1. Problem of Scale

The need and desire to achieve ambitious plans collectively, to make and execute large-scale plans jointly but as if they were owned by each of us, is, in fact, the old “problem of scale” discussed by Plato and Aristotle, and later by modern theorists of democracy [

1,

2,

3]. According to Kevin Lynch, in the field of urban planning, this question has become the “great-grandfather” of all other urban difficulties [

4], p. 239. Just as democracy in its pure form seems to be impossible on a large scale [

1], so too no idea of the ideal polis has ever provided for a truly large-scale settlement [

5].

The paradoxical nature of large-scale but citizen-driven urban planning has been best exemplified by the famous words of Daniel Burnham, author of the 1909 Plan of Chicago: “Make no little plans. They have no magic to stir men’s blood and probably will not themselves be realized. Make big plans” [

6], p. 61. On the one hand, large-scale planning endeavors could have been blood-stirring narratives capable of solving shared problems and strengthening communities, and as such considered supreme manifestations of democratic values. On the other hand, what followed them has often been more harmful [

7], even more disastrous [

8] than not having them at all. These authoritarian ideas eventually stirred men’s blood, indeed, not in support, however, but in strong opposition [

9]. Although we still succumb to the irresistible allure of grand visions, today people have become cynical and reluctant about large-scale planning instruments [

10,

11]—understandably, but not quite fairly, according to Alexander Garvin [

10].

In result, large-scale urban development remains the purview of governments and large corporations while empowering civic participation within the urban planning process is exercised in planning on a small scale. Camilla Ween argues that such a bipolar arrangement is the only possible way to deal with future challenges, because only the top-down approach guarantees order and the timely delivery of solutions, while communities acting from the bottom-up should just be given a chance to contribute to the process so that they can “have some control over their destiny” [

12], p. 88. Sławomir Gzell describes the same dichotomy as the best possible planning approach; he writes explicitly about a “compromise” between top-down authorities deciding on strategic plans, and citizens being involved from the bottom-up (only!) in putting the plans into practice [

13]. According to Jacqueline Leavitt and Ayse Yonder, the compromise is rooted deeply in the general condition of the urban planning profession [

14]. Krzysztof Nawratek—who also distinguishes between two models of city management: an expert model that is largely authoritarian, and a community model—points out that whenever we mention planning that is citizen-driven and grassroots, we unwittingly refer to the phenomenon of locality [

15]. In addition, in summarizing the history of planning through the lens of planning theory, no matter whether it is regarding physical, rational, or communicative planning theories, Ioannis Pissourios concludes that citizen involvement is possible only within a bipolar configuration, in which “regional and strategic urban planning scale should be ascribed to top-down approaches, while local urban planning scale to bottom-up approaches” [

16], p. 96.

It is hard to even imagine ways in whcih such a division could be overcome, since we know no better city-management tool than traditional hierarchical structures, and although we are critical about them, we have no alternative whatsoever [

17]. According to Erik Swyngedouw, recent experiments with social innovation in planning have revealed that even though new urban governance arrangements are supposed to be constructed freely and horizontally, the emerging choreographies of participating holders are strictly dependent on the scale of the planning enterprise [

18]. Such governance choreographies are here conceptualized through the scale compromise concept. The paper argues that such a compromise has been tacitly but widely accepted as it complements the hierarchical management structure, which remains the de rigueur policy framework for any sort of citizen involvement in urban planning processes, save for insurgent or radical attempts [

19,

20]. In most cases, the two opposite models exist concurrently but separately: a “professional” model adequate for large-scale urban areas, and a “self-determination” model adequate for small towns or particular urban enclaves. Sticking to this division might be even seen as desirable as it avoids uncontrollable “jumping scales” (down- or up-scaling) and the related lack of transparency and sustainability of planning procedures, among other reasons [

18].

Nevertheless, this type of scale compromise, according to which the scale of civic involvement in planning issues is rigidly constrained in advance, should be recognized as harmful and destructive to public life. Eventually, the compromise disempowers citizens not only at the large scale, but at any scale, since every activity is to be “organized and run from the top down” [

21], p. 425. According to Richard Sennett, it deprives the citizens of their right to the city as a whole and constitutes a new form of domination [

22]. In this manner, the citizens find themselves pushed into a “communitarian trap” [

23]. Standard participation procedures allow for nothing more than “cosmetic changes” [

21], p. 425. This is what Markus Miessen calls the “nightmare of participation,” in which the citizens deliberate endlessly on irrelevant details, while all the key decisions—the large-scale and strategic ones—are authority-led with no transparency or any civic control at all [

24]. Sticking to the scale compromise seems like taking for granted that “there are no alternatives to the grand narrative” and that “the critique of power can only be done parasitically, and in some form of subservience” [

25], p. 60.

If civic involvement is to be anything more than just “fine-tuning” [

26], pp. 244–245, it must be capable of setting up and redefining large-scale, strategic plans, which, according to Patsy Healey, are the very heartland of planning culture: “It is here that the coordinative and future-oriented qualities of planning as a style of governance are most visible” [

26], p. 248. Therefore, small-scale bottom-up initiatives should be seen as at least “urban catalysts” and be given a chance to scale up their effects [

27]. “Tactical urbanism,” which is short-term and small-scale by definition, might be efficient and sustainable only when “breaking through the gridlock of what we call the Big Planning process (…) while never losing sight of long-term and large-scale goals” [

28], p. 4.

Civic involvement within large-scale planning issues remains of the utmost importance: “This is not so much a critique as a warning of the dangers of missing the larger picture or completely abandoning a vision of a larger order that may ensure the survival of scaled-down tactics” [

25], p. 60. Hopefully, future attempts will demonstrate that going back to large-scale planning does not necessarily mean going back to old-fashioned practices [

29], and that large-scale urban planning is a task that can be successfully carried out by dedicated agencies, possibly of a firm civic-based structure [

30]. While refraining from large-scale planning issues would be devastating for both large-scale and small-scale participatory culture, broadening the influence of citizens beyond small, local interventions, plans, and adjustments is a must: it is a challenge as important to the future of cities as it is for the citizens themselves.

2. Scale Compromise

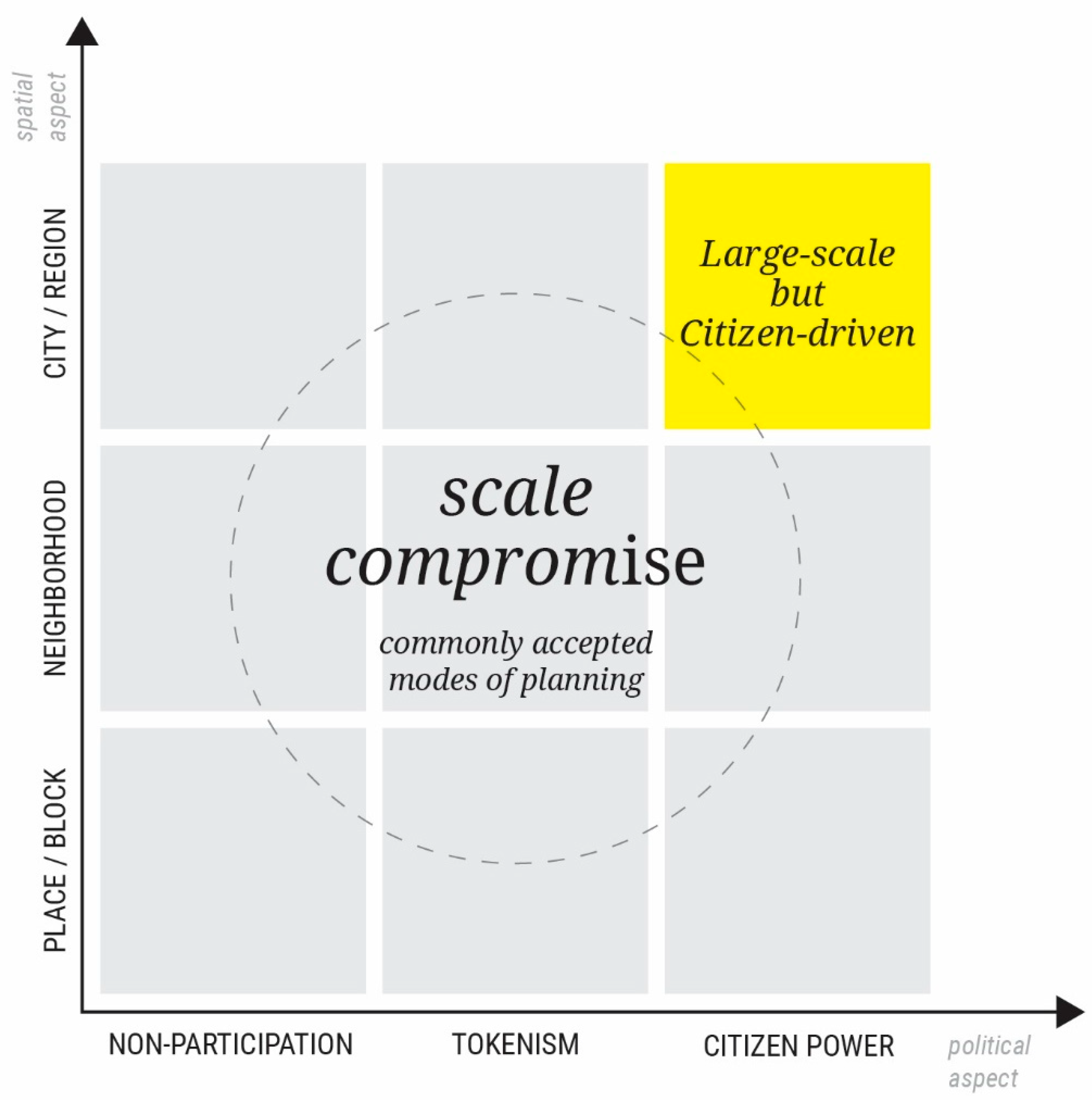

The scale compromise touches on two essential dimensions of urban planning: spatial (large vs. local scale) and political (citizen-driven vs. authority-led) (see

Figure 1). The spatial dimension (vertical axis) is associated with the scale of physical planning and answers the following questions: where? what? and how much? This paper does not associate “large-scale” with any particular planning instrument, but refers to the universal characteristics of complexity and comprehensiveness [

31]—to plans that are supralocal and cross-boundary, that is, most often of a city-wide or regional scale (plans that address various historical identities, land-uses, and communities, that undertake significant environmental, infrastructural, or socio-economic challenges, and that involve diverse stakeholders), in contrast to plans of an intermediary (district, neighborhood) or local (block, site) scale. On the other hand, the political dimension (horizontal axis) is associated with the process of planning and answers the following questions: why? who? and how? Instead of referring to any specific participatory method or tool, the divisions here reflect the universal “ladder of civic participation” [

32] in which the highest level—citizen power—involves a partnership, sharing of responsibility, or even taking control by citizens, in contrast to the lower rungs: tokenism and non-participation. Since the main goal of the paper is not to evaluate the results of citizen-driven approach to planning, but to examine its scale-related limitations, the “ladder” has been employed in its basic form without critique of its highest rungs, which will appear later in the text [

33].

This paper avoids simply juxtaposing “top-down” and “bottom-up” planning approaches, a distinction already examined by researchers [

16], although of questionable cognitive utility regarding today’s complex governance structures [

34,

35]. Instead, terms “authority-led” and “citizen-driven” are employed as marking two separate approaches to urban planning: the former associated with professionalism, bureaucracy, and hegemony, whilst the latter associated with amateurism, informality, and citizenship [

36]. According to Andy Merrifield, these two approaches reveal a fundamental distinction between Haussmann’s grand planning legacy and Debord’s locally rooted urbanism [

37]. In this paper, the first approach is presented as focused on providing comprehensive plans that require a top-down and strategic outlook. From this perspective, the difficulties in democratizing the large-scale planning process are discussed. The second approach is presented as focused on civic participation, which is by nature down-to-earth and local. By analogy, the difficulties in up-scaling civic attempts are discussed. The baseline juxtaposition discussed in this paper is therefore crosswise (see

Figure 2) due to which the dilemma of “large-scale but citizen-driven” planning is examined from both sides: firstly, from the perspective of large scale, and secondly, from the perspective of citizens.

To identify the broad set of scale-related limitations within the two approaches to planning, and furthermore to indicate fundamental challenges of large-scale but citizen-driven urban planning, the compromise is further conceptualized across three integral aspects of planning: the socio-economic, organizational, and technical. These three aspects basically reflect typologies established by Oren Yiftachel [

38]: sociopolitical, decision, and land-use; directions described by Susan Fainstein [

39]: Just Planning, Collaborative Planning, and New Urbanism, and planning traditions identified by Patsy Healey [

26]: economic planning, policy analysis, and physical development planning. Building upon Yiftachel, Fainstein, and Healey, the three aspects are understood as follows. The socio-economic aspect relates to the NEEDS and ways of recognizing and addressing them. In this regard, the fundamental goals of planning are fairness and impartiality. The organizational aspect refers to DECISION-making processes, and the main goals are openness and legality. Finally, the technical aspect of planning relates to providing concrete SOLUTIONS, and the major goals in this regard are comprehensiveness and effectiveness. All the aspects are eventually summarized and synthetized crosswise.

Although the dilemma discussed in this paper appears paradoxical in nature, and the very juxtaposition of the two characteristics—large-scale and citizen-driven—seems internally contradictory and thus unachievable, the conceptualization of the compromise across two dimensions of planning and a review of both its sides as embedded within two separate approaches to urban planning, together with a discussion of the causes and consequences of the compromise broken down across three integral aspects of planning, results in defining three major challenges of large-scale urban planning that citizens must contend with if the scale compromise is to be overcome. Accordingly, this paper argues why all three challenges must be met concurrently, as failing at one squanders the efforts made for the others.

3. Big but Authority-Led

Big plans, as extraordinary planning endeavors of a profoundly political nature [

40], require a fair amount of “creative force” to be executed [

41], p. 13. The concept of large-scale urban planning was in fact entirely alien to Greek democracies, came about with the concentration of power and wealth in the hands of Hellenistic oligarchies, and reached its apogee in the Baroque period, coinciding with the unprecedented centralization of political and economic influence in the hands of few [

5,

42]. The great urban schemes of Rome and Paris were carried out by none other than Pope Sixtus V and the Sun King, Louis XIV, also known as Louis the Great. Baron Haussmann, the father of grand nineteenth-century Paris, remains a timeless symbol of this authoritarian, large-scale tradition of urban planning [

37].

In modern societies, totalitarian politicians and modernist visionaries replaced the monarchs. Most of the large-scale urban concepts of the 20th century were developed under the aegis of modern authoritarian states and enjoyed the significant personal attention of their leaders: Hitler, Mussolini, and Stalin. In the postwar years, again, the capital cities of newborn democracies became training grounds for large-scale urban experiments: Brasília, designed by Oscar Niemeyer, or the city of Chandigarh, designed by Le Corbusier, according to whom urban plans, prepared solely by experts, “must be implemented without opposition” [

6], p. 210.

It was not much different in states with a long tradition of democracy and self-governance, where large-scale plans were implemented by modern technocrats supported by strong bureaucracies, one of the best examples of which were federal programs for infrastructure development and urban renewal in the United States. In the city of New York, for almost half a century there was one person responsible for dozens of large-scale urban developments (parks, housing projects, bridges, highways): Robert Moses, who, thanks to the unprecedented concentration of power in his hands, earned the nickname Big Bob the Builder, and was even called a Tsar [

43], p. 73. His influence exceeded the powers of the highest city and state officials [

44], allowing him to remain indifferent to resident complaints [

7] and to look down at the city from far above [

45].

Today’s liberal-economy option for undertaking large-scale developments is through public–private partnerships [

29,

46,

47]. This, however, once again means ceding influence to powerful developers: government corporations (as in the case of the London Docklands or Battery Park City in New York), quasi-governmental agencies (as in the case of the World Trade Center in New York), or corporate business groups (as in the case of MediaSpree in Berlin or Wilanów Town in Warsaw), whose dominance Erik Swyngedouw refers to in his famous “Janus Face” metaphor [

18]. Not to mention such telling examples as the city of Poundbury, whose official “town founder” is none other than Charles, Prince of Wales, the heir apparent to the British throne [

48]. Despite increasingly high expectations regarding the democratic standards of civic participation in the urban planning process, the change does not affect large-scale planning practices [

49].

The main difficulties in democratizing large-scale urban planning regarding its three integral aspects are discussed below. First among them is the socio-economic aspect. According to Eugénie Birch, the essence of urban planning is to mediate among varied local and broader interests [

50]. These demands, on the one hand, are not only numerous, but often contradictory, and some of them are even irreducible [

51]. On the other hand, according to Enrico Gualini and Willen Salet, frequently it is not a conflict of interests that is a key problem, but the absence or indifference of interests [

49]. These are situations when large-scale mediating is either impossible or pointless and must be replaced with authoritative public institutions run by bureaucratic management [

52,

53].

Susan Fainstein, who prioritizes urban equity over citizen participation—the out-come over the process—argues that focusing too much on the latter distances us from achieving real progression in fulfilling people’s basic needs, such as providing affordable housing and public transit, avoiding relocations, supporting small businesses, or fostering inclusion, to mention just a few [

54], p. 175. Although Fainstein appreciates the importance of “a threat from below” as necessary in pushing governments to be more responsive to popular needs, she does not expect public representatives and urban bureaucracies to succumb to the wishes nor to disclaim responsibility of defining what is common good, but to be independent in forging progressive change and redistributing public goods equitably [

54].

Secondly, as for the organizational aspect and tasks of communication and decision-making, Patsy Healey argues that large-scale planning, which is all about setting up directions and strategies, requires the ability to not just make practical decisions, but to reframe the very conditions of the deliberation. According to the four conditions indicated by Healey, the bigger the scale of planning, (1) the bigger the number of stakeholders to include, (2) the more diverse the logics and languages to be open to, (3) the more storylines to be agreed upon, and (4) the more possible appeals to consider [

26], pp. 269–181. Such conditions make it seem “too radical and too idealistic” to be implemented even at a smaller scale, save for large-scale developments, when the number of stakeholders grows exponentially with the scale of planning [

26], p. 283. Those practice-oriented researchers who question the possibility of meeting Healey’s conditions rely on proven solutions such as established legal procedures and bureaucratic management [

53], or even yearn back to “leaders who govern with a firm hand” [

55], p. 95.

Thirdly, as for the technical aspect involving the challenge of both delivering and executing comprehensive urban planning solutions, a large scale entails an enormous complexity of internal and external issues, as well as the need for persistent, decades-long execution. As Lewis Mumford writes, “Such a plan demands an architectural despot, working for an absolute ruler, who will live long enough to complete their own conceptions” [

5], p. 393. According to Gualini and Salet, the issues of the effectiveness and democracy of complex urban projects exceed the locally bounded and institutionally codified contexts and instruments of civic deliberation [

49]. Therefore, some still argue for disposing of collaborative action entirely and for leaving all XXL-size assignments to big developers and single architects [

56]. Others, who advocate for the need to shape comprehensive regional environments, as Kevin Lynch does, rely on the presence of authority-led, city-wide executive organs [

57]. However, the lack of expertise is not the only obstacle for other stakeholders to come up with and execute grand plans. Most often, public planning agencies are the only ones who even take a comprehensive view of the evolving spatial structure into consideration [

4,

30].

4. Citizen-Driven but Small

Any plans that are imposed from the top down are inevitably perceived by those upon whose heads they fall as attempts to deprive them of their own space and make them feel like strangers in their own homes. In this sense, the enforcement of spatial order and clarity being an attribute of top-down authorities has always met with public resistance [

58,

59]. Although mainstream planning practices have continued to fall short of citizen expectations, some are already talking about a new participatory planning paradigm [

60,

61]. In fact, carried by a wave of emancipatory movements and propelled by the spirit of emerging modern civil societies, the bottom-up opposition has shaken the very foundations of the traditional approach to urban planning described and discussed in the previous chapter.

In contrast to the “large-scale” approach to planning symbolized by Baron Haussmann, one of the symbols of the “citizen-driven” approach is Guy Debord [

37], the founder of the avant-garde revolutionary collective called the Situationists, who demanded the extension of the sphere of individual freedom, arguing that large-scale urban schemes and developments provided no positive experience to the free individual in the public space—they were considered expressions and reminders of class-based oppression and top-down control. In this spirit, Henri Lefebvre put forward the concept of the “right to the city” by which he expressed an objection towards any urban regime, government or corporate, that took away the citizens’ right to decide the future of their cities [

62]. The right to the city meant the right of all citizens to access, use, and transform urban space. However, since the right was to be founded on the simple fact of being present in the space, it remained local and unequivocally led to the rejection of any large-scale planning ambitions [

63].

In the United States, the turn against authority-led modes of urban planning was sparked by Jane Jacobs’ advocacy against government-led urban renewal programs. By resisting demolitions, resettlements, and large-scale modernist developments, Jacobs declared war on the whole urban planning tradition. She accused planners of being backward, orthodox, and possessed by lust for greatness [

64]. Jacobs praised only small, local solutions that could be undertaken without interference from any top-down authorities, which is how she “crucified” the very idea of large-scale urban planning [

65], p. 50. She argued that the life of cities had always been tentative and needed to be improvised, while large-scale plans only rigidified the future and prevented alternatives [

66].

A criticism of these endeavors arose concurrently in professional circles [

6,

9]. Among planning theorists, Charles Lindblom was one of the first who argued that comprehensive urban analysis and rational planning were basically not feasible beyond the small scale, and that the only reasonable way was to “muddle through” by opening new bargaining arenas in which multiple stakeholders could negotiate particular, small-scale “mutual adjustments” [

67]. A simple way to reduce the complexities and “uncertainties” of planning, it was claimed, was to reduce the planning scale [

31,

68]. Twenty-first-century urban discourse has been dominated by urban ideas such as Everyday [

69], Situational [

70], Tactical or Guerrilla [

28], Agile [

71], Pop-up [

72], and DIY [

73] urbanisms, not to mention the most telling one: Urban Acupuncture [

74]. All of these concepts focus their attention on individual places and short timelines—they are all small plans, but just a whole lot of them [

75].

In its extreme form, the desire to restrict the role of planners and to reduce the scale of planning led to suggestions that planning as a profession be abolished entirely [

76,

77,

78]. Others argued that the simplest way to exert influence over cities is to shape urban environments directly, in an everyday, hands-on manner [

79,

80]. In this sense, even tiny deeds such as the act of planting flowers in public spaces are considered actions of great importance to the urban landscape [

73]. Urban guerrillas [

28] and urban hackers [

81] have pursued this approach deliberately, often acting outside the law, applying methods from the fields of street art (e.g., graffiti), gardening (e.g., seed bombs), and performance, thereby undermining traditional urban planning and development rules and procedures. This has already become a global phenomenon [

82,

83].

Although the “citizen-driven” urban practice from the very beginning has been defined by locality, some of its proponents have kept faith in up-scaling the bottom-up efforts. Even Jane Jacobs was not entirely against large-scale planning [

84], nor did Henri Lefebvre want citizens to act only locally [

85]. According to Barry Bergdoll, the civic criticism has been directed primarily against the authoritarianism of grandiose planning, not necessarily against taking on big challenges or seeking territorial integrity on a bigger scale [

86]. Only the attempts to scale up bottom-up endeavors run into serious difficulties, and sometimes all citizens can do is enforce their right to the city by raising local opposition through radical actions such as demonstrations, sit-ins, and even acts of civil disobedience, which are all the “strategies of last resort” [

19], (p. 118) and “antibodies” that prevent top-down plans from being executed [

87], p. xii. The difficulties in up-scaling citizen-driven efforts are discussed below, similarly to the analysis presented in the previous chapter, regarding three integral aspects of planning: the socio-economic, organizational, and technical.

Firstly, looking at the socio-economic aspect of the titular dilemma through the bottom-up perspective means accepting the irreducible differentiation in the perception of fundamental values among groups and individuals [

51,

88,

89]. Moreover, the larger the scale, the weaker the sense of personal attachment to a space, and the less compelled people feel to take care of it [

90]. In addition, the strong social ties that define communities are only present in local, small-scale habitats [

15,

91]. Therefore, even those who have faith in large-scale collaboration admit that citizens are less concerned with large-scale plans than they are with particular projects, and that they are much more committed to securing their private, rather than public, interests, not to mention that they seldom speak as a united group with a clearly defined standpoint [

46,

65].

Secondly, regarding the organizational aspect, planning professionals argue that a participatory form of governance simply discourages large-scale visions [

10], p. 504. Modern societies value individualism and hold back from imposing one’s ideas on others, which evokes the least desirable associations with selfishness, vanity, or fraud [

11,

92]. Some place their hope in communication technologies, especially the Internet, which is believed to be capable of enabling such organic up-scaling of efforts [

93]. The goal would be to construct a high-tech urban environment in which all users were truly equal and freely organized. So far, however, technology has played a secondary role, and can neither substitute existing planning procedures nor enable citizens to exercise their right to the city directly [

94]. Moreover, the development of technology itself leads to spatial fragmentation rather than integrity [

95]. Finally, the few civic initiatives that started out as grassroots efforts, if they wanted to up-scale their impacts, were forced to develop their own structures to manage growing resources and to partner with other, hierarchically organized partners; as a result, these movements themselves adopted the features of top-down organizations [

96].

Thirdly, as for the technical aspect pertaining to the task of providing concrete planning solutions, according to Gary Hack, scaling-up citizen-driven projects might have succeeded in transcending local boundaries, but only when focused on a narrow set of purposes [

30]. The comprehensive view must be then delegated to some top-down authority, which is the reason why acupuncture/tactical small-scale initiatives turn out to be effective as catalysts only when run by government agencies [

74,

97]. Otherwise, they most often remain what they were from the very beginning: small and fragile. According to Todd Bressi, no community-oriented design methods tackle real urban issues, only isolated, dispersed projects [

98]. Furthermore, Michael Speaks proves that bottom-up initiatives hardly ever provide complex proposals, because they just “fetishize and tinker with the everyday things” [

99], pp. 36–39. As a result, various citizen-driven attempts ideal for dealing with local, subordinate issues, are not only unable to change anything structural [

70], but sometimes—due to the lack of top-level coordination—make structural issues even worse [

100].

5. Three Challenges

The review of both sides of the dilemma, together with a discussion of the causes and consequences of the compromise, proves it to be a harmful limitation to both the planning discipline and the citizens, hence the need to seek innovative ways to overcome it and enable citizens to address the challenges of large-scale urban planning by themselves. Below, built upon the above analysis as a combination of arguments presented from both perspectives, the scale compromise is eventually conceptualized across three fundamental aspects of planning: socio-economic, organizational, and technical. For each aspect a different difficulty is identified, resulting in a different fundamental challenge and being endangered with a different risk (

Table 1). Such conceptualization shall serve as a starting point for further research and innovations in planning practice regarding each aspect individually, as well as all of them together, since this paper argues that all three challenges must be met concurrently, as failing at one squanders the efforts made for the others.

According to the socio-economic aspect of the scale compromise, the larger the scale of planning, the more diverse the parties, and therefore the more complex the demands and the social conflicts. The parties form their views and demands upon different values and in reference to subjectively identified territories of different scales and boundaries. While some of the demands are internally contradictory, others remain ill-expressed or even absent. Hence, leaving the task of forming public interest to the citizens themselves runs the risk of either never reaching a consensus, or letting the most powerful actors dominate the weaker ones, leading to an illusory consensus and dramatically unfair benefiting—the fundamental rationale behind Sherry Arnstein’s “Ladder of Citizen Participation” [

32]. If the citizens do not demonstrate exceptional credibility in this regard by formulating a joint and consensual vision in a way which takes into account as many demands and needs as possible, their bottom-up attempts might need to be limited by public representatives, authorities, and experts for the sake of equity itself, which is basically an argument made by Susan Fainstein in her seminal book

The Just City [

54].

In the second, organizational aspect, the larger the scale of planning is, the more numerous the stakeholders are, and therefore the more difficult it is to set up a single deliberative arena that could not only be accepted, but also constructed by all the actors collaboratively, and that would eventually be inclusive to all individual logics, styles of argumentation, and propositions, as only such openness might let the process be directly deliberative. Hence, management structures—even when initiated from the bottom—are at risk of acquiring features of hierarchical organizations, as they must make legally binding decisions, manage significant resources, and partner with other hierarchically organized partners. However, if the citizens do not maintain a decision-making process that remains horizontal, transparent, inclusive, and welcoming to future participants, they will not be recognized by public authorities, experts, and other potential allies as truly representative and reliable partners. According to Erik Swyngedow’s “Janus face of governance” metaphor [

18], collaboration with misrepresented civic groups and biased leaders should be considered even more harmful to democratic standards than simply relying on elected officials and bureaucratic mechanisms.

Finally, regarding the technical aspect, the larger the scale of planning, the stronger the need for planning expertise, coordinating competencies, and long-term consistency in the project execution. A large-scale urban plan must comprehensively account not only for the needs of various groups, but for the conditions of different urban territories and for the strategic requirements of the city as a whole, even if some of them remain beyond the scope of individual or group interests. Therefore, the citizens need to obtain such professional support and resources and remain consistent with legal requirements and formal procedures, otherwise the planning process will be taken over by city-government-dependent planning agencies for which the citizens would be nothing more than respondents or petitioners. Furthermore, according to

The Nightmare of Participation by Markus Miessen, most often the risk is not just that citizens will get bogged down in meaningless details, as it is a sad reality that they do, but that as a result they will remain wishful and self-marginalized within the strategic and large-scale urban planning process [

24].

Every dimension of the “scale compromise” is a challenge in itself. However, all three difficulties and risks occur in parallel rather than in series, therefore all the three challenges must be met concurrently. As argued above, failing at a single one would squander the efforts made for the others. Firstly, even if the citizens are truly involved in the decision-making process (organizational aspect) and take planning issues into account comprehensively (technical aspect), but their needs are expressed in a biased way (socio-economic challenge unmet), the plan remains detached from the people and loses their support. Secondly, when the needs are well addressed (socio-economic aspect) and the authorities share their planning expertise (technical aspect), but the people’s voice is expressed by a few pretenders rather than true leaders (organizational challenge unmet), the plan lacks a democratic mandate and can be easily contested. Thirdly, even if the needs are well addressed (social aspect) and the citizens deliberate flawlessly (organizational aspect), but their planning decisions are fragmented and subordinate to already existing, top-level strategies (technical challenge unmet), the plan can no longer be considered citizen-led. Thus, if the scale compromise is to be overcome, finding a successful recipe to all the three challenges is a must.

6. In Search for Inspiration: Urban Greenways

The goal of this paper was to raise the issue of the scale compromise, to put it in perspective, and to conceptualize the term in a possibly all-encompassing way to make it a well-grounded starting point for further research. Thus, although the paper includes real-life references in the beginning sections in which two approaches to urban planning are described, the discussion sections remain abstract to make it possible of drawing universal conclusions. However, since the concept is ready, it can be employed in examining cases of large-scale urban plans that are attempted—more or less successfully so far—by citizens. An exemplary application of “scale compromise” conceptual framework is presented below.

In search of examples that address a significant diversity of needs equitably and avoid illusory consensus (socio-economic aspect), maintain involvement of a great multitude of stakeholders without losing trust among citizens and of authorities (organizational aspect), and provide ready-to-implement, comprehensive planning solutions (technical aspect), urban greenways together with the whole civic culture developed in the U.S.—the Greenway Movement—seem to be a particularly promising point of reference [

101,

102,

103,

104]. Urban greenways not only illustrate the challenges of the scale compromise, but also provide practice-based clues on the ways in which the compromise might be overcome. Greenways contain features of both large-scale developments (because of their significant length) and local embeddedness (because of their relatively insignificant width). The former provides for supralocal and cross-boundary comprehensiveness, while the latter empowers citizens to participate through their customary practices and existing organizational structures [

105]. As such, greenway projects seem to provide common ground for two separate approaches to planning: large-scale urban planning and bottom-up civic involvement.

Regarding the first—social—dimension of the scale compromise, greenways are seen as being particularly well suited for providing the backbones for joint and consensual large-scale urban visions that consider many demands and needs. First, they refer to fundamental and commonly shared values associated with greenery: environment, health, freedom, prosperity, and wealth [

106]. As such, greenways are devices for preserving natural habitats, plants, and wildlife corridors, for providing egalitarian open spaces, as well as for bringing order to chaotic urban structures, and for improving neighborhoods, which in turn also attracts new investments and creates more jobs [

107]. Moreover, researchers highlight the fact that greenways themselves link adjacent neighborhoods and communities, and thus strengthen ties of social capital between them [

102]. Greenways are therefore seen as vehicles for building extraordinary linear communities [

103].

With regard to the second—political—dimension, the task of institutionalizing greenway visions, i.e., “generating familiarity, awareness, legitimacy, and funding opportunities” [

108], (p. 45) has been so far undertaken successfully by various stakeholders, civic groups included. Despite their large scale, greenway developments require proportionally low financial investment and can be initiated without substantial public contribution [

103]. Due to these factors, many greenways have been locally conceived and organically developed in a snowball manner [

109]. These developments have been led by various cross-sectoral groups of diverse organizational structures in which civic groups played significant roles [

102]. This makes greenways a promising large-scale planning concept, evidenced by “its record of successful integration of top-down and bottom-up approaches, and its emphasis on physical and organizational linkages” [

110], p. 54.

Finally, regarding the third—technical—dimension, today’s urban greenways are not mere green recreational paths, but often backbones of complex mix-use urban corridors providing for various functions and land-uses implemented through sustainable development strategies [

111,

112]. At the same time, although greenways can induce widespread and deep urban transformations, their longitudinal characteristics allow them to “be woven into the urban fabric” relatively easily [

109], p. 79. As large-scale urban schemes, greenways fulfill their primary role of preventing fragmentation and coordination of various developments while imposing no totalitarian or utopian single-minded visions. Today, greenways are more often seen as almost textbook urban planning and urban design components [

101,

113].

Indeed, some recent greenway developments in the city of New York examined through the lens of the Stewardship Theory prove to be both large-scale and citizen-driven to a great extent [

104,

114]. In some cases, citizen-driven practices intertwine with public authority-led policies and result in hybrid governance structures [

104]. The examples are promising, as they seem to meet all three dimensions of the scale compromise. According to Erika Svendsen, these greenway projects were run by supralocal and cross-boundary coalitions which, first of all, were based on large-scale environmental assets and goals (the social dimension); second, achieved a citizen-power level of participation in which they shared the reins of governance (the political dimension); and third, were truly involved in the stages of planning, designing, building, and governing new developments (the technical dimension) [

104]. Furthermore, and even more contrary to the scale compromise, “it was the citizen-led task force rather than the government-led task force that took up the cause of long-term planning” [

104], p. 81.

To conclude, although the projects need to be further investigated and examined directly through the lens of the scale compromise conceptual framework, recent urban greenway developments provide fruitful insight into the dynamics of multi-scalar urban planning endeavors. Hopefully, a valuable lesson might be learned here, and the findings applied to a broad scope of urban projects—including housing, business, and infrastructure. Indeed, this paper points at one of the key challenges, if not the primary one, of contemporary planning theory and practice, which, for the last half century, have aimed at keeping planning truly comprehensive while striving to make it open and participatory. So far, as shown in this paper, the prevailing “scale compromise” has remained harmful and destructive to both urban planning and public life. Greenways offer a glimmer of hope, but if citizens are to face grand urban crisis and take the challenges of large-scale urban planning by themselves, all three dimensions of the scale compromise must be systematically overcome.