1. Introduction

Typhoons are the most prevalent natural disaster in the Philippines. Due to its geographical location, the Philippines is prone to tropical cyclones, which typically bring torrential rainfall and floods of vast areas and high winds, resulting in significant human casualties and agricultural and property destruction. As a result, having sufficient knowledge about such typhoon occurrences for practical reasons is critical [

1]. Typhoons can strike the Philippines at any time of the year.

Mostly, typhoons occur between June and September, wherein the month of August is usually predicted to have the greatest number of typhoon occurrences. Chen et al. [

2] expounded on tropical cyclones in both South and Eastern Asian inland regions. Their study covered the past and future impacts of super typhoons on climate effects. The study analyzed data from 1979 comparing it to 2016. It was seen that longer sustained times from 2 to 9 h was evident with a penetration of 30 to 190 kph inland effect brought by super typhoons. After the analysis, their study justified the future disaster brought by typhoons, especially in East and Southern Asian countries. Similarly, the study of Jiansheng et al. [

3] presented the evolution of the super typhoon and its characteristics, focusing on the main functional area of China. They showed that from 1991 to 2010, an upward trend in typhoon risks was evident. Their study suggested starting to create mitigation plans for low and medium-risk areas as future typhoon-related events were predicted to affect the said areas. In addition, Lorenzo and Kinzig [

4] generalized how meteorological typhoons are evidently increasing in Southeast Asian countries. Developing countries such as the Philippines were suggested to consider mitigation plans since evident typhoon disasters are consistent [

5]. Around 20 tropical cyclones hit the Philippine area of responsibility each year. Ten cyclones are generally projected to be typhoons in a year, five of them potentially devastating [

6]. The Haiphong typhoon was the deadliest tropical cyclone to impact the Philippines, killing up to 20,000 people in September 1881. In addition, Typhoon Yolanda (international name Haiyan) became the strongest landfalling tropical cyclone on record as it hit the Visayas in the central Philippines on 7–8 November 2013. It is considered the deadliest storm in contemporary meteorological records [

7].

Typhoon Rai (202122), also known as Typhoon Odette in the Philippines, was a devastating tropical cyclone that distraught the country in December 2021 (see

Figure 1). It was the third category 5 super typhoon following Pamela in 1954 and Rammasun in 2014. Moreover, Typhoon Rai (202122) was the 15th storm to hit the country in 2021. Before leaving the Philippine area of responsibility on 17th December, it made landfall in the Surigao del Norte and Dinagat Islands provinces in Mindanao, five provinces in the Visayas, and the island of Palawan in Luzon [

8]. Thirteen (13) million people in the Philippines were estimated to be affected by Typhoon Rai (202122), harming a number of government and private buildings [

9]. At least 1259 people have been injured, 80 are still missing, and 410 have died, the majority being from the island of Bohol, which has been severely damaged. Damages in the stated region were valued at PHP 5 billion (USD 88 million), PHP 20 billion (USD 352 million) in Siargao, and PHP 5.9 billion PhP (USD 104 million) in Negros Occidental.

Because the Philippines is prone to typhoons and other catastrophes, disaster preparedness and disaster risk reduction measures will remain critical to the Filipino people’s resilience. Investing and promoting disaster preparedness has been proven to save economic losses on relief and rehabilitation costs. Thus, both the government and the private sectors have increased their focus on disaster preparedness and prevention, resulting in fewer casualties [

11].

Disaster preparedness is a set of steps taken to guarantee that the resources needed for a successful response are accessible before a disaster happens or that the resources can be accessed quickly when disaster strikes [

12]. According to Moe and Pathranarakul [

13], the number of people killed in a disaster can be effectively minimized if preparation is done before the crisis occurs. However, most people pay little attention to disaster planning and are unaware of its importance until it happens. Because of this, the goal of disaster risk reduction is to modify human habits. This requires using appropriate methods to urge individuals to change their behaviors to lower the risks and improve their ability to respond to disaster effects [

14]. In typhoon preparation, beliefs about the extent to which preparations and adaptation are necessary to avoid the risk and hazards of a typhoon are critical [

15,

16]. Since typhoons are frequent in the Philippines, it is crucial to limit the dangers and threats they provide. Thus, future research on policy development should focus on improving the community’s typhoon preparedness and disaster risk literacy [

16].

Several theoretical models of protective behavior have been developed to explain the relationship between behavioral factors and disaster risk reduction, one of which is the Theory of Planned Behavior (TPB). According to the TPB, three core components shape an individual’s behavioral intentions: attitude, subjective norms, and perceived behavioral control [

17]. However, the difficulty in conceptualizing and capturing an individual’s attitudes is a challenge in TPB measurement, which is a crucial factor during a disaster [

18]. Protection Motivation Theory (PMT) is another model utilized to define individuals’ responses to perceived threats and uses threat and coping appraisal as opportunities for motivational protection during a disaster [

19]. However, the model does not consider all the environmental and cognitive variables, such as the influence of social norms that may influence the adaptive behavior of individuals during disasters [

20]. Another model used to predict individuals’ behavior to carry out an action relating to a threat such as a disaster is the Social Cognition Theory (SCT). This model considers the distinctive way individuals acquire and maintain behavior and the social environment in which individuals perform the behavior during a disaster [

21]. It is assumed in this model that factors such as a person’s cognitive, affective, and physiological characteristics and behavioral patterns and environmental events interact and influence one another. According to Lee and Lemyre [

22], people’s motivation to prepare in the context of disaster preparedness is a function of their cognitive and affective reactions to a natural hazard. However, other than through reference to previous experience, SCT theory does not focus on emotion or motivation. As a result, these factors receive little attention in assessing natural disaster-related studies.

Various behavioral theories have been established as a strategic basis for supporting the adoption of disaster preparedness measures. However, most models focused only on cognitive and psychological factors for the adaptive behavior of individuals in a disaster. In a substantial disaster situation, a thorough assessment of the human factors and ergonomic issues affecting disaster management is critical to ensuring an effective response during a disaster. Thus, further research on disaster preparedness using ergonomic domains such as physical, cognitive, and macro-ergonomics is highly required.

With a focus on disaster preparedness, ergonomics can help at the system, organizational, community, and individual levels. Ergonomics provides analytical tools and strategies for identifying aspects of resilient performance and successful disaster-related adaptations [

23]. Recent research has also demonstrated the value of ergonomics methodologies in enabling proactive risk assessment and improving response preparedness. Gurses et al. [

24] evaluated numerous system aspects to discover failure modes and hazards connected to tasks, physical environments, and tools and technologies to identify ambiguous guidelines, protocols, and processes during disaster ergonomics.

Ergonomics considers a work system design’s physical, cognitive, and macro-ergonomic aspects. Physical ergonomics is concerned with injury prevention through workplace design and evaluation. It studies how people’s bodies engage with the devices they use daily. Human performance within a system is the focus of cognitive ergonomics. It investigates the ability of the mind to process and relate to information. On the other hand, macro-ergonomics focuses on designing organization-system interactions by imparting the required knowledge and procedures for improving work systems.

By addressing the interconnectedness of interpersonal, technological, and environmental elements and the potential impacts on all parts of the system of work design changes, ergonomics contributes to the establishment of a safe and sustainable work system. Since hazards interact with physical, social, economic, and environmental vulnerabilities to create these risks, the role of ergonomics in disaster preparedness is thus vital.

Furthermore, effective disaster preparedness techniques require a thorough understanding of the public’s awareness of natural disaster hazards [

25,

26]. In recent years, many studies have placed greater attention on the public’s natural disaster awareness and risk perception [

27]. In disaster preparedness and response, governments, organizations, community groups, and people must have the information, actions, and competencies to predict successfully, take action, and recover from possible, impending, or existing hazards events and situations [

28].

Several studies have identified the role of ergonomics in disaster preparedness. In the U.S., Sasangohar et al. [

23] studied the issues relevant to human factors and ergonomics in disaster management. However, the study focuses on the disaster management challenges during the COVID-19 pandemic response and recovery, which differs from other kinds of disasters. In Australia, Horberry et al. [

29] presented related studies in mining emergency management, highlighting the contributions of human factors and ergonomics to help create a safe and efficient mining disaster management system. However, the study only investigated the challenges associated with underground coal mining emergencies. In London, an ergonomic evaluation of disaster management had been studied but only considered the area of offshore oil platforms. Four main areas of ergonomics were identified in response to disaster preparation and management, including safety management, interface design, training, and human behavior [

30].

Despite the numerous available studies related to disaster response effectiveness, there has been limited academic research about the role of ergonomics and their domains in disaster preparedness during a typhoon. Thus, the purpose of the present study was to investigate the factors influencing the perceived preparedness of Filipinos for Typhoon Rai (202122) using a novel framework of ergonomic domains and disaster knowledge. Using the findings of this study, future academicians and disaster planners may look into how ergonomics can help develop disaster preparedness systems that enhance resilience by increasing emergency management knowledge, strengthening community coordination and communication, reducing occupational hazards, and improving processes to improve response efficiency and effectiveness. In addition, the model developed in the present study can also be applied as a theoretical framework for evaluating similar ergonomic-based natural disaster responses.

2. Conceptual Framework

This paper looked into the relationship of ergonomic factors with perceived preparedness for disaster, particularly typhoons. Addressing the interconnectedness of ergonomics’ physical, cognitive, and macro-ergonomic aspects during disaster response contributes to establishing disaster preparedness systems.

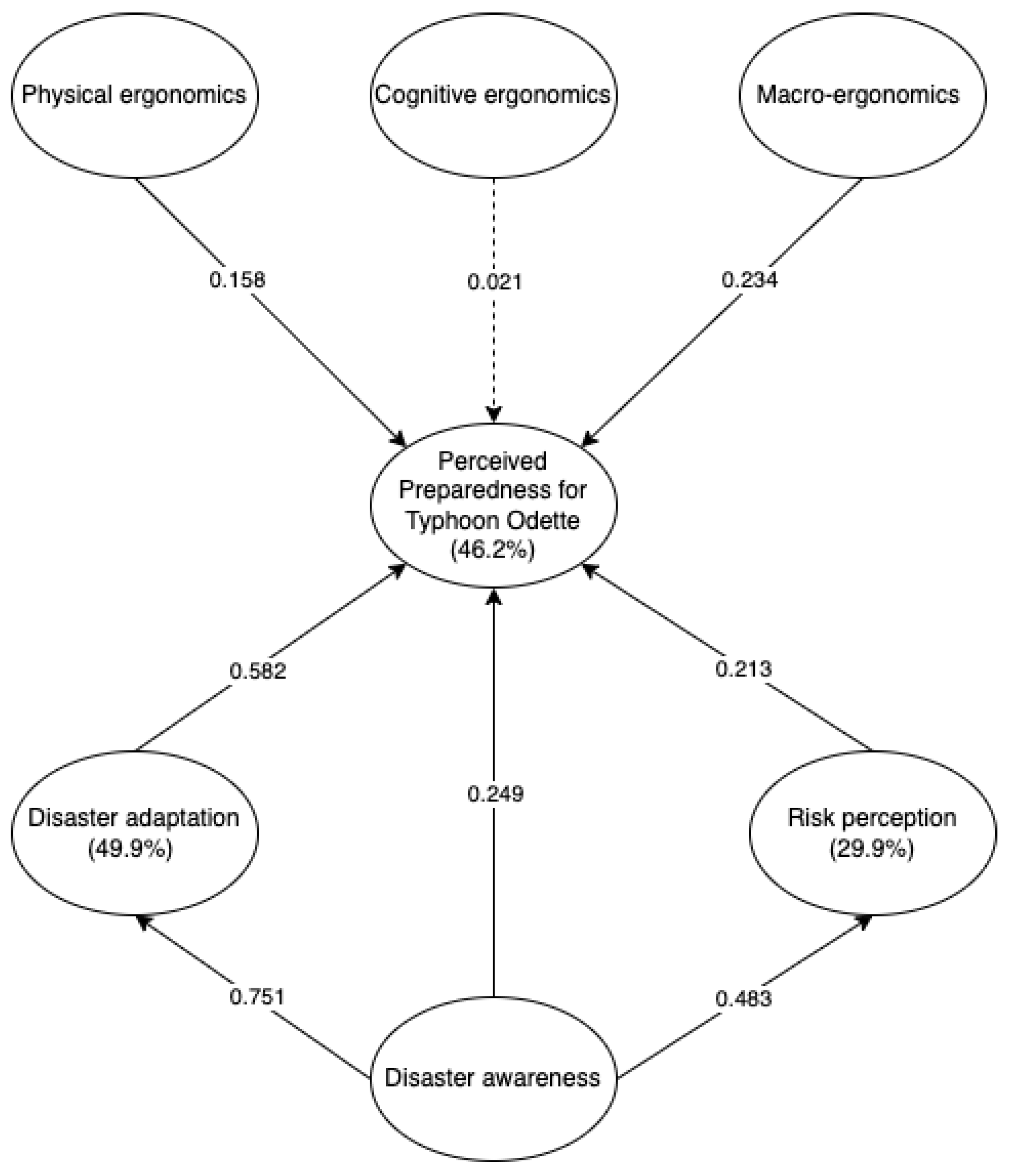

Figure 2 shows the theoretical framework of this study to measure the perceived preparedness for typhoons.

Previous research has looked into ergonomics to address disaster management concerns. In Bangladesh, physical ergonomics’ role in designing the physical structure and structural support of shelters during cyclones was investigated [

31]. The study showed that poor design of shelter infrastructure posed additional challenges during disaster operations and aggravated the persons’ distress during the calamity [

31]. In Colombia, a similar study proved the significant role of public infrastructure serving as a temporary shelter during disasters in the coping strategies of communities in vulnerable cities during natural calamities [

32]. In prior research, cognitive ergonomics’ role in individuals’ psychological and mental conditions during disasters was also discussed. A study by Zulch [

33] stated that individuals need to be mentally prepared to reduce their psychological distress during disasters to manage disaster preparedness and implement disaster warning situations successfully. Mishra and Suar [

34] have also proved that social anxiety during calamities reduced flood preparedness in India, with disaster education and resources acting as partial mediators.

Moreover, macro-ergonomics’ roles in organizations responsible for disaster management, like local government units (LGUs), play an essential role in disaster response and preparedness [

35]. Lower typhoon mortality is connected to the effectiveness of the government’s response [

36]. When catastrophe risk reduction techniques have positive outputs, it directly impacts their success. Thus, the ability of the local community to respond to disaster preparedness is deemed crucial [

37].

On the other hand, disaster risk reduction knowledge of natural hazards is essential for developing and implementing adequate disaster management practices. Several researchers have looked into the impact of disaster knowledge on preparedness in terms of awareness, adaptation, and risk perception. In a study by Tuladhar et al. [

38], the local Nepalese people’s disaster risk reduction (DRR) knowledge was evaluated to determine the readiness and adaptation of people for natural disasters. The study revealed a low level of disaster preparedness of local people, as measured by their inability to identify and address the perceived risk of disaster, adaptation, and awareness. The study found that disaster risk reduction education initiatives are insufficient, and there are gaps in disseminating disaster knowledge in Nepal. Hence, the findings will help government agencies in Nepal modify their disaster programs and management for local communities [

38].

In the Philippines, a similar study was conducted to measure the impact of disaster education knowledge on Grade 11 students to strengthen students’ resiliency toward natural calamities [

39]. According to the study, incorporating disaster readiness and risk reduction (DRRD) as a core subject for senior high school in the K-12 basic education curriculum helped students exhibit a high degree of disaster-related knowledge. Through this course, the students acquired awareness of disaster preparation, adaptation, readiness, and risk perception, thus aiding them to lead in disaster readiness activities and promoting greater consciousness about disaster risk reduction in their respective communities [

39].

2.1. Determinants of Perceived Preparedness for Typhoon Based on Ergonomic Domains

Physical ergonomics (PE) refers to people’s physiological interactions and activities. Improvements are sought in the physical design of the work environment that aids in the safety movements of people, workstation arrangement, safety protocols, and overall health. According to studies, shelters’ infrastructure and physical layout play a key function in large-scale disasters and perform a critical component of disaster response and management [

40,

41]. Similarly, the physical design of disaster evacuation centers in the community can aid in preparing individuals for disaster [

42,

43] and play a vital role in the community’s resilience during a disaster [

31]. A disaster evacuation shelter’s physical layout and infrastructure should be considered to preserve critical public safety as best as feasible. Adequate shelter, according to the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees [

44], has a significant impact on the survival of people in the early phases of a disaster. Thus, it is hypothesized that:

Hypothesis 1 (H1) Physical ergonomics (PE) has a significant positive effect on perceived preparedness (PP) for a typhoon.

Cognitive ergonomics (CE) refers to mental and psychological aspects that may affect interactions among humans and other system elements. According to Malkina-Pykh and Pykh [

45], psychological preparedness and cognitive awareness during disasters have assumed compelling importance for coping with emotional responses. A study by Tepstra [

46] also proved that their cognitive and emotional mechanisms significantly influence the preparedness intention of people for disasters. Lindell and Prater [

47] also showed that the psychosocial effects of disaster hazards could result in greater preparedness and intrusiveness of individuals, especially for communities in high-risk areas. Thus, it is hypothesized that:

Hypothesis 2 (H2) Cognitive ergonomics (CE) has a significant positive effect on perceived preparedness (PP) for a typhoon.

Macro-ergonomics (ME) refers to optimizing socio-technical systems, including organizational structures, policies, and processes. Hossain [

48] stated that when disaster affected people, a requirement for immediate assistance before and during the emergency response to a disaster was needed. An organization can play a critical role in overcoming its constraints in a well-organized manner. Organizations such as LGUs have a significant role in establishing emergency support during disaster emergencies [

49,

50]. The various initiatives of LGUs to support typhoon disaster-affected individuals are crucial in community preparation planning and can improve community readiness and lessen the effect of disaster. Thus, it is hypothesized that:

Hypothesis 3 (H3) Macro-ergonomics (CE) has a significant positive effect on perceived preparedness (PP) for a typhoon.

2.2. Determinants of Perceived Preparedness for Typhoon Based on Disaster-Knowledge Indicators

Disaster adaptation refers to absorbing, preparing, and recovering from disaster impacts. In most cases, adaptation is a proactive response to expected hazards to mitigate potential adverse effects or dangers ahead of time [

51]. According to IPCC [

52], in sustainable development, taking a longer-term view enhances the possibility that more urgent adaptation measures will strengthen future disaster response preparation. The adjustments in human behavior in response to disasters can mitigate the risks and hazards of natural disasters such as typhoons [

53]. Disaster adaptation will also allow a system to reduce the risk associated with these hazards by reducing social vulnerability [

54]. The socio-economic and demographic factors that influence community resilience are referred to as social vulnerability. According to studies, the socially vulnerable are more likely to be harmed during disasters. Moreover, a study by Mishra and Mazumdar [

55] proved that psychological adaptation to disasters could influence the preparedness and coping of an individual to disaster. Thus, it is hypothesized that:

Hypothesis 4 (H4) Disaster adaptation (AD) has a significant positive effect on perceived preparedness (PP) for a typhoon.

Risk perception refers to an individual’s subjective assessment of the possibility of unfavorable disaster consequences and impact. According to numerous studies, risk perception significantly impacts disaster preparedness [

56,

57,

58]. Demuth et al. [

59] and Xu et al. [

60] have proved that risk perception in households significantly impacted their behavior, such as relocation and disaster preparedness. When they sense a disaster is imminent, families make appropriate behavioral decisions. This finding is also supported by a study by Miceli et al. [

57] that showed people in a community with a higher perceived risk for disaster have increased disaster preparation and supported the adoption of specified protective behaviors. Thus, it is hypothesized that:

Hypothesis 5 (H5) Risk perception (RP) has a significant positive effect on preparedness (PP) for a typhoon.

Disaster awareness (DA) refers to the degree of catastrophe risk awareness and the causes that lead to disasters. Awareness of a disaster is vital in adequately implementing mitigation and disaster preparedness stages [

61]. According to Jennings-Sanders [

62], a disaster education program can help individuals and populations affected by disasters achieve positive outcomes. These may result in reduced death rates, improved health status, and lower disaster-related expenses. A study by Tanaka [

63] also proved that disaster awareness serves as educational information that aids in the strengthening of adaptation to social activities and academic sources. Various sorts of disaster education freely offered to the general population in easily accessible locations help adapt individuals for a disaster. Furthermore, a study by Rana and Routray [

64] also recognized that awareness and knowledge about disasters could significantly influence the degree of vulnerability and risk of disaster hazard that is essential for the successful implementation of preparedness initiatives. Thus, it is hypothesized that:

Hypothesis 6 (H6) Disaster awareness (AW) has a significant positive effect on disaster adaptation (AD).

Hypothesis 7 (H7) Disaster awareness (AW) has a significant positive effect on risk perception (RP).

Hypothesis 8 (H8) Disaster awareness (AW) has a significant positive effect on perceived preparedness (PP) for a typhoon.

5. Discussion

This study investigated the role of physical, cognitive, and macro-ergonomics and risk perception, adaptation, and awareness related to the disaster, which will help prepare for Typhoon Rai (202122). Partial least squares structural equation modeling (PLS-SEM) was utilized to determine factors affecting the perceived preparedness of Filipinos. In addition, machine learning using ANN was also utilized to verify and highlight the significant latent variables in the study. It was indicated from the result that AD was the most significant factor affecting perceived preparedness for Typhoon Rai (202122), followed by AW, ME, RP, PE, and CE as relatively significant.

From the results, it could be seen that disaster adaptation (AD) has the highest significant and direct effect on perceived preparedness (β = 0.582,

p ≤ 0.001) with a 100 score of importance from ANN. According to Howe [

113], individuals and households in the affected area’s adaptability to natural disasters will play a role in determining communities’ ability to recover after a catastrophic calamity such as a typhoon. The result of the study is supported by the findings of Mavhura et al. [

114], which proved that the government’s institutional capacity for disaster preparedness significantly influences the community’s survival strategy against disasters. According to UNISDR [

87], public and private investment in disaster risk prevention and reduction through structural and non-structural measures are essential to enhance community resilience and adaptability. Previous studies proved that government measures play a pivotal role in disaster adaptation and preparedness. Examples of these measures include the following: implementation of early recovery and rehabilitation interventions and early-stage reconstruction activities [

115]; providing early warnings and information about evacuation orders before the typhoon [

116]; and providing financial assistance to augment the resources of affected families for their acquisition of shelter materials and providing relief assistance and essential services to the disaster-stricken areas [

117]. As the primary subject of disaster management, the government must take the lead in the emergency management process.

In addition, risk strategies should also be implemented based on specific components that predict community preparedness, especially in highly vulnerable communities, to improve overall community resilience. The need for efficient disaster management and adaptation techniques in these vulnerable communities is increasingly pressing. Hence, to be fully supported by the government and other agencies involved in disaster risk management, an adequately resourced regional strategy must be executed at the community level. According to UNISDR [

53], floods can be reduced during a typhoon by monitoring and assessing rainfall intensity hourly, especially in places where the construction of houses or roads has hampered natural drainage without sufficient bridges. Then, a complete map of the community’s drainage can be constructed to restore natural drainage and build structural and design methods for increasing streams, extending bridges and using natural soil infiltration approaches. Furthermore, initiatives could include flood monitoring and control advancements and social support for affected households. With this, LGUs can prepare for disasters by decreasing and controlling the elements contributing to disasters at the community level.

Disaster awareness (AW) was also proved to have a significant positive effect on perceived preparedness for typhoons (β = 0.249,

p ≤ 0.001). AW was the second most important factor for ANN, with 96.60%. Shi et al. [

25] and Burningham et al. [

26] found that awareness of the dangers of natural disasters can considerably improve an individual’s self-efficacy and ability to take preventive activities, confirming this finding. In a study by Gumasing et al. [

118], it was mentioned that people would be able to recognize the procedures that must be followed during a typhoon and grasp the preventive steps to take in unforeseen calamities such as a typhoon if they are aware of the typhoon’s potential hazard. According to Guo et al. [

119], one way to increase community awareness of natural disasters is to provide more information-seeking channels such as social media for residents during calamities. Because of their easy access and availability for social connectedness and interaction, social media has been a preferred source of information among Filipinos. It can quickly disseminate information about natural disasters, resulting in affective outcomes [

120]. In this study, disaster awareness was found to be a significant factor in disaster preparedness since most of the study’s respondents are the younger generation (21–40 years old), who make up the largest population of social media users in the country. According to the Federal Emergency Management Agency [

121], during natural disasters, people use social media for various reasons, including checking in on family and friends, seeking support, gathering information about the scope of the disaster, and providing ground-zero first-hand accounts. Hence, social media can play a significant role in emergency response and management during natural calamities [

122].

Moreover, disaster education strives to improve individuals’ resiliency by strengthening disaster knowledge, building skills for preparing, adapting, mitigating, and responding to disaster’s detrimental consequences, and increasing public awareness of disaster risk mitigation methods that broaden the breadth of understanding. In the Philippines, disaster risk reduction management (DRRM) was incorporated into the curriculum for primary education to promote and strengthen the students’ culture of awareness, preparedness, and resiliency for disasters. According to Apronti et al. [

123], students are the most vulnerable victims of disasters, as hazards can have a negative impact on their physical, emotional, and mental health. By integrating DRRM into the curriculum, students have acquired some disaster-related concepts and ideas. These have made them well-prepared, adaptive, and mindful of the risks posed by natural disasters. As such, it was proved in the study that disaster awareness played a significant role in disaster preparedness since most of the study’s respondents are the younger generation who have taken DRRM in their curriculum. With this, instructional intervention successfully achieved significant changes in students’ knowledge of disaster preparedness, as evidenced by improvements and changes in their attitudes toward disaster. Hence, disaster education is essential for successfully implementing disaster risk reduction strategies [

38].

Subsequently, disaster awareness was also proven to positively influence risk perception (β = 0.483,

p ≤ 0.001). Based on a disaster’s perceived risk and impact, natural disaster knowledge and awareness were favorably connected with residents’ coping and responding behavior, similar to the findings of Jiang et al. [

124] and Jiang et al. [

125]. It was also suggested by Sattar et al. [

126] that the individuals’ perceptions of disaster risk, particularly in highly vulnerable locations, must be enhanced for them to make accurate judgments about natural disaster dangers. Individual risk perceptions must be formed to ensure a public response and effective protective action. Since most of the respondents of the study lived in the Visayas and Mindanao regions, which are considerably vulnerable to typhoons, it was found that they are more susceptible to experiencing threats brought by natural disasters due to their location, thus contributing to an increase in risk perception. In addition to being one of the most disaster-prone countries, the Philippines is subjected to numerous severe tropical cyclones and storms each year. Thus, disaster risk reduction measures should be integrated into climate change adaptation plans, development, and poverty reduction programs.

Furthermore, disaster awareness was also proved to significantly influence disaster adaptation (β = 0.751,

p ≤ 0.001). This finding is supported by the study by Tanaka [

63], which found that disaster awareness can be used as academic knowledge to help people adapt to disaster risk measures and motivate people to undertake protective behaviors during disasters. It could be inferred that since Filipinos are highly susceptible to natural disasters such as typhoons [

20], their knowledge and awareness about disasters is high due to constant typhoon experience, thus resulting in high disaster adaptation [

127]. In relation to a study by Tanaka [

63], awareness of disasters, community knowledge, and previous experience serve as educational resources that aid disaster preparedness and adaptation. According to Bronfman et al. [

127], individuals aged 30–44 years old are better prepared for flood-related disasters. This is because young people, according to studies, have a better ability to deal with a disaster situation practically and mentally [

128,

129]. When the demographics of this study are compared, it can be seen that the majority of the respondents (65%) are between the ages of 21 and 40. This demonstrates how respondents are more likely to have disaster adaptation due to their awareness.

Macro-ergonomics was also proved to significantly influence perceived preparedness (β = 0.234,

p < 0.001). This was indicated to be the third most significant factor, with a score of importance of 79.50% in the ANN. In a study by DeYoung and Peters [

130], it was found that disaster preparedness relates to confidence in the government in most populations. In understanding the challenges of predicting preparedness behaviors, the role of trust in the government in disaster situations remains critical. The role of government organizations and local actors during disasters plays a significant role in effective emergency preparations. These agencies play an important part in disaster preparedness by providing sufficient funds for key actors and reducing the demand for resources during the disaster response stage. Local governments and authorities must recognize their critical role in disaster management and the necessary skills and preparation to give support during the disaster response. Because the most effective disaster management occurs at the grassroots level, investments in local NGOs, civil society organizations, and community-based organizations are essential. They are frequently more capable of responding during disasters if given the resources and tools. Thus, local communities should promptly implement disaster response strategies through community participation and capacity building.

Risk perception was also proved to significantly affect perceived preparedness (β = 0.213,

p = 0.001), similarly to the ANN results (74.50%). According to studies, the risk perception and fear of disasters increase an individual’s ability to take protective action [

20,

118,

120]. This explains that as individuals become more at risk of natural disasters such as typhoons, they develop more emergency preparedness. In this present study, given that most of the respondents reside in typhoon-prone areas, it can be presumed that they frequently experience typhoon impacts. According to Kurata et al. [

120], people who experienced natural disasters significantly increased their hazard awareness, and they used their acquired knowledge from the experience to prevent future occurrences. It is further explained that people’s risk perception of disaster is affected by the impact and aftermath of calamity on their assets, properties, and livelihood [

120]. Typhoons generate many losses compared to other disasters; according to Bronfman et al. [

127], there is a higher risk perception for typhoons than other disasters.

Physical ergonomics also significantly influenced perceived preparedness (β = 0.158,

p < 0.010) with a 73.80% importance score from the ANN. This finding is supported by prior studies showing that the shelter’s physical design and structural support during calamities were crucial in disaster protection behaviors [

32]. A study by Bashwari et al. [

41] proved that shelters are an integral aspect of disaster response and recovery, especially in large-scale disasters such as typhoons. During calamities, shelters provide personal safety, climate security, and health protection for displaced individuals. Therefore, when planning and developing shelters, many elements should be considered, including their physical location and the demands and needs of potential users. All essential actors, such as local communities, NGOs, and other organizations, should provide complementary support to shelters. Local public health officials should also plan evacuation shelters’ construction, operation, and disassembly. As suggested by the WHO [

131], to guarantee that all community members understand what should be done during an evacuation, affected communities must participate through community leaders, government, and non-governmental organizations. Additionally, the entire planning, response, and recovery process should be overseen by community leaders to aid in the identification and to secure local evacuation shelters. In the same way, community leaders can also assist in evaluating what supplies are available locally and the essential needs people have in the shelters, if any.

On the contrary, cognitive ergonomics (CE) was proven to have no significant influence on perceived preparedness from the SEM (β = 0.021,

p = 0.657) and relatively low significance from the ANN (61.90%). Ong et al. [

104,

105] set a threshold of 60% for the acceptable significance level. The results indicate that CE may not be considered a factor in Filipinos’ perceived preparedness for Typhoon Rai (202122). This means that individuals’ mental and psychological states during typhoons do not play a role in enhancing their coping abilities and preparedness in the face of disaster. This finding contradicts the study of Tugade et al. [

132], which proved that positive emotions are good indicators of coping resources and psychological resilience during adverse events like disasters. As mentioned in a study by Bollettino et al. [

133], Filipinos have developed strong coping mechanisms over their long history of disaster experience since the Philippines is one of the world’s most hazardous countries regarding disaster exposure and vulnerability. Thus, people may lack an emotional basis stemming from previous typhoon experiences.

Because the Philippines is prone to natural disasters, the negative impact caused by typhoons is not unusual. Therefore, better information on typhoon safety measures, evacuation protocols, and shelter and relief operations is recommended to build resilience in disaster response.

5.1. Disaster Management Implications

The Philippines is particularly vulnerable to various risks due to its geographic location, including frequent typhoons, among the deadliest and most expensive natural disasters in the world [

134]. The nation’s economy has suffered long-term effects from major and frequent disasters. Almost USD 8 million is projected to be lost annually from many hazards, roughly 69% of the nation’s spending [

135]. Recent disaster events, particularly Super Typhoon Rai (202122), have resulted in many fatalities, population displacements, and financial expenses, indicating the need for increased disaster preparedness [

136].

The Philippine government has invested a considerable number of resources in enhancing disaster preparedness and lowering susceptibility and exposure. The advantages of investing strategies to reduce the risk of natural disasters can significantly outweigh the expenses. Investing in preparedness and disaster risk reduction not only reduces costs from disasters; but also has positive effects on the economy, society, and environment, which improve the resilience of the country. Concerning this study, it could be seen that citizens of the country adapted to the disaster and are aware of the disastrous events of natural disasters, which led them to prepare. Subsequently, the government may capitalize on this and create mitigation plans and give assistance since people are highly willing to comply and follow based on their knowledge and experience with past natural disasters. The country has decided that preparing for disasters and acting on climate change are mandatory tasks for all levels of government to help shelter development.

The study’s findings also found that disaster knowledge should be given priority and are crucial in supporting institutional policies to enhance the resilience and adaptability of the Filipino people. With the 1.7 million houses, fishing communities, and agricultural land that were destroyed, which affected 9.9 million people across 8 regions, the government was able to act swiftly, which promoted the pre-emptive evacuation plans [

137]. However, it was stated that the government response was still lacking due to the large impact of Super Typhoon Rai’s (202122) aftermath. The government should increase the response, development plans, humanitarian actions, disaster risk reduction, and assess different foreign and local financial institutions. In this way, the aftermath of future massive events may be reduced.

Moreover, reviewing institutional structures, revisiting policy, and addressing problems with resource mobilization are all necessary for disaster preparations. The Philippines’ principal concerns are finding ways to cope with the risks that are continually pushing the country’s institutions and preparedness procedures to their breaking point. In addition, the country recognizes the increasing frequency and severity of catastrophes made worse by climate change. With its high risk, the Philippines can be used as a model by other countries for fostering resilience and advance disaster risk reduction and preparations due to the country and its people’s adaptation and continuous improvement despite the negative effects brought by constant natural disasters such as typhoons [

134].

5.2. Theoretical Contributions

Typhoons are regarded as the most destructive and devastating natural disasters. Although the Philippines is prone to typhoons due to its location along the Pacific Ring of Fire, emergency preparedness and efficient hazard mitigation methods might considerably lessen the effects of typhoons [

20]. The present study investigated the Filipinos’ perceived preparedness for natural disasters, particularly typhoons. The indicators considered in the study are based on ergonomics and disaster risk reduction knowledge. Using the findings of this study, future academicians and disaster planners may look into how ergonomics can help develop disaster preparedness systems that increase resilience by increasing emergency management knowledge, strengthening community coordination and communication, reducing occupational hazards, and improving processes to improve response efficiency and effectiveness. In addition, the model developed in the present study can also be utilized as a theoretical framework for evaluating similar ergonomic-based [

138,

139,

140,

141] and knowledge-based disaster responses.

5.3. Practical Implications

To avoid the risks of typhoons, the outcomes of this study have highlighted the need to learn how to prepare for typhoons by doing the recommended action steps. Knowing the many reaction alternatives increase Filipinos’ confidence in implementing a solution. The study’s findings revealed that residents in highly exposed locations must practice typhoon preparation and evacuation ahead of time. The findings of this study can also be utilized to educate local communities about the importance of emergency response options during a typhoon to lessen the damage and risks associated with it. The findings of this study can potentially be used as a foundation for developing and executing natural disaster risk reduction strategies and policies by LGUs and NGOs.

5.4. Limitations

Despite the study’s encouraging outcomes, a few drawbacks were still considered. First, the investigation only gathered a small number of respondents because the data were only collected for a brief period of time. Thus, a similar study with a larger sample size is advised to conduct a multi-group analysis employing SEM and data mining. Second, the survey questionnaire was only distributed online because of the current COVID-19 pandemic and stringent lockdown execution; hence, most respondents were younger (21–40 y/o) since they have more access to online platforms and social media. Because older persons are more vulnerable to natural catastrophes like typhoons, it is proposed that future studies target respondents from a higher age group (41 and up). This would allow for a more comprehensive examination and explanation of Filipinos’ response effectiveness in preparing for the impending typhoon. In addition, other demographic characteristics may also be focused on, such as respondents of the lower economic bracket and those having less educational attainment, which may result in other results affecting perceived preparedness for super typhoons, such as Typhoon Rai (202122). Due to the limitations of the present scenario, such as COVID-19 lockdowns and closed regions due to the natural disaster, those with access to the internet were the only respondents this study could consider. Lastly, the study did not consider the moderating effects of socio-economic factors such as age, gender, location, residential type, and income on the perceived preparedness of Filipinos for a typhoon. Skewed samples can be observed in age, education, location, and income, which was one of the limitations of using an online survey. In addition, clustering these demographic statuses may also be considered to highlight the difference in behaviors. Hence, future researchers could replicate this study and consider these factors as moderators to confirm the hypotheses proposed in the study.