Abstract

It is a positive phenomenon that more and more studies are being published on the diverse relationship between accessibility and tourism nowadays. This indicates that now at least tourism researchers are showing an interest in the examination of the different aspects of accessibility. Nevertheless, it is a well-known fact that service providers still do have much room for development in this respect. It is sad the examinations mentioned practically totally neglect the definition of accessibility from a philosophical perspective—or its need to be defined, so evidently its applicability in practice and its empirically justifiable positive impacts are not discussed, either, though in the authors’ view it is a prerequisite for the realisation of a traveller’s good and independent experiences. Unfortunately, very little is said in the previously mentioned scrutinies about the philosophy of accessibility which, in the authors’ opinion, is a prerequisite for the accomplishment of adequate accessibility. Coming from all these and also on the ground of their previous researches, and also from the international empirical research conducted in five countries on the travel habits of people with disabilities by the authors, they are convinced that accessibility in itself shows, and leads to crisis phenomena, because the spirit of accessibility is simply missing from both the professional and everyday practical thinking. One explicit manifestation of this is the fact that travel becomes free from experience as a result of partial accessibility—or it generates “specific experiences” that can be interpreted as the negative pole of Michalkó’s paradigm of beatific travel. The conclusion of the paper is that the creation of the paradigm of fundamental accessibility is a justified must.

1. Introduction

The accessibility attitude seems to be restricted to technical solutions in tourism presently [1]. The examinations of the authors aim, among other things, at completing the standard paradigm of accessibility with a new intellectual dimension, which they hope will lead to the birth of a new paradigm of accessibility. The first step of this process is the “elevation” of accessibility from the narrow interpretation range of disability to the space of complete existence in which all people move and travel, interpreting this space as a fundamental system element [2,3,4].

The authors’ researches follow two paths, and this paper is not an exception from this, either. One focal point is life and Buddhist philosophy that integrates the spirit of philosophy as a life-practice and community shaping force, hallmarked by Pierre Hadot (What is Ancient Philosophy?) [5], into modern research and scrutiny methodology, and also mobilises and integrates the philosophical essence of mutual assistance as a driving force of evolution. The other focal point is the academic, empirical research that is most compatible with the existing standards: analysing the findings of an international survey, the paper highlights a basic attitude of people living with disabilities—almost totally independent of their socio-cultural embeddedness, i.e., the fact that they definitely reject travel solutions that are tailor-made for them, and accordingly are discriminative in the opinion of the majority of respondents. The authors emphasise that the research findings justify the fact that accessibility has a two-fold approach: technical accessibility and fundamental accessibility. By “technical accessibility”, the authors mean the act of making objects and experiences accessible; fundamental accessibility is much broader in the sense that it relates to the state of being barrier-free in all aspects. Technical accessibility in this sense is the means of achieving fundamental, “real” accessibility. It is built around the intellectual or around a basic human activity, from which technical accessibility was detached as an independent action, which, however, is incomprehensible without fundamental accessibility. It is actually a split phenomenon: from the basic concept of fundamental accessibility, technical accessibility was split by modern man and society as a solely technical-technological attitude that is void of the intellectual meaning of fundamental accessibility. They have differentiated meanings and practical contents at the same time, i.e., these aspects are different from each other from a paradigmatypic aspect, though it must also be said that from a philosophical aspect, fundamental accessibility (being barrier-free) organises the structure of the technological existence of technical accessibility (making it barrier-free).

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Philosophical—Philoscopical Inquiry

First of all, the specific philosophical “analytics”: the scrutiny is of a philoscopic character, which refers, on the one hand, to the application of existing knowledge to its placement in a new context and the discovery of new interfaces, and on the other hand, to the re-interpretation of thinking, and closely related to this, of the concepts of the process of creation—and finally draws attention to the need of repeated re-discovery of all these [6,7].

Thomas Kuhn in his main work, the revolutionary book The Structure of Scientific Revolutions (2012) [8], emphasises the following changes of the base structure in connection with paradigm shifts (without aiming at completion): in his definition, dominant “research directions” are those frameworks accepted and used by the mainstream (with a modern expression) which determine the research trends and methodology of a given discipline. A paradigm shift takes place when dominant opinion-makers of a scientific community, in their personalities and ways of thinking—i.e., theories and applied “actions”—specify new focal points significantly different from the previous ones, and when this new “cartography” of the scrutinies replaces the previous ones.

This brief science philosophy and history outlook challenges the intention of the authors to trigger a paradigm shift, knowing that Kuhn’s model of a paradigm shift can mostly be related to large distances in time and space within academic life. Furthermore, the change of the main research directions and statements takes into account, as a basis condition, the initial resistance of the group active in the given discipline and seeing itself as the elite; this is just why it can be called revolutionary [9].

The authors of this paper, connecting to the philosophical thoughts of Feyerabend, believe that Kuhn’s science philosophy paradigm in itself should have been revolutionarily altered at the very beginning of its creation and publication, considering that it accepts the existence of the prevailing paradigm as self-evident, and that the academic structure replacing it integrates those partial elements of the replaced philosophy that it considers relevant, then having itself elevated to the “pulpit” of the previous one, as a new dominant way of thinking, by the old-new elite of the academics dominant in the scientific community.

In the frameworks of this paper, paradigms are seen as relevant to, but not rivalling, the formalised knowledge collection and analysis systems with science philosophy foundations that are related not hierarchically to each other but to the possible ways of examining respective disciplines [10,11].

Neither providing accessibility nor being accessible seems to have achieved the right of sovereign existence in any discipline. This is also true for disability science focused on the two areas mentioned above. Even the experts of this relatively novel research field see technical accessibility as a sort of responsibility that derives from the level of development of a society, and it is basically the possibility of the technical implementation that is seen as researchable and relevant. The authors hereby remark that in the second part of the paper, a section that is focused on the analysis of the findings of a questionnaire survey compatible with the mainstream research methodologies conducted in five European countries with a specific focus on the travel habits of people with disabilities, an attempt will be made for the discovery of the practical, analysable and measurable (also by travel sciences) aspects of the philosophical differences of fundamental accessibility (no barriers at all) and technical accessibility (creating this state). Finally, the authors draw attention to the still overwhelmingly negative consequence of differentiating fundamental accessibility from technical accessibility.

It should be more appropriate to talk about a paradigm-making intention in this duality of accessibility (fundamental and technical accessibility) since paradigms are considered resilient frameworks, among other things [4,12].

The necessity of the shift indicated in the title of the paper, however, is also evident, as regards the further thinking of the philosophical anthropology of man. In several previously published papers (e.g., [6]), authors projected a more detailed elaboration and mapping of the character of humans, providing technical accessibility. From the aspects of the science of travel, both philosophy-based extensions of concepts and approaches are synergic, considering that modern-age travel behaviour and the horizon of technical accessibility of the supply, built on this and said to be experience-generating, is becoming a more and more researched area in both the Hungarian and international literature [13]. As the COVID-19 pandemic created extra time for both the expansion and the deepening of our previous research foci, it can be said that the interpretation area of full accessibility used by the authors, and recommended to be used by a broader research community, can partially or fully re-write the relationship of humans as creatures travelling in existence [14], and Homo sapiens sapiens, a creature wishing to get experiences in space, to the nature that these creatures think that they rule.

The starting point is the brief statement of the philosophical interpretation frameworks of the three thinkings, focusing on the (1) existential philosophy approach: [15,16,17,18] who primarily describe, and apply in their philosophies, the travel dimensions of the experience of existence implicitly, which is an approach that is preferred by the authors of the paper. The authors are also aware, though, that, e.g., Sartre [19] and Lévi-Strauss [20], and even Merleau-Ponty [21], explicitly featured travel during their works, but their approach is less favoured in this paper because the authors’ primary objective is not a contribution to the philosophy of travel but to focus on the holistic relationship between travel and philosophy. Social philosophy interpretations were not included in the scrutinies of the paper, either, for the same reason. It must be remarked that the authors could not, and did not want to, outline a complex “anthology” of Western philosophies (also for the mere lack of space), as such an endeavour would require at least three extended papers. (2) Attention was also paid to applied philosophy [5,9] and last, but not least, to (3) the essence of the Buddhist worldview [22,23]. All three philosophical approaches and dimensions introduced by the authors contain an explicit and implicit form the originally symbiotic organogram of both humans creating technical accessibility and the notion of fundamental accessibility.

Heidegger’s masterpiece Being and Time is one of the most important works of European philosophy since Plato and Aristotle [24]; this “travel book” is basically an ontological approach to discovering existence—as the authors see, Heidegger’s essay entitled “The end of philosophy and the task of thinking” [25] explicitly contains the ontological necessity of the practice of travelling, the positions of the relationship of humans and existence to, as it could be said now, a post-metaphysical level, i.e., it considers the duality of existence and existing, taken as natural, to be simply artificial. Heidegger, just for this reason, dates the end of philosophy to the “appearance” of Socrates. The reason for Heidegger doing this is the fact that in his interpretation, it was after Socrates that among European philosophers the metaphysical view was born, according to which humans, as existing creatures, interpret themselves in existence, as an independent and sovereign component thereof [26]. With all due respect, the authors must challenge Heidegger’s conclusions, as they have come to the conclusion, just with the analysis of one of the original statements of Plato’s philosophy, that the travelling character of humans can be “justified” as their basic existential characteristic from both epistemological and ontological aspects.

The loss of the symbiotic human figure manifested in the androgynous view of Plato’s philosophy sort of predestines humans for travel in existence in the following way. The former single unit split by divine wrath keeps on searching for their companion [27]. In this interpretation, humans are also travelling creatures in a philosophical sense. Of course, the male–female dichotomy that has probably piled as cultural alluvium upon the original image does not meet the original philosophical message; the academy-founding Greek philosopher may have referred to the appearance of the dichotomy of the intellectual and physical entities defined later in Hegel’s works [28].

Actually, giving a new meaning of hermeneutical character defined in the above paragraph, although it contains some criticism concerning Heidegger, is still directly linked to the philosophical guideline of the “philosopher of the Black Forest”, since we cannot be satisfied with merely rewording the messages of texts; instead, we must strive for the discovery of the original source again and again, when interpreting a certain idea and conceptual framework [29].

On this basis, similarly to Heidegger, Jaspers and Bergson, the authors also interpret the practical and theoretical frameworks of philosophy as the intellectual maxima of the nature-discovering character of humans. In this practice-oriented mode, further elaborated upon and called philoscopic by the authors [7], the examiner and the examinee do not differ from each other, i.e., the real distinction of ontology and epistemology is just as unimaginable as the existence of the meta-world separated from the physical world. Thus, metaphysics is an artificial concept that has basically receded from the original source [30], the rediscovery of which was defined by Heidegger as an indispensable hermeneutical task [17]. We note that it is far beyond the scope of this paper to look more closely at Derrida’s ideas on deconstruction, which the authors argue are directly related to the ‘philosophy of being’ in the philosophy of emptiness, and thus go well beyond the message of Heidegger and Gadamer on the need to discover the original source. It is well known that Derrida is not satisfied with merely examining the origin of concepts from being, because, according to him, concepts do not stand in a stable, so to speak substantive and unidirectional relation to being, but rather, when a new point of connection is discovered, we are constantly witnessing new points of connection, building on and interconnecting with each other [31]. Last but not least, it should be noted that, beyond the view of emptiness, the practised philosopher may also discover a close connection with the philosophical investigations of Bergson and Deleuze [18,32]. In this view, humankind, according to the interpretation of the authors, is getting further and further away from the original source of the concept and seems to lose the fundaments of its own intellectual fulfilment [33]. In the authors’ interpretation this also means that the epicentre of the technology-centred development boom has plucked humans, originally seeing nature as their home and as equal to them, from their natural medium, i.e., the fundamental accessibility efforts as part of his original character were degraded to technical accessibility efforts. In addition, the transformations of the environment of existence, seen as technical accessibility progress, are now turbulently posing almost insurmountable obstacles to present societies.

Navigating back to the mainstream of existential philosophy, we cannot help finding Heidegger’s quite statuesque pictures of the relationship of humans and tools that are handy or at hand on the unfurling philosophical horizon of fundamental and technical accessibility [34]. To sum it up briefly: what is handy is a tool that is created by a human hand, driven by intellectuality, and so can be taken as quasi the natural expansion of the upper limb of the creator. This is called hereinafter an organic tool. What is at hand is the opposite; it is merely a technical tool that, although being available for humans, is void in the philosophical sense of the capacity of the human spirit to enlighten existence. We are surrounded by a mass of alienated subjects which do serve our convenience in the functional sense, but are dead objects in themselves, in an ever-growing quantity, paving the ways of humankind longing for sustainability and suffering from forgetting their humanity [7,35].

The authors are convinced that “travel compulsion”, now filtering deep down into societies, can also be projected on the philosophical axis of being handy and being at hand. Michalkó [36] in his book analysing the beatific nature of travel implicitly refers to the difference implied when he says that travel itself does not necessarily contain beatific elements. These appear, as elements being handy, i.e., integrant and inspiring experiences with emotional content, if travellers become committed to and capable of the acquisition of these skills and of self-fulfilment. For reasons of space, the philosophical message of happiness cannot be further analysed in this paper, but it has been referred to as a driving force of experiences and remembrance.

On these grounds, the implementation of more and more typical mass travels as a mass phenomenon degrading the discovery of existence is seen as an ordinary tool at hand, made technically accessible by a consumption generator.

It may not be an exaggeration to say that the ever-intensifying “fashion” of accessibility is exponentially increasing the number of barriers in our existential environment, acts as a sort of antimatter in the physical environment of humankind, i.e., seeing both the environment and humans who require technical accessibility as objects to be conquered and ruled.

The authors are convinced that the creation of the forecasted accessibility paradigm does contribute to a large extent to the elimination of the postmodern maxims of objectification [37,38] in the following way: humans, naturally social animals, do not necessarily have to see obstacles as “barriers” jeopardising their mere existence and thus hardships to be eliminated as described; these barriers can also be identified as opportunities [39]. They are opportunities in the intellectual and physical sense of the word, as it is just the understanding of the obstacles that leads to the progress of cooperation capacity, i.e., social fabric, and individual capacities, i.e., individuality. Barriers in their philosophical interpretation are carriers of the resultants of both potentials and topicality, possibly becoming this way mementos of the emptiness character of existence, actually [7,22]. The philosophical school of the study of emptiness—and its founder, thinker Nagarjuna who lived in India in the 2nd century A.D.—says that things can only exist in mutual correlations. Accordingly, nothing can stand in itself; things in this sense have an empty character. Against the relativity of things stands the concretion of the things palpable by organoleptic sensation, so that the nature of the respective object should be visible in the process and should not get dissolved in a general self-being existence (c.f. Whitehead [40]). Objects and emptiness can always be examined in relation to specific objects just experienced, only!

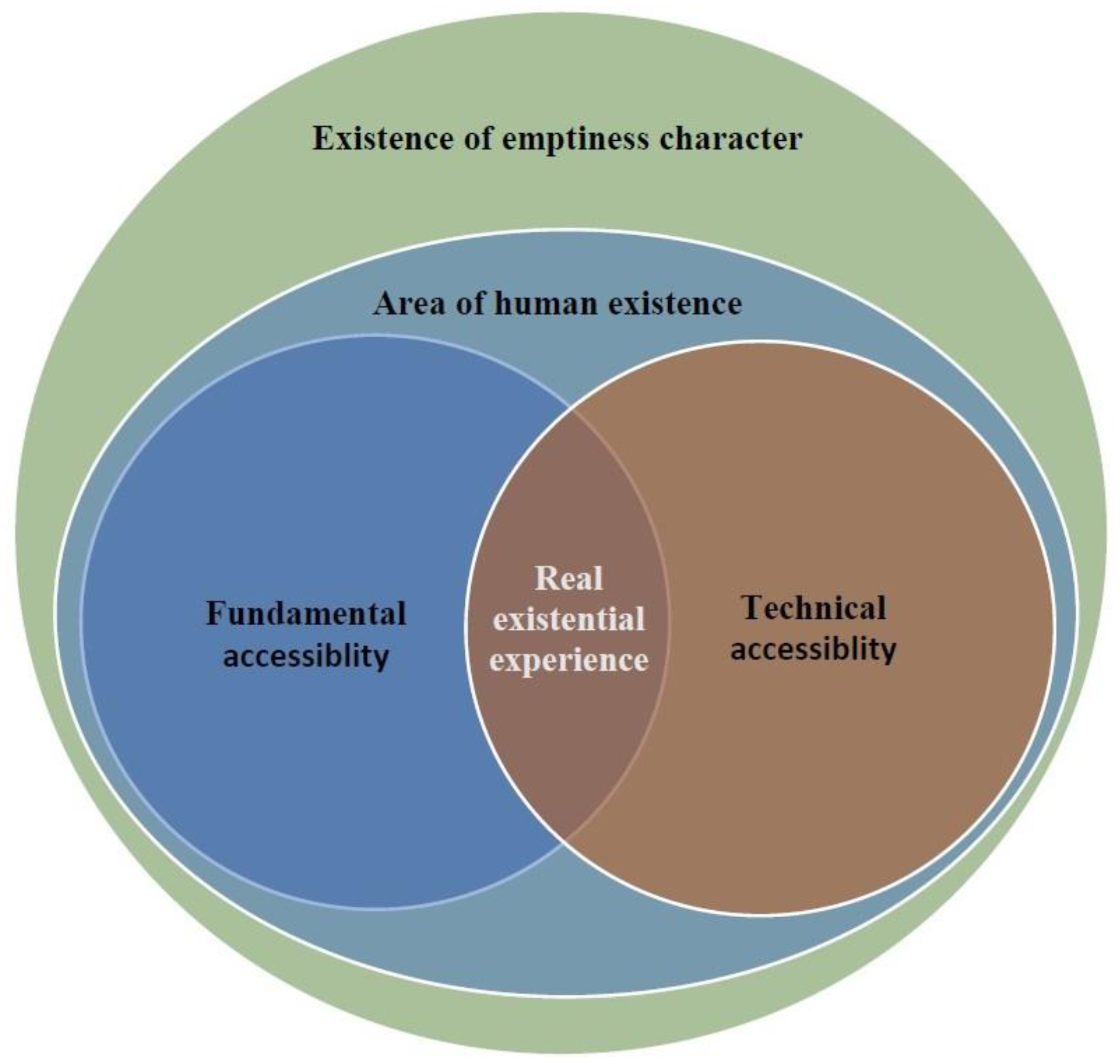

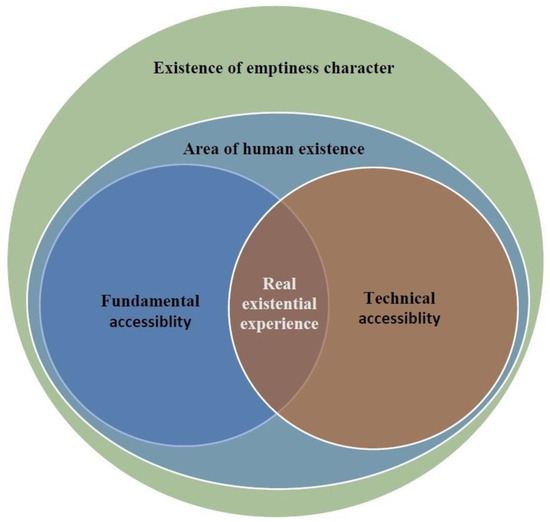

All this said, it is now visible why the authors are talking about the creation of a paradigm in the relationship of physical and fundamental accessibility (Figure 1). The paradigm of fundamental accessibility just being born basically serves the following purpose: humans as a creature with existential disabilities should see themselves and the communities created by them, and not last the technological civilisation that they created, as conditions allowing the development of Homo sapiens [41].

Figure 1.

The disability nature of human existence. Source: edited by the authors.

Fundamental accessibility in this interpretation framework is an outstandingly important idea of the cornucopia of intellectual discoveries. Furthermore, it can be panacea, an “antidote” for the forgetting of humankind, more and more evident nowadays [6], as it explicitly warns us about the importance of the necessity to keep our spirit fresh, i.e., it makes us realise the never-ending nature of the birth and mapping of obstacles. This activity has become by now, in the words of Feyerabend, the “toy” of humans acting like religious sects moving in ever-narrowing academic circles [9]. Technical accessibility thus, in the opinion of the authors, is a self-standing paradigm, as, e.g., the creation and operation of an induction loop born by technological and scientific specialisation go beyond the range of the everyday skills of common individuals. This would not be a problem in itself, if it remained a handy tool, i.e., if its use were naturally available for humans who require it and if people who do not need it took it self-evident that a lot of people do need it not because of speciality but due to the diversity immanent in human nature [42].

As it is clear, the authors have still not become adversaries of the tools offered by technological development, what they are doing here is to outline, along Marx’s and Heidegger’s paradigms of alienation, the—by far not complete—network of possible positive social and personal breakout points. The terminologies and practices of technical accessibility used in the world of travel reinforce the statements that travel itself, as a capitalist product of the barrier-dismantling technology, intends to create in the first place the possibilities of virtual experiences—not to be confused with the ever wider penetration of VR technologies, also in tourism—through the transformations of the environment for the sake of profit maximisation; however, in the majority of cases the experiences of those involved, and their relatives and assistants are the least enriched by getting to know the respective culture, it is more typical that travel becomes a survival tour. Of course, there are positive examples for really accessible travel experiences, which will be mentioned in the part of the paper demonstrating the empirical research. However, already in the discussion of the philosophical approach, it must be clarified that the latter are rather exceptions to the rule, created by the cohesive encounter of accidents and individual intentions.

Returning to the relationship between the paradigms that the paper is meant to demonstrate, it must be remarked that the relationships between both technical accessibility and fundamental accessibility, and between existential disability and the philosophy of symbiotic man reaches beyond inevitable rivalry and fight for dominance by Kuhn’s paradigms. The authors of this paper argue, both as thinkers and researchers, for the creative power of communication among paradigms.

Technical accessibility and fundamental accessibility, knowing the hermeneutical and empirical scrutinies, could never be separated from each other perfectly, just like neither of these two human activities are the creations of modern humans. Hegel says [28] that humans can reach the state of “improvement” into an intellectual being, but for this—add the authors—it is also necessary, among other things, that they re-possesses the ability of existential remembrance [7].

The limits of the volume of this paper, unfortunately, do not allow authors to give an in-depth discussion of the philosophical branches of existential remembrance, as self-limitation, the brief comparison to Bergson’s remembrance and intuition [18], can be done. The coupling of remembrance and forgetting in the case of Bergson demonstrates, among other things, what humankind as a self-creating being can rely on during its special walk of life, and what the experiences from past and present by the conscious “forgetting” of which humans can ease their everyday life are [18]. Starting from this, it seems to be justified to introduce the concept of existential remembrance, which also means the use of conscious and structured “memory vision”. In other words, humans are capable of the storage of “memory essences” filtered down from their own life experiences, and by elevating them into the present in certain situations they can re-actualise their experiential ranges. This way remembrance becomes (can become) a process-like ability of an empty nature, and thus can be used as a kind of “entrance gate” to fundamental accessibility. During our everyday lives, remembrance has been reduced to hardly more than a mechanic state, the travel contexts of which is demonstrated by the extreme volume of digital photographs and video recordings uploaded to cyberspace [43].

Bergson, with a vision of this, does argue for the organic and man-building nature of remembrance, and implements this in his essays on intuition as a legitimate method for getting to know existence and the world [32]. French thinker Deleuze acknowledges the viability of empirical, quasi-logical learning modes, but is also an advocate of the efficiency of intuitive learning; in fact, he says that this is not hierarchically subordinate to the research methodology structure mentioned above and is still considered as the ultimate structure. Deleuze, interestingly, uses as an example just the world of travel when he tries to demonstrate the difference between the two approaches. He argues that one can get to know a city by the photographs and paintings of it, or by the report of another man about it, but this is not a complete picture by far, and even less so it is a mental image that becomes and integral part of humanity, from which images the remembrance essences mentioned above are born. The (more) complete knowledge by Deleuze can be realised by actually arriving at the city and devoting as much time as one can to get to know it. It must be remarked that the “flock” of human hordes running across the destinations is just against the real acquisition of information and knowledge. Deleuze prescribes a detailed and thorough “field trip” for travellers so that the remembrance essences mentioned several times so far can get into their conscience.

It is hoped that this brief Bergsonian philosophical guided tour in the world of the acquisition of knowledge makes the reader feel that intuition is not an esoteric, unscientific mystery, on the one hand, and gives a contoured shape, on the other hand, to the plausible conditions in whose centre we find the paradigm of fundamental and technical accessibility, and will also make more comprehensible why these two ideas are inseparable from the general concept of existential disability [2,30]. Intuition in the view of the authors is thus a sort of development and usage of remembrance and abilities, which is not void of the high requirements of empirical examinations but at the same time goes beyond their rigid and often still positivist boundaries, i.e., gives space to “creative development” [18] that must always be characteristic of the human mind. It must be remembered that we humans are not finite creatures [16,44,45], ergo we, as existentially handicapped entities, must force ourselves to actually enlarge our knowledge.

Evoking Nietzsche’s world-view [46], it can also be said that the seemingly paradoxical image of the Overman (Übermensch) can be associated with the recognition of this infiniteness, as it can be also negatively paralleled to the self-deception that we are the “crowns of creation”. Nietzsche’s Zarathustra, returning to the main square of the town, sees that people are staring at a stretched rope where the rope walker is expected to appear sooner or later. This tightrope walking metaphor can also be interpreted as follows: humankind can get, balancing on a very fine line, from being an animal to becoming human, and then the Overman [47]. The concept of Overman in the authors’ interpretation means that one “possesses” the ability to draw the maps to all those abilities, and also to have the way of remembrance of these, which helps to orientate in the disability labyrinth also deriving from one’s infinite character. Paradoxically, the possible goal of the journey is not getting out from the labyrinth at all; the attention is drawn, instead, to the irreplaceability of recognition as a never-ending process and task.

The obstacle(s) before the individual and the groups made of individuals can also be interpreted as constituents and at the same time conditions of the existential labyrinth of being. Accordingly, technical accessibility can also be seen—provided that is still interpreted in the mainstream present way—as violating existence, i.e., the creator of an alienated, obsolete and spiritless technical world.

The attitude of technical accessibility may start to transform, by the inspiring nature of the human spirit, this anti-humane structure of existence, in which, e.g., technical accessibility measures implemented in the world of travel are re-evaluated as tools assisting the generation of experiences and memories [2].

The authors agree with Feyerabend [9] that the dogmatic approaches still applied in the mainstream of contemporary science continue to be obstacles blocking the implementation of generating emptiness-natured paradigms that have a holistic view, are open and communicating to each other.

This makes the authors search with their limited assets for the ways among the worlds of fundamental accessibility, technical accessibility and existential disability, and, applying the knowledge and tools of the science of travel, draw attention to the enormous responsibility that they believe we have in our everyday lives and not least during our travels that have become organic parts of these lives by now [48].

The thousands-of-years-old practical and theoretical toolbox of emptiness philosophy also underlines the usefulness of these efforts for individuals and communities as well [22,23].

It must be taken into consideration that fundamental accessibility and technical accessibility are entities without self-nature not only in the conceptual but also the practical sense. This means that neither of them can exist and can “function” without the other one. Furthermore, several other conditions and casual criteria are necessary and must temporarily exist, like for example for the design, construction and operation of a single elevator, that one does not even think about—just like taking a loaf of bread off the shelf of the shop does not appear to us an emptiness-centred action with technical accessibility character.

It should also be considered that humans use emptiness of the space to build residential buildings (accommodations), in which to live life relatively comfortably, protecting, among other things, their own fragile bodies [49,50]—in other words, it creates technical accessibility.

The two banally simple examples above demonstrate again how conventional and witless the lives of people living in the Western hemisphere have become [33]. They identify emptiness with nothing, which is a nihilist, anti-humane viewpoint whose origin is the lack of knowledge [14,51]. The same is true, in the view of the authors, for the correlations between the necessity and the implementation of technical accessibility.

The authors are convinced that an accommodation made accessible by very sophisticated technical solutions—which are very rare, unfortunately, as it will be indicated in detail in the part of the paper demonstrating the findings of the empirical research—is not enough in itself to generate either attraction [36] or the source of experience-essence in the philosophical and everyday meaning of the word. They are also aware of the fact that the application of the fundamental accessibility paradigm, recommended for the solution of this dilemma, only sounds to have conceptual significance at first hearing; however, if the medial approach to the emptiness character is implemented as a link between fundamental and technical accessibility, it is clear how these two basic constituents of existence, inseparable of humanity, turn from a conceptual potential into a topical one.

This is why the authors are aware of the fact that the creation of the new, anthropology-oriented philosophy paradigm of man, i.e., the mapping and recognition of the character of humans as naturally barrier-dismantling and existentially disabled beings, is inseparable from fundamental accessibility.

The lack of space does not allow the detailed discussion of this issue; what must be briefly remarked here is that the intelligent state of humanity is actually an artificial state [52] that can be described as the result of the necessity for technical accessibility originating from the needs of survival.

As Jaspers [44] remarked, humans can be seen as creatures disabled compared to animals, taking into consideration their physical weaknesses and limitations. Humans, however, have become able to recognise their own weaknesses and in order to compensate these, to find extremely diverse, and originally not alien from nature, ways to utilise the potentials of individual and community fulfilment [14,46,53].

This intellectual capacity and maturity for technical accessibility are manifested now in most cases in the—mostly capital-oriented—implementation of technical accessibility investments, which may be evaluated as one of the palpable proofs of existential disability.

Humans, as creatures depending (among other things) on the existence of fundamental accessibility, i.e., an originally disabled creature, are able to re-activate their forgotten intellectual capacities and provide an intellectual toolbox for the implementation of technical accessibility, then coming from this continuous “insemination”, to become a real traveller again in the infinite and multi-dimensional spaces of being. Humans can “extract” from here, from among the billions of experiences necessary for existential remembrance.

A Special Theoretical Approach That Ushers Us to Clearly Methodological Statements

The authors of the paper participated, as researchers and experts, in the Erasmus+ supported project called PeerAct (www.http://peeract.eu/, accessed on 14 January 2022). This is a one-off, extraordinary research where people with disabilities were directly interviewed with a questionnaire. A disability is considered as an existential and travel condition. Unlike most other research, this was designed to get direct information from those involved and the people assisting them. It was not a large-scale sample that the authors intended to use; their goal was to make an analysis that focuses on the relation of people with disabilities to the disabilities of others and of their own. Most of the assisting persons are also disabled, making the topic and the size of the sample to be reached very special (and limited): assistants of those who need assistance. The project had been designed, implemented and got accepted just for this purpose: the demonstration of a very narrow segment. This is where the empirical part of the paper is connected to philosophy: the dimension of fundamental and technical accessibility is discussed not only with regards to travel but also to general human actions. Humans in existence are seen as implicit and explicit travellers and this manifestation of travelling can be seen through the empirical part of the paper; also, the goal was to demonstrate travel in existence as a human activity both explicitly and implicitly, and to highlight the possibilities offered by human cooperative ability in this internal and external activity. So the objective was not an extended survey (like it was not the goal of the original call for tender for the empirical research, either) but the demonstration of the societal use of the survey and the sampling of a special segment of the target group, and, on this ground, the limited but we think the correct empirical foundation of our philosophical, paradigm-shifting and -creating intentions.

This is about the travel habits and especially motivations of a narrow segment. The aim was the survey of practice and not the national level monitoring of travel habits. The authors did not want results or replies that were identifiable, and the sample was relatively small (in the call for tender, the societal use was the focus, and not the quantity of respondents or the volume of the survey) which did not allow a detailed demographical analysis. Furthermore, the call for tenders explicitly stated that sampling had to fully obey the regulations specified in GDPR. Consequently, it is not possible to expand this dimension of the research, although we think it will be useful in the future to conduct a large-sample sociological survey for the detailed introduction of this special segment, especially as regards their travel habits. It is about speciality in the sense that the specific travel offer is actually seen as segregation by the target group, and this is exactly what they fight against. This also proves that narrow technical-minded accessibility does not serve the interests of those concerned and their companions if it is not in line with the spirit of fundamental accessibility which in itself is directly against segregation.

2.2. Preliminaries and Foci of the International Empirical Research

This special survey method also justifies the joint demonstration of the three-dimensional philosophical approach mentioned above together with the findings of the special empirical research with its one-off approach and methodology, mutually reinforcing each other. An important mission of the project was to build the methodology and training material of peer assistance (which must be given absolute priority in the technical accessibility minded development of tourism services as well), to be worked out as a deliverable project, on real demands from information provided by the stakeholders, so an important part of the project was a questionnaire survey conducted among people with disabilities. The survey was meant to collect information allowing researchers to draw conclusions in three main areas:

- Travel habits, consumption habits of people with disabilities during their journeys;

- Opinion of people with disabilities about the situation of fundamental accessibility in tourism;

- The impact of touristic activity on the quality of life of subjective feeling of happiness of the target group, and implicitly the role of these in the totality of experience gaining, living and remembrance.

The research was extended, in addition to Hungary, to the questioning and direct inclusion of travellers with disabilities from four other countries with significant positions in European tourism (Germany, Croatia, Spain and Italy), making a contribution to getting to know the coherent existence of technical and fundamental accessibility, and the travel preferences and problems of this special segment, more sensitive than the average. It was also a goal to better know the potential deviations from the travel habits of people without disabilities and to detect ways to solve the problems that this special target group encounters during their travels.

With the inclusion of the stakeholders, in a project meeting, the managers, coordinators and professional leaders of the project, and the representatives of the governing body jointly defined the indicators to be used in the research, with contribution from assistant experts very well knowing the social layer of those living with disabilities.

We are not in an easy situation when trying to define the concept of disability, as it has many different forms. Not only people with locomotory problems, or with sight and hearing impairment [54], people with intellectual disabilities can be listed here but so can those who suffer from diseases with long-term impacts on their quality of life, e.g., from allergies [3,39]. According to WHO estimates, every 6th dweller of the planet suffers from some kind of disability and this number is continuously increasing [55]. The Convention of the Right of Persons with Disabilities, approved by the United Nations Organisation in 2006 and also integrated into the Hungarian legal system, obliges the signatory countries to provide access for people with disabilities to sport, holiday and tourism resorts and services [Act No. XCII of 2007 in Hungary]. Any of us can become functionally disabled at any time—which, unlike the existential disability briefly discussed in the philosophy section of the paper, in which we are all equal, here means the mainstream, accepted disability categories [7]; just think of the progress of our age (but an accident can also make anyone permanently disabled at any time). A special phenomenon underlining the importance of the issue from this respect is the aging of societies. Special needs in old age can emerge in practically anyone, and several other situations in life can lead to the emergence of special demands, like recovery after an accident or the special needs of families with small children [56].

Tourism, having become a general social phenomenon, is now an important factor in affecting the quality of life [57]. It seems to be widely accepted by now, luckily, that alleviating the travels of people with disabilities, to provide the physical conditions for this is not only an ethical, moral and also legal obligation—these conditions of a non-technical character imply the need for the adoption of the view of fundamental accessibility, but tourism of the people with disabilities is also an important economic issue [58]. For the time being, it is a largely underutilised market segment in tourism, although positive counter-examples can also be seen in recent years [59]. This underutilised market segment, however, should not be seen as a homogeneous group, as members of this group have diverse demands against the services, depending on the type and severity of their disabilities. There are obstacles relevant for all travellers and ones that are insurmountable problems for narrower segments, only [2]. Different destinations are on different levels of the implementation of fundamental accessibility: some have worked out special offers for people with disabilities; others even feature the availability of accessible environment as an added value—recognising the fundamental significance of accessibility, in addition to the market opportunities. It must be remarked that the research findings underline the hypotheses that an accessibility-centred attitude is very rare in the structural supply of destinations. What is more, there are still destinations where this issue is not given any attention at all.

The dominant European countries of international tourism, however, do place a significant emphasis on this problem; the efforts of, e.g., Spain [60], Italy [61] and the United Kingdom [62] in technical accessibility in tourism are noteworthy. The personal experience of the authors is that the situation in this respect is considerably better in Germany than in Hungary: in Germany, in all fields of life (including public transportation, a sector of special significance for tourism), correct solutions can be seen for technical accessibility and thereby the provision of equal access. The implementation of complex tourism services designed and operated according to the principle of fundamental accessibility is not equal to physical accessibility; a real and not special (existential) experience given by the destination is much more than that—it is the implementation of the following principles also in tourism, without aiming at realisation of the principles of independence, equality and human dignity. Experiencing the spirit of the locality is just as important for a person living with a disability as it is for anyone else. It is a generally accepted fact that the experience of travel and holidays strengthens the subjective feeling of happiness [36,63]. This statement is especially true for those living with disabilities. Several empirical studies have proved in Hungary that people with disabilities encounter serious difficulties during travel; their disability is a handicap in the implementation of their travels. This makes many of them choose the option with the constraint of “non-travel” [2,64,65]. Approximately half of the persons with locomotory disabilities are blocked by their handicap in participating in some touristic activity, whereas the same proportion for those with sight impairment is 75% [4]. Serving guests with disabilities requires a high level of empathy and attention from the service providers and other actors in the tourism industry.

3. Research Methodology of the Empirical Research

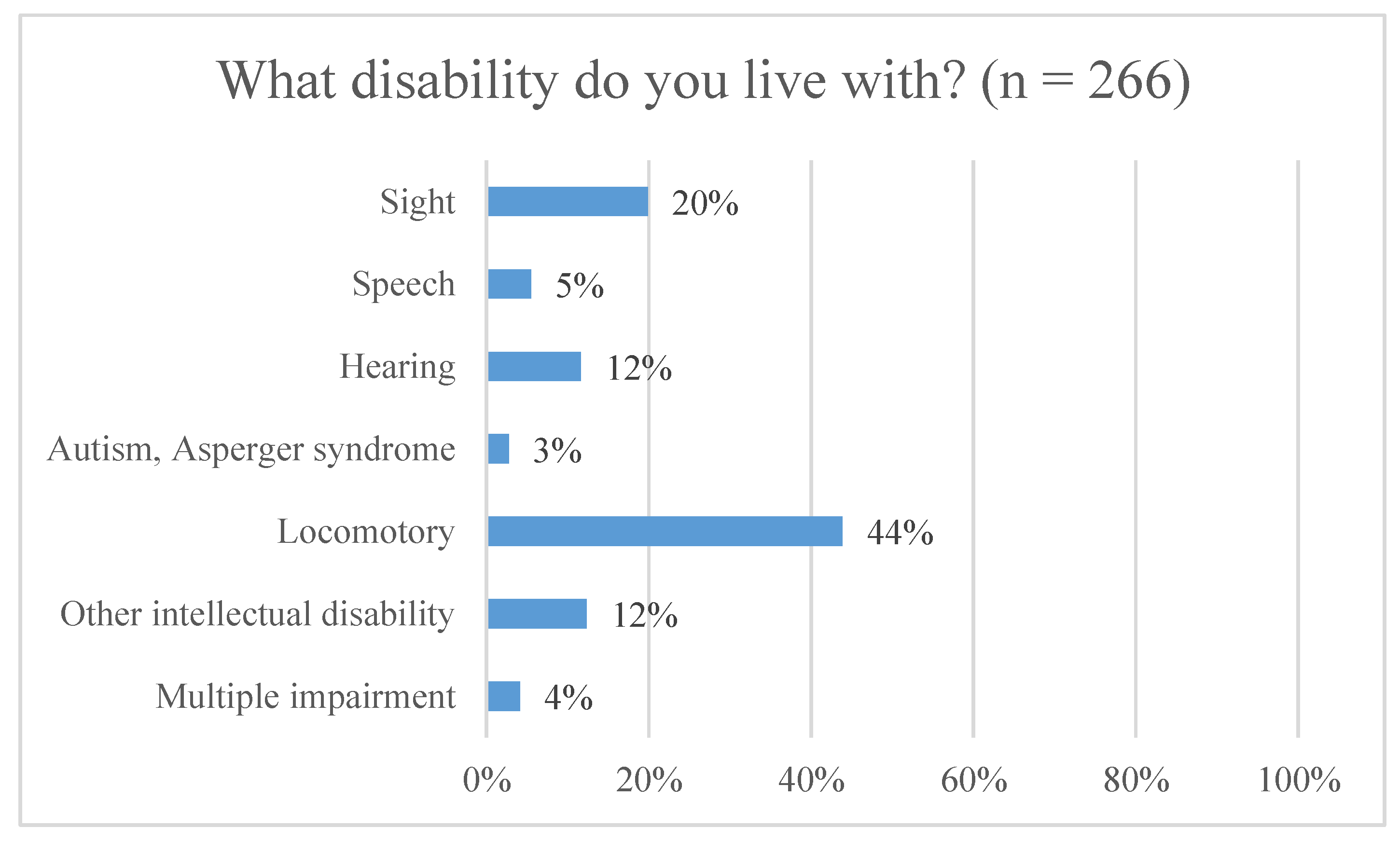

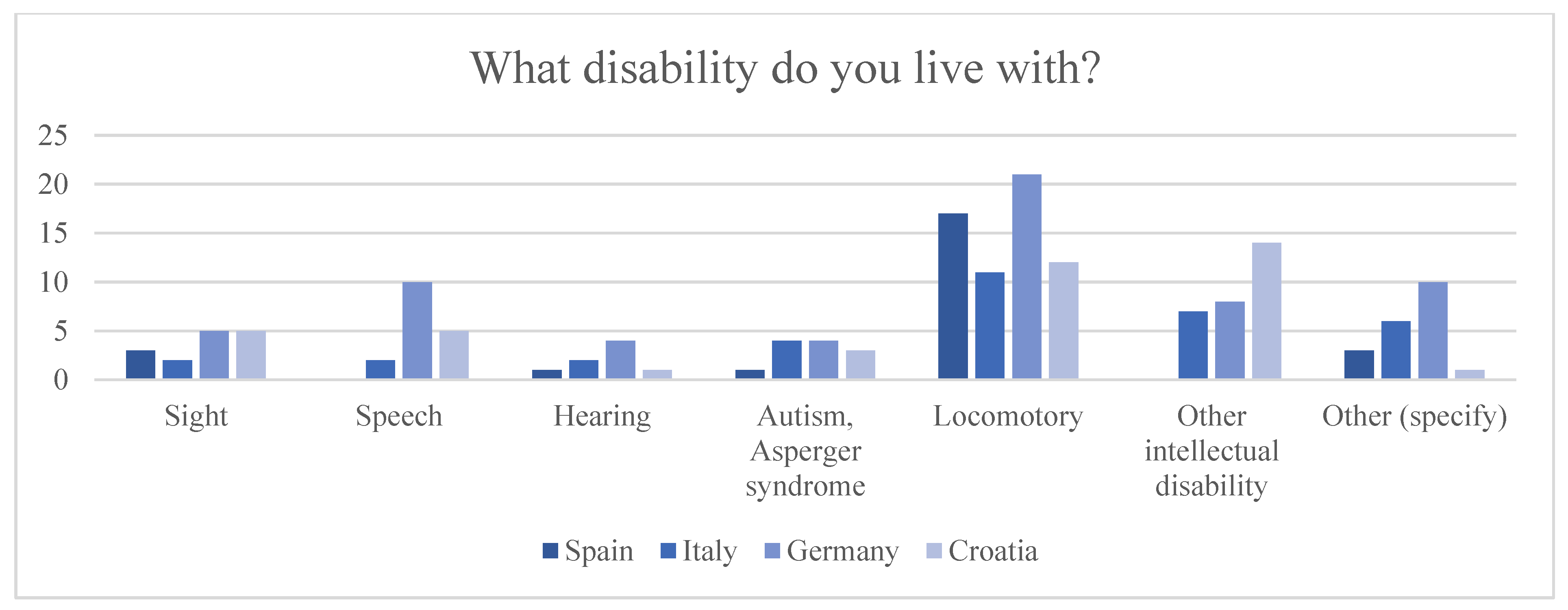

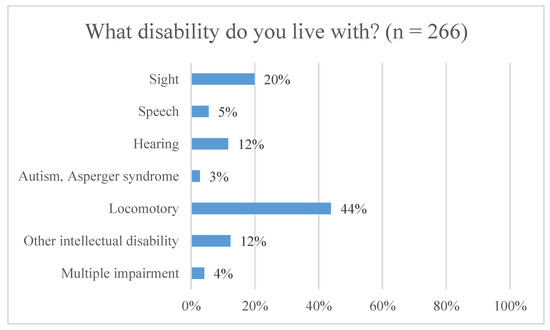

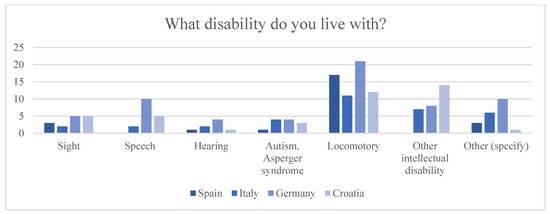

The finalisation of the research questionnaire was done with the inclusion of all research partners, and the survey itself was launched in the spring of 2019 by the partners. The work was finished by September of the same year. As the research element of the project was the responsibility of the Hungarian project partner, the idea was to conduct the questioning of a larger sample in Hungary (200 respondents) that would be supplemented by a survey of 30 respondents from each respective country. The Hungarian sample of the survey was 262 persons in the end, to whose findings were the findings of the surveys of relatively small samples from the project partner countries compared. It was an important aspect to include respondents representing all sorts of disabilities in the research. The search for credible respondents was successfully done, as revealed by Figure 2 and Figure 3. It must be remarked that the direct access of people with disabilities and their inclusion is an extremely problematic task, irrespective of their socio-cultural and geographical situation [66]. This statement was reinforced by the respective international survey as well. This should be taken into consideration when judging the relatively small sizes of the samples.

Figure 2.

Breakdown of Hungarian respondents by their disabilities. Source: edited by the authors, using the findings of the questionnaire survey.

Figure 3.

Breakdown of respondents by their disabilities in the other project countries Source: edited by the authors, using the findings of the questionnaire survey.

The composition of the samples by age group was another important aspect during the survey, to ensure the inclusion of all generations (Table 1). The detailed research report of the project reveals that the sample of respondents involved was diverse by all demographic indices like marital status, highest educational attainment, living conditions and type of economic activity, so the sample was a realistic reflection of the total of the target group, i.e., people with disabilities.

Table 1.

Age compositions of the research samples.

Just over two-thirds of Hungarian respondents (68.7%) were born with their disabilities, a little less than one-third of them (31.3%) were not—a significant deviation from this could only be seen in Spain where those respondents were the great majority who were not born with disabilities but were injured during their lives.

3.1. Research Findings: Travel Habits of People with Disabilities

Almost all members of the target group, i.e., people with disabilities reported some obstacle(s) making their travels more problematic. The difficulties that people with disabilities face most often are as follows (in order of importance): difficulties during travel, problems of using catering facilities, problems of using accommodations, difficulties when sporting, difficulties in visiting attractions and communication difficulties. It was only 4% of respondents who said they had never experienced any difficulties in their lives. The international comparison reveals that German respondents reported the largest number of hardships—as it is evidently not Germany where accessibility is the least developed, this might be explained by the fact they are more aware of their rights and have higher expectations; in other words, they feel more realistically the difference between technical accessibility and fundamental accessibility, and the lack of emergence.

More than two-thirds of the respondents use (or would use) some kind of technical aid or human assistance during their tourism-motivated travels. The majority relies on assisting persons. A great proportion of Hungarian respondents use a wheelchair, followed by those who use walking sticks during their everyday lives and when travelling, then by those using a hearing aid or mobile phone (applications that assist orientation and communication). Finally, some sporadic answers also mentioned guide dogs, artificial limbs, special medical shoes and spectacles. It is an interesting national and socio-cultural difference that Croatian and Hungarian respondents did not mention assisting persons, whereas this category was the most frequently mentioned one in the other three countries.

The next two questions were asked to find out whether people with disabilities had travelled abroad in 2018 and, if so, how many times. Approximately half of them said yes. The only exceptions were the Spanish respondents who had dominantly been on domestic holidays only. Those who answered yes to the previous question were also asked how many times they had travelled abroad in 2018. The results were as follows: of all those who had been abroad in 2018, the majority travelled only once or twice, and only a negligible proportion three or more times. This shows quite a large similarity to the travel habits of people without disabilities [63].

Next, the respondents had to answer if they had travelled abroad in the last five years and if so, how many times. Two-thirds of the Spanish and one-third of the Croatian respondents had not travelled abroad in the period in question, while in the other three countries, the proportion of non-travellers was only about one-third, and the majority had been once, twice or even more often on holidays abroad.

The next question was asked to see if respondents had travelled in their own countries for tourism purposes in 2018. The proportions of participants in domestic travels ranged from 70 to 90% in the project partner countries, with the exception of Spanish respondents, of whom hardly more than half had been on domestic holidays in the year before the survey.

To sum it up, it can be seen that people with disabilities are integrated into domestic and international tourism to the same extent as their fellows living without disabilities; no major differences can be seen between their travel frequencies.

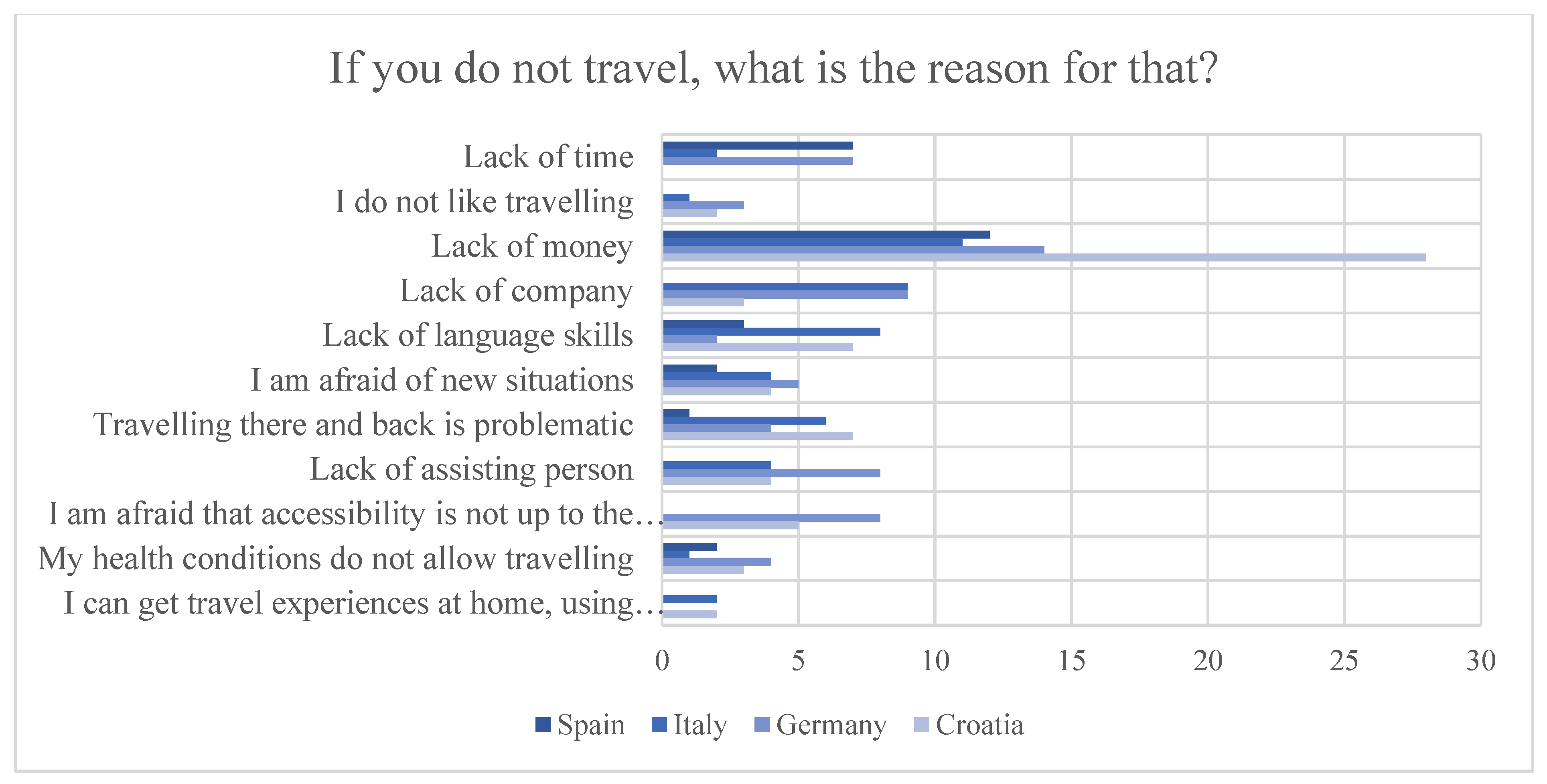

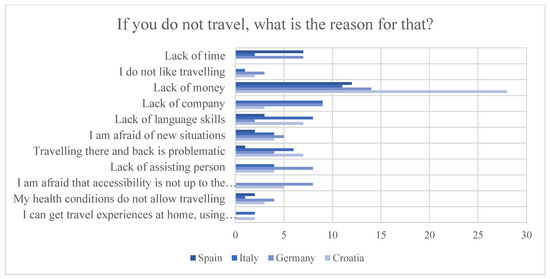

When thinking about the fulfilment of accessible tourism, which in the interpretation of the authors has a complex and holistic character, i.e., it must carry the complementary marks of technical accessibility and fundamental accessibility, we must know what holds back those who simply do not dare to travel. The nature of this attitude of heterogeneous “composition” was also sought by the questionnaire. The main reason in the circle of the Hungarian respondents was evidently the lack of money (25%), followed by the lack of an assisting person (15.7%) and the lack of company (10.2%). Furthermore, respondents were afraid of not getting the accessibility that they had been promised and/or they required during their travels (9.7%), and another dominant factor was the lack of language skills and the fact that the travel to and back from the destination was considered as problematic (9.3% for both). Some of the respondents are afraid of new situations (7.4%), and some decide on staying home for lack of time (6%), while for some it is the health conditions that do not allow travel (4.2%). Some justified their non-travelling by the fact that it is now possible to get travel experiences in their homes, using the internet and technology (2.3%), and some referred to travel difficulties (0.9%). Lack of money was an even stronger argument from the Croatian respondents (over 80%), but in all countries, this was the number one reason (Figure 4).

Figure 4.

Reasons for not travelling. Source: edited by the authors, using the findings of the questionnaire survey. (Unfinished sentences in their entirety are as follows: I am afraid that accessibility is not up to the promises and/or my needs; I can get travel experiences at home, using internet and technology.)

The next question was asked to find out whom the responding people with disabilities travelled with. The overwhelming majority said it was the family they travelled with, far fewer respondents travel with their spouses, or with friends and relatives. The latter group of the Italian respondents was larger than those travelling with the family.

It was also asked from what resources tourists finance the expenses of their travels. It is an important finding that half of the respondents were able to cover costs from their own incomes, 20–40% of them are assisted financially by their families or receive some support (e.g., from non-governmental organisations). The latter response was especially frequent in Croatia, but the survey did not explore the reasons for this. Presumably, as a now implicitly palpable “after-effect” of the Yugoslav war, the presence and assistance of the NGOs more organically integrated into the operation of the society can be found in the background [67].

One of the most fundamental issues of professional discourses has for years been what programmes people with disabilities like participating in when travelling. The research found that less than 20% of respondents prefer programmes specifically designed for people with disabilities. There are more who like integrated programmes, but the majority has a definite preference: they want to participate in programmes that are not tailor-made for the disabled. In the case of Hungarian and Italian respondents, their proportion exceeded two-thirds.

These facts further reinforce the statement of the authors that is impossible to obtain real and unlimited existential experiences without the recognition of the intellectual paradigm of fundamental accessibility and its implementation in practice, which is the central objective of this study. Even though not in this context, this is also acknowledged by the recommendations of UNWTO, e.g., the years 2014 and 2016 were dedicated by UNWTO to those in need of assistance [68].

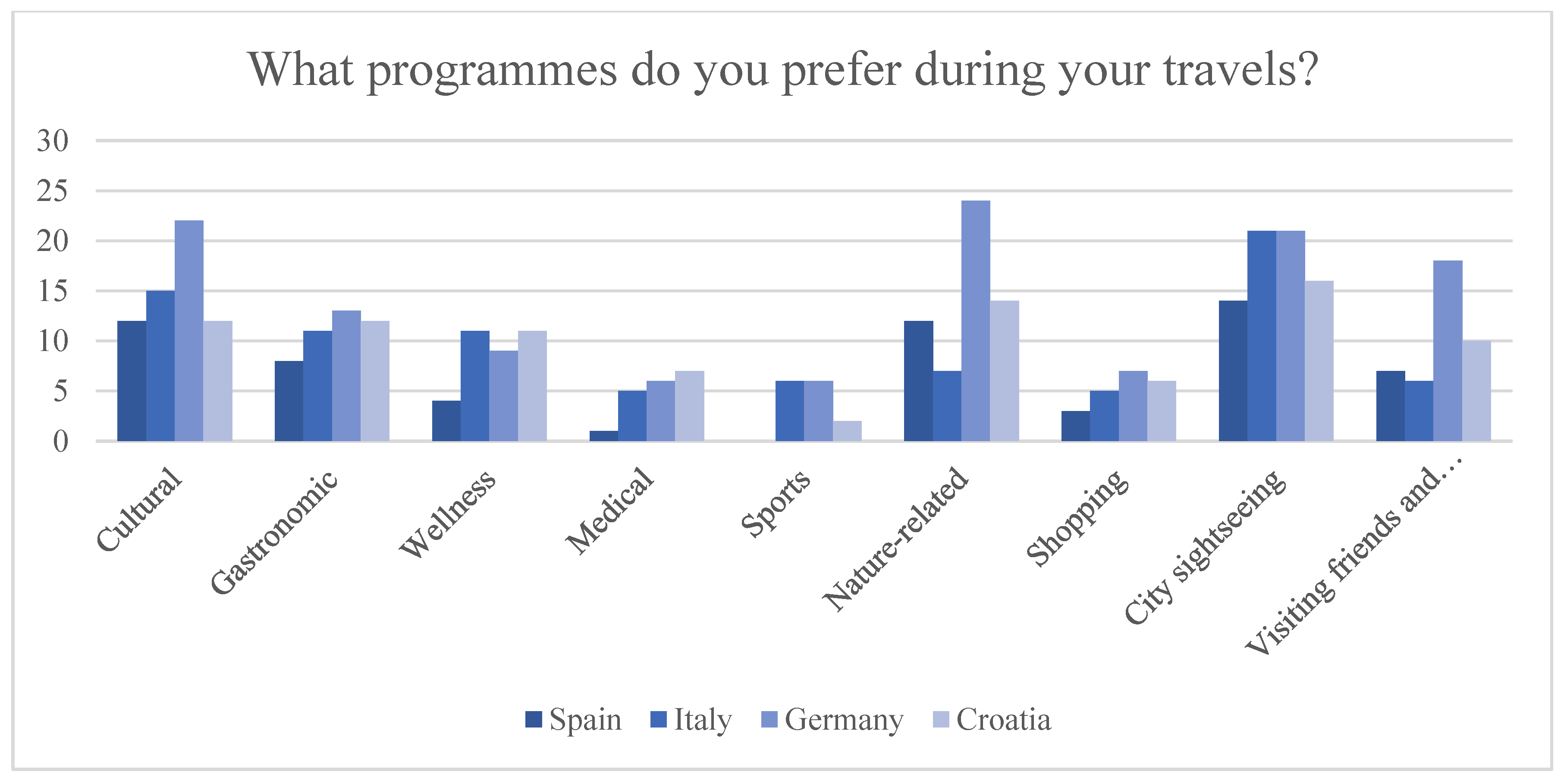

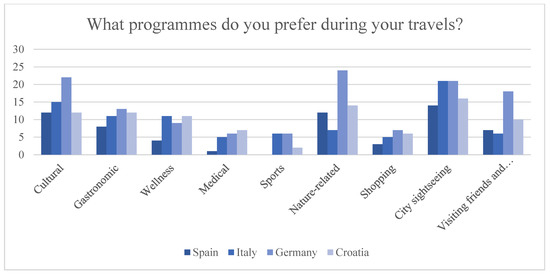

Approaching from the side of popular tourism products, the survey also looked at what programmes people with disabilities liked participating in during their travels. Multiple options were possible in the replies. The most favoured programme by Hungarian respondents was cultural tourism (60.2%), followed by nature-based (55.6%) programmes and city sightseeings (50.4%), but frequently mentioned options also included wellness (43.6%), gastronomy programmes (40.6%) and visiting friends and relatives (23.3%). Shopping and programmes that require physical activity were also mentioned (13.5% both). The replies from the other four countries were quite similar to these (Figure 5).

Figure 5.

Programmes preferred by respondents when travelling. Source: edited by the authors.

As a summary of these, we can say that there is no sharp difference between the travel habits of healthy (though, from the already mentioned philosophical point of view, existentially disabled) people and persons with (functional) disabilities. They are driven by the same motivations to participate with the same frequency in opportunities offered by tourism, they do not require unique “disabled” programmes and supply, and they would like the have equal access to the exciting attractions and services (which is also underlined by Ernszt et al. [69]).

3.1.1. Judgement of the Situation of Accessible Tourism by Those Concerned

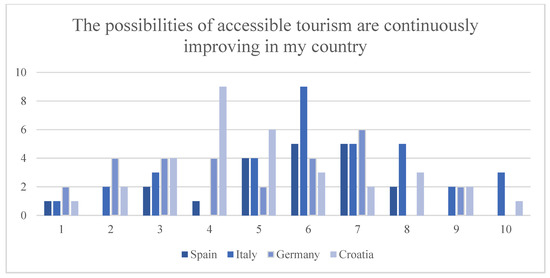

In the framework of an attitude survey, we wanted to find out how members of the target group assessed the situation of accessible tourism. In the survey, respondents were asked to express, on a Likert scale from 1 to 10, the extent of their agreement concerning a total of 11 statements (1: they totally disagree with the statement; 10: they fully agree with that).

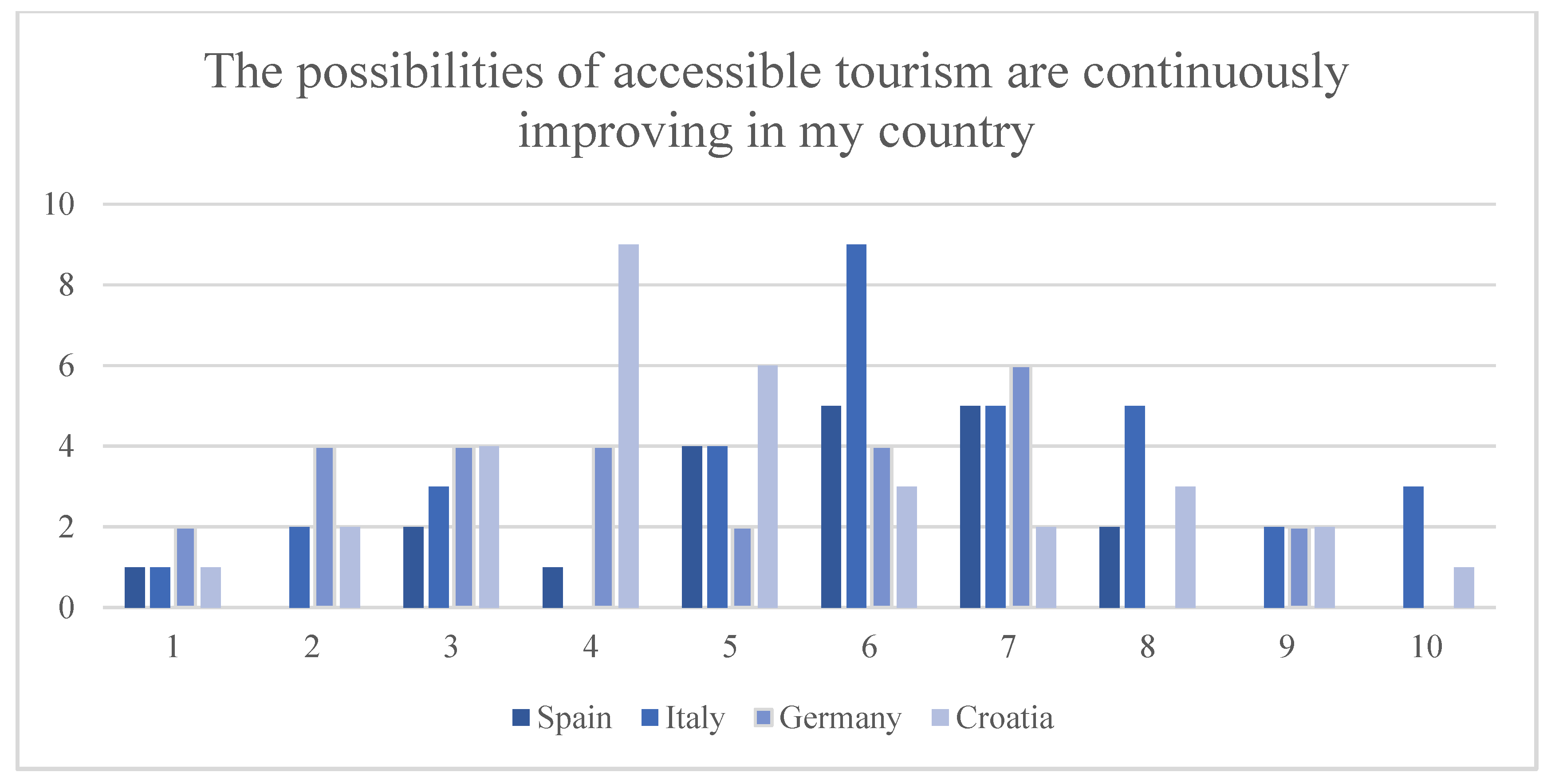

The first statement was about whether respondents saw an improvement in the possibilities of accessible tourism in their countries. The breakdown of replies, not surprisingly, was rather diverse; there is no full consensus on this issue. The most often marked numbers by Hungarian respondents were 5 and 6, i.e., approximately one-third of respondents did not want to express a clear-cut opinion about this issue. The breakdown of other answers was similar to the findings from the other participating countries. It cannot be said either that respondents see a continuous improvement in the conditions of accessible tourism or that tourism service providers are more and more prepared and open (fully adopting the “spirit of fundamental accessibility”) to the reception of guests living with disabilities (Figure 6).

Figure 6.

Agreement with the statement “The possibilities of accessible tourism are continuously improving in my country”. Source: edited by the authors, using the findings of the questionnaire survey.

Another important issue is how much society accepts the existence of accessible tourism or how much it is indifferent towards the travel needs of people with disabilities. For this purpose the following question was designed: “The society in my country is more and more tolerant and open to the problems of people with disabilities”. It was expected that, due to the efforts of non-governmental organisations and/or policy decisions of the last decades and to the impacts of these in practice, a positive result would be seen. Unfortunately, the findings did not support this hypothesis. Of all replies, 70–80% was in the range from 4 to 7 (which means slight disagreement of slight agreement). The proportion of those who strongly agreed with this statement (marking 8, 9 or 10 on the Likert scale) was small, on the one hand, and just as many people rejected this statement, on the other hand (marking 1, 2 or 3 on the scale).

With a view to the fact that in each respective country the largest segment of the respondents concerned was people with locomotory disorders, there were two questions specifically designed to detect their special problems. The first statement was that more people with disabilities would travel if trains and coaches were more accessible by wheelchairs in the countries in question. The majority of respondents agreed with this statement; more than 50% of replies marked the upper part of the scale (8–10). Responses expressing disagreement were a minority on the lower part of the scale. This also demonstrates the empathy of people with no locomotory disorders towards their fellows who have these problems.

The next statement was as follows: if there were tourism paths in park forests, at least in the vicinity of cities, more people with locomotory disabilities would make excursions. Similarly to the previous statement, the level of agreement with this statement was significant, with more than 50% of respondents indicating the three highest values (8–10). Responses with lower values were sporadic and none of them were significant.

For those in need of technical accessibility and fundamental accessibility, access to adequate information concerning these is important, as it greatly eases the preliminary design of a travel programme [2,3,70]. In order to get information about it, respondents were asked to react to the statement saying that if there was a reliable internet collection of tourist paths manageable by wheelchair, constantly upgraded and accessible, more people would choose hiking in nature. Answers are clear-cut; more than half of the respondents chose the three highest values. Four-fifths of the respondents think that more people would choose travels of this kind if the information about them were available.

It has already been demonstrated by replies to previous questions that the travel habits of people with and without disabilities do not differ much, and neither do their motivations. Where a difference can be seen is not the intention but the possibility and quality of access. A research question of the survey was designed to justify this: a question was asked about activities that seem to be quite far from the stereotypes about people with disabilities. The statement saying that extreme sports and activities would attract people with disabilities if they were given adequate technical safety and assistance was evaluated by respondents as follows: one-fifth of Hungarian respondents fully agreed with this statement, and more than two-thirds of those filling out the questionnaires agreed to some extent. The share of those who disagreed was approximately 20%, whereas the convenient neutral values were 8.8%. The proportions of agreements are similarly large in the other countries as well, which is another proof of the fact that the co-existence of adequately implemented technical accessibility and fundamental accessibility would lead to a demand by people with disabilities for all services offered by the world of travel.

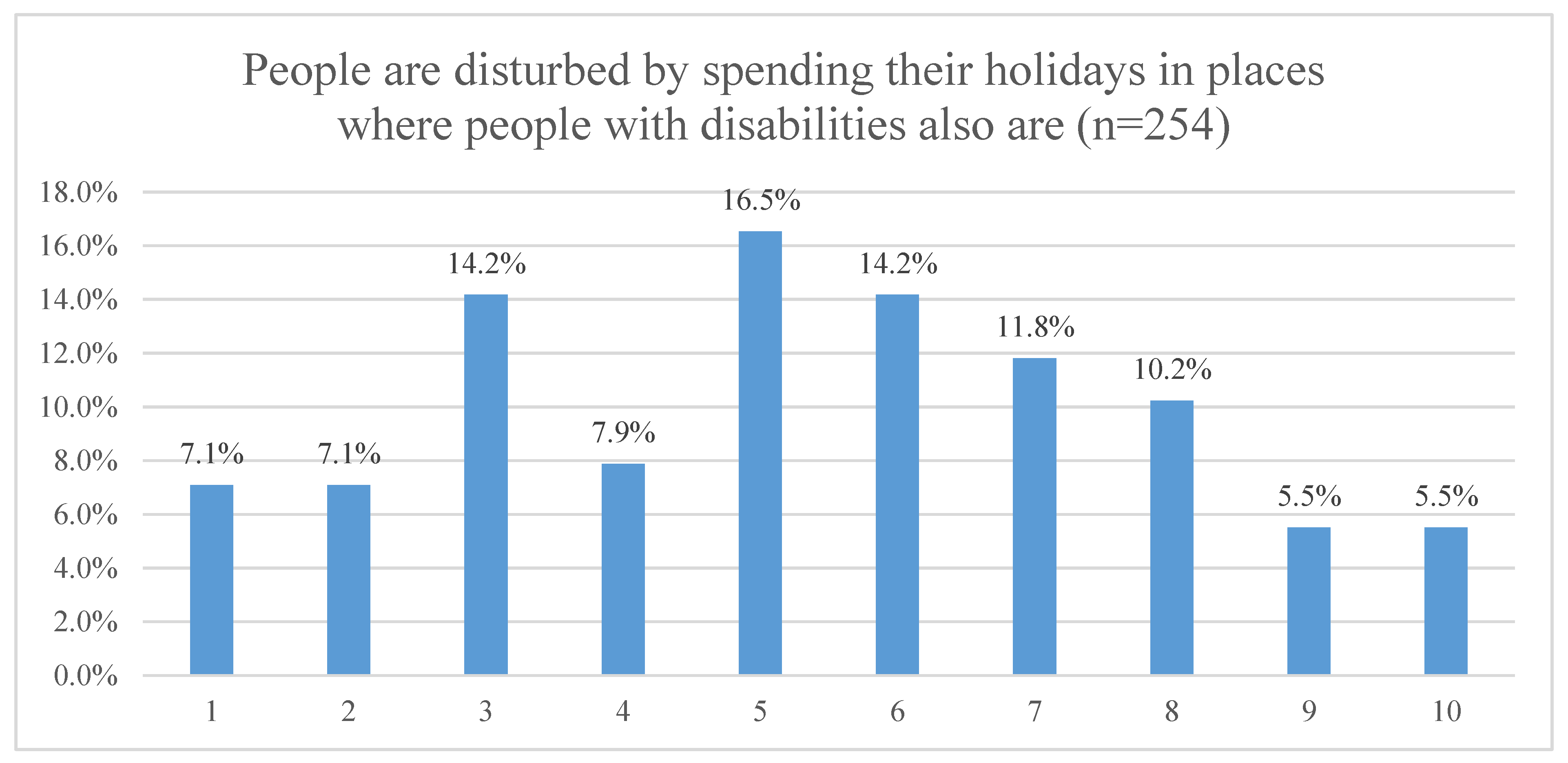

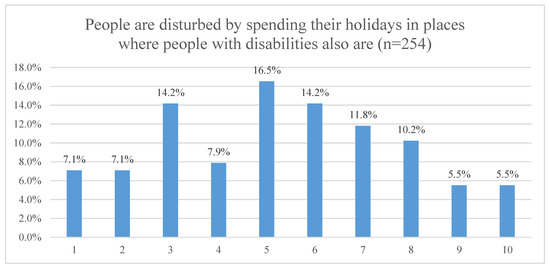

The next statement, as opposed to the previous ones, did not enjoy the full consent of the respondents, and replies were quite heterogeneous. The statement was as follows: people are disturbed by spending their holidays in places where people with disabilities are also present. The most typical answer by Hungarian respondents was the convenient mean value, with 16.5%; most respondents gave values around the average. Of all respondents, 36.3% more disagreed with this statement than agreed, whereas 47.2% of them more agreed. It seems that then that people with disabilities are more likely to think that they disturb “healthy” people. The overall situation is somewhat better in the other four countries, as shown by the reactions (Figure 7).

Figure 7.

Breakdown of reactions to the statement “People are disturbed by spending their holidays in places where people with disabilities also are”. Source: edited by the authors, using the findings of the questionnaire survey.

3.1.2. The Impact of Travel on Quality of Life and Subjective Feeling of Happiness of Respondents

The examination of the correlation between tourism and the quality of life is an important issue of tourism research in several countries [71]. However, not enough attention has been paid so far to this issue in the case of people with disabilities, although it is clear that for them it is especially important that tourism, compensating for other problems, should contribute to getting full experiences on their own, the improvement of the quality of life and the birth of the subjective feeling of happiness and of course, to remembrance mentioned several times so far. This is also how the overwhelming majority of respondents think: the proportions of agreement were very high. The first statement was as follows: “Tourism is an important part of my life”. With the exception of the Spanish respondents, in each country the scale values of 8, 9 or 10 were indicated by almost 50% of those who replied, showing evident agreement. The number of scale values of ‘10′ was strikingly high by German respondents (12).

A similarly high acceptance could be seen concerning the statement “Tourism significantly promotes my wellbeing”. In this question, it was the Hungarian respondents who showed an outstandingly high level of agreement (acceptance by 66%).

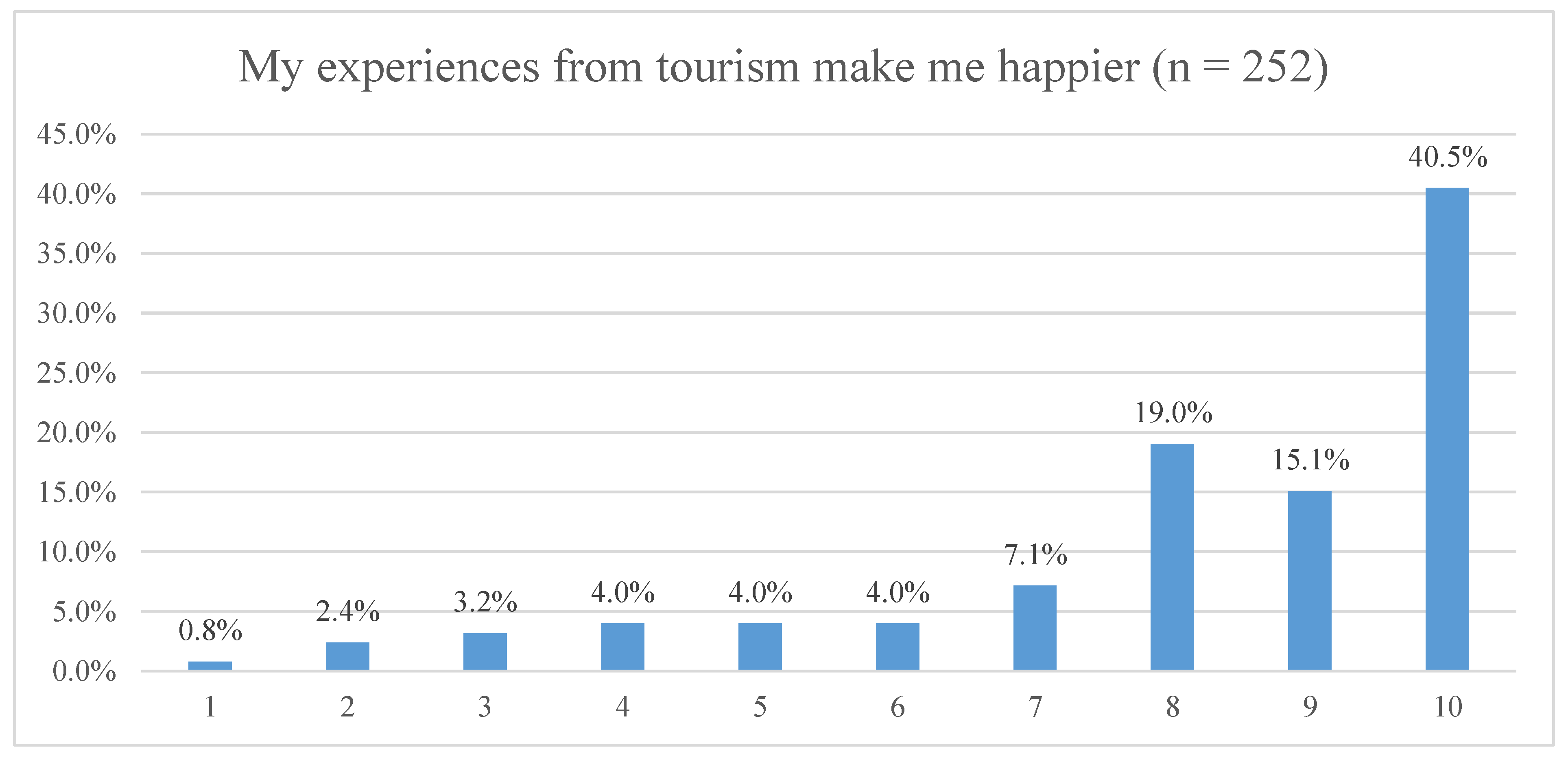

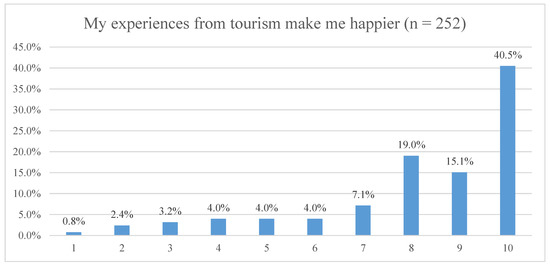

The strongest agreement was seen concerning the statement “My experiences from tourism make me happier”. With the exception of Spanish respondents (who were less involved in touristic activities than respondents from other countries), half of all respondents strongly agreed with this, marking values 9 and 10 (Figure 8). It was Hungarian respondents who showed the strongest agreement, with three-quarters of them voting for this (value 10 indicated by 40.5%, 9 by 15.1% and 8 by 19%).

Figure 8.

Breakdown of reactions to the statement “My experiences from tourism make me happier”. Source: edited by the authors, using the findings of the questionnaire survey.

Therefore, the following statement seems to be truly well-founded: happiness—however plausible existential experience and concept it is—connects, as part of Michalkó’s paradigm of travel [36], to the efforts of fundamental accessibility in the complex interpretation, as it is both one dimension and the fruit of an independent and fully experienced life.

As regards the statement that tourism improves people’s relationship to their fellows—contributing thereby, among other things, to the penetration of the spirit of fundamental accessibility—the reactions of respondents were as follows: almost a third of them fully agreed, and the proportion of all who agreed (indicating value 6 or higher) is over 80%.

Another important issue concerning this topic is whether people with disabilities who filled out the questionnaire had ever experienced any discrimination because of their (functional) disabilities during their travels. Unfortunately, the number of those returning with bad experiences from their travels is still rather high, their proportion exceeding 40% among Hungarian and German respondents and being around 30% in the other countries. Germans were especially dissatisfied with the accessibility of transport tools of public transportation in their own country, whereas several Hungarian respondents indicated the lack of accessible public toilets in Hungary. This is a general problem of tourism, irrespective of whether one has a functional disability or not. Furthermore, conclusions can also be drawn from this concerning the attitude of the given community concerning accessibility. This was not an issue in the other three countries.

In the next question, respondents were asked to answer, on the basis of their own experiences, which country could serve as an example to be followed in the field of tourism of people with disabilities. Multiple choices were possible at this question. A significant part of the respondents were not able or willing to answer this question. Responses were rather diverse, with no country being the evident best example. The countries mentioned most frequently included Germany, Austria, Scandinavian countries, Spain and England. Examples to be followed frequently mentioned in Spain were rounded pavement edges, ramps, and the good accessibility of touristic attractions, while the accessibility of community transportation in Germany was praised. Interestingly, German respondents were quite dissatisfied with this in their own country.

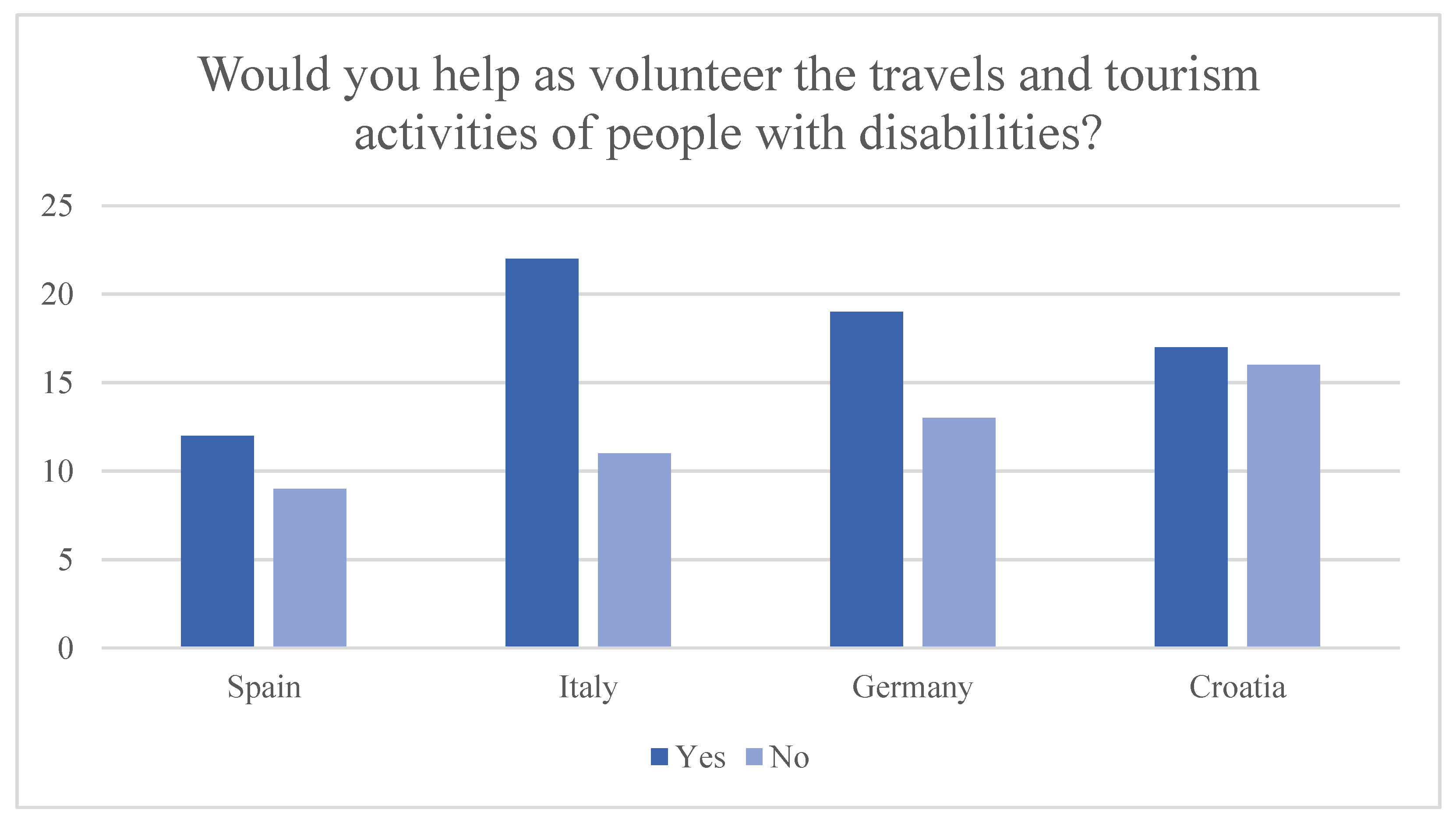

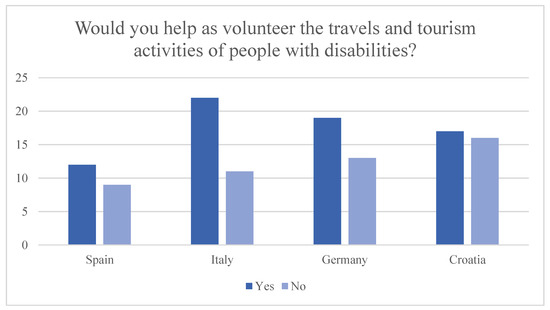

The last question was whether respondents were willing as volunteers to assist the travels and touristic activities of people with disabilities. The question is also important for the goals of the PeerAct project, as the project is meant to offer research methodology and training material for peer-to-peer assistance (Figure 9).

Figure 9.

Willingness of respondents to assist as volunteers the travels and tourism activities of people with disabilities Source: edited by the authors, using the findings of the questionnaire survey.

It is welcome that the findings were even more positive than had been expected: respondents in each country said yes in more than 50% of the cases, and the share of those happy to help even reached two-thirds in Hungary and Italy. It is a clear fact then that there is real openness by people living with disabilities towards peer-to-peer assistance in making travels accessible for their fellows.

4. Conclusions

The paper was made with a double objective: one was the exploration of the differences and similarities between fundamental and technical accessibility, the other aim was to launch the foundation and definition of these two different human actions, along with the differences and synergies that may even be called paradoxical. Furthermore, the authors wish to start an academic dialogue on the issue, at the highest possible professional level.

The authors believe that they managed to define the common points in the coordinate system of philosophies defined by existential disability—philosophical anthropology, existential philosophy and Buddhist emptiness philosophy—and the empirical studies (constructed in this case with the assistance of the science of travel). These are and may be of help, in both the present and the future, to make us repeatedly reconsider, and, in the contexts of the latest facts and situations, upgrade the issue of fundamental accessibility as a basic human endowment and characteristic, building upon Heidegger’s, Jaspers’s, Bergson’s, Kropotkin’s and Nagajurna’s philosophies [7,14,15,23,50].

The extended hermeneutic method of analysis developed by the authors, called philoscopic, has stood the test of time and scholarship many times [2,6,72]. Let us hope it will be valid now too, for the science of travel, which in the authors’ opinion is an empirical carrier of their philosophical scrutiny. It is also hoped that the progressing discipline will be given new momentum and will strengthen by the findings of this specific examination method. Finally, the paper may contribute this way to the acknowledgement of the research methodology of philosophical scrutinies, in this case to the reconsideration of the paradigm of fundamental accessibility and the acceptance as a new paradigm in the case of technical accessibility.

As regards the findings of the empirical study, the market of the travels of people with disabilities is a very much underutilised segment of tourism for the time being [73,74]; in several countries, including Hungary, a number of factors hinder the travel of those who have locomotory disorders, problems with their sight, hearing, etc. Their needs and expectations, however, do not fundamentally differ from those of their “healthy” counterparts, and so their inclusion in tourism would not cause any major difficulty, and their (ever-growing) proportion from the total population makes them a prosperous market segment from several aspects. The study demonstrates, by analysing the replies of hundreds of respondents to a questionnaire survey conducted in the framework of an international project (including Hungary, Croatia, Germany, Italy and Spain), the problems that people with disabilities are facing in tourism, the factors hindering their touristic activities, their travel habits, the present state and the change of the attitude of societies towards people with disabilities, the impact of tourism of the quality of life of people living with disabilities. Furthermore, recommended solutions to the problems raised are discussed. One, very important element of these potential solutions is the extension of the technical solutions of accessibility to the issue of more holistic fundamental accessibility. This, however, requires the interdisciplinary definition and acceptance of the new and open paradigm of accessibility. The need for such a new paradigm is underlined by complementary philosophical and empirical research findings.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, J.F. and Z.R.; methodology, J.F. and Z.R.; validation, J.F., Z.R. and L.D.D.; formal analysis, Z.R.; investigation, J.F.; data curation, J.F. and Z.R.; writing—original draft preparation, J.F. and Z.R.; writing—review and editing, Z.R.; visualization, J.F. and Z.R.; supervision, J.F., Z.R. and L.D.D.; project administration, Z.R. and L.D.D. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Dulházi, F.; Zsarnóczky, M. Az akadálymentes turizmus, mint rehabilitációs “eszköz” (Accessible Tourism as a Rehabilitation “Too”l). In Arccal Vagy Háttal a Jövőnek? LX. Georgikon Napok, Keszthely; Pintér, G., Zsiborács, H., Csányi, S.Z., Eds.; Pannon Egyetem Georgikon Kar: Keszthely, Hungary, 2018; pp. 56–61. [Google Scholar]

- Farkas, J.; Petykó, C.S. Utazás az akadálymentesség, a fogyatékosság és a fenntarthatóság multidiszciplináris és bölcseleti dimenzióiba (A Journey to the Multidimensional and Philosophical Dimensions of Accessibility, Disability and Sustainability). Tur. Bull. 2019, 19, 13–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zsarnóczky, M. The Future Challenge of Accessible Tourism in the European Union. Vadyb. J. Manag. 2018, 2, 39–43. [Google Scholar]

- Gonda, T. Travelling habits of people with disabilities. GeoJ. Tour. Geosites 2021, 37, 844–850. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hadot, P. What is Ancient Philosophy? Harvard University Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Farkas, J. A szimbiotikus embertől az egzisztenciálisan fogyatékos emberig (From symbiotic man to existentially handicapped man). Educatio 2020, 29, 479–486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farkas, J. Az Egzisztenciális Fogyatékosságban Rejlő Kiteljesedési Lehetőségek—Betekintés a Fogalom Jelentésvilágába (Possibilities of Fulfilment to Be Found in Existential Disabilities—An Insight into the Meaning of the Concept). Ph.D. Dissertation, Corvinus University of Budapest, Budapest, Hungary, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Kuhn, T.S. The Structure of Scientific Revolutions, 4th ed.; The University of Chicago Press: London, UK, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Feyerabend, P. Against Method, 4th ed.; Verso Books: New York, NY, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Lakatos, I.; Musgrave, A. (Eds.) Problems in the Philosophy of Science Proceedings of the International Colloquium in the Philosophy of Science London, 1965; North-Holland: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 1968. [Google Scholar]

- Békés, V. A Hiányzó Paradigma (The Missing Paradigm); Latin Betűk Kiadó: Debrecen, Hungary, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Szántó, Z.O.; Aczél, P.; Csák, J.; Szabadhegy, P.; Morgado, N.; Deli, E.; Sebestény, J.; Bóday, P. Social Futuring Index: Concept, Methodology and Full Report 2020; Corvinus University of Budapest, Social Futuring Center: Budapest, Hungary, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Gonda, T.; Raffay, Z. A fogyatékossággal élők utazási szokásai (Travel habits of people with disabilities). Tur. Vidékfejlesztési Tanulmányok 2021, 6, 20–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heidegger, M. On the Way to Language; HarperCollins Publishers: New York, NY, USA, 1982. [Google Scholar]

- Jaspers, K. Way to Wisdom: An Introduction to Philosophy; Yale University Press: New Haven, CT, USA, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Heidegger, M. Sein und Zeit (Being and Time), 19th ed.; Niemeyer: Tübingen, Germany, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Gadamer, H.G. Truth and Method, 2nd Revised Translation; Crossroad: New York, NY, USA, 1989. [Google Scholar]

- Bergson, H. The Creative Mind. An Introduction to Metaphysics; Dover Dublications, Inc.: Mineola, NY, USA, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Sartre, J.P. Existentialism Is a Humanism; Yale University Press: New Haven, CT, USA; London, UK, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Bird, J.; Barry Curtis, B.; Mash, M.; Putnam, T.; Robertson, G.; Tickner, L. (Eds.) Travellers’ Tales: Narratives of Home and Displacement; Routledge: London, UK, 1994. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Merleau-Ponty, M. The Visible and the Invisible; Norhwestern University Press: Evanston, IL, USA, 1968. [Google Scholar]

- Fehér, J. Nágárdzsuna, a Mahájána Buddhizmus Mestere (Nagajurna, Master of Mahayana Buddhism); Farkas Lőrinc Imre Könyvkiadó: Budapest, Hungary, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Dreyfus, G.B. Recognizing Reality: Dharmakīrti’s Philosophy and Its Tibetan Interpretations; State University of New York Press: Albany, NY, USA, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Bradatan, C. Dying for Ideas: The Dangerous Lives of the Philosophers; Bloosmbury: London, UK, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Ziarek, K. The Return to Philosophy? Or: Heidegger and the Task of Thinking. J. Br. Soc. Phenomenol. 2008, 39, 249–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fehér, M.I. Heidegger és a Szkepticizmus (Heidegger and Scepticism); Korona Nova Kiadó: Budapest, Hungary, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Plato. The Republic. Available online: http://classics.mit.edu/Plato/republic.html (accessed on 12 January 2022).

- Hegel, G.W.F. Elements of the Philosophy of Right; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Schwendtner, T. Wissenschaft als Philosophie. Bemerkungen zum Wissenschaftsbegriff von Wilhelm Szilasi. In Traces de l’être. Heidegger en France et en Hongrie; Jean, G., Ádám, T., Eds.; L’Harmattan: Paris, France, 2014; pp. 211–219. [Google Scholar]

- Farkas, J.; Petykó, C.S. Disability, accessibility, and mobility as basic existential characteristics. In Opportunities and Challenges of Barrier-Free Tourism in Hungary: Results and Recommendations of a Scientific Workshop during the Conference "European Peer-Counsellor Training in Accessible Tourism—Peer-AcT" on September 4, 2020 in Orfü (Hungary); Gonda, T., Schmidtchen, R., Eds.; Bundesinstitut für Berufsbildung: Bonn, Germany, 2020; pp. 89–99. [Google Scholar]

- Derrida, J. Of Grammatology Corrected Edition; The Johns Hopkins University Press: Baltimore, MD, USA, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Deleuze, G.; Guattari, F. What Is Philosophy? Columbia University Press: New York, NY, USA, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Byung-Chul, H. The Disappearance of Rituals: A Topology of the Present; Polity Press: Cambridge, UK, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Marosán, B.P. Variációk az élettörténetre (Variations for life stories). Filozófiai Szle. 2004, 4, 495–523. [Google Scholar]

- Kolakowski, L. Metaphysical Horror; The University Chicago Press: Chicago, IL, USA, 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Michalkó, G. Boldogító Utazás (Beatific Travel); MTA Földrajztudományi Kutatóintézet: Budapest, Hungary, 2010. [Google Scholar]