Integrating SDG 12 into Business Studies through Intercultural Virtual Collaboration

Abstract

:1. Introduction

a practice, supported by research, that consists of sustained, technology-enabled, people-to-people education programmes or activities in which constructive communication and interaction takes place between individuals or groups who are geographically separated and/or from different cultural backgrounds, with the support of educators or facilitators”[20]

- RQ1—How can IVC contribute to raising business students’ awareness of how international companies approach SDG 12 (sustainable consumption) through their marketing communication in different countries?

- RQ2—How can an international and interinstitutional virtual collaboration project contribute to developing students’ intercultural competence while approaching SDGs and marketing communication as content?

2. Materials and Methods

3. Results

3.1. RQ1—How Can IVC Contribute to Raising Business Students’ Awareness of How International Companies Approach SDG 12 (Sustainable Consumption) through Their Marketing Communication in Different Countries?

We can see that (company x) is working towards the SDGs and they have a lot of information about their strategy online. This clearly demonstrates that sustainability is a core part of their business and that they are aware of the damage they are doing to the world currently. In the Netherlands, (company x) boxes also promote that you help plant a tree with every delivered (company’s product) printed on the box.

Both companies also take responsibility in sustainability, and are an example of modern company governance. After all, it is a problem that affects the world, both have some goals in mind to reduce waste and emissions but (company y) has a bit more which is also logical because they are a large company they can afford to invest more into some possible solutions.

However, (company z) is not far away from (company y) in the pursuit to become more sustainable. Both of them establish their dedication towards being sustainable, and indicate it on their websites. The information that is provided there shows that the companies contribute to the Sustainable Development Goals. (company y) has certain goals included in their report, whilst (company z) not mention them specifically yet, which does not mean that they do not already conrtibute towards these goals. This probably has to be due to the size of the company.

Regarding the second model we have chosen, which targets middle class customers, the (company b) is a 100% electric car. This is a clear example of how important is the role played by marketing communication tools in realizing the SDGs we have previously mentioned. This vehicle fits perfectly with (company b)’s objectives mentioned before in their Sustainability Report 2019. We also can see that the company is being coherent with their goals and how the company is taking into account both their economic goals of making profit by selling as well as contributing to the SDGs.

We chose to analyse these three specific products, because we think they represent the SDG’S of (company e) because they are all made of recycled plastic, collected from the sea. This type of action could help achieve the SDG 12, SDG 14 and SDG 15 because it promotes a responsible consumption of sustainable products, they help reduce plastic waste on the oceans and halt the loss of biodiversity.

When talking about cultural facts, as we mentioned before there are some products that are typical in each country and that represent their culture. In the theoretical background we describe some of the dimensions of each country and we see there are many differences between Spain and Netherlands. Those differences may affect in the way they consume when talking about customers, and in the way they produce when talking about companies. For example, taking into account Dutch people are low context, companies need to make their advertisements explicit in order to attract customers. On the contrary, as in Spain people are high context, the relationship with the customers should be spontaneous and with interaction.

In order to analyse how successfully (company i) and (company f) reach their customers in the Netherlands and Spain, our group concluded an analysis of both cultures. Our team took Hofstede dimensions, which may be related to the advertisement and marketing communication perception as a basis for the understanding of cultures.

In the Netherlands people more often get coffee to take with them while catching their train. So in the Netherlands it is more profitable for a company to make sure their coffee is easy to get and does not take a long waiting time to get it. This probably because the Netherlands is a more individualistic country meaning they are not searching as much as other countries to have a fun time with the friends or family at (company y), no they are on there way to work or home and want something to drink on there a way for example in the train. Of course they also have some sales to people that want to sit with friends with a nice cup of coffee but this would most likely be a lower number than in other countries. You can also see this back in their way they promote themselves on social media, they use short videos with updates, of new products that are available in the stores or came back. In the stores, they also mostly show people running towards (company y) while in other countries they show more people sitting to enjoy the (company y) showing the difference in target groups between the Netherlands and other countries.

Culture plays an important role in how international companies promote their products in order to realise their goals of both making profit as well as being sustainable because if a company did not respect sustainability, they would buy any brand. However, Spain, Germany and increasingly more countries are concerned about the well-being of the planet and thus its inhabitants care about the products they buy and how they are made. In the GLOBE webpage, we can see that both countries that we are analysing score high values in “future orientation”, which shows their concern about sustainability among other things. This means that making profits and being sustainable go hand in hand nowadays because they enhance each other. Furthermore, it is important for companies like (company g) and (company h) to demonstrate that they really care about the environment and they have social responsibility if they want to continue being successful. After doing the research and writing this report about (company g), we can better understand how important it is to have knowledge about cultural differences. Besides, we can also see that sustainability is an important factor that companies need to take into account nowadays and all of us are glad that we got to know how some of them do it since sustainability is such an important topic for all of us. Furthermore, we got to see and compare by ourselves the cultural differences that exist between the members of our group and how (company g) adapts its advertisements depending on the country they are focusing on.

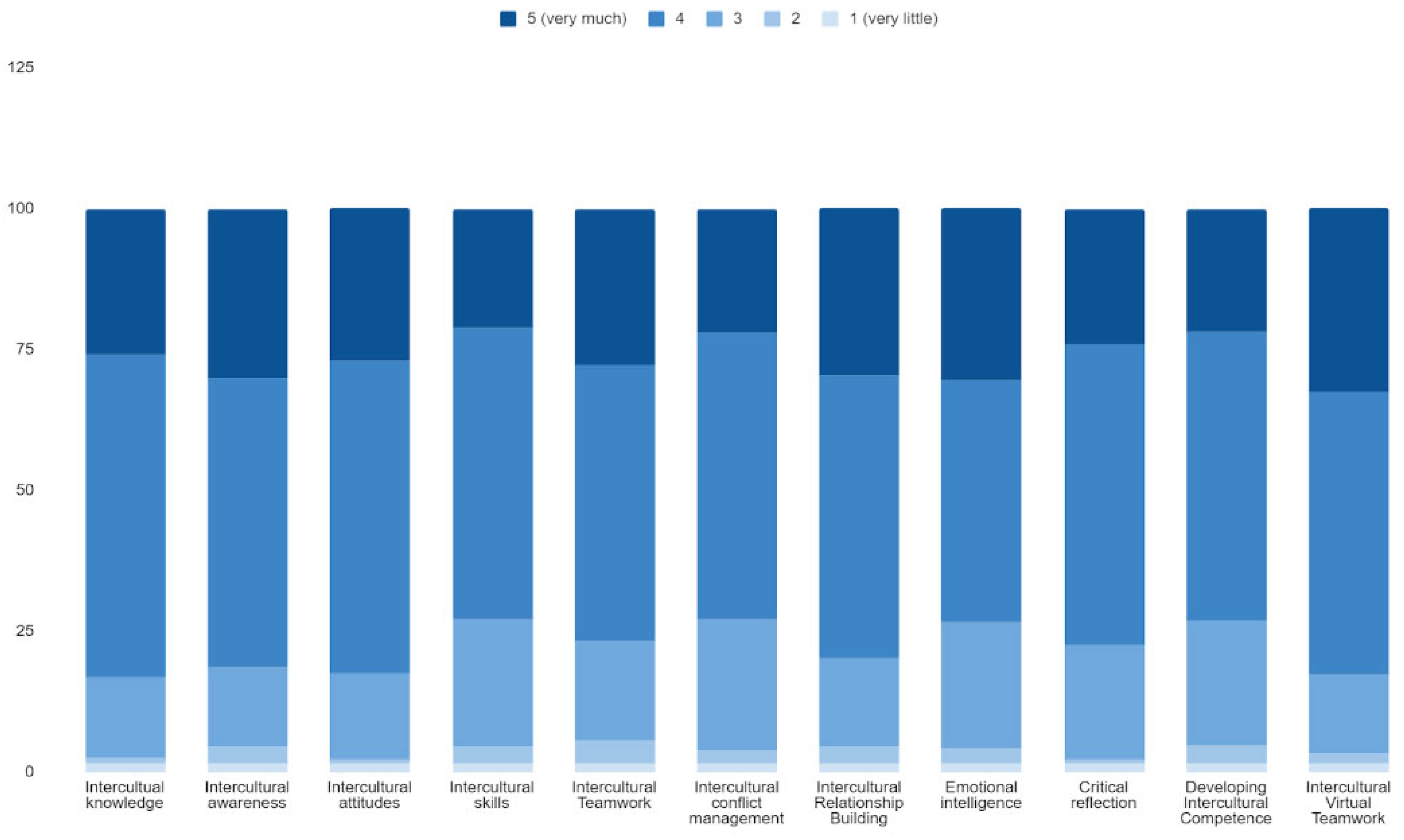

3.2. RQ2—How Can an International and Interinstitutional Virtual Collaboration Project Contribute to Developing Students’ Intercultural Competence while Approaching SDGs and Marketing Communication As Content?

4. Discussion and Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

Appendix B

Appendix C

Appendix D

| Intercultural Competence Dimension | Indicator | Learning Outcome |

|---|---|---|

| Knowledge | K1 | Develop an increased understanding of the concept of culture, how cultures differ and the notion of ‘otherness’ |

| K2 | Gain knowledge of the main concepts related to Intercultural Competence | |

| K3 | Identify vocabulary and concepts that are required in intercultural situations | |

| K4 | Develop an understanding of the relationship between culture-specific knowledge and stereotypes | |

| Awareness | AW1 | Develop intercultural awareness—awareness of differences between cultures |

| AW2 | Increase cultural self-awareness—awareness of oneself as a cultural being and of the fact that our own behaviour, views and reactions are conditioned by our own cultures | |

| AW3 | Increase awareness of specific cases when cultural conditioning is at play—not only knowing that culture is supposed to influence human behaviours but being capable of identifying this influence in practice | |

| Attitudes | AT1 | Become aware of attitudes needed for higher levels of Intercultural Competence (such as acceptance of differences, openness, non-judgmental attitude, tolerance, a cooperative mindset, flexibility, valuing diversity and respect for culturally different others) |

| AT2 | Practise applying non-judgmental attitudes—not judging culturally different behaviour and non-judgmental attitudes in general | |

| AT3 | Develop openness to adjust behaviour in intercultural interactions | |

| Skills | S1 | Develop practical intercultural communication approaches |

| S2 | Develop an ability to mediate in an intercultural situation | |

| S3 | Practice verbalising cultural expectations and norms, discussing expectations and speaking about culturally different practices that are disturbing; ability to speak about cultural differences | |

| S4 | Identify the impact of cultural differences in misunderstandings | |

| S5 | Develop an ability to check how one’s behaviour is perceived in an intercultural context | |

| S6 | Develop an ability to adjust one’s behaviour in a culturally diverse context | |

| S7 | Improve the ability to shift between cultural environments | |

| S8 | Develop strategies for dealing with people with (perceived) lower IC | |

| Intercultural Teamwork | ITM1 | Develop skills for working with diverse teams |

| ITM2 | Increase understanding of leadership roles and strategies for intercultural teams | |

| ITM3 | Develop skills of mediation in intercultural teams | |

| Intercultural Conflict Management | ICM1 | Understand the impact of Intercultural Competence on conflicts |

| ICM2 | Be aware of strategies for identifying, analysing and solving intercultural conflicts | |

| ICM3 | Develop skills for effectively dealing with conflicts related to cultural differences | |

| Intercultural Relationship Building | ITM1 | Increase awareness of issues and challenges in intercultural relationship building |

| ITM2 | Develop a positive attitude to intercultural relationships | |

| ITM3 | Develop ability to form, develop and maintain intercultural relationships (private or work) | |

| ITM4 | Develop strategies for encouraging intercultural relationships in one’s environment (private or work) | |

| Emotional Intelligence | E1 | Gain knowledge about the concept of emotional intelligence and its use |

| E2 | Develop awareness of one’s own emotions | |

| E3 | Increase one’s ability to manage own emotions | |

| E4 | Improve one’s ability to notice and understand emotional perspectives of culturally different others through empathy | |

| E5 | Develop an ability to deal with emotions in teamwork and conflict situation | |

| Critical Reflection | CR1 | Develop the capacity to deal with stereotypes (they have themselves or others might have about their culture) |

| CR2 | Develop cognitive flexibility and/or ability to analyse intercultural encounters through a culturally aware perspective and seeing things from different cultural perspectives | |

| CR3 | Develop a critical approach to culture-specific knowledge | |

| CR4 | Increase critical awareness of one’s own assumptions and behaviour in an intercultural context | |

| CR5 | Increase critical awareness of others’ behaviours in an intercultural context | |

| Developing Intercultural Competence | DIC1 | Demonstrate understanding of learning strategies for developing Intercultural Competence |

| DIC2 | Increase understanding of one’s own learning and development approach to IC development | |

| DIC3 | Know how to identify logistic, specific and in-depth knowledge of individual cultures | |

| DIC4 | Develop an attitude of lifelong-learning in relation to Intercultural Competence development | |

| DIC5 | Develop awareness of one’s own level of Intercultural Competence in order to identify developmental needs | |

| DIC6 | Develop an ability to set objectives, plan actions and reflect on owns progress in Intercultural Competence development | |

| Intercultural Virtual Teamwork | IVT1 | Understand the main characteristis of virtual communication and the role it plays in a globalized workplace nowadays |

| IVT2 | Be aware of the impact that virtual communication has on intercultural virtual teamwork | |

| IVT3 | Have a positive attitude in relation to creating strategies to overcome barriers posed by virtual communication | |

| IVT4 | Put strategies to overcome barriers posed by virtual communication into practice when working in intercultural virtual teams |

References

- Doh, J.P.; Tashman, P. Half a world away: The integration and assimilation of corporate social responsibility, sustainability, and sustainable development in business school curricula. Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Manag. 2014, 21, 131–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Argento, D.; Einarson, D.; Mårtensson, L.; Persson, C.; Wendin, K.; Westergren, A. Integrating sustainability in higher education: A Swedish case. Int. J. Sustain. High. Educ. 2020, 21, 1131–1150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caniglia, G.; John, B.; Bellina, L.; Lang, D.J.; Wiek, A.; Cohmer, S.; Laubichler, M.D. The glocal curriculum: A model for transnational collaboration in higher education for sustainable development. J. Clean. Prod. 2018, 171, 368–376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caniglia, G.; John, B.; Kohler, M.; Bellina, L.; Wiek, A.; Rojas, C.; Laubichler, M.D.; Lang, D. An experience-based learning framework: Activities for the initial development of sustainability competencies. Int. J. Sustain. High. Educ. 2016, 17, 827–852. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caniglia, G.; Luederitz, C.; Groß, M.; Muhr, M.; John, B.; Keeler, L.W.; von Wehrden, H.; Laubichler, M.; Wiek, A.; Lang, D. Transnational collaboration for sustainability in higher education: Lessons from a systematic review. J. Clean. Prod. 2017, 168, 764–779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferrer-Balas, D.; Buckland, H.; de Mingo, M. Explorations on the University’s role in society for sustainable development through a systems transition approach. Case-study of the Technical University of Catalonia (UPC). J. Clean. Prod. 2009, 17, 1075–1085. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lambrechts, W.; Mulà, I.; Ceulemans, K.; Molderez, I.; Gaeremynck, V. The integration of competences for sustainable development in higher education: An analysis of bachelor programs in management. J. Clean. Prod. 2013, 48, 65–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Leal Filho, W.; Manolas, E.; Pace, P. The future we want: Key issues on sustainable development in higher education after Rio and the UN decade of education for sustainable development. Int. J. Sustain. High. Educ. 2015, 16, 112–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Lenkaitis, C.A. Integrating the United Nations’ Sustainable Development Goals: Developing content for virtual exchanges. Lang. Learn. Technol. 2022, 26, 1–20. [Google Scholar]

- O’Flaherty, J.; Liddy, M. The impact of development education and education for sustainable development interventions: A synthesis of the research. Environ. Educ. Res. 2018, 24, 1031–1049. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Kanbar, N. Can Education for Sustainable Development Address Challenges in the Arab Region? Examining Business Students’ attitudes and Competences on Education for Sustainable Development: A Case Study. Discourse Commun. Sustain. Educ. 2012, 3, 41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdelgaffar, H.A. A review of responsible management education: Practices, outcomes and challenges. J. Manag. Dev. 2021, 40, 613–638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Figueiró, P.S.; Raufflet, E. Sustainability in higher education: A systematic review with focus on management education. J. Clean. Prod. 2015, 106, 22–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- John, B.; Caniglia, G.; Bellina, L.; Lang, D.J.; Laubichler, M. The Glocal Curriculum: A Practical Guide to Teaching and Learning in an Interconnected World. 2017. Available online: https://www.uni-hamburg.de/ (accessed on 8 March 2022).

- Sierra, J. The potential of simulations for developing multiple learning outcomes: The student perspective. Int. J. Manag. Educ. 2020, 18, 100361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García-Feijoo, M.; Eizaguirre, A.; Rica-Aspiunza, A. Systematic review of sustainable-development-goal deployment in business schools. Sustainability 2020, 12, 440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Giudici, E.; Dettori, A.; Caboni, F. Challenges of humanistic management education in the digital era. In Virtuous Cycles in Humanistic Management; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2020; pp. 21–35. [Google Scholar]

- European University Association. Digital Transition. Available online: https://eua.eu/issues/31:digital-transition.html (accessed on 3 July 2022).

- Swanger, D. The Future of Higher Education in the US: Issues Facing Colleges and Their Impacts on Campus. 2018. Available online: http://hdl.handle.net/1951/70492 (accessed on 6 June 2022).

- Evolve. What Is Virtual Exchange? Available online: https://evolve-erasmus.eu/about-evolve/what-is-virtual-exchange/ (accessed on 3 July 2022).

- O’Dowd, R.; Lewis, T. Online Intercultural Exchange: Policy, Pedagogy, Practice; Routledge: Oxfordshire, UK, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Taras, V.; Caprar, D.V.; Rottig, D.; Sarala, R.M.; Zakaria, N.; Zhao, F.; Jiménez, A.; Wankel, C.; Lei, W.S.; Minor, M.S. A global classroom? Evaluating the effectiveness of global virtual collaboration as a teaching tool in management education. Acad. Manag. Learn. Educ. 2013, 12, 414–435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kurek, M. Designing tasks for complex virtual learning environments. Bellaterra J. Teach. Learn. Lang. Lit. 2015, 8, 13–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Commission; European Education and Culture Executive Agency; Velden, B.; Helm, F. Erasmus+ Virtual Exchange: Intercultural Learning Experiences: 2019 Impact Report, Publications Office. 2020. Available online: https://data.europa.eu/doi/10.2797/513584 (accessed on 6 June 2022).

- Guth, S.; Helm, F.; O’Dowd, R. University language classes collaborating online. In A Report on the Integration of Telecollaborative Networks in European Universities; 2012; Available online: https://www.unicollaboration.org/ (accessed on 8 March 2022).

- Guth, S.; Rubin, J. How to get started with COIL. In Globally Networked Teaching in the Humanities; Routledge: Oxfordshire, UK, 2015; pp. 40–57. [Google Scholar]

- O’Dowd, R. From telecollaboration to virtual exchange: State-of-the-art and the role of UNICollaboration in moving forward. Res. Publ. Net 2018, 1, 1–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferreira-Lopes, L.; Elexpuru-Albizuri, I.; Bezanilla, M.J. Developing business students’ intercultural competence through intercultural virtual collaboration: A task sequence implementation. J. Int. Educ. Bus. 2021, 14, 338–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bird, A.; Oddou, G.; Bond, M.H. Developing Intercultural Competency: With a Focus on Higher Education. Contemp. Cross-Cult. Manag. 2020, 2020, 498. [Google Scholar]

- Lozano, R.; Ceulemans, K.; Alonso-Almeida, M.; Huisingh, D.; Lozano, F.J.; Waas, T.; Lambrechts, W.; Lukman, R.; Hugé, J. A review of commitment and implementation of sustainable development in higher education: Results from a worldwide survey. J. Clean. Prod. 2015, 108, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pérez-Sánchez, M.; Díaz-Madroñero Boluda, F.M.; Mula, J.; Sanchis, R. The Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) Applied to Higher Education. A Project Based Learning Proposal Integrated with the SDGs in Bachelor Degrees at the Campus Alcoy (UPV). EDULEARN Proc. 2020, 2020, 3997–4005. [Google Scholar]

- Schnurr, M.A.; Taylor, A. Simulating the sustainable development goals: Scaffolding, social media and self-reported learning outcomes amongst entry-level students. J. Political Sci. Educ. 2021, 17, 255–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hueske, A.-K.; Pontoppidan, C.A.; Iosif-Lazar, L.-C. Sustainable development in higher education in Nordic countries: Exploring E-Learning mechanisms and SDG coverage in MOOCs. Int. J. Sustain. High. Educ. 2021, 23, 196–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- López, B. How Higher Education Promotes the Integration of Sustainable Development Goals—An Experience in the Postgraduate Curricula. Sustainability 2022, 14, 2271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crawford, J.; Cifuentes-Faura, J. Sustainability in higher education during the COVID-19 pandemic: A systematic review. Sustainability 2022, 14, 1879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Dowd, R. A transnational model of virtual exchange for global citizenship education. Lang. Teach. 2020, 53, 477–490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Dowd, R.; Waire, P. Critical issues in telecollaborative task design. Comput. Assist. Lang. Learn. 2009, 22, 173–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferreira-Lopes, L.; Bezanilla, M.J.; Elexpuru, I. Integrating Intercultural Competence development into the curriculum through Telecollaboration. A task sequence proposal for Higher Education. Rev. Educ. Distancia RED 2018, 18, 58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hofstede, G. Dimensionalizing cultures: The Hofstede model in context. Online Read. Psychol. Cult. 2011, 2, 1–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hall, E. Beyond Culture; Anchor Books: New York, NY, USA, 1976. [Google Scholar]

- Bird, A. Introduction: Experiencing the world. In The Palgrave Handbook of Experiential Learning in International Business; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2015; pp. 3–11. [Google Scholar]

- Leask, B. Internationalizing the curriculum and all students’ learning. Int. High. Educ. 2014, 78, 5–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Hauck, M. The enactment of task design in telecollaboration 2.0. Task-Based Lang. Learn. Teach. Technol. 2010, 2010, 197–217. [Google Scholar]

- Kurek, M.; Mueller-Hartmann, A. Task design for telecollaborative exchanges: In search of new criteria. System 2017, 64, 7–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Müller-Hartmann, A.; Schocker-von Ditfurth, M. Task-Based Language Teaching und Task-Supported Language Teaching; Hallet, W., Königs, F.G., Eds.; Handbuch Fremdsprachendidaktik: Stuttgart/Seelze, Germany, 2010; pp. 203–207. [Google Scholar]

- Vinagre, M. Developing teachers’ telecollaborative competences in online experiential learning. System 2017, 64, 34–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Storey, M.; Killian, S.; O’Regan, P. Responsible management education: Mapping the field in the context of the SDGs. Int. J. Manag. Educ. 2017, 15, 93–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferreira-Lopes, L.; Van Rompay-Bartels, I. Preparing future business professionals for a globalized workplace through intercultural virtual collaboration. Dev. Learn. Organ. Int. J. 2020, 34, 21–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Task | Type of Task | Description of Task |

|---|---|---|

| Task 1 | Information-exchange task (icebreaker) | Each group was invited to record a video locally introducing team members to the colleagues from the other location |

| Task 2 | Workplan based on the comparison of Hofstede’s National Culture Dimensions | Groups had to meet online, discuss their cultures’ differences and similarities according to Hofstede’s National Culture Dimensions and then prepare a workplan for the development of the business case (Task 3) |

| Task 3 | Business case analysis of how international companies of choice address SDG 12 in the countries represented by the group members | Groups had to analyse how two or more international companies from the same industry adapted their marketing strategies to address SDG 12 and to which extent they adapted such strategies to local cultures. Students had to connect the information found about the companies and SDGs with the content learned in face-to-face sessions. |

| Learning Outcome | Code |

|---|---|

| Explain how the companies selected approach sustainability | Sustainability |

| Explain how the companies selected adapt to the cultures represented in the group | Culture |

| Carry out a critical reflection about the intersection of culture x marketing x sustainability | Reflection |

| Group | Selected Companies’ Industry | Explain How the Companies Selected Approach Sustainability | Explain How the Companies Selected Adapt to the Cultures Represented in the Group | Carry Out a Critical Reflection about the Intersection of Culture x Marketing x Sustainability |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Group 1 | Coffee | √ | √ | |

| Group 2 | Fast-food | √ | √ | |

| Group 3 | Consumer staples | √ | √ | |

| Group 4 | Athletic apparel | √ | √ | |

| Group 5 | Skin and body care | √ | √ | |

| Group 6 | Fast-food | √ | √ | |

| Group 7 | Automotive | √ | √ | |

| Group 8 | Fast-food | √ | √ | |

| Group 9 | Fast-food | √ | √ | |

| Group 10 | Shaving razor | √ | √ | √ |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Ferreira-Lopes, L.; Van Rompay-Bartels, I.; Bezanilla, M.J.; Elexpuru-Albizuri, I. Integrating SDG 12 into Business Studies through Intercultural Virtual Collaboration. Sustainability 2022, 14, 9024. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14159024

Ferreira-Lopes L, Van Rompay-Bartels I, Bezanilla MJ, Elexpuru-Albizuri I. Integrating SDG 12 into Business Studies through Intercultural Virtual Collaboration. Sustainability. 2022; 14(15):9024. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14159024

Chicago/Turabian StyleFerreira-Lopes, Luana, Ingrid Van Rompay-Bartels, Maria José Bezanilla, and Iciar Elexpuru-Albizuri. 2022. "Integrating SDG 12 into Business Studies through Intercultural Virtual Collaboration" Sustainability 14, no. 15: 9024. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14159024

APA StyleFerreira-Lopes, L., Van Rompay-Bartels, I., Bezanilla, M. J., & Elexpuru-Albizuri, I. (2022). Integrating SDG 12 into Business Studies through Intercultural Virtual Collaboration. Sustainability, 14(15), 9024. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14159024