1. Introduction

The problem of employee turnover has been investigated in recent years because more and more countries and organizations are faced with the lack of an adequate labor force [

1,

2,

3]. The most important managerial task related to human resource management (HRM) is the attraction of qualified human resources and the struggle for retention of talent. Employee turnover is one of the biggest challenges for all organizations. It may cause different economic, psychological, and organizational consequences [

3] (p. 32), such as the loss of human capital and the loss of institutional knowledge [

2] (p. 1467).

Numerous challenging factors influence the business environment and labor market; however, the most important are the presence of the new generation of employees (Y and Z generations) on the labor market, who have different views and ideas about jobs, careers, and authority; contemporary political, social, and economic challenges; the COVID-19 pandemic; and especially rapid technological development. In such conditions, many organizations struggle to maintain their competitiveness. In addition, several organizational factors like managerial style, organizational culture, HR practices (staffing, compensation, training, career development, etc.), job satisfaction, and stress and conflict management influence the organizational ability to be an attractive employer and to retain employees. Companies need to create working conditions that will attract, motivate, and retain employees.

According to previous studies, one possible response to many challenges in HRM is the implementation of flexible working arrangements (FWAs) as a new and more flexible way of organizing traditional jobs and working positions; this allows employees to have more possibilities to maintain work–life balance and to choose how and when they perform business activities [

4,

5]. FWAs can be defined as a “work option that provides a control for employees in terms of ‘where’ and/or ‘when’ to perform their job tasks” [

4] (p. 3). This level of control over job tasks means greater perceived autonomy of an employee, which could lead to a greater possibility for balancing work and private life and to the preservation of time and energy of an employee [

6]. This is one of the most important benefits of FWAs.

Previous research pointed to the conclusion that FWAs are seen as HRM practices that comprise greater productivity, organizational commitment, job satisfaction, lower absenteeism, lower turnover intentions, etc. [

5,

6]. On the other hand, some of the limitations of FWAs lie in the fact that not all types of FWAs would have such effects in organizations. Potential costs for employees could be related to increased stress if the workload is in excess of the reduced work time or when employees are required to attend to work issues on their days off [

5] (p. 734). This could harm employee performance and diminish FWAs’ positive effects.

The above-mentioned relations are derived from the social exchange theory, which states that positive and benevolent behavior of one person (sender) to another (receiver) in an interdependent relationship would create the potential for the receiver to feel obligated to reciprocate with returned positive behavior [

4]. It is important to emphasize that this relation or exchange in the employment context is not a contract; it is more about the beliefs and perceptions of both sides, that is, employees and employers. Namely, if employees perceive the work environment and other HRM practices of employers as positive and satisfactory, they could feel obligated to show positive work attitudes and behaviors. On the contrary, if employees perceive HRM practices as not satisfactory, they will show negative organizational behavior and attitudes. Based on the social exchange theory and previous research, it is expected that FWAs would have positive effects on turnover intentions, as a type of employee behavior, in terms of decreasing turnover [

4,

5,

6,

7]. In addition, FWAs are seen as a driver of higher job satisfaction [

8], one of the most important employee attitudes related to the willingness to stay or to leave the organization [

5].

Based on the above, the main aim of this paper is to investigate the relationship between FWAs and turnover intentions of employees, and the mediating effect of job satisfaction as an important factor related to both constructs. The methodology used in the paper consists of theoretical and empirical research. The theoretical research is based on a literature review, using the desk-research method. The empirical part of the paper is based on the analysis of the sample of 219 employees from business organizations in Serbia, who gave responses to questions on FWAs, turnover intentions, and job satisfaction. The novelty of this paper lies in the mediation analysis, since in the previous research, all three constructs were usually examined in isolation, without considering the mediating effects. Several prior studies investigated similar relations, but without mediation analysis.

The paper consists of five sections. The

Section 2 is dedicated to the theoretical development of hypotheses and the main argument related to flexible working arrangements, job satisfaction, and turnover intentions. The

Section 3 presents the research methodology. Results of the study are presented in the

Section 4, while discussion and conclusions are given in the

Section 5 and

Section 6 of the paper, respectively.

2. Theoretical Background

Flexible working arrangements have gained great attention recently due to the great negative impact of the COVID-19 pandemic all over the world. FWAs are seen as a solution for many business issues, but are mainly related to work–life balance. FWAs could increase work control, and are defined as constructs that possess two major forms of flexibility, related to time (flex-time) and related to location (flexplace) [

9]. FWAs are generally seen as a “negotiated term of employment related to timing and/or place of work” [

10]. FWAs are also explained as “employer-provided benefits that permit employees some level of control over when and where they work outside of the standard workday” [

11,

12] and are usually related to home-based working, flex-time, reducing or extending contract hours, or allowing overtime hours to support employees’ work–life balance and improve firm performance [

13] (p. 727).

Flexibility in work has a great effect on employees and employers. Employees are more ready to “join an organization, be satisfied with the jobs they do and continue working with the same employers. Employers have become aware of some outcomes, such as being interested, motivated, and retaining their talented employees, having satisfied and numerous engaged employees, along with improving employee effectiveness and success” [

14]. Previous research investigated the effects of FWAs on employees’ behavior and attitudes, such as turnover [

12,

15], engagement [

16], job satisfaction [

17], absenteeism [

18], etc. In most of these areas, FWAs showed a positive relation to the dependent variables, in terms of increasing job satisfaction, engagement, or performance, while decreasing absenteeism and turnover.

For this research, bearing in mind that more and more companies are struggling to retain their best employees, the authors decided to investigate relations between FWAs, job satisfaction, and turnover intentions of employees. The mentioned constructs are important outcomes of organizational behavior strategies; organizational human resource management practices influence organizations such that the outcomes can be measured by employee performance, job satisfaction, absenteeism, and turnover [

19].

Regarding turnover, the best way to investigate the turnover of employees is to follow their turnover intentions, as a reliable predictor of actual turnover behavior [

2]. Sandhya and Sulphey stated that turnover intentions can be defined as “a mental decision prevailing between an individual’s approach with reference to work to continue or leave the work”; it is “a measure for understanding turnover before employees actually quit or leave organizations” [

1] (p. 327). FWAs, in terms of gaining more control over the job and the usage of different work types, like teleworking, flex-time, home-based work, etc., should decrease the turnover intentions of employees. This idea is derived from social exchange theory, explained in the previous section of the paper, in which positive employer practices towards their employees should cause positive work behavior (i.e., decision to stay, reduction of turnover intentions, and turnover itself) and work attitudes (commitment, engagement, job satisfaction, etc.). In most of the previous research, this hypothesis has been proven [

20], but the question is what is happening now, during the COVID-19 pandemic, when more companies are using FWAs [

21] and when different external factors are moving organizations towards greater usage of FWAs.

FWAs like flex-time (which allows employees to vary the times when they start and finish work), sabbaticals (paid leave from work), and home-based work (work from a location outside workplace, in a household) increased job satisfaction, while sabbaticals and home-based work decreased turnover intention of employees in a sample of German employees [

20]. In addition, Tsen et al. [

4] investigated 16,920 respondents from 35 countries and found that perceived job independence significantly moderates the relationship between FWAs and turnover intention. They found that employees who perceive their jobs as highly independent have a lower turnover intention when they are using FWAs such as flex-time, flex-leave, or home-based work, while more interdependent employees who use home-based work and flex-time may have a greater intention to leave [

4] (p. 1). In a similar study, the authors found that flexible work hours had no significant effect on job satisfaction, but they reduced staff turnover. In contrast, job satisfaction improved with job sharing and flexible leave [

5].

Masuda et al. [

22] investigated the relationship between FWAs and job satisfaction, turnover intentions, and work–family conflict in Latin American, Anglo, and Asian country clusters in a sample of 3918 managers from 15 countries. The results showed that there is a negative relationship between flex-time work and turnover intentions in the Anglo cluster and that the relationship is not significant for the Latin American cluster. In addition, a positive relationship was found between flex-time availability and job satisfaction for the Anglo cluster, but not in the Latin American cluster.

De Sivatte and Guadamillas [

23] also investigated similar relations in a sample of 480 employees in Spain and noted that FWAs have a negative relation to turnover intentions (these practices reduce the intention of employees to leave the organization) and a positive relation to employees’ commitment. Mullins et al. [

24] found that FWAs are associated with lower dissatisfaction of employees, but with small effects on employee intention to leave the organization.

According to these research results, FWAs mostly have a positive effect on turnover intentions in terms of decreasing it, and therefore these programs could be used as an employee retention strategy. Since FWAs are understood as employee-friendly practices, properly implementation could cause a positive perception of employees, and in exchange, they could demonstrate more positive working behaviors by reducing their intention to leave the organization.

Based on the aforementioned, the first hypothesis of the research is as follows:

Hypothesis 1 (H1): FWAs have negative relations to turnover intention.

In addition to behaviors, employees could respond to positive HRM practices with their positive work attitudes, such as job satisfaction, job engagement, job commitment, etc. However, in most of the mentioned research, one of the commonly explored variables was job satisfaction, as employee attitude on the job, which consists of evaluative, cognitive, and affective components [

25], shows how much an employee is satisfied with the job. It has been proven that employees with a high level of job satisfaction will have lower turnover intentions [

5,

26]; therefore, job satisfaction is considered as a cause of employees’ turnover intentions. In addition, FWAs are found to be positively related to job satisfaction [

20,

24], and on that basis, job satisfaction can have a mediating on the relationship between FWAs and turnover intentions [

16]. According to the results of the research of Azar et al., job satisfaction and work–life conflict mediate the impact of FWA use on turnover intentions. The authors of this paper propose that job satisfaction will mediate this relationship and that employees who are offered FWAs will experience a lower level of turnover intention when they are satisfied on the job.

Hypothesis 2 (H2): Job satisfaction mediates the relationship between FWAs and turnover intentions.

4. Results

The authors used the program “Smart PLS” to present the results of the research on the mediating role of job satisfaction in the relationship between FWA and turnover intentions. To investigate the proposed relations, PLS-SEM analysis was performed. First, the authors calculated the measurement and structural model parameters and generated the accompanying bootstrap estimates. The study was performed to assess the total and direct effects of the FWA construct on the dependent variable (turnover intentions) and the indirect effects via the mediator (job satisfaction). The analysis of the obtained data based on the completed questionnaires was divided into two parts; the authors first investigated the measurement model, and then the research hypotheses were tested.

Table 2 shows the descriptive statistics for each indicator in the study.

For the first step, the authors loaded reflective indicator loadings, internal consistency reliability, convergent validity, and discriminant validity. This type of measurement is proposed for reflective constructions in the model [

31]. In addition to the mentioned methods, the CMB—common method bias—test was also performed. The authors Berber, Slavić, and Aleksić [

32] state in their paper that the lowest eligibility limit for factor load is 0.708. Load factors between 0.4 and 0.7 should be retained only if their removal does not have an impact on AVE and Composite Reliability [

15,

33]. Certain items had to be removed from further analysis because their loads had very low values. Based on the above,

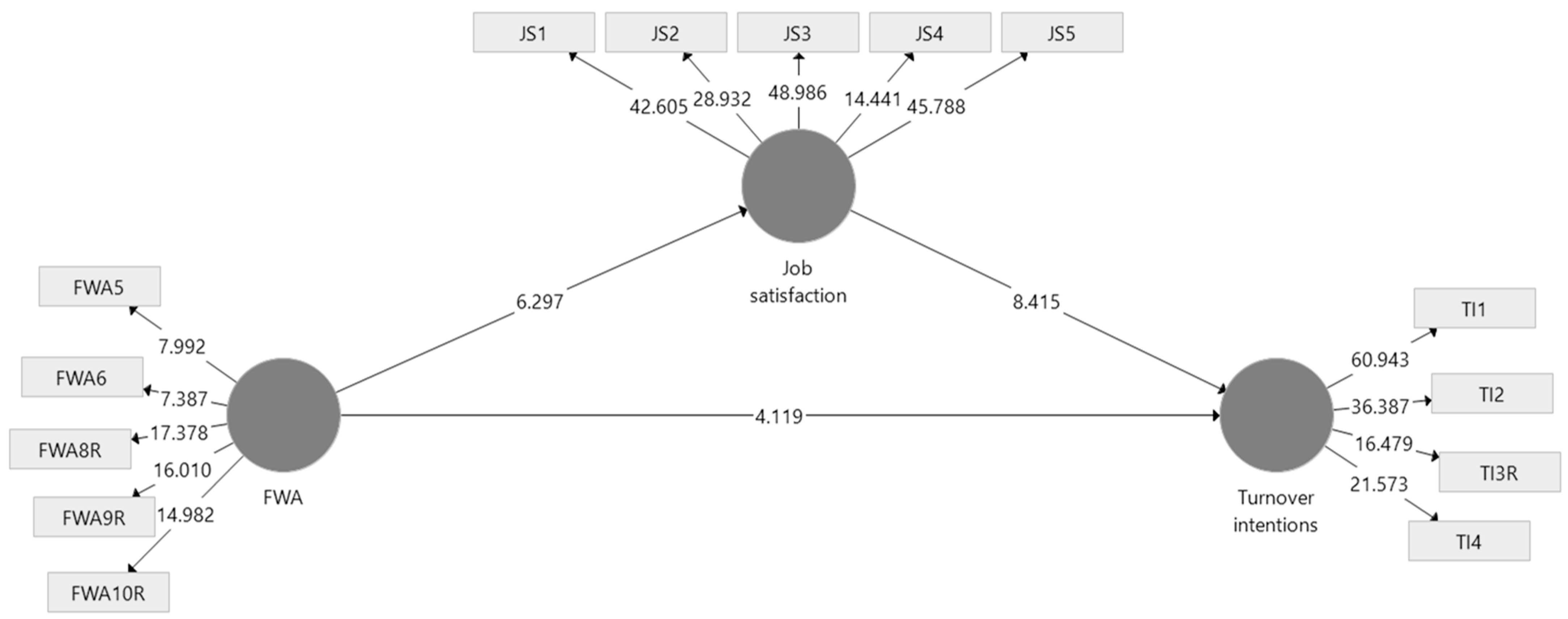

Figure 1 presents the retained items with loadings above 0.708 (see

Figure 1).

The following table shows the indicator reliability and construct reliability and validity.

Table 3 shows the reliability test, performed by calculating Cronbach’s Alpha, Composite Reliability, and Average Variance Extracted. Based on the data obtained by calculating Cronbach’s Alpha, we noticed that the values ranged from 0.768 (FWA), to 0.851 (turnover intentions), to the highest value, recorded for job satisfaction, 0.904. Some of the authors recommend the lowest acceptable limit of Cronbach’s Alpha be 0.6 [

34,

35,

36].

The value of composite reliability of constructs ranges from 0.833 (FWA), to 0.9 (turnover intentions), to the highest value, recorded for job satisfaction, 0.929. Some of the authors recommend that the lowest limit of acceptability of CR is 0.7 [

37,

38]. Based on the results presented in the table above, we conclude that the CR criterion was met. Composite reliability can be used as an alternative, because CR values are slightly higher than Cronbach Alpha values, but this difference is relatively insignificant [

39].

Convergent validity was assessed by testing Average Variance Extracted (AVE). The table above shows the AVE values, and they range from 0.5 (FWA), to 0.694 (turnover intentions), to the highest value, recorded for job satisfaction, which is 0.726. The lowest acceptable limit of AVE is 0.5 [

40,

41]. Based on the data shown in the table above, the limit of acceptability was met, and therefore we conclude that Convergent validity was satisfied in all three constructs.

Discriminant validity can be assessed by using Cross-loadings indicators, the Fornell and Larcker criterion, and heterotrait–monotrait correlation ratios [

42].

Table 4 shows the discriminant validity cross loadings.

If the load of the indicator for its constructive structure is greater than any other construction, the measurement model has a corresponding discriminant validity [

43]. Based on the data obtained in the table above, the results show that a load of each block is greater than a load of any other block in the same column and row, clearly separating each latent variable. The cross-loading output confirms the discriminant validity of the measurement model.

Table 5 displays discriminant validity via the Fornell–Lacker criterion.

Based on Fornell–Lacker criteria, the root of the AVE latent variable must have a value that is greater than the value of all correlations with the latent variable [

40]. Based on the obtained data, we conclude that discriminant validity is satisfied because the value of the AVE root on the diagonal is greater than all the values shown below for each variable.

Table 6 shows discriminant validity of the heterotrait–monotrait (HTMT).

All values of HTMT below 0.9 show that the components differ from each other to a satisfactory extent, which means that they describe different phenomena [

44]. Based on the obtained data shown in the table above, we conclude that the criterion of discriminant validity according to HTMT is met because all the obtained values are below 0.9.

The common method bias (CMB) was investigated using the full collinearity approach [

45]. The threshold value of VIF factors is 3 [

44], while some authors accept VIF values less than 5 or even 10, indicating the harmfulness of collinearity [

46,

47,

48]. Based on the data shown in

Table 7, the multicollinearity analysis shows that VIF values are in most cases below 3 but also that there are values such as (JS1, JS3, TI1, and TI2) that record values slightly above 3; however, these are accepted based on the indicators of authors who accept VIF values up to 5.

The final step is to analyze the relationship between the independent variable (FWA) and the dependent variables of job satisfaction and turnover intentions, as well as the mediating role of job satisfaction in the relationship between FWA and turnover intentions. R2 (R-squared), as a statistical measure of the proportion of the variance for a dependent variable that is explained by an independent variable, shows that for “Job satisfaction” it is 13.8%, while in the case of “Turnover intentions” it is 39.2%, explained by the independent variable “FWA” in the model.

Table 8 presents the means, standard deviations, T-statistics, and

p-values of the variables in the model.

Based on the

Table 8, we conclude that there is a positive and statistically significant relationship between FWA and job satisfaction (β = 0.371; T = 6.297;

p = 0.000), a negative and statistically significant relationship between FWA and turnover intentions (β = −0.198; T = 4.119;

p = 0.000) and a negative statistically significant relation between job satisfaction and turnover intentions (β = −0.525; T = 8.415;

p = 0.000). Regarding the mediating role of job satisfaction in explaining the relationship between FWA and turnover intentions, a negative mediation relationship was found, since the indirect effect of FWA on turnover intentions through job satisfaction was significant (β = −0.195; T = 5.932;

p = 0.000). These relations are presented in

Figure 2.

5. Discussion

The results of this study pointed to the positive effects of FWAs and job satisfaction on turnover intentions. Job satisfaction mediates the relationship between FWAs and turnover intentions. There is an indirect effect of FWAs on turnover intentions through job satisfaction. The implementation of FWAs increases job satisfaction and decreases turnover intentions, hence providing possibilities for companies to retain their best employees and create a modern working environment that will enable employees to have more possibilities and more safety in the contemporary business environment, in the context of the COVID−19 pandemic. The present study results showed the expected relations, as FWAs have positive relations to job satisfaction and negative relations to turnover intentions [

5,

16]. Greater usage of flexible working arrangements leads to higher job satisfaction and lower turnover intentions, and based on these results, both proposed hypotheses are confirmed. A positive and statistically significant relationship between FWA and job satisfaction (β = 0.371; T = 6.297), a negative and statistically significant relationship between FWA and turnover intentions (β = −0.198; T = 4.119) and a negative statistically significant relation between job satisfaction and turnover intentions (β = −0.525; T = 8.415;

p = 0.000) were found. Regarding the effect of job satisfaction on the relationship between FWA and turnover intentions, a negative mediation relationship was found, where FWA had a negative impact on turnover intentions through job satisfaction (β = −0.195; T = 5.932), which means that employees who are offered FWAs and who are more satisfied with their job express lower turnover intentions. In addition, the results of the tests of the questionnaire and the data showed a high level of validity and reliability; therefore, these instruments could be used for the investigation of the mentioned constructs in a specific business environment.

These results are in the line with previously reported results, where FWAs also had a positive impact on job satisfaction [

8,

12,

17,

24] and a negative impact on turnover intentions [

4,

5,

6,

7]. Employees that perceived FWAs as offering the potential for maintaining balance between work and private life expressed a higher level of job satisfaction and a lower level of intention to leave (turnover intention). They were more satisfied, and on that basis, they could show more positive work behaviors, such as reduced turnover intentions. The results of the mediation analysis, which was the main goal of the research, are in line with other researchers, especially Azar et al. [

16], who also confirmed mediation. Job satisfaction is the mediator in the relationship between FWAs and turnover intentions. Additionally, the results are in the line with the social exchange theory [

5]. With the respect to FWAs, the results of this research found employees who understand and perceive FWAs as positive and helpful HR practices offered by their employers, felt more satisfied on the job, because they had more autonomy and increased decision-making possibilities regarding their work-related issues, and they reciprocated positively toward their employers. This positive reciprocation response is usually understood as a will to stay in an organization and a reduced intention to leave.

Therefore, FWAs should be carefully planned, monitored, controlled, and enhanced by managers to provide better working conditions and try to retain talent in an organization. An important role in this process should be dedicated to leaders, because they are seen as a key factor in building a positive psychological climate in an organization [

49], especially in times of crisis, such as the pandemic. The results can be interpreted in line with the pandemic. Since the main issue related to the pandemic is the fear of becoming infected with the COVID-19 virus, the decision to implement FWAs, especially home-based work, teleworking, or flex-time, can be very stimulative for employees in terms of their satisfaction related to the preservation of their health and security. Additionally, when employees see that the company and their managers are struggling to help them to stay healthy and offer such beneficial working programs, their intention to leave can be decreased. On the other hand, lower turnover intention can occur because of the fear of employees that they would lose their job due to the negative effects of the pandemic on the business. This reason is not related to the implementation of FWAs, and therefore this area also needs to be investigated.

6. Conclusions

This paper has practical implications that lie in the potential of implementation of FWAs in business to decrease the turnover intentions of employees. This is important, since almost all companies today noted that lack of talent, higher levels of occupational stress [

50], and high levels of employee turnover are the most important HRM issues. Allowing employees greater control over their jobs in terms of how, when, and where the job would be done makes them more satisfied, with reduced stress, and less willingness to leave their organizations. Of course, FWAs are not enough to reach this goal. Some other factors, such as strong organizational culture and climate, adequate leadership style, other HRM practices, are important for both job satisfaction and turnover of employees. Therefore, companies should analyze, plan, and prepare the FWAs that can be offered to employees as a part of a broader strategy for the retention of employees. This is especially important in times of new challenges, such as the COVID-19 pandemic, which has increased work in the virtual environment [

51], made digital business and digital strategies even more important [

52], and greatly increased teleworking. This research is one of the first to deal with the issues of FWAs, job satisfaction, and turnover intentions in Serbia, using this specific methodology and data analysis. Therefore, the results of this paper can serve as a starting point for the creation of strategies and actions of flexible working programs, as well as their adequate implementation, to lead to HR outcomes like job satisfaction and the decision to stay at a company.

The important theoretical implications lie in the increased understanding of the effects of job satisfaction on the relationship between the perception of employees regarding offered flexible working arrangements and their turnover intentions. According to Azar et al. [

16], all three constructs are usually investigated separately, without mediation analysis. This study tested the mediation effects, and the results pointed to the conclusion that job satisfaction is a mediator in the proposed relationship, which is in the line with previous research [

16] and with the theory of social exchange. The study adds to the accumulating body of knowledge on the impact of FWAs on both job satisfaction and turnover intentions, but also on specific relations between these three constructs.

The present study has potential limitations. One of the most important is the size of the sample. Although 219 employees can be seen as a small sample, the usage of the Smart PLS program proved that the number of respondents in the sample was adequate to obtain results and for testing the validity of the data. The 219 responses were acceptable for the PLS-SEM procedure, because this number met the requirement related to the ten-times rule: “ten times the largest number of inner model paths directed at a particular construct in the inner model” [

37].

In addition, the authors of this research did not use controls for the proposed relations, like gender, age, or sector of business; this might provide interesting results. Therefore, the inclusion of age, marital status, family status, gender, and other control variables as moderators in the analysis can be valuable and is recommended for future research. This will further elucidate the practical implications for managers implementing FWAs on an organizational level.