History of Forest Management in Nepal: An Analysis of Political and Economic Perspective. Econ. J. Nepal 2019, 42, 12–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fatemi, M.; Okyere, S.A.; Diko, S.K.; Kita, M. Multi-level climate governance in Bangladesh via climate change mainstreaming: Lessons for local climate action in Dhaka city. Urban Sci. 2020, 4, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yangka, D.; Rauland, V.; Newman, P. Carbon neutral policy in action: The case of Bhutan. Clim. Policy 2019, 19, 672–687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).