The Use of Mobile Phones and Other Unsafe Behavior While Cycling in the Metropolitan Area of Mexico City

Abstract

:1. Introduction

1.1. The Use of Mobile Phones While Riding

1.2. Other Unsafe Acts While Cycling

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Binary Logistic Regression

2.2. Survey Design and Data Collection

2.3. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Respondents Characteristics

3.2. The Use of Mobile Phones for Talking & Texting While Riding a Bicycle

3.3. Contributors to Crashes/Falls While Cycling

3.3.1. LR Model and the Frequency of Talking, the Social Network, and Gender as Explanatory Variables of a Crash/Fall

3.3.2. LR Model and the Frequency of Text Messaging, the Social Network, and Gender as Explanatory Variables to Crash/Fall

3.3.3. Logistic Model to Identify the Predictors to Crashes/Falls While Cycling

4. Discussion

4.1. On the Use of Mobile Phones for Talking/Text Messaging While Cycling

4.2. On the Influencing Factors to Crash/Fall While Cycling

4.3. Limitations and Future Research

- The findings of the present study should not be taken as definitive but should be viewed with caution. The employed data may not be reliable. Moreover, it is well known that there is a lack of single-bicycle crashes (SBCs) data [1,2,3,4,5]. In the present work, the data were self-reported by the students who participated in the study; it may well be the case that the reported prevalence of crash/fall is not accurate. That is, the findings may lead to bias given that participants, for example, did not use a mobile phone while cycling. More research is needed that considers data on actual crashes/falls while cycling. Police and emergency services may be a good source of SBCs records for further research.

- This sample size was used for convenience, and therefore the findings should not be generalized to the whole population of the metropolitan area of Mexico City. Hence, other demographic characteristics of respondents should be considered for further analysis (e.g., socioeconomic status and to expand the age range of the participants).

- In the present work, only six variables related to unsafe behavior were considered as contributing factors to a crash/fall while cycling; other unsafe acts may be considered in future research, e.g., riding on the opposite direction to the traffic, the use of helmets, among others. Further research may include the design of a reliable scale of unsafe acts while cycling by considering the aforementioned issues.

- The present study did not consider other factors, such as those related to road conditions (e.g., dry, wet, loose objects on the road, uneven road surface), environmental conditions (e.g., season of the year, time of day, weather conditions), bicycle type (mountain, racing bikes), and bicycle malfunction (e.g., brake defects, too-low tire inflation, loose handlebars), among others. Moreover, the length of a trip plays an important factor, and the age of the cyclists may contribute to a fall/crash [5]. Furthermore, in the food delivery industry, time pressure to provide a service on time pushes the riders, for example, to bypass red lights [9]. More research on these issues is needed.

5. Conclusions

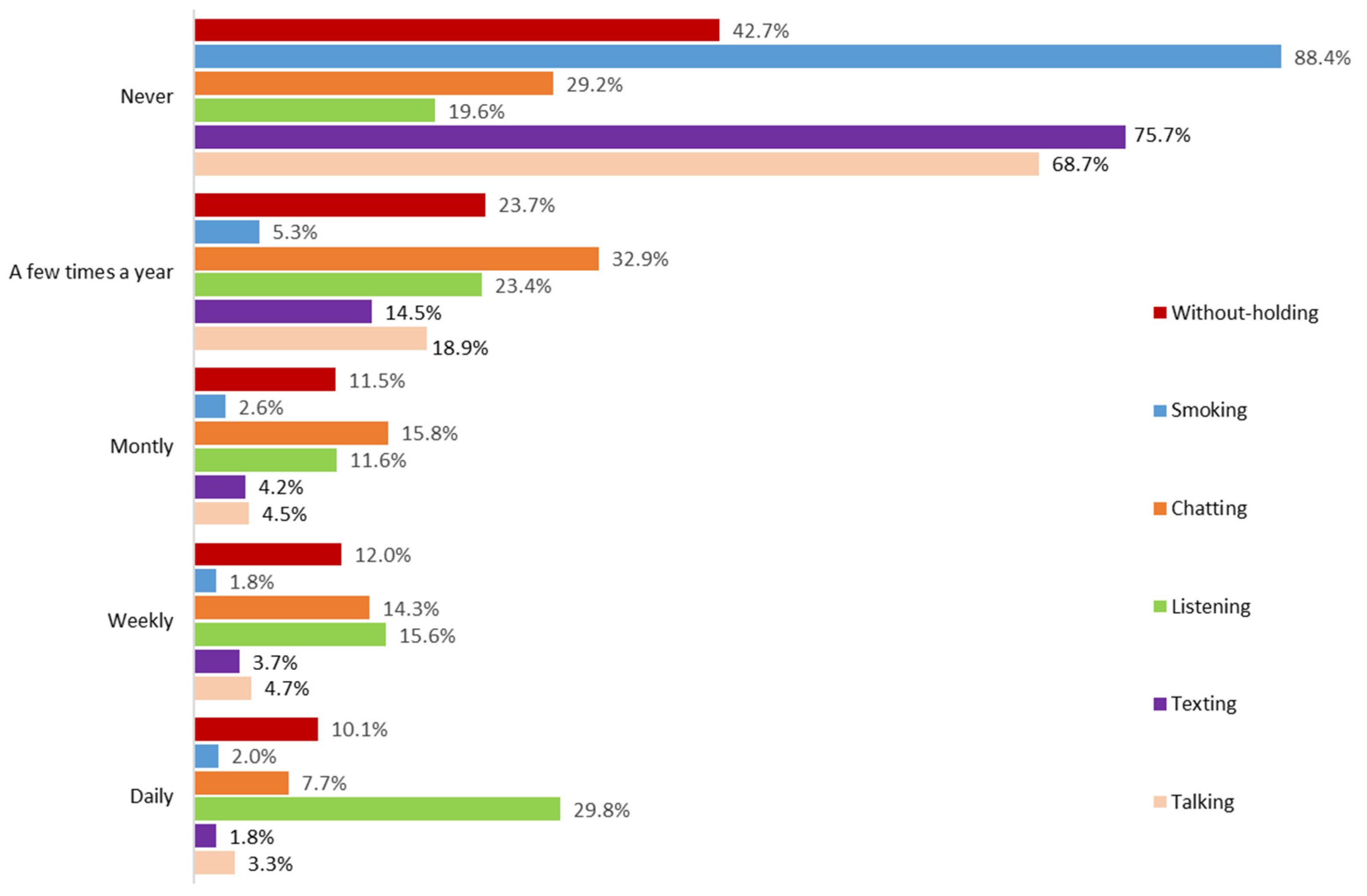

- In total, 31.4% of the participants have used the mobile phone for talking while riding a bicycle with only 3.3% doing so on a daily basis.

- In total, 24.2% of the students have used the mobile phone for text messaging, with only 1.8% doing so daily.

- Males engage on these unsafe acts while cycling more often (i.e., talking weekly, and text messaging “a few times a year”) than females.

- The majority reported that they are most likely to communicate with their parents, either talking on a mobile phone (48.9%) or by text messaging (39.6%).

- Respondents’ communication with a friend either by talking or text messaging came second, at 22.4% and 25.2%, respectively.

- The results show that a one SD change in the frequency of talking while cycling increased the odds of fall/crash by a factor of 1.198, as did a one SD increase in the frequency of texting by 1.232.

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Schepers, P.; Agerholm, N.; Amoros, E.; Benington, R.; Bjornskau, T.; Shondt, S.; Hagemeister, C.; Loo, B.P.; Niska, A. An international review of the frequency of single-bicycle crashes (SBCs) and their relation to bicycle modal share. Inj. Prev. 2015, 21, e138–e143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Hosseinpour, H.; Madsen, T.K.O.; Olsen, A.V.; Lahrmann, H. An in-depth analysis of self-reported cycling injuries in single and multiparty bicycle crashes in Denmark. J. Saf. Res. 2021, 77, 114–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olsen, A.V.; Madsen, T.K.O.; Hels, T.; Hosseinpour, H.; Lahrmann, H. Single-bicycle crashes: An in-depth analysis of self-reported crashes and estimation of attributable hospital costs. Accid. Anal. Prev. 2021, 161, 106353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Eriksson, J.; Niska, A.; Forsman, A. Injured cyclists with focus on single-bicycle crashes and differences in injury severity in Sweden. Accid. Anal. Prev. 2022, 165, 106510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schepers, P.; Wolt, K.K. Single-bicycle crash types and characteristics. Cycl. Res. Int. 2012, 2, 119–135. [Google Scholar]

- Reason, J. Human error: Models and management. BMJ 2000, 320, 768–770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Datareportal. Digital 2022: Global Overview Report. 2022. Available online: https://datareportal.com/reports/digital-2022-global-overview-report (accessed on 10 October 2022).

- Robb, M.B.; Bay, W.; Vennegaard, T. The New Normal: Parents, Teens, and Mobile Devices in Mexico; Common Sense: San Francisco, CA, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Oviedo-Trespalacios, O.; Rubie, E.; Haworth, N. Risky business: Comparing the riding behaviours of food delivery and private bicycle riders. Accid. Anal. Prev. 2022, 177, 106820. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Christie, N.; Ward, H. The health and safety risks for people who drive for work in the gig economy. J. Transp. Health 2019, 13, 115–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Terzano, K. Bicycling safety distracted behvior in the Hague, the Netherlands. Accid. Anal. Prev. 2013, 57, 87–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, K.; Yang, Z.; Feng, Z.; Sze, N.N.; Yu, Z.; Huang, Z.; Chen, J. Effects of using mobile phones while cycling: A study from the perspectives of manipulation and visual strategies. Transp. Res. Part F Psychol. Behav. 2021, 83, 291–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Waard, P.S.; Wieke, O.; Brookhuis, K. Mobile phone use while cycling: Incidence and effects on behaviour and safety. Ergonomics 2014, 53, 30–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- de Waard, P.S.; Lewis-Evans, B.; Jelijs, B.; Tucha, O.; Brookhuis, K. The effects of operating a touch screen smartphone and other common activities performed while bicycling on cycling behaviour. Transp. Res. Part F Psychol. Behav. 2010, 22, 196–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Ahlstrom, C.; Kircher, K.; Thorslund, B.; Adellb, E. Bicyclists’ visual strategies when conducting self-paced vs. system-paced smartphone tasks in traffic. Transp. Res. Part F Psychol. Behav. 2016, 41, 204–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Waard, D.; Westerhuis, F.; Lewis-Evans, B. More screen operation than calling: The results of observing cyclists’ behaviour while using mobile phones. Accid. Anal. Prev. 2015, 76, 42–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- LaVoie, N.; Lee, Y.-C.; Parker, J. Preliminary research developing a theory of cell phone distraction and social relationships. Accid. Anal. Prev. 2016, 86, 155–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Kadushin, C. Understanding Social Networks: Theories, Concepts and Findings; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Hill, L.; Rybar, J.; Styer, T.; Fram, E.; Merchant, G.; Eastman, A. Prevalence of and attitudes about distracted driving in college students. Traffic Inj. Prev. 2015, 16, 362–367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Truong, L.T.; Nguyen, H.T.T.; De Gruyter, C. Mobile phone use while riding a motorcycle and crashes among university students. Traffic Inj. Prev. 2019, 20, 204–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stelling-Konzcak, A.; van Wee, G.P.; Commandeur, J.J.F.; Hagenzieker, M. Mobile phone conversations, listening to music and quiet (electric) cars: Are traffic sounds important for safe cycling. Accid. Anal. Prev. 2017, 106, 10–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, A. Americans and Text Messaging; Pew Research Center: Washington, DC, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- NHTSA. An Examination of Driver Distraction as Recorded in NHTSA Databases; National Highway Traffic Safety Administration (NHTSA): Washington, DC, USA, 2009.

- Lv, H.; Li, H.; Sze, N.N.; Ren, G. The impacts of non-motorized traffic enforcement cameras on red light violations of cyclists at signalized intersections. J. Saf. Res. 2022, 83, 310–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- INEGI. Origin-Destination Survey in Households of the Metropolitan Zone of Valley of Mexico; INEGI: Mexico City, México, 2007.

- Everitt, B.S. Modern Medical Statistics: A Practical Guide; Arnold: London, UK, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Howmer, D.W.; Lemeshow, R.X. Sturdivant. In Applied Logistic Regression; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- de Gruyter, C.; Truonga, L.T.; Nguyen, H.T.T. Who’s calling? Social networks and mobile phone use among motorcyclists. Accid. Anal. Prev. 2017, 103, 143–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soto Maciel, A.; de la Garza Ramos, M.I.; Esparza Aguilar, J.L.; San Martín Reyna, J.M. The influence of family relationships in the succession A factorial analysis of Mexican enterprises. J. Fam. Bus. Manag. 2015, 5, 238–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Solís-Cámara, P.; Fung, M.P.; Fox, R.A. Parenting in Mexico: Relationships Based on Love and Obedience. In Parenting Across Cultures: Childrearing, Motherhood and Fatherhood 349 in Non-Western Cultures, Science Across Cultures: The History of Non-Western Science 7; Selin, H., Ed.; Springer: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beck, K.; Watters, S. Characteristics of college students who text while driving: Do their perceptions of a significant other influence their decisions? Transp. Res. Part F. 2016, 37, 119–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nicolls, M.; Truelove, V.; Stefanidis, K.B. The impact of descriptive and injunctive norms on engagement in mobile phone use while driving in young drivers: A systematic review. Accid. Anal. Prev. 2022, 175, 106774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Simons-Morton, B.G.; Farhat, T. Recent findings on peer group influences on adolescent smoking. J. Prim. Prev. 2010, 31, 191–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Love, S.; Truelove, V.; Rowland, B.; Kannis-Dymand, L.; Davey, J. Is all high-risk behaviour premeditated? A qualitative exploratory approach to the self-regulation of habitual and risky driving behaviours. Transp. Res. Part F Psychol. Behav. 2022, 90, 312–325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Variable | N | Min 1 | Max 1 | Mean | Median | SD |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

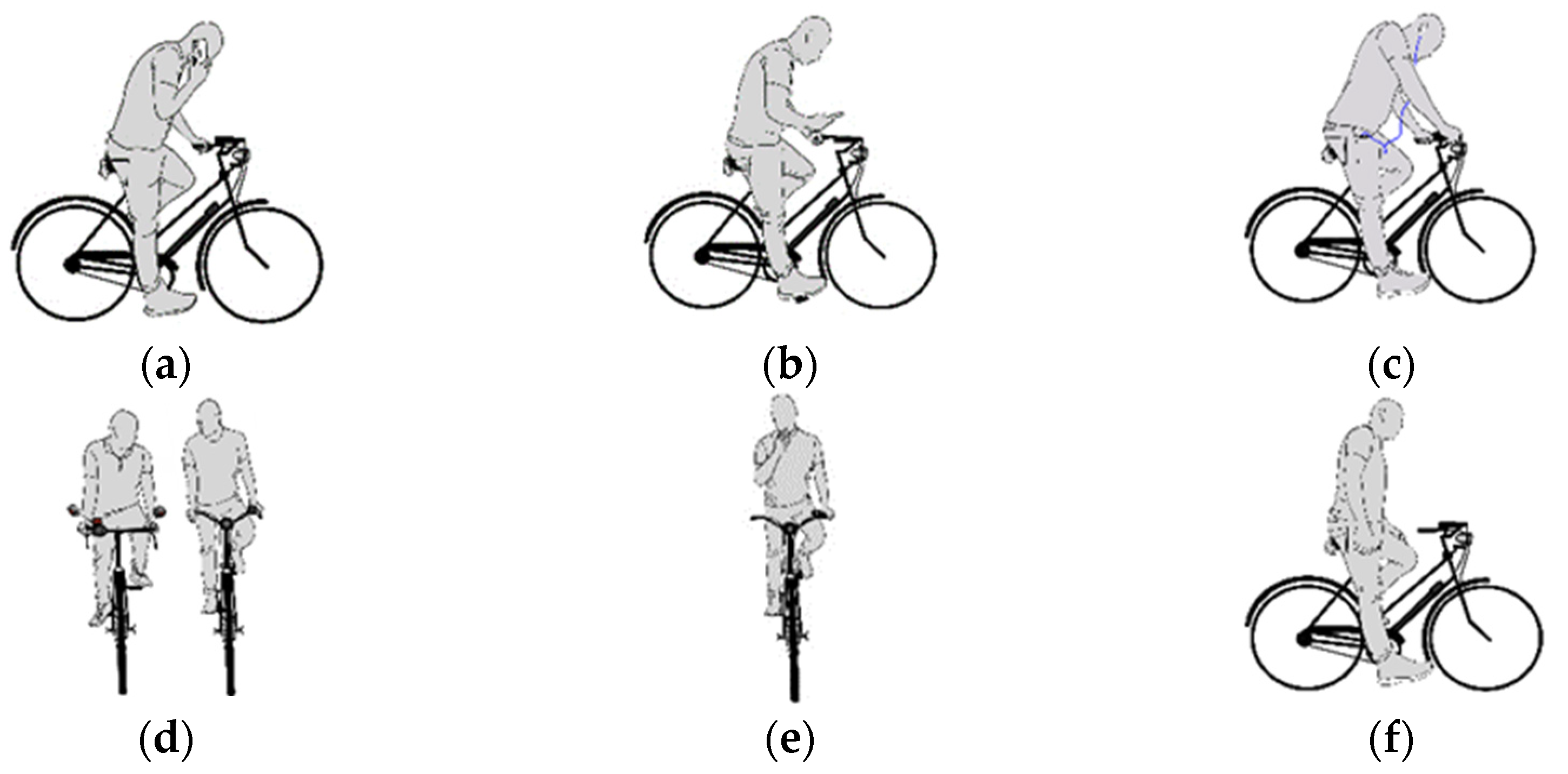

| (a). Use a mobile phone for making or receiving a phone call while cycling (Figure 1a) | 1136 | 1 | 5 | 1.5493 | 1.0 | 1.0045 |

| (b). Use a mobile phone for texting while cycling (Figure 1b) | 1136 | 1 | 5 | 1.4146 | 1.0 | 0.87838 |

| (c). Use a mobile phone to listen to music while riding the bike (Figure 1c) | 1136 | 1 | 5 | 3.1241 | 3.0 | 1.5336 |

| (d). Chatting or talking to other cyclists while cycling (Figure 1d) | 1136 | 1 | 5 | 2.3838 | 2.0 | 1.2539 |

| (e). Smoking while riding the bicycle (Figure 1e). | 1136 | 1 | 5 | 1.2377 | 1.0 | 0.76246 |

| (f). Riding the bicycle “without holding the handlebars” (Figure 1f) | 1136 | 1 | 5 | 2.2315 | 2.0 | 1.3712 |

| Variable | Measures | N (%) |

|---|---|---|

| If you use a mobile phone for receiving or making a phone call while cycling, who are you most likely to talk to? | 1 = Friend | 255 (22.4) |

| 2 = Girlfriend/boyfriend/spouse | 156 (13.7) | |

| 3 = Parent | 556 (48.9) | |

| 4 = Brother/sister | 77 (6.8) | |

| 5 = Colleague | 42 (3.7) | |

| 6 = Other | 50 (4.4) | |

| If you use a mobile phone for texting while cycling, who are you most likely to text? | 1 = Friend | 286 (25.2) |

| 2 = Girlfriend/boyfriend/spouse | 181 (15.9) | |

| 3 = Parent | 450 (39.6) | |

| 4 = Brother/sister | 114 (10.0) | |

| 5 = Colleague | 48 (4.2) | |

| 6 = Other | 57 (5.0) |

| Variable | Never N (%) | A Few Times a Year N (%) | Monthly N (%) | Weekly N (%) | Daily N (%) | Variable N (%) | Never N (%) | A Few Times a Year N (%) | Monthly N (%) | Weekly N (%) | Daily N (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Talking While Cycling 1 | Texting While Cycling 2 | ||||||||||

| Female | 299 (38.3) | 67 (31.2) | 13 (25.5) | 11 (20.8) | 10 (27.0) | Female | 324 (37.7) | 45 (27.3) | 13 (27.1) | 10 (23.8) | 8 (38.1) |

| Male | 481 (61.7) | 148 (68.8) | 38 (74.5) | 42 (79.2) | 27 (73.0) | Male | 536 (62.3) | 120 (72.7) | 35 (72.9) | 32 (76.2) | 13 (61.9) |

| Total | 780 (100) | 215 (100) | 51 (100) | 53 (100) | 37 (100) | Total | 860 (100) | 165 (100) | 48 (100) | 42 (100) | 21 (100) |

| Variable | Friend N (%) | Boyfriend/ Girlfriend, or Wife N (%) | Parents N (%) | Brother/ Sister N (%) | Colleague N (%) | Other N (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Female | 68 (26.7) | 55 (35.3) | 223 (40.1) | 29 (37.7) | 9 (21.4) | 16 (32.0) |

| Male | 187 (73.3) | 101 (64.7) | 333 (59.9) | 48 (62.3) | 33 (78.6) | 34 (68.0) |

| Total | 255 (100) | 156 (100) | 556 (100) | 77 (100) | 42 (100) | 50 (100) |

| Predictor Variable | Measures | β | SE | df | p | OR | 95% CI [Lower–Upper] |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Frequency of talking | Continuous (Never–Daily) | 0.180 | 0.062 | 1 | 0.004 | 1.198 | [1.061–1.352] |

| Who students talk to while cycling | Friend (base) | 5 | 0.498 | ||||

| Girlfriend/boyfriend, or wife | 0.259 | 0.216 | 1 | 0.230 | 1.296 | [0.849–1.979] | |

| Parents | 0.061 | 0.166 | 1 | 0.713 | 1.063 | [0.768–1.470] | |

| Brother/sister | 0.181 | 0.277 | 1 | 0.515 | 1.198 | [0.696–2.063] | |

| Colleague | 0.334 | 0.345 | 1 | 0.333 | 1.397 | [0.710–2.749] | |

| Other | −0.411 | 0.370 | 1 | 0.266 | 0.663 | [0.321–1.369] | |

| Gender | Male | 0.471 | 0.140 | 1 | 0.001 | 1.602 | [1.217–2.108] |

| Constant | −1.412 | 0.200 | 1 | 0.000 | 0.244 |

| Predictor Variable | Measures | β | SE | df | p | OR | 95% CI [Lower–Upper] |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Frequency of texting | Continuous (Never–Daily) | 0.238 | 0.070 | 1 | 0.001 | 1.268 | [1.105–1.455] |

| Who students text while cycling | Friend (base) | 5 | 0.447 | ||||

| Girlfriend/boyfriend, or wife | 0.030 | 0.206 | 1 | 0.885 | 1.030 | [0.688–1.542] | |

| Parents | 0.165 | 0.164 | 1 | 0.314 | 1.180 | [0.855–1.627] | |

| Brother/sister | 0.088 | 0.239 | 1 | 0.712 | 1.092 | [0.684–1.744] | |

| Colleague | −0.161 | 0.345 | 1 | 0.642 | 0.852 | [0.433–1.675] | |

| Other | −0.500 | 0.352 | 1 | 0.156 | 0.607 | [0.304–1.210] | |

| Gender | Male | 0.496 | 0.139 | 1 | 0.000 | 1.641 | [1.249–2.158] |

| Constant | −1.461 | 0.195 | 1 | 0.000 | 0.232 |

| Predictor Variable 2 | Measures | p | Unstandardized 1 | Standardized 1 | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| β | OR | β | OR | |||

| Frequency of unsafe acts | Making/receiving calls | 0.773 | 0.025 | 1.025 | 0.0251 | 1.025 |

| Texting | 0.415 | 0.079 | 1.082 | 0.070 | 1.072 | |

| Listening to music | 0.355 | 0.045 | 1.046 | 0.070 | 1.072 | |

| Talking to other cyclists | 0.074 | 0.101 | 1.106 | 0.127 | 1.135 | |

| Smoking | 0.989 | −0.001 | 0.999 | −0.0007 | 0.9999 | |

| Without holding the handlebars | 0.000 | 0.212 | 1.236 | 0.290 | 1.336 | |

| Gender | Male | 0.017 | 0.347 | 1.415 | ||

| Constant | 0.000 | −2.00 | 0.135 | |||

| Model summary: −2LL = 1374.027; χ2 = 56.90; df = 7; p < 0.001; Nagelkerke R2 = 7%; Hosmer & Lemeshow test, p = 0.391 | ||||||

| Unsafe acts scale | Unsafe acts | 0.000 | 0.524 | 1.689 | 2.285 | 9.82 |

| Gender | Male | 0.003 | 0.414 | 1.513 | ||

| Constant | ||||||

| Model summary: −2LL = 1381.40; χ2 = 49.541; df = 2; p < 0.001; Nagelkerke R2 = 6%; Hosmer & Lemeshow test, p = 0.424 | ||||||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Santos-Reyes, J.; Pastenes-Medina, Y.; Padilla-Pérez, D. The Use of Mobile Phones and Other Unsafe Behavior While Cycling in the Metropolitan Area of Mexico City. Sustainability 2023, 15, 61. https://doi.org/10.3390/su15010061

Santos-Reyes J, Pastenes-Medina Y, Padilla-Pérez D. The Use of Mobile Phones and Other Unsafe Behavior While Cycling in the Metropolitan Area of Mexico City. Sustainability. 2023; 15(1):61. https://doi.org/10.3390/su15010061

Chicago/Turabian StyleSantos-Reyes, Jaime, Yareli Pastenes-Medina, and Diego Padilla-Pérez. 2023. "The Use of Mobile Phones and Other Unsafe Behavior While Cycling in the Metropolitan Area of Mexico City" Sustainability 15, no. 1: 61. https://doi.org/10.3390/su15010061

APA StyleSantos-Reyes, J., Pastenes-Medina, Y., & Padilla-Pérez, D. (2023). The Use of Mobile Phones and Other Unsafe Behavior While Cycling in the Metropolitan Area of Mexico City. Sustainability, 15(1), 61. https://doi.org/10.3390/su15010061