Abstract

The purpose of this article is to reveal the peculiarities of the agrarian sector deregulation mechanisms in the conditions of the legal regime of martial law and the reasons for the vulnerability of the food security of the country and the world. The process of the agrarian sector deregulation in the period of the legal regime of martial law is clarified with regard to: (a) land matters; (b) taxation; (c) crediting; (d) material and technical support; (e) social and labor relations; and (f) state order. The elements of scientific novelty consist in the introduction of a systematic approach to the generalization of the extraordinary approaches to the process of agrarian sector deregulation during the legal regime of martial law. It is proposed to review the previously adopted documents of a strategic nature regarding the sustainable development of the agrarian sector of Ukraine and to change the mechanisms of the global food crisis fight radically by specially authorized international organizations. The experience of agrarian sector deregulation in the conditions of the legal regime of martial law can be taken into account by the state institutions when reviewing previously adopted documents and during the development of strategic plans for the restoration of the work of commodity producers, guaranteeing the food security of the population and taking into account the internal threats and the long-term external aggression of Russia against Ukraine.

1. Introduction

During wars, man-made disasters, or pandemics, governments usually introduce extraordinary deregulations to deal with challenges, maintain the economic activity of businesses, and maintain a certain level of consumption by the population. After overcoming the force majeure circumstances, there is a difficult period of returning all life-supporting spheres of society and the state to the usual structural and functional state. The economy of Ukraine should recover from a 4.4% drop in GDP caused by the SARS-CoV-2 coronavirus in 2020 over the next two years. However, Russia’s unprovoked full-scale war against Ukraine nullified all forecasts. According to the Decree of the President of Ukraine “On the introduction of martial law in Ukraine”, dated 24 February 2022, No. 64/2022, approved by the Law of Ukraine, dated 24 February 2022, No. 2102 [1], the economy was transferred to the legal regime of martial law.

According to the moderately optimistic scenario of the National Bank of Ukraine (NBU), the fall in GDP in 2022 will be 33.4%. The total deficit of the state budget will reach USD 50 billion, which will be 30–35% of the GDP of Ukraine [2]. Investments will be placed on hold for an indefinite period. At the same time, at the beginning of July, the share of monetary emission among the sources of the financing of the deficit had already reached 40%. For reference, in countries that managed to maintain macro-financial stability during the war, it did not exceed 20% [3]. Gross public debt is expected to grow up to 86.2% of GDP, compared to 49% in 2021 [4].

In an attempt to target inflation, the National Bank of Ukraine in one approach (as of 3 June 2022) increased the discount rate by 2.5 times—from 10% to 25%, previously from 24 February 2022 fixing the rate of the UAH to the US dollar at 29.25, and from 21 July 2022, immediately weakening the UAH by 25%—to 36.57. This should encourage the export of agricultural products and slightly soften the increase in credit rates and the other structural shocks to economic activity. At the same time, the NBU’s reverse stress analysis results show that the twenty largest banks can lose on average up to 25% of their loan portfolio while maintaining a positive core capital [5].

According to a survey conducted by the Ministry of Digital Affairs of Ukraine among 887 owners and managers of enterprises, 46.8% have stopped or almost stopped due to the Russian invasion. Only 6% of businesses adapted to the war. This is also confirmed by the Advanter Group research conducted in June 2022—46% of Ukrainian companies have completely or almost completely ceased their activity [6].

The total direct losses of small and medium-sized businesses from 24 February to June 2022 are estimated at USD 85 billion [7]. According to other surveys, 41% of workers who had official employment before the war lost their jobs, which is more than 4 million people.

According to estimates by the Economist Intelligence Unit, Ukraine is unlikely to be able to reach the pre-war level of GDP before 2037, and the S&P shortens the recovery period to five years. It is clear that these assumptions are quite conditional because the key question of when the war will end remains unknown. Ukraine spends about USD 10 billion in one month on this war, 5–6 billion of which must be covered with the help of foreign revenues [6].

Agriculture historically plays an important role in the development of the Ukrainian economy. The industry provides the population with food products and forms the food security and food independence of the country. Thanks to its powerful economic and natural resource potential, Ukraine is deeply integrated into global agri-food markets.

According to information from the FAO (Food and Agriculture Organization), Ukraine is one of the most important producers of agricultural products in the world and the leader in the supply of food products to world markets. As of 2021, Ukraine is the world’s largest exporter of sunflower oil (35% of world exports), takes second place in the export of barley (14% of world exports), third in the export of corn (11%) and rapeseed (over 10%), and fifth place in the wheat exports (about 10% of world exports).

That is why, according to the authors, it is important to reveal the peculiarities of the agrarian sector deregulation mechanisms in the conditions of the legal regime of martial law and to determine the reasons for the vulnerability of the food security of the country and the world; this was determined as the purpose of this study.

An analysis of the recent research and publications shows that O. M. Halytskyi, A. I. Livinskyi, and O. P. Dyachenko [8], Yu. Ya. Luzan [9], and A. A. Chukhno [10] devoted their research to a wide range of issues related to state (de)regulation of the national economy and its agrarian sector. Thanks to the work of domestic scientists, the problem of the raw material orientation of the export of agri-food production of Ukraine and its socio-economic and ecological consequences are widely covered in the scientific literature. Among them are O. Avramenko [11], P. I. Hayudutsky [12], Y. O. Lupenko [13], O. M. Mohylnyi and M. I. Kozak [14], N. I. Patyka [15], O. V. Shubravska [16], M. I. Pugachov and V. M. Pugachov [17], and others. The new threats to global food security caused by the full-scale war of Russia against Ukraine are considered by P. Koval [18] and by electronic media experts; Ukrainian and foreign top officials in numerous statements and interviews are, as they say, on “hot tracks”.

Therefore, the deregulation of the agrarian sector under the conditions of the legal regime of martial law in Ukraine still requires scientific research and the publication of the results in fundamental publications after its cancellation. Numerous intelligence studies, which were devoted to the Russian occupation of the Autonomous Republic of Crimea and certain areas of the Donetsk and Luhansk regions in 2014, are very important for various reasons. However, the occupation of these territories did not cause significant damage to the agrarian sector as it is mainly industrial enterprises that function here. Hence, there was no question of critical consequences for domestic and global food security at that time. In general, Ukraine lost up to 20% of its economic potential and was able to compensate for it with internal resources. Therefore, there was no need for large-scale deregulation of the sphere of activity of the agrarian companies.

2. Materials and Methods

In order to achieve the defined aim, the following research tasks were formulated:

- -

- To analyze the current conditions and to identify trends in Ukraine’s agrarian sector,

- -

- To follow the evolution of the process of the Ukrainian economy (de)regulation,

- -

- To identify features of Ukraine’s agrarian sector deregulation in the context of martial law,

- -

- To assess the impact of some economic policy measures in the conditions of martial law on the agrarian sector of the economy.

- -

- The methodology used in the study follows the steps below:

- -

- Identification of the research subject and selection of the study area;

- -

- Analysis of the scientific literature;

- -

- Collection of statistical information and development of the database;

- -

- Analysis of the conditions of Ukraine’s agriculture in the years 2005–2021 and 2022;

- -

- Systematization and analysis of the legislative and regulatory documents related to the (de)regulation of Ukraine’s agrarian sector during the period of the legal regime of martial law;

- -

- Revealing of critical important deregulation innovations in the agrarian sector during the period of the legal regime of martial law;

- -

- Assessment of the impact of these deregulation innovations on the agrarian sector;

- -

- Conclusions.

The methodological basis of the study was a systematic approach to the research of the explored phenomena and processes and a dialectical method of cognition, which made it possible to consider comprehensively the new realities of the agrarian sector of the economy and the deterioration of food security associated with the full-scale war of Russia against Ukraine, which began on 24 February 2022.

The research methodology is based on the current information provision and specific calculation algorithms based on the selected datasets. The information base of the study is the data from the State Statistics Service of Ukraine, the Ministry of Economy of Ukraine, the Ministry of Finance of Ukraine, the State Employment Service, other central executive authorities, and the National Bank of Ukraine and the legislative and regulatory legal acts for their implementation, as well as scientific publications. The study period covers 2005–2022.

The study uses a mixed approach, which includes institutional norms for the introduction of (de)regulatory measures by the state on the territory of Ukraine during the period of martial law and the determination of the complex (general) and partial (personalized) indicators of the state of the problem under study with the structuring of the partial indicators into a wider range of indicators available in the system of statistical observations in the period being evaluated.

The main principles of the research methodology in the article are: a comprehensive approach to the characteristics of the agrarian economy (production, foreign trade activity, social, budget and tax, credit sphere, etc.); the application of various methods of calculating individual indicators (production method, income method, index method, etc.), followed by analysis and generalization; the use of relative indicators; and the taking into account of the directions of state policy and the uncertainty of the future conditions for socio-economic development, which currently cannot be predicted in wartime conditions.

From the standpoint of an integrated approach, all the indicators that are a measure of the impact on the development of the agrarian sector of Ukraine were considered in accordance with the target segments for assessing changes at the macro and micro levels.

With the use of empirical tools and expert assessments, the previous macroeconomic losses of the economy, such as the fall in GDP, the deficit of the state budget, the increase in consumer inflation, the decrease in the agrarian sector volume production, the reduction in the number of employees, and others, are highlighted. The negative consequences of providing food to the population of countries that are net importers of grain crops and vegetable oils are foreseen due to the cutting of spring fieldwork on the temporarily occupied territories, the large-scale destruction of agri-food production facilities, elevators, and oil bases, and the blocking of the water area of the Black and Azov seaports and other logistics infrastructure facilities.

Due to the monographic method, the changes in the forms, methods, and state tools for influencing the reproduction of Ukraine’s agrarian sector during the last three decades of the transformations from a centralized–directive–planned economy to a liberal-market economy and the peculiarities of the deregulation mechanisms under the legal regime of martial law were studied.

The system-structural approach made it possible to reveal critically important innovations for the introduction of the deregulation of agri-food production during the period of the legal regime of martial law and, in particular, the introduction of changes and additions to the regulatory legal acts to improve land relations and the state order for food, as well as to the fiscal policy, credit and financial policy, customs tariff policy, phytosanitary policy, social and labor policy, and other policies.

Using data from official statistics, critical analysis, and graphic tools, the dynamics of the production of the main grain and technical crops are shown; the resource balances and the consumption of basic food products by the population of Ukraine are highlighted; and the reasons for the changes in the population’s diet and the demand on the domestic food market, as well as the product structure of the foreign trade of agri-food products and its geography according to the largest importers of Ukrainian products, are revealed.

The structural-logical tools, the systematization of the empirical data, and the worldview position of the authors contributed to the agreed formulation of the intermediate and final conclusions for publication and made it possible to develop proposals aimed at returning the agrarian sector of the economy from a wartime to a peaceful model of sustainable development and provide a perspective vision of the potential for further exploration in the direction of the specified topics.

3. Results

3.1. Analysis of the Current Situation in Ukraine’s Agrarian Sector

Today, agriculture is in the leading position in the Ukrainian economy in terms of production, employment, profitability, and exports. Thus, the share of the industry in the country’s GDP in 2020 was more than 11%; the share of the gross value added of agriculture in the country’s economy was 10.7%. The industry employs 17.1% of the entire employed population. The profitability level of the operating activities was 19.0% (for comparison: the profitability level of the operating activities in the economy as a whole was 6.5% in 2020; in the wholesale and retail trade, it was 16.3%; in IT, it was 15.2%; in industry, it was 4.0%; and in finance and insurance, it was 3.3%). In 2020, the export of agri-food products increased by more than 2.2 times compared to 2010: up to USD 22.179 billion vs. 9.850 billion in 2010. As a result, the share of the agrarian sector in the overall structure of the exports of goods from Ukraine in 2020 reached 45.1% against 19.4% in 2010; that is, almost half of Ukrainian exports are agri-food products. Agricultural lands make up 68.5% of the total land area of Ukraine [19]. That is, all the regions of the country are involved in agricultural production to a greater or lesser extent. Traditionally, the main regions for the production of grain and leguminous crops are the eastern (Kharkiv and Dnipropetrovsk), southern (Zaporizhzhya, Odesa, Kherson, and Mykolaiv), central (Kirovohrad, Kyiv, Cherkasy, and Poltava), and, to some extent, northern (Chernihiv) regions. The largest crops of sugar beets and the main number of sugar factories in the country, and accordingly the production, are located in the Vinnytsia, Poltava, and Khmelnytskyi regions. The specialization in potato cultivation is typical for the northern and northwestern regions of Ukraine (the Zhytomyr, Lviv, and Rivne regions). The southern (Mykolaiv, Kherson, and Odesa) and western (Transcarpathian) regions are most concentrated in the production of vegetables and fruits (Table 1, Figure 1).

Table 1.

Production of the main agricultural crops by Ukraine’s regions in 2021.

Figure 1.

Production of the main agricultural crops by Ukraine’s regions in 2021, thsd.t. Source: Visualized by the authors based on the data of the State Statistics Service of Ukraine [20].

Russia’s brutal attack on Ukraine on 24 February 2022 led to an extremely difficult social and economic situation, which had a particularly painful impact on the country’s agrarian sector. The war made significant adjustments to the whole system of functioning of the industry.

Rural infrastructure, oil bases, warehouses for storing fuel and lubricants, food products, grain elevators and terminals, agricultural machinery, etc., were partially or completely destroyed in many territorial communities. At the beginning of June 2022, 1469 territorial communities [21] were registered in Ukraine, 881 of which are located in rural areas [22]. As of 29 June 2022, 308 (21.0%) territorial communities from nine regions are located in areas where military (combat) operations are conducted or which are under temporary occupation or encirclement (blockade) [23]. These are the territorial communities of the regions of Dnipropetrovsk (7 communities out of 86, or 8.1%); Donetsk (66 communities out of 66, or 100%); Zaporizhia (52 communities out of 67, or 77.6%); Luhansk (37 communities out of 37, or 100%); Mykolaiv (24 communities out of 52, or 46.2%); Kharkiv (51 communities out of 56, or 91.1%); Kherson (49 communities out of 49, or 100%); Sumy (18 communities out of 51, or 35.3%); and Chernihiv (4 communities out of 57, or 7.0%). Approximately, 260 of these 308 communities which are under temporary occupation are rural territorial communities.

In these territories—like previously in the territories of the Kyiv, Sumy, and Chernihiv regions, which were under temporary occupation in the zone of military (combat) operations and were liberated in March—at the beginning of April, the rural settlement network was being destroyed and its structural relationship was deteriorating. In most of the villages that were or are in the zone of active hostilities, the housing stock has been partially and, in some cases, completely destroyed; the housing and utility enterprises do not operate, and the engineering support is in a poor state. In particular, more than 4000 houses in 46 communities were destroyed in the Kyiv region as a result of the occupation of the settlements by the Russian military. Most of the destruction was in the Buchanska, Irpinska, Gostomelska, Borodyanska, Makarivska, Velikodymerska, and Piskovska communities. In merely one village of Andriyivka of the Makariv community, a school and a kindergarten were destroyed, 74 residential buildings were destroyed, another 274 residential buildings need repair, and 43 families need temporary housing [24]. As a result, the attractiveness of living in the rural areas has been lost completely.

In the temporarily occupied territories, the objects of the irrigation and reclamation systems were partially destroyed, and explosive objects and fortifications were left by the enemy on 10% of the agricultural land. Russian troops use the latest engineering systems of remote mining with the help of missiles—cynically named by their developers as “Zemledelie” (translator’s note: arable farming in Russian but with the Latin “Z” at the beginning of the word as the symbol of the Russian so-called “special forces raid”)—and destroy the crops of the grain crops with incendiary shells. According to the Ministry of Agriculture, Ukraine partially lost 25% of the arable land, or almost 8 million hectares. According to various estimates, almost 15% of the animal population was destroyed on farms. Due to the genocide of Russia against the people of Ukraine, many compatriots have an eerie echo of the Holodomor of 1931–1932, organized by the Stalin regime, as a result of which millions of people died.

The FAO report [25] estimated the direct losses of the agricultural assets since the beginning of the war at USD 6.4 billion (including destroyed irrigation infrastructure, storage facilities, machinery and other agricultural equipment, port infrastructure, greenhouses, field crops, livestock, and processing plants).

According to the intelligence results of the Center for Food and Land Use Research of the KSE Institute, conducted together with the Ministry of Agrarian Policy and Food of Ukraine, the indirect losses in agriculture are estimated at USD 23.3 billion, including 51% due to the blockade of ports, 42% due to a decrease in crop production, 4% to an increase in the production cost, and 3% to a decrease in livestock production [26].

Russian troops have committed numerous environmental crimes. Among the main ones are: (a) the seizure of the main structure of the North Crimean Canal, the Kakhovka HPP, and the hydrotechnical nodes that regulated the supply of water from the Kakhovka Reservoir to the Crimean Peninsula; (b) the destruction of warehouses with poisonous chemicals; the de-energizing of large poultry complexes in the temporarily occupied territories; (c) the damage caused to agricultural land and underground water by chemicals seeping into the ground, poisoning the soil and plant nutrition as a result of the destruction of infrastructure facilities; (d) the felling of field protection forest strips, forest park, and recreation zones; and (e) the destruction of agricultural landscapes by explosive devices, fortifications, and heavy military equipment. The Minister of Environmental Protection and Natural Resources of Ukraine believes that as of the 42nd day of the war, more than 100 cases of ecocide have been recorded. Every hit on any infrastructure object or naturally valuable territory is an action aimed at destroying the environment. As of May 2022, the Ministry of Ecology of Ukraine recorded 231 environmental crimes committed by Russia. The total amount of damages has already exceeded UAH 202 billion [27].

As a result of the unprecedented destruction of the means of agri-food production in Ukraine and the use of the Russian policy of limiting the export of Russian agri-food products to “unfriendly” countries, the food supply throughout the world will significantly deteriorate. The Russian mining of the waters of the Black and Azov Seas; the blockade of the ports of Mykolaiv and Odesa, through which 90% of the agri-food products were delivered under export contracts; the breakdown of the production and marketing chains; the impossibility of spring field work and harvesting in the temporarily occupied territories; a surge in prices for scarce means of production; the mobilization of a part of the employees of agricultural companies to the ranks of the Armed Forces of Ukraine (AFU), will lead to a decrease in the volume of the production of grain and oil crops, oriented for export, by up to 30% or more. It is obvious that in the 2022/2023 market year (MY) it is not realistic to compensate for such losses on global markets. For reference, before the war Ukraine ranked fifth in the world in wheat exports, fourth in corn sales, third in barley, and first in sunflower oil.

With the changes in agrarian policy that would allow farmers in European countries and other countries to grow crops on those lands that were previously set aside for biodiversity and recreation or for other reasons of sustainable development and environmentally friendly agriculture, the transition to genetically modified feed and custom tariff restrictions can ensure food security, but only for the citizens of those countries which have a high level of self-sufficiency. In the conditions of the exacerbation of the energy crisis, it is possible to expand the sown areas under the relevant crops, which will also worsen food security. As of 15 July 2022, 18 countries have implemented 27 food export bans, and seven countries have implemented 11 regulations aimed at restricting exports, exacerbating the humanitarian crisis in countries dependent on food imports [28].

Ukraine and Turkey agreed on the unblocking of the export of Ukrainian grain at the negotiations in Istanbul, mediated by the UN. As a result of the “grain corridor” opening from 1 August 1 to 18 September, 3.7 million tons of agricultural products were exported through the ports of Great Odesa. According to the UN, about 30% of the grain was delivered to low- and middle-income countries in Africa, the Middle East, and Asia. In addition, the recovery of grain transportation by sea contributed to the price reduction on the world food market [29,30].

At the same time, the measures taken by the World Food Program (WFP) under the UN to purchase grain crops in Ukraine are not solving the global problem, as the traditional logistics routes are not working at full capacity. In 2021 alone, this international organization purchased more than 50% of the emergency food aid in Ukraine. Obviously, the significant volumes of sales are not so much related to the grain shortage as to the attractive price offer of Ukrainian traders. According to the Minister of Agrarian Policy and Food of Ukraine [31], it is necessary to export at least 20 million tons of grain and technical crops in total from the remnants of the previous years before the onset of 2022/2023 MY. According to the preliminary data, the harvest of early grain and leguminous crops is 65–70 million tons in 2022, and the total capacity for the storage in elevators is rated at 57 million tons; every fourth elevator has been destroyed (at 4 million tons) or is located on the temporarily occupied territory. Therefore, the farmers are actively purchasing alternative means for the temporary storage of the new harvest (polymer sleeves, silage bags, and other mobile warehouses).

As before the unblocking of the seaports, abnormally large volumes of transportation are carried out by rail, road transport, and combined methods with the involvement of the logistics systems of neighboring countries (Romania, Poland, Slovakia, etc.). On average, the cost of logistics increased by 5–7 times, transshipment in ports/barges and freight in general by 7–10 times, and transshipment in ports by 2.5 times. The tariffs for railway transportation have been increased to 70% by the state company “Ukrzaliznytsia”. The financial situation was complicated by the non-reimbursement of VAT on exported agri-food products because as of 12 September it had reached almost UAH 14 billion [32], although it was formally restored from 14 June 2022.

Therefore, purchase prices on the domestic market decreased predictably since the increase in logistics costs is primarily borne by the agrarians. At the same time, world market prices for wheat this year in July rose to the mark of USD 400 per ton, and in Ukraine, USD 60–65 is offered for it, which does not even reimburse the production cost. At a different price offer of the traders for the wheat grain, it may not be competitive on foreign markets. This has already led to the revitalization of shadow dealers and unprofitable production for the entire period of martial law and for more than one year in a row and the displacement of Ukrainian products from traditional markets. Official traders not only purchase grain for export but also create the entire logistics chain, including the forwarding trading on world exchanges.

The response to the rapid increase in food prices was the government’s decision “On Amendments to the Resolution of the Cabinet of Ministers of Ukraine dated 9 December 2020, No. 1236”, dated 29 April 2022, No. 488 [33], which established a trade mark-up of no more than 10% for food products of significant social importance for the period of martial law and three months after its termination, taking into account the costs of advertising, marketing services, services for preparation, processing, packaging, and other costs related to their implementation.

However, this regulatory measure did not stabilize the price situation in the domestic market. Due to the shocks associated with the war, the rate of growth of the prices for the processed group of food products in June this year increased (year to year) to 21.5%. The growth of prices for meat and fish products, margarine, flour products, and non-alcoholic beverages accelerated especially. The prices for sunflower oil are rising slightly more slowly due to the effect of the comparative base and the problems with the export sales [34].

3.2. Evolution of the Process of the Ukrainian Economy (de)Regulation

Over a long historical period, from a free to a state-regulated market, a significant experience of mutual restraint and counterbalance and a mutual penetration and complementarity of institutions of different natures have accumulated. At the same time, while remaining distinct in their ontology, they have the common defect of so-called “failures”, as they do not meet the expectations of the majority of people for a fair distribution of resources and provision of adequate public benefits. As a result, neither the market nor the state nor their interaction became a guarantee of the introduction of a human-centered approach, especially during man-made disasters, various kinds of pandemics, wars, and other extreme situations. Due to the aggravation of food, environmental, energy, climate, and other crises and military threats at the local, regional and global levels, there is less and less time and space left for simple decisions regarding the selection of adequate forms, methods, and tools aimed at the sustainable development of the agrarian sector and guaranteeing food security for the population in the new reality.

Ukraine, like most post-socialist countries, has gone through all the stages of the transformation period—economic liberalization, macroeconomic stabilization, structural restructuring, and market-type institutional innovations. Depending on the mental readiness of societies for change, the political will of state leaders, and the amount of external financial support, various models of the transition from totalitarianism to liberal-democratic state-regulatory relations were introduced: shock therapy (the shortest time to achieve the set goal); gradualism (gradual transition with certain results at each of the stages); and a mixture of the first two (the pace of reforms depended on the central and local authorities, which often replaced each other to the satisfaction of clan-oligarchic forces). According to the authors, Ukraine is characterized by the last model, according to the scheme “one step forward, two steps back”; because the transformation period lasts more than three decades, in international coordinates the economic system has the status of a “developing country”.

Academician A. A. Chukhno [10] (pp. 456–457), analyzing this period in Ukraine, notes that not only reform actions but also economic theory as science were limited by the theory of the market economy. The category “market mechanism” seemed to displace the “economic mechanism” from the scientific research and textbooks in economic disciplines. In his opinion, “market fundamentalism caused the overestimation of the role of the market, the market mechanism and the underestimation of the role of the state, the replacement of the economic mechanism and the mechanism of functioning and development by the market mechanism”.

It is difficult to disagree with the authoritative scientist because, at the beginning of the key economic reforms, the entire economic management system was narrowed down to the market mechanism of the self-regulation of the reproductive processes. This led to the current state of Ukraine’s economy, which before the start of reforms in the 1990s had high hopes of breaking into the cohort of advanced countries. However, it has slipped into a lagging and small economy, dependent on the external conditions of raw material markets, with a decline in the processing and high-tech industries, a physically worn and off-market infrastructure, a significant deterioration in the quality of life and well-being of most households, and a critical stratification of the population by property status and income.

We share the opinion of scientists [35] that the process of deregulation is a specific manifestation of regulatory policy. In a specific period, depending on the object of state-regulatory relations, there is a certain ratio of the influence of the mechanisms of the regulation and deregulation of the economy. The dynamics and level of development of various branches of the economy, individual industries based on innovation, and the business climate of the state at large depend on the degree of their rationality.

In the history of modern Ukraine, deregulation has been remembered for a long time by the exorbitant price of the agrarian sector for membership in the WTO, for the deepened and comprehensive free trade zone with the EU, and for other political concessions. According to the latter, Ukraine reduced (or zeroed out) import duties on 95% of the product nomenclature, while the EU reduced only on 20%, and the export quotas were symbolic and were taken up over one or two months. As a result of the violation of parity, the share of the Ukrainian agricultural and raw material exports in foreign trade operations has increased many times [12] (p. 349). The openness of the domestic food market for the import of finished products led to a structural and technological reversal from the industrial–agrarian economy of Ukraine of the pre-reform period to an agrarian–industrial rent model with consumer exploitation of natural resources by domestic and foreign companies.

During the transition period, a certain tradition has already developed, when the change of elites in state authorities is accompanied by the implementation of pre-election promises of politicians regarding the radical deregulation of business activities, the simplification of services to a “single window”, the transition from the permit-based to the application-based principle of opening and closing a business, a moratorium on checking technological production processes and trade rules, except for those that threaten the life and health of people, etc.

Frequently during the deregulation campaign, the restructuring of the public administration with regulatory powers took place. Often, dozens of legislative and other normative legal acts of a regulatory nature from previous years were canceled in one package. Subsequently, at the behest of interest groups close to the political and business centers of the regulatory decision making, lobbying laws and by-laws were adopted, and the situation was repeated but was exactly the opposite concerning the recipients of preferences. Of course, businesses loyal to the government received market advantages and better competitive positions, while others suffered losses due to economic discrimination. After all, as is known, in the economy resources do not disappear without a trace, they change owners and jurisdiction, and they are redistributed between counterparties, influencing the structure of markets and rankings in the list of the 100 richest people on Forbes Ukraine, etc. Thus, the national economy in manual mode was permanently in a regulated (when the state is stronger than business) or underregulated (when business is stronger than the state) state, and regulatory institutions were never given priority for the benefit of people and society.

Summarizing the different opinions of the scientists, particularly O. M. Halytskyi, A. I. Livinskyi, O. P. Dyachenko [8], Y. Ya. Luzan [9], A. A. Chukhno [10], as well as the politicians and representatives of the expert environment on the issues of the economy’s (de)regulation, we believe that the key features of the transformation period and the transition to a new reality are: firstly, the replacement of the centralized–planned–directive model’s economic mechanism of the economy with the organizational-economic mechanism (OEM) and the (de) regulation of reproductive processes by mainly market means; secondly, the gradual delegation by the state of the performance of functions not inherent to it, which are more effectively performed by market mechanisms and self-governing non-governmental organizations of commodity producers; and thirdly, prevention and prohibition by the state of destructive manifestations of the market element, which lead to the radicalization of socio-economic consequences, especially in extreme circumstances.

Domestic experience has convincingly proved that in the conditions of emerging markets, to which Ukraine belongs, just as the famous “invisible hand” of Adam Smith does not guarantee against “failures (malfunctions) of the market”, especially in the sphere of the fair distribution of additional cost and public goods, so the “visible hand” of the state (de)regulatory body can suffer from arthritis (corruption, favoritism, bureaucratic rent, etc.) and lead to inefficient spending of resources from the position of lost opportunities, distortion of the competitive environment, and several other negative manifestations under weak institutions. It refers to the predatory exploitation of land, water, forest, and other natural resources, neglecting the manifestations of the ecological crisis and climate change. This can be prevented if every mechanism of state intervention in the economy is preceded by analytical calculations of the alternative options for solving the problem, thorough evidence of the effectiveness of the resources involved, and the comprehensive consequences for national well-being, especially in the long term.

Today, in the conditions of martial law, the agrarian sector of Ukraine’s economy needs the introduction of certain elements of the economic policy of dirigisme—effective state regulation of the industry, the main task of which at the first stage should be measures aimed at urgently solving problems related to:

(a) Low level of investment in the processing industry and short value creation chains. This is one of the ways to reduce the share of logistics in the cost of products. For example, livestock production became a profitable industry during the war, although earlier for agro-holding companies it was more a demonstration of socially responsible behavior to maintain the employment of peasants than a well thought-out business policy;

(b) Difficulty in the extreme access to foreign markets for the sale of end and processed products, especially for small and medium-sized enterprises;

(c) Imitation of antimonopoly policy and an underdeveloped competitive environment in the means of the production market;

(d) An imbalance of corporate, regional, and public interests regarding proper land use, VAT reimbursement for the export of raw materials and end products;

(e) Land side deals and corruption in state authorities, which do not stop even under martial law;

(f) Unauthorized (contraband) food inbound into the customs territory of Ukraine, etc.

In contrast to the regulation of the social reproduction of agri-food production in peaceful conditions, deregulation in the situation of the legal regime of martial law involves a significant weakening of direct (administrative and legal) procedures and a significant liberalization of indirect (economic) methods of influence of state institutions on the behavior of the counterparties of market relations. At the same time, the dialogue of the government with self-governing professional organizations of commodity producers and other structures of civil society is being intensified with regard to making decisions, which affects the critically important interests of the people, the state, business, and society at large.

3.3. Deregulation of the Agrarian Sector

The legal order in Ukraine is based on democratic principles, according to which no one can be forced to do what is not provided for by law. According to Art. 19 of the Constitution of Ukraine, central state authorities, local governments, and their officials are obliged to act only on this basis, within the limits of authority, and in the manner provided by legislative acts. Therefore, the transition to a military model of the functioning of the economy in general and its agrarian sector required, in particular, the urgent introduction of changes and additions of mainly deregulatory content to the land, tax, customs codes, and the code of labor laws, and they required emergency adoption by the Cabinet of Ministers of Ukraine, other central and regional authorities, and the local governments of the legal mechanisms for their implementation.

Let us consider the most important of them at the level of central authorities; however, we should make one important caveat first. All state support programs for farmers with the introduction of the legal regime of martial law have been temporarily put on hold. Due to monthly shortfalls to the state budget of up to 50% of taxes and other payments and a significant increase in expenses for the national liberation war, the government finances only the most prioritized and protected items of funding: defense and safety, medicine, salaries in the budget sector, public debt management, and social benefits, to which the assistance to millions of internally displaced persons was also added.

So, let us move directly to the measures of the deregulation of the agri-food producers’ activities. The Law of Ukraine “On Amendments to Certain Legislative Acts of Ukraine Regarding the Creation of Conditions for Ensuring Food Security in the Conditions of Martial Law”, dated 24 March 2022, No. 2145 [36], introduced innovations in various spheres of the agrarian sector functioning.

3.3.1. Deregulation in the Field of Land Relations

The Laws of Ukraine “On Amendments to the Tax Code of Ukraine and other legislative acts of Ukraine regarding the validity of norms during the period of martial law”, dated 15 March 2022, No. 2120 [37], and “On Amendments to the Tax Code of Ukraine and other legislative acts of Ukraine regarding the individual taxes administration during the period of war and state of emergency”, dated 1 April 2022, No. 2173 [38], introduced several tax benefits and significantly liberalized the procedure for monitoring compliance with integrity practices in fiscal policy. For the period of martial law and the following year in which it will be abolished, concessions were granted concerning land fees (land tax and rent) for plots located in territories where hostilities are (were) taking place or in temporarily occupied territories and for plots which are determined by regional military administrations (RMA) as being littered with explosive objects and/or on which fortification structures were discovered. Moreover, for the reporting years of 2022 and 2023, the general minimum tax liability for the specified land plots is not charged and paid.

Agricultural land lease contracts whose term expired after the introduction of martial law are considered to be renewed for one year without the will of the parties and without entering information about the renewal of the contract into the relevant state register. With certain restrictions, district military–civil administrations (DMCA) can lease land plots of state, communal, and former collective property for a period of up to one year. However, the amount of rent cannot exceed 8% of their normative monetary value. Such lease agreements must be concluded only in electronic form, without state registration. The specified norm does not apply to land plots of state and communal property. The free transfer of these lands into private ownership and the granting of permits for the development of relevant land management documentation are prohibited.

Tenants and sub-lessees of agricultural land plots of all forms of ownership are also given the right to transfer them for a period of up to one year to another person for their intended use. Such a transaction is carried out without the consent of the owner of the land plot based on a contract, which is also concluded in electronic form. Registration of changes in land ownership and land use in martial law conditions is carried out by the DMCA in paper and electronic forms.

3.3.2. Deregulation in the Field of Taxation

Starting from 1 April 2022, and until the abolition of martial law, the Law of Ukraine [38] introduced several tax benefits and significantly liberalized the procedure for monitoring compliance with integrity practices in this area.

The large businesses with an annual turnover of up to UAH 10 billion were given the right to choose: to remain on income taxation or to switch to a simplified system with a 2% rate of turnover. It is still unknown yet how the single taxpayers of group 4 (legal entities, regardless of their organizational and legal form, in which the share of agri-food commodity production for the previous tax (reporting) year is equal to or exceeds 75%) will react to this innovation. If it is accepted, value added tax (VAT) in this option will neither be charged nor paid (as of 14 June 2022, VAT refunds to exporters were restored, and tax invoices are registered as usual). Environmental tax can also not be paid but only at the place of business registration on those territories where hostilities were (are) being conducted or which are temporarily occupied by the military of Russia. When importing fuel into Ukraine, all taxes, excise, and customs payments were canceled, and VAT was reduced from 20% to 7%. For sole traders (ST) and farm members, payment of the social security tax (SST) for themselves is voluntary. The specified norm applies to the period starting from 1 March 2002 and will be valid for another year after the abolition of martial law. The ST of the 2nd and 3rd groups were also allowed not to pay SST for hired workers enlisted in the Armed Forces of Ukraine.

3.3.3. Credit Support

Due to martial law, the government changed the mechanism for providing credit support to micro, small, and medium-sized agrarian producers with a turnover of no more than EUR 20 million per year, which applies to enterprises that cultivate from 100 to 10,000 hectares. The interest rate compensation on loans of up to UAH 50 million for works related to the sowing of spring crops is also provided. The term of the loan is 6 months, the maximum amount of the state guarantee for portfolio loans has been established up to 80%, and the application deadline has been determined—until May 31 of this year. As practice has shown, farmers with land plots up to 100 hectares had significant problems obtaining credit support from the state. For reference, according to the State Statistics Service of Ukraine [20], as of November 2020, there were 14,000 farms from 20 to 100 hectares, or 29.4% of the total number of enterprises with a total area of 686,000 hectares, which is equal to 3.3% of all the agricultural lands.

The resolutions of the Cabinet of Ministers of Ukraine “On the provision of financial state support” [39] and “On the provision of state guarantees on a portfolio basis” [40] expanded the program “Affordable loans 5–7–9%”, which was launched in 2020 in the COVID-19 pandemic conditions. The farmers will be able to obtain a 0% loan for a maximum amount of up to UAH 60 million during the martial law and one month after its end. Then, the credit rate will increase to 5%. The loan term under this program depends on the needs of the company. For the implementation of the investment project and the refinancing of debt, the loan is granted for a maximum of 5 years. For working capital financing, the loan is granted for 3 years. The number of tools that allow banks to provide such loans in the case of insufficient collateral for the loan has increased. First of all, 17 creditor banks were identified under state guarantees on a portfolio basis, and then, the list was expanded to 27 institutions. For reference, according to the Ministry of Finance of Ukraine, as of 9 September 2022, 30 396 agricultural producers received UAH 57.174 billion in loans under the “Affordable Loans 5–7–9%” program. Of them, for the sowing campaign until June 1, the amount was UAH 38.551 billion. In addition, these loans were extended from 6 to 12 months at a rate of 0% per annum [41].

The credit guarantee is defined as 80% of the loan amount for micro, small, and medium-sized enterprises (except for large companies). The export credit agency was granted the right to insure the loans of exporting entrepreneurs, which greatly simplified access to financing under this program. Some institutional restrictions on participation in this program have been removed. A Ukrainian company in which Ukrainians are the final beneficiaries with a share of more than 50% will be able to receive a loan. At the same time, enterprises whose participants or ultimate beneficiaries are citizens of the aggressor state or persons who belonged to terrorist organizations do not have this opportunity. The program is implemented through the Entrepreneurship Development Fund, the only participant of which is the government represented by the Ministry of Finance of Ukraine.

However, in the conditions of martial law, the situation is different in the regions with lending to agrarians. According to information from the places [42], the availability of state programs for the farmers depends on the territory of Ukraine, which is divided into certain zones: red (hostile operations are underway), orange (zone is temporarily occupied by the enemy, and areas that share borders with Russia or Belarus), and the green zone (located behind the hostilities). It is almost impossible to receive help from the state in the territories assigned to the red and orange zones, which, unfortunately, changed during the sowing campaign in the direction of expansion. The leaders in the volume of lending during this period became the regions of Kyiv (UAH 3.42 billion), Vinnytsia (2.292 billion), Chernihiv (1.682 billion), Khmelnytskyi (1.228 billion), Kirovohrad (1.120 billion), and Sumy (UAH 1.105 billion). All regions during the sowing campaign could be conditionally classified as rear areas. Of course, the number of borrowers and the loan volume received by them will increase as the territories of Ukraine are liberated from the Russian occupiers.

However, there are problems with the traditional partners of the farmers as well. The risk management of the state and private banks adheres to the pre-war procedures and rules for the borrower, despite the 80% government guarantee of loan security. This means (a) pledge registration for the remaining 20% of the loan amount with a much larger coverage of insured property; (b) equity must be at least 40%; (c) mandatory insurance of the future harvest, which is difficult to arrange in wartime conditions; and (d) provision of the entire documents package (confirmation of profitable activity for the last one to two years, availability of a business plan for newly created farms, etc.), which are not always possible to restore as they were lost due to the theft of the computers or damage to the servers.

The farmers also have many complaints about the functionality of the banking institutions themselves: (a) they use an archaic paper document flow, which makes it impossible to open an account and verify the borrower in real time remotely; (b) not all branches of banks working under lending programs with the government opened in the “green” zone due to lack of staff; and (c) banks do not trust either government guarantees, due to the unprecedented deficit of the state budget, or farmers, since the grain crop remnants of past years remain unrealized, and it is not known whether the logistics for the export of the future harvest will work. As a consequence of the whole set of martial law problems, the state crediting program for commodity producers works with significant delays and not for all farmers, regardless of the land assets size and the form of management.

Judging by information from the Oschadbank of Ukraine press service [43], it responded to the calls of government officials by simplifying the conditions for obtaining loans, namely: (a) the time for making credit decisions was reduced from 8 to 4–5 days; (b) funds are received in 1–2 days; and (c) the conditions regarding the pledge have been liberalized and the requirement for the minimum size of the land plot under cultivation has been canceled. At the same time, the borrower must pay taxes and social security contributions, have a positive credit history and report to state authorities, and officially confirm the availability of land for the current crop. Oschadbank became the leader in financing the seeding campaign and issued almost 2000 loans, every fourth of which is for a new client, worth more than UAH 5.4 billion.

Contradictory information is received from the regions regarding the adaptation of fuel, seeds, fertilizers, and plant protection product enterprise suppliers to the real situation in which the sowing campaign was conducted. Some of them switched to 100% prepayment for resources. Although before the war, banking instruments were used to delay payment for up to one year.

To provide farmers with seeds for the current year’s sowing campaign, the state canceled seed certification procedures. Operating agricultural machines without their registration is allowed. At the same time, according to the information of the Ukrainian Club of Agrarian Business (UCAB), there have been more frequent cases when the district territorial centers of procurement and social support (DTCPSS) have withdrawn from agricultural enterprises more than 50% of the available truck fleet for the needs of the country’s defense, although no more than 30% was planned [44]. For reference, to promptly respond to similar signals from places, unblock channels of material and technical supply, and compensate for losses of land plots and crops on stumps, including from arson by enemy means, the Ministry of Agrarian Policy and Food of Ukraine has created an agrarian platform, which summarizes the current needs for the time of sowing and harvesting operations in real time; (https://agrostatus.org, accessed on 23 September 2022), an online platform for changing the logistics routes of agri-food products, has been opened (https://prodsafety.org, accessed on 23 September 2022).

Owners of agricultural land can count on compensation for material damage by collecting the maximum amount of evidence. The damage must be documented in photos and videos, which include the help of the State Emergency Service (SES), the police, and the employees of the State Geocadastre. As of 14 July 2022, the value of just the grain, oil crops, and oil stolen by Russia in Ukraine since the beginning of the invasion is approximately USD 613 million.

3.3.4. Government Order

For food security, a government order was introduced for 30 basic food products produced in Ukraine. This applies to bakery goods, cereals, sugar, sunflower oil, dairy, and meat products. According to the Ministry of Agrarian Policy and Food of Ukraine, there are 722 domestic producers in the department’s register who receive 30% advance payment from the amount of the order. The entrepreneur receives the rest of the funds after fulfilling the contract for the supply of the products in full for humanitarian purposes, including the free distribution of special food packages to the residents of the temporarily occupied areas and the areas affected by Russia.

The Cabinet of Ministers of Ukraine’s plan of measures to ensure food security in the conditions of martial law, approved by Order No. 327, dated 29 April 2022 [45], defines three critically important areas: administration of the food security system, food provision to the populations of the territorial communities, and regulation of foreign economic activity.

3.3.5. Non-Tariff and Customs Tariff Deregulations

The Cabinet of Ministers of Ukraine, by Resolution No. 398 [46], dated 1 April 2022, “Some issues of implementation of phytosanitary measures and procedures under martial law”, temporarily canceled inspections during food imports. The simplification of import concerns vegetables, edible roots and tubers, edible fruits and nuts, coffee, tea, spices, cereals, products of the flour-milling and grain industry, starch, inulin, wheat gluten, seeds and fruits of oil plants, fruits and grains of technical or medicinal plants, and straw and fodder. Control of such cargoes will be carried out by state phytosanitary inspectors according to a simplified procedure.

The Law of Ukraine, dated 12 May 2022, No. 2246 [47], introduced further changes regarding the simplification of the phytosanitary measures during the export, import, and agri-food products of plant origin movement through the territory of Ukraine; providing farmers with pesticides and agrochemicals; support of organic production; the regulation of importation (forwarding) to the customs territory of Ukraine of the goods subject to documentary checks, conformity checks, and physical checks; and the unlocking of the access of livestock subjects to modern breeding (genetic) material that comes from the farms of those countries that are free from African swine fever and other dangerous animal diseases listed by the International Epizootic Bureau and to which the corresponding animals are susceptible.

Among other measures aimed at the deregulation of the conducting of agrarian business conditions, there are also: the labeling simplification of imported food products and fodder; the removal of bureaucratic obstacles regarding export and licensing of permitted goods groups; the cancellation of licensing for the export of corn and sunflower oil; etc.

The establishment of a zero quota prohibited the export of rye, oats, buckwheat, millet, sugar, and salt (in June of this year, the “moratorium” on millet and sugar was canceled). After licensing, the export of wheat, meslin, millet, sugar, live cattle, beef, poultry, and eggs is allowed.

3.3.6. Liberalization of Social and Labor Relations

For the period of martial law, partial restrictions on the constitutional rights and freedoms of a person and a citizen were introduced, provided for by Articles 43 (rights to work) and 44 (rights to strike) of the Constitution of Ukraine. The effect of certain articles of the Labor Code of Ukraine regarding holidays and non-working days and the reduction in working hours on such days has been suspended. A separate decision of the government [48] approved the procedure for providing the employer with compensation for labor costs for the employment of internally displaced persons. Compensation is provided at the amount of UAH 6500 per month for a person for whom the employer pays SST. The total duration of providing compensation for expenses cannot exceed two months from the day of the person’s employment. An important condition is first the employment of an employee and then the obtaining of the status of an internally displaced person.

Several deregulation measures in the relations between employers and employees are especially important for agrarian companies since the beginning of hostilities coincided with the period of spring fieldwork. The expert community admits that a significant number of drivers of motor vehicles and mechanics eligible for military duty were mobilized to the ranks of the Armed Forces of Ukraine due to the late registration of exemption from active duty for these categories of workers by the heads of agri-food companies.

To promote the development of business, the mandatory creation of new jobs and enterprises and the support of producers on the terms of co-financing in the conditions of martial law, the government orders No. 532 of 21 June 2022 and No. 531 of 24 June [49,50] launched eight programs of non-refundable grant support for small and medium-sized businesses for them to create the new jobs, three of them in the agrarian sector. The Ministry of Economy of Ukraine should allocate UAH 16 billion under the new budget program “Grants for creation or development of business”. These are non-refundable funds for the purchase of equipment for processing agricultural products; partial compensation for the cost of greenhouses with an area of up to 2 hectares; and grants for planting new orchards and berry gardens. As of 23 September 2022, 29 farmers from 13 regions received grant support of a total amount almost of UAH 132 million, with a plantation area of 414 hectares: from 1.34 to 25 hectares and a grant from UAH 360 thousand to 10 million per recipient [51].

So, during the period of the legal regime of martial law analyzed by us, the Verkhovna Rada and the Cabinet of Ministers of Ukraine, simultaneously with the systemic deregulation of agri-food production, partially introduced regulatory measures. The market price regulation mechanism of socially significant food products is applied, and the export of oats, millet, buckwheat, sugar, salt, rye, and cattle is prohibited. Wheat, meslin (its mixture with rye), corn, sunflower oil, meat, and eggs of domestic chickens are allowed to be exported only with prior notification to the government and the obtaining of a license. In addition, a ban on the export of nitrogen, potash, and phosphorus fertilizers has been established. Later, the decision regarding nitrogen fertilizers was revised and the export quota was determined, at the amount of up to 210 thousand tons, but not more than 70 thousand tons per month.

3.4. Production and Export of the Main Agricultural Crops

The analysis of the gross production of the main agricultural crops in 2020 and their export in 2020/2021 MY (Table 2) confirms the significant export potential of Ukrainian agricultural companies. As for corn, this is explained by a significant reduction in the production of livestock products over the past 30 years in farms of all categories: cattle in live weight from 3248.1 thousand tons to 537.5, or more than 6 times; pigs from 2097.8 thousand tons to 966.7, or 2.2 times; sheep and goats from 99.3 to 24.4 thousand tons, or 1.6 times; and milk from 24,508.3 thousand tons to 9263.6, or 2.6 times [52].

Table 2.

Production of main grain and technical crops in 2020 and their export in the 2020/2021 marketing year, million tons.

Almost the entire crop of rape and colza is exported to technologically developed countries (92.3%) due to the lack of equipment for their processing into alternative fuels. The situation is similar with soy, the export of which makes up more than half of the gross production (53.6%).

As for sunflower seeds, this is a cautionary tale for countries with economies in transition. For the first time since the beginning of the neoliberal reforms of the 1990s, the state intervened in this market for the benefit of national companies and society. The Law of Ukraine “On rates of export duty on seeds of certain types of oil crops”, dated September 10, 1999, No. 1033, introduced an export duty on sunflower seeds at the amount of 23% of the customs value. Since then, the fat-and-oil industry has become attractive for investments, hundreds of new jobs have been created, and revenues to the state and local budgets have increased many times. Oil production became highly profitable and reached 7,549,000 tons in 2020 (including the main oil-rich products in terms of oil), which is 5.2 times more than in 2005. Currently, Ukraine occupies a leading position in the world market in terms of the exports of this product. For reference, before the export duty application the export of sunflower seeds in 1998/1999 MY reached 909 thousand tons or 40.1% of 1998′s gross collection, and the production capacities of the processing enterprises were loaded only by 54% as they could not keep up to compete with the rent-oriented companies.

3.5. Balances of Production and Consumption of Agri-Food

Ukraine, with a population of almost 40 million, is completely self-sufficient in basic food products of its production, even in extreme conditions. At the same time, during the analyzed period, important changes occurred regarding individual indicators of food security. However, first of all, we provide the most necessary methodological explanations regarding the calculation of the balance formation indicators of the crop and livestock production’s main products by the State Statistics Service of Ukraine; these are brought into line with international practices and FAO recommendations.

By the group of grain and leguminous crops the “Total resources” indicator has the following natural components: production of the reporting year; change in stocks as the difference between stocks at the end of the year and stocks at the beginning of the year (can be with a negative value when stocks increase at the end of the year and with a positive value when they decrease); and import of the reporting year. The products are exported from the available resources, food requirements for feeding livestock animals are provided, seeds are used for sowing crops in the year following the reporting year, and losses and costs during the storage and processing of products for non-food purposes (biofuel, technical starch, alcohol, etc.) are determined. “Consumption fund” refers to food products used by the population for their needs in any form within households and beyond. It is clear that the resources of sugar, oil, and livestock products in the balance of income and expenditure for the reporting year have their differences because they are not used as seed material. In our opinion, these comments are enough to understand the logic of the further analysis.

As can be seen from the data in Table 3, over the past 16 years the volumes of almost all resources have increased: oil—by 388.7%, grain and leguminous crops—by 185.3, and meat and meat products—by 140.0%. Only sugar resources decreased in 2021 compared to 2005, to 61.5%. This is explained by a drop in production from 2139 thousand tons to 1.416 thousand, or by 33.8%, as well as a decrease in imports (excluding the import of sugar raw materials) from 177 thousand tons to 168 thousand. Against the background of the growth of basic food resources (except sugar), the fund of the specified food consumption by the population tends to decrease, except for meat and meat products.

Table 3.

Balances and consumption of basic food products by the population of Ukraine for 2005–2021, thousand tons.

It is likely that among the main factors of the downward dynamics of demand in the domestic food market was the reduction of the country’s population in 2005–2021 by 6114 thousand people or 12.9% (not including the temporarily occupied territories of the Autonomous Republic of Crimea, the city of Sevastopol, and certain districts of the Donetsk and Luhansk regions), as well as an increase in the import of the specified products of final consumption and the improvement of the household diets. Conversely, the fund for meat and meat product consumption grew by 18.8%. This is a positive phenomenon, although even an increase from 32.8 kg (2000) to 53.0 kg (2021) per average person does not correspond to the rational norm, which is officially defined in Ukraine at the level of 80 kg. In other words, the consumption adequacy index is only 0.66. In the proteins of animal origin consumption structure, the taste preferences of the population coincide with their affordability since, in the structure of total expenditures, the household spends almost 50% on food products on average. Poultry meat is the cheapest; so, it takes up almost half of the diet at 48.5%; pork accounts for more than a third at 34.9%; in the most expensive segment are beef and veal at 15%; and other types of meat account for 1.6%.

3.6. Structure and Geography of Agri-Food Product Export

The agri-food product export–import operations of Ukraine, their structure, causes, and the consequences of the dominance of raw materials are considered by H. A. Al-Ababneh et al. [54], O. Avramenko [11], S. Fedulova et al. [55], P. I. Haydutskyi [12], Yu. O. Lupenko [13], O. M. Mohylnyi and M. I. Kozak [14], N. I. Patyka [15], O. V. Shubravska [16], M. I. Pugachov and V. M. Pugachov [17], O. Yatsenko et al. [56,57], and other scientists.

According to the State Statistics Service of Ukraine [58] regarding the structure of Ukraine’s foreign trade by commodity groups 1–24 of the Ukrainian classification of goods (UCG) IEA, which was developed based on the Harmonized System of Description and Coding of Goods and the Combined Nomenclature of the EU, the following can be proven.

First, over the past 20 years, the revenue from the export of grain crops has increased 76 times (from USD 124 to 9417.3 million). The export of seeds and fruits of oleaginous plants (oilseeds and fruits) increased rapidly—by 9.4 times (from USD 194.8 to 1842.4 million), and fats and oils of animal or vegetable origin—by 24 times (from USD 239.9 to 5759.6 million). The realization of Ukraine’s export potential became real thanks to several factors. Starting from 2000 to 2004, agriculture grew by 6% per year on average, and the processing and food industry grew by 16.4%. During this period, unprecedented protectionist conditions were created for investments in agriculture. They were successfully used by the owners of speculative, financial, and shadow capital, both domestic and foreign, creating agricultural holding structures with offshore jurisdictions. Such organizations with rent-oriented behavior increased the production and export of grains, seeds, and the fruits of oil crops and sunflower oil.

Second, during the same period, there was a significant lag behind the export of raw materials for “Ready-made meals”. If in 2000 the negative trade balance made USD 65 million, then according to the results of 2020 it increased to USD 392.2 million, or more than 6 times. In total, a positive balance was achieved in two subgroups of the goods’ four subgroups of 1–24 of the UCG IEA—“Products of vegetable origin” and “Fats and oils of animal or vegetable origin”. It is obvious that the products of the food industry lost their positions in the foreign markets; moreover, they are also not competitive enough in the domestic market. The reasons for this trend are caused by intra-industry problems, macroeconomic instability, and external factors. In particular, we are talking about the unauthorized importation of food, significant amounts (up to 40%) of side deals on the food market, imperfect custom policy, custom-tariff policy, tax policy, credit and financial policy, and other state policies.

For reference, almost 80% of exports are provided by corn, wheat, barley, and sunflower oil; only 15–20 of the almost 110 million tons of grain and leguminous and oil crops received in 2021 were processed. Twenty was for domestic consumption, and the remaining 65–70 million tons should be exported.

Thirdly, according to the experts, consumers guess quite often about the country of origin of these goods but do not know specific Ukrainian manufacturers because food retailing is usually conducted by foreign intermediary companies that promote Ukrainian goods under their own brands. Therefore, a significant share of the added value in the final products’ price also settles on their accounts.

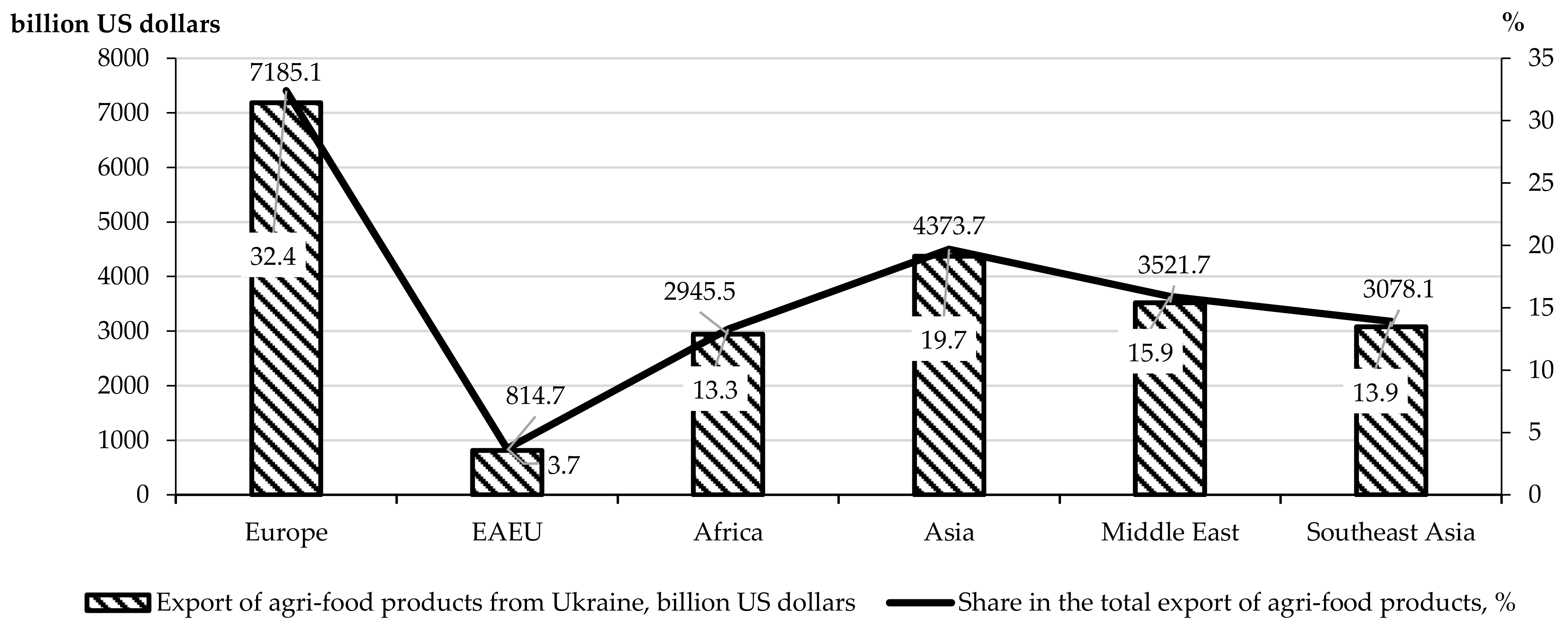

Revenue from the sale of agri-food products to other countries, according to the results of 2020, was equal to USD 22 billion, or 45% of all exports of Ukraine. In 2019/2020 MY, 56.7 million tons of grain and leguminous crops, including corn at 30.3 million tons (53.4%) and wheat and mixtures of wheat and rye at 20.5 million tons (36.1%), were exported. The largest importers of Ukrainian products in 2020 were: Europe (32.4%) at the amount of USD 7.185 billion (the first three places are taken by the Netherlands, Spain, and Poland); Asia (19.7%)—4.373 billion (China, Republic of Korea, and Pakistan); the Middle East (15.9%)—3.522 billion (Turkey, Saudi Arabia, and Israel); Southeast Asia (13.9%)—3.078 billion (India, Indonesia, and Bangladesh), Africa (13.3%)—2.945 billion (Egypt, Tunisia, and Morocco), and the Eurasian Economic Union (EAEU) (3.7%)—USD 814.7 million (Belarus, Kazakhstan, and Russia). The geography of the export of agri-food products by Ukrainian companies is shown clearly in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

The largest importers of Ukrainian agri-food products in 2020. Source: Calculated by the authors based on the data of the State Statistics Service of Ukraine [58].

According to many experts, including, in particular, P. Koval [18], the war in Ukraine threatens South Africa and Asia with famine, where food reserves are designed for 2–3 months of domestic demand. For example, in Lebanon, where bread is the main product, 50% of all wheat came from Ukraine. Libya imported 43% of Ukrainian production grain products. Our state provided about 20% of wheat supplies to Malaysia, Indonesia, and Bangladesh. Yemen, which is almost completely dependent on food imports, buys at least 27% of its wheat from Ukraine. At the same time, according to the author, half of the 30 million population in this country is already starving. A total of 1.7 billion people in more than 30 net importing countries may be on the brink of starvation.

According to information from the electronic resource with reference to FAO [59], in March of this year the average value of the food price index was 159.3 points. This is 12.6% higher than the value in February when it reached the highest level since the creation of this index in 1990. It is clear that in the future, the global situation in agricultural markets will depend on how quickly the seaports will be unblocked (as of 14 June 2022, negotiations with the participation of Ukraine, Turkey, Russia, and the UN continue, and there are prospects for concluding a corresponding agreement on the three Black Sea ports by 22 June of this year) and when Ukraine finally wins the war against Russia.

However, the consequences may be not only economic. Physical food shortages and sudden price surges can lead to the destabilizing of the war–political situation on the African continent and the food crisis of 2007–2008 when political unrest and protests shook 48 countries, as well as mass hunger riots in poor countries similar to those of the Arab Spring in 2012.

This may cause a new wave of migration in search for food, primarily to the countries of Europe and the USA. In conditions of uncertainty and turbulence, the world must recognize that the goals of Sustainable Development announced by the UN up to 2030 [60] regarding the fight against hunger, overcoming threats to life and people’s health, and other safety conditions for the existence of all living things may become somewhat distant due to the military aggression of Russia and its relations with “unfriendly” countries, according to its definition.

4. Discussion

Taking into account the global food threats to all mankind, related to the war of Russia against Ukraine, authorized international organizations (FAO, UNCTAD, UNEP, WFP, and others) have taken appropriate measures to unblock the seaports. However, it is time to develop effective organizational mechanisms for consolidating the efforts of the whole world for global food security and the prevention of “food terrorism” and blackmail with hunger by any aggressor country in the future. In particular, it is proposed to create an influential international organization of grain product exporters.

In various international rankings of the index of economic freedom and other indicators of business (de)regulation, Ukraine occupies an outsider position from year to year. Therefore, the problem of choosing the goals, forms, methods, and tools of state (de)regulatory influence on the functioning of the market self-regulation mechanisms and their interrelation to countries with transition economies or emerging markets remains open for discussion in peaceful conditions. It is generally accepted that, depending on the presence of the state in economic relations (the number of state enterprises, the amount of redistribution of GDP through the state budget, the share of taxes in the national income, etc.), one or another type of economy is formed. It is obvious that in the centrally planned economy, the market economy, and the mixed and transitional economies are significant differences in the main thing—the degree of implementation of the philosophy of human-centeredness and the inclusiveness of the development of public policies at all levels from micro- to macro-spatial locations.

We also consider that promising scientific research directions can be: a) the organizational and functional interaction of state institutions and business and civil society structures for the post-war recovery of Ukraine’s agrarian sector economy; b) the development of mechanisms to prevent the destruction of agro-industrial potential and the threats to world food security due to the aggressive behavior of Russia, which will obviously continue after the de-occupation of all territories as of 2014 and the victory of Ukraine with the participation and comprehensive support of its Western partners.

5. Conclusions