Abstract

In the event of any crisis, such as, in this case, the COVID-19 pandemic, new challenges arise, ranging from social and environmental phenomena to economic issues. One of the most affected economic sectors was the cultural one, especially independent artists, whose financial stability is usually inconsistent. The aim of this article was to test the immediate reactions of the cultural sector, both public and private, to the pandemic shock and, implicitly, to the restrictions imposed during the state of emergency in Romania (27 February–14 May 2020). By using grounded theory, 36 public documents of cultural stakeholders were coded and analyzed. All documents were identified in the Romanian online environment during the state of emergency. Based on the identified interrelationships, it was found that the independent contractors, self-employed workers in the creative-cultural sector, whether or not associated with NGOs or employees of public institutions, need financial and community support. However, the resilience of the cultural sector is conditioned by the creation of new multi-level policies for crisis management.

1. Introduction

The evolution of human communities has been affected by numerous critical events, from those associated with natural phenomena—earthquakes, tsunamis, floods, typhoons— to epidemiological threats or pandemics, namely Ebola, swine flu H1N1, bird flu H5N1 and severe acute respiratory syndrome SARS-CoV [1,2]. The identification of COVID-19 in Wuhan, China at the end of 2019, followed by a second outbreak of infections in Italy, in February 2020, along with a rapid spread worldwide, created a new pandemic context, which is yet to be declared the biggest challenge of the 21st century [3,4]. This major global crisis has affected not only the health of human communities, but also the vulnerable medical and socioeconomic systems. In response to these challenges, decision-makers have developed plans and strategies aimed mostly at successfully managing issues related to public health and major economic sectors. However, putting solutions and measures into practice most often proves deficient and still triggers huge medical and socioeconomic costs, therefore leaving the population clearly vulnerable to a possible replication of events or the occurrence of a new disaster [5].

Economic stagnation, recession and job insecurity are just some of the fears associated with the changes imposed by the current period [6]. Additionally, the most vulnerable people are those who were already socioeconomically disadvantaged at the time of the COVID-19 pandemic outbreak [7]. The independent workers in the creative-cultural sector are part of this social group. Difficulties faced by artists and creative workers in the labor market are well known and the financial insecurity caused by the deficient public policies along with the complete lack of or low funding from the government [8] is also a reality.

The current challenge is to find solutions to adapt to the given conditions and mitigate their negative impact in the short term, whilst further identifying new opportunities for these fragile economic operators in the medium term [9]. The evolution of the new Coronavirus (SARS-CoV-2) in Romania has been similar to what was recorded in the countries of Central and Western Europe. The first case was reported late February and subsequently the number of infected people has increased abruptly. An important contributing factor was the repatriation of the migrant workers from various European countries, after the outbreak of the pandemic crisis. The main aim of this study was to test the immediate reactions of the cultural sector, both public and private, to the pandemic shock and, implicitly, to the restrictions imposed during the state of emergency in Romania (27 February–14 May 2020). In this sense, all public documents were identified and analyzed, provided in the Romanian online space and signed by various public or private stakeholders. The research questions defining the approach of our analysis were: What types of initiatives were proposed? What trends emerge from their content? What do they address and to whom are they addressed? How do permanent cultural operators resonate with the independent cultural workers and their adaptation to the current conditions? We opted for a bottom-up approach, focusing on the initiatives released by the civil cultural society, and not on those coordinated by the government, which are not currently visible for this sector.

1.1. Economic Vulnerability of the Independent Cultural-Creative Sector in a Pandemic Context

Economic vulnerability expresses the likelihood that the economic development of a sector will be constrained by the occurrence of exogenous shocks generated by various critical events [10,11]. The outbreak of pandemic episodes generates major economic risks, which could easily affect government budget allocation; hence, limited economic resources must be divided among multiple competing priorities [12]. During pandemics, economic instability is even more visible, and a series of tensions arise between state and citizens. Additionally, they usually highlight national management actions that would imply socioeconomic discrimination [13,14] as a result of the higher attention being paid to the state-owned and private macro-enterprises.

Socio-economic risks are very much connected to the evolution of the COVID-19 pandemic. The rapid increase in the number of infections and deaths in many regions around the world has led states to declare a state of emergency [15]. This included quarantine for infected people and isolation for their contacts, social distancing, but also a series of restrictive measures regarding traffic and public events, along with new programs and regulations for carrying out economic activities. In this context, reducing working hours, switching to rotating schedule or the transformation of some activities into remote work were among the solutions found by employers to ensure resilience. Still, in some fields, these measures proved less feasible or even impossible to put into practice. As a consequence, many of the employees became either technically unemployed or temporarily or permanently dismissed due to insufficient workload [7,16].

The immediate economic effects of the current pandemic crisis are felt among economically disadvantaged actors in terms of access to economic and social resources [17,18]. Financial stress appears mostly in the case of non-profit and non-institutionalized organizations, whose evolution is permanently influenced by fluctuations regarding the availability of economic resources and budget deficits, especially in the absence of public support [19]. The independent cultural-creative sector is no exception, especially since it brings together freelance artists, NGOs and creative workers with flexible working hours and in most cases financially supported by sponsorships, various grants and by the direct and immediate consumption of the cultural products provided [20]. The public is the center of this sector, since it will pay enough for the artistic creation to continue [21]. The revenue concentration [22], as a result of obtaining income from more than one source, gives independent cultural-creative organizations a low degree of flexibility in the face of financial shocks. Much more, in the current pandemic context, the vulnerability of the cultural sector is amplified by the change in consumer behavior [23], which is influenced by its own financial insecurity and restrictions. Given this, their focus is strictly on ensuring the basic necessary goods, and not on purchasing entertainment services. Therefore, the current crisis generates a sudden loss of opportunities, which poses a threat to the survival of fragile workers in the cultural and creative sector [9].

1.2. Resilience as a Response to the Threat of COVID Economic Disaster

The increased economic risks to which many vulnerable organizations and companies are exposed require finding the best methods to ensure their resilience. As in the case of the crisis resilience model of the Islamic states [16,24], the potential impact of the pandemic crisis should be assessed, and stakeholders who could actively engage in its management should be identified. During times of extreme uncertainty, the survival and prosperity of freelancers and small businesses are ensured through resilience and adaptability [25,26].

Proposed by Holling in 1973, the concept of resilience defined the ability of ecosystems to persist in their original state although affected by disturbances. Subsequent approaches define resilience as the property of a system, which, in the case of an external shock, allows it (1) to restore to the previous socioeconomic state [27,28], (2) to absorb sudden changes and adapt to new behaviors and forms [29,30,31] or (3) to develop as a completely new and different socioeconomic structure [32].

Resilience takes many forms, one of them being social resilience, which is of the greatest relevance during pandemics, when solidarity and civic involvement become most often fundamental in supporting some socioeconomic activities. Based on social unity within a group or between different groups, social resilience aims at social cohesion, adaptation and finding optimal solutions for managing critical events [26,31,33]. Additionally, beyond mutual support, acceptance and attention to others in a common effort to maintain social resilience, an important role is played by social relations [34] and social capital [33,35]. According to Ostadtaghizadeh et al. [36], social resilience is ensured through social and cultural capital, community, population and knowledge on risk management. At the same time, social resilience is influenced by the prior economic and political conditions before the onset of the disruptive phenomenon [37].

In the case of the independent cultural-creative sector, resilience takes on a cultural dimension. This feature implies both a continuity of activities developed based on talent and artistic skills and also adaptation to change and risk management on behalf of the active people in this field and their socio-cultural relationships [38,39]. Being continuously exposed to stress due to financial insecurity, artists and independent creative workers tend to show low resilience to critical events [32]. These professionals feel psychologically rewarded seeing their activity as extremely attractive and satisfying [40]. Hence, by imposing certain boundaries on cultural and creative activities as management measures against the spread of the SARS-CoV2 virus, namely closing galleries, canceling cultural and artistic events, restrictions on the movement and organization of events, subsequently affecting the exchange of good artistic practices, not only nullifies financial opportunities and benefits, but constrains cultural freedom [41].

In this context, the digitization of activities and online performance were some of the first measures of resilience applied by artists and creative workers. Thus, social media has become the main communication channel. It was used both for the real-time dissemination of activities carried out, thus creating the connection with the general public [42], and as a space for expressing opinions and the dissemination of information on solidarity actions [43]. All along, the promotion of initiatives to build the resilience of the independent cultural sector (fundraising, manifests, workshops, petitions, etc.) has become part of the digital action. Setting up online platforms for discussion and organization of workshops, with the participation of international stakeholders concerned with the evolution of the cultural sector, aimed to manage the economic risk associated with the COVID-19 pandemic. Among them, we mention the platforms of Live Learning Experience: Beyond the immediate response to the outbreak of COVID-19, managed by UGLS-United Cities and Local Governments, and MoMA (Museum of Modern Art), managed by the Museum of Contemporary Art in New York, along with workshops, namely Coronavirus (COVID-19) and museums: impact, innovation and post-crisis planning; Coronavirus (COVID-19) and cultural and creative sectors: impact, policy responses and opportunities to recover after the crisis; Summer Academy on Cultural and Creative Industries and Local Development, managed by the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development, in partnership with the International Council of Museums and the European Creative Business Network.

An important role in ensuring social resilience as a response to the current pandemic crisis is played by both the entrepreneurial capacity to create something out of necessity in a short period of time [25] and the integration of active workers from the cultural-creative sector in cultural associations and networks, seen not only as meeting venues for artists, but also as a form of constant support in risk situations [40].

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Research Setting

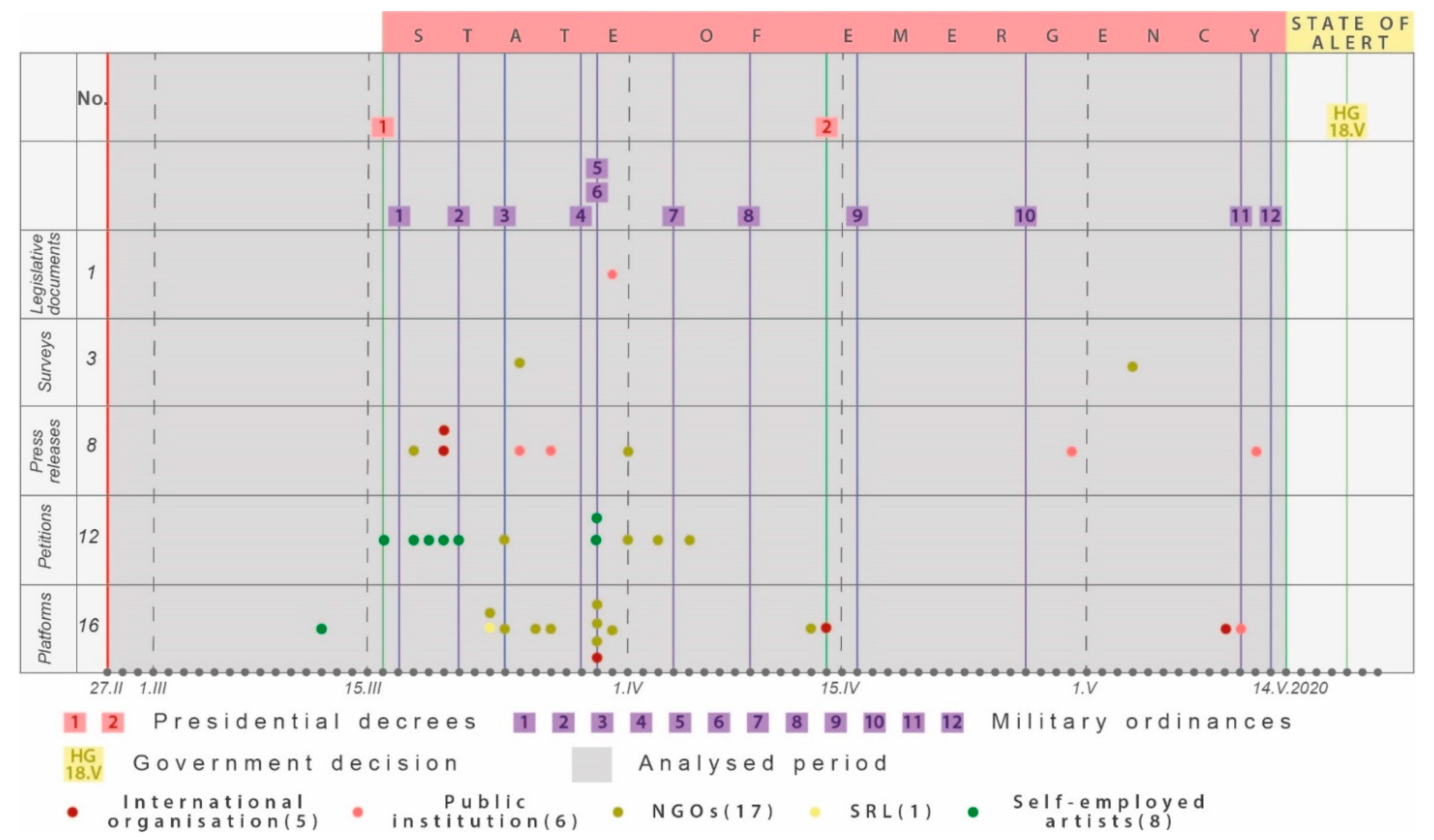

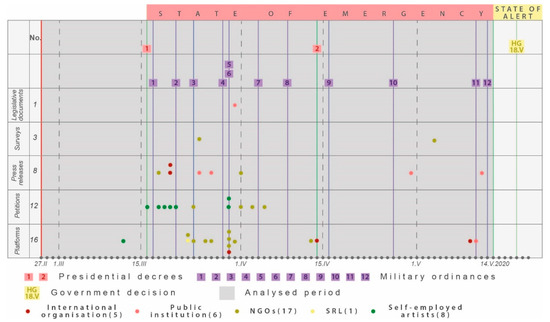

The cultural sector is one of the economic sectors most affected by the COVID-19 pandemic. First with the suspension of cultural activities, limitation of the number of spectators, followed by the cancellation of any type of event with public attendance, cultural activity stopped in any closed space around the world. In Romania, the spread of the COVID-19 virus and the appearance of the first cases of infection determined the establishment of the emergency state at the national level. In response to the newly generated socioeconomic context, public and private operators in the cultural sector tried to emphasize the impact generated by the pandemic, at the local, national or European level (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Public documents illustrating the state of the Romanian cultural sector, published online in the period 27 February–14 May 2020.

The current research considered the analysis of the immediate reactions of cultural operators, public and private, to the pandemic shock. Thus, all the documents published on finding resilience solutions, reflected in the online environment during the state of emergency (27 February–14 May 2020) were taken into account, without a selective filtering. The initiatives launched at national level were highlighted, and special attention was paid to those launched by the cultural operators from Cluj-Napoca and Timișoara, two urban centers whose cultural activity has already been acknowledged in the 2019 edition of the report Cultural and Creative Cities Monitor [44]. Currently, in addition to public cultural spaces, some other 126 independent cultural spaces are located in these two cities.

Following this approach, 36 public documents were identified (Figure 1), such as platforms or solidarity campaigns (n = 16); petitions (n = 12), many of them aimed at the socio-economic protection of the cultural worker; press releases (n = 8), promoters of some support measures; questionnaires for advocacy actions for independent cultural communities (n = 3); and a legislative act of the Romanian Government formulated in order to allocate a financial support to cultural workers.

Most of the reactions toward the precarious situation of the cultural sector and the financial instability of cultural workers came from the independent cultural sector (17 NGOs and 8 independent artists). In the first reference period (12 March–1 April 2020), there was also an immediate reaction from the stakeholders who were the first to experience the effects generated by the cessation of cultural activity, which consisted of the release of 19 documents. Compared to the independent cultural sector, which does not have a clear status at the moment in Romania, the public cultural institutions, subordinated to the Ministry of Culture, are characterized by some economic stability, including from the perspective of providing logistics and maintenance costs. Moreover, through their institutionalized status, the public institutions were direct beneficiaries of the support allowances allocated by the Romanian Government, including technical unemployment, in the amount of 75% of the basic salary. This may explain the relatively low number (n = 5) of the reactions signed by the institutionalized cultural sector.

In this article, the reference period selected for testing the immediate reactions of the independent cultural sector in Romania strictly overlapped with the emergency period (15 March–14 May 2020). The subsequent evolution of this sector has been partially highlighted as agreed responses from the responsible stakeholders in the Discussions section. The vulnerability of this sector, already existing even before the outbreak of the pandemic, and the measures taken so far at various territorial levels reflect a vision of short-term adaptation, which determines another early stage in Romania of cultural resilience.

The only concrete response to all public documents released at the national level, which was issued during the state of emergency period, was the Ordinance no. 741 of 31 March 2020 setting up social protection measures, by paying benefits under a contract with an employer, for workers in the cultural industries [45].

2.2. The Grounded Theory Methodology (GTM)

Developed in 1967 by B. Glaser and A. Strauss, the grounded theory is a qualitative method most commonly used in social sciences, which allows for the collection and ordering of empirical data into a theoretical model [46,47,48]. Most of the qualitative theories are substantive theories because they include/approach issues delimited in substantive constructions [46]. Due to the descriptive presentation of the results, this methodology has been intensely criticized; subsequently, one of the newly used approaches is the constructivist grounded theory based on data, which was developed by the sociologist Charmaz [46,48,49].

Data conceptualization is the foundation of a data-driven framework; all analyzed data are coded and categorized [50,51,52]. Moreover, there are five methods of data coding, either as alternative approaches to the theory developed by Glaser and Strauss, or as better versions of it [51].

Regarding the coding analytical framework, the specialist literature provides several alternatives:

- Starting from the constant comparative method, Glaser and Strauss propose a comparative procedure for code analysis, vaguely formulating how to choose data categories [51,53];

- The existing coding typologies are subsequently formulated by Glaser, as substantive coding (with open coding and selective coding) and theoretical coding, the latter conceptualizing the existing relationships between the created codes, through a line-by-line analysis [51,54]. These relationships are nothing but hypotheses. Glaser introduces 18 coding families [53]. More recent studies recommend avoiding the use of theoretical codes and promote the use of in vivo codes, which can be extracted directly from the content analyzed by using CAQDAS (Computer-assisted qualitative data analysis software) [55].

- Another code analysis matrix refers to the existence of 3 categories of codes: open, axial and selective codes [56]. Axial codes are the so-called code families, such as The Six Cs (causes, contexts, contingencies, consequences, conditions) [55,57,58], while selective codes make reference to the main categories of information on which the elaboration of the theory is based [55]. Coding can be performed paragraph-by-paragraph, line-by-line or sentence-by-sentence.

- Charmaz, (2006) insists on the use of two coding stages: initial coding and focused coding, either line-by-line or word-by-word [46].

- Bryant, (2017) advocates for the use of initial and focused codes, and for the last category he provides examples of coding strategies [51];

- Clarke et al., (2015) propose the situational analysis and also take into account different representation techniques (situational maps, social worlds, positional maps) along with coding and code analysis [59].

The evaluation of data-based theories must consider certain criteria such as credibility, originality, usefulness and resonance [46].

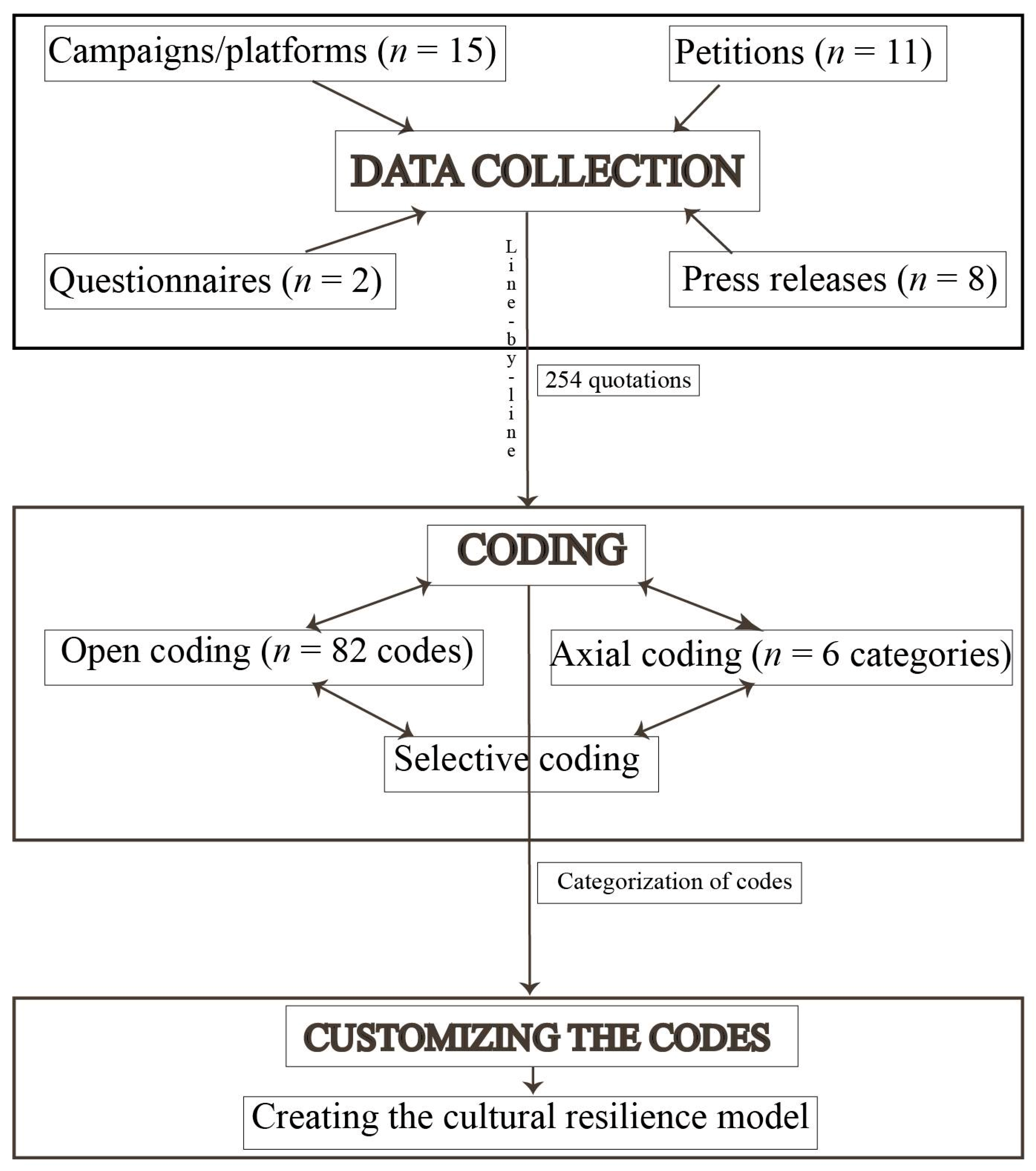

2.3. Data Collection and Analysis

The methodology included the use of data-based theory through qualitative analysis of information and coding, which was performed using the CAQDAS software-Computer Assisted Qualitative Data Analysis Software (ATLAS.ti 8) [52,60,61,62] and the creation of a theoretical model. This was considered the most appropriate methodology because we approached a new and a quite rarely analyzed topic in the literature especially in relation to the recent development of the COVID-19 pandemic.

We performed the content analysis of 36 public documents published online in the period 27 February–14 May 2020, broadly overlapping the state of emergency in Romania. These public documents were initiated by the following categories of stakeholders: independent artists (n = 8), public institutions (n = 5), NGOs (n = 7), international organizations (n = 5) and LLCs (n = 1).

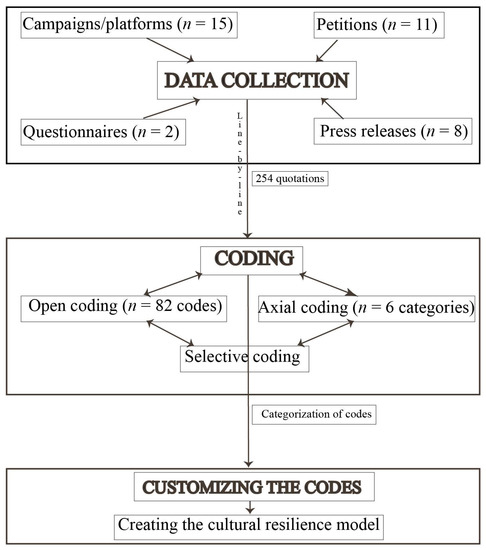

We followed the work steps proposed by Corbin and Strauss [56], Alasseri et al. [63], Gioia et al. [64], Acun and Yilmazer [65], Alkema [66], Chandra and Paras [58], Espriella and Gómez [67]. Data were analyzed in a cyclical process to achieve the most correct filtering of the categories. Initially, some 82 codes were created, subsequently re-categorized into 6 code groups: authorities, challenges, COVID-19 pandemic, cultural creative sector, resilience and temporal framework (Figure 2). The authors used the coding proposed by Corbin and Strauss, by creating 82 open codes, which were then grouped into 6 representative categories (axial codes). The interrelationships between codes were formulated through network analysis.

Figure 2.

The methodological flowchart.

To represent data-based theory, storytelling was used as a working technique, which was less obvious in the research conducted by Glaser and Strauss [53] but more prominent in the methodology of Strauss and Corbin [56], in which case the storyline had the role of story conceptualization and was part of the selective coding process [68,69].

3. Results

3.1. The Independent Cultural Sector or How Representative Are the Independent Cultural Spaces

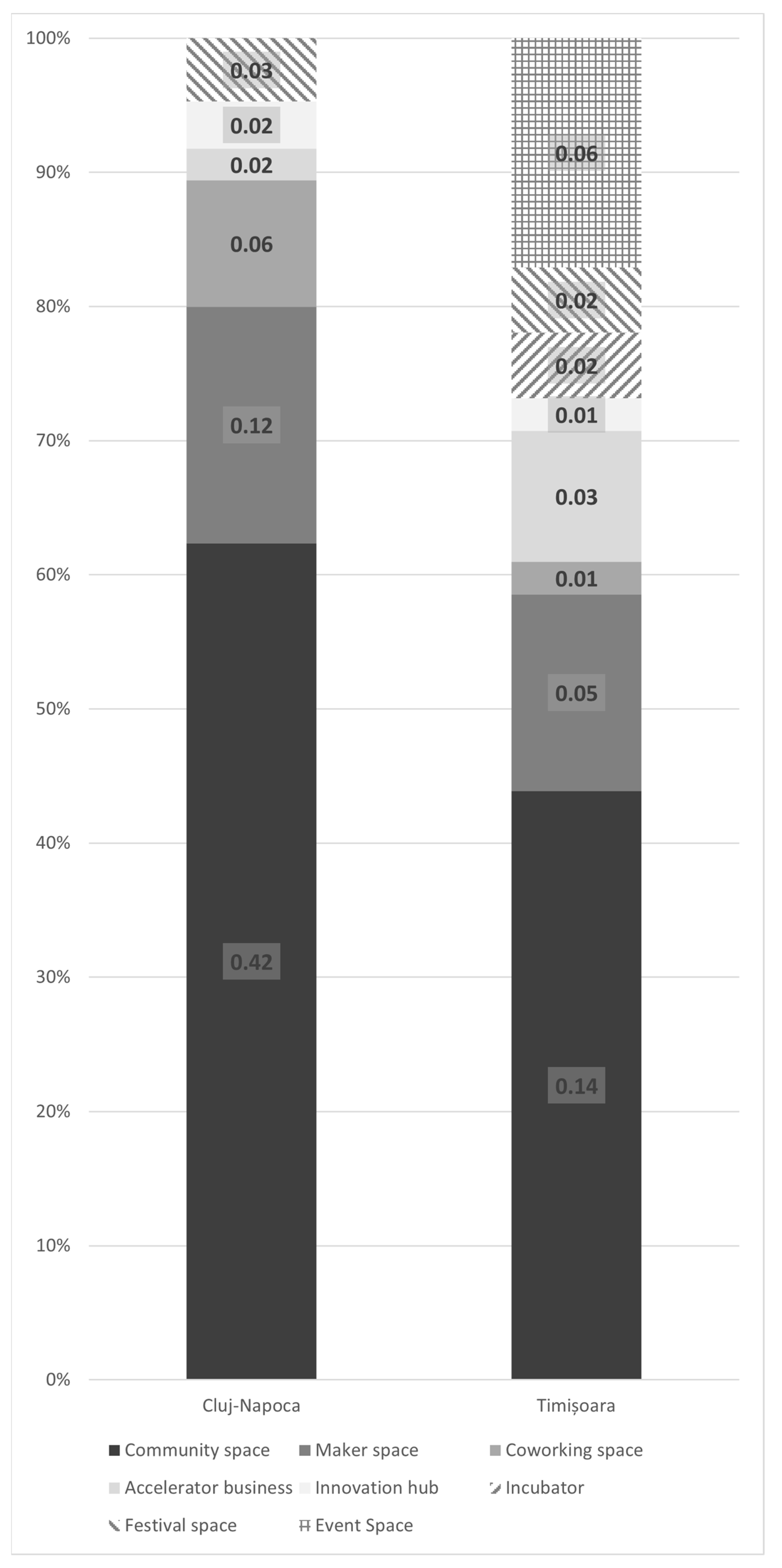

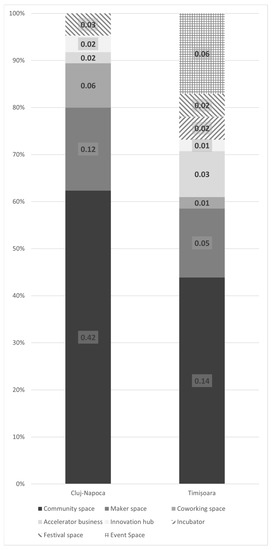

Some 126 creative spaces were identified in the two cities, yet unequally distributed, in Cluj-Napoca being recorded twice as many compared to Timișoara (85 vs. 41 spaces). Most of them are community spaces (56.4%), followed by maker spaces (17.7%) and six other categories representing less than 10% (Table 1). Compared to the overall state of the independent creative spaces, the following distinctive features are highlighted for Cluj-Napoca: (a) the share of community spaces slightly increased (from 56.4% to 62.4%), (b) maker spaces maintain their share and (c) there are no incubators and event spaces; whilst for Timișoara: (a) there is a decrease in the number of community spaces; (b) another category of cultural spaces registers an average weight (event spaces, 17.1%) along with maker spaces (14.6%).

Table 1.

A two-way table illustrating the distribution of categories of independent creative spaces in Cluj-Napoca and Timișoara.

Table 2 and Figure 3 highlight the consistency of shares when comparing the two cities in terms of availability of creative spaces, with a majority for Cluj-Napoca (0.67 vs. 0.33), and regarding categories of spaces, in which case five of the eight categories of spaces found in Cluj-Napoca have a higher frequency (between 28% and 1% of the total). At the same time, event spaces, incubators and business accelerators are more common in Timișoara (some 1–6% of the total).

Table 2.

Joint distribution of independent creative spaces in Cluj-Napoca and Timișoara.

Figure 3.

Stacked bar graph showing the conditional distribution of the independent creative spaces in Cluj-Napoca and Timișoara.

3.2. The Impact of COVID-19 Pandemic on the Cultural Sector

The appearance and spread of the SARS-CoV2 virus triggered a socioeconomic crisis worldwide (COVID-19 crisis = 72). It is felt among workers in the cultural sector whose existence is directly conditioned by the extent of the pandemic, the measures taken by authorities in the field and the available financial resources (challenges = 38).

The presence of this pandemic has brought a series of problems/challenges for the cultural sector, from the complete closure of cultural spaces and the suspension of projects under implementation up to a real medical crisis amplified by the lack of social protection measures, lack of financial stability and impossibility to provide basic subsistence (rent, utilities, etc.) (Table 3).

Table 3.

Frequency of codes associated with the impact of COVID-19 on the cultural sector.

The current pandemic brought to attention the most vulnerable social categories, with some 32 opinions being found in this regard. We learned about them in the public documents in which cultural workers or independent artists were classified as a vulnerable group: “independent artists are some of the most affected professional groups in this period of crisis” (PD4) or “Beyond the immediate health policy response, the world needs decisive and ambitious actions to mitigate the economic downturn and protect the most vulnerable. This is all about people: older people and the young, women and men, those on low income or no income, those who were already facing a difficult situation and who will be hit hardest.” (PD6).

3.3. Digital Initiatives Targeting the Cultural Sector during the COVID-19 Pandemic

Regarding stakeholders involved in cultural activities, we note the independent artists (G = 82) and the public authorities (G = 95). Regardless of the type of activity carried out, all categories of artists are equally affected. Here, we include actors, visual artists, musicians, various categories of performers and designers, directors, photographers, writers, translators, dancers, etc. This vulnerability of the creative cultural sector (independent artists, freelancers, cultural workers, NGOs, event organizers, cultural entrepreneurs) is mainly determined by the overall financial instability given by the lack of fixed term employment contracts and high level of dependence on external funding to implement their professional projects.

No matter the initiators of all these public documents, they were all addressed to the authorities: “Now is the time for urgent and large-scale responses, to be taken at sub-national, national and international levels.” (PD6), “We call on the European Commission and the Member States to take immediate action in a coordinated manner and do whatever it takes to mitigate the negative consequences of the COVID-19 crisis on the Cultural and Creative Sectors, especially independent creators as well as small and medium-sized enterprises and associations.” (PD23), “Music sector joins together to call for EU and national investment to address current crisis and promote diversity.” (PD27). Although the reactions of the cultural sector illustrated a bottom-up approach, petitioners expected a more integrative response, which would represent the national response to local problems (from the Romanian Government, the Ministries, the President of Romania). The calls from international organizations also show a differentiated support for the member states of the European Union.

Even from the beginning of the pandemic, the organizers of cultural events proved to have civic responsibility, initially suspending the events or limiting the public access, and then with the state of emergency, they completely stopped all activities. Now, all of the dysfunctions of an already underfunded economic sector become visible. Additionally, even more affected is the independent, underfunded cultural sector, a community that has just reached maturity, but is limited to its own finances. Be them independent or employed, artists in the cultural sector call for any type of financial support (donations, loans, sponsorships, vouchers, project budget, fiscal measures, etc.), for collaborative actions with the authorities, the public or even between artists, but also for community support (Table 4). All these financial measures are the first subjects of complaints on behalf of all staff in the creative industries sector.

Table 4.

Frequency of codes associated with the types of support needed by the cultural sector.

Temporal resilience of the cultural sector (in the short, medium and long term) can be supported gradually, through a series of actions initiated exclusively by the local authorities, joint public-private collaboration initiatives or through the support of civil society. In this regard, the following measures should be considered:

- (a)

- Short-term measures:

- Tax exemption for individuals and legal entities operating in the cultural sector during the pandemic;

- Set up social protection measures for artists and other categories of cultural workers;

- Set up a solidarity fee;

- Establish a legal framework for independent artists. The first initiative in this regard has already been released on 20 March 2020 by the National Institute for Cultural Research and Training, and the first Independent Cultural Register at the national level was created.

- Carry out a diagnostic analysis on the effects of the pandemic to identify optimal solutions for activities to be carried out in creative spaces;

- Adjust the Start-up Nation Program in order for cultural entrepreneurs to become eligible to apply for funding;

- Provide consultancy services for the creative cultural sector;

- Reopen cultural spaces;

- Reallocate available funds to support health care services;

- Digitize cultural activities and products, encourage teleworking and move events or activities online, if suitable.

- (b)

- Medium-term measures:

- Organize project competitions for eligible applicants to apply for funding to secure event production, logistics, payments, etc.;

- Organize mass events;

- Use art to increase public awareness and level of information on the consequences of any crisis;

- Create consortia between the stakeholders involved in cultural sector at the European level to set up collaborative projects.

- (c)

- Long-term measures:

- Create a stable professional environment for cultural workers;

- Create an open-air museum, as a theme park on the COVID-19 pandemic;

- Set up a new, high-tech and more flexible cultural infrastructure;

- Elaborate policies to promote and support cultural resilience.

In the long run, the common goal of all actors involved is to ensure resilience, yet this is differently perceived depending on their ability to act. While the civil society resilience to this pandemic resides in the discovery of a licensed vaccine and financial stability, the survival of the cultural sector lies in collaborative actions with the decision-makers. Local authorities need to find for independent artists their reliable social partners for designing and implementing cultural policies.

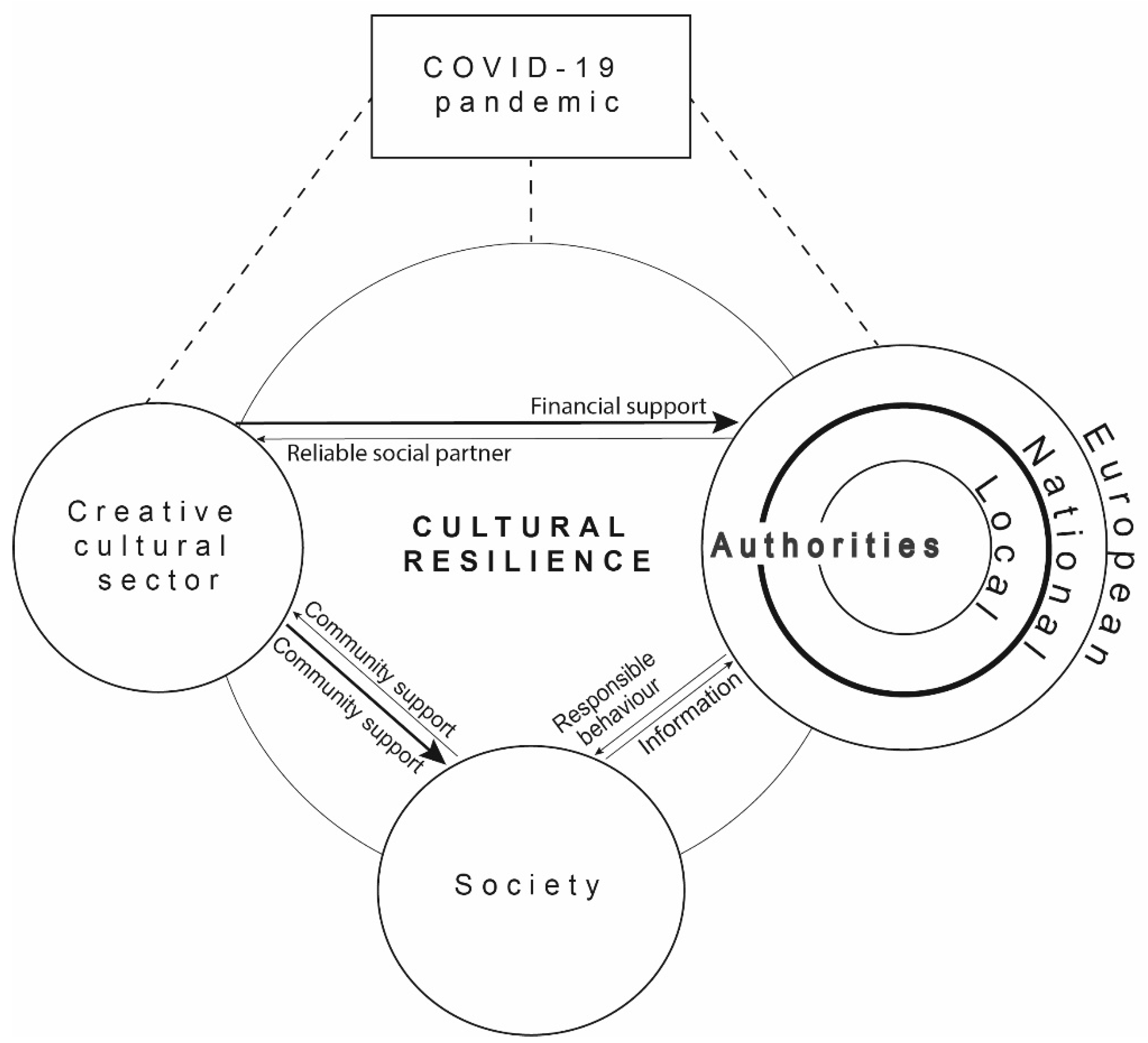

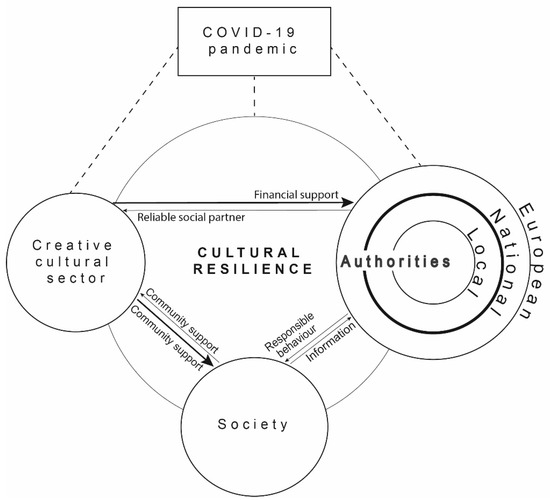

3.4. Cultural Resilience as Storyline

The COVID-19 pandemic has affected most of the world’s economic sectors in general, and some subsectors in particular, namely the cultural subsector. Perceived as one of the vulnerable social groups in this context, cultural workers, especially the independent artists, are directly dependent on their relationships with decision-makers and civil society. In this regard, we point out the following relationships (Figure 4):

Figure 4.

Theoretical model of cultural resilience.

- Collaborative relationship between the cultural sector and the civil society, beneficiary or not of some cultural actions, through community support actions, namely volunteering, donations, moral support, solidarity and civic participation;

- Supportive relationship between the civil society and the decision-makers, for delivering information and raise awareness on the appropriate social behavior to respect social distance and receptivity to population needs by taking measures to increase the safety of citizens;

- Interdependent relationship between the cultural sector and the authorities, on the one hand by ensuring a stable economic environment (financial support, fiscal policies) and, on the other hand, by involving artists, regardless of their nature, in the decision-making process and implementation of public policies.

The resilience of the cultural sector depends on the interrelationships between cultural workers and the national authorities, which seem the most appropriate, either in the case of a bottom-up or top-down approach.

4. Discussion

The existence or absence of policies in a field of activity that support investment in that economic sector are those that generate, in the long run, the development vision of that sector. The overall fragility of the independent cultural sector, Romanian in particular, but also related to the countries of Central and South-Eastern Europe [70,71], has become a reality throughout this European space. It has been accelerated by the COVID-19 pandemic by making this sector even more vulnerable. On the other hand, exploiting the discussion associated with existing cultural policies at the national level, in the last decade there have been several attempts to highlight strategic cultural directions, as evidenced by the public documentation released by the Ministry of Culture:

- (a)

- Proposal for a public policy on the digitization of national cultural resources and the creation of the Digital Library of Romania;

- (b)

- Proposal for a public policy on increasing the life quality in rural and small urban areas from the perspective of cultural services;

- (c)

- Public policy proposal on redefining the status of performance or concert institutions and defining the status of performance or concert companies on the background of clarifying their organization and operation, as well as the activity of artistic entrepreneurship.

From the content of these proposals, the legislated elements regarding the independent cultural sector were those related to redefining the status of performance institutions (Ordinance no. 21 of 31 January 2007 on institutions and companies of events or concerts, as well as artistic entrepreneurship).

The only existing cultural planning document at national level is the Strategy for Culture and National Heritage 2016–2022. The priority directions of investment are established in the medium term [72]. Initiatives to encourage cultural entrepreneurship are also taken into account as strategic objectives.

Starting with the state of emergency until present (March 2022), when most of the restrictions of social distancing imposed by the authorities ceased, several top-down directions were identified in the sphere of the independent cultural sector, all in the short term:

- (a)

- The granting of a package of measures launched in 2021 by the Ministry of Culture, to support the resumption of activities in the independent cultural sector (de minimis aid schemes for independent artists, allowances/technical unemployment for all cultural workers or micro-grants for cultural entities);

- (b)

- The launch, in 2022, by the Ministry of Culture of the Emergency Cultural Program regarding the request for an annual non-reimbursable financial support for the cultural projects/actions carried out. Among the eligibility criteria is the involvement of the independent cultural environment in the project.

- (c)

- The proposal of a de minimis aid scheme by the Ministry of Culture (document under public debate) which has in view grants for 5000 cultural operators (NGOs and cultural enterprises) and who had restricted activity during the state of emergency/alert;

- (d)

- Punctual initiatives to encourage cultural entrepreneurship were proposed at local level, by local authorities or other cultural entities (three editions of the Culturepreneurs program, launched in Cluj-Napoca by Cluj Cultural Center, non-reimbursable funding from the local budget for projects and cultural actions granted by the municipalities of Cluj-Napoca and Timișoara, through the Project Center).

In addition to financial interventions, another action that may have an impact on the status of the independent cultural sector was the creation of the Cultural Sector Register, initiated by the National Institute for Cultural Research and Training in 2020. The aim was to inventory the entities that operate in the cultural field, with 3500 registered cultural workers, 1179 NGOs and 3135 companies operating in the cultural field.

Moreover, in the case of Timișoara, the program of the European Capital of Culture, proposed for funding for 2023, will also represent an opportunity for cultural regeneration of this city.

Creative industries are characterized by organizational, financial and social insecurity, including the organization of social capital, being highly dependent on flexible collaborations and informal networking [73]. The actions of solidarity shown by those working in the creative cultural sector during the pandemic have demonstrated the existence of openness to communication and cooperation.

5. Conclusions

This paper falls into the category of studies that analyze crisis management, in this case the crisis being triggered by the COVID-19 pandemic. Independent artists represent one of the vulnerable social groups affected by this pandemic; hence, the model of cultural resilience was generated by reporting the interested/responsible stakeholders to this crisis.

The analysis of the concept of resilience in the current pandemic context, applied to fragile economic actors, confirms the importance of social relations theory [34]. Solidarity and social unity are the fundamental arguments to bring in setting up risk management measures, while civic involvement plays a significant role in promoting these initiatives. Thus, informal social interactions [74] are, in this case, the optimal resources of artists and cultural workers to build their resilience. The political and economic comfort in the area where the cultural-creative activities evolve is also important. However, the bottom-up approach, which consisted of analyzing the position of the independent cultural-creative sector in the given situation by using appropriate methodological tools (Atlas.ti8), illustrates that, beyond social relations, the hierarchical relationships set up to provide financial support are of the same importance in building resilience. From this point of view, the immediate reactions of self-help of cultural professionals did come from the national authorities, but few in quantity and in the short term.

Adapted to the new context of social distancing, especially the emergency state, all forms of reactions from cultural operators were captured online. They were all addressed to decision-makers (European Commission, ministries, local authorities, civil society, economic operators, etc.), aiming to identify temporary/alternative solutions, beyond the community support. Given these conditions, decision-makers restructured the allocation of financial resources, the cultural sector becoming a priority sector in Romania, with immediate reactions.

What is surprising in such an emergency context is that, despite the strong military decentralization in recent decades, including the demand for financial autonomy at the local level (not yet existing!), crisis management requires a national centralized approach, in which the state becomes responsible for solving socioeconomic problems.

Moving events and results of cultural activity online was another form of adaptation of the cultural sector, in which context the current audience would maintain its number or new user communities can appear. However, in order to preserve the quality of the artistic act, creative efforts and new digital skills will be needed on behalf of the artists.

Study Limitations

Being a theoretical model, there are limitations regarding the coded information; data was categorized in English, although part of the analyzed public documents was written in the Romanian language and another part in the English language. Another limitation comes from the selected analysis period, namely the time interval superimposed on the state of emergency in Romania, which apparently can give the impression of a segmentation of the evolution of the independent cultural sector.

Author Contributions

All authors, A.-C.M.-P., A.-M.P., G.-G.H. and J.A.N., contributed equally to the design and implementation of the research, to the analysis of the results, to the writing of the manuscript and to the revised version of this paper. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by PNCDI III: PN3/3.1 Bilateral/multilateral AUF-RO program, grant number 17-AUF/01.03.2019, name of project: “Heritage and urban renewal: creative spaces, inclusive culture and civic engagement”. The publication of this article was supported by the 2021 Development Fund of the Babeș-Bolyai University. The APC was partially sustained by reviewer discount vouchers.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Menon, K.U. Risk Communications: In Search of a Pandemic. Ann. Acad. Med. Singap. 2008, 37, 525–534. [Google Scholar]

- Hui, D.S.; Azhar, E.I.; Madani, T.A.; Ntoumi, F.; Kock, R.; Dar, O.; Ippolito, G.; Mchugh, T.D.; Memish, Z.A.; Drosten, C.; et al. The continuing 2019-nCoV epidemic threat of novel coronaviruses to global health–the latest 2019 novel coronavirus outbreak in Wuhan, China. Int. J. Infect. Dis. 2020, 91, 264–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- You, H.; Wu, X.; Guo, X. Distribution of COVID-19 Morbidity Rate in Association with Social and Economic Factors in Wuhan, China: Implications for Urban Development. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 3417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramaci, T.; Barattucci, M.; Ledda, C.; Rapisarda, V. Social stigma during COVID-19 and its impact on HCWs outcomes. Sustainability 2020, 12, 3834. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bloom, D.E.; Cadarette, D.; Sevilla, J.P. Epidemics and Economics. New and resurgent infectious diseases can have far-reaching economic repercussions. Financ. Dev. 2018, 55, 46–49. [Google Scholar]

- Thakar, V. Unfolding Events in Space and Time: Geospatial Insights into COVID-19 Diffusion in Washington State during the Initial Stage of the Outbreak. ISPRS Int. J. Geo-Inf. 2020, 9, 382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rudnick, A. Social, Psychological, and Philosophical Reflectionson Pandemics and Beyond. Societies 2020, 10, 42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bain, A.L. Artists as property owners and small-scale developers. Urban Geogr. 2018, 39, 844–867. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- OECD-Intergovernmental Economic Organisation. Coronavirus (COVID-19) and Cultural and Creative Sectors: Impact, Innovations and Planning for Post-Crisis. 2020. Available online: http://www.oecd.org/ (accessed on 2 September 2021).

- Briguglio, L.; Cordina, G.; Farrugia, N.; Vella, S. Economic Vulnerability and Resilience: Concepts and Measurements. Oxf. Dev. Stud. 2009, 37, 229–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guillaumont, P. An Economic Vulnerability Index: Its Design and Use for International Development Policy. Oxf. Dev. Stud. 2009, 37, 193–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- International Working Group on Financing Preparedness (IWG). From Panic and Neglect to Building Global Health Security: Investing in Pandemic Preparedness at a National Level. The World Bank. 2017. Available online: http://documents1.worldbank.org/ (accessed on 3 September 2021).

- Price-Smith, A.T. Contagion and Chaos: Disease, Ecology, and National Security in the Era of Globalization. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 2009, 15, 1881–1882. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alam, G.M.M.; Sarker, M.N.I.; Gatto, M.; Bhandari, H.; Naziri, D. The Impact of COVID-19 on Fisheries and Aquaculture–A global Assessment from the Perspective of Regional Fishery Bodies. No. 1. Rome. 2020, p. 35. Available online: http://www.fao.org/3/ca9279en/ca9279en.pdf (accessed on 3 September 2021).

- Ahmed, W.; Payyappat, S.; Cassidy, M.; Harrison, N.; Besley, C. Sewage-associated marker genes illustrate the impact of wet weather overflows and dry weather leakage in urban estuarine waters of Sydney, Australia. Sci. Total Environ. 2020, 705, 135390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eid, N.A.A.; Arnout, B.A. Crisis and disaster management in the light of the Islamic approach: COVID-19 pandemic crisis as a model (a qualitative study using the grounded theory). J. Public Aff. 2020, e221, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hawkins, R.; Maurer, K. Bonding, bridging and linking: How social capital operated in New Orleans following Hurricane Katrina. Br. J. Soc. Work 2010, 40, 1777–1793. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brockie, L.; Miller, E. Understanding older adults’ resilience during the Brisbane floods: Social capital, life experience, and optimism. Disaster Med. Public Health Prep. 2017, 11, 72–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hobbs, J.; Grigore, G.; Molesworth, M. Success in the management of crowdfunding projects in the creative industries. Int. Res. 2016, 26, 146–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hager, A.M. Financial Vulnerability among Arts Organizations: A Test of the Tuckman-Chang Measures. Nonprofit Volunt. Sect. Q. 2001, 30, 376–392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taylor, S.; Littleton, K. Art work or money: Conflicts in the construction of a creative identity. Sociol. Rev. 2008, 56, 275–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tuckman, H.P.; Chang, C.F. A methodology for measuring the financial vulnerability ofcharitable nonprofit organizations. Nonprofit Volunt. Sec. Q. 1991, 20, 445–460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rajagopal, D. Development of Consumer Behavior. Transgenerational Marketing; Springer International Publishing: New York, NY, USA, 2020; pp. 163–194. [Google Scholar]

- Al-Dabbagh, Z.S. The Role of Decision-maker in Crisis Management: A qualitative Study Using Grounded Theory (COVID-19 Pandemic Crisis as A Model). J. Public Aff. 2020, 20, e2186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maritz, A.; Perenyi, A.; de Waal, G.; Buck, C. Entrepreneurship as the Unsung Hero during the Current COVID-19 Economic Crisis: Australian Perspectives. Sustainability 2020, 12, 4612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holling, C.S. Resilience and Stability of Ecological Systems. Ann. Rev. Ecol. Syst. 1973, 4, 1–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gunderson, L.H. Ecological Resilience–In Theory and Application. Ann. Rev. Ecol. Syst. 2000, 31, 425–439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Devece, C.; Palacios-Marqués, D.; Alguacil, M.P. Organizational commitment and its effects on organizational citizenship behavior in a high-unemployment environment. J. Bus. Res. 2016, 69, 1857–1861. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Folke, C.; Carpenter, S.R.; Walker, B.; Scheffer, M.; Chapin, T.; Rockström, J. Resilience thinking: Integrating resilience, adaptability and transformability. Ecol. Soc. 2010, 15, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cocean, P. Dezvoltarea regională–obiectiv strategic sau provocare multicauzală? Geogr. Napoc. 2011, V, 5–12. [Google Scholar]

- Cutter, S.L. Resilience to What? Resilience for Whom? Geogr. J. 2016, 182, 110–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hobfoll, S.E.; Palmieri, P.A.; Johnson, R.J.; Canetti-Nisim, D.; Hall, B.J.; Galea, S. Trajectories of Resilience, Resistance and Distress during Ongoing Terrorism: The Case of Jews and Arabs in Israel. J. Consult. Clin. Psychol. 2009, 77, 138–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adger, W.N. Social and Ecological Resilience: Are They Related? Prog. Hum. Geogr. 2000, 24, 347–364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moore, M.; Westley, F. Westley. Surmountable chasms: Networks and social innovation for resilient systems. Ecol. Soc. 2011, 16, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scheffran, J.; Marmera, E.; Sow, P. Migration as a contribution to resilience and innovation in climate adaptation: Social networks and co-development in Northwest Africa. Appl. Geogr. 2012, 33, 119–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ostadtaghizadeh, A.; Ardalan, A.; Paton, D.; Jabbari, H.; Khankeh, H. Community Disaster Resilience: A Systematic Review on Assessment Models and Tools. PLoS Curr. 2015, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morrow, B.H. Community resilience: A social justice perspective. CARRI Res. Rep. 2008, 4, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thiele, L.P. Sustainability, 2nd ed.; Polity Press: Cambridge, UK, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Holtorf, C. Embracing change: How cultural resilience is increased through cultural heritage. World Archaeol. 2018, 50, 639–650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pérez-Ibáñez, M.; López-Aparicio, I. Art and Resilience: The Artist’s Survival in the Spanish Art Market—Analysis from a Global Survey. Sociol. Anthropol. 2018, 6, 221–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Goldfarb, J.C. On Cultural Freedom; The University of Chicago Press: Chicago, IL, USA, 1983. [Google Scholar]

- Chang, C.L.; McAleer, M.; Wong, W.K. Risk and Financial Management of COVID-19 in Business, Economics and Finance. J. Risk Financ. Manag. 2020, 13, 102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, X.; Wang, J.; Zhang, M.; Wang, X. Using Social Media to Mine and Analyze Public Opinion Related to COVID-19 in China. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 2788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montalto, V.; Tacao Moura, C.; Panella, F.; Alberti, V.; Becker, W.; Saisana, M. The Cultural and Creative Cities Monitor; European Commission: Ispra, Italy, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Guvernul României. 2020. Ordin nr. 741 din 31 Martie 2020 Pentru Aprobarea Modelului Documentelor Prevăzute la Art. XII alin. (1) din Ordonanța de Urgență a Guvernului nr. 30/2020 Pentru Modificarea și Completarea unor Acte Normative, Precum și Pentru Stabilirea unor Măsuri în Domeniul Protecției Sociale în Contextul Situației Epidemiologice Determinate de Răspândirea Coronavirusului SARS-CoV-2, cu Modificările și Completările Aduse prin Ordonanța de Urgență a Guvernului nr. 32/2020 Pentru Modificarea și Completarea Ordonanței de Urgență a Guvernului nr. 30/2020 Pentru Modificarea și Completarea unor acte Normative, Precum și Pentru Stabilirea Unor Măsuri în Domeniul Protecției Sociale în Contextul Situației Epidemiologice Determinate de Răspândirea Coronavirusului SARS-CoV-2 și Pentru Stabilirea unor Măsuri Suplimentare de Protecție Socială, Monitorul Oficial, Partea I, nr. 269 din 31 Martie 2020. Available online: https://legislatie.just.ro/Public/DetaliiDocument/224529 (accessed on 3 September 2021).

- Charmaz, K. Constructing Grounded Theory: A Practical Guide through Qualitative Analysis; SAGE Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA; New Delhi, India; London, UK, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Cho, J.Y.; Lee, E. Reducing Confusion about Grounded Theory and Qualitative Content Analysis: Similarities and Differences. Qual. Rep. 2014, 19, 1–20. Available online: http://nsuworks.nova.edu/tqr/vol19/iss32/2 (accessed on 3 September 2021). [CrossRef]

- Brennen, B. What is Grounded Theory Good for? J. Mass Commun. Q. 2018, 95, 11–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Treem, J.W.; Browning, L. Grounded Theory. In The International Encyclopedia of Organizational Communication, 1st ed.; Scott, C.R., Barker, J.R., Kuhn, T., Keyton, J., Turner, P.K., Lewis, L.K., Eds.; Wiley-Blackwell: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holton, J. The Coding Process and Its Challenges. In The SAGE Handbook of Grounded Theory; Bryant, A., Charmaz, K., Eds.; SAGE Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA; New Delhi, India; London, UK, 2007; pp. 265–289. [Google Scholar]

- Belgrave, L.L.; Seide, K. Coding for Grounded Theory. In The SAGE Handbook of Current Developments in Grounded Theory; Bryant, A., Charmaz, K., Eds.; SAGE Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA; New Delhi, India; London, UK, 2019; pp. 167–185. [Google Scholar]

- Soratto, J.; Pires, D.E.; Friese, S. Thematic content analysis using ATLAS.ti software: Potentialities for research in health. Rev. Bras. Enferm. 2020, 73, e20190250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glaser, B.; Strauss, A. The Discovery of Grounded Theory: Strategies for Qualitative Research; Sociology Press: Mill Valley, CA, USA, 1967. [Google Scholar]

- Sala Defilippis, T.M.L.; Curtis, K.; Gallagher, A. Moral resilience through harmonised connectedness in intensive care nursing: A grounded theory study. Intensive Crit. Care Nurs. 2020, 57, 102785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Böhm, A. Theoretical Coding: Text Analysis in Grounded Theory. In A Companion to Qualitative Research; Flick, U., Kardoff, E., Steinke, I., Eds.; SAGE Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA; New Delhi, India; London, UK, 2004; pp. 270–275. [Google Scholar]

- Corbin, J.; Strauss, A. Grounded Theory Research: Procedures, Canons, and Evaluative Criteria. Qual. Sociol. 1990, 13, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Avila-Soares, R.; Soares de Lima, S.; Kessler, M.; Eberhardt, T. Coding and analyzing data from the perspective of the theory based on data: Case report. J. Nurs. 2015, 9, 8915–8922. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chandra, Y.; Paras, A. Social entrepreneurship in the context of disaster recovery: Organizing for public value creation. Public Manag. Rev. 2020, 23, 1856–1877. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clarke, A.; Friese, C.; Washburn, R. Situational Analysis in Practice: Mapping Research with Grounded Theory; Left Coast Press: Walnut Creek, CA, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Friese, S. CAQDAS and Grounded Theory Analysis. MMG Work. Pap. 2016, 16-07, 1–33. [Google Scholar]

- Friese, S. Grounded Theory Analysis and CAQDAS: A Happy Pairing or Remodeling GT to QDA? In The SAGE Handbook of Current Developments in Grounded Theory; Bryant, A., Charmaz, K., Eds.; SAGE Publications: London, UK; Thousand Oaks, CA, USA; New Delhi, India, 2019; pp. 282–313. [Google Scholar]

- Friese, S. Qualitative Data Analysis with Atlas.Ti, 3rd ed.; SAGE Publications: Los Angeles, NA, USA; London, UK; New Delhi, India; Singapore; Washington, DC, USA; Melbourne, Australia, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Alasseri, R.; Rao, T.; Sreekanth, K.J. Conceptual framework for introducing incentive-based demand response programs for retail electricity markets. Energ. Strateg. Rev. 2018, 19, 44–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gioia, D.A.; Corley, K.G.; Hamilton, A.L. Seeking Qualitative Rigor in Inductive Research: Notes on the Gioia Methodology. Organ. Res. Methods 2013, 16, 15–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Acun, V.; Yilmazer, S. Combining Grounded Theory (GT) and Structural Equation Modelling (SEM) to analyze indoor soundscape in historical spaces. Appl. Accoustics 2019, 155, 515–524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alkema, P.J. A Sentiment Scale for Agile Team Environments in Large Organisations: A Grounded Theory. Ph.D. Thesis, Faculty of Engineering and the Built Environment, University of the Witwatersrand, Johannesburg, South Africa, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Espriella, R.; Gómez Restrepo, C. Research methodology and critical reading of studies Grounded theory. Rev. Colomb. Psiquiatr. 2020, 49, 126–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Birks, M.; Mills, J.; Francis, K.; Chapman, Y. A thousand words paint a picture: The use of storyline in grounded theory research. J. Res. Nurs. 2009, 14, 405–417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Birks, M.; Mills, J. Rendering Analysis through Storyline. In The SAGE Handbook of Current Developments in Grounded Theory; Bryant, A., Charmaz, K., Eds.; SAGE Publications: London, UK; Thousand Oaks, CA, USA; New Delhi, India, 2019; pp. 243–258. [Google Scholar]

- Popa, N.; Pop, A.M.; Marian-Potra, A.C.; Cocean, P.; Hognogi, G.G.; David, N.A. The Impact of the COVID-19 Pandemic on Independent Creative Activities in Two Large Cities in Romania. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 7674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Strategia Pentru Cultură și Patrimoniu Național 2016–2022; Romanian Government: Bucureşti, Romania, 2016.

- Apitzsch, B.; Piotti, G. Institutions and Sectoral Logics in Creative Industries: The Media Cluster in Cologne. Environ. Plan. 2012, 44, 921–936. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keck, M. Market Governance and Social Resilience: The Organization of Food Wholesaling in Dhaka, Bang Ladesh. Ph.D. Thesis, 2012. Unpublished work. [Google Scholar]

- Kwark, Y.; Chen, J.; Raghunathan, S. Online product reviews: Implications for retailers and competing manufacturers. Inf. Syst. Res. 2014, 25, 93–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).