1. Introduction

The impact on tourism imposed by the health crisis of COVID-19 and the international economic crisis reached unthinkable and unsuspected dimensions. These aspects constitute a factor of change that has affected and will affect the immediate future of tourism [

1,

2]. Tourism enterprises need to focus their activity on innovation and continuous improvement that allows them to adapt to new situations in an eminently changeable world.

The current situation implies a process of unlearning in order to learn new methods, models and policies. This involves adopting and incorporating new patterns; proactively transforming old governance practices; and assimilating customs, attitudes and ways of doing to deliver rewarding, new, and value-added experiences in tourism destinations, as well as products and services that make a significant difference [

3,

4,

5,

6].

The proposed community-based tourism model incorporates into management a procedural system that is based on endogenism and the sustainable enhancement of natural resources to provide a service that is rewarding to tourists through new, experiential experiences.

The community tourism model is considered within the welfare policies developed for the Millennium Assessment (2003–2005). These are related to the need to comply with the requirements of freedom of choice and action, good social relations, and the necessary material to live. At the same time, it is beneficial from the perspective of social and psychological sciences, based on achieving the subjective well-being of the individual and emphasizing the importance of participation in social life. This is in accordance with several theories such as Ryan and Deci’s theory of self-determination [

7]; the homeostasis theory of subjective well-being [

8]; the values-based quality of life index [

9]; and the theory of welfare based on needs, which was developed by Tulla and Tuuli [

10], who added doing as the fourth need.

The tourism sector has become a representative activity for economic development; however, mass tourism models generate social inequality and represent a risk for sustainability [

11,

12,

13]. Therefore, another philosophy of tourism models must be adopted that is not based on the excessive consumption of superfluous products that waste natural resources, a philosophy that benefits tourists and society based on the broader concepts of sustainability and that transforms the unequal structure of development to achieve a fairer and more equitable society.

In order to respond to the new scenario, it is necessary to consider dimensions and variables that have not been considered before, the most important of which are the protection of employment, the generation of trust and security, the harmonization of business protocols and procedures, the incorporation of sustainability in all its dimensions, promoting innovation and social responsibility in different systems and processes, and attending to new demand segments by prioritizing the demands of inclusive tourism and accessible tourism. These are criteria addressed by the authors [

14,

15,

16,

17] and with which we agree. This is why we propose a new model of community-based tourism that starts from theory to evaluate, through a complex methodological procedure, a tourism model that promotes innovation and the use of endogenous resources, and strives to give tourism value to the natural resources of the environment through their sustainable use.

Faced with the reality of post-COVID-19 tourism, some experts, researchers, specialists, and teachers are questioning the predominant tourism models and incorporating new demands into a prospective design with a strategic projection of the new tourism that is emerging, as is the case of alternative tourism within which community tourism is conceptualized through ideas that have been put forward by various authors [

4,

18].

In this scenario, community tourism networks emerge as an effective way of uniting communities, support institutions, and human resources to share a vision of sustainable tourism development, which seeks to reconcile the objectives in the interest of achieving greater economic efficiency with the principles of social equity, cultural identity, and the preservation of natural resources [

19]. One example of this is the Sustainable Tourism Network (REDTURS), created by the International Labor Organization (ILO) with the mission of supporting training processes and strengthening community tourism networks in Latin America, to diversify sources of employment and income, and to value their culture and strengthen social cohesion [

20].

Of the 33 countries that make up Latin America, 50% of them have created community tourism networks. The Plurinational Federation of Community Tourism of Ecuador (FEPTCE) was created in 2002 with the aim of furthering environmentally sustainable tourism activity that promotes the conservation of nature as an alternative to activities that are harmful to the environment, and to articulate a strategy for the defense of the community territories in the face of the appetites of external actors and the extractivist activity that preys on natural resources and threatens the disintegration of the culture and traditions of the original peoples [

21]. The 39 community tourism enterprises that exist in the country are affiliated and organized in the FEPTCE. Its importance has been demonstrated since its foundation through the role it has played in maintaining community tourism activity during the difficult conditions imposed by the health situation experienced as of 2020, and during the recovery of the tourism sector in the post-COVID-19 stage.

The report of the Economic Commission for Latin America and the Caribbean (ECLAC) that evaluates the effects of the pandemic on tourism in Latin America and the Caribbean points out that one of the most notorious effects is the almost total paralysis of international passenger flows of all kinds, which has especially affected the global tourism industry [

22] (p. 1).

These aforementioned criteria demonstrate the relevance and timeliness of this research, whose scientific result focuses on the search and updating of theoretical and methodological postulates in order to configure a theoretical model for community-based tourism that emerges from the complex health and economic situation in effect as of 2019. The aim is to offer a theoretical contribution to update current tourism models and perfect the traditional character based on old practices and patterns that do not respond to the current potential and demands of post-COVID-19 tourism and the current economic scenario, without ignoring the indicators of sustainability.

The concept of community-based tourism is first referred to by Peter E. Murphy in 1985 [

23], wherein he offers an ecological and community-based approach to tourism that is still relevant in 2022 and provides the first differentiating elements compared to other tourism models.

Community-based tourism began to gain momentum in the late 20th and early 21st centuries as a response to the harmful environmental consequences of mass tourism. From the beginning, it has been linked to the so-called alternative tourism that emerged from the concern for environmental protection and the change in the excessive consumption habits that lead to the waste of resources [

24].

Some authors describe the existence of four tourist ideologies: the first is related to the search for happiness in hedonism as a key value that takes place in certain tourist areas; second, the flight from the increasingly oppressive everyday world; third, the encounter with the other, which refers to the exchange with exotic populations and landscapes; and fourth, the return to nature as a source of mental and physical health [

25]. The theoretical model of community tourism seeks to fill the gap of the last two ideologies, that is, to offer a space and a tourist practice that emerges from unique experiential experiences based on the exchange of cultures and the enjoyment of exotic natural landscapes that satisfy the preferences of tourists, in addition to being able to experience a return to nature as a source of health and life.

The historical–cultural activity encompasses a special meaning for community tourism, with the tourist value enhancement of certain ancestral cultural manifestations and museum pieces that are part of the historical and cultural heritage of community tourism undertakings. Museums are increasingly emphasizing public education and playing an important role in maintaining national, regional, and local identity [

26,

27].

Museums exist as tourist products that, together with the areas and places of archaeological sites, constitute an important attraction for visitors who prefer to enjoy community tourism. An example of this is the Museum of Community Tourism in Aguas Blanca [

28]. Tourists who access the facility are attracted by the archaeological pieces and cultural historical heritage that are exhibited in the community museum.

In terms of changes in habits and values, the author Támara Budowski [

29] in his essay refers to the changes in habits and values, in the sense of seeking deep, enriching experiences characteristic of the 1960s, the popularity of outdoor activities in the 1970s, and the concern in the 1980s for health, natural food, and fitness. These are goals that can be achieved in less-developed countries, but which still exhibit an abundance of natural, rural landscapes, diverse flora and fauna, and unspoiled or little-disturbed natural areas.

As latent limitations, the authors [

30] point out that there is a notable increase in projects based on mass tourism, where few benefit, and there is a growing deterioration of the environment and an increase in poverty due to the priority given to this type of tourism. The traditional idea of satisfying both the interests and needs of those who offer and those of the tourists who demand this type of service is maintained, without taking into account the preservation of the environment, and the well-being and quality of life of the communities where the tourist activity takes place.

There is no single scientifically accepted concept of community tourism. Its conceptualization has gone through an international discussion full of debates and learning. Its definitions arise from the contribution of various social actors, academics and non-governmental organizations such as the Plurinational Federation of Community Tourism of Ecuador (FEPTCE), which defines it as solidary tourism activity that allows the active participation of the community from an intercultural perspective, proper management of natural heritage, and the appreciation of cultural heritage, based on a principle of equity in the distribution of local benefits, under the principle of the protection of natural resources and sustainable relations with the environment [

31].

Since 1980, in the Manila Declaration of the World Tourism Organization [

32], it has been declared that the tourism planning policy of countries should be developed at the local, regional, or national levels, within a framework of national planning, where such policies should be subject to regular quantitative and qualitative evaluation. In this way, the national preponderance of tourism planning will be pushed to consider the local as a new scale to incorporate. All this happens within a scenario where there is a growing demand from several territories that were displaced from the large-scale tourism planning model and from then on the demand for community tourism increased annually, with a significant rebound associated with the pandemic of COVID-19 and the post-pandemic time period [

4,

18]. In this way, the demand for community tourism is demonstrated by tourists who prefer rural tourism, nature tourism, and indigenous tourism, and who seek to satisfy leisure away from mass tourism and to enjoy new experiences in a healthy environment linked with the natural environment.

A review of the literature has shown that the seeds of community-based tourism in Ecuador date back to the 1980s due to the influx of rural tourism and indigenous tourism, which, as expressions of alternative tourism, were borne as a response from the indigenous and Montubio peoples and nationalities to the exploitation of natural resources by the large oil and agricultural companies, which sowed poverty and polluted the environment at the cost of depredating the country’s natural resources. In the 1970s, the first community-based tourism enterprise in Latin America was set up on the island of Taquile in Peru [

33]. In Ecuador, the community-based tourism model was introduced in the community of Agua Blanca in the province of Manabí in 1979, and in Capirona in the province of Tena Ecuador in 1989 [

28,

34]. Unfortunately, the lack of academic research work in those years prevented these experiences from becoming known, and it was not until well into the first decade of the current century that the experiences became known. It is now a matter of promoting community-based tourism enterprises, but with the contribution of a procedural methodology that is capable of filling the gaps of other tourism models and at the same time creating a management environment based on innovation and endogenism in order to face the challenges imposed by the changing situation of today’s world.

The fundamental background of the research includes the main goals of the Plurinational Federation of Community Tourism in Ecuador (FEPTCE), which aims to promote and strengthen community-based tourism initiatives on a national and international scale, as well as improve the quality of life of communities through sustainable development and the maintenance of cultural identity [

35,

36].

There are several authors who in other countries have carried out research related to community tourism, and as a common denominator it can be seen that it arises in less-developed countries and in the contexts of rural areas inhabited by peasant communities and indigenous peoples. A review of the reflected literature has been the object of study for numerous academics and researchers on an international scale.

In Japan in 2006, the author Hiwasaki demonstrated in his study that community tourism can provide the use of the institutional regulatory framework, self-regulation linked to conservation, high environmental awareness, and the existence of associations, as key elements to achieve the success of community tourism activity. For this, it is important to take into account the existing challenges for tourism in protected areas, which can contribute to the sustainable management of these areas. The paper exposes the need for future research based on the broader applicability of the lessons learned from the Japanese experience [

37].

In China in 2007, the authors Ying and Zhou used the qualitative method to compare the experiences of unitary tourism in two tourist destinations (Xidi and Hongcun) that are adjacent, and share the similarities of environments and notable differences which are located in the results of tourism management. A new approach for the development of community tourism is shown, and the influence of community participation and the power relations between tourism actors are analyzed in both cases [

38].

In Uganda on the African continent, a social investigation was carried out linked to the community’s acceptance of community-based tourism [

39]. The research was carried out in the community of Bigodi, within a population of 385 adults who have been involved in tourism since 1991. The results of the work showed that residents believe that tourism creates community development, improves agricultural markets, and generates income and good fortune.

In Turkey, the authors Alaeddinoglu and Can in their 2011 research manage to determine a key limitation for community tourism that is given in the lack of identification and classification of the country’s nature tourism resources, which prevents its promotion. However, all this occurred in the face of a growing environmental awareness of consumers to satisfy their leisure expectations, through the search for new tourist resources that are based on the use of natural resources. For this, they carried out the identification and classification of a group of natural resources and determined their touristic value. The research findings revealed that the sites studied had medium and high levels of attraction and low levels of infrastructure. The results showed that the level of degradation in the studied area was very low, which required an approach that allowed for the investigation of relatively untouched areas with a high potential for tourism development [

40].

Studies with objectives similar to those analyzed previously were carried out in other countries, such as Hawaii [

41], Belize [

42], Australia [

43], Dominica [

44], Peru [

45], Brazil [

46], Canada [

47], Namibia [

48], Tanzania [

49], Madagascar [

50], Cape Verde [

51], India [

52], Fiji [

53], South Africa [

54], Thailand [

55], Italy [

56], Romania [

57], and Cambodia [

58].

In Ecuador several studies have been developed:

There are studies that highlight the perception of professionals regarding community tourism and qualify it predominantly as fair and poor according to surveys applied in their research. It is clear that tourism actors focus more on traditional models of mass tourism and underestimate the development of other models such as community tourism, which was confirmed by Bernabé-Rosario, who analyzed the influence of rural tourism from an economic connotation in Chiquián Ecuador [

59].

Other authors reflected on the challenges facing tourism in general and community tourism in particular in the times of the pandemic. They warn about the need to rethink the way of conceiving and carrying out tourism, and emphasize the relationship between community tourism and Ecuador’s structural problems. Likewise, they consider that tourism sustainability should not remain an unrealistic project discourse but become a real objective that allows for compliance and the permanent monitoring of the sustainability indicators established for Ecuador, and satisfies the international commitments in this regard, in concurrence with what has been pointed out by several authors [

60].

The community tourism model that is proposed includes a process of evaluation and continuous improvement that allows for evaluating and improving the system according to the real situation in which it is developed. It is based on the experiences provided by other models, but adapted to real conditions based on local resources to offer unique and unforgettable experiences.

In other investigations, a descriptive study was carried out based on the review of sources and this study identified the initiatives and product lines in community development and tourism as mechanisms that allow them to exist in a dignified manner in the territories [

61]. Other authors presented a community-based tourism management model aimed at the sustainable development of the Liquigüi community. The management model presented is made up of diagnostic, planning, programming, execution, and closing phases, which includes the actions to be executed and the tangible results [

62].

There is research that reveals the synergy of the development of community tourism in Ecuador based on its theoretical considerations and presents a valuable theoretical framework of reference for new research on the subject [

63]. Other studies have conceived community tourism as a local development strategy promoted by the State for the claim and self-management of territories and natural resources. The authors consider that social entrepreneurship in community tourism in the province of Manabí in Ecuador requires a profitable economic dimension because it is a social entrepreneurship with an organizational structure with natural, cultural, and human resources and capacities in which investment is necessarily economical for its maintenance [

64,

65,

66].

The proposed community tourism model considers the public–private partnership as a key element that allows for the necessary financial and material support to make a quality alternative tourism activity a reality.

The study carried out in 36 communities and community tourism centers in Ecuador analyzed the social impact and sustainability of the projects. They identified that community tourism is linked to the most vulnerable segment of the Ecuadorian population that is located in rural areas. Positive contributions and weaknesses were also analyzed. Some doctoral studies have also focused on the study of management in community tourism models [

67,

68,

69].

In one of the investigations carried out, a rescue model of local territorial development is proposed for the future of community tourism in Ecuador. The work focused on studying the historical evolution of the tourist modality to understand its socio-spatial configuration and evaluate the behavior of local, national, and international actors and local and community perceptions on the impact of tourism on the quality of life of the population [

70].

In contrast to the findings made in the investigations analyzed above, another study was carried out where the relationship between the socio-economic development of the coastal sector of the province of Guayas and the lack of a community tourism development model was analyzed. In this work, an alternative form of community development is proposed to provide a quality service to the growing number of tourists who visit the sector [

71].

The diversity of publications and scientific research on rural tourism and community tourism use different approaches with different theoretical perspectives. Economic and quality of life criteria predominate for populations living in the most vulnerable spaces [

72,

73] and business initiatives are important for local development [

74,

75]. It is noted that there are attempts to configure models and recent studies on the effects of COVID-19 on community tourism.

It can be seen that the studies carried out do not reach a level of completeness that would allow for an evaluation and join action on the problems faced by community-based tourism activities. Some studies focus on the economic aspects, entrepreneurship, and management within the framework of local development; others are committed to evaluating the management of community tourism in extraordinary health situations. The theoretical model of community-based tourism aims to evaluate tourism management in a comprehensive manner and for this purpose it begins with governance and relations with the social environment, and the promotion of a systematic climate of innovation and continuous improvement, while analyzing the social component of the environment, supply, demand, and the balance of these indicators, problems that are not addressed in any of the studies carried out.

The external components and integrated management are analyzed through seven subsystems that in a dynamic and interrelated way must respond to the requirements of a tourism model based on endogenism and the enhancement of tourism value of the natural resources of the environment, the relationships with the social environment, innovation, and continuous improvement, that together allow us to face the situations that occur in today’s changing world.

These findings show the need for the tourism sector to be systematically updated in the dialectics of scientific knowledge in order to generate new knowledge that will enrich tourism theory and practice.

The scientific problem investigated in this study is formulated based on the following central question: What are the subsystems that a theoretical model of community-based tourism should include in order to face the changes that the context imposes and will impose on the tourism of the future?

The aim of the paper is to present a theoretical model of community-based tourism, explain its component subsystems, provide a theoretical–methodological foundation, and discuss the indications of its practical implementation in order to face the changes that the tourism of the future imposes and will impose.

1.1. Theoretical Delimitation

1.1.1. Theoretical Models of Tourism: Their Importance

Theoretical models constitute a type of scientific result. They express the relationships between variables considered significant for the functioning of the system [

76] (p. 18). They are valuable because they fulfil important functions, such as explaining, describing, predicting, and transforming reality. Their importance is due to their ability to abstract the tourist reality and represent it in a synthetic way with its complex and multiple causal relationships as a means for scientists to synthesize complex circumstances and events.

In the literature, there are multiple classifications of tourism models. This paper delves into theoretical models as schemes that connect the reality of tourism management with theory, the purpose of which is that they become a tool to understand and verify community-based tourism from other perspectives and generate new hypotheses that enable the evaluation of the effect of novel dimensions and variables that affect its origin in order to design meaningful tourism models. The main qualities of theoretical models are consistency, inclusiveness, and ease of understanding [

77].

De Oliveira-Santos [

77] analyzed different theoretical models of tourism in order to understand the functioning mechanisms and their structural organization. He considered only those models described by diagrams and grouped them into (1) special-approach models, (2) those expressing their fundamental relational elements, (3) systemic-approach models, and (4) structural models.

De Armas-Ramírez et al. [

78] pointed out that both model and system are theoretical contributions that allow new knowledge to be obtained about the object of research and that there are close links expressed between model and system because the model always has a systemic character and the system is better understood when represented by a model. Therefore, both combine the scientific methods and procedures of modelling and the systemic approach, which requires theoretical reflections consistent with their specificities. Modelling is a special form of mediation, where the model is similar to the object under investigation and constitutes its copy to a large extent, as it has a scientific character and organic unity.

A model makes it possible to appreciate the object under study, and interpret it and evaluate it in its entirety or in part, depending on the problem guiding the research activity and the epistemological foundations handled by the researcher [

79].

Trujillo-Villena [

80], in their master’s thesis in tourism business management, presented a promotional model to promote tourism in the city of Guaranda using a qualitative and descriptive approach. For analysis, the author considered the contributions of [

81,

82,

83]; for tourism promotion models, they considered [

77,

84]; and in relation to the 2.0 promotion models, they used the criteria of [

85,

86].

Franco et al. [

87] performed a theoretical study of 12 tourism models to understand the functioning of the system. They discussed a few models for analysis, as well as their implications for tourism destinations, with a view to developing a relevant theory. The study revealed that theoretical models serve several purposes, including the ability to express and simplify reality, predict the formulation of a theory and, at the same time, constitute a set of natural conditions that will be replaced in the future by a theory.

Vitorero-Aspiazu [

88], in their degree work, created a design through a sequential scheme that defined the stages of the model for sustainable local tourism management. The analysis focused on management models in which the sequential stages were included: planning, organization, direction, and control.

1.1.2. The Community-Based Tourism Model

Establishing the typology of a given tourism model is not easy, given the diversity of criteria that exist in this regard [

77,

89,

90]. In this sense, the United Nations World Tourism Organization (UNWTO), in its operational definitions of types of tourism, does not define some modalities, such as community-based tourism, indigenous tourism, or other concepts historically related to these practices. This is why some authors believe that these modalities are located within rural tourism because of the experiences they include, such as the spectrum of products, the places or spaces visited, the activities carried out, and the environments and their characteristics, which helps avoid terminological confusion.

The UNWTO defines the rural tourism model as a type of activity in which the visitor experience is related to a broad spectrum of products linked to nature activities, agriculture, ways of life, rural cultures, angling, and sightseeing [

91] (p. 35).

Cabanilla [

92] presents a table for constructing the concept of community-based tourism in its historical evolution from 1989 to 2011. This table synthesizes chronologically different concepts using the criteria of different authors consulted and reflects the different names, emphases, and perspectives of the concepts [

63,

93,

94,

95]. Some non-coinciding points of view include cultural, social, environmental, and economic aspects related to management, operation, business organization, participation, associativity, and sustainability, among others.

Due to the recent development of these tourism practices and the need for reconceptualization accepted by the academic and scientific community, as suggested by Cabanilla-Vásconez [

92,

94], there is a lack of consensus in the conceptual clarification that focuses on the essential and repeatable features that transcend the conceptual–methodological system of tourism due to its multidisciplinary nature.

One of the issues that has not been sufficiently addressed up to 2018 is related to the sustainability of community-based tourism as a model based on the use of local indigenous resources, and sustainability as a resource for the preservation of nature that serves as the setting for the tourist activities developed.

In 2019, Navas Ríos carried out a systematic review of the literature in the Scopus database through a series of lexical query equations related to community-based tourism, with an adjacency matrix entered into Gephi software developed by students at the University of Technology of Compiègne (UTC) in France, and arrived at a definition constructed from the key contributions of the authors consulted [

24].

Navas-Ríos [

24] points out that community-based tourism, from the beginning, has been envisioned as an offer of competitive quality and sustainable services in small non-urban localities that become an alternative source of income and, at the same time, a means to overcome poverty with community economic benefits that implicitly promote fair, equitable, and sustainable economic development. It is the local community that, using its natural and cultural resources and social capital, (1) designs, develops, implements and promotes a fair, equitable, and sustainable economy and (2) designs, develops, implements, and controls the tourism product to be offered and, at the same time, is an active part of it, respecting and conserving natural resources and socio-cultural wealth, satisfying the visiting tourists’ needs from the quality experiences lived and shared with the local community and enabling them, in turn, to become aware of and learn about local and community wisdom [

24].

This contribution is of vital importance because it allows understanding the concept in its dimensions and indicators linked to its evolution and configuration and integrates its essential repeatable features, which facilitates the scientific conceptual development of community-based tourism.

León-Gómez [

96] addressed the problems associated with community-based tourism models. In their doctoral thesis, Dynamic Stochastic General Equilibrium Models (DSGE) for Tourism Development, the author aims to not only respond to the problems of estimation presented by these models but also to deepen their generalization for the tourism field. This constitutes a support for political actors and researchers in the interest of achieving greater effectiveness with highly accurate macroeconomic models that consider all aspects of the contribution of tourism to economic growth.

Rodríguez-Jiménez and Martínez-Martínez [

97] considered the community model as a form of responsible tourism with an approach that can be assumed in the scenario of the new normality. They highlighted it as an effective way to promote a new model of tourism management.

Segovia-Chiliquinga [

98], in their doctoral thesis in public management and governance, presented a theoretical functional model with its own characteristics of governance for the development of community-based tourism in the canton of Montalvo. One of their contributions is the theoretical systematization achieved in the concept of governance, in which the contributions of the authors consulted are analyzed in the context of community-based tourism. The relationships between actors with national, local, and regional governments, environmental protection, the sustainable use of resources in responding to tourism demand, alliances between the public and private sectors, and endogenous disorganization, among other variables to be considered within governance, are highlighted as important aspects.

Zambrano-Cancañón et al. [

99] developed a model of organizational change management with lean thinking in tourism services by analyzing the components of both philosophies and identifying their similarities; a model that should be considered in light of the changes imposed by COVID-19 and the international economic situation.

1.1.3. Innovation and the Quintuple Helix

The innovative model of the quintuple helix enables the exploration of sustainable development from the perspective of the potential that each territory possesses in terms of tourism and its attractions. The model enables the analysis of their distribution, as well as their advantages and disadvantages [

100]. The model also enables the in-depth examination of the roles of state actors, businesses, universities, the environment and society, and their relationships with the appropriate use and exploitation of resources [

101].

One of the most interesting issues of the quintuple helix model is the incorporation of environmental and social dimensions, which undoubtedly ensures a more comprehensive and complete examination of community-based tourism management [

101].

All this is important because of the relationships that exist between community tourism and sustainable tourism. Tourist activity represents an important contribution to the country’s economy, but at the same time its inadequate management can generate a considerable environmental imbalance.

Unlike other forms such as models of mass tourism activity, community tourism can be an instrument to create new income through the creation of jobs at the local and community levels, thereby reducing migration to cities and the abandonment of the countryside, reducing inequalities in local communities, and providing pathways for rural development [

102].

The management objectives of the theoretical model of community tourism are aligned with the objectives of sustainable development as established in the Report of the World Commission on Environment and Development, approved in 1987 [

103]. The model is committed to maintaining high economic efficiency by reducing unnecessary expenses for energy, water, fuel, provisioning, and food, among others, as well as guaranteeing part of the supplies with endogenous production. Environmental conservation constitutes another of the objectives of the management of the community tourism model, to the extent that it is committed to maintaining the adequate and sustainable use of the natural resources of the environment, and working to create a high level of environmental awareness not only among workers, but also in tourists and the surrounding social community. Work is being conducted to achieve social equity with the opening of new jobs and the revitalization of commerce in the community to improve the living conditions of the personnel linked to the enterprise and the surrounding community.

For the community tourism model, sustainability is not an end goal in of itself. It represents a new form of citizen coexistence, in diversity and harmony with nature, to achieve good living, the sumak kawsay, as expressed in the Constitution of Ecuador [

104], which is guaranteed through the set of internal relationships of the model, innovation, evaluation, and continuous improvement.

The quintuple helix model represents an integral interaction, an exchange of knowledge that includes five subsystems or helixes, where the education system, the economic system, the environmental setting, civil society with its culture and media, and the political system are represented. They provide inputs that can help build more inclusive and sustainable public policies on innovation, which represents a real development perspective for community-based tourism [

105].

The quintuple helix model constitutes a process that focuses on tourism development in an integral way, as it guarantees the development of science, technology, innovation, protection, and the care of the environment and society. It is a mechanism that facilitates knowledge transfer and promotes international interest using different approaches. Innovation processes are described as a set of activities for solving different types of problems through the participation of actors who use their knowledge, interests, habits, behaviors, and experiences to solve multiple problems [

106] (p. 95). The model unfolds from the institutional framework, wherein innovation emerges as a systemic phenomenon that depends on the level of articulation of organizations. Innovation as an interactive and social phenomenon allows it to be qualified as systemic in nature.

It is important to study the ways in which innovative processes take place. Among the main contributors of valuable inputs to the model are Arocena and Sutz [

106], Etzkowitz and Leydesdorff [

107], Carayannis and Campbell [

108], and Park [

109].

2. Materials and Methods

The beginning of tourism as an economic activity in the country dates back to 1930 when the Tourism Promotion Law of Ecuador was enacted [

110]. In 1947, the first tourist operations as such began and the first Ecuadorian Tours travel agency was created. From then on, the tourism sector experienced progressive growth with priority given to the growth of mass tourism projects.

Once Ecuadorian tourism began to gain strength in the national economic context, alternative tourism, which, among others, refers to rural tourism, nature tourism, indigenous tourism, and community tourism itself, was presented as an important socioeconomic catalyst in disadvantaged areas, especially those that exist in rural settings [

72]. In 1979 the Agua Blanca community tourism facility was founded on the Ecuadorian coast and in that same decade other similar ventures began to emerge in the Amazon, as a result of the resistance of the indigenous and Montubio communities to the extractive activities of oil and wood that represented a decrease in their territories and the privatization of their resources, bringing as consequences more poverty and marginalization for the exploited territories [

28].

In 1997, the Special Law on Tourism Development and the Special Law on State Decentralization and Social Participation were published. Under the approved regulations, a decentralization strategy was launched that included sectional governments to boost tourism activity [

110] and it is from then on that community-based tourism ventures begin to gain strength.

This research was carried out between 2018 and 2022 at the Technical University of Manabí, Ecuador. An interdisciplinary and transdisciplinary approach to community-based tourism was followed to present a theoretical model that explains the component subsystems, its theoretical and methodological foundations, and the indications for its practical implementation, which will make it possible to face the challenges that the tourism activity of Ecuador will face in the future.

Ecuador is located in the northwest of South America. It is bordered to the north by Colombia, to the south and east by Peru, and to the west by the Pacific Ocean through 670 km of coastline with several beaches. It is the smallest of the Andean countries, at 252,000 sq. km. It is crossed by the equatorial or equinoctial line, and is also crossed from north to south by the Andes Mountains. To the west are lowlands bordering the Pacific Ocean. To the east are lowlands that form part of the Amazonian plain and have a relatively flat topography. There is an archipelago located 1000 km off the coast, called the Galapagos Islands. Ecuador has two large hydrographic systems, the Pacific basin and the Amazon basin, with several permanent rivers that irrigate the entire territory.

The country’s location on the equator produces little seasonality throughout the year. There are two distinct seasons: wet, or winter, and dry, or summer. The length of the seasons varies regionally.

The analysis of the tourism situation in the country forms the basis of this study.

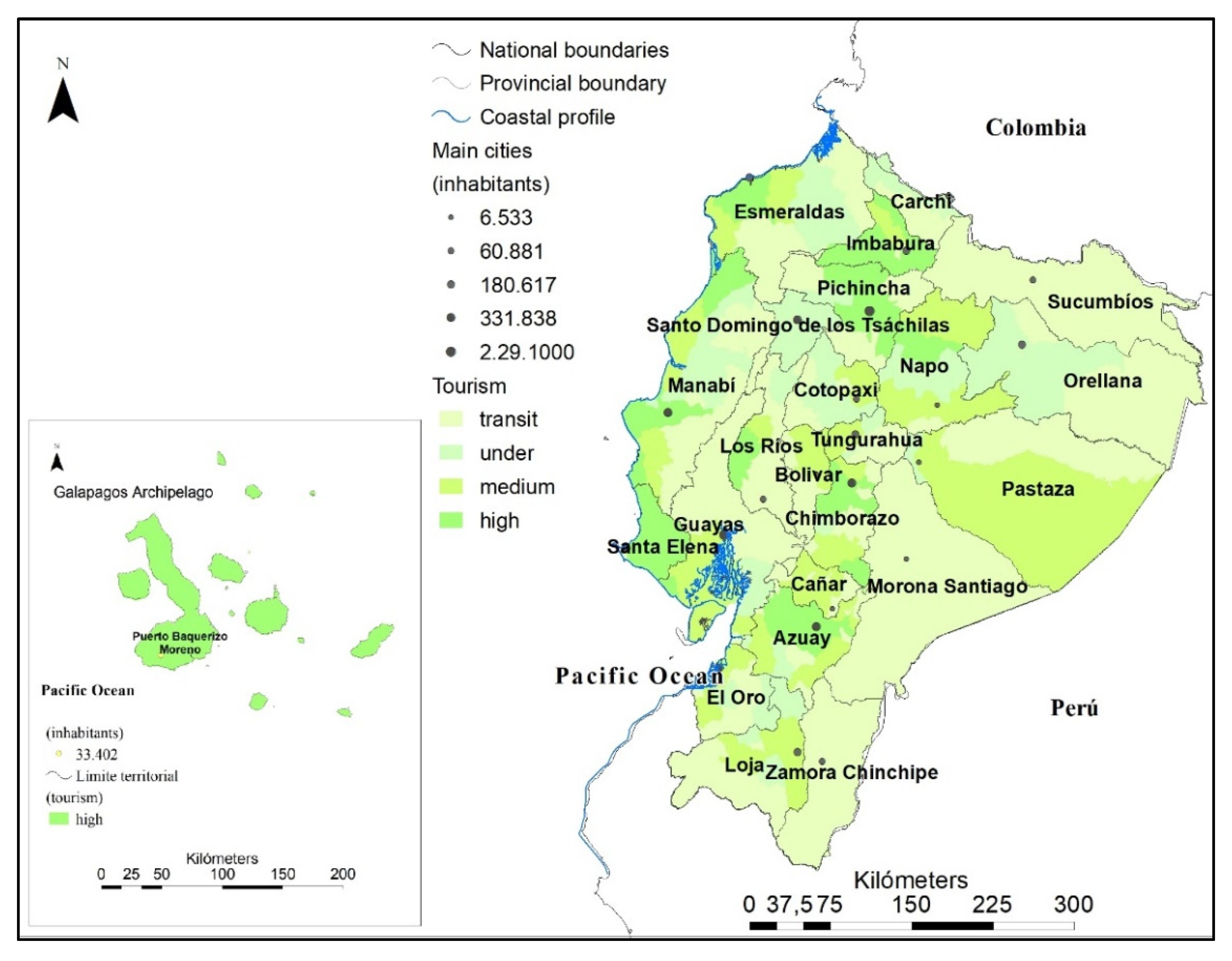

Figure 1 shows a choropleth map reflecting the concentration of tourism in Ecuador.

The tourism sector in Ecuador comprises 19,490 entities, of which 87.78% are micro-enterprises, 12.17% are small and medium enterprises and 0.05% are large tourism establishments and companies. There are 39 community-based tourism centers, representing 0.2% of the country’s tourism facilities. The provinces with the highest representation of tourism activity are Pichincha, Imbabura, Chimborazo, Azuay, Esmeralda, Manabí and Santa Elena.

Table 1 shows Ecuador’s community-based tourism establishments by province.

Methodologically, this study began from the paradigm of the deductive method and the problem was examined from its generality; the most general theories linked to tourism activity, especially community-based tourism, were analyzed. The premises and objectives of the study were identified in order to reach precise conclusions on the subject studied. Under the conditions of Ecuadorian society, community-based tourism constitutes a model that is destined to cover an important part of the tourism demand in the country, to become a significant economic activity based on the use of the communities’ indigenous resources, and to reduce the poverty and precariousness gap in the peripheral localities of the country’s major cities, especially in the semi-urban and rural areas.

Figure 2 shows a diagram of the research methodology.

The research was based on the deductive method that allowed us to appreciate the problem that arises in relation to the lack of a theoretical model capable of carrying out the pertinent evaluations associated with the community tourism model in Ecuador. The query of the general theories related to tourism management models, their theoretical structure, and evaluated aspects. This allowed us to define the hypothesis, allowed for the analysis of the variables, and enabled us to reach precise conclusions on the subject studied [

112].

The work is of an analytical, descriptive, and explanatory nature, which allowed for the analysis of the literature consulted to describe the proposal of the theoretical model of community tourism and explain its systemic structure in the framework of the interrelationships of the external and internal components with internal subsystems. This allowed us to integrate the contributions of the qualitative and quantitative analyses in the treatment and processing of the results of the interviews and discussions carried out with the actors of the Ecuadorian tourism sector, as well as the numerical data obtained from the results of the surveys of tourism experts. All this made it possible to delve into the phenomena linked to tourism, especially in the community modality, to achieve breadth and depth of meanings. It was also possible to contextualize community tourism in Ecuador to achieve a wealth of interpretations on the subject studied.

Among the techniques applied is the historical–logical analysis that allowed us to analyze tourism development in Ecuador from its beginning as an economic activity, and the emergence of community tourism as an alternative for less-favored communities. The analysis–synthesis was conducted to separate the relevant parts of the tourism management models and gain an in-depth understanding of the fundamental elements and relationships between them and synthetically recompose their composition as a whole in order to structure an integrated theoretical model. The result allowed the systematization of the models studied and the design of the theoretical model of community tourism that is proposed, with the graphic representation of the subsystems and their arguments. The systematic review of the literature and documents from primary sources allowed for the analysis of scientific articles, theses, books, and documents from primary sources related to the subject of study from their different conceptual denominations. The different definitions or terminologies related to community tourism and the models that try to explain it were considered. The selection of documents included a rigorous review of the related literature, with special attention paid to publications from 2018 to 2022. As an instrument, a documentary analysis guide was applied that included origins, concepts and definitions, characteristics, geographical distribution, segmentation and profiles of clients, leading countries worldwide and on the American continent, the new trends in community tourism, and the demands of clients in the new scenario due to the impact of COVID-19, as well as the current economic situation on a global scale.

The examination of the most general theories related to the theoretical model of community tourism required consulting the theories related to the types and modalities of tourism, supply, demand, superstructure, infrastructure, and the receiving community, as well as the innovative models that have been have been applied in order to improve tourism activity in recent years and especially those related to community tourism.

Several works were analyzed that from the theory are based on the tourist modalities and the types of tourism, among them the work of Menoya, theoretically based on the value chain approach applied to the integration of municipal and extra-municipal value chain systems to promote development [

113]. The work focuses on the analysis of the economic component, supply, demand, and the balance of both indicators.

Goffi’s work develops a set of indicators related to the different aspects of tourism competitiveness [

114]. Jafari’s work shows a systemic approach analysis focused on socio-cultural aspects with the aim of placing the visitor at the center of tourism activity, through the construction of a model made up of six components [

115]. In Franco’s work, 12 models of systemic approach are analyzed. In all of them you can see the interest shown by the study in the problem of tourism. The interest in economic aspects centered on supply–demand is appreciated, and in others the spatial organization prevails, but from a simplistic conception and in other cases they reflect a vision that transcends the central objective of the operation of tourism, with a turn towards positions that focus on the well-being of man and society with criteria of sustainability. However, the systemic element is only partially fulfilled [

87].

In the models analyzed, the analysis of governance is not appreciated, nor is the integration of an innovation model that fosters continuous improvement, forming part of a system of systemic internal interrelationships, where the host community of the environment, the demand, supply, and the balance of both indicators are together analyzed in a systemic context where a group of external components influence, such as: public–private partnerships, creativity, innovation, the influence of the regulatory framework, the environment, and competition, demonstrating challenges to the new demands of community rural tourism in the face of a changing world. In addition, among the external components of entry to the system, the particularities of the tourists that may come from national and international tourism and that in some cases do not present the same preferences must be analyzed, as well as the needs of information, material, and financial resources, as components such as external output, customer satisfaction, and the improvement of living conditions must be evaluated not only for the workers of the enterprise, but also for the surrounding community.

The different definitions or terminologies related to community-based tourism and the models that try to explain it were considered. Document selection included a rigorous review of the related literature, with special attention to publications from 2018 to 2022. For this purpose, a documentary analysis guide was applied that included origins, concepts and definitions, characteristics, geographical distribution, segmentation and customer profiles, prominent countries worldwide and in the American continent, new trends in community-based tourism, and customer demands in the new scenario from the impact of COVID-19, as well as the current economic situation on a global scale. The graphic structure, components and subsystems of the tourism models consulted and the systemic relationships between the subsystems were also analyzed, as well as the contributions considered in the description of the analysis during and after COVID-19. For modelling and the structural systemic approach, a dialectical character was assumed, and its strengths and weaknesses allowed it to be conceived in its prospective development.

Next, a structured survey was applied to a non-probabilistic sample of seven tourism experts, especially in the field of rural and community-based tourism, in order to obtain relevant information about the evaluation of the model and its contribution as a scientific result based on the system of indicators used for evaluation. For survey analysis, a Likert-type scale was applied to evaluate the theoretical model and each subsystem of the model as a whole using SPSS Statistics version 25.0 (IBM Corporation, Armonk, NY, USA).

For the structuring, validation, and application of mass tourism models, the criteria of proven experts in different fields of the business, especially in the economic, structural, insurance, security, and treatment fields of tourism, among others, are usually rigorously applied. However, community-based tourism is often considered to be a marginal issue within the sector, and this may justify the simplicity and lack of depth with which tourism management studies are carried out in certain models such as rural tourism, indigenous tourism, agro-tourism, and community-based tourism, among others. In reality, nothing could be further from the truth, as these tourism models, due to their characteristics, variety of products, economic and material limitations of investors in these types of ventures, and especially their environmental implications, require an unquestionable rigor and deployment of techniques and theoretical evaluations that must be carried out by specialists trained and experienced in the tourism function. This is even more important when it comes to the validation of a theoretical model.

The literature review revealed that the assessments made in the theoretical and management models of community-based tourism developed by several authors [

62,

71,

89] overlook the criteria for the selection and evaluation of the experts in charge of issuing the theoretical assessments related to the application of the model.

Since the second half of the 20th century, the implementation of qualitative methods of forecasting and testing has gained momentum. The importance of their application is greatest when there is a lack of clear data and useful information on which to base an analysis. One of the most widely used is the Delphi method, which uses a group of experts for analysis in the interest of minimizing the effects of social pressure and other aspects of small-group behaviour and that it is a specific method for the evaluation of experts developed from 1944 in the city of New York, United States, by researchers Olaf Helmer, Norman Dalkey and Nicholas Rescher [

116].

Experts can be internal or external specialists. There is no single structure for applying the Delphi method. Its general use requires it to be flexible in the interest of meeting the needs of the work in which a comparative analysis of the introduction and expansion of the new product is applied, basing the testing on patterns of similarity. The method does not require consensus, as its objective is to achieve a number of opinions that are reduced by the application of the method. The information obtained allows the product to be validated. From the research point of view, it is a systematic, formal, and rigorous process to verify the hypotheses on the subject under analysis, in this case the theoretical model of community-based tourism. Each scientific enquiry raises the challenge of proving the veracity of the research. Often the practice results in a safe method, but when it is a theoretical method, it is necessary to apply the criteria of experts to demonstrate the accuracy of the proposal made [

116].

The method based on expert judgement is based on the characteristics of the experts, i.e., their knowledge, research, experience, bibliographical studies, etc. It makes it possible for the experts to analyze the topic in good time, especially if there is no possibility for them to do so jointly. In most cases, their occupations make this impossible due to the levels of responsibility each of them holds, and the dispersion of their locations. This route is characterized by the fact that it allows for the analysis of a complex problem, giving independence and peace of mind to the participants, i.e., the experts. This process always begins by sending a model to the potential experts with a brief explanation of the objectives of the work and the results to be obtained [

116].

The method based on expert judgement is mainly used to verify the quality and effectiveness of theoretical research results and their social application, and to determine the impact of theoretical results when it is very difficult to measure by more precise methods based on practice.

Expert judgement is very important when there are no historical data to work with or the existing data are inaccurate, when forecasting the implementation of new technologies, when the impact of external factors has more influence on the evolution of the theoretical model than internal ones, when ethical, moral, cultural, and environmental considerations dominate over economic and technological ones in the evolutionary process of the venture, and when the research has an eminently theoretical approach, with the purpose of assessing the quality and effectiveness of the proposed model and testing the validity of the methodological procedures to be applied [

117,

118,

119]. It can be seen that there is a correspondence with the concrete conditions in which the research of the proposed theoretical model is carried out.

To select the non-probabilistic sample, a population of 11 experts was analyzed, of which 7 were selected. Inclusion criteria included specialists who demonstrated the highest values of competence (K); had proven prestige and professionalism recognized in society; had a working, teaching or practical relationship in rural and community-based tourism activity for 5 years or more; and were representative of the places from where they came. Those who expressed their agreement to participate in the study were also considered for inclusion, and those who did not consent to participate were excluded. From a gender perspective, the sample comprised four women and three men who provided their consent to participate in the study.

The assessment of expertise was established according to [

120], and for this purpose, the level of competence of the experts was determined using the coefficient k = ½(kc + ka), where kc represents a measure of the level of knowledge on the topic under investigation and ka a measure of the sources of argumentation. This method was developed by Pérez-Millan [

121] and modified according to Muñoz and Ríos [

122] in order to establish acceptance using values more than 0.8.

To identify and select experts, the number of experts was calculated using Equation (1):

where

M is number of experts,

i is the desired level of precision,

P is the estimated proportion of experts’ errors, and

K is a constant whose value is associated with the confidence level chosen.

The following values were considered: i = 0.10, P = 0.01 and K = 6.6564. Substituting the values in the expression showed that seven experts were needed.

The evaluation of the theoretical model considered the criteria of experts in terms of subsystems; the assessment of the model’s relevance; the criteria of validity with regard to feasibility, applicability, generalizability, sustainability and relevance; novelty and originality; and validity in terms of the model’s adaptation to the new demands of clients and their new profiles. The use criteria included systemic or integrative character, the ease of understanding and application, benefits for the actors involved, the inclusion of international standards, the usefulness of structural components, and flexibility in the face of socio-economic changes during and after COVID-19.

The following hypotheses were established to assess the correspondence of the experts’ criteria:

Hypothesis 0 (H0).R1 = R2 = … Rn. The average ranks of the experts’ assessments are similar to each other.

H1.At least one of the average ranks of the experts’ evaluations differs from the others.

Critical region: Asymptotic sigma ≤ 0.05 (5% significance).

Similarly, an analysis of the mean ranks was established to determine the differences of assessments in the aforementioned criteria, referring to subsystems, validity and usage criteria. This analysis was complemented with the determination of the medians per criterion to ratify the measures of central tendency of the criteria.

Equation (2) was used to determine the potential unsatisfied demand:

where

Dpi is the potential unmet demand,

D is the demand and

O is the supply.

To evaluate the proposed theoretical model of community-based tourism as a scientific result, the elements of analysis were determined by the experts using descriptive statistics in order to assess the subsystems, validity criteria, and use criteria, which are represented in tables and graphs. For this purpose, a validation instrument was designed to apply to the experts, which considered the aforementioned criteria for evaluation using a Likert scale, facilitating a higher level of precision, where 1 meant the highest degree of disagreement and 5 meant the highest correspondence between the aspects to be evaluated and the model as a whole.

The configured model of community-based tourism, as well as its theoretical and practical contribution, was presented reflecting its name; the objective justifying its creation; the theoretical and methodological premises supporting it; its rationale and justification based on social relevance; its methodological, theoretical, practical and economic values; and its ethical, environmental, and social responsibility implications. The social context in which the model was inserted, its graphical representation, component subsystems, use criteria, its qualities, forms of instrumentation, recommendations and alternatives were described.

All this allowed us to notice that there is a need to update the community tourism management model as a contribution to the scientific development of tourism, the systemic nature of its components from a new perspective of analysis that considers the need for changes as a development factor, and the incorporation of new patterns, improvement of old practices and acceptance of new customs, attitudes and ways of doing things as demands of the new type of post-COVID-19 tourism.

Limitations

Recognizing the limitations of the study carried out, far from detracting from the value of the research, represents greater validity and rigor to the work developed. Therefore, some particularities in this regard are indicated below [

123].

The fidelity and veracity of data and information constitutes one of the most common limitations in theoretical studies and this is given by the level of subjectivity that the actors of the investigation, among them, the experts, usually print when making their assessments, evaluations, opinions, and conclusions. Another limitation is related to the selection of the enterprise to carry out the study and the tourist season in which the research is carried out. No community tourism enterprise is identical to another; each one protects its peculiarities from the environment, the natural resources it possesses, the culture, customs, and community roots, which implies that the methodology may be the same, but it is required to deploy a deep vision to adapt the methodology from the peculiarity of the socio-economic and environmental relations that exist in each undertaking, in such a way that it enables obtaining the expected results. The tourist season is another aspect that must be considered. In the high season the demand is usually greater, especially from foreign tourists who arrive full of curiosity to experience the proposed offer.

The lack of information and its reliability is usually another of the frequent limitations in community tourism facilities. This may be motivated by other limitations such as weak governance and management control, which in some cases is associated with a lack of preparation and little knowledge on the part of the actors in the sector about tourism management.

Another limitation is related to the self-reported data that are produced from the information obtained during the interviews and focus groups carried out. These can be influenced by selective memory, the telescope effect, and exaggeration by representing results as more significant than they really were.

The lack of previous studies in the case of the work carried out constituted another limitation, however, it was possible to have a broad bibliographic base that allowed supporting the theoretical analysis of the model presented.

The analysis of the limitations allows us to warn that it would be a scientific error to estimate that the results of the study presented can determine a trend applicable to all community tourism ventures, although the methodology can be assumed as long as it is applied after a previous analysis process that allows for the adaptation to the demands of the work to the conditions of each undertaking [

124].

3. Results

After the experts were selected, a survey was conducted and information about the validation of the theoretical model of community-based tourism was processed, as well as the interrelationships between the model’s subsystems, validity, and use criteria. Evaluations were carried out using a Likert scale, where 1 meant the highest degree of disagreement and 5 the highest degree of agreement in the aspects to be evaluated in relation to the theoretical model and each subsystem of the model as a whole.

Table 2 shows the summary of the experts’ evaluation matrix for each subsystem and statistical results.

Figure 3 and

Figure 4 represent the mean and median ranges (all with maximum values) of the evaluations given by the experts to each subsystem.

Similarly,

Table 3 shows the results of the experts’ assessment of the model according to the validity criteria: feasibility, applicability, generalizability, sustainability, and relevance, validity, novelty, and originality.

Similar to the previous case,

Figure 5 and

Figure 6 show the mean and median ranges corresponding to the validity criteria of the model, showing the maximum value in all cases when using the median as a measure of central tendency.

Table 4 shows the experts’ ratings of the use criteria.

Similarly,

Figure 7 and

Figure 8 show the central tendency in favor of the maximum ratings for the use criteria of the model that show its usefulness, where the median again reaches the maximum value in all cases.

The following is a synthesis of the model that constitutes the fundamental result of the research:

Name of the model: theoretical model of community-based tourism

Objective justifying the creation of the model: to configure a theoretical model of community-based tourism as a proposal for change in order to respond to the new demands imposed by the current health, economic, and environmental scenarios and those of the foreseeable future based on community-based tourism trends and new demand profiles

With regard to theoretical and methodological premises, the model is based on its synergistic and holistic character by integrating its component subsystems in rural tourism in their dialectical relationship, which, when interacting, can generate a new and superior result from a qualitative and quantitative point of view.

From the structural point of view, the model is sufficiently dynamic and flexible to facilitate its adaptation to the processes of change in different scenarios. The intrinsic flexibility of the model allows it to assimilate the contributions of the tourism sector, as well as those of the tourism management systems and models that were consulted during the research.

The model considers the particularities of rural tourism in different countries and regions, with the possibility of being enriched through the assimilation of variables based on the emergence of new situations and social, economic, and environmental contingencies. It is easy to apply and interpret for the actors involved, such as researchers, academics, and organizations in the sector.

To achieve this, it is essential to understand and contextualize the Global Code of Ethics for Tourism applied to the community context, the Sustainable Development Goals set out in the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development, the principles of sustainable tourism set out by the World Tourism Organization, and the integration of the contributions of corporate social responsibility applied to these tourism scenarios [

125].

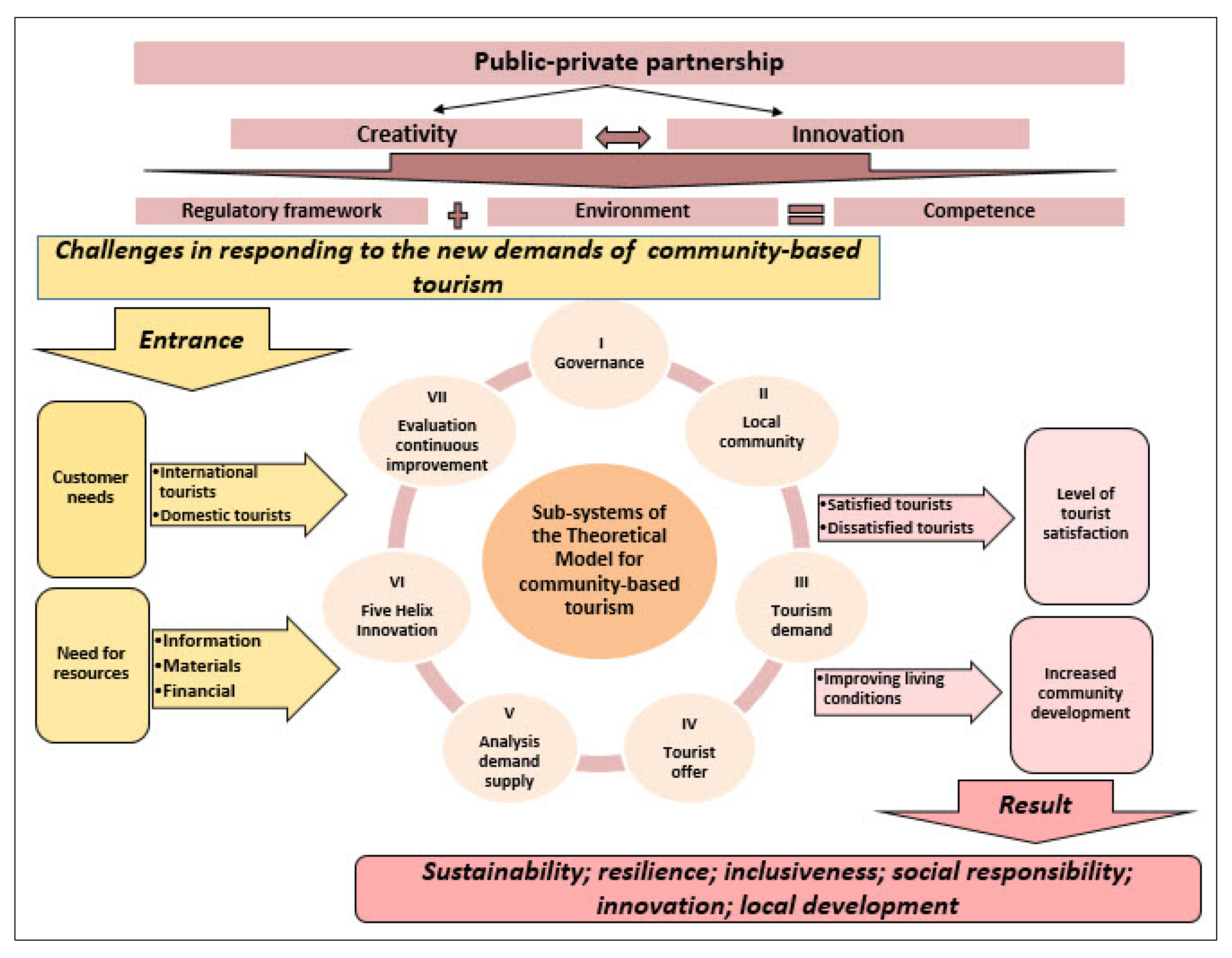

Figure 9 shows a graphical representation of the external and internal elements of the proposed community-based tourism model.

The internal systemic structure of the proposed theoretical model was developed from the study of community tourism and the management models consulted for this type of tourism. The structure of its external and internal components responds to a tourism undertaking where several of its own modalities, such as rural tourism, indigenous tourism, nature tourism, cultural and historical tourism, and some others that may be present in a cooperative and supportive manner, usually concur within the context of entrepreneurship. The difference is that they all come together jointly under idea, planning, execution, and management control to form a unique tourism product, with a unique offer due to its structural composition and its own characteristics. However, this does not mean that the proposed theoretical model is exclusive to community tourism; its intrinsic versatility is based on a flexible systemic structure designed for innovation and continuous improvement, which opens the possibility of its application to other tourism models, provided that the corresponding adjustments are made.

The structure of the theoretical model is revealed through its external and internal structural components that allow the study and interpretation of community-based tourism and its dialectical and systemic relationships.

The systemic and process approach of the model allows us to understand the interrelation and interdependence between its components. This is of vital importance for analyzing the different subsystems that make up rural community-based tourism and for planning strategic actions that guarantee the necessary synergy and decision-making by the different actors.

The novelty of the model lies in its differentiation from the models analyzed, and in its theoretical–methodological foundation based on the integral analysis of sustainability, inclusion, resilience, social responsibility, innovation, and local development as new elements of analysis that are provided with the intention of contributing to the development of science.

It is very important to understand how the external elements or components present in the current environment are characterized by permanent change and instability, which can have an impact on the internal components of the model.

In the external components, the variables that affect the development of community tourism are valued: public–private partnerships, creativity, innovation, the regulatory or legal framework, competition, the needs and expectations of customers, and the needs for information, material and financial resources, as well as the interaction of the whole and its parts that influence the output elements, where the level of satisfaction of tourists and the community development achieved from the achievement of participatory, inclusive, and sustainable governance is fundamental.

In most mass tourism projects, the external components are evaluated and taken into account with the same importance as the internal components of the system. Within this, the public–private partnership plays a key role in assessing and securing funding, as well as other equally important assurances regarding the infrastructure and equipment available through the provision of services such as electricity, water, communications, and other elements such as security and the promotion of the tourism product.

As in the case of mass tourism, public–private partnerships are of the utmost importance for community-based tourism, and should be carefully and thoroughly evaluated. It is assumed that external elements have a permanent influence on the functioning of the system. In this sense, public–private partnerships are a special condition that can influence the dynamism of systemic relations. Without this it is very difficult to achieve a context that allows for creativity, innovation, and social responsibility as a process of continuous improvement.

The legal framework as an expression of the state’s will for the development of community-based tourism can affect the establishment of fair relations in terms of the use of the riches and opportunities offered by the environment and the adequate management of competition with other forms of tourism. A fair organizational and operational climate must be guaranteed without the practice of discriminatory habits that could affect the development of relations and activities that derive from the community modality.

The existence of a regulatory framework that fairly considers the performance of community-based tourism and grants security of rights to the entrepreneurs is a condition that guarantees the harmonious development of the system and the relations with the socio-economic context for the realization of tourism activities.

The relationship between community-based tourism and the socio-environmental environment is another important external element that needs to be carefully and thoroughly evaluated. It is assumed that the relationship between tourism activity in the community context enables the stimulation of commercial activity and the emergence of products that are attractive to visitors. At the same time, this generates a management based on endogenism as an expression of the cultural values and customs of the community, all within the framework of a local will to respect and care for the environment.

The combination of a well-articulated regulatory framework that favors the development of community-based tourism, with the socio-environmental setting, can give the project a competitive level that allows it to be sustained over time, and the innovative will to face the challenges that arise from the changing environment and future transformations.

The study and integral evaluation of the external components constitutes a novelty for the theoretical model of community-based tourism. The review of the bibliography consulted made it clear that in other models developed in this respect, the study of these elements was not carried out with the depth and importance relevant to the case. The studies have been carried out partially and in some cases superficially.

Other external components that must be adequately evaluated in the theoretical model are the input and output elements. It is assumed that without a fair assessment of customer requirements and material resource needs, it is a major risk to carry out a community-based tourism venture. The origin of potential tourists should be analyzed. As a general rule, foreign visitors have requirements that in some cases differ from national tourism. It is necessary to analyze to what extent the existing material resources and others that need to be incorporated, as well as the natural potential of the place, can satisfy these requirements, in order to leave a positive mark on the satisfaction of the clients.

In the resource requirements, information, material, and financial resources must be specified and quantified. It is assumed that the availability of resources for the community-based tourism enterprise is an irreplaceable input component without which it would not be possible to start a tourism business. The likely source of these resources must be clearly identified, provided that the first consideration is the availability of indigenous resources that can meet the proposed needs.

The valuations of the output elements constitute an important part of the external components of the theoretical model of community-based tourism, which should be assessed as accurately as possible. It can be assumed that the output elements are an indicator of the viability of the venture.

It has to be assessed whether the conditions foreseen for the venture provide tourists with a sense of satisfaction with the service received. In doing so, the relationship between the price and the services provided to the tourists should be analyzed. Another issue to be assessed is related to community development. The possible improvement of the living conditions of not only the people involved in the venture, but also the social context of the place where the venture takes place, plays an essential role. Community-based tourism should represent the opening of new jobs, new sources of income for the community, and thus the improvement of living conditions in the community environment.

The evaluation of the internal components of the model is conceived as a system of processes that includes the establishment of challenges to respond to new trends in community-based tourism in a complex health and economic context. For this purpose, seven interrelated subsystems were theoretically analyzed with sufficient flexibility. This is based on the premise that the procedural structure of the system guarantees a high quality tourism service that allows for assimilating the necessary changes and adjustments aimed at continuous improvement in a proactive scenario that responds to a strategic idea that strengthens resilience and local development.

Subsystem I guarantees the vitality of participatory community governance and constitutes the superstructure for the development of community-based tourism. To this end, the contributions and considerations of the Plurinational Federation of Community Tourism of Ecuador [

31], formed by indigenous communities from all over the country that offer tourism, guiding, and accommodation services, were considered. These are indigenous, Afro-Ecuadorian, peasant and Montubio (mestizo) communities, and genuine representatives of indigenous cultural traditions and natural heritage. This subsystem considers the objectives, areas of work, structure, possible adjustments and changes over time, the context of each place, and the concrete situation of the moment.

In this case, governance is expressed as a permanent way to strengthen integrated local development and achieve effectiveness in citizen participation in decision making as public policy, convenient to innovate and share knowledge and experiences as ways to generate new knowledge and experiences from the community. It considers the processes of good governance in a broad sense (its legal, political and institutional frameworks) as a strategy for sustainable economic and social development, with sufficient flexibility to operate the organizational and structural transformations that are necessary in correspondence with the dynamics of tourism demand and supply.