Managing Wine Tourism and Biodiversity: The Art of Ambidexterity for Sustainability

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

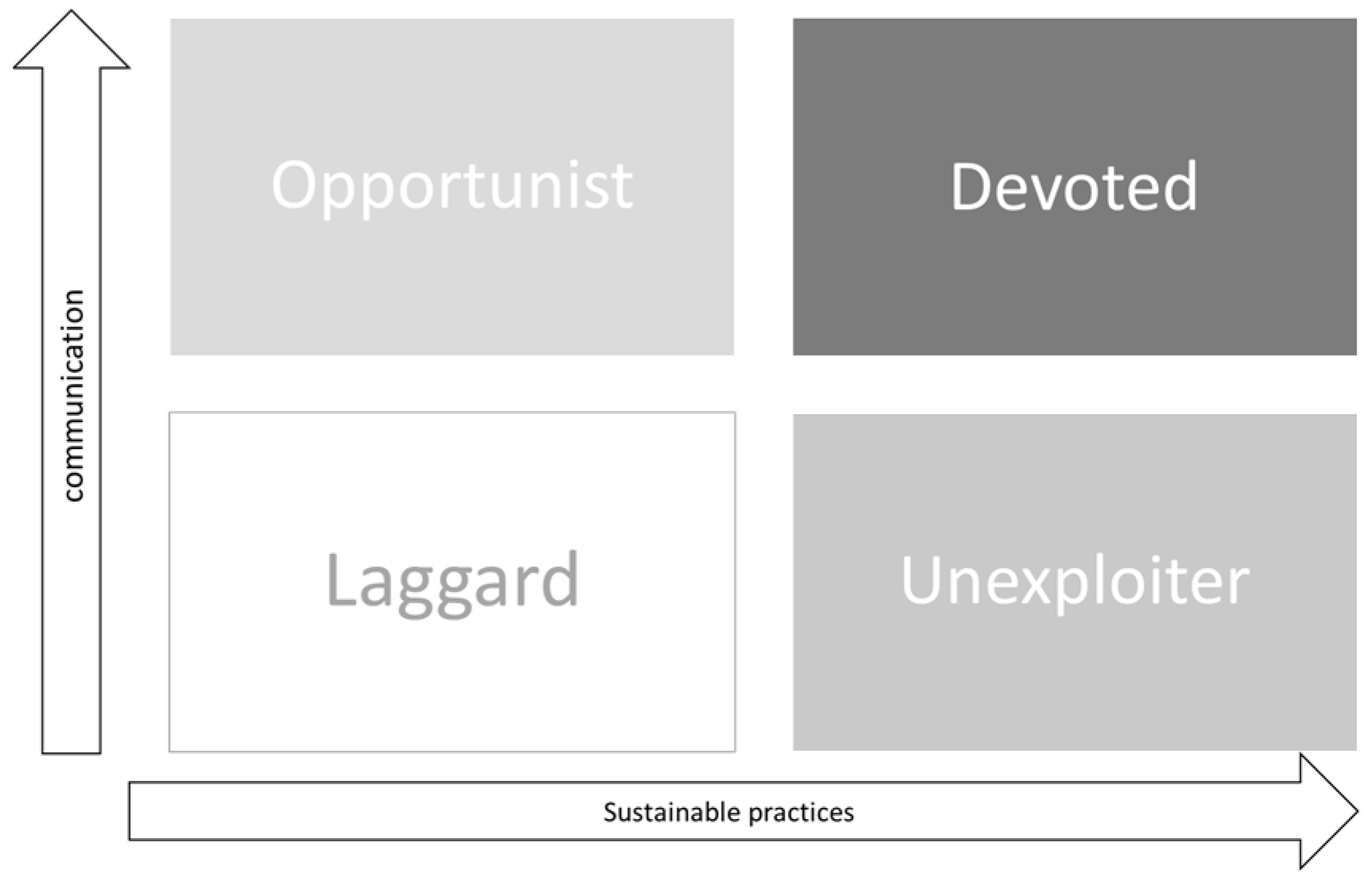

- The “devoted”: they are great promoters of their winery’s sustainability. They implement sustainable practices and communicate on them. They constantly invest in education and training of their staff and customers.

- The “unexploiters”: they have adopted sustainable practices, but they do not communicate about them.

- The “opportunists”: they massively communicate on the sustainable side of their work in order to differentiate themselves on the market, but they lack a deeper motivation or interest for sustainability.

- The “laggards”: they are not interested in sustainable farming at all, and they are not aware of or fail to understand its benefits in terms of communication.

- To what extent do producers understand biodiversity, and how do they implement protection practices on their estates?

- Do these biodiversity protection measures impact their winery’s attractiveness?

- Are biodiversity protection and wine tourism compatible in terms of company management?

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Research Settings: Languedoc Roussilon, a French Touristic Region

3.2. Design of the Study and Data Collection

- Eco-certification

- Wine touristic activity

3.3. Data Analysis

4. Results

4.1. Data Treatment

4.2. Biodiversity Knowledge Is Contrasted among Winery Executives

- Laggard: none

- Opportunist: 1 winery (1)

- Devoted: 9 wineries (2, 4, 5, 6, 8, 9, 10, 11, 12)

- Unexploiter: 3 wineries (3, 7, 13)

4.3. The Unexpected Educationnal Role of Wine Tourism

4.4. Managing Wine Tourism and Biodiversity: When Tensions and Synergies Overlap

4.5. Model of the Producers Ambidexterity between Biodiversity

4.6. Discussion

5. Conclusions and Recommendations

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A. Script of the Interview

- Can you tell me about your wine estate and your wine tourism offer?

- How long have you been involved in wine tourism?

- Why did you develop wine tourism in your area?

- What are your different wine tourism activities? (Visits, catering, accommodation, events…)

- How much time do you devote to each wine tourism activity, per day or per week?

- How many members of your team/family take part in your wine tourism activity(ies)?

- Did you have to invest in your activity?

- -

- buildings (construction, renovation, upgrading)

- -

- landscape (signage, maintenance, wine route)

- -

- hiring of a dedicated person?

- Do you think this activity is profitable?

- Do you think it attracts a population that would not have bought your wines otherwise?

- In your opinion, what is the link between biodiversity of a site and its wine tourism activity?

- What role does the natural environment play in a wine tourism offer?

- Is it an asset and/or a constraint?

- What differentiates your wine tourism offer from a “conventional” estate? Values?

- Are your biodiversity conservation initiatives part of your marketing and communication strategy?

- In your opinion, how can the preservation of biodiversity be improved when developing a wine tourism activity?

- How can these preservation actions be highlighted for visitors?

References

- Blamey, R.K. Ecotourism: The Search for an Operational Definition. J. Sustain. Tourism 1997, 5, 109–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ignatow, G. Cultural Models of Nature and Society: Reconsidering Environmental Attitudes and Concern. Environ. Behav. 2006, 38, 441–461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Becken, S.; Kaur, J. Anchoring “tourism value” within a regenerative tourism paradigm—A government perspective. J. Sustain. Tour. 2022, 30, 52–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frechtling, D. Forecasting Tourism Demand: Methods and Strategies; Routledge: London, UK, 2001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilson, S.; Fesenmaier, D.R.; Fesenmaier, J.; Van Es, J.C. Factors for Success in Rural Tourism Development. J. Travel Res. 2001, 40, 132–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cavicchi, A.; Santini, C. Food and Wine Events in Europe: A Stakeholder Approach; Routledge: London, UK, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Santini, C.; Cavicchi, A.; Casini, L. Sustainability in the wine industry: Key questions and research trendsa. Agric. Food Econ. 2013, 1, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Lu, J.; Nepal, S.K. Sustainable tourism research: An analysis of papers published in the Journal of Sustainable Tourism. J. Sustain. Tour. 2009, 17, 5–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baird, T.; Hall, C.M.; Castka, P. New Zealand Winegrowers Attitudes and Behaviours towards Wine Tourism and Sustainable Winegrowing. Sustainability 2018, 10, 797. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Byrd, E.T.; Canziani, B.; Hsieh, Y.-C.; Debbage, K.; Sonmez, S. Wine tourism: Motivating visitors through core and supplementary services. Tour. Manag. 2016, 52, 19–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gentile, C.; Spiller, N.; Noci, G. How to Sustain the Customer Experience: An Overview of Experience Components that Co-create Value with the Customer. Eur. Manag. J. 2007, 25, 395–410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Altschwager, T.; Conduit, J.; Bouzdine-Chameeva, T.; Goodman, S. Branded marketing events: Engaging Australian and French wine consumers. J. Serv. Theory Pract. 2017, 27, 336–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Charters, S.; Ali-Knight, J. Who is the wine tourist? Tour. Manag. 2002, 23, 311–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alonso, A.D.; Bressan, A.; O’Shea, M.; Krajsic, V. Perceived Benefits and Challenges to Wine Tourism Involvement: An International Perspective: Benefits and Challenges to Wine Tourism. Int. J. Tour. Res. 2015, 17, 66–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barber, N.; Taylor, D.C.; Deale, C.S. Wine Tourism, Environmental Concerns, and Purchase Intention. J. Travel Tour. Mark. 2010, 27, 146–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bruwer, J.; Lesschaeve, I. Wine Tourists’ Destination Region Brand Image Perception and Antecedents: Conceptualization of a Winescape Framework. J. Trave. Tour. Mark. 2012, 29, 611–628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asero, V.; Tomaselli, V. Research Note: Analysing Tourism Demand in Tourist Districts—The Case of Sicily. Tour. Econ. 2015, 21, 1111–1119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sigala, M. The Transformational Power of Wine Tourism Experiences: The Socio-Cultural Profile of Wine Tourism in South Australia. In Social Sustainability in the Global Wine Industry: Concepts and Cases; Forbes, S.L., De Silva, T.-A., Gilinsky, A., Jr., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2020; pp. 55–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sigala, M. A supply chain management approach for investigating the role of tour operators on sustainable tourism: The case of TUI. J. Clean. Prod. 2008, 16, 1589–1599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montella, M. Wine Tourism and Sustainability: A Review. Sustainability 2017, 9, 113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Szolnoki, G. A cross-national comparison of sustainability in the wine industry. J. Clean. Prod. 2013, 53, 243–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campos-Andaur, P.; Padilla-Lobo, K.; Contreras-Barraza, N.; Salazar-Sepúlveda, G.; Vega-Muñoz, A. The Wine Effects in Tourism Studies: Mapping the Research Referents. Sustainability 2022, 14, 2569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grimstad, S. Developing a framework for examining business-driven sustainability initiatives with relevance to wine tourism clusters. Int. J. Wine Bus. Res. 2011, 23, 62–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mazzocchi, C.; Ruggeri, G.; Corsi, S. Consumers’ preferences for biodiversity in vineyards: A choice experiment on wine. Wine Econ. Policy 2019, 8, 155–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zucca, G.; Smith, D.E.; Mitry, D.; Zucca, G.; Smith, D.E.; Mitry, D.J. Sustainable viticulture and winery practices in California: What is it, and do customers care? Int. J. Wine Res. 2009, 2, 189–194. [Google Scholar]

- Forbes, S.; Cohen, D.; Cullen, R.; Wratten, S.; Fountain, J. Consumer attitudes regarding environmentally sustainable wine: An exploratory study of the New Zealand marketplace. J. Clean. Prod. 2009, 17, 1195–1199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- DeLong, D.C. Defining Biodiversity. Wildl. Soc. Bull. 1996, 24, 738–749. [Google Scholar]

- Swingland, I. Encyclopedia of Biodiversity: Definition of Biodiversity, 2nd ed.; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2013; pp. 399–410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Viers, J.H.; Williams, J.N.; Nicholas, K.A.; Barbosa, O.; Kotzé, I.; Spence, L.; Webb, L.B.; Merenlender, A.; Reynolds, M. Vinecology: Pairing wine with nature. Conserv. Lett. 2013, 6, 287–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Demossier, M. Beyond terroir: Territorial construction, hegemonic discourses, and French wine culture. J. R. Anthropol. Inst. 2011, 17, 685–705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torralba, M.; Fagerholm, N.; Burgess, P.J.; Moreno, G.; Plieninger, T. Do European agroforestry systems enhance biodiversity and ecosystem services? A meta-analysis. Agric. Ecosyst. Environ. 2016, 230, 150–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Bruggisser, O.T.; Schmidt-Entling, M.H.; Bacher, S. Effects of vineyard management on biodiversity at three trophic levels. Biol. Conserv. 2010, 143, 1521–1528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Bélis-Bergouignan, M.-C.; Saint-Ges, V.; Cazals, C. Viticulture, vins et pesticides: Un projet collectif, Volet 1: ‘Les innovations environnementales dans la viticulture’. Post-Print (hal-00390622) HAL.

- Casini, L.; Cavicchi, A.; Corsi, A.; Santini, C. Hopelessly devoted to sustainability: Marketing challenges to face in the wine business. In Proceedings of the 119th EAAE Seminar ‘Sustainability in the Food Sector: Rethinking the Relationship between the Agro-Food System and the Natural, Social, Economic and Institutional Environments’, Capri, Italy, 30 June–2 July 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Bruwer, J.; Gross, M.J.; Lee, H.C. Tourism Destination Image (TDI) Perception Within a Regional Winescape Context. Tour. Anal. 2016, 21, 173–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jevic, G.; Popesku, J.; Jević, J. Analysis of Motivating Factors for Visiting Wineries in the Vršac Wine Region (Vojvodina, Serbia). Geogr. Pannonica 2020, 24, 55–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vukojević, D.; Tomić, N.; Marković, N.; Mašić, B.; Banjanin, T.; Bodiroga, R.; Đorđević, T.; Marjanović, M. Exploring Wineries and Wine Tourism Potential in the Republic of Srpska, an Emerging Wine Region of Bosnia and Herzegovina. Sustainability 2022, 14, 2485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woodside, A.G.; Lysonski, S. A General Model of Traveler Destination Choice. J. Travel Res. 1989, 27, 8–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sogari, G.; Mora, C.; Menozzi, D. Sustainable Wine Labeling: A Framework for Definition and Consumers’ Perception. Agric. Agric. Sci. Procedia 2016, 8, 58–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Moscovici, D.; Reed, A. Comparing wine sustainability certifications around the world: History, status and opportunity. J. Wine Res. 2018, 29, 1–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szolnoki, G.; Tafel, M. Environmental Sustainability and Tourism—The Importance of Organic Wine Production for Wine Tourism in Germany. Sustainability 2022, 14, 11831. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Senkiv, M.; Schultheiß, J.; Tafel, M.; Reiss, M.; Jedicke, E. Are Winegrowers Tourism Promoters? Sustainability 2022, 14, 7899. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Serra, M.; Antonio, N.; Henriques, C.; Afonso, C.M. Promoting Sustainability through Regional Food and Wine Pairing. Sustainability 2021, 13, 13759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Telfer, D.J. Strategic alliances along the Niagara Wine Route. Tour. Manag. 2001, 22, 21–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fountain, J. Who’s here? An exploratory study of the characteristics and wine consumption behaviours of visitors at a New Zealand wine festival. In Proceedings of the 8th Academy of Wine Business Research Conference, Geisenheim, Germany, 28–30 June 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Tafel, M.; Szolnoki, G. Estimating the economic impact of tourism in German wine regions. Int. J. Tour. Res. 2020, 22, 22–788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Remeňová, K.; Skorková, Z.; Jankelová, N. Wine tourism as an increasingly valuable revenue stream of a winery’s business model. Ekon. Poljopr. 2019, 66, 23–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carlsen, J.; Dowling, R. Wine Tourism Marketing Issues in Australia. Int. J. Wine Mark. 1998, 10, 23–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smyczek, S.; Festa, G.; Rossi, M.; Monge, F. Economic sustainability of wine tourism services and direct sales performance—emergent profiles from Italy. Br. Food J. 2020, 122, 1519–1529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alonso, A.D.; Liu, Y. Visitor Centers, Collaboration, and the Role of Local Food and Beverage as Regional Tourism Development Tools: The Case of the Blackwood River Valley in Western Australia. J. Hosp. Tour. Res. 2012, 36, 517–536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tafel, M.C.; Szolnoki, G. Relevance and challenges of wine tourism in Germany: A winery operators’ perspective. Int. J. Wine Bus. Res. 2020, 33, 60–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hauck, K.; Szolnoki, G.; Pabst, E. Motivation factors for organic wines. An analysis from the perspective of German producers and retailers. Wine Econ. Policy 2021, 10, 61–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faugère, C.; Bouzdine-Chameeva, T.; Pesme, J.-O.; Durrieu, F. The Impact of Tourism Strategies and Regional Factors on Wine Tourism Performance: Bordeaux vs. Mendoza, Mainz, Florence, Porto and Cape Town; SSRN Scholarly Paper No. 2201563; SSRN: Rochester, NY, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Presentation. Available online: https://web.archive.org/web/20080523111146/http:/www.legrenelle-environnement.fr/grenelle-environnement/spip.php?rubrique112 (accessed on 19 October 2022).

- Observatoire de la Production Bio Nationale. Agence Bio. Available online: https://www.agencebio.org/vos-outils/les-chiffres-cles/observatoire-de-la-production-bio/observatoire-de-la-production-bio-nationale/ (accessed on 19 October 2022).

- Van Leeuwen, C.; Darriet, P. The Impact of Climate Change on Viticulture and Wine Quality. J. Wine Econ. 2016, 11, 150–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Botkin, D.B.; Saxe, H.; Araújo, M.B.; Betts, R.; Bradshaw, R.H.W.; Cedhagen, T.; Chesson, P.; Dawson, T.P.; Etterson, J.R.; Faith, D.P.; et al. Forecasting the Effects of Global Warming on Biodiversity. BioScience 2007, 57, 227–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Voss, C.; Tsikriktsis, N.; Frohlich, M. Case research in operations management. Int. J. Oper. Prod. Manag. 2002, 22, 195–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miles, M.B.; Huberman, A.M.; Saldana, J. Qualitative Data Analysis: A Methods Sourcebook; SAGE Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Eisenhardt, K.M. Building Theories from Case Study Research. Acad. Manag. Rev. 1989, 14, 532–550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Assarroudi, A.; Heshmati Nabavi, F.; Armat, M.R.; Ebadi, A.; Vaismoradi, M. Directed qualitative content analysis: The description and elaboration of its underpinning methods and data analysis process. J. Res. Nurs. 2018, 23, 42–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- O’Reilly, C.A.; Tushman, M.L. The Ambidextrous Organization. Harv. Bus. Rev. 2004, 82, 74–82. [Google Scholar]

- Barber, B.M.; Morse, A.; Yasuda, A. Impact investing. J. Financ. Econ. 2021, 139, 162–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sigala, M.; Haller, C. The impact of social media on the behavior of wine tourists: A typology of power sources. In Management and Marketing of Wine Tourism Business; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2019; pp. 139–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Interview ID Number | Type of Wine Estate | Vineyard Surface | Position of the Interviewee | Eco-Certification | Wine Tourism Offer |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Independent winery | 35 ha | Wine tourism manager | European organic certification | Vineyard tour, tastings, workshops, fine dining, concerts, masterclasses |

| 2 | Cooperative of 260 producers | 2000 ha | Commercial manager | Vignerons Engagés | Tastings, visits, workshops, vineyard tours |

| 3 | Independent winery | 70 ha | Winery owner | European organic certification | Tastings |

| 4 | Independent winery | 32 ha | Winery owner | European organic certification, Demeter | Parties, vineyard tours, exhibitions, tastings |

| 5 | Independent winery | 30 ha | Commercial director | European organic certification | Concerts, exhibitions, markets, vineyard tours, picnics |

| 6 | Family-owned winery | 50 ha | Winery manager | ISO 26000, HVE | Open days, vineyard tours, tastings, soft mobility tours, workshops |

| 7 | Independent winery | 60 ha | Winery owner | Terra Vitis | Vineyard tours, child-friendly activities, exhibitions, catering, electric scooters, concerts, escape game, private venue |

| 8 | Independent winery | 50 ha | Winery owner | HVE | Tastings, wine shop |

| 9 | Independent winery | 50 ha | Communication and event manager | European organic certification | Reception venue, exhibition, concerts and DJ sets, guided visits, pub |

| 10 | Independent winery | 23 ha | Winery owner | European organic certification | Corporate workshops, Airbnb Experience, catering, bed and breakfast |

| 11 | Association | 18 ha | Association manager | European organic certification | Vineyard tours, visits, concerts, farmers’ market, concerts, exhibitions, wine shops |

| 12 | Independent winery | 150 ha | Wine cellar manager | European organic certification | Tastings, vineyard tours, wine cellar visits, workshops |

| 13 | Independent winery | 60 ha | Winery owner | Terra Vitis | Wine shop, tastings, workshops, picnic baskets |

| 14 | Cooperative of 70 producers | 700 ha | Communication and wine tourism manager | Ecophyto | Electric bike tours, vineyards tours, wine cellar visits, parties, night visits, diners, work seminars |

| Categories and Subcategories | Theme | Number of References * |

|---|---|---|

| Activities Managerial consequences - Revenues/Profitability - Investments/costs - Human resources Motivations | Wine Tourism | 261 |

| Certifications - Tensions Biodiversity: - Practices - Definition - Investments - Incomes Values | Sustainability | 208 |

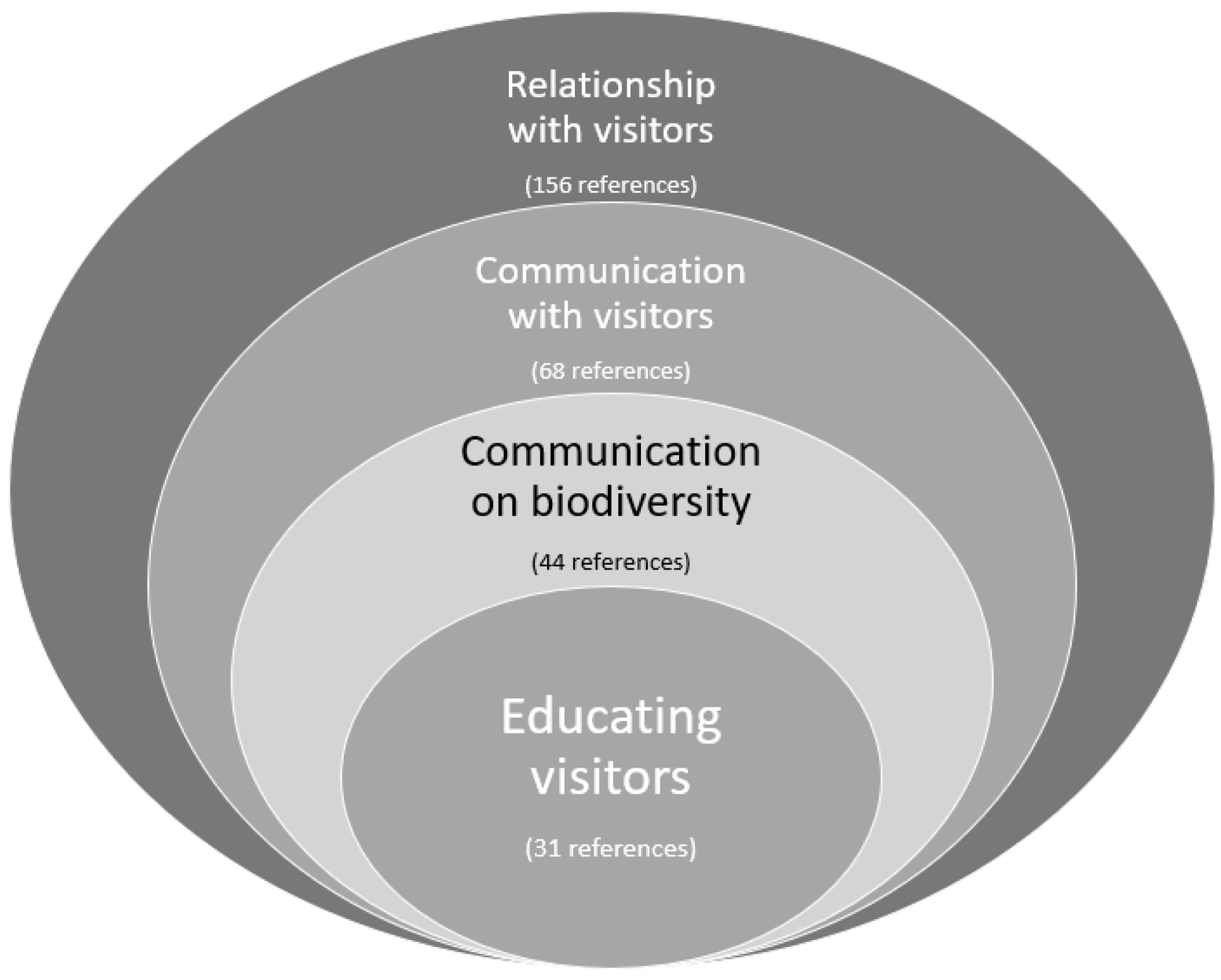

| Communication - Biodiversity communication - Educating visitors - Wine Tourism communication Attractiveness Visitor profile | Customer relationship | 156 |

| Synergies Tensions | Relations WT/Biodiversity | 75 |

| Eco-Labels | Official Source | Impact on Biodiversity | Methodology | Comments |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Terra Vitis | Certification website https://www.terravitis.com/ | 80 points of audit controlled every year (no specific criteria detailed). For biodiversity: development of living soils, maintenance of fences, forest, vegetal covers, limiting the treatments | Quantitative and qualitative indicators | The most demanding biodiversity certification with yearly audits of the species |

| HVE Haute Valeur Environnementale | French national agriculture website https://agriculture.gouv.fr/ | Sesquiannual biodiversity audit: insects, trees, hedges, grass strips, flowers… (no specific criteria detailed) | Quantitative and qualitative indicators | The second most demanding biodiversity certification with audits of the species every 18 month. |

| Vignerons Engagés | “vignerons engages” Certification website https://vignerons-engages.com/4-piliers-et-12-engagements/ | “Biodiversity diagnoses of the territories […] actions to protect endangered species, such as setting up beehives, insect hotels, or nesting boxes. […] multiply positive cultural practices for the life of the soil and for the creation and maintenance of animal and plant species […].” | Quantitative and qualitative indicators | Biodiversity is addressed by the variety of landscapes and the importance of sheltering the different species of livings. Frequency of diagnoses is not specified. |

| Demeter | Demeter website: https://www.demeter.fr/biodiversite-2/ | “10% of the useful agricultural surface of the farm is dedicated to areas of biodiversity” | Quantitative indicators | Biodiversity preservation does not concern the whole wine estate, it only applies to a percentage of the surface. |

| ISO 26000 | AFNOR (French Agency of norms) website https://bivi.afnor.org/ | Norm NF X32-001 Biodiversity audit, creation of indicators, measure and communication (no specific criteria detailed) | Quantitative indicators | The indicators are not specified on the official source and the process remains opaque. |

| European Organic label | French national agriculture website https://agriculture.gouv.fr/ | “Excludes the use of synthetic chemicals, GMOs and limits inputs.” | No indicators of biodiversity | Biodiversity per se is not addressed, only implied in the reduction of authorized chemicals and the interdiction to use GMOs. |

| Ecophyto | French national agriculture website https://www.mesdemarches.agriculture.gouv.fr/ | Certification of knowledge and use of phytosanitary products, no mention of biodiversity | No indicators of biodiversity | Biodiversity per se is not addressed, concerns only the optimization of phytosanitary treatment use. |

| Motivation | “Quotes” (Wine Estate ID Number cf. Table 1) |

|---|---|

| Increasing sales | “To boost the direct sale of wines, but also so that visitors come to the peninsula to discover our wines and eat at the restaurant.” (11) |

| Increasing number of visitors and customers | “We thought that wine tourism would bring people here and make us known, especially to locals”. “We want to develop wine tourism because we think it is important to be able to offer the most varied offer possible to attract new customers.” (9) “Our estate is suited for wine tourism and it would be a shame not to use it.” (5) “The goal was to develop our customer base” (14) “The [location] attracts nearly 200,000 visitors a year, […]. So we opened a wine shop and a restaurant which exclusively serves wines from the estate.” (11) |

| Reputation | “Bring people to our location” (7) “[We want to] organize a lot of events to increase our “popularity”” (1) “Our goal was to strengthen our reputation” (4) |

| CSR goals | “Wine tourism makes sense, it is not only about diversifying our offer, it meets our CSR ambition”, and “More than anything, wine tourism enables us to meet qualitative objectives in our CSR goals.” (6) |

| Presentation of the wines | “It allows us to present our wines in a festive way” and “It allows us to showcase our wines and the products of our restaurant” (1) “We also organized a Christmas market to present our wines.” (11) |

| Increasing their service range | “We want to develop wine tourism because we think it is important to be able to offer the most varied offer possible to attract new customers.” and “We want to develop wine tourism with the construction of accommodation on site: this would allow us to have a global offer.” (9) |

| Theme | Synergies | Tensions |

|---|---|---|

| Site attractiveness | “The attractiveness of a wine tourism site is strongly connected to the protection of biodiversity” (1) “The natural environment is really is an important element of a wine tourism offer” (2) | “[Our] wine cellar is located in a magnificent natural environment but it is rather isolated, so the access is quite difficult.” (13) “Mass tourism is a danger” (1) “The number of people must be limited, especially during vineyard visits.” (1) |

| New customers | “Preserving biodiversity can attract tourists who want to take part in environmental protection.” (11) “We are developing green activities to attract visitors who are sensitive to our cause, who will then become ambassadors for our domain.” (10) “People are more and more interested in [biodiversity], we can clearly see that.” (12) “In recent years visitors’ interest in environmental protection has increased I think visitors will become actors who are increasingly respectful of the environment.” (9) | “When we hold events, we invest in trash cans, but people are very disappointing. So, the next day, we pick up trash” (2) “It’s great to put trash cans and signage everywhere to educate visitors about protecting biodiversity, but honestly it depends on everyone’s good will! “(12). |

| Wine tourism activities | “For wine tourism, we would like to set up signs that provide information about wildlife, depending on the biodiversity diagnosis” (2) “, There are signs on the botanical trail to explain the interaction between the environment and the vines” (6). “We consider all our activities to be eco-friendly, including visits and tastings.” 10 | “We promote soft mobility: exploring the vineyard in a 4 × 4 would make no sense, handing out goodies from China at the end would be totally stupid too.” (11) “As soon as we create a new activity, we must try to have the minimum impact possible on the landscape and our environment: use clean materials, do not damage nature.” (9). |

| Communication | “Green wine tourism enables us to improve the image of agriculture: we show that our vineyard is also our home, and that there is no greenwashing.” (14) “It is not an activist wine tourism, it is rather a delicate, chilled, educational wine tourism. “(13) “Wine tourism allows us to explain our practices to people: how much detail we go into regarding procedures depends on their level of interest.” (8) | “People do not come to us because we do green wine tourism activities. We are not known for that, even if we are pioneers” (14). “It’s really focused on showcasing the wine, rather than showcasing the natural environment.” (2) “We are not here to teach people. It is difficult to constrain visitors. “(2) “[…] Manage to raise awareness while not transforming these protection procedures into constraints.” (7) |

| Values | “Protecting biodiversity gives meaning to wine tourism.” (6) | “Everyone wants to be called “green” but no one makes the effort and they prefer to stay in their comfort zone. Talking the talk is easy, but walking the walk is harder” (2) “Our activities are really based on entertainment, there is no special awareness-raising and accountability with regards to the environment. “(2) “You need to have an inner conviction, and to be able to financially support your convictions.”(13) |

| Alignment of | Biodiversity | Wine Tourism | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Exploitation | Exploration | Exploitation | Exploration | |

| Strategy | Protection of the natural environment | New practices i.e., agroforestry, implementing agro-ecology | Business diversification Development of the winery | Innovation supported by offering new activities |

| Asset | Increasing landscapes’ value | Making the vineyard more accessible | Natural landscape as an element of differentiation | Attracting eco-friendly tourists |

| Certification | Administrative cost Financial costs | Biodiversity audit | Sustainable activities: soft mobility, low carbon footprint | Towards a sustainable tourism recognition |

| Communication | Information of the public | Finding a balance between education and entertainment | Cross-industry network External communication | Customer loyalty |

| Company management | Optimizing human and financial resources | Staff training Fund raising | Dedicating human resources Investing in structures | Supporting innovation |

| Rewards | Encouraging wildlife’s development | Implementing biodiversity practices Increasing number of species Resisting better to global warming. | Increasing the number of visitors | New income streams and focus on increasing income |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Lamoureux, C.; Barbier, N.; Bouzdine-Chameeva, T. Managing Wine Tourism and Biodiversity: The Art of Ambidexterity for Sustainability. Sustainability 2022, 14, 15447. https://doi.org/10.3390/su142215447

Lamoureux C, Barbier N, Bouzdine-Chameeva T. Managing Wine Tourism and Biodiversity: The Art of Ambidexterity for Sustainability. Sustainability. 2022; 14(22):15447. https://doi.org/10.3390/su142215447

Chicago/Turabian StyleLamoureux, Claire, Nindu Barbier, and Tatiana Bouzdine-Chameeva. 2022. "Managing Wine Tourism and Biodiversity: The Art of Ambidexterity for Sustainability" Sustainability 14, no. 22: 15447. https://doi.org/10.3390/su142215447

APA StyleLamoureux, C., Barbier, N., & Bouzdine-Chameeva, T. (2022). Managing Wine Tourism and Biodiversity: The Art of Ambidexterity for Sustainability. Sustainability, 14(22), 15447. https://doi.org/10.3390/su142215447