Abstract

The development approach to creating smart cities focused on data collection and processing relies on the construction of an efficient digital infrastructure and a safe trading environment under the protection of legal governance. Thus, studying the role and improvement of legal authority in the construction of smart cities is vital. This study first described the digital economy index of 31 provinces in China from 2014 to 2020, and analyzed the function of the legal governance in the development of local smart cities based on the promulgation and implementation of regulations on smart cities in the same period. The results indicate that perfect central legislation can provide a safe and stable environment for smart cities, and there is a positive correlation between the number of local norms and the development of digital economy. However, the limitation in legislation and its implementation causes legal gray areas, which hamper the development of smart cities. After conducting text analysis on multiple legal documents, we identified that the most critical issues are data security issue, data alienation issue, public data opening, and sharing issue. To this end, we examined the role that legal governance plays in the smart cities of New York and London in a case-comparison approach. Overall, we proposed future coping mechanisms for legal governance in smart city construction, such as promoting multi-subject participation in formulating legal norms, changing the model before legal regulation, and using local legal norms to determine the scope and quality of government data disclosure. This study further filled the gap in the study of China’s smart cities from the legal system of risk identification and control, which could help regulatory bodies, policymakers, and researchers to make better decisions to overcome the challenges for developing sustainable smart cities.

1. Introduction

In 2020, China’s digital economy maintained a vigorous development trend, with a scale of 39.2 trillion yuan, accounting for 38.6% of the gross domestic product (GDP). The growth rate of the digital economy was three times that of GDP (Data Sources: www.caict.ac.cn/kxyj/qwfb/bps/202104/P020210424737615413306.pdf, Beijing, China, accessed on 4 July 2022). As an important bearing space for digital economic activities, smart cities accelerate the quality and scale of urban digital economic development, which not only conforms to the development trend of economic servitization and service digitization but also promotes the healthy development of China’s digital economy [1]. Judging from the general trend of a new round of technological revolution and industrial transformation, data resources have become the fifth largest factor of production.

However, cities accommodate people, wealth and economic activities, and diverse social relationships occur between intimate or unfamiliar subjects [2]. The blessing of digital technology has accelerated the risk of individuals living in isolation. Considerable conflict is caused by the phenomenon of “strangers together”, and hence the emergence of universal values, principles, and rules emerged for regulating people’s behaviors [3,4,5,6]. The content of legal norms includes the code of conduct, balance of values, and accountability mechanisms, which are closely related to the conflicts in the transformation of smart cities and shape and guide the value goals and development directions of smart city development [7].

Regarding the construction and development of smart cities in China, there have been quite rich discussions among scholars in different disciplines. For example, in terms of the role of smart city development, some scholars noted that the digital transformation of cities has brought new opportunities for sustainable development models such as green economy, sharing economy, and intelligent manufacturing [8,9]. For public governance, smart cities would play an active role in improving the efficiency of government public services, the quality of life of citizens, inclusive governance, and protecting vulnerable groups [10,11,12]. Therefore, promoting the development of smart cities has been added to the public agenda [13,14,15,16,17]. In terms of the challenges faced by the development of smart city, some scholars pointed out that the smart transformation of cities faced complex needs of multi-level governance, such as lack of transparency, poor implementation of accountability mechanisms [18,19,20,21]. Other scholars noted that the goal of smart city governance must include the vision of sustainable development of the eco-city and ensure that the natural and human environments are upgraded at the same time and improve the quality of life of citizens [22,23]. In terms of the driving factors for the development of smart cities, scholars noted that cities are an efficient data market, and the agglomeration effect of cities in economic and social aspects can be realized through the release of data elements [24,25,26]. The digital transformation of cities required the maximum use of data element resources, to construct an environment-friendly digital economic development model, through the implementation of urban governance activities in a refined and intensive governance manner to achieve sustainable urban development [27,28,29]. Integration of data resources is the core content of smart city construction. Therefore, it is necessary to improve the level of opening and sharing of public data, the capabilities of digital government construction and public data governance [30,31,32].

A review of the extant literature reveals that while legal interest is growing, at least most academic responses continue to come from the fields of technology, urban studies, environment, and sociology rather than law, which have primarily emphasized the social, urban, policing, and environmental benefits of smart cities rather than their challenges. There was also a lack of research on the relationship between the development of smart cities in China and legal norms from the perspective of data science. Certain hidden dangers were behind the above theory and practice. The situation of building smart cities is relatively optimistic, with more constructive research and practice, and less research and practice on risk control. The understanding of the city remains in the comprehensive system structure, trying to create a very grand blueprint of the smart city, but it does not consider the auxiliary and supportive institutions enough. Risk control and the construction of auxiliary and supportive legal systems should also be the core topics of smart city research, otherwise, the development of smart cities will suffer from the lack of early warning and remedial mechanisms [33,34,35].

Therefore, it is necessary to systematically examine the dynamic process of smart cities’ legal governance. We should reconsider the design of smart city governance processes from a legal perspective [36,37]. This study’s main contents included the role of legal governance in the development of smart cities, existing problems, and improvement paths. We first used the principal component analysis method to describe the development of China’s smart cities, and combined the central legislation and local norms manually sorted out. Then we used the spatiotemporal analysis method to organically link them. Second, we used the desk research method, which compared the system design and practice of the legal governance in smart cities. After conducting on multiple legal documents, we identified that the most critical issues are data security issues, data alienation issues, public data opening and sharing issues. To address these issues, we selected London and New York, the world’s leading smart cities, to explore their advanced governance experience in addressing data processing activities, personal privacy protection, and national security goals. Finally, we proposed future coping mechanisms for legal governance in smart city construction.

The innovations of this study mainly include (1) at the scientific level, by constructing a digital economy index and analyzing its temporal and spatial evolution, the development of China’s smart cities is divided into comprehensive leading, characteristic development, and potential improvement types. Combining with the relevant data on the construction status of smart city legal governance in China, we put forward specific suggestions for the improvement of the legal governance of smart cities in different models. This study further filled the gap in the study of China’s smart cities from the legal system of risk identification and control. (2) At the social level, we used the case analysis method to learn from the legal governance experience of advanced cities in response to the key problems in the development of smart cities in China, such as data alienation, data insecurity, and insufficient openness of government public data. We put forward specific suggestions for improvement, including promoting multi-subject participation in formulating legal norms, changing the model before legal regulation, and using local legal norms to determine the scope and quality of government data disclosure, which could help regulatory bodies, policymakers, and researchers to make better decisions to overcome the challenges for developing sustainable smart cities.

2. Methodology

2.1. Using Principal Component Analysis to Describe the Development of Digital Economy in Chinese Cities

The development of smart cities is closely related to digital economy. At present, Chinese officials have not released data on the development of the city’s digital economy. Therefore, in this study, we referred to the digital economy measurement idea proposed by Liu et al. and used the principal component analysis [38]. We collected and utilized the public data from the China Statistical Yearbook and the National Bureau of Statistics, then divided the digital economy index into three dimensions—informatization development, internet development, and digital transaction development—in order to reflect the development status of the digital economy in each province as much as possible. First, the development of informatization guides the industry to transform to digital and promotes the digital transformation of the economy, which is the cornerstone of the development of the digital economy. Second, the Internet is an important platform and carrier for the development of the digital economy. It could play the role of information matching, supply and demand matching, constraints of time and space breaking. It also blurs the boundaries between virtual and real, which greatly enriches the connotation of the digital economy. Finally, considering that the essence of digital economic activity is that goods and services are traded in digital form, we choose digital transaction indicators. The emergence of digital transactions, on the one hand, has broken the traditional concept of time and space, and the supply and demand sides of products could transcend the limitations of time and space. On the other hand, digital transactions have enriched the types of transactions and accelerated the speed of transactions.

2.2. Using Desk Research to Find Problems in the Legal Governance of Smart Cities in China

Desk research mainly refers to the collection, arrangement, and analysis of zero-hour literature, primary literature, and secondary literature. The research reviewed includes academic papers, books, investigative reports, laws and regulations, and other documents. In the research process of this article, we mainly used Chinese and English databases such as Web of Science, CNKI, etc., to search the international and domestic literature on China’s smart cities, and inputed the data of smart cities and smart cities respectively. We used PKULAW.CN, government information disclosure websites, etc., to search for laws and regulations related to smart cities to obtain relevant information about China’s smart city legislation. We collected, organized, and analyzed key content related to the rule of law in the digital transformation of smart cities. It has formed a clear and comprehensive understanding of the current governance dilemma of China’s smart city development and construction.

2.3. Using International Case Studies to Provide Lessons for China

We used New York and London as the subjects of the case study because they were relatively recognized international metropolises by the international community. According to the 2021 Global City Index Report (Global City Index) released by Kearney Management Consulting, New York and London are the top two comprehensive cities globally [39]. In contrast, by understanding the intelligent transformation process of the two cities, it was found that they have better played the role of law in data governance. Therefore, we referred to the legal response strategies of London and New York on issues such as data alienation, personal privacy protection, national network security protection, government affairs and public data opening, and provided solutions for Chinese smart cities to deal with such problems.

3. Functions of Legal Governance in Smart Cities’ Construction

3.1. The Constraction of Digital Economy Index

3.1.1. The Computation of the Digital Economy Index

As shown in Table 1, we used the multi-objective linear weighting function method to weigh the indicators according to the following methods and steps, and to obtain the comprehensive index of each region and the index of each criterion level. Then we described the digital economy index of each province.

Table 1.

Sub-indicators composition of digital economy index.

The specific analysis process was as follows:

First, we defined as a proxy variable for the sub-indicator constructed for the digitized index. We determined the sub-indicator weights and calculated the proportion of the indicator in the region, where was the number of regions:

We calculated the entropy value of the index:

We calculated the coefficient of difference of the indicator:

We calculated the weight of the indicator

Second, the multi-objective linear weighting function method was used for the calculation of the comprehensive index. We calculated the indicator score of the criterion layer in the region, and was the total number of indicators included in the indicator:

We calculated the digital economic index of region , where n is the number of index layers:

The data related to local laws and regulations in this article were obtained by browsing and sorting through information provided on government websites.

3.1.2. Smart City Construction and Development Status in China

We described the digital economy development index of Chinese cities from 2013 to 2020 based on the principal component analysis to represent the digital transformation of the city. During the observation period, the digital economy index of China’s provinces basically showed an overall upward trend, which depends on the results of the country’s overall social and economic development. Since the outbreak of COVID-19, the “contactless” economic development model brought by the digital economy can better meet the needs of economic development in the post-pandemic era.

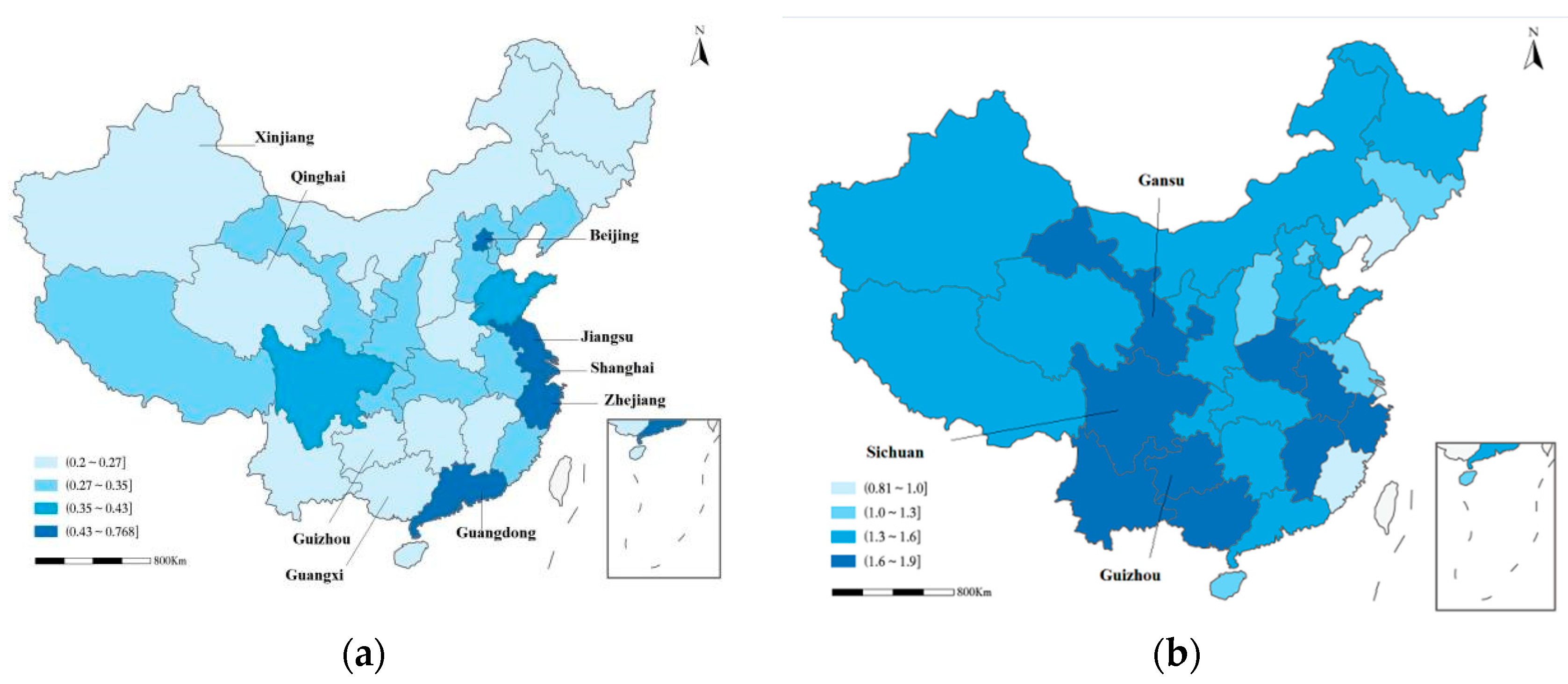

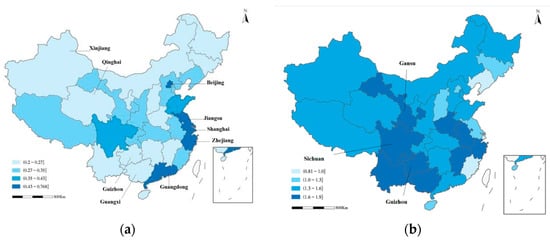

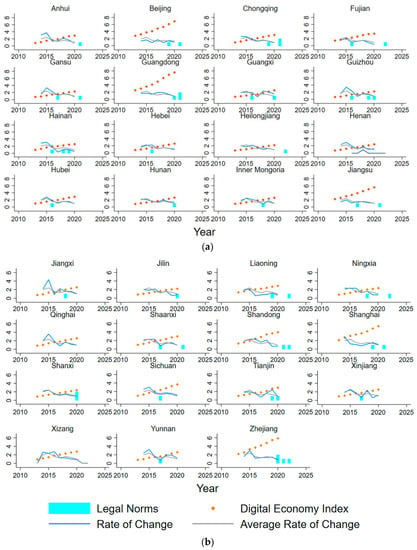

Figure 1a shows the digital economy index of each province in 2020. We can see that the development of the digital economy shows that the development level of the southeast region is higher than that of the northwest region. Among them, Beijing, Shanghai, Jiangsu, Zhejiang, and Guangzhou are basically in the first echelon, while the digital economy development level of provinces such as Xinjiang and Qinghai in the northwest, and Guangxi and Guizhou in the southwest are relatively backward. This is related to the overall socio-economic development of the province over a long period. However, from Figure 1b, which shows the development speed of digital economy in various provinces from 2014 to 2020, we can see that Sichuan, Gansu, Guizhou, and other provinces have the fastest growth rate of digital economy. It is closely related to the legalized business environment created by local regulations.

Figure 1.

Temporal evolution maps of the digital economy index of the 31 provinces in China (a) 2020, (b) 2014–2020 variation trends.

3.2. Legislative Status of Smart Cities in China

3.2.1. Central Legislative Level

Since the first year of China’s mobile Internet in 2013, the digital economy index of Chinese cities has grown rapidly. The basic framework for a national level Internet rule of law has been formed. In the field of cybersecurity, laws and regulations such as the Cybersecurity Law, the Data Security Law, and the Anti-Terrorism Law were promulgated, clarifying the basic requirements for cybersecurity management. In the field of data governance, the Civil Code, which provides principles for the protection of data and network virtual property and systematically establishes a personal information protection system, has been published.

In terms of administrative and government regulations, the government has continuously issued legislative policies to regulate and promote the healthy and sustainable development of smart city construction. Such policies covered technology, information, economy and other fields. In 2014, the central government issued the “Guiding Opinions on Promoting the Healthy Development of Smart Cities”, the general requirement of which was to focus on building a new urbanization road which is intensive, intelligent, green and low-carbon. The release of this document indicates the deployment of China’s overall smart city development policy setting a clear direction. The specific regulations are shown in Table 2.

Table 2.

The current state of policies related to the construction of smart cities issued by the central government.

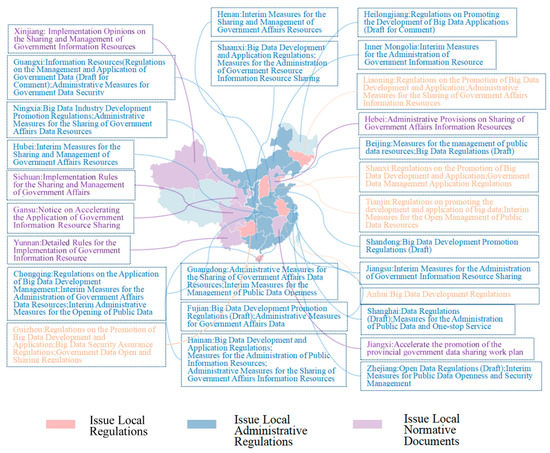

3.2.2. Local Legislative Level

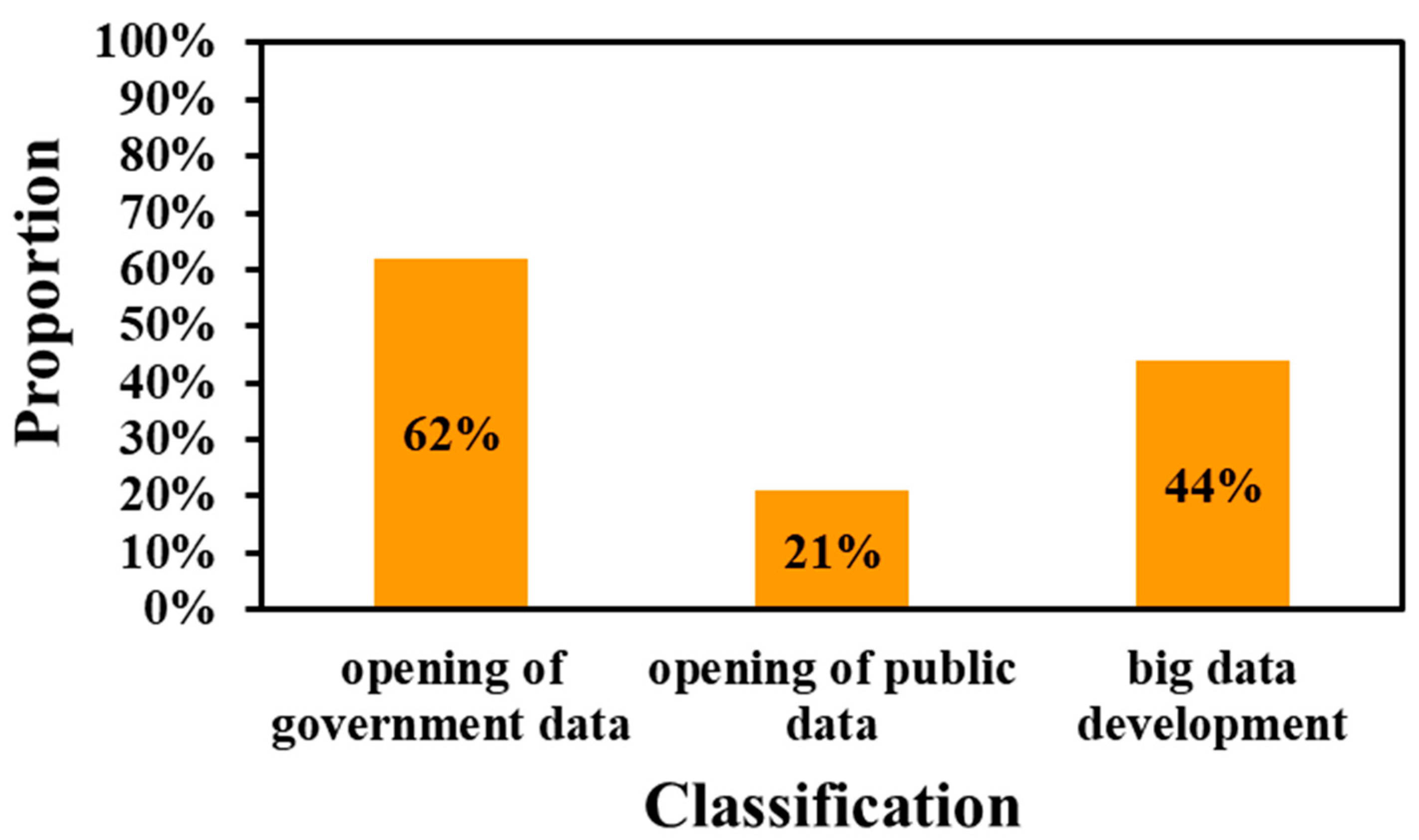

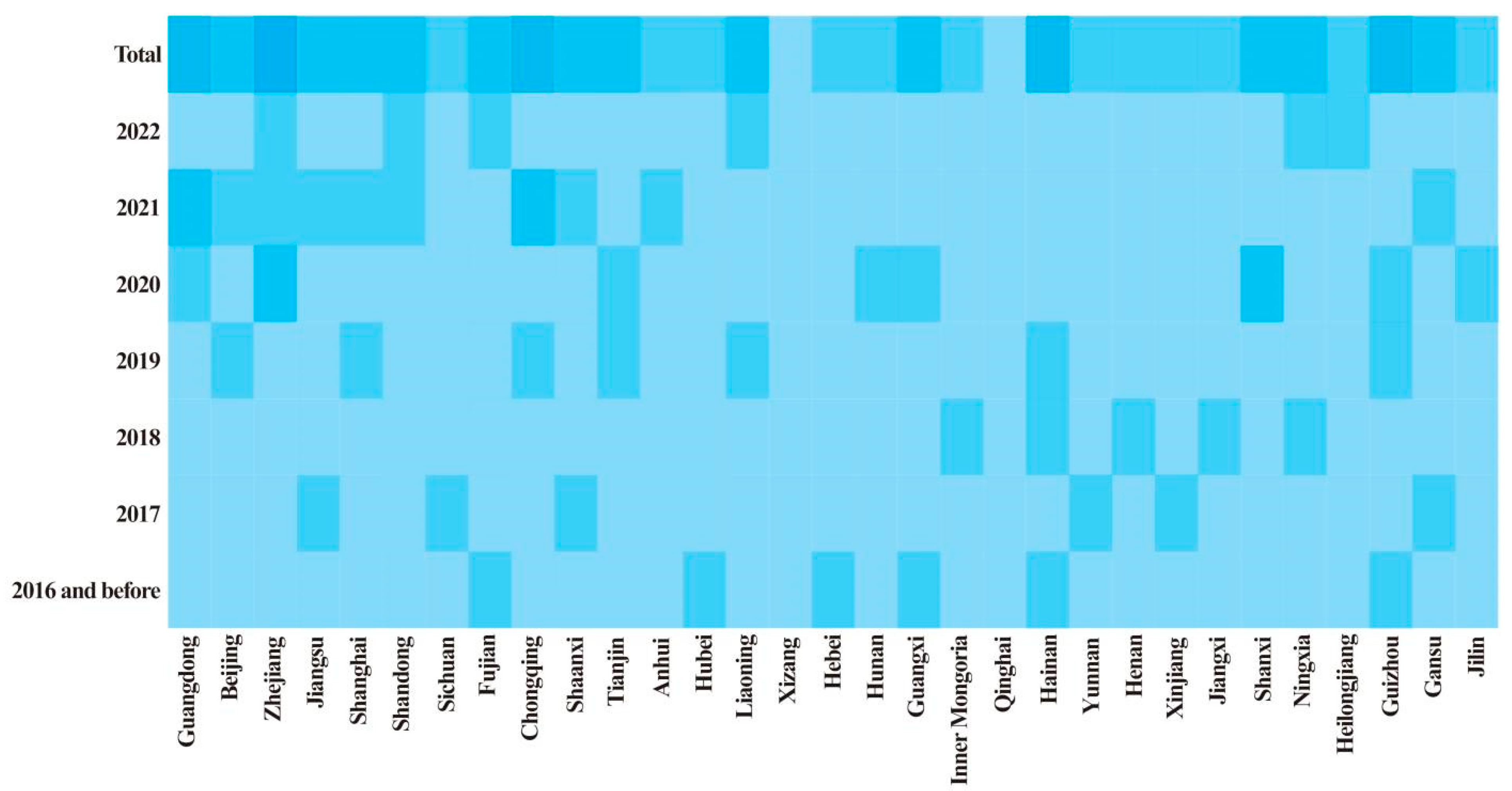

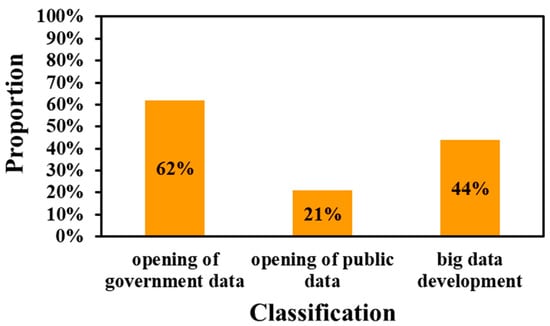

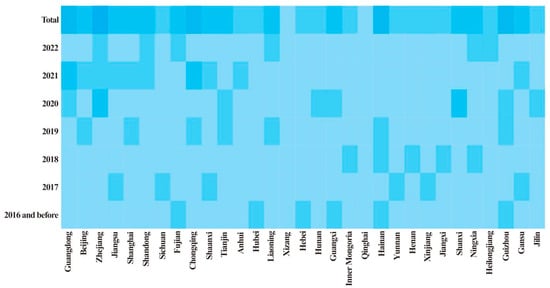

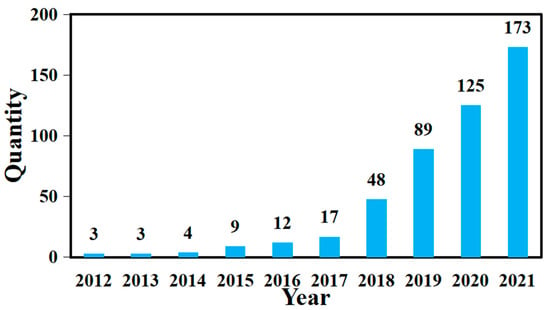

The number and timing of local legal regulations promulgated by provinces and cities are shown in Figure 2. Most of these were adopted in 2016 and later. More than 10 and 12 regulations were promulgated in 2020 and 2021, respectively. As shown in Figure 3, the existing provincial-level normative documents mainly focus on the following three areas: opening of government data, opening of public data, and big data development. A total of 21 provinces, autonomous regions, and municipalities directly under the central government have formulated local normative documents to promote the opening of government affairs information, while seven have formulated local normative documents to promote the opening of public data. Finally, 15 have formulated local normative documents for comprehensive big data development to regulate data processing, data security and other issues within their zoning areas. Such documents include local regulations, local government regulations, and other normative documents. Figure 4 reflects the digital economy scores of major Chinese cities during 2017–2021.

Figure 2.

Proportion of provinces that have formulated local norms in terms of government affairs openness, public data openness, and big data development.

Figure 3.

Diagram showing the number of smart city-related legal norms in each province since 2016 (the colors in the figure from dark to light represent the city’s annual smart city-related local legal norms 4, 3, 2, 1, and 0, respectively).

Figure 4.

(a,b) The provincial digital economy index, the ratio of growth rate to average speed, and the introduction of local regulations in each province since 2013 (due to unavailability, data from Hong Kong, Macau, and Taiwan Province of China are not shown in this figure).

Efficient legal governance could provide a safe and reliable trading environment for smart city construction and economic development. Figure 3 shows the number of smart city-related legal norms in each province since 2016. There is little difference in the number of designated smart city-related regulations among cities, with most of them remaining at two or three. Cities that have formulated more than three digital-related local regulations have developed a digital economy significantly faster than others in recent years. For example, Guizhou has grown by 171% since 2013. Hainan, as a free trade port, has also developed rapidly in recent years. Chongqing is a municipality directly under the Central Government in western China. The development of the digital economy has consolidated its dominant position.

3.3. The Relationship between Legal Governance and Smart City Development

3.3.1. Central Legislation Provides Top-Level Design Guidelines for Smart City Development

The development of a smart city involves various entities such as the government, enterprises, and residents, and requires considerable investment in capital, technology, and human resources. Therefore, it requires clear planning and top-level design. At present, most such plans are provided by construction market players through bidding, which often lack sufficient attention to and understanding of actual local needs and major challenges [40]. The goal of a smart city construction is often unclear, policymakers have a biased understanding of smart cities, and lack information governance capabilities. It also makes the initiative not only lacking in purpose, but also unable to form connections between cities. The top-level planning and objectives are not clear, making it difficult to effectively and fully utilize the information resources invested in the smart city subsystem [41]. For example, a large number of information infrastructure in transportation, energy, education or medical care cannot be interconnected, making it difficult to achieve the construction goals of smart cities, and for people to derive health or economic benefits from such an enterprise [42].

Solving these problems should consider factors such as politics, law, science and technology, and so on. Among these factors, the law plays a very important role, which is directly related to the social investment conditions at the city level and the business environment. The top-level design of the legal governance of smart cities occupies the core position, which will ensure the development, utilization, sharing, and protection of information resources in a standardized form. The top-level design of smart city legal governance mainly includes the necessity of top-level design, basic principles, planning methods, coordination, and regularity of the legal system, among others.

3.3.2. Local Legislation Provides Solutions Tailored to Local Conditions for the Construction of Characteristic Smart Cities

Local legal norms have the characteristics of law of subordination, locality, and experimentation. From the perspective of nature, the formulation of local legal norms cannot conflict with the constitution, laws, and administrative regulations, and cannot make provisions that form the exclusive legislative prerogative of the National People’s Congress and its Standing Committee. Locality emphasizes the actual needs of the relevant administrative unit, the scope and effects limited to the local affairs within the administrative region. From the perspective of experimentation and pioneering, local legislation accumulated experience and filled the gaps for unified national legislation.

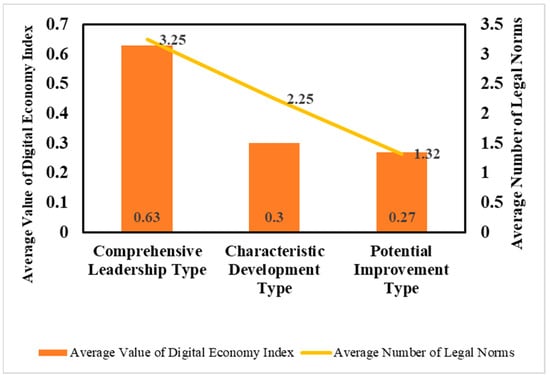

Figure 4 reflects the provincial digital economy index, the ratio of growth rate to average speed, and the introduction of local regulations in each province since 2013. We divided different provinces into comprehensive leading type, characteristic development type, and potential improvement type: (1) the comprehensive leading type refers to the super competitiveness of the digital economy, which has outstanding performance in terms of digital innovation elements, digital infrastructure, core digital industries, digital integration applications, digital economy needs, and digital policy environment. Beijing, Shanghai, Zhejiang, Jiangsu, and Guangzhou belong to this category, with an average digital economy index of 0.63 and an average of 3.25 local regulations related to smart cities. (2) The characteristic development type refers to the strong competitiveness of the digital economy, its comparative advantages have their own characteristics, and they play an important role in the development of China’s digital economy. The characteristic development type include Sichuan represented by industrial clusters, Chongqing represented by industrial digitization, Tianjin represented by location synergy, and Guizhou represented by laws and regulations. The average digital economy index of each province under this model is 0.3, and the average number of local regulations related to smart cities issued is 2.25. (3) The potential improvement type refers to all other provinces, which should actively look for their own location and comparative advantages. Under this model, the average digital economy index of each province is 0.27, and the average number of local regulations related to smart cities promulgated is 1.32. As shown in Figure 5, we found that, on the whole, the higher the level of digital economy development, the greater the number of local regulations related to smart cities in the region, and there was a positive correlation between them.

Figure 5.

Average scores of the digital economy index and numbers of legal norms in different types.

Provinces more advanced in the development of the digital economy have developed more frequent data element transactions. Therefore, regulations should pay more attention to personal privacy protection and data security. Additionally, provinces with relatively backward digital economy development should pay more attention to digital infrastructure construction. The regulations at the central level should focus on the construction of inclusive digital infrastructure, and more resources should be inclined to areas with relatively lagging development to avoid the emergence of the digital divide. Characteristic development and potential improvement provinces can use local regulations to create a policy environment conducive to the development of the digital economy by formulating local tax incentives and other measures.

Taking the Guizhou Province as an example, in particular, since 2016, the growth rate and magnitude of the digital economy have been significantly higher than the national average. The reason is that Guizhou, as the first national big data comprehensive pilot area, is also the first province in China to legislate on big data at the provincial level. Promotion regulations and legislation defined the relationships between all aspects of big data and comprehensively executed the practice of big data security governance. Among them, the “Regulations on the Promotion of Big Data Development and Application in the Guizhou Province” is the first normative act on big data in the country, which has been implemented since 1 March 2016. The regulation closely followed the actual needs and trends of big data development and application in the Guizhou Province and provided effective guidance for digital economic activities within its administrative region. The general and guiding provisions established Guizhou Province’s innovative practices in the fields of big data development, benefited the people offer preferential government in the form of local regulations, and ensured the development of the big data industry stays on track with the rule of law. The successful operation of the “Guizhou on the Cloud” project verifies the superiority of the local data policy environment in Guizhou.

4. Key Issues Facing the Legal Governance of Smart Cities in China

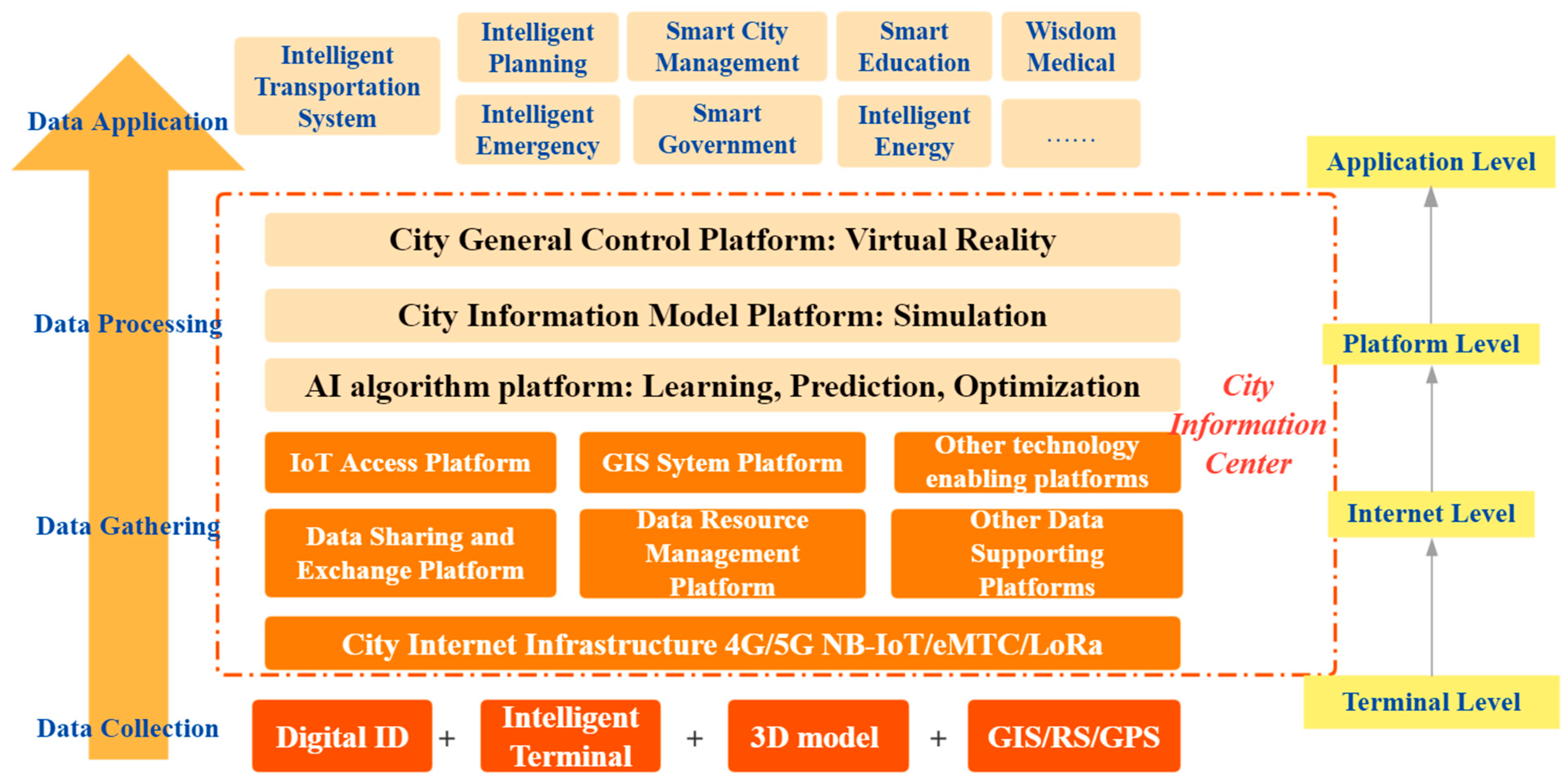

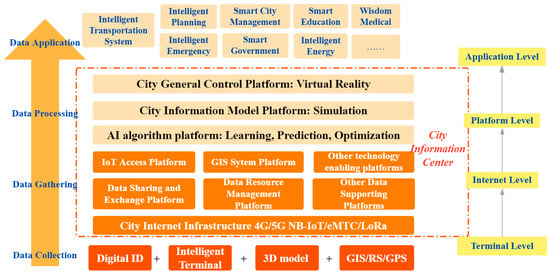

4.1. Smart City Infrastructure Operation Framework and Key Points of Governance

Data are the lifeblood of a smart city, and its availability, usage, cost, quality, analytics, and associated business models and management are areas of interest for all actors in the city [43,44]. The urban infrastructure construction process within the process of digital transformation is shown in Figure 6. It is not difficult to see that data elements and different levels of the main layer run through the entire process of smart city infrastructure construction and operation, thus becoming the key point of smart city governance. While the importance of data to smart cities is undeniable, legal governance still faces challenges on key smart city issues. The three data-related issues discussed below are in a legal grey area. It belongs to the problems that the rules have not yet brought into the scope of adjustment, or the contradictions caused by the differences between the rules themselves and their implementation. This is closely related to the legal norms inconsistency and hysteresis.

Figure 6.

City data resource development application process.

4.2. Key Issues Facing the Legal Governance of Smart Cities in China

4.2.1. Data Alienation and Regulation Issues

As a bridge for people to understand the world, data needs to be able to facilitate communication and cognition when the subject of knowledge satisfied the autonomy and the authenticity of the information itself. Data alienation refers to the phenomenon where a person creates data to serve themselves, but data appear to be separated from, confronted with, or even replacing the person [45]. Data alienation mainly occurs in the business field. For example, big data and algorithm technology select to push information customized by platforms to users. However, the existence of the “safe harbor rule” confirms that the platform does not have the obligation to review the authenticity of the information uploaded by its users in advance, and it only undertakes necessary actions when prompted that there is a risk of infringement. It leads to the risk of users being exposed to distorted information. When users use the distorted information to carry out social activities, errors are inevitable. Data alienation isolates the information subject, human beings, causing them to lose their dominant position in information activities. New information asymmetries and risks have risen since the online platform scale of the digital transformation. The problems of data alienation and discipline require prior regulation of information technologies such as big data and algorithms. It has been difficult to adapt the existing legal governance framework based on private rights remedies and ex-post remedies to adapt to reflect, balance, and protect the interests of all parties in the process of urban digital transformation.

The reasons for the emergence and development of data alienation lie in the lack of effective supervision over the development of information technologies, such as big data and algorithms, as well as insufficient or underdeveloped regulatory systems for “technical power holders”. For example, digital public platforms are allowed to utilize vast amounts of user information in the process of market economy development through the data generated by user searches and browsing records, which is then anonymized and compiled into a pre-set user classification group to more accurately deliver product information, generate transactions and gain profits. In this information collection and processing, the “subjectivity” of the user as a person is diluted, and there also is a possibility of being guided by the platform [46]. Although there is no value tendency in the development of technology because it is used by different subjects, there must be a certain value tendency in the application process. The sustainable development of cities requires, on the one hand, to focus on the negative impact of data alienation on consumers and other users in economic activities, and on the other hand, to avoid excessive reliance on data to maintain order in urban public governance activities. Such reliance may lead to the marginalization of the main body of urban governance, the risk of governance objects, and the complexity of the governance environment. The excessive dependence of urban governance on data technology can form a data-dependent path that will alienate data technology into data discipline and make the city serve people [47]. The role of the city administration is transformed, becoming that of a controller, which violates the subjectivity of city governance.

4.2.2. Data Security Issues

Cities are the gathering centers of economic and social activities. Production, exchange, distribution, and consumption are part of economic development, produce a large amount of data that has economic and social value, including consumers’ personal information. Examples include financial data generated by investment and financing activities and urban traffic data generated based on urban geographic information. However, growing opposition in the privacy and surveillance industries has warned that smart cities pose a potential threat to personal privacy [48]. The Detection and Analysis Report on the Illegal Collection and Use of Personal Information by APPs’ issued by the National Computer Network Emergency Technology Processing Center of China and the China Network Security Association in 2021 shows that since May 2021, the Cyberspace Administration of China has 351 apps in 12 categories, of which 257 have problems related to “violating the principle of necessity and collecting personal information irrelevant to the services they provide”, mainly in online lending, online live broadcast, and security management apps [49]. At present, China has entered the stage of strong supervision of data legal compliance. Facing increasingly strict compliance requirements and new security threats in digital scenarios, the current sustainable development of smart cities primarily faces the following prominent data security issues: the first is the excessive collection and use of personal information by some application programming interfaces (APIs). Such a large accumulation of unnecessarily gathered, personal information increases the risk of data abuse and brings about compliance problems, such as unauthorized access and data misuse. In addition, new attacks threaten APIs. As the communication interface between applications and data services, APIs has been used in a wide range of scenarios and have become the key supply object for criminals to steal data from. Third is the issue of data security. It is difficult to maintain a prolonged state of data security, while diverse application digital transformation and data consumption scenarios are becoming increasingly more complex and the current management specifications and technologies do not completely match, resulting in an unsustainable state of data security. Smart city governance should inevitably consider the practical needs for data, algorithm, and integrated technology governance [50]. From a regulatory perspective, incorporating digital technology into the regulatory track and strengthening the security construction of digital urban infrastructure will enable regulators to effectively deal with data distortion and apply data leakage countermeasures.

4.2.3. Government Data and Public Data Openness and Sharing Issues

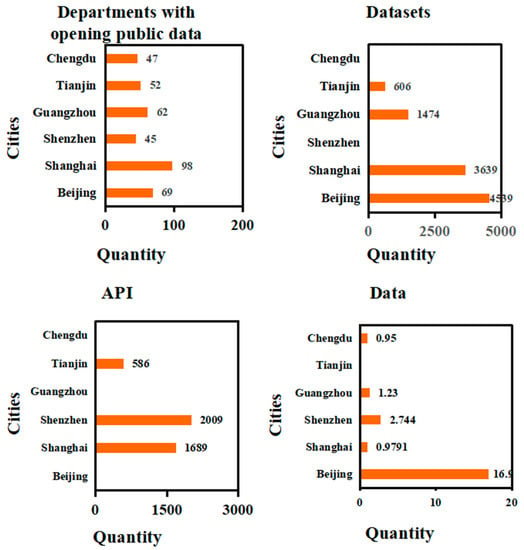

According to the China Open Data Index Report (Cities), as of October 2021, 193 provincial and city local governments in China had launched open data platforms, accounting for the majority of municipalities and deputy half of the provincial and prefecture-level administrative regions. The remaining cities have not yet opened online data platforms, as shown in Figure 7 [51].

Figure 7.

Number of open urban government data platforms.

The core of smart city governance lies in recognizing and handling the rights and obligations of the government in information protection and data utilization. Open government data and public data, innovation and development of the data industry, and security assurance are important tasks for the development of smart city big data. In the process of smart city construction in China, the consistency of public data and the spatial basis of different smart projects in the same city cannot be guaranteed. The sharing and integration of different intelligent systems or data cannot be achieved in smart cities [52]. In terms of public data openness, although the construction of smart cities is mainly based in metropolitan areas, cross-level and cross-departmental data sharing mechanisms have not been fully formed [53]. It is about sorting out the content of the central and local legislative norms on smart cities. Due to the diversity and complexity of the bodies issuing regulations, there is a lack of a unified leading agency. In the process of opening government affairs data, it is inevitable to face the problem of difficulty in data circulation between provinces, between government departments at the same level, and between the central and local governments, especially the problem that it is difficult for local governments to obtain data at the central level. Government departments often become information islands, some of which are caused by vertical management. It is difficult for the upper-level data to flow back. In other words, the data of the national ministries and commissions cannot be returned to the provinces and cities. Cross-province and city data sharing and business interconnection remain difficult, and local government data management faces the problem of vertical fragmentation. In addition, due to the lack of a unified and open data carrier platform, various provinces have inconsistent data open rules and statistical calibers platform. According to the ‘Government Data Sharing and Open Security Report‘ released by the China Academy of Information and Communications Technology, Beijing and Shanghai (which are leading national government data openness work) as well as Guangzhou, Shenzhen, Chengdu, and other cities are still in the initial stage in terms of creating open government departments and achieving the desired data quantity and quality, as shown in Figure 8 [54].

Figure 8.

Public data opening in typical cities (owning to unavailability of data in the figure could be collected).

5. Extraterritorial Experience of Smart City Legal Governance

London and New York occupy the leading positions in all aspects of global smart city construction [55], from the development of relevant laws and regulations to the integration of resources, risk prevention and control, and protection of personal information. Their example can be used as a reference for the construction of smart cities in China [56,57]. To cope with volatility and policy uncertainty in the governance of new technologies for smart cities and to maintain the stability of the governance structure, we can flexibly combine measures which have worked well in other countries and modify them according to the local conditions, thereby adapting to the changing environment [44].

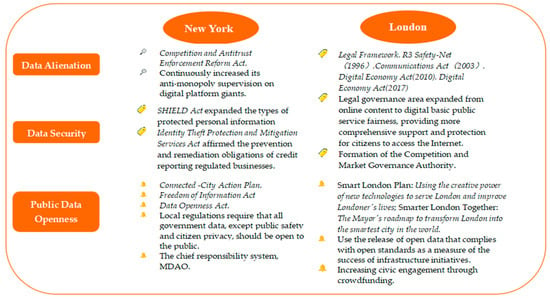

5.1. New York: Coordination of Data Openness and Data Security with Local Regulations

In the process of urban digital construction and governance, New York has been more focused on the role of the local legislation in mobilizing decentralized government departments, civil society, and market economic entities. All data held by the New York City government and its affiliates, other than public safety and citizens’ privacy data are mandated to be open and available to the public; the procedures for public access to these data are simplified and do not require registration or approval from the competent authority. In addition, the use of data is limited [58,59]. There are no restrictions in terms of public data disclosure and platform construction held by the government due to the Freedom of Information Law (FOIL) and Decree No. 11 on Data Disclosure (NYC Local Law of 2012). The aforementioned local legal norms stipulate that citizens and enterprises can submit data opening requests to more than 50 city government departments and public service agencies in New York City through the portal provided by the government data disclosure platform, according to their own personal and economic development needs [60]. New York’s local legal norms confirm effective government reforms in an institutional normative manner and incorporates the Mayor’s Office of Data Analytics (MODA), that plays a key role in digital construction as part of the New York City Charter, reporting directly to New York City. The mayor announced that directly analyzing the data of the government and its branches enables the city to bridge data gaps and identify the risk extent of urban governance, which, in turn, can effectively improve the quality and level of public services and enhance government transparency. In terms of addressing the risks posed by smart cities, New York City passed in 2019 the Stop Hacking and Improve Electronic Data Security Act (SHIELD ACT) to expand the types of personal information that are protected. At the same time, the Identity Theft Protection and Mitigation Services Act confirmed that regulated credit reporting businesses provide their consumers identity theft prevention and remediation services for up to five years. New York’s local regulations unify the forces between different governments and their branches as an essential step for smart city governance, bridge the gaps in smart governance in all sectors of society, and initially establish a city-based social operation, including traffic, crime, and health [61]. The smart city ecosystem includes data from various fields, e.g., emergency and encourages multiple subjects to deeply mine the value of data on the basis of the government public data. It simultaneously confirms the need to protect personal privacy protection through relevant legislative acts and gives consideration to public security and national security, while promoting smart, sustainable, and high-quality urban development.

In the later stage of the smart city construction, legislation at the national level in the United States has been gradually added. The United States released the National Smart City Action Strategy in September 2015 and planned to invest USD 160 million in research to strengthen the supply of urban services, combat climate change, improve transportation, and stimulate economic recovery. However, in terms of personal privacy and protection, the United States has not yet formed a unified national data privacy and protection act.

5.2. London: A Smart City Digital Governance Framework Constructed by Central and Local Legal Norms

In terms of data alienation and data security maintenance brought about by data alienation, London mainly relies on effective central legislation to establish a regulatory framework for platforms that have data power and have greater development risks. In addressing the problem of data alienation caused mainly by platforms that hold data power, the United Kingdom has established a regulatory framework for digital content and infrastructure governance through bills such as the “R3 Safety-Net (1996)”, the “Communications Act (2003)”, and the “Digital Economy Act (2010, 2017)”. The focus has expanded from online content to basic digital public service fairness, providing more comprehensive support and protection for Internet users. In 2012, the United Kingdom (UK) established the Competition and Market Governance Authority, who is also responsible with regulating the abuse of market position by digital platforms, to promote fair competition in the digital economy and protecting the legitimate rights and interests of domestic small and medium-sized enterprises.

In 2021, the bureau set up a new digital market department, which will cooperate with the existing Communications Authority to regulate content services, data use, privacy protection and company mergers. At the same time, on the basis of protecting the domestic market and social security, the UK has released a series of digital economy strategies such as the “UK national data strategy”. The goal is to promote in-depth cooperation between the public and private sectors and the third sector, establish a data governance framework that contributes to economic prosperity and technological innovation, and seek initiative in balance.

On the issue of data openness, London used local legislation to guide data openness within its jurisdiction and launched its first smart city plan in March 2013: “Smart London Plan: Using the creative power of new technologies to serve London and improve Londoner‘s lives” which aimed to promote the integration of systems and strengthen the links between systems through the application of digital technology so that the city could operate more efficiently and provide better services to residents and tourists [62]. This plan also put forward seven implementation paths and corresponding evaluation criteria, namely: citizen-centric, open data, making full use of London’s research, technology and innovation talents, optimizing London’s innovation ecosystem through the network, letting London grow in adaptation, city government to better serve Londoners, and a smarter London for all. The second smart city plan was released in June 2018, entitled “Smarter London Together: The Mayor’s roadmap to transform London into the smartest city in the world”. The plan explicitly focused the London Smart City desiderate on creating more user-designed services, leveraging city data, ensuring world-class connectivity and smarter streets, strengthening digital leadership and skills, and strengthening connections with the rest of the world.

Legislation shapes smart London in the following ways: first, in the formulation of legal norms, non-governmental social forces are mobilized in the smart city construction. The opinions of stakeholders are fully considered in devising the development plans, and the indicators set forth are regularly evaluated and published. Prior to planning, city officials in London spend six months extensively soliciting the needs and opinions on smart city construction of technical experts, public service agencies, and residents. In addition, a crowdfunding platform is employed to create a community patterns of co-construction, co-governance and sharing [63]. The city government is committed to directly raising funds from residents for urban livelihood projects. Successfully supported projects include Mini-Holland, which developed a slow-moving transportation system, and the creation of a “maker” space in the Herne Hill community. Such crowdfunding projects not only access new sources of investment but also motivate individuals and various organizations to improve the community environment and actively participate in community building [64]. In terms of the legal norms content, the city (1) implements a digital inclusion strategy that focuses on improving residents’ skills in using digital technologies; (2) leads the establishment of an urban network data center—also known as the “London Data Warehouse”—to promote the integration and sharing of cross-departmental and cross-administrative data in the city’s systems such as transportation, security, economic development, tourism, and others; (3) promotes the openness of the public data, uses the release of open data that conforms to open standards as an indicator of the success of its infrastructure initiatives, thereby enabling the integration of digital and traditional infrastructures; (4) integrates data from various departments—London is committed to building a 3D database of urban infrastructure that includes data from above-ground infrastructure and underground pipeline networks, and allows datasets to be correlated to form Linked Data, and to be visualized on applications.

Overall, Figure 9 summarizes that London and New York have developed legal norms for data governance according to the characteristics of their respective cities.

Figure 9.

Comparison of legal norms for smart construction in New York and London.

6. Lessons Learned and Recommendations for China

6.1. Building an Institutional Foundation for Smart City Development with Systematic and Scientific National Legislation

Central legislation should provide planning and guidance for smart city development from a holistic perspective. We put forward the following suggestions for improvement: (1) for data security issues, national legislation should first present a basic definition of data or data rights and clarify the boundaries of rights that should be protected. Data carry various types of information, involving multiple subjects such as users, platforms, and application layers, and are a key governance object for the sustainable development of smart cities. In practice, there is a problem with benefit distribution due to unclear data ownership and control. Therefore, the central legislation can explore the data rights confirmation system based on the classification of subjects, such as personal, public, government, and enterprise data [65]. (2) For data alienation issues, placing digital platforms and users in the traditional mode of private law regulation is no longer able to resolve the contradiction between the growing private power of digital platforms based on the technology and data they master and consumers’ rights. Therefore, the public power should intervene in advance, the obligations and responsibilities of large digital platforms should be confirmed by legal norms, and the legal governance should be adjusted from the post-regulation to the pre-regulation mode. Specifically, we can start from the technical application qualification review of the platform, the algorithm technology industry standard evaluation system, and the supervision of the whole process of algorithm operation, and build an economic law system that regulates digital platforms in advance [60]. The central legislation should make guiding provisions on algorithm accountability and transparency audits, especially with regard to how information is prioritized and targeted. (3) For public and government data opening issues, the central level should issue unified legal norms and formulate an overall governance plan based on an integrated smart city service platform, so that the barriers to data flowing between various administrative agencies, departments, and regions could be solved. The plan can form an effective interaction between various elements and subjects of smart cities by uniformly stipulating the scale, standard, format, and timeliness of data openness [66]. When exploring open issues such as cross-border data flow, systems such as the Pilot Free Trade Zone and Hainan Free Trade Port could be used for testing. The temporary norms can be formulated for observation and transition, legal interpretations will be used to make periodic adjustments to social digitization [61].

6.2. Implement Smart City Governance Measures with Comprehensive and Refined Local Laws and Regulations

At present, the national authorities mainly support and promote digital development through the issuance of policy documents. The details and implementation of contemporary local regulations formulated by various provinces in China are shown in Figure 10 [51]. Local legal norms could promote smart transformation measures for smart cities in the following ways.

Figure 10.

Overview of regional digital transformation regulation.

Smart cities should be developed on the basis of the cities’ capital industry. In terms of industrial policies to promote the economic development of smart cities, local governments can learn from the experience of smart city construction in New York and London, and formulate industrial policies and programs according to local conditions. The comprehensive leading provinces have reached a high level. In the future, more attention should be paid to the formulation of digital transformation standards for smart city construction and sustainable development, and to strengthen institutional cooperation and exchanges between them. The characteristic development provinces need to further improve the digital upgrading of local industries or industrial digital empowerment, accelerate the transformation to comprehensive leading provinces, and improve the radiation and driving effect on surrounding areas. The potential improvement provinces need to further tap the advantages of local smart industries, which can first connect, introduce, and support digital industries with smart government projects, so as to lay the foundation for transformation to the comprehensive leading provinces [1].

In addition to focusing on industrial policies for smart city development that adapt to local conditions, local legislation should also focus on the implementation of central legislation. The content of local norms can be improved in the following two aspects: first, in light of the mixed development situation brought about by the combination of the Internet and traditional industries, it is easy to generate repeated supervision or regulatory gaps. At this time, connecting local governments with the central regulatory agencies should become the focus of legislation in smart city governance. Accordingly, the following steps could be taken: (1) Clarifying the data security standards for smart cities; referring to relevant international standards and considering the specific national conditions of smart city information technology development to formulate data protection standards for each system of the smart city; (2) clarifying the standards for the reasonable use of data in smart cities such that the scope of data collection reflects the principle of necessity; (3) establishing a data registration and use system and determining the boundary between public and commercial use [67]. According to the different usage scenarios and purposes, the corresponding conditions and usage objects should be determined. These can be subdivided into three categories: The first is unconditional and unpaid use for public management reasons; the second is conditional and paid use for public utilities and property rights exercise, and the third is paid use for franchising to provide products and services.

Second, in terms of opening and sharing local government data, the following should be noted: (1) It is necessary to focus on refining and improving measures for data sharing. The Guizhou Province promulgated the “Regulations on Data Sharing and Openness of the Government of Guizhou Province”, thus establishing the principle of technology neutrality and clarifying the boundaries of open data; (2) with reference to the data classification and classification protection system proposed by Beijing in the 14th Five-Year Plan, clarifying technical and management protection measures at different levels, improved the data security monitoring and discovery processes, and the emergency response system; (3) there are still shortcomings in the open quality and utilization of local government affairs data. We can learn from London’s experience and refine the content of local norms by monitoring the actual development of the city. In addition, we can improve the timeliness and practicality of the open data, the effect of data innovation and utilization, the security management of the full data life cycle, and the guaranteeing mechanism.

6.3. Building a Safe and Sustainable Smart City Development Environment with a Polycentric Soft Law System

The social order in the digital age depends not on social control, but on people’s mutually beneficial behaviors. The multi-grid governance model requires that the behavior of each of our citizens conforms to the requirements of legal norms. It is necessary to reorganize the three different governance mechanisms of state administration, market, and society to form a synergy and benign interaction between them [68]. So that the nation should build a smart city governance mechanism led by the government in which all parties involved participate [69]. A polycentric soft law system in smart cities has the following features: (1) The government plays a leading role, and relevant departments are responsible for managing the unified data platform, regulating information utilization, and setting the information use rights. (2) Digital platform companies have certain rights to collect and use data, but should be subject to supervision. Industry self-discipline and other social organizations participate in the smart city standard formulation process. For example, the data standard operation and maintenance management control system and process are determined, and enterprises are guided to sort out the metadata and master data of their business activities, form a corresponding standardized data framework and model, and conduct effective monitoring and maintenance. Paying close attention to the relevant adjustments accompanying the process of industrial advancement and providing a path reference for formulating legislation are key at the mature stage of development. (3) Citizens, as the subject of information, enjoy the rights and vested interest in their personal information, and should supervise the status of their data held by the government and market entities.

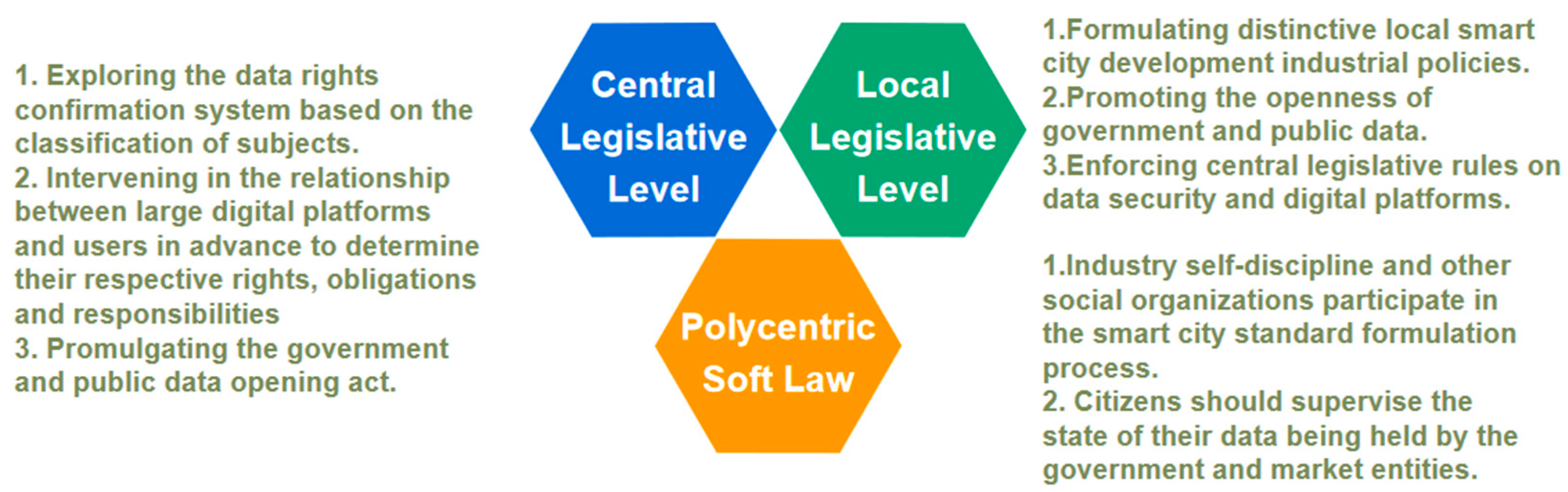

Overall, Figure 11 summarizes the specific path to improve the legal governance of smart cities in China.

Figure 11.

The specific path to improve the legal governance of smart cities in China.

7. Conclusions, Limitations, and Future Work

7.1. Conclusions

This study examined the functions, challenges, and solutions of legal governance in the construction of smart cities. According to the different statuses of digital economy development and the promulgation and implementation of laws and regulations in various provinces in China from 2013 to 2020, we divided the provincial intelligent development model into the comprehensive leading, characteristic development, and potential improvement type. The study found that sound central legislation and local legal norms tailored to local conditions could provide a safe and stable environment for smart cities to ensure their health and sustainability. However, the current legal governance in the key field of data is sometimes unable to achieve the expected goals. The reasons include the gaps in the legislation itself and the gap between legislation and implementation, mainly reflected in data security issues, data alienation issues, and the lack of openness of public data and government. Therefore, we examined the role the legal governance of New York and London, which were the world leaders in smart cities, play. We proposed suggestions for improving central legislation, local regulations, and social soft laws: (1) at the central legislative level, we recommended clarifying data and data rights, and exploring data attribution based on clear data classification, such as personal information, public data, and corporate data. As for the choice of supervision mode, the traditional ex-post empowerment and relief methods should be transformed into ex-ante supervision. Central legislative also should make guiding provisions on algorithm accountability and transparency audits, especially with regard to how information is prioritized and targeted. (2) At the local legislative level, we suggested local governments implement the relevant protection provisions of the Civil Code and the Personal Information Protection Law, and the supervision model should be changed from an ex-post protection model to an ex-ante supervision of digital platforms. In terms of technology, the requirements and standards for the quantity and quality of open data should be unified for the government and its various departments. Furthermore, market players and social organizations are encouraged to explore the economic and social value of government public data. (3) The participation of multiple subjects such as industry self-regulatory organizations in legislation should be regulated to improve the professionalism and technicality of smart city legal norms.

The methods and results of this study were important and provided a new perspective of economics and law for the study of smart cities in China. This study further filled the gap in the study of China’s smart cities from the legal system of risk identification and control, which could help regulatory bodies, policymakers, and researchers to make better decisions to overcome the challenges for developing sustainable smart cities.

7.2. Limitations and Future Work

This study had several limitations. First, it was difficult to fully investigate and measure the effect and function of normative practices using the case study method and normative research methods. Furthermore, only London and New York were selected as study cases, with limited information available about the resource endowment of each city. This paper built a basic legal framework for smart city governance but failed to conduct in-depth normative research on key issues, such as data security, personal privacy protection, and government data openness faced by smart city construction, combine information technology expertise.

In future research, we will divide cities into different categories based on the status quo of digital economy development in each province, and further concentrate on the issues such as joint legislation under the same model, and the distribution of central and local legislative powers. Therefore, there is still room for improvement in the analyses in future studies.

Author Contributions

W.H. and P.D. designed this manuscript. W.H. and P.D. wrote this manuscript. W.L. made scientific comments on this manuscript. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by (Shaanxi Provincial Philosophy and Social Science Fund Project) grant number (2017F004).

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have influenced the results reported in this paper.

References

- CAICT. China Urban Digital Economy Development Report. 2021. Available online: http://www.caict.ac.cn/kxyj/qwfb/ztbg/202112/P020211221381181106185.pdf (accessed on 4 July 2022).

- Scott, A.J.; Storper, M. The Nature of Cities: The Scope and Limits of Urban Theory. Int. J. Urban Reg. 2015, 39, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Young, M. Justice and the Politics of Difference; Princeton University Press: Princeton, PCN, USA, 1990; pp. 10–25. ISBN 0-691-07832-7. [Google Scholar]

- Keymolen, E.; Voorwinden, A. Can we negotiate? Trust and the rule of law in the smart city paradigm. Int. Rev. Law Comput. Technol. 2020, 34, 233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Nagenborg, M. Urban robotics and responsible urban innovation. Ethics Inf. Technol. 2020, 22, 345–355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Luo, P.; Liu, L.; Wang, S.; Ren, B.; Nover, D. Influence assessment of new Inner Tube Porous Brick with absorbent concrete on urban floods control. Case Stud. Constr. Mater. 2022, 17, e01236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hildebrandt, M. Balance or trade-off? Online security technologies and fundamental rights. Philos. Technol. 2013, 26, 357–379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Azevedo, L.; Carvalho, J.; Dos, M.; Rodriguez, M.; Pereira, A. Smart Cities: The Main Drivers for Increasing the Intelligence of Cities. Sustainability 2018, 10, 3121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Duan, W.; Maskey, S.; Chaffe, P.L.B.; Luo, P.; He, B.; Wu, Y.; Hou, J. Recent Advancement in Remote Sensing Technology for Hydrology Analysis and Water Resources Management. Remote Sens. 2021, 13, 1097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Angelidou, M. Smart cities: A conjuncture of four forces. Cities 2015, 47, 95–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Luo, P.; Zhao, S.; Kang, S.; Wang, P.; Zhou, M.; Lyu, J. Control and remediation methods for eutrophic lakes in the past 30 years. Water Sci. Technol. 2020, 81, 1099–1113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, K. The Inconvenient Truth about Smart Cities. Available online: https://blogs.scientificamerican.com/observations/the-inconvenient-truth-about-smart-cities/ (accessed on 21 May 2022).

- Reddy, S.; Babu, G.; Murthy, N. Transportation planning aspects of a smart city–case study of GIFT City, Gujarat. Transp. Res. Procedia 2016, 17, 134–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vijai, P.; Sivakumar, B. Design of IoT systems and analytics in the context of smart city initiatives in India. Procedia Comput. Sci. 2016, 92, 583–588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Wu, Y.; Zhang, W.; Shen, J.; Mo, Z.; Peng, Y. Smart city with Chinese characteristics against the background of big data: Idea, action and risk. J. Clean. Prod. 2018, 173, 60–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wen, J.; Deng, P.; Zhang, Q.; Chang, C.-P. Is Higher Government Efficiency Bringing about Higher Innovation? TEDE 2021, 27, 626–655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, X.; Wang, N.; Luo, P.; Yang, J.; Zhang, J.; Lin, K. Spatiotemporal Assessment of Land Marketization and Its Driving Forces for Sustainable Urban–Rural Development in Shaanxi Province in China. Sustainability 2021, 13, 7755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mu, D.; Luo, P.; Lyu, J.; Zhou, M.; Huo, A.; Duan, W.; Nover, D.; He, B.; Zhao, X. Impact of temporal rainfall patterns on flash floods in Hue City, Vietnam. J. Flood Risk Manag. 2021, 14, e12668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, W.; Duan, W.; Chen, Y. Rapidly declining surface and terrestrial water resources in Central Asia driven by socio-economic and climatic changes. Sci. Total Environ. 2021, 784, 147193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joshi, S.; Saxena, S.; Godbole, T. Developing smart cities: An integrated framework. Procedia Comput. Sci. 2016, 93, 902–909. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Xie, D.; Duan, L.; Si, G.; Liu, W.; Zhang, T.; Mulder, J. Long-Term 15N Balance After Single-Dose Input of 15N-Labeled NH4+ and NO3− in a Subtropical Forest Under Reducing N Deposition. Glob. Biogeochem. Cycles 2021, 35, 6959. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, X.; Yang, J.; Luo, P.; Lin, L.; Lin, K.; Guan, J. Assessment of the variation and influencing factors of vegetation NPP and carbon sink capacity under different natural conditions. Ecol. Indic. 2022, 138, 108834. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, W.; Wang, S.; Luo, P.; Zha, X.; Cao, Z.; Lyu, J.; Zhou, M.; He, B.; Nover, D. A Quantitative Analysis of the Influence of Temperature Change on the Extreme Precipitation. Atmosphere 2022, 13, 612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hefnawy, A.; Bouras, A.; Cherifi, C. Relevance of lifecycle management to smart city development. Int. J. Prod. Dev. 2018, 22, 351–376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haarstad, H.; Wathne, W. Are smart city projects catalyzing urban energy sustainability? Energy Policy 2019, 129, 918–925. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Huang, C.C.; Tan, Z.; Chen, Y.; Qiu, H.; Huang, C.; Li, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Li, X.; Shulmeister, J.; et al. Prehistoric and historicoverbank floods in the Luoyang Basin along the Luohe River, middle Yellow River basin, China. Quat. Int. 2019, 521, 118–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chintagunta, L.; Raj, P.; Narayanaswami, S. Conceptualization to amendment: Kakinada as a smart city. J. Public Aff. 2019, 19, e1879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weber, M.; Podnar, I. A Regulatory View on Smart City Services. Sensors 2019, 19, 415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Gil, R.; Aldama, A. Smart city initiatives and the policy context: The case of the rapid business opening office in Mexico City. In Proceedings of the 7th International Conference on Theory and Practice of Electronic Governance, Seoul, Korea, 22–25 October 2013; pp. 234–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duan, W.; Zou, S.; Chen, Y.; Nover, D.; Fang, G.; Wang, Y. Sustainable water management for cross-border resources: The Balkhash Lake Basin of Central Asia. J. Clean. Prod. 2020, 263, 1931–2015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamza, K. Smart city implementation framework for developing countries: The case of Egypt. In Smarter as the New Urban Agenda; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2016; pp. 171–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hámor-Vidó, M.; Hámor, T.; Czirok, L. Underground space, the legal governance of a critical resource in circular economy. Resour. Policy 2021, 73, 102171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, P.; Mu, Y.; Wang, S.; Zhu, W.; Mishra, B.K.; Huo, A.; Zhou, M.; Lyu, J.; Hu, M.; Duan, W.; et al. Exploring sustainable solutions for the water environment in Chinese and Southeast Asian cities. Ambio A J. Hum. Environ. 2021, 9, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zha, X.; Luo, P.; Zhu, W.; Wang, S.; Lyu, J.; Zhou, M.; Huo, A.; Wang, Z. A bibliometric analysis of the research on Sponge City: Current situation and future development direction. Ecohydrology 2021, 14, 2328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Repette, P.; Sabatini-Marques, J.; Yigitcanlar, T.; Sell, D.; Costa, E. The Evolution of City-as-a-Platform: Smart Urban Development Governance with Collective Knowledge-Based Platform Urbanism. Land 2021, 10, 33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, S.; Taeihagh, A. Smart City Governance in Developing Countries: A Systematic Literature Review. Sustainability 2020, 12, 899. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Zhu, Y.; Luo, P.; Zhang, S.; Sun, B. Spatiotemporal Analysis of Hydrological Variations and Their Impacts on Vegetation in Semiarid Areas from Multiple Satellite Data. Remote Sens. 2020, 12, 4177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Yang, Y.; Zhang, S. Research on the Measurement and Driving Factors of China’s Digital Economy. Shanghai Econ. Res. 2020, 6, 81–96. [Google Scholar]

- Kearney, A.T. 2021 Global Cities Index. Available online: http://www.199it.com/archives/1359892.html (accessed on 1 July 2022).

- Huang, K.; Luo, W.; Zhang, W.; Li, J. Characteristics and Problems of Smart City Development in China. Smart Cities 2021, 4, 1403–1419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nam, T.; Pardo, T.A. Conceptualizing smart city with dimensions of technology, people, and institutions. In Proceedings of the 12th Annual International Digital Government Research Conference: Digital Government Innovation in Challenging Times, College Park, MD, USA, 12–15 June 2011; Association for Computing Machinery: New York, NY, USA, 2011; pp. 282–291. [Google Scholar]

- Närvänen, L. Age, ageing and the life course. In Changing Worlds and the Ageing Subject; Routledge: London, UK, 2018; pp. 65–80. [Google Scholar]

- Cocchia, A. Smart and digital city: A systematic literature review. In Smart City: How to Create Public and Economic Value with High Technology in Urban Space; Dameri, R.P., Rosenthal-Sabroux, C., Eds.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2014; pp. 13–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soe, M.; Drechsler, W. Agile local governments: Experimentation before implementation. Gov. Inf. Q. 2018, 35, 323–335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fisher, E. How Less Alienation Creates More Exploitation? Audience Labour on Social Network Sites. tripleC: Commun. Capital. Critique 2012, 10, 171–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andrejevic, M. Exploitation in the data mine. In Internet and Surveillance; Routledge Press: London, UK, 2013; pp. 71–88. ISBN 9780203806432. [Google Scholar]

- Fuchs, C. Social Media, Big Data, and Critical Marketing; Routledge Press: London, UK, 2018; pp. 467–481. ISBN 9781315630526. [Google Scholar]

- Edwards, L. Privacy, security and data protection in smart cities: A critical EU law perspective. Eur. Data Prot. Law Rev. 2016, 2, 28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- National Computer Network Emergency Technology Handling Coordination Center, China Cyberspace Security Association. App Illegal Collection and Use of Personal Information Monitoring and Analysis Report. Available online: https://unctad.org/system/files/official-document/wir2017_en.pd (accessed on 1 July 2022).

- CAICT. Data Security Analysis and Coping Strategy Research. Available online: http://www.caict.ac.cn/kxyj/qwfb/ztbg/202201/t20220118_395765.htm (accessed on 17 June 2022).

- CAICT. Digital Rule Blueskin Report. Available online: http://www.caict.ac.cn/kxyj/qwfb/ztbg/202112/P020211210403054888030.pdf (accessed on 21 May 2022).

- Li, C.; Liu, X.; Dai, Z.; Zhao, Z. Smart City: A Shareable Framework and Its Applications in China. Sustainability 2019, 11, 4346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Chen, C.; Wang, Z.; Guo, B. The road to the Chinese smart city: Progress, challenges, and future directions. IT Prof. 2016, 18, 14–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- CAICT. Government Data Sharing and Open Security Report. Available online: http://www.caict.ac.cn/kxyj/qwfb/ztbg/202101/P020210114593587797769.pdf (accessed on 21 May 2022).

- Kearney, A.T. 2020 Global Cities Index. New Priorities for a New World. Available online: https://www.kearney.com/global-cities/2020 (accessed on 21 May 2022).

- Janssen, M.; Voort, H. Adaptive governance: Towards a stable, accountable and responsive government. Gov. Inf. Q. 2016, 33, 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, B.; Wang, X.; Pei, L.; Su, Y.; Zhang, D.; Wang, Y. Identifying the spatiotemporal dynamic of PM2.5 concentrations at multiple scales using geographically and temporally weighted regression model across China during 2015–2018. Sci. Total Environ. 2021, 751, 141765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shah, J.; Kothari, J.; Doshi, N. A survey of smart city infrastructure via case study on New York. Procedia Comput. Sci. 2019, 160, 702–705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, P.; Xu, C.; Kang, S.; Huo, A.; Lyu, J.; Zhou, M.; Nover, D. Heavy Metals in Water and Surface Sediments of the Fenghe River Basin, China: Assessment and Source Analysis. Water Sci. Technol. 2021, 84, 3072–3090. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Angelidou, M. The role of smart city characteristics in the plans of fifteen cities. J. Urban Technol. 2017, 24, 3–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morozov, E.; Bria, F. Rethinking the Smart City. Democratizing Urban Technology; Rosa Luxemburg Foundation: New York, NY, USA, 2018; p. 2. [Google Scholar]

- Ferreri, M.; Sanyal, R. Platform economies and urban planning: Airbnb and regulated deregulation in London. Urban Stud. 2018, 55, 3353–3368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferrara, R. The Smart City and the Green Economy in Europe: A Critical Approach. Energies 2015, 8, 4724–4734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Zvolska, L.; Lehner, M.; Voytenko, Y.; Mont, O. Urban sharing in smart cities: The cases of Berlin and London. Local Environ. 2019, 24, 628–645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Vojković, G.; Katulić, T. Data protection and smart cities. In Handbook of Smart Cities; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2020; pp. 1–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almirall, E.; Wareham, J.; Ratti, C.; Conesa, P.; Bria, F.; Gaviria, A.; Edmondson, A. Smart cities at the crossroads: New tensions in city transformation. Calif. Manag. Rev. 2016, 59, 141–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Founoun, A.; Hayar, A. Evaluation of the concept of the smart city through local regulation and the importance of local initiative. In Proceedings of the 2018 IEEE International Smart Cities Conference (ISC2), Kansas City, MO, USA, 16–19 September 2018; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Meier, J. Collaborative Governance: Private Roles for Public Goals in Turbulent Times by John D. Donahue and Richard J. Zeckhauser. Int. Public Manag. J. 2011, 14, 464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hagemann, R.; Huddleston, J.; Thierer, A. Soft law for hard problems: The governance of emerging technologies in an uncertain future. Colo. Technol. Law J. 2018, 17, 37. [Google Scholar]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).