Abstract

Ex-situ poverty alleviation relocation is a vital poverty alleviation measure implemented by the Chinese government. However, studies concerning design evaluation and poverty alleviation relocation houses for minorities are still scarce. Therefore, based on the post-occupancy evaluation method, this work constructs the evaluation index set of the satisfaction of ethnic minorities with their relocated houses, and takes Pu’er City, Yunnan Province, as an example for empirical research. Through correlation analysis and regression analysis, this work discusses their living satisfaction and its influencing factors. The results show that local residents have a high level of satisfaction with infrastructure and building safety. At the same time, residential design, architectural durability, regional characteristics, and other indicators significantly affect the overall satisfaction, and the satisfaction also has population differentiation relating to social and demographic characteristics. Finally, this article puts forward some suggestions to improve the living environment based on two aspects—“residential unit” and “community environment”—which provide references for the improvement and design of ESPAR communities.

1. Introduction

Ex situ poverty alleviation relocation (ESPAR) is one of the essential poverty reduction initiatives in China [1]. The government relocates poor rural households in remote areas, thereby improving their housing conditions, infrastructure services, public facilities, and standard of living [2]. This subsidized resettlement addresses the development dilemma of natural resources not being able to sustain the livelihoods of local people [3]. The idea of moving people to more developed areas rather than investing in scattered hamlets is not unique to China [4], with examples seen in places such as Laos [5], Newfoundland [6], the United States [7,8], and South Africa [9]. In contrast, specific measures under China’s poverty alleviation relocation (PAR) policy mainly include the construction of resettlement areas, infrastructure, public facilities, and new industries [10]. Additionally, resettlement methods mainly include short-distance resettlement, which relocates people to villages within existing administrative boundaries or nearby villages, and long-distance resettlement, which relocates people to small towns [11]. During the “13th Five-Year Plan” period, a total of about 35,000 centralized resettlement areas were built nationwide, with more than 2.66 million resettlement housing units and an average household housing area of 80.6 m2 [12]. With the completion of the relocation work, the effects of the project have been widely studied by the government, society, and academia. It has been shown that relocation increases the income of migrants [13] and improves household livelihoods [14]. However, the reality that has to be faced is that the current relocation approach is relatively crude, with some local governments using the centralized construction of relocation houses with unified planning and arrangement due to high land use and economic concerns. This relocation model is highly efficient and effective, but it does not allow for a specific analysis of specific problems and in-depth research of user needs. Although the government can organize inter-village relocation and provide land and monetary compensation for the property losses of farmers, the future material well-being of migrants is uncertain [15]. At the same time, there is a relative lack of research targeting the occupancy satisfaction of poverty alleviation relocation housing for ethnic minorities.

Studies have categorized the factors that play a decisive role in moving out of and into housing as “push and pull factors” [16]. In the process of poverty alleviation relocation, the environmental conditions that cannot sustain the livelihood of local people and the government’s guidance form the push factor for relocation. Although the newly built resettlement area is a pull factor, a push factor is formed again if the migrants are not satisfied with their relocation site. Significantly, most of the poverty alleviation and relocation areas are within the complex topography of ethnic minority regions with rich and colorful minority residential cultures, which need to be inherited and carried forward. If we adopt the model construction and ignore the real needs of users, it is easy to create “thousands of villages with the same features” and lose the charm of minority housing, causing villagers to be uncomfortable with their environment, leading to homesickness, meaning a backlash is formed and the problem of relocation occurs again. Therefore, there is an urgent need to study the living environment and the satisfaction with it in rural settlements.

The Post-Occupancy Evaluation survey has been widely adopted over the past two decades as an important tool for assessing resident comfort and residency satisfaction and has provided feedback on the built environment through both subjective and objective methods. As for the analysis of residence satisfaction, many existing studies do not distinguish between direct and indirect factors affecting satisfaction and analyze all of these factors as direct influencing factors, and thus it is difficult to analyze the influence process of different factors on residence satisfaction.

In the above context, this study takes the ethnic minority region in southwest China as the study area, starts from the concept of the living environment, is guided by the connotation of POE, uses the path analysis method, combines the theory of living environment with post-occupancy evaluation, and then evaluates the living satisfaction of ethnic minorities regarding PAR housing in rural areas. The conceptual model in this paper is based on the evaluation of the sub-variables directly affecting overall satisfaction, while the socio-demographic characteristics of the users indirectly affect overall satisfaction mainly by influencing the sub-variables, and the influence process of each factor is analyzed. By identifying multiple determinants that might affect satisfaction with the living environment of minority resettlement houses, we proposed improvement strategies for minority resettlement houses. Field questionnaires and in-depth interviews were conducted between 2021 and 2022 in eight typical relocation villages in Pu’er City, Yunnan Province, as the study samples.

This study explores migrant resettlement housing from the perspective of user satisfaction to understand their real needs. On the one hand, from the perspective of social justice theory, exploring the interests and rights of specific socially disadvantaged groups in poverty alleviation and resettlement projects and related themes is a manifestation of achieving spatial justice [17]. On the other hand, research on architectural design feedback for ethnic minority resettlement housing helps to complement the full understanding of the spatial dimension of PAR architecture, provides a reference for the sustainable development of ethnic minority resettlement areas, the sustainable use and improvement of buildings, and the sustainable promotion of policies, and is essential for planning the development of effective and sustainable resettlement housing policies [18].

This paper aims to accomplish three main objectives: first, establishing a theoretical framework for the satisfaction evaluation regarding relocation housing suitable for ethnic minorities in southwest China from the theoretical perspective of the human settlements environment; second, completing an in-depth analysis of the satisfaction characteristics related to the living environment of resettlement housing in the study area and identifying statistically significant correlates informing the housing attributes that can satisfy household needs and maximize satisfaction; and third, proposing targeted recommendations to improve the living environment and provide a basis for improving the quality of life of residents in resettlement communities. We hope to contribute to the sustainable development of ESPAR.

2. Literature Review

2.1. Minority Poverty Alleviation Relocation

Poverty alleviation resettlement (PAR) is a key poverty alleviation initiative for rural development in China, using resettlement as a tool to address environmental and poverty-related issues in a rapidly changing world [19]. As early as 1983, the Chinese government, in response to the severe drought and water shortage in the “Sanxi” regions and the difficulty of survival of the local people, explored the implementation of migration plans, beginning the first poverty alleviation relocation scheme [20].

In 2001, the State Planning Commission formally proposed the concept of “poverty alleviation resettlement”. While this program is unique to China, China’s poverty alleviation relocation program has generally achieved its goal of increasing and restoring livelihood recovery, providing a wide range of opportunities to address environmental and poverty-related issues around the world [14].

Research on the PAR of ethnic minorities is just beginning. Ethnic minority areas are known as the most difficult regions for poverty alleviation relocation in China due to the intertwining of ethnic, poverty, ecological, and social problems. Additionally, studies on this issue are more often found in Chinese journals. Earlier studies focused on the analysis of migrant migration intentions and the factors that influence them. Zhang et al. found that farmers’ willingness to accept rural reconfiguration is the result of a combination of their household characteristics, settlement infrastructure, and occupational factors [21]. Ye tried to use GIS technology to identify suitable resettlement sites for ethnic minority relocation projects [22].

In addition, the problems faced by ethnic minority immigrants after they enter the place of migration have also become a hot topic of concern for scholars. Many scholars have studied the factors influencing the livelihood strategies of ethnic minorities after relocation [23,24]. Additionally, Hu found that spatial segregation was one of the key factors affecting social isolation [25]. Zhu examined the issue of the development of place attachment after relocation and the factors influencing it [10]. In terms of ethnic relations in the relocation site, Luo Rong explored the conflict between ethnic culture and behavior after relocation [26]. Luo Chengsong found that cultural identity was the primary factor influencing ethnic relations [27]. Some scholars have proposed preservation strategies for minority cultures in relocation areas [28]. In terms of the resettlement model, Wu argued that the unified planning and construction model of relocation has led to changes in four spatial aspects [29]. Xie observed the exchange and differences in identity between different ethnic groups within the community [30]. Additionally, in the field of research in architecture, Wang explored the landscape design of ethnic PAR communities [31]. Liu studied the aspects of construction materials and construction [32].

In summary, most of the existing studies on PAR for ethnic minorities focus on economics, management, and anthropology, but less on the architectural and planning levels, especially the building environment factors that affect the satisfaction with living in ethnic minority relocation communities, which are still not sufficiently studied. From the literature studies, we know that immigrants face various problems and challenges upon entering the relocation site. In these contexts, the living environment often becomes an important parameter and plays a crucial role in achieving sustainable development in resettlement areas. Improving the living environment helps to improve the social and physical quality of life of the migrants, helping to bring these poor people truly out of poverty [33].

2.2. Residential Environment Theory Perspective

Housing contributes to poverty and level of deprivation and is an important topic even in countries experiencing a decrease in the overall poverty level [34]. Housing as a form of the built environment [35] should be comfortable, economical, reasonably maintained, architecturally expressive, and at the same time connected and compatible with the environment [36]. The theory of the Human Settlement environment is an important basis for the study of living environmental conditions. The science of Human Settlements originated from urban planning, and early urban planning ideas already reflected the concept of natural ecology as the core of the habitat, such as Howard’s “Garden Cities”. After that, Doxiadis proposed the theory of “Human Settlements”, and believed that the components of habitat include nature, human, society, residence, and supporting networks [37]. The research on the evaluation of living environment has become more and more active under the guidance of the theory of Human Settlement science and sustainable development.

The residential environment usually refers to the sum of various environments surrounding the living space, including natural conditions, various facilities, and the social environment of the region [38]. In 1961, the World Health Organization (WHO) proposed four basic concepts of the residential environment, namely safety, health, convenience, and amenity, and the concept was widely adopted by countries around the world. The Japanese scholar Asami added the idea of sustainability to the traditional four concepts, considering the extent to which individuals contribute to society as a whole [38]. Ge Jian et al. added the concept of “community” to represent the spiritual needs beyond the basic material needs of the living environment [39]. The level of study of the residential environment can be spatially divided into the “housing unit”, the “neighborhood/neighborhood environment”, and the larger urban space.

In a comprehensive view, regarding the evaluation of the residential environment, research hotspots mainly focus on urban and suburban areas [40,41], and some scholars have also evaluated rural areas [42], and most of them have evaluated the objective entities or subjective perceptions of the residential environment by establishing corresponding models and constructing relevant evaluation indicators. Although there are many evaluation indexes, it is difficult to reflect the living environment of relocation and resettlement areas because of the large evaluation scale or the lack of relevance.

The minority settlement environment is a component of the rural habitat environment. The rural habitat environment consists of natural, human-made, and social environments [43], and the environmental components of these settlements determine the well-being and productivity of rural residents [44], for which the construction of targeted evaluation indicators is crucial.

2.3. Post-Occupancy Evaluation Methods and Housing Satisfaction Factors

Post-occupancy evaluation (POE) emerged in the mid-1960s. Research scholars have provided different explanations for the conceptual definition of POE depending on the research perspective. Preiser defined post-occupancy evaluation as “the process of evaluating a building in a systematic and rigorous way after it has been built and occupied for some time” [45], while Zimring viewed POE as “an examination of the effectiveness of human users who occupied design environment” [46]. From the definitions given by scholars, it is obvious that POE plays an important feedback role in the life cycle of a building [47] and provides insights for building industry professionals and facility managers on how to improve the design and operation of the built environment [48], with the building occupants being the focus of post-occupancy evaluation.

POE takes into account a wide range of different performance indicators, including energy and water assessments, indoor environment quality (IEQ), occupants’ satisfaction, productivity, etc. [47]. Currently, POE is mostly used in six building types: residential, university, office, school, public, and hospital buildings [49]. However, POEs of residential housing facilities have only started to receive serious attention in the last two decades [50]. Depending on the depth of the building evaluation, POEs are classified as descriptive, investigative, and diagnostic [45].

Regarding post-occupancy evaluations of low-income or public housing, most of the existing studies in the literature are investigative or diagnostic evaluations, based mainly on objective and subjective evaluation methods, or a combination thereof, with the former being based on experiments with environmental conditions and physical measurements with equipment according to standard procedures. The subjective method is usually based on the subjective perceptions of users, etc., and can be mastered by means of interviews or questionnaires, etc.

Based on objective evaluation methods, many scholars have explored the physical environment of public housing. Zhu Xiaolei discussed the sensitivity of the evaluation index of typical guaranteed housing in Guangzhou and concluded that thermal performance is an urgent issue in the current guaranteed housing living quality [51]. Adaji found that the use of air conditioning in hot and humid climates may not improve the overall thermal comfort of occupants [52]. Becerra-Santacruz’s evaluation of low-income housing in Mexico used a four-dimensional interactive visualization to present the results of temperature and humidity monitoring [53]. Moustafa evaluated the building performance of youth housing in terms of natural ventilation, thermal comfort, and light [54].

On the other hand, scholars have assessed the preferences and satisfaction of public housing residents based on the subjective perceptions of users. Residential satisfaction is the difference between the actual and expected conditions of family housing and community [55]. Understanding the factors that determine the level of housing satisfaction is fundamental to the development of any successful housing policy [56]. Liu suggested that the differences in satisfaction with the living environment among subjects with different social statuses may reflect differences in the perception of social class [57]. Wongbumru’s assessment of satisfaction with old and new public housing in Bangkok was based on three aspects: residential units, building units, and the community environment [58]. Kowaltowski observed problems with public housing in Brazil linked to reduced utility bills [59]. In Kantrowitz’s research, the sense of territory is an important influencing factor of residents’ satisfaction [60]. Ibem believed that the type, location, and aesthetic appearance of the main activity areas, as well as their size, determine public housing satisfaction [61]. Husin tried to relate POE to the security of low-cost housing in Malaysia [62]. Wu et al. argued for the need to pay more attention to sound insulation and community facilities in public housing [63]. Dikmen found that post-disaster public housing residents prefer traditional homes [64]. Additionally, incorporating participatory design in public housing helps to identify the housing needs of the occupants [65]. Zhuang believed that, in future development, more attention should be paid to the user’s subjective feelings, spatial experience, and soft indicators such as architectural appearance and aesthetic quality [66].

From the above studies, it can be seen that the satisfaction level of housing can be studied through the POE method, while the satisfaction level of low-income or public housing can be influenced by the social characteristics of the population and various physical environment factors, and further specific analysis is needed for the factors influencing the ethnic minority PAR housing due to the differences in housing type, society, policy, and culture.

3. Material and Methods

3.1. Study Area

In this paper, Pu’er city was selected as the study area of PAR housing for ethnic minorities in southwest China. Located in the southwestern part of Yunnan Province, Pu’er City shares borders with Vietnam, Laos, and Myanmar and is adjacent to Thailand and Cambodia. Pu’er is the region with the largest number of ethnic groups in Yunnan and the largest number of cross-border ethnic minorities in China [67]. In 2021, there were 26 ethnic groups in Pu’er, with a minority population of 1,457,000, accounting for 61.2% of the total population [68]. Not only do these minority individuals live across the border, but they have also formed a common origin culture and cultural identity, and the ethnic culture of Pu’er has certain similarities with that of South Asia. In terms of relocation projects to alleviate poverty, Pu’er ESPAR was completed mainly in November 2019, with 386 new resettlement areas, ranking 2nd in the province [69]. Therefore, the selection of Pu’er as the study area for the ESPAR project of minorities is typical and representative, and the study of the resettlement housing for minorities in this region has high reference value for other ethnic regions or less developed regions in the world. The ESPAR methods of the minority populations in Pu’er mainly took the form of relocating villagers from the original village to safe neighboring areas or moving them to areas within the same township administrative unit. Additionally, the villagers in the new resettlement area all belonged to the same original village, or the neighboring villages of the same ethnic group were relocated in a unified way to synthesize a new village.

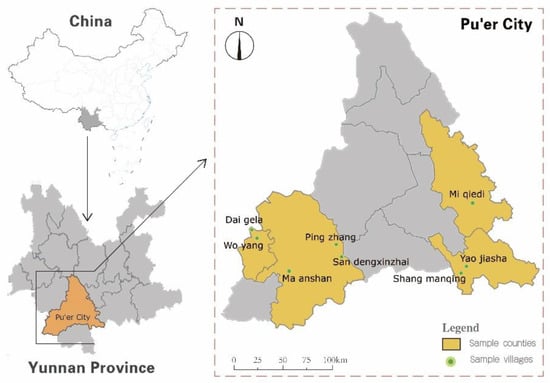

The principles for selecting cases in this study were: first, the community was a new community planned for poverty alleviation relocation; second, the residents of the community were mainly minorities, with the status of farmers and a more stable demographic structure; third, the residents as a whole had moved in to live for more than one year. These principles ensured that the selected cases were typical of minority rural PAR communities; at the same time, the residents had lived there for a long-enough time that their subjective perceptions of the built environment had basically been formed, reflecting the authenticity of the evaluation. Based on the above principles, eight resettlement projects in four typical minority autonomous counties in Pu’er City, China, were selected as evaluation cases. Figure 1 shows the geographical location of the main study cases. Four counties were chosen, namely Mojiang Hani Autonomous County, Jiangcheng Hani Yi Autonomous County, Lancang Lahu Autonomous County, and Ximeng Wa Autonomous County. Two Yao resettlement villages were selected from Jiangcheng County, namely Shang Manqing and Yao Jiashan; two Wa villages were selected from Ximeng, namely Wo Yang and Dai Gra; three Yi villages were selected from Lancang County, namely Ping Zhang Village, Xin Zhai, and Ma Anshan Lahu village; and Mi Qiedi Hani village in Mojiang County was also selected as one of the study objects.

Figure 1.

The locations of the eight ESPAR samples in Pu’er, Yunan, China.

The selected samples satisfy the principles of selecting typical minority resettlement communities, the counties they belong to belong to regions with large minority populations and more relocation and resettlement projects, and the selected samples strive to reflect different ethnic diversity to enhance the representativeness of the study sample.

3.2. Evaluation Framework

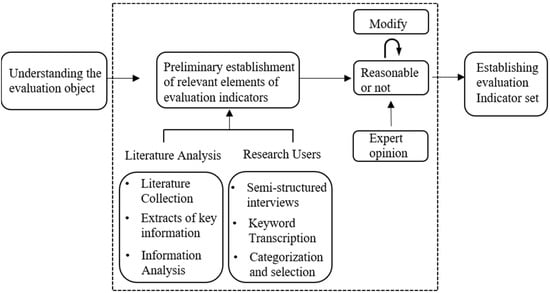

The study used a post-occupancy evaluation method, and the evaluation process was divided into three phases: preparation, implementation, and conclusion [45]. In the preparation phase, first, the purpose and significance of the study were clarified, and the evaluation model was selected. Among the POE evaluation types, diagnostic evaluation enables a comprehensive and in-depth evaluation of detailed performance criteria. Hence, this paper selected diagnostic evaluation as the POE model for resettlement housing. Second, the evaluation index set was designed. Third, the evaluation subject and object were selected. The evaluation object was the migrant relocation and resettlement projects of the eight more typical ethnic minorities in Pu’er, and the evaluation subject was the residential occupants. Then, according to the evaluation indexes, we carried out the questionnaire design. Figure 2 shows the index set establishment process. The selection of evaluation indexes should be systematic and comprehensive as well as scientific, with objectivity and authenticity.

Figure 2.

Indicator set establishment process.

The evaluation indexes of this paper were selected based on the concept of residential environment as the basic framework, absorbing the ideas of safety, health, convenience, comfort, and sustainability, taking the community level as the basic unit of investigation, considering the components of human residential environment, and selecting the evaluation indexes according to the characteristics of migrant relocation and resettlement area construction and the needs of migrants. After combing and drawing on the relevant literature, including the Chinese green building evaluation standards (GB/T50378-2019) and residential performance assessment standards (GB/T50362-2005), the Housing Quality Assurance Act (HQAA) in Japan, the Housing Quality Indicators system (HQI) in the U.K., and the U.S. Housing Quality Standards (HQS) [70], etc., the study was supplemented by introducing semi-structured interviews as a supplement to select the evaluation indicators; after that, three rounds of consultation were conducted using the Delphi expert questionnaire to modify and improve the evaluation indicators.

Finally, the evaluation index system was constructed from seven levels of housing space design, physical environment, building safety, building durability, infrastructure, environmental livability, and regional features, with 30 individual indexes, taking into account the hard and soft environment of the rural residential environment [42], as shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

Post-occupancy evaluation of minority ESPAR housing.

During the implementation phase, a survey was conducted for the selected resettlement area projects. Questionnaires, in-depth user interviews, and walkthroughs were applied to investigate user feedback. In the concluding stage, the score results were compiled, and the evaluation was analyzed and summarized. The regression model was used to analyze the social demographic indicators and the relationship between each indicator regarding overall satisfaction to explore the human settlements of minority ESPAR communities. Finally, targeted recommendations are proposed.

3.3. Formatting of Mathematical Components

The questionnaire consisted of two parts. The post-occupancy assessment framework for this study’s minority ESPAR housing (Table 1) formed the structural basis for the questionnaire sent to occupants. The first part included household individuals’ social demographic information, including gender, age, education level, income, income source, and household size. The second part reflected the resident’s satisfaction with the PAR community. With the help of a semantic questionnaire, each indicator and the overall satisfaction were evaluated by users separately. The evaluation criterion used the Likert scale structure to classify the psychological response to each indicator into five levels. In addition, the sample size of the questionnaire was calculated using the Taro Yamane technique [71], with a 95% confidence level. It was calculated that the survey would require at least 366 survey responses. We determined the number of questionnaires to be distributed in each village in proportion to the population of each of the eight villages.

The surveys were conducted through face-to-face interviews, with respondents randomly selected from among the residents of the resettlement areas. Although Chinese language education is currently widespread in these villages, we had a local language interpreter for each survey in consideration of the elderly. The villagers in the eight villages surveyed had lived in the resettlement area for more than two years. They had accumulated a certain amount of user experience and subjective feelings about their place of residence, which met the needs of this study. In the process of collecting the questionnaires, some of the research subjects were randomly interviewed, and the walkthrough survey was conducted to assist in the later research analysis and discussion.

3.4. Data Collection and Testing

According to the statistical results, at the end of the survey, we distributed a total of 422 questionnaires, excluding those with incomplete answers and misunderstandings, and obtained 408 valid questionnaires, with an effective rate of 96.68% (29 Shang Mangyi, 84 Yao Jiashan, 62 Wo Yang, 38 Dai Gela, 50 Ping Zhang, 87 Xin Zhai, 44 Ma Anshan, 28 Mi Qiedi), which exceeded the calculated questionnaire volume requirement. SPSS software was used for survey preparation, and Cronbach’s alpha coefficient was used to test the reliability between corresponding variables, thus ensuring the reliability of the results. The results show a Cronbach coefficient value of 0.958, indicating that the questionnaire process is reliable.

4. Result

4.1. Satisfaction Evaluation Results

In terms of basic social demographic information, the summary statistics presented in Table 2. show that 56.6% of the respondents are men, with a relatively balanced ratio of men to women. In terms of family structure, two generations (47.8%) predominate, followed by three generations (35.3%). Additionally, 77.5% of the respondents received education in primary school or under, 16.2% of them had received junior high school education, and only 1.7% of the respondents had received university education or above, indicating the low level of education in poor minority areas. Villagers are mainly engaged in the planting (56.6%) and breeding industry (22.5%) as their main source of income. Among the respondents, 43.6% of them have an average annual income higher than 10,000 yuan, 40.2% earn between 5000 and 10,000 yuan, and there are no people who earn less than 3000.

Table 2.

Basic social demographic information of respondents.

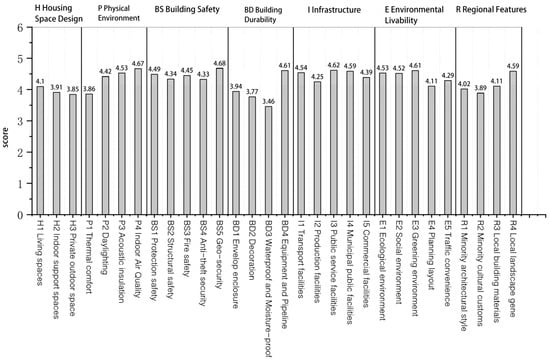

This work regroups the households’ residential satisfaction scores to obtain their overall attitudes towards the different indicators, with scores < 2.5 being grouped to represent negative attitudes, while scores > 4.5 represent positive attitudes, scores 3.5–4.5 represent a good environment, and scores 2.5–3.5 represent neutral attitudes. The average score of residents’ overall satisfaction with the PAR project is 4.02, which is between satisfied and very satisfied, reflecting that villagers’ satisfaction with the project is generally good.

Figure 3 presents the scores of the seven satisfaction components. The villagers’ satisfaction with infrastructure, building safety, environmental livability, and physical environment is relatively high, with an average score of 4.3 or more, while the satisfaction with housing space design, building durability, and regional features is relatively low, with average scores of 3.95, 3.94, and 4.15, indicating the poor performance of these indicators in the surveyed cases. Further investigation of the three dimensions with low satisfaction found that, in the housing space design dimension, the indoor support spaces (3.91) and private outdoor space (3.85) had the lowest satisfaction level. In the building durability dimension, the lowest satisfaction indicator was waterproof and moisture-proof (3.46), indicating problems in this area, and there was poor performance in envelop enclosure (3.94) and decoration (3.77). In the regional features dimension, respondents were least satisfied with the minority cultural customs (3.89). On the other hand, among the secondary factor indicators, those with satisfaction levels above 4.5 include BS5, P4, I3, E3, I4, R4, P3, EI, and E2, representing villagers’ positive attitudes toward these aspects of the built environment. Overall, PAR provides a comfortable and healthy living environment.

Figure 3.

Satisfaction score of sub-variable.

4.2. Influence of Sub-Variable Satisfaction Elements on Overall Satisfaction

A correlation analysis was performed on the valid sample to understand how the index layer factors affect overall occupancy satisfaction. Table 3 shows the Pearson correlation coefficients for all variables, which indicate that all variables have a significant effect on the overall level of residential satisfaction. Under the basic assumption of co-linear diagnosis, each variable was normally distributed. The effect of thermal comfort (0.708) on overall satisfaction is the firmest, which is consistent with scholarly studies [51]. Specifically, in the housing space design layer, indoor support spaces (0.527) and private outdoor space (0.572) had stronger correlations for overall satisfaction than living space (0.430), while in the physical environment dimension, all variables except for thermal comfort had lower correlations for satisfaction. Additionally, in the building safety layer, structural safety (0.501) had a higher correlation than other variables. In the building durability layer, waterproof and moisture-proof (0.609) had a strong correlation, while envelop enclosure (0.544) and decoration (0.561) had a moderate positive correlation, with people’s satisfaction requirements for equipment and pipeline not being very high. In the infrastructure dimension, production facilities (0.553) had the highest correlation. Similarly, in the environment dimension layer, planning layout (0.529) had the highest correlation with satisfaction, while in the regional features layer, minority architectural style (0.595), cultural customs (0.674), and local building materials (0.572) all showed high correlation.

Table 3.

Pearson correlation test between residential satisfaction.

All seven field layers were positively correlated with overall satisfaction, so this work further used least squares (OLS) for regression analysis. The ANOVA test was used for a significance level <0.01, VIF values were all less than 5, and there was no multicollinearity between the variables. Moreover, the R-squared value was 0.624, indicating that the model has good explanatory power. Table 4 shows the results of the multiple linear regression model, demonstrating that the physical environment, building safety, infrastructure, and environmental livability are not significant influencing factors, although they are positively related to residential satisfaction. It is worth noting that housing space design, building durability, and regional features have a significant positive effect on residential satisfaction, which indicates that the residents value these three aspects more.

Table 4.

Regression analysis of seven dimensions influencing overall satisfaction.

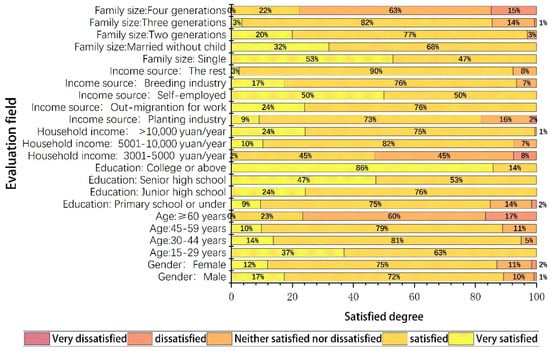

4.3. Influence of Socio-Demographic Variables on Overall Satisfaction

This study considers that the evaluation of the sub-variables directly affects overall satisfaction, while the socio-demographic characteristics of residents indirectly affect overall satisfaction, mainly by influencing the sub-variables. Therefore, we use residents’ ratings of the seven tiers as intermediate variables and socio-demographic characteristics as initial variables to reveal the influence process of initial and intermediate variables on overall satisfaction through path analysis. Table 5 shows the results of the regression analysis of the initial variables on the intermediate variables as well as overall satisfaction. Moreover, the F-test shows that the significance is less than 0.05, which indicates that the predictor variables have a significant effect on the dependent variable, and, in the variance inflation factor tests for multicollinearity, the VIF values are less than 5, indicating that there is no multicollinearity between the variables. Additionally, the F-value indicates that the degree of explanation of the initial variables directly on overall satisfaction is about 36%, which is significantly lower than the degree of explanation of the intermediate variables on overall satisfaction, which indicates that our pre-defined research framework is reasonable.

Table 5.

Influence of socio-demographic variables on satisfaction.

From the regression results, age, income, and household size had a direct effect on overall satisfaction, and Figure 4 shows the scoring of socio-demographic variables on overall satisfaction. On the other hand, all socio-demographic variables have effects on housing space design, except for income source and education, while the variables that affect the physical environment are household income, income source, and family size. It is interesting to note that only household income and income sources affect building safety. Similarly, only age and household income affect building durability. Additionally, age, education, and household income have effects on infrastructure, while environmental livability is influenced by age, household income, and income source. Moreover, age, education, household income, and family size have a significant effect on regional features.

Figure 4.

The scoring of the socio-demographic variables on overall satisfaction.

The use of path analysis allows for exploring the overall impact of the initial variables on overall satisfaction. The overall impact value is equal to the sum of indirect and direct impacts, and regression coefficients with p-values greater than 0.05 are not included in the model. In contrast, from the previous study, only housing space design, building durability, and regional features were found to be significantly positively related to overall satisfaction, so only these three indicators were included in the final model. Table 6 shows the results of the path analysis, with the highest positive effect of household income on overall satisfaction, indicating that higher income has a higher satisfaction level. This is followed by a significant negative association of age and family size with overall satisfaction with residence, implying that the larger the family size and the older the age, the lower the overall satisfaction. It is worth noting that, in previous studies [72], the type of occupation had an effect on satisfaction with living, but in this study, the effect of income type was not significant, while gender has a negative impact on overall satisfaction, mainly through housing space design, while education affects overall satisfaction through regional features.

Table 6.

Path analysis of socio-demographic variables on overall satisfaction.

5. Discussion and Recommendations

In this work, through the POE survey analysis of eight PAR minority villages, we found that the respondents were basically satisfied with their PAR villages. In particular, the living space per capita of PAR housing meets the standard, and it provides residents with safe, convenient transportation and relatively good public facilities and living environments, meaning that it can be said that PAR has improved the original living conditions of ethnic minorities in poor areas. However, it is worth noting that the satisfaction level of the housing space design layer is low, among which the satisfaction level with the auxiliary space and courtyard space is the lowest. In order to prevent the poor villagers from relocating into debt, the government set the limit of construction area per capita, but it was found in the survey that some respondents thought their residential kitchen space was too small, some thought the storage space was lacking or insufficient, and some thought the courtyard space was lacking or inadequate, so the designation of residential policies needs to be more segmented [73]. On the other hand, in the physical environment dimension, thermal comfort satisfaction is poor, which is due to the fact that new houses mainly use ordinary concrete materials, which have poor insulation performance in subtropical regions. Likewise, in the building durability dimension, the performance in water and moisture resistance is poor, probably because the low cost of construction reduces the quality of housing. In the facilities dimension, satisfaction with production facilities was low, with some respondents expressing dissatisfaction at the fact that there were not enough land resources to meet their agricultural needs [74] or because of the distance of the production land from the resettlement area. Meanwhile, in terms of the regional features dimension, the resettlement areas are low-income public housing, while the cost of building new homes with ethnic characteristics is high, and so the new homes are often in a simple form. Middle-aged and older respondents believe that the homes do not meet their cultural practices, probably because most of the new resettlement houses have eliminated the firepit, which in the old homes belonging to ethnic minority cultures is closely related to daily life, and modern kitchens do not meet their needs in some aspects.

On the other hand, this study found through regression analysis that housing space design, building durability, and regional features directly affect overall satisfaction, and age, household income, and household size also directly affect overall satisfaction, while gender and education level indirectly affect overall satisfaction through intermediate variables. Specifically, with the increased household income, villagers have more financial resources to renovate their living environment, while the older the age, the lower the overall satisfaction, which may be due to the fact that, the older the age, the more accustomed to the previous living habits and bad living conditions they are, and moving to a new environment makes them feel a lot of dissatisfaction. In terms of residential design satisfaction, women are less likely to be satisfied than men, probably because women spend more time in the home, such as during housework, cooking, gardening, knitting activities, etc. Interestingly, previous studies have suggested that education level is positively related to satisfaction [75], but this study found a negative relationship between them because placement in residence can only meet the basic needs of survival, and a higher education level may increase the thinking about the living environment, leading to their dissatisfaction.

Regarding this, combining the questionnaire and the environmental status survey, the results of the comprehensive research and analysis are proposed to improve human settlements of minority PAR communities as follows:

- Improvement of dwelling units.

- The study shows that housing space design has the strongest correlation with overall satisfaction, but it performs poorly in terms of satisfaction, while household size and income are significant influencing factors. In future design, designers should consider reserving space for expansion, which can allow residents to add on the second floor or other spaces when they have the financial ability. In addition, villagers pay more attention to outdoor private space and auxiliary space than living space, and future design should consider breeding space, planting space, storage space, and parking space for agricultural machinery to maximize space utilization. To solve the problem of the physical environment, we can try to adopt high-science and low-technology construction technology [76] and combine modern materials with traditional materials [77] to improve thermal comfort performance and reduce energy use and thus the burden on homes [78]. Likewise, building durability is an important factor in improving satisfaction, and resettlement houses, which perform poorly in terms of water and moisture resistance and renovation quality, should be inspected and monitored throughout the building construction phase. In PAR construction, good housing quality contributes to integration into the new community [79].

- Perfection of the community environment.

- The ESPAR project relocates poor people to areas with better living conditions, and the villagers are more satisfied with the performance of infrastructure and environmental livability. It is worth noting that production facilities strongly correlate with overall satisfaction, so it is necessary to consider planning adjacent production land or planning new production methods in the village design to achieve the goal of PAR increase and livelihood restoration [14]. As for the regional characteristics, we should deeply interpret the characteristics of the traditional houses of ethnic minorities, adopt the strategy of “local technology, local materials and local labor” [80], train local craftsmen, and build new houses with ethnic characteristics while reducing economic pressure. Furthermore, the future design should pay more attention to the local attachment needs, living habits, and cultural customs of ethnic minorities, such as preserving and improving the space of fire pits and inheriting the landscape genes, etc., and continuously explore economically affordable and technically feasible ways to update the built environment and ethnic culture, so as to prevent the relocation of relocated people who have not adapted to the environment and experience homesickness.

6. Conclusions

Based on the perspective of residential environment theory, this paper takes people and the environment, ethnic habits, and demands as the starting point, and attempts to construct an evaluation framework from seven dimensions suitable for poverty alleviation relocation (PAR) residences of minorities in southwest China. Using POE as a guiding method, correlation analysis and path analysis are used to explore the factors that affect the satisfaction of PAR residences and propose improvement strategies for different dimensions. The work results show that respondents’ overall satisfaction with PAR residences is good. On the other hand, the main factors affecting the overall satisfaction of PAR residences are building durability, residential design, and regional characteristics, while the socio-demographic characteristics of residents affect the overall satisfaction mainly by influencing the sub-variables. It is worth noting that enhancing the construction quality of PAR houses is a key issue in improving satisfaction.

This study is different from the traditional binary mode of thinking about design objects by design subjects and explores the living satisfaction situation of minority poverty alleviation relocation housing in a specific historical context from experience and demand, identifying their more sensitive and valued human living environment needs to provide a new set of data to guide and help improve the built environment of resettlement projects. Additionally, combining the concept of residential environment with post-use evaluation extends the application scope and evaluation content of post-occupation evaluation.

The limitation of this study is that the context of the study is an assessment conducted within two years of the completion of the overall poverty alleviation relocation program in China, and assessments of residential satisfaction are essentially assessments conducted at a specific point in time, responding to a summary of current occupants’ experiences and expectations [57]. As a society, policy regimes, behaviors, culture, and perceptions change over time, and satisfaction with dwellings is also affected. Therefore, the next step of the study focuses on further research on the research theory to include the influence of time and to clarify the importance of each element to explore the priority of these elements to be satisfied when satisfaction is increased.

It is hoped that the research in this paper can provide some reference for the construction and sustainable development of immigrant resettlement projects, minority housing in other less developed areas, low-income housing projects, and informal settlements in the world and explore a more reasonable development path.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, methodology, investigation, formal analysis, software, writing—original draft, writing—review and editing, X.B.; methodology, investigation, data curation, visualization, writing—review and editing, Z.X.; resources, data curation, supervision, writing—review and editing, funding acquisition, B.J.D. All the authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Acknowledgments

The authors are grateful to Dexin Zong, Zhaoxia Wang, Jun Chen of Chongqing University, Yunfeng Su of the lead architect of Yuanxiang Design Institute, Ya Liu and Huijuan Pu of Yunnan Agricultural University, Yingde Hu and Yao Hu of Pu’er Architectural Design Institute, Zhiyuan He and Huiyun Tan of Yunnan Design Institute, and Zhang Shuming of Huaqiao University for their valuable suggestions in the study. Many thanks to Wanqing Bai of Pu ‘er Shenghao Engineering Company and the villagers and volunteers who enthusiastically provided support and help during our survey.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Hu, W.; Xie, Y.; Yan, S.; Zhou, X.; Li, C. The Reshaping of Neighboring Social Networks after Poverty Alleviation Relocation in Rural China: A Two-Year Observation. Sustainability 2022, 14, 4607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, W.; Xu, J.; Li, J. The Influence of Poverty Alleviation Resettlement on Rural Household Livelihood Vulnerability in the Western Mountainous Areas, China. Sustainability 2018, 10, 2793. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, C.; Guo, M.; Li, S.; Feldman, M. The Impact of the Anti-Poverty Relocation and Settlement Program on Rural Households’ Well-Being and Ecosystem Dependence: Evidence from Western China. Soc. Nat. Resour. 2021, 34, 40–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rogers, S.; Li, J.; Lo, K.; Guo, H.; Li, C. China’s Rapidly Evolving Practice of Poverty Resettlement: Moving Millions to Eliminate Poverty. Dev. Policy Rev. 2020, 38, 541–554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lestrelin, G. Rethinking State–Ethnic Minority Relations in Laos: Internal Resettlement, Land Reform and Counter-Territorialization. Political Geogr. 2011, 30, 311–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Withers, G. Reconstituting Rural Communities and Economies: The Newfoundland Fisheries Household Resettlement Program, 1965–1970. Ph.D. Thesis, Memorial University of Newfoundland, St. John’s, NL, Canada, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- McClure, K.; Schwartz, A.F. Neighbourhood Opportunity, Racial Segregation, and the Low-Income Housing Tax Credit Program in the United States. Hous. Stud. 2021, 1–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aliprantis, D. Racial Inequality, Neighborhood Effects, and Moving to Opportunity. Econ. Comment. 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marais, L.; Ntema, J. The Upgrading of an Informal Settlement in South Africa: Two Decades Onwards. Habitat Int. 2013, 39, 85–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, D.; Jia, Z.; Zhou, Z. Place Attachment in the Ex-Situ Poverty Alleviation Relocation: Evidence from Different Poverty Alleviation Migrant Communities in Guizhou Province, China. Sustain. Cities Soc. 2021, 75, 103355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lo, K.; Xue, L.; Wang, M. Spatial Restructuring through Poverty Alleviation Resettlement in Rural China. J. Rural Stud. 2016, 47, 496–505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- National Development and Reform Commission. The Task of China’s Ex-Situ Poverty Alleviation Relocation during the 13th Five-Year Plan Period Has Been Completed. Available online: https://www.ndrc.gov.cn/fzggw/wld/zcx/lddt/202012/t20201203_1252215.html (accessed on 15 May 2022).

- Leng, G.; Feng, X.; Qiu, H. Income Effects of Poverty Alleviation Relocation Program on Rural Farmers in China. J. Integr. Agric. 2021, 20, 891–904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, C.; Li, S.; Feldman, M.W.; Li, J.; Zheng, H.; Daily, G.C. The Impact on Rural Livelihoods and Ecosystem Services of a Major Relocation and Settlement Program: A Case in Shaanxi, China. Ambio 2018, 47, 245–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Webber, M.; McDonald, B. Involuntary Resettlement, Production and Income: Evidence from Xiaolangdi, PRC. World Dev. 2004, 32, 673–690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pagani, A.; Binder, C.R. A Systems Perspective for Residential Preferences and Dwellings: Housing Functions and Their Role in Swiss Residential Mobility. Hous. Stud. 2021, 1–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, Y.; He, J.; Han, H.; Zhang, W. Evaluating Residents’ Satisfaction with Market-Oriented Urban Village Transformation: A Case Study of Yangji Village in Guangzhou, China. Cities 2019, 95, 102394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kshetrimayum, B.; Bardhan, R.; Kubota, T. Factors Affecting Residential Satisfaction in Slum Rehabilitation Housing in Mumbai. Sustainability 2020, 12, 2344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; de Sherbinin, A.; Liu, Y. China’s Poverty Alleviation Resettlement: Progress, Problems and Solutions. Habitat Int. 2020, 98, 102135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- National Development and Reform Commission. China’s Ex-Situ Poverty Alleviation Relocation Policy. Alleviation Relocation Policy. Available online: https://www.ndrc.gov.cn/fzggw/jgsj/dqs/sjdt/201803/t20180330_1050716.html (accessed on 22 May 2022).

- Zhang, L.; Hong-Ru, D.U.; Lei, J.Q.; Xia, F.Q.; Huo, J.W. Influencing Factors of Reconstructing the Rural Residential Areas in Minority Area in Hotan, Xinjiang. China Popul. Resour. Environ. 2016, 26, 136–147. [Google Scholar]

- Ye, Z.; Li, Y.; Yin, H. Selection of Relocation Program for Poverty Alleviation Based on GIS Technology in Lushui County. Trop. Geogr. 2009, 29, 567–571. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Wu, J.; Xiong, J.; Yang, H. Study on the Impact of Farmers’ Poverty-alleviation Relocation on Livelihood in Minority Areas Based on Quasi-natural Experimental. China Soft Sci. Mag. 2022, 129, 135–148. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Ma, M.; Chen, S.; Tao, S.; Cao, Z. Livelihood strategy, livelihood capital and family income of immigrants involved in poverty alleviation relocation in deeply impoverished ethnic minority areas of Yunnan province. J. Arid Land Resour. Environ. 2021, 35, 1–10. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- HU, W.; UBAURA, M. A Study on Social Integration after Collective Relocation Projects for Poverty Alleviation in China (Part 1): Focusing on Social and Spatial Isolation. J. Archit. Plan. 2021, 86, 925–935. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, R.; Xu, Q.; Wang, Z. A Study on Cultural Conflict in Relocation Areas for Poverty Alleviation in Ethnic Areas. Inn. Mong. Sci. Technol. Econ. 2020, 21, 15–16. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Luo, C.; Yang, H. Cultural Identity of Migrants and the Development of Ethnic Relations-Take the Ex-Situ Relocation in Enle Township, Zhen Yuan County of the Ku Cong Tribe as an Example. J. Simao Teach. Coll. 2011, 27, 13–16. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Liu, L.; Huang, B. Relocation and Protection and Inheritance of National Culture-Take Qianxinan Prefecture as an Example. J. Xingyi Norm. Univ. Natl. 2020, 3, 89–93. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Wu, X.; Duan, Y. Study on the Mode of Poverty-Alleviation Resettlement of Yi People Scattering in Laojun Mountain. J. Dali Univ. 2022, 7, 58–63. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Xie, D.; Yang, X.; Qi, F.; Li, L. Multi-Ethnic Embedding Model and Effectiveness Evaluation of Relocation Communities for Poverty Alleviation in Xinjiang. Minzu Trib. 2021, 3, 94–101. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Wang, J.; Peng, H. Study on the Application of Yao Culture in Landscape Design of Relocation Aimed at Poverty Alleviation of Resettlement Areas. Design 2020, 33, 150–151. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Liu, J.; Tan, L.; Yan, Z.; Yang, L. Research on Regeneration of Traditional Immature Soil Dwellings. Archit. Cult. 2007, 6, 42–44. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Sarkar, A.; Bardhan, R. Socio-Physical Liveability through Socio-Spatiality in Low-Income Resettlement Archetypes—A Case of Slum Rehabilitation Housing in Mumbai, India. Cities 2020, 105, 102840. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalinowski, S. A Multidimensional Comparative Analysis of Poverty Statuses in European Union Countries. Int. J. Econ. Sci. 2022, 11, 146–160. [Google Scholar]

- Rapoport, A. Housing, Culture, and Design: A Comparative Perspective; University of Pennsylvania Press: Philadelphia, PA, USA, 2016; ISBN 1-5128-0428-2. [Google Scholar]

- Henilane, I. The evaluation of housing situation in latvia. In Proceedings of the XVI Turiba University Conference Towards Smart, Sustainable and Inclusive Europe: Challenges for Future Development, Riga, Latvian, 29 May 2015; pp. 93–106. [Google Scholar]

- Doxiadis, C.A. Ekistics, the Science of Human Settlements: Ekistics Starts with the Premise That Human Settlements Are Susceptible of Systematic Investigation. Science 1970, 170, 393–404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asami, Y. Residential Environment: Methods and Theory for the Evaluation; Tokyo University Press: Tokyo, Japan, 2001; ISBN 978-4-13-062202-8. [Google Scholar]

- Ge, J.; Hokao, K. Residential Environment Index System and Evaluation Model Established by Subjective and Objective Methods. J. Zhejiang Univ. Sci. A 2004, 5, 1028–1034. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, L.; Zhang, W.; Yang, Y.; Yu, J. Disparities in Residential Environment and Satisfaction among Urban Residents in Dalian, China. Habitat Int. 2013, 40, 100–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skalicky, V.; Čerpes, I. Comprehensive Assessment Methodology for Liveable Residential Environment. Cities 2019, 94, 44–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, X.; Sun, H.; Chen, B.; Xia, X.; Li, P. China’s Rural Human Settlements: Qualitative Evaluation, Quantitative Analysis and Policy Implications. Ecol. Indic. 2019, 105, 398–405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, G.; He, Y.; Tang, C.; Yu, T.; Xiao, G.; Zhong, T. Dynamic Mechanism and Present Situation of Rural Settlement Evolution in China. J. Geogr. Sci. 2013, 23, 513–524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, P.; Qin, X.; Li, Y. Satisfaction Evaluation of Rural Human Settlements in Northwest China: Method and Application. Land 2021, 10, 813. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Preiser, W.F.; White, E.; Rabinowitz, H. Post-Occupancy Evaluation (Routledge Revivals); Routledge: Abingdon, UK, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Zimring, C.M.; Reizenstein, J.E. Post-Occupancy Evaluation: An Overview. Environ. Behav. 1980, 12, 429–450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, P.; Froese, T.M.; Brager, G. Post-Occupancy Evaluation: State-of-the-Art Analysis and State-of-the-Practice Review. Build. Environ. 2018, 133, 187–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- British Standards Institute(BSI). Building Performance Evaluation of Occupied and Operational Buildings(Using Data Gathered from Tests, Measurements, Observation and User Experience); British Standards Institute(BSI): London, UK, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Sanchez Leitner, D.; Christine Sotsek, N.; de Paula Lacerda Santos, A. Postoccupancy Evaluation in Buildings: Systematic Literature Review. J. Perform. Constr. Facil. 2020, 34, 03119002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leaman, A.; Stevenson, F.; Bordass, B. Building Evaluation: Practice and Principles. Build. Res. Inf. 2010, 38, 564–577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, X. An Environmental Quality Post Occupancy Evaluation on Habitable Space of Typical Affordable Housing in Guangzhou and Exploration on the Sensitivity of Evaluation Indexes. J. Hum. Settl. West China 2017, 32, 23–29. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Adaji, M.U.; Adekunle, T.O.; Watkins, R.; Adler, G. Indoor Comfort and Adaptation in Low-Income and Middle-Income Residential Buildings in a Nigerian City during a Dry Season. Build. Environ. 2019, 162, 106276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Becerra-Santacruz, H.; Patlakas, P.; Altan, H. Evaluation and Visualisation of Mexican Mass Housing Thermal Performance. Proc. Inst. Civ. Eng. Sustain. 2019, 172, 9–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moustafa, W.S.; Abdelrahman, M.M.; Hegazy, I.R. Building Performance Assessment of User Behaviour as a Post Occupancy Evaluation Indicator: Case Study on Youth Housing in Egypt. In Proceedings of the Building Simulation; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2018; Volume 11, pp. 389–403. [Google Scholar]

- Galster, G.C.; Hesser, G.W. Residential Satisfaction: Compositional and Contextual Correlates. Environ. Behav. 1981, 13, 735–758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, M. Determinants of Residential Satisfaction: Ordered Logit vs. Regression Models. Growth Chang. 1999, 30, 264–287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, A.M.M. Residential Satisfaction in Housing Estates: A Hong Kong Perspective. Autom. Constr. 1999, 8, 511–524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wongbumru, T.; Dewancker, B. Post-Occupancy Evaluation of User Satisfaction: A Case Study of “Old” and “New” Public Housing Schemes in Bangkok. Archit. Eng. Des. Manag. 2016, 12, 107–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kowaltowski, D.C.; da Silva, V.G.; Pina, S.A.; Labaki, L.C.; Ruschel, R.C.; de Carvalho Moreira, D. Quality of Life and Sustainability Issues as Seen by the Population of Low-Income Housing in the Region of Campinas, Brazil. Habitat. Int. 2006, 30, 1100–1114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kantrowitz, M.; Nordhaus, R. The Impact of Post-Occupancy Evaluation Research: A Case Study. Environ. Behav. 1980, 12, 508–519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ibem, E.O.; Opoko, A.P.; Adeboye, A.B.; Amole, D. Performance Evaluation of Residential Buildings in Public Housing Estates in Ogun State, Nigeria: Users’ Satisfaction Perspective. Front. Archit. Res. 2013, 2, 178–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Husin, H.N.; Nawawi, A.H.; Ismail, F.; Khalil, N. Improving Safety Performance through Post Occupancy Evaluations (POE): A Study of Malaysian Low-Cost Housing. J. Facil. Manag. 2018, 16, 65–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, F.; Liu, Y.; Zeng, Y.; Yan, H.; Zhang, Y.; Li, L.-H. Evaluation of the Human Settlements Environment of Public Housing Community: A Case Study of Guangzhou. Sustainability 2020, 12, 7361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dikmen, N.; Elias-Ozkan, S.T. Housing after Disaster: A Post Occupancy Evaluation of a Reconstruction Project. Int. J. Disaster Risk Reduct. 2016, 19, 167–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharmin, T.; Khalid, R. Post Occupancy and Participatory Design Evaluation of a Marginalized Low-Income Settlement in Ahmedabad, India. Build. Res. Inf. 2022, 50, 574–594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhuang, W.; Han, M. Post-Occupancy Evaluation: A Review of Methods and State-of-the-Art Techniques. Time Archit. 2019, 4, 46–51. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, H. Pu’er Ethnic Culture Overview; Yunnan University Press: Kunming, China, 2009; ISBN 78-7-81112-851-2. [Google Scholar]

- People’s Government of Pu’er City. Pu’er Overview. Available online: http://www.puershi.gov.cn/pegk/rkmz.htm (accessed on 5 July 2022).

- Development and Reform Commission of Pu’er. Typical Cases of Ex-Situ Poverty Alleviation Relocation in Pu’er City. Available online: https://www.thepaper.cn/newsDetail_forward_10448936 (accessed on 5 July 2022).

- Sinha, R.C.; Sarkar, S.; Mandal, N.R. An Overview of Key Indicators and Evaluation Tools for Assessing Housing Quality: A Literature Review. J. Inst. Eng. Ser. A 2017, 98, 337–347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamane, T. An Introductory Analysis of Statistics; Harper and Row: New York, NY, USA, 1967. [Google Scholar]

- Yin, Y.; He, Y.; Zhang, L.; Zhao, D. Impact of Building Environment on Residential Satisfaction: A Case Study of Ningbo. Sustainability 2019, 11, 1197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borgersen, T.A. Social Housing Policy in a Segmented Housing Market: Indirect Effects on Markets and Individuals. Int. J. Econ. Sci. 2019, 8, 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Souksavath, B.; Nakayama, M. Reconstruction of the Livelihood of Resettlers from the Nam Theun 2 Hydropower Project in Laos. Int. J. Water Resour. Dev. 2013, 29, 71–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biswas, B.; Ahsan, M.N.; Mallick, B. Analysis of Residential Satisfaction: An Empirical Evidence from Neighbouring Communities of Rohingya Camps in Cox’s Bazar, Bangladesh. PLoS ONE 2021, 16, e0250838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wan, L.; Ng, E. High Science and Low Technology for Sustainable Rural Development. Archit. Des. 2020, 90, 74–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, J.; Lu, S. The Renovation of Folk Houses of Enthnic Groups under Critical Regionalism: A Case Study of Lisu Folk Houses in Ganyita Village, Nu River Valley, Yunnan Province. South Archit. 2017, 5, 109–115. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Čermáková, K.; Hromada, E. Change in the Affordability of Owner-Occupied Housing in the Context of Rising Energy Prices. Energies 2022, 15, 1281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dabaieh, M.; Alwall, J. Building Now and Building Back. Refugees at the Centre of an Occupant Driven Design and Construction Process. Sustain. Cities Soc. 2018, 37, 619–627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chi, X.; Ng, E.; Wan, L. How to Provide “Better” Rammed-Earth Buildings to Villagers after Earthquake in Southwest China-A Case Study of Ludian Reconstruction Project. In Proceedings of the PLEA 2017 EDINBURGH, Edinburgh, UK, 16 August 2017. [Google Scholar]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).