Research on Subjective-Cultural Ecological Design System of Vernacular Architecture

Abstract

:1. Introduction

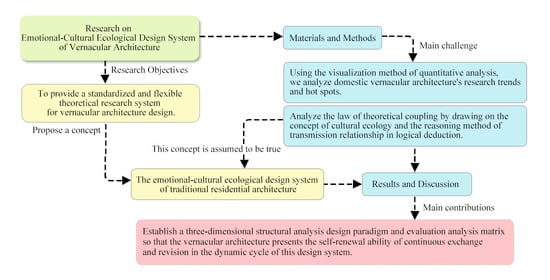

- Through literature review and generalization, this study finds that domestic scholars’ research on the basic theory of vernacular architecture is weaker than the research on technical aspects. At the same time, the visualization method of literature cross-referencing network analysis through the China Knowledge Network presents the academic research hotspots of vernacular architecture. It clarifies the mutual relationship between vernacular architecture, social culture, and residents’ subjective perceptions.

- This study analyzes the theoretical coupling role of the socio-cultural structure of emotion and the cultural ecosystem of vernacular architecture with the help of the concept of cultural ecology and the method of transferring relational reasoning in logical deduction. In this way, it is clear that the interaction between the resident subject and the social culture has an inherently determining role in the inheritance and innovation of vernacular architecture, so the concept of the subjective–cultural–ecological design system of vernacular architecture is proposed.

- Based on the proposed concept, the subjective–cultural–ecological design system of vernacular architecture is constructed, which contains a three-dimensional structural analysis design paradigm and evaluation analysis matrix composed of subject, spatial, and cultural dimensions. This study aims to form a standardized and flexible design research framework system.

- The case demonstrates the operation of this design research framework, presenting the self-renewal ability of vernacular architecture to continuously exchange and revise in the dynamic cycle of this design system. The results show that the subjective-cultural ecological design system not only meets the needs of unified and diverse residents and sustainable development, but also continues the cultural value of vernacular architecture.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design

2.2. Search Strategy

2.3. Data analysis and Conceptual Reasoning

2.3.1. Research Trend Analysis

2.3.2. Research Hotspot Analysis

2.3.3. The Concept of the Subjective-Cultural Ecological Design System for Vernacular Architecture

3. Results

3.1. A Design Research Framework for the Subjective-Cultural Ecological Design System of Vernacular Architecture

3.1.1. Three-Dimensional Structural Analysis Design Paradigm

3.1.2. Evaluation Analysis Matrix

3.2. The Continuous Self-Renewal Characteristics of the Subjective-Cultural Ecological Design System of Vernacular Architecture

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Lu, Q.; Liu, G.W. Research on residential Architecture theory in The New Era. China Famous City 2022, 36, 53–57. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Y.M.; Zhou, C.L. Environmental Behavior and Ergonomics. Master Thesis, China Electric Power Press, Beijing, China, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, J.K.; Wang, Z.; Wu, Y.Q. Research on the Village Reconstruction in Jiangnan Water Town from the Perspective of Self Organization Theory: A case study based on Yangdun Village in Deqing, Zhejiang Province. South. Archit 2022, 6, 01–08. [Google Scholar]

- Max, W.B.; Gu, Z.H. Trans. Basic Concept of Sociology. Master’s Thesis, Guangxi Normal University Press, Guilin, China, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Marcin, G.K.; Wiktor, L. “Świdermajer”, the Architecture of Historic Wooden Summer Villas in the Polish Landscape: A Study of Distinctive Features. Land 2022, 11, 374. [Google Scholar]

- Savaşkan, M.O.; Özener, O.Ö. H-BIM applications for vernacular architecture: A historic rural house case study in Bursa, Turkey. Eng. Constr. Archit. Manag. 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, W.K.; Zhao, L. Rural Vernacular Landscape: A Heritage in Isola Serafini, Po Valley. Ph.D. Thesis, Politecnico di Milano, Milan, Italy, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Boutabba, H.; Boutabba, S.D.; Mili, M. Deciphering spatial identity using space syntax analysis: New rural domestic architecture Diar Charpenti type, Eastern Hodna, Algeria. Int. Rev. Spat. Plan. Sustain. Dev. 2022, 10, 235–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, T.; Hu, Q.N.; Ding, Q.; Zhou, D.; Gao, W.J.; Hiroatsu, F. Towards a Rural Revitalization Strategy for the Courtyard Layout of Vernacular Dwellings Based on Regional Adaptability and Outdoor Thermal Performance in the Gully Regions of the Loess Plateau, China. Sustainability 2021, 13, 13074. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sussman, A.; Hollander, J.B. Cognitive Architecture: Designing for How We Respond to The Built Environment, 2nd ed.; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, J.; Wei, N. Creating a diffuse space. Guangxi Urban Constr. 2016, 89–93. [Google Scholar]

- Qu, Y. Artistic Rural Construction: The third way of Chinese rural construction. Art 2020, 3, 14–19. [Google Scholar]

- Pan, X. The New Knowledge of The Heritage of The Heritage of The Construction and Human Culture of Human Culture; China Building Materials Industry Press: Beijing, China, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Y.W. Research on Inheritance of Traditional Culture Education of Ethnic Minorities from the Perspective of Cultural Ecology. Master’s Thesis, Suzhou University, Suzhou, China, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Dai, Z.Z.; Yang, Y.Z. Regional Architectural Culture of Southwest China Monographs; Hubei Education Press: Wuhan, China, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, F.M. A Study on The Mechanism of Emotional Arousal of The Dai People in The Process Of Social Space Construction–Taking The Example of Manlie Village In Xishuangbanna. Master’s Thesis, Yunnan Normal University, Kunming, China, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Paolo, S. Sentimentai Education in Chinese History; Lin, S.L.; Xie, Y.; Meng, Z., Translators; The Commercial Press: Beijing, China, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Mari, H. Gottfried Semper and the Problem of Historism Monographs; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Lu, H.; Zhang, F.F. A study on the application of five senses theory in the landscape of children’s nature education park. J. Chifeng Coll. (Nat. Sci. Ed. ) 2021, 37, 33–36. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, Z.H. Essays on North Window–Architectural academic Essays. Master’s Thesis, Henan Science and Technology Press:, Zhengzhou, China, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, Y.; Tian, K. Transmission and Infusion: Vernacular Architecture and Its Construction Characteristics in the Tibetan Area of Sichuan Province. Herit. Archit. 2022, 1, 30–41. [Google Scholar]

- Dai, Z.Z.; Li, H.L.; Ren, Z.J. Analysis of Architectural Creation Ideas: Dynamic-Composit; China Planning Press: Beijing, China, 2006. [Google Scholar]

| Cultural Dimensions | Physical Geography | Religious Beliefs | Cultural Communication | Art and Aesthetics | Way of life | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Spatial Dimensions | ||||||

| Scale | V11 | V12 | V13 | V14 | V15 | |

| Form | V21 | V22 | V23 | V24 | V25 | |

| Quality | V31 | V32 | V33 | V34 | V35 | |

| Contact | V41 | V42 | V43 | V44 | V45 | |

| V15 | Space Requirements | Way of Life | Satisfaction Measurement | Importance Ranking | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Scale | Public Space | 1.Separate kitchen space for 1–2 people | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 1 | 2 | 3 |

| 2.Open kitchen activity space | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 1 | 2 | 3 | ||

| 3. Sufficient storage space | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 1 | 2 | 3 | ||

| 4. Compact and flexible bathroom/multipurpose room | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 1 | 2 | 3 | ||

| Private Space | 5. Compact bedroom space | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 1 | 2 | 3 | |

| 6. Spacious bedroom space (with private bathroom) | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 1 | 2 | 3 | ||

| Functional space | 7.High and open living room/terrace | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 1 | 2 | 3 | |

| 8.Vegetable Garden/Flower Garden | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 1 | 2 | 3 | ||

| 9. Reasonable drainage system | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 1 | 2 | 3 | ||

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Zhang, M.; Wang, L.; Zhang, Q. Research on Subjective-Cultural Ecological Design System of Vernacular Architecture. Sustainability 2022, 14, 13564. https://doi.org/10.3390/su142013564

Zhang M, Wang L, Zhang Q. Research on Subjective-Cultural Ecological Design System of Vernacular Architecture. Sustainability. 2022; 14(20):13564. https://doi.org/10.3390/su142013564

Chicago/Turabian StyleZhang, Meng, Lingzhi Wang, and Qingwen Zhang. 2022. "Research on Subjective-Cultural Ecological Design System of Vernacular Architecture" Sustainability 14, no. 20: 13564. https://doi.org/10.3390/su142013564

APA StyleZhang, M., Wang, L., & Zhang, Q. (2022). Research on Subjective-Cultural Ecological Design System of Vernacular Architecture. Sustainability, 14(20), 13564. https://doi.org/10.3390/su142013564