Abstract

This study aims to examine the impact of political instability, food prices, and the crime rate on tourism development in Pakistan over the semi-annual data from 1995 to 2019. To achieve the goal of this study, an asymmetric ARDL technique was used. The Asymmetric Autoregressive Distributed Lag Model (ARDL) aided in gaining access to both positive and negative shocks in political stability, crime rate, and food inflation. The findings showed that due to positive variations in the political conditions, tourism will increase by 0.12%, and if political instability prevails in the country, tourism will decrease by 23%. On the other hand, the magnitude of political stability is less than the negative variation of political instability on tourism. The study concludes that there is a considerable asymmetric association between political instability, crime rate, food prices, and tourism development in Pakistan. Based on these findings, it is advised that the government adopt proactive measures to establish and reinforce the political stability mechanism and terrorism control, as well as to improve the living standards of the general population. Moreover, establish a structure for adaptation efforts, focusing on the coordination of tourism expansion platforms for sustainable tourism in Pakistan to attract more foreigners for the sake of a surge in tourism proceeds.

1. Introduction

Tourism is crucial for the prosperity of many economies worldwide. It has numerous rewards for host nations. It amplifies the economy’s revenue, generates employment, builds a country’s infrastructure, and promotes a sense of cultural relations among tourists and natives [1]. It is considered the most significant contributor to economic growth, along with exports and physical and human capital [2]. Tourism is one of the world’s biggest sectors, contributing to 7% of global trade; the number of tourists has climbed from 25 million to 1.4 billion worldwide and the revenue of hosting countries has surged from USD 2 million to USD 1.7 trillion [3]. However, this industry has shown vulnerability to political instability and upheavals and many destinations have vanished from the worldwide tourism landscape as a result of political instability [4]. Ranasinghe and Deyshappriya [5] contended that political stability is a precondition for enticing foreign tourists and a basic prerequisite for the growth, survival, and successful establishment of the country.

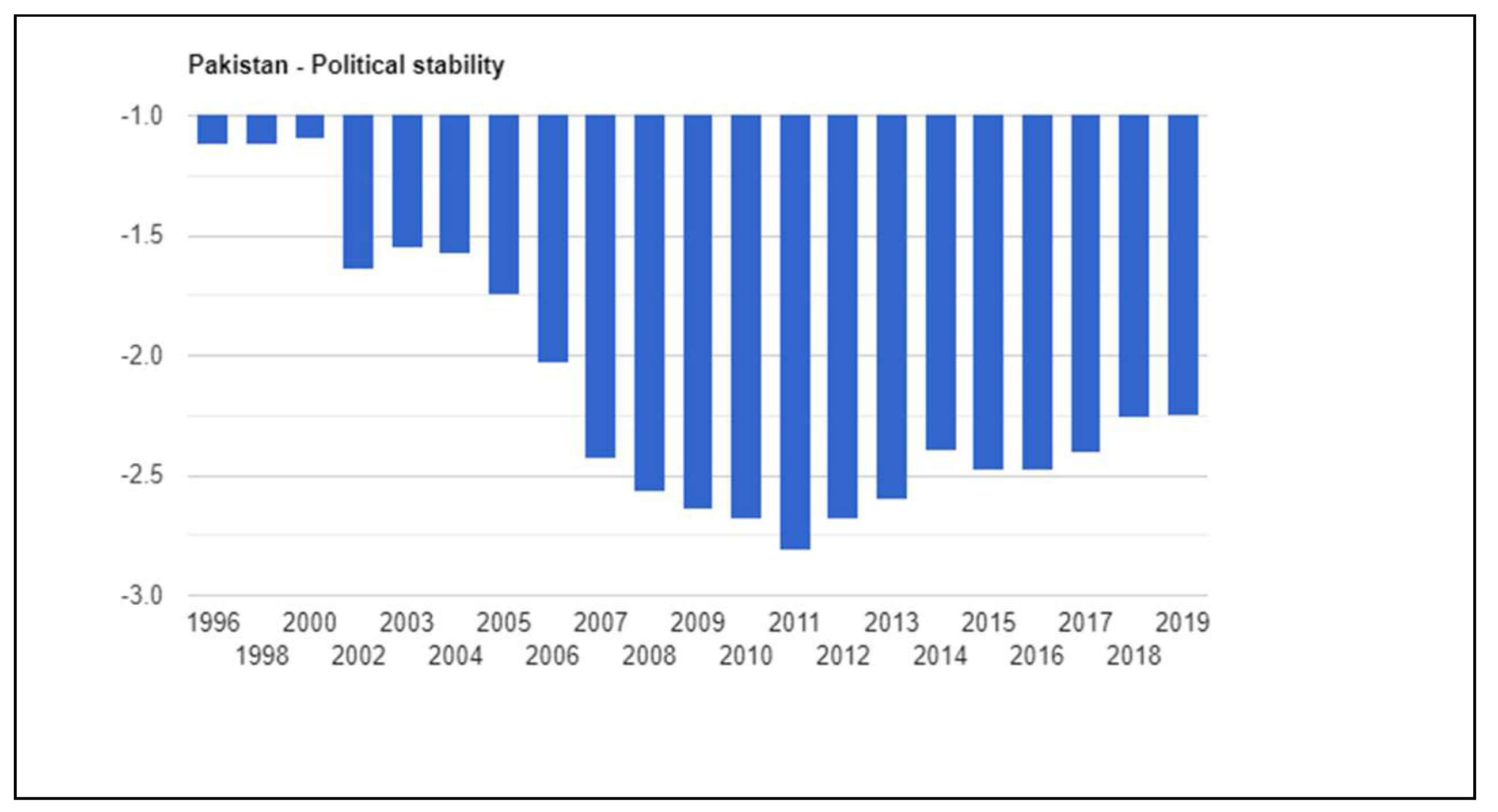

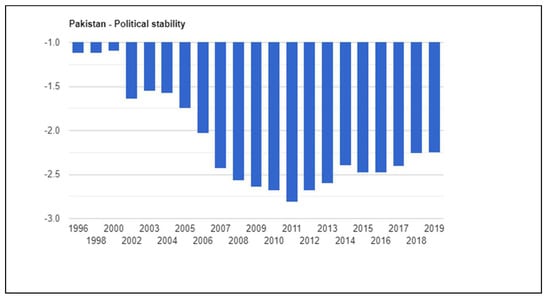

Political instability has been a persistent issue in Pakistan since its establishment. Pakistan is surrounded by political instability and has faced many waves of it for the last couple of decades. This situation was further aggravated in 2014 when Pakistan Tehreek-e-Insaf (PTI) announced a 100-days sit-in (Dharna) [6]. The historical view of political instability is represented in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Pakistan political stability source: theglobaleconomy.com accessed date on 10 October 2022.

The political stability index ranges from −2.5 (weak) to 2.5 (strong). According to the figure above, Pakistan’s average value was −2.12 points, with a low of −2.81 points in 2011, and a high of −1.01 points in 2000. The most recent value for 2019 is −2.25 points. Moreover, in 2019, the world’s average value of 195 nations was −0.05 points. To reduce political instability, the role of tourism is unavoidable. According to [7], tourism not only reduces political instability in the government but also boosts various industries such as transportation, manufacturing and commerce, and agriculture and ultimately increases foreign exchange reserves.

On one hand, Pakistan’s tourism industry has been facing problems for a couple of decades, such as government instability as democratic governments hardly complete their tenure, insecurity at tourist sites, expensive tours due to a high rate of inflation, a lack of government incentives for the development of the tourism industry, and, last but not least, the exchange rate policy. Alternatively, Pakistan also has great natural resources and enriched destinations that can catch the eye of local and international visitors [8]. Gilgit-Baltistan (GB) is a very heavenly and beautiful tourist destination in Pakistan, where the nexus between terrorism, political stability, and tourism continues in the region due to several factors. Although the GB region has important destinations based on its strategic location with three mountain ranges (the Hindukush and Himalaya), political instability and tourism development continue in the region due to several factors. However, the GB region has important destinations based (strategic) on the location having three mountain ranges (Hindukush, Himaliya, and the Karakorum) along borders with China [9]. Here, political instabilities (caused by past events and insurgencies) by which day-to-day levied emergencies, long-time curfews, the shuttering down of shops and markets, increase in crime, losses in businesses, deterioration, and mismanagement of resources of GB rings the alarming stage for tourism [10].

Numerous tourist sites in Pakistan offer a huge diversity including Kaghan, Naran, Gilgit, Chitral, Ayubia, Shangla, Murree, Balakot, Malam Jaba, archaeological and historical sites, and mountain ranges. These areas of the country rely substantially on tourism revenue [11]. Furthermore, Gilgit-Baltistan (GB) is a paradise-like region in Pakistan.

Previous studies examined the economic impact of political instability [12,13,14,15,16,17]. Apart from these empirical studies, [18] extended the body of knowledge in the context of tourism and international conflicts and war and discussed the multifaceted relationship between tourism and war. Similarly, [19] examined the multifaceted affiliation between tourism and peace.

Other researchers focused on tourism and economic growth such as the studies of [20,21,22,23]. However, most of these studies focused on linear models to compute the impact or connection among the variables. The study of [24] suggested that linear models are only appropriate in measuring linear associations, whereas, generally, variables have non-linear trends. Similarly, [25] contended that non-linear models have additional explanatory power than linear models. A nonlinear autoregressive distributed lag (NARDL) technique was used by [26] for tourism and pointed out that these models are less informative, specifically, from the viewpoint of policymaking due to the shortcoming of using linear models. Considering these shortcomings, the researcher is motivated to fill this gap and add knowledge to the existing body of literature. To address this problem, the researcher aims to use the asymmetric Autoregressive Distributed Lag (ARDL) technique to measure the association between tourism, political instability, crime rates, and food prices. The findings of the study will be relevant and more informative for policymakers.

The remaining part of the study is planned as follows: literature review, methodology, data analysis, and conclusion and practical implications.

2. Literature Review

As no single established theory of tourism and political instability exists, this study is based on the ideas and concepts discussed in the existing literature.

2.1. Relationship between Tourism and Political Instability

Political instability is associated with the possibility of protests, strikes, and different acts of violence, crimes, regime reversals, insurgencies, and government failure. Consequently, political stability is coupled with the notion of a “failed state” [27]. According to [5], political stability is a precondition for luring foreign tourists and a basic prerequisite for growth, survival, and successful establishment.

Tourism and political instability were first discussed in the seminal work of [28] and continue to catch the attention of researchers. Moreover [29], used the concept of political instability by selecting various variables such as terrorist attacks, rapid changes in local and foreign policy, and economic, social, and political well-being. Similarly, the security situation is not only disturbing tourism planning by individuals but also affects the political image of a country similar to Iraq. Furthermore, the socioeconomic and political benefits are eroding. Substantially, the perception of tourism among the general public has been damaged as a result of these security concerns.

Webster and Ivanov [30] conducted research on the causes and a factor behind political instability. They found that tourism is a driving force that helps to create a soft image of a nation; it implies a nation is a positive peacebuilder, which leads to political stability in a country. The selected countries were Thailand, Cyprus, and Korea to investigate that tourism is a key factor to improve political stability. The finding of the study reveals that there is a positive association between tourism and political stability. The authors of [31] investigated the political riots and insurgencies in the context of Egypt, Thailand, and Lebanon where lots of instabilities prevailed. The finding of the study shows that the political disturbance and turbulences in the country shake the tourism industry badly not only for domestic tourists but also for international tourists reluctant to go to that country. To improve tourism in the countries, we must create policies that build sustainable peace and reduce political instabilities.

Richter [32] argued that political stability requires more technical processes to improve it, which includes investments in basic infrastructure, such as security, and also other facilities. This study was conducted in three countries, namely Sri Lanka, Pakistan, and the Philippines. The findings of the study reveal that for tourism there must be political stability in the country. Moreover [33], has also contributed about political instabilities and insurgencies that have been prevailing in the North Cyprus region due to the tourism industry. For this purpose, they found many alternatives by adapting to integrate with Turkey economically and collaborating in federation with the Greeks. This is qualitative research based on interviews (semi-structured) with senior-level managers and experts. As per the findings, the political instability does impact tourism in the long term in Cyprus.

Moreover [34], determined the role of political unrest on the leisure industry in specific countries of the Mediterranean region. They conducted a study from the period starting from 2002 to 2015. A panel-based error correction and panel base causality test have been used. They found that political instability has a positive association with the tourism sector in the long run. Furthermore, it has been found that there is a two-way causality association between tourism and political instability. Similarly, [7] have analyzed the importance of tourism in Sri Lanka at a given time interval from 1970 to 2008. Time series research was conducted to define the association between political instability in Sri Lanka and its tourism development and features. The results depict that the political instability and economic indicators are responsible to encourage tourism and the development of tourism.

Causevic and Lynch [35] managed a research in the context of Bosnia and Herzegovina in which they found that political disturbances can cause a significant decrease in tourism and tourism development in a specific region. The results revealed that to encourage the tourism factor it needs to settle down the political instability in various headings. The authors of [36] contributed to the tourism level and political instability in two developing countries such as Fiji and Kenya. The finding of the study reveals that the internal political instability does impact the tourism industry in these regions more strongly than outer problems such as terrorist attacks, etc.

2.2. Relationship between Tourism and Exchange Rate

Khandaker and Islam [37] focused on macroeconomic factors that create an impact on tourism levels such as exchange rates and political stability. Moreover, in those countries where tourism is the main earning industry for them, the political stability and volatility in the exchange rate are negatively correlated with tourism, favorable government policies, and macroeconomic policies that are friendly to international trade and are good reasons for improvements in tourism in these countries. The authors of [38] employ the regression (Poisson) model to identify and analyze the determinants of tourism from worldwide to African countries. For this, they used data over twenty years. As a result, they found that political stability is one of the major determinants of tourism in African countries.

Hai and Chik [39] observed the tourism industry and tourism demand in Bangladesh. Despite other factors, such as ignorance of poverty levels, political issues, or riots, the reliance on capital comes from foreign countries and others. From the study, it may be suggested that political instability has a strong relationship with the improvements in tourism in Bangladesh.

Farmaki et al. [40] asserted that Cyprus’s political climate is shifting quickly. The government is lagging in the macroeconomic targets in terms of worldwide visitor attraction. This study identified the factors that determine the long-term viability and development of the tourism business. Based on Luke’s concepts, qualitative research has been performed by conducting semi-structured interviews with respective persons. The results indicate the tourism industry faces challenges of political instability that stem from the administrative powers, problematic political structure, changing socio-political environment, and instabilities that may discourage current tourism activities and their developments. The authors of [29] used the concept of political instability to refer to the security for terrorist attacks, rapid changes in local and foreign policy, and economic social and political well-being. This security consideration is not only disturbing the tourism planning by individuals but also affects the political image of countries such as Iraq. Here, in this case study of Iraq, the socio-economic and political benefits lead to declining confidence. Substantially, the tourism perceived all around people has been affected due to these security concerns.

According to [41], in today’s world, governments have recognized tourism as a major business and developing countries, in particular, are focusing their efforts on centralizing tourist planning and development. There are still a few weaknesses in recent policies that need to be addressed. Turkey could be used as an example. As a result of the findings, it is possible to conclude that political stability and decentralization are required to increase tourism. Ingram et al. [42] claimed that Thailand’s political ramifications and instabilities have an impact on people’s perceptions of tourism and destination revenues. For this, qualitative research was undertaken and based on the findings; it is possible to conclude that the tourist industry’s relevant spokespersons should engage with the government in order to create more revenue from tourism. This study recommends focusing on destination management through reducing political turmoil in the locations. The government must work on tourist perception by demonstrating Thailand’s political stability, as a result of which tourism will improve substantially in the long run.

Baig and Zehra [43] discussed the importance of CPEC and the Pak-China corridor in the GB (Gilgit-Baltistan) province. The governance level in any area creates deep impacts on its tourism. Governance includes political stability, rule of law, law and order, etc. The real stability in politics may help tourists to choose their destination securely. The data were extracted from ten districts of this province. The results reveal that the governance level (concerning political stability) directly and indirectly impacts the tourism industry in Gilgit-Baltistan.

Khan [44] stated that political instability emerges as a result of sectarian tensions in Pakistan’s Gilgit-Baltistan area. The number of tourists, both domestic and international, has suffered as a result of political unrest. As a result of the findings, it may be advised that efforts be performed to eliminate the political instabilities that have arisen under various labels, as they are a major role in the decline of the tourism business in Gilgit-Baltistan.

Khan et al. [8] described that the tourism industry has faced various problems in Pakistan. This study considered tourism as the more sensitive industry by the governance level in any country beside the fastest growing industry in the entire world. Pakistan has many problems such as political instabilities, economic stabilities, terrorism, and militancy. Based on the conclusion, it could be acknowledged that political instability is one of the major causes of reducing the tourism level.

2.3. Relationship between Tourism and Food Prices

According to [45], a research study published on global economic prospects, food price increases have major macroeconomic and microeconomic consequences. Food price increases at the macroeconomic level led to higher inflation, which might reduce actual household income. Rising food costs may also cause trade disruptions, slowing economic development in food-importing countries. Food prices in the world reached an all-time high in August 2011. In the year 2007–2008, an upsurge in food prices caused an estimated 105 million populaces to move below the poverty line.

Similarly, [46] concluded that this occurrence has also engendered widespread doubts about food safety for the poorest and worries about future global food crises. As the increasing frequency of severe changes in the weather is a menace to food production and a hindrance in the supply of food as well as access to food, the upsurge in food price in 2010–11 could happen again. Nominal world food prices reached an all-time high in August 2011. This came shortly after the food price increase in 2007–2008, which drove an approximated 0.105 billion individuals into severe poverty.

According to [47], if the frequency of severe weather events enhances the risk of disturbances to food production and hindrances in food supply, food availability, and food price spikes similar to those seen in 2010–11 may occur again. Global hunger and extreme food insecurity surged from 2014 to 2017, reversing a decade-long reduction. The number of malnourished individuals reached 0.821 billion in 2017, an increase of 5% from 2014, and a failure to attain the Sustainable Development Goal (SDGs) of ending starvation by 2030. Furthermore, food (cooking) tourism is a source of concern for station managers, academics, and marketers, as food expenditure is one of the most important aspects for the tourism sector [48,49]. Additionally, in the past, because food has been a vital magnetism for visitors, several locations have struggled to deliver distinctive culinary encounters to tourists [50]. Likewise, local food can strengthen a vacation spot because it is a logo of nationwide, local, and individual personal values [51,52].

The concept of the theory of consumption values (TCV) presented by [53] reflected on why purchasers select to shop or no longer to shop for a particular item for consumption and why consumers pick one product category over another [54]. The consumption values are the landscapes of a service or product as perceived by customers. The TCV’s theoretical foundation has been extensively discoursed in customer behavior and marketing related literature sources [53,55,56]. According to [55], the remaining three key assumptions are: (1) patron preference is a multi-consumption values function, (2) consumption values are impartial, and (3) consumption values can produce extraordinary contributions in unique settings. Furthermore, clients make informed judgments based on more than one price dimension, such as high quality, enjoyment, the value of money, society, and their trade-offs. The TCV is a significant variable in advertising that has been extensively emphasized by practitioners and researchers [57,58]. Moreover, the TCV can unearth various product classes in addition to shopper foodstuffs, manufacturing products, and leisure industry services [59]. This theoretical structure has demonstrated excellent predictive validity in over 200 cases [53,56,60]. Consistent with [53], the TCV proposes that clients’ selections are inclined by several intake philosophies (counting emotive, functional, epistemic, and societal) and that, individually, intake might have a unique impact on different situations.

2.4. Relationship between Tourism and Crime Rate

According to [61,62], large-scale criminality disrupts the tourism destination as well as the state of the country in which it is located. The most important and apparent consequence of delinquency on sightseer destinations is the unfavorable image of a particular nation, which seriously influences the number of visitors and, as a result, revenue. Furthermore, the media has a substantial influence on the emergence and development of an intending sightseeing location because a sightseer’s first impressions of a place are likely to emanate from the media in an increasingly media-saturated society, as noted by [63]. The authors of [64] discussed the influence of crime on tourism, reporting on the impact on the behaviors and attitudes of individuals, i.e., visitors, along with their surety to stopover or reconsider a stopover where unlawful actions occurred. Furthermore, [62] found that the fear of crime has a significant impact on people and their actions and it can induce people to stay at home in the sense of tourism, reduce activities, and even prohibit travel entirely. Similarly, [65] concluded that crime has a negative influence on tourism. They also stated that security cannot be taken for granted in tourism and that significant efforts must be made collaboratively, both financially and administratively, to secure the environment for tourists.

The linkages between crime and tourism have been researched using a variety of theoretical frameworks. However, the majority of the research is based on traditional criminological notions that can be used for an extensive variety of crime classes and theoretical drive of the tourism-crime nexus is unusual, for example in [66]. Two theoretical approaches are employed in the literature to explain tourism-related crime and victimization: routine activity theory and hot-spot theory. Hence, these notional methods should provide us with a useful understanding of the facets that cause tourist victimization and how we may relieve them.

The theory of routine activity of [67] is grounded on fundamental human ecological concepts; routine activities in everyday life are central to the idea. The routine activity structure, according to Cohen and Felson, has an impact on criminality and crime patterns. Criminal activity is considered as a routine action that is linked to certain other routine behaviors, with an emphasis on the relationship between criminal activity structure and the organization of ordinary activities. According to this idea, three factors must come together for the crime to occur: (1) highly motivated offenders, (2) proper victimization targets, and (3) a lack of a protector who can prevent victimization. Tourists are appealing targets since they are carrying money or valuable items and are in a new location. The committers of illicit activities are stimulated, principally in impoverished nations, by spotting a vibrant discrepancy amid those who hold and those who do not; in addition, if there are no fully fitted shields, for instance police or armor, the risk to commit criminalities against tourists is multiplied [62].

Hot-spot theory [68] is another theoretical framework and is grounded on environmental criminology and assessing criminal action. It highlights that certain parts may be linked with larger crime rates. “Sites, where travelers are presumably to be victimized, where tourists are most likely to be victimized have been identified to concentrate in a limited unlike types of places” [68]; in addition, there are idyllic circumstances entailed for assaults on trippers. For instance, [68] highlights the Dade Region in the state of Florida where 29 percent of all registered property criminalities were practiced in 1993. Moreover, it where 37 percent of the entire crimes against tourists in the state of Florida occurred. It is fascinating to note that the Dade Region accommodated for 16 percent of all sightseers who visited the state of Florida this year, despite nearly 30 percent of all criminal felonies occurring there.

Additionally, the third theoretical mode of examining the nexus between tourism and crime is centered on the financial perception of crime. The underpinning of the economic philosophy of crime was shaped by Nobel laureate Gary Becker, who detailed that people would involve themselves in criminal doings if they perceived that their incomes from criminal actions could be larger than if they dedicate time, money, and other means in supplementary actions [69]. This process deliberates that criminals make rational choices and, alongside gaining skills, evaluate the possible prices (the likelihood of being detained, the strictness of punishment, communal stigma) before committing a criminal act. Furthermore, pertaining to this rule to the association between tourism and crime, the elementary claim is that tourism progression and a surge in tourists can arouse economic movement, upturn employment chances and earnings for resident persons, and also surge the openings for criminal activity [70] owing to the enlarged amount of possible victims.

3. Materials and Methods

The purpose of this study is to investigate the impact of political stability on tourism, food prices, exchange rate, and crime rate in the setting of Pakistan, using the bounds testing method of co-integration. It was stated that linear models are ideal for assessing linear variables, whereas time series variables are primarily nonlinear. The authors of [26] used the NARDL model to examine the relationship between inflation, oil prices, the exchange rate, and tourism. Tourism is vulnerable to nonlinearities, according to [71]. As a result of this reasoning, this study was conducted to evaluate tourism using a nonlinear model. The political stability, tourism, food inflation exchange rate, number of tourists, and crime rate were employed as variables for this purpose. Nonetheless, the asymmetric methodology distinguishes this work. To study the long-run relationship between political stability, food inflation, crime rate, exchange rate, number of tourists, and tourism receipts, the statistical model can be written as follows:

where Rtour, EXR, NT, PS, CR, and FI represents the receipts from tourism, exchange rate, number of tourists, political stability, crime rate, and food inflation, respectively. Furthermore, earlier studies, to the best of the authors’ knowledge, were based on a linear framework. The current study was conducted in a nonlinear framework due to nonlinearities in time series. The postulates of this technique are as follows: First, if the series components (both positive and negative) are cointegrated, the time series may include unobserved co-integration [72]. Second, there are structural breaks and asymmetries. The primary goal of this research is to investigate the asymmetric link between political stability, exchange rate, food inflation, crime rate, number of tourists, and tourism receipts. Furthermore, the nonlinear functional form of the model can be represented as:

TourR= f (PS, PS−;, FI+, FI−, CR+, CR−, EXR, NT)

Following these, the empirical research executed by [26,73,74,75] found asymmetry in tourism receipts, political stability, crime rate, and food inflation.

The model’s nonlinear statistical model can be represented as:

where PS is Political Stability, EXR is the exchange rate, NT is the number of tourists, Tour is the tourism receipts, CR is the crime rate, and FI is food inflation, whereas, γ0, γ1, γ2, γ3, γ4 show the long term co-integration vectors. However, TOUR+ and TOUR- CR and FI are the partial sum of the process of positive and negative variation, respectively.

The long-run association between two or more variables is estimated using the ARDL technique, ECM, or Granger Causality in conjunction with econometric methods based on stationary criteria. These models consider the asymmetric nature of the data series employed. The linear relationships between variables, on the other hand, are determined using linear regression models, which fail to account for the nonlinear effect of these variables. Considering the non-linear nature of the variables, [76] extended the ARDL framework with an asymmetric ARDL cointegration technique [77]. This method is useful for detecting short-term volatility and structural breaks (asymmetries).

4. Results and Discussion

In this portion, a statistical analysis was conducted using a predetermined technique. A unit root test, descriptive statistics, model criterion selection, short-term and long-term interrelationship, bound test assessment for co-integration, and the dynamic multiplier graph are among such empirical outcomes.

4.1. Descriptive Statistics

Table 1 shows descriptive statistics of the study encompassed. Moreover, the values of mean, median, standard deviation ranges of each variable, skewness, kurtosis, and Jarque-Bera test for normality of the data.

Table 1.

Descriptive Statistics.

4.2. Results of Unit Root Test

Before the co-integration scanning, it is crucial to scrutinize the stationarity of time series data, as regression can be spurious if stationarity is extant in the time series dataset. Moreover, there is a prerequisite of the ARDL bound test that no variables are integrated at the order of I (2). On the other hand, there is no constraint on the diverse order of the integration of data.

A valid conclusion will be pinched if any I (2) variable is utilized in the model [78] [79]. This research is commonly used a Augmented Dickey–Fuller test (ADF) and Phillips–Perron [80,81] unit root tests to verify the data’s stationarity [82]. The issue of the unit root is crucial, it determines the appropriate econometric model for the analysis. The results in Table 2 show that all of the variables including tourism, political stability, food prices, crime rate, number of tourists, and exchange rate are in a mixed order of integration. Based on the finding reported in Table 2, we can use the nonlinear or asymmetric autoregressive distributed lag model (NARDL) for computing the impact of tourism on political instability [76,83].

Table 2.

Results of Unit Root Test.

4.3. Non-Linear ARDL Estimations

This study aims to account for the asymmetric effect of political stability with other variables on sustainable tourism expansion in Pakistan. Furthermore, the non-linear ARDL (NARDL) method introduced by [76] was applied to accomplish this goal. Table 3 shows the result of nonlinear ARDL. Furthermore, if the two partial sums bring an identical coefficient in sign and length, the effects are symmetric; otherwise, they are asymmetric. To undertake the general-to-precise procedure to reach the final specification of the NARDL version by trimming insignificant lags [76]. Hendry [84] removed the variables that were both insignificant or theoretically undesirable. DNT (−5) was removed in the above analysis as well.

Table 3.

Short and long-term non-linear ARDL model.

In Table 3, the results show the short-run and long-run outcomes of the NARDL model. According to nonlinear ARDL, the political stability, crime rate, and food inflation consist of two divisions: positive and negative. The finding of the study is showing that there is a significant association between tourism and political instability. The present research was validated by [85], who pointed out that political instability leads to negative impacts on tourism. Political instability, crime rate, terrorist attacks, and neighboring conflicts are also associated with a decline in tourism. Similarly, a study in Gilgit-Baltistan revealed that tourism was affected due to the regional security situation and neighboring conflicts [9].

Furthermore, the results show the positive political coefficient is (−0.4543) and negative political coefficient is (−0.8254), respectively; the coefficients are provided in the table below. To find out the long-run coefficients of PS-P and PS-Neg, each coefficient was divided by the coefficient of Tour (−1). The computed value of both PS-P and PS-N is (−0.4543/−0.0363) = 0.001252 and = (−0.8254/−0.0363) = 22.738, respectively, and the other variables will be calculated likewise.

Moreover, with favorable political conditions, tourism increases by 0.12%. Conversely, it decreases by 22.8% in unfavorable conditions. On the other hand, the magnitude of negative shocks exceeds the positive shocks in political stability.

Our findings are consistent with [86], who found that, due to political instability, both the foreigner and local tourist’s traffic declined and revenues derived from foreign tourists declined too. Furthermore, on the foundation of these results, the null hypothesis of no asymmetric association can be rejected. It is established that political instability has an asymmetric significant impact on tourism.

Furthermore, the findings of the study confirmed that there is also a significant association between the crime rate and tourism. In Table 4, the positive coefficient of the crime rate is −0.3626 and the negative crime coefficient is −0.5423, respectively. Similarly, to find out the long-run coefficient, we divide both coefficients by the coefficient of tourism. The calculated value of both crime positive −0.3626/−0.0363 = 9.98 and 0.5423/−0.0363= −14.93, respectively.

Table 4.

Asymmetric Co-integration.

The results show that if the crime rate increases in the country, then tourism will decrease. Our findings are in line with the study of [87]. They concluded that crime has harmful effects on country tourism. So, on the basis of the above outcome, the null hypothesis is rejected. It is found that the crime rate has an asymmetric impact on tourism. The previous study also confirmed that political uncertainty had a substantial impact on tourism [5,88,89] and some other researchers have stated that stability is a must for a thriving tourism economy [90]. On the other hand, the tourism industry is very unstable [91,92,93] and instabilities such as crime, terrorism, and conflict frequently result in a significant decrease in tourist flows. This study’s findings are consistent with the findings of the preceding research.

Finally, it is concluded that the finding of this research is not only according to anticipation but also on the results of other empirical studies. Consistent with these studies, tourism is decreasing due to an increase in the crime rate, political instability, and sometimes due to food inflation in the country [35,85,94,95,96,97,98,99]. Finally, this asymmetric relation is plausible because, when the tourists enter any destination, their major concern is the political condition of the country, violence against tourists, and the crime rate. The crime rate and violence in the country have dual effects on human welfare and tourism in the short run and long run. The authors of [100] inspected the association over time between tourist arrivals and crime rate and concluded that the crime rate has discouraged tourist arrivals. Moreover [101,102], confirmed that political instability in a country had harmful effects on tourism. The results of all the above studies are consistent with our study. Lastly, the Durbin-Watson value is 2.158, which is greater than the value of R-squared at 0.774. As a result, it indicates that there is no question of spurious regression and no autocorrelation.

4.4. Asymmetric Co-integration Test

Primarily based on the anticipated NARDL, a bound test of co-integration was used. The F-Statistic value was reported in Table 4. The reported value exceeds the upper bound value at a 5% level of significance. Concludingly, the null hypothesis of no cointegration can be rejected.

4.5. Testing The Presence of Asymmetry

The Wald test of asymmetry is essential in the context of cointegration. The Wald test of the asymmetry result is included in Table 5. Furthermore, the term “asymmetry” does not refer to equal means. Thus, Table 5 shows that the probability value is less than 5%, so the null hypothesis of no asymmetry can be rejected. It is concluded that coefficients are not equal and that the presence of asymmetry is confirmed.

Table 5.

Presence of Asymmetry.

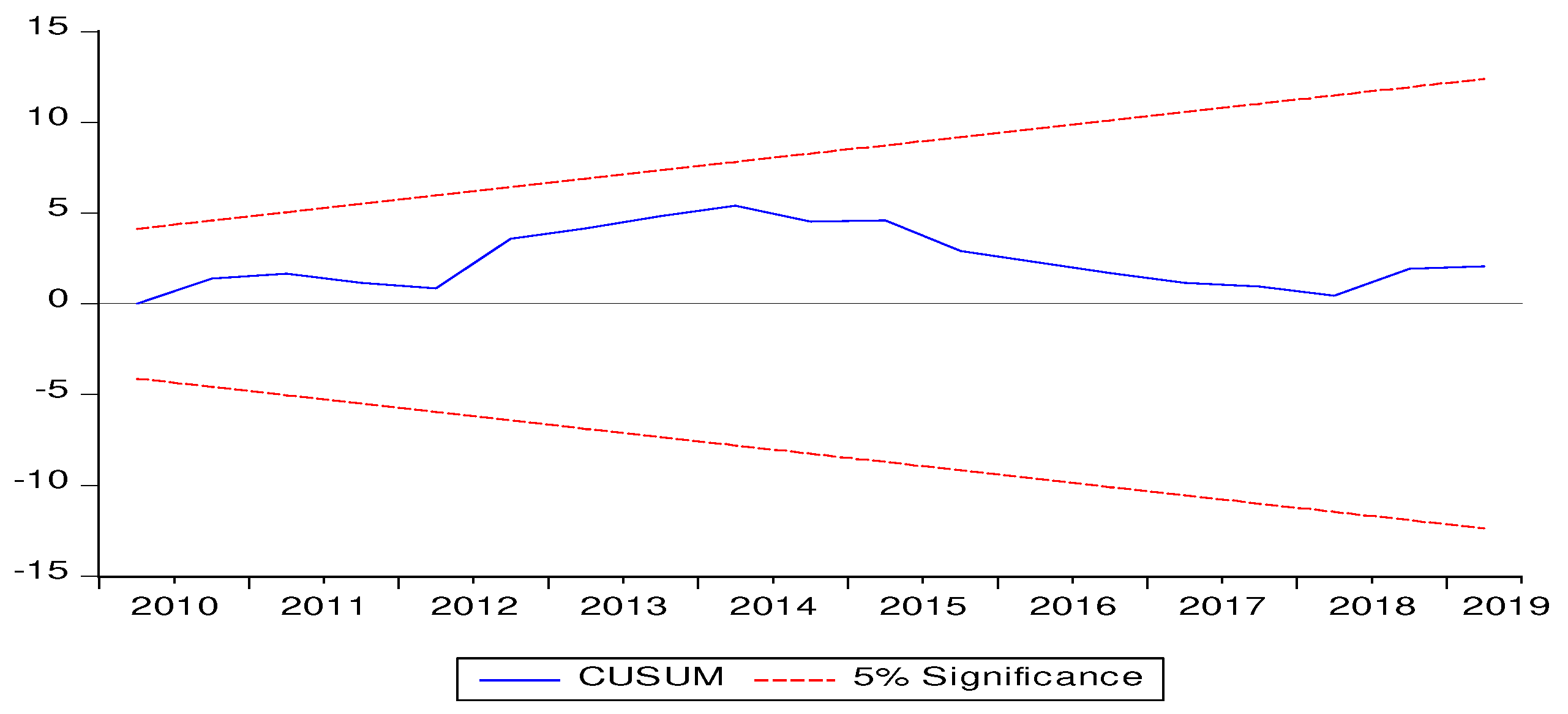

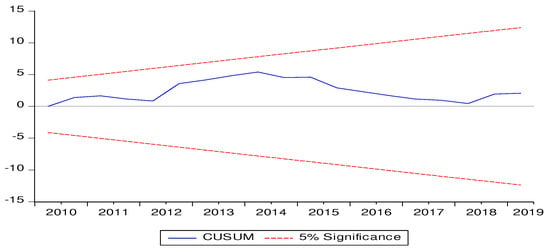

4.6. CUSUM and CUSUMQ Stability Graph

Brown, et al.; Pesaran and Pesaran [103,104] proposed the function of the CUSUM or CUSUMQ stability parameters test created by [103] following the coefficient estimation of the short and long run to inspect robustness. If the CUSUMQ or CUSUM line remains within the top and lower bounds of the CUSUM and CUSUMQ graphs, the estimated parameters are said to be stable. Figure 2 illustrate that the upper and lower bounds of the lines are both inside the CUSUM sta-bility graphs. On the other hand, both graphs show that the parameters are stable.

Figure 2.

CUSUM stability graphs.

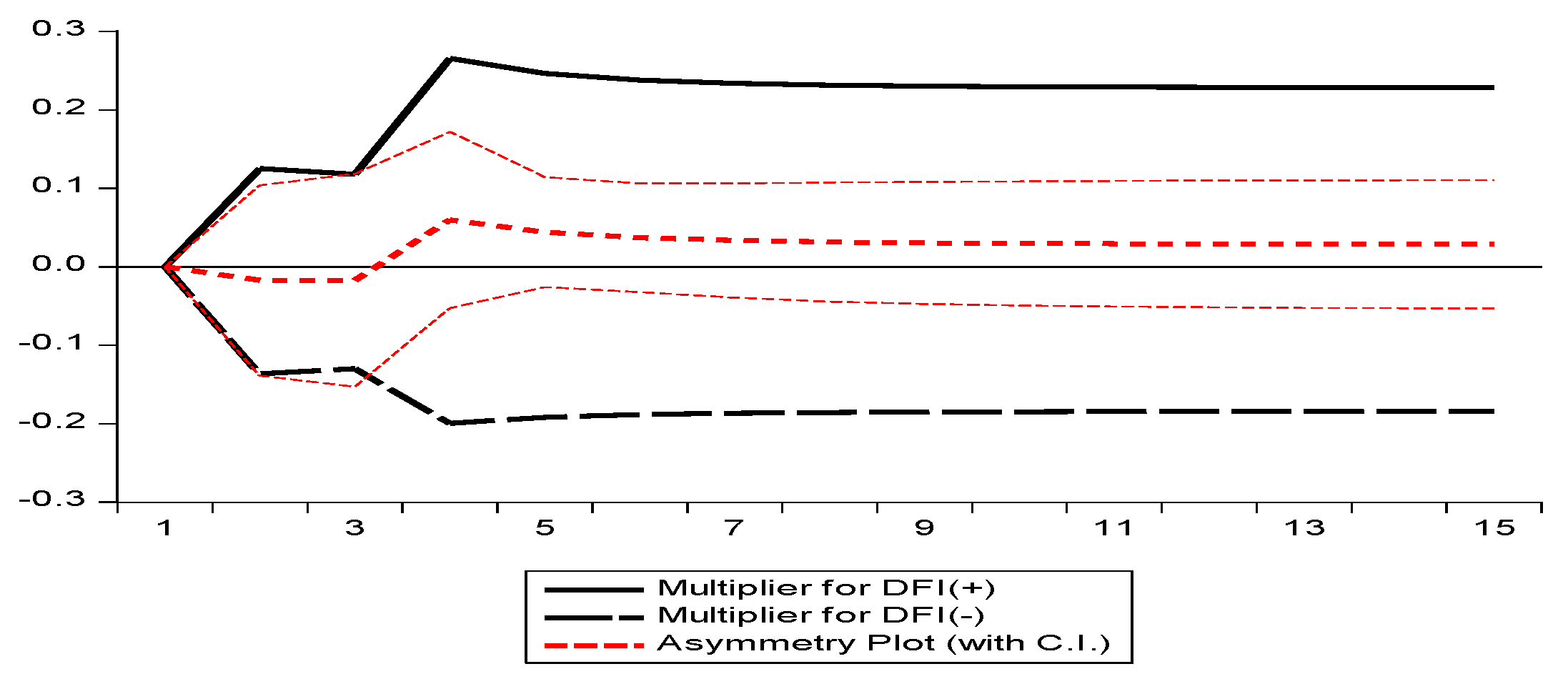

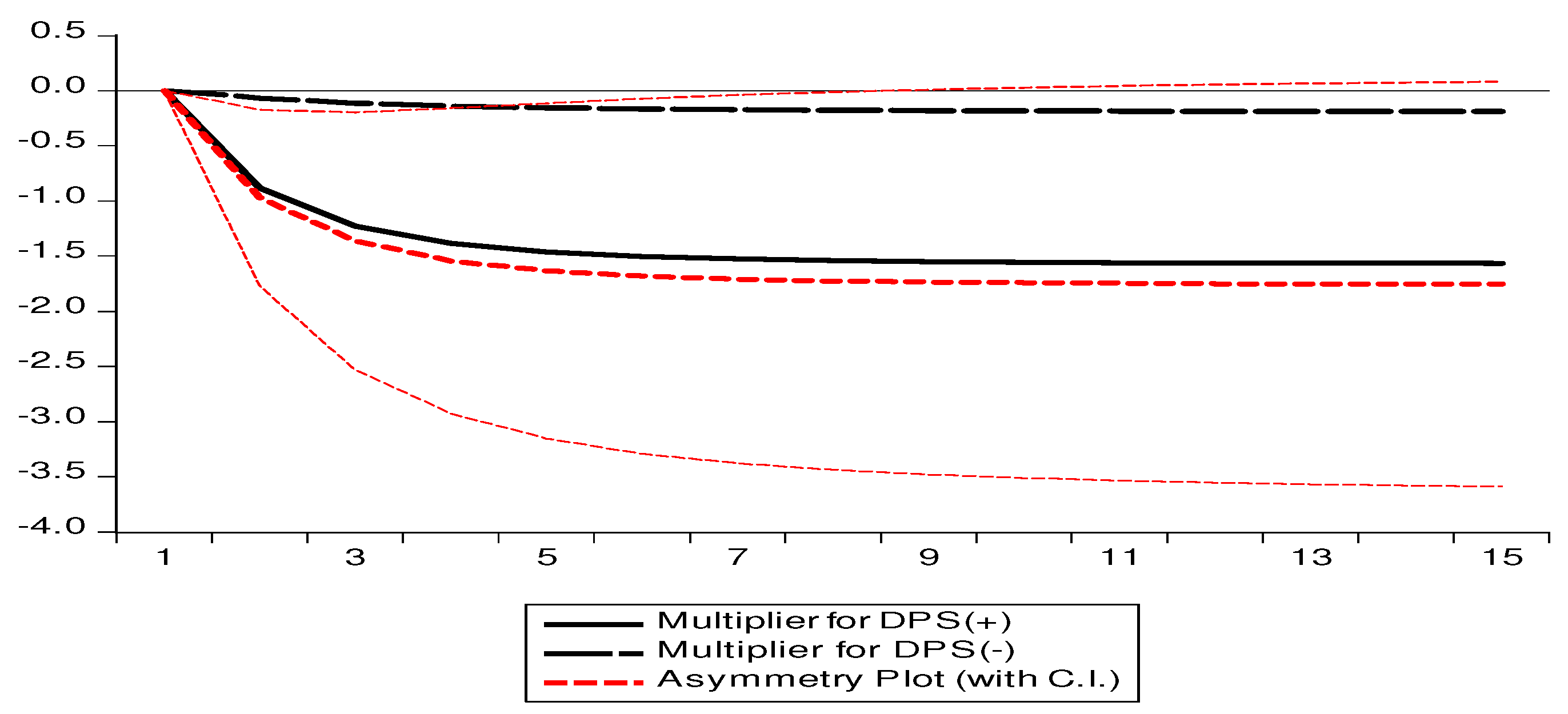

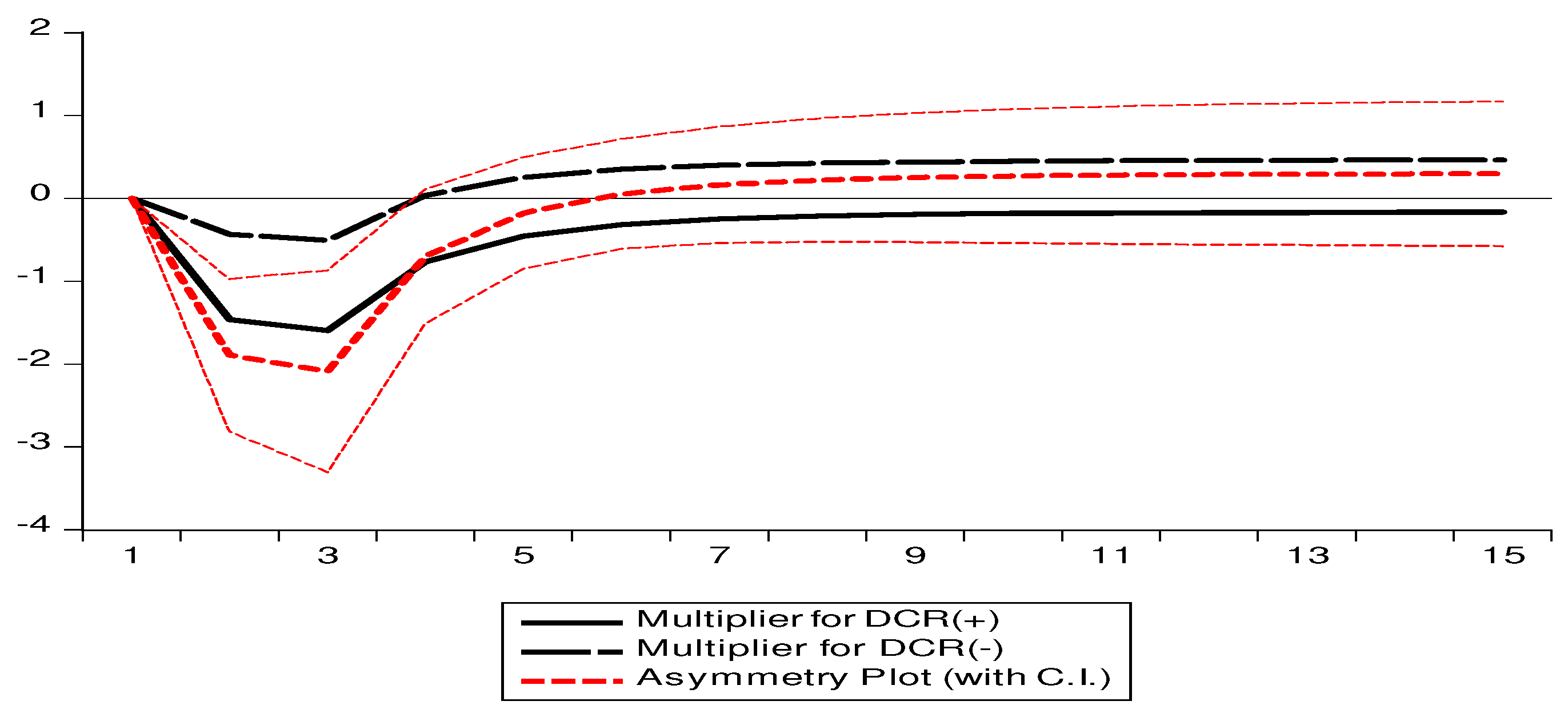

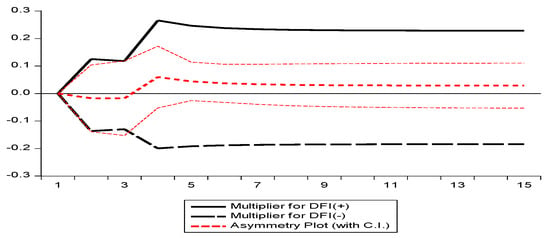

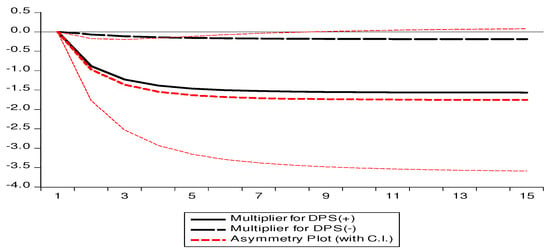

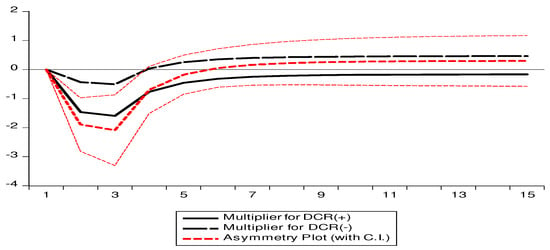

4.7. Dynamic Multiplier Graph

Figure 3 depicts a dynamic multiplier graph assessing the rectification of asymmetry in the current long-run equilibrium after passing to the innovative long-run equilibrium due to positive and negative shocks; a dynamic multiplier graph for NARDL is built as indicated in Figure 4. The asymmetry curves depicted above are the result of a variable linear combination of dynamic multipliers induced by both negative and positive PS increases, as well as rising tourism in Pakistan. The asymmetric corrections of positive and negative changes in curves confirm tourist responsiveness to positive and negative PS at a given period. Finally, Figure 5 demonstrated the DCR, where the positive PS shocks have a longer-term impact on tourism than negative PS shocks and go a line with its mean value.

Figure 3.

Dynamic multiplier graph. Note: The horizontal axis shows years and the vertical axis shows the magnitude of both kinds of positive and negative shocks.

Figure 4.

Dynamic multiplier graph.

Figure 5.

Dynamic multiplier graph. Note: The horizontal axis shows years and the vertical axis shows the magnitude of both kinds of positive and negative shocks.

5. Conclusions, Future Recommendations, and Policy Implications

The global tourism sector has been improved drastically and jointly with the globalization system and considerable upgrades and cost reductions, particularly in the transport sector. Undoubtedly, the great growth in the tourism region has the potential to influence economies throughout by encouraging private and non-private investments, enhancing the balance of payment, and creating jobs. Nevertheless, many social, monetary, political, and cultural elements could determinate tourist attractions. In this study, we have examined the impact of political stability on tourism, food prices, and crime rates in Pakistan.

To investigate the long-run connection amid the political stability, food inflation, crime rate, exchange rate, number of tourists, and receipts from tourism. For this purpose, political stability, tourism, food inflation exchange rate, number of tourists, and crime rate were used as variables. Multiple tests were used to measure the asymmetric relationship. First, the bound test of cointegration was used and the findings of the test suggest the presence of cointegration. Second, the Wald test of asymmetry was conducted to examine the asymmetry and the result suggested the presence of asymmetry. Third, the parameter stability test was conducted using CUSUM and CUSUMQ tests and the findings suggested the model stability. Finally, a dynamic multiplier graph was used to measure the correction in asymmetry and it was concluded that the positive PS shocks have a greater long-term influence on tourism than negative PS shocks. This indicates that political instability and politically motivated violence and security troubles significantly influence the development of the tourism sector. In these circumstances, the formation of an institutional and legal structure promoting political stability and retreating security concerns will also add to the development of the tourism sector.

In conclusion, tourism planning is critical for beneficial tourism development in politically uneven nations and it should be recognized as the underpinning of growth plans. During catastrophe management, the adverse repercussions of uncertainties should be sensibly weighed and dealt with in a friendly and compassionate style. This will surge the repayment of tourism and be attributed to the latent progression, which will increase the economic feat and offer sureness in impending political stability. Tourism plotting should be arranged by governments and the ruling classes in politically wobbly nations in search of economic advancement and a blossoming tourism economy. Hence, tourism, according to [105,106,107], can serve as a peacemaker.

Political leaders, governments, and policymakers must examine the following consequences in order to strengthen and sustain democracy. To develop a stable political system, Pakistan first requires strong leaders who can bring all segments of society to the table. Pakistan’s economy and prestige culture will gain from the leisure industry’s healthy recovery. Pakistan has a lot to offer the world’s wealthiest visitors, from the hospitality of its people to the depth of its cultural heritage. Regardless of northern Pakistan’s hidden gems and tourist potential, our government and culture have failed to recognize Pakistan’s true beauty. Security and infrastructure are two pressing issues that need a quick response. The policy level of the state disregards security concerns, infrastructure, and cultural impediments. First, the Malakand Division (including Swat, Dir, and Chitral) is accessible through an inoperable airport at Saidu Shareef. Similarly, Chitral’s tiny airfield cannot accommodate bigger aircrafts and PIA’s outdated fleet of ATR aircrafts has severe weather-related restrictions, causing flights to be unpredictable and unreliable. Second, for Pakistan to maintain healthy economic growth, sustained democracy, and continuous political power, changes are required, as political inconsistencies discourage investment in a society where public borrowing causes inflation and uneven growth, as documented by [108]. The Karakoram Highway (KKH) is the sole alternative option for autumn and winter season tourists; however, it passes via Bisham, Pattan, and Chilas from the Thakot Bridge across the Indus to Raikot Bridge (around 300 km). Additionally, the age-old impediments in the TattaPani Slide region between Chilas and the Raikot Bridge are hazardous to traverse. The administration of Gilgit-Baltistan has made no significant attempt to circumvent this backlog. A rail link would cause the entire enterprise to be extremely profitable; the China Pakistan Economic Corridor (CPEC) can be used for this purpose. All the roads leading from the KKH into the endlessly beautiful valleys are small, prone to mudslides, hazardous in bad weather, and are only accessible to four-wheel-drive cars. Indeed, Pakistan has plenty to offer the tourism sector due to its abundance of archaeological and cultural beauty. The above service industry has declined due to Pakistan’s lack of proper infrastructure, political turmoil, and uncertain economic figures. A comparison of Pakistan’s tourist industry with those of its surrounding nations and our study recommended tactics that may assist the government in identifying tourism’s industry weaknesses and developing plans to strengthen this segment. Finally, in order to establish a stable political system in Pakistan, effective leaders who can bring all facets of society to the table are required. Furthermore, policymakers must inculcate strong faith in the people and serve them uniformly for them to feel at ease as citizens of the state. Similarly, [109] discovered that the democratic system can stabilize the economic condition; once the political structure of the state has stabilized, prices will be passive and, thus, policymakers can control inflation.

Our study included all sorts of tourism in general, leaving much potential for further research on biodiversity, sporting, and environmentalism, for example. This study reviews the literature and solely addresses political instability, inflation, and crime rate variables. Lastly, it is essential to note that a variety of other variables convincing the tourism expansion in Pakistan and abroad. Future scholars might work on the linked topic by concentrating on one sort of tourism within Pakistan and the issue based on our investigation. Hence, it will require some time to properly assess COVID-19’s short- and long-term implications as it placed limitations on traveling abroad.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, A.R. (Abdul Rauf) and A.M.A.A.; Methodology, A.R. (Abdul Rauf), A.M.A.A. and S.S.; software, A.R. (Abdul Rauf), A.M.A.A. and A.R. (Asim Rafiq); validation, A.R. (Abdul Rauf), A.M.A.A. and S.A.; formal analysis, A.R. (Abdul Rauf), and A.M.A.A.; investigation, A.R. (Abdul Rauf) and A.M.A.A.; resources, A.R. (Abdul Rauf), A.M.A.A. and S.A.; data curation, A.R. (Abdul Rauf), A.R. (Asim Rafiq), and A.M.A.A.; writing—original draft preparation, A.R. (Abdul Rauf), and A.M.A.A.; writing—review and editing, A.R. (Abdul Rauf), A.R. (Asim Rafiq), A.M.A.A. and S.A.; visualization, A.R. (Abdul Rauf); supervision, A.R. (Asim Rafiq), and A.R. (Abdul Rauf); project administration, A.R. (Abdul Rauf) and A.M.A.A.; funding acquisition, A.R. (Abdul Rauf). All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

The study is supported by startup fund (Grant No. 2020R068) for introducing Talent in Nanjing University of Information Science and Technology, (NUIST), People’s Republic of China.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The data used in this study can be available on the request.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Rauf, A.; Ozturk, I.; Ahmad, F.; Shehzad, K.; Chandiao, A.A.; Irfan, M.; Abid, S.; Jinkai, L. Do tourism development, energy consumption and transportation demolish sustainable environments? Evidence from Chinese provinces. Sustainability 2021, 13, 12361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fayissa, B.; Nsiah, C.; Tadesse, B. Research note: Tourism and economic growth in Latin American countries—Further empirical evidence. Tour. Econ. 2011, 17, 1365–1373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Tourism Organization. International Tourism Highlights, 2019 Edition; UNWTO: Madrid, Spain, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Theocharous, A.L.; Seddighi, H.R. A model of tourism destination choice: A theoretical and empirical analysis. Tour. Manag. 2002, 23, 475–487. [Google Scholar]

- Hall, C.M. Tourism and Politics: Policy, Power and Place; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 1994; ISBN 0471949191. [Google Scholar]

- Mamoon, D.; Shield, R.; Javed, R.; Abbas, R.Z. Political Instability and Lessons for Pakistan: Case Study of 2014 PTI Sit in/Protests. J. Soc. Adm. Sci. 2017, 4, 27–37. [Google Scholar]

- Ranasinghe, R.; Deyshappriya, R. Analyzing the significance of tourism on Sri Lankan economy: An econometric analysis. Wayamba J. Manag. 2010, 1, 65–75. [Google Scholar]

- Khan, S.; Mahmud Arif, A.; Samad, A. Tourism problems in Pakistan: An analysis of earlier investigations. WALIA J. 2019, 35, 122–126. [Google Scholar]

- Rashid, W.; Shi, J.; Rahim, I.U.; Qasim, M.; Baloch, M.N.; Bohnett, E.; Yang, F.; Khan, I.; Ahmad, B. Modelling potential distribution of snow leopards in pamir, northern pakistan: Implications for human–snow leopard conflicts. Sustainability 2021, 13, 13229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, M.A.; Saeed, S. Twin deficits and saving-investment Nexus in Pakistan: Evidence from Feldstein-Horioka puzzle. J. Econ. Coop. Dev. 2012, 33, 1–36. [Google Scholar]

- Tiwari, A.K.; Shahbaz, M.; Adnan Hye, Q.M. The environmental Kuznets curve and the role of coal consumption in India: Cointegration and causality analysis in an open economy. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2013, 18, 519–527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Afolabi, L.O.; Abu Bakar, N.A. Causal Link between Trade, Political Instability, FDI and Economic Growth: Nigeria Evidence. J. Econ. Libr. 2016, 3, 100–110. [Google Scholar]

- Asteriou, D.; Price, S. Political instability and economic growth: UK time series evidence. Scott. J. Political Econ. 2001, 48, 383–399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sweidan, O.D. Political Instability and Economic Growth: Evidence from Jordan. Rev. Middle East Econ. Financ. 2016, 12, 279–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campos, N.F.; Karanasos, M.G.; Tan, B. Two to tangle: Financial development, political instability and economic growth in Argentina. J. Bank. Financ. 2012, 36, 290–304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Devereux, M.B.; Wen, J.F. Political instability, capital taxation, and growth. Eur. Econ. Rev. 1998, 42, 1635–1651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grochová, L.; Kouba, L. Elite Political Instability and Economic Growth: An Empirical Evidence from the Baltic States; Working Papers in Business and Economics; Mendel University: Brno, Czech Republic, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Butler, R.; Suntikul, W. Tourism and War; Routledge: London, UK, 2013; Volume 34, ISBN 0415674336. [Google Scholar]

- Moufakkir, O.; Kelly, I. Tourism, Progress and Peace; CABI: Wallingford, UK, 2010; ISBN 9781845936778. [Google Scholar]

- Adnan Hye, Q.M.; Ali Khan, R.E. Tourism-Led Growth Hypothesis: A Case Study of Pakistan. Asia Pac. J. Tour. Res. 2013, 18, 303–313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balcilar, M.; van Eyden, R.; Inglesi-Lotz, R.; Gupta, R. Time-varying linkages between tourism receipts and economic growth in South Africa. Appl. Econ. 2014, 46, 4381–4398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seghir, G.M.; Mostéfa, B.; Abbes, S.M.; Zakarya, G.Y. Tourism Spending-Economic Growth Causality in 49 Countries: A Dynamic Panel Data Approach. Procedia Econ. Financ. 2015, 23, 1613–1623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dogru, T.; Bulut, U. Is tourism an engine for economic recovery? Theory and empirical evidence. Tour. Manag. 2018, 67, 425–434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anoruo, E. Testing for linear and nonlinear causality between crude oil price changes and stock market returns. Int. J. Econ. Sci. Appl. Res. Provid. 2011, 4, 75–92. [Google Scholar]

- Bildirici, M.; Türkmen, C. The Chaotic Relationship between Oil Return, Gold, Silver and Copper Returns in TURKEY: Non-Linear ARDL and Augmented Non-linear Granger Causality. Procedia Soc. Behav. Sci. 2015, 210, 397–407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meo, M.S.; Chowdhury, M.A.F.; Shaikh, G.M.; Ali, M.; Masood Sheikh, S. Asymmetric impact of oil prices, exchange rate, and inflation on tourism demand in Pakistan: New evidence from nonlinear ARDL. Asia Pac. J. Tour. Res. 2018, 23, 408–422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alesina, A.; Perotti, R. Income distribution, political instability, and investment. Eur. Econ. Rev. 1996, 40, 1203–1228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mathews, R.L. Intergovernmental Relations in Australia; Angus & Robertson: Sydney, Australia, 1974; ISBN 0207129045. [Google Scholar]

- Hall, C.M.; Jenkins, J. Tourism and public policy. A Companion to Tourism; Blackwell Publishing Ltd.: Boston, MA, USA, 2004; pp. 525–540. [Google Scholar]

- Webster, C.; Ivanov, S.H. Tourism as a force for political stability. In The International Handbook on Tourism and Peace; Centre for Peace Research and Peace Education of the University Klagenfurt: Klagenfurt, Austria, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Haddad, C.; Nasr, A.; Ghida, E.; Al Ibrahim, H. How to Re-emerge as a Tourism Destination after a Period of Political Instability. In The Travel & Tourism Competitiveness Report; 2015; pp. 53–57. Available online: https://www3.weforum.org/docs/TT15/WEF_TTCR_Chapter1.3_2015.pdf (accessed on 1 June 2022).

- Richter, L.K. After political turmoil: The lessons of rebuilding tourism in three Asian countries. J. Travel Res. 1999, 38, 41–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Altinay, L.; Altinay, M.; Bicak, H.A. Political scenarios: The future of the North Cyprus tourism industry. Int. J. Contemp. Hosp. Manag. 2002, 14, 176–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bayar, Y.; Yener, B. Political stability and tourism sector development in Mediterranean countries: A panel cointegration and causality analysis. Eur. J. Tour. Res. 2019, 21, 23–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Causevic, S.; Lynch, P. Political (in) stability and its influence on tourism development. Tour. Manag. 2013, 34, 145–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fletcher, J.; Morakabati, Y. Tourism activity, terrorism and political instability within the Commonwealth: The cases of Fiji and Kenya. Int. J. Tour. Res. 2008, 10, 537–556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khandaker, S.; Islam, S.Z. International Tourism Demand and Macroeconomic Factors. Int. J. Econ. Financ. Issues 2017, 7, 389. [Google Scholar]

- Adeola, O.; Boso, N.; Evans, O. Drivers of international tourism demand in Africa. Bus. Econ. 2018, 53, 25–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hai, M.A.; Chik, A.R. Political stability: Country Image for tourism industry in Bangladesh. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Social Science, Economics and Art, Putrajaya, Malaysia, 2–3 January 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Farmaki, A.; Altinay, L.; Botterill, D.; Hilke, S. Politics and sustainable tourism: The case of cyprus. Tour. Manag. 2015, 47, 178–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tosun, C.; Timothy, D.J. Shortcomings in planning approaches to tourism development in developing countries: The case of Turkey. Int. J. Contemp. Hosp. Manag. 2001, 13, 352–359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ingram, H.; Tabari, S.; Watthanakhomprathip, W. The impact of political instability on tourism: Case of Thailand. Worldw. Hosp. Tour. Themes 2013, 5, 92–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baig, S.; Zehra, S. China-Pakistan economic corridor, governance, and tourism nexus: Evidence from Gilgit-Baltistan, Pakistan. Curr. Issues Tour. 2020, 23, 2884–2889. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, K. Tourism downfall: Sectarianism an apparent major cause, in Gilgit-Baltistan (GB), Pakistan. J. Political Stud. 2012, 19, 155. [Google Scholar]

- Laborde, D.; Lakatos, C.; Martin, W. Poverty Impact of Food Price Shocks and Policies; World Bank Policy Research Working Paper 8724; World Bank: Washington, DC, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Ivanic, M.; Martin, W. Implications of higher global food prices for poverty in low-income countries. Agric. Econ. 2008, 39, 405–416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- FAO. The State of Food Security and Nutrition in the World 2018. Building Climate Resilience for Food Security and Nutrition–Policy Support and Governance; FAO: Rome, Italy, 2018; Volume 7. [Google Scholar]

- Henderson, J.C. Food tourism reviewed. Br. Food J. 2009, 111, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robinson, R.N.S.; Getz, D. Profiling potential food tourists: An Australian study. Br. Food J. 2014, 116, 690–706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsai, C.T.S.; Wang, Y.C. Experiential value in branding food tourism. J. Destin. Mark. Manag. 2017, 6, 56–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bessiere, J. Local development and heritage: Traditional food and cuisine as tourist attractions in rural areas. Sociol. Rural 1998, 38, 21–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, T.Y.; Hsu, J.M. Development framework for tourism and hospitality in higher vocational education in Taiwan. J. Hosp. Leis. Sport Tour. Educ. 2010, 9, 101–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheth, J.N.; Newman, B.I.; Gross, B.L. Why we buy what we buy: A theory of consumption values. J. Bus. Res. 1991, 22, 159–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sin, L.Y.M.; So, S.L.M.; Yau, O.H.M.; Kwong, K. Chinese women at the crossroads: An empirical study on their role orientations and consumption values in Chinese society. J. Consum. Mark. 2001, 18, 348–367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Awuni, J.A.; Du, J. Sustainable Consumption in Chinese Cities: Green Purchasing Intentions of Young Adults Based on the Theory of Consumption Values. Sustain. Dev. 2016, 24, 124–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gonçalves, H.M.; Lourenço, T.F.; Silva, G.M. Green buying behavior and the theory of consumption values: A fuzzy-set approach. J. Bus. Res. 2016, 69, 1484–1491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grönroos, C. Adopting a service logic for marketing. Mark. Theory 2006, 6, 317–333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yeo, B.L.; Mohamed, R.H.N.; Muda, M. A Study of Malaysian Customers Purchase Motivation of Halal Cosmetics Retail Products: Examining Theory of Consumption Value and Customer Satisfaction. Procedia Econ. Financ. 2016, 37, 176–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, P.; Soutar, G.N. Value, Satisfaction And Behavioral Intentions in an Adventure Tourism Context. Ann. Tour. Res. 2009, 36, 413–438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, H.J.; Rabolt, N.J. Cultural value, consumption value, and global brand image: A cross-national study. Psychol. Mark. 2009, 26, 714–735. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holcomb, J.; Pizam, A. Do incidents of theft at tourist destinations have a negative effect on tourists’ decisions to travel to affected destinations? In Tourism, Security and Safety: From Theory to Practice, 4th ed.; Elsevier: Boston, MA, USA, 2006; pp. 105–124. [Google Scholar]

- Pizam, A.; Mansfeld, Y. Toward a Theory of Tourism Security. In Tourism, Security and Safety: From Theory to Practice, 4th ed.; 2006; pp. 1–27. Available online: https://www.cabdirect.org/cabdirect/abstract/20053217370 (accessed on 1 June 2022).

- Brown, W.J. Examining Four Processes of Audience Involvement With Media Personae: Transportation, Parasocial Interaction, Identification, and Worship. Commun. Theory 2015, 25, 259–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mataković, H.; Cunjak Mataković, I. The impact of crime on security in tourism. Secur. Def. Q. 2019, 27, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghaderi, Z.; Saboori, B.; Khoshkam, M. Does security matter in tourism demand? Curr. Issues Tour. 2017, 20, 552–565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prideaux, B.R. Korean outbound tourism: Australia’s response. J. Travel Tour. Mark. 1997, 7, 93–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, L.E.; Felson, M. Social Change and Crime Rate Trends: A Routine Activity Approach. Am. Sociol. Rev. 1979, 44, 588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crotts, J.C. Theoretical perspectives on tourist criminal victimisation. J. Tour. Stud. 1996, 7, 2–9. [Google Scholar]

- Becker, G.S. Crime and Punishment: An Economic Approach. J. Political Econ. 1968, 76, 169–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montolio, D.; Planells-Struse, S. Does Tourism Boost Criminal Activity? Evidence From a Top Touristic Country. Crime Delinq. 2016, 62, 1597–1623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smeral, E. International tourism demand and the business cycle. Ann. Tour. Res. 2012, 39, 379–400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Granger, C.W.J.; Yoon, G. Hidden Cointegration; Economics Working Papers; University of California: Berkeley, CA, USA, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Dhaoui, A.; Bacha, S. Investor emotional biases and trading volume’s asymmetric response: A non-linear ARDL approach tested in S&P500 stock market. Cogent Econ. Financ. 2017, 5, 1274225. [Google Scholar]

- Ibrahim, M.H. Oil and food prices in Malaysia: A nonlinear ARDL analysis. Agric. Food Econ. 2015, 3, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koutroulis, A.; Panagopoulos, Y.; Tsouma, E. Asymmetry in the response of unemployment to output changes in Greece: Evidence from hidden co-integration. J. Econ. Asymmetries 2016, 13, 81–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shin, Y.; Yu, B.; Greenwood-Nimmo, M. Modelling Asymmetric Cointegration and Dynamic Multipliers in a Nonlinear ARDL Framework. In Festschrift in Honor of Peter Schmidt; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2014; pp. 281–314. [Google Scholar]

- Pesaran, M.H.; Shin, Y.; Pesaran, M.H.; Shin, Y. An autoregressive distributed-lag modelling approach to cointegration analysis. Econom. Soc. Monogr. 1999, 31, 371–413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shahbaz, M.; Islam, F. Financial Development and Income Inequality in Pakistan: An Application of ARDL Approach. J. Econ. Dev. 2011, 36, 35–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ouattara, B. Modelling the Long Run Determinants of Private Investment in Senegal; Centre for Research in Economic Development and International Trade: Washington, DC, USA, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Phillips, P.C.B.; Perron, P. Testing for a unit root in time series regression. Biometrika 1988, 75, 335–346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Im, K.S.; Pesaran, M.H.; Shin, Y. Testing for unit roots in heterogeneous panels. J. Econom. 2003, 115, 53–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maddala, G.S.; Wu, S. A Comparative Study of Unit Root Tests with Panel Data and a New Simple Test. Oxf. Bull. Econ. Stat. 1999, 61, 631–652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ajmi, A.N.; Hammoudeh, S.; Nguyen, D.K.; Sarafrazi, S. How strong are the causal relationships between Islamic stock markets and conventional financial systems? Evidence from linear and nonlinear tests. J. Int. Financ. Mark. Inst. Money 2014, 28, 213–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hendry, D.F. Dynamic Econometrics; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 1995; ISBN 0198283164. [Google Scholar]

- Ivanov, S.; Gavrilina, M.; Webster, C.; Ralko, V. Impacts of political instability on the tourism industry in Ukraine. J. Policy Res. Tour. Leis. Events 2017, 9, 100–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tomczewska-popowycz, N.; Quirini-popławski, Ł. Political instability equals the collapse of tourism in Ukraine? Sustainability 2021, 13, 4126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohammed, A.M.; Sookram, S. The impact of crime on tourist arrivals—A comparative analysis of Jamaica and Trinidad and Tobago. Soc. Econ. Stud. 2015, 64, 153–176. [Google Scholar]

- Santana, G. Globalisation, safety and national security. In Tourism in the Age of Globalisation; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2005; pp. 227–255. [Google Scholar]

- Vellas, F.; Becherel, L. International Tourism: An Economic Perspective; Bloomsbury Publishing: London, UK, 1995; ISBN 1349240745. [Google Scholar]

- Richter, L.K.; Waugh, W.L. Terrorism and tourism as logical companions. Tour. Manag. 1986, 7, 230–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edgell, D.L. Tourism Policy: The Next Millennium; Sagamore Publishing: Champaign, IL, USA, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Timothy, D.J. Tourism and Political Boundaries; Routledge: London, UK, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Knowles, T.; Diamantis, D.; El-Mourhabi, J.B. The Globalization of Tourism and Hospitality a Strategic Perspective; Wakefield Press: Adelaide, Australia, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Baker, D.; Stockton, S. Tourism and Crime in America:: A Preliminary Assessment of the Relationship between the Number of Tourists and Crime in two Major American Tourist Cities. Ijssth 2014, 1, 1–25. [Google Scholar]

- Glensor, R.W.; Peak, K.J. Crimes against Tourists; US Department of Justice, Office of Community Oriented Policing Services: New York, NY, USA, 2004; ISBN 1932582363.

- Jones, C.B. Tourism impacts of the Los Angeles civil disturbances. In Proceedings of the 24th Annual Conference of the Travel and Tourism Research Association, Vancouver, BC, Canada, 11 June 1993; Volume 11. [Google Scholar]

- Bayramov, E.; Abdullayev, A. Effects of political conflict and terrorism on tourism: How crisis has challenged Turkey’s tourism develoment. Chall. Natl. Int. Econ. Policies 2018, 2018, 160–175. [Google Scholar]

- Elshaer, I.A.; Saad, S.K. Political instability and tourism in Egypt: Exploring survivors’ attitudes after downsizing. J. Policy Res. Tour. Leis. Events 2017, 9, 3–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hall, C.M.; O’Sullivan, V. Tourism, Political Stability and Violence. Available online: https://scholar.google.com/scholar_lookup?title=Tourism%2C%20political%20stability%20and%20violence&publication_year=1996&author=C.%20Hall&author=V.%20O%27Sullivan (accessed on 1 June 2022).

- Alleyne, D.; Boxill, I. The impact of crime on tourist arrivals in Jamaica. Int. J. Tour. Res. 2003, 5, 381–391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neumayer, E. The Impact of Political Violence on Tourism: Dynamic Cross-national Estimation. J. Confl. Resolut. 2004, 48, 259–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Llorca-Vivero, R. Terrorism and International Tourism: New Evidence. Def. Peace Econ. 2008, 19, 169–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, R.L.; Durbin, J.; Evans, J.M. Techniques for Testing the Constancy of Regression Relationships Over Time. J. R. Stat. Soc. Ser. B 1975, 37, 149–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pesaran, M.H.; Pesaran, B. Working with Microfit 4.0: An Introduction to Econometrics; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- D’Amore, L.J. Tourism—A vital force for peace. Tour. Manag. 1988, 9, 151–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.S.; Prideaux, B. Tourism, peace, politics and ideology: Impacts of the Mt. Gumgang tour project in the Korean Peninsula. Tour. Manag. 2003, 24, 675–685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- WTO. Tourism Can help Bring Peace in the Middle East Says WTO Secretary-General. Available online: https://www.hospitalitynet.org/news/4018704.html (accessed on 1 June 2022).

- Memon, A.P.; Memon, K.S.; Shaikh, S.; Memon, F. Political Instability: A case study of Pakistan. J. Political Stud. 2011, 18, 31. [Google Scholar]

- Suhail, B.; Qing, W.L. The Impact of Political Instability on Economic Growth in Pakistan. Rev. Argent. Clínica Psicológica 2021, 2, 189–199. Available online: https://www.revistaclinicapsicologica.com/data-cms/articles/20210329050219pmSSCI-589.pdf (accessed on 1 June 2022).

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).