Antecedents of Big Data Analytic Adoption and Impacts on Performance: Contingent Effect

Abstract

1. Introduction

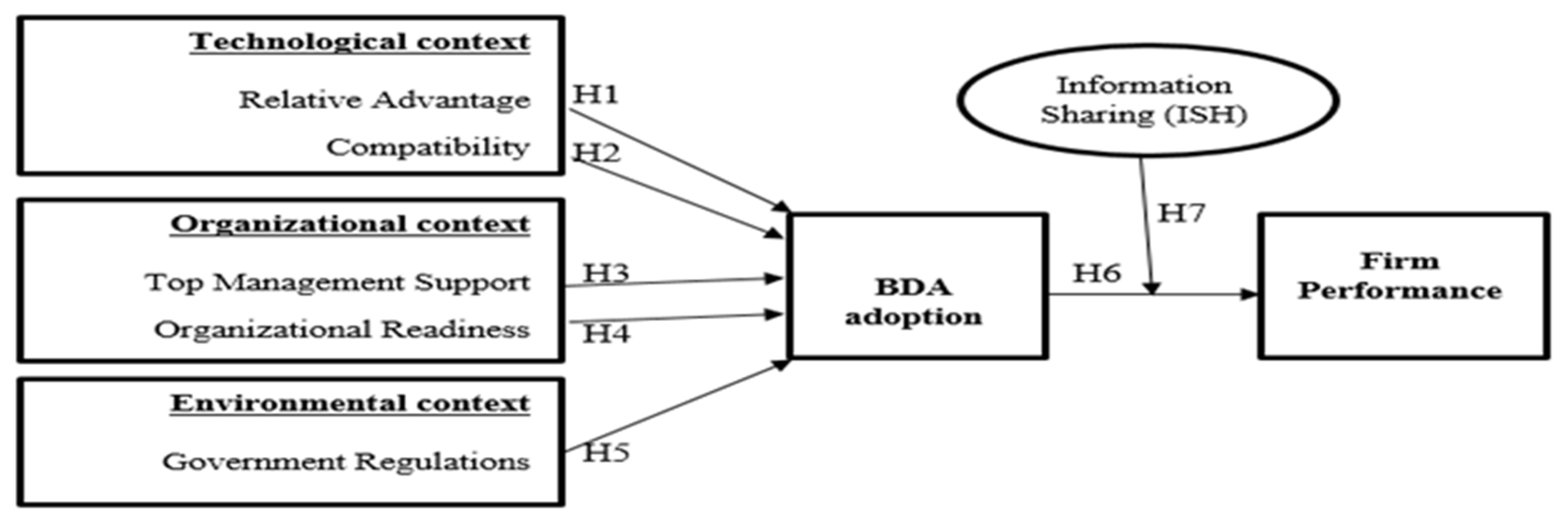

- To investigate the drivers of BDA adoption;

- To identify the effect of BDA adoption on firm performance; and

- To examine the moderating impact of information sharing on the association between BDA adoption and firm performance.

2. Literature Review

2.1. BDA Adoption in the Hotel Industry

2.2. Related Works

2.3. Theoretical Foundation

2.3.1. TOE Model

2.3.2. RBV

2.3.3. Integration of TOE and RBV

3. Research Framework and Hypotheses

3.1. Technological Context

3.2. Organisational Context

3.3. Environmental Context

3.4. BDA Adoption and Firm Performance

3.5. The Moderating Effect of Information sharing on the association between BDA adoption and Firm Performance

4. Methodology

5. Data Analysis

6. Results and Interpretation

6.1. Measurement Model Assessment

6.2. Assessment of the Structural Model

6.2.1. Direct Associations Models

6.2.2. The Moderation Association Model

7. Discussion and Conclusions

8. Contributions

8.1. Theoretical Contribution

8.2. Practical Contribution

9. Limitations and Future Studies

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| Measurement Items | Source |

| BDA adoption Our business intends to adopt BD Our business intends to start using BD in regular bases in the future Our business would highly recommend BD for others to adopt. | [96] |

| Relative advantage BDA improves the quality of work. BDA makes works more efficient. BDA lowers costs. BDA improves customer service. BDA attracts new sales to new customers or new markets. BDA adoption identifies new product/service opportunities. | [96] |

| Top Management Support Our top management promotes the use of BDA in the business. Our top management creates support for BDA initiatives within the business. Our top management promotes BDA as a strategic priority within the business. Our top Management is interested in the news about BDA adoption. | [96] |

| Organizational Readiness Lacking capital/financial resources has prevented my business from fully exploit BDA. Lacking needed IT infrastructure has prevented my business from exploiting BDA. Lacking analytics capability prevent the business fully exploit BDA. Lacking skilled resources prevent the business fully exploit BDA. | [96] |

| Government Regulations The governmental policies encourage our business to adopt new ITs (e.g., BDA). The government provides incentives for adopting BD in government procurements and contracts such as offering technical support, training, and funding for BD adoption. Standards or laws support adoption of BD technologies. Adequate legal protection supports BD technology adoption. There are some business laws to deal with the security and privacy concerns over the BD technologies. | [75] |

| Compatibility Using BDA is consistent with our business practices. Using BDA fits our organizational culture. Overall, it is easy to incorporate BDA into our business. | [96] |

| Information Sharing Our partners share proprietary information with us. We provide information to our partner that might help our partner. We provide information to our partner frequently and informally, and not only according to the specific agreement. | [97] |

| Firm Performance I believe that BDA can provide us with more accurate data. I believe that BDA can increase the profitability of my hotel. I believe that BDA can increase our financial performance. I believe that BDA can increase my hotels operational performance. | [98] |

References

- Lutfi, A.; Alrawad, M.; Alsyouf, A.; Almaiah, M.A.; Al-Khasawneh, A.; Al-Khasawneh, A.L.; Alshira’H, A.F.; Alshirah, M.H.; Saad, M.; Ibrahim, N. Drivers and impact of big data analytic adoption in the retail industry: A quantitative investigation applying structural equation modeling. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2023, 70, 103129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Staegemann, D.; Volk, M.; Lautenschlager, E.; Pohl, M.; Abdallah, M.; Turowski, K. Applying Test Driven Development in the Big Data Domain–Lessons From the Literature. In Proceedings of the 2021 International Conference on Information Technology (ICIT), Amman, Jordan, 14–15 July 2021; pp. 511–516. [Google Scholar]

- Jain, P.; Tambuskar, D.P.; Narwane, V. Identification of critical factors for big data analytics implementation in sustainable supply chain in emerging economies. J. Eng. Des. Technol. 2022. ahead-of-print. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rayburn, S.W.; Anderson, S.T.; Zank, G.M.; McDonald, I. M-atmospherics: From the physical to the digital. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2022, 64, 102782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wahab, S.N.; Hamzah, M.I.; Sayuti, N.M.; Lee, W.C.; Tan, S.Y. Big data analytics adoption: An empirical study in the Malaysian warehousing sector. Int. J. Logist. Syst. Manag. 2021, 40, 121–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baig, M.I.; Shuib, L.; Yadegaridehkordi, E. A Model for Decision-Makers’ Adoption of Big Data in the Education Sector. Sustainability 2021, 13, 13995. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alsmadi, A.A.; Alzoubi, M. Green Economy: Bibliometric Analysis Approach. Int. J. Energy Econ. Policy 2022, 12, 282–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Volk, M.; Staegemann, D.; Trifonova, I.; Bosse, S.; Turowski, K. Identifying Similarities of Big Data Projects–A Use Case Driven Approach. IEEE Access 2020, 8, 186599–186619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mikalef, P.; Boura, M.; Lekakos, G.; Krogstie, J. Big data analytics and firm performance: Findings from a mixed-method approach. J. Bus. Res. 2019, 98, 261–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- International Data Corporation (IDC) (2020): Worldwide Big Data and Analytics Software Forecast, 2021–2026. Available online: https://www.reportlinker.com/p06166758/Big-Data-Business-Analytics-Market-Research-Report-by-Analytics-Tools-by-Component-by-Deployment-Mode-by-Application-by-End-User (accessed on 3 September 2022).

- Choi, H.S.; Hung, S.Y.; Peng, C.Y.; Chen, C. Different Perspectives on BDA Usage by Management Levels. J. Comput. Inf. Syst. 2021, 62, 503–515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nam, D.; Lee, J.; Lee, H. Business analytics adoption process: An innovation diffusion perspective. Int. J. Inf. Manag. 2019, 49, 411–423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Youssef MA, E.A.; Eid, R.; Agag, G. Cross-national differences in big data analytics adoption in the retail industry. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2022, 64, 102827. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aversa, J.; Hernandez, T.; Doherty, S. Incorporating big data within retail organizations: A case study approach. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2021, 60, 102447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghasemaghaei, M. Are firms ready to use big data analytics to create value? The role of structural and psychological readiness. Enterp. Inf. Syst. 2019, 13, 650–674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raguseo, E.; Vitari, C. Investments in big data analytics and firm performance: An empirical investigation of direct and mediating effects. Int. J. Prod. Res. 2018, 56, 5206–5221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perdana, A.; Lee, H.H.; Koh, S.; Arisandi, D. Data analytics in small and mid-size enterprises: Enablers and inhibitors for business value and firm performance. Int. J. Account. Inf. Syst. 2022, 44, 100547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cabrera-Sánchez, J.P.; Villarejo-Ramos, Á.F. Acceptance and use of big data techniques in services companies. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2020, 52, 101888. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Sai, Z.A.; Abdullah, R.; Husin, M.H. Critical success factors for big data: A systematic literature review. IEEE Access 2020, 8, 118940–118956. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Munawar, H.S.; Qayyum, S.; Ullah, F.; Sepasgozar, S. Big data and its applications in smart real estate and the disaster management life cycle: A systematic analysis. Big Data Cogn. Comput. 2020, 4, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chandra, S.; Kumar, K.N. Exploring factors influencing organizational adoption of augmented reality in e-commerce: Empirical analysis using technology-organization- environment model. J. Electron. Commer. Res. 2018, 19, 237–265. [Google Scholar]

- Maroufkhani, P.; Wagner, R.; Wan Ismail, W.K.; Baroto, M.B.; Nourani, M. Big data analytics and firm performance: A systematic review. Information 2019, 10, 226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, Z. Investigating information processing paradigm to predict performance in emerging firms: The mediating role of technological innovation. J. Bus. Ind. Mark. 2022. ahead-of-print. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lutfi, A.; Saad, M.; Almaiah, M.A.; Alsaad, A.; Al-Khasawneh, A.; Alrawad, M.; Alsyouf, A.; Al-Khasawneh, A.L. Actual use of mobile learning technologies during social distancing circumstances: Case study of King Faisal University students. Sustainability 2022, 14, 7323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, Z.; Gongbing, B.; Mehreen, A. Supply chain network and information sharing effects of SMEs credit quality on firm performance: Do strong tie and bridge tie matter? J. Enterp. Inf. Manag. 2019, 32, 714–734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akter, S.; Fosso Wamba, S.; Dewan, S. Why PLS-SEM is suitable for complex modelling? An empirical illustration in big data analytics quality. Prod. Plan. Control 2017, 28, 1011–1021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barlette, Y.; Baillette, P. Big data analytics in turbulent contexts: Towards organizational change for enhanced agility. Prod. Plan. Control 2022, 33, 105–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saleem, H.; Li, Y.; Ali, Z.; Mehreen, A.; Mansoor, M.S. Mansoor. An Empirical Investigation on How Big Data Analytics Influence China SMEs Performance: Do Product and Process Innovation Matter? Asia Pac. Bus. Rev. 2020, 26, 537–562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roaimah, O.; Ramayah, T.; May-Chuin, L.; Tan, Y.S.; Rusinah, S. Information sharing, information quality and usage of information technology (IT) tools in Malaysian organizations. Afr. J. Bus. Manag. 2010, 4, 2486–2499. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Y.; Ali, Z. Exploring big data use to predict supply chain effectiveness in Chinese organizations: A moderated mediated model link. Asia Pac. Bus. Rev. 2021, 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; Zheng, Y.; Xie, G.; Tian, Y. The Influence Mechanism of Strategic Partnership on Enterprise Performance: Exploring the Chain Mediating Role of Information Sharing and Supply Chain Flexibility. Sustainability 2022, 14, 4800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alzoubi RH, M.; Jaaffar, A.H. Leadership styles, crisis management, and hotel performance: A conceptual perspective of the Jordanian hotel industry. J. Crit. Rev. 2020, 7, 556–562. [Google Scholar]

- MOTA. Statistical Bulletins. 2016. Available online: http://www.mota.gov.j (accessed on 25 August 2022).

- Yadegaridehkordi, E.; Nilashi, M.; Shuib, L.; Nasir MH NB, M.; Asadi, S.; Samad, S.; Awang, N.F. The impact of big data on firm performance in hotel industry. Electron. Commer. Res. Appl. 2020, 40, 100921. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Samara, D.; Magnisalis, I.; Peristeras, V. Artificial intelligence and big data in tourism: A systematic literature review. J. Hosp. Tour. Technol. 2020, 11, 343–367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiang, Z.; Schwartz, Z.; Gerdes, J.H., Jr.; Uysal, M. What can big data and text analytics tell us about hotel guest experience and satisfaction? Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2015, 44, 120–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, J.-H.; Kim, M.-K.; Paik, J.-H. The Factors of Technology, Organization and Environment Influencing the Adoption and Usage of Big Data in Korean Firms. In Proceedings of the 26th European Regional Conference of the International Telecommunications Society (ITS): “What Next for European Telecommunications?”, Madrid, Spain, 24–27 June 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Skafi, M.; Yunis, M.M.; Zekri, A. Factors influencing SMEs’ adoption of cloud computing services in lebanon: An empirical analysis using toe and contextual theory. IEEE Access 2020, 13, 79169–79181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ajimoko, O.J. Considerations for the Adoption of Cloud-based Big Data Analytics in Small Business Enterprises. Electron. J. Inf. Syst. Eval. 2018, 21, 63–79. [Google Scholar]

- Parson, G.K. Factors Affecting Information Technology Professionals’ Decisions to Adopt Big Data Analytics Among Small-and Medium-Sized Enterprises: A Quantitative Study. Doctoral Dissertation, Capella University, Minneapolis, MN, USA, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Mangla, S.K.; Raut, R.; Narwane, V.S.; Zhang, Z.J. Mediating effect of big data analytics on project performance of small and medium enterprises. J. Enterp. Inf. Manag. 2020, 34, 168–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nasrollahi, M.; Ramezani, J.; Sadraei, M. The Impact of Big Data Adoption on SMEs’ Performance. Big Data Cogn. Comput. 2021, 5, 68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maroufkhani, P.; Ismail WK, W.; Ghobakhloo, M. Big data analytics adoption model for small and medium enterprises. J. Sci. Technol. Policy Manag. 2020, 11, 483–513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loh, C.H.; Teoh, A.P. The Adoption of Big Data Analytics Among Manufacturing Small and Medium Enterprises During COVID-19 Crisis in Malaysia. In Proceedings of the Ninth International Conference on Entrepreneurship and Business Management (ICEBM 2020), 9 May 2021; Atlantis Press: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2021; pp. 95–100. [Google Scholar]

- Mikalef, P.; Krogstie, J.; Pappas, I.O.; Pavlou, P. Exploring the relationship between big data analytics capability and competitive performance: The mediating roles of dynamic and operational capabilities. Inf. Manag. 2020, 57, 103169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wamba, S.F.; Gunasekaran, A.; Akter, S.; Ren, S.J.; Dubey, R.; Childe, S.J. Big data analytics and firm performance: Effects of dynamic capabilities. J. Bus. Res. 2017, 70, 356–365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mikalef, P.; Pappas, I.O.; Krogstie, J.; Giannakos, M. Big data analytics capabilities: A systematic literature review and research agenda. Inf. Syst. E-Bus. Manag. 2018, 16, 547–578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rajabion, L.; Shaltooki, A.A.; Taghikhah, M.; Ghasemi, A.; Badfar, A. Healthcare big data processing mechanisms: The role of cloud computing. Int. J. Inf. Manag. 2019, 49, 271–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Kung, L.; Wang, W.Y.C.; Cegielski, C.G. An Integrated Big Data Analytics-Enabled Transformation Model: Application to Health Care. Inf. Manag. 2017, 55, 64–79. Available online: http://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0378720617303129 (accessed on 3 September 2022). [CrossRef]

- Zhu, K.; Kraemer, K.L.; Xu, S. The process of innovation assimilation by firms in different countries: A technology diffusion perspective on e-business. Manag. Sci. 2006, 52, 1557–1576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoon, T.E.; George, J.F. Why aren’t organizations adopting virtual worlds? Comput. Hum. Behav. 2013, 29, 772–790. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsu, P.F.; Kraemer, K.L.; Dunkle, D. Determinants of e-business use in US firms. Int. J. Electron. Commer. 2006, 10, 9–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barney, J. Firm resources and sustained competitive advantage. J. Manag. 1991, 17, 99–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wade, M.; Hulland, J. Review: The resource-based view and information systems research: Review, extension, and suggestion for future research. MIS Quart. 2004, 28, 107–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghasemaghaei, M.; Ebrahimi, S.; Hassanein, K. Data analytics competency for improving firm decision making performance. J. Strateg. Inf. Syst. 2017, 27, 101–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghasemaghaei, M. Understanding the impact of big data on firm performance: The necessity of conceptually differentiating among big data characteristics. Int. J. Inf. Manag. 2021, 57, 102055. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bharadwaj, S.; Bharadwaj, A.; Bendoly, E. The performance effects of complementarities between information systems, marketing, manufacturing, and supply chain processes. Inf. Syst. Res. 2007, 18, 437–453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, D.Q.; Preston, D.S.; Swink, M. How the use of big data analytics affects value creation in supply chain management. J. Manag. Inf. Syst. 2015, 32, 4–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barua, A.; Konana, P.; Whinston, A.B.; Yin, F. An empirical investigation of net-enabled business value. MIS Q. 2004, 28, 585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Banker, R.D.; Bardhan, I.R.; Chang, H.; Lin, S. Plant information systems, manufacturing capabilities, and plant performance. MIS Q. 2006, 30, 315–337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhatt, G.D.; Grover, V. Types of information technology capabilities and their role in competitive advantage: An empirical study. J. Manag. Inf. Syst. 2005, 22, 253–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fink, L.; Neumann, S. Taking the high road to web services implementation: An exploratory investigation of the organizational impacts. ACM SIGMIS Database DATABASE Adv. Inf. Syst. 2009, 40, 84–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, M.; George, J.F. Toward the development of a big data analytics capability. Inf. Manag. 2016, 53, 1049–1064. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abbasi, A.; Sarker, S.; Chiang, R.H. Big data research in information systems: Toward an inclusive research agenda. J. Assoc. Inf. Syst. 2016, 17, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tornatzky, L.; Fleischer, M. The Process of Technology Innovation; Lexington Books: Lexington, MA, USA, 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Rogers, E.M. Diffusion of Innovations, 5th ed.; Free Press: New York, NY, USA, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Alsmadi, A.A.; Al-Gasaymeh, A.; Alrawashdeh, N. Purchasing Power Parity: A Bibliometric approach for the period of 1935-2021. Qual.—Access Success 2022, 23, 260–269. [Google Scholar]

- Almaiah, M.A.; Al Mulhem, A. Thematic analysis for classifying the main challenges and factors influencing the successful implementation of e-learning system using NVivo. Int. J. Adv. Trends Comput. Sci. Eng. 2020, 9, 142–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almaiah, M.A.; Al-Otaibi, S.; Lutfi, A.; Almomani, O.; Awajan, A.; Alsaaidah, A.; Alrawad, M.; Awad, A.B. Employing the TAM Model to Investigate the Readiness of M-Learning System Usage Using SEM Technique. Electronics 2022, 11, 1259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lutfi, A. Understanding Cloud Based Enterprise Resource Planning Adoption among SMEs in Jordan. J. Theor. Appl. Inf. Technol. 2021, 99, 5944–5953. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lutfi, A. Factors Influencing the Continuance Intention to Use Accounting Information System in Jordanian SMEs from the Perspectives of UTAUT: Top Management Support and Self-Efficacy as Predictor Factors. Economies 2022, 10, 75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsu, C.H.; Li, M.G.; Zhang, T.Y.; Chang, A.Y.; Shangguan, S.Z.; Liu, W.L. Deploying Big Data Enablers to Strengthen Supply Chain Resilience to Mitigate Sustainable Risks Based on Integrated HOQ-MCDM Framework. Mathematics 2022, 10, 1233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lai, Y.; Sun, H.; Ren, J. Understanding the determinants of big data analytics (BDA) adoption in logistics and supply chain management: An empirical investigation. Int. J. Logist. Manag. 2018, 29, 676–703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almaiah, M.A.; Hajjej, F.; Lutfi, A.; Al-Khasawneh, A.; Shehab, R.; Al-Otaibi, S.; Alrawad, M. Explaining the Factors Affecting Students’ Attitudes to Using Online Learning (Madrasati Platform) during COVID-19. Electronics 2022, 11, 973. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alsmadi, A.A.; Oudat, M.S.; Hasan, H. Islamic finance value versus conventional finance, dynamic equilibrium relationships analysis with macroeconomic variables in the jordanian economy: An ardl approach. Chang. Manag. 2020, 130, 1–14. [Google Scholar]

- Božič, K.; Dimovski, V. Business intelligence and analytics for value creation: The role of absorptive capacity. Int. J. Inf. Manag. 2019, 46, 93–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bianchini, M.; Michalkova, V. Data Analytics in SMEs: Trends and Policies. OECD SME Entrep. Pap. 2019, 3, 1–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, A.; Yusof, S.A.M.; Oroumchian, F. Understanding the Business Value Creation Process for Business Intelligence Tools in the UAE. Pac. Asia J. Assoc. Inf. Syst. 2019, 11, 214–247. [Google Scholar]

- Almaiah, M.A.; Ayouni, S.; Hajjej, F.; Lutfi, A.; Almomani, O.; Awad, A.B. Smart Mobile Learning Success Model for Higher Educational Institutions in the Context of the COVID-19 Pandemic. Electronics 2022, 11, 1278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El-Haddadeh, R.; Osmani, M.; Hindi, N.; Fadlalla, A. Value creation for realising the sustainable development goals: Fostering organisational adoption of big data analytics. J. Bus. Res. 2021, 131, 402–410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S.; Rao, S.S.; Ragu-Nathan, T.S.; Ragu-Nathan, B. Development and validation of a measurement instrument for studying supply chain management practices. J. Oper. Manag. 2005, 23, 618–641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheko, A.; Braimllari, A. Information technology inhibitors and information quality in supply chain management: A PLS-SEM analysis. Acad. J. Interdiscip. Stud. 2018, 7, 125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, H.H.; Wong, K.H.; Chiu, W.S. The effects of business systems leveraging on supply chain performance: Process innovation and uncertainty as moderators. Inf. Manag. 2019, 56, 103140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsai, W.C. Determinants and consequences of employee displayed positive emotions. J. Manag. 2001, 27, 497–512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaworski, B.J.; Kohli, A.K. Market orientation: Antecedents and consequences. J. Mark. 1993, 57, 53–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, S.; Ke, W.; Liu, H.; Wei, K.K. Supply chain information integration and firm performance: Are explorative and exploitative IT capabilities complementary or substitutive? Decis. Sci. 2019, 51, 464–499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheu, C.; Rebecca Yen, H.; Chae, B. Determinants of supplier-retailer collaboration: Evidence from an international study. Int. J. Oper. Prod. Manag. 2006, 26, 24–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almaiah, M.A.; Hajjej, F.; Lutfi, A.; Al-Khasawneh, A.; Alkhdour, T.; Almomani, O.; Shehab, R. A Conceptual Framework for Determining Quality Requirements for Mobile Learning Applications Using Delphi Method. Electronics 2022, 11, 788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nath, S.D.; Khayer, A.; Majumder, J.; Barua, S. Factors affecting blockchain adoption in apparel supply chains: Does sustainability-oriented supplier development play a moderating role? Ind. Manag. Data Syst. 2022. ahead-of-print. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Podrug, N.; Filipović, D.; Kovač, M. Knowledge sharing and firm innovation capability in Croatian ICT companies. Int. J. Manpow. 2017, 38, 632–644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dwivedi, M.; Laddha, N.C.; Arora, P.; Marfatia, Y.S.; Begum, R. Decreased regulatory T-cells and CD4+/CD8+ ratio correlate with disease onset and progression in patients with generalized vitiligo. Pigment Cell Melanoma Res. 2013, 26, 586–591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, J.F.; Risher, J.J.; Sarstedt, M.; Ringle, C.M. When to use and how to report the results of PLS-SEM. Eur. Bus. Rev. 2019, 31, 2–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tu, M. An exploratory study of Internet of things (IoT) adoption intention in logistics and supply chain management. Int. J. Logist. Manag. 2018, 29, 131–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maroufkhani, P.; Tseng, M.L.; Iranmanesh, M.; Ismail, W.K.; Khalid, H. Big data analytics adoption: Determinants and performances among small to medium-sized enterprises. Int. J. Inf. Manag. 2020, 54, 102190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, J.H. Inter-organizational relationships and information sharing in supply chains. Int. J. Inf. Manag. 2011, 31, 374–384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garrison, G.; Wakefield, R.L.; Kim, S. The effects of IT capabilities and delivery model on cloud computing success and firm performance for cloud supported processes and operations. Int. J. Inf. Manag. 2015, 35, 377–393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garrido-Moreno, A.; Padilla-Meléndez, A. Analyzing the impact of knowledge management on CRM success: The mediating effects of organizational factors. Int. J. Inf. Manag. 2011, 31, 437–444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laitinen, E.K. Influence of cost accounting change on performance of manufacturing firms. Adv. Account. 2014, 30, 230–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeglat, D.; Zigan, K. Intellectual capital and its impact on business performance: Evidences from the Jordanian hotel industry. Hotel. Hosp. Res. 2014, 13, 83–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- King, W.R.; He, J. External validity in IS survey research. Commun. Assoc. Inf. Syst. 2005, 16, 45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alsharif, A.H.; Salleh NZ, M.; Baharun, R.; Abuhassna, H.; Alsharif, Y.H. Neuromarketing in Malaysia: Challenges, limitations, and solutions. In Proceedings of the 2022 International Conference on Decision Aid Sciences and Applications (DASA), Chiangrai, Thailand, 23–25 March 2022; pp. 740–745. [Google Scholar]

- Alsharif, A.H.; Salleh, N.Z.M.; Baharun, R.; Hashem, E.A.R.; Mansor, A.A.; Ali, J.; Abbas, A.F. Neuroimaging Techniques in Advertising Research: Main Applications, Development, and Brain Regions and Processes. Sustainability 2021, 13, 6488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fornell, C.; Larcker, D.F. Evaluating structural equation models with unobservable variables and measurement error. J. Mark. Res. 1981, 18, 39–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hameed, M.A.; Counsell, S. Assessing the influence of environmental and CEO characteristics for adoption of Information Technology in organizations. J. Technol. Manag. Innov. 2012, 7, 64–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lutfi, A. Investigating the moderating effect of Environment Uncertainty on the relationship between institutional factors and ERP adoption among Jordanian SMEs. J. Open Innov. Technol. Mark. Complex. 2020, 6, 91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saleem, H.; Li, Y.; Ali, Z.; Ayyoub, M.; Wang, Y.; Mehreen, A. Big Data Use and Its Outcomes in Supply Chain Context: The Roles of Information Sharing and Technological Innovation. J. Enterp. Inf. Manag. 2020, 34, 1121–1143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grover, V.; Chiang, R.H.; Liang, T.-P.; Zhang, D. Creating strategic business value from big data analytics: A research framework. J. Manag. Inf. Syst. 2018, 35, 388–423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rivera, M.A. Big data research in hospitality: From streetlight empiricism research to theory laden research. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2020, 86, 102447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Construct | Cronbach’s Alpha | Composite Reliability | AVE |

|---|---|---|---|

| >0.7 | >0.7 | >0.5 | |

| Firm performance (FP) | 0.837 | 0.879 | 0.553 |

| BDA adoption (BDA A) | 0.720 | 0.826 | 0.545 |

| Relative advantage | 0.829 | 0.874 | 0.541 |

| Compatibility | 0.721 | 0.835 | 0.631 |

| Top management support | 0.849 | 0.894 | 0.627 |

| Organisational readiness | 0.851 | 0.893 | 0.628 |

| Information sharing | 0.772 | 0.845 | 0.538 |

| Government regulations | 0.809 | 0.866 | 0.523 |

| FP | BDAA | RA | CP | CO | GS | TMS | OR | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Firm performance | 0.753 | |||||||

| BDA adoption (BDA A) | 0.383 | 0.748 | ||||||

| Relative advantage (RA) | 0.451 | 0.347 | 0.784 | |||||

| Information sharing (ISH) | 0.288 | 0.386 | 0.317 | 0.743 | ||||

| Compatibility (CO) | 0.261 | 0.371 | 0.211 | 0.305 | 0.838 | |||

| Government regulations (GRs) | 0.146 | 0.160 | 0.196 | 0.025 | 0.128 | 0.733 | ||

| TMS | 0.372 | 0.306 | 0.247 | 0.659 | 0.280 | 0.088 | 0.842 | |

| Organisational readiness (OR) | 0.086 | 0.277 | 0.165 | 0.425 | 0.603 | 0.061 | 0.293 | 0.783 |

| Hypothesis | Relationship | Path coefficient | T-Value | p-Value | Decision |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| H1 | Relative advantage → BDA A | 0.096 | 1.460 | 0.089 * | Supported |

| H2 | Compatibility → BDA A | 0.009 | 0.110 | 0.457 | Rejected |

| H3 | Top management support → BDA A | 0.194 | 2.588 | 0.013 ** | Supported |

| H4 | Organisational readiness → BDA A | 0.128 | 1.826 | 0.047 ** | Supported |

| H5 | Government regulations → BDA A | 0.205 | 2.131 | 0.031 ** | Supported |

| H6 | BDA adoption → firm performance | 0.383 | 6.977 | 0.000 *** | Supported |

| Hyp No. | Relation | Path Coeffi | T- Value | p- Value | Result |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| H7 | BDA * ISH → FP | 0.088 | 1.395 | 0.092 | Supported |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Lutfi, A.; Al-Khasawneh, A.L.; Almaiah, M.A.; Alshira’h, A.F.; Alshirah, M.H.; Alsyouf, A.; Alrawad, M.; Al-Khasawneh, A.; Saad, M.; Ali, R.A. Antecedents of Big Data Analytic Adoption and Impacts on Performance: Contingent Effect. Sustainability 2022, 14, 15516. https://doi.org/10.3390/su142315516

Lutfi A, Al-Khasawneh AL, Almaiah MA, Alshira’h AF, Alshirah MH, Alsyouf A, Alrawad M, Al-Khasawneh A, Saad M, Ali RA. Antecedents of Big Data Analytic Adoption and Impacts on Performance: Contingent Effect. Sustainability. 2022; 14(23):15516. https://doi.org/10.3390/su142315516

Chicago/Turabian StyleLutfi, Abdalwali, Akif Lutfi Al-Khasawneh, Mohammed Amin Almaiah, Ahmad Farhan Alshira’h, Malek Hamed Alshirah, Adi Alsyouf, Mahmaod Alrawad, Ahmad Al-Khasawneh, Mohamed Saad, and Rommel Al Ali. 2022. "Antecedents of Big Data Analytic Adoption and Impacts on Performance: Contingent Effect" Sustainability 14, no. 23: 15516. https://doi.org/10.3390/su142315516

APA StyleLutfi, A., Al-Khasawneh, A. L., Almaiah, M. A., Alshira’h, A. F., Alshirah, M. H., Alsyouf, A., Alrawad, M., Al-Khasawneh, A., Saad, M., & Ali, R. A. (2022). Antecedents of Big Data Analytic Adoption and Impacts on Performance: Contingent Effect. Sustainability, 14(23), 15516. https://doi.org/10.3390/su142315516

_Li.png)